Abstract

Phenomenon: The Coping Reservoir Model is a useful theoretical and analytical framework through which to examine student resilience and burnout. This model conceptualizes wellbeing as a reservoir which is filled or drained through students’ adaptive and maladaptive coping mechanisms. This dynamic process has the capacity to foster resilience and reduce burnout or the inverse. This study aimed to explore health profession students’ coping mechanisms and their experiences of resilience and burnout during the unprecedented COVID-19 pandemic. Approach: Employing the Coping Reservoir Model, qualitative focus groups involving health profession students enrolled at Qatar University were conducted, in October 2020, to solicit their lived experiences of stress and burnout during the pandemic. The Coping Reservoir Model was used to structure the topic guide for the focus group discussion and the Framework Analysis Approach was used in the data analysis. Findings: A total of 43 participants comprised eight focus groups. Health profession students encountered myriad personal, social, and academic challenges during the pandemic which adversely impacted their wellbeing and their capacity for coping. In particular, students reported high levels of stress, internal conflict, and heavy demands on their time and energy. The shift to online learning and uncertainty associated with adapting to online learning and new modes of assessment were exacerbating factors. Students sought to replenish their coping reservoir through engagement in a range of intellectual, social, and health-promoting activities and seeking psychosocial support in their efforts to mitigate these stressors. Insights: Students in this region have traditionally been left to their own devices to deal with stress and burnout during their academic training, wherein the institutions focus exclusively on the delivery of information. This study underscores student needs and potential avenues that health profession educators might implement to better support their students, for instance the development and inclusion of longitudinal wellbeing and mentorship curricula geared to build resilience and reduce burnout. The invaluable contributions of health professionals during the pandemic warrant emphasis, as does an examination of the stress associated with these roles to normalize and justify inclusion of wellbeing and resilience modules within the curriculum. Actively engaging health profession students in university-led volunteer activities during public health crises and campaigns would provide opportunities to replenish their coping reservoirs through social engagement, intellectual stimulation, and consolidating their future professional identities.

Introduction

Resilience helps health professionals to counter the deleterious effects of stress encountered in the workplace. Thus, it is widely recognized that health professions students should receive resilience training to better prepare graduates for the demands of twenty-first century work environments.Citation1,Citation2 Despite an extensive body of literature on burnout in the health profession,Citation3–6 there is a dearth of information about the delivery of resilience training in the prequalification academic phase of health professional training. Similarly, consensus is lacking regarding a definitive definition of resilience and what this training should encompass.Citation1 A scoping review of resilience acquisition in health profession education reveals that resilience building involves three stages: It commences with an adverse event; followed by a dynamic process of learning and problem solving; and culminates with the return of the affected individual to their previous state of wellbeing.Citation1 Confronted with a multitude of stressors such as deadlines, independence, intellectual challenges, university students employ a range of coping mechanisms to mitigate stress. Coping mechanisms are defined as voluntary thoughts and actions used to handle and control internal and external stress and can be classified as: problem-focused; meaning-focused; support-seeking; or instrumental support.Citation7 Increasing student engagement through the provision of extracurricular activities, student-led mentorship programs, career counseling, life coaching and stress management sessions are means to foster resilience among medical students.Citation8 Although, there is no “one-size-fits-all” strategy that works for every student, resilience programs geared to cultivate positive professional relationships between students and faculty have been shown to help students maintain positivity and achieve life balance.Citation9

The coping reservoir model

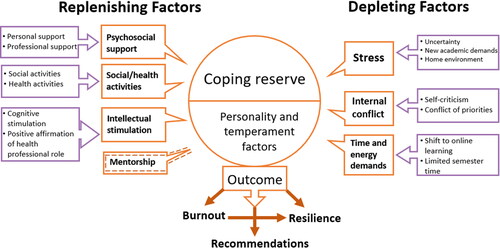

The Coping Reservoir Model is a useful theoretical and analytical framework through which to examine student resilience and burnout. This model conceptualizes wellbeing as a reservoir which is filled or drained through students’ adaptive and maladaptive coping mechanisms. This dynamic process has the capacity to foster resilience and reduce burnout or the inverse.Citation10 Reservoirs are replenished through positive factors including: psychosocial support, social activities, mentorship, and intellectual stimulation; whereas negative inputs including stress, internal conflict, and time and energy demands can deplete students’ coping reservoirs. These factors, in concert with a student’s temperament, personality traits, and coping style can lead to positive or negative outcomes contributing to resilience or burnout.Citation10 Burnout can affect long-term mental health and potentially compromise patient care in the future.Citation10 Having been used to evaluate the wellbeing of preclinical medical students in the U.S.,Citation11 the Coping Reserve Model here is applied to a Middle Eastern setting where it serves as the framework to explore health profession students’ wellbeing during the COVID-19 pandemic and the identification of factors contributing to resilience promotion and burnout reduction.

The COVID-19 pandemic necessitated quarantine measures that forced unprecedented social distancing, a situation that depleted many individuals’ psychological resilience reserve, and this was particularly heighted in caregivers.Citation12 It has even been postulated that this protracted social isolation combined with the stress owing to the uncertainty of its duration may have potentially lead to undesirable psychological effects or disorders including post-traumatic stress symptoms, confusion, and anger.Citation13 Similar to colleges around the world, Qatar University suspended face-to-face classes and switched abruptly to online learning in March 2020. In some cases, this sudden transition to online learning adversely affected students’ academic performance, mental health, and wellbeing. Universally, the situation resulted in social isolation, decreased physical activity, and for some, generated novel academic and nonacademic challenges that impacted student health.Citation14,Citation15 For those about to graduate, this was a period of heightened anxiety as they needed to demonstrate specific clinical competencies prior to advancing to the next phase of their training.Citation14 A cross-sectional study of pharmacy students found that the majority learned less during online education compared to in-person teaching.Citation16 Additionally, students cited limited direct interaction with professors and prolonged computer use as the main drawbacks of online learning.Citation16 Understanding the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on health profession students’ wellbeing within health programs, and the ability to cope with personal, emotional, and academic circumstances, has the potential to inform higher education of the need to take burnout into account when delivering their curriculum and offer opportunities for students to be able to detect burnout and learn how to mitigate it. This is crucial for graduating health professionals who can withstand pressure in the workplace.Citation17 Interventions to support students’ wellbeing during their tertiary education are recommended.Citation18 This will reflect positively on students’ performance and their provision of care for patients in the future. Therefore, the aim of this study was to explore health profession students’ coping mechanisms and their experiences of resilience and burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

Study design

We used focus groups in this qualitative study which employed a postpositivist perspective. We used an a priori theoretical framework, namely the Coping Reservoir Model, in the generation of data collection tools and informed subsequent analysis.Citation19 To obtain a rich, firsthand understanding of students’ experiences of their Spring academic semester of 2020 during the initial phase of the COVID-19 pandemic, we used focus groups.

Context and participants

This study serves as the qualitative phase of a larger research project looking at health profession students’ wellbeing during the pandemic. The other phase explored experiences of burnout, anxiety and empathy among health profession students during the COVID-19 pandemic in a cross-sectional study. In the quantitative phase of the study, showed burnout to be prevalent among students wherein a higher degree of anxiety correlated with a higher level of burnout. Similarly, a higher level of burnout was associated with a higher level of empathy. In the qualitative phase, we targeted health profession students from QU Health which is a cluster of all health colleges at Qatar University which includes the Colleges of Medicine, Health Sciences, and Pharmacy. The Dental and Nursing colleges were not included as they were only established after the conclusion of the study. All health profession students enrolled in undergraduate and postgraduate programs in QU Health were eligible to participate with no restrictions on age, gender, or level of study. Recruitment involved an email invitation to all eligible participants. Subsequently, we contacted health profession students who registered their interest in the earlier quantitative phase via an email containing an information leaflet, an invitation to participate in the focus groups and a link, to a consent form to be signed prior to participation. In line with the English-medium curriculum used in QU Health, all focus groups were held in English and included a mix of health profession students from different disciplines.

Data collection

We conducted virtual focus groups using the Cisco WebEx® platform in October 2020, a standardized interview script using open-ended questions. The topic guide was scaffolded on the Coping Reservoir Framework Citation10 (Appendix). Each of the eight focus groups lasted between 90-120 min and involved 4-10 students from a mixture of pharmacy, medical, and health sciences backgrounds. With participant consent, we audio-recorded and transcribed sessions verbatim using Cisco WebEx®. As this was a student research project, modeling research strategies was an important part of the learning process. The initial focus group was moderated by the principal researcher (AE) and observed by SI and RS (BSc students). Subsequent interviews were facilitated by these two students with the principal investigator observing the first few sessions.

Reflexivity

The research team engaged in an ongoing process of reflexivity throughout the data collection and analytical phases of the research in an effort to mitigate any potential biases. The composition of the research team consisted of individuals from different disciplines yielding multiple perspectives and insights into the generation of the data collection tools and the thematic analysis. The principal investigator holds a PhD in interprofessional education with a background in mixed method research. At the time of the study, AE was the Assistant Dean for Student Affairs and as such had an intimate understanding of students’ experiences during the pandemic. As pharmacy students during the pandemic, SH and RS brought a unique perspective to the interpretation of the data since they had encountered firsthand the challenges associated with online learning.

The interdisciplinary team comprised scientists and an anthropologist from the Colleges of Health Sciences, Pharmacy and Medicine, each of whom yielded a different perspective on the research. In addition, all of the faculty involved were active in the fields of health and medical education. Although AE conducted the first focus group and modeled the moderation for research students (SH and RS), they then carried out the remaining seven focus groups. Peer-lead focus groups were conducted in an effort to provide the student participants with an opportunity to discuss their perspectives more openly. In each focus group, SH and RS role alternated between being a moderator or an observer. SH and RS followed the same topic guide with prompts and were trained to avoid bringing their own views and potential biases into the discussion. Participants were encouraged to share both positive and negative experiences they have had during the pandemic. SH and RS took notes during the focus groups and discussed them later on with the whole team.

To reduce any possible biases and enhance the trustworthiness of the study findings, SH and RS coded the data independently followed by checking and validation by a faculty member of the research team. The team met several times to review findings, discuss and compare codes and themes, challenge individual assumptions, refine analysis as needed in an iterative process until consensus was reached. Having a team with diverse expertise and experiences was important to ensure that the interpretations were supported by the study findings and that the influence of the researchers’ own underlying assumptions or academic expertise, roles, and experiences could be recognized and accounted for. Moreover, cognizant of potential biases arising from the immediacy of the researchers’ own experiences of the pandemic, four months after the conclusion of the spring semester.

Data analysis

Transcripts were validated and verified with the audio recording by SI and RS. From the onset, the Coping Reservoir Model was identified as a useful framework upon which to scaffold the research. It was used both as a theoretical and an analytical tool. Employing the Framework Approach for data analysis involved the following sequential steps: familiarization with data; identifying and coding the relevant thematic domains identified in the Coping Reservoir Model against the data; indexing; charting the data into the framework matrix; mapping and data interpretation.Citation20 Ongoing analysis took place until thematic data saturation was achieved which was determined after the sixth focus group. A further two focus groups were conducted to confirm data saturation as no additional themes generated from the analysis of these transcripts.

Ethical considerations

The study was reviewed and approved by University’s Institutional Review Board (QU-IRB 1339-EA/20). Informed consent was obtained online. No participant identifiable information was collected. Only AE, SH and RS had access to the study data. Overall, the study was conducted with integrity according to generally accepted ethical standards.

Results

Of the 1268 eligible students, 272 students participated in the quantitative phase of this research project.Citation21 Of these, 54 indicated their willingness to participate in the qualitative phase. An email invitation was also sent to all eligible students across QU Health. A total of 45 students participated in the focus groups (6 from College of Medicine, 24 from College of Pharmacy and 15 from College of Health Sciences comprising students from biomedical sciences, human nutrition, physiotherapy, and public health). Thirty-seven students were undergraduates and 8 were graduate students. The majority were women (N = 41) and were in their fourth year, transitioning from preclinical to clinical (N = 15). We mapped our identified themes onto the Coping Reservoir Model domains ().

Key depleting factors

The three main factors identified as depleting students’ coping reservoirs were: stress, internal conflict, and time and energy demands.

Stress

The analysis revealed several subthemes that exacerbated students’ stress levels. These include: uncertainty, new academic demands, and working in a home environment. Uncertainty, the most prominent negative subtheme to develop from the data, was multifaceted. One facet involved a lack of understanding about the etiology, transmission, and duration of the COVID-19 virus. Many students mentioned concerns they had about familial health and the uncertainty of how parents and elder family members might fare were they to contract the virus. The absence of information prompted one pharmacy student to admit:

I felt really stressed during the pandemic, especially in the 1st period… And on the college level, we didn’t still know what to do. So, it was really tiring… it impacted my life because, I was always scared that one of my family members will be infected or even myself, and maybe I will have to skip the year, or maybe something even more dangerous or more severe will happen to any of us, so it was really stressful. [Pharmacy student 4]

Aside from the university stress itself, you worry about your family…Personally, I have a lot of family members who have chronic diseases, kidney failures, etc.…You worry about them a lot so, especially if they’re not as careful as you wish they would be. I did experience stress before, but I think this was a different kind of stress. [Health science student 6 (public health)]

I was stressed because, last semester was my 1st semester in health sciences and now by the end of this semester I need to declare my major… but because of the pandemic, the arrangement of the grades became different. I was stressed if I going to pass or fail the semester. I was worried that I might not be able to get the grades needed to declare my major. These thoughts stressed me out a lot. [Health Science Student 10 (biomedical)]

I believe the pandemic was a period of uncertainty. So many unanswered questions. How are we going to get assessed? Are we going to have exams on campus? Are we going to even have exams this year? We ended up having so many assignments and this created a lot of stress and anxiety to most of the students. [Medical Student 3]

Most stressful thing was the fact that we were on our laptops from the morning until night and it was so annoying because initially, I was sitting on a desk chair, and it was literally hurting my back. And then I started sitting in the living room on the couch and to be more with my family and at the same time, like, still doing my work. Eventually I couldn’t separate home from work, and I was working all day and I was not feeling Okay. I needed a break eventually to cope. What I did was very unhealthy. I started gaming after I finished all my work. So, I would finish work at 12 am and I would just game until 4 am. And then I would sleep and wake up for class and it was very bad. [Pharmacy student 2]

Several students mentioned that they found it difficult to find a suitable study space at home devoid of distractions, especially those with large intergenerational families. In addition, students said that they encountered technical difficulties due to poor internet connections at home. Student stress was compounded when students experienced slow internet connections or disconnection during quizzes or exams.

I actually had some internet connection, and it was one of the reasons that actually made me so stressed during this pandemic as I lost my Internet connection during one of my biggest exams. So, it was the most stressful thing to go through. [Medical student 2]

Despite being surrounded by family members, some students admitted to feeling lonely on account of their families not understanding their situation the way their peers might relate:

All of us being at home at the same time in front of each other…you feel like no one is understanding you and people who are in the same situation, such as your colleagues, your professors, they’re far away. So, you feel that you’re alone. So, I felt like loneliness was the biggest stressor for me or, like, not understanding. Like, people are not understanding my situation. [Pharmacy student 6]

Internal conflict

We identified two major subthemes in the internal conflict theme: self-criticism and conflict of priorities. The former involved student articulations of experiencing self-doubt during the pandemic. Isolated from their peers, they were unable to gauge the amount of effort they put into their studies. Despite many participants perceiving their expended effort to be far greater than previous face-to-face semesters, this was not reflected in their grade performance. Students not only began to question their abilities, but some - like this health profession student - also started questioning their professional aspirations and their suitability for their chosen field:

Can I be a dietitian in the future? Why am I studying this? Why am I a human nutrition student? Like, why didn’t I choose biomedical or, like, public health or something else? Like, I started questioning the major, I started questioning my abilities to be a dietician. [Health Science Student 7 (Human Nutrition)]

I actually started thinking about dropping the semester, but then I did not want to delay my graduation more…before the pandemic, we were motivated. [Pharmacy student 4]

Conflict of priorities was a second internal conflict that students spoke about which depleted their coping reservoirs. Participants were undecided as to whether they should prioritize their studies and academic assessments over their physical and mental health. A health science student explained:

I doubted if I should focus more on my health and get more sleep or if I actually should focus more on my studies…It was a conflict between my health, or no, I should focus on studying. [Health science student 1 (Human Nutrition)]

I could say at a certain point, I was seriously thinking about dropping my thesis and just quiting for that moment. And actually I sent an email to my supervisor about this and he was also frustrated. But in a couple of days, I changed my mind. [Health science student 4 (Public Health)]

Time and energy demands

Time and energy demands featured prominently in students’ identification of depleting factors. The mid-semester shift to online learning required all content, including clinical skills and lab sessions, to be disseminated in lecture format. These involved students sitting passively in front of screens for protracted periods of time. Some students admitted that they found it difficult to concentrate and focus under such circumstances. Students observed that due to a combination of technical issues combined with inexperience of delivering sessions online, some professors started become less conscientious of the length of their lectures. The increased time spent in lectures reduced their time to study and complete assignments which in turn negatively affected the students.

I found it hard to concentrate in my lectures, so, I had to spend more time understanding the lectures. Like, I watch the recording…. I did not get any rest, maybe like 3 hours maximum of sleep in the day. [Health sciences student 9 (public health)]

Spending more time engaged in sedentary online learning within the confines of the home, resulted in the reduction of students’ physical activity which consequently depleted their energy. Finding face-to-face classes more stimulating, students contended that they were able to concentrate better during on campus classes. Further, due to time lost as university administration and faculty scrambled to shift online, students felt that the contracted semester resulted in a significant increase in workload. These heavy demands compromised their sleep and their energy reserves as exemplified by a health sciences student’s comment:

We had a very small period of time that we could finish those assignments. Our screen time reached almost 17 to 18 hours per day, then the remaining is 6 hours, we did not sleep. [Health sciences student 4 (public health)]

Key replenishing factors

The Coping Reservoir Model comprises a number of positive inputs which replenish individuals’ coping reserves. The factors that students referred to during the focus groups included: psychosocial support, social/healthy activities, and intellectual stimulation ().

Psychosocial support

The first replenishing factor highlighted in the analysis was the importance of psychosocial support, which included both personal and professional support. Personal support consisted of students seeking comfort and motivation through family and friends. Many students regarded their peers as reliable sources of support, and sometimes alumni fulfilled this role. Some students who mentioned accessing online therapy to help manage their emotions, stress, and anxiety also sought external professional support by . One health science student explained:

I found a therapist. She is working with people who are suffering from COVID-19 and we talked…I became better and everything was fine, but I learned a lot from her about anxiety about panic attacks and how to deal with them and I still talk to her and it’s way better now. [Health science student 10, biomedical]

Some doctors would send messages asking me, “How is it going? Do you have any questions? Do you need more time?” That meant the world to me. Honestly, doctors like those have a huge space in my heart. It was really important to me. So, yeah, but, uh, generally. The doctors being more understanding really made a difference. [Pharmacy student 6]

Social/healthy activities

Some students conceded they were able to manage their time effectively and pursued an array of social and healthy activities to help cope with stressors. Three of the most common social activities students said they engaged in were playing board games with family, gaming online with friends, and preparing family meals. Many students took advantage of lockdown to engage in self-improvement such as learning a new language, learning how to bake, taking up a new instrument, or developing their artistic skills. Others introduced healthier lifestyle measures in a bid to improve their physical and mental health including healthy eating, improved sleep hygiene, and adopting a daily exercise regime. A medical student explains how lockdown afforded time for new activities:

Thinking about this now, social and healthy activities helped me a lot going through this. Now I remember that it was my 1st time having time to consider these. Running after dawn every day for about 30 minutes. [Medical student 4]

Intellectual stimulation

Students engaged in cognitive stimulation through a range of activities geared to improve their mental strength and to keep their minds active. Students explained that activities such as reading, listening to audiobooks and podcasts, attending educational webinars, completing puzzles, and learning new languages (including: Arabic, Korean, and French) helped them to de-stress.

I used to draw and then during the summer break, I was like, let’s try painting. So, I started painting I bought canvas i bought brushes paints, and I started painting. So that was my stress relief during the summer. [Health Science Student 7 (Human Nutrition)]

A few students mentioned that lockdown provided space for introspection and enabled them to reflect critically on their current position and future goals. To meet the demands of their increased workload and to manage the unprecedented situation, some students discussed experimenting with new time management strategies such as scheduling, journaling, and developing creative to-do lists.

Complete new to me was journaling and literally, it was a new thing to explore. It was so satisfying and de-stressing because it was basically putting my emotions through different media. Like, I would cut pieces from magazines. I’d find this quote that really speaks up to me during this time. It’s not like writing a diary. It’s more of like expressing myself. The funny thing is, I never would track time with journaling! I used to start working on this let’s say 7pm and then finish around 10 – 11pm and trust me. I never felt the time pass so quickly. I used to be very shocked. [Pharmacy student 12]

Positive affirmation of health professional role

Another positive replenishing factor that students identified as helping them cope was witnessing the invaluable roles that health professions played and the respect that they garnered during the COVID-19 pandemic. Many students said that seeing how indispensable health professionals were reaffirmed their career choice. One medical student explains how this positive affirmation during the pandemic motivated them and cultivated a desire to get involved:

I felt that I really need to be in the field. I didn’t like my, my role of staying at home. I looked differently, how the medical teams, including all of the members, would help to treat a patient with such a severe condition… I realized how important they are. [Medical student 3].

There were workshops from the International Pharmacy Student Federation team, and then I also attended a summer internship program…And then that made me realize that we are actually contributing so much to people’s health and making sure that everyone is healthy around us. And we play a really big role in general around the globe. I’m really grateful to be studying pharmacy. [Pharmacy student 11]

I really was proud of my major and what we are doing, Since from the beginning of this crisis we were volunteering in the ministry doing contact tracing…it was a pleasure for me to be part of the crisis management and contributing to saving the community health and fighting this pandemic. [Health science student 9 (public health)].

Outcome

During the focus groups a significant amount of time was spent discussing how stress encountered during the pandemic affected them. Some students asserted that COVID-related stress culminated in physical and mental manifestations. Among the physical manifestations, students complained they suffered from back pain, knee-joint pain, declining vision, acne, insomnia, and heart palpitations. Some participants said they experienced high levels of stress and anxiety and went through emotional breakdowns. For some, preexisting symptoms were exacerbated like this pharmacy student:

I feel like my social anxiety got worse. Way worse than it was before. Just because we were isolated at home. [Pharmacy student 9]

While they may have experienced burnout at the start of the pandemic coinciding with their spring semester, the vast majority of students in the focus groups contended they eventually built resilience and learned a lot about themselves in the subsequent semesters as evidenced by a pharmacy student’s admission:

Yes, there was burnout but for me, I was already in the state where I had to prioritize my health. I wouldn’t blame myself if I couldn’t achieve things that I should have achieved or should have done. So I did experience burnout, but I got out of it quicker. And with time I knew myself better. I would give myself more break. So, with time I did feel more resilient and more in control of what I’m doing.[Pharmacy student 6].

Students’ recommendations

Finally, participants provided a number of recommendations to promote effective coping strategies for health profession students. A popular suggestion was to ensure clear and frequent communication between the administration, faculty, and students during periods of crisis, allowing all stakeholders to express their concerns. Many students suggested that the university could have adopted a more flexible approach to assessments and deadlines and considered extending the semester:

I felt the most appropriate thing to do was to postpone the deadline to finish the semester. Because the decisions were out like a month after the pandemic happened. But that did not happen and all of the assignments, exams and assessments were all pressured in one month. So students were overwhelmed. [Pharmacy student 4]

Discussion

The results clearly indicate that both replenishing and depleting factors affected students’ coping reservoirs at the onset of the pandemic, and confer Dunn’s et al. assertion that coping is indeed a dynamic process.Citation10 The application of the Coping Reservoir Model and its concomitant themes helpfully elucidate these Middle Eastern health profession students’ experiences. Many of the findings in this study confirm the value of the utility of Dunn et al.’s model since it informed the development of the data collection tools and was applied during the analytical phase, revealing insights into student adversity as experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic. While the study results may have differed had we opted to use a different model to frame our data collection and analysis, we selected Dunn’s model on the grounds that it had the potential to capture both factors that affect students’ burnout and resilience and their resultant coping mechanisms.

We identified uncertainty as a prominent theme in the data owing to student fears ranging from of contracting the virus and transmitting it to vulnerable family members. In a society where many students live with extended families in an intergenerational household, these fears are legitimate as caring for one’s elders is of paramount importance. There was also much uncertainty associated with adapting to online learning and new modes of assessment. Students’ anxiety about wasting time or potentially losing a semester of study or delayed graduation was common. Previous studies demonstrate that a lack of tolerance for uncertainty is a predictor of psychological distress, in addition to its correlation with elevated levels of stress and low levels of resilience.Citation22–24 Our findings are consistent with a contemporaneous study that reported students are negatively affected during times of uncertainty and when limited information available.Citation25 The internal conflict domain findings were also consistent with the Coping Reservoir Model which, for some students, undermined their belief in their abilities and lead to questioning their choice of major.Citation10 For others, the media attention surrounding the role of frontline workers during the pandemic consolidated students’ resolve to pursue their health major, with many expressing a newfound pride. The pandemic provided an opportunity for health profession students to consolidate their professional identity connecting them to the broader health community and fostered a positive professional impression.Citation26–29 Time and energy demands brought about by the new mode of teaching and learning was a major theme that the students discussed. The abrupt shift to online learning brought about many temporal and psychological challenges that undermined some students’ confidence. Not only was it a new way of engaging with the academic content, but also students had to grapple with this material independently, isolated from their peers. A study reported that the change to online learning led the students to feel unable to master and comprehend their materials.Citation30,Citation31

Countering the negative inputs, several constructive factors contributed positively and replenished students’ coping reservoirs. Resilience-building efforts were greatly facilitated by various types of psychosocial support offered by family, peers, and faculty. Earlier studies point to the efficacy of psychosocial support in decreasing students’ anxiety, reducing burnout, and improving resilience.Citation32–34 Despite being in lockdown, students actively sought out a range of activities to help them cope with their new circumstances. Though many of these activities were undertaken independently, some involved other family members and others were online which circumvented the constraints imposed by social distancing. Many embarked on healthy living campaigns in a bid to relieve stress and bolster their resilience. Evidence from two pre-pandemic and one contemporaneous study have demonstrated that meditation, exercise, sleep hygiene, and positive social relationships are effective in improving well-being and promoting resilience.Citation25,Citation35,Citation36

Aside from an isolated reference to the role of alumni and faculty in helping students navigate their studies during the pandemic, the mentorship theme was understated. This is consistent with the findings of another study that also employed this model.Citation11 This finding may indicate an unfamiliarity with the term “mentorship;” aside from fledgling mentorship programs in the College of Medicine no formal mentoring has been established in the other colleges. Or perhaps the relative absence of this theme mirrors a more top-down approach to knowledge sharing and the pervasive paternalistic approach to health profession education in the region. Elsewhere, mentorship programs are gaining increased momentum and are being incorporated into medical and health curricula recognized as they are crucial for developing students’ knowledge, skills, professionalism and personal growth.Citation37 Mentoring, accompanied by other educational interventions have the capacity to improve resilience if implemented early in the health profession career.Citation38 Mentors can be faculty members, academic administrators, peers, senior students, or alumni and serve as role models to students.Citation10 Furthermore, it has been argued that it would be beneficial and appropriate for mentors to share some degree of personal disclosure with their mentees with a discussion on how they dealt with it.Citation10 Therefore, mentoring programs can provide psychosocial and career-related support with the potential of reducing burnout.Citation39 Student-led mentorship programs for junior students have been encouraged as they reduce stress and burnout.Citation8

Lockdown was a particularly alienating experience for individuals who were surrounded by extensive families who often did not appreciate student stress and the challenges associated with studying for a degree at home. For many students, the university is considered a place they spend a lot of time and prosper in both mentally, academically and socially,Citation40 so having that taken away from them, may have adversely impacted their psychosocial growth.Citation41 The precautionary measures taken during the pandemic may have amplified adolescent vulnerabilities, largely in part due to not having close contact with their peers.

According to Erikson’s psychosocial development theory, university students are at the young adulthood stage during which identity formation and developing relationships, independent of their families, take place.Citation41 During this phase of development, peer groups are foregrounded as familial relationship recede, giving students opportunities to explore their values and experiment. Lockdown inhibited these social interactions and may have contributed to some students’ feelings of loneliness and isolation. Loneliness in undergraduate students has been significantly associated with increased mental health issues including exacerbation of depression, stress, and anxiety.Citation42 Notably, these mental health issues were mentioned by many of the students suggesting that their welfare was compromised by forced social distancing.

Labeling a reservoir as a coping mechanism implies that students are only suffering from negative experiences.Citation11 However, since the reservoir is built on both positive and negative experiences, MacArthur & Sikorski proposed changing the emphasis to hope. In their study, the key source of hope for medical students was the doctor-patient relationship they will be part of once they start practicing. This is different from the findings of this study, where hope for health profession students during the pandemic differs from hope of being effective health professionals in the future to hope of playing a key role during the pandemic.

This study contributes to a growing body of literature on health profession students’ wellbeing, particularly during a pandemic. To our knowledge, this is the first qualitative study during the pandemic that focused on health profession students within one institution rather than restricting it to one profession. Burnout is a growing concern amongst the health professions and is a condition that can have serious long-term consequences for practitioners’ mental health, professionalism and capacity to express empathy.Citation17,Citation43 It can also affect interprofessional relationship with other health professionals and patients.Citation43 Furthermore, the need to improve health profession students’ resilience is evident, as concerns about retention rates and graduates’ readiness for the demands of the twenty first century workplace increase.Citation1 Therefore, academic institutions should deliver interventions centered around coping strategies that are applicable to all health profession students.

While the Coping Reservoir Model is useful for identifying inputs affecting the individual, it does not consider organizational factors, which are of paramount importance as resilience is an interplay between an individual, their environment, and organizational factors.Citation44 Despite the fact that most interventions focus on individuals, organizations need to incorporate resilience into health curricula and integrate it into institutional strategies.Citation1 Initiatives that are multifaceted with a focused approach to the learning environment are more likely to be successful and have been shown to decrease depression and anxiety.Citation45 In order to support student development and consolidate health professional identities, universities should also offer students a variety of resources for emotional and psychological support, develop longitudinal electives, and encourage theme-based learning communities.Citation45 Furthermore, some students had the impression that some faculty were ill-equipped to handle online teaching, hence, programs that promote faculty wellbeing are crucial to developing a learning environment that supports students and fosters resilience.Citation45

One limitation of this study is that focus group discussions may have prevented some students from disclosing personal experiences. However, many students were open and willingly shared their personal experiences of vulnerability. Other limitations include the possibility of recall bias as data collection took place four months after the spring semester concluded. While pharmacy students comprised approximately half (n = 24) of the participants, the results may have been skewed in favor of their responses. However, the research cohort contained a relatively homogeneous group of health profession students (e.g., similar age, live at home with parents, live locally, raised in Qatar, Arabic speaking, Muslim). Further, these students were subject to similar disruptions in their educational experiences during the pandemic as evident from the quotes extracted from answers provided by students across QU Health colleges. The absence of mentorship as a replenishing factor may be due to the uneven distribution of mentorship programs across colleges (i.e. only college of medicine have it), which is a limitation of a single site study, though learners from diverse health professions were included.

Only health professions students from one university participated in the study which may limit applicability to other academic institutions. Although, Qatar University is the national university in the country and by far the largest, it is recommended, for future research, to include other health institutions to have a better representation of health profession students across the country. Additionally, this study excluded students’ personal attributes such as temperament and traits. Future studies may therefore consider quantitative and qualitative study design to measure the correlation of these personal attributes with resilience and burnout.

Conclusion

Utilizing the Coping Reservoir Model, this study provides insight into the experiences of Middle Eastern health profession students at Qatar University during the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. The model seems to be a useful tool for the analysis of students’ well-being during a pandemic during which health profession students had to navigate a number of challenges that drained some of their respective coping reservoirs with adverse implications on their wellbeing. Uncertainty and the shift to online learning were the most prominent stressors. Students discussed experiences of replenishing their coping reservoir through psychosocial support, engaging in social/healthy activities, and undertaking intellectually stimulating tasks. The role of health professionals during the pandemic should be showcased and capitalized on to strengthen students’ professional identities. In future, health profession students should not be confined to the sidelines but rather encouraged to volunteer and get involved in whatever capacity deemed appropriate for their level of healthcare training.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Sanderson B, Brewer M. What do we know about student resilience in health professional education? A scoping review of the literature. Nurse Educ Today. 2017;58:65–71. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2017.07.018.

- Ang WHD, Shorey S, Hoo MXY, Chew HSJ, Lau Y. The role of resilience in higher education: A meta-ethnographic analysis of students’ experiences. J Prof Nurs. 2021;37(6):1092–1109. doi:10.1016/j.profnurs.2021.08.010.

- De Hert S. Burnout in healthcare workers: Prevalence, impact and preventative strategies. Local Reg Anesth. 2020;13:171–183. doi:10.2147/lra.S240564.

- Schrijver I. Pathology in the medical profession?: Taking the pulse of physician wellness and burnout. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2016;140(9):976–982. doi:10.5858/arpa.2015-0524-RA.

- Toh SG, Ang E, Devi MK. Systematic review on the relationship between the nursing shortage and job satisfaction, stress and burnout levels among nurses in oncology/haematology settings. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2012;10(2):126–141. doi:10.1111/j.1744-1609.2012.00271.x.

- Wilkinson H, Whittington R, Perry L, Eames C. Examining the relationship between burnout and empathy in healthcare professionals: A systematic review. Burn Res. 2017;6:18–29. doi:10.1016/j.burn.2017.06.003.

- Folkman S, Moskowitz JT. Coping: pitfalls and promise. Annu Rev Psychol. 2004;55:745–774. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141456.

- Fares J, Al Tabosh H, Saadeddin Z, El Mouhayyar C, Aridi H. Stress, burnout and coping strategies in preclinical medical students. N Am J Med Sci. 2016;8(2):75–81. doi:10.4103/1947-2714.177299.

- Stoffel JM, Cain J. Review of grit and resilience literature within health professions education. Am J Pharm Educ. 2018;82(2):6150. doi:10.5688/ajpe6150.

- Dunn LB, Iglewicz A, Moutier C. A conceptual model of medical student well-being: promoting resilience and preventing burnout. Acad Psychiatry. 2008;32(1):44–53. doi:10.1176/appi.ap.32.1.44.

- MacArthur KR, Sikorski J. A qualitative analysis of the coping reservoir model of pre-clinical medical student well-being: human connection as making it ‘worth it. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):157. doi:10.1186/s12909-020-02067-8.

- Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, et al. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. IJERPH. 2020;17(5):1729. doi:10.3390/ijerph17051729.

- Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395(10227):912–920. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8.

- Wald HS. Optimizing resilience and wellbeing for healthcare professions trainees and healthcare professionals during public health crises – practical tips for an ‘integrative resilience’ approach. Med Teach. 2020;42(7):744–755. doi:10.1080/0142159X.2020.1768230.

- Imeri H, Jadhav S, Barnard M, Rosenthal M. Mapping the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on pharmacy graduate students’ wellness. Res Soc Administrative Pharm. 2021;17(11):1962–1967. doi:10.1016/j.sapharm.2021.02.016.

- Alghamdi S, Ali M. Pharmacy students’ perceptions and attitudes towards online education during COVID-19 lockdown in Saudi Arabia. Pharmacy (Basel, Switzerland). 2021;9(4):169. doi:10.3390/pharmacy9040169.

- Bullock G, Kraft L, Amsden K, et al. The prevalence and effect of burnout on graduate healthcare students. Can Med Educ J. 2017;8(3):e90–e108. doi:10.36834/cmej.36890.

- Ishak W, Nikravesh R, Lederer S, Perry R, Ogunyemi D, Bernstein C. Burnout in medical students: a systematic review. Clin Teach. 2013;10(4):242–245. doi:10.1111/tct.12014.

- Creswell JW, Creswell JD. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 2017.

- Ritchie J, Spencer L. Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. In: Analyzing Qualitative Data. London: Routledge; 2002:187–208.

- Sulaiman R, Ismail S, Shraim M, El Hajj MS, Kane T, El-Awaisi A. Experiences of burnout, anxiety, and empathy among health profession students in Qatar University during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychol. 2023;11(1):111. doi:10.1186/s40359-023-01132-3.

- Simpkin AL, Khan A, West DC, et al. Stress from uncertainty and resilience among depressed and burned out residents: A cross-sectional study. Acad Pediatr. 2018;18(6):698–704. doi:10.1016/j.acap.2018.03.002.

- Lally J, Cantillon P. Uncertainty and ambiguity and their association with psychological distress in medical students. Acad Psychiatry. 2014;38(3):339–344. doi:10.1007/s40596-014-0100-4.

- Burns D, Dagnall N, Holt M. Assessing the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on student Wellbeing at Universities in the United Kingdom: A conceptual analysis. Front Educ. 2020;5:204. doi:10.3389/feduc.2020.582882.

- Schlesselman LS, Cain J, DiVall M. Improving and restoring the well-being and resilience of pharmacy students during a pandemic. Am J Pharm Educ. 2020;84(6):ajpe8144. doi:10.5688/ajpe8144.

- Moula Z, Horsburgh J, Scott K, Rozier-Hope T, Kumar S. The impact of Covid-19 on professional identity formation: an international qualitative study of medical students’ reflective entries in a Global Creative Competition. BMC Med Educ. 2022;22(1):545. doi:10.1186/s12909-022-03595-1.

- Byram JN, Frankel RM, Isaacson JH, Mehta N. The impact of COVID-19 on professional identity. Clin Teach. 2022;19(3):205–212. doi:10.1111/tct.13467.

- Nie S, Sun C, Wang L, Wang X. The professional identity of nursing students and their intention to leave the nursing profession during the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. J Nurs Res. 2021;29(2):e139. doi:10.1097/jnr.0000000000000424.

- Al-Naimi H, Elkattan B, Mohammed H, Shafei L, Elshazly M, El-Awaisi A. A SWOC analysis on the impact of COVID-19 through pharmacy student leaders’ perspectives. Pharm Educ. 2021;20(2):226–233. doi:10.46542/pe.2020.202.226233.

- Khalil R, Mansour AE, Fadda WA, et al. The sudden transition to synchronized online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic in Saudi Arabia: a qualitative study exploring medical students’ perspectives. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):285. doi:10.1186/s12909-020-02208-z.

- Bawadi H, Shami R, El-Awaisi A, et al. Exploring the challenges of virtual internships during the COVID-19 pandemic and their potential influence on the professional identity of health professions students: A view from Qatar University. Front Med (Lausanne). 2023;10:1107693. doi:10.3389/fmed.2023.1107693.

- Bíró É, Veres-Balajti I, Kósa K. Social support contributes to resilience among physiotherapy students: a cross sectional survey and focus group study. Physiotherapy. 2016;102(2):189–195. doi:10.1016/j.physio.2015.05.002.

- Cao W, Fang Z, Hou G, et al. The psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatry Res. 2020;287:112934. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112934.

- Bawadi H, Al-Moslih A, Shami R, et al. A qualitative assessment of medical students’ readiness for virtual clerkships at a Qatari university during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Med Educ. 2023;23(1):186. doi:10.1186/s12909-023-04117-3.

- Lemay V, Hoolahan J, Buchanan A. Impact of a yoga and meditation intervention on students’ stress and anxiety levels. Am J Pharm Educ. 2019;83(5):7001. doi:10.5688/ajpe7001.

- Wolf MR, Rosenstock JB. Inadequate sleep and exercise associated with burnout and depression among medical students. Acad Psychiatry. 2017;41(2):174–179. doi:10.1007/s40596-016-0526-y.

- Nimmons D, Giny S, Rosenthal J. Medical student mentoring programs: current insights. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2019;10:113–123. doi:10.2147/AMEP.S154974.

- Rogers D. Which educational interventions improve healthcare professionals’ resilience? Med Teach. 2016;38(12):1236–1241. doi:10.1080/0142159X.2016.1210111.

- Pethrick H, Nowell L, Oddone Paolucci E, et al. Psychosocial and career outcomes of peer mentorship in medical resident education: a systematic review protocol. Syst Rev. 2017;6(1):178–178. doi:10.1186/s13643-017-0571-y.

- Markoulakis R, Kirsh B. Difficulties for university students with mental health problems: A critical interpretive synthesis. Rev Higher Educ. 2013;37(1):77–100. doi:10.1353/rhe.2013.0073.

- Erikson EH. Identity: Youth and Crisis. New York: WW Norton & Company; 1968.

- Richardson T, Elliott P, Roberts R. Relationship between loneliness and mental health in students. J Public Mental Health. 2017;16(2):48–54. doi:10.1108/JPMH-03-2016-0013.

- Cho E, Jeon S. The role of empathy and psychological need satisfaction in pharmacy students’ burnout and well-being. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19(1):43. doi:10.1186/s12909-019-1477-2.

- Balme E, Gerada C, Page L. Doctors need to be supported, not trained in resilience. BMJ. 2015;351:h4709. doi:10.1136/bmj.h4709.

- Slavin S. Reflections on a decade leading a medical student well-being initiative. Acad Med. 2019;94(6):771–774. doi:10.1097/acm.0000000000002540.