Abstract

Issue

Triggered by the lived experiences of the authors–one junior career, female, and black; the other senior career, male, and black–we provide a critical, sociological overview of the plight of racial/ethnic minority students in medical education. We analyze the concepts of categorization, othering, and belonging in medical education, which we use to shed light on the psychological and academic consequences of overgeneralizing social categories.

Evidence

The ability to categorize people into different social groups is a natural, subconscious phenomenon. Creating social groups is believed to aid people in navigating the world. This permits people to relate to others based on assumed opinions and actions. Race and gender are two primary dimensions of categorization, with race or ethnicity being a particularly salient category. However, over-generalization of social categories can lead the categorizer to think, judge, and treat themselves and members of a perceived group similarly, leading to prejudice and stereotyping. Social categorization also occurs in educational settings across the globe. The consequences of categorization may influence a student’s feelings of belonging and academic success.

Implications

Our analysis reflects on how to promote equitable opportunities for ethnic minority medical trainees through the lens of those who have experienced and succeeded in an inequitable system. By revisiting the social and psychological constructs that determine and influence the academic progress and success of minority students in medical education, we discovered that more engagement is (still) needed for critical discourse on this topic. We expect such conversations to help generate new insights to improve inclusion and equity in our educational systems.

Introduction

With the ongoing surge in global migration, more people from different ethnic and cultural backgrounds co-exist within single communities. With the diversity in language, skin color, and ethnicity/race of these people, different categorizations have emerged in those communities with significant implications, i.e., discrimination, prejudice, and stereotyping of individuals and groups of people.Citation1 Creating categories is believed to aid people in navigating the social world, as it helps people organize an array of knowledge about human attributes.Citation2 Although the process of social categorization can be anticipated, these categories and their meanings are social constructions.Citation3

There are two approaches that people often use to categorize, namely (1) categorizations emphasizing shared traits and (2) those that minimize differences.Citation4 Globally, demographic features such as gender, age, ethnicity, personality interests, and income or occupation are often used to categorize people into different groups.Citation5 However, unlike distinct categories such as gender and age, race or ethnicity is particularly salient.Citation6 For example, race as a category is widely (and incorrectly) used as a collective categorization of different groups of people who possess particular physical attributes, such as skin color, hair texture, or apertures of the eyelids.Citation7 This often leads to ethnic minority and majority group categorizations based on physical appearances. It is also a consequence of the observed diversity resulting from increased migration and involuntary displacement of people globally. Currently, there is no internationally agreed definition of “ethnic minority” (EM) in the literature.Citation8 However, in this paper, we describe EM groups as socially constructed categories of people with a different racial, ethnic, or national background from the dominant majority within a particular society at a particular time.Citation9

EM individuals are likely to experience negative consequences of categorization, such as discrimination and racism, which can have harmful effects on their feelings of belonging and professional success.Citation10–12 For example, in a predominately white society, dark skin can be identified as characteristic of an EM group and regularly and incorrectly used as a marker to attribute certain disorders, crime, and violence, causing the stigmatization of an entire category of people.Citation13 Subsequently, such categorizations tend to stick and are sustained because any information that validates stereotypes is easier to remember than information that refutes them.Citation14,Citation15 Furthermore, people who are perceived by others or themselves as distinct, racially, culturally, and ethnically risk falling victim to the consequences of differentiation and stereotyping associated with categorization, i.e., discrimination, isolation, lack of belonging, and loneliness. Unsurprisingly, social categorization is not limited to single institutions but occurs in all sectors of society, including educational institutions such as universities and schools.

EM students are frequently discriminated against based on their race and ethnicity (or difference). There is reason to believe that the presence of discrimination and absence of belonging in an educational setting significantly predicts academic outcome, motivation, and effort in education. Citation16–18 Racial or ethnic discrimination is a serious global issue that affects EM students including medical students, despite the need for diverse medical professionals to meet the need of a increasingly diverse communities.Citation19–22 It is imperative to understand the process and consequences of categorization and the role social constructed factors like othering and belonging plays on EM students’ academic outcome and wellbeing.

The factual case described below is of a former medical student and researcher named Jane (not her real name) and is used to showcase what and how various students experience othering and categorization in medical education.

The case of Dr. Jane

Dr. Jane is a black African woman conducting a qualitative thesis project on a topic that reflects her educational experience as an African in Europe. While conducting interviews, she observed that she shared similarities with her participants who reported moving from their home countries to study in Europe and “suddenly” becoming categorized as EM students. They reported that this new category came with feelings of being othered, discriminated against, targeted by microaggressions, and excluded. Concurrently, they reported that they found belonging and were able to create a community among other EM students. These were all feelings that Dr. Jane knew all too well after experiencing racist remarks from teachers and students and feelings of exclusion during her study in Europe. All these experiences affected her sense of belonging and academic performance. However, like the participants in her survey, Dr. Jane built a community with other minority students, which improved her sense of well-being and performance, academically.

The narrative above describes the experiences of a newly labeled EM medical student who studied in a relatively conservative Eastern European country and noticed the same lived experiences among EM students in Western Europe. Similar findings were present in education literature where EM students reported racial categorization and its consequences, i.e., othering, discrimination, and isolation and which led to increased dropout rates, poor academic performance, and limited professional attainment.Citation23–25 Unfortunately, there is a dearth of information about how socially constructed concepts, like othering and belonging, affect the lives of EM students. Therefore, it is crucial to understand these concepts and, importantly, their effects on EM students to create inclusive spaces in medicine and help promote belonging. In so doing, opportunities can be created to help EMs attain their academic and professional goals. This analysis, therefore, explores the sociological and psychological perspectives of socially constructed concepts, i.e., othering and belonging, by authors with lived experiences of such phenomena. Our objective is to understand how EM medical students experience othering and discrimination and its impact on their feelings of belonging and academic performance. Through this exercise, we expect to create (more) awareness of othering and belonging in medical schools. Also, we aim to highlight the effects of these constructs on EM students and inform medical schools on the need for inclusive and diverse spaces for EM students to grow and thrive.

The social construct of othering evolving from categorizations

Creating categories through vocabulary to describe race or ethnicity does not seem harmful. However, overgeneralization of such categories can lead the categorizer to think, judge, and treat themselves and members of a perceived “dominant” group similarly, leading to outgroup homogeneity, prejudice, and self-stereotyping.Citation15,Citation26 To be part of an “in-group” is a significant phenomenon of privilege in which individuals in that group build communities and security and possess the power to frame the “out-group” as an “other” and treat them unfairly.Citation27 Othering can simply be defined as the “simultaneous construction of the self or in-group, and the other or out-group in mutual and unequal opposition through identification of some desirable characteristics that the self (in-group) embodies, and that the other (out-group) lacks.Citation28 This discursive process of separating “We” from “Other” as a process of creating hierarchies of power implies that the “other” is not just (implicitly) inferior but radically alien.Citation27 As a result, an impenetrable boundary between “the self” and “other” is created that makes it easier to justify social exclusion and discrimination due to differences found between “them and us.”Citation27 Stereotypes subsequently emerge, and in our analysis, it is the process whereby generalizations about attributes or characteristics of a group of people are formed.Citation29 Stereotypes undermine people’s social standing by “othering” them to a specific attribute or disposition that leads to discrimination.Citation30 In this article, we refer to discrimination as the unequal treatment of persons or groups based on (their) race or ethnicity.Citation31 This process of discriminating and othering can lead to alienation and perpetuation of group stereotypes, prejudice, and inequality.Citation32 It creates the “us versus them” mindset, which is socially constructed and not only detrimental to society but also dangerous in academic (learning) settings.

For example, Europe defined “Orientalism” and its identity in an exoticized, reductionist, and alienating fashion.Citation33 BhabhaCitation34 affirmed that the use of the racial stereotype of “Orientals” to describe people of East Asian descent validated the institutionalized systems of racist imperial administration over the “inferiors” (Orientals).Citation34,Citation35 The stereotype then became derogatory and aggressive discourses, creating divisions between the colonizers and colonized. The classroom could be considered a mirror of this type of social system where the hierarchical division of dominance leads to the exclusion and discrimination of a certain group of students, thereby constituting an ideal context for teachers and administrators to develop stereotypes and biases of EM students.Citation36,Citation37

Research from educational settings indicates that tutors often assume that students from the “dominant” group share equal views as fellow students from the “other” group.Citation38 These situations result in EM students feeling “othered” or “hyper-visible,” like some form of exotic token in comparison with the norm, i.e., the “in-group.”Citation39 There is research highlighting this fact, stating that “schools are cultural contexts that have the power and potential to promote students’ cultural assets or to ‘other’ youths in a way that keeps them from creating meaningful academic identities.”Citation40 The “other” minority ethnic group often appears exotic, fascinating, deviant, repugnant, or incomprehensible.Citation39 However, when observing what it means to be the “other,” one uncovers an “overpowering feeling” of being on the outside looking in. This “overpowering feeling” could mean being an EM placed within a culture created to fit the majority or an individual feeling excluded because they do not fit the standard or the norm.Citation41 As such, we observe an interplay of socially constructed and reconstructed preconceptions of the “Self” and the “Other.” Therefore, othering can build theories of who belongs and who does not belong by denoting the ‘other’ with undesirable connotations, which creates stereotypes and leads to discriminatory behaviors toward students, and eventually impacts their academic performance and wellbeing.Citation42

The impact of othering on ethnic minority students in medical school

Othering in academic settings and the struggle of EM students and faculty to integrate academically are widespread global issues.Citation43 EM students face inequality at all stages of their education and are less likely to enjoy the student experience and are more likely to drop out of school.Citation44 Categorization of racial minorities comes in different forms, but racial spotlighting, fascination, and ignoring are three of the more prominent forms of discrimination in school settings.Citation45 In the Netherlands, EM individuals (and their offspring) are often referred to as “allochtoon,” which literally means “emerging from another soil.”Citation46 The proportion of such EM medical students, doctors, and faculty in Dutch academic institutions is disproportionately low compared to the general population Citation47 and is estimated at roughly 27%.Citation46,Citation48 Furthermore, these students have lower completion rates on average compared to ethnic majority (i.e., white) Dutch students.Citation49

Research on teaching, learning, assessment, and curricular development in medical education has revealed a few issues that can harm the success of EM students in medicine.Citation50 For example, research in Dutch universities showed that students who identified as EM were less academically integrated and advanced slower than their ethnic majority peers.Citation51 Compared to an ethnic majority, these students were less likely to pursue medical careers and scored poorer on preclinical and clinical education knowledge and abilities exams. Compared to the “majority” students, instead of learning, they spent more time struggling with racial discrimination and harassment in the classroom and clinical settings. They also had to deal with implicit biases from residents and patients and experienced severe difficulty qualifying for specialty training.Citation52–54

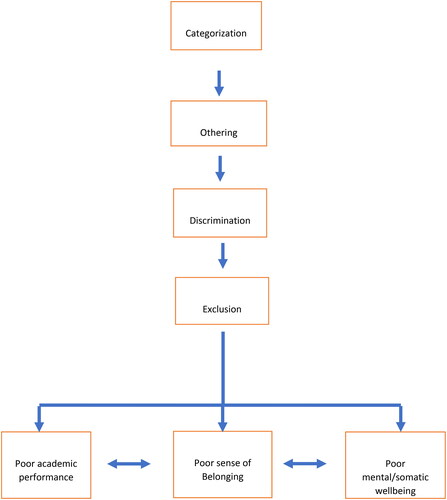

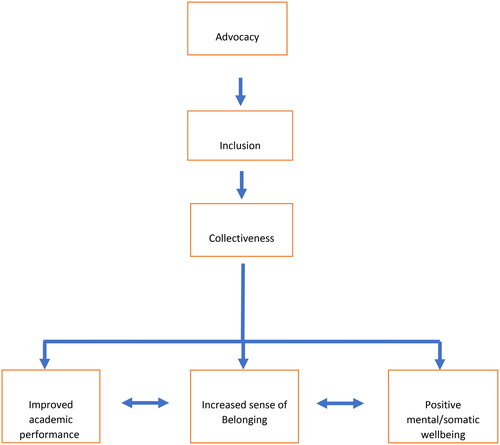

In this way, categorization nurtures discrimination, limits understanding, and encourages continued separation and divergence between students. EM students can also be subject to categorizations containing elements of exotic fascination.Citation39 This might happen when peers ask the student to speak for their race or ignore their racial difference at times when subject content may focus on it. Students who are made to feel excluded from the dominant group may never entirely feel integrated or comfortable in educational settings.Citation55 Furthermore, the othering of EM students in such exotic and reductive ways places them in an inferior position compared to ethnic majority teachers and students. Moreover, once groups are established, and strong assumptions are formed, the consequence is that stereotyping will diminish an individual’s ability to feel belonging or inclusion, which influences mental well-being and performance within educational settings.Citation15 So, while research shows that EM medical students underperform compared to ethnic majority students, it is important to acknowledge and resolve the impact of othering, isolation, and discrimination on wellbeing and academic performance ().Citation19

Belonging, the antithesis of othering

Othering and belonging are conceptual frameworks that allow us to observe and identify a set of structural processes and dynamics while being sensitive to the specifics of each instance.Citation42 The theoretical underpinnings for discrimination and belongingness may be found in psychology. It is based on the premise that individuals need to belong (to a group or community) and feel accepted and supported to succeed in life.Citation56 “Belonging” is a person’s subjective sense of profound connection to social groups, physical locations, and individual and communal experiences. Belonging is a basic human desire linked to various positive mental, physical, social, economic, and behavioral effects.Citation57

Academic performance, motivation, and effort in school, including medical education, are all greatly influenced by a sense of belonging within the educational setting.Citation58 For example, medical students with strong social networks outperform those who feel discriminated against by their professors and peers.Citation59 Additionally, The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Johnson Foundation at Wingspread’s declaration on school connectedness showed that academic performance is linked with the ability to feel connected.Citation60 According to research, medical education connectedness impacts mental health, academic achievement, and outcomes.Citation25 Students’ motivation and classroom engagement also were found to improve when they experienced belonging with their teachers and peers.Citation61,Citation62 Belonging at medical institutions is essential to achieving successful psychosocial adjustment. It justifies the need for educational institutions to implement interventions that encourage belonging, acceptance, and inclusion. Evidence suggests that the sense of being part of a group of people and not being discriminated against buffers the effects of depression.Citation11 For one to belong, two opposing parties must be involved: the “outsider” who wants to belong and the party with the power to ‘grant’ belonging.Citation63 Belonging at medical institutions is an integral part of successful psychosocial adjustment and offers justification for schools to engage in interventions that promote belonging, acceptance, and inclusion. Belongingness entails a steadfast commitment to tolerating and respecting differences, ensuring that all students feel part of the educational environment. Medical students who feel at home in medical institutions have a greater chance of graduating and obtaining a degree, as formal academic integration is vital in the quality of learning and educational attainment.Citation64,Citation65 Ed and ShefflerCitation66 stated that “the type of environment that a teacher creates and encourages can either increase or decrease a student’s ability to learn and feel comfortable as a member of the class.”Citation66

These findings are consistent with a synthesis of publications on the topic performed by the CDC in 2018, which concluded that belonging was associated not only with student-peer relationships but also with peer groups, the educational environment, and society.Citation57,Citation67 Therefore, the only practical solution to the issue of discrimination in medical schools is one involving inclusion and belongingness, as these institutions arguably offer the second most important set of relationships available to medical students ().Citation68

Way forward

In recent years, the attention paid to diversity, equity, and inclusion in medical education has grown, emphasizing the importance of researching and educating ourselves about othering and belonging among marginalized students in medical education. For example, medical schools have begun incorporating anti-racism education for their staff that focus on learning about the culture of the EM “others.”Citation69 However, implementing anti-racism programs with a focus on cultural, ethnic, or racial education does not completely solve the underlying problem of discrimination in education. Incorporating frameworks like critical race theory (CRT), which highlight the underlying mechanisms of racism and discrimination, is important.Citation70 CRT provides a framework for understanding power and privilege in education, emphasizing that power is unequally distributed in society and that some groups have more privilege and influence than others. CRT aids in identifying how educational institutions might be rebuilt to be fairer by studying power and privilege in education.Citation71 In addition, CRT offers an approach to understanding the experiences of students who are othered, stereotyped, and discriminated against based on their race or ethnicity. CRT can allow medical educators to reflect on how racism affects these students’ educational experiences and how education might be changed to better meet their needs by placing the experiences of these students at the center of the discussion.Citation72 It is, therefore, important for institutions to note that enabling success will require a holistic approach. An approach that sets out to identify and address othering and discrimination in medical institutions. The program structure can be co-developed with EM members, promoting diversity without tokenism and exoticization and creating specific academic integration programs to promote belonging for EM students.Citation38 Furthermore, institutions are recommended to seek and create an educational climate where EM medical students are empowered to report their negative experiences and have confidence that the university will act on their behalf by rehabilitating or replacing systems and individuals who discriminate.

Similarly, implicit bias training is currently happening in several medical institutions with varying degrees of success.Citation73 This is important as medical educators, program designers, and tutors delivering courses and research must be aware of possible personal biases.Citation19 However, institutions must continually assess their presumptions about students, including any preconceptions based on race or ethnicity, and change their attitudes, convictions, and actions accordingly. We recommend that medical institutions create a diversity and inclusion committee that includes members of EM groups, students, teachers, and external experts to analyze growth toward inclusive educational spaces for EM students consistently. In conclusion, medical institutions need to recognize that EM students do not constitute a homogeneous group and that strengthening faculty’s ability, diversity, and teaching methods to foster cultural sensitivity is essential.

Concluding remarks

Global migration has resulted in the evolution of several communities made up of diverse groups of people with different backgrounds, ethnicities, and characteristics. This diversity and the need for direction ultimately promoted categorization of people into groups to aid social navigation within these communities. Categorizing individuals into different racial or ethnic groups and the meanings associated with these socially constructed categories account for phenomena such as othering, stereotyping, discrimination, and exclusion. These social constructs consequently have significant implications for individuals and groups in these communities.

Social categorization often leads to othering. Unfortunately, it also occurs in schools, where it can perpetuate racial or ethnic discrimination by reinforcing stereotypes and prejudices toward EM students. Stereotypes undermine the social standing of students, creating an “us versus them” mindset. This in turn, is detrimental and dangerous in academic settings like medical schools. In classrooms for example, EM medical students feel either othered as racially exotic or experience their racial differences being ignored.Citation39 Such discriminatory practices can lead to feelings of exclusion and alienation, hindering academic success and student well-being.

It is crucial to recognize the harmful effects of othering and work toward reducing discrimination, prejudice, and racism by promoting inclusion and belonging. Also, it is vital to acknowledge and challenge the assumptions and biases that underlie many of our social institutions and practices. This requires a willingness to examine personal beliefs and behaviors and to engage in difficult conversations about race, ethnicity, and other forms of difference. Educators and administrators should receive training in cultural humility, which includes understanding and respecting ethnic differences and avoiding stereotypes and biases. Medical schools should also prioritize creating an inclusive environment where EM students feel a sense of belonging. This can include initiatives such as diversifying the curriculum, promoting multiculturalism, and providing resources for students to explore their personal identity. By doing so, we can work toward building a more equitable academic environment where everyone can thrive.

Authors’ reflexivity

OA is a junior career, female, and black academic researcher and physician. JB is a senior career, male and black academic physician, researcher, and clinical leader. Triggered by our different lived experiences as EM scholars, our analysis intends to understand better the mechanisms that hamper equitable learning opportunities in medical education. We also intended to explore the social constructs of othering and belonging, which can positively influence the progress and success of EM groups in medical education. We reexamined these concepts to present potential recommendations for solutions. In summary, our review offers (new) thinking on how to frame current concepts and promote equitable opportunities for marginalized medical trainees through the lens of peers who have experienced and succeeded in inequitable systems.Citation74

Authors’ contributions

All authors contributed to the study’s conception and design. OA and JOB did material preparation and literature review. OA wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and JOB commented on and edited the initial and subsequent versions. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Dovidio JF, Hewstone M, Glick P, Esses VM. The SAGE Handbook of Prejudice, Stereotyping and Discrimination. London: SAGE Publications Ltd; 2022. doi:10.4135/9781446200919.

- Fiske ST. Social Beings: Core Motives in Social Psychology. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons inc. [distributor]; 2010.

- Crisp RJ, Hewstone M. Multiple social categorization. In: Zanna, MP, eds, Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. Vol. 39. Elsevier Academic Press; 2007:163–254. doi:10.1016/S0065-2601(06)39004-1.

- Abrams D. Social identity, psychology of. In: Smelser NJ, Baltes PB, eds. International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences. Oxford: Pergamon; 2001:14306–14309. doi:10.1016/b0-08-043076-7/01728-9.

- de Carvalho RJ, Gordon W. Allport on the nature of prejudice. Psychol Rep. 1993;72(1):299–308. doi:10.2466/pr0.1993.72.1.299.

- Markman AB, Wisniewski EJ. Similar and different: the differentiation of basic-level categories. J Exp Psychol Learn Mem Cogn. 1997;23(1):54–70. doi:10.1037/0278-7393.23.1.54.

- Gaither SE, Pauker K, Slepian ML, Sommers SR. Social belonging motivates categorization of racially ambiguous faces. Soc Cogn. 2016;34(2):97–118. doi:10.1521/soco.2016.34.2.97.

- United Nations. Minorities. 2021. https://www.un.org/en/fight-racism/vulnerable-groups/minorities.

- Ford CL, Harawa NT. A new conceptualization of ethnicity for social epidemiologic and health equity research. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71(2):251–258. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.04.008.

- Twenge JM, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Age, gender, race, socioeconomic status, and birth cohort difference on the children’s depression inventory: A meta-analysis. J Abnorm Psychol. 2002;111(4):578–588. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.111.4.578.

- Nadimpalli SB, James BD, Yu L, Cothran F, Barnes LL. The association between discrimination and depressive symptoms among older African Americans: the role of psychological and social factors. Exp Aging Res. 2015;41(1):1–24. doi:10.1080/0361073X.2015.978201.

- Parr EJ, Shochet IM, Cockshaw WD, Kelly RL. General belonging is a key predictor of adolescent depressive symptoms and partially mediates school belonging. School Mental Health. 2020;12(3):626–637. doi:10.1007/s12310-020-09371-0.

- Sampson RJ. Great American City: Chicago and the Enduring Neighborhood Effect. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press; 2012.

- Trope Y, Thompson EP. Looking for truth in all the wrong places? Asymmetric search of individuating information about stereotyped group members. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1997;73(2):229–241. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.73.2.229.

- Steele CM, Aronson J. Stereotype threat and the intellectual test performance of African Americans. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1995;69(5):797–811. doi:10.1037//0022-3514.69.5.797.

- Sánchez B, Colón Y, Esparza P. The role of sense of school belonging and gender in the academic adjustment of latino adolescents. J Youth Adolescence. 2005;34(6):619–628. doi:10.1007/s10964-005-8950-4.

- McManus IC, Richards P, Winder B, Sproston K, Styles V. Medical school applicants from ethnic minority groups: identifying if and when they are disadvantaged. BMJ. 1995;310(6978):496–500. doi:10.1136/bmj.310.6978.496.

- Smith S. Exploring the black and minority ethnic (BME) student attainment gap: what did it tell us? Actions to address home BME undergraduate students’ degree attainment. JPAAP. 2016;5(1):48–57. doi:10.14297/jpaap.v5i1.239.

- Stegers-Jager K, Themmen A. Dealing with diversity in medical education. Med Educ. 2013;47(8):752–754. doi:10.1111/medu.12251.

- Care S. A synthesis of research evidence. Black and minority ethnic (BME) students’ participation in higher education: improving retention and success. 2009:1–73.

- Hammond JA, Williams A, Walker S, Norris M. Working hard to belong: a qualitative study exploring students from black, Asian and minority ethnic backgrounds experiences of pre-registration physiotherapy education. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19(1):372. doi:10.1186/s12909-019-1821-6.

- Brown CA, Wakefield SE, Bullock AD. The selection of GP trainees in the West Midlands: audit of assessment centre scores by ethnicity and country of qualification. Med Teach. 2001;23(6):605–609. doi:10.1080/01421590120091069.

- Woolf K, Potts HW, McManus IC. Ethnicity and academic performance in UK trained doctors and medical students: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2011;342:d901. doi:10.1136/bmj.d901.

- Frumkin LA, Koutsoubou M. Exploratory investigation of drivers of attainment in ethnic minority adult learners. J Furt High Educ. 2013;37(2):147–162. doi:10.1080/0309877X.2011.644777.

- Goodenow C. The psychological sense of school membership among adolescents: Scale development and educational correlates. Psychol Schs. 1993;30(1):79–90. doi:10.1002/1520-6807(199301)30:1 < 79::Aid-pits2310300113 > 3.0.Co;2-x.

- de Villiers G. The ‘foreigner in our midst’ and the Hebrew Bible. HTS Teol Stud Theol Stud. 2019;75(3):1–7. doi:10.4102/hts.v75i3.5108.

- Brons L. Othering, an analysis. Transci. J. Glob. Stud. 2015;6:69–90.

- Woodward K. Concepts of identity and difference. In: Watson S, Barnes AJ, Bunning K, eds., A Museum Studies Approach to Heritage. 2018:429–440. London. doi:10.4324/9781315668505-34.

- Rosenthal L, Overstreet N. Stereotyping. In: Friedman HS, ed., Encyclopedia of Mental Health. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2016:225–229. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-397045-9.00169-5.

- Pickering M. Stereotyping and stereotypes. 2015. doi:10.1002/9781118663202.wberen046.

- Pager D, Shepherd H. The sociology of discrimination: racial discrimination in employment, housing, credit, and consumer markets. Annu Rev Sociol. 2008;34(1):181–209. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.33.040406.131740.

- Paradies Y, Ben J, Denson N, et al. Racism as a determinant of health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10(9):e0138511. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0138511.

- Clifford J, Said EW. Orientalism. History and Theory. 1980;19(2):204–223. doi:10.2307/2504800.

- Bhabha HK. The Location of Culture. London: Routledge; 1949. https://search.library.wisc.edu/catalog/9910006423202121

- Hook D. The racial stereotype, colonial discourse, fetishism, and racism. Psychoanal Rev. 2005;92(5):701–734. doi:10.1521/prev.2005.92.5.701.

- Moreno-Lopez I. Critical pedagogy in the Spanish language classroom: a liberatory process. Taboo J Cult Educ. 2004;8(1):77–84.

- Linares SM. Othering: towards a critical cultural awareness in the language classroom/la otredad: hacia una conciencia intercultural critica en el aula de ingles. HOW Colom J Teach Eng. 2016;23(1):129.

- Garibay JC. Creating a positive classroom climate for diversity: why the classroom climate is important for learning. UCLA Diver Facul Dev. 2015:1–16. https://equity.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/CreatingaPositiveClassroomClimateWeb-2.pdf

- Zanting A, Meershoek A, Frambach JM, Krumeich A. The “exotic other” in medical curricula: rethinking cultural diversity in course manuals. Med Teach. 2020;42(7):791–798. doi:10.1080/0142159X.2020.1736534.

- Borrero NE, Yeh CJ, Cruz CI, Suda JF. School as a context for “othering” youth and promoting cultural assets. Teach Coll Record. 2012;114(2):1–37. doi:10.1177/016146811211400207.

- Waters C. “Dark strangers” in our midst: discourses of race and nation in britain, 1947-1963. J Br Stud. 1997;36(2):207–238. doi:10.1086/386134.

- Powell J, Menendian S. The problem of othering towards inclusiveness and belonging. Other Belon Expand Circle Hum Concern. 2016:2:14–39.

- Eimers MT, Pike GR. Minority and nonminority adjustment to college: differences or similarities? Res Hig Educ. 1997;38(1):77–97. doi:10.1023/A:1024900812863.

- Connor H, Tyers C, Davis S, Tackey ND. 8Minority_Ethnic_Students.Pdf.; 2003.

- Savira F, Suharsono Y, Tamrat W, et al. No 主観的健康感を中心とした在宅高齢者における 健康関連指標に関する共分散構造分析Title. J Chem Inf Model. 2017;21(2):1689–1699.

- Centraal Bureau Voor de Statistiek. https://www.cbs.nl/.

- Diaz T, Navarro JR, Chen EH. An institutional approach to fostering inclusion and addressing racial bias: implications for diversity in academic medicine. Teach Learn Med. 2020;32(1):110–116. doi:10.1080/10401334.2019.1670665.

- Isik U, Wouters A, Croiset G, Kusurkar RA. “What kind of support do I need to be successful as an ethnic minority medical student?” A qualitative study. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21(1):1–12. pmid = 33402191. doi:10.1186/s12909-020-02423-8.

- Crul M, Wolffs RP. Talent gewonnen, talent verspild? Een kwalitatief onderzoek naar de instroom en doorstroom van allochtone studenten in het Nederlands Hoger Onderwijs 1997-2001 [Dutch]. 2002. Amsterdam Institute for Social Science Research (AISSR), Utrecht: ECHO. https://hdl.handle.net/11245/1.205612 .

- Students NU of. Race for equality: a report on the experiences of Black students in further and higher education. National Union of Students. 2011.

- Beekhoven S. A Fair Chance of Succeeding : Study Careers in Dutch Higher Education. Amsterdam: SCO-Kohnstamm Instituut; 2002.

- Freeman BK, Landry A, Trevino R, Grande D, Shea JA. Understanding the leaky pipeline: perceived barriers to pursuing a career in medicine or dentistry among underrepresented-in-medicine undergraduate students. Acad Med. 2016;91(7):987–993. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000001020.

- Orom H, Semalulu T, Underwood W.III. The social and learning environments experienced by underrepresented minority medical students: a narrative review. Acad Med. 2013;88(11):1765–1777. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182a7a3af.

- Woolf K, Haq I, McManus IC, Higham J, Dacre J. Exploring the underperformance of male and minority ethnic medical students in first year clinical examinations. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2008;13(5):607–616. doi:10.1007/s10459-007-9067-1.

- McGillicuddy D. “They would make you feel stupid” - Ability grouping, Children’s friendships and psychosocial Wellbeing in Irish primary school. Learn Instruct. 2021;75:101492. doi:10.1016/j.learninstruc.2021.101492.

- Baumeister RF, Leary MR. The need to belong: desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychol Bull. 1995;117(3):497–529. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497.

- Allen KA, Bowles T. Belonging as a guiding principle in the education of adolescents. Austr J Educ Dev Psychol. 2012;12:108–119.

- Shih M, Sanchez DT. Perspectives and research on the positive and negative implications of having multiple racial identities. Psychol Bull. 2005;131(4):569–591. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.131.4.569.

- Morris KS, Seaton EK, Iida M, Lindstrom Johnson S. Racial discrimination stress, school belonging, and school racial composition on academic attitudes and beliefs among black youth. Soc Sci. 2020;9(11):191. doi:10.3390/socsci9110191.

- Wingspread declaration on school connections. J Sch Health. 2004;74(7):233–234. doi:10.1111/j.1746-1561.2004.tb08279.x.

- Croninger RG, Lee VE. Social capital and dropping out of high school: benefits to at-risk students of teachers’ support and guidance. Teach Coll Rec. 2001;103(4):548–581. doi:10.1177/016146810110300404.

- Klem AM, Connell JP. Relationships matter: linking teacher support to student engagement and achievement. J Sch Health. 2004;74(7):262–273. doi:10.1111/j.1746-1561.2004.tb08283.x.

- Antonsich M. Searching for belonging - An analytical framework. Geograp Comp. 2010;4(6):644–659. doi:10.1111/j.1749-8198.2009.00317.x.

- Severiens S, Wolff R. A comparison of ethnic minority and majority students: social and academic integration, and quality of learning. Stud High Educ. 2008;33(3):253–266. doi:10.1080/03075070802049194.

- McGarvey A, Brugha R, Conroy RM, Clarke E, Byrne E. International students’ experience of a western medical school: a mixed methods study exploring the early years in the context of cultural and social adjustment compared to students from the host country. BMC Med Educ. 2015;15(1):111. doi:10.1186/s12909-015-0394-2.

- Jlb E, Sheffler JL. Creating a warm and inclusive classroom environment: planning for all children to feel welcome. Electron J Inclus Educ. 2009;2:4.

- Centers for Disease control and prevention: CDC healthy schools – School Connectedness. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyschools/school_connectedness.htm. Accessed 28 June, 2023.

- Bronfenbrenner U. Contexts of child rearing: problems and prospects. Am Psychol. 1979;34(10):844–850. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.34.10.844.

- Diem S, Welton AD. Anti-Racist Educational Leadership and Policy: Addressing Racism in Public Education. New York: Routledge; 2020.

- Lopez AE, Jean-Marie G. Challenging anti-black racism in everyday teaching, learning, and leading: from theory to practice. J Sch Leader. 2021;31(1–2):50–65. doi:10.1177/1052684621993115.

- Tate WF. Critical race theory and education: history, theory, and implications. Rev Res Educ. 1997;22(1):195–247. doi:10.2307/1167376.

- Solorzano D, Ceja M, Yosso T. Critical race theory, racial microaggressions, and campus racial climate: the experiences of African American college students. J Neg Educ. 2000;69(1/2):60–73.

- FitzGerald C, Hurst S. Implicit bias in healthcare professionals: a systematic review. BMC Med Ethics. 2017;18(1):19. doi:10.1186/s12910-017-0179-8.

- Busari JO. The taste of success: how to live and thrive as black scholars in inequitable and racialized professional contexts. Postgrad Med J. 2023;99(1170):365–366. doi:10.1093/postmj/qgad019.