Abstract

Phenomenon: Navigating uncertainty is a core skill when practicing medicine. Increasingly, the need to better prepare medical students for uncertainty has been recognized. Our current understanding of medical students’ perspectives on uncertainty is primarily based on quantitative studies with limited qualitative research having been performed to date. We need to know from where and how sources of uncertainty can arise so that educators can better support medical students learning to respond to uncertainty. This research’s aim was to describe the sources of uncertainty that medical students identify in their education. Approach: Informed by our previously published framework of clinical uncertainty, we designed and distributed a survey to second, fourth-, and sixth-year medical students at the University of Otago, Aotearoa New Zealand. Between February and May 2019, 716 medical students were invited to identify sources of uncertainty encountered in their education to date. We used reflexive thematic analysis to analyze responses. Findings: Four-hundred-sixty-five participants completed the survey (65% response rate). We identified three major sources of uncertainty: insecurities, role confusion, and navigating learning environments. Insecurities related to students’ doubts about knowledge and capabilities, which were magnified by comparing themselves to peers. Role confusion impacted upon students’ ability to learn, meet the expectations of others, and contribute to patient care. Navigating the educational, social, and cultural features of clinical and non-clinical learning environments resulted in uncertainty as students faced new environments, hierarchies, and identified challenges with speaking up. Insights: This study provides an in-depth understanding of the wide range of sources of medical students’ uncertainties, encompassing how they see themselves, their roles, and their interactions with their learning environments. These results enhance our theoretical understanding of the complexity of uncertainty in medical education. Insights from this research can be applied by educators to better support students develop the skills to respond to a core element of medical practice.

Introduction

Uncertainty is an intrinsic and unavoidable aspect of medicine. Uncertainty can be defined as “the dynamic subjective perception of not knowing what to think, feel, or do.”Citation1 (p2) Uncertainty impacts upon many areas of medical practice, from the care that doctors give their patients to the management of their own wellbeing.Citation2–5 Uncertainty has also been linked to medical students’ academic performance, career choices, wellbeing, and attitudes toward patient populations.Citation2,Citation6–9 Clinicians, educators, and students have called for an increased emphasis on uncertainty in their educational programs.Citation5,Citation10–12 Additionally, a group of medical students have recently called for enhanced support when learning about how to recognize and respond to uncertainty in their undergraduate education.Citation13 To better support medical students to learn about clinical uncertainty, we first need to understand their perspectives, including what sources of uncertainty they identify.

Empirical research contributing to our current understanding of medical students’ perspectives on uncertainty comes predominantly from quantitative questionnaire-based studies.Citation2,Citation6,Citation7,Citation14,Citation15 These studies focus on responses to uncertainty by asking students to complete questionnaires that explore their tolerance to situations of uncertainty.Citation16–20 Student scores are then analyzed in conjunction with other quantitative instruments to provide a better understanding of how uncertainty might shape student experiences. For example, students who are more tolerant of uncertainty may be more likely to work with marginalized patient populationsCitation21–23 and may be more empathetic.Citation22,Citation23 Conversely, students who are less tolerant of uncertainty may experience stress and psychological distress.Citation7,Citation21,Citation24 Though these studies highlight the impact of responses to uncertainty on student wellbeing and behaviors, they do not provide information about possible sources of uncertainty that students may be experiencing. Additionally, reducing the experience of uncertainty to a binary score of tolerance or lack of tolerance of uncertainty may not reflect the nuances of responding to uncertainty in clinical practice, where doctors’ responses to uncertainty can be considered on a spectrum.Citation25 On this spectrum, doctors can possess varying levels of tolerance of uncertainty, which may be influenced by the sources of uncertainty which they encounter.

Qualitative research is one way to expand on quantitative findings and obtain an in-depth understanding of how medical students can experience uncertainty. In the qualitative studies that have been conducted,Citation26–37 the focus has been on ways in which medical students respond to uncertainty rather than sources; for example, by acknowledging and attempting to ameliorate knowledge deficits,Citation26–28 modeling the behavior of doctors,Citation27,Citation28 trying to reduce uncertainty when sharing patient information,Citation29 avoiding uncertainty provoking stimuli, and emotional responses such as fear and frustration.Citation35 Student perspectives on uncertainty have been explored indirectly by investigating their responses to difficult situations,Citation30 analyzing transcripts of case presentations,Citation31 reflective learning diary entries,Citation32,Citation35 analyzing focus groups about exams,Citation37 and as part of course evaluations.Citation33 Through researching responses to uncertainty, these studies have provided information about possible sources of uncertainty for students but by indirect means. These possible sources include students’ own limited knowledge and skillsCitation26,Citation27,Citation30–32,Citation35 and uncertainty around the limits of available knowledge about patients and their management.Citation26–28,Citation31 Other possible sources of uncertainty are social in nature involving skills, roles, and values of professionals in healthcare systemsCitation28,Citation30 and the sociocultural impact of donor dissection in anatomy teaching.Citation35 Students have also described uncertainty arising from their roles as learners and future healthcare professionals.Citation30,Citation32 When medical students apply for postgraduate training, the transition to becoming a healthcare professional can be perceived as a source of professional uncertainty.Citation37 For medical students, professional uncertainty has also been characterized as encompassing professional identity, professional roles, and career plans.Citation36 With the exception of one study,Citation36 the literature is sparse in reporting sources of uncertainty that medical students identify when asked directly.

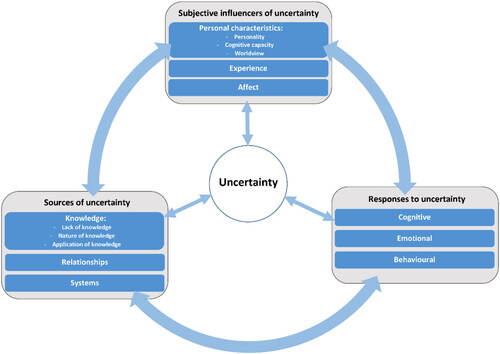

This study seeks to build upon the research performed to date that can provide insights about possible sources of uncertainty experienced by medical students. To better understand uncertainty, including possible sources of uncertainty in medical education, we have previously developed a comprehensive framework of uncertainty based on the synthesis of conceptual models of uncertainty published in health, health professions education, and social sciences literature.Citation1 Within this framework (), sources of uncertainty are dynamically linked to responses to uncertainty and are modulated by a range of subjective influencers such as experience, worldview, and affect.

This framework theorizes that uncertainty arises from three major sources: knowledge, relationships, and systems. Knowledge as a source of uncertainty can occur due to a lack of knowledge, the nature of knowledge (for example, information which is complex, ambiguous, or possesses varying levels of risk), and the application of knowledge in practice. Relationships such as those between student and teacher, doctor and patient, and between healthcare professionals can cause uncertainty. Teaching, learning, and the delivery of patient care takes place in a wide range of settings, often subject to the influences of organizational culture. These complex systems are the third source of uncertainty described in the framework. By including relationships and systems, this framework accounts for the interactions and environments that medical students encounter in their education, and how these may contribute to feelings of uncertainty. The sources of uncertainty described in the framework, however, may be limited by a lack of empirical research on how medical students describe sources of uncertainty in their education. We wished to expand our understanding, and this research aimed to describe the sources of uncertainty that medical students identify when asked directly.

Methods

Context and setting

We undertook this research at the University of Otago, Aotearoa New Zealand where the medical degree is a six-year program. Approximately 70% of students enter the program as undergraduates following competitive selection from a one-year health sciences course (considered as year one of medicine). The remainder, with experience as healthcare workers or university graduates, enter at year two. Years two and three of the program mainly involve lectures and classroom-based learning experiences in Dunedin. Years four, five, and six of the program provide students with clinical learning opportunities in Dunedin, Christchurch, or Wellington. Year six provides internship-based learning opportunities for students in hospitals and the community where they are involved as junior members of clinical teams. This research was approved by the University of Otago Human Ethics Committee, reference D18/365.

Research approach

The limited research available about sources of uncertainty directly identified by medical students influenced our choice of a broad research question and methodology. Seeking a ‘wide-angle lens’Citation38 (p253) understanding of students’ perceptions of uncertainty, and to achieve a broad understanding of a topic where little is known, we chose a qualitative survey approach. We took an interpretive methodological perspective which acknowledges the subjective and co-constructed nature of knowledgeCitation39 to develop rich insights based on our research question. Qualitative surveys are an acceptable and helpful approach for gaining a deeper understanding of the experiences and perceptions of a diverse population.Citation38,Citation40 A survey approach allows the capture of a broad range of views and reduces the burden of participation as our students have full schedules and are frequently contacted to participate in research.

Development of materials

The survey consisted of two free text items. For the first item, we constructed a vignette (see Appendix A) to prime participants to think about uncertainty. Clinical vignettes have been describe as a helpful approach for encouraging reflection.Citation41 The second item asked participants directly to identify sources of uncertainty and was the focus of subsequent analysis. In the vignette, participants were presented with a fictional clinical scenario involving multiple sources of uncertainty from the described framework,Citation1 incorporating knowledge, relationships, and systems as potential sources of uncertainty. The scenario describes a student who is unfamiliar with the patient’s condition and does not have access to their notes (knowledge as a source of uncertainty). The student is alone with the patient who is expressing frustration (relationships as a source of uncertainty). The interaction takes place in a busy general practice setting where a report on the laboratory investigations is not available because the computer is not functioning temporarily (systems as a source of uncertainty). Participants were asked: ‘What parts of the above scenario might make a medical student feel uncertain?’ The vignette was constructed by the authors and refined using feedback from focus groups attended by 17 medical students from second, third, fourth and sixth years of the MB ChB program. To address our research question, a second item asked students directly about sources of uncertainty: ‘What sources of uncertainty have you encountered as a medical student? Please be as specific as possible by giving examples.’

Data collection

To gather students’ perspectives at several points along their educational journey we chose to sample students from second, fourth, and sixth years to allow us to capture a range of experiences in both pre-clinical and clinical education. Between February and May 2019, 716 medical students in Dunedin, Christchurch, and Wellington were invited to participate in this study via an online survey. The first author traveled to each location to speak to students about the study. The survey was distributed at lectures and tutorials and informed consent was obtained prior to participation. Video conferencing software was used on occasions where travel was not possible. Written responses were anonymized at the point of data entry using Qualtrics software Version Feb 2019 (Qualtrics, Provo, UT) and were randomly assigned an alphanumeric code to indicate each participant and their year of study (e.g., P123Y2).

Data analysis

We did not analyze responses to the vignette as it was intended to prime participants, and because asking students to identify sources which we embedded may have resulted in a tautology. To address our research question, we analyzed written responses to the second item using an iterative, reflexive, thematic analysis following the recommended six-step approach.Citation42 Terry and Braun identified thematic analysis as a helpful approach to analyzing qualitative survey data, as it can be a very useful method of identifying and understanding patterns of meaning in large datasets.Citation38 Beginning this process, the first author immersed herself in the data. She read and reread all responses and kept a diary to note ideas, connections, and interesting quotes. She read all responses multiple times to give a ‘feel’ for the data and the story that it told. We used NVivo software version 10 (QSR International Pty Ltd) to perform subsequent coding. We took an inductive approach to coding. Initial coding was “semantic”, defined as a surface level analysis of data meaning.Citation42 Re-reading of the data and codes also generated “latent” coding which aimed to develop a “more implicit or conceptual level of meaning”Citation42 (p11) in participants’ responses. We generated a large number of codes during the coding procedure. With the aim of the study as a guide, we explored and collated codes. We used the definition of a theme as “a central organizing idea that captures a meaningful pattern across the dataset.”Citation42 (p12) We wrote descriptions of each theme and all three authors screened for conceptual overlap. This procedure reduced the number of themes to those reported in this study.

Author reflexivity

Throughout this study, we used the perspectives that each author brought to the research and reflected upon how our experiences influenced our approach and interpretation of the data. The first author (female, Irish) brought experiences of working as a junior doctor in the UK, and as an undergraduate and postgraduate health professional educator in both the UK and New Zealand. The second author (female, New Zealand European and Australian) provided insights from clinical practice involving anesthesiology, intensive care and family medicine, undergraduate and postgraduate teaching, and research experience in medical humanities, clinical decision-making, and ethics. The third author’s (female, first generation New Zealander from Canadian heritage) perspectives included experience with primary, secondary, and tertiary education and research together with a role as a faculty developer of clinical educators. Our perspectives were underpinned by constructivist epistemology, which acknowledges that knowledge and our perceptions of reality are co-constructed by the actions and interactions of individuals and collectives embedded in the cultures and environments which they inhabit.Citation43

Results

The survey was distributed to 716 students. Four-hundred-sixty-five participants responded (n = 190 year two, n = 172 year four, and n = 103 year six), a response rate of 65%. Sixty percent of participants were female and 72% of participants entered the programme as undergraduates. Demographic details are shown in , including comparison with data describing the student population in 2019 (communication from Otago Medical School, Nov 2019).

Table 1. Frequencies and percentages of participant demographics by year level.

Using thematic analysis, we identified three major sources of uncertainty that medical students identify in their education: insecurities, role confusion, and navigating learning environments. These findings encompass sources of uncertainty reported by students as occurring in pre-clinical and clinical environments.

Insecurities: am I good enough?

Participants revealed doubts about themselves which resulted in uncertainty. Insecurities included intrinsic and internal doubts about their knowledge, skills, capabilities, and suitability for a career in medicine. These insecurities could be magnified when participants compared themselves to peers and came up short in their own estimations. Participants described a “feeling of inadequacy amongst my peers” (P392Y6) and doubted their capability “within a cohort of very intelligent people” (P45Y2), who were felt to be “watching your every move” (P2Y2). Uncertainties could also arise from doubts participants held about “belonging in the course” (P205Y4). These results illustrate how participants’ internalized perceptions of the beliefs and assumptions of others could intensify their uncertainty.

These doubts led participants to feel uncertain “if I am right for the profession” (P84Y2). Participants also wondered if they possessed “the right skill set to become a competent doctor” (P314Y4). This could lead to insecurities about their future and what that might look like “if I don’t find something right in medicine for me” (P335Y4). Participants wondered “what it is going to be like practically being a doctor - will I be as good as my grades in the actual profession?” (P87Y2) and were uncertain as to “whether I’d be able to develop in the best doctor I could be” (P182Y2), illustrating concerns spanning their current and future perceptions of themselves.

Participants expressed uncertainty about their ability to acquire and demonstrate the required knowledge and skills, describing “feeling like I am not studying enough or that I don’t know enough even though I spend a lot of time studying” (P342Y4). This quote highlights a common insecurity, the “fear of being inadequate” (P99Y2). Also, participants felt uncertain about their right to be present: “feeling like I’m in the way of more important people” (P262Y4). Insecurities could arise from “not knowing stuff in practically every context, at one stage or another” (P389Y6). Doubts about knowledge and skills were expressed in both university settings (“not knowing answers to questions asked in lectures, tutorials, and labs” (P180Y2)) and in clinical settings (“not knowing how to do things asked of you on ward rounds” (P429Y6)).

Role confusion: what am I supposed to be doing here?

Participants’ understanding about their role as a medical student resulted in uncertainty. Participants described feeling “unsure of my role” (P92Y2) and “not knowing what I’m doing” (P10Y2). Uncertainty could occur as participants came to terms with a new course and new ways of learning, “not knowing what to expect coming to med school” (P105Y2) or when they didn’t know their “role in the medical team on the ward” (P228Y4). Participants felt uncertain about what their role in patient care should be: “uncertain of how involved I can be and how much responsibility to be taken on” (P367Y6). Role confusion meant that participants were uncertain as to whether their contributions, especially with regards to clinical practice, were helpful or a hindrance. Participants wanted to be an asset to their team but were uncertain if they were. These uncertainties were summarized by a participant in sixth year:

What my role is in the team – e.g., how can I be useful? Am I taking up too much space/are there too many people in the ward round, which might be intimidating for the patient, especially considering I’m not that helpful. (P444Y6)

Role confusion was also identified in how students described their engagement with patients. Participants wondered if they should “answer the questions of patients if I know the answer” (P350Y4). Without a clear understanding or vision of their role, participants were uncertain about the appropriateness of even simple acts of kindness: “When a patient was in pain…would it be appropriate for me to ask them to hold my hand so they could squeeze it?” (P373Y6). Participants were uncertain if it was “okay to comfort a patient, and to what degree?” (P321Y4). Thus, role confusion caused uncertainty for participants in how they could contribute to patient care generally, and also in how to care for patients in a holistic and ethical way.

Navigating learning environments: how do I navigate this world?

Participants described how navigating the educational, social, and cultural features of clinical and non-clinical learning environments resulted in uncertainty. Uncertainty arose from attempting to navigate the day-to-day educational practicalities in their learning environments. These practicalities included managing schedules, knowing assessment procedures, fitting into busy team schedules, and knowing what clothing was appropriate to wear. It also involved:

getting used to the way they do things such as the computer systems, where things are stored, certain protocols…I have no issue not knowing a disease or its management…It’s more not knowing the system where I am working or studying which is hard for me. (P396Y6)

Uncertainties arising from navigating the educational, social, and cultural features of learning environments were also identified when participants wondered how to act in situations where they wanted to question how they were being taught or how patients were being treated. Participants were unsure about “speaking up in tutorials when I personally think the tutor has not done something correct[ly]” (P96Y2) or wondered if it was appropriate “to mention something to the consultant like an X-ray finding other people might not have mentioned” (P399P6). A difficult area to navigate involved learning how to act if a participant believed that they had witnessed sub-optimal practice: “The most uncertainty I’ve felt is when I witness poor clinical practice or I believe one of my seniors is not doing a competent job” (P413Y6). This source of uncertainty proved especially challenging when observed hierarchical relationships were considered: “Uncertainty about whether to rise up the hierarchy or stand up for what is right. It sounds easy at the time, but in real life it’s easy to let things slip by for fear of repercussion.” (P339Y4)

Navigating the educational features of learning environments became uncertain when participants felt: “lost when there isn’t a teacher or senior around to show me what to do” (P220Y4) and when they were asked to perform a task for the first time or that was beyond their capability. Participants wanted to know “when and who it is appropriate to ask questions of” (P92Y2). Participants wondered whether they could interrupt busy health care professionals to ask for help because they feared that they might be perceived as a nuisance. Even if advice was given, however, uncertainty could persist “when different senior colleagues give me conflicting advice” (P444Y6).

Discussion

Findings from this study can be used to expand our understanding of sources of uncertainty experienced by students during their medical education. We discuss these findings, and how they relate to and enhance the frameworkCitation1 of uncertainty. We then describe the implications of our study’s findings for teaching and learning about uncertainty.

One insight generated by this study involves how insecurities can be used to explain medical students’ feelings of uncertainty. Whilst doubts about knowledge and skills have been identified as sources of uncertainty for medical students previously,Citation27,Citation28,Citation30–32,Citation35,Citation36 this finding shows that students may doubt themselves and may be concerned about how they compare to others. As a source of uncertainty, insecurity may be explained by the term ‘imposter syndrome’ which occurs “when high achieving individuals chronically question their abilities and fear that others will discover them to be intellectual frauds.”Citation44 (p456) The incidence of imposter syndrome in medical students is known to be high and can have a negative impact on student wellbeing.Citation45 This impact has marked similarities to the consequences of maladaptive responses to clinical uncertainty, including anxiety and burnout.Citation2,Citation3,Citation45 By identifying insecurities as a possible source of uncertainty, we may better understand how students’ experiences of uncertainty may be influenced by how they view themselves as capable medical students and future doctors.

Role confusion was also a source of uncertainty for our medical students. This finding may explain results from previous research where medical students expressed uncertainty when they had difficulty understanding their roles and expectations of their roles, especially with regards to patient care.Citation30,Citation32,Citation36 Role confusion may be related to learning moral or ethical aspects of medical practice. Students may experience uncertainty related to their roles because they are grappling with what it means to be a good medical student. From the responses provided by our students, we understand ‘good’ in this context to mean a healthcare professional who treats patients with kindness and empathy. When a student questions if it is right for them to show empathy to a sick patient or wonders if they can comfort a distressed patient, then they may be trying to reconcile their ability to act with their understanding of how a ‘good’ student or doctor should behave. Students may be trying to make sense of what it means practically, morally, and ethically to be a medical student, and experience uncertainty when they are challenged by this process.

Navigating learning environments was a third major source of uncertainty for medical students. This source of uncertainty contrasts with role confusion as it may lead students to question how to act, even when they feel that they know what they should do. This finding extends our understanding from previous research about the relationship between the behavior of medical students and their uncertainty about how to learn, how to act professionally, and how to maintain their values in their learning environments.Citation30,Citation32,Citation35–37 In our study, we identified aspects of the hidden curriculum in descriptions of the uncertainties faced by participants as they navigated learning environments. The hidden curriculum has been described as the “commonly held ‘understandings’, customs, rituals, and taken-for-granted aspects of what goes on in the life-space we call medical education”Citation46 (p404) which influence the learning and professional development of medical students.Citation47,Citation48 The hidden curriculum has been described in medical students’ relationships with teachers, clinical staff, and patients.Citation47,Citation48 One example of this is the impact of clinical hierarchies, which may result in students feeling that they are not respected or valued due to their status.Citation49 Our students described uncertainties arising from interpersonal relationships, which were magnified in the presence of hierarchies. The hidden curriculum also has a structural component, where norms and culture can influence learning.Citation46,Citation47 Our students felt uncertain when they tried to make sense of the norms and practices of learning in clinical environments, for example when they wondered about appropriate etiquette, or questioned how to speak up and voice concerns. Uncertainty may therefore be one way that the hidden curriculum manifests for medical students. Our results contribute insights into how context can overtly and tacitly shape students’ experiences of uncertainty.

Our findings can be used to explore and enhance the framework of uncertaintyCitation1 described in the introduction (). In this framework, sources of uncertainty include knowledge, relationships, and systems. When describing uncertainties caused by insecurities, role confusion, and navigating learning environments, our students reflected on knowledge (both their own knowledge, and the knowledge available to them), relationships (with peers, teachers, and patients), and the systems in which their learning takes place. This influence of knowledge, relationships, and systems on student experiences of uncertainty suggests that the framework is fit for purpose. The interaction of these sources within an experience, however, indicates that the framework can be refined. Instead of seeing knowledge, relationships, and systems as distinct categorisations, we can be aware that these sources can all dynamically interact with each other. Explicitly highlighting this interaction can help educators to further appreciate the complexity of uncertainty in medical education, especially if we consider that experiences of uncertainty can be shaped by a range of subjective influencers unique to each individual, such as imposter syndrome or an individual’s familiarity with the role they are occupying. The framework of uncertainty can provide a useful starting point for the identification of operant sources of uncertainty, with the understanding that more than one source may be present in any given student experience.

Educators can use the insights from our study’s findings in at least two ways. First, they may choose to focus on one source of uncertainty. Educators may choose to address insecurities as a source of uncertainty by providing supportive interventions, such as facilitated reflective debriefing sessions that encourage students to share experiences, describe feelings, and promote insights in a nonjudgmental environment. Sharing of experiences and feelings has been suggested as one approach to managing imposter syndrome.Citation50 In doing so, students may benefit from realizing that they are not alone in feeling insecure and thereby normalize this possible source of uncertainty. By addressing confusion that may arise during professional role formation, educators may be able to assist medical students learn how to respond to clinical uncertainty and feel confident to act with care and compassion. Educators can help students develop strategies to navigate learning environments by discussing their own uncertainties. By engaging in “intellectual candour,”Citation51 a process of sharing thoughts and vulnerabilities, educators can help to make hierarchies visible and build supportive relationships with their students. Imbuing learning environments with intellectual candor may promote conditions where medical students feel confident to speak up because uncertainty is seen as a normal part of practice.

A second way that educators can use these findings is to embrace the complexity generated among interacting sources of uncertainty. Designing and implementing educational strategies to teach medical students about uncertainty may be more challenging than expected due to the interaction of knowledge, relationships, and systems as sources of uncertainty. We recommend that educators focus on providing learning opportunities that allow students to develop a positive emotional stance or ‘comfort’ with uncertainty. Comfort with uncertainty has been conceptualized as “the phenomenological lived experience of having the confidence to act on a problem (or wait and observe) in the absence of full confidence in one’s understanding of the underlying cause of the issue.”Citation52 (p780) The findings from our study expand our knowledge of uncertainty by providing examples such as insecurities, role confusion, and challenges navigating learning environments as possible causes. Comfort with uncertainty does not require the resolution of uncertainty but a recognition that uncertainty exists, which can then be considered when deciding a course of action. Teaching students to be aware of sources of uncertainty, combined with an understanding of how to choose an appropriate response, may be helpful in preparing medical students for the inevitable uncertainties which they will encounter.Citation52 Comfort with uncertainty can lead to positive responses, such as flexibility, openness, and humility.Citation53 Moving toward ‘comfort with uncertainty’, instead of elimination or even tolerance, may lead to innovative and positive opportunities for learning.

Strengths and limitations

The qualitative approach used in our study provides a deep and rich description of the sources of uncertainty encountered by medical students. The lack of Māori and Pacific background on the research team, given this research occurred in Aotearoa New Zealand, means that some cultural aspects of uncertainty may have been missed. The importance of considering cultural factors may be relevant to researchers in other contexts. Though the sources of uncertainty identified are not exhaustive, a strength of this work is the general alignment with similar sources of uncertainty in medical student populations in the USA,Citation26,Citation27,Citation31,Citation37 Canada,Citation28 Sweden,Citation30 Finland,Citation32 and Australia.Citation35,Citation36 As we build a clearer picture of what sources of uncertainty are meaningful to students, it will be fascinating to see if findings from other countries and cultural contexts align with our own. Confirmation of these possible sources of uncertainty elsewhere is particularly important given that our study was conducted prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, which may have altered or added to the possible sources of uncertainty that students can experience. Another consideration is that research based on free-text survey data has been criticized for lacking robust qualitative analysis.Citation54 Qualitative data collection through surveys, however, is recognized as an innovative and practical approach when the data is analyzed robustly.Citation38,Citation40 We believe that the rigorous approach to reflexive thematic analysis described in our methods to study sources of uncertainty “enrich[es] our understanding of the social phenomena being explored.”Citation54(p348) A further advantage of using a survey for data collection in this study was that it allowed us to obtain data from a large number of students in multiple locations efficiently. The decision to survey students from second, fourth, and sixth year students means that some student experiences of uncertainty may have been missed. It was not possible to invite students from all year groups due to logistical and time constraints. Given that similar sources were identified across different year groups and different levels of clinical experience, we believe that the major sources of uncertainty for this population of medical students were identified. The prompt vignette may have influenced how participants’ described their own experiences of uncertainty through a possible availability bias.Citation55 The vignette focused on a clinical scenario and had specific sources of uncertainty embedded, as detailed in the methods section. The extensive range of student responses when asked directly about uncertainty, however, go well beyond the scenario, and include examples from both clinical and non-clinical learning environments.

Future directions

Future directions for research include further qualitative enquiry to understand student perspectives on the sources of uncertainty described in this study. For example, the uncertainties that students face as they make sense of their roles, and what it means to be a ‘good’ student could inform future research into moral and existential uncertainty, alongside student identity formation. Future research could also explore in more depth the links between the hidden curriculum and uncertainty. Finally, educators and students might benefit from further research into how to foster comfort with uncertainty.

Conclusion

This study provides a rich understanding of sources of uncertainty from the perspective of medical students. We identified insecurity, role confusion, and navigating learning environments as three major sources of uncertainty. Medical students describe uncertainties as they evaluate their capabilities, see themselves as developing professionals, and learn to navigate both the practical and sociocultural aspects of their learning environments. Our findings highlight the complex and dynamic nature of the sources of uncertainty in medical education. These findings can be used by educators to identify possible sources of uncertainty, predict potential challenges, and develop strategies to support medical students to build comfort with uncertainty.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank all participants for their thoughtful contributions. The authors also wish to thank Dr Ralph Pinnock for his insights and advice during the development and analysis stages of this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Lee C, Hall K, Anakin M, Pinnock R. Towards a new understanding of uncertainty in medical education. J Eval Clin Pract. 2021;27(5):1194–1204. doi:10.1111/jep.13503.

- Strout TD, Hillen M, Gutheil C, et al. Tolerance of uncertainty: a systematic review of health and healthcare-related outcomes. Patient Educ Couns. 2018;101(9):1518–1537. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2018.03.030.

- Simpkin AL, Khan A, West DC, et al. Stress from uncertainty and resilience among depressed and burned out residents: a cross-sectional study. Acad Pediatr. 2018;18(6):698–704. doi:10.1016/j.acap.2018.03.002.

- Ghosh AK. Understanding medical uncertainty: a primer for physicians. J Assoc Physicians India. 2004;52:739–742.

- Simpkin AL, Schwartzstein RM. Tolerating uncertainty - the next medical revolution? N Engl J Med. 2016;375(18):1713–1715. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1606402.

- Moffett J, Hammond J, Murphy P, Pawlikowska T. The ubiquity of uncertainty: a scoping review on how undergraduate health professions’ students engage with uncertainty. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2021;26(3):913–958. doi:10.1007/s10459-021-10028-z.

- Hancock J, Mattick K. Tolerance of ambiguity and psychological well-being in medical training: A systematic review. Med Educ. 2020;54(2):125–137. doi:10.1111/medu.14031.

- Groot F, Jonker G, Rinia M, ten Cate O, Hoff RG. Simulation at the frontier of the zone of proximal development: a test in acute care for inexperienced learners. Acad Med. 2020;95(7):1098–1105. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000003265.

- Scott A, Sudlow M, Shaw E, Fisher J. Medical education, simulation and uncertainty. Clin Teach. 2020;17(5):497–502. doi:10.1111/tct.13119.

- Beck JB, Long M, Ryan MS. Into the unknown: helping learners become more comfortable with diagnostic uncertainty. Pediatrics. 2020;146(5):e2020027300. doi:10.1542/peds.2020-027300.

- Papanagnou D, Ankam N, Ebbott D, Ziring D. Towards a medical school curriculum for uncertainty in clinical practice. Med Educ Online. 2021;26(1):1972762. doi:10.1080/10872981.2021.1972762.

- White G, Williams S. The certainty of uncertainty: can we teach a constructive response? Med Educ. 2017;51(12):1200–1202. doi:10.1111/medu.13466.

- Khatri A, Aung YYM, Vijay A, Kazi SUR. Uncertainty in clinical practice: should our focus turn to medical students instead? Med Educ. 2021;55(3):413. doi:10.1111/medu.14375.

- Stephens GC, Karim MN, Sarkar M, Wilson AB, Lazarus MD. Reliability of uncertainty tolerance scales implemented among physicians and medical students: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acad Med. 2022;97(9):1413–1422. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000004641.

- Stephens GC, Lazarus MD, Sarkar M, Karim MN, Wilson AB. Identifying validity evidence for uncertainty tolerance scales: A systematic review. Med Educ. 2023;1–13. doi:10.1111/medu.15014.

- Gerrity MS, DeVellis RF, Earp JA. Physicians’ reactions to uncertainty in patient care. A new measure and new insights. Med Care. 1990;28(8):724–736. doi:10.1097/00005650-199008000-00005.

- Gerrity MS, White KP, DeVellis RF, Dittus RS. Physicians’ reactions to uncertainty: refining the constructs and scales. Motiv Emot. 1995;19(3):175–191. doi:10.1007/BF02250510.

- Geller G, Faden RR, Levine DM. Tolerance for ambiguity among medical students: implications for their selection, training and practice. Soc Sci Med. 1990;31(5):619–624. doi:10.1016/0277-9536(90)90098-d.

- Hancock J, Roberts M, Monrouxe L, Mattick K. Medical student and junior doctors’ tolerance of ambiguity: development of a new scale. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2015;20(1):113–130. doi:10.1007/s10459-014-9510-z.

- Budner SNY. Intolerance of ambiguity as a personality variable. J Pers. 1962;30(1):29–50. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.1962.tb02303.x.

- Caulfield M, Andolsek K, Grbic D, Roskovensky L. Ambiguity tolerance of students matriculating to U.S. medical schools. Acad Med. 2014;89(11):1526–1532. doi:10.1097/acm.0000000000000485.

- Morton KR, Worthley JS, Nitch SR, Lamberton HH, Loo LK, Testerman JK. Integration of cognition and emotion: a postformal operations model of physician-patient interaction. J Adult Dev. 2000;7(3):151–160. doi:10.1023/A:1009542229631.

- van Ryn M, Hardeman RR, Phelan SM, et al. Psychosocial predictors of attitudes toward physician empathy in clinical encounters among 4732 1st year medical students: a report from the changes study. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;96(3):367–375. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2014.06.009.

- Lally J, Cantillon P. Uncertainty and ambiguity and their association with psychological distress in medical students. Acad Psychiatry. 2014;38(3):339–344. doi:10.1007/s40596-014-0100-4.

- Reis-Dennis S, Gerrity MS, Geller G. Tolerance for uncertainty and professional development: a normative analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(8):2408–2413. doi:10.1007/s11606-020-06538-y.

- Blanch DC, Hall JA, Roter DL, Frankel RM. Is it good to express uncertainty to a patient? correlates and consequences for medical students in a standardized patient visit. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;76(3):300–306. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2009.06.002.

- Fox RC. Training for uncertainty. In: Merton RK, Reader GG, eds. The Student-Physician: Introductory Studies in the Sociology of Medical Education. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1957:207–242.

- Lingard L, Garwood K, Schryer CF, Spafford MM. A certain art of uncertainty: case presentation and the development of professional identity. Soc Sci Med. 2003;56(3):603–616. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00057-6.

- Holmes SM, Ponte M. En-case-ing the patient: disciplining uncertainty in medical student patient presentations. Cult Med Psychiatry. 2011;35(2):163–182. doi:10.1007/s11013-011-9213-3.

- Weurlander M, Lönn A, Seeberger A, Hult H, Thornberg R, Wernerson A. Emotional challenges of medical students generate feelings of uncertainty. Med Educ. 2019;53(10):1037–1048. doi:10.1111/medu.13934.

- Wolpaw T, Cote L, Papp KK, Bordage G. Student uncertainties drive teaching during case presentations: more so with SNAPPS. Acad Med. 2012;87(9):1210–1217. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182628fa4.

- Nevalainen MK, Mantyranta T, Pitkala KH. Facing uncertainty as a medical student–a qualitative study of their reflective learning diaries and writings on specific themes during the first clinical year. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;78(2):218–223. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2009.07.011.

- Gowda D, Dubroff R, Willieme A, Swan-Sein A, Capello C. Art as sanctuary: a four-year mixed-methods evaluation of a visual art course addressing uncertainty through reflection. Acad Med. 2018;93(11S Association of American Medical Colleges Learn Serve Lead: Proceedings of the 57th Annual Research in Medical Education Sessions):S8–S13. doi:10.1097/acm.0000000000002379.

- Park S. Embracing uncertainty within medical education. In: Giardino AP, Giardino ER, eds. Medical Education: Global Perspectives, Challenges and Future Directions. New York: Nova Science Publishers Inc; 2013:289–313.

- Stephens GC, Rees CE, Lazarus MD. Exploring the impact of education on preclinical medical students’ tolerance of uncertainty: a qualitative longitudinal study. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2021;26(1):53–77. doi:10.1007/s10459-020-09971-0.

- Stephens GC, Sarkar M, Lazarus MD. ‘A whole lot of uncertainty’: A qualitative study exploring clinical medical students’ experiences of uncertainty stimuli. Med Educ. 2022;56(7):736–746. doi:10.1111/medu.14743.

- Russel SM, Geraghty JR, Renaldy H, Thompson TM, Hirshfield LE. Training for professional uncertainty: socialization of medical students through the residency application process. Acad Med. 2021;96(11S):S144–S150. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000004303.

- Terry G, Braun V. Short but often sweet: the surprising potential of qualitative survey methods. In: Gray D, Clarke V, Braun V, eds. Collecting Qualitative Data: A Practical Guide to Textual, Media and Virtual Techniques. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2017:13–14. doi:10.1017/9781107295094.003.

- Crotty M. Interpretivism: for and against culture. In Foundations of Social Research. London: Routledge; 1998:66–78.

- Braun V, Clarke V, Gray D. Innovations in qualitative methods. In: Gough B, ed. The Palgrave Handbook of Critical Social Psychology. Palgrave. New York: Macmillan; 2017:243–266. doi:10.1057/978-1-137-51018-1_13.

- Tremblay D, Turcotte A, Touati N, et al. Development and use of research vignettes to collect qualitative data from healthcare professionals: a scoping review. BMJ Open. 2022;12(1):e057095. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2021-057095.

- Braun V, Clarke V, Hayfield N, Terry G. Thematic analysis. In: Liamputtong P, ed. Handbook of Research Methods in Health Social Sciences. Singapore: Springer Singapore; 2018:1–18. doi:10.1007/978-981-10-2779-6_103-1.

- Mann K, MacLeod A. Constructivism: learning theories and approaches to research. In Researching Medical Education. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2015:49–66. doi:10.1002/9781118838983.ch6.

- Henning K, Ey S, Shaw D. Perfectionism, the impostor phenomenon and psychological adjustment in medical, dental, nursing and pharmacy students. Med Educ. 1998;32(5):456–464. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2923.1998.00234.x.

- Gottlieb M, Chung A, Battaglioli N, Sebok-Syer SS, Kalantari A. Impostor syndrome among physicians and physicians in training: a scoping review. Med Educ. 2020;54(2):116–124. doi:10.1111/medu.13956.

- Hafferty FW. Beyond curriculum reform: confronting medicine’s hidden curriculum. Acad Med. 1998;73(4):403–407. doi:10.1097/00001888-199804000-00013.

- Lawrence C, Mhlaba T, Stewart KA, Moletsane R, Gaede B, Moshabela M. The hidden curricula of medical education: a scoping review. Acad Med. 2018;93(4):648–656. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000002004.

- Torralba KD, Jose D, Byrne J. Psychological safety, the hidden curriculum, and ambiguity in medicine. Clin Rheumatol. 2020;39(3):667–671. doi:10.1007/s10067-019-04889-4.

- Gaufberg EH, Batalden M, Sands R, Bell SK. The hidden curriculum: what can we learn from third-year medical student narrative reflections? Acad Med. 2010;85(11):1709–1716. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181f57899.

- LaDonna KA, Ginsburg S, Watling C. “Rising to the level of your incompetence”: what physicians’ self-assessment of their performance reveals about the imposter syndrome in medicine. Acad Med. 2018;93(5):763–768. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000002046.

- Molloy E, Bearman M. Embracing the tension between vulnerability and credibility: ‘intellectual candour’ in health professions education. Med Educ. 2019;53(1):32–41. doi:10.1111/medu.13649.

- Ilgen JS, Eva KW, de Bruin A, Cook DA, Regehr G. Comfort with uncertainty: reframing our conceptions of how clinicians navigate complex clinical situations. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2019;24(4):797–809. doi:10.1007/s10459-018-9859-5.

- Han PKJ, Strout TD, Gutheil C, et al. How physicians manage medical uncertainty: a qualitative study and conceptual taxonomy. Med Decis Making. 2021;41(3):275–291. doi:10.1177/0272989X21992340.

- LaDonna KA, Taylor T, Lingard L. Why open-ended survey questions are unlikely to support rigorous qualitative insights. Acad Med. 2018;93(3):347–349. doi:10.1097/acm.0000000000002088.

- Tversky A, Kahneman D. Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases. Science. 1974;185(4157):1124–1131. doi:10.1126/science.185.4157.1124.

Appendix A:

Vignette

Please read the scenario below and answer the following question. There is no right or wrong answer. Simply respond as spontaneously as you can.

Scenario: You are a medical student on placement at a small, busy GP practice. Your GP supervisor is friendly but has a very high workload and their clinics often run over time. You are observing your GP take a history from a new patient when they are called away to take an urgent call from a hospital specialist. The GP asks you to finish taking a history while they are away.

The patient that you are currently reviewing is new to the practice. They have recently emigrated from Ireland where they had previously been treated by the same GP for 30 years. Their medical records have not yet arrived at the practice. They are here to discuss the management of their condition, X-itis (which you have never heard of). The patient had blood tests last week and is eager to see the results. They are frustrated about the lack of knowledge in New Zealand about their condition and seem annoyed that they are being seen by a medical student.

The laboratory online system is down, and you cannot access their results. You check with the practice nurse, but the results have not arrived yet. As you wait for your GP supervisor to return, your patient asks you why their X-itis is not improving.

What parts of the above scenario might make a medical student feel uncertain?