Abstract

Problem

Enhancing workforce diversity by increasing the recruitment of students who have been historically excluded/underrepresented in medicine (UIM) is critical to addressing healthcare inequities. However, these efforts are inadequate when undertaken without also supporting students’ success. The transition to clerkships is an important and often difficult to navigate inflection point in medical training where attention to the specific needs of UIM students is critical.

Intervention

We describe the design, delivery, and three-year evaluation outcomes of a strengths-based program for UIM second year medical students. The program emphasizes three content areas: clinical presentations/clinical reasoning, community building, and surfacing the hidden curriculum. Students are taught and mentored by faculty, residents, and senior students from UIM backgrounds, creating a supportive space for learning.

Context

The program is offered to all UIM medical students; the centerpiece of the program is an intensive four-day curriculum just before the start of students’ second year. Program evaluation with participant focus groups utilized an anti-deficit approach by looking to students as experts in their own learning. During focus groups mid-way through clerkships, students reflected on the program and identified which elements were most helpful to their clerkship transition as well as areas for programmatic improvement.

Impact

Students valued key clinical skills learning prior to clerkships, anticipatory guidance on the professional landscape, solidarity and learning with other UIM students and faculty, and the creation of a community of peers. Students noted increased confidence, self-efficacy and comfort when starting clerkships.

Lessons Learned

There is power in learning in a community connected by shared identities and grounded in the strengths of UIM learners, particularly when discussing aspects of the hidden curriculum in clerkships and sharing specific challenges and strategies for success relevant to UIM learners. We learned that while students found unique benefits to preparing for clerkships in a community of UIM students, near peers, and faculty, future programs could be enhanced by pairing this formal intensive curriculum with more longitudinal opportunities for community building, mentoring, and career guidance.

Introduction

Workforce diversity is critical to efforts to address healthcare inequities as it brings needed expertise and perspectives about the healthcare system into healthcare practice, leadership, and policy. Many U.S. medical schools have responded to calls for the diversification of the physician workforce by improving recruitment of students who have been historically excluded/underrepresented in medicine (UIM).Citation1 While increasing recruitment of students from UIM backgrounds into medical school is a necessary first step to improving physician diversity, it is inadequate when undertaken without considering how best to support UIM student success.Citation2

Medical students from UIM backgrounds related to race and socioeconomic status have been shown to often lack identification with the medical context, experience low self-esteem, and encounter discrimination and stereotype threat, impacting their professional identity formation and engagement with the medical community during training.Citation3,Citation4 UIM residents frequently experience microaggressions and bias that can be ‘othering,’ require extra cognitive and emotional work to withstand, and affect professional identity formation.Citation5–7 Further, witnessing inequitable care of patients with shared identities has a significant impact on UIM trainees.Citation6 At the same time, UIM students and residents demonstrate numerous strengths including connection and empathy with patients marginalized by the healthcare system and a desire to give back to those patients and to public healthcare systems.Citation4,Citation7 Learning environments that afford “identity safety” (“the ability to exist as [your] authentic self without feeling the need to monitor how others perceive [your] identities”Citation8 (p1) may counteract some of the challenges experienced by UIM learners while enabling them to fully express their many strengths, and may contribute positively to professional identity formation.Citation8

Marking a pivotal transition, clerkships are key to securing competitive post-graduate training opportunities, a springboard to future careers and academic and leadership positions.Citation9 Moreover, differential distribution of honors grades in clerkships disproportionally impacts UIM students.Citation10,Citation11 All students may experience stress and concerns about lack of preparedness,Citation12 as well as factors that negatively affect their clinical learning, performance, and professional identity formation such as variable faculty teaching skills and competing team demands. However, as described above, UIM students experience disproportionate burdens during clerkships.Citation13–16 Even in institutions where clerkship honors grading has been eliminated due to equity concerns, supporting UIM students to excel early in clerkships remains important for residency applications (e.g., for narrative evaluative comments used in residency applications), and for nurturing the self-efficacy, clerkship learning, motivation, and professional identity formation needed to effectively engage in clerkships and to contemplate academic and leadership career paths.Citation17 While transitional clerkships that aim to prepare all students for the clerkship environment have been well described,Citation18–26 there is no literature on how best to support UIM students in this transition.

Many interventions designed to support the success of UIM students throughout medical school implicitly or explicitly employ a deficit model by focusing on differential academic attainment of UIM vs. non-UIM students (e.g., by focusing on traditional medical knowledge assessment scores).Citation27,Citation28 In fact, UIM students, who often have had to successfully navigate barriers throughout their education from structural racism to economic and educational inequities, bring expertise and resilience to their medical education that should be acknowledged and underscored to support ongoing success. We built a program that prepares students for the transition to clerkships by using a strength-based approach that emphasizes the many skills that UIM learners bring to the clinical setting.Citation29–31

In this paper, we describe our program’s design principles and structure, as well as our evaluation, also grounded in a strengths-based approach, including reflections from our participants on which parts of the program were critical to supporting their success. Anti-deficit frameworks encourage strengths-based approaches, directing us to emphasize and “explore how UIM learners persist and successfully navigate their education.”Citation32 (pS121) By incorporating students’ insights into which elements were most helpful, we drew on anti-deficit framing and embraced the expertise of students as a core element of our programmatic design and continuous quality improvement. Our program description and outcomes have implications for schools invested in creating supportive structures to facilitate the success and achievement of UIM learners.

The academic leadership academy summer program

We designed the Academic Leadership Academy Summer Program (ALAS) (“wings” in Spanish) using a strengths-based approach to prepare students for clerkships in a supportive environment of peers and faculty mentors with shared racial/ethnic backgrounds.Citation33 ALAS explicitly emphasizes students’ life experiences as valuable assets conferring important skills for clinical medicine (e.g., experiences helping family members navigate the healthcare system). Students are empowered to be experts in their own learning during program evaluation sessions where student feedback serves as the impetus for programmatic improvement. ALAS emphasizes gradual mastery of key clerkship skills in a learning environment of UIM peers rooted in the growth mindset,Citation34 facilitated by UIM faculty mentors who serve as visible role models with shared identities to learners—directly countering feelings of ‘othering’ (i.e., feelings linked with being treated differently, often in ways that reinforce oppressive social hierarchies) in the academic medicine environment that can impact UIM learners’ professional identity formation.

ALAS uses a strengths-based approach by explicitly framing and highlighting racial/ethnic minority identities in positive ways and elevating the assets emanating from students’ backgrounds and identities:

UIM medical educators and professionals lead the course, serve as mentors in small groups and panels, providing role models and making UIM success in academic medicine visible.

Community and connection among participating UIM students are fostered by encouraging participants to share what drew them to careers in medicine and emphasizing the many successes that led them to medical school, often despite structural barriers.

UIM near peers (e.g., senior medical students, residents, chief residents, and fellows) share how their identities allow them to contribute uniquely and meaningfully to clinical practice, and how they thrive in environments that can be exclusionary.

Skill-building in clinical decision-making and presentations occurs with individualized feedback that explicitly includes reinforcing feedback and the growth mindset in a supportive setting.

Program context, goals, and structure

ALAS was developed at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), School of Medicine, a public, research-intensive institution that graduates approximately 165 medical students annually. Students begin clerkships in January of their second year after approximately 18 months of pre-clerkship learning. UCSF utilizes a pass/fail assessment system for core clerkships. An ALAS pilot was funded by the UCSF Academy of Medical Educators; the UCSF Latinx Center of Excellence provided faculty support in subsequent years. Our institution has committed to enhancing diversity, equity, inclusion, and anti-racism/anti-oppression (DEIA). At the time of ALAS’ launch, a “Differences Matter” initiative focused on advancing DEIA principles school-wide was underway.Citation35

All rising second year UIM medical students are invited to join ALAS. UIM is defined by the AAMC as “racial and ethnic populations that are underrepresented in the medical profession relative to their numbers in the general population.”Citation1 Nationally in the U.S., this includes learners from African American/Black, Latino/a/x/e, Native American/Indigenous/Alaskan Native, and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander backgrounds. In California, UIM also includes under-represented groups such as learners with Filipino and Cambodian backgrounds. A few students with backgrounds as refugees who were not on our school’s UIM list inquired about joining ALAS and were also welcomed into the program.

ALAS goals were based on a needs assessment that included topics that arose frequently in one-on-one mentoring conversations, observation, and teaching with UIM students by ALAS leadership. With the over-arching aim of bringing a strengths-based lens to all activities as described above, ALAS aimed to support the transition to and clerkship year of UIM students by focusing on three goals which align with the three key domains (educational, social, and developmental) described in a scoping review about supporting the clerkship transition:Citation36

Develop clinical skills through practice in small group settings (educational and developmental)

Establish support networks between UIM students, near peers, and faculty (social)

Create a supportive learning environment of UIM peers and mentors to encourage student growth and empowerment and to discuss professional challenges and the hidden curriculumCitation37 (social and developmental)

Program structure

ALAS’ centerpiece is an intensive four-day curriculum held just before the start of students’ second year that focuses on three core content areas related to our program goals: clinical presentations/clinical reasoning, community building, and the hidden curriculum. Learning is reinforced in periodic activities over the following year. shows a sample schedule for the ALAS summer program.

Table 1. ALAS Summer Program sample schedule and activities.

Following the summer component, ALAS has a half-day program just before starting clerkships, and a check-in mid-way through clerkships to re-connect with peers, ALAS alumni, and faculty. During the residency application process, another check-in session provides an opportunity for re-connection and mentorship. Students are encouraged to reach out to ALAS faculty with questions and to celebrate accomplishments. ALAS’ design was informed by literature on student experiences during the transition to clerkships and the clerkship year itself and based on program goals as follows:

Program goal 1: develop clinical skills through practice in small group settings

During clerkships, faculty use student oral presentations to gauge clinical reasoning and knowledge, yet students often learn to present primarily by trial and error.Citation38 Given the centrality of presentations to clerkship success and to effective patient care, presentation skill building is a core element of ALAS. Didactics reviewing clinical reasoning and presentation logic are paired with small groups to practice preparing and delivering oral presentations and communicating clinical reasoning. To align with our strengths-based approach, learners are asked to reflect on their areas of strength as well as opportunities for growth, and facilitators and peers ensure that both reinforcing and constructive feedback are discussed. Clinical presentations and reasoning are explicitly linked to effective clinical care and patient advocacy, while the performative aspects of presenting are acknowledged, critiqued and de-prioritized. De-prioritizing clerkship ‘performance’ and focusing instead on authentic contributions to patient care aligns with a shift from a performance goal orientation, “characterized by the desire to appear competent, avoid appearing incompetent, or avoid mistakes”Citation17 (p315) toward a mastery goal orientation that emphasizes “gaining skills or knowledge”Citation17 (p315) as well as patient care and advocacy.Citation17 This shift can encourage deeper, more enjoyable learning, perseverance and identity development grounded in clinical excellence.Citation17,Citation39,Citation40

Program goal 2: establish support networks between UIM students, near peers, and faculty

Social support among peers is critical for success during clerkships.Citation41,Citation42 Peers share helpful resources to manage clinical transitions, clarify clerkship student roles, support one another when dealing with interpersonal issues, and reduce feelings of isolation.Citation43 For students with heightened surface visibility due to their identities and the associated risk for toxic exposures related to microaggressions and experiences of stereotype threat in the clinical setting, peer support and community connections are particularly important.Citation44,Citation45 Additionally, learning from near peer UIM students, residents, and fellows who have successfully navigated clerkships and other clinical experiences enables us to highlight the many strengths that UIM individuals bring to these settings. ALAS establishes for each cohort a network of UIM peers and mentors that students can draw upon during clerkships, and curates multiple opportunities to build community with fellow students, residents, and faculty from UIM backgrounds through panel conversations and small group activities. ALAS mentors are clinical fellows and faculty who identify as UIM. They facilitate small groups, provide lectures, participate in panels, and engage in social activities with students. In addition to roles as clinical teachers on the wards or in clinic, many mentors have educational leadership roles within the medical school or GME programs. During the program, ALAS students also take on the role of near-peer mentors to pre-medical students in a local pipeline program, affording students an opportunity to reflect on what drew them to medicine and how they have already demonstrated success.

Program goal 3: create a supportive learning environment of UIM peers and mentors to encourage student growth and empowerment and to discuss the hidden curriculum

During clerkships, students engage with a ‘hidden curriculum’ that exists outside of the formal curriculum.Citation37 The hidden curriculum conveys implicit messages about clinical careCitation46 and the requirements for success as a student. While some of these messages are positive and productive, others are unclear to students, and still others communicate harmful aspects of clinical culture such as bias, stereotypes, and stigma against patients. ALAS aims to create a supportive environment to empower students to discuss the hidden curriculum openly and to share insights on how to thrive in clerkships. Students unpack the hidden curriculum with residents, senior students, and faculty from UIM backgrounds and explore how holding a UIM identity comes with both strengths and unique challenges. Topics addressed include implicit rules of what is expected of clerkship students, what makes a ‘star student,’ how learning opportunities and approaches shift during clerkships (e.g., when to ask questions on rounds, when self-directed learning is expected), how to manage microaggressions from patients, colleagues, and supervisors, how to mitigate stereotype threat, and how to advocate for patients and bring one’s authentic self to the clinical environment.

Program evaluation

Evaluation design and model

We aimed to design a program to develop clinical skills, establish support networks and create a supportive learning environment of UIM students. The focus of our evaluation design was to explore how students experienced ALAS’ ability to facilitate these program goals and to characterize which and how programmatic features contributed to those goals. We drew on two evaluation frameworks, with our primary focus on what made ALAS useful to students. We used the Context, Input, Process, and Product evaluation model, focusing on two of the model’s steps: describing how students characterized the outcomes of ALAS (product) and how programmatic components contributed to those outcomes (process).Citation47 We also drew on theory-based evaluation to describe and characterize an initial program theory (i.e., a theory that describes how and why a program is intended to work, or how the processes and outcomes of the program are related) for how the ALAS program’s design, with its strengths-based underpinning, including its components and processes, contributed to ALAS outcomes.Citation48 This program theory aims to help similar programs in similar contexts utilize our results and further refine our approach. The School of Medicine Institutional Review Board reviewed the evaluation protocol and found it exempt from IRB requirements (survey component: study #: 19-27704, reference #: 247452, focus group component: study #: 22-36018, reference #: 336001).

Instruments and procedures

We collected program evaluation data through surveys that included closed and open-ended questions over three iterations of the program between 2019 and 2021. We selected surveys because we wanted numeric data that indicated how students perceived the program and its components, and included open-ended questions to prompt students to explain/elaborate on their numeric ratings. Students completed surveys at the end of the summer program to ensure that they could provide not only general impressions, but also specific, session-level feedback at a time when they had not forgotten granular details. In 2020 and 2021, we added focus groups while students were in the middle of clerkships for students to reflect on their overall ALAS experience once immersed in clerkships. Focus groups enabled students to describe the value of what they learned in ALAS for clerkships and to speak to program processes and outcomes in depth. Questions asked about students’ overall experience in ALAS, key lessons, specific strategies used during ALAS that helped them develop skills for clerkships, comfort seeking guidance from ALAS leadership, impact of ALAS on confidence to start the clerkship year, and value offered by the ALAS community. Focus groups allowed us to learn about individual and group experiences simultaneously, including whether and how students agreed about and spoke to program processes and outcomes. Since ALAS included a strong network and community building component, the in-group dynamics of the focus groups facilitated students sharing accumulated experiences with the program. Instruments are included in Appendix A. All participating students were invited to complete the surveys and join focus groups. Survey completion rate from 2019-2021 was 74% (39/53). Thirteen students participated in focus groups (six in 2020 and seven in 2021); each focus group lasted approximately 50 min and was audio-recorded and transcribed.

Analysis

Two investigators (SC, AT) analyzed open-ended survey and focus group results using thematic analysis.Citation49 The two investigators familiarized themselves with the data by reading all responses to the survey items and focus group transcripts at the end of each year. They then read two transcripts independently to identify concepts and potential codes. One investigator (SC) drafted an initial codebook, which the second investigator reviewed and refined. They used this draft codebook to independently code all remaining transcripts and open-ended survey data, with two coders per transcript/data. They reconciled discrepancies through discussion. Finally, they integrated themes from focus groups with open-ended survey questions to determine which program components informed program outcomes. Below, we describe program outcomes and components perceived by students as contributing to success.

Researcher reflexivity

The ALAS study team consisted of five women: three physicians/clinician educators, one research analyst, and one education scientist. One evaluator identifies as Biracial (African American and white), two as Latina, one as white, and one as Iranian American. Four of the evaluators were involved in the design of the instruments (DC, SAN, AF, AT). Investigators involved in data collection and analysis (SC, AT) were not involved with the development and design of ALAS. The backgrounds of the study team impacted the approach to the development of ALAS (i.e., the training experiences of the physicians on the team, which included experiences of feeling ‘othered,’ informed the grounding in the need for belonging and visible role-models with shared backgrounds), as well as the impetus for the study, analysis, and interpretation. Team members are advocates for structural changes in medical education to support the thriving of UIM learners and to advance health equity. These values informed the pursuit of the current study, aligned it with an aim to demonstrate the value of bringing an equity lens to student support for the clerkship transition, and likely impacted the teams’ analysis and interpretation of the data.

Evaluation results

Thirteen students participated in a one-day pilot ALAS program in 2018 (28% of second year UIM students) (this brief pilot was not formally evaluated in the same way as the full program, so evaluation data below do not include the pilot year), 20 in 2019 (32% of second year UIM students), 16 in 2020 (30% of second year UIM students), and 17 in 2021 (24% of second year UIM students), for a total of 66 students over the program’s first four years. Of the total 66 ALAS students, 56% identified as Hispanic/Latinx, 21% as Black/African American, 14% as Asian/Pacific Islander, 9% as Native American, and 27% as Mixed/Other (note: total is over 100% since students could select more than one racial/ethnic identity). Half of the students identified as women, half as men; no students identified as nonbinary or transgender. Students rated all aspects of the program very highly with a mean score of 4.9/5 for “overall value” of the program (Appendix B).

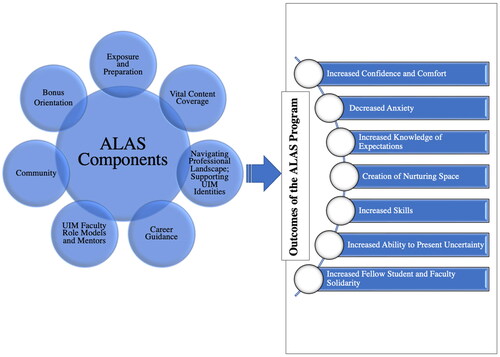

illustrates themes from open-ended survey items and focus groups related to program outcomes and the key components of ALAS that contributed to those outcomes. The figure represents an initial framework or program theory describing the relationship between ALAS’ design, processes, and outcomes. We describe these themes below with representative quotes in the text and in .

Figure 1. An initial framework based on evaluation themes from student focus groups and surveys conducted between 2019-2021 describing the relationship between the ALAS program’s design, processes, and outcomes on core components and outcomes of the ALAS program for Underrepresented in Medicine medical students at the University of California, San Francisco school of Medicine.

Table 2. Themes and representative quotes from open-ended survey items and focus groups describing the outcomes and contributing program components of the ALAS program for students Underrepresented in Medicine at the University of California San Francisco School of Medicine, 2019 through 2021 (see in-line text for additional quotes).

ALAS program outcomes: themes

Students characterized the program outcomes as follows (italicized words indicate alignment with outcomes described in ):

Exposure to ALAS content before starting clerkships boosted student confidence and decreased anxiety, which students linked to ALAS being a place to practice and learn.

Being given a sense of what to expect in clerkships and having a safe space to practice clinical skills boosted confidence and helped students feel more prepared for their first clerkship.

Participants appreciated how ALAS gently pushed them into uncomfortable situations (e.g., presenting progress notes) while supporting them to build skills and develop ways to positively present their uncertainty and knowledge gaps to mentors.

Consequently, during clerkships, students were comfortable speaking up, participating, and asking for feedback. Students also gained confidence through a sense of solidarity of being in the program with students and faculty with shared identities.

Components that contributed to program success

Below, we describe key components that contributed to student perceptions of ALAS’ successful outcomes. Additionally, we describe student recommendations for how to enhance these components in the future. Quotes and summaries are followed with participants’ unique identifiers in parentheses.

Early clerkship orientation, exposure, and preparation

Students found that interactive activities on oral presentations, gathering histories, note writing, clinical reasoning, and observing rounds provided a useful early orientation before starting clerkships. Students noted that ALAS offered a sense of what to expect in clerkships, such as learning about their roles in patient care. Students reported that ALAS also exposed them to challenges they might encounter during clerkships and gave them insight into the hidden curriculum, which can be “really stressful…uncovering the hidden curriculum…I’m really grateful that ALAS gave us a kickstart on that and exposed us to that first as best they could” (P2-2021).

Students reported that ALAS provided a safe space to practice clinical skills needed for clerkships. Receiving feedback from expert clinical educators helped students feel comfortable learning without worrying about making mistakes and failing. Students appreciated the program’s focus on skills such as integrating data from primary literature into presentations and note writing with an emphasis on the assessment and plan. Some students referenced their ALAS program notes as a guide during rotations. Most students were new to these learning experiences and “found it extremely useful…for how to approach the clinical year…practicing clinical presentations, gathering a history, building a differential, actually going into the hospital and observing rounds…all useful to get a little bit of exposure before the clinical year” (P2-2020). Students noted that they would have felt intimidated trying out these skills for the first time during clerkships without practice because, for example, “as first gen [first generation to college/medical school], it often feels like…we’re trying to catch up or be on par with everyone else” (P4-2020). Students shared that ALAS was great preparation for those “who could potentially be behind…and [gave] them a little bit of a push to be a little bit ahead of their other classmates” (P2-2020) when starting clerkships and, therefore, afforded them an advantage to balance the disadvantages that they had experienced as UIM students.

Suggested improvements included desires for a greater focus on the assessment and plan component of clinical presentations. Students also noted that the presentation framework they learned during ALAS would be most helpful if it incorporated presentation styles from multiple specialties with perhaps a “mock rounds…so we have a better sense of it…to have a clear idea of the environment” (P16-2021). As one student explained, ALAS increased confidence presenting in settings that utilized the presentation style they learned in the program (e.g., internal medicine), but this confidence was not always transferrable to other specialties (e.g., surgery).

Navigating the professional landscape; supporting UIM identities

Students found it helpful that ALAS addressed expectations around behavior in clerkships, how to interact with attendings, residents, and patients, and how to bring their own identities into clerkships. Students appreciated panels of UIM peers who “talk[ed] about difficult experiences” and shared “new perspective[s] and some strategies that I could use once I’m on the wards” (P4-2021), and helped “boost…confidence” by emphasizing “that we were learners…So…when you’re constantly getting thrown into a new situation…and feeling like you don’t know what you’re doing, it was really helpful to remember it’s ok, I am a learner and…I can navigate this situation…and still get through this” (P3-2020). One student explained that they lacked confidence in bringing their identity into the clinical realm for fear that, as a UIM student, they would need to behave a certain way to avoid negative feedback. Students shared that ALAS helped them appreciate the important positive role of their identities in contributing to patient care. Students also highlighted the value of being in a group with others with shared backgrounds and “the sense of solidarity…I felt really grateful to be with students of similar background…it made me feel more comfortable with speaking out or even participating” (P4-2020).

Students found that ALAS discussions around the microaggressions they might encounter in clerkships were richer than prior discussions in medical school. Students appreciated opportunities to hear from senior UIM students who discussed their own experiences and strategies for dealing with difficult situations.

Career guidance

Students appreciated opportunities to get career advice during ALAS and noted that this advice, which came before similar issues were addressed in medical school, reduced their stress and prepared them for next steps. Several students recommended that future iterations of the program include guidance on residency applications, for help with “how to go about making those relationships to get letters of recommendation…and how to build up your CV for residency” (P12-2021).

UIM faculty role models and mentors

Students discussed the importance of being exposed to UIM faculty in positions of power who served as role models. One student explained that not only was it powerful to have well-known UIM faculty overseeing ALAS, but also it provided opportunities to practice communicating and navigating professional and personal relationships with faculty. Students identified that connections with UIM mentors was important for fitting into clinical spaces and navigating personal identity. As an area for improvement, students expressed that they would appreciate having an ongoing mentorship structure with “assigned mentors…who we schedule meetings with on either a bimonthly or monthly basis. Because…oftentimes people feel really afraid to reach out…they don’t want to bother them…especially the powerhouse people that were leading ALAS” (P4-2020). They also recommended expanding the number of UIM leaders who participate in ALAS to provide more faculty for students to connect with and to reflect the support of the institution for UIM students’ learning.

Community

Students perceived the community aspect of ALAS as highly significant to their learning and essential to the program’s success. This community consisted of peers as well as faculty and staff who ran ALAS and faculty and trainees who taught in the program. Students varied in the extent to which they formed a community with ALAS peers during clerkships. However, students from both focus groups felt that their peer community was an essential part of the program as it “was incredibly supportive and engaged, which facilitated my learning over the course of the program” (Survey 2020). Students welcomed being part of a community that they connected and shared experiences with, which helped them prepare mentally for clerkships and increased their confidence. Notably, the 2020 cohort, whose clerkships were significantly affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, reported the most variation in their sense of a peer community, and would have liked more opportunities to connect for follow-up discussions.

Discussion

We present our three-year experience with an innovative, strengths-based program designed to support UIM medical students to excel in the transition to clerkships, a critical moment in medical training. The program emphasizes practicing clinical presentations, communicating clinical reasoning, addressing the hidden curriculum, anticipating professional challenges, and creating community in a supportive environment of UIM peers and mentors. The strengths-based lens of ALAS led to an emphasis on the skills that students bring to the clinical environment as a result of, rather than in spite of, their backgrounds and identities. ALAS activities are not remediation activities, but rather learning experiences in which students have opportunities to support one another, and engage and build community with successful peers and mentors with similar backgrounds as their role models. The framework in is offered to guide other institutions when piloting similar programs for applicability, refinement, and strengthening.

Students defined successful ALAS program outcomes as contributing to their clinical skills learning by providing them with confidence and self-efficacy, creating bonds of solidarity, and establishing a nourishing space to practice clinical skills before entering clerkships. Students noted that ALAS contributed to these successful outcomes by serving as a bonus orientation prior to clerkships, providing exposure to and preparation for key clinical skills and challenges, supporting learners with UIM role models and mentors, creating a community of peers that offered resources prior to and during clerkships, and guiding them on how to navigate the professional landscape.

An equity approach to education should include tailored opportunities to support all learners to thrive based on their particular learning needs. Pipeline programs have been successful in supporting the recruitment/enrollment of UIM students into the health professions using a variety of culturally sensitive approaches (e.g., near peer mentorship with UIM medical students, fostering professional identity formation through community building, mentorship, and research opportunities).Citation50–53 Some programs bring equity-based approaches for longitudinal support, mentorship, and career development to UIM medical students.Citation54–56 However, the same is not true for programs focused on the transition to clerkships, which have used uniform approaches for all students.Citation22,Citation26,Citation57–59 While these types of transition programs are important foundational experiences that establish baseline learning for all students, linked offerings with an equity focus are needed. Culturally responsive education brings an equity lens to educational efforts and moves us away from “one [privileged] size fits all” Citation60 (p459) approaches.Citation60

Anti-deficit framing asks us to focus on the strengths of UIM learners rather than concentrating on perceived deficiencies. By centering our learners’ strengths, we created opportunities to recognize and reinforce the richness of skills, expertise, and patient-centered values that students from UIM backgrounds bring to the clinical environment. Due in part to the comfort fostered by being in community with peers and faculty with shared UIM backgrounds, students were able to express their concerns about how they would be perceived in the clerkships based on their identities. In addition to having these concerns acknowledged and explored, discussions with UIM peers and mentors also highlighted and elevated the expertise that students would bring precisely because of their identities. As such, ALAS was an important step toward making it clear to students that their expertise and identities were welcomed and needed in academic medicine. Principles used in ALAS may be helpful to consider when undertaking efforts to support UIM learners to thrive in other areas such as research.

Focus groups enabled us to learn from participants how to deepen the impact of programs like ALAS. Providing insight into the presentation and note style of all core clerkships (beyond internal medicine) would be a useful addition to our content. Longitudinal structured faculty and peer support, with continuation of the ALAS learning community during clerkships, was another area for growth noted by participants. Structured mentorship during clerkships, and the development of structures that sustain peer-peer mentorship and support during clerkships were also important ways to enhance our impact. Students worried about burdening busy faculty with questions, so barriers to reaching out during clerkships need to be lowered to explicitly encourage connection. Providing more guidance on residency applications and career planning was another area for growth identified by students.

There were limitations of our program design and evaluation. Our institution enrolls approximately 35-45% UIM students annually; not all UIM students opted to participate in ALAS. We do not have data to describe why some UIM students chose to participate in ALAS while others did not; investigation into barriers and facilitators to participation could be helpful. We had variable participation in our end-of-program surveys (ranging from 60-93.8%), and only a subset of ALAS students joined focus groups, which may impact the representativeness of our findings for the ALAS cohorts as a whole. Additionally, as described above, our institution was invested in school-wide DEIA initiatives—transferability of our program to schools without institutional efforts to advance equity may be impacted. Finally, students were recruited to ALAS based primarily on our state’s UIM definition, which focuses on race/ethnicity. Students with other identities linked with discrimination and inequity in medicine (e.g., LGBTQ + identities) may benefit from similar programs. Future work is needed to explore how our programmatic principles may apply or need adaptation for learners with other intersectional, historically excluded identities.

Conclusion

Medical schools must build upon the important work of increasing UIM student numbers by developing programs that support students to thrive and set them on paths to future academic and leadership roles. ALAS can serve as one model for supporting UIM students during the critical transition from pre-clerkship learning to the immersive clinical environment. We encourage educators looking to develop similar programs to utilize a strengths-based approach and to create opportunities for students to learn and practice with peers and faculty from shared backgrounds.

Author disclaimers

The views expressed herein are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Department of Defense, Veterans Affairs, or other federal agencies.

Ethical approval

The Institutional Review Board at the University of California, San Francisco reviewed the study and approved it as not human subjects research (the survey component (Study #: 19-27704, Reference #: 247452) and analysis of the focus group component (Study #: 22-36018, Reference #: 336001) were reviewed separately).

Previous presentations

Data from the pilot of ALAS was presented at the University of California, San Francisco’s annual Education Showcase in 2019.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the current and former staff of the University of California, San Francisco Latinx Center of Excellence (LCOE), in particular Julia Farfan, Carla Fernandez, and Connie Calderon-Jensen. In addition, the authors thank the many dedicated faculty members, residents, and fellows who taught and mentored students in the ALAS program.

Disclosure statement

The authors have no competing interests to report.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Underrepresented in Medicine Definition. AAMC. 2023. https://www.aamc.org/what-we-do/equity-diversity-inclusion/underrepresented-in-medicine. Accessed August 21, 2023.

- Nguemeni Tiako MJ, Ray V, South EC. Medical schools as racialized organizations: how race-neutral structures sustain racial inequality in medical education-a Narrative review. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(9):2259–2266. doi:10.1007/s11606-022-07500-w.

- Acker R, Healy MG, Vanderkruik R, Petrusa E, McKinley S, Phitayakorn R. Finding my people: effects of student identity and vulnerability to Stereotype Threat on sense of belonging in surgery. Am J Surg. 2022;224(1 Pt B):384–390. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2022.01.025.

- Machado MB, Ribeiro DL, de Carvalho Filho MA. Social justice in medical education: inclusion is not enough-it’s just the first step. Perspect Med Educ. 2022;11(4):187–195. doi:10.1007/s40037-022-00715-x.

- Osseo-Asare A, Balasuriya L, Huot SJ, et al. Minority resident physicians’ views on the role of race/ethnicity in their training experiences in the workplace. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(5):e182723. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.2723.

- Sotto-Santiago S, Mac J, Slaven J, Maldonado M. A Survey of internal medicine residents: their learning environments, bias and discrimination experiences, and their support structures. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2021;12:697–703. doi:10.2147/AMEP.S311543.

- Rezaiefar P, Abou-Hamde Y, Naz F, Alborhamy YS, LaDonna KA. “Walking on eggshells”: experiences of underrepresented women in medical training. Perspect Med Educ. 2022;11(6):325–332. doi:10.1007/s40037-022-00729-5.

- Bullock JL, Sukhera J, Del Pino-Jones A, et al. “Yourself in all your forms”: a grounded theory exploration of identity safety in medical students. Med Educ. 2023. doi:10.1111/medu.15174.

- Katzung KG, Ankel F, Clark M, et al. What do program directors look for in an applicant? J Emerg Med. 2019;56(5):e95–e101. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2019.01.010.

- Teherani A, Hauer KE, Fernandez A, King TE, Lucey C. How small differences in assessed clinical performance amplify to large differences in grades and awards: a cascade with serious consequences for students underrepresented in medicine. Acad Med. 2018;93(9):1286–1292. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000002323.

- Colson ER, Pérez M, Blaylock L, et al. Washington university school of medicine in St. Louis case study: a process for understanding and addressing bias in clerkship grading. Acad Med. 2020;95:S131–S135. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000003702.

- Malau-Aduli BS, Roche P, Adu M, Jones K, Alele F, Drovandi A. Perceptions and processes influencing the transition of medical students from pre-clinical to clinical training. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):279. doi:10.1186/s12909-020-02186-2.

- Wheeler M, de Bourmont S, Paul-Emile K, et al. Physician and trainee experiences with patient bias. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(12):1678–1685. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.4122.

- Glaser J, Pfeffinger A, Quan J, Fernandez A. Medical students’ perceptions of and responses to health care disparities during clinical clerkships. Acad Med. 2019;94(8):1190–1196. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000002582.

- Hill KA, Samuels EA, Gross CP, et al. Assessment of the prevalence of medical student mistreatment by sex, race/ethnicity, and sexual orientation. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(5):653–665. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0030.

- Ackerman-Barger K, Boatright D, Gonzalez-Colaso R, Orozco R, Latimore D. Seeking inclusion excellence: understanding racial microaggressions as experienced by underrepresented medical and nursing students. Acad Med. 2020;95(5):758–763. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000003077.

- Seligman L, Abdullahi A, Teherani A, Hauer KE. From grading to assessment for learning: a qualitative study of student perceptions surrounding elimination of core clerkship grades and enhanced formative feedback. Teach Learn Med. 2021;33(3):314–325. doi:10.1080/10401334.2020.1847654.

- van Gessel E, Nendaz MR, Vermeulen B, Junod A, Vu NV. Development of clinical reasoning from the basic sciences to the clerkships: a longitudinal assessment of medical students’ needs and self-perception after a transitional learning unit. Med Educ. 2003;37(11):966–974. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2923.2003.01672.x.

- Chumley H, Olney C, Usatine R, Dobbie A. A short transitional course can help medical students prepare for clinical learning. Fam Med. 2005;37(7):496–501.

- Poncelet A, O’Brien B. Preparing medical students for clerkships: a descriptive analysis of transition courses. Acad Med. 2008;83(5):444–451. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e31816be675.

- van Hell EA, Kuks JBM, Schönrock-Adema J, van Lohuizen MT, Cohen-Schotanus J. Transition to clinical training: influence of pre-clinical knowledge and skills, and consequences for clinical performance. Med Educ. 2008;42(8):830–837. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03106.x.

- Chittenden EH, Henry D, Saxena V, Loeser H, O’Sullivan PS. Transitional clerkship: an experiential course based on workplace learning theory. Acad Med. 2009;84(7):872–876. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181a815e9.

- O’Brien BC, Poncelet AN. Transition to clerkship courses: preparing students to enter the workplace. Acad Med. 2010;85(12):1862–1869. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181fa2353.

- Sakai DH, Fong SFT, Shimamoto RT, Omori JSM, Tam LM. Medical school hotline: transition to clerkship week at the John A. Burns School of Medicine. Hawaii J Med Public Health J Asia Pac Med Public Health. 2012;71(3):81–83.

- Taylor JS, George PF, MacNamara MMC. A new clinical skills clerkship for medical students. Fam Med. 2014;46(6):433–439.

- Connor DM, Conlon PJ, O’Brien BC, Chou CL. Improving clerkship preparedness: a hospital medicine elective for pre-clerkship students. Med Educ Online. 2017;22(1):1307082. doi:10.1080/10872981.2017.1307082.

- Reteguiz J, Davidow AL, Miller M, Johanson WG. Clerkship timing and disparity in performance of racial-ethnic minorities in the medicine clerkship. J Natl Med Assoc. 2002;94(9):779–788.

- Shields PH. A survey and analysis of student academic support programs in medical schools focus: underrepresented minority students. J Natl Med Assoc. 1994;86(5):373–377.

- Harper SR. An anti-deficit achievement framework for research on students of color in STEM. New Drctns for Instit Rsrch. 2010;2010(148):63–74. doi:10.1002/ir.362.

- O’Connor C. 2019 wallace foundation distinguished lecture education research and the disruption of racialized distortions: establishing a wide angle view. Educ Res. 2020;49(7):470–481. doi:10.3102/0013189X20931236.

- Kolluri S, Tichavakunda AA. The counter-deficit lens in educational research: interrogating conceptions of structural oppression. Rev Educ Res. 2023;93(5):641–678. doi:10.3102/00346543221125225.

- Teherani A, Perez S, Muller-Juge V, Lupton K, Hauer KE. A narrative study of equity in clinical assessment through the antideficit lens. Acad Med. 2020;95:S121–S130. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000003690.

- Lewis V, Martina CA, McDermott MP, et al. Mentoring interventions for underrepresented scholars in biomedical and behavioral sciences: effects on quality of mentoring interactions and discussions. CBE Life Sci Educ. 2017;16(3):ar44. doi:10.1187/cbe.16-07-0215.

- Dweck CS, Yeager DS. Mindsets: a view from two eras. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2019;14(3):481–496. doi:10.1177/1745691618804166.

- Diaz T, Navarro JR, Chen EH. An institutional approach to fostering inclusion and addressing racial bias: implications for diversity in academic medicine. Teach Learn Med. 2020;32(1):110–116. doi:10.1080/10401334.2019.1670665.

- Atherley A, Dolmans D, Hu W, Hegazi I, Alexander S, Teunissen PW. Beyond the struggles: a scoping review on the transition to undergraduate clinical training. Med Educ. 2019;53(6):559–570. doi:10.1111/medu.13883.

- Hafferty FW, Franks R. The hidden curriculum, ethics teaching, and the structure of medical education. Acad Med. 1994;69(11):861–871. doi:10.1097/00001888-199411000-00001.

- Haber RJ, Lingard LA. Learning oral presentation skills. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(5):308–314. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.00233.x.

- Cerasoli CP, Ford MT. Intrinsic motivation, performance, and the mediating role of mastery goal orientation: a test of self-determination theory. J Psychol. 2014;148(3):267–286. doi:10.1080/00223980.2013.783778.

- Chen HC, ten Cate O, O’Sullivan P, et al. Students’ goal orientations, perceptions of early clinical experiences and learning outcomes. Med Educ. 2016;50(2):203–213. doi:10.1111/medu.12885.

- Chou CL, Johnston CB, Singh B, et al. A “safe space” for learning and reflection: one school’s design for continuity with a peer group across clinical clerkships. Acad Med. 2011;86(12):1560–1565. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e31823595fd.

- Tai J, Penman M, Chou C, Teherani A. Learning with and from peers in clinical education. In: Nestel D, Reedy G, McKenna L, Gough S, eds. Clinical Education for the Health Professions: Theory and Practice. Springer Singapore; 2020. p. 1–19. doi:10.1007/978-981-13-6106-7_90-1.

- Chou CL, Teherani A, Masters DE, Vener M, Wamsley M, Poncelet A. Workplace learning through peer groups in medical school clerkships. Med Educ Online. 2014;19(1):25809. doi:10.3402/meo.v19.25809.

- Bullock JL, Lockspeiser T, Del Pino-Jones A, Richards R, Teherani A, Hauer KE. They Don’t See a Lot of People My Color: A Mixed Methods Study of Racial/Ethnic Stereotype Threat Among Medical Students on Core Clerkships. Acad Med. 2020;95:S58–S66. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000003628.

- Bullock JL, O’Brien MT, Minhas PK, Fernandez A, Lupton KL, Hauer KE. No one size fits all: a qualitative study of clerkship medical students’ perceptions of ideal supervisor responses to microaggressions. Acad Med. 2021;96(11S):S71–S80. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000004288.

- Haidet P, Kelly PA, Chou C, Communication C, Group CS; Communication, Cirriculum, and Culture Study Group. Characterizing the patient-centeredness of hidden curricula in medical schools: development and validation of a new measure. Acad Med. 2005;80(1):44–50. doi:10.1097/00001888-200501000-00012.

- Stufflebeam DL, Coryn CLS. Evaluation Theory, Models, and Applications. Somerset: John Wiley & Sons; 2014.

- Weiss CH. Theory-Based Evaluation: Past, Present, and Future. New Dir Eval. 1997;76:41–55.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Stewart KA, Brown SL, Wrensford G, Hurley MM. Creating a comprehensive approach to exposing underrepresented pre-health professions students to clinical medicine and health research. J Natl Med Assoc. 2020;112(1):36–43. doi:10.1016/j.jnma.2019.12.003.

- Stephenson-Hunter C, Strelnick AH, Rodriguez N, Stumpf LA, Spano H, Gonzalez CM. Dreams realized: A long-term program evaluation of three summer diversity pipeline programs. Health Equity. 2021;5(1):512–520. doi:10.1089/heq.2020.0126.

- Stephenson-Hunter C, Franco S, Martinez A, Strelnick AH. Virtual summer undergraduate mentorship program for students underrepresented in medicine yields significant increases in self-efficacy measurements during COVID-19 pandemic: a mixed methods evaluation. Health Equity. 2021;5(1):697–706. doi:10.1089/heq.2021.0060.

- Rinderknecht FAB, Kouyate A, Teklu S, Hahn M. Antiracism in action: development and outcomes of a mentorship program for premedical students who are underrepresented or historically excluded in medicine. Prev Chronic Dis. 2023;20:E49. doi:10.5888/pcd20.220362.

- Youmans QR, Adrissi JA, Akhetuamhen A, et al. The STRIVE initiative: a resident-led mentorship framework for underrepresented minority medical students. J Grad Med Educ. 2020;12(1):74–79. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-19-00461.2.

- Santos-Parker JR, Santos-Parker KS, Caceres J, et al. Building an equitable surgical training pipeline: leadership exposure for the advancement of gender and underrepresented minority equity in surgery (LEAGUES). J Surg Educ. 2021;78(5):1413–1418. doi:10.1016/j.jsurg.2021.01.017.

- Henry TL, Freeman CD, Sheth A, et al. Making an impact with E.M.P.A.C.T. engage, mentor prepare, advocate, cultivate, and teach: an innovative pilot mentoring program evaluation for students underrepresented in medicine. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2023;14:803–813. doi:10.2147/AMEP.S400547.

- Butts CA, Speer JJ, Brady JJ, et al. Introduction to clerkship: bridging the gap between preclinical and clinical medical education. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2019;119(9):578–587. doi:10.7556/jaoa.2019.101.

- Beavers L, Christofilos V, Duclos C, et al. Perceptions of preparedness: how hospital-based orientation can enhance the transition from academic to clinical learning. Can Med Educ J. 2020;11(4):e62–e69. doi:10.36834/cmej.61649.

- Ryan MS, Feldman M, Bodamer C, Browning J, Brock E, Grossman C. Closing the gap between preclinical and clinical training: impact of a transition-to-clerkship course on medical students’ clerkship performance. Acad Med. 2020;95(2):221–225. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000002934.

- Maduakolam E, Madden B, Kelley T, Cianciolo AT. Beyond diversity: envisioning inclusion in medical education research and practice. Teach Learn Med. 2020;32(5):459–465. doi:10.1080/10401334.2020.1836462.