ABSTRACT

The U.S. Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act (Tobacco Control Act) of 2009 paved the way for the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to propose nine different graphic warning labels (GWLs) intended for prominent placement on the front and back of cigarette packs and on cigarette advertisements. Those GWLs were adjudicated as unconstitutional on the ground that they unnecessarily infringed tobacco companies’ free speech without sufficiently advancing the government’s public health interests. This study examines whether less extensive alternatives to the original full-color GWLs, including black-and-white GWLs and text-only options, have similar or divergent effects on visual attention, negative affect, and health risk beliefs. We used a mobile media research lab to conduct a randomized experiment with two populations residing in socioeconomically disadvantaged communities: biochemically confirmed adult smokers (N = 313) and middle school youth (N = 340). Results indicate that full-color GWLs capture attention for longer than black-and-white GWLs among both youth and adult smokers. Among adults, packages with GWLs (in either color or black-and-white) engendered more negative affect than those with text-only labels, while text-only produced greater negative affect than the packages with brand imagery only. Among youth, GWLs and text-only labels produced comparable levels of negative affect, albeit more so than brand imagery. We thus offer mixed findings related to the claim that a less extensive alternative could satisfy the government’s compelling public health interest to reduce cigarette smoking rates.

The 2009 U.S. Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act (Tobacco Control Act) sought to inform Americans of the health risks of smoking, prevent uptake of cigarette smoking in youth, and lower smoking rates among adults. The Act paved the way for the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to propose nine different GWLs intended for prominent placement on the front and back of cigarette packs and on cigarette advertisements. Major tobacco companies (TCs) took to court several concerns about the proposed graphic warning labels, arguing that the labels were both too extensive and ineffective in raising awareness of health risks associated with smoking. After a federal appeals court ruled in favor of these TCs, the FDA decided against pursuing further review in the Supreme Court, opting instead to revisit the content of the labels. To date, the FDA has not yet proposed new warnings.

Using eye-tracking technology and self-reported reactions to cigarette packs with varied warning labels, this study examines the TCs claim that a less extensive regulation, such as a warning with black-and-white (B&W) image or featuring only text, could satisfy the government’s public health interest of reducing smok-ing rates. We focus on two populations from disadvantaged socioeconomic settings: biochemically confirmed adult smokers and middle school youth. Smoking rates are higher among those living below the poverty level (26%) compared to those at or above it (14%; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Citation2016). In addition, 3,200 people try their first cigarette each day, and 9 of 10 people who become regular smokers try their first cigarette by age 18 (US Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS), Citation2012). These populations share disproportionate burdens of tobacco use and are underrepresented in tobacco research.

Legal precedent and competing arguments

The U.S. Congress delegated regulatory authority over tobacco products to the FDA when it enacted the Tobacco Control Act in Citation2009 (H.R. 1256). The Tobacco Control Act specified that the FDA “shall issue regulations that require color graphics depicting the negative health consequences of smoking” (H.R. 1256, Division A, Title 2, Sec. 201(d)), specifying that the warnings would be in full color and cover the top 50% of both sides of cigarette boxes.

In 2011, the FDA released a set of nine warnings, following the presentation of draft warnings and a period of public comment. Major TCs immediately objected to the new warnings, arguing the warnings extensively infringed on their right to market a legal product, specifically taking issue with the presence of a full-color image on the warning (in R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company et al. vs. United States Food and Drug Administration, Citation2011). Drawing on the Central Hudson test (Central Hudson Gas & Electric Corp. vs. Public Service Commission, Citation1980), TCs argued that any warning requirement should be no more extensive than necessary to achieve the government’s interest, implying that the proposed warnings were too extensive.

In 2012, the TCs won the case in the trial and appeals courts, and the U.S. government decided to reassess the labels rather than seek further legal review in the Supreme Court. The FDA remains under pressure to release new labels. In October 2016, the American Academy of Pediatrics and seven other medical and public health groups filed suit against the FDA, claiming that the number of smokers in the United States could have been reduced by millions in the time the FDA has taken to review the labels (Jenco, Citation2016). This underscores the need for communication researchers, policy analysts, and legal scholars to provide additional insights about the content and effectiveness of various warning label options that might satisfy the compelling government interest test while maintaining free speech protections. That test requires the government to show that a challenged regulation is the least restrictive means of achieving a compelling interest.

The U.S. government and TCs can be expected to differ both on what constitutes a compelling government interest and the least restrictive means of advancing that interest. The FDA argues that text-only warnings do not attract and hold attention at the same level as warnings with images and that warnings with imagery serve to inform potential smokers of the risks associated with smoking as well as support intentions of smokers who may want to quit (75 Fed.Reg. 69,524, Citation2010). The argument implicitly contends that even if people understand the health risks of smoking cigarettes, they may need reminders to make those risks salient.

TCs focus their arguments on whether the labels increase knowledge by informing people of smoking’s health risks. They claim the government lacks a compelling interest in informing people of health risks associated with smoking, because people already know that smoking is harmful. Therefore, new warning labels will fail to change knowledge of smoking risks (R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company et al., vs. United States Food and Drug Administration, Citation2011, Document 18, p. 23). TCs further argue that people already overestimate the risks associated with smoking (Schneider, Gadinger, & Fischer, Citation2012) and that graphic warning labels are a government-imposed “emotionally charged anti-smoking message” (R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company et al. vs. United States Food and Drug Administration, Citation2011, doc 18, p. 14).

Communication theory and smoking behaviors

The message impact framework (Noar et al., 2016b) provides a lens for understanding the factors contributing to warning label effects. Our study examines whether variations in the use of color and graphic imagery influence key predictors of smoking behavior, including (1) visual attention, (2) negative emotional reactions, (3) health risk beliefs, and (4) quit intentions (among adult smokers) or smoking susceptibility (among youth). We focus particular attention on the role of negative emotional reactions in this process.

The idea that GWLs are nothing more than a government-imposed “emotionally charged message” runs against much of what has been discovered in the fields of communication, marketing, and psychology. Decades of research has tested the effectiveness of arguments and peripheral cues in shaping the persuasiveness of strategic messages (O’Keefe, Citation2002) as well as the important role of emotion in information processing (Slovic, Finucane, Peters, & MacGregor, Citation2004). Side by side with factual text claims, many of the format elements at issue (e.g., size, color, and placement) function as cues to encourage attention to messages and feature emotional appeals (e.g., fear, guilt) to aid in deeper processing and motivation (Evans et al., Citation2015; Peters, Lipkus, & Diefenbach, Citation2006). To this end, some legal scholars agree that emotion and reason are connected processes and that therefore emotionally evocative messages are not inherently problematic for the U.S. government to compel, as long as the messages are not misleading or erroneous (Corbin, Citation2014; Tushnet, Citation2014). TCs also rely on cues and emotional appeals in their own marketing and packaging, understandably so because human beings rely on cues in the environment to sift through a bombardment of stimuli to determine what is appealing, status-enhancing, important, useful, or threatening (Slovic et al., Citation2004). Once a stimulus is attended to, emotion is a key component of information processing, memory, and decision making.

Evidence of cigarette package warning label effectiveness

Scientific consensus is building that improved warnings on the U.S. cigarette packs will likely function as intended. In two systematic reviews of dozens of studies, the authors concluded that strengthened warnings (i.e., improved text, implemented graphic warnings, or enhanced graphic warnings relative to weaker versions) increased several key variables that are the foundations of future behavioral change: attention to the warnings, recall of their key messages, negative affect, perceived effectiveness, knowledge about smoking, increased quit attempts, and decreased smoking prevalence (Noar et al., Citation2016a, Citation2016b). Brewer et al. (Citation2016) recently reported results from a randomized clinical trial in which researchers added, each week, either (a) a pictorial warning label to the top half of the cigarette pack, or (b) the existing Surgeon General’s warning label to the side of each cigarette pack. Smokers exposed to pictorial warnings had a 6% increase in quit attempts over those exposed to the text-only warning (40% vs. 34%). Pictorial warnings appeared to work by increasing warning-related thoughts, thoughts about smoking harms, and negative emotions.

Combined, the meta-analyses and controlled field trial make a compelling argument that graphic warning labels can increase quit-related knowledge, emotions, intentions, and behavior among adult smokers. It is yet unclear, however, whether less restrictive versions of these labels may have comparable effects, whether these effects transfer to youth, or whether smokers from socioeconomically disadvantaged communities respond differently to such warnings.

Graphic warnings and socioeconomic status

As noted above, rates of cigarette smoking in the United States vary by socioeconomic status. Although smoking rates have declined in the past several decades (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Citation2016), the rate of decline has not been evenly distributed. Only 7% of Americans with a college degree smoked in 2015, versus 24% of those without a high school diploma and 34% of those with a graduate equivalency diploma (GED) (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Citation2016).

Previous research suggests that graphic, novel, and emotional cues in warning messages about cigarette smoking may be particularly important for those with less education and at lower income levels, because they grab attention, are more memorable, are easier to process, stimulate more discussion, and are harder to ignore than textual arguments (Durkin, Brennan, & Wakefield, Citation2012; Ramanadan, Nagler, McLoud, Kohler, & Viswanath, Citation2017; Thrasher et al., Citation2012). Studies have yet to test, with a socioeconomically disadvantaged population, whether warnings with full-color images are more effective than black and white images and, similarly, whether an equally prominent text-only warning could promote similar levels of visual attention and negative affect as a warning with an image.

Graphic warnings and youth

Although cigarette smoking is declining among adolescents, an estimated 1 in 20 youth between the ages of 12–17 have smoked a cigarette in the last 30 days. Nearly half of adult smokers became regular, daily smokers before age 18 (USDHHS, Citation2012). Despite being a primary target of tobacco control efforts, youth have been featured far less frequently than adults in GWL research. Indeed, a review of observational studies found only 12% focused solely on youth or adolescents (Noar et al., Citation2016b). Still, the available evidence suggests that GWLs may be effective at reducing positive smoking beliefs and susceptibility to smoking among youth.

Early studies found that the existing Surgeon General’s warning did not convey specific health concerns to youth, who were unable to accurately recall textual warnings in general (Fischer, Krugman, Fletcher, Fox, & Rojas, Citation1993). More recent studies show that the depth of processing for text-only labels is low (Moodie, MacKintosh, & Hammond, Citation2010). Cues such as graphic images can attract attention and evoke emotional reactions in youth who are otherwise unable or unmotivated to process health messages (Keys, Morant, & Stroman, Citation2009). Teens spend more time looking at pictorial warnings than text-only warnings (Peterson, Thomsen, Lindsay, & John, Citation2010), and gaze duration predicts recall for pictorial warnings but not text-only warnings. Youth perceive pictorial warnings on cigarette packs as more effective than text-only warnings (Vardavas, Connolly, Karamanolis, & Kafatos, Citation2009), particularly when they contain graphic disease depictions (Hammond et al., Citation2012).

Several studies have looked at reactions to the proposed FDA warnings. One found that youth perceive full-color (FC) versions of these warnings as more effective than those in B&W (Hammond, Reid, Driezen, & Boudreau, Citation2013). Another study concluded that the proposed FDA warnings elicit strong negative emotions and cognition among both youth and adult smokers (Nonnemaker, Choiniere, Farrelly, Kamyab, & Davis, Citation2015). A third, brain imaging study found evidence that viewing the proposed warnings lowered smoking cravings among adolescent smokers (Do & Galván, Citation2014). None of these studies, however, have systematically compared the effects of graphic FC, graphic B&W, text-only labels of similar size conveying the exact same verbal content or the long-standing Surgeon General’s Warnings (SGWs) on visual attention, negative affect, and health risk beliefs, or whether these effects manifest themselves among youth from socioeconomically disadvantaged communities, one of the primary goals of the current paper.

Methods

Because the U.S. government may not compel more speech than necessary to achieve its interests—here, the interest in public health—our studies compare how exposure to less extensive alternatives to the full-color graphic warnings proposed by the FDA influences specific outcomes proposed in the message impact framework. With these considerations, we offer two randomized experiments with two different, socioeconomically disadvantaged populations named as key considerations in the Tobacco Control Act: adult smokers and middle-school youth. We manipulate features of the messages that TC’s argued compelled speech beyond the point of public health benefits, particularly the use of a full-color image in addition to new text, holding the size (50% of the package) and placement of the warning (the top half) constant to avoid confounding the impact of warning label content features with size). The Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the authors’ institution approved all study protocols and procedures.

Recruitment procedures and study participants

Adults

Adult participants (N = 313) resided in both rural and urban areas of the Northeastern United States. We identified low SES communities by a combination of analysis of median annual household income census data with attention to areas under $35K, contact with site-specific organizations that served low-SES communities, discussions with local representatives, and in-person site scouting. We visited each site only once, unless it was a large urban area, in which case up to three different parts of a given city served as data collection sites.

We first secured permits and necessary security in each community and, when possible, formed partnerships that met University IRB protocols. On data collection dates for adults, we arrived in city and town centers or at a host organization’s location with a fully functional mobile laboratory (the size of a small RV) equipped with five private experimental workstations. We placed signage around the lab, indicating that adults who were regular smokers could participate in the study for $20 cash. If we had a host, that host would let their clientele know about our presence via Facebook, fliers, and word of mouth. Data collection most often occurred between 9am and 6pm. After obtaining informed consent, we confirmed participants as regular smokers through one of two biochemical validation procedures: (a) a CoVita carbon monoxide detection breath test requiring at least 7 ppm (a result indicating regular smoking) or, in a handful of people with self-proclaimed breathing problems, (b) an Alere saliva test indicating a positive rating for the presence of cotinine (a nicotine metabolite). We only allowed qualifying participants to continue.

The adult sample identified as 64% male, 10% Hispanic, and 38% as non-White (n = 83 Black; n = 38 one or more non-White, non-Black categories). A majority (73%) had a total yearly household income of <$20,000/year, 67% reported their highest level of formal education being a high school diploma or less, 71% reported having utilized government food voucher services, and 59% reported being food insecure.

Youth

Youth participants (N = 340) were middle school students living in both rural and urban communities in the northeastern United States. We first identified communities via census data and contacts with partner organizations. We then reviewed publicly available data on the percentage of students who qualified for the federal free or reduced lunch program for low-income families. We completed district-level approval and permissions processes as required, and then approached qualifying schools (those with between 40% and 100% of students receiving free or reduced-price lunch) for permission to conduct the study with 6th to 8th grade students during school hours. Participating schools sent parents IRB-approved, opt-out consent forms in the weeks before we conducted the study, and each participant signed an assent form immediately before taking the study. Middle school students were not required to be smokers to participate.

Half (50%) of the youth respondents who provided information about gender identified as female, 44% as male, 3% “preferred not to answer,” and another 3% did not respond. Participants had a median age of 12.6 (SD = 1.0; range 11–14). The majority (63%) identified as non-Hispanic White, 21% Black or African American, 12% Hispanic or Latino, 3% Native American, 2% Asian, and 13% another race or ethnicity. More than half (53%) reported living with a smoker, and 8% had tried at least a puff of a cigarette.

Study procedures

We assigned all participants a unique identifying number that contained details on their random assignment to one of five experimental conditions. We then escorted the participant into a private study station housed in the mobile laboratory and seated them for the study. Each station featured TobiiStudio eyetracking software and Tobii LCD monitors to unobtrusively collect data on the screen location of participants’ eye gaze, as well as an iPad with the Qualtrics-based post-test questionnaire. Before viewing the stimuli for their randomized condition, each participant completed a nine-point, eye-tracking calibration process. Research assistants read the study instructions to participants, while those instructions were also visible on the screen. Participants completed all calibration tasks and viewed the images assigned to their condition while seated approximately two feet from the computer monitor.

Immediately after viewing the stimuli according to their assigned condition, we handed respondents an iPad to answer a series of closed-ended questions gauging emotional and cognitive reactions on a Qualtrics survey application. The average participant completed the study in 25 min, not including wait time. We paid each adult participant $20 cash upon study completion. For youth, we offered two incentive options to accommodate district policies and requests: $10 gift cards for students or a $10 per-student payment to the school to support student initiatives. The study took, on average, 15–20 min to complete, and students rarely had to wait to begin the study. We debriefed all participants about the rationale for the study.

Design and stimuli

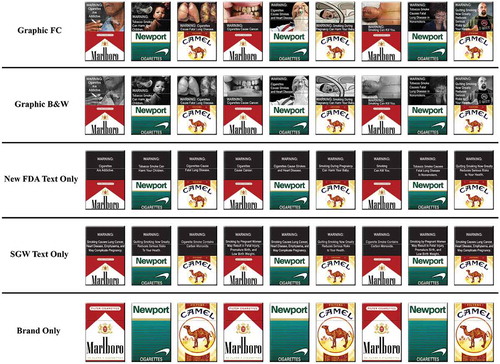

As noted above, we randomly assigned participants to one of five conditions in which all participants viewed images of cigarette boxes depicting (1) FDA graphic full-color warnings (graphic FC), (2) FDA graphic black-and-white warnings (graphic B&W), (3) new FDA text-only warnings, (4) SGW text-only, or (5) brand-only control (see ). Each participant viewed a set of nine images of cigarette boxes, randomly ordered, consistent with their condition. The images appeared one at a time, automatically advancing after 10 s each, for 90 s of total screen time. An “X” appeared on the screen in one of nine possible locations in between images to reset the participant’s gaze. The images depicted the front of cigarette boxes for the three most popular brands (Marlboro, Camel, and Newport) and for all conditions (except the brand-only control) featured a warning label placed prominently on the top 50% of the pack. Each brand appeared three times in the rotation of nine warnings; we rotated brands across warnings to prevent order effects and so that no one warning was consistently associated with any one brand. The graphic FC and graphic B&W conditions featured verbatim text and images from the FDA’s nine warning labels proposed in 2011 with two exceptions. First, we modified the font on some labels to enable us to keep the font size and type consistent across conditions. Second, we omitted the 1-800-QUIT-NOW quit line number that was a part of the original FDA labels but was a source of controversy in litigation (R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company et al. vs United States Food and Drug Administration, Citation2011). The new FDA text-only condition featured the same text from the graphic conditions but with the image removed and the text centered on a black background for aesthetic appeal. The SGW text-only condition rotated verbatim text (also on a black background) from the four warnings that are currently mandated on all cigarette boxes in the United States.

Dependent variables: eye tracking measures

Visual attention: gaze duration

We captured visual attention to specific areas of interest (AOIs) on the cigarette packs with eye-tracking technology. We used the Tobii T60XL 24” monitor (1920 × 1200 native resolution) with built in eye-trackers connected to computers with TobiiStudio 3.4.4 eye tracking software installed. We seated participants such that cigarette pack images were at a viewing distance of approximately 64 cm, decisions meant to replicate the angle and distance of holding a pack at arms-length. We instructed participants to keep their eyes on the screen for all images. We focused our analysis on the duration of fixation in three different AOIs (measured in seconds summed across all nine images): (a) brand logo (on the bottom 50% of the pack for noncontrol participants; the entire image for brand-only control participants), (b) warning (the top 50% of the pack for noncontrol), and (c) graphic pictorial images (for the conditions featuring images, graphic FC and graphic B&W).

Dependent variables: self-reported measures

After viewing the stimuli, participants completed a post-test questionnaire assessing self-reported affective and cognitive responses to the images. We randomized all measures within blocks and all blocks within the questionnaire except for emotional reactions, which we assessed first, and demographics, which we assessed last. We adapted all youth items from previous measures (described below) for potential low-literacy youth (targeting a 4th grade reading level).

Negative affect

We gauged emotional reactions immediately after viewing the stimuli using a set of eight items adapted from the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) (Watson & Clark, Citation1999). Participants responded to the prompt, “After looking at the pictures of cigarette packs, I felt…” [afraid, angry, annoyed, sad, disturbed, grossed-out, scared, and guilty] (randomly ordered). Response choices ran from 1 = not at all to 5 = extremely. Emotion items were highly correlated (average adult r = .69, average youth r = .51) and a single-factor, confirmatory factor model had acceptable fit (adults, CFI = 0.99, SMRR = 0.03; youth, Confirmatory Fit Index (CFI) = 0.96, Standardized root mean squared residual (SRMR) = 0.04), allowing us to treat negative affect as a unitary construct. We therefore averaged the items into a single scale (adults: α = .91, M = 2.12, SD = 1.00; youth: α = .84, M = 2.23, SD = .91).

Old risk beliefs, adults

We assessed health risk beliefs associated with both the old SGWs and the new FDA-proposed warnings using measures adapted from the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) survey (Hyland et al., Citation2016). We measured four items deemed “old risk beliefs” because their content (explicit or implied) has been a part of SGW content for decades. We worded these items as follows: “Based on what you know or believe, does smoking cigarettes cause… [babies to be born with low birth weight from the mother smoking during pregnancy, heart disease in smokers, lung cancer in smokers, and lung disease, such as emphysema, in smokers]? We offered participants the response choices of Yes, No, and Not sure. We calculated an old risk belief index by first dichotomizing responses indicating Yes = 1 versus any other response = 0, and then totaling the number of “yes” responses across the four items (range 0–4, M = 3.61, SD = 0.91).

Old risk beliefs, youth

We measured four items among youth (adapted from PATH, Hyland et al., Citation2016), asking, “Do you believe cigarette smoking is related to… [cancer, lung disease, and heart disease, and problems in babies whose moms smoke]? Response choices ranged from 1 = definitely not to 4 = definitely yes. We calculated the old risk belief index by dichotomizing responses indicating definitely yes = 1 versus other responses = 0 and totaling the number of “definitely yes” responses across the four items (range = 0–4, M = 3.1, SD = 1.4).

New risk beliefs, adults

In addition, we assessed the health risk beliefs associated specifically with the new FDA-proposed labels that were not explicit or implied in any of the existing Surgeon General’s Warning labels (also adapted from PATH, Hyland et al., Citation2016). Items for adults included: “Based on what you know or believe, does smoking cigarettes cause… [children to have breathing problems from secondhand smoke, lung disease in nonsmokers from secondhand smoke, stroke in smokers, and mouth cancer in smokers]. The response choices were Yes, No, and Not sure. We calculated a new health risk belief index by adding the number of responses for which respondents answered “yes” across the four items (range = 0–4, M = 3.32, SD = 1.04).

New risk beliefs, youth

We measured five items among youth (adapted from PATH, Hyland et al., Citation2016), for three of them asking, “do you believe cigarette smoking is related to… [health problems in non-smokers, stroke, and hole in the throat], as well as two related items posed as questions: Can smoking cigarettes kill you?, and Are cigarettes very addictive? Response choices ranged from 1 = definitely not to 4 = definitely yes. We again calculated a new health risk belief index by adding the number of responses for which respondents answered “definitely yes” across the five items (range = 0–5, M = 3.81, SD = 1.18).

Intentions to quit, adults

We measured quit intentions with three items adapted from the National Adult Tobacco Survey (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Citation2015):Do you want to quit smoking cigarettes for good? [Yes/No]; Do you have a time frame in mind for quitting? [Yes/No], and do you plan to quit smoking cigarettes for good… (In the next 7 days, In the next 30 days, In the next 6 months, In the next year, More than 1 year from now)? We created a dichotomous measure with planning to quit smoking in the next 6 months or earlier coded as “1” (22%) and not planning to quit, not having a time frame in mind, or planning to quit smoking in >6 months coded as “0.”

Susceptibility to smoke, youth

We gauged middle-school youth’s susceptibility to smoking using following five items, adapted from validated instruments developed by Pierce, Choi, Gilpin, Farkas, and Merritt (Citation1996) and Jackson (Citation1998): Do you think that… you will smoke a cigarette soon?, you will smoke a cigarette in the next year?, you will be smoking cigarettes in high school?, in the future you might try a cigarette?, And if one of your best friends offered you a cigarette would you smoke it? Response choices ranged from 1 = definitely not to 4 = definitely yes. We considered youth who answered anything other than “definitely not” to any question as susceptible to smoking. This process deemed 42% of the sample as susceptible.

Control variables and analytic approach

Adults

We measured a variety of factors known to predict quit intentions, including levels of nicotine dependence using the Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence (Fagerström, Citation2012), and past quit attempts (in the past 12 months; ). We assessed the impact of various warning label conditions on key dependent variables (DVs) using two methods: examining overlap of 95% confidence intervals between conditions () and using multivariable models (ordinary least squares (OLS) or logistic regression, depending on the DV’s level of measurement) to test for differences from the graphic FC condition while accounting for potential nonrandom assignment of demographics and risk factors ().

Table 1. Respondent demographics.

Table 2. Means and confidence intervals of dependent variables by condition.

Table 3. Regression models predicting visual fixation, negative affect, risk beliefs, and intention to quit (adults).

Youth

In addition, we measured several known predictors of smoking susceptibility, including previous smoking behavior (Have you ever tried smoking a cigarette, even one or two puffs? 8% answered “yes”), sensation seeking (using three items of a scale adapted for youth by Jensen, Weaver, Ivic, & Imboden, Citation2011; α = .78, M = 2.04, SD = .78), and whether anyone living in their home smoked cigarettes (53%; measure adapted from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Citation2014; see ). As with adults, we assessed the impact of various warning label conditions on key DVs by examining overlap of 95% CIs between conditions () and using multivariable models (OLS or logistic regression, depending on the DV’s level of measurement) to test for differences from the graphic FC condition while accounting for potential nonrandom assignment of demographics and risk factors ().

Table 4. Regression models predicting visual fixation, negative affect, risk beliefs, and susceptibility to smoke (youth).

Results

Visual attention

Adults

Results from the first three columns in and indicate that participants dwelled on the brand/logo area of the packs (bottom 50%) for more time in the SGW text condition than for any other condition with FDA text (FDA text only, graphic FC, and graphic B&W). Respondents viewing graphic FC warnings spent more time looking at the warning (top 50%) than those viewing graphic B&W or SGW text-only. In addition, participants looked at the image AOI (text excluded) longer if it was in color than if it was in black and white.

Youth

The results from the first three columns in and indicate that there were no differences by warning condition (excluding the brand-only control group) on visual attention to the brand/logo area of the packs (bottom 50%). Youth viewing graphic FC warnings spent more time looking at the warning (top 50%) than those viewing new FDA text-only. Youth also looked longer at the graphic part of the image (not the text) if it was in FC than if it was in B&W.

Negative affect

Adults

Respondents exposed to graphic warning labels (in FC or B&W) reported greater negative affect than those exposed to either text-only condition or the brand-only control ( and ). Respondents exposed to text-only labels (new FDA or SGW) also reported more negative affect than respondents exposed to the brand-only condition ().

Youth

Respondents exposed to any warning label (graphic or text-only) reported greater negative affect than those exposed to the brand-only control ( and 5).

Health risk beliefs, intentions to quit and smoking susceptibility

There were no significant differences (p < .05) between any of the randomized conditions in levels of risk beliefs (old or new) quit intentions, or smoking susceptibility (, and 5).

Discussion

Summary of findings

This study compared how exposure to less extensive alternatives to the full-color graphic warnings proposed by the FDA influences key variables proposed in the message impact framework. We observed some consistent patterns as well as differences across the two studies.

First, we find that graphic FC images hold visual attention. Both adult smokers and youth assigned to view FC graphic warnings spent more time looking at the graphic image (i.e., diseased lungs) than those who saw the same image in B&W. Adult smokers also looked at the overall warning for a longer period of time when assigned to graphic FC warnings compared to graphic B&W or SGW text-only versions, while youth looked at the graphic FC warnings longer than the FDA text-only warning. Differences in visual attention between graphic FC and other conditions, for both populations, were nonsignificant but similar in magnitude and always longest in the graphic FC conditions. We thus conclude that the overall pattern for both populations is consistent with the conclusion that graphic FC warnings garner the most attention, possibly owing to a combination of attracting viewers to the images and processing the new text.

Second, we find that warnings elicit negative affect. Among adult smokers, exposure to GWLs (in this case, both graphic FC and graphic B&W) produced greater negative affect than both text-only warning conditions and control. Whether these GWLs were in FC or B&W did not matter. Among middle-school youth, the pattern was quite different: exposure to any set of warning labels increased negative affect in participants compared to the control packs without warnings. Given that TCs argued that the U.S. government labels imposed emotionally charged message without any new health information, one key finding is that while warnings with images are highly associated with negative emotion for adults, the new labels do not necessarily generate any more emotion for youth than simply putting the SGWs warning on the front of the box.

Third, across both youth and adult smokers, those who viewed graphic FC warning labels did not report a significant increase in old or new risk beliefs, intentions to quit (among adult smokers), or susceptibility to smoke (among youth) compared to those assigned to other label conditions. All indices of risk beliefs were very high (suggesting the potential for ceiling effects), and we did not design our randomized experiments to have sufficient statistical power to detect effects on quit intentions or smoking susceptibility of the magnitude typically found in clinical trials or observational studies (e.g., Brewer et al., Citation2016; Noar et al., Citation2016b). The message impact framework (Noar et al., Citation2016a, Citation2016b) also suggests that these downstream effects are likely mediated by affective responses to warning labels. Thus, it is unreasonable to expect to observe direct effects on quit intentions or smoking susceptibility in response to a single session featuring 90 s of exposure. We did run a series of subsequent analyses in which we predicted (a) quit intentions as a function of all variables included in (excluding the warning label conditions but adding negative affect to the model) and (b) smoking susceptibility as a function of all variables included in (again excluding the warning label conditions but adding negative affect to the model). These analyses showed that the negative affect was a robust predictor of quit intentions among adult smokers (B = 0.30, odds ratio = 1.36, p = 0.04) and both new risk beliefs (standardized beta = 0.24, p < 0.001) and old risk beliefs (standardized beta = 0.23, p < 0.001) among youth. These results echo strong and consistent evidence from previous studies (e.g., Byrne et al., Citation2015; Brewer et al., Citation2016; Evans et al., Citation2015; Noar et al., Citation2016b) supporting the assertion that negative affect is likely to translate into favorable, downstream effects on quit intentions among smokers and health risk perceptions among (largely nonsmoking) youth.

Study implications

We offer mixed findings related to the claim that a less extensive regulation could satisfy the government’s compelling public health interest to reduce cigarette smoking rates. On the one hand, graphic FC warning labels do generate greater visual attention compared to other variations across the board, consistent with the argument that graphic FC warnings are an optimal configuration. This outcome is the most proximal DV from the message impact framework tested in the current study and thus might be expected to offer the clearest pattern of effects from a single, short-term warning label exposure. On the other hand, graphic FC labels produced levels of negative affect equivalent to graphic B&W labels among adults, while both graphic and text-only labels performed similarly in generating negative affect among (largely) nonsmoking youth. We thus cannot draw definitive conclusions about the degree to which graphic FC labels are necessary to achieve downstream public health goals. That said, we conducted these studies among two populations that one would expect to be very difficult to influence—adult smokers from highly disadvantaged socioeconomic backgrounds (who experience immense barriers to quitting) and middle-school youth at high risk of future smoking uptake (owing to high rates of living with smokers and similarly economically disadvantaged backgrounds). We thus conclude that the current study does not rule out the possibility that graphic FC warnings offer incremental benefits over less extensive alternatives, as is evidenced by a large international research base demonstrating that pictorial warnings result in intended effects over time. It is therefore plausible that the incremental benefits observed here may scale up toward a larger impact at the population level.

Limitations and future research

As noted above, it is important to consider that the exposure in this study takes place over 90 s. If FC warning labels are implemented in the United States, the levels and durations of exposure will be considerably longer and more frequent. We cannot speak the effects of repeated exposure to attention-grabbing, graphic FC warning labels. These studies reported here also rely on self-reported measures to gauge both emotional reactions and health risk beliefs, suggesting that future studies examine the effects of these label manipulations on behavioral outcomes measured over a longer period of time. In addition, we used brand imagery from three specific TCs in an effort to assess visual attention to warning labels versus branded content. However, our study did not include a variety of other brands that smokers may use regularly.

We did not examine the aspects of all of the legal challenges to the Tobacco Control Act. Particularly, the FDA has the authority to place GWLs on ads for cigarettes. Cigarette ads often market their product by depicting attractive, social youth engaged in cool activities. On the one hand, these visual depictions of benefits of smoking might distract from the warnings, but one could easily argue the opposite might be true. If warnings on ads distract from elements compelling youth to take up smoking, the warnings could provide a public health benefit.

Conclusion

This study offers new evidence on the relative importance of graphic full color, graphic black and white, and text-only cigarette warning labels in shaping visual attention, negative affect, and health risk beliefs. The results reveal that graphic full-color images held visual attention for a longer duration than less restrictive alternatives. Graphic images (whether in full color or in black and white) also produced higher levels of negative affect among adult smokers, but graphic images did not outperform text-only warnings of similar magnitude among at-risk but largely nonsmoking, middle-school youth. Findings raise important new questions about the optimal design of GWLs to increase cessation among adult smokers and increase understanding of the health risks of smoking among youth from socioecomically disadvantaged backgrounds.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or the Food and Drug Administration.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) and FDA Center for Tobacco Products (CTP) (R01HD079612).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Brewer, N. T., Hall, M. G., Noar, S. M., Parada, H., Stein-Seroussi, A., Bach, L. E., & Ribisl, K. M. (2016). Effect of pictorial cigarette pack warnings on changes in smoking behavior: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Internal Medicine, 176, 905–912. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.2621

- Byrne, S., Katz, S., Mathios, A., & Niederdeppe, J. (2015). Do the ends justify the means? A test of alternatives to the FDA proposed cigarette warning labels. Health Communication, 30, 680–693. doi:10.1080/10410236.2014.895282

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014). National Youth Tobacco Survey (NYTS). Atlanta, GA: Author. Retrieved April 12, 2017 from https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/surveys/nyts/.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2015). National Adult Tobacco Survey (NATS). Retrieved April 12, 2017 from https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/surveys/nats/.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016). Cigarette smoking among adults—United States, 2005–2015. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 65, 1205–1211. Retrieved April 12, 2017 from https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/65/wr/mm6544a2.htm

- Central Hudson Gas & Electric Corp. v Public Service Commission. (1980). 447 US 557. Retrieved from https://www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/447/557

- Corbin, C. M. (2014, July 7). Compelled disclosures. Alabama Law Review, 65, 1277–1352. Retrieved from https://ssrn.com/abstract=2258742

- Do, K. T., & Galván, A. (2014). FDA cigarette warning labels lower craving and elicit frontoinsular activation in adolescent smokers. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 10, 1484–1496. 10.1093/scan/nsv038

- Durkin, S., Brennan, E., & Wakefield, M. (2012). Mass media campaigns to promote smoking cessation among adults: An integrative review. Tobacco Control, 21, 127–138. http://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050345

- Evans, A. T., Peters, E., Strasser, A. A., Emery, L. F., Sheerin, K. M., & Romer, D. (2015). Graphic warning labels elicit affective and thoughtful responses from smokers: Results of a randomized clinical trial. PLoS ONE, 10(12), 1–23. http://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0142879

- Fagerström, K. (2012). Determinants of tobacco use and renaming the FTND to the Fagerström test for cigarette dependence. Nicotine and Tobacco Research, 14, 75–78.

- Fischer, P. M., Krugman, D. M., Fletcher, J. E., Fox, R. J., & Rojas, T. H. (1993). An evaluation of health warnings in cigarette advertisements using standard market research methods: What does it mean to warn? Tobacco Control, 2, 279–285. http://doi.org/10.1136/tc.2.4.279

- Hammond, D., Reid, J. L., Driezen, P., & Boudreau, C. (2013). Pictorial health warnings on cigarette packs in the United States: An experimental evaluation of the proposed FDA warnings. Nicotine and Tobacco Research, 15, 93–102. http://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/nts094

- Hammond, D., Thrasher, J., Reid, J. L., Driezen, P., Boudreau, C., & Santillán, E. A. (2012). Perceived effectiveness of pictorial health warnings among Mexican youth and adults: A population-level intervention with potential to reduce tobacco-related inequities. Cancer Causes & Control, 23(Suppl. 1), 57–67. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-012-9902-4

- Hyland, A., Ambrose, B. K., Conway, K. P., Borek, N., Lambert, E., Carusi, C., … Compton, W. M. (2016). Design and methods of the population assessment of tobacco and health (PATH) study. Tobacco Control, 1–8. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-052934

- Jackson, C. (1998). Cognitive susceptibility to smoking and initiation of smoking during childhood: A longitudinal study. Preventive Medicine, 27, 129–134. doi:10.1006/pmed.1997.0255

- Jenco, M. (2016, October 4). AAP, health groups file lawsuit pushing for graphic cigarette warnings. AAP News. Retrieved April 13th, 2017, from http://www.aappublications.org/news/2016/10/04/fdalawsuit100416

- Jensen, J. D., Weaver, A. J., Ivic, R., & Imboden, K. (2011). Developing a brief sensation seeking scale for children: Establishing concurrent validity with video game use and rule-breaking behavior. Media Psychology, 14, 71–95. doi:10.1080/15213269.2010.547831

- Keys, T. R., Morant, K. M., & Stroman, C. A. (2009). Black youth’s personal involvement in the HIV/AIDS issue: Does the public service announcement still work? Journal of Health Communication, 14, 189–202. doi:10.1080/10810730802661646

- Moodie, C., MacKintosh, A. M., & Hammond, D. (2010). Adolescents’ response to text-only tobacco health warnings: Results from the 2008 UK Youth Tobacco Policy Survey. European Journal of Public Health, 20, 463–469. doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckp199

- Noar, S. M., Francis, D. B., Bridges, C., Sontag, J. M., Brewer, N. T., & Ribisl, K. M. (2016a). Effects of strengthening cigarette pack warnings on attention and message processing: A systematic review. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly. [epub ahead fo print] doi:10.1177/1077699016674188

- Noar, S. M., Francis, D. B., Bridges, C., Sontag, J. M., Ribisl, K. M., & Brewer, N. T. (2016b). The impact of strengthening cigarette pack warnings: Systematic review of longitudinal observational studies. Social Science and Medicine, 164, 118–129. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.06.011

- Nonnemaker, J. M., Choiniere, C. J., Farrelly, M. C., Kamyab, K., & Davis, K. C. (2015). Reactions to graphic health warnings in the United States. Health Education Research, 30, 46–56. doi:10.1093/her/cyu036

- O’Keefe, D. J. (2002). Persuasion: Theory and research. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 16, 1–384.

- Peters, E., Lipkus, I., & Diefenbach, M. A. (2006). The functions of affect in health communications and in the construction of health preferences. Journal of Communication, 56(Suppl. 1), S140–S162. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.2006.00287.x

- Peterson, E. B., Thomsen, S., Lindsay, G., & John, K. (2010). Adolescents’ attention to traditional and graphic tobacco warning labels: An eye-tracking approach. Journal of Drug Education, 40, 227–244. doi:10.2190/DE.40.3.b

- Pierce, J. P., Choi, W. S., Gilpin, E. A., Farkas, A. J., & Merritt, R. K. (1996). Validation of susceptibility as a predictor of which adolescents take up smoking in the United States. Health Psychology, 15, 355–361. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.15.5.355

- R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company et al. vs. United States Food and Drug Administration. (2011). Civil Case No. 11-1482 (RJL). United States District Court for the District of Columbia.

- Ramanadan, S., Nagler, R. H., McLoud, R., Kohler, R., & Viswanath, K. (2017). Graphic health warnings as activators of social networks: A field experiment among individuals of low socioeconomic position. Social Science and Medicine, 175, 219–227. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.12.044

- Schneider, S., Gadinger, M., & Fischer, A. (2012). Does the effect go up in smoke? A randomized controlled trial of pictorial warnings on cigarette packaging. Patient Education and Counseling, 86, 77–83. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2011.03.005

- Slovic, P., Finucane, M. L., Peters, E., & MacGregor, D. G. (2004). Risk as analysis and risk as feelings: Some thoughts about affect, reason, risk, and rationality. Risk Analysis, 24, 311–322. doi:10.1111/j.0272-4332.2004.00433.x

- Thrasher, J. F., Arillo-Santillán, E., Villalobos, V., Pérez-Hernández, R., Hammond, D., Carter, J., … Regalado-Piñeda, J. (2012). Can pictorial warning labels on cigarette packages address smoking-related health disparities? Field experiments in Mexico to assess pictorial warning label content. Cancer Causes and Control, 23(Suppl. 1), 69–80.

- Tushnet, R. (2014, June). More than a feeling: Emotion and the first amendment. Harvard Law Review, 127, 2392.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2012). Preventing tobacco use among youth and young adults: A report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta. Retrieved from https://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/reports/preventing-youth-tobacco-use/

- U.S. Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act. H.R. 1256. (2009). Retrieved April 12, 2017 from https://www.congress.gov/bill/111th-congress/house-bill/1256.

- Vardavas, C. I., Connolly, G., Karamanolis, K., & Kafatos, A. (2009). Adolescents perceived effectiveness of the proposed European graphic tobacco warning labels. European Journal of Public Health, 19, 212–217. doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckp015

- Watson, D., & Clark, L. A. (1999). The PANAS-X: Manual for the positive and negative affect schedule-expanded form. Iowa City, IA: Iowa Research Online. Retrieved April 12, 2017 from, http://ir.uiowa.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1011&context=psychology_pubs

- 75 Fed.Reg. 69,524 (Nov. 12, 2010). Retrieved from, https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2010-11-12/pdf/2010-