ABSTRACT

While prior research has demonstrated the benefits of self-affirming individuals prior to exposing them to potentially threatening health messages, the current study assesses the feasibility of inducing self-affirmation vicariously through the success of a character in a narrative. In Study 1, college-age participants who regularly use e-cigarettes (N = 225) were randomly assigned to read one of two versions of a story depicting a college student of their own gender. The versions were identical except in the vicarious self-affirmation (VSA) condition, the main character achieves success (i.e., honored with a prestigious award) before being confronted by a friend about the dangers associated with their e-cigarette use; whereas in the vicarious control condition, the achievement is mentioned after the risk information. Results of the posttest and 10-day follow-up demonstrated that VSA reduced messages derogation, while increasing self-appraisal and perceived risk. The effect of VSA on e-cigarette outcomes was moderated by frequency of use, with heavier users benefiting the most. Study 2 (N = 152) confirmed that traditional value affirmation works with our stimuli on a comparable population.

When electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) were introduced into the United States in 2006, they were celebrated as a relatively less risky alternative to traditional cigarettes and a potential first step toward smoking cessation (Hajek, Etter, Benowitz, Eissenberg, & Mcrobbie, Citation2014). A decade later, however, e-cigarettes are gradually becoming one of the most common entry points for nicotine addiction (Abrams, Citation2014; Trumbo & Harper, Citation2013). In fact, recent data shows that e-cig users are 2.5 times more likely to start smoking regular cigarettes than non-users (Littlefield, Gottlieb, Cohen, & Trotter, Citation2015; Sutfin et al., Citation2015). Younger users have proven to be particularly susceptible to e-cigarettes.

Though regulatory legislation such as incorporating e-cigarettes into existing smoke free policies and consumer education will be critical to reversing this trend, the availability of information alone is not sufficient to change behavior. Users are notoriously resistant to anti-tobacco information, tending to deny its relevance and downplay their risk (Peretti-Watel et al., Citation2007). The current study builds upon prior work in self-affirmation theory, shifting the focus from communication strategies that emphasize guilt, risk, and fear to messages that enhance susceptibility to change by casting the self in a positive light.

Self-affirmation

According to self-affirmation theory, people are motivated to maintain a positive perception of the self (Steele, Citation1988). When faced with information that threatens that positive perception, individuals tend to counter the threat by focusing instead on a more positive aspect of the self (Cohen et al., Citation2007; Sherman et al., Citation2013). In the health context, this tendency may result in people rejecting or minimizing the relevance of information about threatening risks. Interestingly, by encouraging individuals to reflect on an important domain of the self before exposing them to a threatening message, self-worth can be preemptively bolstered in such a way as to bypass the defensive mechanisms that would otherwise inhibit persuasion (Steele, Citation1988; Steele & Liu, Citation1983; Sweeney & Moyer, Citation2015). This point has been further explored by Critcher, Dunning, and Armor (Citation2010), demonstrating that an a priori self-affirmation intervention tends to be effective in reducing defensiveness, whereas affirmations introduced after the threat are only effective if participants have yet to reach a defensive conclusion.

This unique capacity of self-affirmation to bypass resistance occurs because, presumably, a focus on strong and valued aspects of the self can offset the impact of threats in other domains, such that ego-defensive strategies (e.g., denial, rationalization, avoidance) are no longer needed (Davis, Soref, Villalobos, & Mikulincer, Citation2016). Another characteristic of self-affirmation that makes it a highly likely candidate for tobacco-related interventions is the fact that both self-affirmation and tobacco use have a recursive nature. Namely, attempting to stop using tobacco may often involve a cycle, in which initial failure discourages further attempts, prompting a continuing process of demotivation (Redish, Jensen, & Johnson, Citation2008). Given that early outcomes set the starting point in the initial trajectory of a recursive cycle and can therefore have disproportional influence (Cohen, Garcia, Purdie-Vaughns, Apfel, & Brzustoski, Citation2009; Sherman et al., Citation2013), an early self-affirming intervention could have the greatest impact on tobacco cessation.

While most studies within the self-affirmation tradition artificially induce participants with self-affirming cognitions, a recent line of research has explored whether people spontaneously self-affirm when under threat. Defined as the “extent to which people think about their values or strengths when they feel threatened” (Persoskie et al., Citation2015, p. 46), studies showed that spontaneous self-affirmation is associated with lower likelihood of cognitive impairments and positive affect among cancer survivors (Taber, Klein, Ferrer, Kent, & Harris, Citation2016). Others have found spontaneous self-affirmation to be a significant correlate of well-being (Emanuel et al., Citation2016), health-related information seeking (Taber et al., Citation2015), and willingness to receive self-threatening genetic risk information (Ferrer et al., Citation2015). Though spontaneous self-affirmation is a promising prospect for further research (Harris & Epton, Citation2010), its current implementation has not been without criticism. Excepting several notable studies (Brady et al., Citation2016; Toma & Hancock, Citation2013), the literature on spontaneous self-affirmation suffers from a more general limitation of relying on cross-sectional data, which limits the ability to promote causal claims or estimate whether spontaneous and traditional self-affirmation differ in important respects (Sparks & Jessop, Citation2016).

To date, the application of self-affirming interventions in everyday situations has been limited by two primary factors. First, self-affirming interventions typically require participants to complete an exercise, such as writing a brief essay about a value of importance (McQueen & Klein, Citation2006) or responding to a values in Action questionnaire (Kim & Niederdeppe, Citation2016). The degree of individual effort and intrusiveness involved makes such approaches impractical for large-scale interventions (Cohen & Sherman, Citation2014). Nearly all field studies of self-affirmation have been conducted in an educational context, where essays can seamlessly be integrated into everyday activity (for a review see Cohen & Sherman, Citation2014). Second, the theory fails to account for selective exposure whereby individuals often actively avoid threatening messages (Case, Andrews, Johnson, & Allard, Citation2005). Thus, even if users are encouraged to be more receptive to threatening information, the question remains of whether individuals will willingly seek out this information when not under the constraints of a laboratory experiment. To utilize self-affirmation and reduce resistance to threatening health messages, both of these issues – the need for naturalistic methods to promote self-affirmation and selective exposure – must be addressed. Below we put forth one potential vehicle – narratives.

Narrative persuasion

Interest in fictional narratives that integrate health-related information has grown in recent years (Braddock & Dillard, Citation2016). Conventional nonnarrative modes of delivering information, such as informational brochures or public service announcements, include didactic styles of communication that appeal to reason (Kreuter et al., Citation2010). As such, traditional nonnarrative health messages depend heavily on an audience’s motivation to rationally process information, and may be subject to resistance as individuals seek to distance themselves from threats. In contrast, narratives that embed the risk information within a coherent story leverage cognitive and emotional involvement to engage the audience and reduce resistance (Moyer-Gusé, Citation2008).

One of the central postulates of narrative persuasion is that involvement with fictional characters can mimic interpersonal influence. By observing modeled behavior, “people may vicariously experience the full spectrum of challenges and expectations of a certain behavior and, in the process, acquire the knowledge and skills needed to successfully perform the behavior” (Lu, Baranowski, Thompson, & Buday, Citation2012, p. 201). This effect appears to be particularly pronounced when narratives involve characters perceived as similar to the audience or with whom the audience identifies (Hinyard & Kreuter, Citation2007). This is not to suggest that the vicarious experience should be equated with direct experience; yet, the literature provides compelling evidence that individuals can change their attitudes and behavior when witnessing members of important groups engage in a desired behavior (Bandura, Citation1977). These findings are attributed to the highly-developed ability of individuals at estimating other people’s thoughts and emotions by imagining how they would act and feel in similar situations. If high involvement in a story allows the audience to experience the mental and emotional state of a character, it opens the possibility of stimulating self-affirmation vicariously through the character. If so, narratives could expand the reach and impact of self-affirmation well beyond its previous applications.

Vicarious self-affirmation (VSA)

Broadly speaking, traditional research designs of self-affirmation effects on health-related outcomes consist of two distinct components: a self-focused task (such as writing about a value important to you) and a persuasive message advocating a change of behavior (or belief) practiced by the self. The order in which these elements are presented can determine whether individuals will be more receptive to the threatening information (Critcher et al., Citation2010). Affirming after a threat (i.e., persuasive message → self-focused task) often encourages biased processing, while an a priori self-affirmation (i.e., self-focused task—persuasive message) preemptively reduces the perceived threat and induces higher levels of receptivity. Translating this procedure to a vicarious experience would require an additional component, where individuals identify with a mediated character who self-affirms. Under these conditions, cognitive and emotional involvement with a self-affirming character may prompt corresponding self-affirmation for the audience member as well.

One of the key indicators of self-affirmation is the extent to which self-affirmed individuals derogate the threatening message. By discounting, deprecating, and minimizing the relevance of health information, individuals can restore and maintain their self-integrity. Compared to their nonaffirmed counterparts, self-affirmed individuals are less likely to derogate threatening health-related information and more likely to accept the information as accurate and relevant (van Koningsbruggen & Das, Citation2009). Moreover, Napper, Harris, and Epton (Citation2009) developed and validated a scale of self-appraisal as a proxy for self-affirmation demonstrating that, compared to nonaffirmed participants, self-affirmed individuals have a more positive self-appraisal. Therefore, the first step in assessing the feasibility of VSA should test the ability of a narrative with a self-affirmed character to influence message derogation and self-appraisal. Based on this logic, the following hypotheses were posed:

H1:

VSA will have a significant effect on a) message derogation; and b) self-appraisal, such that vicariously affirmed participants will tend to report lower levels of message derogation and higher self-appraisal, compared to participants in the vicarious control condition.

H2:

VSA will have a significant effect on e-cigarette-related outcomes, including a) e-cigarette risk perceptions; and b) intentions to stop using e-cigarettes, such that vicariously affirmed participants will tend to report on higher risk perceptions and an increase in intention to stop using e-cigarettes, compared to participants in the control condition.

H3:

The effect of VSA on e-cigarette risk perceptions and intentions to stop using e-cigarettes, will be mediated by a) message derogation; and b) self-appraisal.

In addition, the perceived risk associated with health messages is proportional to the perceived relevance of the health threat, as stronger effects are usually observed for those at greatest risk (Harris & Napper, Citation2005). Simply put, if a college student rarely uses e-cigarettes, there is little reason to expect that health-related information regarding this practice would significantly threaten their self-integrity. Namely, e-cigarettes are likely to be peripheral to their self-perception and would, presumably, provoke little motivation to engage in defensive processing. Conversely, someone who uses e-cigarettes daily should have a greater resistance to information challenging this behavior. Based on this, the final hypothesis was posed:

H4:

The effect of VSA on e-cigarette-related outcomes will be moderated by frequency of e-cigarette use, such that stronger effects will be recorded for heavier users.

Study 1

Method

Participants and procedure

Recruitment was conducted through a paid survey panel of American college age e-cigarette users maintained by Qualtrics. After screening for age (18–28), English fluency, and e-cigarette use, participants were notified that they would be contacted 10 days after the initial questionnaire to respond on a follow-up survey. Of the 354 consenting participants who responded to the first questionnaire, 231 were successfully recontacted 10 days later for the follow-up survey. Six participants were removed from the final sample due to unrealistic response time or missing data leaving a final sample of 225. Based on an a priori power analysis with G*Power 3.1 (Faul, Erdfelder, Buchner, & Lang, Citation2009), a sample of 220 was the target. To ensure that attrition was unrelated to the experimental conditions, a series of ANCOVAs were conducted, yielding no significant interactions between attrition and experimental condition. Participants were 49.1% female; Mage = 25.92, SD = 2.62; 79% White, 10.7% Hispanic, 5.8% Black, 3.1% Asian. Most (61.3%) had more than 6 months of experience with e-cigarettes and 50.7% used e-cigarettes more than twice a week. The most common achieved education was high school (36%), followed by 4-year college degree (29.8%), Master’s degree (12%), and professional degree (7.6%).

Participants were randomly assigned to a vicarious affirmation condition and a vicarious control condition. To match participants and the principal narrative character on gender, the questionnaire opened with questions regarding sociodemographic information, including gender, age, and race. In the subsequent section, participants were given a fictional story, titled “All in All, a Good Day,” and instructed to read it carefully. After reading the short story, participants responded on scales measuring message derogation, self-appraisal, perceived risk of e-cigarettes, as well as behavioral intent to use e-cigarettes in the next 2 years. Ten days after the initial questionnaire was administered, participants were recontacted for the follow-up questionnaire, which included identical measurements of perceived risk and behavioral intent.

Material

The stimulus attempted to fulfill three functions: identification with the main character, affirmation, and the presentation of risk information related to e-cigarette use. Specifically, in both conditions, the 20-paragraph story began by introducing the main character (Rachel or David matching the gender of the participant). Namely, Rachel/David is portrayed as typical college student who uses e-cigarettes, has disagreements with their roommate, and juggles academic and personal commitments. A key point in the story occurs when the protagonist receives an email informing them that they have been selected to receive a prestigious award for academic and civic achievements. This recognition performs the function of self-affirmation for the character by bolstering positive self-image. Mimicking the traditional value list task (McQueen & Klein, Citation2006), this passage highlights various important aspects of the self-image that are unrelated to the threatened domain (i.e., e-cigarette use). Later, on meeting their best friend and sharing the news regarding their achievement, the main character decides to cancel their lunch plans to buy a refill for his/her e-cigarette. The friend uses this opportunity to confront the main character and recount the risks associated with e-cigarettes. This exchange functions as the threating message in the narrative—analogous to the sort of information provided by traditional health brochures. The health-related message in the story was based on information from the FDA and the American Lung Association websites focusing on facts and debunking misconceptions associated with e-cigarette use (see Appendix 1).

The fundamental distinction between the experimental conditions was the order in which these events were presented in the narrative. In the vicarious affirmation condition, the main character learns of the achievement first, and later faces the threatening information. In the vicarious control condition, the character’s achievement comes after it receives the threatening information. Other than this distinction, the narratives were identical in content and structure.

Measures

Message derogation was gauged with four items on a five-point Likert scale (Nan & Zhao, Citation2012), asking participants whether they believe that the information about e-cigarettes in the story was “exaggerated,” “distorted,” “overstated,” and “overblown” (α = .90). To assess the extent to which the story focused participants’ attention on positive self-aspects, a scale of self-appraisal was adopted from Napper et al. (Citation2009), using a bipolar seven-point scale. The items followed the stem, “the story made me think about…” and included “things that are important to me/things that are not important to me” (α = .85). Intentions to smoke e-cigarettes in the future were assessed with a single item, asking participants to estimate the likelihood that in the next 2 years they “will stop using e-cigarettes entirely.” The e-cigarette perceived risk scale was adapted from the National Adult Tobacco Survey (CDC, Citation2013) and consisted of three items, evaluating the extent to which e-cigarettes were perceived as “addictive,” “harmful,” and “risky.” Issue-involvement was assessed with the frequency of e-cigarette use, ranging from 1 – “less than once a month” to 11 – “a few times each day.” The questionnaire concluded with various sociodemographic variables, including experience with e-cigarettes, general health, level of education, religious affiliation, political ideology, and income, as well as an unobtrusive measurement of the time spent reading the short story in seconds (M = 189.30, SD = 108.87).

Analysis of the data began with assessments of differences across conditions utilizing independent samples t-tests in SPSS version 21. This was followed with a mediation and moderation analyses in PROCESS (Hayes, Citation2013).

Results

As indicated from the results of the independent samples t-tests, the randomization procedure was successful in creating two relatively equivalent groups (for specifics see Appendix 2). Independent samples t-tests were also used to examine whether VSA had the intended effect on common self-affirmation indicators (see ). As hypothesized, participants in the vicarious affirmation condition exhibited lower levels of message derogation; t(223) = 2.66, p = .008, than their counterparts in the vicarious control condition (M = 2.52, SD = 1.12; M = 2.91, SD = 1.08; respectively), and higher levels of self-appraisal; t(223) = 1.97, p = .04, than those participants who were exposed to the vicarious control stimulus (M = 4.99, SD = 1.19; M = 4.69, SD = 1.16; respectively). In total, H1 was supported as the manipulation checks for VSA followed the pattern of results associated with traditional self-affirmation interventions.

Table 1. Means (SDs) by condition and outcome: Studies 1 and 2.

A statistically significant difference was observed for perceived risk, and behavioral intent at follow-up. As hypothesized, participants in the vicarious affirmation condition tended to report higher levels of perceived risk of e-cigarettes both at posttest and at follow-up. Interestingly, differences in behavioral intent were not recorded at the immediate posttest, however, at follow-up 10 days later, participants in the vicarious affirmation condition had significantly higher levels of intention to stop using e-cigarettes in the future, compared to the vicarious control condition. Further, the only unobtrusive measurement in this study also points to the effectiveness of VSA. That is, vicariously affirmed participants spent significantly more time reading the narrative compared to their counterparts in the vicarious control condition t(223) = 2.54, p = .008.

To assess the hypothesized mediation for the effect of VSA on perceived risk and behavioral intent,Footnote1 we used PROCESS (Model 4 set at 10,000 bootstrapped samples with CI of 95%) (Hayes, Citation2013), controlling for time spent reading the stimulus.Footnote2 In agreement with our hypothesis, the effect of VSA on perceived risk was significantly mediated through message derogation (b = .08, SE = .06, 95% CI [.004, .231] and self-appraisal (b = .07, SE = .05, 95% CI [.004, .214]. Overall, this mediation model accounted for 15.04% of the variance in perceived risk [F (4,220) = 9.74, p < .001]. With regard to behavioral intent, the mediation analysis did not record a significant effect for derogation (b = .01, SE = .05, 95% CI [-.078, .124] or self-appraisal (b = .08, SE = .06, 95% CI [-.004, .216]. Accordingly, this model accounted for 11.21% of the explained variance in behavioral intent [F (4,220) = 6.94, p < .001]. Thus, we were able to find only partial support for H3 and the role played by message derogation and self-appraisal as mediators of VSA effects. summarizes the direct unstandardized effects of VSA, message derogation, and self-appraisal on perceived risk and behavioral intent.

Figure 1. Unstandardized beta coefficients for the direct effects of VSA, message derogation, and self-appraisal on perceived risk and behavioral intent, controlling for reading time.

Note. *p < .05, **p < .01.

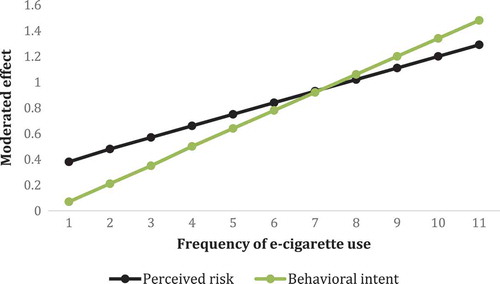

We used the simple moderation model in PROCESS (Model 1 set at 10,000 bootstrapped samples) to estimate whether the frequency of e-cigarette use plays a significant role in increasing the impact of VSA.Footnote3 The analysis indicated that issue-involvement was a significant moderator for the effect of VSA on perceived risk; b = 0.18, SE = 0.06, t(221) = 3.18, p = .002, ΔR2 = .037, and behavioral intent to stop using e-cigarettes; b = 0.10, SE = 0.05, t(221) = 1.99, p = .047, ΔR2 = .018. presents the moderated effect of VSA on perceived risk and behavioral intent.

Discussion: Study 1

Study 1 found support for the basic hypothesis that narratives can enhance perceptions of the self and increase receptivity to tobacco-related information. In turn, bolstering of the self and acceptance of health information lead to more accurate assessments of risk. Further, this pattern of results seems to be especially pronounced among heavier e-cigarette users. At this point, though it is somewhat tempting to suggest that VSA mimics the underlying mechanism of traditional value affirmation, the results of Study 1 should be interpreted with a degree of caution. Namely, the recorded effects are limited to a single stimulus and a unique context. More importantly, Study 1 does not offer a comparison between vicarious affirmation and traditional affirmation conditions in the context of e-cigarette use among college students. In order to partially address these gaps, Study 2 examines whether a similar pattern of results is obtained while using a traditional manipulation of self-affirmation.

Study 2

Analogous to Study 1, recruitment took place on Qualtrics and participants were required to be between 18 and 28 years of age, to be fluent speakers of English, and to have been using e-cigarettes. Overall, 152 consented participants were recruited and randomly assigned to either the traditional self-affirmation (n = 73) or the control condition (n = 79). Self-affirmation was induced with a typical value-list exercise, in which participants were asked to choose their most important value on a list provided (i.e., kindness, honesty, generosity, independence, and success) and write a short paragraph describing the relevance of this value to their everyday life. Participants in the traditional control condition were not given a filler task, as previous research has shown that even non-reflective tasks can be used to self-affirm (Cohen, Aronson, & Steele, Citation2000). Then, all participants were exposed to a message highlighting the risks of e-cigarette use. To make sure that the health-related information was identical in terms of factual content and its salience to the stimulus from Study 1, we piloted several versions of the health message among a convenience sample of students (n = 32).

Results

Based on the results of independent samples t-tests, self-affirmed participants reported on higher self-appraisal (M = 5.02, SD = 1.64) and lower message derogation (M = 2.65, SD = 1.11), compared to the levels of self-appraisal (M = 4.30, SD = 1.57) and message derogation (M = 3.12, SD = 1.08) among nonaffirmed participants; t(150) = 2.76, p = .001; t(150) = 2.54, p = .008, respectively. Further, as indicated in , the self-affirmation manipulation had a significant effect on intent to stop using e-cigarettes t(150) = 2.58, p = .03, such that self-affirmed individuals reported on higher intent (M = 4.81, SD = 1.98), compared to their counterparts in the nonaffirmation condition (M = 4.04, SD = 1.69). Finally, with respect to perceived risk associated with e-cigarette use, there was no significant difference; t(150) = 1.61, p = .13 between individuals in the self-affirmation condition (M = 4.86, SD = 1.50) and the control condition (M = 4.46, SD = 1.56).

Discussion: Study 2

While Study 1 demonstrated the effect of VSA in the context of e-cigarette use, Study 2 investigated whether parallel results could be found with compatible sample and a traditional value affirmation task. In concert with the literature, self-affirmed participants reported higher levels of self-appraisal and lower levels of message derogation. More importantly, compared to their nonaffirmed counterparts, individuals who were self-affirmed using the traditional manipulation of writing about a value important to them had higher intent to stop using e-cigarettes.

General discussion

Concerns have been growing about the public health implications of the increasing popularity of e-cigarettes. However, educational efforts typically assume that the individuals involved in risky behavior are willing to listen, process the information in an unbiased manner, and eventually change their behavior. This is rarely the case. Thus, it is imperative that Tobacco Regulatory Science consider effective communication strategies when crafting legislation. To this end, the present study sought to test whether self-affirming narratives can reduce resistance and increase acceptance of potentially threatening risk information.

The results show a relatively consistent pattern, whereby vicarious affirmation increased participants’ susceptibility to the persuasive message, compared to the control condition. Analogous to traditional self-affirmation interventions, VSA reduced message derogation and heightened self-appraisal. Thus, simply by having the narrative first introduce positive information regarding the main character and then present the threatening message about e-cigarettes, the design prompted a more positive appraisal of the self and encouraged a more balanced processing of risk information.

As indicated by the mediation analysis, the effect of VSA on perceived risk regarding e-cigarettes was mediated by message derogation and self-appraisal. This suggests that reduced derogation and a more positive self-appraisal were successfully translated into an increase in the perceived risk of e-cigarettes. This finding is particularly important because it not only supports the potential of VSA to affect risk perceptions, but also lends credence to the assumption that the underlying mechanism of VSA is similar to that of traditional self-affirmation. While the analysis of the 10-day follow-up data recorded a significant direct effect of VSA on behavioral intent to stop using e-cigarettes in the next 2 years, these effects were nonsignificant at immediate posttest, and the mediation analysis did not indicate that message derogation or self-appraisal play any relevant role in affecting behavioral intent

In line with previous studies of self-affirmation, stronger effects were recorded for individuals who reported more frequent use of e-cigarettes. We found that higher risk participants were more sensitive to the intervention, which resulted in increased acceptance of narrative-consistent positions.

The current study is subject to several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, while the results inform us regarding college-age e-cigarette users, it remains to be seen whether and how VSA could be implemented to target other populations and health disparities. It is also important to bear in mind that the reliance on self-report data poses a substantial limitation. Given that the processing of information was not assessed in the current study, the extent to which participants internalized the message and how resistant they might be when confronted with counterarguments or social pressure to use e-cigarettes remains unclear. Finally, it should be noted that the current study did not provide a direct comparison between VSA and traditional self-affirmation.

Overall, the findings support the concept of VSA as a feasible strategy to enhance receptivity to tobacco-related messages, especially among at-risk populations. As well as being theoretically significant, the results also offer practical contributions. VSA may provide a potential solution to one of the most paradoxical scenarios in awareness campaigns: namely, that the most at-risk individuals are also those most likely to actively avoid important information. Further, traditional forms of persuasion often use threatening messages in an attempt to attract the attention of intended recipients, scare them into processing the information, and act in response to the message (Ferguson & Phau, Citation2013). Yet among tobacco users, exposure to a threatening message of this kind often arouses a high level of anxiety that can prove counterproductive (Yzer, Cappella, Fishbein, Hornik, & Ahern, Citation2003). A route to persuasion that entails a bolstering of the self rather than an explicit threat to self-integrity is therefore a valuable alternative.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank the guest editors, Joseph N. Cappella and Seth Noar, who were particularly insightful and instrumental in guiding the paper throughout the review process. They are also grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments on the paper.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the FDA Center for Tobacco Products and the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number P50CA180905. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or the Food and Drug Administration.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Given that the follow-up data did not include measurements of message derogation and self-appraisal, the mediation analysis only reports on the posttest data.

2. Acknowledging the confounding potential of reading time, all models treat this variable as a covariate.

3. The follow-up measures were used for the moderation analysis.

References

- Abrams, D. B. (2014). Promise and peril of e-cigarettes: Can disruptive technology make cigarettes obsolete? JAMA, 311, 135–136. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.285347

- Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84, 191–215. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191

- Braddock, K., & Dillard, J. P. (2016). Meta-analytic evidence for the persuasive effect of narratives on beliefs, attitudes, intentions, and behaviors. Communication Monographs, 7751, 1–24. doi:10.1080/03637751.2015.1128555

- Brady, S. T., Reeves, S. L., Garcia, J., Purdie-Vaughns, V., Cook, J. E., Taborsky-Barba, S., … Cohen, G. L. (2016). The psychology of the affirmed learner: Spontaneous self-affirmation in the face of stress. Journal of Educational Psychology, 108, 353–373. doi:10.1037/edu0000091

- Case, D. O., Andrews, J. E., Johnson, J. D., & Allard, S. L. (2005). Avoiding versus seeking: The relationship of information seeking to avoidance, blunting, coping, dissonance, and related concepts. Journal of the Medical Library Association, 93, 353–362.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013). National Adult Tobacco Survey (NATS). Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/surveys/nats/

- Cohen, G. L., Aronson, J., & Steele, C. M. (2000). When beliefs yield to evidence: Reducing biased evaluation by affirming the self. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 26, 1151–1164. doi:10.1177/01461672002611011

- Cohen, G. L., Garcia, J., Purdie-Vaughns, V., Apfel, N., & Brzustoski, P. (2009). Recursive processes in self-affirmation: Intervening to close the minority achievement gap. Science, 324, 400–403. doi:10.1126/science.1170769

- Cohen, G. L., & Sherman, D. K. (2014). The psychology of change: Self-affirmation and social psychological intervention. Annual Review of Psychology, 65, 333–371. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115137

- Cohen, G. L., Sherman, D. K., Bastardi, A., Hsu, L., McGoey, M., & Ross, L. (2007). Bridging the partisan divide: Self-affirmation reduces ideological closed-mindedness and inflexibility in negotiation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93, 415–430. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.93.3.415

- Critcher, C. R., Dunning, D., & Armor, D. A. (2010). When self-affirmations reduce defensiveness: Timing is key. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 36, 947–959. doi:10.1177/0146167210369557

- Davis, D., Soref, A., Villalobos, J. G., & Mikulincer, M. (2016). Priming states of mind can affect disclosure of threatening self-information: Effects of self-affirmation, mortality salience, and attachment orientations. Law & Human Behavior, 40, 351–361. doi:10.1037/lhb0000184

- Emanuel, A. S., Howell, J. L., Taber, J. M., Ferrer, R. A., Klein, W. M., & Harris, P. R. (2016). Spontaneous self-affirmation is associated with psychological well-being: Evidence from a US national adult survey sample. Journal of Health Psychology, 5, 1–8. doi:10.1177/1359105316643595

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang, A. G. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G* Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods, 41, 1149–1160. doi:10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149

- Ferguson, G., & Phau, I. (2013). Adolescent and young adult response to fear appeals in anti-smoking messages. Young Consumers, 14, 155–166. doi:10.1108/17473611311325555

- Ferrer, R. A., Taber, J. M., Klein, W. M. P., Harris, P. R., Lewis, K. L., & Biesecker, L. G. (2015). The role of current affect, anticipated affect and spontaneous self-affirmation in decisions to receive self-threatening genetic risk information. Cognition and Emotion, 29, 1456–1465. doi:10.1080/02699931.2014.985188

- Hajek, P., Etter, J. F., Benowitz, N., Eissenberg, T., & Mcrobbie, H. (2014). Electronic cigarettes: Review of use, content, safety, effects on smokers and potential for harm and benefit. Addiction, 109, 1801–1810. doi:10.1111/add.12659

- Harris, P. R., & Epton, T. (2010). The impact of self-affirmation on health-related cognition and health behaviour: Issues and prospects. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 4, 439–454. doi:10.1111/j.1751-9004.2010.00270.x

- Harris, P. R., & Napper, L. (2005). Self-affirmation and the biased processing of threatening health-risk information. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31, 1250–1263. doi:10.1177/0146167205274694

- Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Hinyard, L. J., & Kreuter, M. W. (2007). Using narrative communication as a tool for health behavior change: A conceptual, theoretical, and empirical overview. Health Education & Behavior, 34, 777–792. doi:10.1177/1090198106291963

- Kim, H. K., & Niederdeppe, J. (2016). Effects of self-affirmation, narratives, and informational messages in reducing unrealistic optimism about alcohol-related problems among college students. Human Communication Research, 42, 246–268. doi:10.1111/hcre.12073

- Kreuter, M. W., Holmes, K., Alcaraz, K., Kalesan, B., Rath, S., Richert, M., … Clark, E. M. (2010). Comparing narrative and informational videos to increase mammography in low-income African American women. Patient Education and Counseling, 81, S6–S14. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2010.09.008

- Littlefield, A. K., Gottlieb, J. C., Cohen, L. M., & Trotter, D. R. (2015). Electronic cigarette use among college students: Links to gender, race/ethnicity, smoking, and heavy drinking. Journal of American College Health, 63, 523–529. doi:10.1080/07448481.2015.1043130

- Lu, A. S., Baranowski, T., Thompson, D., & Buday, R. (2012). Story immersion of videogames for youth health promotion: A review of literature. Games for Health, 1, 199–204. doi:10.1089/g4h.2011.0012

- McQueen, A., & Klein, W. M. P. (2006). Experimental manipulations of self-affirmation: A systematic review. Self and Identity, 5, 289–354. doi:10.1080/15298860600805325

- Moyer-Gusé, E. (2008). Toward a theory of entertainment persuasion: Explaining the persuasive effects of entertainment-education messages. Communication Theory, 18, 407–425. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2885.2008.00328.x

- Nan, X., & Zhao, X. (2012). When does self-affirmation reduce negative responses to antismoking messages? Communication Studies, 63, 482–497. doi:10.1080/10510974.2011.633151

- Napper, L., Harris, P. R., & Epton, T. (2009). Developing and testing a self-affirmation manipulation. Self and Identity, 8, 45–62. doi:10.1080/15298860802079786

- Peretti-Watel, P., Constance, J., Guilbert, P., Gautier, A., Beck, F., & Moatti, J. P. (2007). Smoking too few cigarettes to be at risk? Smokers’ perceptions of risk and risk denial, a French survey. Tobacco Control, 16, 351–356. doi:10.1136/tc.2007.020362

- Persoskie, A., Ferrer, R. A., Taber, J. M., Klein, W. M. P., Parascandola, M., & Harris, P. R. (2015). Smoke-free air laws and quit attempts: Evidence for a moderating role of spontaneous self-affirmation. Social Science and Medicine, 141, 46–55. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.07.015

- Redish, D. A., Jensen, S., & Johnson, A. (2008). A unified framework for addiction: Vulnerabilities in the decision process. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 31, 415–487. doi:10.1017/S0140525X0800472X

- Sherman, D. K., Hartson, K. A., Binning, K. R., Purdie-Vaughns, V., Garcia, J., Taborsky-Barba, S., … Cohen, G. L. (2013). Deflecting the trajectory and changing the narrative: How self-affirmation affects academic performance and motivation under identity threat. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 104, 591–618. doi:10.1037/a0031495

- Sparks, P., & Jessop, D. C. (2016). “Spontaneity is a meticulously prepared art”: Commentary on Taber et al. (2016). Associations of spontaneous self-affirmation with health care experiences and health information seeking in a national survey of US adults. Psychology & Health, 31, 310–312. doi:10.1080/08870446.2016.1145437

- Steele, C. M. (1988). The psychology of self-affirmation: Sustaining the integrity of the self. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 21, Social psychological studies of the self: Perspectives and programs pp. 261–302). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

- Steele, C. M., & Liu, T. J. (1983). Dissonance processes as self-affirmation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 45, 5–19. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.45.1.5

- Sutfin, E. L., Reboussin, B. A., Debinski, B., Wagoner, K. G., Spangler, J., & Wolfson, M. (2015). The impact of trying electronic cigarettes on cigarette smoking by college students: A prospective analysis. American Journal of Public Health, 105, e83–e89. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2015.302707

- Sweeney, A. M., & Moyer, A. (2015). Health psychology self-affirmation and responses to health messages: A meta-analysis on intentions and behavior self-affirmation and responses to health messages. Health Psychology, 34, 149–159. doi:10.1037/hea0000110

- Taber, J. M., Howell, J. L., Emanuel, A. S., Klein, W. M. P. P., Ferrer, R. A., & Harris, P. R. (2015). Associations of spontaneous self-affirmation with health care experiences and health information seeking in a national survey of US adults. Psychology & Health, 446, 1–18. doi:10.1080/08870446.2015.1085986

- Taber, J. M., Klein, W. M. P., Ferrer, R. A., Kent, E. E., & Harris, P. R. (2016). Optimism and spontaneous self-affirmation are associated with lower likelihood of cognitive impairment and greater positive affect among cancer survivors. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 50, 198–209. doi:10.1007/s12160-015-9745-9

- Toma, C. L., & Hancock, J. T. (2013). Self-affirmation underlies Facebook use. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 39, 321–331. doi:10.1177/0146167212474694

- Trumbo, C. W., & Harper, R. (2013). Use and perception of electronic cigarettes among college students. Journal of American College Health, 61, 149–155. doi:10.1080/07448481.2013.776052

- van Koningsbruggen, G. M., & Das, E. (2009). Don’t derogate this message! Self-affirmation promotes online type 2 diabetes risk test taking. Psychology & Health, 24, 635–649. doi:10.1080/08870440802340156

- Yzer, M. C., Cappella, J. N., Fishbein, M., Hornik, R., & Ahern, R. K. (2003). The effectiveness of gateway communications in anti-marijuana campaigns. Journal of Health Communication, 8, 129–143. doi:10.1080/10810730305695

Appendix 1All in All, a Good Day (Male – A Priori Affirmation)

The sound of my alarm cuts through my sleep, and I half open my eyes, groping for my phone to turn it off. For a moment I lie still, just barely resisting the urge to sink back into sleep. This week has already felt so long, and honestly, I’d love nothing more right now than to call in sick and spend the whole day in my pajamas binge watching Game of Thrones and eating junk food in bed. It’s tempting. So very, very tempting.

I groan, and force myself out of bed. I grab a towel and stumble to the shower, only to find that Alex has used up all the hot water. Again. And as an added bonus, he’s thoughtfully left his wet towel crumpled up on the floor next to his overflowing laundry hamper. I consider myself a pretty patient person, but he’s really been pushing the limits of basic roommate etiquette lately. Dirty dishes piling up in the sink, TV blasting at night when I’m trying to study, rent check a little late each month. I’m going to have to talk to him about it. I’m not looking forward to it. A year ago it would have been simple - we would’ve settled it all with a mock fight that ended with both of us laughing and ordering a pizza to seal the peace. But lately… I dunno. We were best friends in high school, and were so excited to move in together when we started college. But now he’s got his frat, and I’ve been busy with all my other stuff, and we’ve just sort of drifted apart, I guess. I know that’s normal, but it just makes these kind of “official roommate business” conversations weirdly formal and awkward.

I rinse in the cold water as quickly as possible, dress, and pack my bag, mentally checking off what I’ll need for the day: cellphone, laptop, notebook, pens. I grab my nametag and apron for the campus coffee shop where I work too. I wasn’t supposed to be scheduled for today, but Sean begged me to fill in for him so he could surprise his girlfriend for their anniversary, and who am I to stand in the way of romance? I feel an involuntary pang in my heart at the thought. It’s been a month since Sara and I broke up. I know it was for the best and I swear I really am pretty much over it at this point, but it still creeps up on me sometimes when I see other couples enjoying their stupid, perfect coupledom. Thanks for rubbing it in, Sean.

I shake off the thought, and reach automatically for my vape pen, only to remember that I used up the last of the juice before bed last night. Beautiful. Nothing like a freezing shower and an empty tank to start the day off. I shove the device into my pocket. I’ll need to swing by a vape shop after class. There’s no way I’m making it through class and work without a few moments to relax and vape. Coffee will have to tide me over until then.

By the time class is over the coffee’s long gone. As I make my way out of the lecture hall, I fish out my phone and scroll idly through my email. Coupons from some store I don’t remember ever shopping at, reminder from Mom to call Grandma for her birthday, emails about a group project due next week, and … one subject line makes me pause: “Congratulations on your achievement.” For a second I think it has to be spam, but the email address is a school one. I click on the link:

Dear David,

We are pleased to inform you that you have been selected for the 2016 Dean’s Award for Academic and Civic Achievement.

Each year university faculty are encouraged to nominate exceptional students who both maintain the highest academic standards and demonstrate a passion for service. This year the awards committee received many excellent candidates, but we were particularly impressed with your efforts in developing a technology literacy program for local seniors, while consistently remaining in the top 10% of your class academically.

In recognition of your achievements, we are pleased to offer you a personal letter of commendation from the Dean. In addition, the university will be making a financial contribution to your organization to further assist you in continuing and expanding your program.

Congratulations on this well-earned recognition. We look forward to following your progress as you continue in your academic and personal pursuits.

The email ends with the flourish of an official-looking signature and details about an award ceremony taking place at the end of the semester.

For a moment I sit there stunned, then a grin spreads across my face. I wonder who nominated me. I wish I knew so I could thank them. All those late nights studying and weekends at the library hosting workshops… It can feel like a lot sometimes, but it’s completely worth it, and this award is just the boost I need at the end of a long school year. And a donation to the program- that could be huge! That could cover the cost of printing more brochures and guides, maybe even new computers or iPads for the workshops!

The whole thing started half-accidentally last year after I helped my grandma set up her new iPad. She told one of her friends, who told one of her friends, and before I knew it I found myself organizing a whole program around it with the local library. Grandma likes to jokingly calls it “Gadgets for Geezers,” but the truth is it really is awesome to see how much of a difference it can make for people, especially if they’re usually pretty much confined at home because of health or mobility issues. Suddenly they’re Skyping with children and grandchildren across the country, connecting with friends and family on Facebook, downloading books and movies, looking up information about health and medications, taking care of bills and appointments online– all the kind of stuff we often take for granted. I even have one “student” (it still feels weird saying that) who’s planning to launch his own YouTube channel. I’ve been wanting to expand the program for a while now, so maybe with this boost I can really make it happen!

I hear someone shout my name and look up to see my friend Cory coming towards me. I rush over to him and hand him my phone, indicating the message, “look what I just got!”

“David!” he exclaims after a quick scan of the message, “that’s amazing! You totally deserve it!” I laugh a little sheepishly, but the truth is I am proud of myself!

“You’ve got some time before work, right?” He asks.

I glance at my watch. “A little, yeah.”

“Great. We’re going to celebrate,” Cory declares. “Come on, if we hurry we can make it over to that new place we’ve been wanting to try for lunch.”

I nod enthusiastically and we set off to the restaurant. Without thinking, I reach into my pocket for my vape pen to enjoy on the way, and remember that it’s empty. Damn. The vape shop’s in the other direction, I won’t have time to get there and go to lunch before work.

“Hey,” I say, slowing to a stop. “Mind if I take a rain check on lunch?”

Cory looks puzzled, “Is everything okay?”

“Oh yeah,” I reassure him, waving the pen, “just need a refill.”

Cory gives me an odd look. “Seriously?” he asks.

“Yeah, sorry. It’s just that I have to go now if I’m going to make it before work.”

“Come on, we should be celebrating! And if you’re so hooked that even now you feel like you have to have one…”

I laugh him off, “Oh, come on. You’re exaggerating. It’s not a big deal. I just like having a little throughout the day.”

“That stuff’s bad for you” he says bluntly. “I read an article the other day that said e-cigarettes aren’t nearly as safe as a lot of people think.”

“It’s just water vapor!” I protest.

Cory shakes his head insistently and pulls out his phone, tapping in a search. “The chemical and particles in the vapor can mess with your lungs. Look,” she says, pointing to a government webpage she’s pulled up. “This says a lot of eLiquids have carcinogens and things like …. I don’t know how to pronounce this half of this stuff … Diacetyl, acetoin, and pentan…pentanedione. Whatever.” He grimaces, and continues, “However you say it, the point is that they cause – and I quote, ‘irreversible, life-threatening lung disease bronchiolitis obliterans – also known as popcorn lung.’”

There’s an admittedly gruesome looking picture of a deformed looking lung on the screen. I push it away. “Don’t be disgusting. I don’t even vape that much. Plus it’s not like they’re real cigarettes. You can’t get addicted to these things.”

Cory’s still reading. “Not according to this. Don’t be fooled by the eLiquid flavors - all that watermelon, bubblegum, caramel candy stuff. That might seem harmless, but ecigs still have nicotine, which is as addictive as heroin. So on top of all the chemicals and popcorn lung stuff they’re inhaling, people do get hooked, and a lot of them end up switching to real cigarettes”

“What?!” I have to jump in. There’s no way that can be right. “Lots of people vape to help them quit smoking,” I remind him.

Cory shakes his head. “Actually it looks like the opposite could be happening - people who use e-cigarettes are twice as likely to start smoking regular cigarettes as people who don’t. Plus, you have to admit that for people our age a lot of the time they start vaping for fun, not to quit smoking. Sound familiar?” He gives me a pointed look and continues.

“This says that college students and young adults are some of the heaviest users of e-cigarettes. And it’s getting more common - the number of young adults who vape regularly tripled between 2011 and 2013. So think about it - if more and more people are vaping, basically ecigs could end up creating more smokers, not fewer.”

I search for a good response. “Well, I don’t even vape that much…” I say again. But it sounds unconvincing even to me, and I trail off.

“Look,” Cory says, softening at my expression. “I’m just worried about you, that’s all.” He gives me a quick hug. “We’ll do lunch another time.”

Home at last. I drop my bag and apron in a heap by the door and wander into the kitchen. I’m surprised to find it freshly cleaned. Looks like Alex is out, but there’s note on the kitchen table “Heard a rumor that you got some good news today! Leftover pizza in the fridge. Game of Thrones marathon this weekend?”

I smile and settle in on the couch with a slice. All in all, a good day.