ABSTRACT

This study assessed the effects of the February through September 2016 American news media’s coverage of Zika Virus (ZIKV) risk on the U.S. public’s familiarity, knowledge and behavior in the form of interpersonal discussions. A content analysis (N = 2,782 pieces) revealed that the Rio Olympic Games elicited a spike in coverage of Zika. We also found that newsworthy and easy- to- depict aspects of the disease, specifically its transmission by mosquitoes and its relation to microcephaly were covered more extensively than its sexual transmission and transmissibility from an infected person who is asymptomatic. Nevertheless, survey data over the same period of time (N = 37,180 respondents) revealed that the general amount of coverage, rather than the specifics about Zika transmission and its consequences, influenced the public’s familiarity, knowledge, and behavior.

Like other public health crises, epidemics such as Zika Virus (ZIKV) pose a threat to the physical and psychological well-being of citizens (Coombs, Citation2009). While the health threats are real, and Zika can cause both microcephaly (Mlakar et al., Citation2016) and Guillain-Barre Syndrome (GBS) (Cao-Lormeau et al., Citation2016), it is not the consequences themselves but rather risk perceptions that influence the public’s reactions and behaviors (Kasperson et al., Citation1988; Pidgeon & Henwood, Citation2010). Although crisis management officials, such as those of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), are able to communicate directly to some in the public through social media (Glowacki, Lazard, Wilcox, Mackert, & Bernhardt, Citation2016), and one-on-one communication between doctors and patients has impact as well, the mass media remain an important vehicle for communication to the public (Ophir, Citation2018; Renn, Citation1991; Southwell, Dolina, Jimenez-Magdaleno, Squiers, & Kelly, Citation2016). Accordingly, understanding the ways in which the media covered the Zika outbreak, and the resulting effects on both perceptions of risk and individual behavior may prove useful for health professionals called upon to manage future outbreaks of infectious diseases.

In order to capture the dynamic nature of the ZIKV outbreak in the United States, this study relies on a large-scale nationally representative survey and a parallel analysis of legacy media content over an eight and a half month period, from February 12, 2016 to September 26, 2016. Using time series analyses, we correlate media coverage and Americans’ risk perceptions in this period. We also assess whether perceptions are influenced by the total amount of coverage, the amount of coverage dedicated to specific Zika-related issues, neither, or both.

Epidemics and the mass media

The spread of new or recurring diseases can develop into public health crises (Coombs, Citation2009; Covello, Peters, Wojtecki, & Hyde, Citation2001). Crisis communication techniques, including warnings, risk assessments, notifications, and information about symptoms and medical treatments, are among the important steps public health officials take to reduce the harm and slow the spread of infectious diseases (Veil, Reynolds, Sellnow, & Seeger, Citation2008).

Communicating risks to the public is challenging for a number of reasons. First, studies have shown substantial gaps between experts’ and lay persons’ understandings of risks (Morgan, Fischhoff, Bostrom, Lave, & Atman, Citation1992). While scientists tend to focus on ways to mitigate the dangers that may result from events (hazard), the public’s response may be more emotional (Sandman, Citation1993), with emotions affected by factors such as sense of self-efficacy and control of one’s ability to reduce risk (Sandman, Citation1987). In addition, non-experts may find it difficult to understand the technical information surrounding the risk assessment (Rowan, Citation1991). Finally, crisis situations can be more challenging than other risk communication circumstances because they require messaging about risks in the face of extreme, sudden dangers (Lundgren & McMakin, Citation2013). Unsurprisingly, then, the public’s understanding of outbreaks is often not optimal (Petts, Draper, Ives, & Damrey, Citation2010).

Studies have shown that when trying to acquire information related to prevention of diseases, people often seek health information from non-medical sources, such as the mass media (Lewis, Citation2017; Lewis et al., Citation2012). As a result, communication experts have stressed the need to rely on these channels during crises (Reynolds & Seeger, Citation2005).

The media’s construction of a public health event as a crisis, as happened during the Zika outbreak, is consequential. As argued by Rosenthal and colleagues, “if CNN defines a situation as a crisis, it will indeed be a crisis in all its consequences” (Rosenthal, Boin, & Comfort, Citation2001, p. 12). Because they are mysterious, dramatic, spread rapidly, characterized by a high number of infections and carry economic and political consequences, generally speaking, widespread disease outbreaks are newsworthy (Galtung & Ruge, Citation1965; O’Neill & Harcup, Citation2009). Studies show that the volume of coverage during epidemics may influence risk perceptions and protective behaviors (Chan et al., Citation2018). However, the effect of the media on people’s reactions to a crisis extends beyond putting the topic on the agenda. By framing, the media decide what to emphasize and what to omit from coverage (D’Angelo & Kuypers, Citation2010; Entman, Citation1993). According to the Social Amplification of Risk Framework (SARF), several “stations”, including the mass media, alter risk messages before transmitting them to the public. In the process, some components of the message are filtered out (Chang, Citation2012) while others are emphasized (Kasperson et al., Citation1988). Because audiences are sensitive to media reports during epidemics (Srinivasan, Citation2010), the dissemination of altered risk information can “shape the social experience of risk, thereby contributing to risk consequences” (Kasperson et al., Citation1988, p. 181). Aspects of a crisis that are not reported in the news may remain unknown to the public, and thus result in an attenuation of risk (Kasperson & Kasperson, Citation1996; Mazur, Citation1984). Moreover, in order for a message to be effective in eliciting beliefs about risk it may need to be repeated several times.

The media tend to report on different epidemics using recurrent coverage patterns shaped by journalistic values and routines (Tuchman, Citation1973; Vasterman, Scholten, & Ruigrok, Citation2008). Routines that may affect the coverage of epidemics include issue-attention cycles (Shih, Wijaya, & Brossard, Citation2008), a tendency to focus on economic and political aspects of a story (Ophir, Citation2018), and standardized assessments of newsworthiness (Galtung & Ruge, Citation1965). Newsworthiness is determined by subjective criteria used by journalists to assess the “goodness” of stories, defined as their judged importance, quality (e.g., completeness and pace), novelty, and fit to the requirements of the medium (Gans, Citation1979). In the process, the press prioritizes events that are intensive (in size, negativity, and drama), relevant to local audiences, culturally proximate, and that refer to elites (Galtung & Ruge, Citation1965). These criteria predict the amount of coverage (Shoemaker & Reese, Citation1996). Because the criteria for newsworthiness tend to be similar across media channels (Golan, Citation2006), different outlets tend to prioritize and neglect the same facets (McCombs & Shaw, Citation1972). For example, studies of the coverage of scientific topics have found that events that emphasize risks associated with demographics (e.g., race, gender, age) or risky lifestyle behaviors (e.g., alcohol consumption) are more likely to elicit media reports (Stryker, Citation2002). Additionally, journalists prefer messages that are visually appealing and hold audience attention (Golding & Elliott, Citation1979; Shoemaker & Reese, Citation1996).

On the other hand, some aspects of scientific events can reduce newsworthiness. Specifically, Pellechia has argued that “features such as caveats, statements of limitations and qualifications, long recognized as an important feature of scientific papers, will often be omitted from popularized accounts” (Pellechia, Citation1997, p. 62). Because the media have a strong preference for the dramatic and sensational (Green, Citation1985; Lawrence & Mueller, Citation2003), event characteristics that may reduce dramatic perceptions often receive less media attention. In this study, we identify the menu of information available to reporters by considering Zika as a specific case with unique aspects and risk features. By analyzing the newsworthiness value of different aspects of Zika, we predict the topics that will dominate coverage. The effect of these topics on public perceptions can then be assessed to understand the amplification and attenuation processes.

ZIKV and the 2015–2017 epidemic

ZIKV is a Flavivirus, sharing similarities with Yellow fever, West Nile, Japanese Encephalitis, and Dengue (Tang et al., Citation2016). First discovered in a Ugandan forest in 1947 (Gatherer & Kohl, Citation2016), the virus initially attracted little scientific and public attention, mainly because the symptoms in most cases were either undetected or mild and resembled those of other diseases (McNeil, Citation2016). Notice of Zika increased in the medical community when an outbreak in 2015 in Brazil was followed by an increase in the number of newborns diagnosed with birth defects, and specifically microcephaly, a rare neurological condition in which infants’ heads and brains are abnormally under-sized (Rasmussen, Jamieson, Honein, & Petersen, Citation2016). In addition to the dangers that the virus poses to the fetus of an infected pregnant woman (França et al., Citation2016), people of all ages are susceptible to Guillain-Barré Syndrome, a rare immune disease associated with ZIKV that can lead to permanent disability or death (Cao-Lormeau et al., Citation2016).

A ZIKV outbreak was declared to be an emergency by the Brazilian government in December 2015. The disease’s main path of transmission was through insects who carry the pathogen, especially Aedes Aegypti mosquitoes, existing in 30 U.S states (Broutet et al., Citation2016). Among the factors increasing the prevalence of ZIKV stories in news was concern that athletes and spectators from around the globe would be exposed to ZIKV at the Rio Olympic Games in the summer of 2016 (Massad, Coutinho, & Wilder-Smith, Citation2016).

In January 2016, the CDC published travel guidelines with a special focus on women who are or are intending to become pregnant (Petersen et al., Citation2016). A first case of locally-acquired transmission in Puerto Rico had been reported by the CDC on December 31, 2015 (Hennessey, Fischer, & Staples, Citation2016), and on February 1st 2016 the World Health Organization (WHO) declared Zika to be a public health emergency (Cauchemez et al., Citation2016). Another path of transmission was identified when several cases of sexual transmission were confirmed (D’Ortenzio et al., Citation2016). As a result, several countries promulgated recommendations urging the use of condoms and in some cases avoiding or delaying pregnancy when one of the partners in a sexual relationship is infected (Aiken et al., Citation2016).

According to CDC, the most pressing issues that needed to be communicated to the public were transmission by mosquitoes and sex, the consequences of contacting ZIKV, especially microcephaly, and the fact that Zika infection is often asymptomatic (Anderson, Thomas, & Endy, Citation2016) . Nevertheless, as we noted earlier, not all significant aspects of an event receive coverage in U.S media (Shoemaker, Danielian, & Brendlinger, Citation1991). Not only are some more newsworthy than others (Ekblad, Citation2013), but also when covering risk issues the media prioritize visually compelling topics (Greenberg, Sachsman, Sandman, & Salomone, Citation1989). In part, this prioritization is the result of the ability of evocative images to increase attention (Lang, Citation2000), emotional responses (Joffe, Citation2008) and recall of stories (Niederdeppe, Bu, Borah, Kindig, & Robert, Citation2008). For example, the visual evocativeness of obesity makes the disease more newsworthy than sedentary behavior which is difficult to telegraph visually (Chau, Bonfiglioli, Chey, & Bauman, Citation2009). Because the intense bleeding associated with Ebola is dramatic, it is unsurprising that, during the 2014 outbreak in the Congo, the frequency and severity of this symptom were often exaggerated in media portrayals (Alter, Citation2017; Pokharel, Citation2015). In the case of Zika reporting, we expected a great deal of coverage of dramatic, risk-driven information that was readily depicted, specifically, images of mosquitoes and babies with microcephaly. Sexual transmission, on the other hand, had the potential to be newsworthy because it was an important means of transmission, but was more difficult to depict. Moreover, ZIKV’s association with microcephaly and with transmission by mosquitoes were suspected earlier than its sexual transmission and were thus central to the original coverage. Additionally, the specific forms of infectious sexual contact took time to confirm. While we did expect to see some indirect depictions of sexual transmission, namely condoms and contraceptives, we hypothesized that the coverage of sexual transmission would be less prevalent than that of mosquitoes as a vector and microcephaly as a worrisome potential effect of exposure. Finally, the asymptomatic nature of most Zika cases may reduce newsworthiness, as it is more difficult to visualize than other diseases’ symptoms, e.g., Ebola’s association with bleeding (Hewlett & Hewlett, Citation2007), and has less visual-impact (Greenberg et al., Citation1989). The notion of contagion in the absence of symptoms is difficult to grasp; yet one can have and transmit ZIKV without feeling or seeming ill. Since visually evocative content satisfied news criteria (O’Neill & Harcup, Citation2009) we hypothesized that:

H1: The coverage of mosquitoes and microcephaly will be more extensive than that of sexual transmission, which, in turn, will be more extensive than reporting on the asymptomatic nature of most ZIKV infections.

Newsworthiness is often driven by connection to elite people and countries (Galtung & Ruge, Citation1965; Golding & Elliott, Citation1979). In some cases, real world events that are relevant to multiple elite countries can become media events (Dayan & Katz, Citation1994). The Olympic Games are such events (Price & Dayan, Citation2009). Moreover, the ZIKV outbreak that began in Brazil months before the opening of the Rio Olympic games of 2016 heightened the possibility of ZIKV transmission to athletes and fans from around the globe who planned to travel to Brazil. Although we anticipated peaks in coverage driven by new information about the disease itself (findings, announcements etc.), we expected the coverage of Zika to be greatest around the Olympic Games:

H2: The US media coverage of Zika will peak around Zika-relevant events (defined as developments in the behavior of or reaction to the disease), but especially around the Olympic Games, with peak coverage immediately before and during the Olympics.

The first two hypotheses examine the media coverage of Zika in terms of emphasis and amount. To address its effects on the public, we combined our findings from the content analysis with a nationally representative longitudinal survey we conducted during the outbreak. Zika was mostly unknown to Americans before the 2015 outbreak (McNeil, Citation2016). As a result, a first goal of crisis communication about Zika was to increase familiarity with the phenomenon (Rowan, Citation1991). Such awareness can result from the agenda-setting function of mass media (McCombs & Shaw, Citation1972). As argued earlier, exposure is a key element in increasing familiarity with health topics (Hornik, Citation2002). Due to the importance of agenda setting in health contexts (Jones, Denham, & Springston, Citation2006), we assumed (but verified) that as the amount of coverage of ZIKV in the media increased, so did the public’s familiarity with the disease.

However, we also aimed to test the effect of amplification of specific facets of the crisis on specific knowledge. Crisis communication attempts to heighten people’s understanding of risk and risk prevention (Rowan, Citation1991). In the case of ZIKV, that information included the vector (mosquitoes) and sexual infection paths, the health risk of microcephaly, and the asymptomatic character of the disease. As argued earlier, the news media tend to emphasize some aspects of epidemics and underplay others (Kasperson et al., Citation1988). They are criticized by scholars who believed that the omission of important information will lead to gaps in knowledge and inaccurate risk perceptions among audiences. The resulting ignorance in turn could impede crisis management efforts (Kasperson & Kasperson, Citation1996).

However, others have argued that the media’s role during an epidemic goes beyond duplicating and amplifying the messages of crisis management organizations (Reynolds & Seeger, Citation2014). For example, Vasterman and colleagues argued that the media should be seen as an actor operating “in a social context where other actors like the government are also active” (Vasterman et al., Citation2008, p. 336). In that sense, the media may complement rather than amplify the governmental and medical messages, for example by raising awareness and triggering information seeking (Lewis, Citation2017). Both approaches, the one seeing media as an amplification station and the one conceptualizing it as a complementary actor, support the notion that media coverage should increase specific knowledge. However, it is not clear whether it is the general coverage or the reporting about specific aspects that will generate knowledge. Accordingly, we hypothesized that:

H3: Due to expected differences in coverage (H1), people will be more knowledgeable about microcephaly and mosquito-transmission than sexual transmission and the asymptomatic nature of the disease.

RQ1: Will specific knowledge about microcephaly, mosquito-borne infections, sexual transmission, and the asymptomatic nature of Zika be influenced by the general amount of coverage, or by the amount of coverage of these specific aspects?

A final goal of crisis communication is increasing the likelihood that audiences will take appropriate action (Lundgren & McMakin, Citation2013). One key behavioral outcome that may result from exposure to health information is an increase in the amount of interpersonal discussion and information- seeking from family and friends (Moyer-Gusé, Chung, & Jain, Citation2011) as well as from professionals (Kennedy, O’Leary, Beck, Pollard, & Simpson, Citation2004). Seeking additional information is important, in part, because of knowledge’s positive association with engagement in health behaviors (Ramírez et al., Citation2013). Similarly, discussions of health topics can increase their salience in people’s minds (Wanta & Wu, Citation1992) and also reduce risky behavior and resulting negative health outcomes (Moyer-Gusé et al., Citation2011). This chain of activities can be seen as an enhancement of the agenda setting effect of media exposure (McCombs & Shaw, Citation1972). Due to the effect of exposure on information- seeking through interpersonal discussion, we hypothesized that:

H4: The amount of media coverage of Zika in a given time period will predict the amount discussion with family and friends about Zika.

Method

Media coverage

Six coders performed a content analysis of broadcast and cable, print and online media containing at least one mention of the term “Zika.” The media items analyzed included articles published between February 12, 2016 and September 26, 2016 in large circulation U.S. newspapers, including The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, USA Today and The Washington Post. Print content was collected using the online information and research tool, Factiva. The word “Zika” was entered into the search bar. The option “In the last year” was selected from the ‘Date’ drop down menu. The default settings of “All Authors,” “All Subjects”, “All Industries” and “All Regions” were left untouched. Only the four newspapers listed above were selected—all other sources were excluded. Print articles appeared in the hard-copy versions of the newspapers. In addition to print media, Factiva also indicates whether the content from one of the traditional print sources is found on its online site. If so, the content was downloaded and analyzed as an online source. Online sources included nytimes.com, washingtonpost.com, wsj.com (Wall Street Journal), and usatoday.com. The corpus also included online articles directly collected from The Huffington Post and National Public Radio (NPR) websites.Footnote1 To access Zika-related articles on The Huffington Post, coders used the URL http://www.huffingtonpost.com/news/zika/. To access Zika-related articles on npr.org and theguardian.com/us, “Zika” was entered and searched using the websites’ search toolbars. Coders coded both the website stories and radio reports (audio if available, and transcripts otherwise) posted online. They omitted any articles that contained passing mentions of Zika without providing content that could be coded in the instrument.

The broadcast networks ABC, CBS and NBC, and the cable networks CNN, Fox News Channel and MSNBC were included in the analysis as well (the original videos, not transcripts, were coded). Broadcast and cable media content was collected using the TV News Archive, found at Internet Archive (archive.org). Only content broadcast on air or on cable was included in the analysis. The word “Zika” was searched using the search toolbar on the website. The media sources were searched individually using the “Network” drop down menu. The box ‘Date- Most Recent’ was selected. Duplicate broadcasts were omitted. In the event of a duplicate, Pacific Standard Time (PST) and Pacific Daylight Time (PDT) broadcasts were favored and selected over Eastern Standard Time (EST) broadcasts.

The items coded were those included on the ongoing national weekly survey of Zika awareness, attitudes, and behaviors. The final coding instrument focused on analysis of print, audio, and visuals. The content portion of the survey was divided into broad categories such as the transmission of Zika, the health effects of Zika, steps and guidelines to protect oneself against Zika, and Zika occurrence in the U.S. The coders undertook intensive reliability training using the coding instrument. Intercoder-reliability was measured with a random sample of 50 stories from print, online, and television. Each person coded the same set of stories. Intercoder reliability (Krippendorff’s Alpha) for the items analyzed in this study was .98 for sexual contact, .93 for microcephaly, .82 for asymptomatic character, and .76 for mosquitoes.

The final corpus consisted of 2,783 news items, of which 1,105 were online articles, 1,119 broadcast news items, 461 print and newspaper articles, and 98 radio news items. More information about the amount of news items per source could be obtained from the authors.

Survey

A total of 37,180 people (19,009 females; 25,252 whites, 14,780 college graduates, 5,652 from Florida) between the ages of 18 and 97 (M = 53.81, SD = 20.52) were surveyed by SSRS between February and September 2016, as part of a national U.S survey about Zika during the same time window used for the content analyzed in this study. The response rate changed between weeks, ranging between 6% and 11%. Samples were drawn to represent the adult US population and used a fully-replicated, single-stage, random-digit-dialing (RDD) sample of landline telephone households and cell-phones. Within each landline household, a single respondent (youngest adult) was selected and, for cell-phone respondents, interviews were conducted with the person answering the phone. Approximately, 35 interviews were conducted weekly in Spanish. All procedures were approved by the University of Pennsylvania’s Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Due to the questionnaire’s breadth, constructs were measured using single items. The items used in the survey were created for the purpose of this study, and attempted to represent what was known to scientists and available to the public about Zika at the time we began collecting the data. One item, regarding sexual transmission, that was originally based on the CDC’s interim guidance regarding sexual transmission (Oster et al., Citation2016) was changed after March 26 to accommodate the discovery that the virus could be sexually transmitted from male to male (Petersen et al., Citation2016). However, due to this change, we did not use this item for the time series analysis (see details below). General familiarity was assessed through the item “How familiar are you with news reports about the ZIKV?” Knowledge about transmission was measured using the items “Just your best guess, how do scientists think someone can get the ZIKV? By being bitten by a mosquito that has already bitten someone who has the ZIKV/By having sexual intercourse with someone who has the ZIKV”. Knowledge about the asymptomatic nature was measured through the reversed scored item “How accurate it is to say that an individual who has been infected by the ZIKV will know it because the ZIKV always produces noticeable symptoms?” Interpersonal discussions were measured through the item “In the past week, how many days, if any, did you discuss the effects of the ZIKV with family or friends?”. Familiarity and knowledge were measured on a Likert scale (From 1, very unlikely to 4, very likely for Knowledge, and from 1, very unfamiliar to 4, very familiar for Familiarity), and interpersonal discussions with an open-ended, numeric answer. The fact that survey responses were collected in only 165 days out of the 226 dates for which content analysis was conducted resulted in missing data for these dates. To compensate, we used data imputation, a process by which missing values are replaced by estimation based on other data points (Allison, Citation2001). Imputation was computed using linear weighted moving average, where each was estimated based on the two points before and after the missing value. The use of linear weights means that the observation directly next to the missing value is weighted as two times more influential than the one next to it. Imputation was not conducted for sexual transmission knowledge and asymptomatic character knowledge as there were too many missing data points for the imputation to be reliable (45% of the days included in the analysis included missing data for knowledge about asymptomatic character and 61% for knowledge about sexual contact). Missing data for variables that were imputed ranged between 27% (Familiarity) and 36% (Discussions in past week).

Results

Descriptive statistics

Overall, familiarity with Zika coverage was moderately-high (M = 2.92, SD = 0.94). Knowledge about mosquito (M = 3.32, SD = 0.87) and sexual (M = 2.89, SD = 1.08) transmission were moderately-high as well. Knowledge about the asymptomatic nature of Zika was moderate on average (M = 2.68, SD = 0.95). On average, people discussed Zika with family and friends on less than one day in the past week (M = 0.71, SD = 1.37) with 22,340 people (60.0%) reporting not discussing Zika at all in the week before being surveyed.

Hypotheses tests and research questions

To test the model suggested by hypotheses 1–2, a volume analysis over time was conducted, calculating the total number of articles per week. H1 predicted that the coverage of Zika will be dominated by topics that are more newsworthy and easy to visualize. Specifically, it hypothesized that microcephaly and mosquitoes will be more prevalent in coverage than sexual transmission, which in turn will be more prevalent than the asymptomatic character of Zika.

As expected, mosquitoes (1,857 articles, 66.7% of total amount of articles) and microcephaly (841, 30.2%) were the most prevalent topics in the corpus, followed by sexual transmission (618, 22.2%) and asymptomatic character (358, 12.8%). H1 was thus supported. A further analysis showed variance in the coverage of these topics between outlets. Mosquito coverage in individual outlets ranged between 54.7% (ABC) and 82.3% (NPR website), microcephaly ranged between 14.4% (Fox News) and 73.7% (The Huffington Post), sexual contact ranged between 13.0% (MSNBC) and 42.8% (The Huffington Post Blog), and asymptomatic character ranged between 4.5% (NBC) and 22.9% (USAToday website). When looking at media type, transmission by mosquitoes ranged between 59.8% (TV broadcasts) and 71.9% (Online articles), microcephaly as an effect between 16.0% (TV broadcasts) and 41.6% (Online articles), sexual contact as a mode of transmission between 14.1% (TV broadcasts) and 28.8% (Online articles), and ZIKV’s often asymptomatic character between 7.4% (TV broadcasts) and 16.9% (Online articles).

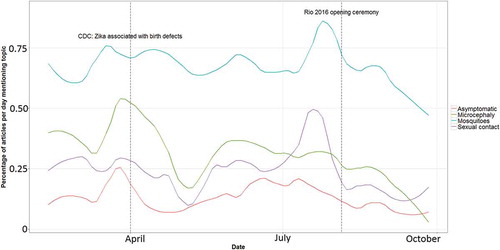

H2 predicted that amount of coverage would peak around Zika-related events, but would be at its highest value around the Rio Olympic Games. As can be seen in , the amount of coverage peaked around important Zika-related events, such as the CDC’s announcement that Zika causes birth defects, the Senate’s voting on Zika funding, and Florida’s confirmation of local cases. Nevertheless, as expected, the coverage was at its highest volume around the Olympic Games:

Figure 1. Amount of total coverage of Zika in the corpus with vertical labels on the dates of major Zika-related and events.

As can be seen in , the coverage of specific topics also changed over time, with mosquitoes, microcephaly, and asymptomatic transmission peaking just before the CDC’s announcement that ZIKV is associated with birth defects (although a suspected association was discussed months earlier, and was included as a reason for the WHO’s announcement of emergency, it was confirmed by CDC officials only on April 13, 2016). Another peak in the coverage of mosquitoes and sexual contact is evident just before the Olympic Games’ opening ceremony.

Hypothesis 3 predicted that people on average will be more knowledgeable about microcephaly and mosquito-borne infection than sexual transmission, and least knowledgeable about the asymptomatic nature of Zika. Knowledge about microcephaly was highest (M = 3.35, SD = .79), followed by mosquitoes (M = 3.31, SD = .86). Knowledge about sexual transmission in general (M = 2.89, SD = 1.07), and transmission through sex with men (M = 2.83, SD = 1.10) were lower. Knowledge about the asymptomatic nature of the disease was lower than microcephaly and mosquitoes (M = 2.68, SD = .94). T-tests found that all differences were significant (p < .05). H3 was supported.

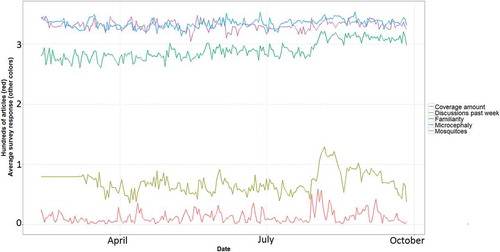

To test RQ1 and hypotheses 4–5, a time series analysis was conducted through the VARS package in R, using a vector autoregressive model that allows each variable in the model to have an influence on all other variables.Footnote2 Since the range of coverage per day in the corpus was 1–59 articles, with a mean of 12.31 and a standard deviation of 10.22, it did not make sense to measure the effect of an increase of one article. To make the model more ecologically valid, we tested the effect of increasing the amount by 10 articles (i.e., the amount variable in the model was computed as amount/10). A similar move used to increase interpretability of changes in variables was used, for example, by Dunlop and colleagues in a study on the effects of exposure to antismoking television advertising (Dunlop, Cotter, Perez, & Wakefield, Citation2013). Changes in the amount of coverage along with changes in survey responses can be seen in .

Figure 3. Averaged (daily) survey responses and total amount of coverage.

Note: For visual purposes, the amount of articles presented in units of hundreds. Discussions in the last weeks was measured with an open numeric question. Familiarity and knowledge were measured on a 4-points Likert scales.

We first examined whether when the amount of coverage of ZIKV in the media increases, so too does the public’s reported familiarity with the disease. A Granger-causality analysis with a lag = 1 day (selected automatically based on the model fit indicator of Schwarz criterion) showed that amount of coverage on a given day increased the average familiarity on the next day (b = .019, p < .001), after controlling for the effect of familiarity on the day before (b = .747, p < .001) and other variables in the model. The Granger causality test for amount was significant (F(4, 1,095) = 6.34, p < .001). Thus, the amount of coverage predicted changes in familiarity above and beyond the effects of familiarity on the previous day. Importantly, all of the effects reported above and in the following paragraphs represent changes in the dependent variables with the increase of 10 articles per day and thus accumulate to stronger effects when considering the actual changes in volume.

RQ1 asked whether knowledge about specific aspects of Zika will be influenced by the total amount of coverage, or by the coverage of these aspects. The vector-autoregressive models and further Granger-causality tests revealed that the amount of coverage of specific issues did not predict knowledge about these issues on the next day when controlling for autoregression and other variables in the model. This was true for mosquitoes transmission (F(4, 1,095) = 6.34, p = .231), and microcephaly (F(4, 1,095) = 6.34, p = .877). However, the total amount of coverage did Granger-cause changes in other variables in the model (F(4, 1,095) = 6.34, p < 0.001). An increase in amount of coverage had a significant effect on knowledge about mosquitoes the next day (b = .005, p < .001) after controlling for the autoregressive effect of knowledge (b = .43, p < .001) and other variables in the model. Similarly, an increase in the amount of coverage increased knowledge about microcephaly (b = .008, p < .001), controlling for autoregression (b = .418, p < .001) and other variables in the model. As an ancillary analysis, we also tested whether the inclusion of visuals increased knowledge, specifically an effect of photos of microcephalic children or mosquitoes on knowledge about each, respectively. Our analysis found that the percentage of articles containing a photo did not affect specific knowledge (p > .05). In sum, only the total amount of coverage influenced knowledge about specific aspects.

Finally, H5 predicted that the amount of coverage will increase interpersonal discussions. Using the same model as in H1 (F(4, 1,095) = 6.34, p < .001), coverage amount was found to correlate with the number of discussions reported on the next day (b = .03, p < .001), controlling for autoregression (b = .70, p < .001) and other variables in the model.

Discussion

Faced with the emergence of new and unfamiliar health risks, people often seek non-medical sources for information, including the mass media (Ramírez et al., Citation2013). Mass media serve as “amplification stations” that spread organizational messages and increase awareness and knowledge among target populations. During this process, some aspects of the disease are highlighted while others are downplayed or ignored, a phenomena that can amplify or attenuate risk perceptions and risk-related behaviors (Kasperson & Kasperson, Citation1996). The inclusion or omission of specific aspects of a disease are affected by journalistic routines, such as an assessment of newsworthiness. Studies have found substantial differences between CDC communications during epidemics, and news coverage attest (Mebane, Temin, & Parvanta, Citation2003; Ophir, Citation2018). Although the amount of coverage differed over time and with respect to internal (ZIKV-related) and external (Rio Olympics) events, our study found that U.S. news media devoted considerable space and time to coverage of ZIKV. The globally-relevant major media event of the Olympics attracted the most media attention. Unsurprisingly, coverage peaked as the opening ceremonies of the games approached, and declined sharply as the event came to an end. Nevertheless, ZIKV was often mentioned only in passing during this time. The primary focus of most of the articles was on the games and athletes participating in them.

As expected, the coverage of specific aspects of the risk received more media attention than others, and those aspects were the ones hypothesized to meet traditional criteria of newsworthiness and to be more amenable to visual depiction. Specifically, the coverage of transmission through mosquitoes (1,857 articles) was substantially more extensive than that of sexual transmission (618) and the health threat of microcephaly (841). The important information that those infected with ZIKV- often show no symptoms was covered in only 358 articles.

An analysis of survey responses found that public knowledge about these aspects was consistent with the amount of coverage. People knew more about mosquitoes than microcephaly, less about sexual transmission, and least about the asymptomatic nature of Zika. While these findings are consistent with theories of journalism routines and newsworthiness values, additional research that focuses on journalists’ and editors’ decision- making processes is needed to better understand the incentives that would increase coverage of the underplayed aspects of the CDC’s Zika message—asymptomatic and sexual transmission. Importantly, by only looking at the content and without conducting interviews with journalists, we were unable to identify the reason for the differences in coverage. Nor can we reject alternative explanations, for example that the less intense coverage of sexual transmission could be the result of journalistic biases that tend to underrepresent issues perceived to be more relevant to females than males (Len-Ríos, Rodgers, Thorson, & Yoon, Citation2005; Ross & Carter, Citation2011). In this case, sexual transmission could be seen as more related to women, due to gendered biases in perceptions about health issues (Almeling & Waggoner, Citation2013; Levis & Westbrook, Citation2013; Thompson et al., Citation2017).

According to the social amplification of risk theory, journalists’ emphases and omissions are expected to influence public knowledge about these aspects. Despite the differences in amounts of coverage of various risk aspects of ZIKV, our analysis reveals that the amount of coverage of specific topics did not predict changes in knowledge. However, the total amount of coverage increased familiarity with the disease in general, and knowledge about microcephaly and mosquito-borne infections in particular. The total amount of coverage also increased interpersonal discussions. The increase in interpersonal discussion of health information that appeared in the media can increase the salience of a health topic and reduce risky behaviors and also enhance the agenda setting function of the coverage (Lewis et al., Citation2012; Rimal, Flora, & Schooler, Citation1999). Importantly, the small coefficients reported in the results section represent changes in the dependent variables with the increase of 10 articles per day. Of course, in reality, variations in coverage volume changed dramatically between days (see ), leading to bigger effects. These findings are consistent with prior research showing the importance of amount of exposure on the success of health campaigns (Hornik, Citation2002).

Although the importance and relevance of traditional mass news outlets have been the center of many academic and popular debates in recent decades (Tesler & Zaller, Citation2014), the rise of social media and the fragmentation of the media landscape have made it possible for selective exposure to drive ideological enclaving (Hart et al., Citation2009; Stroud, Citation2011), leading some scholars to anticipate a new era of minimal media effects (Bennett & Iyengar, Citation2008). An important caveat to our conclusions is that we analyzed the content of mass media outlets only and did not look into other sources such as social media activities. Alternative sources may influence knowledge and behavior as well. However, research has shown that audiences still get a substantial amount of information from traditional news outlets (Hindman, Citation2008). Moreover, the information people consume online is not very different from what appears in the mass media, a pattern attributable to inter-media agenda setting (Conway, Kenski, & Wang, Citation2015).

In addition, as explained in the methods section, due to the questionnaire’s breadth some of our constructs were measured using single items, a fact that may have increased statistical noise and limited the scope of measurement. For example, the interpersonal discussions item focused on discussion of “the effects of Zika”, thus excluding other facets of the behavior such as discussion of transmission paths. Moreover, in an attempt to fit the questionnaire to real time developments in the progression of the disease, we changed the wording of the question about sexual transmission to accommodate developments in new CDC guidelines. This decision allowed for timely assessments of public opinion and knowledge, but prevented us from using knowledge about sexual transmission in our time series analysis. Because of that limitation, we did not analyze the effect of coverage on knowledge about sexual transmission, and separated measures of knowledge for sexual transmission in general and sexual transmission from men. To be clear, all analyses presented in this manuscript were conducted only using items for which no changes in wording were made. Other studies might productively compare our findings from the mass media to data from other media sources, using different measures.

Our study suggests that the mass media remain an important vehicle for propagating health information, and that the amount of media coverage dedicated to a health risk can influence familiarity, knowledge and behaviors. However, the effects we found may be the result of direct effects of exposure, or indirect ones (i.e., media coverage may increase interpersonal discussion among viewers or social media activity that can lead to more familiarity among non-viewers). Future studies should look into the effects on the individual level to test whether highly-exposed individuals gained more knowledge than those with lower exposure rates. Further research should also examine the social media activity of the CDC (including the organization’s use of visuals, as their communications were not bounded by journalistic routines but nevertheless are constrained by the same challenges in depicting some phenomena) and the public during epidemics, and compare it to mass media coverage. We do expect, however, that due to inter-media agenda setting (See Conway et al., Citation2015), social media activity will include a vast amount of information directly shared from the mass media. Moreover, future individual-level analyses might examine whether audiences for different outlets acquired different levels or patterns of knowledge about risks. Additionally, future studies might look productively at the differences between laypersons’ and scientists’ knowledge about ZIKV, in terms of similarity and accuracy (Johnson, Citation1993; Sandman, Citation1987). Finally, because we had no good way to assess actual behaviors, we relied on self-reports.

Still, our aggregated-level analysis points to effects on the public at large with important implications for public health communicators. Institutions such as the CDC have developed complex and novel frameworks for the communication of risk information during crises (Veil et al., Citation2008). However, our study supports the argument that the success of these health campaigns and efforts still depends, in part, on cooperation and regular coverage on the part of traditional news media organizations. Our results also support CERC’s argument that the CDC’s and media’s roles are complementary (Reynolds & Seeger, Citation2014), with the function of the latter not limited to amplifying governmental messages. This finding suggests that when working with the media, CDC spokespersons and other sources should attempt to keep the general topic on the agenda (while emphasizing timely specific information of public health importance), in a way that may increase general familiarity and post-exposure information-seeking. Such secondary search for information may direct people to more specific information, either on official websites, through their doctors, or through other channels.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Kenneth Winneg and Lauren Elizabeth Hawkins for their help in designing and conducting the content analysis and survey, and to the coders who content analyzed news coverage: Brooke Reczka, Raquel Thalheimer, Anna Kanter and Jon Winneg. We also thank the editor and reviewers for their contribution to this manuscript.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. (Huffington Post was selected for inclusion because it includes a health section and because a late 2014 Pew survey found greater public awareness of it that Politco, Buzzfeed, or Slate) http://www.journalism.org/interactives/media-polarization/table/heard/) NPR was included because, with a total weekly listenship of 37.4 million in the fall of 2016, it was the only 24 hour a day national news radio outlet in the US with a sizeable audience (https://www.npr.org/about-npr/520273005/npr-ratings-at-all-time-high).

2. We used Chow F-tests to check for structural breaks in the time series of all variables involved in the analysis, and found a statistically significant break before the Olympics games. Therefore, commonly used stationarity tests such as Kwiatkowski–Phillips–Schmidt–Shin (KPSS) and Dickey–Fuller test (ADF) could not be used as they are highly sensitive to structural changes. We therefore rejected the presence of unit root using Phillips-Perron test.

References

- Aiken, A. R. A., Scott, J. G., Gomperts, R., Trussell, J., Worrell, M., & Aiken, C. E. (2016). Requests for abortion in Latin America related to concern about Zika virus exposure. New England Journal of Medicine, 375, 396–398. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1605389

- Allison, P. D. (2001). Missing data. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

- Almeling, R., & Waggoner, M. R. (2013). More and less than equal: How men factor in the reproductive equation. Gender & Society, 27, 821–842. doi:10.1177/0891243213484510

- Alter, A. (2017). Updating a chronicle of suffering: Author of ‘The hot zone’ tracks Ebola’s evolution. The New York Times. Retrieved December 21, 2017, from https://www.nytimes.com/2014/10/20/books/the-hot-zone-author-tracks-ebolas-evolution.html

- Anderson, K. B., Thomas, S. J., & Endy, T. P. (2016). The emergence of Zika virus: A narrative review. Annals of Internal Medicine, 165, 175–183. doi:10.7326/M16-0617

- Bennett, W. L., & Iyengar, S. (2008). A new era of minimal effects? The changing foundations of political communication. Journal of Communication, 58, 707–731. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.2008.00410.x

- Broutet, N., Krauer, F., Riesen, M., Khalakdina, A., Almiron, M., Aldighieri, S., … Dye, C. (2016). Zika virus as a cause of neurologic disorders. New England Journal of Medicine, 374, 1506–1509. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1602708

- Cao-Lormeau, V.-M., Blake, A., Mons, S., Lastère, S., Roche, C., Vanhomwegen, J., … Ghawché, F. (2016). Guillain-Barré syndrome outbreak associated with Zika virus infection in French Polynesia: A case-control study. The Lancet, 387, 1531–1539. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00562-6

- Cauchemez, S., Besnard, M., Bompard, P., Dub, T., Guillemette-Artur, P., Eyrolle-Guignot, D., … Mallet, H.-P. (2016). Association between Zika virus and microcephaly in French Polynesia, 2013–15: A retrospective study. The Lancet, 387, 2125–2132. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00651-6

- Chan, M. S., Winneg, K., Hawkins, L., Farhadloo, M., Jamieson, K. H., & Albarracín, D. (2018). Legacy and social media respectively influence risk perceptions and protective behaviors during emerging health threats: A multi-wave analysis of communications on Zika virus cases. Social Science & Medicine, 212, 50–59. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.07.007

- Chang, C. (2012). News coverage of health-related issues and its impacts on perceptions: Taiwan as an example. Health Communication, 27, 111–123. doi:10.1080/10410236.2011.569004

- Chau, J., Bonfiglioli, C., Chey, T., & Bauman, A. (2009). The Cinderella of public health news: Physical activity coverage in Australian newspapers, 1986-2006. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 33, 189–192. doi:10.1111/j.1753-6405.2009.00368.x

- Conway, B. A., Kenski, K., & Wang, D. (2015). The rise of Twitter in the political campaign: Searching for intermedia agenda-setting effects in the presidential primary. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 20, 363–380. doi:10.1111/jcc4.12124

- Coombs, T. W. (2009). Conceptualizing Crisis Communication. In R. L. Heath & D. H. O’Hair (Eds.), Handbook of risk and crisis communication (1st ed., pp. 99–118). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Covello, V. T., Peters, R. G., Wojtecki, J. G., & Hyde, R. C. (2001). Risk communication, the West Nile virus epidemic, and bioterrorism: Responding to the communication challenges posed by the intentional or unintentional release of a pathogen in an urban setting. Journal of Urban Health, 78, 382–391. doi:10.1093/jurban/78.2.382

- D’Angelo, P., & Kuypers, J. A. (2010). Introduction: Doing news framing analysis. In P. D’Angelo & J. A. Kuypers (Eds.), Doing news framing analysis: Empirical and theoretical perspectives (pp. 1–13). New York, NY: Routledge.

- D’Ortenzio, E., Matheron, S., de Lamballerie, X., Hubert, B., Piorkowski, G., Maquart, M., … Leparc-Goffart, I. (2016). Evidence of sexual transmission of Zika virus. New England Journal of Medicine, 374, 2195–2198. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1604449

- Dayan, D., & Katz, E. (1994). Media events. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Dunlop, S., Cotter, T., Perez, D., & Wakefield, M. (2013). Televised antismoking advertising: Effects of level and duration of exposure. American Journal of Public Health, 103, e66–e73. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2012.301079

- Ekblad, N. (2013). Newsworthiness in science : A content analysis of science news in swedish prime time television 2009-2011. Retrieved from http://www.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2:630215

- Entman, R. M. (1993). Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. Journal of Communication, 43, 51–58. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.1993.tb01304.x

- França, G. V. A., Schuler-Faccini, L., Oliveira, W. K., Henriques, C. M. P., Carmo, E. H., Pedi, V. D., … Victora, C. G. (2016). Congenital Zika virus syndrome in Brazil: A case series of the first 1501 livebirths with complete investigation. The Lancet, 388, 891–897. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30902-3

- Galtung, J., & Ruge, M. H. (1965). The structure of foreign news: The presentation of the Congo, Cuba and Cyprus crises in four Norwegian newspapers. Journal of Peace Research, 2, 64–90. doi:10.1177/002234336500200104

- Gans, H. J. (1979). Deciding what’s news: A study of CBS evening news, NBC nightly news, Newsweek and Time. New York, NY: Vintage Books.

- Gatherer, D., & Kohl, A. (2016). Zika virus: A previously slow pandemic spreads rapidly through the Americas. Journal of General Virology, 97, 269–273. doi:10.1099/jgv.0.000381

- Glowacki, E. M., Lazard, A. J., Wilcox, G. B., Mackert, M., & Bernhardt, J. M. (2016). Identifying the public’s concerns and the centers for disease control and prevention’s reactions during a health crisis: An analysis of a Zika live Twitter chat. American Journal of Infection Control, 44, 1709–1711. doi:10.1016/j.ajic.2016.05.025

- Golan, G. (2006). Inter-media agenda setting and global news coverage. Journalism Studies, 7, 323–333. doi:10.1080/14616700500533643

- Golding, P., & Elliott, P. (1979). Making the News. London, UK: Longman.

- Green, J. (1985). Media sensationalisation and science. In T. Shinn & R. D. Whitley (Eds.), Expository science: Forms and functions of popularisation (pp. 139–161). Dordrecht, The Netherlands: D. Reidel Publishing Company. doi:10.1007/978-94-009-5239-3_7

- Greenberg, M. R., Sachsman, D. B., Sandman, P. M., & Salomone, K. L. (1989). Network evening news coverage of environmental risk. Risk Analysis, 9, 119–126. doi:10.1111/j.1539-6924.1989.tb01227.x

- Hart, W., Albarracín, D., Eagly, A. H., Brechan, I., Lindberg, M. J., & Merrill, L. (2009). Feeling validated versus being correct: A meta-analysis of selective exposure to information. Psychological Bulletin, 135, 555–588. doi:10.1037/a0015701

- Hennessey, M., Fischer, M., & Staples, J. E. (2016). Zika virus spreads to new areas — Region of the Americas, May 2015–January 2016. American Journal of Transplantation, 16, 1031–1034. doi:10.1111/ajt.13743

- Hewlett, B. S., & Hewlett, B. L. (2007). Ebola, culture and politics: The anthropology of an emerging disease. Belmont, CA: Thomson Wadsworth.

- Hindman, M. (2008). The myth of digital democracy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Hornik, R. C. (2002). Exposure: Theory and evidence about all the ways it matters. Social Marketing Quarterly, 8, 31–37. doi:10.1080/15245000214135

- Joffe, H. (2008). The power of visual material: Persuasion, emotion and identification. Diogenes, 55, 84–93. doi:10.1177/0392192107087919

- Johnson, B. (1993). Advancing understanding of knowledge’s role in lay risk perception. RISK: Health, Safety & Environment (1990-2002), 4. Retrieved from http://scholars.unh.edu/risk/vol4/iss3/3

- Jones, K. O., Denham, B. E., & Springston, J. K. (2006). Effects of mass and interpersonal communication on breast cancer screening: Advancing agenda-setting theory in health contexts. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 34, 94–113. doi:10.1080/00909880500420242

- Kasperson, R. E., & Kasperson, J. X. (1996). The social amplification and attenuation of risk. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 545, 95–105. doi:10.1177/0002716296545001010

- Kasperson, R. E., Renn, O., Slovic, P., Brown, H. S., Emel, J., Goble, R., … Ratick, S. (1988). The social amplification of risk: A conceptual framework. Risk Analysis, 8, 177–187. doi:10.1111/j.1539-6924.1988.tb01168.x

- Kennedy, M. G., O’Leary, A., Beck, V., Pollard, K., & Simpson, P. (2004). Increases in calls to the CDC National STD and AIDS Hotline following AIDS-related episodes in a soap opera. Journal of Communication, 54, 287–301. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.2004.tb02629.x

- Lang, A. (2000). The limited capacity model of mediated message processing. Journal of Communication, 50, 46–70. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.2000.tb02833.x

- Lawrence, R., & Mueller, D. (2003). School shootings and the man-bites-dog criterion of newsworthiness. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, 1, 330–345. doi:10.1177/1541204003255842

- Len-Ríos, M. E., Rodgers, S., Thorson, E., & Yoon, D. (2005). Representation of women in news and photos: Comparing content to perceptions. Journal of Communication, 55, 152–168. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.2005.tb02664.x

- Levis, D. M., & Westbrook, K. (2013). A content analysis of preconception health education materials: Characteristics, strategies, and clinical-behavioral components. American Journal of Health Promotion, 27, S36–S42. doi:10.4278/ajhp.120113-QUAL-19

- Lewis, N. (2017). Information seeking and scanning. In P. Rössler, C. A. Hoffner, & L. van Zoonen (Eds.), The international encyclopedia of media effects (pp. 1–10). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. doi:10.1002/9781118783764.wbieme0156

- Lewis, N., Martinez, L. S., Freres, D. R., Schwartz, J. S., Armstrong, K., Gray, S. W., … Hornik, R. C. (2012). Seeking cancer-related information from media and family/friends increases fruit and vegetable consumption among cancer patients. Health Communication, 27, 380–388. doi:10.1080/10410236.2011.586990

- Lundgren, R. E., & McMakin, A. H. (2013). Risk communication: A handbook for communicating environmental, safety, and health risks. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

- Massad, E., Coutinho, F. A. B., & Wilder-Smith, A. (2016). Is Zika a substantial risk for visitors to the Rio de Janeiro Olympic games? The Lancet, 388, 25. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30842-X

- Mazur, A. (1984). The journalists and technology: Reporting about love canal and Three Mile Island. Minerva, 22(1), 45–66. doi:10.1007/BF02207556

- McCombs, M. E., & Shaw, D. L. (1972). The agenda-setting function of mass media. The Public Opinion Quarterly, 36, 176–187. doi:10.1086/267990

- McNeil, D. G. (2016). Zika: The emerging epidemic. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company.

- Mebane, F., Temin, S., & Parvanta, C. F. (2003). Communicating anthrax in 2001: A comparison of CDC information and print media accounts. Journal of Health Communication, 8, 50–82. doi:10.1080/713851970

- Mlakar, J., Korva, M., Tul, N., Popović, M., Poljšak-Prijatelj, M., Mraz, J., … Avšič Županc, T. (2016). Zika virus associated with microcephaly. New England Journal of Medicine, 374, 951–958. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1600651

- Morgan, M., Fischhoff, B., Bostrom, A., Lave, L., & Atman, C. (1992). Communicating risk to the public. Environmental Science & Technology, 26, 2048–2056. doi:10.1021/es00035a606

- Moyer-Gusé, E., Chung, A. H., & Jain, P. (2011). Identification with characters and discussion of taboo topics after exposure to an entertainment narrative about sexual health. Journal of Communication, 61, 387–406. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.2011.01551.x

- Niederdeppe, J., Bu, Q. L., Borah, P., Kindig, D. A., & Robert, S. A. (2008). Message design strategies to raise public awareness of social determinants of health and population health disparities. The Milbank Quarterly, 86, 481–513. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0009.2008.00530.x

- O’Neill, D., & Harcup, T. (2009). News values and selectivity. In K. Wahl-Jorgensen & T. Hanitzsch (Eds.), The handbook of journalism studies (pp. 161–174). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Ophir, Y. (2018). Coverage of epidemics in American newspapers through the lens of the crisis and emergency risk communication framework. Health Security, 16, 147–157. doi:10.1089/hs.2017.0106

- Oster, A. M., Brooks, J. T., Stryker, J. E., Kachur, R. E., Mean, P., Pesik, N. T., & Peterson, L. R. (2016). Interim guidelines for prevention of sexual transmission of Zika virus—United States, 2016. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 65, 1–2. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6505e1er

- Pellechia, M. G. (1997). Trends in science coverage: A content analysis of three US newspapers. Public Understanding of Science, 6, 49–68. doi:10.1088/0963-6625/6/1/004

- Petersen, E. E., Meaney-Delman, D., Neblett-Fanfair, R., Havers, F., Oduyebo, T., Hills, S. L., … Brooks, J. T. (2016). Update: Interim guidance for preconception counseling and prevention of sexual transmission of Zika virus for persons with possible Zika virus exposure - United States, September 2016. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 65, 1077–1081. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6539e1

- Petts, J., Draper, H., Ives, J., & Damrey, S. (2010). Risk communication and pandemic influenza. In P. Bennett, K. Calman, S. Curtis, & D. Fischbacher-Smith (Eds.), Risk communication and public health (pp. 81–96). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Pidgeon, N., & Henwood, K. (2010). The social amplification of risk framework (SARF): Theory, critiques, and policy implications. In P. Bennett, K. Calman, S. Curtis, & D. Fischbacher-Smith (Eds.), Risk communication and public health (pp. 53–67). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Pokharel, S. (2015). An examination of moral panic in the British press coverage of the 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Cardiff University, Cardiff, Wales..

- Price, M., & Dayan, D. (2009). Owning the Olympics: Narratives of the new China. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

- Ramírez, A. S., Freres, D., Martinez, L. S., Lewis, N., Bourgoin, A., Kelly, B. J., … Hornik, R. C. (2013). Information seeking from media and family/friends increases the likelihood of engaging in healthy lifestyle behaviors. Journal of Health Communication, 18, 527–542. doi:10.1080/10810730.2012.743632

- Rasmussen, S. A., Jamieson, D. J., Honein, M. A., & Petersen, L. R. (2016). Zika virus and birth defects — Reviewing the evidence for causality. New England Journal of Medicine, 374, 1981–1987. doi:10.1056/NEJMsr1604338

- Renn, O. (1991). Risk communication and the social amplification of risk. In R. E. Kasperson & P. J. M. Stallen (Eds.), Communicating risks to the public: Technology, risk, and society (pp. 287–324). Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers. doi:10.1007/978-94-009-1952-5_14

- Reynolds, B., & Seeger, M. W. (2005). Crisis and emergency risk communication as an integrative model. Journal of Health Communication, 10, 43–55. doi:10.1080/10810730590904571

- Reynolds, B., & Seeger, M. W. (2014). Crisis and emergency risk communication, 2014 edn. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved from https://emergency.cdc.gov/cerc/resources/pdf/cerc_2014edition.pdf

- Rimal, R. N., Flora, J. A., & Schooler, C. (1999). Achieving improvements in overall health orientation: Effects of campaign exposure, information seeking, and health media use. Communication Research, 26, 322–348. doi:10.1177/009365099026003003

- Rosenthal, U., Boin, A., & Comfort, L. K. (2001). The changing world of crises and crisis management. In U. Rosenthal, A. Boin, & L. K. Comfort (Eds.), Managing crises: Threats, dilemmas, opportunities (pp. 5–27). Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas Publisher.

- Ross, K., & Carter, C. (2011). Women and news: A long and winding road. Media, Culture & Society, 33, 1148–1165. doi:10.1177/0163443711418272

- Rowan, K. E. (1991). Goals, obstacles, and strategies in risk communication: A problem‐solving approach to improving communication about risks. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 19, 300–329. doi:10.1080/00909889109365311

- Sandman, P. M. (1987). Risk communication: Facing public outrage. EPA Journal, 13, 21.

- Sandman, P. M. (1993). Responding to community outrage: Strategies for effective risk communication. Fairfax, VA: American Industrial Hygiene Association.

- Shih, T.-J., Wijaya, R., & Brossard, D. (2008). Media coverage of public health epidemics: Linking framing and issue attention cycle toward an integrated theory of print news coverage of epidemics. Mass Communication and Society, 11, 141–160. doi:10.1080/15205430701668121

- Shoemaker, P. J., Danielian, L. H., & Brendlinger, N. (1991). Deviant acts, risky business and U.S. interests: The newsworthiness of world events. Journalism Quarterly, 68, 781–795. doi:10.1177/107769909106800419

- Shoemaker, P. J., & Reese, S. D. (1996). Mediating the message: Theories of influence on mass media content (2nd ed.). White Plains, NY: Longman.

- Southwell, B. G., Dolina, S., Jimenez-Magdaleno, K., Squiers, L. B., & Kelly, B. J. (2016). Zika virus–related news coverage and online behavior, United States, Guatemala, and Brazil. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 22, 1320–1321. doi:10.3201/eid2207.160415

- Srinivasan, R. (2010). Swine flu: Is panic the key to successful modern health policy? Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 103, 340–343. doi:10.1258/jrsm.2010.100118

- Stroud, N. J. (2011). Niche news: The politics of news choice. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Stryker, J. E. (2002). Reporting medical information: Effects of press releases and newsworthiness on medical journal articles’ visibility in the news media. Preventive Medicine, 35, 519–530. doi:10.1006/pmed.2002.1102

- Tang, H., Hammack, C., Ogden, S. C., Wen, Z., Qian, X., Li, Y., … Ming, G. (2016). Zika virus infects human cortical neural progenitors and attenuates their growth. Cell Stem Cell, 18, 587–590. doi:10.1016/j.stem.2016.02.016

- Tesler, M., & Zaller, J. (2014). The power of political communication. In K. H. Jamieson, D. Kahan, & D. A. Scheufele (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of political communication (pp. 69–84). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199793471.013.003

- Thompson, E. L., Vázquez-Otero, C., Vamos, C. A., Marhefka, S. L., Kline, N. S., & Daley, E. M. (2017). Rethinking preconception care: A critical, women’s health perspective. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 21, 1147–1155. doi:10.1007/s10995-016-2213-8

- Tuchman, G. (1973). Making news by doing work: Routinizing the unexpected. American Journal of Sociology, 79, 110–131. doi:10.1086/225510

- Vasterman, P., Scholten, O., & Ruigrok, N. (2008). A model for evaluating risk reporting: The case of UMTS and fine particles. European Journal of Communication, 23, 319–341. doi:10.1177/0267323108092538

- Veil, S. R., Reynolds, B., Sellnow, T. L., & Seeger, M. W. (2008). CERC as a theoretical framework for research and practice. Health Promotion Practice, 9, 26S–34S. doi:10.1177/1524839908322113

- Wanta, W., & Wu, Y.-C. (1992). Interpersonal communication and the agenda-setting process. Journalism Quarterly, 69, 847–855. doi:10.1177/107769909206900405