ABSTRACT

Time is quite possibly a physician’s most valuable asset, yet the tendency of almost all physicians is to be overly committed. How do we slowdown and make a meaningful difference? Virtual visits provide a new way to share and care without sacrificing the important nuances of face-to-face communication. When the Cleveland Clinic expanded our Distance Health capabilities in 2017 using virtual visits, we began a successful journey which provides cancer patients and their caregivers a new type of expert, unrushed cancer care access. This essay describes our current process for providing virtual visit access, preparing prior to the visit, keeping the visit as informative a possible, and closing the visit with a “distance health encounter” in the electronic medical record coupled with a summary and additional information via email.

Cancer care has become complicated and is scary in many ways.

The diagnosis of cancer heralds the possibility of an early death. Unfamiliar environments (e.g., hospitals and clinics) and high stakes may hijack emotions and can result in anxiety and poor ability to not only understand information but also prevent effective action and reactions. Surgery and/or radiation are nearly always needed for durable control of solid tumors, but explaining and learning how and when these options are chosen and then done with acceptable short and long-term side effects can take a lot of time and patience. Locating where the cancer is or is not – or will “pop up” – is usually ascertained by a variety of “scans” including CT scans and/or MRI scans, bone scans, PET-CT scans and other imaging modalities such as ultrasound, chest x-rays and “plain” x-rays. Although written reports are routinely made available to patients and caregivers via MyChart or other electronic portals, these are often difficult for the non-expert and sometimes experts to interpret. Words provide not just an incomplete picture – but NO PICTURE! It is like having a huge legend, but no accompanying illustrations; this inadequate pictorial representation without a visual correlative of the medical jargon can make a cancer situation seem much worse than it really is. The end result is anxiety and worry about problems which may never happen.

How does a family develop a positive and organized approach amid a flood of detailed, yet hopelessly inadequate, information? We believe in therapeutic alliances in which physicians are responsive to patients’ unique life circumstances and involve families in information-gathering and sharing, goal-setting, and decision-making (see also Anderson & Kaye, Citation2009). Therapeutic alliances require unhurried visits, especially when patients are facing rare diagnoses and complicated treatment protocols. Yet, time is quite possibly a physician’s most valuable asset, and the tendency of almost all physicians is to be overly committed. How do we slowdown and make a meaningful difference? Virtual visits provide a new way to share and care without sacrificing the important nuances of face-to-face communication. When the Cleveland Clinic expanded its Distance Health capabilities in 2017 using virtual visits, we began a successful journey which provides patients and their caregivers a new type of expert, unrushed cancer care access. This essay describes our current process for providing virtual visit access, preparing prior to the visit, keeping the visit as informative as possible, and closing the visit with a “distance health encounter” in the electronic medical record (EMR) coupled with a summary and additional information via email.

Virtual visit access and preparation

The Cleveland Clinic initiated virtual visits in part to increase access to its specialists without over-burdening staff or requiring unnecessary travel and expense for patients. The authors provide expert consultation in virtual visits with patients, families, and/or the primary oncologist or other member of the patient’s health-care team (e.g., surgeon, palliative care specialists). Sometimes the visits occur at the initial time of diagnosis and in other cases when problems arise (e.g., uncontrolled pain) or when patients are faced with a critical treatment decision. The video format for our virtual visits coupled with email follow-ups have facilitated the exchange of predictable and high quality verbal and written information with families of children, adolescents and young adults with osteosarcoma, Ewing sarcoma, desmoplastic small round cell tumor (DSRCT), other sarcomas, and rare cancers as well survivors and chronic graft-versus-host disease (GVHD).

A satisfying part of the virtual visits has been the ability to discuss the many opportunities to improve patients’ overall health and offer tips to forge better therapeutic alliances. As the first author has noted in earlier work, the goal of therapeutic alliances should be “to achieve the best possible outcome. This may or may not be survival” (Anderson & Kaye, Citation2009, p. 775). As our virtual visit demand grew, initial chaos associated with seemingly random phone inquiries and emails for expertise has been replaced with orderly, relaxed, and really quite fun 40 to 60-min virtual visits. A defining moment in the development of our virtual visits initiative was to provide reliable, easy access two mornings each week.

How are virtual visits initiated and accessed? Once the Cleveland Clinic receives an email or phone inquiry, a physician or administrative assistant follows up with an email with instructions & attachments for:

Obtaining a Cleveland Clinic Medical Record Number (MRN);

Sending a brief chronological summary of diagnosis and important cancer care to this point (if not already done with initial inquiry email);

Uploading a CD of images by the patient (DICOM format provided by radiology) or sending a CD for us to upload to allow us to view images in the electronic medical record (EMR). Our EMR is EPIC which has the advantage of shared EMR information with other centers using EPIC;

Downloading apps and software for video viewing of the virtual visit on a tablet or smartphone (like FaceTime) or a computer (like Skype) but using HIPPA compliant American Well App and/or software to provide the Cleveland Clinic Express Care audio and video link.

Usually, before the virtual visit, the first author will measure tumors and metastases and make a powerpoint to share with participants. Seeing is believing and increases physician, patient, and caregiver understanding. Visually knowing what a patient is up against can be empowering and very helpful in guidance and making decisions about local control modalities, how to follow the effectiveness of therapy, and when to get future scans. It is often the trend (“connecting the dots”) that is important in knowing treatment is working- or not. Since sending text reports of questions without visual data is often inadequate, getting scans uploaded for review may be an easy, but necessary step for getting an appointment.

Facilitating virtual visits

Providing information in an unrushed manner using pictures (power points of scans), summaries with “opportunities to improve health” and review of these options and ending with an action plan is our goal of most virtual visits. These virtual visits are like a fireside chat using FaceTime or Skype but with HIPPA compliant software. As Anderson & Kaye noted (Citation2009), “The development of a therapeutic alliance in a sometimes scary medical environment is a challenging task. Patients’ lives are disrupted by a cancer diagnosis” (p. 778). When done in the privacy, familiarity, and comfort of one’s own home, these visits can be life-changing. On occasion, we do connect with patients and family members in clinical settings. Across all settings, we seek to demystify foreign terminology and help patients manage uncertainty and fear. For younger children, we often also try to include them in the visit, too.

For our equivalent of a surgeon’s pre-op checklist, we create a draft “One Page Summary”. This is an MS Word document that is edited during the virtual visit and then emailed to the patient and family after the end of the visit. What are the components of a typical One Page Summary? Summaries are organized in three main sections that include key aspects of patients’ treatment history and problem list coupled with personal information about their broader life. These one-page summaries are edited during the visit with the patient and family to avoid “analysis paralysis,” avoid battle fatigue, and develop a comprehensive strategy of care (Anderson & Kaye, Citation2009).

The first section includes names, contact information, and demographics of the patient, family, and members of the cancer care team (e.g. medical oncologist, surgeon, radiation oncologist) as well as current height, weight, body surface area (BSA) and body mass index (BMI). We often will also place a family picture and pictures of their doctors to help us visualize who we are talking about and encouraging to “make it better.” As noted by Anderson and Kaye (Citation2009), “The photos included in summaries are visual representations of patients’ defining moments in significant scenes of their lives,” noted Anderson and Kaye (Citation2009), “and remind everyone that life moves on in the midst of cancer and its treatment” (p. 778). Personal photos of patients and families are reminders that people are more than their disease – their life stories have been disrupted, and we are part of the team helping them to re-imagine the next chapters.

The second section is a brief chronologic summary (i.e. Past Medical History). It is helpful to know at a glance where you have been to know the circumstances of “how did we get here”? This section ends with the current date of virtual visit and major questions and concerns that are to be addressed during the visit.

The final section is titled “Opportunities to Improve Health.” This label was chosen because it is not just a problem list of what is bad, but rather a list of ways to strive towards better health. Sometimes we use the analogy of “running up the score” to have the best chances of much less toxicity and achieving better than expected outcomes in a variety of ways that affect physical and mental health as well as relationships. Opportunities to improve health helps stimulate discussion and catalyzes positive action in six areas for solid tumor cancer patients including:

(1) Local control of sites of cancer.

We identify site of where the cancer started (primary tumor) as well as known metastases, and possible areas of metastases for that kind of cancer. Then, we discuss and review indications, risks, and alternatives of various options to control these with “physical” means. Local control modalities may include: a) surgery, b) radiation, c) heating tumors (for example, radiofrequency ablation or electroporation) or d) freezing tumors (cryoablation). Location and experience help guide an analysis of not only standard and alternate best options for durable control without relapse(s), but also how to get this done with rapid healing, best function, and the fewest short and long-term side effects.

(2) Chemotherapy: medical means reducing spread of cancer using drugs.

Anti-cancer drugs (also known as chemotherapy agents) are often used to reduce cancer that is seen on scans as well as probable, but unseen metastases (i.e., “micro-metastatic disease”). For each variety of cancer, there are not only recipes of agents and schedules (i.e., regimens composed of cycles of chemotherapy every 1–4 weeks), but also information on how to use a regimen most effectively with fewest side effects. This is also called improving the therapeutic index. Additional options in case different anti-cancer agents are needed because of toxicity or lack of efficacy are also detailed. In this section, some clinical trials the patient may want to be aware of and best circumstances to enter such a trial are discussed. We provide the ClincalTrials.gov number and sometimes even a pdf of this information if this is high on the list of current or future things to do.

(3) Scans and other means of knowing therapy is beneficial.

We show scans that can be done to get the most information with the least effort as well as when to get the next scans and how to interpret information and whether another virtual visit may be needed to help interpret results and make plans (e.g., measurement of metastases and comparison to previous scans to interpret trends of better vs worse, same, and/or mixed results). If blood tests are useful (e.g. tumor markers) when to get these are also reviewed and dates are detailed on the summary, too.

(4) Anticipation and reduction of side effects.

This is an often unappreciated part of the art of oncology which takes time & effort but can be forgotten unless the oncology specialist is organized and asks “what could be improved?” Making quality of life better should be an iterative process to improve every cycle of chemotherapy and healing from cancer therapy. Many things are discussed including ways to improve nutrition and maintain strength and muscle mass to reduce fatigue and promote healing; reduce nausea; anticipate and ameliorate side effects such as mouth sores, kidney or liver problems; monitor lung and heart function; and prevent infection.

(5) Social and quality of life (QOL) issues.

Topics in this section include school or individualized educational plans (IEP), work and future employment; family caregivers and avoiding caregiver fatigue; life plans (e.g. “what do you want to be when you grow up?”); and pleasant things to look forward to (e.g., make-a-wish, graduation, vacation, family events); resources for self-expression (Art, music, and writing); guidance on how to organize caregivers and friends & family (who want to help but may need guidance); mentoring; and reducing financial toxicity. We HIGHLY recommend the lifeextraordinary.org website (www.liveextra.org), a very useful resource for communicating with family and friends (i.e., sharing your story); having a calendar to assign or volunteer for tasks; and also crowdfunding for unanticipated expenses (i.e., the financial toxicity of cancer treatment). The fourth angel program (www.4thangel.org), and for osteosarcoma patients the Make It Better Agents website (www.MIBagents.org) can provide information and mentoring opportunities. In short, this section of the summary provides critical information about social support resources available.

Finally, suggested reading and resources for difficult discussions regarding advance directives and end of life care are shared for those with metastatic disease and/or poor prognosis (Dr. Atul Gawande’s “Being Mortal” and Dr. Mary Neal’s “7 Lessons from Heaven”). If the end of life is a topic of discussion, a one-page handout with some bullet point list of common questions is sometimes provided, too. Finally, resources that may be accessed to make both quantity and quality of life (QOL) better are suggested including a psychologist, social worker, and/or child family life specialist for coping skill improvement(s); art and music therapy for fun, meaning, and self-expression; and physical therapy. Not uncommonly, we may discuss how to think about and show gratitude including giving flowers; this simple act always makes people smile.

(6) Follow-up and what is next.

The last opportunity to improve health is a short list of suggested follow-up items (with dates if known) to get out of “analysis paralysis” and to catalyze constructive action. This helps patients, caregivers, and the person doing the virtual visit to realize what has been accomplished in a short session and provides a green light for “making it better than expected.” This closing component of how to continue to strive towards better long-term health and better than expected outcomes is ALWAYS reviewed in order to provide a strong ending for comprehensive and meaningful visit.

Documentation and a facilitation of what is next

The summary, images, and articles used to support opportunities to improve health are then used to generate a “distance health encounter” in the EMR. This encounter can be seen in EPIC Care Everywhere and for reference if the patient comes for additional face to face consultations and/or future care coordination. Because it is very difficult for caregivers (doctors and families alike) to remember detailed information that is needed for life-changing decisions and back-up plans concerning the many bumps in the road, roadblocks, and forks in the road of a cancer journey, a copy of the edited summary (done during the visit), power points or pdf of images, article pdf, and other information is then emailed to the family. If there is a follow-up face to face visit, we also strive to provide even more information on a flash drive. With permission, we often copy the pediatric or medical oncologist, surgeon, or radiation oncologist on a secure email with summary and images as attachments so the team can more easily take positive steps in an orderly and thoughtful manner. Ideally, this communication helps the patient and family caregivers to be less like sheep and more like experienced horses in the traces or Canadian geese flying in a V, encouraging and helping each other to become eclectic and effective in assisting and encouraging each other.

Virtual visit demographics and social media

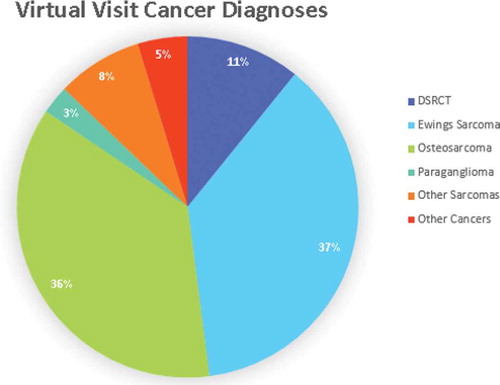

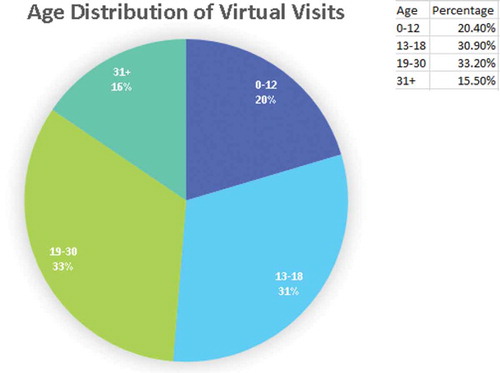

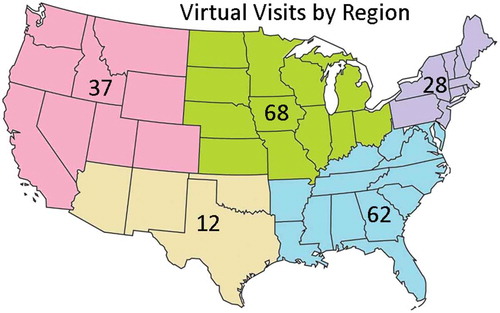

In 2017 we did 98 virtual visits; in 2018 there were 125 virtual visits. depicts which regions of the US are represented; we are also able to do virtual visits for Canada, too. depicts cancer diagnoses of our virtual visit patients which reflects referral practice and clinical trial availability of the first author. shows age distribution: about two-thirds of patients are between the ages of 13 and 30, the peak age of osteosarcoma and Ewing sarcoma. These data confirm we are providing an increasingly valuable and useful resource for many families with cancer in North America. Often when we ask, “How did you learn about us at Cleveland Clinic?”, we learn that our reputation for easy access and being knowledgeable and helpful is often shared on social media by patients with similar diagnoses such as the Facebook Ewing sarcoma, osteosarcoma, desmoplastic small round cell tumor (DSRCT), rhabdomyosarcoma groups, the Make It Better Agents and ACOR websites in osteosarcoma and Ewing sarcoma, or from other patients at their medical center. This positive experience of sharing and caring using the internet has indeed made access to our expertise easier and helps us catalyze an overall improved experience during and after cancer treatment possible for many families. We indeed strive to “Make It Better.”

Figure 1. Virtual visits are possible for both the USA and Canada. The figure depicts USA data 2017–2018 data for Cleveland Clinic Pediatric Hematology/Oncology/BMT.

Lessons learned go both ways

Others have shared that virtual visits are not only convenient but also may have many advantages and can improve health care in a variety of ways from post-op visits to specialized care (Chen, Citation2016; Costello et al., Citation2017; Finkelstein et al., Citationin press; Healy et al., Citationin press; Nochomovitz & Sharma, Citation2018; Papadakos et al., Citation2017; Rosenzweig & Baum, Citation2013; Shaw et al., Citation2018; Watanabe et al., Citation2013). Our visits have focused on a variety of rare cancers in young people and offer a glimpse about how shared knowledge can improve care. Our learning from virtual visits has been bidirectional; about 1/7 will request another virtual visit within 1 year. These highly motivated and “expert families” have also improved our knowledge base and network about what is available for other patients, too. Indeed, the sharing of meaningful narratives, stories, and lessons learned can help pay it forward for many cancer patients. Together, we can strive to improve health outcomes and as more patients become statistical outliers, we envision a sustaining mutually gratifying educational experience for all. We are very grateful for the vision, infrastructure, and opportunities Cleveland Clinic has provided to make these North American virtual visits possible.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the superlative and kind efforts of Doretha Pendleton for organizing (uploading scans, etc.) and scheduling virtual visits, Jasmine Boutros for help with demographic data, and Peggy Bird for terrific training and support not only in the start-up phase but invaluable assistance as the Cleveland Clinic’s Virtual Visit software and procedures continuously improved and became better and better!

References

- Anderson, P., & Kaye, L. (2009). The therapeutic alliance: Adapting to the unthinkable with better information. Health Communication, 24, 775–778. doi:10.1080/10410230903321004

- Chen, B. L. (2016). The new issue of social media in education and health behavior change - virtual visit of tele-nursing. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics, 225, 625–626.

- Costello, A. G., Nugent, B. D., Conover, N., Moore, A., Dempsey, K., & Tersak, J. M. (2017). Shared care of childhood cancer survivors: A telemedicine feasibility study. Journal of Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology, 6(4), 535–541. doi:10.1089/jayao.2017.0013

- Finkelstein, J. B., Cahill, D., Kurtz, M. P., Campbell, J., Schumann, C., Varda, B. K., … Estrada, C. R., Jr. (in press). The use of telemedicine for the postoperative urologic care of children: Results of a pilot program. The Journal of Urology. doi:10.1097/JU.0000000000000109

- Healy, P., McCrone, L., Tully, R., Flannery, E., Flynn, A., Cahir, C., … Walsh, T. (in press). Virtual outpatient clinic as an alternative to an actual clinic visit after surgical discharge: A randomised controlled trial. BMJ Quality & Safety, 28(1), 24–31. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2018-008171

- Nochomovitz, M., & Sharma, R. (2018). Is it time for a new medical specialty? The medical virtualist. JAMA, 319(5), 437–438. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.17094

- Papadakos, J., Trang, A., Cyr, A. B., Abdelmutti, N., Giuliani, M. E., Snow, M., … Wiljer, D. (2017). Deconstructing cancer patient information seeking in a consumer health library toward developing a virtual information consult for cancer patients and their caregivers: A qualitative, instrumental case study. JMIR Cancer, 3(1), e6. doi:10.2196/cancer.6933

- Rosenzweig, R., & Baum, N. (2013). The virtual doctor visit. The Journal of Medical Practice Management, 29(3), 195–198.

- Shaw, S., Wherton, J., Vijayaraghavan, S., Morris, J., Bhattacharya, S., Hanson, P., … Greenhalgh, T. (2018). Advantages and limitations of virtual online consultations in a NHS acute trust: The VOCAL mixed-methods study Health Services and Delivery Research (book). England, UK: Southampton.

- Watanabe, S. M., Fairchild, A., Pituskin, E., Borgersen, P., Hanson, J., & Fassbender, K. (2013). Improving access to specialist multidisciplinary palliative care consultation for rural cancer patients by videoconferencing: Report of a pilot project. Supportive Care in Cancer, 21(4), 1201–1207. doi:10.1007/s00520-012-1649-7