ABSTRACT

This study contributes to understanding medicalization on social media, by using Conrad’s concept of medicalization as a theoretical framework to explore the conversation about Orthorexia Nervosa (ON) on Twitter. The aim of this mixed-methods study was twofold: the quantitative component aimed to provide descriptive information on the type of tweets and users, as well as on the network structure of the ON-related conversation on Twitter, while the qualitative component aimed to explore how the medicalization of ON unfolds on Twitter by performing a thematic analysis of original tweets about ON. Quantitative descriptive findings show that the most popular hashtags associated with orthorexia include #rdchat, #psychology and #doctors, which hints to a link between discourses around ON and the medical profession. Among the most active, prominent and visible users are news accounts, a registered dietitian, a researcher, a professor and an editor. Qualitative thematic analysis shed light on the discursive process of medicalization. Some users bring about medicalization by approaching ON as a medical entity; in contrast, other users resist medicalization by describing ON as a social phenomenon. A discursive struggle emerges, where certain individuals feel confused around what constitutes ON. This leads to stigmatization of non-traditional diets like veganism, which in turn triggers complaints regarding over-medicalization. As the first Twitter investigation on ON, this study serves the purpose of providing insights into how an emerging disorder develops in society in a time of social media.

Over the past decades, scholars have increasingly turned their attention to Orthorexia Nervosa (ON), an emergent disordered eating pattern. ON can be described as a pathological eating practice deriving from an intensification of the pursuit of health, which results in an obsession with healthy eating (Bratman, Citation2017). People suffering from ON can harm themselves physiologically, psychologically and socially by prioritizing the consumption of food believed to be healthy over other important areas of their lives (Bratman, Citation2017). For example, people spend excessive time obsessively thinking about, buying and preparing healthy foods, which causes social isolation and psychological distress.

In 1997 Steven Bratman described ON in the Yoga Journal (Bratman, Citation1997). Although Bratman did not intend to propose a new eating disorder diagnosis (Bratman, Citation1997), the term attracted the attention of a number of scholars, who have since acknowledged the danger of the phenomenon and conducted scientific studies on it. Despite an increase in scientific publications since the beginning of the 2000s (Cuzzolaro & Donini, Citation2016), the scope of the studies published is limited (Missbach & Barthels, Citation2017).

Overall, there is a lack of medical knowledge and medical consensus around ON. First, scholars describe ON in different ways. As such, a shared understanding of the phenomenon is missing (Cena et al., Citation2019). Second, a set of formally recognized diagnostic criteria for ON has yet to be developed (Cena et al., Citation2019). Third, different diagnostic tools, based on slightly different interpretations of ON, are used to estimate ON prevalence, which impedes reliance on accurate prevalence estimates (Valente et al., Citation2019). These gaps hamper the formalization of ON as a diagnosis and raise skepticism among scholars and diagnostic institutions.

While scholars and diagnostic institutions are skeptical with considering ON a formal diagnosis, ON has gained traction within popular discourses about disordered eating, being promptly presented as a new disorder about which to be alert (Hanganu-Bresch, Citation2019; Missbach & Barthels, Citation2017; Santarossa et al., Citation2019). By the early 2010s, popular reports claiming the existence of a ‘new eating disorder’ spread both in paper and online media (Hanganu-Bresch, Citation2019), and today there is a plethora of books, documentaries, and informative articles about ON (see e.g., Chalmers, Citation2017; Mcgregor, Citation2017; SuChin Pak, Citation2012). The popularity of ON on social media is particularly noticeable; to date, over 150 000 pictures have been shared on Instagram using the hashtag #orthorexia, and conversations about ON on Twitter have also been identified (Hanganu-Bresch, Citation2019). It consequently seems that social media platforms have mediated the uptake of the concept from the scientific community to society (Hanganu-Bresch, Citation2019), and set in motion a process of medicalization of ON.

Medicalization as a discursive process

Medicalization describes the process through which non-medical conditions (e.g., social phenomena) become defined and treated as medical problems. Although the term has often been used with negative connotations (i.e. over-medicalization), medicalization per se is neither positive nor negative (Conrad, Citation1992; Fainzang, Citation2013). While in the past the term ‘medicalization’ was often used to highlight the increasing jurisdiction of the medical profession, today it is recognized that lay people and patients are active players in the process too (Ballard & Elston, Citation2005). The increased awareness of citizens of their health as well as their active participation in health discourses can be traced back to the implementation of neoliberal policies by Western societies, which aim to decentralize the responsibility for health – through, for example, educating citizens on health issues – in order to reduce health expenditures (Capacci et al., Citation2012). This greater responsibility for health turns citizens into ‘health entrepreneurs’ (Salter & Dickson, Citation2020) and makes them knowledgeable about medical issues and language. The ‘health literacy’ of citizens is further amplified by social media and the Internet, which allow individuals to quickly obtain, generate and disseminate information regarding medicine and health, thus making medical knowledge more accessible to all and fostering health consumerism. Consequently, medicine becomes the framework through which citizens express their emotions, rendering them active players in the process of medicalization too.

Medicalization is a discursive process that exists and develops through communicative interaction. This idea has its roots in the social construction theory, which postulates that phenomena do not derive their meaning from phenomena themselves, but rather that meaning develops through social interaction between individuals – i.e. people’s interactive definition-making (Brown, Citation2016; Conrad & Barker, Citation2010). Via symbolic convergence, communication allows individuals to converge their meaning into a shared symbolic system, which may promote or resist medicalization (McCabe, Citation2009). As such, medicalization is never completed, but rather remains fluid, contingent and contextual as a result of the ever-shifting discussions around health (Bell, Citation2016). An example of the fluid process of medicalization is the evolving context of sexual politics exemplified by the medicalization and subsequent demedicalization of BDSM/kink. It was initially medicalized by psychiatrists, mental health institutions and the forensic population, who appealed to arguments around morality and ‘normalcy’ of sexual practices. However, the increasing number of studies exploring BDSM/kink through a sociological and anthropological perspective, together with a raise in advocacy from grassroot organizations, led BDSM/kink to be consistently demedicalized in recent years (Lin, Citation2017).

Analyzing discourses that guide the medicalization of certain phenomena displays the interacting forces and the discursive struggles between different types of actors. Such interactions are particularly important in that they illustrate power structures in who is allowed to define illnesses, which has implications for how we attribute normalcy or deviance, and causation or responsibility for diseases (Johnson & Quinlan, Citation2015). This is particularly relevant in an age where the Internet and social media have allowed the ‘controlled populations’ to increasingly be able to place themselves on equal footing with the ‘institutions of control’ (Lin, Citation2017).

Medicalization on social media: The case of orthorexia nervosa on Twitter

Social media has entered health communication research as a platform allowing for the analysis of health-related conversations and therefore the development of insights into health communication mechanisms, approaches and strategies. Some studies have focused on differences between social media platforms in the way in which users engage in conversations (e.g., Guidry et al., Citation2020). Other studies have explored the role of hashtags in bringing together and coordinating communities with a shared interest in a specific event or topic (Bruns & Burgess, Citation2015). Social media has also been used to track health communication strategies concerning health promotion and disease prevention (Guidry et al., Citation2019). Yet, the concept of medicalization on social media has scarcely been addressed. Predominant attention has been paid to how medicalization is carried out or resisted by traditional media, such as newspaper articles (Williams et al., Citation2008). However, in a time of increased ‘self-medicalization’ (Fainzang, Citation2013), the role of social media as a platform on which medical phenomena are socially constructed has become crucial.

Social media platforms are spaces where one can observe interactions and controversies between different types of knowledge, like medical vs. popular, which influence the social construction of ON as a medical problem. For example, what type of knowledge has supremacy over the other may reflect inherent power relationships and structures (Johnson & Quinlan, Citation2015).

Conversations about ON have been identified both on Instagram and Twitter (Hanganu-Bresch, Citation2019; Santarossa et al., Citation2019), but only Instagram has been explored in this regard (Santarossa et al., Citation2019). A quantitative content analysis into the #orthorexia conversation on Instagram suggests that Instagram is used as a supportive platform, where people who self-identify as suffering from ON like to share personal stories and supportive content (Santarossa et al., Citation2019). Studies about ON on Twitter seem to be missing. Twitter is a microblogging social media platform that counts up to 330 million monthly active users (Statista, Citation2019, August 14). It allows users to interact through messages containing 280 characters called “tweets.” Registered users can post, repost and ‘like’ other tweets, or mention other users. In past years, Twitter has increasingly attracted researchers’ attention as a source of data to be used in social science research (Weller et al., Citation2014). The platform has the potential to provide an interesting snapshot of different forces and discourses shaping the medicalization of ON, since it is increasingly used by scholars to share their knowledge and create networks (Weller et al., Citation2014), as well by a greater number of nonprofit entities and (news) organizations than Instagram (Guidry et al., Citation2020).

Study aim and research question

The aim of this mixed-methods study is twofold: the quantitative component aims to provide descriptive information on the type of tweets and users, as well as on the network structure of the ON-related conversation on Twitter, while the qualitative component aims to explore how the medicalization of ON unfolds on Twitter by performing a thematic analysis of original tweets about ON. The research question of this study is: “How do Twitter conversations about ON reveal the discursive processes of medicalization?”. Answering this question is important for health communication researchers and practitioners as it exemplifies how new and emerging disorders are framed on Twitter, and how this can be interpreted in light of medicalization. It also allows for displaying possible tensions around defining normality and pathology, enriching literature on health communication and medicalization.

Methods

This study adopted mixed methods. Quantitative data were obtained about the Twitter metrics – e.g., the number and type of tweets and the type of users engaging in the conversation about ON on Twitter – and the network structure of the conversation. Qualitative inductive thematic analysis (Braun et al., Citation2016) of original tweets was performed and the codes generated were clustered into broader themes, which reflected the main concepts emerging from the literature around medicalization.

Data extraction

Tweets containing the keyword “orthorexia” (both in hashtag-form and as a word) shared in 2019, from August 7th at 07:10 h, to August 16th at 01:46 h, were downloaded from Twitter through the open source tool TAGS. This tool works as a Google Sheet template that facilitates setup and automated collection of search results from Twitter. It uses Twitter’s Application Programming Interface (API) to ingest all tweets that match the tracking criteria. A choice was made for a timeframe of one week because an initial search on Twitter performed by the authors led to the conclusion that there would have been a considerable number of tweets in this timeframe that could suit the purpose of this study. The search was executed on August 16th, 2019 and Twitter’s API collected tweets shared during the previous seven days. Information extracted by TAGS included: user name, text of the tweet, date and time of the tweet, type of tweet, number of user’s followers, and their connections.

Data analysis

Quantitative analysis

Data extracted through TAGS were converted in excel-form and analyzed through the data analysis and visualization software package Tableau Desktop, version 2019.2. Quantitative data analysis was informed by the metrics proposed by Bruns and Stieglitz (Bruns & Stieglitz, Citation2013). The different metrics that were used to collect and analyze descriptive twitter data are (I) content metrics (i.e. types of tweets shared on Twitter, such as original tweets, retweets or @mentions), (II) user metrics (i.e. contributions made by specific users to the conversation around the topic considered) and (III) network analysis (visualization of the structure of the entire network and the nodes) (Bruns & Stieglitz, Citation2013). Network analysis was performed using the software Gephi 0.9.2 and the ForceAtlas2 layout was used to visualize the network structure. Number of nodes and edges, and average and weighted degrees (wd) were calculated.

Qualitative analysis

Inductive thematic analysis was performed on the original tweets. From the excel extraction sheet, original tweets were imported into a word document. The users’ IDs were maintained in order to be able to classify them according to their gender and profession, when this information was reported in their biography. All users’ IDs were subsequently deleted. The majority of tweets were in English; tweets in languages other than English (Greek nr.1, Swedish nr.1, Spanish nr.1, Japanese nr.1, Korean nr.1, Dutch nr.1, Indonesian nr.1) were translated through Google Translate. Tweets that only shared a link to an external source or without a relevant meaning (e.g., ‘I came across the word orthorexia’) were excluded from the analysis. The six phases proposed by Braun et al. (Citation2016) were followed for thematic analysis. First, tweets were analytically read and notes were taken during the process (familiarization phase). Second, tweets were imported into Atlas.ti and coded, meaning a label was assigned to specific parts of text (coding phase). Third, codes were clustered into higher level patterns, which revolved around main thematic areas that emerged from the literature about medicalization (theme development phase). Fourth, it was checked whether the analysis fit with the data, and whether the storyline was coherent with the research question (refinement phase). Fifth, themes were defined and named, thus building depth into the analysis (naming phase). Lastly, analysis was reported into the final manuscript (writing up phase) (Braun et al., Citation2016). In order to preserve anonymity of users, all tweets reported in the manuscript have been rephrased. Codes, analyses and rephrasing were discussed throughout analysis with the research team to enhance validity.

Ethical considerations

To comply with ethical standards, this study relied upon the recommendations enacted by the AoIR Ethics Working Committee on Ethical Decision-Making and Internet Research (Version 2.0) (Markham & Buchanan, Citation2012). These recommendations propose six guiding principles for Internet research, which were considered in the present study (Markham & Buchanan, Citation2012). Regarding the issue of the involvement, or otherwise, of human participants, the report specifies: “If the connection between the object of research and the person who produced it is indistinct, there may be a tendency to define the research scenario as one that does not involve any persons” (Markham & Buchanan, Citation2012). Data collected in this study were anonymized; however, to provide context for the tweets, gender and profession were reported when possible. Furthermore, tweets reported were rephrased to ensure anonymity. For this reason, no ethical review was required from an external institution in order to conduct this research.

Results

Below, first the quantitative findings are discussed, divided by content metrics, user metrics, and the results from the network analysis. Then, the qualitative results displaying the main themes that emerged from the tweets are reported: (1) orthorexia as a medical problem: using medicine as a framework; (2) orthorexia as a social problem: sociocultural trends and the rise of the ‘orthorexic society’; (3) the emergence of a discoursive tension: are we pathologizing healthy eating?

Quantitative findings

Content metrics

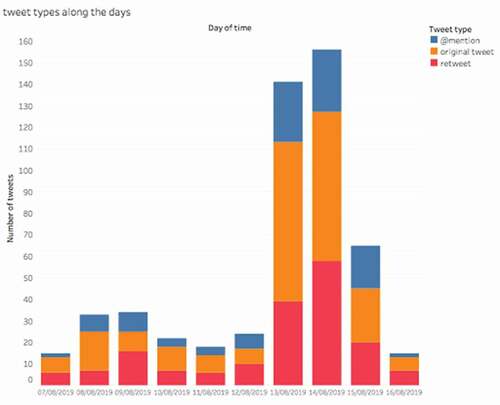

A total of 522 tweets regarding ON shared from August 7 to August 16 2019 were extracted from Twitter. Among those were 234 original tweets, 175 retweets, and 113 @mentions. All tweets contained the keyword “orthorexia” in hashtag-form or as a word. To acquire a preliminary understanding of the nature of the content posted about ON, secondary hashtags beyond the hashtag “#orthorexia” were identified. The most popular hashtag associated to ON was #rdchat, with “rd” meaning “registered dietitian.” Others were #healthyfood, #psychology, #doctors, and #eatingdisorders. The fact that the secondary hashtag most frequently associated to “orthorexia” was #rdchat indicates an active engagement of nutritionists in the conversation about ON on Twitter. Other frequent hashtags, such as #psychology and #doctors, hint to a link between discourses around ON and the medical profession.

Many retweets concerned one specific article published online by the Canadian news portal National Post: “Orthorexia vying for classification as mental disorder as more people become obsessed with ‘clean eating’” (Kirkey, Citation2019). A considerable number of users shared, or commented on this article, sparking a peak of tweets over time, as shown in . The popularity of the article published by the National Post suggests that popular informative articles may be an important source of information about ON. By saying that ON is ‘vying for classification as a mental disorder,’ the title of the article inevitably brings up the topic of medicalization. This may have stimulated a reaction from those who are in favor of medicalizing ON, as well as those who are against it.

User metrics

The five most active, prominent, and visible users who engaged in the conversation about ON on Twitter were identified. Most active users are those who tweeted about ON the most, most prominent users are those with the larger number of followers who tweeted about ON, and most visible users are the most mentioned/retweeted users who tweeted about ON. An anonymous overview of Twitter users involved in the conversation about ON is reported in .

Table 1. Overview of the five most active, prominent and visible users

The five most prominent users were Twitter accounts of online news portals, while these were much less present in the list of most active and visible users. This means that news agencies do post about ON occasionally, but do not contribute much to the discussion about the phenomenon. Instead, personal accounts receive more attention in the form of retweets and mentions. The most active account was shown to be a registered dietitian and among the most visible accounts were those of a professor, a researcher, and an editor, suggesting a centrality of the professional sphere in the conversation about ON on Twitter.

Network analysis

The network structure of the conversation about ON in one week on Twitter is reported in . Users seem to be rather isolated from each other, indicating that the conversation is not dynamic. However, some agglomerations are visible. The accounts representing the four main nodes of the network structure and their respective weighted degree are (i) personal account (registered dietitian, wd = 15), (ii) account of online news portal (wd = 14), (iii) personal account (communication and pharma professional, wd = 5), and (iv) account of online news portal (wd = 4). The network structure tells us that the conversation is rather fragmented, with some dynamic foci of interaction around users who have a professional background.

Qualitative findings

Thematic analysis was performed on original tweets (n = 234). Tweets that only shared a link to an external source or without a relevant meaning (e.g., ‘I came across the word orthorexia’) were excluded from the analysis, leaving a total of 137 tweets. Three main themes were identified: (1) orthorexia as a medical problem: using medicine as a framework; (2) orthorexia as a social problem: sociocultural trends and the rise of the ‘orthorexic society’; (3) the emergence of a discoursive tension: are we pathologizing healthy eating?

Orthorexia as a medical problem: Using medicine as a framework

Some users defined ON as a problem belonging to the medical sphere through different strategies: (a) using medical jargon; (b) explaining orthorexia in terms of existing diagnoses; (c) reporting a lived experience with orthorexia; (d) warning the individual. These strategies, which contribute to bringing about medicalization, allude to an individual responsibility for ON.

Using medical jargon

Some individuals use terminology and concepts belonging to the medical profession, which contributes to allocating ON a medical aurea. For example, some people mention the ‘Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders’ (DSM) in their tweets, and the words ‘recovery’ and ‘diagnosis’ can also be found. Furthermore, some tweets report phrases such as ‘experts warn,’ ‘some doctors believe,’ and ‘researchers found’ when talking about ON, which gives professional value to what is being said.

Explaining orthorexia in terms of existing diagnoses

ON is often equated or opposed to other existing disorders. This is done not only to show the differences with other diagnoses and therefore to advocate for a separate diagnostic category for ON but also to highlight the similarities with other disorders that have already a diagnosis, in order to advocate for the recognition of ON by the DSM. For example, outlining the differences with existing eating disorders is a strategy deployed to stress the importance to consider less mainstream eating disorders: “Anorexia is the number 1 mental illness with most deaths, but just for educational purposes, it is NOT the only eating disorder. There are binge eating disorder, orthorexia and many others that go beyond being skinny” (background unknown, female). At the same time, juxtaposing ON to other disorders contributes to placing ON on the same level as existing diagnoses: “I wanted to lose weight, therefore I started dieting and exercising when I was 15, then it snowballed into a 10 years struggle with anorexia, orthorexia, and exercise addiction […]” (person with an eating disorder, female), or “When are we going to hold orthorexia to the same standard as anorexia and bulimia? I am waiting for it!” (background unknown, female).

Reporting a lived experience with orthorexia

Referring to a personal experience with the disorder is a way to emphasize the seriousness of ON. In such instances, experiences become facts (Dumit, Citation2006) that are used to warn against the danger of ON: “[the description of ON] recalls many people that I know, including myself in the past!! Eat good food with moderation, since life is too short to not eat that cookie!” (nurse, female), or “I did not expect her to completely fall into orthorexia. She would tell you that she is following a “healthy lifestyle,” while instead this is absolutely disordered and terrible to see!” (academic, female).

Warning the individual

Some tweets aim to inform and empower individuals to recognize and avoid ON by themselves, thus placing the responsibility in the hands of individuals: “Do you have an obsession with healthy eating? You could have orthorexia” (eating disorder advocacy page), or “Do you know somebody who is obsessed with healthy or clean eating? This can indicate the presence of orthorexia nervosa […]” (background and gender unknown).

Orthorexia as a social problem: Sociocultural trends and the rise of the ‘Orthorexic society’

Other users describe ON as a product of Western sociocultural trends, and therefore as a cultural phenomenon, rather than a medical one. Cultural phenomena deemed to be responsible for the rise of ON are (a) social media, (b) diet culture, and (c) lack of religious faith. These discourses resist medicalization and tend to ‘politicize’ ON, hence hinting to a societal rather than medical solution for ON, and to a societal rather than individual responsibility for ON.

Social media

Some individuals claim that certain accounts on social media would trigger the onset and progression of ON: “I am extremely annoyed by wellness-related and clean eating-related accounts on social media, because these are just trying to mask orthorexia nervosa” (background unknown, female).

Diet culture

Diet culture is pointed to as contributing to ON. Some individuals claim that diet culture and cultural trends would cause ON: “Do you also agree that diet culture is getting worse? I mean, I know that we have been living in an ‘orthorexia culture’ for some time now, but the advent of intermittent fasting and all these other trends … ” (background unknown, female). Another user points the finger to the development of a calorie-counting application promoted for kids: “Yes, this will be a success. It is not like there is a lot of research showing the negative effects of diet culture, such as for example, an emerging eating disorder called orthorexia!!” (background unknown, female).

Lack of religious faith

One tweet considers the lack of religious faith of modern Western society a factor contributing to ON: “Being obsessed with clean and pure food may be due to the fact that people have lost religious faith and started being devoted to food instead [link]” (background unknown, male).

The emergence of a discoursive tension: Are we pathologizing healthy eating?

A discoursive tension arises, where some people resist medicalization in an attempt to de-pathologize what they consider it to be healthy/clean eating, or non-traditional diets like veganism. Within this category, three sub-categories can be distinguished: (a) confusion around what falls into orthorexia; (b) stigma toward non-traditional diets; (c) over-medicalization.

Confusion around what falls into orthorexia

The lack of diagnostic boundaries delineating ON creates uncertainty around what can be considered ON. Precisely, people do not understand if clean/healthy eating has to be considered pathological with the advent of ON: “Is clean eating considered a mental condition now? Evidence suggests that eating clean/healthy foods helps with mental health issues, such as depression and anxiety [link]“ (mental health advocate, male), or “Is it clean eating or orthorexia nervosa a pathological obsession with healthy eating? […]” (nutritionist, female).

Stigma toward non-traditional diets

Non-traditional diets, such as veganism and vegetarianism, become pointed to as ON. Precisely, some people stigmatize those who follow a vegan diet: “Orthorexia nervosa is the reason why I will never become vegan [link]” (registered dietitian, female), while people following non-traditional diets feel stigmatized: “It’s 15 years I have been following a vegetarian diet, but coming across this (orthorexia) really disturbs me [link]” (sustainability advocate, female).

Over-medicalization

Some people raise the concern of over-medicalization, as they feel that ON may be a way to impose medical control over social phenomena: “Profoundly bizarre that at a certain point every behavior will be pointed to as a mental condition […]” (background and gender unknown). Sometimes, there is even a direct accusation against health professionals: “Breaking news: psychiatrists say that eating pure food should be considered a mental illness […]. Maybe, they themselves need a treatment?!” (background and gender unknown).

Discussion

With the aim of exploring the discursive process of the medicalization of ON, this mixed-methods study dove into the conversation about ON on Twitter. Quantitative descriptive findings show that the most popular hashtags associated with orthorexia include #rdchat, #psychology and #doctors, which suggest that there is a link between discourses around ON and the medical/professional domain. The publication of an article about ON from a popular news agency sparked a peak of tweets over time; among the most active, prominent and visible users are news accounts, a registered dietitian, a researcher, a professor and an editor. Additionally, the network structure shows that users engaging in the conversation about ON on Twitter are isolated from each other. Qualitative thematic analysis shed light on the discursive process of the medicalization of ON. Some users bring about medicalization by approaching ON as a medical entity, which is done by using medical jargon, explaining ON in terms of existing diagnoses, relying on experiential knowledge, and warning individuals against ON. In contrast, other users describe ON as a social phenomenon, thus ascribing the causes of ON to social media, diet culture, and the lack of religious faith of modern Western society. The last category that emerged from thematic analysis illustrates a discursive struggle, where certain individuals feel confused about what constitutes the concept of ON, which gives rise to stigma toward non-traditional diets, such as veganism, and to accusations of over-medicalization directed to the medical profession.

Social media provides a space in which individuals interpret knowledge that comes from different sources, and express their opinions and concerns in regard to emerging disorders. On social media, professionals and clients interact with each other, and with concepts and values. This interaction is particularly important for emerging eating disorders, as they are a product of social exchange and reflect wider sociocultural conditions. Studying conversations around eating disorders is therefore particularly important, as it shows how individuals reproduce, negotiate or resist broader cultural norms (Busanich et al., Citation2014; Cinquegrani & Brown, Citation2018). By exploring the narratives of individuals who position themselves differently around discourses about ON, we were able to shed light on the socio-political tensions around pathologizing an “obsession with healthy eating” (Fixsen et al., Citation2020).

The qualitative analysis reveals that medicalization is both carried out and resisted at the same time. This is done by mixing personal and medical beliefs and by using experiences as facts (Dumit, Citation2006), which are deployed to steer and resist medicalization. Discourses around the need, or lack thereof, to medicalize ON and to hold it to the same standard as anorexia or bulimia foreshadow issues around responsibility. Tweets that conceptualize ON as a medical problem place the responsibility of ON in the individual’s hands and thus tend to individualize ON. In this case, the individual is deemed responsible for and empowered to recognize and avoid ON. In contrast, tweets underlining the sociocultural roots of ON tend to place the responsibility of ON in societal hands, thereby politicizing ON and the consequent suffering. In this case, a social explanation is furnished for a problem that increasingly affects society as a whole. The discursive tension that arises from these discourses exemplifies confusion around what becomes pathological with the advent of ON, and shows a consequent rebellion of those who think their eating habits are being labeled as ‘disordered’ by ‘doctors.’ These findings ultimately remind us that the creation of a diagnosis could somewhat hinder a broader societal change (Ross Arguedas, Citation2020).

Twitter conversations about ON extend the theoretical understanding of medicalization. The history of medicalization has seen shifts in the actors steering medicalization: first the medical profession, then the pharmaceutical industry, and last patients and lay people (Ballard & Elston, Citation2005; Conrad, Citation1992; Fainzang, Citation2013). When examining the findings of the present study, it becomes apparent that the boundary between medical and popular spheres is somewhat blurred. It is difficult to discern whether it is professionals or the public who prevail in medicalizing ON, as professionals seem to be prominent in the conversation about ON on Twitter, yet the sources of information that are shared belong to the popular sphere, where no academic article or scientific evidence is recalled in the discussion. A suggestion for future research would be to explore whether different actors (professionals vs. clients) are responsible for both carrying out and resisting medicalization, and whether these differences indicate underlying power dynamics.

We found that the discoursive processes of medicalization and demedicalization of ON occur simultaneously on Twitter. This finding rejects the notion that medicalization is ubiquitous while demedicalization is rare, and instead reminds us that medicalization is a fluid, often incomplete, ongoing process. The interstices where medicalization runs in the opposite direction, i.e. demedicalization, provide opportunities for those who resist medicalization to make their voices heard (Halfmann, Citation2012). The findings of the present study can be interpreted in light of the medicalization typology proposed by Halfmann (Citation2012). This typology distinsguishes three dimensions of medicalization: (i) discourses, (ii) practices, and (iii) identities, which all can happen at three levels: macro-, meso- and micro-level. Within this framework, the results of this study show that medicalization of ON manifests on Twitter in the form of discourses (e.g., use of medical vocabulary, concepts and definitions) that happen at a micro-level (e.g., interactions among professionals, clients and lay people), with sporadic cases of meso-level discoursive medicalization (e.g., discourses carried out by foundations, universities and journals). The medicalization of ON also manifests in the form of identities (e.g., medical/professional actors become more prevalent in addressing ON and clients identify themselves as “patients”), which happens at a micro-level (e.g., among doctors/professionals and clients), at a meso-level (e.g., among medical and no-profit organizations), and at a macro-level (e.g., among foundations, universities and popular media).

Some practical implications can be derived from the findings of this study. The first implication concerns the role of language in defining what is and is not disordered eating. The adoption of the term “Orthorexia Nervosa” to indicate the condition recalls other existing eating disorders and therefore leads one to consider ON a medical condition, even if the disorder has not yet been included in the DSM. The crucial role of language in determining what constitutes ‘pathological’ is exemplified by the association of ON with clean eating by several users after the publication of a popular article claiming that ON would be an “obsession with clean eating” (Kirkey, Citation2019). This suggests that attention should be paid to the way emerging disorders are spoken about, in order to avoid certain non-pathological conditions or alternative diets being medicalized. A second implication of these findings concerns the usefulness of consulting different perspectives – professionals, lay people, clients – in investigating and conceptualizing ON. The phenomenon of ON has gained popularity online and has sparked the interest of many. In the description of ON, some people recognize their past experiences or those of friends and acquaintances, which leads them to reflect on the phenomenon and to speculate on possible risk factors. A suggestion for future research would be to refer to online conversations in order to acquire information on emerging disorders that still lack a diagnosis, and to consult people who have an interest in and opinion about a phenomenon they possess experiential knowledge about.

Some limitations of this study should be highlighted. A methodological limitation concerns the collection of data, as a small margin of error should be accepted since there is no guarantee that all tweets matching the tracking criteria were captured by the API – a temporary interruption may have caused gaps in transmission. Another limitation concerns the relatively small number of tweets gathered in the present study, which also provided challenges in visualizing the network structure. The number of tweets that allowed the performing of thematic analysis was also relatively small, since many tweets were simply sharing external links, or did not allow the researchers to grasp the user’s perspective due to the shortness of text. However, this is also a noteworthy finding, which highlights Twitter’s informative nature, as opposed to personal or supportive. Lastly, the search was performed by selecting tweets that included the English keyword “orthorexia.” It is possible that tweets were shared about ON in that same period, yet in other languages. It is worth noting that ultimately our data represent only a snapshot of the process of medicalization at the specific point in time of data collection, and that additional discursive contributions continue to shape the ongoing discussion and evolution of ON.

Conclusion

In a time of increased “self-medicalization,” the role of social media as platforms where individuals are both creators and consumers of information has become crucial. This study consists of the first investigation into the ON-related conversation on Twitter. The findings of this study enrich the literature on health communication and medicalization. Ultimately, this study serves the purpose of providing insights into how an emerging disorder develops within society in a time of social media.

Disclosure of potential conflict of interest

No conflict of interest to declare.

References

- Ballard, K., & Elston, M. A. (2005). Medicalisation: A multi-dimensional concept. Social Theory & Health, 3(3), 228–241. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.sth.8700053

- Bell, A. V. (2016, May). The margins of medicalization: Diversity and context through the case of infertility. Social Science & Medicine, 156, 39–46. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.03.005

- Bratman, S. (1997). Orthorexia Essay. Orthorexia. https://www.orthorexia.com/original-orthorexia-essay/

- Bratman, S. (2017). Orthorexia vs. theories of healthy eating. Eating and Weight Disorders - Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity, 22(3), 381–385. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-017-0417-6

- Braun, V., Clarke, V., & Weate, P. (2016). Using thematic analysis in sport and exercise research. In B. Smith & A. C. Sparkes (Eds.), Routledge handbook of qualitative research in sport and exercise (pp. 191–205). Routledge. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315762012.ch15

- Brown, P. (2016). Naming and framing: The social construction of diagnosis and illness. Journal of Health and Social Behaviour, 366, 34–52. http://www.aleciashepherd.com/writings/articles/other/Naming%20and%20framing%20The%20social%20construction%20of%20diagnosis.pdf

- Bruns, A., & Burgess, J. E. (2015). Twitter hashtags from ad hoc to calculated publics. In N. Rambukkana (Ed.), Hashtag publics: The power and politics of discursive networks (pp. 13–28). Peter Lang Pub Inc. https://eprints.qut.edu.au/90461/

- Bruns, A., & Stieglitz, S. (2013). Towards more systematic twitter analysis: Metrics for tweeting activities. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 16(2), 91–108. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2021.756095

- Busanich, R., McGannon, K. R., & Schinke, R. J. (2014). Comparing elite male and female distance runner’s experiences of disordered eating through narrative analysis. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 15(6), 705–712. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2013.10.002

- Capacci, S., Mazzocchi, M., Shankar, B., Brambila Macias, J., Verbeke, W., Pérez-Cueto, F. J., Koziol-Kozakowska, A., Piorecka, B., Niedzwiedzka, B., D’Addesa, D., Saba, A., Turrini, A., Aschemann-Witzel, J., Bech-Larsen, T., Strand, M., Smillie, L., Wills, J., & Traill, W. B. (2012). Policies to promote healthy eating in Europe: A structured review of policies and their effectiveness. Nutrition Reviews, 70(3), 188–200. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1753-4887.2011.00442.x

- Cena, H., Barthels, F., Cuzzolaro, M., Bratman, S., Brytek-Matera, A., Dunn, T., Varga, M., Missbach, B., & Donini, L. M. (2019). Definition and diagnostic criteria for orthorexia nervosa: A narrative review of the literature. Eating and Weight Disorders - Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity, 24(2), 209–246. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-018-0606-y

- Chalmers, V. (2017, July 7). My clean eating became orthorexia nervosa. Healthista. https://www.healthista.com/my-clean-eating-obsession-became-orthorexia-nervosa/

- Cinquegrani, C., & Brown, D. H. K. (2018). ‘Wellness’ lifts us above the food chaos’: A narrative exploration of the experiences and conceptualisations of orthorexia nervosa through online social media forums. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 10(5), 585–603. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2018.1464501

- Clement, J. (2019, August 14). Twitter: Monthly active users worldwide. Statista. Retrieved January 14, 2021, from https://www.statista.com/statistics/282087/number-of-monthly-active-twitter-users/

- Conrad, & Barker, K. K. (2010). The social construction of illness: Key insights and policy implications. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 51(1_suppl), S67–S79. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0022146510383495

- Conrad, P. (1992). Medicalization and social control. Annual Review of Sociology, 18(1), 209–232. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.so.18.080192.001233

- Cuzzolaro, M., & Donini, L. M. (2016). Orthorexia nervosa by proxy? Eating and Weight Disorders - Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity, 21(4), 549–551. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-016-0310-8

- Dumit, J. (2006). Illnesses you have to fight to get: Facts as forces in uncertain, emergent illnesses. Social Science & Medicine, 62(3), 577–590. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.06.018

- Fainzang, S. (2013). The other side of medicalization: Self-medicalization and self-medication. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry, 37(3), 488–504. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11013-013-9330-2

- Fixsen, A., Cheshire, A., & Berry, M. (2020). The social construction of a concept — Orthorexia nervosa: Morality narratives and psycho-politics. Qualitative Health Research, 30(7), 1101–1113. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732320911364

- Guidry, J. P. D., Meganck, S. L., Lovari, A., Messner, M., Medina-Messner, V., Sherman, S., & Adams, J. (2019). Tweeting about #diseases and #publichealth: Communicating global health issues across nations. Health Communication, 35(9), 1137–1145. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2019.1620089

- Guidry, J. P. D., Sawyer, A. N., Burton, C. W., & Carlyle, K. E. (2020). #NotOkay: Stories about abuse on Instagram and Twitter. Partner Abuse, 11(2), 117–139. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1891/pa-d-18-00037

- Halfmann, D. (2012). Recognizing medicalization and demedicalization: Discourses, practices, and identities. Health: An Interdisciplinary Journal for the Social Study of Health, Illness and Medicine, 16(2), 186–207. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1363459311403947

- Hanganu-Bresch, C. (2019). Orthorexia: Eating right in the context of healthism. Medical Humanities, 46(3), 311–322. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/medhum-2019-011681

- Johnson, B., & Quinlan, M. M. (2015). Technical versus public spheres: A feminist analysis of women’s rhetoric in the twilight sleep debates of 1914–1916. Health Communication, 30(11), 1076–1088. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2014.921269

- Kirkey, S. (2019, August 13). ‘Orthorexia’ vying for classification as mental disorder as more people become obsessed with ‘clean eating’. National Post. https://nationalpost.com/health/orthorexia-vying-for-a-place-in-the-dsm-as-more-people-become-obsessed-with-clean-eating

- Lin, K. (2017). The medicalization and demedicalization of kink: Shifting contexts of sexual politics. Sexualities, 20(3), 302–323. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1363460716651420

- Markham, A., & Buchanan, E. (2012). Ethical decision-making and internet research: Recommendations from the AoIR ethics working committee (version 2.0). AoIR. aoir.org/reports/ethics2.pdf

- McCabe, J. (2009). Resisting alienation: The social construction of internet communities supporting eating disorders. Communication Studies, 60(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10510970802623542

- Mcgregor, R. (2017). Orthorexia: When healthy eating goes bad. Nourish Books.

- Missbach, B., & Barthels, F. (2017). Orthorexia nervosa: Moving forward in the field. Eating and Weight Disorders - Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity, 22(1), 1. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-017-0365-1

- Ross Arguedas, A. A. (2020, February). “Can naughty be healthy?”: Healthism and its discontents in news coverage of orthorexia nervosa. Social Science & Medicine, 246, Article: 112784. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.112784

- Salter, L., & Dickson, A. (2020). The fantasy of healthy food: Desire and anxiety in healthy food guide magazine. Critical Public Health, 1–13. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09581596.2020.1724262

- Santarossa, S., Lacasse, J., Larocque, J., & Woodruff, S. J. (2019). #Orthorexia on Instagram: A descriptive study exploring the online conversation and community using the Netlytic software. Eating and Weight Disorders - Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity, 24(2), 283–290. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-018-0594-y

- SuChin Pak. (2012). I have orthorexia nervosa [TV Episode 2012]. IMDb. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt2339255/

- Valente, M., Syurina, E. V., & Donini, L. M. (2019). Shedding light upon various tools to assess orthorexia nervosa: A critical literature review with a systematic search. Eating and Weight Disorders - Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity, 24(4), 671–682. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-019-00735-3

- Weller, K., Bruns, A., Burgess, J., Mahrt, M., & Puschmann, C. (2014). Twitter and society. Peter Lang.

- Williams, S. J., Seale, C., Boden, S., Lowe, P., & Steinberg, D. L. (2008). Medicalization and beyond: The social construction of insomnia and snoring in the news. Health: An Interdisciplinary Journal for the Social Study of Health, Illness and Medicine, 12(2), 251–268. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1363459307086846

![Figure 2. Network structure of the conversation about ON in one week in August 2019 [Nodes: 338, Edges: 272, Average degree: 0.805, Average weighted degree: 0.852].](/cms/asset/0d687424-1e0f-4c38-bd1a-86792f70653f/hhth_a_1875558_f0002_b.gif)