?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

To mitigate the impacts and spread of COVID-19, drastic mitigative actions are demanded from individuals worldwide, including social distancing, health behaviors, and self-quarantining. A key question is what motivates individuals to take and support such actions. Early in the COVID-19 crisis, we hypothesized and found in two studies (in the Netherlands and United States) that stronger worries about potential consequences of COVID-19 for oneself and close others (i.e., family and friends), as well as more “distant” others (e.g., citizens in general, vulnerable populations), are associated with stronger engagement in actions to mitigate COVID-19. In line with reasoning on norm activation, we found that these associations were partly mediated by personal norms, reflecting individuals’ feelings of being morally compelled and personally responsible to take mitigative actions. Importantly, individuals generally reported to worry more about consequences of COVID-19 for distant others than for themselves, and worries about distant others were more strongly related to mitigative actions than worries about oneself and close others. Our outcomes offer key novel insights to the health domain, highlighting the potential relevance of worrying about distant others and personal norms in motivating actions to mitigate global health crises.

Introduction

The coronavirus disease (COVID-19) is having unparalleled disruptive impacts on people and societies worldwide. The virus has quickly spread across the world, is posing major health risks to individuals, and already caused millions of deaths, in particular among vulnerable populations (e.g., elderly people, people with preexisting health problems; World Health Organization [WHO], Citation2020). The mitigative measures necessary to limit the spread and impacts of COVID-19 require immediate and unprecedented lifestyle changes which are often inconvenient and costly, such as social distancing (i.e., keeping distance from others and staying at home except for essential journeys), health behaviors (e.g., hand washing), and self-quarantining (WHO, Citation2020). Accordingly, an urgent question is: what motivates individuals to support and take the measures needed to limit the spread of COVID-19?

Research suggests that individuals who worry more about the negative consequences of a threat for themselves and “close others”, such as family and friends, are more likely to support and take action to mitigate the threat (Cameron & Reeve, Citation2006; Petrocchi et al., Citation2021; Verplanken et al., Citation2020). Interestingly however, polls suggest that in case of COVID-19 many individuals may worry more about negative consequences for “distant others,” such as national citizens or vulnerable populations, than for themselves and close others (Ipsos, Citation2020a; Pew Research Center, Citation2020a; Wise et al., Citation2020). Yet, the question remains whether and how worries about distant others can also motivate individuals to take and support the measures demanded to mitigate COVID-19, next to worries about oneself and close others. In this paper, we address this question by examining to what extent and why worries about consequences for oneself and close others, as well as distant others, are likely to motivate mitigative actions.

Emotional responses to threats as drivers of mitigative actions

COVID-19 is posing major threats to individuals worldwide. Consequently, many individuals experience negative emotions about COVID-19 (Ipsos, Citation2020b; Pew Research Center, Citation2020b; Taylor, Landry, Paluszek, Fergus et al., Citation2020). The experience of such negative emotions is often considered to deprive individuals’ wellbeing (Petrocchi et al., Citation2021; Sebri et al., Citation2021; Taylor, Landry, Paluszek, Fergus et al., Citation2020; Verplanken et al., Citation2020). At the same time, such negative emotions may be critical in motivating individuals to engage in actions that may limit the spread of COVID-19 (Cameron & Reeve, Citation2006; Harper et al., Citation2020; Schmiege et al., Citation2009; Verplanken et al., Citation2020; Wise et al., Citation2020), such as social distancing, hand washing and self-quarantining, which are all urgently needed at a large scale to mitigate the COVID-19 pandemic (WHO, Citation2020). Accordingly, it important to identify those emotions that motivate individuals to take and support mitigative actions, ideally without deteriorating their general wellbeing.

Research suggests that “threat-specific worries,” sometimes also referred to as constructive or habitual worry (Verplanken et al., Citation2020), may be an emotion that particularly motivates individuals to support and take mitigative actions. Threat-specific worries reflect anxious thoughts about the potential negative consequences of a specific threat (e.g., COVID-19) for an object of personal relevance (e.g., the self). Because threat-specific worries are about a specific threat to something personally relevant, individuals who experience such worries are likely motivated to support and take those actions possible that could reduce the threat’s negative consequences (Bouman et al., Citation2020; Van Der Linden, Citation2017; Verplanken et al., Citation2020).

As such, threat-specific worries differ from generalized worries, which are unspecific, abstract, and associated with anxiety-related pathologies. Because of these differences, threat-specific worries are regarded relatively constructive, while generalized worries are regarded more destructive (Verplanken et al., Citation2020). Threat-specific worries also differs from fear, which is more emotionally overwhelming than worry, and likely results in denial or avoidance of the threat (Smith & Leiserowitz, Citation2014). Further, threat-specific worry differs from more cognitive risk perceptions, as well as from concern about the threat (Schmiege et al., Citation2009; Van der Linden, Citation2017), which “can be expressed without any particular motivational or emotional content” (Van der Linden, Citation2017, p. 24). Hence, threat-specific worries may play a relatively important role in motivating individuals to take mitigative actions, which is why we concentrate on worries about the potential consequences of COVID-19.

Worrying about COVID-19

In the health domain, research typically focuses on worries about potential consequences of a threat (e.g., a disease, unhealthy habits) for oneself and close others (e.g., family, friends), and how this may motivate individuals to engage in precautionary actions and health behaviors (e.g., changing diet, stop smoking, health checks) (e.g., Cameron & Reeve, Citation2006; Diefenbach et al., Citation1999). For example, studies have found that individuals who worry more about cancer are more likely to take precautionary actions, such as genetic testing (Cameron & Reeve, Citation2006). In line with these findings, recent studies found that individuals who report stronger worries about the negative consequences of COVID-19 for themselves and close others were generally more supportive of actions to mitigate COVID-19, such as hygiene behaviors and social distancing (Petrocchi et al., Citation2021; Sobkow et al., Citation2020). We therefore hypothesize that:

H1: Stronger worries about the consequences of COVID-19 for oneself and close others are associated with stronger support for and engagement in actions to mitigate COVID-19.

Although worrying about the consequences of COVID-19 for oneself and close others may promote mitigative actions, polls and theory suggest that individuals may worry more about the consequences of COVID-19 for more distant others; in particular vulnerable groups, such as elderly people and people with preexisting health problems. Indeed, vulnerable groups are more at risk of developing severe COVID-19 symptoms than the majority of the population, which may explain why many individuals report to be particularly concerned about the consequences of COVID-19 for these groups (Ipsos, Citation2020a; Pew Research Center, Citation2020a; Wise et al., Citation2020). In addition, individuals may worry more about consequences for distant others than for themselves and close others due to an optimism bias. Specifically, the optimism bias implies that individuals structurally underestimate their chances to experience negative events, which may imply that people believe that they themselves, or people in their close proximity, are less likely to suffer from COVID-19 (Kulesza et al., Citation2020; Wise et al., Citation2020).

Whereas individuals seem more concerned about consequences of COVID-19 for distant others than for themselves and close others, little is yet known about individuals’ experiences of worry about consequences for distant others and, in particular, whether such worries impact health-related mitigative actions. Hence, a key research question is whether people worry about consequences of COVID-19 for distant others and, importantly, whether this can motivate them to support and take actions to mitigate COVID-19, next to worries about oneself and close others?

Worrying about distant others can also motivate mitigative action

On the basis of theory in environmental psychology on individuals’ responses to global environmental crises, we expect that individuals worry about consequences of COVID-19 for distant others, and that such worries can motivate them to support and take mitigative actions. Specifically, this theorizing suggests that individuals are not only driven by self-interest (e.g., negative implications for one’s personal health and wellbeing), but that they also strongly care about and are driven by the interests of others and society more broadly (Bouman & Steg, Citation2019; Bouman, Steg, Perlaviciute et al., Citation2021; Schultz, Citation2001; Schwartz, Citation1977; Steg et al., Citation2011; Stern, Citation2000). These prosocial and societal drivers are seen as key motivators of individuals’ support for and engagement in actions to mitigate global environmental crises, even when somewhat personally costly, in particular because these crises are primarily associated with negative consequences for others, societies, and ecosystems (Schultz, Citation2001; Steg et al., Citation2011; Stern & Dietz, Citation1994).

This theorizing on responses to global environmental crises may very well apply to COVID-19 (cf. Bouman, Steg, Dietz et al., Citation2021). Obviously, COVID-19 is also a global crisis, imposing threats to wider populations and societies, and requiring actions which may be seen as mostly serving the greater societal good (Bouman, Steg, Dietz et al., Citation2021; Jetten et al., Citation2020). This is reflected in the earlier observation that individuals are particularly concerned about consequences of COVID-19 for distant others (Ipsos, Citation2020a; Pew Research Center, Citation2020a; Wise et al., Citation2020), which strongly resonates with earlier findings on global environmental crises (Schultz, Citation2001; Steg et al., Citation2011), and with theorizing that individuals care about the interests of others and societies more broadly (Bouman, Steg, Perlaviciute et al., Citation2021; Schwartz, Citation1977; Stern, Citation2000).

Accordingly, on the basis of this, individuals seem likely to worry about consequences of COVID-19 for distant others and, importantly, motivated to support and take action to mitigate COVID-19 because of such worries. We therefore hypothesize that:

H2: Stronger worries about negative consequences of COVID-19 for distant others are associated with stronger support for and engagement in actions to mitigate COVID-19, even when controlling for worries about oneself and close others.

The role of personal norms

A next open question is how these worries may translate into action. In line with the theorizing on environmental global crises discussed above, and particularly the Value Belief Norm theory (Stern, Citation2000) and Norm Activation Model (Schwartz, Citation1977), we propose that worry likely motivates mitigative actions by strengthening personal norms. Personal norms reflect feelings of personal responsibility and moral obligation to take and support mitigative actions (Schwartz, Citation1977; Steg, Citation2016; Stern, Citation2000). Personal norms are argued to be stronger for individuals who believe that something personally valued is threatened (Schwartz, Citation1977; Steg, Citation2016; Stern, Citation2000) and, arguably thus, for individuals who experience threat-specific worries, as such worries are experienced when an individual perceives something of personal relevance to be threatened (Bouman et al., Citation2020). This personal norm is in turn an important predictor of actual mitigative actions, including protective behaviors and support for policy aimed to reduce the threat (Schwartz, Citation1977; Steg, Citation2016; Stern, Citation2000). From this, we hypothesize that:

H3: Stronger worries about the consequences of COVID-19 for oneself and close others, as well as for distant others, largely promote (support for) mitigative actions by strengthening personal norms to do so.

Current study

We study the extent to which worries about the consequences of COVID-19 for oneself and close others, as well as for distant others, relate to actions aimed at mitigating COVID-19, including policy support and self-reported behaviors. Moreover, we test whether these relationships are mediated by personal norms (see ). Our studies were conducted in two countries, namely the United States and the Netherlands. Both countries were at the times of data collection (end of March 2020) in a relatively early stage of the COVID-19 crisis. Yet, governmental and public responses varied considerably between countries, providing critical settings to test the generalizability of our reasoning. Additionally, we explored whether worries about COVID-19 are related to deprived subjective wellbeing, as is commonly assumed in scientific and popular discourse (Ipsos, Citation2020b; Pew Research Center, Citation2020b; Taylor, Landry, Paluszek, Fergus et al., Citation2020). Our study thereby provides key insights in the potential positive (i.e., promotion of mitigative actions) and negative impacts (i.e., deprived wellbeing) of different types of worry.

Method

We collected data in two countries: 1) the United States (March 23, 2020) and 2) the Netherlands (March 24 to April 5, 2020). In both countries, the setup of the study was highly similar, using the same procedures and measuring mostly the same items. We therefore discuss the methods of both studies together in one section.

Procedure

After signing up for our study on Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (US sample) or ThesisTools Pro (Dutch sample), and agreeing with the informed consent, respondents were directed to our online questionnaire programmed in Qualtrics, which was either in American English (US sample) or in Dutch (Dutch sample). Data was collected for multiple research projects, and therefore contained more measures than the ones reported in this manuscript. The measures that were included in the manuscript are reported boldfaced and italicized in the procedure below.

Respondents were first asked about their values and national identity, after which they indicated their beliefs about COVID-19, general emotions (including subjective wellbeing), worries about COVID-19, personal norms to take actions to mitigate COVID-19, outcome efficacy, and engagement in mitigation actions, including social-distancing, health behaviors and support for policies to mitigate COVID-19, followed by questions on beliefs about the existence and severity of COVID-19, and demographics (in US: age, gender, State [recoded into regions], party affiliation; in the Netherlands: age, gender).Footnote1 Both studies were approved by the ethical committee Psychology of the University of Groningen.

Participants

The United States

The original dataset contained 358 responses with complete data. We assessed data quality based on three key parameters: 1) attention checks within two different grid-style blocks of questions (i.e., a set of questions which were answered on the same scale, and which were presented immediately underneath each other in a grid) (47 respondents failed one or both attention checks), 2) invariance on grid-style questions (11 respondents did not vary on their answers within grids), and 3) time to fill out the survey (17 respondents did not finalize the survey between 5 and 60 minutes, which we regarded the absolute minimum and maximum time in which respondents would be able to realistically and accurately answer all questions). Respondents who failed one or more of these quality checks were removed from our analyses, resulting in a final sample size of 293. Age ranged from 18 to 78 years old; the mean age was 37.52 years, with a standard deviation of 12.68. In total 58% of our respondents indicated to be male, 41% to be female, and 3 respondents answered “other” or declined to answer. From our respondents, 101 lived in the South, 76 in the West, 61 in the North East, 49 in the Midwest region of the United States (regions according to US Federal Census Bureau), and six declined to answer. Further, 101 of our respondents indicated to be Democratic, 67 to be Republican, 62 to be Independent and 4 answered “other.”

The Netherlands

The original dataset contained 344 responses with complete data. We assessed data quality based on two key parameters: 1) invariance on grid-style questions (8 respondents did not vary in their answers within grids), and 2) time to fill out the survey (21 respondents did not finish the survey between 5 and 60 minutes). Respondents who failed one or more of these quality checks were removed from our analyses, resulting in a sample size of 316. In addition, we removed one respondent from our analyses who’s answers substantially deviated from all other respondents and who had a substantial impact on the effect sizes,Footnote2 resulting in a final sample size of 315. Age ranged from 17 to 87 years old; the mean age was 54.61 years, with a standard deviation of 17.58. About 50% of our respondents indicated to be male, 50% to be female, and 1 respondent declined to answer.

Measures

Worry about the impacts of COVID for different groups

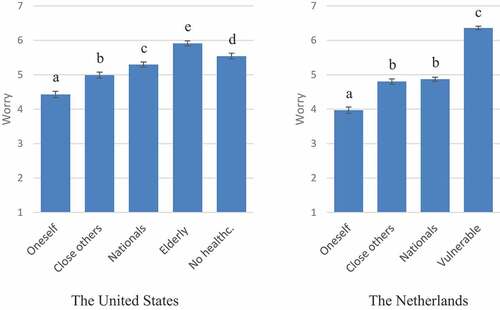

We measured worries about five specific groups in the United States, and about four specific groups in the Netherlands. In both countries, respondents were asked “How worried are you about the (potential) impacts of the coronavirus on … ” after which a list of groups was presented. For each group, the respondent could answer on a scale from 1 not at all to 7 extremely. In the United States, the groups were “me, personally” (M = 4.42, SD = 1.77), “my friends and family” (M = 5.03, SD = 1.71), “people in the US” (M = 5.31, SD = 1.42), “elderly people” (M = 6.00, SD = 1.46) and “people without healthcare” (M = 5.62, SD = 1.60); in the Netherlands, the groups were “me, personally” (M = 3.97, SD = 1.67), “my friends and family” (M = 4.80, SD = 1.41), “people in the Netherlands” (M = 4.87, SD = 1.13), and “vulnerable people” (M = 6.36, SD = 0.90). Hence, whereas in the United States we asked in two different items about elderly people and people without healthcare, in the Netherlands we only asked about “vulnerable” people. To address our research questions, we distinguished between “worries about oneself and close others” and “worries about distant others.”

Specifically, worry about oneself and close others was computed by taking the mean of the items “me, personally” and “my friends and family,” which correlated strongly with each other in both the United States (r = .66) and the Netherlands (r = .64), while both items correlated less strongly with the items measuring worry about distant others (US: .18 < rs < .52; NL: .34 < rs < .43), confirming the predefined theorized factor “self and close others” (Stuive, Citation2007). The mean score on worry about oneself and close others was 4.72 (SD = 1.58) in the United States, and 4.39 (SD = 1.39) in the Netherlands.

Worry about distant others was computed by taking the mean of the items “people in the US,” “elderly people” and “people without healthcare” in the United States, and between “people in the Netherlands,” and “vulnerable people” in the Netherlands, which all correlated strongly with each other (US: .60 < rs < .79; NL: r = .58), while these items correlated less strongly with items measuring worry about oneself and close others (US: .18 < rs < .52; NL: .34 < rs < .47), confirming the predefined factor “distant others” (Stuive, Citation2007). The mean score on worry about distant others was 5.78 (SD = 1.26) in the United States, and 5.61 (SD = 0.90) in the Netherlands.

Subjective wellbeing

Subjective wellbeing was measured with two items, which were included in a longer list of emotions for which respondents were asked to indicate on a 7-point scale “At this moment, to what extent do you feel … ” (1 not at all to 7 extremely). The items used for subjective wellbeing were “happy” and “satisfied,” which correlated strongly with each other (US, r = .78; NL, r = .51). The mean score on subjective wellbeing was 3.40 (SD = 1.77) in the United States, and 4.07 (SD = 1.26) in the Netherlands.

Personal norms to mitigate COVID-19

Personal norms to mitigate COVID-19 were measured with four items (adapted from Steg et al., Citation2011). Respondents were asked to indicate on 7-point scale to what extent they agreed with each item (1 strongly disagree to 7 strongly agree). The items were “I feel personally responsible to try to prevent the coronavirus from spreading,” “I feel guilty if I do not comply to (local, state, and federal) guidelines to prevent the coronavirus from spreading,” “I feel morally obligated to comply to the (local, state, and federal) guidelines to prevent the coronavirus from spreading to others,” and “Acting in-line with state and federal guidelines to prevent the coronavirus from spreading makes me feel like a better person.” The four items formed a reliable scale in both samples (US: α = .85; NL: α = .75); accordingly, we calculated the mean score of the four items (US: M = 5.54, SD = 1.46; NL: M = 5.75, SD = 1.09).

Actions to mitigate the COVID-19 crisis

Social-distancing

Social-distancing was measured with four items: “When I’m outside my home, I now keep a minimum of 6 feet [1.5 meters] from strangers and people I don’t know,” “When I’m outside my home, I now keep a minimum of 6 feet [1.5 meters] from people I do know,” “I now refrain from physical contact (e.g., shaking hands, playing sports) with strangers and people I don’t know” and “I now refrain from physical contact (e.g., shaking hands, playing sports) with people I do know.” Respondents indicated on a 7-point scale to what extent they performed each of these behaviors (1 Never to 7 Always). In both the United States and the Netherlands, the items formed a reliable scale (US: α = .84; NL: α = .82); accordingly, we calculated the mean score of the four items (US: M = 5.86, SD = 1.19; NL: M = 6.60, SD = 0.66).

Health behaviors

Health behaviors were measured with four items: “If I have to sneeze or cough, I do so into my elbow or use a tissue,” “I now always wash my hands after having been outside my home,” “If I came down with mild cold-like symptoms (e.g., running nose, sneeze), I would now stay at home” and “If I came-down with symptoms like fever or coughing, I would now stay at home.” Respondents indicated on a 7-point scale to what extent they performed these behaviors (1 Never to 7 Always). In both the United States and the Netherlands, the items formed a reliable scale (US: α = .77; NL: α = .60). Accordingly, we calculated the mean score of the four items (US: M = 6.26, SD = 0.97; NL: M = 5.92, SD = 1.06).

Support for policies to mitigate COVID-19

Due to the different situations and debates in both countries, we developed items measuring policy support for each country specifically. In the United States respondents were asked to indicate on a 7-point scale (1 not support at all to 7 fully support) to what extent they support each of the following four policies “Closing non-essential businesses (like bars and restaurants) and schools,” “Countries closing borders and restricting international travel,” “Free and widely available testing for the coronavirus,” “Free treatment and vaccines (once available) for the coronavirus.” The four formed a reliable scale, so we computed the mean score on the items (α = .83, M = 6.21, SD = 1.09).

In the Netherlands respondents were asked to indicate on a 7-point scale (1 not support at all to 7 fully support) to what extent they support each of the following six policies “Closing bars and restaurants,” “Closing schools,” “Closing shops (excluding shops for essentials),” “Countries closing borders and restricting international travel,” “Prohibiting healthy people to go outside for pleasure” and “Prohibiting social gatherings.” The six items formed a reliable scale, so we computed mean scores on the items (α = .77, M = 6.10, SD = 0.97).

Data analyses

All analyses were performed with IBM SPSS Statistics 26. We used paired-samples t-tests to explore whether individuals worried more about the impact of COVID-19 for distant others than for themselves and close others, respectively. We used multiple linear regression analyses to test Hypotheses 1 that stronger worries about oneself and close others are associated with stronger engagement in mitigative actions, Hypothesis 2 that stronger worries about distant others are associated with stronger engagement in mitigative actions, and Hypothesis 3 that the relationships between both worries and mitigative action are mediated by strengthened personal norms. Assumption checks did not indicate serious violations. As the methods and analyses were close to identical in our two samples, we discuss both samples next to each other in a single results section. We refrained from making explicit statistical comparisons between countries because our samples were not national representative and because we did not formulate hypotheses about between-country differences. Rather we expect the relationships between variables to be similar across samples and countries.

Results

Comparing worries about self and close others with worries about distant others

In line with polling data on COVID-19 related concerns (Ipsos, Citation2020a; Pew Research Center, Citation2020a; Wise et al., Citation2020), paired-samples t-tests indicated that in both samples respondents worried significantly more about the impact of COVID-19 for distant others than for themselves and close others. Specifically, in the United States the mean difference was 1.06 (SD = 1.54), which was statistically significant, t(292) = 11.75, p < .001, with a 95% confidence interval ranging from 0.88 to 1.24. For the Netherlands, the mean difference was 1.23 (SD = 1.22), which was statistically significant at t(314) = 17.86, p < .001, with a 95% confidence interval ranging from 1.09 to 1.36. A more detailed inspection of the scores for each specific group indicated that respondents generally worried the least about consequences for themselves, about equally about consequences for close others and national citizens, and most strongly about vulnerable populations (see ).

The relationships between different worries and personal norms and mitigative actions

The bivariate zero-order correlations presented in show that the more people worry about the impact of COVID-19 for oneself and close others (supporting Hypothesis 1), and for distant others (supporting Hypothesis 2), the more they engaged in mitigative actions and supported mitigation policy. Moreover, stronger worries about the impacts of COVID-19 for oneself and close others, and for distant others, were correlated to stronger personal norms to take mitigative actions.

Table 1. Bivariate correlations between worry about self and close others, worry about distant others, personal norms, social distancing, health behaviors and policy support. Coefficient above the diagonal are for the sample of United States citizens, coefficients below the diagonal are for the sample of Dutch citizens.

shows the results of the regression analyses with both types of worry as predictor variables, and personal norms, social distancing, health behaviors, and policy support as outcome variables. The results reveal that worry about distant others explained unique variance in all outcome variables in both countries, with stronger worrying being indicative for stronger personal norms, more social distancing, more health behaviors, and more policy support.

Table 2. Regression coefficients for the predictors worry about self and close others and worry about distant others with the outcome variables personal norms (mediator), social distancing, health behaviors (i.e., self-quarantining and hygiene practices) and policy support.

The unique association of worry about oneself and close others with mitigative actions was less consistent, though generally positive. In the United States, worry about oneself and close others explained unique variance in social distancing, but not in health behaviors and policy support. In the Netherlands, worry about oneself and close others explained unique variance in health behaviors and policy support, but not in social distancing. Worry about oneself and close others did in both countries explain unique variance in personal norms, with stronger worrying about oneself and close others being indicative of stronger personal norms.

Critically, our regression model comprising of only two types of worry was able to explain substantial amounts of variance in all outcome variables, in particular in the United States. This shows that worry is an important predictor of individuals’ (support for) actions to mitigate COVID-19 and our hypothesized mediator variable personal norms.Footnote3

The mediating role of personal norms

Supporting Hypothesis 3, the relationship between both types of worry and mitigative actions and policy support was partly mediated by personal norms. That is, when personal norms were added to the regression model comprising both types worry, the effects of worry about oneself and close others, and about distant others, on mitigative actions and policy support reduced. Moreover, personal norms appeared a very strong predictor of mitigative actions and policy support (see ).

Table 3. Regression coefficients for the predictors worry about self and close others and worry about distant others with the outcome variables personal norms, social distancing, health behaviors (i.e., self-quarantining and hygiene practices) and policy support.

Specifically, worry about consequences for self and close others was, via personal norms, positively indirectly associated with social distancing (US: 1*3 = .10, 95%CI = .04; .18, NL:

1*3 = .05, 95%CI = .00; .11), health behaviors (US:

1*3 = .08, 95%CI = .03; .13, NL:

1*3 = .04, 95%CI = .00; .09) and policy support (US:

1*3 = .08, 95%CI = .03; .13, NL:

1*3 = .04, 95%CI = .00; .09). Next to this indirect association, worry about consequences for self and close others was directly, negatively associated with health behaviors and policy support in the United States, and directly, positively associated with health behaviors and policy support in the Netherlands (see

4, ). In both countries, we did not observe a significant direct relationship between worry about oneself and close others and social distancing, suggesting that personal norms fully mediated these relationships.

Worry about distant others was, via personal norms, positively indirectly associated with social distancing (US: 2*3 = .22, 95%CI = .14; .31, NL:

2*3 = .14, 95%CI = .07; .23), health behaviors (US:

2*3 = .17, 95%CI = .10; .25, NL:

2*3 = .11, 95%CI = .04; .19) and policy support (US:

2*3 = .18, 95%CI = .10; .27, NL:

2*3 = .11, 95%CI = .06; .18). Next to this indirect association, worry about consequences for distant others was uniquely, directly, positively associated with social distancing, health behaviors and policy support in the United States, and with social distancing and policy support in the Netherlands (see

5, ). Yet, the direct relationship between worry about distant others and health behaviors in the Netherlands was no longer statistically significant, suggesting personal norms fully mediated this relationship.

Worries and subjective wellbeing

We next explored whether worries may also have negative outcomes. Specifically, we tested whether stronger experiences of worry about self and close others, and for distant others, were associated with a lower subjective wellbeing. Interestingly, we only found a weak negative bivariate correlation between worry about oneself and close others and subjective wellbeing in the Dutch sample (r = −.13, p = .025), whereas all other correlations between worry and subjective wellbeing did not reach statistical significance (rs −.11 to .05, all ps > .05). This suggests that only stronger worries about oneself and close others were associated with a more deprived wellbeing, although this relationship was weak and not consistent across countries. Follow-up regression analyses with both types of worry as predictor variables showed similar patterns, with only more worrying about oneself and close others being related to a slightly lower subjective wellbeing (see ).

Table 4. Regression coefficients for the predictors worry about self and close others and worry about distant others with the outcome variables personal norms (mediator), social distancing, health behaviors (i.e., self-quarantining and hygiene practices) and policy support.

Discussion

Our data clearly shows the relevance of worrying about consequences of COVID-19 for oneself and close others and – in particular – distant others in explaining individuals’ support for and engagement in actions to mitigate COVID-19. Specifically, stronger worries about consequences for oneself and close others, as well as stronger worries about consequences for distant others, were correlated to stronger support for and engagement in actions to mitigate COVID-19, supporting our Hypothesis 1 and Hypothesis 2, respectively. Moreover, as expected, personal norms partially mediated the relationships between both types of worry and policy support and mitigative actions, providing support for our Hypotheses 3. Specifically, the stronger individuals experienced each type of worry, the stronger their personal norms to take mitigative actions, which in turn was related to more social-distancing, health behaviors, and support for COVID-19 mitigative policies. In addition to these indirect effects, stronger worries about distant others were also directly related to stronger engagement in social distancing, health behaviors, and policy support in the United States, and to social distancing, policy support, but not health behaviors, in the Netherlands. Further, stronger worries about oneself and close others, were directly related to stronger engagement in health behaviors and policy support in the Netherlands, but surprisingly to weaker engagement in health behaviors and policy support in the United States.

Theoretical implications

Our findings have clear implications for theory on the role of worry in promoting actions to mitigate crises, extending current understanding within the health domain with literature on responses to global environmental crises (Bouman, Steg, Dietz et al., Citation2021). Specifically, we argued and found that people not only worry about consequences of COVID-19 for themselves and close others, which are typically studied within the health domain (Cameron & Reeve, Citation2006; Diefenbach et al., Citation1999; Petrocchi et al., Citation2021; Sobkow et al., Citation2020), but also worry about consequences of COVID-19 for more distant others, which are more frequently studied in the context of global environmental crises (Schultz, Citation2001; Steg et al., Citation2011). Importantly, we observed that worries about consequences of COVID-19 for distant others were not only stronger than worries about consequences for oneself and close others, but were also more indicative of individuals’ support for and engagement in mitigative actions. Thereby, we provide new support for current theorizing that many individuals strongly care about and are driven by the interests of others and society more broadly, which has been argued to largely underlie individuals’ responses to global environmental crises (Bouman & Steg, Citation2019; Schultz, Citation2001; Schwartz, Citation1977; Steg et al., Citation2011; Stern, Citation2000), and which thus seem to apply to the health domain as well (cf. Bouman, Steg, Dietz et al., Citation2021; Pfattheicher et al., Citation2020).

In addition, again applying theories on responses to global environmental crises to the health domain, we gathered new insights in the processes through which both types of worry about consequences of COVID-19 relate to mitigative actions and policy support. Specifically, in line with the Value Belief Norm theory (Stern, Citation2000) and the Norm Activation Model (Schwartz, Citation1977), our findings show that personal norms play an important role in translating more abstract psychological factors – in our case worries – into more concrete actions. Hence, our findings show that research in environmental psychology on global environmental crises may help understand individuals’ responses to global crises in the health domain, such as pandemics.

Importantly, our focus on worry as a predictor of personal norms also extends research on the Norm Activation Model (Schwartz, Citation1977) and Value Belief Norm theory (Stern, Citation2000). Traditionally, this research argues that values (i.e., general and desirable life goals) and more cognitive factors (e.g., awareness of consequences) underlie personal norms. We however showed support for a more affective route toward mitigative actions, which may supplement the more frequently studied cognitive route toward mitigative actions.

Our relatively simple model – comprising of worry about consequences for self and close others, worry about consequences for distant others, and personal norms (see ) – was able to explain substantial amounts of variance in individuals’ mitigative actions and support for mitigation policy. Moreover, the direction of the observed relationships was highly consistent across the United States and the Netherlands. Only the direction of the unique direct effect of worry about oneself and close others on health behaviors and policy support varied between the two countries, and this variation only occurred when controlling for personal norms and worry about distant others. The consistency of our findings suggests that our conclusions likely generalize across countries. Yet, it is important to note that effect sizes were substantially larger in our US sample than in our Dutch sample, which could be further investigated by future research.

Interestingly, both types of worry were hardly related to subjective wellbeing. Specifically, only stronger worrying about oneself and close others was – though very weakly – associated with a lower subjective wellbeing, whereas for worrying about distant others no such relationship was observed. If anything, this implies that worrying about distant others may not only be more motivational than worrying about oneself and close others, but may also be less harmful to individuals’ subjective wellbeing.

Practical implications

Our findings have important practical implications. The observation that particularly worries about consequences for distant others are consistently and strongly positively related to individuals’ support for and engagement in actions to mitigate COVID-19 suggests that strengthening such worries may be an effective strategy to promote actions to mitigate COVID-19, more so than emphasizing worries about oneself and close others. Strategies to promote mitigative actions could for instance, focus on making individuals more aware of the consequences of COVID-19 for distant groups, and aim to strengthen an emotional connection with those groups, which together likely strengthen worries about distant others. Arguably, such interventions may also be less susceptible to optimism biases and denial of the problem, which are often observed when individuals are confronted with risks to themselves and may withhold them from problem-focused coping (cf. Taylor, Landry, Paluszek, Rachor et al., Citation2020).

Our findings also highlight the potentially important role personal norms may play in motivating mitigative actions. Strengthening feelings of personal responsibility and moral obligation to take mitigative actions may therefore be an important strategy to promote widespread engagement in mitigative actions. This could for instance, be achieved by highlighting the relevance of individuals’ behaviors and increasing individuals’ agency to take action (cf. Bouman, Steg, Dietz et al., Citation2021), next to strengthening individuals’ worries about consequences of COVID-19.

Limitations and future research

We identified two limitations of our studies. First, the correlational design of our studies disabled us from making causal inferences. However, since the hypothesized relationships are strongly theory-driven and supported by research in environmental psychology that used experimental designs, we are relatively confident about our proposed theoretical model. Second, our study used convenience samples (i.e., MTurk and Thesistools Pro). Yet, the samples used in our study are typically considered more representative than other commonly employed sampling methods, such as snowballing or mail-lists (Dworkin et al., Citation2016), and means in our samples correspond to representative polling data (Ipsos, Citation2020a; Pew Research Center, Citation2020a). In addition, we do not see any theoretical grounds to argue that the hypothesized directions of the relationships would vary across populations. Indeed, we observed similar relationships across both samples, also when controlling for demographic variables (see footnote 1), suggesting that our findings are generalizable across countries and populations (cf. Bhushan et al., Citation2019). Yet, more research is needed to test the causality and generalizability of the proposed relations.

Future research could also further investigate the processes through which worries relate to mitigative actions. Our findings indicate that personal norms likely explain part of this process, but other variables may also play a role as mediator or moderator variables. For example, self-efficacy (i.e., one’s ability to take the necessary actions) may be critical for individuals to be able to translate their worries into concrete actions (e.g., Rimal & Real, Citation2003). In addition, research could investigate what underlies individuals’ worries, in particular whether differences between worries about consequences for oneself and others reflect individuals’ prosocial tendencies, an optimism bias, or both, and whether this may influence the extent to which worries affect mitigative actions (cf. Bouman, Steg, Perlaviciute et al., Citation2021; Wise et al., Citation2020).

Another promising avenue for future research may be to inspect the hypothesized relationships over the course of the pandemic. Our data was collected relatively early in the pandemic (March 2020) and individuals’ perceptions of COVID-19 and responses to it may have changed over time. For example, more recent vaccination programs may have reduced worries about the consequences of COVID-19. Moreover, because many countries started with vaccinating vulnerable populations, perceptions of who are most at risk of COVID-19 may have changed over time, possibly also affecting feelings of worry (e.g., people may worry less about populations that are at risk of COVID-19 due to personal choices, such as not getting vaccinated or not complying to COVID-19 measures). However, despite these possible changes in the levels of experienced worry, we expect the hypothesized and observed relationships between worry and mitigative actions to remain constant. Yet, we can imagine the weak negative relationship between subjective wellbeing and worry about consequences for oneself and close others to grow stronger over time, in particular because worrying seems most detrimental when experienced for longer periods of time (Ruscio et al., Citation2001).

Lastly, future research could test whether our proposed process generalizes to other crises, threats, or situations. Similar processes may likely occur for other global health crises, such as other pandemics, as well as large-scale disasters (e.g., tsunamis), threats (e.g., nuclear energy) or attacks (e.g., terrorist attacks) where larger groups of people are at risk of experiencing severe consequences. Interestingly, similar processes may also occur for more personal behaviors that also have clear impacts on others’ health, such as smoking. Further, the proposed processes could be used to explain why individuals may not engage in mitigative actions because the mitigative actions may be perceived as a threat themselves (Kulesza et al., Citation2020). Specifically, individuals who worry about the consequences of mitigative actions for people’s wellbeing, health or finances, may experience stronger personal norms to oppose to these mitigative measures and, therefore, not engage in and support such actions.

Conclusion

In sum, in two studies we found strong support for our proposition that stronger worries about consequences of COVID-19, in particular for distant others, are related to more support for and engagement in actions to mitigate COVID-19. Moreover, these relationships seem to largely occur by strengthening personal norms to act. Remarkably, worry about the risks of COVID-19 for distant others appeared more strongly and more consistently related to personal norms, mitigative actions, and policy support than worries about oneself and close others. Here, it is important to note that individuals also appeared to worry more about consequences of COVID-19 for distant others than for themselves, and may thus provide a strong incentive for mitigative actions. These findings suggest that policy to motivate people to support and take the actions needed to mitigate COVID-19 could focus on strengthening worries about consequences for distant others, which appears to be a key motivator of mitigative actions.

Acknowledgments

We thank Stephanie Johnson Zawadzki for proofreading an early version of the manuscript, and Madeline Gerda Langley for her assistance with the literature review.

Data availability

Data and analyses presented in this manuscript are available at https://osf.io/am6ew/

Disclosure statement

The authors confirm that there are no relevant financial or non-financial competing interests to report.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. We performed all analyses with and without including demographics as covariates. We only report the analyses without demographics because the inclusion of the demographics did not affect our conclusions. Moreover, we did not formulate hypotheses about the impact of demographics on mitigative actions, and none of the demographics was consistently related to any of our outcome variables. For analyses with demographics as covariates, see: https://osf.io/am6ew/.

2. This respondent indicated COVID-19 was a hoax and therefore indicated to not worry about COVID-19 at all, to not feel a personal norm, and to not support any of the mitigative measures. The scores of this respondent substantially differed from all other respondents and inclusion of this respondent in our analyses strongly inflated all effect sizes. This is why we decided to present the more conservative analyses excluding this respondent’s data, as we believe conclusions from this dataset better reflect the general population.

3. A reviewer wondered whether both types of worries would interact in influencing the outcome variables. Although we did not hypothesize such an interaction effect, we explored whether both types of worries interacted following the Reviewer’s request. The interaction effect was only significant for the mediator personal norms and the outcome variable health behaviors in the US sample, and not for social distancing and policy support. In the Dutch sample, no interaction effect reached statistical significance. In the two cases where the interaction effect was significant, the effect of worry about distant others on the outcome variables was slightly larger when worry about oneself and close others was low (and vice versa). Because we (a) did not hypothesize interaction effects beforehand, (b) most interaction effects were not statistically significant, and (c) the inclusion of interaction effects in our models did not alter any of our conclusions, we decided to not report interaction effects in the main text. For analyses with interaction effects included, see: https://osf.io/am6ew/.

References

- Bhushan, N., Mohnert, F., Sloot, D., Jans, L., Albers, C., & Steg, L. (2019). Using a gaussian graphical model to explore relationships between items and variables in environmental psychology research. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1050. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01050

- Bouman, T., & Steg, L. (2019). Motivating society-wide pro-environmental change. One Earth, 1(1), 27–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oneear.2019.08.002

- Bouman, T., Steg, L., & Dietz, T. (2021). Insights from early COVID-19 responses about promoting sustainable action. Nature Sustainability, 4(3), 194–200. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-020-00626-x

- Bouman, T., Steg, L., & Perlaviciute, G. (2021). From values to climate action. Current Opinion in Psychology, 42, 102–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.04.010

- Bouman, T., Verschoor, M., Albers, C. J., Böhm, G., Fisher, S. D. S. D., Poortinga, W., Whitmarsh, L., & Steg, L. (2020). When worry about climate change leads to climate action: How values, worry and personal responsibility relate to various climate actions. Global Environmental Change, 62, Article 102061. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2020.102061

- Cameron, L. D., & Reeve, J. (2006). Risk perceptions, worry, and attitudes about genetic testing for breast cancer susceptibility. Psychology and Health, 21(2), 211–230. https://doi.org/10.1080/14768320500230318

- Diefenbach, M. A., Miller, S. M., & Daly, M. B. (1999). Specific worry about breast cancer predicts mammography use in women at risk for breast and ovarian cancer. Health Psychology, 18(5), 532–536. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.18.5.532

- Dworkin, J., Hessel, H., Gliske, K., & Rudi, J. H. (2016). A comparison of three online recruitment strategies for engaging parents. Family Relations, 65(4), 550–561. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12206

- Harper, C. A., Satchell, L. P., Fido, D., & Latzman, R. D. (2020). Functional fear predicts public health compliance in the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 68(1), 7–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-020-00281-5

- Ipsos. (2020a). Coronavirus: Opinion and reaction. https://www.ipsos.com/en-pk/coronavirus-opinion-and-reaction-results-multi-country-poll-feb-2020

- Ipsos. (2020b). What worries the world. https://www.ipsos.com/en/what-worries-world-november-2020

- Jetten, J., Reicher, S. D., Haslam, A., & Cruwys, T. (2020). Together apart: The psychology of COVID-19. SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Kulesza, W., Doliński, D., Muniak, P., Derakhshan, A., Rizulla, A., & Banach, M. (2020). We are infected with the new, mutated virus UO-COVID-19. Archives of Medical Science, 17(6), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.5114/aoms.2020.99592

- Petrocchi, S., Iannello, P., Ongaro, G., Antonietti, A., & Pravettoni, G. (2021). The interplay between risk and protective factors during the initial height of the COVID-19 crisis in Italy: The role of risk aversion and intolerance of ambiguity on distress. Current Psychology, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01601-1

- Pew Research Center. (2020a). COVID-19: Views of outbreak impact. https://www.pewresearch.org/pathways-2020

- Pew Research Center. (2020b). Election news pathways 2020. https://www.pewresearch.org/pathways-2020/

- Pfattheicher, S., Nockur, L., Böhm, R., Sassenrath, C., & Petersen, M. B. (2020). The emotional path to action: Empathy promotes physical distancing and wearing of face masks during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychological Science, 31(11), 1363–1373. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797620964422

- Rimal, R. N., & Real, K. (2003). Perceived risk and efficacy beliefs as motivators of change. Human Communication Research, 29(3), 370–399. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.2003.tb00844.x

- Ruscio, A. M., Borkovec, T. D., & Ruscio, J. (2001). A taxometric investigation of the latent structure of worry. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 110(3), 413–422. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.110.3.413

- Schmiege, S. J., Bryan, A., & Klein, W. M. P. (2009). Distinctions between worry and perceived risk in the context of the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 39(1), 95–119. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2008.00431.x

- Schultz, P. W. (2001). The structure of environmental concern: Concern for self, other people, and the biosphere. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 21(4), 327–339. https://doi.org/10.1006/jevp.2001.0227

- Schwartz, S. H. (1977). Normative influences on altruism. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 10, 221–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60358-5

- Sebri, V., Cincidda, C., Savioni, L., Ongaro, G., & Pravettoni, G. (2021). Worry during the initial height of the COVID-19 crisis in an Italian sample. Journal of General Psychology, 148(3), 327–359. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221309.2021.1878485

- Smith, N., & Leiserowitz, A. A. (2014). The role of emotion in global warming policy support and opposition. Risk Analysis, 34(5), 937–948. https://doi.org/10.1111/risa.12140

- Sobkow, A., Zaleskiewicz, T., Petrova, D., Garcia-Retamero, R., & Traczyk, J. (2020). Worry, risk perception, and controllability predict intentions toward COVID-19 preventive behaviors. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 3226. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.582720

- Steg, L. (2016). Values, norms, and intrinsic motivation to act proenvironmentally. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 41(1), 277–292. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-110615-085947

- Steg, L., de Groot, J. I. M., Dreijerink, L., Abrahamse, W., & Siero, F. (2011). General antecedents of personal norms, policy acceptability, and intentions: The role of values, worldviews, and environmental concern. Society & Natural Resources, 24(4), 349–367. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920903214116

- Stern, P. C. (2000). New environmental theories: Toward a coherent theory of environmentally significant behavior. Journal of Social Issues, 56(3), 407–424. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-4537.00175

- Stern, P. C., & Dietz, T. (1994). The values of basis of environmental concern. Journal of Social Issues, 50(3), 65–84. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.1994.tb02420.x

- Stuive, I. (2007). A comparison of confirmatory factor analysis methods: Oblique multiple group method versus confirmatory common factor method [Doctoral Dissertation, University of Groningen]. RUG Repository. https://research.rug.nl/en/publications/a-comparison-of-confirmatory-factor-analysis-methods-oblique-mult

- Taylor, S., Landry, C. A., Paluszek, M. M., Fergus, T. A., McKay, D., & Asmundson, G. J. G. (2020). COVID stress syndrome: Concept, structure, and correlates. Depression and Anxiety, 37(8), 706–714. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.23071

- Taylor, S., Landry, C. A., Paluszek, M. M., Rachor, G. S., & Asmundson, G. J. G. (2020). Worry, avoidance, and coping during the COVID-19 pandemic: A comprehensive network analysis. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 76, Article 102327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102327

- Van der Linden, S. L. (2017). Determinants and measurement of climate change risk perception, worry, and concern. Oxford Research encyclopedia of climate change communication. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228620.013.318

- Verplanken, B., Marks, E., & Dobromir, A. I. (2020). On the nature of eco-anxiety: How constructive or unconstructive is habitual worry about global warming? Journal of Environmental Psychology, 72, Article 101528. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2020.101528

- Wise, T., Zbozinek, T. D., Michelini, G., Hagan, C. C., & Mobbs, D. (2020). Changes in risk perception and self-reported protective behaviour during the first week of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. Royal Society Open Science, 7(9), Article 200742. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.200742

- World Health Organization. (2020). Coronavirus disease 2019. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019