ABSTRACT

In this article, we examine how humor practices on Twitter resist dominant emotion norms during an emerging disease outbreak. Humor may seem frivolous or irreverent but can constitute a powerful practice for channeling and managing difficult emotions – like anxiety and fear – during an outbreak. We find that the use of AAVE (African-American Vernacular English) and Black cultural references were widespread in Ebola-related tweets using humor. Together these communicative practices constitute Black Twitter. Humor can signal membership in Black culture while also performing and managing specific emotions in relation to epidemic risk in online spaces. Humor practices on Black Twitter were more likely to reimagine social connections despite the risks posed by the epidemic, whereas mainstream forms of humor emphasized retreat and self-isolation in response to an epidemic threat. These findings center the agency and creativity of this influential digital community while showing the variability of communication practices among a group facing disproportionate vulnerability to outbreaks and public health threats. The implications for public health messaging are discussed.

COVID-19 is now the most widespread and deadliest pandemic to occur in the digital age.Footnote1 The outbreak has disproportionately affected structurally disadvantaged groups, including racial minorities in the U.S. (Tai et al., Citation2021). In the not too distant past—2014—it was Ebola that gripped the international community, while being concentrated in West Africa (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Citation2015). Despite the alarming number of cases and deaths in West Africa at the time, international interest in Ebola did not peak until the first case arrived in the U.S. on 30 September 2014. Following the first U.S. case, the outbreak brought round-the-clock news coverage in news outlets (Ihekweazu, Citation2017) and renewed scholarly interest in the opportunities, costs, and effects of new forms of media during epidemics (Chan, Citation2015; Odlum, & Yoon, Citation2015; Sastry, & Dutta, Citation2017; Sastry, & Lovari, Citation2017).

Social media practices are of growing interest to scholars studying both public health issues (Chew, & Eysenbach, Citation2010; Lazard et al., Citation2015) and emotions (Döveling et al., Citation2018; Rogers, & Robinson, Citation2014). In this study, we integrate literature on digital communities and emotion in order to examine Twitter as a site where digital practices push against dominant feeling rules (Hochschild, Citation1979)—expectations for what to feel and how to express it – during an epidemic. Specifically, we integrate a digital affect framework (Döveling et al., Citation2018) with the sociology of emotion to understand the communication and uses of humor on Twitter. This integrated framework centers on emotion practices as resources for creating and maintaining digital subcultures. Humor was the dominant theme in Twitter reactions to Ebola, defying “hegemonic stories” (Sastry, & Dutta, Citation2017, p. 12) that portrayed social media as vectors of fear (Chan, Citation2015) and “ontological narratives” of contagious disease as singly marked by fear (Sastry, & Lovari, Citation2017, p. 329).

Use of African-American Vernacular English (AAVE), Black cultural references, and the popularity of certain tweets among Black users – together what scholars refer to as Black Twitter (Graham, & Smith, Citation2016; Maragh, Citation2018)—characterized many popular cases of Ebola humor. Critical race scholars studying social media note that online humor and wit “at times may seem frivolous to the uninitiated” but are “a powerful resource for signaling racial identity” (Florini, Citation2014, p. 224). We add to this scholarship by analyzing the unexpected role of humor in online responses to an epidemic. Humor and wit are not only powerful resources for laying claim to subcultural and racial identities, but humor practices on social media can also provide the emotional resources (Cottingham, Citation2016)—as energy, hope, solidarity, and belonging (Döveling et al., Citation2018)—needed in the context of an evolving and uncertain biomedical threat. In this article we ask the following questions:

What humor practices were taken up by mainstream and Black Twitter in response to the Ebola outbreak?

What role did these humor practices play in the context of the Ebola outbreak and in the influential digital culture of Black Twitter?

Twitter and Black Twitter

The social media platform Twitter had over 300 million monthly users in 2019, up from 288 million monthly users in 2014. Footnote2 Twitter users interact through tweets and by retweeting, replying, and/or liking (signified as heart icons) the tweets of others in their network (other users they follow). Diverse publics can react to current news in an informal way, but using a platform like Twitter often requires understanding and adopting new norms of interaction and systems of communication in line with these “economies of laughter” (Henefeld, Citation2016). Twitter is a “participatory media environment” that can encompass “wit, parody, sarcasm, co-optation, and playful memification” (Davis et al., Citation2018, p. 3900). Humor practices are pervasive on social media sites. For example, in the case of COVID-19, social media was used to spread playful public service announcements on handwashing (Wamsley, Citation2020), comedic ridicule of toilet paper shortages (Rodd, Citation2020), and a remix of the 1990s hit “Back that Thang Up” to “Vax that Thang Up.”Footnote3 These posts were then covered in conventional news outlets, illustrating the evolving interplay of social and news media economies as digital practices develop.

In analyses of social media, Black Twitter has emerged as a meaningful reference category to delineate both a community and communicative style that is “part cultural force, cudgel, entertainment, and refuge” (McDonald, Citation2014). The term applies to interactions on the platform marked by the use of AAVE (African-American Vernacular English), with reference to events and moments salient to the Black community, and references to Black cultural practices. It is influential in shaping discussions of contemporary politics both among Black social media users and in broader publics (Graham, & Smith, Citation2016). On Black Twitter, shared understanding comes from situated knowledge (Collins, Citation2000) and shared mundane and political experiences. These experiences enhance solidarity with similar others in digital spaces and allow users to connect through a shared racial identity (Maragh, Citation2018). While Black Twitter is an important digital space for organizing and resisting anti-Black violence in the U.S. (Brown et al., Citation2017; Ince et al., Citation2017), it is also a space for fighting against “respectability politics”—a political strategy emphasizing the need for Black people to emulate white appearance and comportment in order to be granted full rights as citizens (Hill, Citation2018).

Digital practices on Black Twitter can include using humor and joy as resistance to dehumanization (Lu, & Steele, Citation2019) and ‘enactments of “sass” and “shade” as affective strategies of social scrutiny’ (Monk-Payton, Citation2017, p. 15). One key humor practice is signifyin’ (Florini, Citation2014, p. 224), which includes “dissing” and “roasting”—the mockery of others that signals insider status and generates connection. While signifyin’ is primarily seen as a “game of insults … [it] is better understood as a celebration of invention, timeliness, and delivery in a discourse style intended to speak truth to power” (Brock, Citation2009, p. 17). Roasting can target Black celebrities and public figures. For example, in 2010, young rapper Lil’ Mama was mocked for her hair style with the creation of the hashtag #lilmamasweave. Users exchanged commentary, aiming for the funniest dis:

“in Da Bible #lilmamasweave was Da FiRE buSH dAt sp0kE 2 M0SES” (Florini, Citation2014, p. 231).

Roasting overlaps with mainstream entertainment and social media use (Kies, Citation2021), and can be taken up by corporations who profit from it as a resource-rich cultural practice (Dynel, Citation2020). Building on the scholarship on Black Twitter, Hill (Citation2018, p. 297) calls for more “empirical insight into the complex range of rituals, practices, ideologies, and productions of Black Twitter.” Examining humor during a public health crisis can deepen understanding of Black Twitter while also highlighting the forms and roles that humor can serve in the context of an outbreak.

Humor and digital affect cultures

Social scientists have examined humor in groups (Fine, & DeSoucey, Citation2005), in coping with difficult emotions (Francis, Citation1994), and as a mechanism for maintaining social boundaries (Kuipers, Citation2008). Solidarity among a group and coping with difficult situations are two possible outcomes of humor. Humor and joking can create psychological distance from a threatening event or outcome (Liberman, & Trope, Citation2008, p. 1201) and can manage death-related anxieties. Humor diffuses otherwise threatening or emotionally difficult scenarios, rendering them less threatening to a group (Elgee, Citation2003). For example, Cain (Citation2012) analysis of gallows humor in the back stages of hospice work suggests that nurses use humor to distance themselves both from death and from unhelpful physicians, portraying themselves as especially enlightened when it comes to death.

Certain types of humor can also be used to rebel against mass media attempts “to prescribe audience’s reactions” (Kuipers, Citation2005, p. 72). In Kuipers’ research on responses to the World Trade Center attack, she finds examples of disaster humor that do not fit an explanation of coping since they invoked graphic depictions that appeared to be as disturbing as the initial event. Kuipers argues that disaster humor serves a myriad of different functions: “The worldwide popularity of 9/11 jokes indicates that coping might not be the prime function of these jokes. Especially for those more distant from the event, such jokes might provide very different pleasures” (Kuipers, Citation2005, p. 71). The expected emotion norms (or “feeling rules,” Hochschild, Citation1979) of a national tragedy or public health threat would suggest feelings of grief, sorrow, or fear (Oh et al., Citation2021; Recuber, Citation2016). Visceral or “scripted fear” is nearly synonymous with contagious outbreaks like Ebola (Sastry, & Lovari, Citation2017). Rebelling against expectations about what to feel and how to express those feelings through irreverent humor might create digitally shared pleasure in reaction to decidedly unpleasant events.

Teasing apart the rebellious, ambivalent, and solidarity-building aspects of humor practices requires knowledge of both the context of the outbreak and the layered symbolic meanings used in memes – images combined with text circulated digitally (Julien, Citation2015). Specialized language, images of celebrities, and shared templates for developing jokes can come together in a single meme (often connected to current events) that functions both to share information and foster feelings of belonging among members of a subculture – those who are “in” on the joke (Julien, Citation2015). Humor is a key practice for creating and maintaining digital subcultures.

Digital subcultures are sites where both dominant emotion norms can be shared as well subverted. Integrating Döveling et al.’s (Citation2018) framework of digital affect culture with the sociology of emotion merges two parallel but compatible developments in sociology and communication scholarship. Digital affect culture theorizes members as participants who can manage emotions in line with social expectations and/or rebel against those expectations. Emotions, in line with a sociological perspective, are something “people do instead of have” and constitute a “socio-historical performance that spans not only the individual but also time and space as it invites new participants as it travels the digital terrains” (Döveling et al., Citation2018, p. 1, 3). Social media spaces, such as Twitter, “offer a unique platform” (Döveling et al., Citation2018, p. 2) for contesting emotion norms, especially during highly disruptive events like an epidemic. A digital affect framing is compatible with other culture-centered approaches (Sastry, & Dutta, Citation2017). In focusing on Black Twitter, we examine practices of agency and creativity among a marginalized group (Sastry, & Dutta, Citation2017, p. 11), albeit one geographically distant from the epidemic’s center. Based on this framing of emotions as cultural practices and Black Twitter as a digital affect culture, we examine how Black Twitter humor differs from mainstream practices in response to the 2014 Ebola outbreakFootnote4 and the role humor served in the context of an evolving health threat.

Methods

Twitter provides real-time data that are “both fine-grained and massively global in scale” (Golder, & Macy, Citation2011). While health scholars have used Twitter for surveillance (Odlum, & Yoon, Citation2015), scholarship that qualitatively addresses the varied emotional aspects of social media use are only beginning to emerge (Brownlie, & Shaw, Citation2019; Döveling et al., Citation2018; Stage, & Hougaard, Citation2018). In sampling tweets, we used 30 September 2014—the day of the first U.S. Ebola case – as a focal point, similar to other scholarship on Ebola (Ihekweazu, Citation2017). Tweets were sampled the week before and the week after September 30. Sifter, a Twitter archive service, estimated 705,000 Ebola-related tweets the week before (9/23/14 – 9/29/14) and 6,118,000 the week after (9/30/2014 - 10/6/2014). This 768% increase suggests that this date was indeed a turning point in the global Ebola conversation. Drawing a sample of 1% of tweets the week before and after September 30th allows for broad variation in the type of tweets captured while also approaching a level small enough to allow for interpretive coding of emotions (Brownlie, & Shaw, Citation2019). Coding began with a sample of 3,906 tweets from week one and 44,049 tweets in week two. A second random subsample was taken (1000 from week one and 1200 from week two) to calculate the level of interrater reliability (discussed below).

The first and second author collaboratively developed a codebook, with codes and code definitions evolving over the course of the analysis as the two authors discussed the applicability of codes to tweets and the definition and scope of each code. Our analysis combined deductive and inductive modes (Timmermans, & Tavory, Citation2012) – starting with a core set of codes based on the project’s focus on emotions and its textual and visual representation (Bleiker et al., Citation2013; Loseke, Citation2009), while also developing new codes to fit with the emergent features of the data. Codes specific to different emotions (fear, worry, hope, compassion, doubt/distrust, anger, humor) were included, along with codes about important actors (government figures, organizations, healthcare professionals) and references to science and risk. The codebook’s evolution captured how discrete emotions were communicated. Through this inductive approach a range of emotional expressions can be more fully captured (Ihekweazu, Citation2017), though classifying discrete emotions is rarely a straightforward process (Rogers, & Robinson, Citation2014).

Humor, perhaps even more so than other emotion practices, is challenging to identify. Humor as a theme emerged and evolved through dialogue among the two authors, as well as engagement with the literature on Black Twitter. This direct engagement with the literature aligns with abductive analysis (Sastry, & Basu, Citation2020; Timmermans, & Tavory, Citation2012). Humor was applied whenever a tweet conveyed jokes, puns, sarcasm, or especially hyperbolic statements (such as moving “to the moon”). Once the original sample had been analyzed fully, we took a random subsample of tweets (1000 from week one and 1200 from week two) and assigned thematic codes independently. We calculated the degree of observed agreement between the two raters and Cohen’s kappa – a statistic that weights the observed agreement based on chance (Viera, & Garrett, Citation2005). We found that humor applied to 38% of the Tweets in week two (an average between the two raters) and the Cohen’s kappa score was .75, suggesting substantial agreement between the two independent coders. While part of a larger study of emotions in Twitter responses to Ebola, in this article we focus specifically on how humor was used within mainstream and Black Twitter and its overlap with conceptions of risk, fear, solidarity, and hope.

Social media data blur the lines between public and private (Hays, & Daker-White, Citation2015; McKee, Citation2013). In the findings, we anonymize the tweets of individual social media users but show the source when a tweet originated from a generic humor account. Tweets whose authors could be re-identified have been edited in order to assure anonymity (Markham, Citation2012). The ethics review board at the University of Amsterdam approved the project.

Results

The predominance of humor in our dataset fits with the general culture of Twitter as a site for playfulness and irreverence (Davis et al., Citation2018). Yet in using humor in connection with the Ebola outbreak, humor-based tweets go against a dominant feeling rule that death and suffering, and certainly an emerging public health crisis, are somber and serious matters not to be joked about in public arenas. We begin by discussing popular tweets in our dataset that appear as part of the mainstream (in that they do not use criteria that would render them as part of Black Twitter). Then we examine how mainstream humor practices differed from those among Black Twitter and what these humor practices do in terms of negotiating fear and risk during the outbreak.

Mainstream humor

One of the most popular examples of mainstream humor in our sample, with 264 instances in our week 2 dataset, was the SpongeBob tweet shown in .

This tweet, published by a meme account, references the popular children’s cartoon, SpongeBob SquarePants. The image shows a small plot of green grass and a tree surrounded by a glass enclosure. Accompanying the image is the text “If Ebola ever hits my city … ” Themes of isolation and self-quarantine were prevalent in mainstream humor and highlight a conception of Ebola as an abstract and diffuse risk that can only be avoided by cutting off all ties to the outside world. At times, the theme of isolation was rooted in real-world scenarios (“I can’t go to school tomorrow, I’m not taking any chances with Ebola”).

Mainstream humor practices employed a sarcastic tone, a nonchalance about death, or (joking) acceptance of the inevitability of death (“I’m going to die,” “goodbye world,” “Ebola victims rising from the dead … ok. Cool”). Other mainstream humor responses reflected anger, suggesting violent solutions to the Ebola crisis (“nuke Texas”), combined humor with discussion of political themes (visas, Obamacare, Republicans, ISIS) or apocalyptic scenarios, suggesting the end of the world was near. This included tweets centered on the theme of being armed and being prepared for doomsday. Popular mainstream jokes also leveraged references to popular figures, like the example of SpongeBob above, as well as other celebrities like Katy Perry: “Ebola is God’s punishment to us for Katy Perry’s singing.” One popular tweet connected the emergence of Ebola in the U.S. with the gatekeeping practices found at fraternity parties on college campuses: “*Ebola tries to enter US* Frat guy: who do you know here.”

In contrast with mainstream Twitter humor, Black Twitter instead used humor to explore the social tensions and uncertainty that the epidemic created, including creative work-arounds that would allow social connections to continue despite the risks. Reactions to the epidemic within Black Twitter focused more on hypothetical situations where life continued even after and despite an Ebola outbreak on U.S. soil. Our findings trace the combination of humor and risk in these popular tweets and how they intersect with Black identity, cultural practices, and pop cultural references within this influential digital affect culture. Humor practices on Black Twitter explored the spectrum between trust and distrust, staying safe while engaging in daily activities, and an unwillingness to isolate completely from others. Rather than resorting to isolationist or post-apocalyptic humor, Black Twitter manages uncertainty and social tensions by exploring how individuals can continue normal social behaviors through creative and at times absurd solutions that manage risk. Below we explore these themes in more detail by looking at how Black Twitter humor practices focused on (1) maintaining social connections in public and small groups and (2) maintaining social connections in romantic and sexual relationships.

Black Twitter humor

Maintaining social connections: in public and in small groups

The following examples illustrate Black Twitter’s use of humor to discuss hypothetical Ebola scenarios. The humor in these tweets centers on finding creative solutions to maintaining social connections within the community while managing the increased risk posed by the outbreak. Through proper precaution, references to leisure activities suggest that life might continue despite Ebola. In continuing these activities, values that prioritize close relationships, community connections, and a sense of style are maintained.

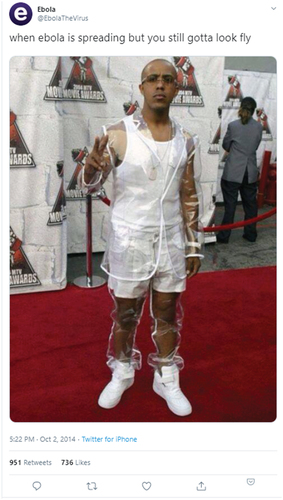

In , the first example of Black Twitter humor, we see an image of Marques Houston wearing a plastic suit to the 2004 MTV awards. At the time, Houston’s fashion choice was roundly mocked, with his outfit featured on lists of worst outfits of the night.Footnote5 This tweet brings back this Black cultural moment to further make fun of the outfit in a “roast”—a classic signifyin’ practice. The joke, staying “fly” during an Ebola outbreak, finds a more logical explanation for this outfit as personal protective equipment (PPE) rather than simply fashion.

The desire to look “fly” in the African American community is “shaped by the particularities of the unique cultural experiences of being of African descent and survival as a disenfranchised people in a Eurocentric culture for centuries” (O’Neal, Citation1994). Respectability politics encouraged Black people to gain “esteem from white America,” as a way to push back against negative stereotypes and “better position themselves to struggle for equity and inclusion within dominant society” (Higginbotham, Citation1993, p. 14). Black communities’ pride in looking good emerged from having to dress especially well in order to, for example, get jobs or be accepted into schools (Miller, & Martin, Citation2012). This has evolved into routine trendsetting that often influences mainstream fashion, and can be seen in the culture at Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs), for example, where people joke that students go to class looking ready to walk a runway (Jones, Citation2017). Like the example of roasting Lil’ Mama’s weave discussed earlier, this tweet attests to the fact that not all creative fashion is a hit, but style and innovation are especially valued within the community.

In repurposing Houston’s outfit, this tweet defies dominant feeling norms by suggesting that not even Ebola will get in the way of looking and feeling good. Even in the context of a potentially deadly virus, creativity and home-made PPE allow cultural norms to continue. Instead of being fearful or worried about Ebola, there is humorous optimism in finding silly work arounds. In this sense, the tweet downplays fears and positions Ebola as something manageable.

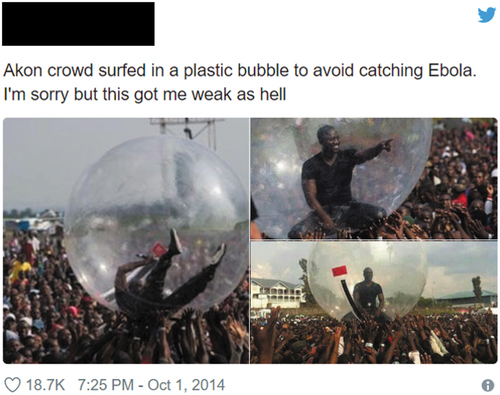

Another example of maintaining public connections despite the threat of Ebola was a popular tweet showing the musician Akon in a plastic bubble during a concert. Next to the image is the text, “Akon crowd surfed in a plastic bubble to avoid catching Ebola. I’m sorry but this got me weak as hell.” There were 232 instances of this tweet in our week 2 dataset ().

The phrase “weak as hell” indicates that the image is so funny as to render one unable to stand upright. Retweets of this same image included tears of laughter emojis. The tweet was retweeted and liked tens of thousands of times, there were copycat tweets, and rumors spread that Akon did indeed crowd surf in a bubble to avoid catching Ebola. Follow up articles debunked this myth (Pocklington, Citation2014), but the concert photos came to be associated with Ebola. By linking the topic of Ebola with photos of a smiling Akon, positive emotions are juxtaposed with conflicting expectations, creating an absurd and humorous contrast. In joking about another makeshift solution to avoiding Ebola (the plastic bubble), the tweet finds humor in the idea that despite increased risk, public and even festive activities can continue. The tweet challenges our understanding of trust in others during a public health crisis and provides an alternate response to a possible Ebola threat where community might be chosen over isolation or violence. Tensions between trust and distrust are further explored in the next two examples ().

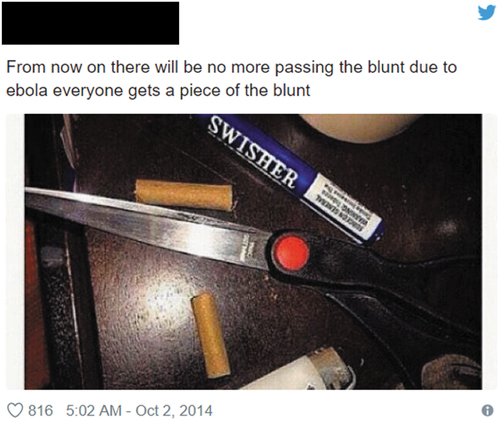

In the “piece of the blunt” tweet, a photo of a blunt (a marijuana cigar) cut into pieces is combined with the text, “from now on there will be no more passing the blunt due to Ebola everyone gets a piece of the blunt.” The element of fear in this joke is rooted in self-preservation and distrust of others’ health status. But avoiding all communal activities seems unthinkable, so cutting up the bunt in smaller pieces is proposed as a workaround. Fear, in the end, does not stand in the way of gathering for a smoke session. Smoking with friends is certainly not exclusive to Black culture. But the phrase “puff, puff, pass,” a reference to communal smoking, was made popular through Black comedy.Footnote6 This example uses Black cultural practices to “communicate shared knowledge and experiences” along with “elements of humor and displays of wit” (Florini, Citation2014, p. 224). The sharing of marijuana, picture of the Swisher label, and image of the scissors combine to serve as a makeshift solution to protecting each participant from Ebola. The “piece of the blunt” tweet conceptualizes Ebola as something manageable and communal behaviors remain valued highly despite the fear of contagion.

, another example that emphasizes social connection during a viral outbreak, re-uses a screenshot of health workers putting on PPE from a news segment, accompanied by the text, “when u and the squad bout 2 hit da skrip club but find out 1 of da skrippas got the ebola.” This tweet is an example of signifyin’ in its timeliness around mainstream Ebola concerns. The joke format is distinct in its creative use of Ebola imagery to refer to measures taken to protect oneself against Ebola. “Squad” conveys close significant others, togetherness, and solidarity, suggesting activities with friends are worth continuing despite Ebola risks. Instead of imagining a post-apocalyptic world where Ebola has created chaos, this tweet imagines a world where people coexist with the virus and continue communal practices, however silly. This interpretation “provides a healthy and socially beneficial way to react to hypothetical threats,” (McGraw, & Warren, Citation2010, p. 1148) and provides “an ability to smile ironically at our conflicted human condition” (Elgee, Citation2003, p. 480). In rejecting dominant feeling rules that prescribe fear, this tweet, like the others, conveys optimism by suggesting that communal life can continue.

Maintaining social connections: in romantic and sexual relationships

In addition to identifying comical ways to maintain social connection in the public sphere and small-group gatherings, Black Twitter similarly challenged assumptions of Ebola fear and how it would shape romantic and sexual relationships. The humor in this context centered on maintaining intimacy and romantic connection despite Ebola risks. The following example was one of the most popular tweets in our dataset, with 448 instances found in week 2, crossing into the mainstream with its broad popularity. The tweet uses an image from behind the scenes of the popular television show, The Walking Dead, and includes the caption: “when bae gets Ebola but you still love her #truelove” ()

.Zombies were a common trope in mainstream Twitter reactions to the epidemic. Discussions of Ebola victims “rising from the dead” were catalyzed in part by a news story in major outlets (Dovey, Citation2014) that alleged a victim had “come back from the dead.” Zombies are a staple of the horror genre (Wonser, & Boyns, Citation2016) and are typically associated with fear because they are grotesque, attack humans, and ooze bodily fluids – the latter being a key mechanism for the transmission of Ebola. The tweet uses a graphic and absurd image to suggest that Ebola turns one into a decaying corpse and renders Ebola fear explicit through imagery of a zombie-like death. Yet through the use of “zombie bae” (“bae” being a term of endearment) and the large, toothy smile of Sheriff Rick, we see a juxtaposition that lessens the perceived threat. The tweet simultaneously provides a stark contrast to the images shared during Ebola coverage of suffering; instead, it is optimistic, and although irreverent and silly, refuses to see Ebola as a threat to human connection.

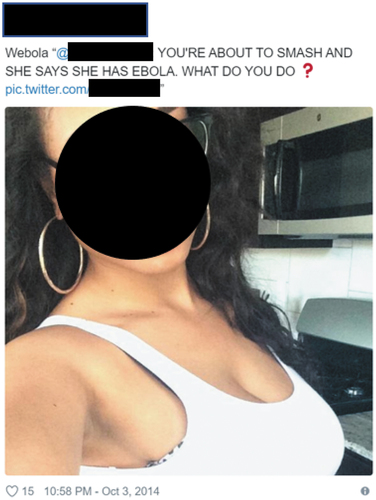

Although some tweets criticized this type of humor as insensitive to Ebola patients, the tweet creates distance from death, creatively engaging the tension between the fragile human condition and our ability to laugh at it (Elgee, Citation2003), even if this ability to laugh is afforded by the distance of not being personally affected by the outbreak (as was the case for the vast majority of Americans). The tweet embraces life with Ebola in it and, similar to the “Webola” joke (), romantic and sexual partnerships are valued highly, even if it means putting yourself at risk

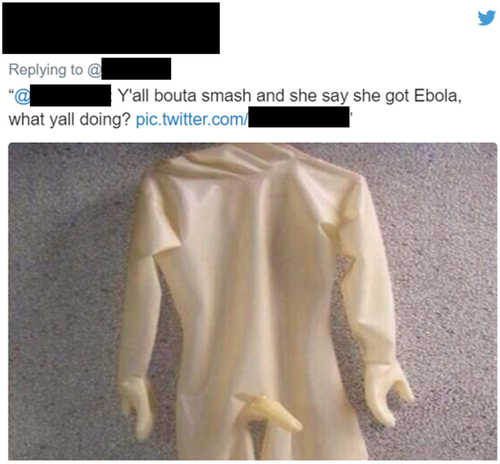

.The “Bouta Smash” and “Webola” tweets in illustrate two responses to the same hypothetical question: “Y’all boutta smash [have sex] and she say she got Ebola, what yall doing?” In the first screenshot, a Twitter user replies with a photo of a full body condom as their answer to the question. The second tweet jokingly offers webola to suggest that the author would risk Ebola if it meant that they and the woman in the photo could form a “we.” “Webola” clearly aligns with a signifyin’ practice that “prioritizes verbal dexterity, wit, and wordplay” (Florini, Citation2014, p. 229). In both reactions, users downplay the likelihood of contracting the disease and the severity of it, resisting calls for fear and vigilance found in the health communication of the WHO and CDC (Sastry, & Lovari, Citation2017).

While humor practices in response to Ebola or other public health threats deviate from a dominant emotion norm that prescribes somber concern and vigilance as the most appropriate emotional reactions, the humor practices developed on Black Twitter engage in a hopeful imagining of future risks that can be managed in order to maintain romantic and sexual connections. This speaks to Black Twitter’s role as creatively navigating risk and dominant feeling rules – highlighting emotions as practices (Scheer, Citation2012) enacted within this influential digital affect culture (Döveling et al., Citation2018). Ebola fears in Black Twitter humor are not ignored but rendered manageable through creative interventions that prioritize social connections above individual survival. Despite the negative potential impacts on health should an Ebola outbreak reach the U.S., reactions on Black Twitter offer humorous suggestions for how to continue engaging in public events, fashion, friendship, and romantic and sexual partnership – the very social interactions that become suspect during a contagious outbreak. While inherently silly, these reactions convey a sense of optimism that life will not come to a standstill because of a contagious disease. We explore the implications of these findings for understanding outbreaks and public health messaging below.

Discussion

Humor can be a strategy for coping with death (Cain, Citation2012) and existential angst (Elgee, Citation2003). But to suggest that humor’s only function is one of coping overlooks the more complex feelings of solidarity, hope, and comradery that can be cultivated through digital humor practices. Humor practices that rely on the integration of cultural symbols (fashion, cultural objects, celebrity icons) with commentary work together to create a shared digital affect culture (Döveling et al., Citation2018). Similar to other research on disaster humor (Kuipers, Citation2005), humor practices in the context of Ebola defy dominant emotion norms about the appropriate emotional responses to an epidemic. Discussion of the media stoking fear was prominent during the Ebola outbreak (Chan, Citation2015; Cottingham, Citation2022; Gupta, Citation2014). Yet, humor emerged as a powerful resource for aligning oneself with a particular group and fostering solidarity at a time of threat. This can include a shared, knowing chuckle about the absurdity of dominant cultural norms, including the absurdity of distrusting one’s closest circle during a crisis. Many of the AAVE terms in our dataset were distinct terms used for close companions: “bae,” “homeboy,” “squad,” and the conversational “y’all”. Such terminology points to in-group, informal styles that digitally interpellate (Althusser, Citation1971) others and themselves as a part of a shared subculture (Brock, Citation2011).

Humor can be an energizing, solidarity-building practice that also points to underlying values in a particular digital culture. Mainstream humor in our sample centered on isolation, self-quarantine, political critique, and, at times, sarcastically accepted death as inevitable. By contrast, Black Twitter humor practices explored how social connections will endure despite the threat of a contagious epidemic and how precautions allow public engagement and interactions with friends and romantic partners to continue. Black Twitter’s emphasis on community and social connections, rather than looking to the government for protection may be linked to historical and ongoing governmental failures to protect Black communities, including through disparities in health and healthcare (Kennedy et al., Citation2007), in the response to hurricane Katrina (Cordasco et al., Citation2007), in cases of over-policing and police brutality (Evans, & Feagin, Citation2015), and in the disparities in rates of infection and death from COVID-19 (Tai et al., Citation2021).

Black Twitter’s differing emphasis on social connections during an outbreak, perhaps gained through generations of similarly life-threatening events (slavery, Jim Crow, mass incarceration, and policy brutality), shows that there are varied responses to a public health threat beyond fear. Conceptions of risk are never weighed in isolation from other life circumstances (Cottingham, & Fisher, Citation2016). The ability to use humor, creativity, and absurd juxtapositions comes from a shared understanding of being racialized in America. Individual tweets can signal one’s membership within Black Twitter and communicate a shared outsider-within status (Collins, Citation1986), positioning one as critical of dominant discourses. The in-group connections with other users creates solidarity (Florini, Citation2014) around differing perceptions of risk and emotions experienced through Black identity and situated knowledge. In perceiving risk as manageable, these tweets often have an element of optimism that was absent from mainstream humor practices on Twitter.

Implications and limitations

Black Twitter maintains its coherence through specific language use, references to Black cultural practices, and normalized contexts related to Black life. As Graham and Smith (Citation2016) note, “African Americans are some of the most influential users of Twitter … [they] have managed to participate in and mold national discourses around numerous topics like #IcantBreathe and #BlackLivesMatter” (p. 433). Responding to public health threats like an epidemic requires a multi-faceted approach that involves policies aimed at curtailing the spread, as well as informing diverse publics in ways that recognize the differing risks and baseline values of different groups. Risk communication strategies tend to downplay emotions or assume that the public experiences overwhelming panic and fear during a crisis (Kilgo et al., Citation2019; Ungar, Citation1998), while direct research on the public’s emotions during a crisis is more mixed (Johnson, Citation1988, Citation2017). Feelings of fear, as well as anger, compassion, and humor, might be inevitable in the complex discussions that surround a public health threat. Rather than ignore these various emotions, health communication and media scholars should consider fully how threats might be channeled and transformed within digital affect cultures. Humor practices might seem frivolous but can be powerful resources for maintaining solidarity and connection.

One key finding from our analysis of Black Twitter humor is the priority it places on community and personal relationships, despite the threat that such connections imply in the context of a contagious outbreak. Calls from the CDC to isolate and avoid contact with othersFootnote7—calls that often emphasize individual protection and survival – might be dismissed by groups where community connections are valued above and beyond individualism. Similarly, in the case of COVID-19, an emphasis on knowledge and isolation by the WHOFootnote8 invariably ignores the social and emotional contexts in which people live. In such messaging, other people are often framed as a threat (“Outbreaks have been reported in places where people have gather[ed]”) or reduced to instrumental functions (“Have someone bring you supplies”). Such messages will have limited appeal if they assume that connections with others (and feelings of solidarity) are meaningless during an outbreak.

While we have focused here on the different humor practices used on Twitter, it is important to note that Black Twitter is not a homogenous group. Indeed, as we note at the outset, many of the most popular humor-based tweets in our dataset met the criteria for being classified as part of Black Twitter. Their popularity shows that the boundaries between the mainstream and highly influential subcultures are not always clear. As Hill notes, “Black Twitter is a contested terrain, a site of struggle over competing meanings, politics, values, and identities” (Hill, Citation2018, p. 12). This study adds to the growing body of scholarship on mediated emotions and influential affect cultures on social media. In light of the COVID-19 pandemic, understanding digital practices and responses to health threats is more critical than ever. Future research might explicitly examine, through focus groups or interviews, the ways in which various groups respond to the use of humor in public health messaging. As with Ebola, COVID-19 has ushered in a trove of humor practices, illustrated in memes and videos circulated through social media. Public health messaging has yet to fully capitalize on the energizing potential of social media communication during a health threat to tailor messages and rethink assumptions about the emotion practices that infuse an evolving outbreak.

Acknowledgements

We want to thank the three anonymous reviewers and the editor for their helpful feedback on prior drafts. This research received funding support from the Fund for the Advancement of the Discipline (American Sociological Association and the U.S. National Science Foundation) and the Amsterdam Young Academy. Additionally, dedicated time for research and writing was made possible by a fellowship at the Hanse-Wissenschaftskolleg Institute for Advanced Study in Delmenhorst, Germany and through Aspasia funding from Dr. Sarah Bracke’s Vici grant, funded by the Dutch Research Council (NWO, project number 016.Vici.185.077).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

4. We limit our discussion of the events of the 2014 (actually 2013–2016) Ebola outbreak. Many scholars have provided both comprehensive and critical reflections on this epidemic’s development (see Ihekweazu, Citation2017; Sastry, & Lovari, Citation2017).

5. For example, see: https://www.vibe.com/features/vixen/hip-hops-best-and-worst-fashion-moments-305668/.

6. See, for example, the 2006 film with the phrase used as the title: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0466771/.

References

- Althusser, L. (1971). Lenin and philosophy, and other essays. New Left Books.

- Bleiker, R., Campbell, D., Hutchison, E., & Nicholson, X. (2013). The visual dehumanisation of refugees. Australian Journal of Political Science, 48(4), 398–416. https://doi.org/10.1080/10361146.2013.840769

- Brock, A. (2009). “Who do you think you are?”: Race, representation, and cultural rhetorics in online spaces. Poroi, 6(1), 15–35. https://doi.org/10.13008/2151-2957.1013

- Brock, A. (2011). Beyond the pale: The Blackbird web browser’s critical reception. New Media & Society, 13(7), 1085–1103. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444810397031

- Brown, M., Ray, R., Summers, E., & Fraistat, N. (2017). #sayhername: A case study of intersectional social media activism. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 40(11), 1831–1846. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2017.1334934

- Brownlie, J., & Shaw, F. (2019). Empathy rituals: Small conversations about emotional distress on Twitter. Sociology, 53(1), 104–122. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038518767075

- Cain, C. L. (2012). Integrating dark humor and compassion: Identities and presentations of self in the front and back regions of hospice. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 41(6), 668–694. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891241612458122

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2015). 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n2HneM9Ewoo&list=PLIndH34c4h_rKhnAg0xLPitYQRF6txRIa&index=6&t=1386s

- Chan, M. (2015, November 2). WHO Director-General addresses Princeton—Fung Global Forum on lessons learned from the Ebola crisis. Princeton – Fung Global Forum. http://who.int/dg/speeches/2015/princeton-ebola-lessons/en/

- Chew, C., & Eysenbach, G. (2010). Pandemics in the age of Twitter: Content analysis of tweets during the 2009 H1N1 outbreak. PLoS ONE, 5(11), e14118. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0014118

- Collins, P. H. (1986). Learning from the outsider within: The sociological significance of Black feminist thought. Social Problems, 33(6), S14–S32. https://doi.org/10.2307/800672

- Collins, P. H. (2000). Black feminist thought: Knowledge, consciousness, and the politics of empowerment. Routledge.

- Cordasco, K. M., Eisenman, D. P., Glik, D. C., Golden, J. F., & Asch, S. M. (2007). “They blew the levee”: Distrust of authorities among hurricane Katrina evacuees. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 18(2), 277–282. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2007.0028

- Cottingham, M. D. (2016). Theorizing emotional capital. Theory and Society, 45(5), 451–470. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11186-016-9278-7

- Cottingham, M. D. (2022). Practical feelings: Emotions as resources in a dynamic social world. Oxford University Press.

- Cottingham, M. D., & Fisher, J. A. (2016). Risk and emotion among healthy volunteers in clinical trials. Social Psychology Quarterly, 79(3), 222–242. https://doi.org/10.1177/0190272516657655

- Davis, J. L., Love, T. P., & Killen, G. (2018). Seriously funny: The political work of humor on social media. New Media & Society, 20(10), 3898–3916. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444818762602

- Döveling, K., Harju, A. A., & Sommer, D. (2018). From mediatized emotion to digital affect cultures: New technologies and global flows of emotion. Social Media + Society, 4 (1. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305117743141

- Dovey, D. (2014, October 3). Video: Ebola victim thought dead comes back to life minutes before cremation. Newsweek. https://www.newsweek.com/ebola-zombie-comes-back-life-minues-cremation-275149

- Dynel, M. (2020). On being roasted, toasted and burned: (Meta)pragmatics of Wendy’s Twitter humour. Journal of Pragmatics, 166, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2020.05.008

- Elgee, N. J. (2003). Laughing at death. Psychoanalytic Review, 90(4), 475–497. https://doi.org/10.1521/prev.90.4.475.23917

- Evans, L., & Feagin, J. R. (2015). The costs of policing violence: Foregrounding cognitive and emotional labor. Critical Sociology, 41(6), 887–895. https://doi.org/10.1177/0896920515589727

- Fine, G. A., & DeSoucey, M. (2005). Joking cultures: Humor themes as social regulation in group life. Humor - International Journal of Humor Research, 18(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1515/humr.2005.18.1.1

- Florini, S. (2014). Tweets, tweeps, and signifyin’: Communication and cultural performance on “Black Twitter. Television & New Media, 15(3), 223–237. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527476413480247

- Francis, L. E. (1994). Laughter, the best mediation: Humor as emotion management in interaction. Symbolic Interaction, 17(2), 147–163. https://doi.org/10.1525/si.1994.17.2.147

- Golder, S. A., & Macy, M. W. (2011). Diurnal and seasonal mood vary with work, sleep, and daylength across diverse cultures. Science, 333(6051), 1878–1881. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1202775

- Graham, R., & Smith, S. (2016). The content of our #characters: Black Twitter as counterpublic. Sociology of Race and Ethnicity, 2(4), 433–449. https://doi.org/10.1177/2332649216639067

- Gupta, S. (2014, October 18). Are Ebola fears the media’s fault? CNN. https://edition.cnn.com/videos/bestoftv/2014/10/18/rs-are-ebola-fears-the-medias-fault.cnn

- Hays, R., & Daker-White, G. (2015). The care.Data consensus? A qualitative analysis of opinions expressed on Twitter. BMC Public Health, 15(1), 838. PMC. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-2180-9

- Henefeld, M. (2016). Laughter in the age of Trump. Flow. http://www.flowjournal.org/2016/12/laughter-in-the-age-of-trump/

- Higginbotham, E. B. (1993). Righteous discontent: The women’s movement in the Black Baptist church, 1880-1920. Harvard University Press.

- Hill, M. L. (2018). “Thank you, Black Twitter”: State violence, digital counterpublics, and pedagogies of resistance. Urban Education, 53(2), 286–302. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042085917747124

- Hochschild, A. R. (1979). Emotion work, feeling rules, and social structure. The American Journal of Sociology, 85(3), 551–575. https://doi.org/10.1086/227049

- Ihekweazu, C. (2017). Ebola in prime time: A content analysis of sensationalism and efficacy information in U.S. nightly news coverage of the Ebola outbreaks. Health Communication, 32(6), 741–748. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2016.1172287

- Ince, J., Rojas, F., & Davis, C. A. (2017). The social media response to Black Lives Matter: How Twitter users interact with Black Lives Matter through hashtag use. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 40(11), 1814–1830. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2017.1334931

- Johnson, N. R. (1988). Fire in a crowded theater: A descriptive investigation of the emergence of panic. International Journal of Mass Emergencies and Disasters, 6(1), 7–26. http://ijmed.org/articles/134/

- Johnson, B. B. (2017). Explaining Americans’ responses to dread epidemics: An illustration with Ebola in late 2014. Journal of Risk Research, 20(10), 1338–1357. https://doi.org/10.1080/13669877.2016.1153507

- Jones, J. J. (2017). Why students at Historically Black Colleges and Universities have amazing style. Racked. https://www.racked.com/2017/5/8/15427174/hbcu-style

- Julien, C. (2015). Bourdieu, social capital and online interaction. Sociology, 49(2), 356–373. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038514535862

- Kennedy, B. R., Mathis, C. C., & Woods, A. K. (2007). African Americans and their distrust of the health care system: Healthcare for diverse populations. Journal of Cultural Diversity, 14(2), 56–61. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19175244/

- Kies, B. (2021). Remediating the celebrity roast: The place of mean tweets on late-night television. Television & New Media, 22(5), 516–528. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527476419892581

- Kilgo, D. K., Yoo, J., & Johnson, T. J. (2019). Spreading Ebola panic: Newspaper and social media coverage of the 2014 Ebola health crisis. Health Communication, 34(8), 811–817. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2018.1437524

- Kuipers, G. (2005). “Where was King Kong when we needed him?” Public discourse, digital disaster jokes, and the functions of laughter after 9/11. Journal of American Culture, 28(1), 70–84. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1542-734X.2005.00155.x

- Kuipers, G. (2008). The sociology of humor. In V. Raskin (Ed.), The primer of humor research (pp. 361–398). Walter de Gruyter.

- Lazard, A. J., Scheinfeld, E., Bernhardt, J. M., Wilcox, G. B., & Suran, M. (2015). Detecting themes of public concern: A text mining analysis of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Ebola live Twitter chat. American Journal of Infection Control, 43(10), 1109–1111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2015.05.025

- Liberman, N., & Trope, Y. (2008). The psychology of transcending the here and now. Science, 322(5905), 1201–1205. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1161958

- Loseke, D. R. (2009). Examining emotion as discourse: Emotion codes and presidential speeches justifying war. The Sociological Quarterly, 50(3), 497–524. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1533-8525.2009.01150.x

- Lu, J. H., & Steele, C. K. (2019). ‘Joy is resistance’: Cross-platform resilience and (re)invention of Black oral culture online. Information, Communication & Society, 22(6), 823–837. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2019.1575449

- Maragh, R. S. (2018). Authenticity on “Black Twitter”: Reading racial performance and social networking. Television & New Media, 19(7), 591–609. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527476417738569

- Markham, A. (2012). Fabrication as ethical practice: Qualitative inquiry in ambiguous internet contexts. Information, Communication & Society, 15(3), 334–353. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2011.641993

- McDonald, S. N. (2014). Black Twitter: A virtual community ready to hashtag out a response to cultural issues. Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/style/black-twitter-a-virtual-community-ready-to-hashtag-out-a-response-to-cultural-issues/2014/01/20/41ddacf6-7ec5-11e3-9556-4a4bf7bcbd84_story.html

- McGraw, P. A., & Warren, C. (2010). Benign violations: Making immoral behavior funny. Psychological Science, 21(8), 1141–1149. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797610376073

- McKee, R. (2013). Ethical issues in using social media for health and health care research. Health Policy, 110(2), 298–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2013.02.006

- Miller, M. L., & Martin, M. (2012). Why black men tend to be fashion kings. https://www.npr.org/2012/12/31/167720258/why-black-men-tend-to-be-fashion-kings?t=1642601909914

- Monk-Payton, B. (2017). #laughingwhileblack. Feminist Media Histories, 3(2), 15–35. https://doi.org/10.1525/fmh.2017.3.2.15

- O’Neal, G. S. (1994). African-American aesthetic of dress: Symmetry through diversity. In M. R. DeLong & A. M. Fiore (Eds.), Aesthetics of Textiles and Clothing: Advancing Multidisciplinary Perspectives (pp. 212–223). ITAA Special publication. Monument, CO.

- Odlum, M., & Yoon, S. (2015). What can we learn about the Ebola outbreak from tweets? American Journal of Infection Control, 43(6), 563–571. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2015.02.023

- Oh, S.-H., Lee, S. Y., & Han, C. (2021). The effects of social media use on preventive behaviors during infectious disease outbreaks: The mediating role of self-relevant emotions and public risk perception. Health Communication, 36(8), 972–981. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2020.1724639

- Pocklington, R. (2014). Did Akon crowd surf in inflatable bubble to avoid catching Ebola at African concert? Mirror. https://www.mirror.co.uk/3am/celebrity-news/akon-crowd-surf-inflatable-bubble-4372337

- Recuber, T. (2016). Consuming catastrophe: Mass culture in America’s decade of disaster. Temple University Press.

- Rodd, I. (2020, March 18). Coronavirus: Violinists play Titanic hymn in front of empty toilet paper aisle. BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/av/world-us-canada-51942217

- Rogers, K. B., & Robinson, D. (2014). Measuring affect and emotions. In J. E. Stets & J. H. Turner (Eds.), Handbook of the sociology of emotions (Vol. II, pp. 283–303). Springer.

- Sastry, S., & Basu, A. (2020). How to have (critical) method in a pandemic: Outlining a culture-centered approach to health discourse analysis. Frontiers in Communication, 5. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2020.585954

- Sastry, S., & Dutta, M. J. (2017). Health communication in the time of Ebola: A culture-centered interrogation. Journal of Health Communication, 22(sup1), 10–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2016.1216205

- Sastry, S., & Lovari, A. (2017). Communicating the ontological narrative of Ebola: An emerging disease in the time of “epidemic 2.0. Health Communication, 32(3), 329–338. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2016.1138380

- Scheer, M. (2012). Are emotions a kind of practice (and is that what makes them have a history)? A Bourdieuian approach to understanding emotion. History and Theory, 51(2), 193–220. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2303.2012.00621.x/full

- Stage, C., & Hougaard, T. T. (2018). The language of illness and death on social media: An affective approach. Emerald Publishing.

- Tai, D. B. G., Shah, A., Doubeni, C. A., Sia, I. G., & Wieland, M. L. (2021). The disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on racial and ethnic minorities in the United States. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 72(4), 703–706. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa815

- Timmermans, S., & Tavory, I. (2012). Theory construction in qualitative research: From grounded theory to abductive analysis. Sociological Theory, 30(3), 167–186. https://doi.org/10.1177/0735275112457914

- Ungar, S. (1998). Hot crises and media reassurance: A comparison of emerging diseases and Ebola Zaire. The British Journal of Sociology, 49(1), 36–56. JSTOR. https://doi.org/10.2307/591262

- Viera, A. J., & Garrett, J. M. (2005). Understanding interobserver agreement: The kappa statistic. Family Medicine, 37(5), 360–363. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15883903/

- Wamsley, L. (2020, March 4). Coronavirus fears have led to a golden age of hand-washing PSAs. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2020/03/04/811609241/coronavirus-fears-have-led-to-a-golden-age-of-hand-washing-psas

- Wonser, R., & Boyns, D. (2016). Between the living and undead: How zombie cinema reflects the social construction of risk, the anxious self, and disease pandemic. The Sociological Quarterly, 57(4), 628–653. https://doi.org/10.1111/tsq.12150