ABSTRACT

Examining team care for the care team, this scoping literature review highlights the relational and compassionate dimensions of collaboration and teamwork that can alleviate healthcare worker suffering and promote well-being in challenging contexts of care. Its goal is to provide greater conceptual clarity about team care and examine the contextual dimensions regarding the needs and facilitators of team care. Analysis of the 48 retained texts identified three broad types of communicative practice that constitute team care: sharing; supporting; and leading with compassion. The environmental conditions facilitating team care included a caring team culture and specific and accessible organizational supports. These results are crystallized into a conceptual model of team care that situates team care within a system of team and organizational needs and anticipated outcomes. Gaps in the literature are noted and avenues for future research are suggested.

Healthcare systems in developed countries around the world are in crisis (Canadian Medical Association, Citation2022; Madara, Citation2020; Pinna, Citation2022), a situation laid bare and exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Contributing factors are multiple, including aging populations that require more complex care, a growing healthcare worker shortage, and swelling costs (Wanzer et al., Citation2009; Wittenberg-Lyles et al., Citation2014). At the same time, healthcare systems are increasingly relying on collaborative and team-based approaches to care delivery (Baik, Citation2017). Thus, as they collaborate with one another, healthcare workers must do more with less (Wilkinson, Citation2015), leading to increased rates of burnout, moral distress, compassion fatigue (or secondary traumatic stress), turnover, and disengagement (Adriaenssens et al., Citation2017; Aiken et al., Citation2014; Maiden et al., Citation2011; Pavlish et al., Citation2016; Pfaff et al., Citation2017; Strolin-Goltzman et al., Citation2020). These negative outcomes are what the fourth element of the Quadruple Aim in health care (Bodenheimer & Sinsky, Citation2014) seeks to address, namely improving the work life and well-being of the care team as a prerequisite to providing efficient, quality, and patient-centered care (Davis & Batcheller, Citation2020). The Quadruple Aim amended Berwick et al.”s (Citation2008) Triple Aim, a document that established three overarching goals to guide U.S. healthcare efforts and reforms: improving the care of individual patients; promoting the health of populations; and lowering healthcare costs. The Quadruple Aim was significant for insisting that these goals can only be achieved in a context where the well-being of healthcare providers is taken into account.

However, Bodenheimer and Sinsky’s (Citation2014) proposed solutions for the Quadruple Aim focus on the rational management of team resources, such as professional roles, schedules, task coordination, and information sharing. Much of the literature on teamwork and collaboration in health care adopts this task-oriented focus on effectiveness and efficiency (e.g., Canadian Medical Protective Association, Citation2007; see also Eisenberg, Citation2008). This focus overlooks the relational and compassionate dimensions of healthcare teamwork by and for team members – what we propose to call “team care”—that could significantly contribute to care team well-being (Fernando & Hughes, Citation2019; Hewison et al., Citation2019; Lown et al., Citation2016; McDonald et al., Citation2010). Previous research has shown that socially supportive communication is positively associated with healthcare worker resilience (Barsade & O’Neill, Citation2014; Nolan, Citation2013; Pfaff et al., Citation2017; Sinclair et al., Citation2017). However, neither socially supportive communication nor resilience tend to be conceptualized or measured at the collective level of teams (Aburn et al., Citation2020). Hence, the notion of team care and its constitutive practices remain somewhat fuzzy and underspecified in the literature on teamwork and collaboration in healthcare contexts. This is problematic because the conceptual contours of team care as well as its facilitating contextual conditions must be better understood to support healthcare worker well-being, particularly as healthcare systems respond to the current state of crisis. Efforts to alleviate healthcare worker suffering cannot focus solely on the rationalization of resources or improved organization of individual and collective tasks, nor can they be undertaken in isolation from teamwork or collaboration.

Therefore, the purpose of this scoping review is to provide a conceptual overview of what constitutes team care in healthcare organizations. We propose the term “team care” to distinguish it from “collaborative care,” which refers to healthcare professionals working together and with patients and families to provide integrated care (e.g., Canadian Medical Protective Association, Citation2007; Unützer et al., Citation2013). By team care, we mean the compassionate and relational dimensions of collaboration in healthcare contexts that contribute to healthcare worker well-being and ability to provide compassionate care to patients. The four specific goals were to (a) conduct a thorough search of the published healthcare literature about team care, paying particular attention to communication practices that constitute team care, (b) provide greater conceptual clarity and specificity regarding the phenomenon of team care, and (c) examine contextual dimensions regarding the needs for and facilitators of team care.

Method

Because the concept of team care is underspecified in the scientific healthcare literature, we conducted a scoping review to synthesize the literature on team care. Scoping reviews are an increasingly popular method used to synthesize the large volume of health knowledge being produced, in both emergent and established fields (Colquhoun, Citation2014). They are appropriate both for clarifying key concepts and definitions in the literature and for identifying key characteristics or factors related to a concept, in contrast to systematic reviews, which aim to evaluate and synthesize research conducted on a given topic (Munn et al., Citation2018). The methodology for this scoping review was based on Arksey and O’Malley’s (Citation2005) framework and subsequent recommendations by Levac et al. (Citation2010). The review included five main stages: (a) identifying the research question; (b) identifying relevant literature; (c) selecting literature; (d) charting the data; and (e) collating, summarizing, and reporting the results. A detailed review protocol can be obtained from the first author upon request.

Identifying the research question

The review was guided by the following research question: How does the scientific literature in health care describe team care? As mentioned above, for the purposes of this study, team care was defined as the relational and compassionate dimensions of communication involved in teamwork and collaboration in healthcare contexts, related to but distinct from the rational and task-oriented dimensions. “Team” was broadly defined as a situation or context where healthcare workers collaborated and can include healthcare professionals providing care to patients, managers supervising and supporting these professionals, and organizations who employ and support both care providers and managers.

Identifying relevant literature

Following a consultation with a specialist subject librarian, the initial search was completed between July 4 and 16, 2021, in 8 electronic databases: Medline (biomedical sciences); CINAHL (nursing and allied health); and PsychINFO, Web of Science, Social Science Abstracts, Communication Abstracts, Business Source Premier, and Sociological Abstracts (social sciences, including social and community services, psychology, mental health, and community health). These databases were selected to be comprehensive and to cover a broad range of disciplines. The database search was limited to publications in English and French (languages the authors read fluently), and between 1996 to 2021. This 25-year timespan was chosen because many healthcare systems have undergone major reforms during this period, in part in response to an aging population and increasingly complex care needs. In many contexts, reforms included significant cuts to staffing (Nutt & Keville, Citation2016), the adoption of team-based care (Baik, Citation2017), and the implementation of rational management of resources (e.g., Sloan et al., Citation2014). This time period of increased complexity also marks reported increases in burnout among healthcare workers (Reith, Citation2018; Samra, Citation2018).

The search query consisted of terms the authors considered to describe team care and the contexts in which it takes place: collaboration, collective compassion, health care, and communication, using a variety of synonyms to account for different conceptions of teamwork and variation in communication practices. The search query, with synonyms of keywords, was tailored to the specific requirements of each database (see Additional file 1). Because we were interested in how team care is both conceptualized and operationalized, we included empirical studies as well as editorials and other types of articles. We also adopted a snowball technique to search the references lists of texts that made the final cut for articles that appeared relevant to the review.

Selecting relevant literature

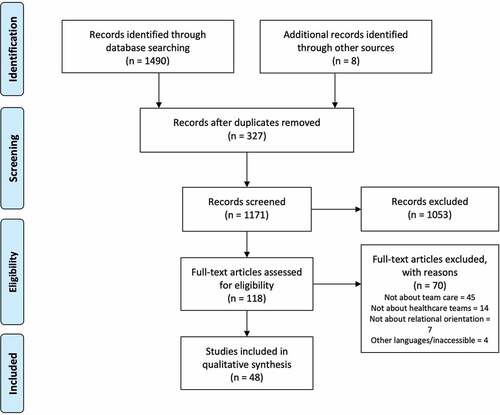

summarizes the study selection process.

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram for team care scoping literature search and review.

The database searches using the above terms yielded 1490 results of texts published between 1996 and 2021. Using a shared Excel sheet, the first two authors screened all titles and abstracts. Texts were retained for further examination (i.e., a reading of the full text) if the abstract and title met one or more of the following inclusion criteria, following our research goal and our understanding of team care: the text (1) concerned relational team communication and compassion; (2) focused on the need for team compassion; (3) discussed the relational dimensions of teamwork and collaboration; or (4) examined how team members, managers, or organizations facilitate the provision of relational support. Because we were interested in the compassionate relational and emotional dimensions of teamwork in healthcare contexts, texts were excluded if (1) they did not discuss, even peripherally, caring for team members (e.g., they focused exclusively on individual level issues such as self-care or they focused on education interventions rather than on teamwork); (2) they were not about healthcare teams (e.g., they focused on patient outcomes, actions, or satisfaction; on relationships between healthcare providers and patients and families; on non-clinical contexts such as the military; or on other non-healthcare topics, such as climate change); (3) they had a cognitive rather than relational orientation (e.g., a focus on logistics, task coordination, or knowledge sharing rather than affective needs); and (4) they were in a language other than French or English; or (5) they were unobtainable by interlibrary loan. We did not include or exclude texts based on methodological approach or type of article (e.g., empirical study, discussion paper) because we were interested in how team care is conceptualized. Disagreements were discussed through close reading and reapplication of the selection criteria.

Applying these criteria, which were iteratively refined throughout the process, resulted in 118 texts for possible inclusion. We then read the full text versions, reapplying the inclusion and exclusion criteria. In total, 48 texts were included in our review.

Charting the data

Informed by our research question, the first and second authors used a shared spreadsheet to coordinate data extraction of the following elements from each text, when identifiable: type of text (i.e., empirical research report, literature review, discussion article); definitions of team care (i.e., how caring for team members was conceptualized, including related processes); needs for team care; barriers to and facilitators of team care; and intended outcomes of team care. Extracting this data allowed us to account for a recurring pattern we noticed when reading the full texts, namely that team care seemed to be contextualized in a system of inputs, processes, and outputs.

Collating and summarizing

Next, we interpreted this extracted and charted data to begin to provide a conceptual overview of what constitutes team care in healthcare organizations, which was the purpose of this scoping review. (We discuss collating and summarizing here; reporting will occur in the findings section below.) Our research question and specific goals guided this step.

As we collated the extracted data to map the conceptual contours of team care in the literature, it became obvious that none of the texts provided explicit definitions of team care. For instance, the relational and compassionate dimensions of collaboration were often mentioned in texts focusing on individual resilience or on providing compassionate patient care. Therefore, to start to build a definition of team care, we iteratively worked to create broad categories that captured what seemed to be the “essence” of team care in each text. These essences ranged from discussing specific communication behaviors and practices to more vague discussions of the environment or climate of team care. Thus, we grouped together those discussing communication into three categories: sharing; supporting; and leadership as communication practice. These categories informed our emergent theme, “Communication practices that constitute team care,” to describe how team care is “done” at the level of interactions. Then we grouped the essences that discussed the contexts of team care, which we further refined into the categories of team culture and organizational climate. These informed the theme “Environmental conditions of team care.”

These definitions and environmental conditions informed our emerging account of team care as a contextual system of inputs, processes, and outputs. However, the retained texts did not necessarily or specifically discuss inputs or outputs, but rather needs and outcomes, which can be considered catalysts of and targets for team care; they help to explain why team care is an important organizational phenomenon, especially in light of the crisis situation in many healthcare systems. Therefore, we grouped together the mentioned needs for team care, which resulted in three categories: organizational and systemic issues; challenging contexts of care; and consequences experienced at the individual level. These informed the third theme, “Contextual challenges: Why team care is needed.” We also grouped together the intended outcomes of team care, resulting in four categories: bolstered individual resilience; improved individual and team well-being; better compassionate care; and improved team and organizational functioning. “Anticipated outcomes” became our fourth theme.

Putting together these elements – contextual challenges and needs for team care, its defining “essences” and contextual conditions, as well as its outcomes – allowed us to organize the data from the retained texts into a model to report on team care as a systemically situated and contextualized set of processes that can involve several communication practices. The model is, in part, our answer to the question: How does the scientific literature in health care describe team care? It provides a view of team care that is contextualized, complex, and oriented to several goals. It is reported in the next section along with the other results (see ).

Figure 2. Conceptual model of team care.

Reporting results

The literature search and selection resulted in 48 retained texts. Of these, 34 reported on empirical studies (19 qualitative, 4 quantitative, 2 mixed method, 7 program intervention descriptions, and 2 research protocols, which we included for their conceptualization of team care), 9 were discussion articles, 2 were a cross between empirical studies and discussion articles, and 3 were reviews (1 scoping, 1 systematic, and 1 integrative). In what follows, we provide an overview of the results (see and ), and then map the conceptual and contextual contours of team care in the retained literature, organized by the four themes discussed above. We begin by sketching what the literature says about the contexts in which the need for team care arises, before outlining the conceptual and practical contours of what team care is, or its constitutive practices. We conclude with the hoped-for outcomes of team care.

Table 1. Defining team care.

Contextual challenges: Why team care is needed

Team care is a way to promote well-being. As such, it can serve as a salve for contextual challenges that are both the result of and contributing factors to the ongoing crisis in healthcare. In analyzing the retained literature, we noted a kaleidoscopic range of reasons why team care is needed in health care. We organized these reasons into three mutually influencing, contextual types of need for team care (see ). We start with macro issues at the institutional and organizational level and then discuss particularly challenging contexts of care. Subsequently, we present the consequences of these issues and challenges as experienced at the individual level.

Organizational and systemic issues

Important problems felt across healthcare systems create the conditions in which workers’ well-being is compromised. Reforms and funding cuts (Adriaenssens et al., Citation2017; Nutt & Keville, Citation2016) have resulted in the ongoing global nursing shortage (Wanzer et al., Citation2009; Wittenberg-Lyles et al., Citation2014) that puts extreme pressure on existing resources. These conditions in turn lead to organizational challenges, such as frequent turnover (Adriaenssens et al., Citation2017; M. Davis & Batcheller, Citation2020; James-Scotter et al., Citation2019) and poor retention and attrition (Apker et al., Citation2006; Edward, Citation2005; Grauerholz et al., Citation2020; James-Scotter et al., Citation2019; Vogel & Flint, Citation2021; Wanzer et al., Citation2009; Wittenberg-Lyles et al., Citation2014).

Consequently, working in organizations or units that are resource-constrained can lead to moral dilemmas and moral distress (DeBoer et al., Citation2021), where healthcare workers must act contrary to their values (Jones et al., Citation2016) because necessary resources are unavailable. Similarly, organizational decision-making barriers can lead to delayed care, a source of frustration and distress among healthcare workers (McCracken et al., Citation2021). The professional hierarchy is another source of stress as it can constrain the agency of lower status professionals (McCracken et al., Citation2021; Nissim et al., Citation2019; Pronost et al., Citation2008; Wanzer et al., Citation2009).

Organizational changes, such as changing role designations or assignments (Juvet et al., Citation2021) can also generate stress and negative emotions. Likewise, increasing caseloads, ongoing documentation requirements, and mandatory meetings can make work less meaningful for care professionals (Pangborn, Citation2017). Broadly speaking, healthcare workers suffer when the job demands imposed by their organization exceed the job resources provided (Hakanen et al., Citation2014).

Challenging contexts of care

Some contexts of care – by virtue of the type of problems for which care is provided – can be more emotionally challenging than others, and thus place a higher emotional burden on healthcare workers. In challenging contexts of care, relationships with coworkers are essential (Nutt & Keville, Citation2016), and team care can play an important role in promoting worker well-being.

Such challenging or difficult contexts were mentioned in 21 texts. Contexts included various forms of palliative, hospice, and end-of-life care (Fitch et al., Citation2016; Grauerholz et al., Citation2020; McConnell & Porter, Citation2017; Pangborn, Citation2017; Pronost et al., Citation2008) as well as oncology care (Dubois et al., Citation2020; McDonald et al., Citation2010; Nissim et al., Citation2019; Sands et al., Citation2008; Wittenberg-Lyles et al., Citation2014). Those working in mental health and child welfare were also reported to experience higher levels of stress (Strolin-Goltzman et al., Citation2020), as do those working in intensive care (Davis & Batcheller, Citation2020; Jones et al., Citation2016) and in organ donation (Dicks et al., Citation2020).

In all contexts, the death of a patient or the occurrence of medical error or adverse event was a significant source of stress that could be alleviated through team care (Woolhouse et al., Citation2012). Moreover, external events outside of immediate contexts of care, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, can make regular working environments extraordinarily stressful contexts of care (Albott et al., Citation2020; Juvet et al., Citation2021; Owen & Schimmels, Citation2020; Vogel & Flint, Citation2021; Walker & Efstathiou, Citation2020).

Consequences experienced at the individual level

Of the retained literature, 22 texts described how these contextual challenges translate into a variety of problems and negative emotions experienced by healthcare workers. They ranged from high levels of occupational stress (Adriaenssens et al., Citation2017) and decreased job satisfaction (James-Scotter et al., Citation2019; McDonald et al., Citation2010; Trzpuc & Martin, Citation2011; Wanzer et al., Citation2009; Wittenberg-Lyles et al., Citation2014) to compassion fatigue (Aburn et al., Citation2020; Dicks et al., Citation2020; Jones et al., Citation2016; Nissim et al., Citation2019; Strolin-Goltzman et al., Citation2020; Woolhouse et al., Citation2012), moral distress (M. Davis & Batcheller, Citation2020; DeBoer et al., Citation2021; Grauerholz et al., Citation2020; Jones et al., Citation2016; McCracken et al., Citation2021; Pavlish et al., Citation2016), secondary trauma (Dicks et al., Citation2020; Strolin-Goltzman et al., Citation2020; Woolhouse et al., Citation2012), and burnout (Aburn et al., Citation2020; Adriaenssens et al., Citation2017; DeBoer et al., Citation2021; Dubois et al., Citation2020; Fitch et al., Citation2016; Grauerholz et al., Citation2020; Haizlip et al., Citation2020; James-Scotter et al., Citation2019; Matheson et al., Citation2016; McCracken et al., Citation2021; Nissim et al., Citation2019; Pronost et al., Citation2008).

These problems could be alleviated through team care. However, as mentioned above, the conceptof team care remained relatively indistinct in the retained literature. Therefore, our analysis focused on assembling a more demarcated definition of team care based on how it is operationalized, which we present next.

Communication practices that constitute team care

Team care is an inherently communicational phenomenon that takes place in interactions between people who work together or are members of the same organization. It can alleviate stress in multiple ways, as captured by three interrelated categories of communication practices that emerged from our analysis: sharing; supporting; and leading with compassion. Each category adopts a slightly different focus but together they describe how team care is communicatively constituted.

Sharing

Sharing was the most frequently mentioned communication practice of team care: 18 texts explicitly discussed the therapeutic benefits of talking about difficult experiences with colleagues or other organizational members. Sharing can take many forms, ranging from formal to informal; sharing generally helps healthcare workers to emotionally make sense of difficult experiences, such as patients dying, moral distress, medical errors, and adverse events. It also helps them to overcome a sense of isolation in their suffering and to reinforce solidarity.

Almost all of the texts (16) discussed established organizational practices, specific programs, or initiatives that sustain sharing. For instance, 6 texts mentioned the benefits of debriefing with colleagues or pastoral services, especially in challenging contexts of care such as after a death in pediatric palliative care (Fitch et al., Citation2016; Grauerholz et al., Citation2020; Minguet & Blavier, Citation2018; Rushton et al., Citation2006), in crisis mental health care (Edward, Citation2005), or during the COVID-19 pandemic (D. Davis & Batcheller, Citation2020). Two texts discussed Schwartz Rounds, which are designed for team members to talk about the non-clinical, social, and emotional aspects of care (Goodrich, Citation2012; Shuldham, Citation2017).

Sharing can be promoted through narrative practice (Pangborn, Citation2017; Walker & Efstathiou, Citation2020), such as reading aloud to teammates one’s stories of experienced challenges in order to build empathy and team spirit (Sands et al., Citation2008). Sharing can take the form of collective reflection on a difficult issue with the help of a facilitator to build emotional intelligence among colleagues (James et al., Citation2018). It also occurs in support groups with other professionals who are struggling with similar issues (Lane et al., Citation2018; Wittenberg-Lyles et al., Citation2014). Sharing also occurs through employee-led initiatives, such as the creation of a WhatsApp group to share “serious or fun information” to promote a sense of belonging (Juvet et al., Citation2021, p. 7). The concept of “interprofessional empathy” (Fitch et al., Citation2016) captures what happens when colleagues stay vulnerable and open to dialogue and sharing with one another. In sum, sharing validates emotions, normalizes reactions to trauma and stress, and promotes a feeling of collective efficacy (Albott et al., Citation2020).

Supporting

Supporting was the next most frequently mentioned communicative practice of team care: 12 texts considered the relational aspects of team care, ranging from unspecific mentions of the importance of social support (Dicks et al., Citation2020; James-Scotter et al., Citation2019) to much more specific discussion of what constitutes support. Seven texts considered how to provide supportive communication to colleagues (Apker et al., Citation2006; DeMarco et al., Citation2000; Haizlip et al., Citation2020; Nutt & Keville, Citation2016; Simpson, Citation2008; Sur, Citation2021; Zelenski et al., Citation2020). For instance, several discussed some form of displaying consideration for others as a means to promote affiliation, foster connection, and strengthen emotional bonds. This can manifest as showing respect (Apker et al., Citation2006; Simpson, Citation2008), noticing and affirming the colleague in need of support (Nutt & Keville, Citation2016; Pronost et al., Citation2008; Zelenski et al., Citation2020), empathically taking their perspective (Sur, Citation2021), and openly letting them know that they “matter” (Haizlip et al., Citation2020) and are valued as individuals and as colleagues (DeMarco et al., Citation2000).

Two texts explicitly discussed supportive communication in the service of building team relationships (Apker et al., Citation2006) by showing commitment to the team and to collaborative efforts (DeMarco et al., Citation2000). Two texts focused on communication styles that can reduce the anxiety of collaborators and create psychological safety in interactions: McDonald et al. (Citation2010) studied supportive versus unsupportive conversations between nurses and midwives, and Wanzer et al. (Citation2009) examined physicians using patient-centered communication practices in their interactions with nurses to promote nurses’ well-being. Overall, supporting was a way to let colleagues feel valued.

Leading with compassion

Leading with compassion was the definition of team care in 8 texts, where leadership was seen as communicative practice that fosters or constitutes team care. Vogel and Flint’s (Citation2021) discussion piece explains that leaders having “compassion for the compassionate” is a key component of compassionate patient care. All 8 texts concurred that the process of compassionate leadership lies in deeply listening, suspending judgment, and being empathic and responsive. Dewar and Cook (Citation2014) explain that such leadership is less focused on procedure (i.e., command-focused) and more on relational quality. It manifests in interactions by being available to staff (Juvet et al., Citation2021), by paying close attention to the quality of relationships (Vogel & Flint, Citation2021) and to staff’s situations and their needs (Hewison et al., Citation2019), and by being authentic and vulnerable as leaders (Steinbinder & Sisneros, Citation2020).

Thus, the content in this category was similar to that of the previous two categories, with a key difference being that, by virtue of their roles, managers and other formal leaders have the authority that other members might not have to take certain actions that were deemed compassionate. For instance, leaders can start team meetings by checking in with team members and by leaving time for questions and the expression of fears and concerns (Juvet et al., Citation2021). They can have caring conversations with staff (Dewar & Cook, Citation2014) where they look for and know to recognize signs of distress (Pavlish et al., Citation2016), especially with staff who are isolated, such as in community care (McComiskey, Citation2017). They can also adapt schedules to employees’ needs (Juvet et al., Citation2021), provide information on coping and link employees with other available resources (Owen & Schimmels, Citation2020), and use a “warm, compassionate interaction style” even “when under pressure” (Hewison et al., Citation2019, p. 266). Overall, compassionate leadership is thought to foster a culture of care on the team (Pavlish et al., Citation2016), which contributes to the environment in which team care practices take place. We turn now to the environmental conditions that foster team care.

Environmental conditions that foster team care

The workplace environment was mentioned in several texts as essential to supporting individual and collective well-being. In this sense, environmental conditions can foster or even constitute team care, either in terms of a caring team culture or as organizational supports.

Caring team culture

A supportive team or unit was mentioned in 8 texts as an environment that supports team members and encourages empathy, compassion, and attention to the relational dimensions of work relations. Three texts asserted that a caring team culture contributes to a socially supportive work environment, for instance by reminding members of their social connectedness (Albott et al., Citation2020) and that they can count on one another (Pronost et al., Citation2008), which can make work more meaningful (Pangborn, Citation2017). Three texts emphasized the role of team culture in establishing the norm of psychological safety and creating a safe space for team members to express and share vulnerability (Matheson et al., Citation2016; McConnell & Porter, Citation2017; Nissim et al., Citation2019).

A supportive team can promote individual resilience by acting as a buffer against difficult working conditions and traumatic experiences (Edward, Citation2005; Matheson et al., Citation2016), thereby improving job satisfaction and work engagement and reducing turnover intention and burnout (Adriaenssens et al., Citation2017). However, one discussion paper (Aburn et al., Citation2020) suggested that resilience is best understood at the collective level as socially constructed in the relationships one has with one’s social environment. Hence, it is team resilience that supports well-being and enables workers to continue in the face of difficult circumstances.

Conversely, the lack of a caring team culture can be a barrier to the communicative practices of team care between individuals (Jones et al., Citation2016). For instance, it can be difficult to support colleagues or to share one’s vulnerability with them when the team, unit, or organizational culture promotes maintaining a stiff upper lip in the face of emotional challenges (Nissim et al., Citation2019). Similarly, a lack of team cohesion or even a “toxic culture” was mentioned as inhibiting the communication practices of team care (Pangborn, Citation2017).

Organizational supports

Organizational supports that foster team well-being and team care were mentioned in 8 texts. Mentions of organizational supports ranged from those that were relatively unspecific to those that discussed particular organizational resources. For instance, Matheson et al. (Citation2016) generically mention the importance of strong management support in challenging environments (this differs from leading with compassion in that no specific communication practices were mentioned). Similarly, Goodrich (Citation2012) broadly suggests that staff experience can be improved when the organization offers support rather than punishments or rewards. On the more specific end, organizations can provide supports that address team members’ mental health needs, such as routinely having psychologists or even pet therapy on the unit for staff (McCracken et al., Citation2021), or a dedicated multidisciplinary team to care for clinicians in need of support (Lane et al., Citation2018), especially after a patient death.

A common thread across these texts was the accessibility and permanence of supports (McCracken et al., Citation2021; Minguet & Blavier, Citation2018), so that employees can easily take advantage of supports on an ongoing basis. Accessibility can be bolstered through clear signposting, for instance to sources of grief support (Walker & Efstathiou, Citation2020), which signals organizational commitment to collective well-being. This commitment is also signaled through dedicated spaces and scheduled time for support activities, such as debriefing and grief counseling (Minguet & Blavier, Citation2018; Nissim et al., Citation2019). Similarly, when the built environment enables accessibility to others, team care is facilitated (Trzpuc & Martin, Citation2011). As a whole, organizational supports for collective well-being and team care help to build a caring organization (Goodrich, Citation2012).

Anticipated outcomes of team care

Just as the needs for team care are multidimensional, so are the potential outcomes. However, we cannot identify or verify causal or correlational relationships between team care and outcomes, because our goal was not to evaluate the quality of the research studies, the appropriateness of their methods, nor the robustness of the findings. Rather, we report on the relationships suggested in the retained texts between team care practices and potential outcomes, as these relationships inform our understanding of team care as contextualized in a system of organizational processes (see the right-hand side of ).

We already discussed several outcomes regarding individual and team well-being in our presentation of what constitutes team care. Therefore, in what follows, we present three other intersecting categories of potential outcomes that emerged from our analysis: enhanced individual resilience; improved patient care and health outcomes; and better team and organizational functioning.

Bolstered individual resilience

Improved individual resilience was a frequently mentioned outcome for team care, discussed in 12 texts. More precisely, team care practices and team well-being may well be important mechanisms that support individual resilience (Aburn et al., Citation2020; Edward, Citation2005; Matheson et al., Citation2016; Sands et al., Citation2008). For instance, Davis and Batcheller (Citation2020) suggest that managing a team’s collective moral distress benefits individual resilience. Similarly, in palliative care, when the care team thrives, individual resilience may improve (Grauerholz et al., Citation2020).

The link between team- or peer-based support and individual resilience may be especially significant after adverse events (Lane et al., Citation2018; Wittenberg-Lyles et al., Citation2014). Indeed, since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, resilience has attracted increased research attention. Three studies that discussed workplace challenges during the pandemic noted that feeling supported by peers and other organizational members boosted individual resilience (e.g., by acting as “psychological first-aid”) and prevented burnout (Albott et al., Citation2020; Juvet et al., Citation2021; Owen & Schimmels, Citation2020).

Better compassionate patient care

Team care may lead to better care and improved health outcomes for patients. More specifically, collective empathy for colleagues may facilitate empathy and foster more compassionate connections with patients and families (Dewar & Cook, Citation2014; Fitch et al., Citation2016; Goodrich, Citation2012; Haizlip et al., Citation2020; Jones et al., Citation2016; McConnell & Porter, Citation2017; Rushton et al., Citation2006; Shuldham, Citation2017; Sur, Citation2021; Zelenski et al., Citation2020). When organizational support attenuates healthcare workers’ moral distress, workers are able to provide better care to families (McCracken et al., Citation2021). More broadly, Nutt and Keville (Citation2016) propose that patients and families benefit when healthcare decision makers prioritize a long-term focus on relational value in health care – which manifests through support and resources for team care – over short-term and financially driven considerations of efficiency.

Improved team and organizational performance

By fostering connection, empathy, tolerance, and attunement with one another, team care practices can also lead to better teamwork and organizational functioning (M. Davis & Batcheller, Citation2020; DeMarco et al., Citation2000; Goodrich, Citation2012; Minguet & Blavier, Citation2018; Shuldham, Citation2017; Zelenski et al., Citation2020), particularly during crises and after patient deaths (Albott et al., Citation2020; Dicks et al., Citation2020; Juvet et al., Citation2021). Supportive team care is also thought to improve team and organizational performance by boosting job satisfaction and retention (Wanzer et al., Citation2009) and lowering turnover intentions (Adriaenssens et al., Citation2017; James-Scotter et al., Citation2019).

Discussion

This scoping review examines the phenomenon of team care for the care team, that is, the relational and compassionate dimensions of communication involved in teamwork and collaboration in healthcare contexts, related to but distinct from rational and task-oriented dimensions of health care. Its goal was to provide greater conceptual clarity about team care and to examine the contextual dimensions regarding the needs and facilitators of team care. Analysis of the 48 retained texts identified three broad types of communicative practice that constitute team care: sharing; supporting; and leading with compassion. The environmental conditions facilitating team care discussed included a caring team culture and specific and accessible organizational supports. These results were crystallized into a conceptual model of team care () that situates team care within a system of team and organizational needs and anticipated outcomes.

Overall, our analysis indicates that the notion of team care remains conceptually underdeveloped in the surveyed literature, even if its constitutive practices in fact may be prevalent in some healthcare contexts such as nursing. This underdevelopment might be due to a methodological reliance on individual rather than collective measures in research on healthcare workplaces, such as resilience, turnover intention, job satisfaction, and so on (Aburn et al., Citation2020; Adriaenssens et al., Citation2017; Wanzer et al., Citation2009) and to the multitude of understandings in healthcare literature of what constitutes a team.

Although this scoping review allowed us to map out and categorize literature on team care in healthcare contexts, it has several limitations. First, given the existence of a budding literature on compassionate and supportive communication in the workplace (e.g., Mikkola, Citation2020; Miller, Citation2007; Way & Tracy, Citation2012), it was surprising that texts from communication were relatively absent from our literature search results even though we searched in communication and social science databases (excepting Apker et al., Citation2006; Pangborn, Citation2017, and Wittenberg-Lyles et al., Citation2014). Within the databases we used, pertinent texts may have been overlooked because they did not contain the word “team” or “collaboration” or their synonyms. What seems clear, however, is that there is a lacuna in the healthcare literature on teamwork and collaboration when it comes to their relational and affective dimensions, in favor of a focus on task coordination and information exchange (Fox et al., Citation2019). Thus, there is opportunity for communication scholars to contribute here.

Second, although scoping reviews allow researchers to describe and organize a vast evidence base, they do not seek to assess the robustness of research design or the quality of methods used (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005). Hence, our scoping review has focused on commonalities, which has enabled us to develop our model, but we cannot account for contextual idiosyncrasies nor make evidence-based claims about best practices of team care. Nonetheless, our model offers a helpful conceptual tool for future studies investigating team care.

These studies are needed. Given the documented suffering of healthcare workers in resource-constrained and challenging contexts of care (e.g., DeBoer et al., Citation2021; McCracken et al., Citation2021) as well as the ubiquity of collaboration and teamwork in health care, it is imperative that the concept of team care be more fully fleshed out so that its practice can become broadly and mindfully implemented in healthcare organizations. In this regard, our scoping review demonstrates that team care practices take place in interpersonal communication between healthcare workers, but that these practices must be explicitly supported and facilitated by healthcare organizations, whether in terms of space, time, and compensation for meetings, organizational recognition of the importance of team care, or hierarchical leaders who champion team care in their spheres of influence. Without this support, efforts to provide team care can further tax the resources of overburdened and stressed healthcare workers.

Similarly, our analysis demonstrated that leadership is a key component of this organizational support and the creation of caring team climates (Jones et al., Citation2016; Strolin-Goltzman et al., Citation2020). There was a strong focus in the retained literature on the important role played by nurse leaders in cultivating caring team climates. In fact, almost all retained texts on team care and leadership came from nursing (Dewar & Cook, Citation2014; McComiskey, Citation2017; Owen & Schimmels, Citation2020; Pavlish et al., Citation2016; Vogel & Flint, Citation2021). This is not surprising, given that caring and collaboration are part of nursing culture (Apker et al., Citation2006), and that there is a push in the professional culture of nursing to develop leadership skills. Furthermore, while physicians are generally understood as de facto leaders in interprofessional collaboration due to their position in the professional hierarchy (McCracken et al., Citation2021; Pronost et al., Citation2008; Wanzer et al., Citation2009), they may not actually be trained to engage in the relational maintenance that is at the heart of team care. Therefore, professional but especially interprofessional education must incorporate training in the practices of team care.

At the level of macro discourses in health care, the Quadruple Aim ought to take in account team care and the relational dimensions of collaboration in its fourth element that considers healthcare worker well-being. Similarly, team care should be considered in organizational reforms that target the efficiency of organizational processes (Nutt & Keville, Citation2016). This would call for more quantitative research on team care to link constructs to processes, such as the impact of opportunities for team debriefing on collective resilience. Future quantitative research on team care could also investigate the mechanisms by which team care mitigates problems analytically constructed at the individual level (e.g., moral distress, turnover intentions) and results in individual, team, and organizational level outcomes, such as resilience. In this regard, team resilience needs to be further conceptualized and empirically examined. Future qualitative studies could examine how team care is experienced and might best be implemented in particular contexts, such as palliative and oncology care.

Conclusion

This scoping review highlights the importance of the relational and affective dimensions of teamwork and collaboration that constitute team care in healthcare contexts. Even though the retained literature conceptualizes team care as contributing to improved worker well-being and resilience, improved patient care and outcomes, and enhanced team and organizational functioning, governments and private providers should not instrumentally use team care as a crutch to support workers’ functioning in an overstretched and under-funded healthcare system. Instead, we call upon them to recognize the inherent value of the well-being of workers for whom everyday work can be a crisis when resources are thin and workloads are becoming more demanding and complex. Thus, team care resources, such as requisite time and space, must be built into planned and funded collaborative processes (e.g., training, organizational planning and resource-allocation decisions, and even determination of leadership responsibilities). Organizational and academic-practitioner initiatives along these lines would allow healthcare organizations to better promote and support team care for the care team.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aburn, G., Hoare, K., Adams, P., & Gott, M. (2020). Connecting theory with practice: Time to explore social reality and rethink resilience among health professionals. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 26(6), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijn.12893

- Adriaenssens, J., Hamelink, A., & van Bogaert, P. (2017). Predictors of occupational stress and well-being in first-line nurse managers: A cross-sectional survey study. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 73, 85–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.05.007

- Aiken, L., Rafferty, A. M., & Sermeus, W. (2014). Caring nurses hit by a quality storm. Nursing Standard, 28(35), 22–25. https://doi.org/10.7748/ns2014.04.28.35.22.s26

- Albott, C. S., Wozniak, J. R., McGlinch, B. P., Wall, M. H., Gold, B. S., & Vinogradov, S. (2020). Battle buddies: Rapid deployment of a psychological resilience intervention for health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Anesthesia and Analgesia, 131(1), 43–54. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000004912

- Apker, J., Propp, K. M., Zabava Ford, W. S., & Hofmeister, N. (2006). Collaboration, credibility, compassion, and coordination: Professional nurse communication skill sets in health care team interactions. Journal of Professional Nursing, 22(3), 180–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.profnurs.2006.03.002

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Methodological framework of scoping studies. International Journal of Social Research Methodology: Theory and Practice, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Baik, D. (2017). Team-based care: A concept analysis. Nursing Forum, 52(4), 313–322. https://doi.org/10.1111/nuf.12194

- Barsade, S. G., & O’Neill, O. A. (2014). What’s love got to do with it? A longitudinal study of the culture of companionate love and employee and client outcomes in a long-term care setting. Administrative Science Quarterly, 59(4), 551–598. https://doi.org/10.1177/0001839214538636

- Berwick, D. M., Nolan, T. W., & Whittington, J. (2008). The triple aim: Care, health, and cost. Health Affairs, 27(3), 759–769. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.27.3.759

- Bodenheimer, T., & Sinsky, C. (2014). From triple to quadruple aim: Care of the patient requires care of the provider. Annals of Family Medicine, 12(6), 573–576. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1713

- Canadian Medical Association. (2022). Canada’s health care crisis: What we need now. https://www.cma.ca/news/canadas-health-care-crisis-what-we-need-now

- Canadian Medical Protective Association. (2007). Collaborative care: A medical liability perspective. https://www.cmpa-acpm.ca/en/advice-publications/handbooks/collaborative-care-summary

- Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., O‘Brien, K., Straus, S., Tricco, A. C., Perrier, L., Kastner, M., Moher, D. (2014). Scoping reviews: Time for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 67(12), 1291–1294. https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/pzx074

- Davis, M., & Batcheller, J. (2020). Managing moral distress in the workplace: Creating a resiliency bundle. Nurse Leader, 18(6), 604–608. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mnl.2020.06.007

- DeBoer, R. J., Mutoniwase, E., Nguyen, C., Ho, A., Umutesi, G., Nkusi, E., Sebahungu, F., Van Loon, K., Shulman, L. N., & Shyirambere, C. (2021). Moral distress and resilience associated with cancer care: Priority setting in a resource-limited context. The Oncologist, 26(7), e1189–1196. https://doi.org/10.1002/onco.13818

- DeMarco, R. F., Horowitz, J. A., & McLeod, D. (2000). A call to intraprofessional alliances. Nursing Outlook, 48(4), 172–178. https://doi.org/10.1067/mno.2000.103104

- Dewar, B., & Cook, F. (2014). Developing compassion through a relationship centred appreciative leadership programme. Nurse Education Today, 34(9), 1258–1264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2013.12.012

- Dicks, S. G., Burkolter, N., Jackson, L. C., Northam, H. L., Boer, D. P., & Van Haren, F. M. P. (2020). Grief, stress, trauma, and support during the organ donation process. Transplantation Direct, 6(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1097/TXD.0000000000000957

- Dubois, C. A., Borgès Da Silva, R., Lavoie-Tremblay, M., Lespérance, B., Bentein, K., Marchand, A., Soldera, S., Maheu, C., Grenier, S., & Fortin, M. A. (2020). Developing and maintaining the resilience of interdisciplinary cancer care teams: An interventional study. BMC Health Services Research, 20(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-05882-3

- Edward, K. L. (2005). The phenomenon of resilience in crisis care mental health clinicians. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 14(2), 142–148. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-0979.2005.00371.x

- Eisenberg, E. M. (2008). The social construction of healthcare teams. In C. P. Nemeth (Ed.), Improving healthcare team communication (pp. 9–20). Taylor & Francis. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781315588056-2

- Fernando, G. V. M. C., & Hughes, S. (2019). Team approaches in palliative care: A review of the literature. International Journal of Palliative Nursing, 25(9), 444–451. https://doi.org/10.12968/ijpn.2019.25.9.444

- Fitch, M., DasGupta, T., & Ford, B. (2016). Achieving excellence in palliative care: Perspectives of health care professionals. Asia-Pacific Journal of Oncology Nursing, 3(1), 66–72. https://doi.org/10.4103/2347-5625.164999

- Fox, S., Gaboury, I., Chiocchio, F., & Vachon, B. (2019). Communication and interprofessional collaboration in primary care: From ideal to reality in practice. Health Communication, 36(2), 125–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2019.1666499

- Goodrich, J. (2012). Supporting hospital staff to provide compassionate care: Do Schwartz Center Rounds work in English hospitals? Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 105(3), 117–122. https://doi.org/10.1258/jrsm.2011.110183

- Grauerholz, K. R., Fredenburg, M., Jones, P. T., & Jenkins, K. N. (2020). Fostering vicarious resilience for perinatal palliative care professionals. Frontiers in Pediatrics, 8, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2020.572933

- Haizlip, J., McCluney, C., Hernandez, M., Quatrara, B., & Brashers, V. (2020). Mattering: How organizations, patients, and peers can affect nurse burnout and engagement. Journal of Nursing Administration, 50(5), 267–273. https://doi.org/10.1097/NNA.0000000000000882

- Hakanen, J. J., Perhoniemi, R., & Bakker, A. B. (2014). Crossover of exhaustion between dentists and dental nurses. Stress and Health, 30(2), 110–121. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2498

- Hewison, A., Sawbridge, Y., & Tooley, L. (2019). Compassionate leadership in palliative and end-of-life care: A focus group study. Leadership in Health Services, 32(2), 264–279. https://doi.org/10.1108/LHS-09-2018-0044

- James, A. H., Rush, K. L., Janke, R., Duchscher, J. E., Phillips, R., & Kaur, S. (2018). Action learning can support leadership development for undergraduate and postgraduate nurses. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 94, 139–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.02.010

- James-Scotter, M., Walker, C., & Jacobs, S. (2019). An interprofessional perspective on job satisfaction in the operating room: A review of the literature. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 33(6), 782–794. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2019.1593118

- Jones, J., Winch, S., Strube, P., Mitchell, M., & Henderson, A. (2016). Delivering compassionate care in intensive care units: Nurses’ perceptions of enablers and barriers. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 72(12), 3137–3146. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.13064

- Juvet, T. M., Corbaz-Kurth, S., Roos, P., Benzakour, L., Cereghetti, S., Moullec, G., Suard, J.-C., Vieux, L., Wozniak, H., Pralong, J. A., & Weissbrodt, R. (2021). Adapting to the unexpected: Problematic work situations and resilience strategies in healthcare institutions during the COVID-19 pandemic’s first wave. Safety Science, 139, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2021.105277

- Lane, M. A., Newman, B. M., Taylor, M. Z., O’Neill, M., Ghetti, C., Woltman, R. M., & Waterman, A. D. (2018). Supporting clinicians after adverse events: Development of a clinician peer support program. Journal of Patient Safety, 14(3), e56–60. https://doi.org/10.1097/PTS.0000000000000508

- Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., & O’Brien, K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science, 5(69), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-69

- Lown, B. A., McIntosh, S., Gaines, M. E., McGuinn, K., & Hatem, D. S. (2016). Integrating compassionate, collaborative care (the “Triple C”) into health professional education to advance the triple aim of health care. Academic Medicine, 91(3), 310–316. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001077

- Madara, J. L. (2020). America’s health care crisis is much deeper than COVID-19. American Medical Association.

- Maiden, J., Georges, J. M., & Connelly, C. D. (2011). Moral distress, compassion fatigue, and perceptions about medication errors in certified critical care nurses. Dimensions of Critical Care Nursing, 30(6), 339–345. https://doi.org/10.1097/DCC.0b013e31822fab2a

- Matheson, C., Robertson, H. D., Elliott, A. M., Iversen, L., & Murchie, P. (2016). Resilience of primary healthcare professionals working in challenging environments: A focus group study. British Journal of General Practice, 66(648), E507–515. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp16X685285

- McComiskey, F. (2017). The fundamental managerial challenges in the role of a contemporary district nurse: A discussion. British Journal of Community Nursing, 22(10), 489–494. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjcn.2017.22.10.489

- McConnell, T., & Porter, S. (2017). The experience of providing end of life care at a children’s hospice: A qualitative study. BMC Palliative Care, 16(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-017-0189-9

- McCracken, C., McAndrew, N. S., Schroeter, K., & Klink, K. (2021). Moral distress: A qualitative study of experiences among oncology team members. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 25(4), E35–43. https://doi.org/10.1188/21.CJON.E35-E43

- McDonald, G. E., Vickers, M. H., Mohan, S., Wilkes, L., & Jackson, D. (2010). Workplace conversations: Building and maintaining collaborative capital. Contemporary Nurse, 36(1–2), 96–105. https://doi.org/10.5172/conu.2010.36.1-2.096

- Mikkola, L. (2020). Supportive communication in the workplace. In L. Mikkola & M. Valo (Eds.), Workplace communication (pp. 149–162). Taylor & Francis.

- Miller, K. (2007). Compassionate communication in the workplace: Exploring processes of noticing, connecting, and responding. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 35(3), 223–245. https://doi.org/10.1080/00909880701434208

- Minguet, B., & Blavier, A. (2018). Formalizing collective intervention to support individual resilience: Model of a post-event analysis in accompanying the deaths of children in hospital environment. Travail Humain, 3(81), 173–204. https://doi.org/10.3917/th.813.0173

- Munn, Z., Peters, M. D. J., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A., & Aromataris, E. (2018). Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18(143), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x

- Nissim, R., Malfitano, C., Coleman, M., Rodin, G., & Elliott, M. (2019). A qualitative study of a compassion, presence, and resilience training for oncology interprofessional teams. Journal of Holistic Nursing, 37(1), 30–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898010118765016

- Nolan, M. (2013). Creating an enriched environment of care for older people, staff and family carers: Relational practice and organizational culture change in health and social care. In M. A. Keating, A. M. McDermott & K. Montgomery (Eds.), Patient-centred health care: Achieving co-ordination, communication and innovation (pp. 78–89). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Nutt, K., & Keville, S. (2016). ‘ … You kind of frantically go from one thing to the next and there isn’t any time for thinking anymore’: A reflection on the impact of organisational change on relatedness in multidisciplinary teams. Reflective Practice, 17(2), 221–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2016.1159552

- Owen, R. D., & Schimmels, J. (2020). Leadership after a crisis: The application of psychological first aid. Journal of Nursing Administration, 50(10), 505–507. https://doi.org/10.1097/NNA.0000000000000925

- Pangborn, S. M. (2017). Reimagining interdisciplinary team communication in hospice care: Disrupting routinization with narrative inspiration. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 45(5), 455–473. https://doi.org/10.1080/00909882.2017.1382710

- Pavlish, C., Brown-Saltzman, K., So, L., & Wong, J. (2016). SUPPORT: An evidence-based model for leaders addressing moral distress. Journal of Nursing Administration, 46(6), 313–320. https://doi.org/10.1097/NNA.0000000000000351

- Pfaff, K. A., Freeman-Gibb, L., Patrick, L. J., Dibiase, R., & Moretti, O. (2017). Reducing the “cost of caring” in cancer care: Evaluation of a pilot interprofessional compassion fatigue resiliency programme. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 31(4), 512–519. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2017.1309364

- Pinna, M. (2022). On life support: Can France’s struggling healthcare system be saved? EuroNews Witness. https://www.euronews.com/2022/07/08/on-life-support-can-frances-struggling-healthcare-system-be-saved

- Pronost, A. M., Le Gouge, A., Leboul, D., Gardembas-Pain, M., Berthou, C., Giraudeau, B., & Colombat, P. (2008). Effet des caractéristiques des services en oncohématologie développant la démarche palliative et des caractéristiques sociodémographiques des soignants sur les indicateurs de santé: Soutien social, stress perçu, stratégies de coping, qualité de vie au tra. Oncologie, 10(2), 125–134. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10269-007-0775-1

- Pronost, A. M., Le Gouge, A., Leboul, D., Gardembas-Pain, M., Berthou, C., Giraudeau, B., & Colombat, P. (2008). Effet des caractéristiques des services en oncohématologie développant la démarche palliative et des caractéristiques sociodémographiques des soignants sur les indicateurs de santé: Soutien social, stress perçu, stratégies de coping, qualité de vie au travail [Effect of the characteristics of the oncohaematology departments developing a palliative approach and the socio-demographic characteristics of the caregivers on health indicators: Social support, perceived stress, coping strategies, and quality of life at work]. Oncologie, 10(2), 125–134. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10269-007-0775-1

- Reith, T. P. (2018). Burnout in United States healthcare professionals: A narrative review. Cureus, 10(12), e3681. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.3681

- Rushton, C. H., Reder, E., Hall, B., Comello, K., Sellers, D., & Hutton, N. (2006). Interdisciplinary interventions to improve pediatric palliative care and reduce health care professional suffering. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 932(4), 922–933. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2006.9.922

- Samra, R. (2018). Brief history of burnout. British Medical Journal, 363(December), 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k5268

- Sands, S. A., Stanley, P., & Charon, R. (2008). Pediatric narrative oncology: Interprofessional training to promote empathy, build teams, and prevent burnout. Journal of Supportive Oncology, 6(7), 307–312.

- Shuldham, C. (2017). Schwartz rounds help ease stress and foster teamwork. Nursing Standard, 32(13), 31–31. https://doi.org/10.7748/ns.32.13.31.s23

- Simpson, R. L. (2008). Caring communications: How technology enhances interpersonal relations (Part I). Nursing Administration Quarterly, 32(1), 70–73. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NAQ.0000305950.54063.76

- Sinclair, S., Kondejewski, J., Raffin-Bouchal, S., King-Shier, K. M., & Singh, P. (2017). Can self-compassion promote healthcare provider well-being and compassionate care to others? Results of a systematic review. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 9(2), 168–206. https://doi.org/10.1111/aphw.12086

- Sloan, T., Fitzgerald, A., Hayes, K. J., Radnor, Z., & Sohal, S. R. (2014). Lean in healthcare – History and recent developments. Journal of Health Organization and Management, 28(2), 130–134. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHOM-04-2014-0064

- Steinbinder, A., & Sisneros, D. (2020). Achieving uncommon results through caring leadership. Nurse Leader, 18(3), 243–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mnl.2020.03.010

- Strolin-Goltzman, J., Breslend, N., Deaver, A. H., Wood, V., Woodside Jiron, H., & Krompf, A. (2020). Moving beyond self-care: Exploring the protective influence of interprofessional collaboration, leadership, and competency on secondary traumatic stress. Traumatology, 1–8. online first. https://doi.org/10.1037/trm0000244

- Sur, D. (2021). Interprofessional Intentional Empathy Centered Care (IP-IECC) in healthcare practice: A grounded theory study. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 35(2), 175–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2020.1752162

- Trzpuc, S. J., & Martin, C. S. (2011). Application of space syntax theory in the study of medical-surgical nursing units in urban hospitals. Health Environments Research and Design Journal, 4(1), 34–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/193758671000400104

- Unützer, J., Harbin, H., Schoenbaum, M., & Druss, B. (2013). The collaborative care model: An approach for integrating physical and mental health care in Medicaid health homes. Medicaid Health Home Information Center. https://www.medicaid.gov/State-Resource-Center/Medicaid-State-Technical-Assistance/Health-Homes-Technical-Assistance/Downloads/HH-IRC-Collaborative-5-13.pdf

- Vogel, S., & Flint, B. (2021). Compassionate leadership: How to support your team when fixing the problem seems impossible. Nursing Management, 28(1), 32–41. https://doi.org/10.7748/nm.2021.e1967

- Walker, W., & Efstathiou, N. (2020). Support after patient death in the intensive care unit: Why ‘I’ is an important letter in grief. Nursing in Critical Care, 25(5), 266–268. https://doi.org/10.1111/nicc.12534

- Wanzer, M. B., Wojtaszczyk, A. M., & Kelly, J. (2009). Nurses’ perceptions of physicians’ communication: The relationship among communication practices, satisfaction, and collaboration. Health Communication, 24(8), 683–691. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410230903263990

- Way, D., & Tracy, S. J. (2012). Conceptualizing compassion as recognizing, relating and (re)acting: A qualitative study of compassionate communication at hospice. Communication Monographs, 79(3), 292–315. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637751.2012.697630

- Wilkinson, E. (2015). UK NHS staff: Stressed, exhausted, burnt out. The Lancet, 385(9971), 841–842. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60470-6

- Wittenberg-Lyles, E., Goldsmith, J., & Reno, J. (2014). Perceived benefits and challenges of an oncology nurse support group. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 18(4), E71–76. https://doi.org/10.1188/14.CJON.E71-E76

- Woolhouse, S., Brown, J. B., & Thind, A. (2012). Building through the grief: Vicarious trauma in a group of inner-city family physicians. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine, 25(6), 840–846. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2012.06.120066

- Zelenski, A. B., Saldivar, N., Park, L. S., Schoenleber, V., Osman, F., & Kraemer, S. (2020). Interprofessional improv: Using theater techniques to teach health professions students empathy in teams. Academic Medicine, 95(8), 1210–1214. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000003420