ABSTRACT

This study examines the effects of message framing (loss vs. gain) and format (narrative vs. expository) on intentions to discuss flu vaccination with a close social referent. We test the effects of video messages using a two-wave web-based randomized experiment among adults in Israel (baseline: N = 429, one-month follow-up: N = 241). Exposure to narrative messages was positively associated with intentions to discuss flu vaccination. Exposure to loss-framed messages was positively associated with increased likelihood of discussing vaccination with the referent at follow-up. Effects of message framing and format were moderated by concern for the referent’s health. Findings support the use of persuasive messages to motivate interpersonal conversation to promote vaccination. Results contribute to theory on risk-framing by showing that audiences may evaluate loss-framed messages according to their risk perceptions, when greater concern for health risks motivate action, not only for one’s own health but for another person’s health.

Vaccination is one of the most effective public health measures to prevent disease and has prevented and curbed the spread of diseases such as COVID-19, polio, measles, mumps, rubella, and influenza (World Health Organization [WHO], Citation2021). Influenza (flu) virus can cause mild to severe illness, particularly among high-risk groups pregnant women, people age 65 and over, and those with chronic illnesses (Ghebrehewet et al., Citation2016). The CDC recommends that eligible children and adults be vaccinated against the flu each year, which can reduce the risk of requiring medical treatment by 40% to 60% (CDC, Citation2022). Influenza rates vary over time and across countries. In Israel, the government recommends yearly vaccination for everyone above the age of 6 months (Israeli Ministry of Health, Citation2022).

Vaccine hesitancy is among the greatest public health threats to global health (World Health Organization [WHO], Citation2020). There is also concern that the COVID-19 pandemic may have led to a decline in public wiliness to vaccinate for other vaccines. While this trend has been observed in other countries, we do not yet see evidence that the pandemic has had a substantial impact on influenza vaccination in Israel, with adherence rates remaining stable since 2019 (OECD, Citation2023). In fact, according to OECD reports, 61% of Israeli adults aged 65+ were vaccinated against influence in Israel in 2021, an increase from 58.2% in 2018 (OECD, Citation2023). However, flu vaccination rates in Israel are still lower than recommended (Israel Center for Disease Control, Citation2020).

Research shows that the flu vaccine is effective (Ganczak et al., Citation2017), however, there is some debate surrounding its effectiveness, safety, and side effects. Concerns about the flu vaccine have been linked to low levels of public trust in pharmaceutical companies, in government health agencies that promote vaccination (Xu et al., Citation2020), lower trust in physicians (Borah & Hwang, Citation2021), and lower levels of health literacy (Rahman et al., Citation2022). Negative perceptions may also be reinforced by engagement with information about vaccination through social media platforms (Bradshaw et al., Citation2020), and exposure to vaccine misinformation and conspiracy theories (Lee et al., Citation2022).

Considering sub-optimal flu vaccination rates, it is important to understand which messages may be effective in promoting and influencing public vaccination intentions and behavior. This study builds on research that shows that message framing may influence responses to messages promoting vaccination (e.g., Gerend & Shepherd, Citation2007; Kim et al., Citation2019; Nan et al., Citation2015; Ye et al., Citation2021). Most studies have tested message effects on message recipient vaccination intentions or behavior. In contrast, we test message effects on intention to discuss flu vaccination with someone close to them, to leverage interpersonal influence to promote vaccination. In addition, studies have typically measured vaccine-related intentions post-exposure without assessing lagged effects (Penţa & Băban, Citation2017). This study tests the immediate effects of exposure to messages promoting discussion about the flu vaccine with a close other and lagged effects on behavior (reported discussion with the referent). In addition, we examine two moderators of effects – concern for the referent and message format (narrative vs. expository).

Social influence: Interpersonal conversations about flu vaccination

We are exposed to health information through various sources, including mass media channels, social media platforms, physician-patient interactions, and interpersonal communication. Health information from these sources can reinforce, shape, or change our knowledge, attitudes, and health behavior (Cline, Citation2003). This study tests messages aimed at motivating the recipient to discuss the flu vaccine with a close referent. This approach conceptualizes interpersonal communication not just as information delivery but as a consequential means of influencing behavior (Cappella, Citation1987).

The role of interpersonal communication in personal influence has been illustrated in classic communication research (Katz & Lazarsfeld, Citation1966). Those who can informally influence others in a desired way through disseminating information and sharing opinions have been referred to as opinion leaders (Katz & Lazarsfeld, Citation1966; Rogers, Citation2003). However, interpersonal communication with friends, family, and significant others, who are not necessarily defined as opinion leaders, can also influence behavioral intent (Fishbein & Ajzen, Citation2011). The role of interpersonal communication is also a key element in social cognitive theory (Bandura, Citation2002), which proposes that communication with others in our environment can shape our ideas about what are appropriate, desired, and expected behaviors and those most performed by similar others (Hornik & Yanovitzky, Citation2003). Interpersonal communication can also be particularly effective as it can be personal and tailored to the person being addressed, enhancing perceptions of personal relevance (Burnkrant & Unnava, Citation1989). Interpersonal communication can reinforce social support, linked to positive health outcomes (Uchino, Citation2006), and can increase knowledge and decrease uncertainty about the subject (Brashers et al., Citation2002).

Studies show that interpersonal communication is positively correlated with knowledge about the flu vaccine (Yin et al., Citation2022), and with perceptions of convenience and (reduced) side effects of the COVID-19 vaccine (Wang, Citation2022). Based on research demonstrating the importance of interpersonal conversations for vaccination behaviors (e.g., Heiss et al., Citation2015), we expect that interpersonal communication will influence vaccine-related outcomes, particularly when that information is relayed by someone close to the recipient. Our focus on motivating conversation about the flu vaccine is also consistent with media campaigns that have aimed to stimulate conversation as an outcome (e.g., Afifi et al., Citation2006; Hafstad & Aarø, Citation1997; Hornik & Yanovitzky, Citation2003).

Message framing

Health communication messages can frame the same behavior in different ways, primarily in terms of the gain or losses of a behavior, with varying persuasive effects. Message framing remains one of the most researched biases in persuasion and decision-making, and has been operationalized in varying ways (Penţa & Băban, Citation2017). Levin et al. (Citation1998) distinguished between three types of framing: “risky choice,” “attribute,” and “goal framing.” Goal framing is commonly tested in persuasion and health communication research and refers to the degree to which the message emphasizes the positive consequences of performing a behavior (gain frame), or the negative consequences of not performing a behavior (loss-frame).

Research on message framing has proposed that gain-framed messages may be more persuasive than loss-framed messages for disease prevention behaviors, and loss-framed messages more persuasive for disease detection behaviors (Rothman & Salovey, Citation1997). This hypothesis draws from prospect theory (Kahneman & Tversky, Citation1979; Tversky & Kahneman, Citation1981). A gain-framed message would emphasize the benefits of acting, (e.g., “If you are vaccinated against the flu, you will reduce your chance of becoming very ill this winter”). In contrast, a loss-framed message would emphasize the costs of refraining from action (e.g., “Not being vaccinated against the flu will increase your risk of becoming very ill this winter”). Many studies have tested the risk-framing hypothesis (van ’t Riet et al., Citation2014). However, the main effects of message framing are small or insignificant (Gallagher & Updegraff, Citation2012; O’Keefe & Jensen, Citation2006, Citation2007, Citation2009; O’Keefe & Nan, Citation2012). Similarly, a review of message framing in vaccine communication found limited evidence that goal framing influenced vaccine-related attitudes, intentions or behavior (Penţa & Băban, Citation2017).

In the context of vaccination, which is primarily a disease-prevention behavior, gain-framed messages have been hypothesized to be more persuasive than loss-framed messages in influencing individual vaccination intentions (Nan, Citation2012). However, message effects may also depend on the type of vaccination being promoted. For example, some vaccinations, such as the COVID-19 vaccination, may be seen as having a higher risk of adverse reactions compared with more established vaccines, such as the flu vaccine.

Studies testing framing effects on vaccination intentions have found that loss-framed messages promoting the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine (Gerend & Shepherd, Citation2007) and the MMR vaccine (Abhyankar et al., Citation2007) may have a stronger effect on vaccination intentions, compared with gain-framed messages. A recent study found that loss-framed messages promoting the COVID-19 vaccination among Chinese adults were (somewhat) more persuasive than equivalent gain-framed messages (Peng et al., Citation2021). Other studies have found no difference between loss- and gain-framed messages on influenza vaccination rates (e.g., McCaul et al., Citation2002). Thus, we examine whether there are (main) effects of framing on discussion intentions and behavior, as follows:

RQ1:

Will there be an effect of message framing on intentions to discuss the vaccine with a close other?

RQ2:

Will there be an effect of message framing on discussion about the vaccine with a close referent (at one-month follow-up)?

Concern for the other and message framing

Researchers have suggested that more evidence is needed to identify significant moderators of framing effects, both at the level of the message as well as the message recipient (O’Keefe, Citation2021; O’Keefe & Jensen, Citation2007, Citation2009). For example, research has tested whether personal involvement with the message topic moderates message-framing effects. Studies support the idea that framing effects should be stronger under conditions of greater concern or perceived relevance (Kiene et al., Citation2005; Maheswaran & Meyers-Levy, Citation2018; Millar & Millar, Citation2000; Rothman et al., Citation1999). However, this literature has tested the effects of framing on intentions to adopt a recommended behavior for oneself (Penţa & Băban, Citation2017), with less attention paid to framing effects on willingness to influence others to adopt a recommended behavior.

A review of message framing to promote vaccination found that characteristics of the message recipient moderated framing effects. For example, studies have tested the effects of message framing and motivational orientation (i.e., the tendency to approach favorable outcomes or to avoid unfavorable outcomes) on HPV vaccination intentions (Gerend & Shepherd, Citation2007; Nan, Citation2012) and flu vaccination (Shen & Dillard, Citation2007). These studies found that loss-framed messages were more effective at promoting HPV vaccination for avoidance-oriented participants than gain-framed messages (Gerend & Shepherd, Citation2007; Nan, Citation2012). However, no significant interaction between message framing and motivational orientation was found for flu vaccination intentions (Shen & Dillard, Citation2007).

Other studies have tested whether message framing effects may be moderated by perceived risk and susceptibility, when gain-framed messages may be more effective among individuals with lower risk perceptions, compared with loss-framed messages that may be more persuasive for audiences at higher risk (Updegraff et al., Citation2015). Park (Citation2012) found that loss-framed messages about HPV vaccination were more effective for participants in the high perceived risk condition, while gain-framed messages were more effective in the low perceived risk condition. However, other studies testing the risk-framing hypothesis have yielded inconclusive results, which may be related to differences in how risk was measured (van ’t Riet et al., Citation2014).

This study adopts an approach used by Gerend and Shepherd (Citation2007), who tested the effects of messages that emphasized the benefits of HPV vaccination or the costs of not being vaccinated and found that loss-framed messages were more effective at influencing vaccine intentions among participants who had multiple sexual partners and who infrequently used condoms. However, in contrast to studies that have tested whether the perceived risk to oneself moderates message framing effects, we test whether concern for the health of a close other will moderate the effects of message framing on discussion intentions and self-reported discussion at one-month follow-up. We expect that participants exposed to loss-framed messages will be more motivated to discuss the flu vaccine with a close other when they feel greater (vs. lesser) concern for the health of that referent. For this group, concerns for the potential risks of (their friend or family members’) non-vaccination may be a motivating factor to intervene. Thus, test the following hypothesis:

H1:

Exposure to a loss-framed message will have a stronger positive effect on (a) discussion intentions and (b) behavior (i.e., interpersonal discussion about the vaccine) when participants feel greater concern for the health of the referent if they do not get vaccinated.

Narrative format and message framing

Research on narrative persuasion draws from exemplification theory, which proposes that people may pay closer attention to information presented in the form of a specific case study compared with messages presenting equivalent information using statistical descriptions (Kreuter et al., Citation2007; Yu et al., Citation2010). Narratives are one type of message format, organized as a series of events and characters, typically relating a story from the first-person perspective (Green & Brock, Citation2000). A large body of research has tested the effects of narrative messages compared with non-narrative messages, including effects on promoting health behaviors (e.g., Baesler & Burgoon, Citation1994; Green, Citation2006).

This study tests whether message framing effects vary depending on message format. We expect that narrative messages will be more persuasive than non-narrative messages in motivating vaccine-related discussions. Messages presenting information about the flu vaccine using a first-person testimonial format should help the audience understand the issue more concretely and to imagine themselves in a similar scenario (Green & Brock, Citation2000; Kreuter et al., Citation2007). This proposition is also based on research showing that narrative messages were more persuasive than expository messages in influencing individual COVID-19 vaccine intentions (Ye et al., Citation2021) and other health behaviors (e.g., Liu et al., Citation2019). Furthermore, and in line with the hypothesized interaction of framing and concern for the other (H1), we expect that the effects of messages on intentions and discussion will be stronger among people who feel greater concern for the health of their close friend or family member, compared with those who are less concerned:

H2:

Exposure to narrative format messages will have a stronger positive effect on (a) discussion intentions and (b) behavior (i.e., interpersonal discussion about the vaccine), compared with expository messages.

H3:

Effects of exposure to narrative format messages on (a) discussion intentions and (b) behavior (i.e., interpersonal discussion about the vaccine) will be stronger among participants who feel greater concern for the health of the referent if they do not get vaccinated.

While we expect that narrative messages should be more persuasive (overall), compared with expository messages, research does not show conclusive evidence for the interaction of message format and message framing. For example, Ye et al. (Citation2021), tested the joint effects of message framing and message format among Chinese college students but did not find an interaction between narrative messages and message framing. Thus, we ask the following research questions:

RQ3:

Will message framing interact with format (narrative vs. expository) to influence intentions to discuss the vaccine with a close referent?

RQ4:

Will message framing interact with format (narrative vs. expository) to influence the likelihood of discussing the flu vaccine a close referent?

Method

Participants

The participants were 447 Israeli adults, recruited through an online survey company (Panel4all) in exchange for vouchers provided by the company to their panelists. Inclusion criterion included participants who reported knowing at least one person close to them who has was not vaccinated against the flu in the last three years. We used a three-year time span to account for the COVID-19 pandemic, which may have reduced access to flu vaccination, and increased the interim between the recommended annual flu vaccinations. We excluded participants who took less than seven minutes or over three hours to complete the survey (n = 8), leaving an analytic sample of 439 participants.

Participants’ age ranged from 18 to 76 years (M = 43.20, SD = 14.91). The sample included 252 females (57.4%) and 187 males (42.6%). Most participants (80.4%) had completed more than 12 years of school, and 280 had been vaccinated against the flu within the last year (63.8%). In line with Israel’s early adoption of COVID vaccination, most participants (69%, n = 298) reported having had three vaccinations (including the booster) against COVID. Only 2.1% of participants (n = 9) reported that they had never been vaccinated against COVID, and 0.5% that they had only received one vaccination (n = 2). The study uses two waves of data collected one month apart (during April and May 2022). Over half (54.9%) of the baseline survey respondents participated in the second wave (N = 241). The follow-up sample was similar to the baseline sample (see ).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics for baseline and follow-up surveys.

Design and procedure

We employed a 2 (message frame: gain vs. loss) by 2 (message type: narrative vs. expository) between-subjects factorial design. Participants provided informed consent and were randomly assigned to view one of 4 video messages about flu vaccination through the online study link (see for experimental conditions). They answered questions about their vaccination history, perceived risk of adverse health outcomes for a close other, demographics, manipulation checks for the independent variables, and vaccination discussion intentions. In the follow-up survey (one month after baseline), participants were asked whether they had discussed the flu vaccination with the referent and were debriefed.

Table 2. Experimental conditions and outcomes (M, SD).

The study measures were crafted by the researcher, who is proficient in English (native language) and Hebrew (highly fluent) and coauthor (native Hebrew speaker). Thus, the measures were designed in accordance with the English-language measures from similar studies, but were also comprehensible to the study participants. The ethics review board of the University of Haifa approved all procedures. The study data are available at OSF repository: https://osf.io/c3q4k/?view_only=24f94f19c6a74990b40f1a74f9a9fc34

Stimulus and procedure

We developed four scripts for a short (three-minute) video featuring the same protagonist – “Alon” (a pseudonym), an actor who appeared to be of an age like that of the protagonist. Message content was uniform across conditions (besides manipulated factors). Two videos emphasized the benefits of having the flu vaccine for the other person, while two videos emphasized the risks of the other person not being vaccinated, using an approach based on prior research (e.g., Gerend & Shepherd, Citation2007). Within each of the framing message conditions, one video was written in a first-person narrative format, while the other presented the same information in an expository format (see Appendix). The messages were scripted in English, then translated to Hebrew, and narrated by our actor in Hebrew (his native language), with Hebrew language subtitles.

The texts were inserted into the video as subtitles to enhance audience comprehension. All videos were recorded in a professional studio on the same day, featuring the same actor in the same clothes and setting. To ensure that messages were comparable, we kept the length (approximately 620 words) and causal sequence consistent. Expository messages were structured similarly to the narrative messages but referred to the same information in a descriptive manner, without describing a specific family member or conversation. The message included a manipulation of framing (describing vaccination benefits or the risks of not being vaccinated), and concluded with the same call to action.

Measures: Dependent variable

Intention to discuss the flu vaccine with a close referent. Participants were asked to note their agreement with the statement, “I intend to initiate a conversation with a close friend or family member about the importance of them having a flu vaccine for their health within the next 3 months.” This item is worded in accordance with guidelines for measuring intention based on the integrative model of behavioral prediction (Fishbein & Ajzen, Citation2011). Responses were on a scale from 1 (“not at all”) to 7 (“definitely”) (M = 3.72, SD = 1.89).

Discussion with others. Participants in the follow-up survey were asked whether they had discussed the flu vaccine with a close friend or family member during the last month. Most respondents (61%) reported that they had discussed the topic (n = 147), while 39% (n = 94) had not discussed the flu vaccine with a close contact.

Measures: Moderator

Concern for the other: We asked participants to note their agreement with the following three statements: “The person I know whom I would want to speak with about the flu vaccine is at high risk of negative health outcomes if they don’t act,” “I am very worried about the health of the person I know [that I would speak to about the vaccine] if they don’t get vaccinated against the flu” and “If the person I want to speak with about the flu vaccine will not change their behavior this could cause them serious health problems in the future” with responses ranging from 1 = “strongly disagree” to 7 = “strongly agree.” The responses to these items were positively correlated (r = .71 to .79), and formed a reliable scale which was a mean of the responses to these three items (M = 3.19, SD = 1.81; α = .89).

Independent variables include the manipulations of message format (narrative vs. expository) and message framing (loss- vs. gain frame). Covariates include motivation orientation - a scale comprised of a combination of the BIS/BAS scale (Carver & White, Citation1994) which assesses the degree to which individuals may be responsive to message framing, using a procedure from prior research (Mann et al., Citation2004; Nan, Citation2012). We test hypotheses when accounting for participants’ motivation orientation as this trait may influence audience responses to message framing (Nan, Citation2012).Footnote1 Finally, as a small group of participants (n = 29) were accidentally sent the baseline survey a week before the other participants, we included a dummy variable for survey timing in analyses.

Data analyses

To test hypotheses and research questions, a series of analyses of variance (ANOVAs) and analyses of moderation were conducted between experimental groups were compared while controlling for manipulated factors and covariates.

Results

Testing for random assignment

To ensure that there were no differences between the experimental groups with respect to demographic characteristics, we conducted one-way ANOVAs with the participants’ condition as the independent variable and age, gender, personal flu vaccine status, and social-economic attitudes as the dependent variables. These analyses did not reveal significant differences among conditions (p > .2).

Manipulation check

We included manipulation checks for message format and message framing. To test the message format manipulation, all participants were asked “Did the video you saw mostly describe … ” with responses including “Alon’s story and his considerations about having a conversation about vaccination” and “People’s considerations generally about having a conversation about vaccination with others close to them.” Most participants correctly identified the message format for the video they had seen (89.6% in the narrative condition and 68% in the non-narrative condition). The observed differences between these groups were significant, χ2 (2, N = 439) = 155.63, p < .001.

To test message framing, we asked all participants, “Did the video you saw mostly describe … ” with response options including “the benefits of having a conversation about vaccination,” “the disadvantages of having a conversation about vaccination,” and “the video referred to personal conversations about sport.” Almost all the participants in the gain-frame message condition (98.7%), as well as the loss-frame message condition (98.6%), recalled that the message described the benefits of having a conversation about vaccinations. Thus, observed group differences were not significant, χ2 (2, N = 439) = .007, p = .99.

As the stimuli material were designed for this study, to show evidence for their validity we measured and compared participants’ responses to ensure that there were no significant differences in message evaluation between message conditions. First, we conducted one-way ANOVAs with message condition as the independent variable and counterarguing and reactance (Dillard & Shen, Citation2005) as the dependent variables. The analyses did not reveal significant group differences for counterarguing, F(3,433) = 1.84, p = .14,or reactance, F(3, 434) = .742, p = .53. Within the narrative messages (gain vs. loss framed) there were no significant differences in mean levels of identification (p = .57), transportation (p = .40), perceived topic relevance (p = .09) or message persuasiveness (p = .35).

Main effects of message framing and message format

To test the direct effects of message framing on vaccine conversation intentions (RQ1) we conducted a one-way ANOVA with message frame (loss vs. gain frame) as the independent variable and intention to discuss the flu vaccine as the dependent variable. There was no significant effect of message frame on discussion intentions (loss: M = 3.63, SD = 1.91; gain: M = 3.81, SD = 1.88), F(1, 436) = 1.02, p = .31. Similarly, a one-way ANOVA testing the main effect of message format (narrative vs. expository) on vaccine intentions (H2a) showed no significant overall differences in vaccine intentions for these groups (narrative: M = 3.80, SD = 1.87; expository: M = 3.64, SD = 1.92), F(1, 436) = .746, p = .39,

We then ran a binary logistic regression model to test the effects of message framing (RQ2) and message format (H2b) on vaccine conversations at follow-up, controlling for survey timing and motivation orientation. The model (x2 = 17.50(4, 204), Nagelkerke R2 = .112, p = .002) showed a significant positive lagged effect of loss-framed messages (vs. gain-framed) on discussion likelihood, (Exp(B) = 2.76, B = 1.01, SE = .31, p = .001). In addition, there was a significant positive effect of motivation orientation on discussion likelihood (Exp(B) = 1.07, B = .06, SE = .03 1, p = .01). Participants exposed to loss-framed messages were 2.7 times more likely to report discussing the flu vaccine with a close referent, compared with participants exposed to gain-framed messages (see ). However, there was no significant effect of message format (narrative) on the likelihood of reported conversation at follow-up (Exp(B) = .84, B = −0.18, SE = .30, p > .05). Thus, H2b is not supported.

Table 3. Logistic regression analysis predicting likelihood of discussion (n = 204).

Message framing, concern for the other, and message format

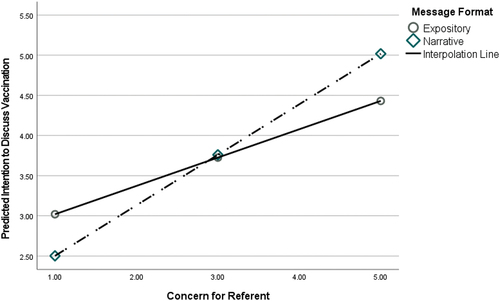

To test the hypothesized interactions between message framing and concern for the referent (H1a), message format and concern for the referent (H3a) and message framing and format (RQ3) on vaccine conversation intentions, we created interaction terms. We entered these as a second block in a multi-stage linear regression model. As a first block, the model includes the conditional effects of message framing (loss vs. gain), message format (narrative vs. expository), and concern for the referent, with survey timing and motivation orientation as covariates, R2 (adj) = .246, F (8, 294) = 13.29,gp < .001. The model did not show a significant interaction effect of message frame and concern for the referent on post-exposure intentions to discuss vaccination with them (B = .14, SE = .11, p > .05). Thus, H1a is not supported. Similarly, there was no significant interaction between message frame and message format (RQ3) on conversation intentions (B = −0.40, SE = .38, p > .05). However, there is a positive interaction between narrative format and concern for the referent on intentions to discuss flu vaccination with a close referent (B = .28, SE = .10, p = .011). Thus, H3a is supported (see ).

Table 4. Linear regression analysis predicting intention to discuss vaccination x message framing and format & message framing x concern (n = 432).

Analysis of the conditional effect of message format showed a positive increase in the effect of exposure to narrative format message on vaccination discussion intention as concern for the referent increased (see ). Participants who viewed narrative format messages reported greater intention to have a conversation with their close referent about flu vaccination if they felt greater concern for their health (B = .59, SE = .27, p = .03), compared with participants who expressed less concern (B = −0.52, SE = .29, p = .07).

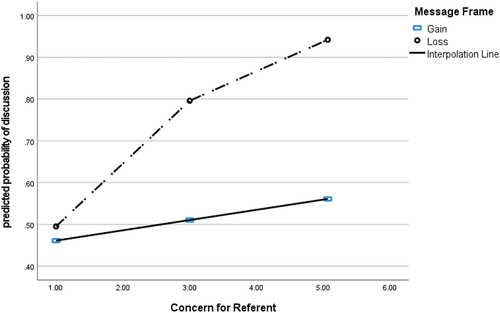

We ran a binary logistic regression model to test the proposed interactions between message framing and concern for the referent (H1b), message format and concern for the referent (H3b), and message format (RQ4) on likelihood of discussing the flu vaccine at follow up, (X2 (5, 204) = 26.71, Nagelkerke R2 = .217, p < .001). The results show that there is no significant interaction between message framing and narrative format (Exp(B) = 1.72, B = .24, SE = .70, p > .05) (RQ4), or interaction between message format and concern for the referent (Exp(B) = 1.22, B = 20, SE = .20, p > .05) on discussion likelihood (H3b). However, results show a significant positive lagged interaction effect of message frame and concern for the referent on the likelihood of discussion (Exp(B) = 1.86 [CI95: 1.18–2.93], B = .62, SE = .23, p = .007), supporting Hypothesis 1b. shows the results of this analysis.

Table 5. Logistic regression analysis predicting likelihood of discussion x message framing and format x message framing x concern (n = 204).

Analysis of the conditional effect of framing showed a positive increase in the effect of exposure to loss-framed messages on the likelihood of discussion as concern for the referent increased (see ). Participants who viewed loss-framed messages were more likely to discuss the topic with that person if they felt greater concern for their health (OR = 2.54, SE = .67, CI95%: 1.22–3.87, p < .001), compared with participants who expressed less concern (OR = .13, SE = .48, CI95%: −0.82–1.08, p > .05). Thus, H1b is supported.

Discussion

Results show that messages promoting the flu vaccine may increase the likelihood that the recipient will discuss the vaccine with a close friend or family member to encourage them to be vaccinated. We test the joint effects of framing and message format and find that message effects depended both on the degree to which the message emphasized the risks of non-vaccination vs. positive consequences of vaccination, but also on the format of the message. The results also show different patterns of message effects for post-exposure intentions, compared with lagged self-reported behavior (i.e., discussion). In addition, we show that effects of loss-framed messages and narrative format messages were dependent on the degree to which the recipient felt concerned for the health of the non-vaccinated referent.

This study shows a complex pattern of goal framing and message format effects on vaccination-related outcomes. On the one hand, loss-framed messages were more effective at influencing reported discussion than gain-framed messages, particularly among those who were more concerned about the health status of the referent. Similarly, we found that concern for the referent moderated the positive effects of exposure to narrative format messages on vaccination discussion intentions (but not reported discussion at follow-up). This pattern suggests that research on message framing and format should consider the direct and moderated effects of these factors in relation to whether the outcome is measured immediately (post-exposure) or at a delay.

One explanation for these results may be that loss-framed messages and narrative format messages promoting vaccination discussions may only motivate audiences to hold these discussions when the risk to the close others’ health is salient to them. Interpersonal relationships are based on a delicate exchange of information, support, and mutual trust, particularly with regard to discussing sensitive topics such as health risks for the other person. For vaccination promotion messages, results suggest group targeting audiences whose family members or close social contacts are in a high-risk group may be advisable. For example, a vaccination promotion campaign might target parents with young children in high-risk groups, pregnant women, or (middle-aged) children of older adults who would be at high risk of flu severity or even death if they were to catch the flu without being vaccinated. Encouraging the audience to discuss flu vaccination with their family members, relatives, parent/s, or close friends could be an effective strategy.

For narrative messages, results show (moderated) effects for post-exposure intention but not for reported discussion at follow-up. It may be that narrative format messages have a stronger immediate persuasive effect (on recipients with greater concern for the referent), and are “stickier” (Berger, Citation2016) than expository messages. However, their influence on vaccine-related outcomes may be transitory. Thus, if the objective of the message is to influence behavior and to generate long-term effects, results suggest that it would be most effective to use a loss-framed message (in any format). The results also illustrate the importance of testing message effects immediately and over time, and of including reported (or measured) behavior as an outcome, not only attitudes and intentions. This approach can help to distinguish between effects that may be related to immediate engagement with message content and influence that can be detected over time once these immediate effects have dissipated.

The study findings also support the notion that the effects of loss-framed messages should depend on risk perceptions (e.g., Gerend & Shepherd, Citation2007; Park, Citation2012; Updegraff et al., Citation2015). Thus, results contribute to research on the risk-framing hypothesis and extend it by showing that audiences may evaluate loss-framed messages according to their risk perceptions, when greater concern for the health risk motivates action, not only for one’s own health but for another persons’ health.

This study contributes to research on interpersonal communication as an outcome of persuasive health communication messages, and a socially consequential behavior for campaigns (Southwell & Yzer, Citation2007, Citation2009). In particular, the study findings can help inform message design to motivate interpersonal conversations to promote flu vaccination. In today’s media environment, conversations can take place through face-to-face interactions, but also via online channels, across a variety of modalities that allow for asynchronous dialogue and the incorporation of elements from other channels. For some campaigns, inducing interpersonal communication is an intentional consequence of the planned campaign effort, such as in facilitating interactions between parents and their adolescent children about drugs (Hornik & Yanovitzky, Citation2003), or prompting family discussion about organ donation (Afifi et al., Citation2006). Research on interpersonal conversation as a campaign outcome suggests that the most effective approach is to boost the audience’s perceived efficacy to hold the conversation, empower them with information, and explain the benefits of the conversation for the target of the appeal (Southwell & Yzer, Citation2007).

From a theoretical standpoint this study further reinforces the need to consider health promotion efforts beyond those at the individual-level models of behavior change (Hornik & Yanovitzky, Citation2003). Individual-level factors and vaccination promotion efforts have been investigated at length in the literature, including in a recent review of COVID-related vaccination messages (Xia & Nan, Citation2023). This literature, and other studies (O’Keefe & Hoeken, Citation2021; O’Keefe & Nan, Citation2012) find little evidence that message design features such as message framing make a significant difference in persuading individual people to be vaccinated. Thus, it is important to consider persuasive strategies to promote vaccination beyond individual-level persuasion. More research is needed to understand how interpersonal influence can be targeted as a campaign outcome to influence vaccine-related uptake through social influence.

Strengths and limitations

There are several factors related to the study’s research design that strengthen the validity of its findings. The first is the use of carefully designed video messages, rather than print, that control for a range of possible confounding elements. We use video messages as prior research suggests that, compared to text-based messages, messages delivered through more engaging channels such as videos may be more effective at motivating vaccination-related outcomes. A prior-meta-analysis on the effects of (health-related) narratives has also found that narratives delivered via audio or video had a significantly stronger effect on persuasion, compared to narratives in print form (Shen et al., Citation2015). All messages were scripted to be of similar duration and featured the same protagonist in the same setting. We chose the same actor (male) to control for source factors that could influence the observed effects but note that it is possible that the actor’s gender influenced the observed effects. To account for this, future research should feature protagonists of different genders and ages. In addition, the study tests hypotheses among a nonstudent population and assesses these effects immediately and at a one-month delay.

Study limitations include that the message framing manipulation check did not show significant differences between framing conditions (but did show significant differences for the message format manipulation|). This result may be related to the message content (see Appendix), which included information about flu vaccine efficacy and a call to action, alongside the framing manipulation, which either emphasized the benefits of vaccination or the risks of not being vaccinated. While we manipulated goal framing using methods from prior research (Gerend & Shepherd, Citation2007), participants may have felt that the overall message focus was on the health benefits of vaccination.

In addition, the messages we created were comparatively longer than typical public service announcements. We programmed the survey to ensure that participants could not skip through the video until it concluded playing, but we cannot prove that they were actively engaged throughout. Future research should pretest stimuli and a manipulation check for framing ensuring the messages are engaging. We also recommend including a measure of message recall to help participants recall the message they viewed a month ago, to help rule out memory-related errors.

We asked participants to report whether they had discussed the flu vaccine with a close family member or friend in the last month, but we did not directly measure this behavior. This time frame may not have been long enough to enable some participants to follow through on the call to action. Finally, we note significant attrition between the baseline and follow-up surveys. However, comparing the sample demographics for both waves shows that the respondents were very similar (see ), alleviating concerns about sample bias due to nonrandom attrition.

Conclusion

The study findings reinforce the need to consider interpersonal conversation as an important strategic outcome of health communication. However, even when campaigns stimulate conversation, the resulting discussion may not necessarily coincide with the campaign goals, especially if the target audience disagrees with the message claims (Southwell & Yzer, Citation2007). Self-reported interpersonal communication is an adequate and convenient measure of behavior (Southwell, Citation2005), but is vulnerable to bias due to social desirability and fallible recall. Stimulating interpersonal conversation may also result in effects that are contradictory to campaign goals. For example, when discussing the flu vaccine, the unvaccinated referent may raise arguments against the vaccine or express a lack of normative support for vaccination that may adversely influence the message recipients’ own vaccination beliefs and intentions (van den Putte et al., Citation2011). Future research should consider the valence and nature of the reported discussion that was motivated by message exposure and its impact on both parties to account for this possibility. As the study was conducted in Israel, the hypotheses we tested should be examined among other populations and contexts. Given the importance of social media as a health communication channel, we would also encourage researchers to use social media channels to encourage interpersonal discussions aimed at promoting flu vaccination.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. We include motivation orientation as a covariate, but do not test it as a moderator as prior research did not show support for the interaction between message framing and motivational orientation for flu vaccination intentions.

References

- Abhyankar, P., O’Connor, D. B., & Lawton, R. (2007). The role of message framing in promoting MMR vaccination: Evidence of a loss-frame advantage. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 13(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548500701235732

- Afifi, W. A., Morgan, S. E., Stephenson, M. T., Morse, C., Harrison, T., Reichert, T., & Long, S. D. (2006). Examining the decision to talk with family about organ donation: Applying the theory of motivated information management. Communication Monographs, 73(2), 188–215. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637750600690700

- Baesler, E. J., & Burgoon, J. K. (1994). The temporal effects of story and statistical evidence on belief change. Communication Research, 21(5), 582–602. https://doi.org/10.1177/009365094021005002

- Bandura, A. (2002). Social cognitive theory in cultural context. Applied Psychology, 51(2), 269–290. https://doi.org/10.1111/1464-0597.00092

- Berger, J. (2016). Contagious: Why things catch on. Simon & Schuster.

- Borah, P., & Hwang, J. (2021). Trust in doctors, positive attitudes, and vaccination behavior: The role of doctor–patient communication in H1N1 vaccination. Health Communication, 37(11), 1423–1431. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2021.1895426

- Bradshaw, A. S., Shelton, S. S., Wollney, E., Treise, D., & Auguste, K. (2020). Pro-vaxxers get out: Anti-vaccination advocates influence undecided first-time, pregnant, and new mothers on Facebook. Health Communication, 36(6), 693–702. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2020.1712037

- Brashers, D. E., Goldsmith, D. J., & Hsieh, E. (2002). Information seeking and avoiding in health contexts. Human Communication Research, 28(2), 258–271. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1468-2958.2002.TB00807.X

- Burnkrant, R. E., & Unnava, H. R. (1989). Self-referencing: A strategy for increasing processing of message content. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 15(4), 628–638. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167289154015

- Cappella, J. N. (1987). Interpersonal communication: Definitions and fundamental questions. In C. R. Berger & S. H. Chaffee (Eds.), Handbook of communication science (pp. 184–238). Sage.

- Carver, C. S., & White, T. L. (1994). Behavioral inhibition, behavioral activation, and affective responses to impending reward and punishment: The BIS/BAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(2), 319–333. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.67.2.319

- CDC seasonal flu vaccine effectiveness studies. (2022, August 3). Center for disease control and prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/vaccines-work/effectiveness-studies.htm

- Cline, R. J. W. (2003). Everyday interpersonal communication and health. In T. L. Thompson, A. M. Dorsey, K. I. Miller & R. Parrott (Eds.), Handbook of health communication (pp. 285–313). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

- Dillard, J. P., & Shen, L. (2005). On the nature of reactance and its role in persuasive health communication. Communication Monographs, 72(2), 144–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637750500111815

- Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (2011). Predicting and changing behavior: The reasoned action approach. Taylor & Francis. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203838020

- Gallagher, K. M., & Updegraff, J. A. (2012). Health message framing effects on attitudes, intentions, and behavior: A meta-analytic review. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 43(1), 101–116. https://doi.org/10.1007/S12160-011-9308-7

- Ganczak, M., Gil, K., Korzeń, M., & Bażydło, M. (2017). Coverage and influencing determinants of influenza vaccination in elderly patients in a country with a poor vaccination implementation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(6), 665. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14060665

- Gerend, M. A., & Shepherd, J. E. (2007). Using message framing to promote acceptance of the human papillomavirus vaccine. Health Psychology, 26(6), 745–752. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.26.6.745

- Ghebrehewet, S., MacPherson, P., & Ho, A. (2016). Influenza. BMJ, 355, i6258. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i6258

- Green, M. C. (2006). Narratives and cancer communication. Journal of Communication, 56(suppl 1), S163–S183. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1460-2466.2006.00288.X

- Green, M. C., & Brock, T. C. (2000). The role of transportation in the persuasiveness of public narratives. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(5), 701–721. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.79.5.701

- Hafstad, A., & Aarø, L. E. (1997). Activating personal influence through provocative appeals: Evaluation of a mass media-based antismoking campaign targeting adolescents. Health Communication, 9(3), 253–272. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327027hc0903_4

- Heiss, S. N., Carmack, H. J., & Chadwick, A. E. (2015). Effects of interpersonal communication, knowledge, and attitudes on pertussis vaccination in Vermont. Journal of Communication in Healthcare, 8(3), 207–219. https://doi.org/10.1179/1753807615Y.0000000012

- Hornik, R., & Yanovitzky, I. (2003). Using theory to design evaluations of communication campaigns: The case of the National Youth Anti-Drug Media Campaign. Communication Theory, 13(2), 204–224. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2003.tb00289.x

- Israel Center for Disease Control. (2020). Summary report - the 2019/20 influenza season. https://www.health.gov.il/PublicationsFiles/Flu2019_2020.pdf

- Israeli Ministry of Health. (2022). Flu – FAQ. https://www.health.gov.il/English/Topics/Vaccination/flu/Pages/flu-faq.aspx

- Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47(2), 263–292. https://doi.org/10.2307/1914185

- Katz, E., & Lazarsfeld, P. F. (1966). Personal influence, the part played by people in the flow of mass communications. Transaction Publishers.

- Kiene, S. M., Barta, W. D., Zelenski, J. M., & Cothran, D. L. (2005). Why are you bringing up condoms now? The effect of message content on framing effects of condom use messages. Health Psychology, 24(3), 321–326. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.24.3.321

- Kim, S., Pjesivac, I., & Jin, Y. (2019). Effects of message framing on influenza vaccination: Understanding the role of risk disclosure, perceived vaccine efficacy, and felt ambivalence. Health Communication, 34(1), 21–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2017.1384353

- Kreuter, M. W., Green, M. C., Cappella, J. N., Slater, M. D., Wise, M. E., Storey, D., Clark, E. M., O’Keefe, D. J., Erwin, D. O., Holmes, K., Hinyard, L. J., Houston, T., & Woolley, S. (2007). Narrative communication in cancer prevention and control: A framework to guide research and application. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 33(3), 221–235. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02879904

- Lee, S. K., Sun, J., Jang, S., & Connelly, S. (2022). Misinformation of COVID-19 vaccines and vaccine hesitancy. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-17430-6

- Levin, I. P., Schneider, S. L., & Gaeth, G. J. (1998). All frames are not created equal: A typology and critical analysis of framing effects. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 76(2), 149–188. https://doi.org/10.1006/obhd.1998.2804

- Liu, S., Guo, L., Mays, K., Derry, M. B., & Wijaya, T. (2019). Detecting frames in news headlines and its application to analyzing news framing trends surrounding U.S. gun violence. In Proceedings of the 23rd Conference on Computational Natural Language Learning (CoNLL) (pp. 504–514). https://derrywijaya.github.io/GVFC.html

- Maheswaran, D., & Meyers-Levy, J. (2018). The influence of message framing and issue involvement. Journal of Marketing Research, 27(3), 361–367. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224379002700310

- Mann, T., Sherman, D., & Updegraff, J. (2004). Dispositional motivations and message framing: A test of the congruency hypothesis in college students. Health Psychology, 23(3), 330–334. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.23.3.330

- McCaul, K. D., Johnson, R. J., & Rothman, A. J. (2002). The effects of framing and action instructions on whether older adults obtain flu shots. Health Psychology, 21(6), 624–628. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.21.6.624

- Millar, M. G., & Millar, K. U. (2000). Promoting safe driving behaviors: The influence of message framing and issue involvement. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 30(4), 853–866. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1559-1816.2000.TB02827.X

- Nan, X. (2012). Communicating to young adults about HPV vaccination: Consideration of message framing, motivation, and gender. Health Communication, 27(1), 10–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2011.567447

- Nan, X., Zhao, X., Yang, B., & Iles, I. (2015). Effectiveness of cigarette warning labels: Examining the impact of graphics, message framing, and temporal framing. Health Communication, 30(1), 81–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2013.841531

- O’Keefe, D. J. (2021). Persuasive message pretesting using non-behavioral outcomes: Differences in attitudinal and intention effects as diagnostic of differences in behavioral effects. Journal of Communication, 71(4), 623–645. https://doi.org/10.1093/JOC/JQAB017

- O’Keefe, D. J., & Hoeken, H. (2021). Message design choices don’t make much difference to persuasiveness and can’t be counted on—not even when moderating conditions are specified. Frontiers in Psychology, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.664160

- O’Keefe, D. J., & Jensen, J. D. (2006). The advantages of compliance or the disadvantages of noncompliance? A meta-analytic review of the relative persuasive effectiveness of gain-framed and loss-framed messages. Annals of the International Communication Association, 30(1), 1–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/23808985.2006.11679054

- O’Keefe, D. J., & Jensen, J. D. (2007). The relative persuasiveness of gain-framed and loss-framed messages for encouraging disease prevention behaviors: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Health Communication, 12(7), 623–644. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730701615198

- O’Keefe, D. J., & Jensen, J. D. (2009). The relative persuasiveness of gain-framed and loss-framed messages for encouraging disease detection behaviors: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Communication, 59(2), 296–316. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1460-2466.2009.01417.X

- O’Keefe, D. J., & Nan, X. (2012). The relative persuasiveness of gain- and loss-framed messages for promoting vaccination: A meta-analytic review. Health Communication, 27(8), 776–783. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2011.640974

- OECD. (2023). Influenza vaccination rates – OECD data (July, 2023). https://data.oecd.org/healthcare/influenza-vaccination-rates.htm

- Park, S. Y. (2012). The effects of message framing and risk perceptions for HPV vaccine campaigns: Focus on the role of regulatory fit. Health Marketing Quarterly, 29(4), 283–302. https://doi.org/10.1080/07359683.2012.732847

- Peng, L., Guo, Y., & Hu, D. (2021). Information framing effect on public’s intention to receive the COVID-19 vaccination in China. Vaccines, 9(9), 995. https://doi.org/10.3390/VACCINES9090995

- Penţa, M. A., & Băban, A. (2017). Message framing in vaccine communication: A systematic review of published literature. Health Communication, 33(3), 299–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2016.1266574

- Rahman, M. M., Chisty, M. A., Alam, M. A., Sakib, M. S., Quader, M. A., Shobuj, I. A., Halim, M. A., Rahman, F., & Zhou, J. (2022). Knowledge, attitude, and hesitancy towards COVID-19 vaccine among university students of Bangladesh. PLoS ONE, 17(6), e0270684. https://doi.org/10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0270684

- Rogers, E. M. (2003). Diffusion of innovations (5th ed.). Simon & Schuster.

- Rothman, A. J., Martino, S. C., Bedell, B. T., Detweiler, J. B., & Salovey, P. (1999). The systematic influence of gain-and loss-framed messages on interest in and use of different types of health behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 25(11), 1355–1369. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167299259003

- Rothman, A. J., & Salovey, P. (1997). Shaping perceptions to motivate healthy behavior: The role of message framing. Psychological Bulletin, 121(1), 3–19. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.121.1.3

- Shen, F., Sheer, V. C., & Li, R. (2015). Impact of narratives on persuasion in health communication: A meta-analysis. Journal of Advertising, 44(2), 105–113. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2015.1018467

- Shen, L., & Dillard, J. P. (2007). The influence of behavioral inhibition/approach systems and message framing on the processing of persuasive health messages. Communication Research, 34(4), 433–467. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650207302787

- Southwell, B. G. (2005). Between messages and people: A multilevel model of memory for television content. Communication Research, 32(1), 112–140. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650204271401

- Southwell, B. G., & Yzer, M. C. (2007). The roles of interpersonal communication in mass media campaigns. Annals of the International Communication Association, 31(1), 420–462. https://doi.org/10.1080/23808985.2007.11679072

- Southwell, B. G., & Yzer, M. C. (2009). When (and why) interpersonal talk matters for campaigns. Communication Theory, 19(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2008.01329.x

- Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1981). The framing of decisions and the psychology of choice. Science, 211(4481), 453–458. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.7455683

- Uchino, B. N. (2006). Social support and health: A review of physiological processes potentially underlying links to disease outcomes. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 29(4), 377–387. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-006-9056-5

- Updegraff, J. A., Brick, C., Emanuel, A. S., Mintzer, R. E., & Sherman, D. K. (2015). Message framing for health: Moderation by perceived susceptibility and motivational orientation in a diverse sample of Americans. Health Psychology, 34(1), 20. https://doi.org/10.1037/HEA0000101

- van den Putte, B., Yzer, M., Southwell, B. M., de Bruijn, G.-J., & Willemsen, M. C. (2011). Interpersonal communication as an indirect pathway for the effect of antismoking media content on smoking cessation. Journal of Health Communication, 16(5), 470–485. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2010.546487

- van ’t Riet, J., Cox, A. D., Cox, D., Zimet, G. D., de Bruijn, G. J., van den Putte, B., de Vries, H., Werrij, M. Q., & Ruiter, R. A. C. (2014). Does perceived risk influence the effects of message framing? A new investigation of a widely held notion. Psychology & Health, 29(8), 933. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2014.896916

- Wang, X. (2022). Attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccines and vaccine uptake intent in China: The role of collectivism, interpersonal communication, and the use of news and information websites. Current Research in Ecological and Social Psychology, 3, 100065. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CRESP.2022.100065

- World Health Organization. (2020). Ten Threats to global health in 2019. https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019

- World Health Organization. (2021, August 30). Vaccines and immunization: What is vaccination? https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/vaccines-and-immunization-what-is-vaccination

- Xia, S., & Nan, X. (2023). Motivating COVID-19 vaccination through persuasive communication: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Health Communication, 1–24. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2023.2218145

- Xu, Y., Margolin, D., & Niederdeppe, J. (2020). Testing strategies to increase source credibility through strategic message design in the context of vaccination and vaccine hesitancy. Health Communication, 36(11), 1354–1367. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2020.1751400

- Ye, W., Li, Q., & Yu, S. (2021). Persuasive effects of message framing and narrative format on promoting COVID-19 vaccination: A study on Chinese college students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(18), 9485. https://doi.org/10.3390/IJERPH18189485

- Yin, H., You, Q., Wu, J., & Jin, L. (2022). Factors influencing the knowledge gap regarding influenza and influenza vaccination in the context of COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional survey in China. Vaccines, 10(6), 957. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10060957

- Yu, N., Ahern, L. A., Connolly-Ahern, C., & Shen, F. (2010). Communicating the risks of fetal alcohol spectrum disorder: Effects of message framing and exemplification. Health Communication, 25(8), 692–699. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2010.521910

Appendix

Video script - Narrative Format Messages (with Framing Manipulation)

Hi, my name is Alon*, I am a father of two, and live in Haifa. I would like to talk to you about the flu vaccine. Every year, hospitals are filled with patients suffering with the flu. Influenza (the flu) is a disease that can even be life-threatening for people in risk groups such as adults and small children. Israel’s health insurance clinics offer people the option to get vaccinated against the flu every year. The vaccine is safe to use and significantly reduces the chance of becoming infected, infecting others, and developing severe symptoms if infected.

I know that some people, including those in risk groups, choose not to get the flu vaccination. Yossi, my father is one of these people. For years he has chosen not to get vaccinated. His choice causes me a lot of concern, out of fear that he is at risk of catching the flu. I wanted to express my concern to him and ask him to reconsider having the vaccine. But I was worried – I don’t want to hurt him, insult him or to harm our relationship because of this. But still, the concern for my father’s life outweighed my concerns about the possible damage to our relationship.

I decided to talk to him. Before our conversation, I thought it would be best if I prepared, and I looked for reliable information about the flu vaccine. We met on a Friday afternoon. I shared with him that I really love him and I care about him, and I want to talk to him about the vaccine. At the beginning of the conversation, I asked him to share with me his reasons for hesitating to be vaccinated. My father explained to me that he is not convinced that the flu vaccine is effective, he is afraid of the side effects, and he believes that the flu is not a serious disease that warrants a vaccine. I listened to him attentively, I understood how he felt and could feel that his concerns were genuine.

Then I presented him with the information I had found about the effectiveness of the vaccine – that the vaccine was approved by the FDA and by the World Health Organization and that there are currently over a billion people in the world who have been vaccinated, with relatively few cases of side effects, even compared to other vaccines.

Our conversation wasn’t easy, but we reached a mutual understanding. My father said he would think about things. After two weeks he called me and told me he had thought about it. Apparently, following our conversation, he changed his attitude and made an appointment to have a flu vaccination. I felt tremendous satisfaction in helping my father protect his health.

You may also have a close friend or family member in your life, like my father, who is hesitant to get vaccinated against the flu. If you are also unsure about how to approach them and have a conversation with them to try to convince them to get vaccinated you should know – its not easy, but it’s totally worth your investment of time and effort. If the conversation is done correctly and in a good spirit, both of you can benefit, while maintaining the relationship.

“Don’t hesitate – have a conversation about the flu vaccine today.”

*not his real name

Video script - Expository Format Messages (with Framing Manipulation)

Hi, my name is Alon, I am a father of two, and live in Haifa. I would like to talk to you about the flu vaccine. Every year, hospitals are filled with patients suffering with the flu. Influenza (the flu) is a disease that can even be life-threatening for people in risk groups such as adults and small children. Israel’s health insurance clinics offer people the option to get vaccinated against the flu every year. The vaccine is safe to use and significantly reduces the chance of becoming infected, infecting others, and developing severe symptoms if infected. Some of the public, including those in risk groups, choose not to get vaccinated against the flu. It is possible that some of these people in risk groups, such as older people over 70 and/or with underlying diseases, are your friends or relatives.

Maybe their choice causes you a lot of concern, for fear that they are at risk of catching the flu. You may even want to express your concern to them and ask them in conversation to reconsider having the vaccine. You may also be afraid to have such a conversation because you don’t want to damage your relationship because of it. But still, concern for their lives outweighs concerns about the possible damage to the relationship.

In case you decide to have such a conversation with them. If you do, it is best to prepare by looking for reliable information about the flu vaccine before you initiate the conversation. At the beginning of the conversation, you should share your concerns with them, and explain that you are having this discussion with them out of your care and love for them. You can ask them to share with you the reasons they are hesitant to be vaccinated. It may be that they will raise arguments such as the ineffectiveness of the vaccine, its side effects and the fact that the flu is not a serious disease that warrants vaccination.

In such cases, it is possible to provide answers to worries and concerns through the information you obtained before the conversation about the effectiveness of the vaccine – that the vaccine was approved by the FDA and by the World Health Organization and that there are currently over a billion people in the world who have been vaccinated, with relatively few cases of side effects, even compared to other vaccines.

Such conversations may not be easy, but they can be mutually rewarding. It is possible that, as a result of having this conversation, your friend or family member might even change their attitude and decide to get vaccinated against the flu. Conversations like this can make you feel tremendous satisfaction that you helped a loved one protect their health.

You may also have a close friend or family member in your life who is hesitant to get vaccinated against the flu. If you are also unsure about how to approach them and have a conversation with them to try to convince them to get vaccinated you should know – its not easy, but it’s totally worth your investment of time and effort. If the conversation is done correctly and in a good spirit, both of you can benefit, while maintaining the relationship.

“Don’t hesitate – have a conversation about the flu vaccine ss

Screenshot from the video (with Hebrew subtitles)

The image features a man aged around 40 with glasses, wearing a gray sweatshirt and sitting on a couch.