?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

During the COVID-19 crisis, many social media influencers (SMIs) discussed the pandemic on their channels and showcased their behavior in dealing with the virus. Drawing on the two-step flow of communication and social learning theory, we investigated the attitudinal and behavioral consequences of SMIs’ COVID-19-related communication in a two-wave panel survey among emerging adults aged 16–21 years (NT1 = 978, NT2 = 415). Our results contribute to the health communication literature by discovering that institutional mistrust determines whether young people resort to SMIs as an information source for COVID-19-related information. Those with higher mistrust in established media organizations and the government were more likely to consult SMIs for COVID-19-related information and to consider them as role models when exposed to relevant content. Moreover, consulting SMIs who promote noncompliance as a COVID-19 information source was over time related to lower vaccination intentions.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, one in ten people worldwide consulted popular personalities on social media when looking for information about the virus (Volkmer, Citation2021). This observation resonates with the increasing importance of what are called social media influencers (SMIs) as news sources and the simultaneous disregard for legacy media outlets among younger generations (Newman et al., Citation2021, Citation2023). SMIs are commonly defined as ordinary people who gained fame through self-branding on social media (Khamis et al., Citation2017); they cover various topics, like lifestyle or gaming, but they also often discuss sociopolitical issues (Allgaier, Citation2020; Dekoninck & Schmuck, Citation2022; Harff & Schmuck, Citation2023; Riedl et al., Citation2021; Suuronen et al., Citation2021). During the pandemic, many SMIs supported COVID-19 measures and promoted vaccination campaigns (Volkmer, Citation2021), while others spread misinformation or openly defied official COVID-19 measures (Abidin et al., Citation2021; Fetters Maloy & De Vynck, Citation2021). Young people, who are SMIs’ main target group (Djafarova & Matson, Citation2021), often consider SMIs as role models (Zimmermann et al., Citation2022), which puts them at risk of emulating the potentially detrimental behavior of SMIs (Sinclair & Agerström, Citation2023).

In this research area, crucial gaps remain. First, researchers have paid scant attention to the importance of SMIs as an information source on the topic of COVID-19 and as role models on how to deal with the pandemic. Younger age groups felt marginalized by mainstream media during the pandemic (Newman et al., Citation2021); consequently, SMIs, with whom this age group closely identify, emerged as important addressors of their interests, especially given young people’s inclination to search for health information online (Lou & Kim, Citation2019). Second, it remains virtually unexplored who was most likely to consult SMIs on the polarized topic of COVID-19 during the pandemic. Youth who doubt official institutions like the government, the pharmaceutical industry, or legacy media may be especially prone to turn to SMIs for information on COVID-19, because the latter may offer anti-mainstream perspectives on the topic (Lewis, Citation2020). Third, we lack research on SMIs’ impact on young people’s COVID-19-related attitudes and vaccination intentions, especially when those SMIs demonstrate noncompliant behavior, such as overtly opposing governmental restrictions like lockdowns or the obligation to wear face masks (Abidin et al., Citation2021).

We fill these major research gaps by investigating, for the first time, how SMIs’ communication about COVID-19 is related to their function as an information source and a role model, as well as how these affect risk perceptions and vaccination intentions among youth. While using SMIs as information sources can be theoretically explained through information-seeking and information distribution by opinion leaders, emulating the behavior of SMIs is rooted in processes of role-modeling. Thus, we draw from two theoretical approaches: we use the two-step flow of communication (Katz & Lazarsfeld, Citation2006) to conceptualize SMIs as information sources, and we use social learning theory (Bandura, Citation1971) to theorize SMIs as behavioral role models. We argue that these two related but distinct processes explain the potential impact SMIs may have on young people’s COVID-19 risk perceptions and vaccination intentions. Distinguishing between these two conceptual processes also enables us to determine whether SMIs are more impactful as role models or as information sources. In addition, we shed light on important novel boundary conditions, such as institutional mistrust and SMIs’ (non)compliance with COVID-19 measures.

To this end, we conducted a longitudinal two-wave panel survey among youth aged 16–21 years (NT1 = 978; NT2 = 415) in Germany, taking measurements right before and right after the peak of the first COVID-19 vaccination campaign in 2021. Our study provides valuable insights into how SMIs’ content influences risk perceptions and vaccination intentions among a diverse sample of national youth. This enables us to study important susceptibility factors, like institutional mistrust, and offers practical insights for stakeholders, such as governments, NGOs, and media literacy educators.

SMIs as opinion leaders and role models

During crises like the COVID-19 pandemic, high levels of uncertainty and fear drive people to seek information for guidance (Abidin et al., Citation2021). This leads to an increased use of traditional media outlets and more information-oriented use of social media (Van Aelst et al., Citation2021; Westlund & Ghersetti, Citation2015). At present, SMIs have emerged as one of the primary news sources for young people, surpassing politicians, journalists, and news outlets in terms of relevance (Newman et al., Citation2021, Citation2023). Even though SMIs may not be experts on the topics they address (Reinikainen et al., Citation2020), youth appreciate their opinion-oriented communication on contemporary sociopolitical topics (Marchi, Citation2012; Zimmermann et al., Citation2022). This resonates with the two-step flow of communication theory (Katz & Lazarsfeld, Citation2006), which postulates that many individuals receive their information not directly from the media but rather indirectly via influential nodes in their networks, called “opinion leaders”.

Marked by the promotion of certain values, a larger network, and greater thematic interest or knowledge, opinion leaders relay information from the media to “opinion followers” (Schäfer & Taddicken, Citation2015). These followers, who may not actively seek out information themselves, become responsive not only to the news but also to the advice of the opinion leaders on various topics (Harff & Schmuck, Citation2023). In the mass-mediated context, opinion leaders who are not part of people’s immediate social surroundings exert influence via parasocial relationships—i.e., one-sided intimate bonds that recipients experience with media personalities (Stehr et al., Citation2015). SMIs excel in exploiting the affordances of social media to forge close relationships with their fans (Dekoninck et al., Citation2023; Schmuck, Citation2021), and their authentic self-presentation makes them more relatable than traditional celebrities (Schouten et al., Citation2020). They can also act as information sources in domains such as beauty, fashion, or nutrition (Feng et al., Citation2021; Hudders et al., Citation2021). As such, SMIs may generate considerable impact when they decide to use their popularity to communicate messages related to more serious topics, like politics or public health (Leader et al., Citation2021).

Existing descriptive research suggests that SMIs are also considered important role models by young people (Zimmermann et al., Citation2022): their similarity to their audience members (Lou & Kim, Citation2019) – and their concurrent celebrity status – may lead their fans to emulate their behavior (Gleason et al., Citation2017; Le & Hancer, Citation2021; Schouten et al., Citation2020). In addition, SMIs’ behavior makes imitation by young audiences especially likely, due to the actionable advice they give (Abidin, Citation2021). Overall, they may be in a favorable position to guide young followers in times of uncertainty and crisis (Kaiser et al., Citation2021). Given the enduring identity formation that occurs in late adolescence and emerging adulthood (Kroger et al., Citation2010), attitudes toward politics and health remain malleable in this period, providing fertile ground for SMIs to shape their audiences’ opinions and behavior on sociopolitical matters.

Institutional mistrust as a driving force

Not all individuals are equally likely to turn to SMIs as an information source and/or a role model. Instead, certain predispositions may determine this propensity (Valkenburg & Peter, Citation2013). For instance, prior trust in media outlets determined one’s choice of news sources during the pandemic (Van Aelst et al., Citation2021).

Given that primary reliance on social media for news is associated with lower trust in mainstream media (e.g., Castro et al., Citation2022; Kalogeropoulos et al., Citation2019), it is plausible that SMIs may be considered a useful information source by young adults who are already suspicious of traditional information outlets. This notion is in line with the literature, which has demonstrated that skepticism toward mainstream media predisposes people to use alternative news sources (e.g., Klawier et al., Citation2023); accordingly, people with low levels of media trust have been found to turn to alternative news platforms, political activists, SMIs, and celebrities (Newman et al., Citation2021).

Although many SMIs also encourage their followers to keep up with traditional news (Abidin, Citation2021), interview data with SMIs suggest that they are less likely to reproduce health information from mainstream organizations, rather relying on unverified sources and their personal experiences (Leader et al., Citation2021). In particular, a subgroup of alternative-health SMIs has been identified among lifestyle and wellness SMIs; such SMIs distrust institutional authorities (including the government and the pharmaceutical industry) and are likely to disseminate vaccine-related misinformation and conspiracy theories (Baker, Citation2022). In their analysis of anti-vaccine content on Facebook and Twitter, the Center for Countering Digital Hate (CCDF, Citation2021), a US nonprofit organization, revealed that 65% of anti-vaccine misinformation was linked to the social media accounts of alternative-health SMIs (Chinn et al., Citation2023). Far-right SMIs in particular instrumentalized COVID-19 for harsh criticism of elites and targeted population segments who lacked trust in institutions (Rothut et al., Citation2023).

In this context, the risk information seeking and processing (RISP) model (Griffin et al., Citation1999) provides theoretical grounds for the assumption that followers who already doubt official information about COVID-19 and mistrust established institutions may see SMIs and their COVID-19 content as a viable news alternative. More specifically, the concept of information insufficiency has been applied to the COVID-19 pandemic to describe how individuals are motivated to fill the gap between what they currently know and what they desire to know (Zhou & Roberto, Citation2022). Therefore, youth who perceive the information they receive about COVID-19 from mainstream channels as insufficient or one-sided may be more likely to perceive information from alternative sources like SMIs as more gratifying upon exposure to it. The close cooperation between legacy media and governments in many countries at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic may have motivated young people who did not fully trust legacy media or political institutions to consider SMIs’ more opinion-oriented coverage of COVID-19 to be more suitable for them (Abidin, Citation2021; Marchi, Citation2012; Zimmermann et al., Citation2022). Thus, we hypothesize that institutional mistrust determines whether young people consider SMIs a useful information source and a role model for dealing with COVID-19 upon exposure to their COVID-19-related content, which we define as all mentions of the COVID-19 disease and COVID-19 vaccinations:

H1:

Exposure to COVID-19 content by SMIs increases the subjective importance of SMIs as a source of information about COVID-19 among those with higher levels of institutional mistrust.

H2:

Exposure to COVID-19 content by SMIs increases perceptions of SMIs as a role model for dealing with COVID-19 among those with higher levels of institutional mistrust.

SMIs as a persuasive information source

According to the RISP model, the process of information seeking can shape individuals’ behavioral intentions and actual behavior (Griffin et al., Citation1999). Applying the model to the COVID-19-pandemic in their longitudinal study, Zhou and Roberto (Citation2022) found support for the impact of information-seeking on vaccination intentions and actual vaccination behavior. However, little is known about the effects of using SMIs as an information source on individuals’ COVID-19-related attitudes and behavior intentions. With regard to the use of social media in general as an information source about COVID-19, extant findings suggest an overall strong negative relationship between perceiving social media as an information source about COVID-19 and several COVID-19 health-protective behaviors, such as social distancing (Allington et al., Citation2021). A potential explanation for the relationship between more frequent social media use and less compliance with health-protective behaviors may be the stronger presence of conspiracy theories on these platforms: Theocharis et al. (Citation2023) found that the use of most social media (with the exception of Twitter) was related to greater belief in COVID-19 conspiracy theories. Additionally, user-generated YouTube videos about vaccines have been found to be overtly negative in tone and to contain conspiracy beliefs or accusations of infringement on civil liberty (Briones et al., Citation2012).

Although we lack research on the consequences of perceiving SMIs as an information source about COVID-19, it can be expected that the persuasive impact of information distributed on social media is even stronger when opinion leaders are the ones communicating it (Weeks & Gil de Zúñiga, Citation2021). Thus, we expect that considering SMIs a useful information source facilitates a corresponding attitude and behavior change (Stehr et al., Citation2015). Nevertheless, the direction of this influence may be highly contingent on the type of content SMIs provide, as it can vary from agreeing with that of official health institutions to overtly contradicting it (Abidin et al., Citation2021; Leader et al., Citation2021). The few existing studies focusing on SMIs during the COVID-19 pandemic suggest that their communication was highly diverse (Abidin, Citation2021; Baker, Citation2022; Pöyry et al., Citation2022). For instance, some SMIs encouraged young people to keep up with the news about the recommended measures and regulations, and they shared announcements from official and verified sources like the WHO (Abidin, Citation2021), while others distributed false claims and conspiracy theories (Abidin et al., Citation2021; Baker, Citation2022; CCDF, Citation2021).

Therefore, the impact of using SMIs as an information source about COVID-19 may depend on the type of content that SMIs are providing. Drawing on the two-step flow of communication theory, we can assume that perceiving an SMI as an opinion leader provides the basis for attitude and behavior change aligning with that SMI’s advice (Katz & Lazarsfeld, Citation2006; Stehr et al., Citation2015). Hence, if SMIs’ content is consistent with officially communicated information by legacy media or politicians, then followers will also be more likely to perceive COVID-19 as a threat—i.e., have higher risk perceptions. Similarly, information on social media has been found to impact vaccine awareness and attitudes (Ortiz et al., Citation2019). However, if SMIs communicate opinions that contradict the official COVID-19 measures, such as ignoring lockdown regulations (Abidin et al., Citation2021), their audience may accordingly adapt such attitudes over time. In other words, the more followers perceive SMIs as an important source of information about COVID-19, the more likely they are to trust their opinion as a basis for subsequent attitude formation and behavior. The direction of this association will most likely depend on SMIs’ demonstrated (non)compliance with official COVID-19-regulations. Thus, we hypothesize:

H3:

The subjective importance of SMIs as an information source about COVID-19 determines young people’s risk perceptions as a function of SMIs’ demonstrated compliance with COVID-19 measures.

H4:

The subjective importance of SMIs as an information source about COVID-19 determines young people’s vaccination intentions as a function of SMIs’ demonstrated compliance with COVID-19 measures.

SMIs’ role model function, from a social learning perspective

SMIs do not only inform their followers and make suggestions as to how they should behave; they also share snapshots of their own experiences in both the private realm (e.g., practicing social distance) and the public realm (e.g., participating in a protest) (Berryman & Kavka, Citation2017; Pöyry et al., Citation2022), which may prompt followers to imitate them. This postulation aligns with social learning theory, which states that people tend to adopt the behaviors of their role models (Bandura, Citation1971) – a rationale previously applied to explain SMIs’ persuasive influence around brand support (Cheng et al., Citation2021) or consumer behavior (Le & Hancer, Citation2021).

In relation to COVID-19, SMIs’ demonstration of getting vaccinated or wearing face masks may be efficient in stimulating similar behavior among their followers. Some SMIs used their popularity to act as exemplars of social distancing, by, e.g., gathering at virtual parties (Abidin, Citation2021). Such behavior may affect followers’ willingness to accept their advice. In fact, Pöyry et al. (Citation2022) identified SMIs’ role model function as the most powerful way of exerting an impact on followers. Potential explanations for the higher relevance of SMIs as role models might be attributed to their relatability (Schouten et al., Citation2020) or to their display of personal experiences with health-related measures, such as vaccinations (Bonnevie et al., Citation2020). The combination of SMIs’ personal testimony and their characterization as ordinary people who nevertheless have celebrity status (Martensen et al., Citation2018) makes them appear to be attainable role models, which distinguishes them from other communicators like traditional celebrities, experts, or politicians.

Thus, when young people intend to follow SMIs’ example, and the latter is in line with measures communicated by authorities, young people may have higher risk perceptions and vaccination intentions. In contrast, when SMIs refuse to comply with effective measures to curb the spread of the virus, their behavior might also be mimicked by their followers. There are two explanations why such actions may be appraised by followers. First, if the observed behavior is not punished—i.e., young people do not witness their role models suffering negative consequences due to their behavior—followers may believe that its reproduction will not have repercussions (Bandura, Citation1971). Second, a manifested trust in SMIs as role models in the context of COVID-19 may motivate followers to ignore the harmfulness of SMIs' behavior (Festinger, Citation1957). Consequently, after they are exposed to SMIs who are defiant, followers may develop behavior and attitudes that are obstructive in working toward a common societal goal. Thus, we expect that perceiving SMIs as a role model keeps followers from adopting protective COVID-19-related behaviors when SMIs demonstrate noncompliant behavior.

H5:

Seeing SMIs as a role model around COVID-19 determines young people’s risk perceptions as a function of SMIs’ demonstrated compliance with COVID-19 measures.

H6:

Seeing SMIs as a role model around COVID-19 determines young people’s vaccination intentions as a function of SMIs’ demonstrated compliance with COVID-19 measures.

displays the full hypothesized model.

Figure 1. Hypothesized model.

Method

To test our hypotheses, we used data from a two-wave panel survey among a youth sample (16–21 years, 55% female, MageT1 = 19.10, SDageT1 = 1.57) in Germany (NT1 = 978, NT2 = 415). The data, the appendix, and the R script used for data analysis are available on OSF: https://osf.io/j927k/.

Between the two waves, we had a time lag of four months (T1 = March/April 2021, T2 = August/September 2021). With this timing, our study took place during the first peak of the vaccination campaign in Germany, which started at the end of 2020 with a step-by-step plan that prioritized older and vulnerable populations as well as those working in critical infrastructure (e.g., hospitals). Thus, at the beginning of March 2021, roughly 5% of the total population had received their first shot, a number that reached 68% by the end of September 2021.

Sample

The professional polling institute Dynata recruited a national sample of participants for the study. The opt-in panel matched the distribution of age (up to 67 years), gender, state/region, education, and income in the German population. Inclusion criteria for our study were: (1) between 16 and 21 years old during the initial wave, and (2) being active on at least one social media platform. Due to the difficulty of reaching a large youth sample within two waves, no representative quotas were implemented; instead, the sampling aimed to achieve a diverse mix of genders, ages, and educational backgrounds. It is likely that the final sample closely reflected the distribution of gender and age in the German population of 16- to-21-year-olds, although female and older participants were slightly overrepresented compared to the general population. Since exact census data on this age group does not exist, we aimed to match the characteristics of the general population of 15- to 25-year-olds in Germany (Gesundheitsberichterstattung des Bundes, Citation2023). With regard to education, the sample was diverse (1% no degree, 2% secondary education degree, 11% intermediate school degree, 81% high school degree, 5% university of applied sciences degree).

Procedure

Consent was obtained from participants in both waves. Additionally, at Wave 1, several criteria were applied to exclude unreliable respondents and ensure data quality; these criteria excluded participants who (a) took less than one-third of the median survey response duration (n = 77 excluded), (b) answered “not at all” when asked if they had focused on answering the items (n = 6 excluded), or (c) who did not pass any of the three attention checks embedded within the survey, taken from a list by Beach (Citation1989) and Dunn et al. (Citation2018) (n = 37 excluded).

The questions for this study were embedded in a larger panel survey that also contained questions about other topics unrelated to the present research. In line with scholars in communication science, we chose the age group of 16–21 years to reflect youth (e.g., Kahne et al., Citation2011), who are typically considered SMIs’ main target group (e.g., Djafarova & Matson, Citation2021; Newman et al., Citation2021). We obtained ethical approval from the institutional internal review board [ID: 20210315_019]. To ensure that panel mortality did not affect our findings, we conducted attrition tests to rule out attrition bias (see Table S1 in the appendix).

Measures

Except where indicated otherwise, all items were measured on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 “never” to 5 “all the time”. Section A1 in the appendix on OSF (https://osf.io/j927k) displays item wordings for each measure. Table S2 in the appendix shows the zero-order correlations. After providing participants with a definition of social media and of SMIs,Footnote1 we measured exposure to SMIs’ COVID-19 content—the perceived extent to which the SMIs followed by young adults addressed the topics of the COVID-19 disease and vaccinations – with two items adapted from Zimmermann et al. (Citation2022, e.g., “The influencers I follow have talked about the coronavirus”), MT1 = 2.93, SDT1 = 1.12, rT1 = .65***; MT2 = 3.09, SDT2 = 1.08, rT2 = .69***. Importance of SMIs as an information source regarding COVID-19 was measured with one item, also taken from Zimmermann et al. (Citation2022, i.e., “How important are influencers to you as a source of information about the coronavirus?”), MT1 = 2.11, SDT1 = 1.18; MT2 = 2.11, SDT2 = 1.15; responses to this question were measured from 1 “not important at all” to “5 very important”. Considering SMIs as a role model for dealing with COVID-19 was measured with three items inspired by Casaló et al. (Citation2020, e.g., “I follow the recommendations of influencers regarding coronavirus vaccination”), MT1 = 1.82, SDT1 = 0.92, Cronbach’s = .86; MT2 = 1.92, SDT2 = 1.02 , Cronbach’s = .88.

Institutional mistrust was assessed on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 “do not agree at all” to 5 “fully agree”, with four items based on Rieger and He-Ulbricht (Citation2020, e.g., “I have no trust in the official information of the German government about the coronavirus”), MT1 = 2.39, SDT1 = 1.09, Cronbach’s = .87; MT2 = 2.29, SDT2 = 1.07, Cronbach’s

= .88. Drawing from Sherman et al. (Citation2021), we used three items to measure low risk perception of COVID-19 (e.g., “I do not think that COVID-19 is a dangerous disease”), MT1 = 2.34, SDT1 = 1.05, Cronbach’s

= .80; MT2 = 2.37, SDT2 = 1.11, Cronbach’s

= .85 on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 “do not agree at all” to 5 “fully agree”. We measured SMIs’ noncompliance with COVID-19 measures with two items (e.g., “Please indicate how often influencers you follow post content (text, images, videos) where they do not adhere to the coronavirus regulations”), MT1 = 2.65, SDT1 = 1.17, rT1 = .76***; MT2 = 2.53, SDT2 = 1.19, rT2 = .82***. To assess COVID-19-related vaccination intentions, we first asked a filter question of whether people had already been vaccinated; those who answered with “no” (nT2 = 94) received the following question, based on Sherman et al. (Citation2021): “How likely are you to get vaccinated against coronavirus?” Participants answered 1 “very unlikely” to 11 “highly likely”, MT1 = 7.50, SDT1 = 3.38; MT2 = 5.43; SDT2 = 3.20.Footnote2 We also assessed individuals’ vaccination status at T1 (94% unvaccinated, 6% vaccinated) and at T2 (25% unvaccinated, 75% vaccinated).

Control variables

In addition to gender, age, and education, we measured two other control variables: frequency of SMI exposure measuring how often participants see content from SMIs in general, with three items (e.g., “I look at posts by influencers,” on a scale from 1 “never” to 5 “all the time”), MT1 = 3.43, SDT1 = 1.13; MT2 = 3.35, SDT2 = 1.14, as well as subjective knowledge about COVID-19, with two items (e.g., “I know enough about the coronavirus disease to make an informed decision about whether or not to get vaccinated”, on a scale from 1 “does not apply at all” to 5 “fully applies”), MT1 = 3.54, SDT1 = 1.15; MT2 = 3.72 SDT2 = 1.12. Controlling for these variables in the data analysis ensured that intensity of exposure to SMIs’ content in general and subjective knowledge about COVID-19—which has been found to be crucially associated with the type of information individuals used during the pandemic (Gerosa et al., Citation2021)—did not act as confounding variables that would produce spurious correlations between the variables of interest.

Data analysis

We ran stepwise multiple regression analyses to test our hypotheses using the conventional significance level of = 0.05. We controlled for autoregressive effects—i.e., the values of a variable at T1 (e.g., vaccination intention at T1) were included when predicting the variable at T2 (e.g., vaccination intention at T2). This approach enabled us to control for time-varying factors that may influence the variables of interest, to establish the temporal order of relationships, and to reduce issues of reverse causality inherent to cross-sectional designs. We ran separate models for the two dependent variables, due to the high number of missing values on vaccination intention. The analyses with vaccination intention as the dependent variable included N = 94 cases at Time 2, because only individuals who indicated not (yet) being vaccinated received this question. We calculated attrition bias related to risk perception and age, and we found that those participants who remained in the sample were significantly younger and had higher risk perceptions of COVID-19 than those who dropped out after T1 (see Appendix A2). Therefore, we controlled for age but also for autoregressive effects (i.e., the predictor of the dependent variable at Time 1) in all analyses. In addition, we used gender, a dichotomous variable of education, frequency of SMI exposure, and subjective knowledge about COVID-19 as control variables.

Results

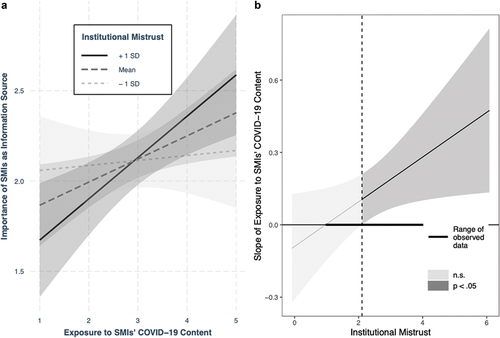

and show all our findings. First, we tested H1, which postulated that exposure to COVID-19 content from SMIs would increase the subjective importance of SMIs as COVID-19 information sources among those with higher levels of institutional mistrust. The results revealed that greater exposure to SMIs’ content on COVID-19 over time was indeed related to a higher subjective importance of SMIs as COVID-19 information sources when individuals reported higher institutional mistrust (b = 0.09, SE = 0.04, p = .032). Probing the interaction effect using the Johnson-Neyman technique revealed that individuals with institutional mistrust above 2.10 reported a higher subjective importance of SMIs as COVID-19 information sources upon exposure to COVID-19 communication from SMIs (). Thus, H1 was supported.

Figure 2. Results of hypothesized relationships.

Figure 3. Effect of exposure to SMIs’ COVID-19 content (T1) on the importance of SMIs as information source (T2) moderated by institutional mistrust (T1).

Table 1. Results of autoregressive stepwise multiple regression models.

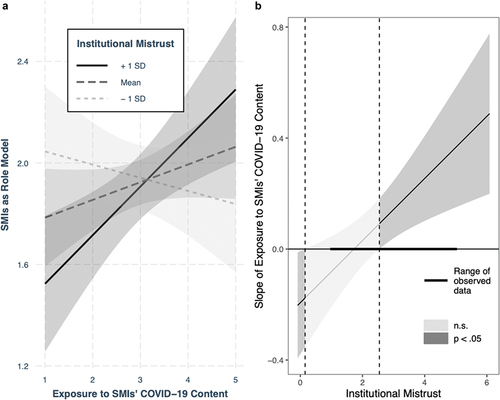

Next, we tested H2, which stated that exposure to COVID-19-related content from SMIs would increase perceptions of SMIs as role models for dealing with the pandemic among those with higher levels of institutional mistrust. The findings revealed that among those with higher institutional mistrust, more exposure to SMIs’ content on COVID-19 was indeed significantly related to stronger perceptions of SMIs as role models (b = 0.11, SE = 0.04, p = .002). Probing the interaction revealed that the association was significant for individuals with levels of mistrust higher than 2.54 (). Therefore, H2 was also supported. Moreover, at very low levels of institutional mistrust – below 0.15 and thus below the observed values for this variable – the association between exposure to SMIs’ COVID-19 content and perceptions of SMIs as role models was negative, suggesting that individuals would be less likely to perceive SMIs as a role model when exposed to their COVID-19-related content if they placed very high trust in conventional sources.

Figure 4. Effect of exposure to SMIs’ COVID-19 content (T1) on the perception of SMIs as role model (T2) moderated by institutional mistrust (T1).

Subsequently, we investigated whether perceiving SMIs as information sources would reduce risk perceptions when exposed to SMIs who did not comply with the COVID-19 measures in place (H3). We found that the subjective importance of SMIs as information sources at T1 was not related to risk perceptions at T2 as a function of SMIs’ compliance with COVID-19 measures (b = 0.01, SE = 0.03, p = .665). Hence, H3 was not supported.

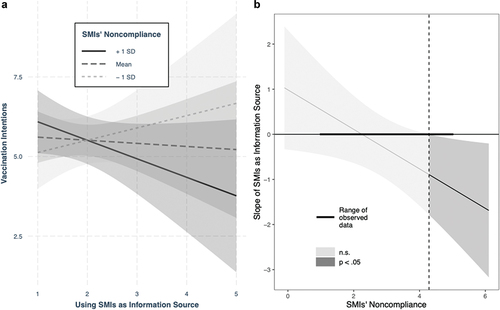

However, H4 – which postulated that the subjective importance of SMIs as information sources about COVID-19 would affect vaccination intentions as a function of compliance with COVID-19 measures – was supported (b = −0.44, SE = .20, p = .034). Probing the interaction revealed a significant negative association between the subjective importance of SMIs as COVID-19 information sources and vaccination intentions for those who were heavily exposed to noncompliant SMIs (4.29 on a 5-point scale, ).

Figure 5. Effect of perceiving SMIs as information source about COVID-19 (T1) on vaccination intentions (T2) moderated by SMIs’ noncompliance (T1).

Thereafter, we tested H5, which stated that seeing SMIs as role models for dealing with COVID-19 would impact risk perceptions as a function of SMIs’ noncompliance with COVID-19 measures; we found that this was not the case (b = 0.02, SE = 0.04, p = .706). Similarly, H6 – postulating that perceiving SMIs as role models for dealing with COVID-19 would negatively affect vaccination intentions as a function of SMIs’ noncompliance with COVID-19 measures – was not supported (b = −0.19, SE = 0.28, p = .514).

Of the covariates, higher subjective COVID-19 knowledge was negatively related to using SMIs as a COVID-19 information source (b = −0.14, SE = 0.05, p = .003). Additionally, young men were more likely than young women to use SMIs as information sources (b = −0.36, SE = 0.11, p = .002), to see them as role models (b = −0.21, SE = 0.10, p = .029), and to have lower risk perceptions (b = −0.29, SE = 0.09, p = .002; ) at T2.

Exploratory analyses

We also tested whether there were reverse influences of the outcomes on the predictors or moderators. These analyses revealed that vaccination intentions at T1 (b = −0.07, SE = 0.02, p < .001) and subjective knowledge about COVID-19 vaccination at T1 (b = −0.08, SE = 0.04, p = .036) negatively predicted institutional mistrust at T2. Additionally, perceiving SMIs as role models at T1 was related to higher exposure to SMIs’ content on COVID-19 at T2 (b = 0.15, SE = 0.07, p = .038).

Discussion

Nowadays, most young people pay more attention to information from social media influencers (SMIs) than to journalists or politicians (Newman et al., Citation2021, Citation2023). Against this background, it is vital to study the interplay between exposure to SMIs, trust in legacy media and political institutions, and use of SMIs by youth for information and advice. Using a longitudinal two-wave panel survey, this study was the first to investigate the conditions and consequences of turning to SMIs as information sources and role models during the COVID-19 pandemic. Specifically, among a youth sample of 16- to 21-year-olds, we studied (1) whether institutional mistrust intensified SMIs’ role as information sources and role models, and (2) how seeking information and advice from SMIs affected young people’s risk perceptions and vaccination intentions, as a function of SMIs’ (non)compliance with COVID-19 measures. Importantly, our study had its first wave before the first peak of the German vaccination campaign in 2021, when most of the participants were still unvaccinated – and when conflicting information about the different vaccines prevailed, and official COVID-19 measures fluctuated. Therefore, exposure to SMIs’ COVID-19 content at T1 took place in a time period that was marked by high uncertainty (Noar & Austin, Citation2020), which can increase information-oriented use of social media (Van Aelst et al., Citation2021) and motivate people to seek out alternative news sources (Zhou & Roberto, Citation2022).

Our findings contribute to the literature in several important ways. First, we demonstrated that social media followers with a certain level of institutional mistrust were more likely to consider SMIs as an important information source when they were exposed to the latter’s COVID-19-related content. This finding can be seen as being in line with the RISP model (Griffin et al., Citation1999), which suggests that information-seeking is explained by the amount of knowledge one currently has compared to the level of knowledge one aspires to gain. Individuals who mistrust institutions may perceive higher information-seeking gratification from SMIs’ communication on COVID-19, because they have a stronger need for information that deviates from information delivered via official communication channels, such as legacy media or political actors. At this point, SMIs arise as opinion leaders (Katz & Lazarsfeld, Citation2006): their ability to simplify complex problems, present information in a more interesting way, or provide orientation (Stehr et al., Citation2015) set SMIs apart from traditional news media, whose content is seen as less engaging and more objective in comparison (Zimmermann et al., Citation2022). As a result, SMIs’ coverage of “serious” topics is likely to be more aligned with the information preferences of young people, who disapprove of traditional news sources and their communication style (Newman et al., Citation2023). In contrast, those with preexisting trust in legacy media and in established political organizations were less likely to perceive SMIs as a relevant information source despite increased exposure to COVID-19-related content from SMIs. This observation may be explained by such individuals’ tendency to seek out information sources they had already deemed reliable before the crisis (Van Aelst et al., Citation2021), eliminating the need to find alternative sources.

Furthermore, our findings also contribute to the literature by showing that SMIs served as role models for dealing with the pandemic, which is consistent with previous research indicating that SMIs act as role models for sociopolitical issues in general (Zimmermann et al., Citation2022). However, again, our findings revealed that only those young people who were more heavily exposed to COVID-19-related content and harbored at least some institutional mistrust perceived SMIs as role models concerning COVID-19: if individuals fully trusted political institutions and legacy media on the topic of COVID-19, they did not accept SMIs as either important information sources or as vital role models. Extant research indicates that there are subgroups of lifestyle and wellness SMIs but also politically right-wing SMIs (Rothut et al., Citation2023) who adopted an anti-vaccine position during the pandemic (Baker, Citation2022), which may have especially resonated with followers who were already somewhat suspicious of institutions such as the pharmaceutical industry, legacy media, or the government (Lewis, Citation2020).

Contrary to our expectations, neither SMIs’ reproducible COVID-19-related behavior nor the information that they provided on this topic determined young people’s risk perceptions. However, those who considered SMIs as an important information source at the first wave expressed lower vaccination intentions at the second wave – but only if they were heavily exposed to noncompliant behavior by SMIs. This finding was independent of followers’ self-perceived knowledge about COVID-19 vaccines.

In contrast, perceptions of SMIs as role models did not lead to a lower willingness to get vaccinated among youth when these SMIs were noncompliant. Rather than being impacted by the examples that SMIs are generally able to provide (e.g., Sokolova & Perez, Citation2021), youth were instead swayed by what “noncompliant” SMIs had to say about COVID-19 and the values they conveyed in relation to these issues. One explanation for why vaccination intentions, but not risk perceptions, were malleable is that at the time of the study, noncompliant SMIs primarily discussed whether or not to get vaccinated, which was a highly salient topic in summer 2021 in Germany; therefore, the timing of the study may explain why we observed an impact on vaccination intentions but not on risk perceptions in general, as the latter may have already been rather consolidated at this point. The fact that those who stayed in the sample across the two waves already had higher risk perceptions of COVID-19 at the first wave underlines this point.

Notably, only a damping effect on vaccination intentions was visible; the reverse positive effect was absent. In other words, observing compliant behavior by SMIs during the pandemic did not have a stimulating effect on vaccination intentions for those seeing SMIs as information sources. This finding suggests that followers are especially open to receiving advice that diverges from official communication about the pandemic.

The longitudinal character of our data allowed us to test whether reciprocal effects occurred. These additional analyses suggest that followers are not merely passively exposed to SMIs’ content, but rather that followers purposefully select SMIs for their COVID-19-related content (Knobloch-Westerwick, Citation2015). Specifically, we observed that those young people who perceived SMIs as role models for dealing with COVID-19 at the first wave were also more likely to be exposed to COVID-19-related content from SMIs at the second wave. Therefore, the findings suggest that youth are both incidentally and intentionally exposed to COVID-19-related content from SMIs, which might hold different implications in terms of attitude formation and behavior (Knoll et al., Citation2020). Future research should study the specific implications of these different exposure modes in relation to attitude and behavior change.

Our covariates revealed that young men were generally more likely to perceive SMIs as an important source of information about COVID-19 and overall had lower risk perceptions. This finding is in line with previous research showing that male social media users are more likely to expose themselves to alternative news sources (Müller & Schulz, Citation2021). Furthermore, we observed a direct association of self-perceived knowledge about COVID-19 and using SMIs as an information source, which indicates that SMIs may be particularly sought out as (alternative) news sources by young adults who consider themselves to be less knowledgeable and in need of more information than well-informed individuals.

Taken together, our findings suggest that youth who question the official communications of legacy media and the government seemed to turn to SMIs for orientation during the pandemic. Our results also indicate a dynamic that is obstructive to social cohesion during a crisis like the COVID-19 pandemic, since those who harbored institutional mistrust at the outset considered SMIs as useful COVID-19 information sources after they were exposed to such content, which further increased their resistance to officially recommended measures when those SMIs displayed noncompliant behavior.

Limitations and future research

Our study has some notable limitations. First, we asked about the intensity at which SMIs spoke about the topic of COVID-19, but we did not assess more detailed information about the type of SMI or the characteristics of the content, which should be considered in future research. Relatedly, we only studied SMIs’ noncompliance with the COVID-19 measures that were in place; we did not investigate the risk of SMIs spreading unverified or misleading information. This should be a critical avenue for future research, since existing evidence suggests that misinformation about COVID-19 provided by SMIs may have negative consequences for followers if SMIs are seen as a trusted source (Harff et al., Citation2022).

Second, we only used one item to assess perceiving SMIs as an information source, which might have fallen short of tapping into the different motives for and dimensions of accepting SMIs as a relevant information source. This should be extended in follow-up work, and future research should employ nuanced measures to evaluate the contradictory information and behaviors shared by SMIs in opposition to academic consensus and official measures.

Third, at 58%, the drop-out rate in the second wave of our study was rather high, due to the difficult reachability of youth aged 16–21 years and the time lag of four months. Additionally, at the time of wave 2 (in August/September 2021), most young people in Germany already had access to vaccination, which is why our sample at T2 had only 94 individuals left for whom we could still investigate vaccination intentions. Nevertheless, a power analysis with G*power for multiple regression analyses with 11 predictors suggests that we were able to detect significant changes in R2 for a single predictor for small effects – as small as f2 = .035, with a power of 1 – = .95 and

= .05 with our sample size – at T2. In addition, for the limited part of the sample that was not yet vaccinated (NT2 = 94), we were still able to detect moderate effects of f2 = .15 with a power of 1 –

= .95 and

= .05. While we had enough power to detect the association of perceiving SMIs as an information source with vaccination intentions, we may have missed a potential smaller relationship between considering SMI as role models and vaccination intentions; however, these smaller effects may also be less relevant when trying to pinpoint the impact of SMIs on society at large.

Fourth, although we controlled for sociodemographic variables, autoregressive effects, and key variables that may be systematically related to both the predictor and the outcome (i.e., frequency of exposure to SMIs’ content and subjective knowledge about COVID-19), we cannot rule out that unobserved third variables had an impact on our findings. Nevertheless, by controlling for the autoregressive effects, this risk is mitigated.

Finally, we focused solely on institutional mistrust as a moderator of COVID-19 exposure and perceptions of SMIs as important information sources and role models. Follow-up research should take on other factors that may strengthen or mitigate this association, such as news avoidance or trust in information that comes directly from people (Hameleers et al., Citation2017).

Implications

Our study has important implications for both practice and theory-building in the still-very-new field of SMIs’ sociopolitical communication. Theoretically, our findings suggest that, in a climate where traditional channels of information are increasingly doubted (Newman et al., Citation2023), modern opinion leaders become more influential. Consequently, these findings imply the necessity of reevaluating the original concept of the two-step flow of communication (Katz & Lazarsfeld, Citation2006), which theorizes that information from mass media is transmitted to audiences through opinion leaders. Our findings indicate that opinion leaders did not merely relay information from mass media; instead, they may obtain and pass on information from alternative sources, or at least provide an alternative spin to mass-mediated information – a tendency that has been previously observed among SMIs engaging in communication on vaccines (Baker, Citation2022). Furthermore, conceptual models of SMIs’ persuasive impact should include institutional mistrust as a key construct to explain differential susceptibilities to SMIs’ communication and model it as intersecting with factors that may increase vulnerability to institutional mistrust, such as gender, education, or belonging to a minority group. Our findings provide the first indications in that regard, showing that young men may be more susceptible to (mis)information provided by SMIs.

On a practical level, the results provide important insights for governments, policymakers, and stakeholders in (media) education, who must evaluate the perceived credibility and potential shortcomings of SMIs as alternative sources of health-related and political information. Based on our findings, we can put forth three concrete practical recommendations. First, our findings suggest that SMIs’ COVID-19-related communication held limited value to those who already trusted the government and legacy media institutions, since using SMIs to promote compliant behavior did not have an incremental impact on young people’s vaccination intentions. Instead, SMIs’ sway is discernible among those who distrusted official institutions and exposed themselves to SMIs who overtly defied COVID-19 regulations and sowed doubt in institutional measures to combat the virus. These findings may be generalized to contested sociopolitical topics at large, suggesting that when collaborating with SMIs, governments and public health organizations should try to target SMIs with audiences who may harbor low trust in institutions and avoid legacy media, rather than invest in SMIs who “preach to the converted”. From an ethical perspective, SMIs’ collaborations with organizations or a government should always be fully disclosed and transparent on both sides.

Second, in this time of increasing media mistrust and declining attention to legacy media among young people (Newman et al., Citation2023), stakeholders in politics, the media, and academia need to take SMIs’ role as news providers and advocates for sociopolitical topics seriously. Their content needs to be brought into the public spotlight in order to be able to understand how young people learn about the world and how they can potentially be misinformed by these sources. Researchers and politicians alike are called on to invest and engage in intense research efforts in this area and to provide accessible science communication that reaches teachers, parents, and young people across different sociodemographic segments (to prevent structural inequalities). In particular, stakeholders responsible for media literacy programs need to be aware of the role and the persuasive power of SMIs in domains like health or politics and must actively address it in school, in order to equip young people with the tools to critically evaluate the quality of sources and content online.

Finally, recent evidence suggests that interventions to prevent youth from acceptance of misinformation are most successful when they are specific and targeted at those who already have a preexisting understanding of the domain (Amazeen et al., Citation2022). Against this backdrop, school education must put a stronger focus on boosting young people’s issue-specific knowledge on contested topics (such as COVID-19) so as to keep them from uncritically accepting information from questionable sources. To mitigate structural inequalities with regard to vulnerability to misinformation, strengthening issue-specific knowledge and online media literacy needs to become a priority across all schools, of all types.

Appendix.docx

Download MS Word (37.2 KB)Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Kevin Koban and Jörg Matthes, who enabled the data collection for this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2023.2286408.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. We defined social media in this study as all social networks (e.g., Instagram), microblogging platforms (e.g., Twitter), video-sharing platforms (e.g., YouTube), and instant messaging services (e.g., WhatsApp). We defined influencers as “highly popular social media users with usually at least 10,000 followers who share their opinions about certain topics, brands, or products in posts, videos or images.” We also mentioned examples of German influencers, such as Dagi Bee, Rezo, Pamela Reif, Julien Bam, and Toni Mahfud, among others.

2. In August 2021, only the first shot was available for the general population of this age group in Germany.

References

- Abidin, C. (2021). Singaporean influencers and covid-19 on Instagram stories. Celebrity Studies, 12(4), 693–698. https://doi.org/10.1080/19392397.2021.1967604

- Abidin, C., Lee, J., Barbetta, T., & Miao, W. S. (2021). Influencers and COVID-19: Reviewing key issues in press coverage across Australia, China, Japan, and South Korea. Media International Australia, 178(1), 114–135. https://doi.org/10.1177/1329878X20959838

- Allgaier, J. (2020). Rezo and German climate change policy: The influence of networked expertise on YouTube and beyond. Media and Communication, 8(2), 376–386. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v8i2.2862

- Allington, D., Duffy, B., Wessely, S., Dhavan, N., & Rubin, J. (2021). Health-protective behaviour, social media usage and conspiracy belief during the COVID-19 public health emergency. Psychological Medicine, 51(10), 1763–1769. https://doi.org/10.1017/S003329172000224X

- Amazeen, M. A., Krishna, A., & Eschmann, R. (2022). Cutting the bunk: Comparing the solo and aggregate effects of prebunking and debunking COVID-19 vaccine misinformation. Science Communication, 44(4), 387–417. https://doi.org/10.1177/10755470221111558

- Baker, S. A. (2022). Alt. health influencers: How wellness culture and web culture have been weaponised to promote conspiracy theories and far-right extremism during the COVID-19 pandemic. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 25(1), 3–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/13675494211062623

- Bandura, A. (1971). Social learning theory. General Learning Press.

- Beach, D. A. (1989). Identifying the random responder. The Journal of Psychology, 123(1), 101–103. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.1989.10542966

- Berryman, R., & Kavka, M. (2017). ‘I guess a lot of people see me as a big sister or a friend’: The role of intimacy in the celebrification of beauty vloggers. Journal of Gender Studies, 26(3), 307–320. https://doi.org/10.1080/09589236.2017.1288611

- Bonnevie, E., Rosenberg, S. D., Kummeth, C., Goldbarg, J., Wartella, E., Smyser, J., & Visram, S. (2020). Using social media influencers to increase knowledge and positive attitudes toward the flu vaccine. PLoS ONE, 15(10), Article e0240828. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0240828

- Briones, R., Nan, X., Madden, K., & Waks, L. (2012). When vaccines go viral: An analysis of HPV vaccine coverage on YouTube. Health Communication, 27(5), 478–485. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2011.610258

- Casaló, L. V., Flavián, C., & Ibáñez-Sánchez, S. (2020). Influencers on Instagram: Antecedents and consequences of opinion leadership. Journal of Business Research, 117, 510–519. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.07.005

- Castro, L., Strömbäck, J., Esser, F., Van Aelst, P., de Vreese, C., Aalberg, T., Cardenal, A. S., Corbu, N., Hopmann, D. N., Koc-Michalska, K., Matthes, J., Schemer, C., Sheafer, T., Splendore, S., Stanyer, J., Stępińska, A., Štětka, V., & Theocharis, Y. (2022). Navigating high-choice European political information environments: A comparative analysis of news user profiles and political knowledge. The International Journal of Press/politics, 27(4), 827–859. https://doi.org/10.1177/19401612211012572

- CCDF. (2021). The Disinformation Dozen. http://bitly.ws/K42f

- Cheng, Y., Hung-Baesecke, C.-J. F., & Chen, Y.-R.-R. (2021). Social media influencer effects on CSR communication: The role of influencer leadership in opinion and taste. International Journal of Business Communication, 232948842110351. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F23294884211035112

- Chinn, S., Hiaeshutter-Rice, D., & Chen, K. (2023). How science influencers polarize supportive and skeptical communities around politicized science: A cross-platform and over-time comparison. Political Communication. Advance Online Publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2023.2201174

- Dekoninck, H., & Schmuck, D. (2022). The mobilizing power of influencers for pro-environmental behavior intentions and political participation. Environmental Communication, 16(4), 458–472. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2022.2027801

- Dekoninck, H., Van Houtven, E., & Schmuck, D. (2023). Inspiring G(re)en Z: Unraveling (para) social bonds with influencers and perceptions of their environmental content. Environmental Communication, 17(7), 701–719. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2023.2237693

- Djafarova, E., & Matson, N. (2021). Credibility of digital influencers on YouTube and Instagram. International Journal of Internet Marketing, 15(2), 131–148. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJIMA.2021.114338

- Dunn, A. M., Heggestad, E. D., Shanock, L. R., & Theilgard, N. (2018). Intra-individual response variability as an indicator of insufficient effort responding: Comparison to other indicators and relationships with individual differences. Journal of Business and Psychology, 33(1), 105–121. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-016-9479-0

- Feng, Y., Chen, H., & Kong, Q. (2021). An expert with whom I can identify: The role of narratives in influencer marketing. International Journal of Advertising, 40(7), 972–993. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2020.1824751

- Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Row, Peterson & Company.

- Fetters Maloy, A., & De Vynck, G. (2021, September 12). How wellness influencers are fueling the anti-vaccine movement. The Washington Post. https://wapo.st/3kqIe9z

- Gerosa, T., Gui, M., Hargittai, E., & Nguyen, M. H. (2021). (Mis)informed during COVID-19: How education level and information sources contribute to knowledge gaps. International Journal of Communication, 15, 2196–2217. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/16438/3438

- Gesundheitsberichterstattung des Bundes. (2023). Indikator 1 der ECHI shortlist: Bevölkerung nach Geschlecht und Alter [Indicator 1 of the ECHI shortlist: Population by gender and age]. Statistisches Bundesamt. http://bitly.ws/K3I3

- Gleason, T. R., Theran, S. A., & Newberg, E. M. (2017). Parasocial interactions and relationships in early adolescence. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, Article 255. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00255

- Griffin, R. J., Dunwoody, S., & Neuwirth, K. (1999). Proposed model of the relationship of risk information seeking and processing to the development of preventive behaviors. Environmental Research, 80(2), S230–S245. https://doi.org/10.1006/enrs.1998.3940

- Hameleers, M., Bos, L., & de Vreese, C. H. (2017). The appeal of media populism: The media preferences of citizens with populist attitudes. Mass Communication and Society, 20(4), 481–504. https://doi.org/10.1080/15205436.2017.1291817

- Harff, D., Bollen, C., & Schmuck, D. (2022). Responses to social media influencers’ misinformation about COVID-19: A pre-registered multiple-exposure experiment. Media Psychology, 25(6), 831–850. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2022.2080711

- Harff, D., & Schmuck, D. (2023). Influencers as empowering agents? Following political influencers, internal political efficacy and participation among youth. Political Communication, 40(2), 147–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2023.2166631

- Hudders, L., De Jans, S., & De Veirman, M. (2021). The commercialization of social media stars: A literature review and conceptual framework on the strategic use of social media influencers. International Journal of Advertising, 40(3), 327–375. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2020.1836925

- Kahne, J., Middaugh, E., Lee, N.-J., & Feezell, J. (2011). Youth online activity and exposure to diverse perspectives. New Media & Society, 14(2), 492–512. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444811420271

- Kaiser, S., Kyrrestad, H., & Martinussen, M. (2021). Adolescents’ experiences of the information they received about the coronavirus (Covid-19) in Norway: A cross-sectional study. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 15(1), Article 30. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-021-00384-4

- Kalogeropoulos, A., Suiter, J., Udris, L., & Eisenegger, M. (2019). News media trust and news consumption. Factors related to trust in news in 35 countries. International Journal of Communication, 13, 3672–3693. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/10141

- Katz, E., & Lazarsfeld, P. F. (2006). Personal influence. The part played by people in the flow of mass communications (2nd ed.). Transaction Publishers (Original work published 1955)

- Khamis, S., Ang, L., & Welling, R. (2017). Self-branding, ‘micro-celebrity’ and the rise of social media influencers. Celebrity Studies, 8(2), 191–208. https://doi.org/10.1080/19392397.2016.1218292

- Klawier, T., Prochazka, F., & Schweiger, W. (2023). Public knowledge of alternative media in times of algorithmically personalized news. New Media & Society, 25(7), 1648–1667. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448211021071

- Knobloch-Westerwick, S. (2015). The selective exposure self-and affect-management (SESAM) model: Applications in the realms of race, politics, and health. Communication Research, 42(7), 959–985. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650214539173

- Knoll, J., Matthes, J., & Heiss, R. (2020). The social media political participation model: A goal systems theory perspective. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, 26(1), 135–156. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856517750366

- Kroger, J., Martinussen, M., & Marcia, J. E. (2010). Identity status change during adolescence and young adulthood: A meta-analysis. Journal of Adolescence, 33(5), 683–698. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.11.002

- Leader, A. E., Burke-Garcia, A., Massey, P. M., & Roark, J. B. (2021). Understanding the messages and motivation of vaccine hesitant or refusing social media influencers. Vaccine, 39(2), 350–356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.11.058

- Le, L. H., & Hancer, M. (2021). Using social learning theory in examining YouTube viewers’ desire to imitate travel vloggers. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Technology, 12(3), 512–532. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHTT-08-2020-0200

- Lewis, R. (2020). This is what the news won’t show you: YouTube creators and the reactionary politics of micro-celebrity. Television & New Media, 21(2), 201–217. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527476419879919

- Lou, C., & Kim, H. K. (2019). Fancying the new rich and famous? Explicating the roles of influencer content, credibility, and parental mediation in adolescents’ parasocial relationship, materialism, and purchase intentions. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, Article 2567. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02567

- Marchi, R. (2012). With Facebook, blogs, and fake news, teens reject journalistic “objectivity.” Journal of Communication Inquiry, 36(3), 246–262. https://doi.org/10.1177/0196859912458700

- Martensen, A., Brockenhuus-Schack, S., & Zahid, A. L. (2018). How citizen influencers persuade their followers. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal, 22(3), 335–353. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFMM-09-2017-0095

- Müller, P., & Schulz, A. (2021). Alternative media for a populist audience? Exploring political and media use predictors of exposure to Breitbart, Sputnik, and Co. Information, Communication & Society, 24(2), 277–293. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2019.1646778

- Newman, N., Fletcher, R., Eddy, K., Robertson, C. T., & Nielsen, R. K. (2023). Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2023 (12th ed.). Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2023-06/Digital_News_Report_2023.pdf

- Newman, N., Fletcher, R., Schulz, A., Andı, S., Robertson, C. T., & Nielsen, R. K. (2021). Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2021 (10th ed.). Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. https://bit.ly/3zvAuHI

- Noar, S. M., & Austin, L. (2020). (Mis)communicating about COVID-19: Insights from health and crisis communication. Health Communication, 35(14), 1735–1739. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2020.1838093

- Ortiz, R. R., Smith, A., & Coyne-Beasley, T. (2019). A systematic literature review to examine the potential for social media to impact HPV vaccine uptake and awareness, knowledge, and attitudes about HPV and HPV vaccination. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, 15(7–8), 1465–1475. https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2019.1581543

- Pöyry, E., Reinikainen, H., & Luoma-Aho, V. (2022). The role of social media influencers in public health communication: Case COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Strategic Communication, 16(3), 469–484. https://doi.org/10.1080/1553118X.2022.2042694

- Reinikainen, H., Munnukka, J., Maity, D., & Luoma-Aho, V. (2020). ‘You really are a big sister’ - Parasocial relationships, credibility, and the moderating role of audience comments in influencer marketing. Journal of Marketing Management, 36(3–4), 279–298. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2019.1708781

- Riedl, M., Schwemmer, C., Ziewicki, S., & Ross, L. M. (2021). The rise of political influencers—Perspectives on a trend towards meaningful content. Frontiers in Communication, 6, Article 752656. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2021.752656

- Rieger, M. O., & He-Ulbricht, Y. (2020). German and Chinese dataset on attitudes regarding COVID-19 policies, perception of the crisis, and belief in conspiracy theories. Data in Brief, 33, 106384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dib.2020.106384

- Rothut, S., Schulze, H., Hohner, J., & Rieger, D. (2023). Ambassadors of ideology: A conceptualization and computational investigation of far-right influencers, their networking structures, and communication practices. New Media & Society, 146144482311644. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448231164409

- Schäfer, M. S., & Taddicken, M. (2015). Mediatized opinion leaders: New patterns of opinion leadership in new media environments? International Journal of Communication, 9, 960–981. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/2778

- Schmuck, D. (2021). Following social media influencers in early adolescence: Fear of missing out, social well-being and supportive communication with parents. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 26(5), 245–264. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcmc/zmab008

- Schouten, A. P., Janssen, L., & Verspaget, M. (2020). Celebrity vs. influencer endorsements in advertising: The role of identification, credibility, and product-endorser fit. International Journal of Advertising, 39(2), 258–281. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2019.1634898

- Sherman, S. M., Smith, L. E., Sim, J., Amlôt, R., Cutts, M., Dasch, H., Amlôt, R., Rubin, G. J., & Sevdalis, N. (2021). COVID-19 vaccination intention in the UK: Results from the COVID-19 vaccination acceptability study (CoVaccs), a nationally representative cross-sectional survey. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, 17(6), 1612–1621. https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2020.1846397

- Sinclair, S., & Agerström, J. (2023). Do social norms influence young people’s willingness to take the COVID-19 vaccine? Health Communication, 38(1), 152–159. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2021.1937832

- Sokolova, K., & Perez, C. (2021). You follow fitness influencers on YouTube. But do you actually exercise? How parasocial relationships, and watching fitness influencers, relate to intentions to exercise. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 58, Article 102276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102276

- Stehr, P., Rössler, P., Leissner, L., & Schönhardt, F. (2015). Parasocial opinion leadership media personalities’ influence within parasocial relations: Theoretical conceptualization and preliminary results. International Journal of Communication, 9(1), 982–1001. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/2717

- Suuronen, A., Reinikainen, H., Borchers, N. S., & Strandberg, K. (2021). When social media influencers go political: An exploratory analysis on the emergence of political topics among Finnish influencers. Javnost – The Public. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/13183222.2021.1983367

- Theocharis, Y., Cardenal, A., Jin, S., Aalberg, T., Hopmann, D. N., Strömbäck, J., Castro, L., Esser, F., Van Aelst, P., de Vreese, C., Corbu, N., Koc-Michalska, K., Matthes, J., Schemer, C., Sheafer, T., Splendore, S., Stanyer, J., Stępińska, A., & Štětka, V. (2023). Does the platform matter? Social media and COVID-19 conspiracy theory beliefs in 17 countries. New Media & Society, 25(12), 3412–3437. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448211045666

- Valkenburg, P. M., & Peter, J. (2013). The differential susceptibility to media effects model. Journal of Communication, 63(2), 221–243. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12024

- Van Aelst, P., Toth, F., Castro, L., Štětka, V., Vreese, C. D., Aalberg, T., Cardenal, A. S., Corbu, N., Esser, F., Hopmann, D. N., Koc-Michalska, K., Matthes, J., Schemer, C., Sheafer, T., Splendore, S., Stanyer, J., Stępińska, A., Strömbäck, J., & Theocharis, Y. (2021). Does a crisis change news habits? A comparative study of the effects of COVID-19 on news media use in 17 European countries. Digital Journalism, 9(9), 1208–1238. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2021.1943481

- Volkmer, I. (2021). Social media and COVID-19. A global study of digital crisis interaction among Gen Z and Millennials. University of Melbourne. https://bit.ly/3yQ3pra

- Weeks, B. E., & Gil de Zúñiga, H. (2021). What’s next? Six observations for the future of political misinformation research. American Behavioral Scientist, 65(2), 277–289. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764219878236

- Westlund, O., & Ghersetti, M. (2015). Modelling news media use: Positing and applying the GC/MC model to the analysis of media use in everyday life and crisis situations. Journalism Studies, 16(2), 133–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2013.868139

- Zhou, X., & Roberto, A. J. (2022). An application of the risk information seeking and processing model in understanding college students’ COVID-19 vaccination information seeking and behavior. Science Communication, 44(4), 446–474. https://doi.org/10.1177/10755470221120415

- Zimmermann, D., Noll, C., Gräßer, L., Hugger, K.-U., Braun, L. M., Nowak, T., & Kaspar, K. (2022). Influencers on YouTube: A quantitative study on young people’s use and perception of videos about political and societal topics. Current Psychology, 41(10), 6808–6824. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-01164-7