ABSTRACT

Cultural targeting and tailoring are different, yet they remain intertwined in the literature inhibiting theory development and limiting the possibility of determining their effects. This preregistered systematic literature review describes these constructs and provides a framework for cultural tailoring with evidence from a review of 63 studies, published from 2010 to 2020, to characterize the processes, elements, and theories used in the existing literature. The results show that 86% of studies self-defined as cultural tailoring, but coding revealed relatively few tailoring studies (25%) with 31% including both tailoring and targeting elements. Most studies used outreach and consultation as processes for tailoring or targeting with participatory approaches used in a fifth of the studies. Surface-level features of message content were commonly used to tailor or target with deep-cultural-values found in only a quarter of the studies. We argue from theories of communication accommodation and persuasion that cultural tailoring or targeting may provide gains in attention, recall, or source evaluation.

Shaping the content of messages to account for cultural characteristics or underlying cultural values is believed to make messages more effective. The literature on cultural targeting and tailoring of communication interventions (Kreuter et al., Citation2003; Resnicow et al., Citation1999) has flourished in the domain of health communication, particularly in public health (c.f., Joo & Liu, Citation2021; Torres-Ruiz et al., Citation2018), where the concepts are fundamental to practice but there is a dearth of theory to describe, predict, or explain the effects. As a consequence, little is known about the so-called “active ingredients” (Noar et al., Citation2018; O’Keefe, Citation2003) in messages that are matched to the cultural characteristics of the people for whom they are intended. That is, what is it about particular messages that resonate with members of certain cultural groups? In the general message tailoring literature, research is still uncovering the message elements that are important and why, how, and when they function (Jensen et al., Citation2012; Noar et al., Citation2018); the effort to theorize these issues for culturally tailored messages is so far more limited (Huang & Shen, Citation2016).

In this paper, our goal is to present a framework for cultural tailoring processes and content and use it to systematically review the literature as a step toward ultimately theorizing how and why such messages are effective. Because summative studies of cultural targeting or tailoring typically focus on a specific health topic (e.g., cancer, diabetes, etc.; Huang & Shen, Citation2016) or population group (e.g., Asian-Americans; Tan & Cho, Citation2019), it is difficult to draw conclusions about the nature of cultural tailoring across literatures. As such, this paper reports on a systematic literature review of cultural tailoring and targeting of messages across topics and health conditions. Theoretically, we draw from the broader literature on message tailoring generally (e.g., Noar et al., Citation2009, Citation2018) and our prior non-refereed work on this issue (Lapinski & Oetzel, Citation2022). In the following, we provide conceptual definitions for key study concepts and describe a framework for cultural tailoring processes and content which, along with the study research questions, guide our analysis.

Culture and models of cultural tailoring

Cultural tailoring and targeting are conceptually and operationally entangled in the research and disconnected from the literature on intercultural communication and persuasion, impeding progress on theory development. In this review, we take steps toward addressing this issue by examining the state of the literature on cultural tailoring in terms of existing approaches and theoretical models. We conceptualize cultural tailoring as the creation of communication interventions or messages (including verbal and non-verbal content, images, sources, etc.) matched or congruent to the needs and preferences of individuals based on cultural characteristics (Kreuter & Skinner, Citation2000; Kreuter et al., Citation2003). Tailoring is distinct from targeting which involves the design of messages or information for particular groups of people who share some common characteristics yet are different from other groups (Noar et al., Citation2009). Put differently, tailored messages are designed for individual people and targeted messages are for groups of people.

Culture, in this study, is conceptualized as groups or communities characterized based on shared linguistic features, psychological states, values, and belief systems that may separate them from other groups regardless of nation state or geographical boundary. By considering groups based on shared cultural characteristics and identities, we acknowledge the intersection of multiple identities and the distinct needs, patterns of cognition, and preferences for communication.Footnote1 These differences form the basis of the primary argument for cultural tailoring and targeting: that accounting for culturally based elements in messages will improve the effectiveness of those messages. Once group-level cultural variation is identified, key cultural dynamicsFootnote2 can be measured at the individual level and information designed particularly for a group (targeting) or an individual (tailoring).

Although there have been efforts to build theory on message tailoring and targeting broadly that has specified the elements and likely outcomes of tailored messages (Noar et al., Citation2009, Citation2018), theory development for cultural tailoring has been more limited. The starting point for our thinking is Kreuter et al. (Citation2003) model for characterizing the cultural elements of health communication interventions which has generated new research on the role of cultural dynamics in health message design (e.g., Joo & Liu, Citation2021; Tan & Cho, Citation2019; Torres-Ruiz et al., Citation2018). Kreuter et al. (Citation2003) model was one of the first to provide a typology of the ways in which interventions can be considered culturally appropriate; that is, the ways in which health communication interventions can account for culture in their design. By addressing cultural appropriateness of interventions, its focus is broader than message tailoring. Further, it is descriptive and typological rather than designed to explain or predict effects. In their description of the model, Kreuter et al. (Citation2003) clearly stated that the framework they proposed was designed to be used for “organizational clarity” (p. 135) and that the categories they identified were not mutually exclusive nor exhaustive.

Despite the limitations in the Kreuter et al. (Citation2003) approach identified by the authors themselves, it has been used as a typology in subsequent studies to categorize forms of cultural targeting messages in health interventions (de Dios et al., Citation2019) and to frame reviews of research. A review of the cultural targetingFootnote3 strategies used in 33 clinical trials (Torres-Ruiz et al., Citation2018) concluded that most trials use multiple cultural targeting strategies. For example, campaign materials commonly depicted people who were demographically similar to the target audience and presented in the native language of audience members. Practically, a multifaceted approach to message targeting or tailoring makes sense, but from the perspective of building theory, it means it is challenging to identify exactly what it is about messages that impact outcomes. Since prior reviews (e.g., Torres-Ruiz et al., Citation2018) have used Kreuter et al. (Citation2003) typology, which was not mutually exclusive or exhaustive, they fail to fully account for the nature of culturally tailored messages.

Recently, Tan and Cho (Citation2019) revised the Kreuter et al. (Citation2003) framework by 1) refining the conceptual definitions of the components on the model, 2) adding cultural identity as a key part of the model, and 3) describing the organization/flow of key constructs in the model. This makes critical revisions to the model; none-the-less, the original and revised model conflate message content elements with the possible outcomes of tailored messages. For example, one of the message elements describing the design of messages is labeled “peripheral” despite the fact that many elements of messages (along with design features) can be processed peripherally. The models further conflate the process of creating culturally tailored interventions with categories referencing the content of messages, e.g., “constituent involving” messages (those which involve community input in the design) as parallel with content elements rather than a process of message design (Kreuter et al., Citation2003; Tan & Cho, Citation2019). Finally, neither of these models completely account for what is known about message content from intercultural communication or the persuasive message design literature. Nonetheless, these models provide a useful starting point for the current work. In this paper, we propose a framework to refine these models and use this approach as the basis for the systematic review of culturally tailored and targeted studies.

In sum, questions remain about both the process of creation (e.g., How do you design culturally tailored messages?) and the nature (e.g., What element of messages can be culturally tailored?) of such messages. Thus, our framework focuses on the process and content elements of cultural tailoring and presents the cultural tailoring processes/cultural tailoring content (CTP/CTC) framework. This framework focusses on culturally tailored messages but, in principle, can be applied to targeted messages as well to the extent that both processes involve creating and disseminating culturally congruent messages.

The CTP/CTC framework

The CTP/CTC framework we present here distinguishes the processes by which culturally tailored messages are developed from the content of culturally tailored messages. It assumes that different processes and content will likely have different effects on attention and message processing, recall, message and source evaluation, attitudinal, and behavioral outcomes of messages. Conceptualizing the tailoring processes and content elements is a necessary initial step before theorizing about effects. We first describe the processes and then the content elements of the approach.

Cultural tailoring processes

Cultural-tailoring processes (CTP) refer to the methods used to develop all elements of a communication campaign/intervention including the messages. Cultural tailoring processes can function to bring the needs and values of communities to the design of messages to varying degrees; if done well, it can shape the form and content of the messages. CTP may involve some form of community or audience engagement. Community engagement is a “process of working collaboratively with groups of people who are affiliated by geographic proximity, special interests, or similar situations, with respect to issues affecting their well-being” (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Citation1997, p. 9). Systematic reviews of community-engagement processes in intervention design (broadly, some of which include culturally targeted messages) show that higher levels of engagement have positive social and health outcomes relative to those which use a less engaged approach (Carter et al., Citation2015; O’Mara-Eves et al., Citation2015). This does not necessarily indicate that greater community engagement would improve the effects of culturally tailored messages. Decisions about the extent of community engagement in cultural-tailoring processes are dependent on resources, time, community willingness, etc., available as a communication campaign commences. There are five categories of cultural tailoring processes which form a continuum with increasing community involvement: outreach, consultation, involvement, participatory, and community-driven (CTSA, Citation2011; Lapinski & Oetzel, Citation2022; Yuen et al., Citation2015). These processes have been used for intervention design more broadly and can be applied to cultural tailoring or targeting of messages.

Cultural-tailoring processes which involve outreach are those projects that are driven by communication professionals or experts. These projects seek to place campaigns into a community without significant input from the community members. Traditional advertising campaigns may take this form as do algorithmically driven campaigns on social media (Zarouali et al., Citation2022). Consultation involves some discussion with, or data collection from, the community to help design the campaign; however, the final decisions are made by the expert team. Examples of this include using focus groups to design health message content or public participation meetings to inform the design of interventions. Involvement references bidirectional communication among community members and designers and greater levels of cooperation. It includes a limited partnership with the professional or expert team still having leadership over the process. The participatory approach to the process of cultural tailoring involves shared leadership, decision-making, and communication among the expert or professional team and the community. This approach reflects the idea that all partners have expertise that are needed to effectively develop, implement, and evaluate a tailored communication campaign. Community-driven includes strong community leadership that drives all phases of intervention or campaign development and may involve consultation with external research partners who can contribute to the work. These categories of cultural-tailoring processes form the basis for our analysis of the studies we review.

Cultural tailoring content

Accounting for cultural dynamics in intervention content takes various forms. What is missing from the literature is a theory of intercultural communication and message design that describes how and when cultural tailoring of intervention content should be most effective. The cultural tailoring of content (CTC) portion of the CTP/CTC framework addresses the cultural tailoring of message content by refining and extending the Kreuter et al. (Citation2003) framework to isolate the elements of message content that can be tailored and what that might look like in practice. In this framework, we describe the elements of messages and their conceptual definitions, along with examples of how the elements are modified/crafted to address cultural dynamics; these elements form the basis for the coding scheme used in this review. presents the CTC elements.

Table 1. Cultural tailoring of process and content (CTP/CTC) framework.

The elements in the CTC are derived from previous research on cultural tailoring and targeting (Kreuter et al., Citation2003; Resnicow et al., Citation1999; Tan & Cho, Citation2019), intercultural communication (Hall, Citation1976; Hofstede, Citation1980; Orbe, Citation1998), and message design for persuasive communication (e.g., McLaurin, Citation1995; Noar et al., Citation2018; O’Keefe, Citation2003). It extends prior work by expanding the scope of message elements and disentangling cultural-tailoring processes from content. The elements of the CTC framework encompass design, language, structure, and content of messages. Although the message structure and content elements are limitless, we focus only on those elements that are likely to be important for cultural tailoring and for which there is some existing empirical evidence that cultural tailoring along these elements could be important for impacting message outcomes. The elements are meant to be mutually exclusive and exhaustive to allow for coding.

Design elements are the visual, verbal, or non-verbal aspects of messages that highlight demographics, group membership and other surface-level characteristics of culture (). This may include pictures, graphics, and titles that specifically address surface level cultural characteristics or any demographic information known about the person (Resnicow et al., Citation1999). For example, a tailored message may include video of people who are demographically similar (e.g., all young women) to the message receiver, wearing clothes that are common to a region, in the process of doing the behavior recommended in the message. This element is similar to what Kreuter et al. (Citation2003) call the “peripheral” element in their typology, but we eliminate the word peripheral because many elements of a message can be processed peripherally (including potentially the language used, number of arguments, and source characteristics). Design elements do not include evidence from or arguments about a particular cultural group; these elements are covered by other categories.

In terms of the language of a message, we have re-conceptualized linguistic tailoring described in Kreuter et al. (Citation2003) to consider both the language system and communication style as separate elements of messages. By a language system, we mean a system of communication that uses words and combinations of words into sentences through spoken, written, or manual means. It is well known that our thoughts, language, and culture are inextricably connected (e.g., Sapir-Whorf hypothesis; see Hall, Citation1976), that interventions should be provided in the receivers native or preferred language (Resnicow et al., Citation1999), and there is some evidence that the use of language in communication campaigns influences how people respond to them (Ochoa et al., Citation2020). In short, the use of a message recipient’s primary or preferred language can serve as a form of message tailoring.

The language system in which messages are delivered is distinct from the communication style of the message, which addresses the ways in which words (regardless of language system) are used and presented to reflect audience preferences. Communication style includes the verbal, nonverbal, and paraverbal cues which signal how language should be taken, interpreted, filtered, or understood (Norton, Citation1983; see de Vries et al., Citation2009 for a review). There are cultural differences in preferences for direct vs. indirect communication (Kim & Wilson, Citation1994); for the meaning of the message to be explicitly stated or derived from the context (Hall, Citation1976), oral as opposed to multisensory storytelling (Ten Brug et al., Citation2016), as well as communication approaches and accommodation patterns preferred by specific cultural groups (Giles, Citation2016; Orbe, Citation1998).

The logical structure of the content messages includes the form of the arguments and conclusions as well as how they are presented. Arguments and evidence elements involve the inclusion of verbal or visual evidence or warrants which have a connection to the group to which the receiver belongs or which reflect the logical structures preferred by the receiver. This may include statistical or narrative evidence, pictorial evidence in the form of graphs, or other forms of evidence about the issue. For example, a graph may show the prevalence of diabetes within a cultural community or a narrative might describe a particular cultural group member’s experience with the condition. Evidence may be presented alone or in the context of arguments about the issue in the campaign. These messages elements account for culturally based differences in people’s preferences for oral versus formal logic in messages (e.g., McLaurin, Citation1995; Wilkin & Ball-Rokeach, Citation2011) and for differences in reasoning patterns based on culture (Nisbett, Citation2003). A second element of structure is the nature of conclusions or calls to action in messages and culturally based preferences in the nature of the call to action (Nisbett, Citation2003); for example, asking recipients to engaged in a traditional approach to physical activity such as games or dance as opposed to going to the gym is an example of a culturally tailored call to action.

The final set of cultural-tailoring elements are the content elements which address the nature of the actual verbal content of the message. These include the type of appeal (gain/loss, threat, guilt, etc.), identity-related content, content which addresses deep cultural values, and other cognitive, attitudinal and motivational content. The content elements of tailoring require an in-depth understanding of potential receivers’ cognitions and social interactions related to a particular topic to design messages or information that is congruent to their underlying psychographics. Social-psychological dynamics are recognized, reinforced, and built upon in verbal aspects of materials including the type of appeals used in the message (Block, Citation2005; R. Liu & Lapinski, Citation2019), aspects of identity (Markus & Kitayama, Citation1994), deep cultural values (Hofstede, Citation1980; Kluckhohn & Strodtbeck, Citation1961), beliefs (Kleinman & Benson, Citation2006), norms (Gelfand et al., Citation2011), attitudes and prior behaviors (Ting-Toomey, Citation2005). Kreuter et al. (Citation2003), for example, used questionnaires to assess religiousity, collectivism, and racial pride of participants, then tailored messages based on those responses. What remains unknown is how whether or not the elements of cultural tailoring of content and processes are used in the literature and the nature of the content in cultural-tailoring studies. Our research questions address this specifically.

The primary goal of this study is to examine the ways and which cultural-tailoring processes and content occur in the literature by applying the CTP/CTC frameworks. In particular, the questions ask directly about whether the concepts proposed in this new framework are evidenced in the empirical literature on cultural tailoring and targeting. As such, they focus on the specific ways in which cultural tailoring is operationalized in the literature, the ways in which “culture” is defined in the existing literature, and the theories used to explain the effects of culturally tailored messages. Understanding the answers to these questions is a step toward theorizing and ultimately testing the mediators and moderators of the effects of culturally tailored messages on attitudinal and behavioral outcomes. Importantly, because of the confusion in the literature between cultural targeting and tailoring of messages and the relative novelty of cultural tailoring studies, we include both targeted and tailored messages in the review and identify whether the messages were designed for groups or individuals.

RQ1:

What forms of cultural-tailoring processes and cultural tailoring of content (CTC) are utilized in cultural-tailored or culturally targeted studies?

RQ2:

How is culture defined within studies of cultural tailoring and targeting?

RQ3:

What are the (theoretical) explanations offered for the effects of cultural tailoring and targeting?

Method

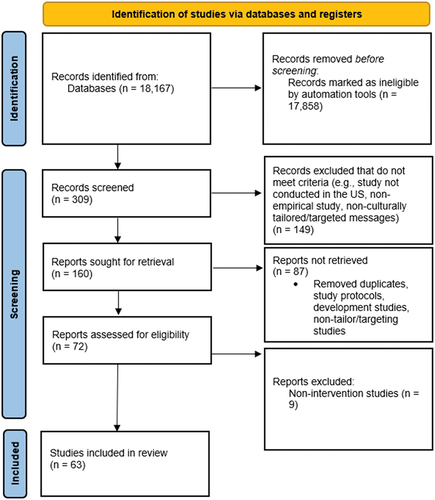

The review was conducted based on the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines; the sections below follow Liberati et al. (Citation2009) guidance for reporting the methods used in systematic literature reviews and meta-analyses. The study protocol was preregistered with PROSPERO May 6, 2021(CRD42021242467).

Information sources and search procedures

The following sources were searched for published literature: Medline, PsychInfo, PubMed, and Communication and Mass Media Complete. The key search terms included were as follows: “cultural tailoring (+messages)” “cultural targetingFootnote4 (+messages)” “cultural sensitivity” “cultural adaptation” “cultural appeals” “cultur* communication*” “tailored communication” and combinations of these terms with health, persuasion, health interventions, behavior change. These terms were searched in the title, abstract, keywords, and full text. The searches were exported to Excel and Zotero.

Eligibility criteria

Included studies required a health communication intervention or campaign which involved exposure of humans to tailored or targeted messages based on some cultural characteristic (including race and ethnicity if used by the authors as a cultural element) and were conducted in the U.S. Randomized control trials, field experiments, lab experiments, observational studies, and studies with either quantitative or qualitative outcome measures were eligible for inclusion. Only peer-reviewed studies of the campaign or intervention, published in English between January 2010 and September 2020 were included. The included studies were limited to a 10-year period because of concerns over the potential volume of studies impacting the feasibility of the study. Studies which described a study protocol or the process of cultural tailoring without implementing a study, reviews, editorials, theory explications and thought-pieces were excluded as were unpublished dissertations and Master’s theses.

Study selection

This search resulted in 18,168 articles. To reduce the initially identified articles, several stages were used. First, three human coders manually coded a small portion of the titles (n = 222) for relevance to the study inclusion and exclusion criteria. Then, the human coding was used to train a natural language processing (NLP) algorithm to code the remaining titles for relevance and the presence of duplicate titles (Marshall & Wallace, Citation2019). That is, NLP was used only for screening for relevance and duplication, not for coding the study variables. The algorithm was programmed in Python to identify relevant and duplicate titles using a bag-of-words approach and the Natural Language Toolkit library. The bag-of-words approach is a way to convert words to numerical representation based on the frequency of the words rather than the sequence of the words. The algorithm identified articles that did not include any of the words from the 222 inclusion words for removal. This resulted in removal of 14,167 articles and resulted in n = 4,000. Next, the abstracts were coded by three human coders and the NLP algorithm was trained to return the number of words in the article relating to the human-coded themes, resulting in the removal of 3,691 articles that did not correspond to any theme. Next, a full text review of the remaining articles (n = 309) was coded by three independent coders for eligibility and the extent to which the studies were relevant to the research questions. The articles that did not meet the criteria were removed after the initial screening including studies used non-US samples, non-empirical studies, and studies that not about culturally targeted or tailored messages. After removing duplicates, 73 articles were assessed for eligibility. Studies without an intervention or campaign (n = 9) were then removed. The final sample included 63 articles which met the inclusion criteria from which data were extracted from the full text of the articles. displays the PRISMA flow diagram. Supplementary Appendix A contains a summary table of the studies included.Footnote5

Data extraction and codebook

For those articles that met the inclusion criteria, data were extracted and coded by human coders. First, three independent coders extracted data that related to the study protocol from the full-text articles. Next, three different researchers cross-checked the initial data extraction and extracted additional material from the articles. These three researchers then coded data from five articles using the CTP/CTC framework to establish intercoder reliability. Intercoder reliability was calculated and coders were retrained until coding exceeded 95% intercoder agreement. At this point, the three coders independently coded the remaining articles. The full codebook is available as supplemental materials.

Risk of bias in studies

The risk of bias in individual studies was assessed with the Joanna Briggs Institute System for the Unified Management, Assessment and Review of Information (JBI Sumari, Citationn.d.). The studies were categorized as observational, randomized control trial or experiment, and qualitative. The studies were assessed along the criteria by the three independent coders.

Results

Quality assessment and description of studies

Prior to addressing the research questions, we provide a brief description of the bias/quality of study design and the demographic and study characteristics of the studies (N = 63) based on the JBI SUMAR coding. The average score of methodology quality was 7.00 (SD = 1.84). Just over 20% had a rating of five or below with 56% having a score of seven or higher. Based on these data, all studies were retained in the sample and details are located in the supplementary appendix along with the coded data for the research questions.

Nearly half of the studies focused on African American samples () with another quarter for Asian American samples; of the other studies ten were focused on Latinx samples, three were multi-ethnic and two were Indigenous samples (American Indian or Native Hawaiian). Three quarters of the studies included both male and female participants in the sample with a fifth focused only on women. Nearly 60% of the studies were full experimental studies including randomized control trials. Nearly 60% of the studies involved a communication campaign the remainder were life style or behavioral interventions (a few studies included aspects of both). There were a range of health topics addressed in the studies with non-communicable diseases such as heart disease and diabetes accounting for nearly a third and cancer accounting for a quarter of the studies. The remainder of this section is organized around the three research questions.

Table 2. Coded sample demographic and study characteristics (N = 63).

Forms of cultural tailoring

The first research question explored the forms of cultural-tailoring process and content present in the studies. Four aspects were assessed: self-definition as targeted vs. tailored, expert assessment as targeted vs. tailored, use of formative research, and community engagement processes (the elements described above in the CTP framework). Nearly 86% of all studies self-defined as cultural tailoring with only 11% as targeting and 3% as neither. However, the coding revealed only 25% were tailored studies with 31% including both tailoring and targeting elements and the remainder as cultural targeted studies (). Thus, the majority of the studies in this sample involved cultural targeting of messages. Just over half of the studies reported using formative research to support the tailoring or targeting of the messages in the intervention.

Table 3. Self-defined vs. coded tailoring and targeting of messages.

The type of community engagement largely favored lower levels of engagement such as no engagement, outreach, and consultation (combined 73%), whereas involvement and participatory approaches were only used in slightly more than a quarter of the studies. provides the percentage of studies exhibiting various aspects of process and content.

Table 4. Process and forms of cultural tailoring: all studies and studies separated by coded tailoring, targeting, or studies using both.

The most frequent form of cultural tailoring of content was the feature of design with three-quarters of studies using this element. Deeper-level elements evidenced in more than a third of studies included elements of cultural identity (49%), language system (40%), and barriers (37%). Cultural values were the focus of messages in just over a quarter of the studies.

Definitions of culture

The second research question explored the definitions of culture described within the studies. Only one included study provided a direct definition of culture; Hinderer and Lee (Citation2019) defined culture as a system of shared behaviors, beliefs, customs, and other elements that are used to make sense of the world and are transferred to other generations. Many of the studies used ethnicity or race as a proxy for culture; ethnicity or race was used to define a “cultural” group. Implicit within the approaches that use race or ethnicity as a cultural category is the culture is something shared among a group of people that helps them cope and make sense of the world (Hinderer & Lee, Citation2019).

Explanations of cultural tailoring

The third research question asked: “What are the (theoretical) explanations offered for the effects of cultural tailoring and targeting?” Twenty-two different studies did not describe using a specific theory or model explicitly and provided no direct theoretical explanation for how and why they tailored or targeted their messages. Of the remaining 42 studies, there were a total of 24 different theories or models used to develop the communication campaign and/or life style intervention. displays the eight theories that were used by at least two different studies. The most popular theory in studies that reported using a theory was the social cognitive theory with a third of those studies using it as a framework for intervention design. The transtheoretical model and health belief model were also reasonably popular with about a fifth of studies using these approaches. Social cognitive theory and the transtheoretical model were used in conjunction by six different studies. For example, Rosas et al. (Citation2020) used both theories to develop and enhanced Diabetes Prevention Program for Indigenous adults in an urban setting.

Table 5. Theories for cultural tailoring or targeting of messages within the interventions.

The theories were generally applied to behavior change in the target audience rather than specifically on the development of message content. The theories were never used as explanations for why there is a need to culturally tailor or target messages or how and why to do it. In fact, the majority of the 24 theories focus on methods for changing attitudes, behaviors, or knowledge related to specific health outcome rather than on why a culturally tailored message is more effective than one that is not. There are a few direct exceptions. The studies using community-based participatory research principles focused on making health messages and interventions culturally centered and relevant for target audiences by engaging directly with the audience (e.g., Nicolaidis et al., Citation2013). Similarly, the PRECEDE-PROCEED Model emphasizes meeting the needs of a specific target audience; hence, it focuses on matching messages to needs and cultural values (e.g., Ukoli et al., Citation2013). Studies using the surface structure-deep structure model of culture argue that addressing cultural values and beliefs is more effective than limiting to surface characteristics such as phenotype, food and other directly visible elements of culture (e.g., Gitlin et al., Citation2013). Finally, Kreuter et al. (Citation2003) approach was used to match values, beliefs and behaviors of a cultural group (e.g., de Dios et al., Citation2019).

Discussion

This systematic literature review was designed to address key questions in the cultural tailoring and targeting literature with an eye to building theory in this area of research. Unlike prior summative reviews, which were intentionally limited based on health condition and racial or ethnic group of focus, this study looked across health issues and populations with the hope of drawing some broad conclusions about the nature of cultural tailoring and targeting processes and content. The analysis shows several key things about the nature of studies in our sample and allows for some theorizing about how the elements of content, particularly, might shape message response. Further, it provides some evidence for the utility of the CTP/CTC framework as a way to analyze culturally tailored content and perhaps shape message design experiments.

Culturally tailored process and content

The analysis shows that in terms of the processes associated with creating culturally targeted and tailored messages, most of the studies in this sample used outreach approaches to the development of the intervention content. That is, top-down or expert-driven approaches with minimal community input or participation were most commonly evidenced in the sample. A smaller but not insignificant percentage of studies described consultation or participatory processes to develop the intervention content. Consultation approaches, by definition, involve some mechanism for bringing community member data, voices, or input into the process of intervention design and may contribute to the type of messages used in a campaign. For example, Nicolaidis et al. (Citation2013) used a university–community partnership to tailor messages for African American community members with depression. They took an evidence-based depression progam and integrated specifically crafted messages for African American patients and communities. Some research suggests that interventions with greater community input are more effective relative to those with less input (O’Mara-Eves et al., Citation2015) in part, because they foster a sense of engagement in the campaign and shape beliefs about the organizations or people involved in the process. This may or may not be the case for culturally tailored messages specifically; indeed, because tailoring allows for input from individual message recipients to shape content, community-engaged approaches may not be necessary for message success. Depending on the people who engage in the process, idiosyncratic voices may not be heard in typical participatory processes. Gathering data through digital surveys or trace data may be sufficient for designing tailored messages to be effective. Future studies can examine the issue of which is most effective through meta-analysis or field experiments.

The content of the messages most often described in the studies we reviewed were elements of the message design or language system. That is, many of the studies used pictures, headings, or other visual elements thought to be culturally relevant and were designed or conducted in the native language of participants. The design elements typically involved providing images of people or sources of messages who were similar in race or ethnicity to the intended recipients. Although not stated specifically as goals of the interventions we reviewed, using this type of design element could function to do several things based on findings from studies not in our review including draw attention to message content or other message elements (Kawakami et al., Citation2021), improve recall of the message elements (Brown et al., Citation2017), influence message recepients’ sense of similarity with or liking for the people portrayed in the messages or perhaps result in more favorable evaluations of the message content (Bailenson et al., Citation2008). Ultimately, each of these constructs (attention and message evaluation) can function as mediators of the message-attitude (or message-behaviors) relationship and can be tested experimentally to draw causal claims about their effects on other downstream outcomes such as attitudes or behaviors. For example, future experimental studies could use virtual message environments to expose people to messages containing each of the cultural tailoring design elements to test for attentional and recall outcomes.

In the literature, we reviewed using the native or preferred language system of the intended recipients in a tailored or targeted message that is taken as axiomatic as a way to enhance message comprehension. That is, messages received in one's own language are likely to be better understood than those that are not. However, there are other functions of matching language systems, including ease of message processing, sense of connection to or identification with the source of the message, and other outcomes predicted by communication accomodation theory (Soliz & Giles, Citation2014). Yet, providing interventions in the native language of recipients might be considered a necessary but not sufficient part of culturally tailoring of content. That is, it is likely to improve, but not ensure, message comprehension; translation or interpretation of messages does not account for cultural meanings or values that may hinder convergence, comprehension and response (Dysart-Gayle, Citation2005).

Addressing the so-called “deep elements” of culture (values, identity) may be a more effective way to improve message outcomes (Huang & Shen, Citation2016). Nearly half of our studies specifically addressed issues of cultural identity in the content of the campaign or intervention. For example, Migneualt et al. (Citation2012) used formative data to identify issues that were “mostly a black thing” or “mostly a white thing” (p. 64) and then highlighted those issues in a targeted phone intervention to promote physical activity, diet quality and medication adherence among a sample of African-Americans with hypertension. Specifically, mentioning elements of cultural identity in messages may function to draw attention to the message, make social and cultural identities more salient while processing the message or enhance a sense of similarity with message sources or organizations. About a quarter of the studies reported targeting or tailoring of intervention content based on deep cultural values; for example, Latino values related to respect, social relationships and family (de Dios et al., Citation2019) or Native Hawaiian spiritual beliefs (Mokuau et al., Citation2012).

There were a number of the CTC elements that were addressed infrequently in interventions and campaigns in our sample, despite broader support for these elements being important for message response in the persuasion or intercultural literature. For example, a few studies we reviewed specifically addressed issues of cultural tailoring or targeting based on communication style, specific appeal types likely to be effective based on cultural values, or calls to action. We coded for these elements because prior work in intercultural communication provides evidence they might be important for message response; for example, research has demonstrated cultural differences in preferences for direct vs. indirect communication style (e.g., Park et al., Citation2012) and for cultural differences in response to social norms appeals (R. W. Liu et al., Citation2022).

Tailoring or targeting on the communication style and deep values elements can be accomplished much like tailoring on design elements. The research on high-low context communication preferences provides an example case. Individual preferences for high-low context can be measured, messages can be designed that are culturally congruent with the target’s preferences, and then tested. In a message targeting study, R. Liu and Lapinski (Citation2019) found that people who reported as more high relative to low context were more responsive to explicit as opposed to implicit messages about social norms. Experimental studies could be designed to test each of the cultural tailoring elements and determine their effects on message processing and response.

Consistent with other reviews (Torres-Ruiz et al., Citation2018), our fundings show many studies used multiple strategies for cultural targeting or tailoring. For example, Islam et al. (Citation2013) used multiple elements to culturally target the content of their intervention, a community-based participatory research designed program for diabetes prevention and healthy lifestyle promotion for Korean Americans living in New York City including design elements such as photos of typical Korean foods and “incorporation of culturally appropriate images” (p. 1033). It also included culturally tailored use of language; the intervention was implemented by English and Korean-speaking community health workers, and deep cultural values elements (discussion of Korean cultural expectations for food consumption and eating with others, guilt associated with family members) and others. Using multiple form of cultural tailoring of content makes good sense practically because in campaigns it is common to try to make the messages as effective as possible. But, doing so makes it hard to determine which elements of an intervention or message are responsible for impacting recipients and as such difficult to isolate and theorize the effects of individual elements. Doing so is best done experimentally, where individual message elements can be isolated and tested as in work by Lucas and colleagues on targeting experiments addressing historical inequities in the health care system (e.g., Lucas et al., Citation2021).

Theorizing cultural tailoring: Implications for the CTP/CTC framework

In terms of the formal theories or models used in studies of cultural targeting and tailoring, several key points can be highlighted. First, it is clear that theory is being used in many studies of cultural tailoring and targeting; the majority the studies mentioned a behavioral theory or sometimes two theories in the description of the intervention; most commonly, social cognitive theory, the transtheoretical model, and the health belief model (e.g., Rosas et al., Citation2020). Theory-based intervention design is a fundamental part of effective communication campaigns because it can inform formative data collection, design of messages, and help identify potential intervention outcomes. Yet, a deeper dive into the ways in which the theories were used in the studies in our sample paints a less rosy picture of the literature. Of those studies that used theory, most did not explicitly state how the theory was used, did not link the theories to intervention processes or content, or used the theory simply as a framing for the study activities. Furthermore, none of the studies used theories of message design, culture, health and culture, intercultural communication, or cultural psychology that might help explain the most effective processes or content of cultural tailoring. We believe that moving beyond common behavioral theories such as social cognitive theory and the health belief model could further information effective cultural tailoring and targeting of messages.

Those studies that did use theory to design the intervention content provide a glimpse into a promising approach to cultural tailoring and targeting. That is, several of the studies in our sample were based on the idea that theory can help identify key cultural elements that are important for a sample and messages can be designed to match or be congruent with those cultural elements. Indeed, this is an assumption of the CTP/CTC framework: that theory is used to identify key elements to be studied through formative data collection or community engagement, and then messages are designed to address those core elements. It is the congruency between the characteristics of people and the message elements that should result in the most effective messages. In short, the use of theory in health communication campaign and intervention design and in cultural tailoring and targeting more specifically should contribute to better intervention design and stronger effects; future research can help determine whether this is the case.

Not trivial is our finding that there is no agreement on the terms “targeting” and “tailoring” despite very clear definitions of these things being put forth in early research on these topics (e.g., Kreuter & Skinner, Citation2000; Kreuter et al., Citation2003). It is clear that there is little agreement on the use of these terms. This is problematic because it makes summarizing the literature difficult and it is conceptually confusing. It is a problem that is not likely to be easily solved but one that future research will need to keep an eye on as studies are summarized or when drawing conclusions from studies. We recommend using the distinct definitions we provide in this paper which were derived from the literature and taking care with this issue; the term culturally adapted messages can be used for parsimony when covering both targeting and tailoring.

These data show that few of the studies, despite centering culture, explicitly defined “culture” and often used race, ethnicity, or nationality as a proxy for cultural group and only sometimes asked the people who took part in the study or intervention about the groups with which they most closely identify. Grouping people based on demographic characteristics like race or ethnicity may function as a starting point for learning more about potential intervention participants, but formative research or some form of bi-directional community participation could be implemented to identify shared values and practices (cultural characteristics). Or, survey items may be used to specifically asked to identify the group or groups with which people identify most closely to further elaborate demographic differences and add meaning to social categories in order to ultimately theorize differences.

In previous systematic reviews, it is not clear whether cultural tailoring improves message effects because of the fact that cultural targeting and tailoring are not always treated distinctly and the actual message features are rarely described or isolated. Meta-analyses, typically of cultural targeting rather than tailoring, point to the use of deep-level cultural values in messages as more impactful than varying design features or other surface-level elements in messages but fail to carefully examine message content or extract the unique effects for each strategy (e.g., Huang & Shen, Citation2016). This may be due, in part, to the lack of an overarching framework for cultural tailoring of messages and to the complexity of targeting or tailoring on single elements. The proposed CTP/CTC framework in this review offers clear content and process elements that can be linked to effects in culturally tailored or targeted messages and our review provides evidence of these processes and content in the literature.

Such evidence becomes important for public health and health communication practitioners. A basic value in designing campaigns and interventions is to ensure a fit of message to the audience. The process of designing messages to fit the audience is cumbersome with multiple choices considered. Further, theorizing and research on cultural tailoring and targeting can help to limit the key message features (whether in isolation or as a collection) that should be considered and thus save resources in the tailoring/targeting process. In this review, we have begun to theorize the effects of cultural tailoring elements and identify empirical literature and theories that might explain these effects; future research can expand this theorizing and isolate the effects of particular message elements.

Limitations

We were limited in our analysis by what was reported in the journal articles in our sample. As a rule, the literature we reviewed was very short on detailed descriptions of the processes and content of the study messages. In some cases, there are likely processes and content elements left out of the journal articles and so were not considered in this review. In addition, our article search criteria and article screening process may have inadvertently missed studies which would be relevant for the present study and our findings should be considered with that caveat in mind. For example, work by Lucas et al. in public health (Citation2016, Citation2018) came to our attention after the data gathering process was completed; these studies examine both cultural tailoring and targeting of content with samples of African-American men. Research could consider validation of algorithms for content screening to be sure they are adequately capturing the full corpus of studies. Further, our review did not directly consider the relationship of the process and content with various effects. The challenge of using a broad set of health conditions means is that there are a variety of potential health outcomes for consideration. Future research can consider these outcomes and how best to test the impact of culturally tailored and culturally targeted message elements.

Conclusion

This systematic review provided a comprehensive examination of the process and content features of culturally tailored and culturally targeted messages. We identified that most studies in the area use cultural targeting even when authors label the studies as culturally tailored. Further, most studies used an outreach approach in the process, often using design or language as elements of culturally tailored content, and did not use theory to guide the cultural tailoring/targeting of messages. The proposed cultural tailoring process/content framework helps to identify key elements and begin to describe their effects; it is our hope that this framework can function heuristically to promote further theorizing about cultural tailoring and targeting of messages.

Lapinski et al Supplementary Appendix A Final to HC2024.docx

Download MS Word (29.3 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Maddie Haar, Ping Ann Oung, Sarah Hipple, Ireland Ingram for their help with data capture and coding and to HyungRo Yoon for editing assistance.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

A full listing of the included studies is available at https://osf.io/hjxyb/?view_only=932b1dd36ba346fba5e9218c3f4656b2; full data set available upon request.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2024.2369340.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. We reject classifying people based on characteristics like race or ethnicity, biological sex, or socio-economic status as a way to determine “culture.” Although these categories are useful for an initial understanding of groupings of people, it is identification of shared meanings, values, behaviors, and attitudes that are fundamental for understanding communication processes. None-the-less, these categories are used in the literature on cultural tailoring and we include them when appropriate.

2. The use of the words process and dynamics here is intentional and consistent with basic theory of intercultural communication acknowledging the changing nature of culture over time.

3. Torres-Ruiz et al. (Citation2018) who base their work on Kreuter et al. (Citation2003) use the word “tailoring” for what Kreuter et al. (Citation2003) call targeting (p. 3). We will use the word targeting to represent the focus of the Torres-Ruiz et al. (Citation2018) paper in order to be consistent with the conceptualizations used in this manuscript. This is a problem throughout the literature which we will note when possible.

4. The term “targeting” was included because of our initial observation of the use of tailoring and targeting interchangeably in the literature.

5. A full listing of the included studies is available at: https://bit.ly/4dUXRzX; full data set available upon request.

References

- Adams, E. J., Cavill, N., & Sherar, L. B. (2017). Evaluation of the implementation of an intervention to improve the street environment and promote walking for transport in deprived neighbourhoods. BMC Public Health, 17(1), 655. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4637-5

- Bailenson, J. N., Iyengar, S., Yee, N., & Collins, N. A. (2008). Facial similarity between voters and candidates causes influence. Public Opinion Quarterly, 72(5), 935–961. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfn064

- Block, L. (2005). Self‐referenced fear and guilt appeals: The moderating role of self‐construal. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 35(11), 2290–2309. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2005.tb02103.x

- Brown, T. I., Uncapher, M. R., Chow, T. E., Eberhardt, J. L., Wagner, A. D., & Avenanti, A. (2017). Cognitive control, attention, and the other race effect in memory. Public Library of Science ONE, 12(3), e0173579. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0173579

- Carter, M. W., Tregear, M. L., & Lachance, C. R. (2015). Community engagement in family planning in the U.S.: A systematic review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 49(Suppl 1), S116–S123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2015.03.029

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (1997). Principles of community engagement. CDC/ATSDR Committee on Community Engagement.

- Chess, C., & Purcell, K. (1999). Public participation and the environment: Do we know what works? Environmental Science & Technology, 33(16), 2685–2692. https://doi.org/10.1021/es980500g

- CTSA Community Engagement Key Function Committee. (2011). Principles of community engagement (2nd ed.). NIH Publications.

- de Dios, M. A., Cano, M. Á., Vaughan, E. L., Childress, S. D., McNeel, M. M., Harvey, L. M., Niaura, R. S., & Shahab, L. (2019). A pilot randomized trial examining the feasibility and acceptability of a culturally tailored and adherence‐enhancing intervention for Latino smokers in the U.S. Public Library of Science ONE, 14(1), e0210323. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0210323

- de Vries, R. E., Bakker-Pieper, A., Alting Siberg, R., van Gameren, K., & Vlug, M. (2009b). The content and dimensionality of communication styles. Communication Research, 36(2), 178–206. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650208330250

- Dysart-Gayle, D. (2005). Communication models, professionalization, and the work of medical interpreters. Health Communication, 17(1), 91–103. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327027hc1701_6

- Gelfand, M. J., Raver, J. L., Nishii, L., Leslie, L. M., Lun, J., Lim, B. C., Duan, L., Almaliach, A., Ang, S., Arnadottir, J., Aycan, Z., Boehnke, K., Boski, P., Cabecinhas, R., Chan, D., Chhokar, J., D’Amato, A., Subirats Ferrer, M., Fischlmayr, I. C., … Yamaguchi, S. (2011). Differences between tight and loose cultures: A 33-nation study. Science, 332(6033), 1100–1104. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1197754

- Giles, H. (Ed.). (2016). Communication accommodation theory: Negotiating personal relationships and social identities across contexts. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781316226537

- Gitlin, L. N., Harris, L. F., McCoy, M. C., Chernett, N. L., Pizzi, L. T., Jutkowitz, E., Hess, E., & Hauck, W. W. (2013). A home-based intervention to reduce depressive symptoms and improve quality of life in older African Americans: A randomized trial. Annals of Internal Medicine, 159(4), 243–252. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-159-4-201308200-00005

- Hall, E. T. (1976). Beyond culture. Anchor Press.

- Harris, U. S. (2017). Engaging communities in environmental communication. Pacific Journalism Review, 23(1), 65–79. https://doi.org/10.24135/pjr.v23i1.211

- Hinderer, K. A., & Lee, M. C. (2019). Chinese Americans’ attitudes toward advance directives: An assessment of outcomes based on a nursing-led intervention. Applied Nursing Research, 49, 91–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnr.2019.04.003

- Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture’s consequences. Sage.

- Huang, Y., & Shen, F. (2016). Effects of cultural tailoring on persuasion in cancer communication: A meta‐analysis. Journal of Communication, 66(4), 694–715. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12243

- Islam, N. S., Zanowiak, J. M., Wyatt, L. C., Chun, K., Lee, L., Kwon, S. C., & Trinh-Shevrin, C. (2013). A randomized-controlled, pilot intervention on diabetes prevention and healthy lifestyles in the New York City Korean community. Journal of Community Health, 38(6), 1030–1041. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-013-9711-z

- Jensen, J. D., King, A. J., Carcioppolo, N., & Davis, L. (2012). Why are tailored messages more effective? A multiple mediation analysis of a breast cancer screening intervention. Journal of Communication, 62(5), 851–868. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2012.01668.x

- Joanna Briggs Institute System for the Unified Management Assessment and Review of Information (JBI Sumari). (n.d.). Retreived February 24, 2023 from https://sumari.jbi.global/

- Joo, J. Y., & Liu, M. F. (2021). Culturally tailored interventions for ethnic minorities: A scoping review. Nursing Open, 8(5), 2078–2090. https://doi.org/10.1002/nop2.733

- Joseph, R. P., Keller, C., Vega-López, S., Adams, M. A., English, R., Hollingshead, K., Hooker, S. P., Todd, M., Gaesser, G. A., & Ainsworth, B. E. (2020). A culturally relevant smartphone-delivered physical activity intervention for African American women: Development and initial usability tests of smart walk. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 8(3), e15346. https://doi.org/10.2196/15346

- Kawakami, K., Friesen, J. P., Williams, A., Vingilis-Jarameko, L., Sidhu, D. M., Rodriguez-Bailon, R., Candas, E., & Hugenberg, K. (2021). Impact of perceived interpersonal similarity on attention to the eyes of same-race and other-race faces. Cognitive Research, 6(1), 68–83. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41235-021-00336-8

- Kim, M. S., & Wilson, S. R. (1994). A cross-cultural comparison of implicit theories of requesting. Communication Monographs, 61(3), 210–235. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637759409376334

- Kleinman, A., & Benson, P. (2006). Anthropology in the clinic: The problem of cultural competency and how to fix it. PLOS Medicine, 3(10), e294. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0030294

- Kluckhohn, F., & Strodtbeck, F. (1961). Variations in value orientations. Peterson.

- Kreuter, M. W., Lukwago, S. N., Bucholtz, R. D., Clark, E. M., & Sanders-Thompson, V. (2003). Achieving cultural appropriateness in health promotion programs: Targeted and tailored approaches. Health Education & Behavior, 30(2), 133–146. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198102251021

- Kreuter, M. W., & Skinner, C. S. (2000). Tailoring: What’s in a name? Health Education Research, 15(1), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/15.1.1

- Lapinski, M. K., & Oetzel, J. G. (2022). Cultural tailoring of environmental communication interventions. In B. Takahashi, J. Metag, J. Thaker & S. E. Comfort (Eds.), International Communication Association handbook of international trends in environmental communication (pp. 248–267). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780367275204

- Liberati, A., Altman, D. G., Tetzlaff, J., Murlow, C., Gotzsche, P. D., Ioannidis, J. P. A., Clarke, M., Devereaux, P. J., Kleijnen, J., & Moher, D. (2009). The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: Explanation and elaboration. BMJ: British Medical Journal, 339, b2700. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2700

- Liu, R. W., Lapinski, M. K., Kerr, J., Zhao, J., Bum, T., & Lu, Z. (2022). Culture and social norms: Development and application of a model for culturally-contextualized communication measurement (MC3 M). Frontiers in Communication, 6, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2021.770513

- Liu, R., & Lapinski, M. K. (2019, May). Waste not, want not: The influence of injunctive social norms on food waste prevention behaviors in China and the U.S. [ Paper presentation]. International Communication Association 69th Annual Meeting, Washington DC, United States.

- Lucas, T., Hayman, L. W., Jr., Blessman, J. E., Asabigi, K., & Novak, J. M. (2016). Gain versus loss-framed messaging and colorectal cancer screening among African Americans: A preliminary examination of perceived racism and culturally targeted dual messaging. British Journal of Health Psychology, 21(2), 249–267. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjhp.12160

- Lucas, T., Manning, M., Hayman, L. W., & Blessman, J. (2018). Targeting and tailoring message-framing: The moderating effect of racial identity on receptivity to colorectal cancer screening among African–Americans. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 41(6), 747–756. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-018-9933-8

- Lucas, T., Thompson, H. S., Blessman, J., Dawadi, A., Drolet, C. E., Hirko, K. A., & Penner, L. A. (2021). Effects of culturally targeted message framing on colorectal cancer screening among African Americans. Health Psychology, 40(5), 305–315. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0001073

- Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1994). A collective fear of the collective: Implications for selves and theories of selves. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 20(5), 568–579. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167294205013

- Marshall, I. J., & Wallace, B. C. (2019). Toward systematic review automation: A practical guide to using machine learning tools in research synthesis. Systematic Reviews, 8(1), 163–172. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-019-1074-9

- McLaurin, P. (1995). An examination of the effects of culture on pro-social messages directed at African-American at risk youth. Communication Monographs, 62(4), 391–326. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637759509376365

- Migneault, J. P., Dedier, J. J., Wright, J. A., Heeren, T., Campbell, M. K., Morisky, D. E., Rudd, P., & Friedman, R. H. (2012). A culturally adapted telecommunication system to improve physical activity, diet quality, and medication adherence among hypertensive African-Americans: A randomized controlled trial. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 43(1), 62–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-011-9319-4

- Mokuau, N., Braun, K. L., & Daniggelis, E. (2012). Building family capacity for native Hawaiian women with breast cancer. Health & Social Work, 37(4), 216–224. https://doi.org/10.1093/hsw/hls033

- Nicolaidis, C., McKeever, C., & Meucci, S. (2013). A community-based wellness program to reduce depression in African Americans: Results from a pilot intervention. Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, & Action, 7(2), 145–152. https://doi.org/10.1353/cpr.2013.0017

- Nisbett, R. E. (2003). The geography of thought: How Asians and Westerners think differently—and why. Free Press.

- Nisbett, R. E., & Masuda, T. (2003). Culture and point of view. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 100(19), 11163–11170. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1934527100

- Noar, S. M., Bell, T., Kelley, D., Barker, J., & Yzer, M. (2018). Perceived message effectiveness measures in tobacco education campaigns: A systematic review. Communication Methods and Measures, 12(4), 295–313. https://doi.org/10.1080/19312458.2018.1483017

- Noar, S. M., Harrington, N. G., & Aldrich, R. S. (2009). The role of message tailoring in the development of persuasive health communication messages. Annals of the International Communication Association, 33(1), 73–133. https://doi.org/10.1080/23808985.2009.11679085

- Norton, R. W. (1983). Communicator style: Theory, applications, and measures. Sage Publications.

- O’Keefe, D. J. (2003). Message properties, mediating states, and manipulation checks: Claims, evidence, and data analysis in experimental persuasive message effects research. Communication Theory, 13(3), 251–274. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2003.tb00292.x

- O’Mara-Eves, A., Brunton, G., Oliver, S., Kavanagh, J., Jamal, F., & Thomas, J. (2015). The effectiveness of community engagement in public health interventions for disadvantaged groups: A meta-analysis. BMC Public Health, 15(1), 1352–1374. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-1352-y

- Ochoa, C. Y., Murphy, S. T., Frank, L. B., & Baezconde Garbantati, L. A. (2020). Using a culturally tailored narrative to increase cervical cancer detection among Spanish-Speaking Mexican-American women. Journal of Cancer Education, 35(4), 736–742. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-019-01521-6

- Orbe, M. (1998). Constructing co-cultural theory: An explication of culture, power, and communication. Sage.

- Park, H. S., Levine, T. R., Weber, R., Lee, H. E., Terra, L. I., Botero, I. C., Bessarabova, E., Guan, X., Shearman, S. M., & Wilson, M. S. (2012). Individual and cultural variations in direct communication style. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 36(2), 179–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2011.12.010

- Resnicow, K., Braithwaite, R., Ahluwalia, J., & Baranowski, T. (1999). Cultural sensitivity in public health: Define and demystified. Ethnicity and Disease, 9(1), 10–21. http://www.jstor.org/stable/45410142

- Rosas, L. G., Vasquez, J. J., Hedin, H. K., Qin, F. F., Lv, N., Xiao, L., Kendrick, A., Atendo, D., & Stafford, R. S. (2020). Comparing enhanced versus standard diabetes prevention program among indigenous adults in an urban setting: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 131–139. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-8250-7

- Schultz, P., & Zelezny, L. C. (2003). Reframing environmental messages to be congruent with American values. Human Ecology Review, 10, 126–136. http://ww.humanecologyreview.org/pastissues/her102/102scultzzelezny.pdf

- Soliz, J., & Giles, H. (2014). Relational and identity processes in communication: A contextual and meta-analytical review of communication accommodation theory. Annals of the International Communication Association, 38(1), 107–144. https://doi.org/10.1080/23808985.2014.11679160

- Tan, N. Q. P., & Cho, H. (2019). Cultural appropriateness in health communication: A review and a revised framework. Journal of Health Communication, 24(5), 492–502. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2019.1620382

- Ten Brug, A., Van der Putten, A. A., Penne, A., Maes, B., & Vlaskamp, C. (2016). Making a difference? A comparison between multi-sensory and regular storytelling for persons with profound intellectual and multiple disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 60(11), 1043–1053. https://doi.org/10.1111/jir.12260

- The Ad Council. (2017). Smokey’s history. Retrieved May 30, 2024, from https://smokeybear.com/en/smokeys-history/about-the-campaign

- Ting-Toomey, S. (2005). The matrix of face: An updated face-negotiation theory. In W. B. Gudykunst (Ed.), Theorizing about intercultural communication (pp. 71–92). Sage.

- Torres-Ruiz, M., Robinson-Ector, K., Attinson, D., Trotter, J., Anise, A., & Clauser, S. (2018). A portfolio analysis of culturally tailored trials to address health and healthcare disparities. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(9), 1859–1872. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15091859

- Ukoli, F. A., Patel, K., Hargreaves, M., Beard, K., Moton, P. J., Bragg, R., Beech, D., & Davis, R. (2013). A tailored prostate cancer education intervention for low-income African Americans: Impact on knowledge and screening. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 24(1), 311–331. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2013.0033

- Wallerstein, N., Duran, B., Oetzel, J. G., & Minkler, M. (Eds.). (2018). Community-based participatory research for health (3rd ed.). Jossey-Bass.

- Wilkin, H. A., & Ball-Rokeach, S. J. (2011). Hard-to-reach? Using health access status as a way to more effectively target segments of the Latino audience. Health Education Research, 26(2), 239–253. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cyq090

- Yuen, T., Park, A. N., Seifer, S. D., & Payne-Sturges, D. (2015). A systematic review of community engagement in the US environmental protection agency’s extramural research solicitations: Implications for research funders. American Journal of Public Health, 105(12), e44–e52. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2015.302811

- Zarouali, B., Dobber, T., De Pauw, G., & de Vreese, C. (2022). Using a personality-profiling algorithm to investigate political microtargeting: Assessing the persuasion effects of personality-tailored ads on social media. Communication Research, 49(8), 1066–1091. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650220961965