Abstract

The organizational environment and role delivery of support personnel have been identified as increasingly important to elite athletes’ preparation for, and performance at, pinnacle competitions. As a result, performance management has been identified as a salient research topic within the field of organizational sport psychology. The purpose of this study was to identify the performance management processes used within Olympic sport programmes and explore how these processes interact in an organizational context. Thirteen participants working in senior positions within Olympic sport organizations (e.g., national performance director) across a range of countries were interviewed. Thematic analysis identified performance management processes existing across strategic, operational, and individual levels in Olympic sport programmes. The findings also suggested that these socially dynamic processes are interrelated and influenced by the delivery of the performance leader’s role. A preliminary conceptual framework was developed to highlight these processes and illustrate their interrelated nature. Overall, the findings advance our knowledge and understanding of performance management as an organizational concept within elite sport. Practical implications are provided for sport psychology practitioners to assess and optimize how performance management processes are used within elite sport programmes.

Lay summary: While performance management of personnel in traditional workplaces has been researched heavily, there are limited studies exploring the topic in elite sport. Given the importance of the organizational context for performance and well-being in sport, we explore performance management processes within Olympic sport programmes and discuss their potential practical application.

The proposed conceptual framework (and the findings it represents) identifies the key performance management processes in Olympic sport programmes which can help practitioners evaluate current processes in place at individual, operational, and strategic levels and better understand the broader organizational context affecting athletes.

The findings may help practitioners to more optimally support those operating in senior organizational roles in sports organizations in developing effective performance management processes across their system. Specifically, the training and expertise of sport psychologists can help position them to support those implementing performance management processes at the organizational (e.g., developing codes of conduct), operational (e.g., supporting cultural change), and individual (e.g., providing an optimal balance of challenge and support) levels.

Implications for practice

There is a growing interest in how organizational psychology can be applied within the sport domain, and more specifically, how it can be utilized to gain the knowledge and understanding that facilitates the development of “optimally functioning sport organizations” (Wagstaff, Citation2019, p. 1). This discipline of psychology explores human behavior in organizations, and in doing so, combines social psychology with organizational behavior (Cascio, Citation2015). Its increasing prevalence within elite sport is perhaps best explained by the realization that sport organizations are becoming ever more complex social environments where a diverse range of personnel (e.g., national performance director, coaches, support staff) support the development, preparation, and performance of elite athletes (Arnold et al., Citation2019). Aligned with this, is the belief that sustained success in elite sport is not solely dependent on the talent of an individual athlete or group of athletes but rather how a systematic collective of stakeholders (e.g., coaches, managers, directors, support staff, administrators) can work effectively together to ensure athletes are optimally prepared to perform at major competitions (Wagstaff, Citation2019). One topic that exemplifies this collective approach to preparation and performance in elite sport is performance management.

Performance management has been identified as a salient research topic within organizational sport psychology as it is focused on how macro organizational processes influence, and are influenced by, individual behavior and group dynamics to effect the performance of individuals and teams within the organization (Molan et al., Citation2019). Furthermore, the application of performance management within elite sport has increased significance as factors such as the role delivery of coaches, the coordination of sport science and medical support, and the sport organization’s vision and culture can profoundly influence performance across multiple generations of athletes (Arnold et al., Citation2019; Feddersen et al., Citation2020; Wagstaff, Citation2019). Consequently, it is no longer sufficient for researchers and applied sport psychologists to primarily focus on the athlete or the coach-athlete relationship, they must now understand and potentially influence wider contextual/systemic factors which affect athlete performance and wellbeing. It is in this “widening of the lens” (Schinke & Stambulova, Citation2017) that performance management becomes a pertinent topic from both a research and an applied perspective.

Performance management has been defined as “a continuing process of identifying, measuring, and developing the performance of individuals and teams and aligning performance with the strategic goals of the organization” (Aguinis, Citation2013 p. 2). There is a substantial body of research examining performance management outside of the sport domain, notably in the broader organizational psychology and management literature (DeNisi & Murphy, Citation2017). In these domains, performance management involves activities that exist across individual, operational, and strategic levels of the organization (Brudan, Citation2010). Individual performance management has evolved from traditional supervisor appraisals to a practice that integrates processes such as goal setting, feedback, and training with an individual’s role delivery (DeNisi & Murphy, Citation2017). Operational performance management is primarily focused on how a department is functioning, and involves using performance measures or indicators to guide human resource management (HRM) decisions (e.g., staffing, level of supervision), which may result in improvements in efficiency or effectiveness (Brudan, Citation2010; Radnor & Barnes, Citation2007). Strategic performance management can be defined as a process that steers the organization through identification and communication of the mission, strategy, and objectives, making these measurable in order to evaluate organizational performance and inform planning (Aguinis, Citation2013). While different performance management processes exist at each of these levels, researchers have argued that performance management should be viewed as an interrelated dynamic collection of processes within the organization (DeNisi & Murphy, Citation2017), essentially a complex system whereby the objective of the whole system defines the function of each part (Schleicher et al., Citation2018). Indeed, systems theory (Katz & Kahn, 1978) may provide a theoretical lens through which to obtain an enhanced understanding of performance management processes and how they interact in elite sport. The systems perspective posits that performance management is complex and involves a potentially infinite number of elements and environmental conditions that interact to influence the functioning of the system and performance outcomes (Armstrong, Citation2019). In a review of the management literature, Schleicher et al. (Citation2018) adopted a systems-based view to explain how performance management occurs in organizations and suggested a dynamic interaction between processes (e.g., setting performance expectations, coaching, evaluation).

Encouragingly, there is an emerging body of research related to performance management in elite sport. These studies have examined key aspects of performance leadership and management centered on the role of the performance director (e.g., Fletcher & Arnold, Citation2011) and the factors which might influence this role (e.g., Arnold et al., Citation2015; Arnold et al., Citation2018). Despite this recent research, there remains limited understanding as to what the key performance management processes are within Olympic sport programmes and importantly how these processes interact with each other across different levels of the organization as described in the preceding paragraph. Furthermore, performance management itself has yet to be examined within Olympic sport as a distinct organizational construct. Traditionally, performance management and performance leadership in Olympic sport programmes have been considered as two similar and overlapping constructs (e.g., Fletcher & Arnold, Citation2011). However, despite general acceptance at an operational level that considerable overlap exists, emphasizing the similarities between performance management and leadership can be problematic conceptually given that they are theoretically distinct concepts (Kinicki et al., Citation2013). To highlight the distinction between leadership and performance management, leadership is a leader-follower interaction aimed at influencing groups of individuals to achieve a common goal in a particular social context (Day et al., Citation2014). Contrastingly, performance management is not based solely on the interactions with a leader or manager but on how the organization implements processes to synchronize the attitudes and behaviors of personnel to achieve organizational goals (DeNisi & Murphy, Citation2017; Kinicki et al., Citation2013).

A recent review on performance management across elite sport and other performance domains has supported this distinction by suggesting that leadership is a social factor that interacts with performance management processes, rather than these concepts being interchangeable (Molan et al., Citation2019). To elaborate, the effectiveness of performance management processes at strategic, operational, and individual level is influenced by the leader’s ability to disseminate an organization’s vision, coordinate group dynamics, clarify expectations, and consistently recognize good performance behaviors (Molan et al., Citation2019). However, further clarity on the interaction between performance management processes and the performance leader’s role in Olympic sport programmes is required. For example, by viewing performance management as an open system, it may help us to further understand how performance management processes interact with environmental factors and social agents in the organization such as the performance leader.

In summary, performance management is a growing area of research in elite sport. However, despite recent studies in the sports domain, there is limited understanding on the specific and distinct performance management processes that occur within Olympic sport programmes. Consequently, we propose that qualitative methods can be used to gather the beliefs and experiences of senior personnel within elite sport and can provide valuable insight to further explore this area of research. Therefore, the purpose of the current study was to identify the particular performance management processes used with individuals and teams within the elite sport context, and to explore how these processes might interact.

Method

Research paradigm and design

This study adopted a critical realism perspective to explore performance management processes within Olympic sport programmes. Critical realism proposes a stratified ontology with reality considered situational and layered into three distinct domains: the real, the actual, and the empirical (Bhaskar, Citation1979). In the real domain, events and phenomena occur because of the mechanisms that operate, such as biochemical, economic, and social structures (Bhaskar, Citation1979; Parker, Citation2014). However, in the actual domain the same events that occur may not be observed or may be interpreted differently by observers (Parker, Citation2014). Finally, the empirical domain is where observations are made and events are experienced by observers, therefore, knowledge and beliefs are socially produced (Bhaskar, Citation1979). Critical realism can provide an appropriate platform to study performance management as it recognizes that performance management occurs within a complex social system with many interacting elements and its layered view of reality can offer a nuanced explanation of how these elements work (Armstrong, Citation2019). The aim of this study was to explain the phenomenon of performance management within Olympic sport programmes by identifying the key processes that occur and how they interact. To draw out the subjective reality of participants, qualitative methods were chosen (Fletcher, Citation2017). Semi-structured interviews were used as the data collection technique as they provide a flexible approach for participants to elaborate on the meanings they attach to their experiences, thus providing the interviewer with a deeper level of understanding (Sparkes & Smith, Citation2014). Critical realism assumes that knowledge is socially produced and inherently fallible, therefore, relies on research findings being examined and expanded upon to further develop our understanding (Armstrong, Citation2019). The study’s findings and explanatory theories are presented as tentative but a potentially useful next step to understanding performance management processes within elite sport.

Participants

A combined purposive and snowball sampling strategy was utilized in this study. Purposive sampling was applied to all prospective participants as it allowed researchers to select individuals with suitable levels of knowledge of the research area (Gray, Citation2013). Specifically, in order to participate in the study, each individual was required to (1) be currently working in a senior-level position within Olympic sport and (2) have a minimum of ten years’ experience working with Olympic sport programmes. A sample of four individuals agreed to participate initially and this sample was then expanded on a ‘‘snowball’’ basis, with interviewees being asked after the interview if they knew of other individuals with significant experience on the research topic who might be willing to participate.

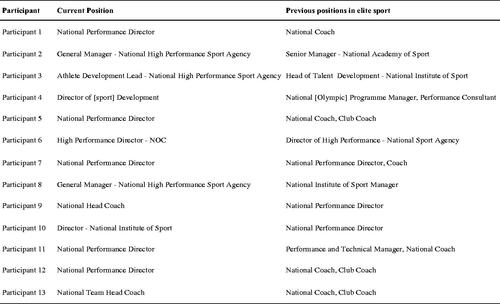

The final sample consisted of thirteen participants (12 male, 1 female, all white ethnicity) aged between 39 and 63 years old (M = 49.53, SD = 7.14). Participants’ gender and ethnicity was not explicitly asked but determined from the high-profile nature of their careers. The sample demographics were not surprising as both female and nonwhite ethnic groups continue to be greatly underrepresented in management and coaching positions in elite sport (Burton, Citation2015; de Haan & Sotiriadou, Citation2019; Rankin-Wright et al., Citation2019). All participants had at least 10 years’ working experience in Olympic sport. In addition, participants had an average of 11.92 (SD = 5.44) years working at management level within NSOs, National Institutes of Sport, National High Performance Agencies, or National Olympic Committees. Nine participants had experience specifically within the following Olympic sports: athletics, boxing, badminton, gymnastics, golf, rugby 7’s, and swimming. The four remaining participants had worked across multiple Olympic sport programmes. The participants career experience spanned ten national sport systems: Australia, New Zealand, Ireland, USA, Canada, Denmark, France, Germany, Great Britain, and Sweden. Overall, the participants were responsible for management or oversight of programmes that qualified 499 athletes and achieved a total of 93 medals at the Rio 2016 Olympic Games. The participants’ experience is briefly outlined in .

Procedure

After obtaining institutional ethical approval for the study, individuals were contacted by email and invited to participate in the study. Participants were sent a document detailing information about the study, including the purpose of the research and their ethical rights (e.g., confidentiality, anonymity, right to withdraw). Interviews were conducted between March and June 2016 in person at a suitable location or via Skype if the participant was based in a country outside a reasonable travel time. Prior to each interview, the primary researcher spent some time in conversation with each participant to build a rapport, further explain the research topic, and provide a frame of reference for the interview. The interviews were digitally recorded with a Dictaphone following agreement with all participants.

Interview guide

An interview guideFootnote1 was designed to investigate the research question and was divided into four sections. Section 1 re-iterated the participant’s ethical rights and asked them to provide informed consent. Section 2 consisted of introductory questions aimed at exploring the participant’s background. Section 3 contained a number of open-ended questions related to the research objectives which encouraged participants to elaborate on their career experiences within Olympic sport programmes (e.g., Based on your experience, what are the key aspects of managing a high performance programme? How do you ensure the different roles in the multi-disciplinary team are aligned?). Section 4 included summary questions which invited participants to discuss any other issues they felt were important to the topic. Although the interview guide was followed, the natural flow of the conversation was allowed to dictate the order of the questioning. To ensure the suitability of the interview guide, two pilot interviews were conducted with participants who were both working in the management of elite sport. Based on the pilot interviews, additional probing questions were added to the guide to encourage participants to elaborate further on their career experience.

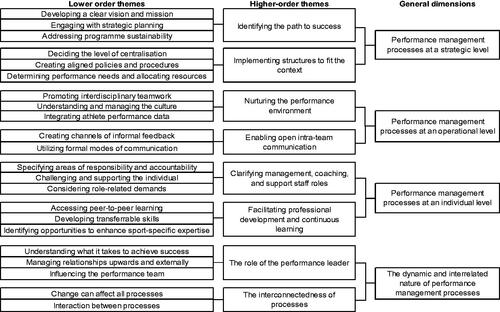

Data analysis

The interviews, which ranged from 45 to 93 min (M = 58.30 min, SD = 13.30), were transcribed verbatim. Pseudonyms were used to ensure the anonymity of the participants. The data analysis was based on Braun and Clarke (Citation2019) principles of reflexive thematic analysis, which has been used in other qualitative studies underpinned by critical realism (e.g., Brown et al., Citation2020). Management and analysis of the data was also facilitated by the NVivo data management tool. Reflexive thematic analysis is a flexible, iterative process that involves moving back and forward between stages of analysis and revisiting the raw data as often as needed to refine understandings (Braun & Clarke, Citation2019). The key stages of this process included data familiarization, open coding, searching for themes, reviewing and refining themes, defining and naming themes, before development of a final report containing a selection of data extracts. The data analysis was also characterized by a process of retroduction, which is a key feature of critical realism and involves the integration of subjective and objective knowledge (Fletcher, Citation2017). This retroductive approach initially involved inductive reasoning which enabled organic development of the lower-order and higher-order themes, however, deductive reasoning also played a role. For example, three general dimensions were informed by contemporary conceptualizations of performance management which consider processes at strategic, operational, and individual levels (e.g., Molan et al., Citation2019). Therefore, the final stages of analysis involved deductively identifying and grouping lower-order and higher-order themes that clearly resonated with these levels. The movement between subjective participant meanings and established theoretical explanations was also used to examine the causal mechanisms and contextual conditions affecting performance management in Olympic sport programmes, thus enabling a deeper understanding of the phenomenon (Fletcher, Citation2017; Sparkes & Smith, Citation2014).

Rigor and trustworthiness

Rigor is an important marker of quality and there are different approaches as to how it might be judged in qualitative research (Smith & McGannon, Citation2018). We selected a set of eight criteria drawn from the work of Tracy (Citation2010) who synthesized these criteria from the work of others (Burke, Citation2016). The criteria were: i) worthy topic, (ii) rich rigor, (iii) sincerity, (iv) credibility, (v) resonance, (vi) significant contribution, (vii) ethics, and (viii) meaningful coherence. Performance management was selected as a worthy topic and a significant contribution to literature due to its relevance to the growing field of organizational sport psychology and the study’s focus on Olympic sport programmes with the impending Olympic Games in Tokyo 2020. The criteria of rich rigor were met through gathering in-depth accounts on the research topic from credible participants with variation in their backgrounds (i.e. different roles and different countries) (Osbeck, Citation2014). Credibility was considered using two approaches, member reflections and peer triangulation. For member reflections, randomly selected participants were invited to discuss the preliminary results with the first author to see if further insight would be developed through this dialogue (Smith & McGannon, Citation2018). Through this dialogue, an additional higher-order theme (the role of the performance leader) emerged which was added to the final results. Peer triangulation was achieved through interactions between the researchers, and considering different interpretations of the data (Coulter et al., Citation2016). This process was not intended to achieve some form of independent truth but instead, in line with the critical realist perspective, generate a robust and layered understanding of the data through additional insights and dialogue (Smith & McGannon, Citation2018). For sincerity, the first author kept a reflexive diary to reflect on different interpretations of the data and consider the wider social context of the participants’ experience during the thematic development process (Nadin & Cassell, 2006). For example, how did the type of sporting environment or level of organizational resources influence the participant’s experience of performance management. Overall, the diary process enabled greater reflexivity and ultimately helped contextualize the findings. Resonance was established through the use of detailed quotations and visual figures to promote transferability of the data (Tracy, Citation2010). Ethical standards were maintained by obtaining institutional ethical approval. Finally, meaningful coherence was demonstrated by developing a conceptual framework to highlight the key findings (see ).

Results

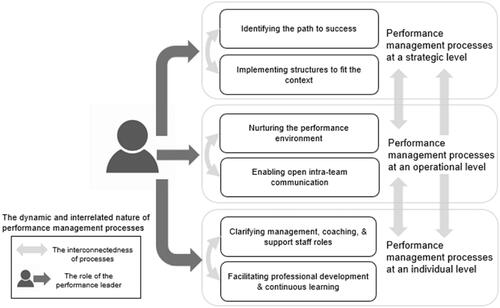

The aim of this study was to identify the performance management processes used with individuals and teams in the elite sport context and to explore how these processes might interact from a whole systems perspective. The findings from the analysis process are organized with the component parts of the system presented first as three general dimensions, performance management processes at a strategic level, performance management processes at an operational level, performance management processes at an individual level. Then, to illustrate the interaction between system components and the role of social environmental influences, a fourth dimension is presented, the dynamic and interrelated nature of performance management processes. Across these four dimensions, there are nine higher-order themes which were categorized from 24 lower-order themes (see ) and are described with representative participant quotes.

Performance management processes at a strategic level

In this general dimension, participants referred to processes that helped to formulate the overarching direction of the Olympic sport programme. The higher-order themes within this general dimension were “identifying the path to success” and “implementing structures to fit the context.” Within the higher-order theme of identifying the path to success, developing a clear vision and mission, engaging in strategic planning, and addressing programme sustainability were identified as a lower-order themes. In particular, participants described how a long-term vision and planning across multiple Olympic cycles was crucial in guiding a programme and achieving sustained systematic success, rather than isolated and infrequent success based on individual talent alone. This participant emphasized the importance of developing the vision:

so what’s the vision for the programme, I think getting that right at the beginning motivated a lot of the action within the organization…I didn’t know at the time how important the vision was to be honest, it’s great in hindsight… but by God it was the most important thing. (Participant 10)

The higher-order theme of implementing structures to fit the context referred to the organizational structure, resources, and policies that supported the strategic direction of the programme and were compatible with circumstances in the sport. In relation to the lower-order theme of deciding the level of centralization (e.g., one national performance center or regional/club-based models), participants described how this was a key decision for the NSO and depended on the level of resources available and the social dynamics in the sport. This was illustrated by some performance directors stating a preference for a centralized model for athletes and staff, whereas another performance director strongly argued against such an approach: “[centralization] won’t work in [name of sport]. It works in team sports but it doesn’t necessarily work in individual sports.” (Participant 7) Within the lower-order theme of determining performance needs and allocating resources, participants highlighted the importance of investing in enough coaching and support staff to meet the capacity of the programme, as illustrated in the following quote: “[we needed to first ask] what are the [athlete] needs and from there we started actually to employ people.” (Participant 5) Creating aligned policies and procedures was identified as a related lower-order theme for developing coherence in organizational priorities and decision making from both the perspective of internal staff and external stakeholders. Participants referred to procedures such as codes of conduct, selection policies, competition pathways, and planning processes as being essential for coherent decision making and achieving the vision for the Olympic sport programme.

Performance management processes at an operational level

This general dimension related to processes which occurred daily across the Olympic sport programme and supported how people within the programme functioned as a group. The higher-order themes within this dimension were: “nurturing the performance environment” and “enabling open intra-team communication.” The higher order theme of nurturing the performance environment referred to the process of developing the working practices and behavioral norms that aligned the support staff, coaches, and management who often worked in disparate locations. Related to this, promoting interdisciplinary teamwork was identified as a lower-order theme. Participants referred to the importance creating an aligned and collaborative approach that can offer a solution to address key issues for athletes, as this participant explained: “I think a multi-disciplinary approach is affected by key issues… on key projects you will come together with key expertise because that’s where their key focus is.” (Participant 10)

In a related lower-order theme, participants described how understanding and managing the culture within the high performance programme and aligning their behavior to this culture was crucial in being able to function effectively. However, participants also noted the importance of being able to assess if a change to the prevailing culture was needed. In particular, participants highlighted the role of the performance director as being crucial in recognizing and delivering on the need for change. To illustrate, one participant described how a performance director initiated a culture change leading to a more accountable performance-focused environment.

[the performance director] instituted policies in the sport … and a thing called “the Code”, it doesn’t matter if you’re a sixteen-year-old rookie or a sixty-two-year-old master team director, you’re expected to follow “the Code” and you sign a document … So that’s when the cultural shift happened. (Participant 6)

Reinforcing the idea of accountability within the performance environment, integrating athlete performance data was identified as a lower-order theme. Participants described how performance data could be utilized to set clear standards for the programme and inform evidence-based conversations between management, coaches and support staff. Specifically, participants indicated it was vital to measure against world class benchmarks. This involved comparing athlete performances with those of competitor nations in order to identify performance gaps and potential for the Olympic Games. One performance director explained how he utilized performance data: “I can sit with any athlete or any coach and there’s no BS [b**l s**t]. No matter what event you are in at least I have an idea of what it takes, where you should be.” (Participant 7) This practice was particularly useful in time-based sports (e.g., athletics, swimming) for helping performance directors and coaches identify and monitor performance targets, as this participant explained:

We might suggest that in [name of sport] in 2020 if you want to win the [name of event] you’re going to have to go under 45 s. So we’ve got a projection on world’s best … so we track back off world’s best to go one year, two years, three years, four years, five, six, seven, and then eight years away, [to analyze] what parameters we need to be in to suggest that an athlete is tracking. (Participant 3)

The higher-order theme of enabling open intra-team communication related to dynamic processes which facilitated the flow of key messages and feedback within the group. Within the lower-order theme of creating channels of informal feedback, participants highlighted how such communication facilitated an adaptive performance environment, as this head coach described:

… between me and my performance scientist … we talk daily about different things and he's had input into some of our planning … at one of the competitions he said he felt like I had been working the [athletes] maybe just a bit too hard and he came up with a different way of training … you can only do that with someone who's working with you regularly. (Participant 9)

In addition, utilizing formal modes of communication was identified as a related lower-order theme. For example, this participant suggested how scheduled review meetings occurred half yearly, and included a range of stakeholders: “…we have it two times a year, December and July, the player reviews, and it involves the high performance working group which is me, the national coach, the CEO, the pathway coach and the player.” (Participant 1)

Performance management processes at an individual level

This dimension represented processes that supported personnel working within Olympic sport programmes (e.g., coaches, support staff) to deliver in their roles. The higher-order themes under this general dimension were: “clarifying management, coaching, and support staff roles” and “facilitating professional development and continuous learning.” In relation to the higher-order theme of clarifying management, coaching, and support staff roles, specifying areas of responsibility and accountability was identified as a lower-order theme. Notably, only two participants described how individual roles were clarified in a formalized way by the NSO (e.g., in writing with a formal review process). Challenging and supporting the individual was identified as a related lower-order theme. Participants suggested appropriate levels of challenge and support was important for maintaining high standards of role delivery. Considering role-related demands was a further lower-order theme identified. While the challenging nature of Olympic sport offered authentic opportunities for personal growth, many participants advised that it was important to consider the demands of the job. One participant commented that some sports “put the pressure on people to do too many things and become a jack of all trades.” (Participant 9) While another performance director suggested that excessive demands will ultimately take their toll: “there’s a point where you work for seven years, in my case, and you come to a point where you are most probably done mentally and physically.” (Participant 12) To manage these demands, several participants emphasized that performance directors require ongoing advice and advocative support from key internal (e.g., Chief Executive Officer [CEO]) and external stakeholders (e.g., national institute of sport staff) in order to ensure longevity and impact in the role.

Facilitating professional development and continuous learning was another higher-order theme considered vital to ensure effective role delivery within respective areas of expertise (e.g., management, coaching, sport science). Within the lower-order theme of accessing peer-to-peer learning, participants emphasized the value of knowledge transfer with colleagues in similar roles inside or outside their sport, as this participant suggested: “If you are an individual Olympic sport, you can learn heaps from others. So, if you are in sailing, you can learn a huge amount from athletics. If you are in rowing, you can learn from cycling.” (Participant 2) Identifying opportunities to enhance sport-specific expertise was a further closely linked lower-order theme. Participants highlighted the importance of coaches and sport science practitioners continually developing their technical skills and knowledge through events organized by international federations or national institutes of sport. However, some participants stressed that these skills should be distinct from general coach education and applied on-the-job to have real value. Developing transferrable skills was also identified as a lower-order theme. Participants emphasized that individuals in senior roles within the performance environment such as performance directors and head coaches need to develop non-technical skills (e.g., strategic planning, emotional intelligence, change management) through both formal leadership programmes and on-the-job mentoring, as this participant explained: “coaches tend to come from a technical background not a broader leadership background. So we provide performance planning support and over time the coaches are getting more of those leadership skills, more of those planning skills.” (Participant 2)

The dynamic and interrelated nature of performance management processes

This dimension illustrates a systems approach by highlighting the dynamic and interrelated nature of the components of the performance management system. Specifically, how performance management processes might interact, how specific processes may change over time and how they can be influenced by a key stakeholder (i.e., performance leader). The higher-order themes were: “the role of the performance leader” and “the interconnectedness of processes.” Regarding the role of the performance leader, participants indicated that the performance director (or equivalent de-facto head of programme) was important for ensuring performance management processes were coordinated and adaptive to the context. Thus, the performance leader influenced at all levels of the performance management system. This is evident through the lower order themes at different levels. For example, understanding what it takes to achieve success was identified as a lower-order theme for the role of the performance leader, with participants considering this vital for communicating the vision and mission of the programme to staff, and thus connecting them to the strategic direction of the programme. Influencing the performance team was a further lower-order theme related to the performance leader’s role. Participants discussed how the performance leader could affect managers, coaches, and support staff by promoting interdisciplinary teamwork, providing meaningful feedback and connecting these operational level processes with individual level processes such as challenging and supporting staff members. Finally, many participants referred to the lower-order theme of managing relationships upwards (to the CEO and Board) and externally (to funding agencies and national institutes of sport) which enabled the performance leader “the power to do his job,” (Participant 6) and thus influence the performance management system at the various levels.

The final higher-order theme was the interconnectedness of performance management processes which referred to how processes could change over time and the interaction between processes across strategic, operational, and individual levels. Perhaps unsurprisingly, how change can affect all processes was identified as a lower-order theme. This dynamism was evident as organizational decisions and changes at a strategic level (e.g., changes to the vison and mission or how resources were allocated) could affect how a programme functioned as this participant suggested: “you could only make one policy change or shift and the whole system can tumble down.” (Participant 8) It is further illustrated through the change or the potential for change within performance management processes. For example, at an operational level, it was evident in how communication in the performance team changed over time as highlighted by this quote, “two years before the Olympics I was more and more involved. I met with our group of coaches and sport staff every Monday.” (Participant 5) The lower-order theme of interaction between processes can be illustrated by demonstrating connections between particular themes. At a strategic level, there might be concerns for programme sustainability if key staff left the organization as this participant stated, “but if we all walked away would the systems be there to guarantee success? I’m not sure yet,” (Participant 13) and how this could lead to the theme of determining performance needs and allocating resources, whereby the first step to address this issue of sustainability might be “to identify the areas of competence and knowledge we need, (then) we more or less headhunted the coaches that we knew and thought had the competence.” (Participant 5) The final step is how this interacts with the individual level and more specifically, the theme of specifying areas of responsibility and accountability as when you have the right people: “you want to make sure they get the right employment agreements, they have the right review processes, they have clear objectives so you’re treating them as you should, like a proper employee,” (Participant 8) as one participant stated. A further example of the interaction across levels can be seen in developing sport specific expertise (individual level) through on the job training as suggested by some participants. This form of training is likely to be fostered by promoting and encouraging interdisciplinary teamwork (operational level), as illustrated by this participant:

There are little groups, cohorts … . It’s important that they are closely aligned so that they can have greater effect by plugging into other disciplines … S & C, medicine and nutrition are a very close working cell … Psychology and nutrition, psychology to support nutrition, less so nutrition to support psychology … working very, very closely together alongside the coach. (Participant 10)

Based on the general dimensions and associated themes, a preliminary conceptual framework was developed representing a systems perspective of performance management processes (see ). Conceptual frameworks have previously been developed to represent organizational phenomenon in elite sport based on exploratory empirical studies (e.g., Fletcher et al., Citation2012). The conceptual framework in this study illustrates a dynamic and interrelated system of performance management processes across strategic, operational, and individual levels in Olympic sport programmes.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to identify the performance management processes used in an elite sport context and to explore how these processes might interact, using semi-structured interviews with key personnel. A performance management system with component parts across strategic, operational, and individual levels were identified, and the interrelated nature of these processes was represented in the development of a conceptual framework. The findings in this study add to the current literature by illustrating how performance management in elite sport can be viewed as a whole system with a collection of dynamic processes that interact across strategic, operational, and individual levels.

Identifying the path to success through a clear vision and strategic goals and implementing structures to fit the context were identified as key aspects of performance management. While these processes were typically initiated by the performance director, the process of negotiating a vision and a structure that aligns with the perspective of the performance director and the beliefs of the wider sport organization was not straightforward. Indeed, previous research has suggested that establishing and implementing the performance director's vision is a highly contested process often involving multiple stakeholders (e.g., board, chief executive officer) with legitimate authority but little expertise in elite sport (Collins & Cruickshank, Citation2012). Thus, within an elite sport context, the level of power and counter-power that exists in the relationship between the performance director and other stakeholders must be considered, as it may explain the ability of the performance director to exert influence and gain support for their espoused vision and strategic goals for the programme (cf. Arnold et al., Citation2018; Molan et al., Citation2016). When considering how an applied sport psychologist could influence performance management processes at the strategic level, it may be to “coach” or support the performance leader to actively manage these stakeholder relationships so as to ensure the programme can run as coherently and effectively as possible (Collins & Cruickshank, Citation2012).

The findings also highlighted at an operational level that nurturing the performance environment was a crucial component of effective performance management. In particular, being able to understand the behavioral norms and espoused values of the performance team, and initiate cultural change if required. Indeed, this reinforces the views of Cruickshank et al. (Citation2014) who emphasized the significance of the primary change agent gaining an understanding of the context and then managing and adapting the social setting as needed to ensure progress toward the desired vision. Moreover, enabling open intra-team communication, using formal and informal methods, was identified as an important operational process for planning and adapting daily practice within the programme. Whilst this finding aligns with previous research which suggests the importance of intra-team communication for role delivery and high-functioning performance teams in elite sport (e.g., Ekstrand et al., Citation2019), it also illuminates for the first time, how both informal and formal types of communication should be utilized with personnel in combination and adapted based on the proximity to pinnacle competitions. An applied sport psychologist might influence performance management processes at an operational level through working with the wider performance team to clarify and strengthen channels of communication. By doing so, this can enhance the group dynamics of the team who are tasked with delivering the high performance programme (Martin et al., Citation2017).

Moving from operational to individual performance management, the present findings suggest that clarifying management, coaching, and support staff roles was central to effective performance management in Olympic sport programmes. Indeed, clearly defined staff roles have been suggested as vital to enhancing individual productivity, interpersonal relationships, and overall team functioning within elite sport (Martin et al., Citation2017). Moreover, considerable evidence outside the sport domain suggests that individuals who can develop clarity within their role and optimize the level of job demands can enhance their performance (Bakker & Demerouti, Citation2017). Professional development and continuous learning was also a prominent higher-order theme in the current findings with knowledge transfer between similar sports being emphasized and personal growth encouraged through the learning and application of new skills on-the-job. Job crafting is a framework with potential to facilitate continuous learning (Van Wingerden et al., Citation2017). Research has suggested how teachers who are in a demanding work environment and may not have control over significant portions of their workload, can use and increase their personal capabilities to deal with their job demands (Van Wingerden et al., Citation2013). Finally, an applied practitioner could support the job design process within the performance team whereby core roles are identified, and the responsibilities of these roles are clearly defined. Furthermore, an applied practitioner might work with performance staff using strategies such as job crafting to empower these individuals to shape their own professional development, leverage on-the-job experiential learning, and enhance effectiveness in their roles.

In a departure from previous studies, the current findings position performance management and leadership as being distinct but connected concepts within Olympic sport programmes. The results indicate that the performance leader’s role has a significant impact on how performance management processes are delivered across strategic (e.g., identifying the path to success), operational (e.g., nurturing the performance environment), and individual (e.g., clarifying management, coaching and support staff roles) levels. However, we argue that these processes are not solely influenced by the performance leader, and that the performance leader’s influence on these processes may change over time (Feddersen et al., Citation2020). For example, the board can have a considerable influence on how performance management processes are delivered through the strategic direction set for the organization which can feed down into the types of roles and range of responsibilities that coaches, and support staff might have. Furthermore, an external funding agency through its provision of investment can influence a range of performance management processes including decisions around the level of centralization, while athletes can also influence processes such as role-related demands. Thus, while the performance leader has a considerable impact on performance management processes, these processes are not solely leader influenced.

Several of the processes identified in this study have previously been researched individually in an elite sport context, for example, establishing and communicating a vision for the programme (e.g., Collins & Cruickshank, Citation2012), interdisciplinary teamwork (e.g., McCalla & Fitzpatrick, Citation2016), and peer-to-peer learning (e.g., Rynne & Mallett, Citation2014). However, a unique contribution of this study is the application of a “whole system” approach to performance management as demonstrated in the development of a conceptual framework which illustrates the interrelated nature of these processes. For example, we demonstrated in the results section how addressing programme sustainability, determining performance needs and allocating resources, and specifying areas of responsibility and accountability could all be connected. We also highlighted how the processes of promoting interdisciplinary teamwork (as part of nurturing the performance environment; operational level) and developing sport specific expertise (part of clarifying management, coaching, and support staff roles; individual level) might be implemented synergistically to have a greater effect on the development of personnel. In line with systems theory, performance management processes may be best considered working in conjunction with each other, not in isolation as it is the level of congruence or fit between the system components that dictates the effectiveness of the system (Schleicher et al., Citation2018). This systems perspective emphasizes a much more complex and dynamic view of performance management than has been proposed in the sport related literature to date. This may help researchers and applied sport psychologists to better understand performance management in elite sport.

The findings can be further understood through the multiple levels of reality within critical realism. At the empirical level, the findings reveal a range of performance management processes as collectively observed and experienced by the participants throughout their career in elite sport. At the actual level, the processes exist and affect each other whether experienced by certain individuals or not. For example, a coach may not observe strategic processes (e.g., developing clear vision and mission, determining performance needs and allocating resources), however, these processes do occur and influence operational (e.g., understanding and managing the culture) and individual processes (e.g., specifying areas of responsibility and accountability). At the real level, retroductive analysis suggested two key causal mechanisms that shape performance management as an organizational phenomenon within Olympic sport programmes. First, the delivery of strategic, operational, and individual level processes, which are not solely dependent on the influence of the performance leader but rely on the collective functioning of personnel within the organization. Second, the interconnectedness of performance management processes and how these processes interact with each other in Olympic sport programme. While these causal mechanisms are identified at the real level, they exist within the phenomenon at the empirical and actual level as all levels are ultimately part of the same reality (Fletcher, Citation2017).

This research study was explorative in nature and had strengths and limitations. A key strength of the study was the vast experience of the participants who offered a cross-country perspective and represented a relatively small population of people with expertise working in the higher echelons of Olympic sport. A further strength was the robust nature of the thematic analysis, which, consistent with a critical realist orientation, focused on reporting an assumed social reality evident in the data (Braun & Clarke, Citation2019). In terms of limitations, it could be argued that the participants’ perspectives, gathered from a sample group of thirteen, was restricted to people only working in senior management roles. While the sampling criteria was appropriate for the aim of this study, including the views of additional personnel working at other levels (e.g., sport science and medical staff) in future enquiries may reveal further insights on performance management processes within Olympic sport programmes. A further potential limitation is that the sample could be described as largely homogeneous in terms of gender and ethnicity (i.e. majority male from white ethnic sub-groups). While the underrepresentation of female participants in this study is consistent with their overall representation in elite sport (Burton, Citation2015), future research should explore how gender and ethnicity may impact an individual’s approach to, and experience of, performance management in elite sport. Continuing with future research suggestions, there is a lack of experimental research in organizational sport psychology, hence intervention studies should be conducted to advance this area (Wagstaff, Citation2019). Future studies should also explore how management, coaches, and support staff roles can be evaluated closer to the measures associated with their job description. Specifically, researchers need to consider the best way to represent the performance of personnel and provide a meaningful evaluation of their role delivery alongside athlete performance data.

From an applied perspective, there are several implications to be considered. In line with Schinke and Stambulova (Citation2017) “widening the lens” approach, we believe that practitioners are increasingly required to attend to the broader context in which an athlete operates. Thus, the application of a systems perspective to performance management in which a practitioner considers how different processes at various levels interact will enable them to not only better understand and contextualize the athlete’s story but help inform their decision-making process as to how best to support athletic performance excellence. Indeed, this wider understanding to inform decision making can be aligned with the concept of professional judgment and decision making proposed by Martindale and Collins (Citation2013). In “widening the lens” to consider performance management processes and the broader context, there are also implications for the training of sport psychologists. Specifically, we must consider how we can give neophyte practitioners the opportunity to examine issues related to organizational psychology such as performance management. For example, trainees could have a supervisory team made up of people with different areas of expertise (e.g., performance psychology, counseling psychology, organizational psychology). This might also afford the trainee the possibility to undertake placement opportunities specific to each area (Marsh et al., 2017). Indeed, there is an ongoing call for sport psychology professional bodies to consider the changing nature of service provision by practitioners and to update training pathways to better support and prepare practitioners (Sly et al., Citation2020). By developing this wider expertise, practitioners will benefit in terms of being able to provide a service to sport organizations that goes beyond mental skills training to supporting management teams to deal with complex organizational issues. Furthermore, this expertise will also help practitioners who are embedded within the support team to more effectively navigate the complexities and micropolitics of elite sport. Finally, at an operational level, the performance management framework developed in this study (see ) could be utilized in the future as a diagnostic guide to help sport psychologists identify the strengths and areas of improvement in performance management processes in elite sport programmes. Indeed, the lower-order themes in this study could potentially be adapted into self-assessment questions to provide practitioners with a template for evaluating and addressing key areas of performance management in an elite sport programme. Outside the sport domain, similar evidence-based tools have assisted human resource management and organizational psychology practitioners in developing more effective performance management in the workplace (e.g., Pulakos et al., Citation2012).

To conclude, the purpose of this study was to identify performance management processes within elite sport and explore how they interact. The research adds to a small number of studies exploring performance management in this highly complex domain. Three general dimensions were identified representing the key performance management processes at strategic, operational, and individual levels. Additionally, the dynamic and interrelated nature of performance management processes was identified as a further dimension which helped explain how these processes interact and how the role of the performance leader can influence these processes. Finally, the preliminary framework developed in this study and findings it represents, offers practitioners with knowledge and understanding of the wider organizational processes that affect athlete and team performance within elite sport; thus enabling them to provide support across different levels of the sport organization.

Open Scholarship

This article has earned the Center for Open Science badges for Open Materials through Open Practices Disclosure. The data and materials are openly accessible at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1212328. To obtain the author’s disclosure form, please contact the Editor.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 A copy of the interview guide is available by contacting the corresponding author.

References

- Aguinis, H. (2013). Performance management (3rd ed.). Pearson/Prentice Hall.

- Armstrong, R. (2019). Critical realism and performance measurement and management: Addressing challenges for knowledge creation. Management Research Review, 42(5), 568–585. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/MRR-05-2018-0202

- Arnold, R., Collington, S., Manley, H., Rees, S., Soanes, J., & Williams, M. (2019). The team behind the team”: Exploring the organizational stressor experiences of sport science and management staff in elite sport. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 31(1), 7–26. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2017.1407836

- Arnold, R., Fletcher, D., & Anderson, R. (2015). Leadership and management in elite sport: Factors perceived to influence performance. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 10(2–3), 285–304. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1260/1747-9541.10.2-3.285

- Arnold, R., Fletcher, D., & Hobson, J. A. (2018). Performance leadership and management in elite sport: A black and white issue or different shades of grey? Journal of Sport Management, 32(5), 452–463. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2017-0296

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2017). Job demands-resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22(3), 273–285. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000056

- Bhaskar, R. (1979). The possibility of naturalism: A philosophical critique of the contemporary human sciences. Humanities Press.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589–597. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

- Brown, C. J., Butt, J., & Sarkar, M. (2020). Overcoming performance slumps: Psychological resilience in expert cricket batsmen. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 32(3), 277–296. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2018.1545709

- Brudan, A. (2010). Rediscovering performance management: Systems, learning and integration. Measuring Business Excellence, 14(1), 109–123. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/13683041011027490

- Burke, S. (2016). Rethinking ‘validity’ and ‘trustworthiness’ in qualitative inquiry: How might we judge the quality of qualitative research in sport and exercise sciences? In B. Smith & A. C. Sparkes (Eds.), Routledge handbook of qualitative research in sport and exercise (pp. 330–339). Routledge.

- Burton, L. J. (2015). Underrepresentation of women in sport leadership: A review of research. Sport Management Review, 18(2), 155–165. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2014.02.004

- Cascio, W. F. (2015). Industrial–organizational psychology: Science and practice. In J. D Wright (Ed.), International encyclopedia of the social & behavioral sciences (pp. 879–884). Elsevier Science Ltd.

- Collins, D., & Cruickshank, A. (2012). Multi-directional management’: Exploring the challenges of performance in the World Class Programme environment. Reflective Practice, 13(3), 455–469. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2012.670630

- Coulter, T. J., Mallett, C. J., & Singer, J. A. (2016). A subculture of mental toughness in an Australian Football League club. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 22(1), 98–113. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2015.06.007

- Cruickshank, A., Collins, D., & Minten, S. (2014). Driving and sustaining culture change in Olympic sport performance teams: A first exploration and grounded theory. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 36(1), 107–120. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1260/1747-9541.8.2.271

- Day, D. V., Fleenor, J. W., Atwater, L. E., Sturm, R. E., & McKee, R. A. (2014). Advances in leader and leadership development: A review of 25 years of research and theory. The Leadership Quarterly, 25(1), 63–82. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2013.11.004

- de Haan, D., & Sotiriadou, P. (2019). An analysis of the multi-level factors affecting the coaching of elite women athletes. Managing Sport and Leisure, 24(5), 307–320. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/23750472.2019.1641139

- DeNisi, A. S., & Murphy, K. R. (2017). Performance appraisal and performance management: 100 years of progress? The Journal of Applied Psychology, 102(3), 421–433. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000085

- Ekstrand, J., Lundqvist, D., Davison, M., D'Hooghe, M., & Pensgaard, A. M. (2019). Communication quality between the medical team and the head coach/manager is associated with injury burden and player availability in elite football clubs. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 53(5), 304–308. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2018-099411

- Feddersen, N. B., Morris, R., Littlewood, M. A., & Richardson, D. J. (2020). The emergence and perpetuation of a destructive culture in an elite sport in the United Kingdom. Sport in Society, 23(6), 1004–1022. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2019.1680639

- Fletcher, A. J. (2017). Applying critical realism in qualitative research: Methodology meets method. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 20(2), 181–194. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2016.1144401

- Fletcher, D., & Arnold, R. (2011). A qualitative study of performance leadership and management in elite sport. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 23(2), 223–242. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2011.559184

- Fletcher, D., Hanton, S., Mellalieu, S. D., & Neil, R. (2012). A conceptual framework of organizational stressors in sport performers. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 22(4), 545–557. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0838.2010.01242.x

- Gray, D. E. (2013). Doing research in the real world. Sage.

- Katz, D., & Kahn, R. L. (1978). The social psychology of organizations (2nd ed.). Wiley.

- Kinicki, A. J., Jacobson, K. J., Peterson, S. J., & Prussia, G. E. (2013). Development and validation of the performance management behavior questionnaire. Personnel Psychology, 66(1), 1–45. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12013

- Marsh, M. K., Fritze, T., & Shapiro, J. L. (2017). Layers of oversight: Professional supervision, meta- supervision, and peer mentoring. In M. W. Aoyagi, A. Poczwardowski & J. L. Shapiro (Eds.), The peer guide to applied sport psychology for consultants in training (pp. 80–93). Routledge/Psychology Press.

- Martin, C., Eys, R., & Spink, D. (2017). The social environment in sport organizations. In C. R. D. Wagstaff (Ed.), The organizational psychology of sport: Key issues and practical applications (pp. 217–234). Routledge.

- Martindale, A., & Collins, D. (2013). The development of professional judgment and decision making expertise in applied sport psychology. The Sport Psychologist, 27(4), 390–398. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.27.4.390

- McCalla, T., & Fitzpatrick, S. (2016). Integrating sport psychology within a high-performance team: Potential stakeholders, micropolitics, and culture. Journal of Sport Psychology in Action, 7(1), 33–42. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/21520704.2015.1123208

- Molan, C., Kelly, S., Arnold, R., & Matthews, J. (2019). Performance management: A systematic review of processes in elite sport and other performance domains. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 31(1), 87–104. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2018.1440659

- Molan, C., Matthews, J., & Arnold, R. (2016). Leadership off the pitch: The role of the manager in semi-professional football. European Sport Management Quarterly, 16(3), 274–291. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2016.1164211

- Nadin, S., & Cassell, C. (2006). The use of a research diary as a tool for reflexive practice. Qualitative Research in Accounting and Management, 3(3), 208–217. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/11766090610705407

- Osbeck, L. M. (2014). Scientific reasoning as sense making: Implications for qualitative inquiry. Qualitative Psychology, 1(1), 34–46. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/qup0000004

- Parker, I. (2014). Discourse dynamics: Critical analysis for social and individual psychology. Routledge.

- Pulakos, E. D., Mueller-Hanson, R., O’Leary, S. R., & Meyrowitz, M. M. (2012). Building a high-performance culture: A fresh look at performance management. SHRM Foundation.

- Radnor, Z. J., & Barnes, D. (2007). Historical analysis of performance measurement and management in operations management. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 56(5/6), 384–396. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/17410400710757105

- Rankin-Wright, A. J., Hylton, K., & Norman, L. (2019). Negotiating the coaching landscape: Experiences of Black men and women coaches in the United Kingdom. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 54(5), 603–621. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690217724879

- Rynne, S. B., & Mallett, C. J. (2014). Coaches’ learning and sustainability in high performance sport. Reflective Practice, 15(1), 12–26. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2013.868798

- Schinke, R. J., & Stambulova, N. (2017). Context-driven sport and exercise psychology practice: Widening our lens beyond the athlete. Journal of Sport Psychology in Action, 8(2), 71–75. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/21520704.2017.1299470

- Schleicher, D. J., Baumann, H. M., Sullivan, D. W., Levy, P. E., Hargrove, D. C., & Barros-Rivera, B. A. (2018). Putting the system into performance management systems: A review and agenda for performance management research. Journal of Management, 44(6), 2209–2245. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206318755303

- Sly, D., Mellalieu, S. D., & Wagstaff, C. R. D. (2020). It’s psychology Jim, but not as we know it!”: The changing face of applied sport psychology. Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology, 9(1), 87–101. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/spy0000163

- Smith, B., & McGannon, K. R. (2018). Developing rigor in qualitative research: Problems and opportunities within sport and exercise psychology. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 11(1), 101–121. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2017.1317357

- Sparkes, A. C., & Smith, B. (2014). Qualitative research methods in sport, exercise and health: From product to process. Routledge.

- Tracy, S. J. (2010). Qualitative quality: eight ''big-tent'' criteria for excellent qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry, 16(10), 837–851. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800410383121

- Van Wingerden, J., Derks, D., & Bakker, A. B. (2017). The impact of personal resources and job crafting interventions on work engagement and performance. Human Resource Management, 56(1), 51–67. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21758

- Van Wingerden, J., Derks, D., Bakker, A., & Dorenbosch, L. (2013). Job crafting in special education: A qualitative analysis. Behavior & Organization, 26, 85–103. urn:NBN:nl:ui:24-uuid:92fb8a18-fc71-4fab-aa4c-b7a96c57115c

- Wagstaff, C. R. D. (2019). Taking stock of organizational psychology in sport. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 31(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2018.1539785