Abstract

This study explores the reasons given by five elite athletes for choosing to seek psychiatric support and treatment outside, rather than inside, their own sport environments. Life story interviews were conducted with these athletes, who were recruited from an open psychiatric clinic in Stockholm, Sweden. The interviews were then subjected to a structural and a thematic narrative analysis. The former revealed the power of the performance narrative to frame the lives of the athletes by producing a single-minded focus on performance outcomes that justifies, and even demands, the exclusion of any form of psychological weakness or vulnerability. The latter revealed the relationship between the performance narrative and the process of stigmatization associated with psychiatric disorders in elite sport and how this pressures athletes to adopt specific Goffmanesque impression management strategies to protect themselves within their own sport environments. These strategies were as follows: wearing a mask (to hide their psychological suffering), adhering to a vow of silence (making stories of psychological suffering untellable in elite sport), and finding an alibi (a way of portraying suffering in an “acceptable” form). Finally, we reflect on implications for practice, including the potential of narrative care, to help elite athletes explore alternative narratives that might be supportive rather than dangerous companions when suffering from psychiatric disorders.

Lay summary: Five elite athletes were interviewed about their experiences of living with psychiatric disorders, focusing on their choice to seek psychiatric treatment outside, rather than inside, their own sport environments. Stigma and adhering to a single-minded focus on performance forced the athletes to adopt different strategies to hide their psychological suffering.

The performance narrative, characterized by a single-minded focus on performance that demands the exclusion of any form of psychological weakness, stigmatizes elite athletes with psychiatric disorders, making their stories untellable within elite sport.

To protect themselves from stigma, these athletes developed impression management strategies to hide their psychological suffering within elite sport.

Knowledge of these impression management strategies among different mental health providers working to support athletes, and the use of narrative care to explore alternative narratives, may facilitate elite athletes in seeking support, help, and understanding for their psychiatric disorders.

IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE

Introduction

The literature on mental health in elite sport has grown rapidly during the last 10 years and include a number of positions statements (Vella et al., Citation2021) and reviews (Castaldelli-Maia et al., Citation2019; Gouttebarge et al., Citation2019; Walton et al., Citation2021). However, Reardon et al. (Citation2019) noted that studies generally report cross-sectional surveys measuring symptoms of disorders without the use of diagnostic interviews based on the criteria in classification manuals such as the International Classification of Mental and Behavioral Disorders (ICD-10) (Sheehan et al., Citation1998; World Health Organization, Citation2009). Against this backdrop, as pointed out by Ekelund et al. (Citation2022), research on elite athletes with established psychiatric disorders is sparse and so our understanding of how they go about seeking psychiatric treatment remains limited. This is problematic because without such understanding athletes may suffer in silence which can lead to further unnecessary suffering and a worsened prognosis (Haddad & Haddad, Citation2015).

One of the few studies, conducted by Schaal et al. (Citation2011), that considered the prevalence of established psychiatric disorders assessed by a licensed caregiver was based on the psychiatric evaluations of 2,067 French high-level athletes competing at the international and/or national level. In this cohort, 17% were found to have had at least one ongoing or recent psychiatric disorder within the last 6 months. In comparison, in a cross-sectional study of Swedish elite athletes by Åkesdotter et al. (Citation2020), 8.1% self-reported a history of psychiatric disorders assessed by a licensed professional, with depressive, stress-related, and eating disorders most commonly reported. Depressive disorders typically entail feelings of worthlessness, loss of energy and interest, changes in appetite/sleep, and suicidal thoughts (World Health Organization, Citation2009). A meta-analysis of anxiety/depressive symptoms in currently active elite athletes found a prevalence of 34% (Gouttebarge et al., Citation2019), and at least one anxiety disorder was diagnosed in 8.6% of French elite athletes (6-month prevalence) during yearly psychiatric evaluations (Schaal et al., Citation2011). Anxiety disorders include excessive worry, anxiety in social or performance contexts, obsessions and compulsions, and panic attacks (World Health Organization, Citation2009). The risk of eating disorders is higher in athletes than others (Joy et al., Citation2016), and the prevalence of disordered eating and eating disorders has been found to range between 0–19% and 6–45% in male and female athletes, respectively (Bratland-Sanda & Sundgot-Borgen, Citation2013).

Research regarding the mental health of elite athletes has so far been predominantly quantitative (Souter et al., Citation2018). Such research provides important knowledge of the prevalence of psychiatric disorders and their symptoms in elite athletes. Less is known, however, about the lived experiences of elite athletes with established psychiatric disorders, their help-seeking processes, and how they navigate their life as an athlete in times of psychological suffering. Meaning-centered insights, gained from exploring the social realities of these athletes, have therefore been suggested as an important addition to current research (Pereira Vargas et al., Citation2021).

Recently, qualitative researchers have started to answer this call, turning their attention toward athletes with psychiatric disorders. For example, Doherty et al. (Citation2016) and Lebrun et al. (Citation2018) used semi-structured interviews to explore athletes’ experiences of depression. Plateau et al. (Citation2017) also used interviews to explore the lived experience of female athletes seeking treatment for eating disorders. In addition, various researchers, following the suggestions of Smith and Sparkes (Citation2009a) and Pereira Vargas et al. (Citation2021) regarding the value of narrative research in sport and exercise psychology and among athletes with psychiatric disorders, have adopted this approach. For example, Newman et al. (Citation2016) used a narrative approach to analyze 12 autobiographies of elite athletes suffering from depression, and Papathomas and Lavallee (Citation2014) used a narrative approach to explore the life story of an elite athlete with an eating disorder engaging in self-starvation.

To date, a limited number of studies in sport psychology have used a life story approach to investigate the theme of mental health problems in elite athletes. As far as we are aware, no previous research has used such an approach to examine multiple athletes with established psychiatric disorders as evaluated by a licensed caregiver, to explore the experience of living with and seeking treatment for their psychiatric disorders. Åkesdotter et al. (Citation2020) previously showed that almost one third of elite athletes representing national teams in Sweden had sought help for psychological suffering, but this help was rarely found inside their own sport or national team. Instead, elite athletes seemed to go outside their sport environments for treatment. The same preference has also been found in student athletes in a study by Cutler and Dwyer (Citation2020), who preferred to seek help from non-team support over the resources available within their sport environment.

Potential explanations for seeking help outside of the sporting environment for psychiatric disorders could be the stigma surrounding psychiatric disorders in elite sport, negative previous experiences of seeking treatment, challenges of finding sufficient time, or a lack of qualified treatment options within their medical teams (Castaldelli-Maia et al., Citation2019; Gulliver et al., Citation2012). Such potential explanations need to be empirically examined by conducting research with elite athletes who have had these experiences and have made such choices.

In elite sport, athletes have been found to suppress signs of psychological suffering for fear of being judged “mentally weak,” which can lead to them being stigmatized and socially excluded by coaches and other athletes (Moreland et al., Citation2018). According to Goffman (Citation1963, p. 3), stigma is an “attribute that is deeply discrediting” that can lead to a spoiled identity and the individual being disqualified from full social acceptance. Social stigma, including negative stereotypes of those with a psychiatric disorder that operate in a discriminatory fashion, marks people out as different, reduces their status, and prevents them being seen as individuals (Haddad & Haddad, Citation2015). The stigma toward people with psychiatric disorders has a long and painful history in our society (Hinshaw, Citation2010) and is especially prevalent in contexts with strong masculine norms, such as elite sport or the military (Sharp et al., Citation2015).

Exploring the lived experiences of elite athletes with psychiatric disorders focusing on their reasons for choosing to go outside their own sport environments to seek help, support, and understanding could tell us a great deal about the dynamics and conditions within these environments. This is an important issue given that, in their review of mental health research in elite sport, Poucher et al. (Citation2021, p. 71) stated that “very little is known about how the belief systems and power structures embedded in sport organizations may impact athlete mental health or psychological distress.” Furthermore, there is a lack of research exploring what elite athletes themselves find important to communicate regarding their experiences of suffering from psychiatric disorders. This is a significant omission given the views of Haugen (Citation2022, p. 1) who emphasized the importance of understanding how elite athletes “navigate any potential barriers to treatment.”

Against the backdrop described above, in this article we draw on life story data and use a narrative approach to explore the experiences of a group of elite athletes with psychiatric disorders. By inviting them to tell their own stories of living with, and seeking treatment for, psychiatric disorders we seek to better understand their decision to seek help, support, and understanding outside, rather than inside, their own sport environments.

Methodology

Given its intention to explore the subjective experiences of a group of elite athletes with psychiatric disorders a narrative approach was deemed to be the most appropriate in terms of methodological fit and coherence. According to Papathomas (Citation2016), narrative inquiry typically falls within an interpretivist paradigm characterized by ontological relativism and epistemological social constructionism. Underpinned and informed by these assumptions, Smith (Citation2016) suggested that narrative analysis refers to a family of methods that have in common a focus on stories. For him, it can be described as “an approach that seeks to describe and interpret the ways in which people perceive reality, make sense of their worlds and perform social actions” (p. 261). Whilst this seeking, as Smith and Sparkes (Citation2009a, Citation2009b) and Sparkes and Smith (Citation2014) confirmed, can take various forms they pointed out a number of analytical strengths that are associated with narrative inquiry. These include the following that are directly relevant to our current study: (1) To reveal the temporal, emotional, and contextual quality of lives and relationships, (2) To honor the complexities of a life as lived, (3) To illuminate the subjective worlds of individuals and groups, and (4) To appreciate a person as a unique individual with agency and as someone who is socially situated and culturally fashioned, thereby telling us much about a person or group as well as society and culture.

Reflecting on how, as relational beings, athletes give meaning to events in their lives and construct their identities in and though narratives that are both personal and social, Smith and Sparkes (Citation2009a) pointed out that even though athletes have varying degrees of agency to construct the stories they tell (e.g., about a psychiatric disorder), they are not totally free to construct just any story they wish about themselves. This is because athletes do not tell stories about themselves under conditions of their own making, nor can they always deploy them for purposes of their own choosing. Various institutional orders and their representatives mandate narratives, each for different purposes and each in different forms. Likewise, when athletes tell a story about themselves, they draw upon a particular set of narrative resources that are at hand within their cultural setting and sporting environment which can be enabling or constraining. These narrative resources, however, are not equally distributed and there are differential invitations and barriers involved in telling one’s story in any given context. Athletes, therefore, act on and are acted on by the social and cultural contexts in which interaction occurs and so they can story the same event in different ways depending on the occasion and audience.

Access

Following ethical approval from the Regional Ethical Review Board, Stockholm, Sweden, elite athletes were recruited from an open psychiatric clinic in Stockholm specializing in the care of patients from elite sport based on self-referral using the website of Sweden’s public healthcare system (see Vårdguiden 1177.se). This self-referral is confidential, and Sweden has free choice of care, which means that all patients can choose where in Sweden they seek treatment. Eligibility criteria to receive treatment at the clinic, and also to participate in our study, were currently representing a national team or having done so within the last two years, being over 18 years old, and having at least one psychiatric diagnosis according to the International Classification of Mental and Behavioral Disorders (ICD-10) (World Health Organization, Citation2009). To avoid any distraction or interruption to treatment, only athletes who had completed their treatment within the last three years and been discharged from the clinic (i.e., no longer needed psychiatric treatment) were invited to participate.

Staff at the psychiatric clinic were approached by Author 2, who was also employed part-time as a psychotherapist at the clinic. First, the purpose of the study was explained to the staff, who were then asked if they would assist by forwarding information about the study to athletes who had completed treatment at the clinic. The strategy was to recruit a diverse sample in terms of gender, age, sport, and psychiatric disorder to investigate potential similarities in and between their life stories of developing, living with, and seeking treatment for psychiatric disorders.

Consequently, we did not ask the athletes to review their medical record since specific disorders was not the aim of this study, and it was important to safeguard each participants privacy. Thus, specific psychiatric diagnoses and reasons for treatment are therefore self-reported by the participants. Five athletes were originally recruited and after the first interviews we had a broad library of life stories that together created a sufficient base to answer the research questions.

The five elite athletes agreed to their contact information being forwarded to Author 1 so that they could take part in the study. For disclosure, one of the five athletes had received psychiatric treatment from Author 2, so this athlete might have felt obliged to participate in the study based on this prior relationship. However, this risk is limited since all athletes in the study had already completed their treatment, and all information and communication regarding the study, as well as all interviews, were conducted by Author 1 who had no prior relationship with any of the athletes.

At the initial contact with these athletes, Author 1 explained the purpose of the study and the applicable ethical principles regarding, for example, voluntary participation and the participants’ right to withdraw at any time without a need for explanation and with no personal or professional consequences for them. As athletes were competing at the highest level (e.g., national team) and part of a small, potentially identifiable group of participants, pseudonyms were used and identifying variables such as age and sport were not revealed.

Participants

Emma, approximately 20 years old, engaged in an individual sport and had received treatment for depression and social phobia. Martin, approximately 30 years old, engaged in an individual sport and had received treatment for anxiety and depression. Jonas, approximately 30 years old, played a team sport, had been diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and had received treatment for depression. Lisa, approximately 20 years old, engaged in an individual sport and had received treatment for a long-term eating disorder. Elin, approximately 25 years old, engaged in an individual sport and had received treatment for depression.

Data generation

A life story, according to Atkinson (Citation2007), is the story a person chooses to tell about the life they have lived, including the important events, experiences, and feelings along the way that have shaped how they have become the person they are in the present and the person they might be in the future. Where life stories are embedded in an interview they can encompass different ends of the narrative spectrum from stories of a whole life, or “big stories,” to what Bamberg (Citation2006) terms “small stories” or partial narratives that refer to parts of people’s lives. As a qualitative research method, it is recognized that life story interviews are useful for revealing the subjective inner life of interviewees in terms of how they see themselves in the present and at other times in their lives, and are well suited to discovering the confusion, ambiguities, and contradictions that are played out in everyday experiences (Atkinson, Citation1998, Citation2007; Plummer, Citation2001).

Importantly, the life story told in such interviews is a joint construction that involves collaboration between the interviewee and the researcher to allow a story to unfold in the interaction between the two (Gubrium & Holstein, Citation2007; Russell, Citation2022; Sikes & Goodson, Citation2017). In this guided interaction, the researcher encourages and supports the interviewee to tell their story in their own words and at their own pace within the interview setting. Here, in terms of power relationships, the interviewee is positioned as an “expert” on their own life whilst the researcher is positioned as a “learner” who asks relevant questions accordingly.

In this study, individual life story interviews were conducted on two occasions with each of the five participants, at a time and place of their convenience with a gap between interviews of 3–6 months. During the interview, the athletes were first asked to tell the stories of their careers in elite sport. When psychological suffering and/or symptoms of psychiatric disorders emerged in the conversation, follow up questions were asked. These questions concerned: personal experiences (“When was the first time you noted that something was different and changing regarding your mental health?”), support (“What did you do when you started to experience symptoms of a psychiatric disorder?”), and help-seeking (“How was the process of seeking professional treatment?”). After the first interview, Author 1 listened to and transcribed the interview recordings. Before the second interview, questions were formulated to follow up aspects of the participants’ stories that were either unclear or were felt to be important and warranted deeper exploration. These aspects were then addressed in the second interview. The average duration of each interview was 1 h and 45 min.

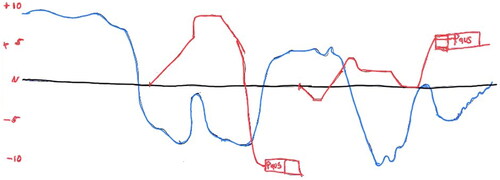

A modified version of the biographical mapping method developed by Schubring et al. (Citation2019) was also used in this study. This combines a semi-structured drawing activity as part of the interview which creates an opportunity to connect key points in each athlete’s unfolding story of developing and living with a psychiatric disorder. To guide the drawing and recall processes, Schubring et al suggest the following.

The interviewee is asked to plot development lines (e.g., a career timeline; a health timeline) in a two-dimensional biographical mapping grid and to comment and explain the drawings. The iterative combination of narrative interview questions with the drawing activities results in the generation of both rich interview data and a biographical map. (p. 3).

Figure 1. Example of a participant’s biographical map (Red = Sporting career; Blue = Mental health; N = timelines and neutral baseline. (Names of key markers removed to maintain anonymity).

Initially, before the data generation, two pilot interviews were conducted with two elite athletes with a history of psychiatric disorders who were personal friends of Author 1. At the end of these pilot life story interviews, the participants were invited to share their experiences of the interview and how the interaction between them and the interviewer might be improved. Based on their feedback, an initial “grand tour” question (Sparkes & Smith, Citation2014) was dropped, since the participants felt that having to put together a “big” story at the start of the interview would provoke anxiety among interviewees. Likewise, the biographical mapping method described above was also incorporated based on the feedback from the pilot studies, as it was perceived as a helpful tool to position the story in place and time.

Given the vulnerabilities of the athletes involved, during the interviews and throughout the study, interactions with Author 1 were informed by a culturally responsive relational reflexive ethics (Lahman et al., Citation2011). For example, relational ethics required that Author 1 should value dignity, mutual respect, and connectedness between herself and the athletes, with an obligation to care for them. Likewise, in terms of reflexive ethics, this entailed Author 1 being sensitive to the interactions among herself, the athletes, and the interview situations, adapting in a responsive manner, and respecting the athletes’ safety, privacy, dignity, and autonomy. Importantly, Author 1 had clinical training that would help her notice any signs of distress during the interview and act to alleviate the situation. Furthermore, independent and confidential psychological support was made available to the participating athletes should they want it following an interview. The data are not publicly available as they contain information that could compromise the confidentiality agreement with the participating athletes.

Data analysis

With regard to the family of narrative analytical methods available for interpreting life story data, Smith (Citation2016), Smith and Sparkes (Citation2009b) and Sparkes and Smith (Citation2014) noted two equally valuable but different standpoints that researchers might choose to operate from. These are known as the storyanalyst and the storyteller. The former steps back from the story generated and employs analytical procedures, strategies, and techniques in order to abstractly scrutinize, explain, and think about its certain features. The storyanalyst conducts research on narratives, where narratives are the object of study and placed under scrutiny by utilizing a specific type of narrative analysis (e.g., thematic, structural or performative) and then producing a realist tale as described by King (Citation2016) and Sparkes (Citation2002) about stories. In contrast to a storyanalyst, when operating as a storyteller the analysis is the story. Rather than adding another layer of analysis and theory, storytellers prefer instead to treat the stories that people tell about themselves as analytical and theoretical in their own right. In view of this, rather than produce realist tales, storytellers engage in creative analytic practices to communicate their “findings”via, for example, by the use of creative nonfiction, poetic representations or ethnodrama.

With regard to the current study, Author 1 chose to adopt the position of storyanalyst and therefore subjected the life story data to first a structural analysis and then a thematic narrative analysis as described by Smith (Citation2016), Smith and Sparkes (Citation2009b), Sparkes and Smith (Citation2014) and Riessman (Citation2008). The former type of analysis, according to these scholars, focuses on how stories are put together and the kind of narrative types along with their associated plot-lines that are drawn on by the storyteller to scaffold and structure their story and give meaning to their experiences. Accordingly, in the process of immersing herself in the data by repeatedly reading the interview transcripts and listening to the recorded interviews several times, the central concern of Author 1 was to identify any narrative types and plot-lines that were being used by elite athletes in telling their stories. Having identified the “performance narrative” as described by Douglas and Carless (Citation2015) as the dominant narrative, Author 1 provided supporting data to justify this interpretation to Author 2 and Author 3 who subsequently confirmed this interpretation.

Next, Author 1 conducted a thematic narrative analysis of the interview data that, in contrast to the structural analysis, focused on the what of stories with an exclusive focus on their content. The purpose of this form of analysis is to identify central themes (i.e., patterns) and the relationship amongst these in the stories told by an individual or group of people. Here, Author 1 went through the transcripts and tagged with a code each text passage that had some relevance to the research question informing the study. Author 1 then identified the key themes around which various codes clustered as central organizing concepts in explaining why the participants chose to seek psychiatric support and treatment outside their own sport environments. At this stage, quotations perceived to highlight the essence of these stories were selected. During analysis, both inductive (bottom-up) and deductive (top-down) reasoning was used, which in combination constituted abductive reasoning (Sparkes & Smith, Citation2014).

The thematic analysis conducted by Author 1, along with the interview transcripts and selected quotations, were then sent to Author 2 as part of a process of peer debriefing (or peer reviewing, as it is sometimes known). This involved Author 2, as a peer researcher with experience in the field of elite sport and mental health, reviewing and assessing the transcripts in relation to the key themes identified by Author 1 and the text passages used to support them. Once this was done, Authors 1 and 2 reflected on the process involved and confirmed the key themes identified in the data. Finally, the key themes and supporting data along with the interpretations of them were sent to Author 3, who played the role of “critical friend” as described by Sparkes and Smith (Citation2014) by acting as a theoretical sounding board to encourage critical reflection upon, and exploration of, alternative explanations and interpretations of the interview data.

Given the difficulty of conducting a structural analysis and a thematic narrative analysis simultaneously, it is importan to note that Author 1 engaged in a process of analytical bracketing as advised by Gubrium and Holstein (Citation2009). Accordingly, during the structural analysis the central question asked of the life story data generated during the interviews was “What type of narrative type is being used here by the elite athletes and what is its central plot-line?” That is, no attention was devoted to the whats of the telling which were bracketed out. In contrast, during the thematic narrative analysis issues of structure, the hows, were bracketed out and attention was focused only on the whats or content of the stories for the purpose of identifying possible themes within them. Having gone though this process, Author 1 was then able to ask questions about the interplay between the whats and hows of the stories told by the elite athletes and how in combination these shaped their experiences of living with a psychiatric disorder.

Goodness criteria

In his role as critical friend, Author 3 was also able to generate the required self-reflexivity among his colleagues about their subjective values and inclinations, as called for by Tracy (Citation2010), in order to achieve the goodness criterion of sincerity. In research, the authors’ own backgrounds and understandings “are often powerful forces in shaping many aspects of the research process, from the topic selection to the way data are reported and how these are interpreted” (Sparkes & Smith, Citation2014, p. 19). For example, in the present study, Author 1, who conducted the interviews, was a former elite athlete, potentially creating a situation in which some aspects of elite sport might be overlooked and left unquestioned. Consequently, as a critical friend, Author 3 played an important role in challenging her taken-for-granted assumptions about the nature of elite sport and the experiences of those involved in it. Author 1 also had extensive experience of face-to-face oral sessions with elite athletes about mental health problems and psychiatric disorders based on working as an applied sport psychologist in Sweden since 2012.

To enhance the credibility of our study, as Tracy (Citation2010) recommended, we constructed a text that is multivocal in nature and that provides the concrete detail required of a thick or rich description. For similar reasons, we also sought participant reflections that, according to Tracy, allow for “sharing and dialoguing with participants about the study’s findings, and providing opportunities for questions, critique, feedback, affirmation, and even collaboration” (p. 844). Thus, Author 1 made a separate phone call to each athlete who had participated in the study to talk about and reflect on the overall themes identified in and across the life stories.

During these phone calls, the athletes were invited to reflect on whether our interpretations and representations of their views and experiences were accurate, fair, and recognizable to them. All athletes were also presented with a written transcript of their own quotations. Any reflections the participants offered were not taken as directly validating or refuting our findings but rather as another source of data and an opportunity for further collaboration and reflexive elaboration (Sparkes & Smith, Citation2014). The feedback from the athletes indicated that they recognized the issues highlighted in the analysis below, that our interpretations were fair, that they had been represented respectfully, and that they agreed that the results could be published in their current form.

Results

The dominance of the performance narrative

The structural analysis revealed that the performance narrative, as described by Douglas and Carless (Citation2015), framed the stories told by each athlete. This is the “master” narrative framing most of the stories told by elite athletes about their careers, and this plotline also informs most public portrayals of elite athletes. Within this narrative form, performance-related concerns infuse all areas of the athlete’s life and tells a story of a single-minded dedication to sport performance that “justifies, and even demands, the exclusion or relegation of all other areas of life and self” (Douglas & Carless, Citation2015, p. 73). Importantly, as Douglas and Carless pointed out, this narrative is also problematic, as displaying any sign of weakness or vulnerability (e.g., psychiatric disorder) directly violates the storyline in which “challenges may typically be overcome through hard work, discipline, and sacrifice over time” (p. 77). Furthermore, they noted that the performance narrative encourages the development of a fragile sense of self-worth that is dependent on sport performance; this sense of self-worth becomes vulnerable during performance fluctuations, when the athlete is deselected from a team, is sick or injured, or contemplates withdrawal from sport. For Elin, this single-minded investment in sport started early in her career:

It started very clearly with, this is a place where I can exist the way I am. Here I have friends, here I am liked, here I am successful. So I put all my energy there.

To become faster and faster. Basically, you get more friends the faster you are … everyone wants to … or more people want to be with you if you say that you are getting faster.

And then you must line up new results, and the better results you get the more results you have to achieve the next time to get at least the same feeling, and the better you become the harder it always gets to achieve this somehow.

I won my first … championship and got on the podium …. At this stage, everything was new, but later when you got to this point where you had already done all of that and you did it again, but it did not have the same effect. The fix was shorter, it kind of passed faster and faster.

Wearing a mask

In his seminal work on stigma, Goffman (Citation1963, p. 3) described this as an “attribute that is deeply discrediting” that can lead to a spoiled identity and the individual being disqualified from full social acceptance. For the stigmatized, Goffman pointed out that the “actual affective response must be concealed and an appropriate affective response must be displayed” (p. 217). To avoid encountering the stigma associated with having a psychiatric disorder, the athletes in our study had become skilled users of what Goffman (Citation1959) called impression management strategies as part of their performances of self to various audiences in the frontstage, or public region, of their lives.

In relation to impression management, one such strategy used by our athletes was that of wearing a mask. This strategy was shaped by the plotline of the performance narrative that excludes and devalues the portrayal of weakness, vulnerability, or psychological suffering in the frontstage presentation of self. Such emotions could only be expressed in backstage regions to people the athletes truly trusted: only then could they remove the mask they had to wear in the frontstage in elite sport settings. As Elin stated,

It was more, here [i.e., backstage] I have suffering. Here [i.e., frontstage] I have sport. Different things … But it’s a hard world. It’s hard to show weakness in that world [i.e., frontstage].

As if to emphasize the stigma attached to psychiatric disorders in her sport, she went on to say that “to have depression, that’s like really bad. It’s like saying that you have chlamydia.” Other comments suggest that the athletes were aware of how skilled they had become in wearing a mask in frontstage regions and of how effective this was as an identity-management strategy. For example, Elin pointed out: “I have been quite good at playing theater, and kind of ‘All is fine, don’t worry’.” Likewise, when reflecting on her eating disorder, Lisa stated:

No one had a clue actually. When you have lived with it for so long, you also get really good at hiding it. It was just a part of my routine. So no, there was no one who knew.

You are supposed to have a surface that looks very perfect. So, to admit that you have something that is not all good is not the easiest thing to do. And based on that, it’s not easy to ask for help either.

Significantly, as Haddad and Haddad (Citation2015) pointed out, stigma can lead a person to avoid seeking support for symptoms of psychiatric disorders for fear of being embarrassed, misunderstood, shunned, or rejected. They noted that when this happens, the underlying problem can go untreated, causing prolonged and unnecessary suffering, and that a delay in receiving treatment can worsen the outlook of some conditions, as can the stress and anxiety caused by experiencing the stigma itself.

A vow of silence

One reason given by the athletes for having to wear a mask rather than disclose their psychological suffering and try to be open about their symptoms was that, should they do so, they would be met with a vow of silence that operates in elite sport regarding such issues. Given the stereotypical view of elite athletes as mentally strong and able to master the demands of the performance narrative plotline discussed earlier, this view seemed not only to come from themselves but was often reinforced by others who emotionally invalidated their psychological suffering. For example, Emma recalled trying to initiate conversations about her self-injury behaviors by showing the marks on her skin:

I remember that I used to show people, those who were close to me. I said it like casually, ‘I did not feel so good yesterday so I did this to myself.’ It was like a little cry for help. But no one really got it.

So, all right, [they thought,] ‘She [i.e., Elin] is sad’—that was when I told them. But after that there was no one who dared to touch on it or ask ‘Are you okay?’ or something like that. It was just as if they pretended like nothing had happened because it was too inconvenient. … And often in this culture, the way I understand it, you don’t talk so much about it if you are going through a hard time. You just go for it. You think about other stuff. That might be their way of telling me ‘This is how we deal with it, it might work for you too.’

But it is a little bit like if you have fallen off a bike, and hurt yourself, and instead of getting a band-aid and a hug, you get yelled at for getting hurt in the first place. The consequence of this is that, in the end, you don’t tell anyone that you have fallen off the bike. And therein lies an incredible loneliness.

Finding an alibi

The ways in which wearing a mask and a vow of silence are imposed by others on our athletes, working in tandem with the communication constraints imposed by the performance narrative, highlight how the sport environments they inhabit are hostile to the acknowledgement and expression of symptoms of psychiatric disorders and associated feelings. It is ironic, therefore, that the one time the athletes can slip off the mask and break the vow of silence within sport, while still adhering to the performance narrative, is when they experience a traumatic event that affects their mental health, thereby providing an “acceptable” form of suffering. Such traumatic events provide an alibi for expressing emotions such as vulnerability, suffering, and fragility without experiencing stigmatization. For example, Emma’s alibi was provided when she was diagnosed with cancer during her career, giving her what she thought was a legitimate reason in the eyes of others for taking a break from training:

Because I was suffering so much at that time I thought it was amazing to get cancer. So I could take a small break, kind of, from all this negativity in sport and that kind of thing. And it was a fairly ‘nice’ cancer if you can speak about it that way. It sounds a little strange. But I thought it was amazing. … And I was thinking that I was feeling so bad, that I did not even want to show up and train, but I did not want to give up my sport. And then it kind of happened, that now I have a reason to maybe take a little break from this.

And then there was also a lot of other stress that was mixed up in that. I was just back from an injury and did not feel that I was any good and so on. … But that felt okay to be sad for. This thing that happened was serious enough so that I could actually share this feeling …. People would understand that I am not doing well because of this [i.e., the friend’s suicide], so that made me dare to tell them.

At that stage it was suddenly accepted from the outside—‘Of course, now he should go to a psychologist when he is hurt like that and cannot compete.’ But for me it was partly that, but also things like why do I not even want to compete?

Discussion

In this article we have focused on why five Swedish elite athletes chose to seek support and psychiatric treatment outside of, rather than inside, their own sport environment. Our analysis reveals how our athletes made this choice because within the constraints of the performance narrative their experiences are deemed non-tellable. They felt compelled to remain silent about their suffering and to adopt specific impression management strategies to avoid and protect themselves from the stigma associated with psychiatric disorders in elite sports.

One of the advantages with the life story approach is that experiences are reflected on from a “vantage point that allows them to see their life as a whole, to see life subjectively across time as it all fits together…” (Atkinson, Citation1998, p. 5). The stories told by the athletes’ highlighted how certain values and discourses contributed to stigmatize psychological suffering and help seeking. In this light, the day-to-day realities of hiding psychological suffering make sense, despite the public rhetoric of sports organizations being more aware and open to mental health problems in athletes. Given that our findings challenge this rhetoric, we now offer some of our own reflections on how a safer and more supportive sporting environment might be developed for elite athletes who experience psychiatric disorders.

Applied implications

Narrative care

As our analysis revealed, all athletes in this study adhered to the performance narrative. Following the work of Frank (Citation2010) and Sparkes and Stewart (Citation2019), we would argue that this narrative causes trouble for elite athletes and is a dangerous companion in times of psychological suffering and when they develop psychiatric disorders. Given this danger, we suggest that all stakeholders in elite sport, including coaches, the medical team and sport psychologists, learn to recognize this narrative in their athletes and consider how they might operate with the spirit of narrative care.

Narrative care, according to Frank (Citation2021) involves both care through narrative means and care of people’s narratives. To cultivate this kind of care, Frank proposes a list of openings that can be adapted and phrased in language appropriate to those involved. One question we might ask is: Which stories are an athlete’s active companions? Having identified which stories (e.g., wearing a mask, the vow of silence, and finding an alibi) are active companions we might then ask: How are these stories working for and on the athlete in shaping their thoughts, feelings and behaviors?

In this sense, the “wearing a mask” story works for athletes with a psychiatric disorder by protecting them from being stigmatized and allows them to hold their own within a sport environment that is hostile to them. The same story, however, also works on athletes by keeping issues relating to psychiatric disorders back-stage, thus reinforcing the vow of silence and self-silencing within elite sport. One task of those supporting athletes could be to open a dialog with the athletes regarding how the performance narrative works both for and on them in the short and long term, and how, at times, this story might in fact be acting against their needs and interests. According to Frank (Citation2021) stories work by holding people close to particulars and so placing stories in narrative types frees our thinking from the specificity of stories and offers a distance from them which then allows for the consideration of alternatives that might better serve our interests and needs.

If the performance narrative at times is deemed to be a danger to them by the athletes, then the conversation can turn to the possibility of other narrative types that might be available to them within elite sport. For example, the discovery narrative—with a focus on exploration, learning, life balance and discovery—and the relational narrative—highlighting the importance of relationships—as described by Douglas and Carless (Citation2015) could be introduced for consideration.

Likewise, attention can be drawn to the zipper effect narrative (Wilson et al., Citation2019), that highlights the benefits of being able to switch back and forth between mental toughness (intensely focused that often uses avoidance emotional regulation) and self-compassion (that fosters self-care and acknowledging emotions). The purpose of introducing a range of narratives is not to advocate one type over another, but to simply recognize other narratives do exist and can be helpful during different parts of an athletic career. This recognition is part of a larger process of expanding the narrative resources in elite sport with a view to helping athletes with psychiatric disorders to find narratives that are more helpful for them to adhere to, especially in times of psychological suffering.

Help seeking

Interestingly, none of the athletes talked about a lack of help within elite sport. Instead, the “vow of silence” seemed to prevent the athletes from even mentioning any form of psychological suffering within this context. This finding resonates with previous research that found Swedish elite athletes to be reluctant to contact the medical team in their sport when struggling with their mental health, in contrast to a low threshold of help-seeking in regard of physiological suffering (Åkesdotter et al., Citation2020). Previous research has also indicated that elite- and student athletes are more reluctant to seek psychiatric treatment compared to the general population (Castaldelli-Maia et al., Citation2019; Wahto et al., Citation2016). For example, Wahto et al. (Citation2016) found that student-athletes were more likely to seek psychiatric treatment by referral from a family member as compared to a coach or fellow athlete. Athletes also fear that fellow teammates will change their perceptions of them if they should seek psychiatric treatment (Gulliver et al., Citation2012). Listening to and learning from athletes who have actually reached out and sought psychiatric treatment, and understanding their pathways of doing so could therefore provide important insights on how to best facilitate help seeking in the future.

When the elite athletes in our study did try to seek help and support within elite sport, an external alibi was needed that justifyied their suffering in the eyes of others. As described by Martin: “At that stage it was suddenly accepted from the outside – ‘Of course, now he should go to a psychologist when he is hurt like that and cannot compete’.” This is problematic as it leaves the initiation of help-seeking up to chance and only when a traumatic event severe enough to avoid stigmatization presents itself. Until the stigma associated with psychiatric disorders in elite sport is removed, then it remains that the opportunity to seek external, independent and confidential treatment could serve as an important secondary avenue to the medical resources available within this sporting environment. Seeking and receiving treatment outside of the elite sport context may therefore faciliate help-seeking behavior among elite athletes given the level of stigma and invalidation that still exists.

Stigma

The strong impact of the stigma against psychiatric diagnoses in elite sport largely dominated the athletes’ life stories. According to Haddad and Haddad (Citation2015) stigma operates as a powerful disincentive to seek psychiatric treatment in the general population. Likewise, Moreland et al. (Citation2018) and Souter et al. (Citation2018) noted that many elite athletes choose not to reveal a psychiatric disorder, or discuss symptoms of it, based on the stigma still associated with these experiences. As a potential remedy, previous research has found that “the better people know mental illness, or people with these illnesses, the less likely they are to stigmatize” (Corrigan & Nieweglowski, Citation2019). High-profile athletes with a history of psychiatric disorders could therefore play an important role by acting as ambassadors to open up a dialog about these experiences, thereby breaking the “vow of silence” in elite sport. For example, Simone Biles, who holds the record for winning the most World Championship medals of any gymnast, started an international conversation on the mental health of athletes by prioritizing her own health and wellbeing during the Tokyo Olympic Games.

Published autobiographies by highly regarded athletes telling their story of living with psychiatric disorders can also act as a valuable resource. As recommended by Sparkes and Stewart (Citation2016) this approach allows the reader to enter and understand the complex realities of living with such disorders and can potentially reduce stigma. Importantly, this and other mental health literacy interventions need to be further researched and evaluated before they are introduced to sport organizations (Corrigan & Nieweglowski, Citation2019; Gorczynski et al., Citation2021).

Even though stigma is recognized as a major challenge in elite sport, less is known about the impression management strategies elite athletes use to hide their psychological suffering. The strategies found in this study (wearing a mask, adhering to a vow of silence, and finding an alibi) seemed to be universal as the athletes represented different genders, ages, sports, and diagnoses. Being aware of these strategies could provide important insights for those working to support mental health in elite sport. On this issue, Haugen (Citation2022, p. 1) stated that “it is important for medical professionals to understand not only how mental health concerns manifest in athletes but be ready to help athletes navigate any potential barriers to treatment.” Based on the “frontstage” presentation of self (Goffman, Citation1963) by the athletes in our study “putting on a mask” it is easy to be misguided and to assume that psychological suffering and disorders don’t exist in our context because “We never see it.” However, based on our findings, this assumption, without knowledge of the expression of management strategies, may not only lead to a high risk of failing to recognize mental health disorders, but also to a false belief that such disorders do not exist in elite sports.

Invalidation

Hiding psychological suffering had not always been the strategy used by the athletes in this study. The life-story interviews revealed that the athletes had tried to open up about their experiences, but these attempts had been met by emotionally invalidating reactions. This finding is worrying as these prior experiences of invalidation prevented them from opening up and seeking help and support within their own sport environments. Furthermore, invalidation itself may have negative consequences on both physical and mental health and have been connected to emotional dysregulation which is present in many psychiatric disorders (Zielinski & Veilleux, Citation2018). Validating and normalizing these affective experiences in elite sport, instead of suggesting that they are inappropriate, could potentially do a great deal to assist athletes seek help and support in the future.

It is also important that future research investigate whether or not elite athletes with a psychiatric diagnosis have been discriminated against in various ways (i.e., dis-credited or devalued etc.) in elite sport based on their diagnosis. This is especially important to address as Biggin et al. (Citation2017) and Souter et al. (Citation2018) noted that the fear of being restricted from training and competing was an important reason athletes gave for remaining silent about psychological suffering.

In the long term, stigma related problems may best be solved by changing the culture in elite sport. As noted by Rüsch et al. (Citation2005), however, regarding mental health stigma in the general population, until this is actually removed we need to address the situation as it stands and do what we can as and where possible. In this regard, as our findings illustrate, a useful starting point might be the development of more psychiatric clinics (like the one in Stockholm) that offer specialized care for athletes from elite sport based on a self-referral and confidential basis. Without it, the athletes in our study potentially would have suffered alone and in silence in their sport environment, with potentially dire consequences.

Disclosure statement

Author 2 had a part-time employment as a psychotherapist at the clinic used for recruitment. There are no other competing interests to declare.

References

- Åkesdotter, C., Kenttä, G., Eloranta, S., & Franck, J. (2020). The prevalence of mental health problems in elite athletes. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 23(4), 329–335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2019.10.022

- Atkinson, R. (1998). The life story interview. Sage.

- Atkinson, R. (2007). The life story interview as a bridge in narrative inquiry. In D. J. Clandinin (Ed.), Handbook of narrative inquiry: Mapping a methodology (pp. 224–245). Sage.

- Bamberg, M. (2006). Stories: Big or small. Why do we care? Narrative Inquiry, 16(1), 139–147. https://doi.org/10.1075/ni.16.1.18bam

- Biggin, I. J. R., Burns, J. H., & Uphill, M. (2017). An Investigation of athletes’ and coaches’ perceptions of mental ill-health in elite athletes. Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology, 11(2), 126–147. https://doi.org/10.1123/jcsp.2016-0017

- Bratland-Sanda, S., & Sundgot-Borgen, J. (2013). Eating disorders in athletes: Overview of prevalence, risk factors and recommendations for prevention and treatment. European Journal of Sport Science, 13(5), 499–508. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2012.740504

- Cassidy, T. (2016). The role of theory, interpretation and critical thought within qualitative sport and exercise research. In B. Smith & A. C. Sparkes (Eds.), Routledge handbook of qualitative research in sport and exercise (pp. 419–430). Routledge.

- Castaldelli-Maia, J. M., Gallinaro, J. G. d M. E., Falcão, R. S., Gouttebarge, V., Hitchcock, M. E., Hainline, B., Reardon, C. L., & Stull, T. (2019). Mental health symptoms and disorders in elite athletes: A systematic review on cultural influencers and barriers to athletes seeking treatment. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 53(11), 707–721. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2019-100710

- Corrigan, P. W., & Nieweglowski, K. (2019). How does familiarity impact the stigma of mental illness? Clinical Psychology Review, 70, 40–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2019.02.001

- Cutler, B. A., & Dwyer, B. (2020). Student-athlete perceptions of stress, support, and seeking mental health services. Journal of Issues in Intercollegiate Athletics, 13, 206–226.

- Doherty, S., Hannigan, B., & Campbell, M. J. (2016). The experience of depression during the careers of elite male athletes. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1069. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01069

- Douglas, K., & Carless, D. (2015). Life story research in sport: Understanding the experiences of elite and professional athletes through narrative. Routledge.

- Ekelund, R., Holmström, S., & Stenling, A. (2022). Mental health in athletes: Where are the treatment studies? Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 781177. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.781177

- Frank, A. W. (2010). Letting stories breathe: A socio-narratology. University of Chicago Press.

- Frank, A. W. (2021). Socio-narratology and the clinical encounter between human beings. In F. Rapport & J. Braithwaite (Eds.), Transforming healthcare with qualitative research (pp. 25–32). Routledge.

- Goffman, E. (1959). The presentation of self in everyday life. Doubleday.

- Goffman, E. (1963). Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. Prentice-Hall.

- Gorczynski, P., Currie, A., Gibson, K., Gouttebarge, V., Hainline, B., Castaldelli-Maia, J. M., Mountjoy, M., Purcell, R., Reardon, C. L., Rice, S., & Swartz, L. (2021). Developing mental health literacy and cultural competence in elite sport. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 33(4), 387–401. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2020.1720045

- Gouttebarge, V., Castaldelli-Maia, J. M., Gorczynski, P., Hainline, B., Hitchcock, M. E., Kerkhoffs, G. M., Rice, S. M., & Reardon, C. L. (2019). Occurrence of mental health symptoms and disorders in current and former elite athletes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 53(11), 700–706. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2019-100671

- Gubrium, J., & Holstein, J. (2007). From the individual interview to the interview society. In J. Gubrium & J. Holstein (Eds.), Handbook of interview research (pp. 3–32). Sage.

- Gubrium, J., & Holstein, J. (2009). Analyzing narrative reality. Sage.

- Gulliver, A., Griffiths, K. M., & Christensen, H. (2012). Barriers and facilitators to mental health help-seeking for young elite athletes: A qualitative study. BMC Psychiatry, 12(1), 157. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-12-157

- Haddad, P., Haddad, I. (2015). Mental health stigma. British Association for Psychopharmacology (BAP). https://www.bap.org.uk/articles/mental-health-stigma/ [Accessed: 20220210].

- Haugen, E. (2022). Athlete mental health & psychological impact of sport injury. Operative Techniques in Sports Medicine, 30(1), 150898. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.otsm.2022.150898

- Hinshaw, S. P. (2010). The mark of shame: Stigma of mental illness and an agenda for change. Oxford University Press.

- Joy, E., Kussman, A., & Nattiv, A. (2016). 2016 update on eating disorders in athletes: A comprehensive narrative review with a focus on clinical assessment and management. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 50(3), 154–162. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2015-095735

- King, S. (2016). In defence of realist tales. In B. Smith & A. Sparkes (Eds.) The Routledge handbook of qualitative research in sport and exercise (pp. 291–301). Routledge.

- Lahman, M. K., Geist, M. R., Rodriguez, K. L., Graglia, P., & DeRoche, K. K. (2011). Culturally responsive relational reflexive ethics in research: The three Rs. Quality & Quantity, 45(6), 1397–1414. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-010-9347-3

- Lebrun, F., MacNamara, A., Rodgers, S., & Collins, D. (2018). Learning from elite athletes’ experience of depression. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 2062. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02062

- Moreland, J. J., Coxe, K. A., & Yang, J. (2018). Collegiate athletes’ mental health services utilization: A systematic review of conceptualizations, operationalizations, facilitators, and barriers. Journal of Sport and Health Science, 7(1), 58–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2017.04.009

- Newman, H. J., Howells, K. L., & Fletcher, D. (2016). The dark side of top level sport: An autobiographic study of depressive experiences in elite sport performers. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 868. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00868

- Papathomas, A. (2016). Narrative inquiry: From cardinal to marginal … and back? In B. Smith & A. Sparkes (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of qualitative research in sport and exercise (pp. 37–48). Routledge.

- Papathomas, A., & Lavallee, D. (2014). Self-starvation and the performance narrative in competitive sport. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 15(6), 688–695. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2013.10.014

- Pereira Vargas, M. L. F., Papathomas, A., Williams, T. L., Kinnafick, F.-E., & Rhodes, P. (2021). Diverse paradigms and stories: mapping ‘mental illness’ in athletes through meta-study. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 11, 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2021.2001840

- Plateau, C. R., Arcelus, J., Leung, N., & Meyer, C. (2017). Female athlete experiences of seeking and receiving treatment for an eating disorder. Eating Disorders, 25(3), 273–277. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640266.2016.1269551

- Plummer, K. (2001). Documents of life 2: A critical invitation to humanism. Sage.

- Poucher, Z. A., Tamminen, K. A., Kerr, G., & Cairney, J. (2021). A commentary on mental health research in elite sport. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 1, 60–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2019.1668496

- Reardon, C. L., Hainline, B., Aron, C. M., Baron, D., Baum, A. L., Bindra, A., Budgett, R., Campriani, N., Castaldelli-Maia, J. M., Currie, A., Derevensky, J. L., Glick, I. D., Gorczynski, P., Gouttebarge, V., Grandner, M. A., Han, D. H., McDuff, D., Mountjoy, M., Polat, A., … Engebretsen, L. (2019). Mental health in elite athletes: International Olympic Committee consensus statement (2019). British Journal of Sports Medicine, 53(11), 667–699. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2019-100715

- Riessman, C. K. (2008). Narrative methods for the human sciences. Sage.

- Rüsch, N., Angermeyer, M. C., & Corrigan, P. W. (2005). Mental illness stigma: Concepts, consequences, and initiatives to reduce stigma. European Psychiatry, 20(8), 529–539. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2005.04.004

- Russell, L. D. (2022). Life story interviewing as a method to co-construct narratives about resilience. The Qualitative Report, 27(2), 348–365. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2022.5183

- Schaal, K., Tafflet, M., Nassif, H., Thibault, V., Pichard, C., Alcotte, M., Guillet, T., El Helou, N., Berthelot, G., Simon, S., & Toussaint, J.-F. (2011). Psychological balance in high level athletes: Gender-based differences and sport-specific patterns. PLoS One, 6(5), e19007. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0019007

- Schubring, A., Mayer, J., & Thiel, A. (2019). Drawing careers: The value of a biographical mapping method in qualitative health research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 18, 160940691880930. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406918809303

- Sharp, M. L., Fear, N. T., Rona, R. J., Wessely, S., Greenberg, N., Jones, N., & Goodwin, L. (2015). Stigma as a barrier to seeking health care among military personnel with mental health problems. Epidemiologic Reviews, 37, 144–162. https://doi.org/10.1093/epirev/mxu012

- Sheehan, D. V., Lecrubier, Y., Sheehan, K. H., Amorim, P., Janavs, J., Weiller, E., & Dunbar, G. C. (1998). The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 59(20), 22–33.

- Sikes, P., & Goodson, I. (2017). What have you got when you’vr got a life story? In I. Goodson (Ed.), The Routledge international handbook on narrative and life history (pp. 60–71). Routledge.

- Smith, B. (2016). Narrative analysis in sportband exercise: How can it be done?. In B. Smith & A. Sparkes (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of qualitative research in sport and exercise (pp. 260–273). Routledge.

- Smith, B., & Sparkes, A. C. (2009a). Narrative inquiry in sport and exercise psychology: What can it mean, and why might we do it? Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 10(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2008.01.004

- Smith, B., & Sparkes, A. (2009b). Narrative analysis and sport and exercise psychology: Understanding lives in diverse ways. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 10(2), 279–288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2008.07.012

- Souter, G., Lewis, R., & Serrant, L. (2018). Men, mental health and elite sport: A narrative review. Sports Medicine - Open, 4(1), 57. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40798-018-0175-7

- Sparkes, A. (2002). Telling tales in sport & physical activity: A qualitative journey. Human Kinetics Press.

- Sparkes, A. C., & Smith, B. (2014). Qualitative research methods in sport, exercise and health: From process to product. Routledge.

- Sparkes, A. C., & Stewart, C. (2016). Taking sporting autobiographies seriously as an analytical and pedagogical resource in sport, exercise and health. Qualitative Research in Sport Exercise and Health, 8(2), 113–130. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2015.1121915

- Sparkes, A. C., & Stewart, C. (2019). Stories as actors causing trouble in lives: A dialogical narrative analysis of a competitive cyclist and the fall from grace of Lance Armstrong. Qualitative Research in Sport Exercise and Health, 11(4), 460–477. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1578253

- Tracy, S. J. (2010). Qualitative quality: Eight “big-tent” criteria for excellent qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry, 16(10), 837–851. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800410383121

- Vella, S. A., Schweickle, M. J., Sutcliffe, J. T., & Swann, C. (2021). A systematic review and meta-synthesis of mental health position statements in sport: Scope, quality and future directions. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 55, 101946. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2021.101946

- Wahto, R. S., Swift, J. K., & Whipple, J. L. (2016). The role of stigma and referral source in predicting college student-athletes’ attitudes toward psychological help-seeking. Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology, 10(2), 85–98. https://doi.org/10.1123/JCSP.2015-0025

- Walton, C. C., Rice, S., Hutter, R. V., Currie, A., Reardon, C. L., & Purcell, R. (2021). Mental health in youth athletes: A clinical review. Advances in Psychiatry and Behavioral Health, 1(1), 119–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypsc.2021.05.011

- Wilson, D., Bennett, E. V., Mosewich, A. D., Faulkner, G. E., & Crocker, P. R. E. (2019). ‟The zipper effect”: Exploring the interrelationship of mental toughness and self-compassion among Canadian elite women athletes. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 40, 61–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2018.09.006

- World Health Organization (2009). International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems: ICD-10. World Health Organization.

- Zielinski, M. J., & Veilleux, J. C. (2018). The Perceived Invalidation of Emotion Scale (PIES): Development and psychometric properties of a novel measure of current emotion invalidation. Psychological Assessment, 30(11), 1454–1467. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000584