Abstract

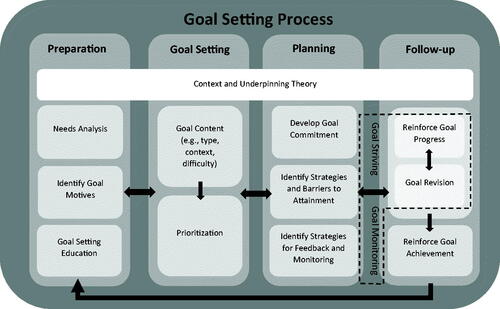

Goal setting is a widely used intervention by sport psychology practitioners (SPPs) and coaches aimed at enhancing the performance of their clients and athletes. Many mnemonics and acronyms have been suggested to follow when setting goals. These often recommend certain principles or characteristics, such as setting specific, measurable, achievable, realistic, and time-related (SMART) goals. Less attention has been paid to the process of goal setting, or specifically how a SPP or coach goes about setting goals. The purpose of this review was to provide an overview of current goal-setting processes by identifying, describing, and comparing models within the applied sport psychology and professional practice literature. Furthermore, we aimed to synthesize contextual information and critically evaluate stages presented in these processes, while providing further considerations for practitioners and future directions for researchers. Our review shows there are several commonalities in the suggested processes of setting goals and that the stages can be broadly categorized as: (i) preparation; (ii) goal setting; (iii) planning; and (iv) follow-up. Although goal setting should be applied in a dynamic, individualized, and contextually-appropriate manner, the review demonstrates the need for integration of additional evidence-based psychological strategies within each stage of the goal-setting process.

Lay summary: In this paper we provide an overview and synthesis of the different goal setting processes used by SPPs and coaches. We present ideas to consider when setting goals and direction for research in this area.

Implications for Practice

There are several stages that might be considered when setting goals with athletes.

Numerous additional interventions like helping athletes identify their values, monitoring goal progress, and revising/adjusting goals could take place as part of the process.

Goal setting, or the process through which people establish aims or objectives for their actions, is one of the most widely written about and researched interventions within the sport psychology literature. Because Locke and Latham’s (Citation1985) article suggested that goal setting could be as—if not more—effective in sport as it was in organizations, interest in the area has grown exponentially. A recent systematic review of sport psychology interventions revealed over 1,400 publications on goal setting and sport since 1985 (Lochbaum et al., Citation2022). Meta-analyses on goal setting in sport indicate that this intervention can have a positive effect on sport performance (Kyllo & Landers, Citation1995; Lochbaum & Gottardy, Citation2015; Williamson et al., Citation2022), with effect sizes generally being small-to-moderate (see Lochbaum et al., Citation2022). Given its performance-enhancing benefits, it is unsurprising that sport psychology practitioners (SPPs) use goal setting when working with individual athletes and teams (Barker et al., Citation2020).

Various mnemonics and acronyms, such as SMART (i.e., Specific, Measurable, Assignable, Realistic, and Time-related;Footnote1 Doran, Citation1981), are often used within professional practice literature (e.g., SMAART; Vealey, Citation2005; SMARTS; Weinberg & Gould, Citation2019) to guide SPPs when setting goals. Other educational resources focus on common goal-setting principles, like goal types (e.g., outcome, performance, and process goals—Hardy, Citation1997) and goal proximity (e.g., setting short-term and long-term goals—Butt & Weinberg, Citation2020). Although various principles are recommended for using goal setting in applied contexts, researchers indicate that goal setting is not a straightforward intervention to implement in sport. Youth athletes, for example, sometimes struggle to identify the differences between goal types, and some believe that goal setting could be detrimental to their performance and lead to disappointment should they not attain their goal (Bell et al., Citation2022). Maitland and Gervis (Citation2010) reported that goal setting in the context of youth soccer was far more complicated than following the SMART acronym and highlighted the influence of complex interactions between players and environmental factors (e.g., coaches, teammates). Furthermore, in a goal-setting intervention with a women’s collegiate soccer team, Gillham and Weiler (Citation2013) reflected on difficulties with goal evaluation and feedback.

In practice, goal setting is more complex than setting or being instructed to follow a goal and several steps within a specific process are needed to maximize the likelihood of success (Burton et al., Citation2001). Within the applied sport psychology literature, a range of goal-setting models have provided a description of the process of using goal setting in practice; that is, the stages a practitioner or coach might consider when implementing a goal-setting intervention in sport. Although a one-size-fits-all process is not necessarily desirable nor practical in the context of goal-setting interventions, given the vastness of, and substantial variability in, this literature, it could be useful for practitioners to have greater clarity as to what the core stages of a goal-setting intervention are, why (and when) these stages occur, and how these stages unfold and relate to one another. To date, reviews of goal setting in sport psychology have tended to focus on the effects of goals and specific goal-content on performance (e.g., Kyllo & Landers, Citation1995; Lochbaum & Gottardy, Citation2015) and psychological outcomes (Williamson et al., Citation2022), or the contents of theoretically-informed goal-setting interventions (Jeong et al., Citation2021), but no attempt has yet been made to synthesize extant literature on the process of goal setting in applied sport psychology practice.

Aims and approach

The purpose of this review was to provide an overview of the goal-setting processes in sport. We aimed to identify, describe, and compare goal-setting process models (i.e., models with detailed information on how goal setting would be implemented, with a clear set of interrelated stages) in the applied sport psychology literature and provide a synthesis of contextual and implementation information (i.e., stages) in these models. By doing so, we sought to bring clarity to the current understanding of the process of goal setting. This information could be useful for SPPs, coaches, athletes, educators, and students seeking to learn about and utilize goal setting. Furthermore, by synthesizing existing literature, the findings could also help to identify opportunities for further research and enable a critical evaluation of existing goal-setting process models. We identified relevant literature by: (i) screening reference lists of included studies, as well as lists of excluded records, in systematic reviews and meta-analyses on goal setting in sport (Jeong et al., Citation2021; Pop et al., Citation2021; Williamson et al., Citation2022); (ii) searching sport psychology journals; (iii) undertaking manual searches of professional practice literature and applied research; and (iv) emailing 10 certified, expert SPPs with experience in academic and applied settings. Data were synthesized drawing on guidelines for narrative synthesis (Popay et al., Citation2006).

Synthesis of goal setting process models in sport

Following our searches, we located 22 goal-setting process models in the professional practice (PP) literature (k = 15; see ) and applied research (k = 7; see ). The following sections detail the context and core components (i.e., stages) of each process. Each stage has been broadly labeled (e.g., needs analysis) so the variation of different strategies present in each is captured. Although presented in a series of stages, we urge readers from interpreting these in a linear process, as such parsimony masks the complexities of goal setting in real-world competitive sport. Where relevant, we include information where authors have connected various stages to one another to illustrate the interconnectedness of the various components.

Table 1. Professional practice literature goal setting process context, stages, and stated underpinning theory.

Table 2. Applied research goal setting process context, stages, and stated underpinning theory.

Context

Practitioner

Most processes were designed to be delivered by a coach (PP literature k = 7/15), SPP (PP literature k = 2/15; applied research k = 6/7), coach or SPP (PP literature k = 3/15; applied research k = 1/7), and a strength and conditioning practitioner (PP literature k = 1/15). Two models in the PP literature did not specify the intended practitioner.

Client

Suggestions for setting individual and team goals were most common in the PP literature (k = 7/15) followed by individual (k = 7/15) and team goals (k = 1/15). Although setting team and individual goals were mentioned, processes often focused on setting individual goals and only briefly mentioned setting team goals as well (e.g., Martens, Citation1991). Goal setting processes in the applied literature focused on setting individual goals (k = 7/7).

Goal-setting process

Preparation

Stated underpinning theory

Some literature explicitly referred to an underpinning theory that guided the process of goal setting (PP literature k = 7/15; applied research k = 4/7). Goal setting theory (GST; Locke & Latham, Citation1990), achievement goal theory (Nicholls, Citation1989), and competence motivation theory (Harter, Citation1978) were mentioned. Although an underpinning theory was stated in many models, in some cases it was unclear which theory authors were specifically referring to. Additionally, it was not always evident how stated theories influenced the process of goal setting (e.g., some processes were underpinned by multiple theories).

Needs analysis

All goal-setting models from the PP literature (k = 15/15) and three within the applied research (43%) included a needs analysis in the early stages of the goal-setting process. It was suggested that needs analyses could occur at the individual-level (e.g., Harwood, Citation2004), team-level (e.g., Widmeyer & Ducharme, Citation1997), or individual and team-level (e.g., Botterill, Citation1983), although this was determined by the purpose of goal setting (i.e., for individuals and/or teams). Regardless of the intended recipient, this stage shared several consistent characteristics. Most included some form of collaboration with the athlete (i.e., the coach or sport psychology professional facilitating the needs analysis), an analysis of the task (e.g., understanding what skills/abilities/actions athletes needed to perform to be successful in their sport), and the identification of any current strengths and weaknesses. Techniques like performance profiling were cited as tools to help guide this part of the process (e.g., Weinberg et al., Citation2005). Although most focused on conducting a needs analysis first, some suggested setting goals before analyzing what technical/psychological skills (Winter, Citation1995), along with physical capacities (Tod & McGuigan, Citation2001), were needed to reach them. In some cases, the need to consider individual differences was recognized (e.g., Symonds & Tapps, Citation2016). For instance, Weinberg and Gould (Citation2015) discussed the importance of identifying personality factors, such as perfectionism, achievement orientation, or developmental-level, when setting goals. Other individual difference factors to consider were the athlete’s goal orientation (i.e., task or ego—Harwood, Citation2004) and self-efficacy (Burton et al., Citation2001). Although a strong rationale was not always provided, a needs analysis was generally viewed as an important precursor to goal setting as it helped to identify areas that goal setting could target (e.g., perceived performance weaknesses) and determine how it could be tailored to each client (e.g., considering individual characteristics like goal orientation).

Identifying goal motives

Eight models (PP literature k = 6/15; applied research k = 2/7) included steps to help athletes identify their reasons for setting goals. Weinberg et al. (Citation2005), for example, suggested that it was important for athletes to determine their goal destination and clarify why they decided to strive toward any set goals. Activities to help athletes identify their reasons for setting goals included encouraging reflection on their own reasons for pursuing goals (e.g., Vealey, Citation2005), creating a long-term vision (e.g., Burton & Raedeke, Citation2008), and writing mission statements (e.g., Wanlin et al., Citation1997).

Goal-setting education

Education about goal setting was a component of some processes (PP literature k = 5/15; applied research k = 5/7). Across the models, it was suggested that clients should be informed about: the benefits of setting goals; how goals work; different goal types and goal setting principles (i.e., goal difficulty, goal proximity); common mistakes made when setting goals; evidence about the effectiveness of goal setting; and how to set effective goals. Although not every model that included education articulated how this could be carried out, some goal-setting processes specified how athletes should be educated about goal setting. Burton and Raedeke (Citation2008) recommended an education phase should happen within a larger process of developing goal-setting skills (i.e., education phase—acquisition phase—implementation phase) through meetings with athletes focusing on general goal setting education, enhancing awareness of how goal setting has helped them, and strengths or weaknesses in their ability to set goals (i.e., do they set unrealistic goals?). A workbook containing examples and goal setting checklists was also suggested to deliver this type of education (Wanlin et al., Citation1997).

Goal setting

Establish goal content

Many factors that practitioners should consider when setting goals were discussed in the different processes.

Measurability

Fourteen processes (PP k = 11/15, applied research k = 3/7) recommended setting measurable goals to provide expectations for athletes, set evaluative performance criteria, and enable progress tracking over time, thus allowing feedback on goal progress to be obtained. Suggested methods to make goals measurable included: identifying objective (e.g., Martens, Citation1991) and subjective performance measures (e.g., Burton & Raedeke, Citation2008); establishing self-evaluation criteria based on mastery, previous performance, or normative criteria (e.g., Weinberg et al., Citation2005); and setting goals in quantifiable terms (e.g., Gano-Overway & Carson Sackett, Citation2021).

Goal type/focus

Nineteen models (PP literature k = 13/15, applied research = 6/7) referred to the need to consider goal type/focus. Processes commonly included different combinations of outcome, performance, and process goals, with eight processes including all three. Martens (Citation1991) suggested that focus should be directed toward performance goals due to the enhanced controllability athletes have over this goal type. Others advocated for setting and focusing on process goals on the assumption that the successful achievement of process goals usually leads to the achievement of performance goals (e.g., Symonds & Tapps, Citation2016), which in turn are critical to the achievement of outcome goals (e.g., Vealey, Citation2005). Setting technical, tactical, physical, mental, and environmental (e.g., enjoyment) goals was also suggested to ensure goal setting was comprehensive (e.g., Botterill, Citation1983).

Goal context

The context for goal setting was referred to in most processes (PP literature k = 7/15, applied research k = 6/7). These models suggested setting goals in a combination of contexts, including during practice and during competition, or practice only. The context goals targeted was considered important as they serve different functions (Burton & Raedeke, Citation2008). Goals set in practice were typically proposed to enhance motivation during training, while also allowing athletes to focus on making improvements (e.g., Weinberg & Gould, Citation2015). In contrast, competition goals were identified as ways to help athletes prepare to perform (e.g., Weinberg et al., Citation2005). Although the context for goal setting generally revolved around performance, South (Citation2004) suggested setting lifestyle goals (e.g., anger management), while career growth, material, self-esteem, and social significance goals were also advocated for (Vysochina & Vorobiova, Citation2017).

Goal difficulty

Most goal-setting processes (PP literature k = 12/15, applied research k = 4/7) referred to goal difficulty. There was some consensus that goals should be difficult enough to foster effort and persistence, but not so challenging that non-achievement would reduce confidence, perceptions of competence, and/or motivation. Vealey (Citation2005), for example, stated that “Aggressive goals make athletes stretch and push their limits. However, at the same time, if goals are ridiculously unrealistic, they are not credible goals at all, and thus do not provide direction or inspiration” (p. 156). The terminology used to describe goal difficulty varied and included: “realistic” (Symonds & Tapps, Citation2016); “challenging but realistic” (Weinberg et al., Citation2005); “challenging but achievable” (Winter, Citation1995); “moderately difficult” (Burton & Raedeke, Citation2008); and “difficult but realistic” (Widmeyer & Ducharme, 1997). Adapting the difficulty of the goal, based on the performance context, was suggested. For example, Burton et al. (Citation2001) discussed optimizing goal difficulty by setting challenging goals for practice (e.g., to challenge athletes to improve) and realistic goals for competition (e.g., to help reduce stress and enhance confidence). Winter (Citation1995) recommended setting difficult goals for more confident athletes and making them easier for those with less confidence.

Goal specificity

Fifteen goal-setting processes (PP literature k = 12/15, applied research k = 3/7) recommended setting specific goals. Reasons for setting specific goals included that when compared to “do-your-best goals,” specific goals were considered more effective at changing behavior (Weinberg & Gould, Citation2015) and more powerful in enhancing motivation and performance (Weinberg et al., Citation2005). Moreover, it was suggested that specific goals increase the precision of athlete behavior and more clearly communicate expectations, thus contrasting to “general” goals (Martens, Citation1991).

Goal valence

Only two goal-setting processes, both in the professional practice literature, incorporated goal valence. Burton et al. (Citation2001) outlined the potential benefits of positively-focused goals (e.g., taking two putts on a golf hole rather than trying not to take three putts) including having athletes focus on striving toward their desired objective. The authors, however, did not make any suggestions in their model as to how this would be implemented and suggested more research in this area was needed. Likewise, Tod and McGuigan (Citation2001) advocated for the use of positively-valenced goals and suggested negatively-valenced goals (e.g., “I do not want to fail this lift”) can trigger “negative” self-talk that could be detrimental to performance.

Goal proximity

All goal-setting processes contained information about goal proximity. In general, the models focused on setting only short-term goals (e.g., Martens, Citation1991) or a combination of short-term and long-term goals (e.g., Tod, Citation2014). Short-term goals concerned goals that were set daily (e.g., Weinberg et al., Citation2005) or no longer than six weeks ahead (e.g., Burton & Raedeke, Citation2008). The temporal span of long-term goals varied from one year to four-year Olympic cycles (Vysochina & Vorobiova, Citation2017). Some models included an additional “intermediate” or “medium” goal positioned between a short-term and long-term goal (e.g., Winter, Citation1995). Martens (Citation1991) recommended that short-term goals should only be employed as specific, challenging, and realistic long-term goals could be difficult due to the degree of uncertainty involved in achieving goals over a longer period. Others suggested that by combining short-term and long-term goals, the short-term goal could provide necessary direction or incremental steps (e.g., Gano-Overway & Carson Sackett, Citation2021) toward achieving long-term goals, the latter of which they suggested should be set first. Adding a further proximal layer, South (Citation2004) proposed that setting a series of short-term goals (microcycle) would create “feed-in loops” for intermediate goals (mesocycle), which, when achieved, were proposed to aid longer-term goal achievement (macrocycle).

Prioritization

Ranking or prioritizing set goals was included as a stage in eight processes (PP literature k = 7/15, applied research k = 1/7). This step was key to allowing athletes to concentrate and narrow their focus on their most important goal(s) (e.g., Botterill, Citation1983). Ranking goals in order of importance was one strategy used to achieve this (e.g., Burton & Raedeke, Citation2008). More sophisticated strategies to determine goal ranking included using a framework for goal prioritization. Specifically, Symonds and Tapps (Citation2016) proposed a 2 × 2 framework consisting of two separate continua: goal performance-benefit (ranging from high performance-benefit to low performance-benefit) and goal-implementation effort (ranging from easy implementation to difficult implementation). Based on this framework, the authors suggested that: goals with high performance benefits that are both difficult and easy to implement should be focused on immediately; goals providing low performance benefits and that are difficult to implement should be revised; and goals with low performance benefits and that are difficult to implement should be removed or reconsidered.

Planning

Develop commitment

A common component of nearly all processes in the PP literature (k = 14/15) and applied research (k = 7/7) was the need to enhance goal commitment to increase the chances of goal attainment. Suggested methods for fostering goal commitment included enabling athletes to set their own goals or collaborating with them in the goal-setting process (Widmeyer & Ducharme, Citation1997), providing social support (Burton & Raedeke, Citation2008), athletes sharing their goals with others (Gregg et al., Citation2004), and displaying goals publicly (Hampson & Harwood, Citation2016). Related to an aforementioned category, Vealey (Citation2005) mentioned identifying and athlete’s purpose as a way to enhance goal commitment.

Identify achievement strategies and barriers to attainment

Nineteen processes (PP literature k = 13/15, applied research k = 6/7) included a step outlining goal achievement strategies, with 10 also including a stage where barriers to goal attainment were discussed (PP literature k = 8/15, applied research k = 2/7). Modeling behaviors consistent with goals (i.e., encouraging an athlete after a mistake for a team trying to be more positive; e.g., Botterill, Citation1983), in addition to developing behavioral plans to help facilitate goal attainment (i.e., shooting 50 free throws after practice for an athlete looking to improve their free-throw percentage; e.g., Vealey, Citation2005), were both suggested. Incorporating goals into coaching plans at practice to give the athlete time to work toward goal attainment was also advocated for (e.g., Martens, Citation1991). Within the applied research, additional mental skills (e.g., imagery, self-talk) were used to help athletes achieve their goals (e.g., Wanlin et al., Citation1997).

Identifying barriers to goal attainment was another important step, with this stage used to understand what may stop an athlete from achieving any set goals. Barriers could be internal (e.g., lack of confidence) or external (e.g., lack of time to practice; Burton et al., Citation2001). They may also include the athlete’s potential, opportunities to practice, or commitment (Weinberg & Gould, Citation2015). Although there were no clear strategies outlined to identify and evaluate barriers to goal attainment in any model, it was suggested that an analysis of what is preventing athletes from achieving their goals could occur in this step (e.g., Burton & Raedeke, 2008). Moreover, it was also suggested that explaining some of the common goal-setting mistakes could be used to remove potential barriers, such as setting “ineffective” goals (e.g., McCarthy, Jones, Harwood, & Davenport, Citation2010).

Identify strategies for feedback and monitoring

The inclusion of feedback and monitoring throughout the goal-setting process was evident in most models within the PP literature (k = 14/15) and applied research (k = 7/7). A common view was that feedback facilitated the evaluation of goal progress that could lead to goal revision/adjustment (e.g., Burton & Raedeke, Citation2008). Weinberg et al. (Citation2005) suggested by evaluating their own progress, athletes could enhance their self-confidence and intrinsic motivation if they were achieving their goals, and increased motivation to work harder if they were not. Mechanisms for obtaining feedback and monitoring progress included periodic goal-evaluation meetings with athletes (e.g., Burton & Raedeke, Citation2008), publicly displaying progress (e.g., Widmeyer & Ducharme, Citation1997), diaries (e.g., McCarthy, Jones, Harwood, & Davenport, Citation2010; Winter, Citation1995), or self-monitoring logs (e.g., Pierce & Burton, Citation1998). Goal-evaluation cards were also used as a method to create reflection and discussion on reasons why an athlete may or may not have achieved their goal (e.g., Vealey, Citation2005). Constant feedback used throughout the period of goal striving was also mentioned to bolster goal commitment (Harwood, Citation2004).

Follow-up

Goal revision

Twelve models (PP literature k = 10/15, applied research k = 2/7) included a stage involving revision/adjustment. This was often described as a step that followed goal monitoring (i.e., after a period an athlete had worked toward a goal) and was intended to allow athletes/coaches to adjust or revise goals depending on the progress that was made toward them (e.g., Botterill, Citation1983). Once goal striving had begun, various reasons for goal adjustments were suggested, including injury, weather, or opposition (e.g., Burton & Raedeke, Citation2008), as well as performance slumps or plateaus (e.g., Vealey, Citation2005). If a goal was deemed too difficult, it could be modified to make it achievable, whereas if a goal was attained, a more challenging goal could be set. Suggested outcomes of goal revision (i.e., making a goal easier) included avoiding discouragement and decreased effort (Weinberg et al., Citation2005). Meeting with athletes, evaluating and self-monitoring logs, and engaging in problem solving were suggested methods to facilitate goal revision/adjustment between performances (e.g., Gano-Overway & Carson Sackett, Citation2021). In addition to working with a strength and conditioning coach to readjust unrealistic goals, Tod and McGuigan (Citation2001) recommended revising the training program.

Reinforce goal progress/reinforce goal achievement

Seven processes (PP literature k = 6/15, applied research k = 1/7) contained a component related to reinforcing goal progress or reinforcing goal achievement. Reinforcing goal progress typically occurred once the goal was being worked toward (i.e., goal striving) and before the goal was revised or achieved. Reinforcing goal achievement happed once the goal was obtained. Desired outcomes of reinforcing goal achievement revolved around enhancing athletes’ motivation and encouraging them to set new goals and continue any new, adaptive goal-directed behaviors (e.g., Burton & Raedeke, Citation2008). Proposed methods for goal reinforcement included rewarding progress and the achievement of goals (e.g., Martens, Citation1991), as well as reinforcing goal commitment and effort (Gano-Overway & Carson Sackett, Citation2021). At the team level, Widmeyer and Ducharme (Citation1997) suggested accomplishments may be rewarded through public praise.

Critical reflections on the process of goal setting in sport

The purpose of this review was to identify, describe, and compare goal-setting processes in the sport psychology literature and provide a synthesis of contextual and implementation information (i.e., stages) in these models (see for a synthesized goal-setting process). To interpret findings of this review what follows are critical reflections concerning the components of goal setting processes in sport psychology. As indicated by the bidirectional arrows between stages in , our intention is not to suggest that the goal-setting process stages should be viewed as linear, prescriptive, or used in a criteriological, checklist fashion. Instead, we seek to contextualize the components of the goal-setting processes identified in relation to contemporary sport psychology literature and offer suggestions that could be useful for practitioners seeking to use goal setting in their future applied practice, as well as highlighting gaps for future research in this area.

Goal setting processes in applied sport psychology and considerations for practice

The context of goal setting

Goal setting was described primarily as a process that could be delivered by a SPP or coach, with one process aimed specifically at strength and conditioning practitioners (Tod & McGuigan, Citation2001). Although not exclusively focused on goal setting, no significant differences in intervention effectiveness have been shown for teambuilding interventions delivered directly (e.g., by a SPP) versus indirectly (e.g., by a SPP delivering the intervention to a coach who then delivers the intervention) to athletes (Martin et al., Citation2009). Indeed, researchers have suggested that including a social agent (e.g., coach) within an intervention (e.g., goal setting) can enhance its effectiveness (Brown & Fletcher, Citation2017). It is important, however, to ensure goal-setting processes include enough information for the intended practitioner (e.g., coach) to be able to implement this in practice, especially since some have highlighted limited knowledge in this area (e.g., strength and conditioning practitioners; Quartiroli et al., Citation2022). Additionally, it should also be known that implementing interventions (i.e., goal setting) will be context-driven (Storm & Larsen, Citation2020) as practice is influenced by interactions between practitioners, clients, and cultural/sub-cultural contexts (Stambulova & Schinke, Citation2017). In this case, the effectiveness of goal setting is less dependent on who is delivering the intervention, but how this individual tailors their approach to the unique needs of the client.

Only one process focused specifically on team goal-setting (Widmeyer & Ducharme, Citation1997), although models advocated for setting individual and team goals often suggested setting team goals by following a similar process to individual goal-setting. Research indicates the positive influence of individual goals on sport performance (Kyllo & Landers, Citation1995; Lochbaum & Gottardy, Citation2015; Williamson et al., Citation2022) and that team goal setting is an effective teambuilding strategy in sport (Martin et al., Citation2009). Nevertheless, findings concerning the social-psychological effects of team goal-setting interventions are somewhat equivocal. For instance, team goal-setting has been shown to increase collective efficacy (Durdubas & Koruc, Citation2022), yet it has also produced both increased (Rovio et al., Citation2012) and decreased (Durdubas et al., Citation2020) perceptions of team cohesion. In explaining their findings, Durdubas et al. (Citation2020) suggested that focusing on task objectives could inadvertently promote social comparison and interpersonal competition between teammates, thus creating an ego-involving motivational climate and contributing to lower perceptions of cohesion. Guidelines designed specifically for setting team goals are therefore important as certain nuances should be considered when setting goals at this level. Furthermore, practitioners should also consider how team goal-setting and individual goal-setting are implemented simultaneously, especially as such an approach might be advised when seeking to target social-psychological constructs (e.g., teamwork—McEwan & Beauchamp, Citation2020).

Preparing to set goals

Performance profiling was commonly identified as a tool that SPPs or coaches could use to facilitate a needs analysis. This technique exhibits the desired characteristics of a needs analysis identified in many of the goal-setting models (e.g., collaboration between coach/athlete, analysis of key task specific characteristics) and has been identified as a segue into goal setting (see Bird et al., Citation2021, for a review of performance profiling methods). There are, however, some caveats described in the performance profiling literature that were also demonstrated within the goal-setting processes included in the current review (e.g., possessing knowledge related to the mental, physical, and requirements of the sport). In addition, gathering information related to some of the goal characteristics within the goal-setting needs analysis is important. Knowing timeframes for goal completion and the current levels of the performer, for example, would influence goal proximity and goal difficulty. It is also important for a practitioner to understand the underpinning theory they endorse for goal setting as this will influence the type of information collected. As Harwood (Citation2004) approached goal setting from an achievement goal theory (Nicholls, Citation1989) perspective, the needs analysis revolved around assessing task and ego orientations of the athlete and their sources of achievement goals. Goal-setting styles (e.g., performance, success, and failure-oriented) and situational variables (e.g., performance expectancies, situation type, activity importance, and task complexity) should also be considered (Burton & Weiss, Citation2008).

In addition to a needs analysis, some goal setting processes included a stage where athletes attempted to understand their reasons for pursuing goals through identifying their long-term vision or purpose, with this often being achieved through reflection or the writing of mission statements. Although not specifically mentioned in any of the goal-setting processes, having an athlete identify their long-term vision or purpose can be connected theoretically to the literature on goal motives (Healy et al., Citation2018). The self-concordance model (Sheldon & Elliot, Citation1999), for example, proposes the benefits of autonomous goal motives (i.e., intrinsic or identified motivational regulations reflecting the interests or values of the individual) versus controlled goal motives (i.e., introjected or external motivational regulations driven by anxiety, guilt, expectancy rewards, or punishments). Support for the self-concordance model in sport has been found (Healy et al., Citation2016), yet little information has been presented explicitly within the PP literature to explain how to facilitate goal setting using autonomous motives. Some researchers have stated that having athletes/teams identify their values is a way to understand how (i.e., through guiding decisions and actions) they can arrive at their destination (e.g., outcome goals; Shoenfelt, Citation2011). Therefore, through the goal-setting process, it may be important to help athletes identify the underpinning values of their goals as part of defining their mission or purpose, and then subsequently setting goals congruent with these.

Education was another common stage preceding the setting of goals. This intervention component has roots in the early psychological skills training (PST) literature, with Vealey (Citation1988) framing goal setting as a method used within PST, an approach to practice underpinned by the belief that sport psychology skills are learnable. Weinberg and Gould (Citation2015) suggest there are three phases to PST—education, acquisition, and practice. Educating athletes about the processes involved in goal setting holds additional importance as one of the ultimate outcomes of PST is the development of self-regulation (Weinberg & Williams, Citation2015). Unsurprisingly, many education stages in goal-setting processes focused on teaching athletes about effective goal setting by helping them understand goal-setting principles (e.g., goal types, goal difficulty, and goal proximity) that are included in the stage of setting goals. Goal-setting education therefore may be considered an important step in the process of goal setting because it helps clients understand how setting goals influence performance and provides them with the skills to set goals autonomously. To further enhance self-regulation, educational stages of goal-setting could focus on teaching athletes content from other stages of the process identified in this review (e.g., conducting their own needs analysis, effective goal characteristics, ways to monitor goal progress).

Setting goals

A wide variety of goal characteristics were presented within goal-setting processes, including specificity, measurability, focus, context, difficulty, valence, and proximity. Although only a few goal-setting models included in the review explicitly stated they were specifically guided by theory (e.g., Harwood, Citation2004; Widmeyer & Ducharme, Citation1997), most models aligned with key principles concerning goal content advocated within early versions of goal setting theory (Locke & Latham, Citation1990), as the goals used and/or suggested were generally specific (i.e., single end-state reference point), challenging goals. Providing a comprehensive overview of the effects of qualitatively different goals in sport is not the aim of the current article, but the reliance on specific, challenging goals should be questioned for several reasons. First, reviews of empirical evidence in sport and exercise indicate that specific goals are not necessarily better than nonspecific goals (e.g., do-your-best) for enhancing performance (Jeong et al., Citation2021). Furthermore, meta-analytical evidence in sport and exercise indicates that specific, difficult goals were less effective than specific, moderate goals (Kyllo & Landers, Citation1995), which were recommended by several authors (e.g., Widmeyer & Ducharme, 1997). Second, GST originally advocated the use of specific, challenging goals (Latham & Locke, Citation1991), yet this theory has evolved substantially, with one of the most notable changes being the distinction between learning and performance goals (Locke & Latham, Citation2013), which as yet have received very little attention in sport. Further elaboration on the aforementioned points are beyond the scope of the current review (see Jeong et al., Citation2021, for additional reviews), but we suggest that based on the continued and widespread advocation for, and use of, specific, difficult goals, there is a need for models of goal setting in sport psychology practice to go beyond a one-size-fits-all approach to goal setting in relation to specificity and challenge. Furthermore, for practitioners seeking to be guided by GST, it is crucial to consider more recent updates in this theory and to ensure that moderators of goals are considered (Locke & Latham, Citation2013).

Although most processes advocated for setting multiple goals, few specified how many goals should be set and retained. Research used to help SPPs identify an optimal number of goals is lacking in this area. Ways to prioritize goals were included, however, with ranking them in order of importance a popular approach (e.g., Martens, Citation1991). Symonds and Tapps (Citation2016) provided the most comprehensive method of goal prioritization by using a 2 × 2 framework to allow athletes to explore the potential performance benefit and implementation of each goal. A need for goal ranking/prioritization stage can potentially be prevented, or minimized, based on the quality of the needs analysis. For example, identifying specific areas (i.e., weaknesses) that require attention in the early stages of the process may stop athletes from setting goals too broadly.

Preparing for goal achievement

A stage that aims to foster goal commitment, which refers to an individual’s determination to reach a goal (Locke & Latham, Citation1990), was present across all processes. The relationship between goal commitment and goal performance is complex and moderated by goal difficulty. When difficult goals are set, a stronger relationship is seen between goal commitment and performance, compared to goals with lower difficulty (Klein et al., Citation1999). Numerous ways to develop high goal-commitment have been suggested, such as having athletes participate in goal setting, incentives for goal achievement, and public goal disclosure (Weinberg, Citation2013). Rather than just providing athletes autonomy in the process of setting goals, Kingston and Wilson (Citation2008) suggested that having athletes take ownership of the process may be more effective. Linking this back to an earlier stage in the goal-setting process, helping athletes identify their mission or purpose may increase goal commitment. Some other ways of fostering goal commitment revolved around the social components of sharing goals with others or posting goals publicly, yet there is little research in this area (see Ward, Citation2011, for overview).

Most goal-setting processes included a stage of identifying achievement strategies for goal attainment and some contained a stage related to recognizing barriers to goal achievement. Although there were no clear strategies outlined to assess barriers to goal attainment, Burton and Raedeke (Citation2008) suggested an analysis of what is stopping athletes from achieving their goals. Achievement strategies included behavioral plans, like serving a certain number of tennis balls per practice session, whereas barriers to goal achievement revolved around internal factors (i.e., lack of confidence), external factors (i.e., lack of time), or the goal-setting process itself (e.g., lack of feedback). Some applied research that included strategies to aid goal attainment used additional mental skills like imagery and self-talk to do this. The practice of incorporating additional mental skills within goal setting is theoretically grounded. The self-regulation goal-setting model, for example, emphasizes the importance of other mental skills in aiding goal achievement (Kirschenbaum, Citation1987), but packaging mental skills together (e.g., goal setting and imagery) has been reported as problematic. Researchers have suggested it takes time for athletes to master skills effectively (Gregg et al., Citation2004) and it becomes difficult to assess the contributions of individual components to goal setting programs on goal setting effectiveness (e.g., Wanlin et al., Citation1997). Nevertheless, multimodal intervention packages have been shown to be effective (Brown & Fletcher, Citation2017).

A stage related to feedback and monitoring was important as this provided the information needed to recognize goal attainment, or if a goal should be refined or revised. This stage within the process was also closely linked to some of the goal-setting characteristics. For example, setting measurable goals was desired so performance could be tracked, and progress fed back to the athlete. Meta-analytic evidence from the general psychology literature indicates goals plus feedback are better than just goals, and that the value of feedback is increased when the goal is more challenging (Neubert, Citation1998), when outcomes are made public, and when goals are physically recorded (Harkin et al., Citation2016).

Two underpinning mechanisms explain how feedback and goals are effective. First, feedback provides an opportunity for a self-regulatory response to discrepancy—feedback highlights the discrepancy between the performance and goal, which influences motivation, persistence, and effort (Locke, Citation1968). Second, feedback provides information on, and allows evaluation of, the strategies or behaviors used when striving toward a goal (Earley et al., Citation1990). Some goal-setting processes identified within this review mention general ways to evaluate performance using measurable goals, while some show more detailed strategies such as keeping a performance log or diary where athletes keep information, such as performance records. Research on self-monitoring in athletes has shown this intervention has a positive influence in the short-term (around three weeks), with athletes who self-monitor displaying greater adherence to training, before behaviors regress to pre-intervention levels (Young et al., Citation2009).

Following up

Goal revision/adjustment is a central factor underlying the decision to persist with or adjust a goal in the direction and extent of a goal-performance discrepancy (i.e., the difference between goal progress and the goal; Donovan & Williams, Citation2003). Although never giving up and resisting the urge to quit are commonly glorified in sport, continuing to pursue an unattainable goal can be detrimental (Ntoumanis et al., Citation2014). In such situations, goal disengagement can represent an adaptive self-regulatory response (Brandstätter & Bernecker, Citation2022) and can potentially protect individuals against some of the unpleasant, dysfunctional emotional consequences of perceived goal failure, such as depressive mood, guilt, or shame (Wrosch & Scheier, Citation2020). Consistent with this perspective, in most cases, the authors of the goal-setting models referred to the potential need for an athlete to adjust a goal when an athlete was unlikely to achieve their goal and/or they had encountered an obstacle. Such advice aligns with theoretical propositions (e.g., Ntoumanis & Sedikides, Citation2018) and empirical evidence (e.g., Ntoumanis et al., Citation2014) concerning the potentially protective effects of goal disengagement. Given that athletes regularly encounter difficulties en route to goal attainment, it is important for practitioners to be aware of the importance of considering goal-revision processes in the follow-up stage of the goal-setting process and during goal striving (e.g., continually moving back and forth through rewarding progress and adjusting goals until the goal is achieved). Furthermore, although not as widely discussed, practitioners may also consider how they navigate situations when an athlete is exceeding their intended goal, a scenario in which they may wish to revisit earlier steps in the goal-setting process.

Positive reinforcement was identified in some goal-setting processes. This was used to promote continued striving toward a goal or reward goal achievement. Reinforcing commitment and effort has been noted as particularly important as these are factors which athletes have control over. Positive reinforcement can signal to the athlete how they have met a certain standard of excellence, fostering increased self-reinforcement and intrinsic motivation (Smith, Citation2015). Tangible rewards used as a reinforcer, however, can potentially undermine intrinsic motivation if these rewards are presented in a controlling (autocratic coaching style), rather than informational (autonomy supportive) way (Bartholomew et al., Citation2009). It therefore becomes important that SPPs and coaches understand how to use reinforcement appropriately.

Future directions for Goal setting research

Findings highlight several gaps in the literature and future directions for research in this area. First, goal-setting processes were described in a universal fashion and there was little evidence of considerations when working with specific populations, such as youth athletes. As researchers have suggested youth athletes could benefit from education on psychological skills that are aligned with their developmental level (McCarthy, Jones, Harwood, & Olivier, Citation2010), further research with this population is warranted. Second, some processes included goals that athletes should target in other areas of their life in addition to performance (e.g., lifestyle goals). Although the references to non-sport-performance goals are encouraging given the increased emphasis placed on holistic athlete-support practices (Chambers et al., Citation2019), there is little research within the sport psychology literature that focuses on understanding the effectiveness of goals targeting such behaviors or how concomitant sport and lifestyle goals can be set in practice. Third, one strategy that did not feature in models of goal setting identified in the current review was mental contrasting with implementation intentions (MCII; Oettingen, Citation2012). This metacognitive strategy involves the weighing up of current and future goal-status and the subsequent development of relevant implementation intentions (i.e., if-then plans). Although evidence suggests this intervention facilitates goal attainment (Wang et al., Citation2021), little attention has been directed toward understanding the effects of MCII within the context of applied sport psychology. Fourth, feedback and monitoring were identified as an important part of the goal-setting process. Although numerous ways to elicit feedback and enhance monitoring between performances have been created for SPPs (e.g., post-event reflection; Chow & Luzzeri, Citation2019), research assessing the effectiveness of these tools is limited. Finally, goal-revision processes outlined in the review were positioned between performances and, therefore, most likely through interactions between a SPP/coach and an athlete. This perspective, however, overlooks evidence indicating that athletes revise or change their goals within performances (e.g., Swann et al., Citation2017), a process that will often occur without the support of a practitioner or coach. To date, little attention has been directed toward how practitioners may prepare athletes to make decisions surrounding goal striving within performance and the types of self-regulatory strategies that may (or may not) be used depending on such decisions.

Conclusion

The purpose of this review was to identify, describe, and compare goal-setting processes in the sport psychology literature. We aimed to provide a critical synthesis of the common stages included within these processes in addition to presenting applied considerations for SPPs, while also outlining future directions for researchers in this area. Findings from this review show there are several similar stages that occur frequently across many goal setting processes and that the desired outcomes intended to be achieved at each stage can be done so in a variety of different ways. There are, however, numerous evidence-based techniques that are often overlooked within each process that could be integrated into the applied goal-setting practice of SPPs. Furthermore, there are several avenues for future research within this area that could help to bolster guidelines for the implementation of more effective goal-setting processes.

Notes

1 These are the original terms used by Doran (Citation1981). Swann et al. (Citation2022) point out that in the context of physical activity, the SMART acronym is most commonly interpreted as representing specific, measurable, attainable, realistic, and time-bound.

References

- Barker, J. B., Slater, M. J., Pugh, G., Mellalieu, S. D., McCarthy, P. J., Jones, M. V., & Moran, A. (2020). The effectiveness of psychological skills training and behavioral interventions in sport using single-case designs: A meta regression analysis of the peer-reviewed studies. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 51, 101746. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2020.101746

- Bartholomew, K. J., Ntoumanis, N., & Thøgersen-Ntoumani, C. (2009). A review of controlling motivational strategies from a self-determination theory perspective: Implications for sports coaches. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 2, 215–233. https://doi.org/10.1080/17509840903235330

- Bell, A. F., Knight, C. J., Lovett, V. E., & Shearer, C. (2022). Understanding elite youth athletes’ knowledge and perceptions of sport psychology. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 34, 155–177. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2020.1719556

- Bird, M. D., Castillo, E. A., & Luzzeri, M. (2021). Performance profiling: Theoretical foundations, applied implementations and practitioner reflections. Journal of Sport Psychology in Action, 12, 213–225. https://doi.org/10.1080/21520704.2020.1822970

- Botterill, C. (1983). Goal setting for athletes with examples from hockey. In G. L. Martin, & D Hrycaiko (Eds.), Behavior modification and coaching: Principles, procedures, and research. Charles C. Thomas.

- Brandstätter, V., & Bernecker, K. (2022). Persistence and disengagement in personal goal pursuit. Annual Review of Psychology, 73, 271–299. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-020821-110710

- Brown, D. J., & Fletcher, D. (2017). Effects of psychological and psychosocial interventions on sport performance: A meta-analysis. Sports Medicine, 47(1), 77–99. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-016-0552-7

- Burton, D. (1989). Winning isn’t everything: Examining the impact of performance goals on collegiate swimmers’ cognitions and performance. The Sport Psychologist, 3, 105–132. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.3.2.105

- Burton, D., & Raedeke, T. D. (2008). Sport psychology for coaches. Human Kinetics.

- Burton, D., & Weiss, C. (2008). The fundamental goal concept: The path to process and performance success. In T. S. Horn (Ed.), Advances in sport psychology (3rd ed., pp. 339–376). Human Kinetics.

- Burton, D., Naylor, S., & Holliday, B. (2001). Goal setting in sport: Investigating the goal effectiveness paradox. In R. N. Singer, H. A. Hausenblas, & C. M. Janelle (Eds.), Handbook of sport psychology (2nd ed., pp. 497–528). John Wiley & Sons.

- Butt, J., & Weinberg, R. (2020). Goal-setting in sport. In D. Hackfort & R. Schinke (Eds.), The Routledge international encyclopedia of sport and exercise psychology: Applied and practical measures (Vol. 1; pp. 333–342). Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

- Chambers, T. P., Harangozo, G., & Mallett, C. J. (2019). Supporting elite athletes in a new age: experiences of personal excellence advisers within Australia’s high-performance sporting environment. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11, 650–670. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1605404

- Chow, G. M., & Luzzeri, M. (2019). Post-event reflection: A tool to facilitate self-awareness, self-monitoring, and self-regulation in athletes. Journal of Sport Psychology in Action, 10, 106–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/21520704.2018.1555565

- Donovan, J. J., & Williams, K. J. (2003). Missing the mark: Effects of time and causal attributions on goal revision in response to goal-performance discrepancies. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(3), 379–390. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.3.379

- Doran, G. T. (1981). There’s a SMART way to write management’s goals and objectives. Management Review, 70, 35–36.

- Durdubas, D., & Koruc, Z. (2022). Effects of a multifaceted team goal-setting intervention for youth volleyball teams. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, Advanced Online Publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2021.2021564

- Durdubas, D., Martin, L. J., & Koruc, Z. (2020). A season-long goal-setting intervention for elite youth basketball teams. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 32, 529–545. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2019.1593258

- Earley, P. C., Northcraft, G. B., Lee, C., & Lituchy, T. R. (1990). Impact of process and outcome feedback on the relation of goal setting to task performance. Academy of Management Journal, 33, 87–105. https://doi.org/10.5465/256353

- Gano-Overway, L., & Carson Sackett, S. (2021). Let’s get smart and set goals to ASPIRE. Journal of Sport Psychology in Action,2021, 1–15. Advanced online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/21520704.2021.2007192

- Gillham, A., & Weiler, D. (2013). Goal setting with a college soccer team: What went right, and less-than-right. Journal of Sport Psychology in Action, 4, 97–108. https://doi.org/10.1080/21520704.2013.764560

- Gregg, M. J., Hrycaiko, D., Mactavish, J. B., & Martin, G. L. (2004). A mental skills package for Special Olympics athletes: A preliminary study. Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly, 21, 4–18. https://doi.org/10.1123/apaq.21.1.4

- Hampson, R., & Harwood, C. (2016). Case Study 2: Employing a group goal setting intervention within an elite sport setting. Sport & Exercise Psychology Review, 12, 22–31. https://doi.org/10.53841/bpssepr.2016.12.2.22

- Hardy, L. (1997). The Coleman Roberts Griffith address: Three myths about applied consultancy work. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 9, 277–294. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413209708406487

- Harkin, B., Webb, T. L., Chang, B. P., Prestwich, A., Conner, M., Kellar, I., Benn, Y., & Sheeran, P. (2016). Does monitoring goal progress promote goal attainment? A meta-analysis of the experimental evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 142(2), 198–229. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000025

- Harter, S. (1978). Effectance motivation reconsidered. Toward a developmental model. Human Development, 21, 34–64. https://doi.org/10.1159/000271574

- Harwood, C. G. (2004). Goals: More than just the score. In S. Murphy (Ed.), The sport psych handbook (pp. 19–36). Human Kinetics.

- Healy, L. C., Ntoumanis, N., & Duda, J. L. (2016). Goal motives and multiple-goal striving in sport and academia: A person-centered investigation of goal motives and inter-goal relations. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 19(12), 1010–1014. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2016.03.001

- Healy, L., Tincknell-Smith, A., & Ntoumanis, N. (2018). Goal setting in sport and performance. In Oxford research encyclopedia of psychology. Oxford University Press.

- Jeong, Y. H., Healy, L. C., & McEwan, D. (2021). The application of goal setting theory to goal setting interventions in sport: A systematic review. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 1–26. Advanced online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2021.1901298

- Kingston, K. M., & Wilson, K. M. (2008). The application of goal setting in sport. In Advances in applied sport psychology (pp. 85–133). Routledge.

- Kirschenbaum, D. S. (1987). Self-regulation of sport performance. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 19, 106–113.

- Klein, H. J., Wesson, M. J., Hollenbeck, J. R., & Alge, B. J. (1999). Goal commitment and the goal-setting process: Conceptual clarification and empirical synthesis. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 84(6), 885–896. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.84.6.885

- Kyllo, L. B., & Landers, D. M. (1995). Goal setting in sport and exercise: A research synthesis to resolve the controversy. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 17, 117–137. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.17.2.117

- Latham, G. P., & Locke, E. A. (1991). Self-regulation through goal setting. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 212–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90021-K

- Lochbaum, M., & Gottardy, J. (2015). A meta-analytic review of the approach-avoidance achievement goals and performance relationships in the sport psychology literature. Journal of Sport and Health Science, 4, 164–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2013.12.004

- Lochbaum, M., Stoner, E., Hefner, T., Cooper, S., Lane, A. M., & Terry, P. C. (2022). Sport psychology and performance meta-analyses: A systematic review of the literature. PLoS One, 17(2), e0263408. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0263408

- Locke, E. A. (1968). Toward a theory of task motivation and incentives. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 3, 157–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/0030-5073(68)90004-4

- Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (1985). The application of goal setting to sports. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 7, 205–222. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsp.7.3.205

- Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (1990). A theory of goal setting & task performance. Prentice-Hall, Inc.

- Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (2013). New developments in goal setting and task performance. Routledge.

- Maitland, A., & Gervis, M. (2010). Goal-setting in youth football. Are coaches missing an opportunity? Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 15, 323–343. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408980903413461

- Martens, R. (1991). Coaches guide to sport psychology. Human Kinetics.

- Martin, L. J., Carron, A. V., & Burke, S. M. (2009). Team building interventions in sport: A meta-analysis. Sport & Exercise Psychology Review, 5, 3–18. https://doi.org/10.53841/bpssepr.2009.5.2.3

- McCarthy, P. J., Jones, M. V., Harwood, C. G., & Davenport, L. (2010). Using goal setting to enhance positive affect among junior multievent athletes. Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology, 4, 53–68. https://doi.org/10.1123/jcsp.4.1.53

- McCarthy, P. J., Jones, M. V., Harwood, C. G., & Olivier, S. (2010). What do young athletes implicitly understand about psychological skills? Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology, 4, 158–172. https://doi.org/10.1123/jcsp.4.2.158

- McEwan, D., & Beauchamp, M. R. (2020). Teamwork training in sport: A pilot intervention study. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 32, 220–236. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2018.1518277

- Neubert, M. J. (1998). The value of feedback and goal setting over goal setting alone and potential moderators of this effect: A meta-analysis. Human Performance, 11, 321–335. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327043hup1104_2

- Nicholls, J. G. (1989). The competitive ethos and democratic education. Harvard University Press.

- Ntoumanis, N., & Sedikides, C. (2018). Holding on to the goal or letting it go and moving on? A tripartite model of goal striving. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 27, 363–368. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721418770455

- Ntoumanis, N., Healy, L. C., Sedikides, C., Duda, J., Stewart, B., Smith, A., & Bond, J. (2014). When the going gets tough: The “why” of goal striving matters. Journal of Personality, 82(3), 225–236. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12047

- Oettingen, G. (2012). Future thought and behaviour change. European Review of Social Psychology, 23, 1–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/10463283.2011.643698

- Pierce, B. E., & Burton, D. (1998). Scoring the perfect 10: Investigating the impact of goal-setting styles on a goal-setting program for female gymnasts. The Sport Psychologist, 12, 156–168. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.12.2.156

- Pop, R. M., Grosu, E. F., & Zadic, A. (2021). A systematic review of goal setting interventions to improve sports performance. Studia Educatio Artis Gymnasticae, 1, 35–50. https://doi.org/10.24193/subbeag.66(1).04

- Popay, J., Roberts, H., Sowden, A., Petticrew, M., Arai, L., Rodgers, M., Britten, N., Roen, K., & Duffy, S. (2006). Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews: A product from the ESRC methods programme. Lancaster University.

- Quartiroli, A., Moore, E. W. G., & Zakrajsek, R. A. (2022). Strength and conditioning coaches’ perceptions of sport psychology strategies. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 36(5), 1327–1334. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000003651

- Rovio, E., Arvinen-Barrow, M., Weigand, D. A., Eskola, J., & Lintunen, T. (2012). Using team building methods with an Ice Hockey team: An action research case study. Sport Psychologist, 26, 584–603. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.26.4.584

- Sheldon, K. M., & Elliot, A. J. (1999). Goal striving, need satisfaction, and longitudinal well-being: The self-concordance model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76(3), 482–497. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.76.3.482

- Shoenfelt, E. L. (2011). Values Added” teambuilding: a process to ensure understanding, acceptance, and commitment to team values. Journal of Sport Psychology in Action, 1, 150–160. https://doi.org/10.1080/21520704.2010.550989

- Smith, R. E. (2015). A positive approach to coaching effectiveness and performance enhancement. In J. M. Williams & V. Krane (Eds.), Applied sport psychology: Personal growth to peak performance (7th ed., pp. 40–56). McGraw-Hill Education.

- South, G. M. (2004). The roadmap: Examining the impact of periodization, and particularly goal term length, on the self-confidence of collegiate tennis players [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of Idaho.

- Stambulova, N. B., & Schinke, R. J. (2017). Experts focus on the context: Postulates derived from the authors’ shared experiences and wisdom. Journal of Sport Psychology in Action, 8, 131–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/21520704.2017.1308715

- Storm, L. K., & Larsen, C. H. (2020). Context-driven sport psychology: A cultural lens. In D. Hackfort & R. Schinke (Eds.), The Routledge international encyclopedia of sport and exercise psychology (pp. 73–83). Routledge.

- Swann, C., Crust, L., Jackman, P., Vella, S. A., Allen, M. S., & Keegan, R. (2017). Psychological states underlying excellent performance in sport: Toward an integrated model of flow and clutch states. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 29, 375–401. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2016.1272650

- Swann, C., Jackman, P. C., Lawrence, A., Hawkins, R. M., Goddard, S. G., Williamson, O., Schweickle, M. J., Vella, S. A., Rosenbaum, S., & Ekkekakis, P. (2022). The (over) use of SMART goals for physical activity promotion: A narrative review and critique. Health Psychology Review, 2022, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2021.2023608

- Symonds, M. L., & Tapps, T. (2016). Goal-prioritization for teachers, coaches, and students: A developmental model. Strategies, 29, 34–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/08924562.2016.1159155

- Tod, D. (2014). Sport psychology: The basics. Routledge.

- Tod, D., & McGuigan, M. (2001). Maximizing strength training through goal setting. Strength & Conditioning Journal, 23, 22–27.

- Vealey, R. S. (1988). Future directions in psychological skills training. The Sport Psychologist, 2, 318–336. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.2.4.318

- Vealey, R. S. (2005). Coaching for the inner edge. Fitness Information Technology.

- Vysochina, N., & Vorobiova, A. (2017). Goal-setting in sport and the algorithm of its realization. Ştiinţa Culturii Fizice, 2, 108–112.

- Wang, G., Wang, Y., & Gai, X. (2021). A meta-analysis of the effects of mental contrasting with implementation intentions on goal attainment. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 565202. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.565202

- Wanlin, C. M., Hrycaiko, D. W., Martin, G. L., & Mahon, M. (1997). The effects of a goal-setting package on the performance of speed skaters. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 9, 212–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413209708406483

- Ward, P. (2011). Goal setting and performance feedback. In Behavioral sport psychology (pp. 99–112). Springer.

- Weinberg, R. S. (2013). Goal setting in sport and exercise: Research and practical applications. Revista da Educação Física/UEM, 24, 171–179. https://doi.org/10.4025/reveducfis.v24i2.17524

- Weinberg, R. S., & Gould, D. (2015). Foundations of sport and exercise psychology (6th ed.). Human Kinetics.

- Weinberg, R. S., & Gould, D. (2019). Foundations of sport and exercise psychology (7th ed.). Human Kinetics.

- Weinberg, R. S., Harmison, R. J., Rosenkranz, R., & Hookom, S. (2005). Goal setting. In J. Taylor & G. Wilson (Eds.), Applying sport psychology: Four perspectives (pp. 101–116). Human Kinetics.

- Weinberg, R. S., & Williams, J. M. (2015). Integrating and implementing a psychological skills training program. In J. M. Williams & V. Krane (Eds.), Applied sport psychology: Personal growth to peak performance (7th ed., pp. 329–358). McGraw-Hill.

- Widmeyer, W. N., & Ducharme, K. (1997). Team building through team goal setting. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 9, 97–113. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413209708415386

- Williamson, O., Swann, C., Bennett, K. J., Bird, M. D., Goddard, S. G., Schweickle, M. J., & Jackman, P. C. (2022). The performance and psychological effects of goal setting in sport: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 1–29. Advanced online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2022.2116723

- Winter, G. (1995). Goal setting. In T. Morris & J. Summers (Eds.). Sport psychology: Theory, applications and issue (pp. 259–270). John Wiley & Sons.

- Wrosch, C., & Scheier, M. F. (2020). Adaptive self-regulation, subjective well-being, and physical health: The importance of goal adjustment capacities. In A. J. Elliot (Ed.), Advances in motivation science (Vol. 7, pp. 199–238). Elsevier.

- Young, B. W., Medic, N., & Starkes, J. L. (2009). Effects of self-monitoring training logs on behaviors and beliefs of swimmers. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 21, 413–428. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200903222889