Abstract

To support the growing calls to safeguard athlete health and well-being in the pursuit of sporting success, empirical research into thriving may offer practitioners potential mechanisms to promote both outcomes simultaneously. Yet, given that elite sport environments are increasingly characterized as complex and volatile, applying theoretical knowledge is often not straightforward. In this novel study we aimed to bridge the gap between theory and practice by partnering with a sport psychologist to explore their experiences of promoting thriving within an Olympic sport organization. Using a participatory research approach in a typically inaccessible context, we sought to support the specific needs of the practitioner through a form of collaborative inquiry. Together, over a 9-month period, we navigated the complexities of translating knowledge into practice and present novel insights into the realities of effectively creating systems-level change. Namely, the need for practitioners to deftly negotiate complex interpersonal relationships and organizational cultures, and to democratize responsibility for psychological change to wider stakeholders. Regarding thriving, we demonstrate that the promotion of thriving requires an in-depth understanding of the athletic environment and organizational systems. Further, an array of athlete perspectives is needed when determining what contributes to and constitutes a thriving experience. Through our collaboration with an applied practitioner, this study makes a significant contribution toward bridging the gap between theory and practice. In doing so, we draw attention to the complex and challenging scenarios practitioners face when promoting change at an environmental level within elite sport organizations.

Lay summary

Using a participatory research approach, we explored the experiences of a sport psychologist attempting to promote athlete thriving within a British Olympic sport organization. Our findings highlight the challenges and opportunities of practitioners working in these settings.

IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE

• Practitioners seeking to promote athlete thriving need to develop an in-depth understanding of the athletic and organizational systems.

• Thriving is a subjective experience therefore practitioners should consider how individual differences influence what athletes need to thrive.

• Practitioners must deftly negotiate complex interpersonal relationships when advocating for, instigating, and maintaining change on an organizational level.

Competitive sport can be a demanding endeavor, with significant pressures faced by athletes, coaches, and support staff (Arnold & Fletcher, Citation2021). Notably, the incessant drive for performance excellence within elite sport environments can have deleterious effects on athlete well-being (Whyte, Citation2022), with the pressure to win leading to sporting success being valued above athlete welfare (Phelps et al., Citation2017). In response, scholars have called for sport organizations to prioritize athlete welfare while supporting and developing athletes to succeed, as providing a genuine duty of care is not only a moral obligation but is likely to facilitate optimal sporting performance (Kavanagh et al., Citation2021). Thriving, defined as “the joint experience of development and success” (Brown et al., Citation2017, p. 168), is characterized in sporting contexts as the simultaneous experience of high levels of both performance and well-being (Brown et al., Citation2018). Thus, while in its infancy as a construct, thriving may be of interest to sport organizations and practitioners seeking to implement a genuine duty of care while ensuring athletes achieve the levels of performance necessary for their sport organization to be successful.

Following Brown et al.'s (Citation2017) original conceptualization, researchers have advanced scholarly understanding of thriving in sport performers (see, for a review, Brown et al., Citation2021). To elaborate, achieving the development and success indicative of thriving requires individuals to experience full and holistic functioning across subjective, context-relevant indicators of performance and well-being (see, Brown et al., Citation2021; Ryan & Deci, Citation2017). The experience of thriving has been associated with several psychosocial variables grouped into personal (i.e. individual attitudes, cognitions, and behaviours) and contextual (i.e. environmental characteristics and social agents) enablers (Brown et al., Citation2017). Example personal enablers include personal resilient qualities and a positive perspective (Brown et al., Citation2017, Citation2018; Gucciardi et al., Citation2017), while example contextual enablers include social support and connection to sporting organizations (Brown & Arnold, Citation2019; Davis et al., Citation2021; Feeney & Collins, Citation2015). Further, basic psychological need satisfaction (BPNS; Ryan & Deci, Citation2017) and challenge appraisal are proposed as key process variables of thriving (Brown et al., Citation2017), with both reliably shown to predict thriving in sport performers (Brown et al., Citation2021; Brown et al., Citation2021; Kinoshita et al., Citation2021). Along with the suggested determinants of thriving, the experience of thriving has been found to provide a platform of momentum for future personal growth and sporting performance improvements (Brown et al., Citation2018). Therefore, the identification of positive outcomes of thriving (e.g. Brown et al., Citation2018) as well as potential mechanisms to promote it (e.g. Brown et al., Citation2021) make thriving an attractive goal for sport organizations. Within this previous work, thriving has been investigated as an individual athlete experience. Emerging research has recently begun to consider collective thriving (see McGuire et al., Citation2023), and while there are relational features suggested to influence both individual and collective thriving (e.g. BPNS), more research is needed to understand collective thriving. As such, in the current paper we explore thriving at the individual level.

Sport psychology practitioners seeking to promote thriving within sport organizations may consider focussing on the contextual enablers given Ryan and Deci (Citation2017) suggested that an individual’s ability to thrive is contingent on the features of their environments, including direct interpersonal contacts (e.g. peers, teams, organizations). Indeed, adopting a holistic approach to athletes’ environments that incorporates the wider contextual factors has been shown to positively impact on the development and performance of academy and elite athletes (e.g. Henriksen, Citation2015). With respect to thriving, the importance of social interactions and connections within sporting environments has repeatedly been generated from the analysis of sport performers’ qualitative accounts (Brown et al., Citation2018). Importantly, Passaportis et al. (Citation2022) found athletes identified the understanding, openness, and trust developed with coaches, teammates, and support staff as instrumental in their ability to perform and to experience high levels of well-being within their sporting environment (see also, Brown & Arnold, Citation2019; Harris et al., Citation2012; McHenry et al., Citation2020). While contextual enablers appear to be integral to athlete thriving, promoting these enablers within increasingly complex, turbulent, and volatile elite sport organizations likely requires consideration of organization-wide systems and influences (Wagstaff, Citation2016; Passaportis et al., Citation2022).

Adopting an organizational lens when considering athlete well-being and performance is well-established within sport psychology research (see for e.g. Wagstaff, Citation2019). Indeed, sport psychology practitioners are increasingly being asked to consult on the creation and modification of organizational environments and practices (Collins & Cruickshank, Citation2015; McDougall et al., Citation2020). Practitioners working at an organizational or systems level is encouraging given the ability it affords them to initiate change and promote environments that facilitate athlete functioning on a broader scale (Wagstaff & Quartiroli, Citation2023). Nevertheless, for practitioners to be effective at influencing change within an organization, they will likely be required to collaborate with a diverse range of social agents (e.g. coaches, support staff) who intersect to support the development, preparation, and performance of elite athletes (Arnold et al., Citation2019; Henriksen, Citation2015). Such collaboration could require competencies and skills not fully established during their professional development and training (Fletcher & Arnold, Citation2011; Wagstaff & Hays, Citation2020). Moreover, to be effective, practitioners are encouraged to engage in evidence-based practice, yet Winter and Collins (Citation2015) lamented a lack of applied relevance in much of the general sport psychology research. While these comments were not directed at thriving or organizational research directly, practitioners have expressed dissatisfaction with the usefulness of scientific literature available to them which has led to limited research-informed practice (Winter & Collins, Citation2015). Indeed, the creation of scientific knowledge that is not integrated into practice is a recognized concern among sport and exercise science researchers more broadly, who warn of a know-do gap (Leggat et al., Citation2021).

While not all scientific knowledge needs to have social utility, scholars wishing to produce knowledge that can inform practice might consider the reasons for why such a gap exists. Within the sport psychology discipline, this includes a lack of research relevance (Winter & Collins, Citation2015), not adequately considering the applied setting (Keegan et al. (Citation2017), and knowledge that is not understood or translated effectively (Everard et al., Citation2022; Leggat et al., Citation2021). Thus, to advance scholarly understanding of thriving by exploring its application within elite sport organizations, scholars may look to conduct research that incorporates the competencies of, and realities for, sport psychologists. Doing so aligns with recent calls for “a participatory turn” whereby more equitable research is conducted with nonacademic partners who can contribute their lived experiences to enhancing knowledge translation and production, and better connect theory to practice (Smith et al., Citation2022, p. 2). For example, approaches such as Integrated Knowledge Translation, that include end-users in the research process, have been used to translate evidence-based narratives of sport injury into more accessible formats for athletes (Everard et al., Citation2022), and to evaluate injury prevention resources for practitioners (Richmond et al., Citation2021). In addition, studies framed within the participatory paradigm have facilitated collaboration between the researcher and the researched (Lincoln et al., Citation2018), with scholars and nonacademic partners exploring the lived experiences of sport related concussion (Seguin & Culver, Citation2022), co-constructing mental performance profiles of elite athletes (Durand-Bush et al., Citation2023), and co-designing centers for athlete mental health and support (Van Slingerland et al., Citation2021).

Given the ability to translate research into practice demonstrated in previous co-constructed work, a participatory approach was adopted for the current study by partnering with a sport psychologist attempting to promote thriving within an Olympic sport organization in the United Kingdom (UK). In doing so, we aimed to explore the experiences of applying thriving research into practice and the utility of thriving for safeguarding athlete well-being in the pursuit of sporting success.

Methodology and methods

Participatory research

To understand how thriving may be implemented within elite sport organizations this study explored the experiences of a sport psychologist operating within an Olympic Sport organization in the UK. Our intentions with this study were to understand the realities practitioners face when translating academic research into practice within diverse organizational systems, and to explore the applicability of thriving as a concept. To facilitate these aims, a participatory research (PR) approach was adopted. PR is an umbrella term that encompasses an array of research designs, methods, and frameworks that recognize the value of engaging the intended beneficiaries, users, and stakeholders of the research in the research process (Cargo & Mercer, Citation2008; Vaughn & Jacquez, Citation2020). PR approaches are underpinned by a relativist ontology (Scotland, Citation2012), and grounded in constructionism, whereby researcher and participant co-construct knowledge that is subjective and inextricable from the wider social, cultural, moral, ideological, and political context of the research (Sharpe et al., Citation2021). What distinguishes PR from other approaches “lies not in the methods but in the attitudes of the researchers which in turn determine how, by and for whom research is conceptualised and conducted” (Cornwall & Jewkes, Citation1995, p. 1667). Thus, PR allows researchers and their nonacademic participants to form mutually beneficial partnerships that combine theoretical and methodological expertise with real-world knowledge and experiences (Cargo & Mercer, Citation2008). Involving participants in the research process redresses the balance of power in the decision-making process, resulting in power that is relationally shared between the researcher and the researched (Macaulay et al., Citation1999).

Grounded in a PR approach, we selected a collaborative inquiry methodology to explore the experiences of a sport psychologist applying research into practice in an Olympic sport organization. We felt collaborative inquiry was best suited to achieving our aims as researchers and participants engage in a systematic, iterative process of action, reflection, and the sharing of experiences (Bray et al., Citation2000). Further, knowledge is produced that can inform and improve practice, and facilitates participants integrating theoretical knowledge into their own practice (Bray et al., Citation2000). Influenced by the work of Seguin and Culver (Citation2022), our study was framed on three central tenants of Bray et al. (Citation2000) definition of collaborative inquiry. Specifically, we: (1) established an equitable relationship between researchers and participants, whereby participants were viewed as co-researchers and involved in decision making, discussions, and reflections; (2) prioritized cycles of reflection and action to understand human experience and to learn from these experiences; and (3) ensured our research questions were important to those who were involved in the research process.

The research context

In the current study we document the experiences of a sport psychology practitioner operating in an Olympic sport organization in the United Kingdom. Senior leadership of the organization had conducted an independent audit of their organizational culture and environment and were dissatisfied with the findings: athletes self-described as surviving rather than thriving, experienced hierarchical and controlling coaching structures, and perceived a lack of autonomy. Consequently, senior leadership were committed to instilling a new duty of care by promoting thriving across their organization. To facilitate this aim, the sport psychologist (hereafter referred to by the pseudonym “Sam”) now formed part of an expanded psychosocial leadership group with a remit to facilitate athletes, coaches, and staff to thrive not only in training, but in all aspects of their sporting lives. While Sam had no prior engagement as a participant or collaborator in thriving research, they were aware of the research teams’ ongoing work (see for e.g. Passaportis et al., Citation2022). Thus, Sam identified an opportunity to engage with external academics to assist them with promoting thriving. The organization’s senior leadership (i.e. Performance Director [PD] and Head of Performance Services [HOPS]) were open to this collaboration and met with myself (the first author), the third author, and Sam to discuss the parameters of what such a project would entail. From this meeting it was established that Sam and I would work together, with Sam adopting the role of co-researcher and engaging in all aspects of the project, from decision making to data analysis and the final presentation of findings. The senior leadership team limited participation from the organization to Sam, as they wished to minimize disruption to training and preparation. Following this meeting, institutional ethical approval was obtained.

Procedure

Data were generated through several methods over a nine-month period between August 2020 and April 2021. The primary forms of data production were online meetings held between Sam and me (N = 9, M = 96 minutes, SD = 26 minutes). Within these meetings, I occupied the role of facilitator, offering theoretical insight, research knowledge, ideas, and experiences while recognizing and embracing Sam’s contextual knowledge. This provided Sam with opportunities to explore and make sense of their experiences within an equitable decision-making environment that supported diversity of opinion and the expression of different points of view (see Cargo & Mercer, Citation2008; Sharpe et al., Citation2021). Each meeting was audio recorded and transcribed in full, producing 112 pages of double-spaced text that were supplemented with organizational documentation, co-researcher generated data (e.g. interview with head coach), and researcher and member reflections. Additionally, feedback on the relevance, connection to practice, and accessibility of the output from three neophyte practitioners working in competitive sport organizations was integrated into the final output. We undertook this integration to ascertain if the work produced was applicable to applied practice. The remainder of this section will outline the research procedures, which comprised three and half cycles of reflection and action.

The first reflective phase included the initial three meetings between Sam and I. Meetings 1 and 2 involved a detailed exploration of Sam’s professional history, their present context, and the challenges they felt they were currently facing. Namely, the translational challenge of operationalizing the extant literature on thriving within a dynamic organizational structure. Through our discussions, Sam and I identified an opportunity to combine Sam’s applied expertise with the research team’s knowledge and understanding of thriving to explore how a sport psychologist may use thriving within an elite sport context. In the third meeting, Sam and I drew on researcher and co-researcher reflections, organizational documentation, and thriving literature to identify the best course of action to take. This was to conceptualize thriving within Sam’s organization. Thus, in the first action phase Sam was empowered to create a sport-specific model of thriving that made sense to them and their context.

The second reflective phase began with our fourth meeting, whereby Sam and I critically appraised the sport-specific model of thriving generated in the action phase against the extant thriving literature. Following this, we sought to gain further critical reflections by engaging wider stakeholders, namely coaches and athletes. Despite practical challenges (e.g. no access to the broader organization) that limited our ability to do so, Sam was able garner reflections from a group of previous Olympic athletes (N = 8) that were integrated into our thriving model during our fifth meeting. In our sixth meeting, Sam and I worked through our personal reflections and used this discussion to generate the next action phase. This entailed Sam deconstructing the thriving model to produce an assessment tool they could use to generate thriving profiles for individual athletes.

Meeting 7 was the third reflective phase, in which Sam and I critiqued the thriving profile tool that had been constructed. This involved considering the tool from both of our perspectives (i.e. academic and practitioner) and working through each other’s viewpoints. Once we were both comfortable with the thriving profile tool, Sam trialed the tool in the third action phase with a pilot group of four athletes and garnered their feedback on the profiling process.

The fourth reflection stage took place in meeting 8, where Sam and I collaboratively made sense of the (anonymised) profile data and athlete feedback Sam had generated through the pilot trial. Together, we decided how best the profile data could be used by Sam to be most effective within the organization. The next and final action stage built from the pilot study by trialing the thriving profile with dyads and teams.

Our 9th and final meeting was intended to be a reflection on the data gathered from the dyads and teams but did not turn out as planned due to unexpected developments. Instead, we reflected on these and the project as a whole. Following this meeting, Sam provided three rounds of member reflections on the draft of the manuscript, until such point as they were happy with what was presented. Additionally, great care was taken through these member reflections to ensure Sam felt the manuscript was anonymised sufficiently and protected their and the organization’s identity.

Analysis and presentation

Meaningful analysis was engaged with from the beginning of the project by integrating a form of participatory analysis into the research process. While not recognized or formally labeled in the project as data analysis, this consisted of building a constructive and collaborative process of reflection into the cycles of action and reflection integral to participatory approaches (Cahill, Citation2007). This involved analysis with Sam, whereby Sam and I would ‘check back’ with one another, sharing our reflections to clarify our interpretations, understandings, and suggestions (Bhavnani, Citation1994). Importantly, this was a self-reflexive practice whereby Sam and I considered how the research process had changed our understandings, and how these changes in turn shifted our engagement with our contexts (see Cahill, Citation2007). Doing so ensured that the project remained aligned with the central tenants underpinning PR and addressed the research questions. To elaborate on the former, engaging in collaborative reflection provided space for Sam’s voice to be heard and for them to drive the research process to best serve their needs. This exhibits a commitment to collective knowledge production which assumes knowledge is most powerful when produced collaboratively (Fine et al., Citation2003). By constantly reflecting on our progress, Sam and I were able to ensure that each course of action moved our collaboration in the direction of the research aims (e.g. translating theory into practice).

Upon completion of data collection, formal data analysis began. Here, I took the lead by conducting an inductive content analysis of the data (cf. Keegan et al., Citation2010). In keeping with our PR approach, the qualitative content analysis was epistemologically grounded in constructionism as data and analysis were viewed as co-creations (Mishler, Citation1991). I began the analysis by re-immersing myself in the data (i.e. meeting transcripts, reflections, co-researcher data, neophyte practitioner feedback, and organizational documentation) to obtain a sense of the whole. Next, I organized the data set into broad categories. Morse (Citation2008) describes categories as a collection of things, opinions, perceptions, and experiences that are useful for determining “what” is in the data. The categories were created through coding the data at the manifest level, keeping my analysis close to the data and applying descriptive labels (e.g. adapting to new role, facing resistance) with a low degree of abstraction (Graneheim et al., Citation2017). Once all data had been coded, similar codes were grouped together to form six categories representing the projects trajectory over time (i.e. Adapting to New Role, Thriving as a Vision, Organizational Sense Making, Implementation of Change, Resistance, Adaptation, and Fallout). For example, the category New Role contained all codes related to Sam’s integration into a new sport organization, Organizational Sense Making included codes documenting Sam and my attempts to understand the complexity of their organization, and Adaptation comprised codes capturing the evolution of Sam’s efforts to promote thriving.

Once all data had been categorized, I began to generate themes. This involved shifting focus from descriptively coding data at the manifest level, to interpreting the latent meaning underpinning the codes at a higher level of abstraction (Graneheim & Lundman, Citation2004). Themes in qualitative content analysis are unifying threads of meaning that run through the data set, spanning several categories, and bringing meaning to experiences (Morse, Citation2008). Thus, I constructed patterns of meaning from Sam and my experiences that were woven through multiple categories to generated themes. To illustrate, the theme Comfortably Uncertain spanned the entire data set and captured the constant uncertainty Sam felt with many of their decisions and actions. Lost in Translation permeated the early stages of the work and was a theme constructed from codes that illustrated the messy and complex challenge of translating academic theory into practice, as well as the need to be flexible and practical. While Me versus Us encapsulated the tensions inherent in leading organizational change as a sport psychology practitioner who is embedded within a wider multidisciplinary team. Throughout the analysis, I critically reflected on my own experiences, but also on that of Sam’s through the process of indwelling which involves placing oneself in the shoes of another to attempt to empathetically understand their point of view and experiences (Maykut & Morehouse, Citation1994).

To effectively portray the complexity of Sam’s experiences, I then adopted a storyteller standpoint as this allowed me to move beyond telling Sam’s story, to showing their story (Smith & Sparkes, Citation2009). This involved shifting from an analysis of the story toward considering the act of storytelling as an analysis in itself (Smith & Sparkes, Citation2009). An effective way to do this is to engage in creative analytical processes (CAP) which encompass a broad range of research practices that are both creative and analytical (Richardson et al., Citation2005). Through the crafting of a story, the researcher takes on the role of storyteller by engaging in a writing process that draws on various tools of narrative (i.e. dialogue and plot) to shift between showing what is said to showing how it was told (Smith & Sparkes, Citation2009). For the current study, this involved creating a composite account of both Sam and my experiences of our collaborative inquiry. To achieve this, I drew on the creative nonfiction technique referred to as the scenic method (Agar, Citation1995). Through this technique, situations are recreated in such a way as to involve the reader in the immediacy of the experience (Sparkes, Citation2002). The creative nonfiction that follows moves in a chronological direction, yet this does not precisely mirror the events that took place, nor is it inclusive of every course of action that was taken. Rather, the most pertinent categories were selected and combined to create the spine of the story. This involved piecing together parts of different categories, while omitting other less captivating or relevant ones, with the aim of telling the most engaging story of the data. Once this spine was formed, the themes were woven into it to produce a cohesive story of a sport psychologist creating change within an Olympic Sport Organization. A first-person perspective was used to allow Sam’s voice to be centralized in the story. Sam’s experiences were evoked by creatively drawing on Sam’s personal reflections, Sam and my collaborative reflections, and my reflexive notes to fill in the gaps and to show how these events were experienced.

We chose to present the results as a creative nonfiction for several reasons. First, creative representations allow for the manipulation of information in subtle ways that ethically protects those whom the story is about (Sparkes, Citation2002). Second, such representations enable the reader to meet the ‘characters’ in the voice, emotion, and context of their experiences which is not available through scientific writing or nonfictional alternatives (Krizek, Citation1998). Third, given the intention with this project was to translate knowledge into practice, fictional representations invite dialogue and reflection by shedding light on the theory being studied and resonating with the reader’s experience (Sparkes & Smith, Citation2014). Thus, the reader can gain a deeper understanding of experiences and phenomenon (Cavallerio, Citation2022). The results were shared with Sam to garner their reflections and to ensure that their story was presented ethically, and in a way that they felt best demonstrated their attempts to translate research to practice (Smith & McGannon, Citation2018). In total, Sam provided detailed feedback on the manuscript three times.

Results

A ‘New Sam’ for a new challenge

It’s been several months since I joined this Olympic sport organization and, in that time, I’ve struggled to find my feet as my resolve and philosophy have been constantly tested. Yet, somewhat surprisingly, when I weigh it all up, I feel positive and determined for what lies ahead. Maybe it is because I’m more experienced, resilient, and adaptable now and I’ve formed strong working relationships with the PD and HOPS. That’s why I’m excited by where I am and what I’m doing. The confidence leadership has in me fuels my determination and allows me to remain true to my principles in this often brutal world of elite sport. A world, I know, that is about facilitating performance outcomes and winning medals. I can handle this world, even when I’m challenged by the highly experienced head coach. The sting of the criticism I received for asking an athlete how they were coping with an intense block of training is still fresh, who would have thought that would be seen as overstepping my boundaries as a psychologist! The Sam of old would have shrunk away after being rebuked like that, but this Sam is less ‘rockable’, I wear that experience as a badge of honor, I’m now part of a select few and I have an opportunity to learn about elite performance from such an experienced coach. I want to change minds and win coaches over, even if the coaches have always done things their way. Even if their way has always produced Olympic medals. Yes, I’m determined to help leadership transform this organization and make it thrive.

I know ‘New Sam’ is not immune to the influences of my environment though, as one coach’s comment have been difficult to shake: are you here for performance or are you here for well-being? A seemingly innocuous question when I compare it to other encounters I’ve experienced, so why has this one stuck with me? If I’m honest, I think it’s because I like research to inform my actions, that’s what good practitioners do right? I know the thriving literature and that to be effective I should dedicate time to understand the culture and nuances of my sport. I’m frustrated though, as that’s exactly what I have been doing. Since joining the organization, I have listened, probed, observed, and worked to place myself in the best position possible to implement leadership’s vision of thriving. Except, despite all my efforts, I feel no closer to knowing what to actually do. I can’t simply lift the neatly presented theories from academic journals and apply them to the dynamic complexity of my organization (see ). I can’t use those findings to make a clear action statement I can hang my hat on and say, “this is why performance matters, this is why well-being matters, and this is why thriving matters.” This leaves me uncertain and unable to formulate a strong, confident response to the question “are you here for performance or are you here for well-being?” I’m here for both; performance and well-being are equally important and can be experienced in tandem.

Table 1. Examples of issues impacting thriving within the sport organization.

My appointment to the psychosocial leadership group came off the back of an internal review assessing the organization’s culture. My interpretation of the review is that it shows how the culture and climate were described or experienced when at their worst, with the headlines being an autocratic coaching style, athletes in survival mode just doing what they’re told, and feeling like a cog in a machine with little agency or voice. Thriving is the mechanism senior leadership have chosen to address these issues, and I’m here to lead on integrating thriving into the psychosocial groups’ strategy. The scale of such a challenge is not lost on me as I contemplate introducing change into an organization that has achieved outstanding success by rigidly adhering to the same formula for years. I’ve seen enough to know that while well-being might be valued in this environment, I’m going to need to convince people that well-being can be incorporated without impacting the winning formula. Not only that, but I must do this across a complex organization, while under pressure to get it right if I’m going to be successful. It occurs to me, somewhat dauntingly, that I’m going to need step out of my comfort zone and go beyond my familiar sport psychologist role of working one-on-one with athletes and coaches. This environment will limit anything I do like that, any progress I make will eventually hit an environmental ceiling. Instead, I’m going to have to change organization systems. Something my professional training and development have not covered. I’m prepared for these challenges though, as I recognize maybe other practitioners can learn from what I get right, but more likely what I get wrong!

Blue skies and muddy trenches

I take out my copy of the Olympic Planning Strategy for the 2024 and 2028 Olympic cycles, noticing how the edges are frayed with use and the margins filled with my scribbled notes. Inside, the senior leadership team’s vision is laid out in full. Taken at face value, the strategy aims to facilitate thriving and to enable people to perform to their best by placing people and their well-being at the center of the organization’s actions and ensuring athlete are not just ‘a cog in the machine’. However, my annotations tell a different story, highlighting how thriving is seen as a stable experience, as someone always being able to deliver their best performance. I’ve been struggling to marry this ‘stable’ vision of thriving with leadership’s need to create an adaptable and dynamic system to cope with the complexity of the organization. I’m uncertain as to how a stable thriving experience can materialize in this dynamic complexity. Additionally, leadership’s use of a performance-oriented description of thriving (i.e. “delivering their best”) is not a portrayal of thriving I feel comfortable hanging my hat on just yet. Where does well-being fit in and how might such a description align with a desire for well-being to be at the center of the organization’s campaign? It seems to me that leadership’s aim is to form a sustainable culture and environment that ensures the athletes feel valued and rewarded for their dedication and investment to the sport. Such lofty goals and ideals are indicative of leadership’s blue-sky thinking and often form the bedrock of such strategies. I can see the merit in producing a high-level strategy, but when it comes down to doing my job, blue-sky thinking gives me little that I can put in place to promote thriving ‘on the ground’.

I’m searching for a sense of certainty to inform my actions. Typically, I gravitate toward something tried and tested, like a V-MOST framework (i.e. vision, mission, objectives, strategy, and tactics; Sondhi, Citation1999). Yet, I know a linear, structured way of thinking is unlikely to work here. Instead, I decide to take a less familiar route, reflecting on what I’ve seen, heard, and learned in my time with the sport. To ground my thinking, I explore my experiences through the lens of thriving theory, questioning how my observations fit with development and success, and subjective performance and well-being. Performance will be an easy sell; coaches will be happy to buy into a way of working that enhances performance outcomes. It’s the well-being side of thriving that may require work. I’ve noticed a tendency for well-being to become inconspicuous within the training and competition environments, with coaches struggling to recognize well-being’s explicit benefit to performance. It’s often assumed, I muse, that if the athletes are performing well, they must be well. Yet, reading between the lines of the Olympic Strategy document shows a dedication to providing athletes with value, a sense of purpose, and control in their actions: a commitment to enhancing eudaimonic well-being. When most coaches hear the word well-being, they think of hedonia, like happiness and pleasure. But if I refer to the dimensions of eudaimonia instead of well-being, maybe well-being might appear less ‘soft’? I wonder if ‘selling’ well-being in this way might gain more traction and consider other language already used within the organization’s systems that could be used. I feel enthusiastic! I’m beginning to take some steps forward.

Planting the “thriving” flag

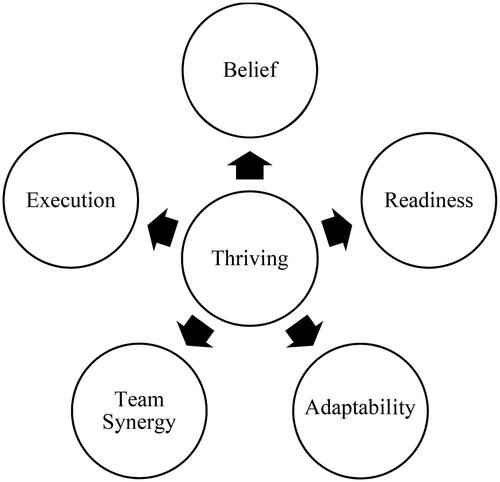

“Are you here for performance or are you here for well-being?”. An acceptable answer will have little space for academic jargon. I know that to get thriving across, the concept needs to be made relatable by conceptualizing what thriving may look like in this environment. While we have not always seen eye-to-eye, the Head Coach has a history of Olympic Success and has been the bedrock of the sport. Looking past their transactional style and apparent apprehension of psychological support, I meet with them to understand what they have learned about thriving within this sport. I’m not given a golden list of defining thriving characteristics, but the coach does share numerous stories about what had underlined their most successful athletes’ achievements. From these stories, I generate common threads that I weave together into a sport-specific model of thriving I term the Thriving Mindset Model (TMM; see ). If I’m honest, this model captures little contextual or environmental information, but does that matter? This is my definition of thriving for this sport, if athletes have belief, if they are ready for competition, if they can adapt and compete as one to execute a winning performance then those are factors that would facilitate their thriving. Still, I’m feeling uneasy because there is no explicit reference to well-being. I worry I’m in danger of softening my commitment to well-being to gain traction.

Figure 1. The thriving mindset model (TMM).

Belief: confidence in oneself, one’s skills and ability to execute. Readiness: readiness to compete, composure before competition, appropriate individual and team arousal levels; Adaptability: Flexible competition plan, adapt to opponents and conditions; Team Synergy: gel as a team, being united, in tune with one another; Execution: execute what needs to be done, deliver skills in order to execute a winning performance.

The apparent lack of well-being language just doesn’t sit well, so I return once again to the literature. With the five dimensions of the TTM laid out in front of me, I unpack them one-by-one, considering how well-being might underpin each dimension. Take belief, well-being would include self-efficacy and having purpose, and readiness could contain parts of competence, while synergy may include a sense of belonging, trust in one another and having good support networks. I feel my discomfort begin to ease as I can see the potential this model has to develop into a sport-specific definition of thriving; if a coach asks me why thriving is important, I can show them the TMM, a visualization of what we’re trying to do. I can articulate in an accessible way how thriving is essential because a team that has high synergy and performs well together needs to support each other and have good relationships. I am confident that my TMM can help subtly challenge the dichotomous thinking around well-being and performance within the organization. Maybe not every component of well-being mentioned in the literature needs to be ticked off to still be promoting it. In fact, going on about the importance of well-being won’t get me far, but I know well-being is incorporated in the model, so I’m ok leaving the word out.

One for all, or all for one

I’m getting tired of waiting. It’s been a few weeks since I’ve tried to include more voices by inviting coaches to come and discuss the TMM, but none have responded. Is this not important? With frustration building, I forge on by exploring the utility of the TMM. The Covid-19 lockdown limits my direct access to athletes, but I have an alternative: a focus group of eight retired multiple Olympians (several gold medallists) who remain somewhat involved with the Olympic programme. I’m feeling protective of my model as I ask the group to critique it and see if it captures their experiences of thriving in this sport. I’m surprised at how the ‘individuality’ of thriving stands out, as thriving appears to have been a different experience for everyone. For some, they thrived on the monotony of training, of being almost robotic. While others thrived despite the monotony. Robotic routines got them ready to compete, but they thrived when competition began. Of note is that they all acknowledge how their thriving experiences were influenced by their elite status as athletes, as they were usually first on any roster. Being longstanding members of the team with a healthy balance of successful performances behind them, they tell me how selection was an easier period for them and so they were more likely to thrive through these experiences: I don’t know what thriving would look like for those further down that roster, who only got their spot after months of battling for selection. In fact, these athletes admit to me that their elite status likely provided them the ability to shape their environments and to be heard. They had not been passive, rather, they exerted their own agency on the environment, initiating difficult, open conversations among teammates to promote trust and respect. They acknowledge this was easier for an established champion: they wouldn’t have had the nerve to ask a senior teammate what makes them tick when they were a novice.

I’m invigorated by how well the TMM is received. Yet, something nags at the back of my mind. As I explore what it might be, I begin to realize that I have neglected the individual subjectivity of thriving. I have drawn on reflections of a successful coach which I augmented with input from some of the sport’s most successful competitors. Am I prioritizing the success part of thriving and making thriving dependant on performance outcomes? Does that consign all other athletes who do not achieve outstanding success, who do not have a voice, to never be able to thrive? I start to grapple with uncertainty. How then do I ensure everyone can thrive? How does one incorporate the nuances of individual differences, temporal fluctuations of training and competition, and differing degrees of agency within the environment to promote thriving for all, not just those at the top of the roster? I need to know which athletes thrive in training and view competition as just any other day; which athletes find an extra 10% in competition that makes them thrive; which athletes face long periods of uncertainty over selection and are just surviving until then; which athletes are sure of their place; and which athletes may never thrive.

Contemplating this complex challenge, I question whether creating a uniform thriving experience is even achievable? Perhaps a better course of action might be to shift my focus from creating a system that promotes thriving toward a system that champions the individual athlete’s needs? If we place the athlete at the center of what we do and shape their environment around what we understand of the person, that might have the biggest impact on well-being and performance. I am acutely mindful of the physical homogeneity that dominates the sport and organization (see ) and understand the TMM needs to reflect that athletes are unique individuals, with evolving and fluctuating needs that produce unique thriving experiences.

Charting a new course

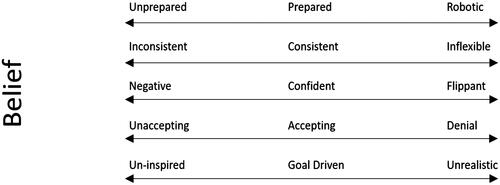

Promoting thriving on an individual level feels more familiar to me as I begin reworking the TMM. I’m back in my comfort zone. First, I subdivide each of the model’s five dimensions into six descriptors which I then arrange along a continuum from ‘underplayed’ to ‘overplayed’ (see for e.g. ). I now have an assessment tool that can identify the needs and preferences of individual athletes, whereby the athletes can indicate on the scale where they feel they sit for each descriptor. Such a tool might produce a unique thriving profile, and enable me, the support staff, and coaches to promote thriving by shaping the environment around this. I’m aware that such a tool requires rigorous testing before it can be deemed valid and reliable in a research capacity. Yet, I know this tool is useful to me, in my context, in my role, with my athletes. It has been developed in and captures the complexity of my environment and I can see the value in creating a profile of how each athlete functions for each descriptor, and what it looks like when each athlete thrives.

To know what an athlete’s thriving profile looks like, I want to establish a thriving baseline. I recruit a small sample of four pilot athletes who have returned after lockdown and take them through the TMM Profile, explaining each dimension and its underpinning characteristics, defining what the descriptors mean, and being clear that this is a strengths-based model. It’s important to me the athletes understand the continuum from underplayed to overplayed does not connote value, but rather everyone’s sweet spot upon it is likely different, and my intentions are not to measure a score for each descriptor, but to paint a picture of what the athlete’s optimal functioning might look like. I ask the athletes to think about their best performance; where they had felt particularly good, had done well but had also been under significant pressure, like a really important competition. For some, it is the last team trials they took part in and for others it is the final at the previous Olympic Games. With this performance in mind, the athletes indicate where they feel they sat for each dimension at the time. Shortly after, the athletes take part in ‘benchmarking’, an intense week where the athletes undergo a battery of physical assessments before they move into a new training block. When this week concludes, I ask the same four athletes to indicate on the profile where they feel they currently are.

I sit and stare at the profiling outputs for what feels like ages. I do not have a clear idea of how to use them. One athlete’s query sticks firmly in my mind, “is this just another way to measure us, to give us a belief score or something?” I know how much of the athletes’ lives are quantified and I’m desperate not to add to that, so I start to explore different ways to use the data. What picture might this paint about the athlete and their experiences? Studying one athlete’s profile, I note how it depicts them feeling unprepared, lacking belief in their ability, and that they have not yet developed an effective relationship with their team. Plus, I know this athlete was unable to execute at benchmark testing. Following up with the athlete, I use the profile to prompt deeper, more nuanced conversation, and learn that the athlete is having difficulty with the uncertainty surrounding the upcoming Olympic Games and lack of adequate preparation due to lockdown. The athlete self-describes as far “off my best” and is trying hard to get back there. Thus, I discover power lies more in the detail and stories the profiles can encourage people to tell when we combine it with the athlete’s context. The profile, I realize, is an effective prompt to generate open and frank conversations with athletes about their performance and well-being. Conversations that can increase awareness about individual strengths and limitations and identify how best to support the athlete by developing deeper, more meaningful connections between staff and athletes. I am delighted with the progress and start to consider other applications for the thriving profile. I can see potential uses with teams to create awareness of preferences and differences, of strengths and weaknesses. I’m planning, I’m excited, and I finally have my definitive answer: I’m here for thriving!

Coming full circle

Before I can try out the profile tool in these new ways, I spend some time in my role with the psychosocial support group. I’m excited as it gives me a chance to update the group on the progress I’ve made toward our thriving vision. I believe the group has collectively bought into my plan to explore how best to integrate thriving and to feedback what I learn. I never intended to do it alone, but I pushed ahead with the TMM as I felt it was clearly aligned to the group’s goals. For the last year and a half, I’ve worked to understand thriving within the context of this sport, to move it from a high-level ideal to something actionable, something tangible that could be implemented and that could achieve results. I admit I made sacrifices along the way; well-being is not as front-and-center as I would have liked. But I’ve been strategic, endeavoring to build well-being into the strategy in all but name and I’ve achieved relative success doing so. Yet, when I finish presenting the work I’ve done to the psychosocial group, I’m taken aback by the responses I receive. I struggle to understand why there is resistance to what I believe is progress. I am deflated. I went to the meeting excited to share an actionable route to promote performance and well-being. Instead, my colleagues dismiss the TMM as too performance focussed, and because well-being is not explicitly named, that performance is being valued over well-being. Instead of moving forward, the group revert to identifying what direction we should go, attempting to define what is meant by thriving, and how it might be achieved, if at all. All my work is pushed aside.

It takes me some time to make sense of what transpired, but I can now see the mistakes I made. I never established a shared understanding with my colleagues for how well-being was being applied. Thus, there was no consistency of language, method, or definition. By forging ahead with the TMM by myself, I didn’t factor in people’s personal preferences and methods of working, so although I had success working with one micro team [athletes], that didn’t automatically translate to the different organizational systems [psychosocial group]. While I’m frustrated that my hard work appears to have been in vain, I must concede I was happy to be more creative with the semantics of well-being if I was making progress. But, perhaps when someone holds tightly to the belief of well-being as the most important thing, when you take that idea and make it more implicit it doesn’t always sit with everyone’s preference. Thus, as much as I see potential in being able to have an impact working at the systems level, I know there is just as much potential to get bogged down in ‘blue-sky thinking’, perfect ideals, and lofty guiding principles. I’m on the ground, in the thick of it, and feel I know what it will take to get thriving across the line. It will not be done by going back to the drawing board. Once again, I’m being asked if I’m here for performance or for well-being. Except now, I feel like I’m seen as being there for performance.

Discussion

In this study, we used PR and creative nonfiction to collaboratively explore and show the realities of a sport psychologist’s attempts to promote thriving at a systems level within an Olympic sport organization. By prioritizing the expertise of the participant in the research process, we hope to have illuminated the challenges and practicalities that practitioners face when leading change within diverse multidisciplinary teams and the complex realities of translating knowledge into action. In communicating the practitioner’s experiences in story form, we intend our findings to generate applied understanding in elite sport settings and to create resonance with other practitioners. The discussion that follows will use these experiences to draw attention to the competencies practitioners may require to effectively provide support to organizational systems, while cautioning against practitioners taking complete and sole ownership of change initiatives. Additionally, through the accounts of the participant we show thriving within elite sport settings to be a subjective and contextualized experience, with several considerations for sport organizations wishing to facilitate athlete thriving.

In addressing our first aim, this research provides a significant contribution to understanding the lived experiences of a sport psychologist translating knowledge into practice within an Olympic sport organization. Using a PR approach provided Sam agency to develop and steer the project toward a beneficial outcome for them (Durand-Bush et al., Citation2023), and allowed for an exploration into the realities of ‘doing’ sport psychology at a systems-level. Thus, we believe this study highlights how elite sport practitioners are increasingly being required to provide their services in a multitude of evolving scenarios while integrating within multidisciplinary teams and collaborating with senior leadership (e.g. Passaportis et al., Citation2022).

Scholars have written about the success and impact practitioners have achieved when operating at a systems level (e.g. Diment et al., Citation2020; Henriksen, Citation2015; Henriksen et al., Citation2011, Citation2020). Yet, there is a scarcity of resources depicting the challenges and difficulties inherent in effectuating such encompassing change (see for notable exception, Larsen, Citation2017). Any environmental or systems-based approach practitioners adopt within elite sport will need to incorporate the perspectives of numerous coaching and support staff. When these practitioners operate within an organization where they face relentless pressures to develop successful performers who deliver in the short-term (Cruickshank & Collins, Citation2012), the need to win can permeate into the culture of the organization (Nesti et al., Citation2012). Through Sam’s story, we show how when this ‘need to win’ culture is rewarded with consistent success, stakeholders can become resistant to change and further perpetuate a performance narrative. This presents a complex dilemma for practitioners, as impacting these cultures and organizational practices is a widely argued necessity in the current sporting landscape (Giles et al., Citation2020; Kavanagh et al., Citation2021). Yet, as Sam found, a successful track record can entrench these maladaptive ways of operating, making it complex to alter them. Thus, this study highlights the need for practitioners to work hard to position any desired changes to organizational practice as not hindering performance outcomes, but also having the potential to enhance them, even if the value of change seems undeniable to the practitioner (i.e. enhancing well-being). Such work likely requires the use of broader, more politically astute behavioral skills and points to the varied “hats that practitioners must wear when supporting systems” (Wagstaff & Quartiroli, Citation2023, p. 3).

Indeed, our presentation of Sam’s story depicts them acting from several positions as they attempt to realize changes within the organizational system. For example, attempting to influence on the training and competition environment which was overseen by a longstanding coach openly resistant to such interventions. Sam’s experiences can be aligned with previous research showing the need for practitioners to understand and negotiate intricate socio-political structures and decision-making customs (e.g. Mellalieu, Citation2017), as well as navigate complex cultural dynamics and social hierarchies (Wagstaff & Hays, Citation2020). Sam was able to make progress by remaining reflexive and adaptable, and flexibly walking a “pragmatic middle line” (McKenzie et al., Citation2023, p. 162). Such a stance meant Sam could critically assess their organizational demands and contexts and innovate their practices in line with the realities they face (McDougall et al., Citation2020). This process might also need to be balanced against a potential lack of knowledge or skepticism amongst stakeholders about sport psychology (Johnson et al., Citation2011). In the current study, we show that Sam achieved such a balance by building a firm grasp of their context which they used to integrate the language of the organization into the theory they based their practice upon. Additionally, Sam compromised on certain aspects of this theory and skillfully selected and adapted the psychological concepts to be relevant to their contextual understanding. Through our PR approach, we explore and communicate not only the intricacies of integrating theory into practice, but also how successfully implementing change at a systems level likely requires practitioners to build an in-depth understanding of the culture and practices of the organization, and an appreciation of what it means to be a member of that organization (Daley et al., Citation2020). Thus, this present study extends calls for the training of sport psychologists to include development of professional expertise such as professional judgment and decision making alongside the development of professional competence (Wagstaff & Hays, Citation2020). For example, Wagstaff and Hays (Citation2020) suggested trainee supervision should be expanded to include alumni and experienced professionals who can share their knowledge and competencies on areas such as conflict management, leadership development and succession planning, and working in complex organizational systems. In this way, practitioners may be able to develop “new approaches and new competencies to those usually taught in training programs” (Wagstaff & Quartiroli, Citation2023, p. 2).

In addition to several competencies required to create change at the environmental or systems level, the present study illuminates the need to ensure ownership of change initiatives extend beyond solely the practitioner. While Sam believed they had the support of the wider psychosocial team to progress their thriving project, they ultimately had not secured the necessary buy-in to do so. We propose this is because Sam failed to establish a shared model of practice which undermined their efforts and led to the project failing. By taking charge in this manner, Sam may have unwittingly operated as an individual agent of change (cf. Cruickshank & Collins, Citation2012). Thus, they inadvertently excluded important stakeholders from adding value (Maher, Citation2022), and were not able to adequately shift ownership of psychology to the stakeholders (Daley et al., Citation2020). Yet, we argue it is not simply a process of being more inclusive, as engaging stakeholders to create a shared model of practice is not itself without challenges. Wagstaff and Quartiroli (Citation2023) recommended that organizations implement a model of practice that disperses ownership and responsibility and requires practitioners to strike a balance between what is guided by them, and what is democratized. Further, we showed in the current study that finding such a balance must be weighed up against the speed of change progress, because democratizing change among stakeholders has the potential to slow and even stall the process. Therefore, we recommend that organizations wishing to implement change processes provide opportunity for all voices to be heard, but that there are processes in place to ensure the conversations advance in a timely manner to ensure momentum is maintained.

Our second aim was to explore the utility of thriving research in contributing to a new duty of care. The present observations demonstrate how individual differences can complicate attempts to foster thriving at the environment level, as the systems, histories, and cultures of the sport and organizations might influence athletes differently. To elaborate, strong and supportive interpersonal relationships have previously been suggested as determinants of athlete thriving (see Brown & Arnold, Citation2019; Davis et al., Citation2021; McHenry et al., Citation2020), yet fostering environments that support such interpersonal connections can be complex. Stambulova and Ryba (Citation2013) argued that organizational praxes may dictate how individuals experience these relationships, with senior, experienced athletes able to express themselves more authentically. Indeed, athletes who are more experienced and who have achieved previous high levels of success may use their status as a powerful platform for personal growth (e.g. Jewett et al., Citation2019), and may be able to exert influence within interpersonal relationships more effectively than novice or less established athletes (Collins & Cruickshank, Citation2015). In the current study, the retired athlete group recognized their previous success predisposed their ability to thrive as they were more capable in manipulating interpersonal relationships for their benefit. Thus, practitioners should be cognizant of potential power imbalances among athletes and, when putting support in place, incorporate the perspectives of experienced athletes to create inclusive environments that encourage all members to act authentically (Blodgett et al., Citation2017). Doing so may provide all individuals equal opportunity to thrive and not just those who are already successful.

Alongside the individual differences influencing interpersonal relationships, the exploration of promoting thriving within a specific elite sport context provides support for previous descriptions of thriving as a temporal experience. That is, thriving can be experienced within a specific sporting encounter (Brown et al., Citation2021), or as a more overall perception of high levels of well-being and performance over a longer period (Brown et al., Citation2017, Citation2018). Further, Brown et al. (Citation2018) found sustained experiences of thriving may have an end point which could negatively impact athletes’ well-being and performance. The findings presented here add to this understanding by suggesting that promoting thriving at an environmental level will need to account for meaningful temporal variations in individual athlete’s ability to thrive. To elaborate, Sam recognized the need to place individual subjectivity at the center of their strategy to facilitate thriving as Sam saw the need to incorporate variations in athlete’s experiences of their sporting environment. These variances were found to be contingent on different attitudes and preferences for training, as well as periods of the training and competition cycles, with potentially lower levels of functioning outside of these periods. A novel consideration for those wishing to foster thriving from an environmental level is that achieving thriving may be dependent on the preference an athlete has for these specific time-dependant scenarios, with some athletes only thriving in competition for example. As Sam discovered, these temporal variations are likely to further complicate any attempts by those aiming to create a standardized environment that facilitates thriving for all athletes. Thus, we suggest the subjective, contextualized, and temporal nature of athlete thriving experiences may require the formation of environments that prioritize the principles of thriving (e.g. contextual enablers) but are flexible enough to allow for individual differences and expression within them (cf. Feddersen et al., Citation2021). Indeed, the connection between understanding the athlete as an individual and factors of sporting success and well-being has been shown within elite talent development pathways (e.g. Martindale et al., Citation2013). So, while it may be possible to promote overarching principles of effective practice in promoting thriving, the implementation of these principles within individual contexts may ultimately look different for each sport organization. We therefore recommend practitioners looking to promote thriving ensure that all athletes can communicate their preferences when designing change initiatives. Such approaches have proven effective in promoting the holistic development of athletes in academy and elite pathways (e.g. Stambulova et al., Citation2021).

Limitations

PR approaches are typically characterized by the involvement of multiple intended beneficiaries, users, and stakeholders of the research in all aspects of the research process (Seguin & Culver, Citation2022; Van Slingerland et al., Citation2021). Within the current study, the co-researchers are limited to a single practitioner. As such, absent from our approach are the voices of other stakeholders (e.g. coaches, support staff) that may have been able to contribute valuable insight and knowledge to the project. Although we acknowledge that this is a limitation of our participatory work, it is important to note the specific context within which this study occurred. Senior leadership of the organization had delegated responsibility for the implementation of organizational change to the sport psychologist and as such, our ‘stakeholders’ were limited to the psychologist. As a result of wider organizational and interpersonal dynamics that were beyond our control, we were not provided broader access to the organization. In addition, this study took place during the COVID-19 pandemic which further hindered our ability to widen participation. Despite these issues, we did encourage more voices to be included and were somewhat successful (i.e. retired athlete group, athlete pilot group, neophyte practitioners).

Conclusion

The aim of the current study was to use collaborative inquiry to explore the experiences of a sport psychology practitioner integrating theory into practice within an Olympic Sport organization in the UK and to understand the utility of thriving within these settings. Through the experiences shared, this study provides novel insights into the realities of creating systems-level change and suggest several considerations for sport organizations and applied practitioners wishing to facilitate athlete thriving. The findings demonstrate the need for practitioners to deftly negotiate complex interpersonal relationships and organizational cultures when advocating for, instigating, and maintaining change on a systems level. In doing so, this study draws attention to how practitioners within multidisciplinary coaching and support teams need to democratize responsibility for psychological change and continually balance and rationalize their decisions amidst complex and challenging scenarios. Regarding thriving, organizations and practitioners wishing to promote thriving at an environmental should recognize the effective promotion of thriving requires an intimate, in-depth understanding of how the contextual enabler variables are embedded within the organizational systems. Further, thriving is a subjective experience and requires consideration of a diverse array of athlete perspectives when determining what contributes to and constitutes a thriving experience.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Due to the collaborative and participatory nature of the research, supporting data is not available due to ethical restrictions that prevent the sharing of the data. Notably, the need to protect the identity of participants, organizations, and national governing bodies involved in the research project. The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- Agar, M. (1995). Literary journalism as ethnography. In J. Van Maanen (Ed.), Representation in ethnography (pp. 112–129). Sage.

- Arnold, R., Collington, S., Manley, H., Rees, S., Soanes, J., & Williams, M. (2019). The team behind the team”: Exploring the organizational stressor experiences of sport science and management staff in elite sport. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 31(1), 7–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2017.1407836

- Arnold, R., & Fletcher, D. (2021). Stressors, hassles, and adversity. In R. Arnold & D. Fletcher (Eds.), Stress, well-being, and performance in sport (pp. 31–62). Taylor & Francis.

- Bhavnani, K. (1994). Tracing the contours: Feminist research and objectivity. In H. Afshar & M. Maynard (Eds.), The dynamics of race and gender: Some feminist interventions (pp. 25–40). Taylor and Francis.

- Blodgett, A. T., Ge, Y., Schinke, R. J., & McGannon, K. R. (2017). Intersecting identities of elite female boxers: Stories of cultural difference and marginalization in sport. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 32, 83–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2017.06.006

- Bray, J. N., Lee, J., Smith, L. L., & Yorks, L. (2000). Collaborative inquiry in practice: Action, reflection, and making meaning. Sage.

- Brown, D. J., & Arnold, R. (2019). Sports performers’ perspectives on facilitating thriving in professional rugby contexts. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 40, 71–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2018.09.008

- Brown, D. J., Arnold, R., Fletcher, D., & Standage, M. (2017). Human thriving: A conceptual debate and literature review. European Psychologist, 22(3), 167–179. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040/a000294

- Brown, D. J., Arnold, R., Reid, T., & Roberts, G. (2018). A qualitative exploration of thriving in elite sport. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 30(2), 129–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2017.1354339

- Brown, D. J., Arnold, R., Standage, M., & Fletcher, D. (2021). A longitudinal examination of thriving in sport performers. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 55, 101934. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2021.101934

- Brown, D. J., Arnold, R., Standage, M., Turner, J. E., & Fletcher, D. (2021). The prediction of thriving in elite sport: A prospective examination of the role of psychological need satisfaction, challenge appraisal, and salivary biomarkers. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 24(4), 373–379. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2020.09.019

- Brown, D. J., Passaportis, M. J. R., & Hays, K. (2021). Thriving. In R. Arnold & D. Fletcher (Eds.), Stress, well-being, and performance in sport (pp. 297–312). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429295874

- Cahill, C. (2007). Participatory data analysis: Based on work with the fed up honeys. In Participatory action research approaches and methods: Connecting people, participation and place (pp. 181–187). Routledge.

- Cargo, M., & Mercer, S. L. (2008). The value and challenges of participatory research: Strengthening its practice. Annual Review of Public Health, 29(1), 325–350. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.091307.083824

- Cavallerio, F. (2022). Creative nonfiction in sport and exercise research. Routledge.

- Collins, D., & Cruickshank, A. (2015). Take a walk on the wild side: Exploring, identifying, and developing consultancy expertise with elite performance team leaders. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 16(P1), 74–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2014.08.002

- Cornwall, A., & Jewkes, R. (1995). What is participatory research? Social Science & Medicine (1982), 41(12), 1667–1676. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(95)00127-S

- Cruickshank, A., & Collins, D. (2012). Culture change in elite sport performance teams: Examining and advancing effectiveness in the new era. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 24(3), 338–355. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2011.650819

- Daley, C., Ong, C. W., & McGregor, P. (2020). Applied psychology in academy soccer settings: A systems-led approach. In J. G. Dixon, J. B. Barker, R. C. Thelwell, & I. Mitchell (Eds.), The psychology of soccer (pp. 153–172). Routledge.

- Davis, L., Brown, D. J., Arnold, R., & Gustafsson, H. (2021). Thriving through relationships in sport: The role of the parent – athlete and coach – athlete attachment relationship. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 694599. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.694599

- Diment, G., Henriksen, K., & Larsen, C. H. (2020). Team Denmark’s sport psychology professional philosophy 2.0. Scandinavian Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 2, 26–32. https://doi.org/10.7146/sjsep.v2i0.115660

- Durand-Bush, N., Baker, J., van den Berg, F., Richard, V., & Bloom, G. A. (2023). The gold medal profile for sport psychology (GMP-SP). Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 35(4), 547–570. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2022.2055224

- Everard, C., Wadey, R., Howells, K., & Day, M. (2022). Construction and communication of evidence-based video narratives in elite sport: Knowledge translation of sports injury experiences. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 35(5), 731–754. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2022.2140225

- Feddersen, N. B., Morris, R., Storm, L. K., Littlewood, M. A., & Richardson, D. J. (2021). A longitudinal study of power relations in a British Sport Organisation. Journal of Sport Management, 35(4), 312–324. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2020-0119

- Feeney, B. C., & Collins, N. L. (2015). A new look at social support: A theoretical perspective on thriving through relationships. Personality and Social Psychology Review: An Official Journal of the Society for Personality and Social Psychology, 19(2), 113–147. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868314544222

- Fine, M., Torre, M. E., Boudin, K., Bowen, I., Clark, J., Hylton, D., Martinez, M., ‘Missy’, Rivera, M., Roberts, R., Smart, P., & Upegui, D. (2003). Participatory action research: Within and beyond bars. In P. Camic, J. Rhodes, & L. Yardley (Eds.), Qualitative research in psychology: Expanding perspectives in methodology and design (pp.173–198). American Psychological Association.

- Fletcher, D., & Arnold, R. (2011). A qualitative study of performance leadership and management in Elite Sport. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 23(2), 223–242. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2011.559184

- Giles, S., Fletcher, D., Arnold, R., Ashfield, A., & Harrison, J. (2020). Measuring well-being in sport performers: Where are we now and how do we progress?. Sports Medicine, 50(7), 1255–1270. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-020-01274-z

- Graneheim, U. H., Lindgren, B.-M., & Lundman, B. (2017). Methodological challenges in qualitative content analysis: A discussion paper. Nurse Education Today, 56, 29–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2017.06.002

- Graneheim, U. H., & Lundman, B. (2004). Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today, 24(2), 105–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001

- Gucciardi, D. F., Stamatis, A., & Ntoumanis, N. (2017). Controlling coaching and athlete thriving in elite adolescent netballers: The buffering effect of athletes’ mental toughness. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 20(8), 718–722. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2017.02.007

- Harris, M., Myhill, M., & Walker, J. (2012). Thriving in the challenge of geographical dislocation: A case study of elite Australian footballers. International Journal of Sports Science, 2(5), 51–60. https://doi.org/10.5923/j.sports.20120205.02

- Henriksen, K. (2015). Developing a high-performance culture: A sport psychology intervention from an ecological perspective in elite orienteering. Journal of Sport Psychology in Action, 6(3), 141–153. https://doi.org/10.1080/21520704.2015.1084961

- Henriksen, K., Schinke, R., Moesch, K., McCann, S., Parham, W. D., Larsen, C. H., & Terry, P. (2020). Consensus statement on improving the mental health of high performance athletes. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 18(5), 553–560. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2019.1570473

- Henriksen, K., Stambulova, N., & Roessler, K. K. (2011). Riding the wave of an expert: A successful talent development environment in kayaking. The Sport Psychologist, 25(3), 341–362. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.25.3.341

- Jewett, R., Kerr, G., & Tamminen, K. (2019). University sport retirement and athlete mental health: A narrative analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(3), 416–433. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2018.1506497

- Johnson, U., Andersson, K., & Fallby, J. (2011). Sport psychology consulting among Swedish premier soccer coaches. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 9(4), 308–322. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2011.623455

- Kavanagh, E., Rhind, D., & Gordon-Thomson, G. (2021). Duties of care and welfare practices. In Arnold, R & Fletcher, D (Eds.), Stress, well-being, and performance in sport (pp. 313–331). Routledge.

- Keegan, R. J., Cotteril, S., Woolway, T., Appaneal, R., & Hutter, V. (2017). Strategies for bridging the research-practice ‘gap’ in sport and exercise psychology. Revista de Psicología Del Deporte, 26, 75–80.

- Keegan, R., Spray, C., Harwood, C., & Lavallee, D. (2010). The motivational atmosphere in youth sport: Coach, parent, and peer influences on motivation in specializing sport participants. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 22(1), 87–105. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200903421267

- Kinoshita, K., MacIntosh, E., & Sato, S. (2021). Thriving in youth sport: The antecedents and consequences. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 20(2), 356–376. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2021.1877327

- Krizek, R. (1998). Lessons. In A. Banks & S. Banks (Eds.), Fictions and social research (pp. 89–113). Altamira Press.

- Larsen, C. H. (2017). Bringing a knife to a gunfight: A coherent consulting philosophy might not be enough to be effective in professional soccer. Journal of Sport Psychology in Action, 8(2), 121–130. https://doi.org/10.1080/21520704.2017.1287142