Abstract

The overall aim of this two-part study was to develop an intervention targeting sports coaches’ mindsets about their talent as a coach (coach talent mindset, C-TM) and their athletes’ talent (athlete talent mindset, A-TM), called the GrowTMindS Intervention. In this Part I, the intervention was developed drawing on a user-centered design approach and implemented in a coach education program in Norway. The study involved 31 coaches (5 women, 26 men) from 22 to 69 years of age, representing the sports of bandy, golf, ski sports, swimming, and volleyball. Using a mixed-methods approach, the quantitative results showed that the coaches increased their A-TM from pretest to post-test, while their C-TM, which was high at baseline, remained more challenging to target. The qualitative findings helped us understand how most coaches, through reflective processes, perceived the delivery of the intervention as sense-making and substantiated their commitment to growth talent mindsets. The qualitative findings also highlighted areas for refinement and tailoring of the intervention to target all coaches’ talent mindsets. Overall, the study was considered a necessary first step in developing an intervention showing significant and meaningful changes in coaches’ self-reported talent mindsets, consistent with the guidelines of wise psychological intervention and behavior change.

Lay Summary

This study focuses on the design and development of the GrowTMindS Intervention, which aims to develop sports coaches’ growth mindsets about their talent as a coach and their athletes’ talent. The quantitative results helped us evaluate the numeric increase in talent mindsets, while the qualitative findings provided useful insight for further optimization.

IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE

This study suggests and elaborates on how a coach education program should be developed upon a sound theoretical framework of psychology, i.e., wise psychological intervention and mindset, to develop coach behavior.

The study is especially relevant for those responsible for coach education programs or intervention research and others working toward coach and athlete development.

Introduction

Developing coach behavior through coach educational programs (CEP; e.g., Stodter & Cushion, Citation2014) or targeted interventions (Langan et al., Citation2013) seems challenging, and as early as Citation2003 Cushion et al. flagged the risk of getting a “souped up version of the same” (p. 216) if we do not rethink CEPs. Now, two decades later, CEPs still seem to struggle with embracing the complexity needed to prepare coaches for coaching, and a top-down approach in the education design prevents coaches from transferring behavior and philosophies communicated at a CEP into real coaching situations (Solstad et al., Citation2017). At the same time, research shows how a coach-created motivational climate is associated with more adaptive and maladaptive motivational outcomes for the athletes (Vella et al., Citation2016), and early talent identification and specialization are considered problematic regarding athletes learning and development in addition to adverse outcomes such as injuries or drop-out (LaPrade et al., Citation2016). To address these challenges, this two-part series of articles draws on an approach stemming from social psychology (Walton, Citation2014) and how well-designed interventions have proven to have considerable effect by targeting a specific problem and the cognitive processes that underlie it (Harackiewicz & Priniski, Citation2018; Walton & Wilson, Citation2018). In particular, grounded in the psychological theory of mindsets (Dweck, Citation2000, Citation2006; Nilsen et al., Citation2023) and the theoretical foundation of how to design wise psychological interventions (Walton, Citation2014; Walton & Wilson, Citation2018; Yeager et al., Citation2016), the aim was to design and develop an intervention targeting sports coaches’ mindsets with implications for the effect of participation in a CEP and their engagement in athletes’ participation and learning in sports, ready for testing in a Phase III efficacy trial (Czajkowski & Hunter, Citation2021).

Mindsets

Mindsets, previously referred to as implicit beliefs, have been identified as serving an organizational role, connecting goals, beliefs, and behavior into a meaning system of personal characteristics, such as intelligence and personality, or talents and abilities (Dweck, Citation2006; Molden & Dweck, Citation2006). An individual may find two types of mindsets plausible in the specific domain (Yeager & Dweck, Citation2012), but one type seems more dominantly positioned on a continuum from a fixed mindset to a growth mindset (Murphy & Reeves, Citation2019). At one end of the continuum, in terms of individuals’ beliefs in talent and abilities, those having more of a fixed mindset believe these to be innate capacities that one possesses to a certain extent. At the other end, individuals who tend toward a growth mindset believe that innate talents and abilities are changeable and can be enhanced through diligent effort and practice (Dweck, Citation2000, Citation2006).

Concerning the significance of mindsets, extensive research from two eras implies that the meaning system adopted by individuals can affect their development and learning processes (Dweck & Yeager, Citation2019). While most studies pertaining to Dweck’s conceptualization of mindsets are rooted in academic settings, research in sports substantiates these findings. For instance, a meta-analytic review provided by Vella et al. (Citation2016) corroborates the application of how distinct mindsets serve different goals and how the goals lead to different behavioral patterns, as proposed by Dweck (Citation1986) in her seminal work. By primarily using two separate subscales when assessing and interpreting individuals’ fixed and growth mindsets, the findings suggest that individuals holding more of a fixed mindset are more likely to adopt performance goals, which often align with maladaptive strategies (Dweck, Citation2000, Citation2006). This can involve avoiding challenging tasks due to fear that failure might indicate inherent limitations, or attempting manageable tasks to surpass others for positive reinforcement due to normative standards of excellence. Conversely, individuals holding more of a growth mindset are more likely to adopt learning goals associated with adaptive strategies (Dweck, Citation2000, Citation2006). These individuals demonstrate more persistence and do not fear making mistakes or showing personal shortcomings, which leads them to seek out challenging tasks as they present significant learning opportunities.

By considering previous mindset research, Dweck (Citation2006, Citation2009) argues that coaches may adopt more of a fixed or a growth mindset about athletic talent, which influences their goals, beliefs, and behavior concerning their athletes. Knowing that the coach is identified as a key influencer in athletes’ sports experiences (Horn, Citation2008) and potentially in shaping their athletes’ mindsets (Slater et al., Citation2012), research on the coaching role thus appears central. Such an impression is strengthened by the lack of research directed toward coaches’ mindsets, which draws on Dweck’s work conceptually and empirically when investigating how coaches’ mindsets influence their everyday work with their athletes (Vella et al., Citation2016).

Indeed, Nilsen et al. (Citation2023) addressed this research gap when operationalizing coaches’ mindsets about athletic talent (athlete talent mindset; A-TM). Consistent with mindset research in other domains, they also assessed coaches’ mindsets using a short continuous scale, where a low or a high score represents more of a fixed or a growth A-TM, respectively (Dweck et al., Citation1995; see also the section on measurement). It is worthy of note that, when surveying 3830 coaches in Norway, Nilsen et al. (Citation2023) found that coaches who reported a lower score, tending toward a fixed A-TM, believed they could identify talented athletes at an early age to a greater extent than coaches with a higher score leaning toward a growth A-TM. By following the extensive literature on talent identification and development, Nilsen et al. (Citation2023) argue that coaches with a fixed A-TM may be concerned about identifying and selecting talents at young ages to secure a long period of deliberate practice and future elite sports success. Conversely, coaches with a growth A-TM may not believe in the detectability of athletic talent, or they resist considering such athlete knowledge when perceiving their athletes’ potential and hence focus on the development of all athletes independent of early signs of giftedness or early competitive success. Thus, A-TM can be of great importance for coaches’ talent identification and the extent to which they provide all athletes with equal opportunities regardless of whether they showcase extraordinary abilities at a young age (Nilsen et al., Citation2023).

The implications of coaches’ mindsets are also supported by research on organizations and managers (Murphy & Reeves, Citation2019), indicating that the mindset held by coaches influences how the culture endorses more of a fixed or a growth mindset through how they work with their athletes’. For instance, coaches holding more of a growth A-TM may (to a greater extent than those with a fixed A-TM) contribute to athletes’ continuous improvement by motivating them to strive for and overcome challenges and being more open to new training methods (Heslin et al., Citation2005, Citation2006). This also coincides with the study by Vella et al. (Citation2014), where, after an extensive literature review, they elaborate on how coaches can create environments that substantiate a growth mindset in their athletes. In addition to elaborating on how coaches can help their athletes handle challenges and be patient, the authors discuss how coaches can contribute to athletes’ learning through how they value failure and perception of success, the promotion of learning goals, and showcasing high and tailored expectations related to their development of abilities. Given the challenges associated with coaches in youth sports contributing to talent identification and specialized training and the potential adaptive outcomes a growth A-TM might have on athletes’ development and learning, it can thus be significant for coaches to believe in athletes’ talents as malleable (Nilsen et al., Citation2023).

By following up on the possible implications of coaches’ A-TM regarding talent identification, coaches’ mindsets about themselves as coaches (coach talent mindset; C-TM) may also influence their decisions when selecting (or deselecting) athletes in competitive situations. Considering Dweck (Citation2000, Citation2009), this is because coaches holding a fixed C-TM may select “the best” athletes as their success revolves around winning rather than ensuring equal developmental opportunities for everyone, and because they (compared to those with a growth C-TM) to a greater extent perceive loss as a personal defeat or deficiency. Furthermore, coaches’ C-TM may also be important for their development and learning. Dweck (Citation2006) and Chase (Citation2010), for instance, argue that coaches with a fixed C-TM may believe that leadership abilities are an innate quality and that some are “born to be coaches.” In contrast, coaches with a growth C-TM believe that leadership abilities can be learned and gained through hard work and new experiences. Hence, it may be crucial for coaches’ learning and for the CEP to be effective that the participants genuinely desire to develop and believe in their coaching talent as malleable.

While it seems liable to assume that coaches’ mindsets also will influence their athletes’ mindsets, it is uncertain exactly how this unfolds. For example, researchers have revealed a discrepancy between the mindset held by parents (Gunderson et al., Citation2013) or teachers (Sun, Citation2019) and the communicated mindset messages perceived by their children or students, respectively. Such discrepancy may be caused by the challenge of communicating mindset messages following the mindset one holds, as suggested by Vella et al. (Citation2014). At the same time, given that the coaches also have a C-TM that influences their goals, beliefs, and behavior, coaches who embrace a fixed C-TM may communicate fixed talent mindset messages in situations where their mindset is challenged, influencing the outcome concerning themselves and how their athletes perceive them. Hence, considering the domain-specificity of a personal mindset (Molden & Dweck, Citation2006), coaches’ mindsets about their talents as coaches appear pertinent to this study. In recap, with the knowledge that coaches’ talent mindsets may entail significant consequences for the coaches themselves and their athletes, improving CEPs to target these beliefs and to help coaches develop a growth C-TM and A-TM may be beneficial concerning optimal coach and athlete development (see Chase, Citation2010; Dweck, Citation2006; Nilsen et al., Citation2023; Vella et al., Citation2014; Citation2016).

Growth-mindset interventions

Personal mindsets are considered to be relatively stable dispositions (Dweck, Citation2000). However, they can be influenced by messages communicated in a specific context, such as by an organization (see Murphy & Reeves, Citation2019), or by being induced toward a growth mindset in a well-designed intervention, i.e., a growth mindset of intelligence intervention (growth-mindset intervention; see Dweck & Yeager, Citation2019; Yeager et al., Citation2016). The growth-mindset intervention is rooted in the growing research on wise psychological interventions (see Walton & Wilson Citation2018 for an account of wise psychological interventions). In short, wise psychological interventions pertain to how an intervention aims to target a specific meaning individuals hold about themselves, others, or a distinctive situation, using techniques to counteract this meaning and alter a new meaning (Walton, Citation2014). Central to the intervention is how it addresses the underlying psychological processes identified as a potential problem, as these may, for instance, inhibit the individual socially or prevent them from developing (Walton, Citation2014). The term wise entails that the messages communicated regarding the new meaning appear “wise to” the individual without implying that such meaning is superior to other perspectives or that different viewpoints are incorrect (Walton, Citation2014). This is central to changing individuals’ meanings through intended processes, as a lack of targeting may, as we will return to, undermine such processes and thereby lower the effectiveness of the intervention (Walton, Citation2014; Walton & Wilson, Citation2018).

The growth-mindset intervention may concern how individuals’ beliefs about intelligence as fixed influence their learning strategies and academic outcome, which becomes a social problem as groups, due to their inherent belief, underperform when compared to others believing it is malleable (e.g., African American students compared to their White counterparts; Aronson et al., Citation2002). The intervention typically counteracts the participants’ fixed mindset by introducing scientific facts about the problem being targeted (Yeager et al., Citation2016), such as brain plasticity and how intelligence can be developed by exercise, like a muscle (e.g., stereotype threats; Aronson et al., Citation2002). In these targeted interventions, the use of direct persuasion is minimized, as such methods can be experienced as controlling or stigmatizing and then have a small and short-lived effect (Aronson, Citation1999; Walton & Wilson, Citation2018), especially among adolescents or adults (Yeager et al., Citation2018). Instead, they utilize a source that individuals most often consider as trustworthy, respected, and liked, namely, themselves (Heslin et al., Citation2005), by facilitating self-persuasion methods that lead the participant to commit themselves to new ideas via cognitive dissonance processes (Aronson, Citation1999; Walton & Wilson, Citation2018). Therefore, to follow up the scientific testimony and help the participants internalize communicated messages (Walton, Citation2014; Yeager et al., Citation2016)—by drawing on Heslin et al. (Citation2005)—the intervention may include exercises such as counter-attitudinal reflection, counter-attitudinal idea generation, and counter-attitudinal advocacy.

The growth-mindset intervention has been tailored and developed through a process containing laboratory studies, small-scale field studies, and scaled-up field studies (see Walton & Wilson Citation2018 for an overview). Such a thorough approach is highlighted as necessary to optimize the effect of the growth-mindset intervention (Dweck & Yeager, Citation2019) as well as other behavioral interventions (Czajkowski & Hunter, Citation2021) before being tested in a more rigorous randomized design, referred to as a Phase III efficacy trial. Various models of behavioral intervention research elaborate on the developmental process, consisting of the design and development phase and preliminary testing. The first test typically consists of sequential nonrandomized and uncontrolled small-N studies, ensuring the flexibility to refine the intervention’s content and delivery, in addition to discovering and correcting any failure that may occur (see Czajkowski & Hunter, Citation2021 for an overview). The aim is to avoid problems related to, for example, duration and delivery (Czajkowski & Hunter, Citation2021) or other barriers preventing the behavior from accruing over time (Yeager et al., Citation2016) and thereby increase and verify the chance of achieving meaningful impact, i.e., develop behavioral change according to the theoretical framework of the study, in addition to showing statistically significant changes.

While theoretical expertise is considered crucial to guide a developmental process, it is also emphasized that users’ subjective experiences are needed to customize the delivery for a given population and precisely target the particular problem of the intervention (Yeager et al., Citation2016). Design thinking has gained increasing attention, especially for involving users in innovative and customer-focused problem-solving processes to respond to changing environments and create maximum impact (Razzouk & Shute, Citation2012). Design thinking is also considered valuable when combined with scientific thinking in designing educational programs (Owen, Citation2007), which Yeager et al. (Citation2016) utilized when they applied a qualitative user-centered design to redesign the original growth-mindset intervention. Such an approach builds on the belief that participants may not have prior access to the information that would make them adopt, for example, a growth C-TM or A-TM (see Wilson, Citation2002; Yeager et al., Citation2016); however, they are excellent reporters of action, and their experiences are considered significant for providing insightful data for further improvement (Ries, Citation2011; Yeager et al., Citation2016).

Taken together, following the presented mindset literature (Chase, Citation2010; Dweck, Citation2006; Nilsen et al., Citation2023) and the theoretical foundation of wise psychological interventions (Walton & Wilson, Citation2018; Yeager et al., Citation2016), the purpose of this two-part study was to design and develop the Growth Talent Mindsets for Sports Coaches Intervention (the GrowTMindS Intervention) targeting adult sports coaches’ C-TM and A-TM in the context of Norwegian sport. More concretely, by dividing the developmental process into a design and developmental phase followed up by two small-scale field studies, drawing on the guidance of Czajkowski and Hunter (Citation2021), we sought to identify and incorporate potential beneficial information from the participants to optimize the intervention’s effect, before testing it in a potential Phase III randomized trial. In this regard, an important part of evaluating the effect involves assessing whether a change in mindset constitutes a statistically significant change and whether the change is meaningful according to the theoretical foundation based on Dweck’s conceptualization of mindset. The current article focuses on the design and developmental process and the evaluation of the first-time implementation of the intervention.

Methodology

A mixed methods approach was selected for this two-part study, guided by a pragmatic philosophical assumption (Creswell & Clark, Citation2017). A pragmatic stance implies that the researchers recognize quantitative and qualitative paradigms’ epistemological and ontological distinctions. However, it posits that the practicality and profitability of combining both methods are subordinate to the pressing need to address the research questions effectively (Creswell & Clark, Citation2017). Hence, consistent with pragmatism, the researchers acknowledged and sought to find meaning in both the quantitative and qualitative data in line with the overarching purpose of the study and the research questions that are appropriate to the investigation (Creswell & Clark, Citation2017).

Inspired by the user-centered design approach (see Yeager et al., Citation2016), we began by designing and developing the GrowTMindS Intervention. As the psychological process model of influencing participants’ mindsets had been clearly defined and tested in previous research (Yeager et al., Citation2016), the existing growth-mindset interventions were a preferred starting point. In accordance with how motivational variables typically are measured in research and how the impact of wise psychological interventions usually are assessed, quantitative data were then collected to evaluate the differences in coaches’ talent mindsets alongside and followed up on the implementation. We hypothesized that the coaches’ growth C-TM and A-TM scores would increase by participating in the intervention.

In line with the qualitative user-centered design tradition (Yeager et al., Citation2016), qualitative research methods were embedded within the quasi-experimental design to investigate coaches’ subjective experiences of the intervention. The present research, therefore, draws on a complex mixed-methods intervention design approach (Creswell & Clark, Citation2017). Two research questions guided the qualitative process. First, we aimed to understand the delivery by investigating the coaches’ experiences of the intervention and the intervention material. In alignment with the user-centered design approach, by investigating coaches’ experiences after participation rather than asking them about their preferences beforehand (Yeager et al., Citation2016), this part draws on deductive conclusions using qualitative data from coaches reflecting on their participation in a theoretically informed intervention. Second, we aimed to obtain an understanding of the intervention and investigate to what extent the intervention (i.e., the self-persuasive methods) led the coaches to a growth C-TM and A-TM via cognitive dissonance processes or what may prevent such processes. This part complements the quantitative data in evaluating the effect of the intervention, which is considered important given the weaknesses associated with the developmental process and the study design. Furthermore, using qualitative data was assumed valuable to expand our insight into the theoretical and conceptual framework underpinning the intervention.

Participants

The participants were recruited from a population of 43 coaches beginning a CEP. Of these, 31 coaches (72.1%; 5 women, 26 men) aged 22–69 years of age (Mdn = 36.0; M = 36.2; SD = 10.23) consented to participate in the study. The sample coaches represented the sports of bandy, golf, ski sports, swimming, and volleyball. They reported experience of coaching athletes in one or more age groups (under 6 years of age = 32.3%, between 6 and 12 years of age = 83.9%, between 13 and 19 years of age = 74.2%, and 20 years of age or above = 54.8%) at one or more levels (local = 100.0%, regional = 29.0%, national = 16.1%, and international = 6.5%). All coaches had completed sport-specific coaching education at Level 1 according to Norway’s four-tier coach certification, which is a requirement to start at the CEP in the current study at Level 2. Regarding their general education, 32.3% had completed upper secondary school, 35.5% had completed university/college up to 4 years, 29.0% had completed university/college 5 years or more, and 3.2% reported other types or levels of general education.

Procedure

The intervention was designed as part of an already existing CEP offered in collaboration between a university college and five national sports federations, aimed at coaches of athletes aged from 13 to 19 years. Considering that coaches in Norwegian sports must complete one level to advance to the next level of the four-tier coach certification system, some coaches may have athletes at a higher level or age than what is applicable for Level 2. The CEP was a six-month online program, including two in-person gatherings for all coaches at the beginning and end. In addition, each federation held an in-person gathering during the course focusing on sport-specific content such as technique and tactics.

All coaches attending the CEP were informed that the purpose of the study was to investigate how sports coaches motivate and think about themselves and their athletes. During the informed consent process, the coaches were informed that everyone would undergo the same coach educational program regardless of their involvement in the study. Additionally, it was emphasized that participation in the study was voluntary, that choosing not to participate would not impact their education, and that they could withdraw at any time without repercussions. The study was carried out after approval by the Norwegian Center for Research Data (No. 976146) and the ethical committee at the Norwegian School of Sport Sciences (No. 49-200318).

The research group (consisting of the authors of this article) led the study and contributed extensive collective experience as sports coach educators and developers, sports psychology consultants, and sports coaches. The first and second authors (hereafter referred to as coach educators) were responsible for implementing the intervention. Two external groups of administrative representatives and sports representatives were also created to receive context-specific and trustworthy knowledge that is assumed to be critical when tailoring interventions targeting participants’ mindsets (Yeager & Walton, Citation2011). The university college and each collaborating federation were represented in the administrative group, and three national team coaches and two elite athletes constituted the sports-specific group. These individuals were well-known profiles for the sports represented in this study and were generally associated with a growth mindset. The administrative group was involved throughout the regulatory meetings, while a semi-structured interview with the sports profiles was carried out prior to the intervention. As previous research had positive experiences of using stories endorsed by influential role models (Yeager et al., Citation2016), these interviews were video-recorded and later used in the intervention (Nilsen, Citation2018).

Design methodology

In addition to a comprehensive literature review, researchers with experience developing and implementing mindset interventions were contacted in the startup phase. This initial work and the knowledge provided by the administrative and sports-specific groups substantiated the design and developmental process of a three-step growth talent mindsets workshop that took place at the first in-person gathering for the CEP. Three follow-up assignments from the CEP were also adapted to the intervention. The detailed design methodology under scrutiny for investigation in this study can be found in Supplementary Material A.

Quantitative data collection and analysis

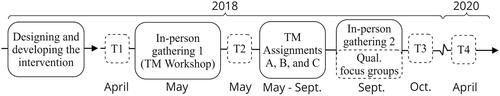

The quantitative data were collected at four different times: (T1) prior to the talent mindset workshop, (T2) immediately after the talent mindset workshop, (T3) immediately after the second in-person gathering, and (T4) a follow-up two years after the talent mindset workshop ().

Figure 1. The timeline illustrates the design and developmental process of the GrowTMindS Intervention, in addition to the sequential implementation of the Talent Mindsets Workshop at the first in-person gathering and the following Talent Mindsets assignments (A, B, and C). In addition, it illustrates the collection of quantitative data at T1, T2, T3, and T4, and the qualitative data at the last in-person gathering.

Measurement

In line with how this study draws on the work of Dweck conceptually and empirically, modified versions of the Theories of Intelligence Scale (Dweck, Citation2000) assessed the participants’ talent mindsets, referred to as the Athlete Talent Mindset Scale and Coach Talent Mindset Scale. The Athlete Talent Mindset Scale was adapted to examine coaches’ A-TM as part of a national survey of coaches (Chroni et al., Citation2018), with data on coaches’ mindsets reported in detail by Nilsen et al. (Citation2023). The adaptation process involved reviewing the questionnaire items through personal discussions with Dweck (see Nilsen et al., Citation2023) and translating them back-to-back for English and Norwegian versions, a process important for maintaining construct validity (Chapman & Carter, Citation1979). The survey questionnaire development involved a four-step process, including pilot testing, before launching (see Chroni et al., Citation2018 for details).

Although the Theories of Intelligence Scale consists of eight fixed and growth mindset items, Nilsen et al. (Citation2023) used two fixed mindset items when assessing coaches’ A-TM. Using a small number of items is preferable because respondents may find it confusing or boring to relate to a mindset as a simple unitary theme and because removing items does not reduce internal reliability (Dweck et al., Citation1995). Furthermore, because using fixed and growth mindset items can create acquiescence bias, researchers usually use fixed mindset items when measuring individuals’ mindsets (Dweck et al., Citation1995). Such an approach is justified by validity tests indicating that individuals’ disagreement with fixed mindset statements is interpretable as agreement with growth mindset statements (Dweck et al., Citation1995), forming the basis for measuring and reporting individuals’ mindsets in multiple samples (e.g., Aronson et al., Citation2002; Claro et al., Citation2016; Dweck et al., Citation1995; Heslin et al., Citation2005; Yeager et al., Citation2016). When assessing coaches A-TM, The Athlete Talent Mindset Scale showed satisfactory skewness (−0.50 to −0.62) and kurtosis (−0.42 to −0.70; George & Mallery, Citation2020), and internal consistency (α = .78; Cronbach, Citation1951; Nilsen et al., Citation2023).

By drawing on Nilsen et al. (Citation2023), the participant in the current study marked their level of agreement for four fixed A-TM items on a six-point Likert scale (e.g., Talent is something about the athlete that he/she cannot change very much), ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree) when responding to the Athlete Talent Mindset Scale. The Coach Talent Mindset Scale assessing coaches C-TM was equivalent in format to the one measuring A-TM and was through a similar procedure regarding translation to ensure construct validity; however, the four fixed coach mindset items were directed toward the coaches’ mindset about their talent as a coach (e.g., Your talent as a coach is something about you that you can’t change much). Consistent with how previous research has calculated growth mindset scores when using fixed mindset items (Claro et al., Citation2016), Growth C-TM and A-TM scores were calculated by reversing and averaging the four items into one scale, where a higher score corresponded to more growth talent mindsets.

Given that previous research involving teachers (Sun, Citation2019) and coaches (Nilsen et al., Citation2023) discusses potential challenges related to socially desirable answers, the Norwegian short version of the Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale (Rudmin, Citation1999) was applied to identify a potential social desirability bias. This version contains ten items, of which five are reversed, and the respondent marks their answers by agreeing or disagreeing with the statements (e.g., No matter who I’m talking to, I’m always a good listener). By drawing on Abrahamsen et al. (Citation2008) use of the scale in Norwegian sport, a four-point Likert scale was used, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). The social desirability index was computed by reversing half of the items before calculating the mean score, which means that a higher score corresponds to a more socially desirable answer. Coaches’ social desirability index was controlled at T1, T3, and T4.

Data analysis

The data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics (version 26) and Mplus (version 8.4). We first screened the data for missing values and outliers and checked for normality and internal consistency (Cronbach’s α; Field, Citation2018). When outliers were detected, a closer inspection did not reveal any errors or out-of-range values. Despite one C-TM variable showing kurtosis outside what is considered acceptable regarding normality (± 2.0; George & Mallery, Citation2020), all data were retained as the values of skewness and kurtosis were expected considering that the sample consisted of adult coaches and because it was assumed to have no significance for planned analyses (C-TM, skewness = −1.15 to 0.14, kurtosis = −0.61 to 2.39; A-TM, skewness = −0.32 to −0.20, kurtosis = −0.47 to 1.96; social desirability scale, skewness = −0.06 to 0.32, kurtosis = −0.88 to −0.24). Cronbach’s α for A-TM ranged between .77 and .89 while the range for C-TM was between .67 and .90. The social desirability scale showed an adequate (α = 0.59 to 0.69) and comparable internal reliability with previous research (Abrahamsen et al., Citation2008; Rudmin, Citation1999).

To investigate potential changes within different types of mindsets (coach and athlete) during the intervention period, we specified two Bayesian two-level longitudinal models in Mplus (Muthen & Muthen, 1998–Citation2022). In the specification of the model, fixed and growth mindsets were, on the within-person level (level 1), regressed on time to indicate potential change in these variables over time. These change parameters were, in turn, nested within participants (level 2). We applied the Bayesian framework for all statistical analyses. One main difference between the Bayesian statistical approach and the more traditional frequentist approach is that they are based on different statistical assumptions (e.g., Stenling et al., Citation2015). In comparison to the frequentist approach, one of the advantages of the Bayesian approach is that it has an increased likelihood of producing reliable estimates with small sample sizes (Song & Lee, Citation2012). More specifically, due to the less-restrictive distributional assumptions, the normality assumption does not need to be fulfilled to perform the analyses within the Bayesian approach (Yuan & MacKinnon, Citation2009). We used the Markov Chain Monte Carlo simulation procedures with a Gibbs sampler and performed 200,000 iterations, and a potential scale reduction factor of around 1 was considered as an indicator of convergence (Kaplan & Depaoli, Citation2012). We evaluated model fit by inspecting the posterior predictive p (PPp) value and its accompanying 95% confidence interval. A PPp value close to .50 indicated good model fit. We estimated a credibility interval (CI) for all parameters within the models. In comparison to the more traditional confidence interval, the credibility interval indicates the probability (e.g., 95%) that the parameter of interest, given the observed data, will lie between the two values. The recommendations from Zyphur and Oswald (Citation2015) were followed, meaning that we rejected the null hypothesis if the 95% CI did not include zero.

Qualitative data generation and analysis

Unmoderated focus groups were preferred to generate qualitative data from the experiences of the coaches who participated in the intervention. Unlike the structured focus group interview, where the intention is to gain insight into a selected topic by having the interviewer (e.g., the researcher) act as a moderator and a guide for the conversation, an unmoderated focus group occurs without the researcher being physically present (Canipe, Citation2020). This form of data generation originates from marketing research and is consistent with the qualitative user-centered design tradition (Yeager et al., Citation2016). Further, using a more unstructured approach to the interview is highlighted as purposeful in field studies where the aim is to reduce the researcher’s influence (Fontana & Prokos, Citation2007).

The unmoderated focus groups were conducted by having all coaches participate in a guided group discussion at the last in-person gathering, facilitated as an evaluation of the CEP. Such an approach was preferred because working in groups is a method the coaches were well acquainted with from the CEP, and was considered to be less intrusive and revealing during the intervention. The discussion involved six randomly distributed groups discussing nine guiding questions related to the intervention (see Supplementary Material B). Some questions were directed at the coaches’ experiences of the intervention and the intervention material (e.g., the length of the videos), while others were more open and concerned with the coaches’ reflections (e.g., the relevance of the topic). The groups worked independently to avoid influence from the coach educators and were led by a selected student who was primarily responsible for the dialogue. The groups had 60 minutes to answer the questions, and the discussions were tape-recorded.

Analysis and rigour

The qualitative data were analyzed by following Braun and Clarke’s (Citation2019; see also Braun et al., Citation2016) six steps of reflexive thematic analysis. First, the tape-recorded group interviews were transcribed verbatim. The first author then organized and read the transcriptions multiple times to gain familiarity with the data. The transcripts were then manually coded, which included generating 293 initial codes embracing both the latent and semantic content of the data. Such a two-fold approach draws on previous research (Braun et al., Citation2016; see also Slater et al., Citation2015) and how deductive and inductive elements may be incorporated when coding the data in relation to the research question. After several rounds of adjustments and refinements in phase three, the coded data were collated into seven preliminary themes (i.e., (1) plan and organization, (2) use of materials, (3) previous experiences, (4) new perspectives, (5) subjective experiences and recognizable, (6) accuracy and relevance, and (7) maturation). The first author was primarily responsible for the coding and initial thematizing and was supported by the second author in stimulating critical insight and alternative interpretations of the data. After the initial thematizing, the theoretical framework of mindset (Dweck, Citation2000, Citation2006) and wise psychological interventions (Walton & Wilson, Citation2018) were applied to move the semantic level of the data to a latent level, and a thematic map was created to illustrate how the themes embrace and describe the coaches’ experiences of the intervention. The fourth author also took part in this process when illuminating and explaining the data with the aid of the existing theoretical framework while being open to the coaches’ experiences to adjust and refine the themes based on empirical data. This process involved several rounds back and forth and led to the amendment of theme titles and collapsing initial themes, resulting in two themes underpinning how the coaches experienced the “targeting of the intervention” as an overarching theme. Two initial themes (1, 2) were collated into a new theme corresponding to the coaches’ “experiences of the intervention delivery.” The remaining initial themes were collated into two intertwined subthemes, “reflective processes” (3, 4) and “sense-making” (5, 6, 7), elaborating on “the targeting exercises as a foundation for self-persuasive processes and commitment to new beliefs,” as the second theme. See Supplementary Material C for example quotes representing the outcome of the six-step reflexive thematic analysis process.

Regarding quality, a relativist approach guided the process of judging the validity and trustworthiness. Unlike a criteriological approach, where predetermined universal criteria are the basis for evaluating quality, this involves an approach where selected criteria are contextually situated and flexible (Burke, Citation2017). The following criteria, in particular, are highlighted considering the aim of the study and methodological approach. First, the substantive contribution of the study is captured in the introduction, involving both the application of wise psychological interventions to enhance the effect of a CEP and how increasing coaches’ growth talent mindsets may substantiate coaches’ and athletes’ development. Second, internal coherence has been maintained by describing how the different parts of the study relate to the research questions and by being clear and transparent in our philosophical assumptions, methodological choices, data collection and analysis, and our interpretations as a basis for the conclusion. Coherence was also addressed externally by discussing the findings in light of previous research. Thirdly, the credibility of the study warrants evaluations through the lens of the researchers’ comprehensive theoretical and practical expertise. Moreover, external experts were engaged to optimize the execution of the study. Using diverse data sources also illuminates various facets pertinent to the research purpose (triangulation). Notably, the primary and secondary authors were integrally involved throughout the research process, enhancing credibility through frequent discussions and critical reflections. This extensive involvement inherently raises questions regarding the fourth criterion, transparency, as continuous interactions between the authors allowed for iterative challenges to one another’s interpretations. However, such a dynamic, while enriching, introduces potential biases, particularly given the researchers’ theoretical engagements. To mitigate such biases, the fourth author, serving as a “critical friend,” was pivotal in interpreting qualitative data. Furthermore, the collective input of the research team was considered necessary in fostering a critical interpretation of the generated data. Regarding our interpretation of the qualitative data, we believe that peer researchers might arrive at analogous findings. However, and more importantly, our primary aspiration is to shed light on areas relevant to understanding strengths and limitations to improve the GrowTMindS Intervention further. This has been attempted to be reflected in the example quotes for the different themes, where we want to illustrate various aspects of the participants’ experience from participation that we consider necessary for further development.

Results

Quantitative data

The descriptive statistics showed that the participating coaches reported an average C-TM score of 4.73 (SD = 0.79) and an A-TM score of 4.28 (SD = 1.15) prior to the intervention. Regarding coaches’ social desirability, the coaches recorded an average score of 3.10 (SD = 0.36) at T1, 3.16 (SD = 0.41) at T2, and 3.46 (SD = 0.36) at T3.

The model for the C-TM showed good fit to the data (PPp = .46, 95% Confidence Interval = [-8.88, 10.50]). There was, however, no credible development in C-TM over time (Δ = 0.08, 95% CI = [−0.05, 0.20]). For the A-TM, the model also showed good fit to the data (PPp = .46, 95% Confidence Interval = [−8.78, 10.59]). There was, on the within-person level, a credible positive development in A-TM over time (Δ = 0.15, 95% CI = [0.01, 0.31]).

Qualitative data

When reporting the qualitative data, we follow the two themes developed through analysis and how the coaches experienced the “targeting of the intervention” as an overarching theme. This begins with the coaches’ “experiences of the intervention delivery.” Consistent with research question one, this part reports the coaches’ stated meanings and ideas from their participation. Next, by drawing on the stated experiences in theme one and the literature that substantiates the design and developmental process, theme two elaborates on the coaches’ more subjective experiences of the intervention and the exercises developed to target their existing talent mindsets. By investigating the coaches’ experiences, this part corresponds to research question two, elaborating “the targeting exercises as a foundation for self-persuasive processes and commitment to new beliefs.” Perhaps more importantly, however, the insight provided by the coaches helped us to understand and discuss what may contribute to undermining the desired self-persuasive processes.

Theme one: experiences of the intervention delivery

When discussing the intervention, the coaches highlighted the good plan of the implementation and the variety in pedagogy (e.g., the mix of traditional teaching and the use of videos) as being positive overall. Concerning the intervention materials, the animated videos were described as especially illustrative and supportive in their learning processes. As one coach pointed out, “It was so easily drawn that you could link it to your own—make your own picture of it.” The individual ownership was further reinforced and connected to their conceptual understanding and learning by having access to the materials followed up with the intervention. The latter was also considered necessary and proper when holding the parental meetings (Assignment A), as exemplified by one coach: “I saw them quite a few times afterward when making the presentation. Then I saw them again and again. And they were very good and descriptive.… For me, it was very positive with the animations and the movies.”

Whereas the animation was highlighted as positive regarding their conceptual understanding and learning, the videos of the national team coaches were described as meaningful in transferring the content into their coaching practice. In the dialogue, the positive impression of the videos was exemplified by one coach, stating, “The first thing that strikes me is that I liked the videos,” while another emphasizes the practical relevance of growth-promoting coaching as follows, “I enjoyed watching the videos of the coaches. They made sense. In them, you could see its application in practice. Yes, you get it from reality, not just from the book, from people who have used it and are using it and are succeeding with it.” Even though the effectiveness of such videos may be questioned (e.g., Hendrick, Citation2019), the coaches’ experiences in this study illustrate that purposeful use can be valuable. The written material was also emphasized as useful because it complemented the videos and for reading about the presented theory, and the six attachments were considered especially helpful when exploring the different strategies of being a growth-promoting coach. As one coach points out, “The six appendices were excellent. I use them a lot, actually.”

Not all coaches experienced the plan as exclusively positive. Some coaches pointed out that the concept was unfamiliar and that conceptual uncertainty made it more difficult for them to understand and actively participate in group discussions. This was further reinforced by interpersonal uncertainty, as most coaches did not know each other prior to the CEP. One coach experienced this, saying, “Everyone was unfamiliar, and it was a little scary too, just chatting. Maybe they could have given us a little more preparation and division into group rooms to discuss in smaller groups.” Furthermore, although the intervention plan was highlighted positively, some coaches thought that the timing and the structure were difficult, considering their background and entrance to the CEP. For example, one coach who had not been a student for several years experienced the total delivery of intervention material as comprehensive and somewhat complex. Others stated that completion of the CEP, especially the assignments, was problematic due to various reasons (e.g., vacation, newly accomplished parent-coach meeting, or short deadline). Regarding the comprehensiveness of the intervention, some coaches also reported that the intervention materials were long-winded, especially the videos representing the sports-specific group.

Theme two: the targeting exercises as a foundation for self-persuasive processes and commitment to new beliefs

Considering the group discussions, certain areas were essential when interpreting the coaches’ experiences of the intervention and how their perception of the targeting exercises may have influenced the intended effect. The analysis revealed that implementing a wise psychological intervention is not straightforward, as various factors may impact the targeting as a basis for individual processes. In the following, we will elaborate on what seems to have sustained the targeting before highlighting what may have undermined the intervention delivery.

In general, the coaches appeared positive when they, for instance, stated that the content “stands up well, in comparison to other coach educational programs” [e.g., UEFA’s coach education], that the intervention material “was very good because it described scenarios of kids that you recognize from your club,” and that it was “very easy to adopt into their sport,” because “it’s something that everyone has experienced and everyone can relate to.” To our knowledge, such statements suggest how the coaches experienced the delivery as normatively good and contextually relevant, and how they perceived the communicated talent mindset messages as easy to adopt into real coaching situations. Hence, grounded in the work of wise psychological interventions (e.g., Harackiewicz & Priniski, Citation2018; Walton & Wilson, Citation2018), these statements may provide insight into how the delivery targeted the psychological problems of the intervention in a way that appears wise to the participant. More concretely, we believe the coaches’ perceptions showcase how they infer the messages that coach and athlete talent are malleable as relevant and meaningful, that they were sense-making, which possibly leads the individual to commit themselves to the new beliefs via reflective processes. The use of sense-making refers to the aim of the intervention to develop the coaches’ growth talent mindsets, i.e., their meaning of talent as a concept. Since meaning is something the individual attributes to the concept, which is developed and reinforced by the individual (Walton & Wilson, Citation2018), and in this regard, within sports as a context, it seems essential that the introduction of new meanings appears to be sense-making about themselves and the context of the CEP. Succeeding in areas like these are especially important, as CEPs, in general, are experienced as being distanced from the sporting context (Solstad et al., Citation2017), and since failure in targeting may entail participants refuting the delivery and potentially undermining the aim of the intervention (Yeager et al., Citation2016).

By looking more closely at those who seemed to embrace the targeting of the intervention, it appears that some coaches directly found meaning in the communicated talent mindset messages, as they experienced the delivery as an “eye-opener” that immediately made them more aware of themselves, their role as coaches, and their training planning. For example, one coach said, “I learned so much from it [the intervention] that my structure for planning training sessions became completely different after the first in-person gathering. It was extremely helpful for me.” Other coaches who also became more aware pointed out that, in a way, the talent mindset messages got better with time, stating that “it makes sense the longer it lasts.” Considering Walton and Wilson (Citation2018), therefore, the intervention may have altered the lens through which they interpret themselves and their athletes, and by showing adaptive strategies, they may have maintained or developed a growth C-TM and A-TM by participating in the intervention. In this regard, several coaches expressed that, by being aware of how to interpret themselves and social situations, such as the culture in their sports organization, they also became much more confident as coaches when meeting challenges, and as one coach stated:

In that sense, it was a very good awareness, and it strengthened one’s position.… But this is precisely what you are challenged on by both your athletes and the parent group, and to that extent, also other coaches you come into contact with. So, having that foundation behind it, I see it as very useful.

Also, it is so concrete. It is very straightforward to adapt it to what we are doing. Many school and sports theories appear to be both general and extensive. And it becomes like, “How am I supposed to get started with it, and how does it work?” But this was super easy to adopt into the sport of the individual.

As previously noted, not all coaches perceived the communicated talent mindset messages as sense-making and were thus not targeted by the delivery as intended. For example, one coach stated, “I thought it was interesting with a growth mindset. However, adopting it into the training sessions? Now [in the daily work as coach] I coach adult ladies older than me, but I did not think it was very easy.” Just as the intervention is tailored to coaches responsible for athletes from 13 to 19 years of age, this may be an example of how coaches with responsibility for athletes outside of this target group (e.g., senior or elite-level athletes) found it challenging to adapt the growth-promoting framework to their coaching practice. Hence, this example may confirm the importance of tailoring the intervention to a specific group and problem (Dweck & Yeager, Citation2019; Walton & Wilson, Citation2018), and it may illustrate the limitation of interventions if they fail to target the participants’ mindsets in a sense-making way—it is like delivering “nothing at all” (Yeager & Walton, Citation2011).

Another issue that may have influenced the targeting is how the coaches performed their daily work as coaches in different sports clubs alongside the intervention. We find it particularly interesting that the sports context was heavily discussed among the coaches, especially how difficult it was to come up with new ideas in contrast to “the old school,” and how the individuals in the club reinforced the existing culture. For example, one coach stated:

I think that the culture of the [name of the national governing body] has been characterized by the fact that there is inbreeding among people. It is they who have been athletes who return and become team leaders and coaches, and members of the club boards. There is not much new fresh blood. And then it becomes like, “Yes, but that’s how we have always done it!”

It is so easy to fall back on old patterns. I also think, as you say, that you will never finish this [improving a growth talent mindset]. … I think it’s important to learn to recognize the different situations in which it occurs. If it is not a fixed mindset, it may be a task you have done many times that you just do in the same way. It has become automatized. “Yes, I do this like that! That’s the way I’ve always done it.” It may be right to solve it that way, but there is always an opportunity to do it in another way, a little better, or differently, to challenge yourself!

The final issue relates to how the participants’ intersectionality of demographic categories may have caused problems concerning how precisely the intervention targeted coaches’ talent mindsets (Harackiewicz & Priniski, Citation2018), as some coaches had already formed their understanding of the term “mindset” prior to the intervention. In this study, the Norwegian term “mentalitet” was applied, and as one of the coaches pointed out, “In my opinion, or perhaps in my language, [mentalitet] is the main feature of a group of people or as a country, or region.” Such an understanding corresponds to how the term has historically been used to describe a group of people or, in many situations, is linked to other words with another meaning.

General discussion, limitations, and future directions

The aim of the current study was to design and develop the GrowTMindS Intervention and, for the first time, investigate how sports coaches’ C-TM and A-TM could be affected through participation. Furthermore, by drawing on a qualitative user-centered design (Yeager et al., Citation2016), we sought to gain an understanding of the coaches’ perceptions of participation and learn from their experiences to further improve the intervention (Creswell & Clark, Citation2017).

Consistent with previous growth-mindset interventions (see Dweck & Yeager, Citation2019), this study shows that a coach’s A-TM score can be induced toward a growth talent mindset. Although personal mindsets are assumed to be relatively stable dispositions (Dweck, Citation2000), these findings indicate that coaches’ beliefs in the malleability of athletic talent can change throughout participation in a growth talent mindset intervention and, thus, a CEP. This study also confirms the domain specificity of a personal mindset (Yeager & Dweck, Citation2012), as a coach’s belief in the malleability of their talent as a coach seems to be more challenging to target. Note that the coaches reported a high baseline growth C-TM score close to the maximum, which may have prevented further increases at scale due to the ceiling effect (Shadish et al., Citation2002). In this regard, their baseline C-TM was relatively higher than their A-TM, which was comparable to the coaches’ A-TM score in the study of Nilsen et al. (Citation2023), and interestingly, their existing and strong belief in their malleability as a coach may have helped them to embrace a stronger growth mindset of athletic talent (Chase, Citation2010).

Regarding the interpretation of the quantitative data, the coaches’ social desirability index was computed due to the uncertainty of socially desirable answers when self-reporting talent mindsets (Nilsen et al., Citation2023). Despite an index leaning toward social desirability, it is considered a strength that the lack of systematic correlation with the C-TM and A-TM scores indicates that a social desirability bias did not limit their answers. On the contrary, the small sample size and the lack of a control group pose a threat to the validity of the study (Shadish et al., Citation2002). A small sample also prevents the ability to control for effects between different groups, which is interesting given that previous research has shown differences in coaches’ mindsets depending on sports coaches, age, or country of birth (Nilsen et al., Citation2023). Another potential limitation is the moderate Cronbach’s alpha values for C-TM on two of the data collection points. The small sample in combination with the few items for the mindset questionnaires might, however, underestimate the relationships between the included items (e.g., Cortina, Citation1993; Yurdugül, Citation2008). When looking at the average inter-item correlations they are .47 and .48 for the two data collection points where the alpha is below .70. This indicates adequate correlations between the items (e.g., Briggs & Cheek, Citation1986). It should also be mentioned that there is a small proportion of female coaches in this study. Even though no differences in coaches’ talent mindset have been found based on gender, the low proportion of female coaches means that the representation is male-dominated. Lastly, the fact that the coaches have sought out coaching education and consented to participate might entail a selection bias (Shadish et al., Citation2002). In this context, however, it is worth noting that the coaches’ average A-TM score is comparable to the study by Nilsen et al. (Citation2023) and aligns with the argument that a growth mindset is a defining characteristic of coaches as a group.

With regard to coaches’ reflections and perceptions of their participation, we believe that the qualitative data complement the quantitative findings. On the one hand, the participating coaches confirmed that the use of context-based videos, such as the animations, potentially enhanced their learning, and that the videos of the national team coaches connected the talent mindset messages to their practice as coaches, supported by the written material. We also believe that the delivery of the intervention targeted most coaches as they perceived the communicated talent mindset messages as trustworthy and sense-making, thereby substantiating their talent mindsets through self-reflection and self-persuasive processes (Aronson, Citation1999; Walton & Wilson, Citation2018). On the other hand, the intervention may not successfully target all coaches’ talent mindsets. For various reasons, some coaches were not sufficiently motivated to resolve the tension between the talent mindsets they already had and the growth talent mindset messages being communicated in the intervention (Aronson, Citation1999; Walton & Wilson, Citation2018). Based on the group discussions, it is difficult to know whether individual coaches embraced the communicated talent mindset messages of the intervention and increased their growth talent mindsets, or maintained their fixed mindsets by refuting the content. However, the use of qualitative methods helped us to identify why some coaches seemed to refute the delivery of the intervention, and this can be summarized in the following three points that should be considered for further improvement and tailoring of the intervention:

Improve the content and delivery of the intervention material. Consider the length of the videos and new methods of distributing the content, and thus the impression, over a more extended period. Increase the coaches’ possibility to control their progress in the three-step talent mindsets workshop.

Lower personal and professional barriers. Consider new methods of preparing the coaches for the in-person gatherings, including personal (interpersonal uncertainty and the uncertainty of being a student) and professional matters (conceptual uncertainty). Also, revise the introduction of the concept in order to familiarize the “language” used in the intervention and clarify conditions that may undermine the targeting of the intervention.

Strengthen the connection between the CEP and the coaches’ practice. Consider new methods for how to help the student transform communicated talent mindset messages into coaching practice. Strengthen the coaches’ work with the assignments, especially for how to plan and implement the parent-coach meeting and the training session.

Conclusion

By drawing on this study’s quantitative and qualitative data, the findings are promising regarding the possibility of developing coaches’ growth talent mindsets through their participation in an intervention. Furthermore, by obtaining an understanding of the coaches’ experiences, we learned what worked well and what could be improved according to the plan of delivery. We, therefore, consider this study to represent an essential first step in designing and developing the GrowTMindS Intervention, where the aim is to develop sports coaches’ growth mindsets about their talent as a coach and their athletes’ talent. The next step is to follow up on these findings and refine the intervention (see Part II).

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (411.3 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participants in the administrative group, the sport-specific group, and the coaches at the coach educational program for contributing to the study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Due to the nature of this research, participants of this study did not agree for their data to be shared publicly, so supporting data are not available.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abrahamsen, F. E., Roberts, G. C., Pensgaard, A. M., & Ronglan, L. T. (2008). Perceived ability and social support as mediators of achievement motivation and performance anxiety. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 18(6), 810–821. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0838.2007.00707.x

- Aronson, E. (1999). The power of self-persuasion. American Psychologist, 54(11), 875–884. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0088188

- Aronson, J. M., Fried, C. B., & Good, C. (2002). Reducing the effects of stereotype threat on African American college students by shaping theories of intelligence. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 38(2), 113–125. https://doi.org/10.1006/jesp.2001.1491

- Author (2018b). Growth mindsets in sports – How coaches can promote a growth mindset in their own athletes [Brochure and https://doi.org/supplementary material in Part II].

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

- Braun, V., Clarke, V., & Weate, P. (2016). Using thematic analysis in sport and exercise research. In B. Smith & A. C. Sparkes (Eds.), Routledge handbook of qualitative research in sport and exercise (pp. 191–205). Routledge.

- Briggs, S. R., & Cheek, J. M. (1986). The role of factor analysis in the development and evaluation of personality scales. Journal of Personality, 54(1), 106–148. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1986.tb00391.x

- Burke, S. (2017). Rethinking “validity” and “trustworthiness” in qualitative inquiry: How might we judge quality in qualitative research in sport and exercise sciences? In B. Smith & A. C. Sparkes (Eds.), Routledge handbook of qualitative research in sport and exercise (pp. 330–339). Routledge.

- Chapman, D. W., & Carter, J. F. (1979). Translation procedures for the cross culture use of measurement instruments. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 1(3), 71–76. https://doi.org/10.3102/016237370010030

- Canipe, M. M. (2020). Unmoderated focus groups as a tool for inquiry. The Qualitative Report, 25(9), 3361–3368. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2020.4604

- Chase, M. A. (2010). Should coaches believe in innate ability? The importance of leadership mindset. Quest, 62(3), 296–307. https://doi.org/10.1080/00336297.2010.10483650

- Claro, S., Paunesku, D., & Dweck, C. S. (2016). Growth mindset tempers the effects of poverty on academic achievement. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(31), 8664–8668. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1608207113

- Chroni, S. A., Medgard, M., Nilsen, D. A., Sigurjonsson, T., & Solbakken, T. (2018). Profiling the Coaches of Norway: A national survey report of sports coaches & coaching. Inland Norway University of Applied Sciences. https://brage.inn.no/inn-xmlui/handle/11250/2569671

- Cortina, J. M. (1993). What is coefficient alpha? An examination of theory and applications. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78(1), 98–104. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.78.1.98

- Creswell, J. W., & Clark, V. L. P. (2017). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (3rd ed.). Sage.

- Cronbach, L. J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika, 16(3), 297–334. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02310555

- Cushion, C. J., Armour, K. M., & Jones, R. L. (2003). Coach education and continuing professional development: Experience and learning to coach. Quest, 55(3), 215–230. https://doi.org/10.1080/00336297.2003.10491800

- Czajkowski, S. M., & Hunter, C. M. (2021). From ideas to interventions: A review and comparison of frameworks used in early phase behavioral translation research. Health Psychology: Official Journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association, 40(12), 829–844. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0001095

- Dweck, C. S. (1986). Motivational processes affecting learning. American Psychologist, 41(10), 1040–1048. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.41.10.1040

- Dweck, C. S. (2000). Self-theories: Their role in motivation, personality, and development. Psychology Press. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315783048

- Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success. Random House.

- Dweck, C. S. (2009). Mindsets: Developing talent through a growth mindset. Olympic Coach, 21(1), 4–7. https://www.teamusa.org/About-the-USOPC/Coaching-Education/Coach-E-Magazine

- Dweck, C. S., Chiu, C-y., & Hong, Y-y. (1995). Implicit theories and their role in judgments and reactions: A word from two perspectives. Psychological Inquiry, 6(4), 267–285. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327965pli0604_1

- Dweck, C. S., & Yeager, D. S. (2019). Mindsets: A view from two eras. Perspectives on Psychological Science: a Journal of the Association for Psychological Science, 14(3), 481–496. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691618804166

- Field, A. (2018). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics (5th ed.). Sage.

- Fontana, A., & Prokos, A. H. (2007). The interview: From formal to postmodern. Taylor & Francis Group.

- George, D., & Mallery, P. (2020). IBM SPSS statistics 26 step by step: A simple guide and reference (16th ed.). Routledge.

- Gunderson, E. A., Gripshover, S. J., Romero, C., Dweck, C. S., Goldin‐Meadow, S., & Levine, S. C. (2013). Parent praise to 1‐ to 3‐year‐olds predicts children’s motivational frameworks 5 years later. Child Development, 84(5), 1526–1541. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12064

- Harackiewicz, J. M., & Priniski, S. J. (2018). Improving student outcomes in higher education: The science of targeted intervention. Annual Review of Psychology, 69(1), 409–435. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-122216-011725

- Hendrick, C. (2019). The growth mindset problem. Aeon. https://aeon.co/essays/schools-love-the-idea-of-a-growth-mindset-but-does-it-work

- Heslin, P. A., Latham, G. P., & VandeWalle, D. (2005). The effect of implicit person theory on performance appraisals. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(5), 842–856. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.5.842

- Heslin, P. A., Vandewalle, D., & Latham, G. P. (2006). Keen to help? Managers’ implicit person theories and their subsequent employee coaching. Personnel Psychology, 59(4), 871–902. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2006.00057.x

- Horn, T. (2008). Coaching effectiveness in the sport domain. In T. Horn (Ed.), Advances in sport psychology (3rd ed., pp. 239–267). Human Kinetics.

- Kaplan, D., & Depaoli, S. (2012). Bayesian structural equation modeling. In R. H. Hoyle (Ed.), Handbook of structural equation modeling (pp. 650–673). The Guilford Press.

- Langan, E., Blake, C., & Lonsdale, C. (2013). Systematic review of the effectiveness of interpersonal coach education interventions on athlete outcomes. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 14(1), 37–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2012.06.007

- LaPrade, R. F., Agel, J., Baker, J., Brenner, J. S., Cordasco, F. A., Côté, J., Engebretsen, L., Feeley, B. T., Gould, D., Hainline, B., Hewett, T., Jayanthi, N., Kocher, M. S., Myer, G. D., Nissen, C. W., Philippon, M. J., & Provencher, M. T. (2016). AOSSM early sport specialization consensus statement. Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine, 4(4), 2325967116644241. https://doi.org/10.1177/2325967116644241

- Molden, D. C., & Dweck, C. S. (2006). Finding “meaning” in psychology: A lay theories approach to self-regulation, social perception, and social development. American Psychologist, 61(3), 192–203. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.61.3.192

- Muthen, L. K., & Muthen, B. O. (1998–2022). Mplus 8.4. Base program and combination. Add-off.

- Murphy, M. C., & Reeves, S. L. (2019). Personal and organizational mindsets at work. Research in Organizational Behavior, 39, 100121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.riob.2020.100121

- Nilsen, D. A. (2018). Talent mindsets in sports – experiences from coaches’ and athletes’ perspectives [Unpublished digitized material]. Inland Norway University of Applied Sciences.

- Nilsen, D. A., Sigurjonsson, T., Pensgaard, A. M., & Chroni, S. A. (2023). Sports coaches’ athlete talent mindset and views regarding talent identification in Norway. International Sport Coaching Journal, 10(2), 141–153. https://doi.org/10.1123/iscj.2022-0010

- Owen, C. (2007). Design thinking: Notes on its nature and use. Design Research Quarterly, 2(1), 16–27. https://dl.designresearchsociety.org/design-research-quarterly/2

- Razzouk, R., & Shute, V. (2012). What is design thinking and why is it important? Review of Educational Research, 82(3), 330–348. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654312457429

- Ries, E. (2011). The lean startup: How today’s entrepreneurs use continuous innovation to create radically successful businesses. Random House.

- Rudmin, F. W. (1999). Norwegian short‐form of the Marlowe‐Crowne social desirability scale. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 40(3), 229–233. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9450.00121

- Shadish, W., Cook, T. D., & Campbell, D. T. (2002). Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for generalized causal inference. Wadsworth Publishing.

- Slater, M. J., Barker, J. B., Coffee, P., & Jones, M. V. (2015). Leading for gold: Social identity leadership processes at the London 2012 Olympic Games. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 7(2), 192–209. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2014.936030

- Slater, M. J., Spray, C. M., & Smith, B. M. (2012). “You’re only as good as your weakest link”: Implicit theories of golf ability. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 13(3), 280–290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2011.11.010

- Solstad, B. E., Larsen, T. M. B., Holsen, I., Ivarsson, A., Ronglan, L. T., & Ommundsen, Y. (2017). Pre- to post-season differences in empowering and disempowering behaviours among youth football coaches: A sequential mixed-methods study. Sports Coaching Review, 7(2), 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/21640629.2017.1361166

- Song, X.-Y., & Lee, S.-Y. (2012). A tutorial on the Bayesian approach for analyzing structural equation models. Journal of Mathematical Psychology, 56(3), 135–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmp.2012.02.001

- Stenling, A., Ivarsson, A., Johnson, U., & Lindwall, M. (2015). Bayesian structural equation modeling in sport and exercise psychology. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 37(4), 410–420. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.2014-0330

- Stodter, A., & Cushion, C. J. (2014). Coaches’ learning and education: A case study of cultures in conflict. Sports Coaching Review, 3(1), 63–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/21640629.2014.958306

- Sun, K. L. (2019). The mindset disconnect in mathematics teaching: A qualitative analysis of classroom instruction. The Journal of Mathematical Behavior, 56(, 100706. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmathb.2019.04.005

- Vella, S. A., Braithewaite, R. E., Gardner, L. A., & Spray, C. M. (2016). A systematic review and meta-analysis of implicit theory research in sport, physical activity, and physical education. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 9(1), 191–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2016.1160418

- Vella, S. A., Cliff, D. P., Okely, A. D., Weintraub, D. L., & Robinson, T. N. (2014). Instructional strategies to promote incremental beliefs in youth sport. Quest, 66(4), 357–370. https://doi.org/10.1080/00336297.2014.950757

- Walton, G. M. (2014). The new science of wise psychological interventions. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 23(1), 73–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721413512856

- Walton, G. M., & Wilson, T. D. (2018). Wise interventions: Psychological remedies for social and personal problems. Psychological Review, 125(5), 617–655. https://doi.org/10.1037/rev0000115

- Wilson, T. D. (2002). Strangers to ourselves: Discovering the adaptive unconscious. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

- Yeager, D. S., Dahl, R. E., & Dweck, C. S. (2018). Why interventions to influence adolescent behavior often fail but could succeed. Perspectives on Psychological Science: a Journal of the Association for Psychological Science, 13(1), 101–122. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691617722620

- Yeager, D. S., & Dweck, C. S. (2012). Mindsets that promote resilience: When students believe that personal characteristics can be developed. Educational Psychologist, 47(4), 302–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2012.722805

- Yeager, D. S., Romero, C., Paunesku, D., Hulleman, C. S., Schneider, B., Hinojosa, C., Lee, H. Y., O'Brien, J., Flint, K., Roberts, A., Trott, J., Greene, D., Walton, G. M., & Dweck, C. S. (2016). Using design thinking to improve psychological interventions: The case of the growth mindset during the transition to high school. Journal of Educational Psychology, 108(3), 374–391. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000098

- Yeager, D. S., & Walton, G. M. (2011). Social-psychological interventions in education: They’re not magic. Review of Educational Research, 81(2), 267–301. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654311405999

- Yuan, Y., & MacKinnon, D. P. (2009). Bayesian mediation analysis. Psychological Methods, 14(4), 301–322. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016972

- Yurdugül, H. (2008). Minimum sample size for Cronbach’s coefficient alpha: A Monte-Carlo study. Hacettepe Üniversitesi Eğitim Fakültesi Dergisi, 35(35), 397–405.

- Zyphur, M. J., & Oswald, F. L. (2015). Bayesian estimation and inference: A user’s guide. Journal of Management, 41(2), 390–420. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206313501200