ABSTRACT

Since the 1980s, extensive archeological studies have provided us with knowledge about the multifaceted relations between Nuragic Sardinia and Bronze Age Cyprus. During the winter of 2019, Nuragic tableware of Sardinian origin was discovered at the harbor site of Hala Sultan Tekke, on the south-eastern coast of Cyprus, providing the opportunity to return to the question of the reasons behind this presence. The aim of this paper is to reflect on the characteristics and role of Sardinian maritime “enterprises” in the long-distance metal trade in the Mediterranean and beyond, including continental Europe. An array of new provenance studies demonstrates the complexity of the Bronze Age metal trade and, taking a maritime perspective, provides the opportunity to reveal how strategically positioned actors such as Nuragic Sardinia managed to dominate sea-borne routes, and gained a prominent and independent international position.

Introduction

During winter 2019, thanks to an interdisciplinary collaboration, five more or less complete bowls of Sardinian origin were detected among recently excavated material from the necropolis of Hala Sultan Tekke, Cyprus.[Citation1] The bowls have the typical shape and the technological and petrographic characteristics of Nuragic so-called burnished gray ware (). They represent the first examples of this kind of pottery ever reported from Cyprus.[Citation1,Citation2] Other Nuragic ceramics are known from Sicily, Crete, and Cyprus (see below), but, so far, fine drinking ware had not been found outside the island.

Figure 1. Nuragic bowl from Hala Sultan Tekke (courtesy of Peter M. Fischer, director of the Swedish expedition at Hala Sultan Tekke, Cyprus).

Over the years, the investigations at the site of Hala Sultan Tekke have provided many interesting features and finds.[Citation3–Citation22] Hala was an urban settlement of considerable size and wealth, with a strategic position close to the sea, and a natural harbor, which had roughly the contour of today’s local salt lake. The excavations at the site revealed, among other things, striking evidence of varied craft production,[Citation18,Citation23–Citation26] including metalworking of consistent scale.[Citation13,Citation14,Citation16,Citation17,Citation27–Citation29] In addition to the settlement, an extra-urban necropolis has also been detected.[Citation9,Citation14–Citation16,Citation30]

The discovery of Nuragic tableware from Hala Sultan Tekke arrives as a welcome addition to a long-lived debate on the character of the specific connections between Sardinia and Cyprus. Despite diverging positions,[Citation31] the new finds provide strong evidence for the idea of a distinctive and intensive relationship between Cyprus and Sardinia. It also reinforces earlier suggestions that considered Nuragic Sardinian communities to have been seafaring participants in the long distance metal trade in the Mediterranean.[Citation32–Citation37] Therefore, the time is ripe to reassess the role of Sardinian maritime “enterprises” in the context of the Bronze Age international metal trade. In doing so, the article will discuss not only old and new archeological evidence for long distance exchange, but also envisions the existence of apparently stable and well-defined maritime routes connecting Sardinia and Cyprus, i.e. the Western and Eastern Mediterranean.

The Nuragic Recent Bronze Age

In the Italian archeological and chronological framework system,[Citation38] the later part of the Bronze Age (LBA) is split into the Recent Bronze Age (RBA), sometimes divided into two phases, and the Final Bronze Age (FBA), divided into three phases (). In English scientific works the term Late Bronze Age is often used to define what we here call the Recent Bronze Age. We believe, and hope to make a point for future studies, that the translation of the Italian first part of the later Bronze Age (età del bronzo recente) into Late Bronze Age leaves room for misunderstanding. We therefore favor the otherwise also widely accepted term Recent Bronze Age (RBA).

Table 1. Chronological chart.

In the Aegean,[Citation41] the succession of the Late Helladic (LH) ceramic phases of LH I, LH II, LH IIIA, LH IIIB, LH IIIC encompasses, as a whole, the Italian Middle Bronze Age (MBA) and the first phase of the FBA. Only LH IIIB can be considered parallel to the Italian RBA (the so-called “Sub-Appennine” period). In Cyprus, the Italian RBA would roughly correspond to the Late Cypriot (LC) IIB and IIC.[Citation40,Citation42,Citation43]

It is interesting to note that in Sardinia the phenomena characteristic of the RBA seem to begin earlier than in mainland Italy (),[Citation39,Citation40] and to correspond to the Aegean LH IIIA2, LH IIIB, likely including part of LH IIIC, and to LC IIB, LC IIC and part of LC IIIA in the Cypriot cultural sequence. On the island, ceramics imported from the Aegean, found in stratified levels and in association with local pottery, provided important chronological references, as in the case of the LH IIIA2 alabastron from the foundation layers of the nuraghe Arrubiu-Orroli.[Citation44–Citation46] Additional chronological references are provided by the associations of Nuragic pottery found outside Sardinia at the harbor site of Kommos, on the southern coast of Crete, in the LH IIIB levels, at Pyla-Kokkinokremos, and now at Hala Sultan Tekke in LC IIC strata. The Nuragic burnished gray ware is widely documented in RBA sites of southern Sardinia, including the nuraghe Antigori (Sarroch district), where it is associated with LH IIIB Aegean pottery.[Citation47,Citation48]

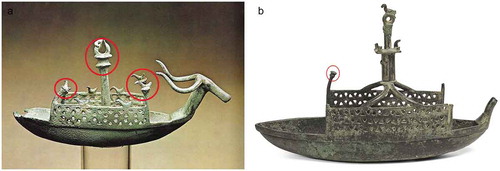

In the RBA various types of nuraghi coexist (e.g. single-tower nuraghi together with the complex-plan nuraghi, like the nuraghe Arrubiu) with various kinds of megalithic tombs and temples characterized by ashlar masonry, both isolated or associated with other structures in the so-called “federal” sanctuaries.[Citation49,Citation50] The evidence suggests that the island might have been arranged in territorial systems, organized around strategically placed nuraghi of all kinds, villages, and tombs, and aiming at the strict control and common exploitation of vital resources such as harbors and landing places, rivers, marshes, fords, routes and paths, ores, woodlands, and agricultural lands. People living in these presumably interlinked territorial systems were likely engaged in maritime “enterprises” across the Mediterranean.[Citation37,Citation51–Citation54] One example of possible evidence of this maritime focus can be seen in the relatively frequent representation of Nuragic towers (-b) on bronze miniature boats (around 22 examples on c. 150 boats), tentatively interpreted as symbols of control over sea-routes.[Citation55] Indeed the nuraghi are not only the impressive towers still visible all over the island, but also a powerful symbol reproduced in various ways and materials throughout the local Bronze Age.[Citation56] Nuragic models are interpreted as tokens of a cult of the ancestors (the latter embodied in the very same representations of the nuraghe), which developed when Nuragic towers were no longer built, but the existing ones (about 8000 or more) were still in use and certainly represented markers of identity for the local communities.[Citation57]

Figure 2. Nuragic miniature bronze boats with Nuragic towers.

Materials and methods

Metal trade and oxhide ingots

An enormous body of scholarly literature on Mediterranean LBA metal trade exists, not least on the oxhide ingot phenomenon, which is not possible to summarize in this paper. In more recent years attention has been drawn to the fact that evidence of familiarity with oxhide ingots is not limited to the Mediterranean basin, but stretches to continental Europe and Scandinavia,[Citation58–Citation60] therefore well beyond the long known finds from the Oberwilflingen hoard, in Germany.[Citation61] Scholarly literature on metal trade in continental Europe matches in size its counterpart on the Mediterranean. It is obvious that in both regions the demand for metals, and in particular for copper and tin, must have been very high during the Bronze Age in general, and, as for the scope of this paper, in the central centuries of the second half of the 2nd millennium BC. The significant results of recent lead isotope analyses from the Scandinavian Bronze Age bronze and copper items[Citation62–Citation64] provide an unexpected, and yet relevant, idea of the variation in the channeling of metal supplies in Europe throughout the Bronze Age. It is largely thanks to these studies that it is becoming clear how the Mediterranean area and continental Europe must have been connected in a network to facilitate this quest for metals.[Citation65–Citation68] Understanding modes and characteristics in which these international systems of exchange and trade of metals operated represents an exciting challenge for many future studies on the topic.

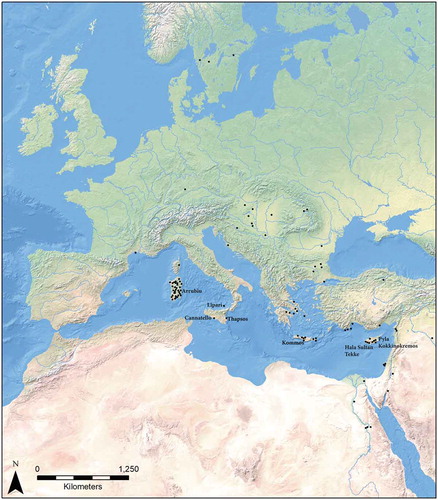

Regarding copper, one can say that it clearly circulated in the form of ingots as much as in that of cast objects or tools, and that it clearly came from a variety of sources.[Citation33–Citation35,Citation43,Citation58,Citation62–Citation64,Citation69–Citation75] The most remarkable class of ingots – in terms of shape, weight, purity, and the technological and material efforts required to produced them – is probably that of oxhide ingots (–). Their distribution () and chronology show a complex circulation involving multiple lands, cultures, and necessarily political and economic systems. Yet, as discussed, the circulation of copper must have been complex and oxhide ingots should be seen as just one, albeit impressive, expression of it. From an economic and pragmatic point of view, oxhide ingots were undoubtedly suitable for the transportation of large quantities of copper. It has been argued that their peculiar shape was probably familiar to a variety of receivers/markets.[Citation59 with previous bibliography] A series of indications suggests that they most probably embodied a message either connected to their weight, content, and/or purity, and perhaps also to the provenance of their copper, and/or to the skilled labor necessary for their production.[Citation71] Such a message was not only recognized over a wide landscape, but also across several centuries. As has been proposed, they seem very much to embody the characteristics of a brand commodity.[Citation60,Citation76] So far, most of the analyzed oxhide ingots datable between the fourteenth and the early eleventh century BC seem to be made of Cypriot copper, and in particular by using the ores from the Apliki deposits.[Citation70,Citation77,Citation78] The many oxhide-related artifacts from Cyprus confirm the prominent socio-cultural, political and economic role of these ingots for local communities all over the island.[Citation79,Citation80] There is still no consensus as to the copper source used for some of the earliest oxhide ingots (recovered in Crete),[Citation74] but after the fourteenth century BC, and with the remarkable exception of some of the fragments from the Ballao-Funtana Coberta hoard[Citation81] and the Pattada-Sedda Ottinnera hoard[Citation69] in Sardinia (see below), oxhide ingots seem to become a sort of Cypriot branded good over nearly three centuries.[Citation59,Citation82–Citation84] Their distribution, chronology, miniature manufacture, figurative representations on different materials and means, presence in ritual/funerary and cultic contexts or in association with metallurgical activities creates a multifaceted picture.[Citation33,Citation58–Citation60,Citation80,Citation85–Citation89] The geographical and chronological spread of such evidence suggests that the distribution pattern of oxhide ingots was with all probability even larger than what the archeological record currently tells us. The shipwrecks along the southern coasts of today’s Turkey and Israel provide an impressive idea of the large amount of metal, in general and, of oxhide ingots, in particular, that must have been in circulation in the LBA.[Citation86,Citation90–Citation94]

Figure 3. Fragments of oxhide ingots and of votive swords from Giva ’e Molas, Villamar, Cagliari province, Archaeological Museum Villa Leni of Villacidro (courtesy of Ilisso Edizioni, Nuoro, Italy).

Figure 4. The oxhide ingot from Ozieri, Sassari province, S. Antioco Bisarcio, Ozieri Civic Archaeological Museum (courtesy of Ilisso Edizioni, Nuoro, Italy).

Figure 5. Distribution map of the oxhide ingots and oxhide ingot-like material evidence and of the main sites mentioned in the text (graphics: Serena Sabatini and Rich Potter).

Nuragic Sardinia and oxhide ingots: an updated summary

A comprehensive discussion on the copper trade in the central Mediterranean, particularly detailed in regard to Sardinia, dates to 2009.[Citation35] In Sardinia, four complete oxhide ingots are known: one from S. Antioco of Bisarcio-Ozieri and three from Serra Ilixi-Nuragus (Nuoro). All the rest are hundreds of fragments, generally found in hoards hidden in nuraghi, Nuragic villages, temples, and sanctuaries, but never in tombs.[Citation84] The number of archeological contexts with oxhide ingots from Sardinia is steadily increasing: 31 sites were published in 2009,[Citation83] 36 in 2016,[Citation33,Citation59] while in 2019 the number of sites reached 40.[Citation33] An equally numerous and widespread evidence for this class of material does not exist anywhere else in the Mediterranean or in Europe ().

Table 2. List of the known oxhide ingots.

Oxhide ingots circulated in Sardinia earlier than generally believed a decade ago.[Citation83,Citation110] The miniature reproduction in clay (6.5 x 3–3.5 × 0.8 cm) of a perfectly recognizable oxhide ingot, identical in shape to the ingot Serra Ilixi 3, was recovered from one of the towers of the outer wall of the nuraghe Coi Casu, S. Anna Arresi,[Citation89] and came to light during systematic excavations. The ingot was used as a plastic decoration on a ceramic fragment of the metope pottery style, datable to the final third phase of the MBA (late fourteenth century BC). It is evident that in order to have been so carefully reproduced the exact appearance of an oxhide ingot had to have been well-known, and must have had particular importance at the time in which this impasto vessel was created. Therefore, oxhide ingots circulated in the West and as far as Sardinia for a considerable time.[Citation33,Citation111]

The earliest closed context with oxhide ingots is the Albucciu-Arzachena hoard. It was found during modern archeological excavations and consists of fragments of ingots, votive swords, bronze sheets, scrap metal, and a small chisel, deposited in a jar covered by a bowl. The hoard is dated to the RBA and has parallels in the LH IIIB by the shape of the pottery container, similar to that discovered in levels of the same age (around thirteenth century BC) at the harbor site of Kommos, Crete.[Citation33,Citation69,Citation83]

The Funtana Coberta-Ballao hoard is also securely dated to the RBA. It was recovered in a room adjacent to the external wall of a characteristic Nuragic “Well Temple”, scientifically excavated and extensively published in recent times.[Citation112] The hoard includes 31 fragments of oxhide ingots and votive swords as well as scrap metal from bronze working, both sheets and castings, totaling 20.571 kg. The metal had been placed in a double-handled jar of the same type as the ones found at Kommos (LH IIIB) and in Sardinia, and dated to RBA.[Citation81] Finally, the oxhide ingot fragment (45.1 g) from the ground floor of the central Tower A of the Serucci-Gonnesa nuraghe should also be included among the early finds. Thanks to the associated pottery, this fragment can be dated between the end of the RBA and the beginning of the FBA.[Citation32,Citation33]

Provenance studies, metal trade, and Sardinia

Sardinian metallurgy and other copper sources outside Sardinia

Almost all oxhide ingots found in Sardinia and submitted to lead isotope analyses up to 2009 (about one-fifth of the total) showed the isotopic pattern of Cypriot ores, particularly of the Apliki mine in the Solea district of the Troodos Mountains.[Citation70]

Because of its undisturbed stratigraphic situation, a full-scale project of geological, metallurgical and lead isotope analyses was dedicated to the Funtana Coberta-Ballao hoard.[Citation112] The analyses of the Ballao Project[Citation81] provided unexpected results regarding the production of oxhide ingots. The fragments from Ballao confirm that in addition to the Cypriot production, there is also – on a scale that is still to be understood – an oxhide ingot production with metal of non-Cypriot origin. Some of the ingot fragments from Ballao seem to have been produced with copper from Israel and the Timna area. The results also suggest Cambrian ores (but different from the ones of the early ingots from Aghia Triada[Citation74]), for some pieces with a still unknown signature in the European and Near Eastern Bronze Age metallurgy. The Ballao hoard is not the only context from which oxhide ingots of different provenance have been found together. This situation also occurred in the Eastern Mediterranean at the site of Zakros, on Crete.[Citation33,Citation113,Citation114]

Of particular interest is the fact that the main feature of the samples that were analyzed is the low content in 208Pb isotope (the end of the Thorium series from 232Th). This strange signature is clearly different from all other lead isotope geological data available from the Mediterranean and European mainland deposits. It is not the first time that it has been detected in Sardinian objects, but in the Funtana Coberta-Ballao hoard, it is predominant (25 out of 47 samples). This could apparently happen by using imported copper from different regions, i.e. different mines in the Sinai Peninsula and the Arabian Shield for most of them, Cyprus for some, and one or several radiogenic sites yet to be located.[Citation81]

Surprising results also arose from the metallurgical and lead isotope analyses of a small group of copper fragments, hidden in the walls of the largest known monument of its kind in Nuragic Sardinia[Citation49]: the nuraghe Arrubiu, Orroli district (Cagliari province). The Arrubiu nuraghe rises above the middle course of the Flumendosa River in the historical region of Sarcidano and has been archeologically investigated since 1981.[Citation115] The monument is characterized by a complex plan of the type known as pentalobate. This means that five towers (C-G) were built around the central tower (A), still preserved to a height of roughly 15 meters. The petrographic analyses of a Mycenaean alabastron found in the foundations of the central building strongly suggest a provenance from the Argolid, in the Peloponnese.[Citation44,Citation46,Citation116] The piece is dated to the LH IIIA2 (cf. ) and allows us to date the construction of the nuraghe to the fourteenth century BC. The collapsed material from the entire central part of the monument, Tower A, the central Courtyard B and Towers C and D, have been entirely explored, and an enormous quantity of ceramic material was recovered.[Citation49,Citation117] The nuraghe Arrubiu was abandoned between the end of the Bronze Age and the beginning of the Iron Age (tenth-ninth centuries BC) and then occupied again from the second century BC to the fifth century AD. In Roman times, two installations for the production of wine were established on top of the rubble in the central courtyard and in courtyard K on the west side, in front of the entrance to the pentalobate complex; both sealed the entrance to the inner part of the building, documenting that the ancient stratigraphic succession was unaltered. Four metal pieces were found in the nuraghe.[Citation118,Citation119] Three of them had been stuck in the wall of the elbow-shaped niche 3 that penetrates deeply into the mighty masonry of Tower A, in correspondence to the passage. Two are flat and irregular ingot fragments,[Citation34,Citation113] while the third piece probably had an oval form.[Citation34,Citation113] It can be hypothesized that they had been inserted in the interstices of the structure between the second half of the fourteenth century BC, in the phase of construction, and the twelfth century BC. The position of the pieces is sufficiently elevated to exclude any intention to retrieve and use them. This must rather have been intended as a permanent location (a hoard or an offering).

The fourth metal fragment,[Citation34,Citation113] is so small that the attribution to a flat ingot is possible only because of its low thickness, common in this category of ingots. It was found among the stones of the ceiling just over the entrance of the tortuous corridor that leads from the central Courtyard B to the Tower F,[Citation34] in one of the most impressive points of the whole monument for the dimensions of the masonry blocks. Being the quantity and weight of the metal of no possible relevance, these pieces are not likely to have been intended as a hoard or treasure, they must rather have been some sort of propitiatory offering. The metallurgical analyses carried out by Roberto Valera revealed that the fourth fragment was of impure copper (93%) with inclusions of copper sulfide and iron oxides.[Citation34] Subsequently, Ignacio Montero Ruiz carried out lead isotope analyses, discovering that the isotopic signature of these fragments of ingots matches the field of the Sinai mines (Timna and Feinan); the elemental analysis and the typology are comparable to those of other ingots found along the Israeli coast with identical isotopic signatures.

The recent publication of the analyses from the Funtana Coberta-Ballao hoard and the nuraghe Arrubiu, provide some solid evidence for metal from the southern Sinai and the Red Sea region being used in Sardinia. One possible explanation for this rather unexpected result is that Cyprus might have been not only a producer, but also a center of collection and redistribution of copper from the rest of the Eastern Mediterranean, and that Sardinia acquired copper from these eastern ores through Cyprus. However, other scenarios are also possible. One cannot exclude the possibility that, for instance, Nuragic seafaring extended beyond Cyprus or that cargoes from the Levant made their way to the Western Mediterranean. In this respect, it cannot be forgotten that although dated to the eleventh century BC, what looks like a relatively small oxhide ingot clay mold has been recovered at the site of Timna 30, Israel.[Citation59,Citation108] The geology of the copper mines in the Sinai region is still a matter of debate. Presumably, future evidence will reveal a more prominent role of Levantine copper producers in the international metal trade during the LBA than previously supposed.

Metal of Sardinian origin outside the island

It becomes more and more clear that an extensive need for metal variously linked not only different regions in and around the Mediterranean, but also that continental Europe must be included in the picture to fully understand the historical and economic development of the Mediterranean world. European Bronze Age societies all over the continent, as much as their Mediterranean counterparts, made an extensive use of bronze, widely importing copper and tin.[Citation43,Citation62–Citation64,Citation120–Citation122] Therefore, future research should take into account that the need for metal experienced by continental Bronze Age societies probably played a largely underestimated role in the international metal trade all over Europe and the Mediterranean.[Citation65–Citation68]

As already mentioned, Sardinia’s strategic position in the middle of the Western Mediterranean and the presence of local relatively rich metal deposits likely triggered and then fueled the participation of Nuragic “enterprises” in the international maritime trade throughout the LBA. Although more work is still necessary, a number of archaeometallurgical studies have variously suggested that not only metal from foreign ores was used in Nuragic productions, but also that metal of Sardinian origin was employed outside the island. Already in the 1990 s, lead isotope analyses indicated that over 20 copper and lead finds from Cyprus (Lapithos, Hala Sultan Tekke, Maa Paleokastro, Pyla-Kokkinokremos, Kition, Nitovikla Korovía, Farmagusta) and from the so-called Makarska hoard matched known Sardinia ores.[Citation106] Over a decade later the same authors[Citation75] reevaluated some of the previously published results adding new material and as many as 23 objects from LC Cyprus indicated a likely Sardinian origin (the data, although probable, must be considered provisional, since they have not been reevaluated against the growing body of lead isotope analyses from various other regions, Zofia Stos-Gale, Oxford, UK, personal communication, 2019). Twelve of those objects come from Hala Sultan Tekke, and three from Pyla-Kokkinokremos (the Cypriot sites from which Nuragic ceramic was excavated, see below). The remaining eight samples come from Kition, Maa-Paleokastro and Nitovikla. If we include the possible match excavated in Lapithos and published in 1994,[Citation106] we have finds from almost all over Cyprus that are possibly made with metal from Sardinian ores. Of the analyzed objects, 16 are made of lead, and seven are tin bronzes. It is important, however, to bear in mind that at least three of these seven bronzes might also have been produced with metal from Iberian ores. Metal ores from the Iberian Peninsula and Sardinia are contemporary and geologically older than most of the Eastern Mediterranean ones.[Citation75] It is therefore not always possible to distinguish between them.[Citation62] Recently it was also noticed that two of the main mineral districts of Sardinia (the Sulcis-Iglesiente and the Barbagia/Ogliastra area) partly overlap with the south-eastern Alpine ores of Valsugana VMS and of the South Alpine AATV, respectively. However, lower 208Pb/204Pb ratios in most Sardinian ores makes it possible to distinguish them.[Citation64]

As many as two items (not least the miniature oxhide ingot) of the debated Makarska hoard could have been made of Sardinian copper,[Citation106] while the other objects seem to come from Cyprus and from the Middle East. As noticed by Susan Sherratt[Citation123] this combination of provenances is so intriguing that it could be used to argue in favor of the hoard being indeed a coherent find and well mirroring the mid-LBA international metal trade, despite more cautious opinions.[Citation124,Citation125]

Four objects (three tools and a metal bar) of possible Sardinian origin were found in the Cape Gelidonya shipwreck. The metal bar [B223(214/BW P52 49)] contains a small amount of tin (about 0.5%) and is fully consistent with copper from Sardinian mines either of Sa Londra (Alghero, Sassari) or Funtana Raminosa (Gadoni, Nuoro).[Citation126]

A number of other artifacts from Northern Europe might have been produced with copper from Sardinia.[Citation62] The oldest artifact among them is a sword pommel from Sweden dated to the second part of the Scandinavian Bronze Age Period I (c. 1700–1500 BC). Its lead isotope composition and elemental signature seem fully consistent with the copper ores from the Sardinian mine of Calabona. A knife dated to Period II (c. 1500–1300 BC) with a lead isotope pattern that appears consistent with the ores from Funtana Raminosa also comes from Sweden (nevertheless this association must be considered with caution, because its elevated concentrations of As, Sb, Ni and Ag do not match the average chemistry of the Funtana Raminosa copper). A significant group of artifacts dating to the Nordic Period II and III (c. 1500–1100 BC) matches both the lead isotope and the elemental signatures of Sardinian copper ores. However, in the case of some of them, when looking at the sole lead isotope signature, they might also originate from Alston, Cumbria (UK), south-eastern Spain, and north Tyrol. Three recently analyzed northern European sword blades appear to have been produced with copper from Sardinian ores.[Citation63] Two of these blades come from different Danish hoards dating to the Scandinavian Period III (c. 1300–1100 BC). One was found at Sundby in the north-western part of the Jutland peninsula,[Citation64] while the other one is from Oddsherred on the island of Zealand in south-eastern Denmark. The third blade is from Germany, and although it lacks a secure context it dates to the fourteenth century BC, based on the shape of its octagonal full-hilted shaft.[Citation127] The probable matches with Sardinian copper ores continue into the Nordic Period IV and V (c. 1100-800/700 BC), but these artifacts also show a lead isotope signature that could indicate Sardinia and at the same time the Massif Central in France, or possibly north Tyrol.

Caution should of course be used with the interpretation of the lead isotope analyses, not least considering that new data are constantly being generated, and other possible ores are identified, some of them overlapping with the Sardinian signatures. However, we believe that the body of evidence – paired up with the abundant presence of tin in Sardinian metallurgy (see below) and the large number of finds of Baltic Amber on the island[Citation128–Citation130] – makes a strong case for Nuragic communities being variously involved in the long distance metal trade not only in the Mediterranean, but also with the rest of the European continent.

The tin trade

Tin added in proper quantities is a crucial component in the production of high quality bronze. Tin is found in specific locations on both the European continent and in Asia. The central Mediterranean has no tin sources of its own with the exception of Sardinia and Tuscany, in Italy, but at least in Sardinia, the possibility of ancient tin mining has been excluded.[Citation131,Citation132]

It was recently demonstrated that even though it does not yet seem possible to single out specific ores, it is possible to discriminate between Western European and Near Eastern tin deposits.[Citation120] The study of a limited number of tin ingots from Crete and from the shipwrecks of Uluburun, and Cape Gelidonya, in Turkey, and of Hishuley Carmel, Kfar Samir, and Haifa, in Israel provides new food for thought on the LBA metal trade and the sizable need of raw materials. It was established that the tin ingot excavated at Mochlos (Crete) was produced from deposits located in today’s Tadzhikistan or Afghanistan.[Citation120] On the other hand, the ingots from the underwater finds in Turkey and Israel proved to be produced with Western European tin and with high probability with metal from Cornish ores. The tin problem is not solved yet,[Citation133,Citation134] but the need for tin certainly contributed to the complexity of the metal trade and of the East-West relations in the Mediterranean during the Bronze Age.

Tin in Sardinia

A thorough archeological summing up of the problem of tin in Nuragic Sardinia[Citation133] concluded that the high number of tin finds in archeological contexts and hoards (Teti-Abini, Nuragus-Forraxi Nioi, Lei/Silanus-La Maddalena, and more recently Villagrande Strisaili-S’Arcu ’e is Forros), together with the relatively high percentage of tin added deliberately and appropriately to the abundant production of Sardinian bronze artifacts (weapons, tools, bronze vessels, ornaments, ritual objects and bronze figurines), was impressive and needed explanation. Recent advances in tin provenance studies[Citation120] indirectly support earlier hypotheses that consider Sardinia’s geographical position a key-factor to explain the abundant use of this metal locally. If consistent quantities of tin arrived to the Mediterranean via Cornwall, it seems likely that Nuragic maritime “enterprises” perhaps navigating between the West and the East may have managed to gain a prominent role in the international tin trade, aside from using it for their highly skilled bronze production in the RBA.

Considerable evidence from the end of the second millennium BC (probably to be dated to the FBA) strongly suggests that the Sardinian role in tin distribution and consumption was not episodic in nature, but instead stable throughout the Bronze Age.[Citation129,Citation131,Citation135–Citation139]

Tin at Hala Sultan Tekke

Lead isotope analyses carried out on metal artifacts from Hala Sultan Tekke[Citation75,Citation106] showed that at least seven lead finds and five bronzes could have been made of metal from Sardinia.

Hala Sultan Tekke is a harbor town and exploited one of the few natural ports offered along the south-eastern coast of Cyprus. It therefore had a strategic position for commercial endeavors, while – although some, such as for instance the Troulli inlet,[Citation140] would not be too far – none of the numerous well-known copper mining areas from the island is close to the site. This is not the place to discuss Cypriot political organization during the LC periods or the possible organization of local copper exploitation[Citation141]; however, it has been argued that in the LBA control over imports, and in particular over the distribution of tin, must have played a fundamental role for the establishment and legitimation of Cypriot Bronze Age elites.[Citation142] As in the case of the Bronze Age town of Enkomi and the later Iron Age site of Salamis (both being distant from the Troodos copper ores, but showing an incredible wealth and intensive metallurgical activities[Citation140]), geographical vicinity and direct control of the copper ores might not have been the primary interest for a key commercial harbor of the coast such a Hala Sultan Tekke. Recent archeological surveys in the Larnaka region suggest that inland valleys suffered a degree of depopulation during the LBA in favor of the attractive large coastal towns[Citation143]; hence supporting the idea that rigorous economic activity was taking place there.

Indeed, evidence for metallurgy and copper manufacture are significant at Hala. At least four different molds have been retrieved from the site through the years[Citation144] and three possible workshop areas with traces of metallurgical activity dated to different phases have been also identified.[Citation13,Citation16,Citation23,Citation145,Citation146] Most relevant in size is the area in the so-called City Quarter 2, in which a pit with over 300 kg of material related to copper-working, including slags, fragments of copper and bronze, parts of furnace walls and crucibles, was found.[Citation146] The presence in relation to these areas of an extraordinary doughnut-shaped bronze ingot[Citation14,Citation146,Citation147] and an unusual, seemingly rectangular lead ingot[Citation29,Citation147] suggest that an original, but still to be understood, production of metal might have taken place there. Metallographic and lead isotope analyses on a selection of metal samples from the current Swedish-Cyprus expedition[Citation147] confirm earlier studies[Citation75,Citation106] showing that copper arrived to Hala Sultan Tekke not only from different Cypriot districts, but also from outside the island. The limited number of samples cannot have any statistical relevance, but the results obtained so far, together with the archeological evidence, suggest that metallurgical activity at Hala was consistent and differentiated. In light of what must have been a constant need for tin[Citation142] stable relations with places like Sardinia (which might have had a significant role in the trade of Western European tin), could possibly have been of vital importance for the wealth and political economic status of groups controlling Hala Sultan Tekke metalworking. In this respect, it was noted that luxury goods at the site have often been found close to the copper-working plant, suggesting that those engaged in metalworking may have belonged to an elevated social class.[Citation13]

Results and discussion

Nuragic ceramics and oxhide ingots as indicators of maritime routes

Since the 1980 s RBA Nuragic pottery has been found outside Sardinia. To date, the material has been found at the coastal sites of Cannatello in Sicily, Lipari in the Eolian Islands, Kommos in Crete, and Hala Sultan Tekke, and Pyla-Kokkinokremos in Cyprus. Most of these sites (Cannatello, Lipari, Kommos, and Pyla-Kokkinokremos) have also produced oxhide ingots or oxhide ingot fragments.[Citation35] Oxhide ingots have a much wider distribution than Nuragic ceramics () and are generally considered, at least in their mature phases, a typical Cypriot product. However, the largest number of finds is from Sardinia, suggesting not only a special relationship between Cyprus and Sardinia, but also an intriguing role for Sardinian maritime “enterprises” in the Mediterranean metal trade.[Citation33,Citation35] We propose that in the period corresponding to the Sardinian RBA (cf. ) the presence of Nuragic pottery, alone or in combination with that of oxhide ingots, provide evidence for (at least) two main eastwards sea-routes, not forgetting the bias of absence of evidence on north Africa coasts (Carthage in Tunisia, Libyan coasts, Egyptian coasts west of Marsha Matruh in the Delta):

A southern “international” route connecting Sardinia with Cyprus and encompassing at the same time the southern coasts of Sicily and Crete.

A northern “round trip” route within the Tyrrhenian Sea connecting southern Sardinia and Lipari in the Eolian Islands.

The southern route

What we would call the southern “international” route is the waterway that connected Sardinia with the Eastern Mediterranean, in general, and with Cyprus specifically. Such a route would have included the harbors of Cannatello and Thapsos in Sicily, and of Kommos in Crete, and would possibly have arrived in Cyprus at the sites of Pyla-Kokkinokremos and/or Hala Sultan Tekke, which are both on the south-eastern coast of the island and have provided conclusive evidence of contacts with Sardinia.

Cannatello (Agrigento Province, Sicily)

The site is located on the low hill of Cannatello on the southern coast of Sicily near the modern town of Agrigento, and faces the Sicilian Channel. It is also near the mouth of the local river Cannatello and of the river Naro. It therefore has an exceptionally favorable geographical and topographical location, being on the coast, but dominating the landings and the access to the interior.

The site was discovered at the end of nineteenth century by Paolo Orsi and G.E. Rizzo,[Citation148–Citation150] and was then excavated by Angelo Mosso.[Citation151,Citation152] Among the finds from Mosso’s excavation there was a fragment of a copper oxhide ingot (unfortunately recovered without precise contextual information) that was analyzed by the Chemical Laboratory of the Royal Arsenal at Torino with the following results: Cu 99.460; Sn/; Zn 0.160; Fe 0.210; Pb/; S 0.042; As/; St 0.036; loss 0.092.[Citation151–Citation153] Later excavations (from the early 1990 s onwards) greatly enhanced the general understanding of the complex structure of the settlement.[Citation154–Citation157]

At the site, there is a great quantity of Mycenaean pottery fragments, mostly deriving from vessels with closed shapes and with decorative elements common in Cyprus (e.g. at Enkomi, Hala Sultan Tekke, and Kition) such as the stylized marine shells (FM 24), widely represented in Cypriot Mycenaean pottery of LH IIIB. From the MBA and RBA layers of Cannatello LH IIIA2-IIIB and Cypriot pottery has been also found.[Citation116] A thirteenth century pithos with wavy grooved decoration[Citation37,Citation158,Citation159] is also of Cypriot manufacture and is similar to the one from nuraghe Antigori, Sarroch (Cagliari province) of Cypriot provenance, confirmed by archaeometric analyses.[Citation116] The presence of pithoi does not necessarily imply food transportation, since they were also used for the transport of other products, such as pottery. Finally, a Cypriot White Slip bowl and three stirrup-jar handles with Cypro-Minoan alphabetic incised marks, comparable to Cypriot items, have also been found at the site. This suggests a Cypriot provenance for the local Aegean imports. This hypothesis is also indirectly supported by the clear Cypriot presence in the rest of south-eastern Sicily and at Thapsos (see below),[Citation160] recently defined a “trading center of Cypriot character” (original in Italian: nucleo emporico di caratterizzazione cipriota).[Citation161]

The evidence from Cannatello suggests that the site was part of a systematic route, which apparently was well-defined since the Early Bronze Age as suggested by the evidence from the sulfur mines and furnaces of Monte Grande and a base for contacts between Aegean-Cypriot traders and the inland local peoples (Milena).[Citation36,Citation83,Citation162–Citation165] Additionally, due to its geographical position, the Agrigento region represents a natural link in the East-West metal trade with Sardinia and also perhaps, later on, the Iberian Peninsula.[Citation155,Citation164,Citation166]

The discovery of Nuragic pottery at Cannatello has been presented in preliminary terms only,[Citation156,Citation167] but it seems to come from all over the site and from the RBA, and perhaps also from the beginning of FBA levels. A few types are illustrated in Vanzetti’s seriation table, all with thickened rims.[Citation168] They consist of containers of different shapes and dimensions, including dolia, cups, bowls, and large lenticular bowls, made of Nuragic RBA gray impasto pottery. The thickened rim is a consistent feature in this material.

The fact that the imports of Nuragic pottery seem to decrease in LH IIIB, and in coincidence with the diminution of Cypriot imports, is relevant for the scope of this paper. Preliminary results of ongoing petrographic and mineralogical analyses showed that many Nuragic type vessels were made locally,[Citation156,Citation157] suggesting a more stable presence of individuals of Nuragic origin or a wide acquaintance with the Nuragic world. On the other hand, the large impasto pithoi (primary container used for traded goods) seem to be of Sardinian origin, and reinforce the idea of regular trading contacts.

Thapsos (Syracuse Province, Sicily)

The settlement of Thapsos is located on a wide, almost flat area about 1 km long and between 30 and 250 m wide, on the promontory dominating the isthmus of the Magnisi peninsula on the Augusta gulf, north of Syracuse. The settlement is fortified on the eastern side and overlooks two natural harbors on either side of the isthmus, which offer double protection against sea storms. The combination of the strategic location with the fertility of the inland territory provided an ideal site for the development of the trading port.

The first archeological excavations, conducted at the end of nineteenth century by Paolo Orsi,[Citation149,Citation169] were mostly concentrated on the necropolis of rock-cut tombs along the coast and further inland. In the 1970 s and 1980 s Giuseppe Voza conducted scientific research on the settlement on the isthmus and, despite the fact that the structures were poorly preserved due to the small quantity of soil covering the site, the results were of great interest.[Citation160,Citation170–Citation172] The excavations directed by Paolo Orsi discovered a large quantity of Mycenaean pottery in the necropolis, attributed to LH IIIA1, LH IIIA2 and in some cases LH IIIB, or the end of fifteenth – beginning of thirteenth centuries BC (cf. ).[Citation160]

At Thapsos, like at Cannatello, a wealth of Cypriot pottery, both imported and locally imitated, was recovered. A significant example of the international material culture of the site is apparent in the combination of finds from grave D. This tomb was furnished with: two LC II Base Ring II juglets, of local, non-Cypriot manufacture; a white-shaved juglet, widely distributed in the Near East and Egypt during the periods LC I-LC II (MBA/RBA – fourteenth- thirteenth century BC, cf. ); imported Mycenaean pottery and local pottery of the Thapsos culture.[Citation36,Citation116,Citation164,Citation173] It should be also mentioned that both at Cannatello and at Thapsos, Maltese pottery was found as well, adding yet another layer to the complexity of the Mediterranean international trade systems during the Late Bronze Age.[Citation156,Citation174,Citation175]

Thapsos was a trading port, as it handled the agricultural surplus from the nearby settlements and regions. The increase in the storage of foodstuffs, documented by the pithoi in the deposit-quarters, is a symptom of a developed chiefdom, and demonstrates that there existed a class of people (artisans and traders) not directly involved in the agricultural production, and that there was a surplus, which in turn could support the establishment of trade.[Citation164] At Thapsos, a fragment of the central part of an oxhide ingot was also found.[Citation35] The piece has been sampled and analyzed by atomic absorption spectrometry by Alessandra Giumlia-Mair with the following results: Cu 97; Sn/; As 0.6; Sb tr.; Pb/; Ni 0.2; Fe 0.3; Co tr.; Zn/; Ag 0.07; Mn/.

Until now, there has been no evidence of Nuragic pottery at Thapsos, but it has to be stressed that no complete studies of all materials have been carried out and published.

Kommos (south-eastern Crete)

Kommos is a powerful harbor site on south-eastern Crete, closely related to its neighbor sites of Ayia Triada and Phaistos.[Citation176] The site is much more than just a harbor with access to the fertile Mesara plain in southern Crete and to the Libyan Sea: it was a wealthy urban milieu as well. Long-term and regularly published archeological excavations since 1976 brought to light a complex urban settlement with monumental buildings and workshop areas.[Citation176–Citation181] Additionally the site has a long history of occupation from the Middle Minoan IIB (corresponding to the LH IIB) to the post-palatial period, around 1200 BC.

Already in the late 1980 s, Nuragic pottery was recognized among the many finds from the site, and subsequently published. The ceramic remains were found scattered all over the site in levels dated LH IIIB and LH IIIC.[Citation182–Citation185] Moreover, a hoard of six pieces of oxhide ingots was found in Room N in a Late Minoan IIIB (LH IIIB) level; one of them being sampled and submitted to lead isotope analysis, is made of copper from Cyprus.[Citation186] Ongoing petrographic and mineralogical analyses of Mycenaean, Nuragic and local style pottery reveal evidence of connections with Sicilian (Cannatello) and Sardinian (Selargius) settlements (Peter M. Day, University of Sheffield, UK, personal communication, 2019).

Pyla-Kokkinokremos (Larnaca District, Cyprus)

The detection of Nuragic pottery at the site of Pyla-Kokkinokremos on the south-eastern coast of Cyprus was one of the most sensational discoveries of recent years. A Nuragic jar, digitally reconstructed by a sophisticated virtual procedure, was recognized thanks to the discovery of a so-called “upside-down elbow” handle, typical of Nuragic Sardinia, and usually found in pairs on globular or ovoid necked jars. Petrological and chemical analyses established a Sardinian provenance, from the Sulcis region. The lead isotope analysis on the Pyla-Kokkinokremos jar lead clamp, carried out by Nöel H. Gale,[Citation187] confirmed the provenance from Sa Duchessa, one of the richest polymetallic deposits of the Sulcis district. This established that the jar was made, broken, and repaired in south-western Sardinia, and then brought to Cyprus where it ended its journey.[Citation33]

New archeological excavations directed by Joachim Bretschneider, Athanasia Kanta and Jan Driessen have taken place since 2014.[Citation188–Citation190] The site, located in a strategic position on the flat top of a naturally fortified hill overlooking the sea, is different from other Cypriot settlements because of its unusually short life – more or less a single generation in a critical period – between the LC IIC and the LC IIIA (c. 1230–1170 BC). For this reason, it is called “a time capsule”. The variety of provenances represented in the material associated with local Cypriote production is surprising: imported Mycenaean, Minoan, Nuragic, Hittite, and Canaanite pottery. In 2017, excavations in the central and northern sectors of the Kokkinokremos plateau concentrated on Trenches 3.3 and 3.4. Space 3.3.23 yielded an Egyptian alabaster amphora, adding to the growing corpus of Egyptian alabaster vessels found at the site. Space 3.3.16, possibly only accessible from the outside of the settlement, produced two Sardinian olle a colletto, bringing the total number of Sardinian vessels found at the site to four (–). Thanks to the discovery of Nuragic tableware at Hala Sultan Tekke, it seems that similar ceramics have been now found in sector 5 at Pyla (Joachim Bretschneider, Ghent University, personal communication, 2020). This exceptional finding supports the strong possibility of a Sardinian presence at Kokkinokremos as well.[Citation190]

Hala Sultan Tekke (Larnaca District, Cyprus)

The discovery of Sardinian Nuragic pottery at Hala Sultan Tekke is very recent and in the course of publication.[Citation1,Citation2] As discussed in the introduction, the harbor site of Hala Sultan Tekke was a LC urban settlement of considerable size, placed in a strategic position, dominating one of the few natural harbors of the Cypriot southern costs. As demonstrated by the many finds, Hala must have been exceedingly significant and well-integrated on international routes of maritime exchange and trade.

The Sardinian bowls come from the extra-urban cemetery or Area A of the excavations. They were found in various locations, including three offering pits filled with material that securely dates them to the LC IIC or roughly to the thirteenth century BC.[Citation1]

Oxhide ingots in the far West: Corsica, South France and the Iberian Peninsula

It is likely that in the RBA, at least some of the oxhide ingots in the West (e.g. the ones from Sicily) were brought by Nuragic maritime “enterprises” rather than Cypriot ones. One can hardly doubt that Nuragic Sardinia must have played an intermediary role with the two oxhide ingots found at S. Anastasìa-Borgo in Corsica near Bastia and at Sète-Hérault in the south of France.[Citation99–Citation102] Unfortunately, none is from a datable context. Lead isotope analysis of the Corsican ingot indicated a Cypriot provenance (Ernst Pernicka, University of Heidelberg, personal communication, 2019),[Citation33] while no results have been so far obtained from the Sète-Hérault item.

As to the far West, one should mention that during the FBA the archeological record registers a notable resumption of interest between Nuragic Sardinia and the Iberian Peninsula and possibly the Atlantic Bronze Age world.[Citation191–Citation193] Differently from other important actors of the Mediterranean world at the onset of 1200 BC, archeological evidence from Sardinia does not show dramatic signs of crisis. Once again, the geographical position of the island in the center of the Western Mediterranean might have played a determinant role. Yet, in this respect, a small, but possibly relevant evidence can be mentioned. Among the various specimens analyzed for the Project Plata Preromana en Cataluña,[Citation194] a fragment of copper ingot of unclassifiable shape, but noticeable for its exceptional purity (Cu 99%) was discovered. The lead isotope analyses indicate a Cypriot provenance from the Larnaca area, suggesting that the ingot could be a residue on the route, along which oxhide and plano-convex ingots were brought from East to West. The piece cannot be dated, and comes from the site of Ampurias (the ancient Emporion) founded by the Phocaeans of Massalìa (Marseilles) around the fifth century BC. The name of the site (meaning “market” in Greek) suggests a place for the trade and exchange of commodities, and the piece might well be evidence of a much earlier frequentation of the area for trading purposes long before the arrival of the Phocaeans.[Citation33] In such a case, the history of this fragment would not be different from that of other copper oxhide ingots that, at the time of the first navigation of the Phoenicians toward the West might have originated the legend of Elissa and her purchase of the Byrsa through the artifice of cutting the skin of an ox into strips and so enclosing the promontory where Carthage was then founded.[Citation195]

The northern “round trip” route

Lipari (Eolian Islands, Italy)

The excavations in Lipari were conducted by Luigi Bernabò Brea and Madeleine Cavalier from the 1950 s, and adequately published in the series of Meligunìs-Lipàra, including the hoard of the alpha II hut.[Citation196] However, this is not the place to present this well-known site in any detail.[Citation33,Citation164,Citation195,Citation197,Citation198] The total weight of the hoard is 75 kg. It consists of weapons and tool fragments; there is not one single complete object, nor one fragment, which matches another.[Citation196] The majority consists of unworked fragments (354) of metal ingots, all graphically documented and analyzed by Alessandra Giumlia-Mair.[Citation198] In the hoard, there are mixed fragments of oxhide and plano-convex ingots that can be distinguished from each other because of their shape and that of the layered metal structure, visible in the section. On oxhide and plano-convex ingot fragments there are very clear traces of mechanical cuts for which some kind of blade, possibly a large chisel or sharp tool of around 2 or 3 cm, was employed. Considering the typology of the objects, the chronology of the hoard is broad (thirteenth-twelfth centuries BC). The burial, based on the few most recent objects, can be dated to the end of the local Ausonio I/beginning of Ausonio II periods, thus is contemporary with the beginning of the FBA on the Italian mainland. In the LBA the Eolian islands document multidirectional contacts. Exchange with the Aegean was not interrupted (LH IIIB-IIIC pottery in the FBA levels in Lipari), and their importance in the trade routes toward the mainland and Sardinia is evident.[Citation164]

During the excavations, Bernabò Brea recognized foreign sherds among the Lipari Acropolis materials, soon identified by Ercole Contu as being Nuragic.[Citation199] Subsequently, Maria Luisa Ferrarese Ceruti[Citation200] reexamined them. As new and better classified local comparisons had been published by then, she was able to attribute them to the so-called pre-Geometric style, found in the village of S’Urbale (Teti district, Nuoro province), and date them to the advanced FBA, around the eleventh century BC.[Citation201]

In 2000 a new and extensive study collected all Bronze Age pottery published in Sardinia and set out a broad typology,[Citation202] providing a solid base for any future study, such as the recent new classification of Nuragic pottery from the Lipari Acropolis. The new study not only confirms the earlier impressions that the local Nuragic pottery should be dated to various periods, but also that it could be found in different areas of the settlement.[Citation203,Citation204] The relationship between Lipari and Nuragic Sardinia was therefore most likely regular, rather than episodic, and possibly followed a “round trip” route; the hypothesis is based on the absence of oxhide ingots and of Nuragic RBA and early FBA pottery on the Italian Peninsula, suggesting a seaborne route that completely excluded the Italian mainland.

Conclusions

The earlier discovery of the significant Nuragic presence at the so-called “time capsule” site of Pyla-Kokkinokremos had been striking. Left on the ground, a complete double-handled jar of the very same type of the Nuragic jars found at Kommos has been attributed to commercial use, being a container appropriate for the transportation of liquids or food.

The several Nuragic bowls from Hala Sultan Tekke document, for the first time, that fine ceramics of Sardinian burnished gray ware () were also circulating in the Eastern Mediterranean. Their characteristics and number strongly suggest that people of Sardinian origin were in direct contact with the local population at Hala Sultan Tekke. Given their presumed use as offerings in the necropolis, it is possible that people of Sardinian origin might have been living (temporarily?) in the settlement and perhaps participated in local burial ceremonies.

The two Cypriot sites are completely different. Pyla was a short-lived, naturally fortified site with a surprising variety of “international” material culture. Hala is a large harbor town with striking evidence of craft production, including intensive metallurgy, which we assume probably represented a main attraction for Nuragic maritime “enterprises”.

Provenance studies carried out on bronze and copper finds from the Mediterranean and continental Europe now demonstrate that the LBA metal trade was broad and complex. Furthermore, it is also clear that continental Bronze Age communities and the Mediterranean world networked in manifold ways in what was apparently a great need for metal. The presence of several ”foreign/exotic” goods and materials (such as Mesopotamian glass, Mycenaean ceramics, and Baltic amber[Citation205]), and the abundance of tin in local metal production, strongly suggest that Nuragic communities were actively involved in the international metal trade. A topic for future studies would be to investigate how we can better define and understand what we daringly called Nuragic maritime “enterprises”, and identify what the other driving forces were that complemented the picture and which acted side by side in the long-distance metal trade.

One aspect that has been widely discussed to demonstrate the particular and specific close relationship between Sardinia and Cyprus, and which was not mentioned in this work, is the presence of metallurgical instruments of similar types on both islands.[Citation84,Citation206] The archeological record of those instruments, and for the technology in which they were employed, raises the important issue of knowledge transfer not only in the relationship between Sardinia and Cyprus, and – as in the case of Sardinia – for the development of the local metal production, but also on a more general level. We argue that in Bronze Age studies, the role of technological know-how has been underestimated, and that more accurate work should be undertaken to understand the impact of new technological skills on significant historical, social, and cultural transformations throughout the period.

For example, lead isotope studies on bronze objects from northern Europe[Citation62–Citation64] proved that Scandinavian Bronze Age societies did not consistently use the locally available copper resources. In all probability, one reason for this could be the lack of appropriate technology to exploit the local ores, while the long-distance metal trade was likely to have already been provided the necessary metal supplies (and possibly at “reasonable costs”?!).

Metal production, distribution, and consumption must have been a dynamic undertaking through time as recently demonstrated by the interesting shift in mining activity at the British Great Orme mines.[Citation207] Not only did marked shifts in copper supplies take place, possibly responding to processes of cultural and political changes, but the transfer of/access to technological know-how must also have had a vital role. The importance of the political and economic balance between the demand of specific bulk goods such as copper and tin and the ability to control their production and distribution was probably a key factor during the Bronze Age.[Citation65] In this picture, strategically positioned intermediate actors such as Nuragic Sardinia – able to control both seaborne routes and access to an advanced metallurgical technology – were probably able to gain a dominant position.

Acknowledgments

The core arguments of this paper were initially conceived as part of the appendix to Bürge & Fischer 2020[Citation1], announcing the discovery of Sardinian fine ware at Hala Sultan Tekke. However, it became soon clear that the subject is wide and complex and needs a specific and broader assessment. We are grateful to Alessandra Giumlia-Mair, Mark Pearce, Kristian Kristiansen and the anonymous peer-reviewer for their invaluable comments. We wish to thank Kristin Bornholdt Collins for revising the English. This work, and in particular Serena Sabatini’s contribution, has been possible thanks to the support of The Swedish Foundation Riksbankens Jubileumsfond under Project Grant M16-0455:1 Towards a new European Prehistory. Integrating aDNA, isotopic investigations, language and archaeology to reinterpret key processes of change in the prehistory of Europe. The authors strictly collaborated, co-wrote the Introduction and the Conclusions; Serena Sabatini wrote the Materials and Methods section and Fulvia Lo Schiavo wrote the texts of the Results and Discussion section.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bürge, T.; Fischer, P. M., with an appendix by; Sabatini, S.; Perra, M.; Gradoli, M. G. Nuragic Pottery from Hala Sultan Tekke: The Cypriot-Sardinian Connection. Egypt Levant. 2020, XXIX(2019), 231–244.

- Gradoli, M. G.; Waiman-Barak, P.; Bürge, T.; Dunseth, Z. C.; Sterba, J. H.; Lo Schiavo, F.; Perra, M.; Sabatini, S.; Fischer, P. M. Cyprus and Sardinia in the Late Bronze Age: Nuragic Table Ware at Hala Sultan Tekke. Submitted J Archaeol Sci.

- Åström, P.; Hala Sultan Tekke, Part 8. Excavations 1971-1979 (SIMA 45:8); Astrom Editions: Gothenburg, 1983.

- Åström, P.; Hala Sultan Tekke, Part 9. Trenches 1972-87. Index for Volumes 1-9 (SIMA 45:9); Astrom Editions: Gothenburg, 1989.

- Åström, P.; Hala Sultan Tekke, Part 10. The Wells (SIMA 45:10); Astrom Editions: Gothenburg, 1998.

- Åström, P.; Hala Sultan Tekke, Part 11. Trial Trenches at Dromolaxia-Vyzakia Adjacent to Areas 6 and 8; Astrom Editions: Gothenburg, 2001.

- Åström, P.; Bailey, D. M.; Karageorghis, V. Hala Sultan Tekke Part 1. Excavations 1897-1971; Astrom Editions: Gothenburg, 1976.

- Åström, P.; Hult, G.; Strandberg Olofsson, M. Hala Sultan Tekke Part 3. Excavations 1972; Astrom Editions: Gothenburg, 1977.

- Åström, P.; Nys, K., Eds. Hala Sultan Tekke Part 12. Tomb 24, Stone Anchors, Faunal Remains and Pottery Provenance; Astrom Editions: Göteborg, 2007.

- Fischer, P.; The New Swedish Cyprus Expedition 2010. Excavations at Dromolaxia Vizatzia/Hala Sultan Tekke. Opuscula. 2011, 4, 69–98. DOI: 10.30549/opathrom-04-04.

- Fischer, P.; The New Swedish Cyprus Expedition 2010. Excavations at Hala Sultan Tekke. Opuscula. 2012, 5, 89–112. DOI: 10.30549/opathrom-05-04.

- Fischer, P.; Bürge, T. The New Swedish Cyprus Expedition 2012. Excavations at Hala Sultan Tekke. Opuscula. 2013, 6, 45–79.

- Fischer, P.; Bürge, T. The New Swedish Cyprus Expedition 2013. Excavations at Hala Sultan Tekke. Opuscula. 2014, 7, 61–106. DOI: 10.30549/opathrom-07-04.

- Fischer, P.; Bürge, T. The New Swedish Cyprus Expedition 2014. Excavations at Hala Sultan Tekke. Opuscula. 2015, 8, 27–79. DOI: 10.30549/opathrom-08-03.

- Fischer, P.; Bürge, T. The New Swedish Cyprus Expedition 2015. Excavations at Hala Sultan Tekke. Opuscula. 2016, 9, 33–58. DOI: 10.30549/opathrom-09-03.

- Fischer, P.; Bürge, T. The New Swedish Cyprus Expedition 2016. Excavations at Hala Sultan Tekke (The Söderberg Expedition). Opuscula. 2017, 10, 51–93. DOI: 10.30549/opathrom-10-03.

- Fischer, P.; Bürge, T. The New Swedish Cyprus Expedition 2017. Excavations at Hala Sultan Tekke (The Söderberg Expedition). Opuscula. 2018, 11, 30–79. DOI: 10.30549/opathrom-11-03.

- Fischer, P.; Bürge, T., Eds. Two Late Cypriot City Quarters at Hala Sultan Tekke. The Söderberg Expedition 2010–2017; Astrom Editions: Uppsala, 2018.

- Hult, G.; Hala Sultan Tekke Part 7. Excavations in Area 8 in 1977; Astrom Editions: Gothenburg, 1981.

- Hult, G.; McCaslin, D. E. Hala Sultan Tekke Part 4. Excavations in Area 8 1974-75 and the 1977 Underwater Report; Astrom Editions: Gothenburg, 1978.

- Öbrink, U.; Hala Sultan Tekke, Part 5. Excavations in Area 22; Astrom Editions: Gothenburg, 1979.

- Öbrink, U.; Hala Sultan Tekke Part 6. A Sherd Deposit in Area 22; Astrom Editions: Gothenburg, 1979.

- Åström, P.; A Coppersmith’s Workshop in Hala Sultan Tekke. In Periplus. Festschrift für Hans-Günter Buchholz zu seinem achtzigsten Geburtstag am 24 Dezember 1999; Sürenhagen, D., Ed.; Astrom Editions: Uppsala, 2000; pp 33–36.

- Reese, D. S.; Shells from Sarepta (Lebanon) and East Mediterranean Purple-dye Production. Mediterr. Archaeol. Archaeometry. 2010, 10, 113–141.

- Sabatini, S.; Textile Production Tools. In Two Late Cypriot City Quarters at Hala Sultan Tekke. The Söderberg Expedition 2010-2017; Fischer, P., Bürge, T., Eds.; Astrom Editions: Uppsala, 2018; pp 431–456.

- Smith, J. S.; Bone Weaving Tools of the Late Bronze Age. In Contributions to the Archaeology and History of the Bronze and Iron Ages in the Eastern Mediterranean. Studies in Honour of Paul Åström; Fischer, P., Ed.; Österreichisches Archäologisches Institut: Vienna, 2001; pp 83–90.

- Fischer, P.; Satraki, A. Appendix 1: “Tomb” A from Hala Sultan Tekke 2013. Opuscula. 2014, 7, 86–88.

- Lindquist, A.; Appendix 3: Plaques from Pit B. Opuscula. 2015, 8, 71–72.

- Recht, L.; Appendix I: A Lead Ingot and Lead Production at LBA Hala Sultan Tekke. Opuscula. 2017, 10, 75–82.

- Bürge, T.; Appendix 4: A Violin Bow Fibula from Hala Sultan Tekke. Opuscula. 2014, 7, 95–96.

- Russell, A.; Knapp, A. B. Sardinia and Cyprus: An Alternative View on Cypriotes in the Central Mediterranean. Pap Br School Rome. 2017, 85, 1–35. DOI: 10.1017/S0068246216000441.

- Lo Schiavo, F.; Campus, F. Metals and Beyond: Cyprus and Sardinia in the Bronze Age Mediterranean Network. In Un Millénaire d’Histoire et d’Archéologie Chypriotes (1600-600 av. J.-C.), Colloque International Sous le Haut Patronage du Président de la République Italienne (Milano 18-19 Octobre 2012) Pasiphae; Negri, M., Sacconi, A., Eds.; 2013; Vol. VII, pp 147–158. Fabrizio Serra Editore: Pisa, Italy.

- Lo Schiavo, F.; Lingotti Oxhide E Oltre. Sintesi Ed Aggiornamenti Nel Mediterraneo E in Sardegna/Oxhide Ingots and Beyond. Synthesis and Updating in the Mediterranean and in Sardinia. In Bronze Age Metallurgy in the Mediterranean Islands, in Honour of Robert Maddin and Vassos Karageorghis; Giumlia-Mair, A., Lo Schiavo, F., Eds.; Éditions Mergoil: Drémil-Lafage, 2018; pp 13–55.

- Lo Schiavo, F. I.; Lingotti Piano-Convessi Ed Altre Forme Di Lingotto/The Plano-Convex Ingots and Other Shapes of Ingot. In Bronze Age Metallurgy in the Mediterranean Islands, in Honour of Robert Maddin and Vassos Karageorghis; Giumlia-Mair, A., Lo Schiavo, F., Eds.; Éditions Mergoil: Drémil-Lafage, 2018; pp 57–135.

- Lo Schiavo, F.; Muhly, J.; Maddin, R.; Giumlia-Mair, A., Eds. The Oxhide Ingots in the Central Mediterranean; ICEVO-CNR: Rome, 2009.

- Lo Schiavo, F.; Macnamara, E.; Vagnetti, L. Late Cypriote Imports to Italy and Their Influence on Local Bronzework. Pap Br School Rome. 1985, 1985(53), 1–71. DOI: 10.1017/S0068246200011491.

- Vagnetti, L.; Lo Schiavo, F. Late Bronze Age Long Distance Trade: The Role of the Cypriots. In Early Society in Cyprus; Peltenburg, E., Ed.; Edinburgh University Press: Edinburgh, 1989; pp 217–243.

- Cardarelli, A.; Different Forms of Social Inequality in Bronze Age Italy. Origini. 2015, XXXVIII, 156.

- Leonelli, V.; La Sardegna nel Periodo dei Modelli di Nuraghe. In Simbolo di un Simbolo. I Modelli di Nuraghe; Campus, F., Leonelli, V., Eds.; ARA Edizioni: Monteriggioni, Italy, 2012; pp 44–45.

- Lo Schiavo, F.; Perra, M. From the Aegean to Nuragic Sardinia. History and Development of a Misused Instrument: The Chronological Table. In MEDITERRANEA ITINERA. Studies in Honour of Lucia Vagnetti; Bettelli, M., Del Freo, M., van Wijngaarden, G. J., Eds.; ISMA-CNR: Rome, 2018; pp 51–66.

- Manning, S. W.; Chronology and Terminology. In The Oxford Handbook of the Bronze Age Aegean; Cline, E., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2010; pp 11–28.

- Steel, L.; Cyprus during the Late Bronze Age. In The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of the Levant: C. 8000-332 BCE; Killebrew, A. E., Steiner, M., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2013; pp 577–591.

- Giumlia-Mair, A.; Lo Schiavo, F., Eds. Bronze Age Metallurgy in the Mediterranean Islands, in Honour of Robert Maddin and Vassos Karageorghis; Éditions Mergoil: Drémil-Lafage, 2018.

- Lo Schiavo, F.; Vagnetti, L. Alabastron Miceneo Dal Nuraghe Arrubiu Di Orroli (Nuoro). Rendiconti dell’Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei (serie IX). 1993, IV, 121–148.

- Vagnetti, L.; L’Alabastron Miceneo del Nuraghe Arrubiu. In La Vita Nel Nuraghe Arrubiu (Arrubiu 3); Cossu, T., Campus, F., Leonelli, V., Perra, M., Sanges, M., Eds.; Comune di Orroli - Laboratorio della Conoscenza e della Memoria: Dolianova, Italy, 2003; pp p 32.

- Vagnetti, L.; L’Alabastron Miceneo del Nuraghe Arrubiu. In Il Nuraghe Arrubiu di Orroli, Volume 1. La Torre Centrale e il Cortile B: Il Cuore del Gigante Rosso; Eds, Lo Schiavo, F., Perra, M. Arkadia Editore: Cagliari, Italy, 2017. pp 161–162.

- Ferrarese Ceruti, M. L.; Ceramica Micenea in Sardegna (Notizia Preliminare). Rivista Di Scienze Preistoriche. 1979, Vol. XXXIV, pp 243–253.

- Lo Schiavo, F.; Vagnetti, L.; Ferrarese Ceruti, M. L. Micenei in Sardegna? In Rendiconti della Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei, Classe di Scienze Morali, Bardi Edizioni: Rome, 1980; Vol. XXXV, pp 372–391.

- Lo Schiavo, F.; Perra, M., Eds. Il Nuraghe Arrubiu di Orroli, Volume 1. La Torre centrale e il Cortile B: Il cuore del Gigante Rosso (Collana Itinera 18); Arkadia Editore: Cagliari, Italy, 2017.

- Lo Schiavo, F.; The Bronze Age in Sardinia. In The Oxford Handbook of the European Bronze Age; Fokkens, H., Harding, A., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2013; pp 668–691.

- Lo Schiavo, F.; Sea and Sardinia: Nuragic Bronze Boats. In In Ancient Italy in Its Mediterranean Setting, Studies in Honour of Ellen Macnamara (Accordia 4 Specialist Studies on the Mediterranean, 4); Ridgway, D., Serra Ridgway, F. R., Pearce, M., Herring, E., Whitehouse, R. D., Wilkins, J. B., Eds.; Accordia Research Institute/University of London: London, 2000; pp 141–158.

- Lo Schiavo, F.; Late Cypriot Bronzework and Bronzeworkers in Sardinia, Italy and Elsewhere in the West. In Italy and Cyprus in Antiquity 1500-450 BC. In Proceedings of an International Symposium Held at the Italian Academy for Advanced Studies in America at Columbia University, November 16-18, 2000; Bonfante, L., Karageorghis, V., Eds.; Costakis and Leto Severis Foundation: Nicosia, 2001; pp 131–152.

- Lo Schiavo, F.; Antona, A.; Bafico, S.; Campus, F.; Cossu, T.; Fonzo, O.; Forci, A.; Garibaldi, P.; Isetti, E.; Lanza, S. La Sardegna. Articolazioni Cronologiche e Differenziazioni Locali - La Metallurgia. In L’Età del Bronzo Recente in Italia, Atti del Congresso Nazionale di Lido di Camaiore, 26-29 Ottobre 2000; Cocchi Genick, D., Ed.; M. Baroni: Viareggio, Italy, 2004; pp 357–382.

- Lo Schiavo, F.; Perra, M. Introduzione. In Il Nuraghe Arrubiu Di Orroli, Volume 2. La ‘Tomba Della Spada’ E La Torre C: La Morte E La Vita Del Nuraghe Arrubiu; Perra, M., Lo Schiavo, F., Eds.; Arkadia Editore: Cagliari, Italy, 2018; pp 15–16.

- Lo Schiavo, F.; Un Simbolo nel Simbolo: I Nuraghi e le Navicelle. In Simbolo di un Simbolo. Modelli di Nuraghe; Campus, F., Leonelli, V., Eds.; ARA Edizioni: Monteriggioni, Italy, 2012; pp 58–69.

- Campus, F.; Leonelli, V., Eds. Simbolo di un simbolo. I modelli di nuraghe; ARA Edizioni: Monteriggioni, Italy, 2012.

- Leonelli, V.; Il Modello di Nuraghe, Strumento Politico. In Simbolo di un Simbolo. Modelli di Nuraghe; Campus, F., Leonelli, V., Eds.; ARA Edizioni: Monteriggioni, Italy, 2012; pp 46–48.

- Ling, J.; Stos-Gale, Z. Representations of Oxhide Ingots in Scandinavian Rock Art: The Sketchbook of a Bronze Age Traveller? Antiquity. 2015, 89, 191–209. DOI: 10.15184/aqy.2014.1.

- Sabatini, S.; Late Bronze Age Oxhide and Oxhide-like Ingots from Areas Other than the Mediterranean: Problems and Challenges. Oxford J Archaeol. 2016, 35, 29–45. DOI: 10.1111/ojoa.12077.

- Sabatini, S.; Revisiting Late Bronze Age Copper Oxhide Ingots: Meanings, Questions and Perspectives. In Local and Global Perspectives on Mobility in the Eastern Mediterranean; Aslaksen, O. C., Ed.; Norwegian Institute in Athens: Athens, 2016, 15–62.

- Primas, M.; Pernicka, E. Der Depotfund Von Oberwilflingen. Germania. 1998, 76, 25–65.

- Ling, J.; Stos-Gale, Z.; Grandin, L.; Billström, K.; Hjärthner-Holdar, E.; Persson, P.-O. Moving Metals II: Provenancing Scandinavian Bronze Age Artefacts by Lead Isotope and Elemental Analyses. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2014, 41, 106–132. DOI: 10.1016/j.jas.2013.07.018.

- Ling, J.; Hjärthner-Holdar, E.; Grandin, L.; Stos-Gale, Z.; Kristiansen, K.; Melheim, A. L.; Artioli, G.; Angelini, I.; Krause, R.; Canovaro, C. Moving Metals IV: Swords, Metal Sources and Trade Networks in Bronze Age Europe. J Archaeol Sci Rep. 2019, 26, 101837. DOI: 10.1016/j.jasrep.2019.05.002.

- Melheim, L.; Grandin, L.; Persson, P.-O.; Billström, K.; Stos-Gale, Z.; Ling, J.; Williams, A.; Angelini, I.; Canovaro, C.; Hjärthner-Holdar, E.;; et al. Moving Metals III: Possible Origins for Copper in Bronze Age Denmark Based on Lead Isotopes and Geochemistry. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2018, 96, 85–105. DOI: 10.1016/j.jas.2018.04.003.

- Earle, T.; Ling, J.; Uhnér, C.; Stos-Gale, Z.; Melheim, L. The Political Economy and Metal Trade in Bronze Age Europe: Understanding Regional Variability in Terms of Comparative Advantage and Articulations. Eur J Archaeol. 2015, 18, 633–657. DOI: 10.1179/1461957115Y.0000000008.

- Kristiansen, K.; Interpreting Bronze Age Trade and Migration. In Human Mobility and Technological Transfer in the Prehistoric Mediterranean; Kiriatzi, E., Knappett, C., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2016; pp 154–181.

- Rowlands, M.; Ling, J. Boundaries, Flows and Connectivities: Mobility and Stasis in the Bronze Age. In Counterpoint: Essays in Archaeology and Heritage Studies in Honour of Professor Kristiansen Kristiansen, British Archaeological Report International Series 2508; Bergerbrant, S., Sabatini, S., Eds.; Archaeopress: Oxford, 2013, 517–529.

- Sabatini, S.; Melheim, L. Nordic-Mediterranean Relations in the Second Millennium BC. In New Perspectives on the Bronze Age Proceedings of the 13th Nordic Bronze Age Symposium Held in Gothenburg 9th to 13th June 2015; Bergerbrant, S., Wessman, A., Eds; Archaeopress: Oxford, 2017, pp 355–362.

- Begemann, F.; Schmitt-Strecker, S.; Pernicka, E.; Lo Schiavo, F. Chemical Composition and Lead Isotopy of Copper and Bronze from Nuragic Sardinia. Eur J Archaeol. 2001, 4, 43–85. DOI: 10.1179/eja.2001.4.1.43.

- Gale, N. H.; Lead Isotope Studies – Sardinia and the Mediterranean: Provenance Studies of Artefacts Found in Sardinia. Instrumentum. 2006, 23, 29–34.

- Hauptmann, A.; Maddin, R.; Prange, M. On the Structure and Composition of Copper and Tin Ingots Excavated from the Shipwreck of Uluburun. Bull Am Schools Orient Res. 2002, 328, 1–30. DOI: 10.2307/1357777.

- Montero Ruiz, I.; Lingotes De Cobre Del Nuraghe Arrubiu De Orroli. In Il Nuraghe Arrubiu di Orroli, Volume 1. La Torre Centrale e il Cortile B: Il Cuore del Gigante Rosso; Lo Schiavo, F., Perra, M., Eds.; Arkadia Edizioni: Cagliari, Italy, 2017, pp CDrom, 2.4.

- Pernicka, E.; Lutz, J.; Stöllner, T. Bronze Age Copper Produced at Mitterberg, Austria, and Its Distribution. Archaeologia Austriaca. 2016, 100, 19–55. DOI: 10.1553/archaeologia100s19.

- Stos, Z. A.; Biscuits with Ears:” A Search for the Origin of the Earliest Oxhide Ingots. In Metallurgy: Understanding How, Learning Why. Studies in Honour of James D. Muhly; Betancourt, P. P., Ferrence, S. C., Eds.; INSTAP Academic Press: Philadelphia, PE, 2011; pp 221–229.

- Stos-Gale, Z.; Gale, N. H. Bronze Age Metal Artefacts Found on Cyprus - Metal from Anatolia and the Western Mediterranean. Trabajos de Prehistoria. 2010, 67, 389–403. DOI: 10.3989/tp.2010.10046.

- Bevan, A.; Making and Marking Relationships: Bronze Age Branding and Mediterranean Commodities. In Cultures of Commodity Branding; Bevan, A., Wengrow, D., Eds.; Left Coast Press: Walnut Creek, CA, 2010; pp 35–85.

- Gale, N. H.; Copper Oxhide Ingots and Lead Isotope Provenancing. In Metallurgy: Understanding How, Learning Why. Studies in Honour of James D. Muhly; Betancourt, P. P., Ferrence, S. C., Eds.; INSTAP Academic Press: Philadelphia, PE, 2011; pp 213–220.

- Gale, N. H.; Stos-Gale, Z. A. The Role of the Apliki Mine Region in the Post C. 1400 BC Copper Production and Trade Networks in Cyprus and in the Wider Mediterranean. In In Eastern Mediterranean Metallurgy and Metalwork in the Second Millennium BC; Kassianidou, V., Papasavvas, G., Eds.; Oxbow Books: Oxford, 2012; pp 70–82.

- Kassianidou, V.; Oxhide Ingots in Cyprus. In The Oxhide Ingots in the Central Mediterranean; Lo Schiavo, F., Muhly, J. D., Maddin, R., Giumlia-Mair, A., Eds.; ICEVO-CNR: Rome, 2009; pp 41–82.

- Papasavvas, G.; The Iconography of the Oxhide Ingots. In The Oxhide Ingots in the Central Mediterranean; Lo Schiavo, F., Muhly, J. D., Maddin, R., Giumlia-Mair, A., Eds.; ICEVO-CNR: Rome, 2009; pp 83–117.

- Montero, I.; Valera, P.; Manunza, M. R.; Lo Schiavo, F.; Rafel, N.; Villaça, R.; Sureda, P. Funtana Coberta Hoard; New Copper Provenance in the Nuragic Metallurgy. In In Bronze Age Metallurgy in the Mediterranean Islands, in Honour of Robert Maddin and Vassos Karageorghis; Giumlia-Mair, A. F., Lo Schiavo,, Eds.; Éditions Mergoil: Drémil-Lafage, 2018; pp 137–164.

- Kassianidou, V.; Copper Oxhide Ingots and Cyprus – The Story so Far. Numismatic Rep. 2012, XXXIL-XLIII, 9–54.

- Lo Schiavo, F.; The Oxhide Ingots in Nuragic Sardinia. In The Oxhide Ingots in the Central Mediterranean; Lo Schiavo, F., Muhly, J. D., Maddin, R., Giumlia-Mair, A., Eds.; ICEVO-CNR: Rome, 2009; pp 225–407.

- Lo Schiavo, F.; Cyprus and Sardinia, beyond the Oxhide Ingots. In Eastern Mediterranean Metallurgy and Metalwork in the Second Millennium BC. A Conference in Honour of James D. Muhly, Nicosia 10th-11th October 2009; Kassianidou, V., Papasavvas, G., Eds.; Oxbow books: Oxford, 2012; pp 142–150.