Abstract

To describe temporal trends in treatment among older adult (≥66 years) patients diagnosed with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), we analyzed 18,058 DLBCL patients from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results linked Medicare (SEER-Medicare) database diagnosed between 2001 and 2013. Among 65% of patients receiving treatment after diagnosis, R-CHOP (Rituximab, Cyclophosphamide, Doxorubicin, Vincristine, Prednisone) was the most common frontline therapy, increasing with more recent treatment year: 51% (2001–2003) vs. 69% (2010–2014). Autologous and allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) was uncommon in these Medicare patients. As the addition of rituximab increased over time, we also observed an improved survival rate over time. It is possible there is an association, but we cannot make this inference as effectiveness was not measured in this study. Overall survival estimates indicated that survival probabilities steadily improved in more recent years; however, 5-year survival was <40%, indicating the need for improved treatment options for older adult DLBCL patients.

Introduction

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is an aggressive neoplasm of large B cells with a diffuse growth pattern and accounts for ∼30% of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) cases [Citation1,Citation2]. Incidence increases with age; the annual incidence rate is about 7.0 per 100,000 persons, with ∼20,000 new cases in the US annually [Citation3,Citation4]. DLBCL is primarily a disease of older adults, with median age at diagnosis of 65–70 years old [Citation1,Citation3,Citation5–7]. About two-thirds of patients present with advanced stage disease that is fatal if untreated [Citation1].

The most common and effective treatment regimen recommended for DLBCL patients across all disease stages is the chemoimmunotherapy R-CHOP (Rituximab + Cyclophosphamide, Doxorubicin, Vincristine, and Prednisone) [Citation8]. Historically, CHOP was the standard initial therapy for DLBCL; however, over the last couple decades, the addition of rituximab has shown significant improvements in survival and response rates, and therefore R-CHOP has evolved as the standard frontline therapy in this patient population [Citation9]. In clinical trials, ∼77% of older adult patients achieved a complete response with R-CHOP; however, 20–50% of patients relapsed within 5 years [Citation10–12]. The median age of patients in these trials was 69 years (range: 60–92). R-CHOP significantly improved 5-year overall survival compared with CHOP alone in older adult DLBCL patients (58% vs. 45%) [Citation11]. Despite the improved overall survival with R-CHOP, retrospective studies monitoring older adult DLBCL patients diagnosed between 2000 and 2007 [Citation13], and 2002 and 2009 [Citation14] have shown that older adult patients are less likely to receive this more aggressive treatment strategy.

As the projected population of adults aged ≥65 years in the US is predicted to expand from 50 million to 83 million in the next 25 years, the number of older adult patients diagnosed with DLBCL will expand [Citation15]. To better understand gaps in patient care and identify areas to improve outcomes for these patients, population-based studies are needed to assess treatment patterns for older adult DLBCL patients in the real-world setting and define the impact of these treatments on survival. To address this need, we undertook a retrospective cohort study of 18,058 newly-diagnosed DLBCL patients aged 66 years and older from 2001–2013 in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results linked Medicare (SEER-Medicare) database to describe temporal trends in treatment patterns (immunotherapy, chemotherapy, autologous and allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation [HSCT]) and changes over time in survival.

Materials and methods

Data source

This observational, retrospective cohort study included adult patients aged ≥66 years newly-diagnosed with DLBCL between 1 January 2001 and 31 December 2013 in the SEER database and with continuous enrollment in Medicare parts A and B for at least one year prior to diagnosis. SEER is a cancer registry with 18 locations representing ∼35% of the US population [Citation16]; SEER collects clinical, demographic, and cause of death information on individuals with cancer. Medicare is health insurance for predominantly 65+ aged adults; patients aged ≥66 years were examined for this study to account for the 1-year lookback. Patients were required to have 365 days of continuous enrollment prior to the index DLBCL diagnosis to capture this baseline information. Overall survival and treatment outcomes (most common treatment regimens at each line of therapy, number of treatment lines, duration of treatment regimen, and receipt of autologous or allogeneic HSCT after DLBCL diagnosis) were derived from Medicare claims from the date of DLBCL diagnosis (index date) through the date of death (as identified using the MEDPAR Beneficiary Death Date [Citation17]), end of enrollment, or 31 December 2014, whichever came first.

Study design and population

The study cohort was defined by the inclusion and exclusion criteria illustrated in Supplementary Appendix Figure A. Newly-diagnosed DLBCL patients were identified using SEER site recodes 33041 or 33042 for Non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and first malignant primary indicator of histology/behavior International Classification of Diseases for Oncology (ICD-O)-3 codes 9680/3 (malignant lymphoma (ML), large B-cell, diffuse) or 9684/3 (ML, large B-cell, diffuse, immunoblastic, not otherwise specified [NOS]). Only patients with a follow-up of at least 3 months (continuous enrollment) post-index date were included, with the exception of early death. Patients who were diagnosed with DLBCL on the date of their death were excluded. To ensure that patients analyzed had all medical claims accounted for through Medicare, patients were excluded from analysis if they had health maintenance organization (HMO) insurance any time within 12 months prior to index date through the end of follow-up. All personal identifying information was unavailable in the database. All figures and tables were reviewed and approved by the National Cancer Institute/Information Management Services, Inc. (IMS) to comply with the SEER-Medicare data usage agreement.

Measures

Demographics (age, sex, race, geographic region, year of index date) were described using available information from the SEER-Medicare database and categorized into four age groups (66–70, 71–75, 76–80, ≥81 years) and by year of diagnosis (2001–2003, 2004–2006, 2007–2009, 2010–2013). Comorbidities during the baseline period (defined as the period 12 months prior to the initial diagnosis of DLBCL) were assessed using the Quan-adapted Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) and categorized into three groups (0, 1–2, ≥3) [Citation18–21]. Weights were assigned to disease states as described in the Supplementary Methods of the Appendix. Conditions and codes used to calculate the CCI are provided in Supplementary Appendix Table A.

Treatment was identified by a Medicare claim with a relevant billing code (Supplementary Appendix Table B) and described by type of regimen (R-CHOP-based, CHOP-based, rituximab only, rituximab + other, and other), line of therapy, and duration of regimen. The first line of therapy was identified as the first instance of chemotherapy or other relevant treatment. Each line of therapy was defined by a specified segment length of 56 days. A new treatment line was indicated at the end of a segment length if at least one new medication was introduced from the previous segment to the next (i.e. consecutive segments with no new medications were considered one line and periods with no treatment were not included). Refer to Supplementary Appendix Figure B. A small sample of charts were reviewed for each candidate segment length of 28, 30, 56, and 60 days. The 56-day implementation was found to be most reliable. No formal statistics were reported for this assessment. We set the allowed gap in treatment before a patient was considered off a treatment to be four weeks (28 days), and the segment length was set to double this length. Therefore, if a patient did not have any treatment during a defined 56-day segment, the patient would be considered off treatment. Treatment regimens identified in the analysis were those identified in the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines for the management of adult patients with DLBCL [Citation8]. Other chemotherapy regimens outside of these guidelines were classified as ‘other chemotherapy.’ Treatment lines that included all R-CHOP elements were classified as R-CHOP-based; lines containing all CHOP elements were considered CHOP-based; lines of therapy that included rituximab and any other agent that did not include all CHOP elements were classified as rituximab + other; and all other regimens that did not include rituximab or sum to CHOP were included in the other category. Since oral steroids (e.g. prednisone, dexamethasone) are not commonly billed in the Medicare Durable Medical Equipment file, their presence was assumed when other CHOP elements or other common regimen elements were identified. HSCT, including autologous and allogeneic transplantations, was identified by at least one Medicare claim with a relevant code after index date until the end of follow-up, based on identification algorithms from the literature and medical reimbursement documentation [Citation22,Citation23] (Supplementary Appendix Table C).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were described as total patient counts and percentages, and grouped into a full cohort, and by receipt of chemotherapy and/or immunotherapy. Overall survival probabilities were estimated from the Kaplan–Meier estimators used to create the curves. Kaplan–Meier OS probabilities were described at selected times following DLBCL diagnosis by baseline characteristics (6 months, 1 year, 18 months, 2 years, 3 years, 5 years) and the median OS was estimated. Temporal trends in treatment patterns were described by looking at regimens at each line of therapy, stratified by year of treatment initiation. Survival was described by age, comorbidity burden, year of diagnosis and stage. The Boston Health Economics’ Instant Health Data (IHD) tool was used for data analysis.

Results

Patient characteristics

The study cohort included 18,058 patients aged ≥66 years newly-diagnosed with DLBCL between 1 January 2001 and 31 December 2013, in the SEER-Medicare database. The median age at DLBCL diagnosis was 78 years, with 19% of patients aged 66–70 years, 22% aged 71–75 years, 23% aged 76–80 years, and 36% aged ≥81 years (). There were slightly more females than males (53% vs. 47%), and 88% of patients with non-missing race were Caucasian, 4% Asian, 4% Black, and 2% Hispanic. For the full study cohort, 65% of patients received a treatment regimen of chemotherapy and/or rituximab after diagnosis of DLBCL (). Of the 35% of patients that did not receive chemotherapy and/or rituximab, 50% were >80 years old at DLBCL diagnosis.

Table 1. Descriptive characteristics of the study population by treatment status (N = 18,058).

Temporal changes in treatment patterns

Among the 65% of patients who received treatment after the diagnosis of DLBCL, R-CHOP was the most common first line of therapy, followed by rituximab in combination with other chemotherapy agents, and rituximab monotherapy (). Over time, the use of R-CHOP as the first line of therapy expanded from 51% for the patient cohort treated from 2001–2003 to 69% for the patient cohort treated from 2010–2014, whereas the use of CHOP without rituximab as the first line of therapy diminished (). Rituximab use in general as part of frontline therapy rose from 74% of therapies in 2001–2003 to 93%–94% of those initiating treatment from 2004 and later (). The use of HSCT was uncommon in this patient population (N = 234; 1.3%). Patients >80 years old at diagnosis were less likely to receive R-CHOP for the first line of therapy compared with patients aged 66–80 years (>80: 46.5% vs. age 66–70: 75.2%, age 71–75: 72.7%, age 76–80: 65.4%) (). Patients over 80 were more likely to receive rituximab in combination with other chemotherapy agents or rituximab monotherapy as the first line of therapy compared with younger patients (% rituximab + other, % rituximab monotherapy: >80: 26.7%, 16.0% vs. age 66–70: 10.5%, 3.5%, age 71–75: 13.9%, 4.0%, age 76–80: 18.3%, 6.0%) (). However, rituximab in combination with CHOP or other chemotherapy agents increased in more recent years among the oldest age group, while rituximab monotherapy became less common (). Additionally, the proportion of treated patients over 80 increased slightly over time from 49% in the cohort diagnosed from 2001–2003 to 54% in the 2010–2013 cohort (data not shown).

Table 2. Top regimens of all treated DLBCL patients at each line of therapy by treatment initiation year.

Table 3. Top regimens of all treated DLBCL patients at each line of therapy by age group at diagnosis.

Table 4. First line of therapy by treatment initiation year for patients aged ≥81 years.

Temporal changes in overall survival

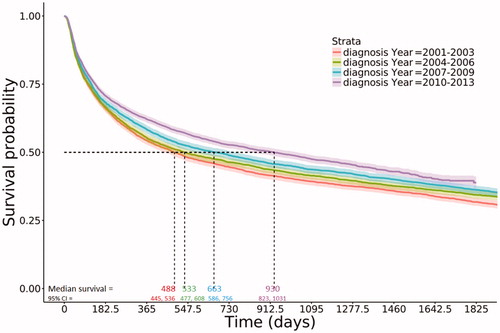

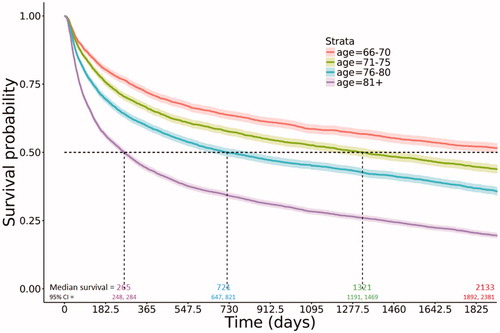

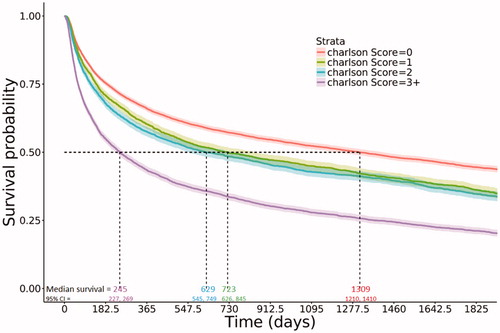

More recently diagnosed DLBCL patients had improved median overall survival. Estimated median survival of patients diagnosed in the most recent years (2010–2013) was nearly twice the estimated median survival of patients diagnosed in the earliest years (2001–2003; 930 days [∼2.5 years] vs. 488 days [∼1.3 years]; ). At 5 years post-diagnosis, estimated survival probabilities and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) by year of diagnosis were 0.32 (0.30, 0.33) for the 2001–2003 cohort, 0.34 (0.33, 0.36) for the 2004–2006 cohort, 0.36 (0.35, 0.38) for the 2007–2009 cohort, and 0.39 (0.37, 0.41) for the 2010–2013 cohort (). The youngest age group (66–70 years) had an estimated median survival of 2133 days (5.8 years); compared to 265 days (<1 year) in the oldest group (). Patients with less comorbidity burden had improved overall survival; with estimated median survival of 1309 days (∼3.6 years) in those with no comorbidities versus 245 days in those with a CCI of 3 or higher, and similar rates in those with a 1 or 2 CCI (median survival: ∼2 years and ∼1.7 years, respectively; ). Similarly, improvement in median overall survival was observed stratified by stage (data not shown).

Table 5. Estimated probability of survival over time by year of DLBCL diagnosis (estimate [95% confidence interval]).

Discussion

To improve outcomes for the expanding older adult DLBCL patient population, population-based studies are needed to assess treatment patterns and survival for older adult DLBCL patients in the real-world setting. We addressed this need by conducting a retrospective cohort study of 18,058 newly-diagnosed DLBCL patients aged ≥66 years from 2001 until 2013 in the SEER-Medicare database to describe patient characteristics, temporal trends in treatment patterns, and overall survival. From 2001 to 2014, the use of CHOP as a first line of therapy without rituximab nearly diminished, being replaced by the chemoimmunotherapy R-CHOP. Estimated 5-year overall survival probabilities steadily improved for older adult DLBCL patients from 0.32 for patients diagnosed from 2001 to 2003, to 0.39 for those diagnosed from 2010 to 2013. This highlights that modest improvements in survival have been achieved in this patient population over the past decade.

Previous studies have highlighted the benefit of more aggressive treatment strategies, such as R-CHOP, and improved survival in younger and older adult patients alike [Citation13,Citation14,Citation24–26]. Williams et al., in their retrospective study of 4635 older adult DLBCL patients diagnosed between 2002 and 2009, showed that patients over 80 years old were less likely to receive R-CHOP versus patients aged 66–80 years (52% vs. 74%), yet this regimen conferred improved median overall survival [Citation14]. In their retrospective study of 9333 older adult DLBCL patients diagnosed between 2000 and 2007, Hamlin et al. likewise showed that patients aged ≥81 years were less likely to receive R-CHOP compared to patients aged 66–80 years (36% vs. 55%) [Citation13]. Herein, in our study examining 18,058 newly-diagnosed DLBCL patients aged ≥66 years from 2001–2014, we showed that R-CHOP usage for patients aged ≥81 years became increasingly more common (2001–2003: 33.5%; 2004–2006: 47.3%; 2007–2009: 48.9%; 2010–2014: 51.5%) (). Despite this temporal increase in R-CHOP usage by patients aged 81 and older, these patients were still less likely to receive R-CHOP as a first line of therapy compared with the younger cohort despite the improved median overall survival of this chemoimmunotherapy (>80: 46.5% vs. age 66–70: 75.2%, age 71–75: 72.7%, age 76–80: 65.4%) (). While R-CHOP usage increased and is the most commonly used regimen amongst patients aged >80 at diagnosis, this aggressive treatment may not be tolerable. Other regimens including rituximab plus other chemotherapy (e.g. R-COP that excludes anthracycline doxorubicin and is less toxic than R-CHOP) and rituximab monotherapy may be more tolerable for older adults. Patients aged >80 years at diagnosis were more likely to receive these less aggressive treatments as the first line of therapy compared with patients aged 66–80 years (). However, this study suggests that the older adult patient population >80 years have increasingly received chemotherapy and/or immunotherapy and more aggressive treatment over time (). We also examined the impact of age and comorbidity on overall survival. Not surprisingly, patients with advancing age and multiple comorbidities had inferior survival outcomes, but these factors may have also affected treatment assignment [Citation27].

Retrospective studies by the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR) and the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (ESBMT) Lymphoma Working Party have shown that DLBCL patients who undergo HSCT have a long-term overall survival of 35–40% [Citation28–30]. Despite the potential of HSCT to increase survival of patients, the overall proportion of patients who underwent transplantation was only 1.3%. This may be due to the fact that transplantation is an aggressive therapeutic option not suitable for all patients and highlights the need for additional treatment options.

The strengths of this retrospective cohort study are the large sample size and recent data that are advantageous in describing temporal changes in treatment strategies and overall survival of DLBCL patients. Since this study is based on SEER-Medicare data, it has some inherent limitations. First, only patients 66 years of age and older are represented. This older population may have different performance status, comorbidities, and treatment regimens than younger DLBCL patients. Second, due to limitations with the database, we could not ascertain the response status to therapy of patients. Additionally, the line algorithm could not be used as a surrogate for progression-free survival. The fixed segment length of 56 days that was used to define a line of therapy is another limitation. Patients who received chemotherapy or immunotherapy for less than this fixed length were not included in the defined treatment sequences. Additionally, since patients that disenrolled within 3 months of diagnosis without having observed death are excluded from the analysis, this likely introduces some bias to the survival estimates by decreasing estimated survival. Thus, survival estimates may be slightly underestimated. Finally, Medicare data do not include claims for HMO enrollees, care provided in other settings, reimbursement for covered services not captured by the Medicare data, coverage provided by Medigap policies, and other services not covered by Medicare (e.g. long term care at home or a nursing home and routine physicals). Despite these limitations, this study defines temporal changes in treatment patterns and reflects the real-world use and clinical approach for management of DLBCL in the older adult US population.

These data provide insight into current treatment strategies of DLBCL and changes that have occurred over time. Overall survival estimates indicate that survival rates have steadily improved in more recent years; however, 5-year survival remains less than 40%. To improve outcomes for older adult DLBCL patients, more effective and tolerable therapeutic options are needed.

Author contributions

All authors participated in data interpretation and drafting of the manuscript, and read, revised and approved the final manuscript.

Potential conflict of interest

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this article online at http:\\<10.1080/10428194.2019.1623886>

Appendix

Download MS Word (215 KB)Acknowledgments

This study used the linked SEER-Medicare database. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the sole responsibility of the authors. The authors acknowledge the efforts of the National Cancer Institute; the Office of Research, Development and Information, CMS; Information Management Services (IMS), Inc.; and the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program tumor registries in the creation of the SEER-Medicare database. The authors acknowledge Elizabeth Leight of Leight Medical Communications, LLC (St. Charles, MO), whose work was supported by Amgen Inc., for providing medical writing support.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ng AK. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2007;17:169–175.

- Martelli M, Ferreri AJ, Agostinelli C, et al. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Crit Rev Oncol/Hematol. 2013;87:146–171.

- Howlader NN, Krapcho M, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2014, National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD; 2017. [cited 2019 May 28]. Available from: https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2014/, Table 19.26: All Lymphoid Neoplasms with Detailed Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Subtypes; SEER Incidence Rates and Annual Percent Change by Age at Diagnosis, All Races, Both Sexes, 2005 – 2014.

- Freedman AS, Aster JC [Internet]. Epidemiology, clinical manifestations, pathologic features, and diagnosis of diffuse large B cell lymphoma. UptoDate. [cited 2019 Jan 1]. Available from: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/epidemiology-clinical-manifestations-pathologic-features-and-diagnosis-of-diffuse-large-b-cell-lymphoma.

- Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, et al. Cancer statistics, 2006. CA: Cancer J Clin. 2006;56(2):106–130.

- Ries L, Harkins D, Krapcho M, et al. SEER cancer statistics review,1975 to 2003. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2006.

- Smith A, Howell D, Patmore R, et al. Incidence of haematological malignancy by sub-type: a report from the Haematological Malignancy Research Network. Br J Cancer. 2011;105:1684–1692.

- NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Non-Hodgkin's Lymphomas Version3.2016 [Internet]. 2016. [cited 2019 Jan 1]. Available from: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/b-cell.pdf

- Morrison VA. Evolution of R-CHOP therapy for older patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2008;8:1651–1658.

- Coiffier B, Lepage E, Briere J, et al. CHOP chemotherapy plus rituximab compared with CHOP alone in elderly patients with diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:235–242.

- Feugier P, Van Hoof A, Sebban C, et al. Long-term results of the R-CHOP study in the treatment of elderly patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a study by the Groupe d'Etude des Lymphomes de l'Adulte. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:4117–4126.

- Habermann TM, Weller EA, Morrison VA, et al. Rituximab-CHOP versus CHOP alone or with maintenance rituximab in older patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3121–3127.

- Hamlin PA, Satram-Hoang S, Reyes C, et al. Treatment patterns and comparative effectiveness in elderly diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients: a surveillance, epidemiology, and end results-medicare analysis. Oncologist. 2014;19:1249–1257.

- Williams JN, Rai A, Lipscomb J, et al. Disease characteristics, patterns of care, and survival in very elderly patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Cancer. 2015;121:1800–1808.

- Vincent GK, Velkoff VA. The Next Four Decades: The Older Population in the United States: 2010 to 2050. Population Estimates and Predictions. [cited 2018 Oct 19]. Available from: census.gov/prod/2010pubs/p25-1138.pdf

- Overview of the SEER Program. Available from: https://seer.cancer.gov/about/overview.html [cited 2019 May 10].

- Documentation for MEDPAR files. [cited 2019 May 28]. Available from: https://healthcaredelivery.cancer.gov/seermedicare/medicare/MEDPAR.pdf2018

- Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care. 2005;43:1130–1139.

- Quan H, Li B, Couris CM, et al. Updating and validating the Charlson comorbidity index and score for risk adjustment in hospital discharge abstracts using data from 6 countries. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173:676–682.

- Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383.

- Khan NF, Perera R, Harper S, et al. Adaptation and validation of the Charlson Index for Read/OXMIS coded databases. BMC Fam Pract. 2010;11:1.

- Broder MS, Quock TP, Chang E, et al. The cost of hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation in the United States. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2017;10:366–374.

- LeMaistre CF, Farnia S, Crawford S, et al. Standardization of terminology for episodes of hematopoietic stem cell patient transplant care. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2013;19:851–857.

- Boslooper K, Kibbelaar R, Storm H, et al. Treatment with rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisolone is beneficial but toxic in very elderly patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a population-based cohort study on treatment, toxicity and outcome. Leukemia Lymphoma. 2014;55:526–532.

- Hasselblom S, Stenson M, Werlenius O, et al. Improved outcome for very elderly patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in the immunochemotherapy era. Leukemia Lymphoma. 2012;53:394–399.

- Varga C, Holcroft C, Kezouh A, et al. Comparison of outcomes among patients aged 80 and over and younger patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a population based study. Leukemia Lymphoma. 2014;55:533–537.

- Lin TL, Kuo MC, Shih LY, et al. The impact of age, Charlson comorbidity index, and performance status on treatment of elderly patients with diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Ann Hematol. 2012;91:1383–1391.

- Fenske TS, Hamadani M, Cohen JB, et al. Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation as curative therapy for patients with non-hodgkin lymphoma: increasingly successful application to older patients. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2016;22:1543–1551.

- Fenske TS, Ahn KW, Graff TM, et al. Allogeneic transplantation provides durable remission in a subset of DLBCL patients relapsing after autologous transplantation. Br J Haematol. 2016;174:235–248.

- Kyriakou C, Boumendil A, Finel H, et al. The impact of advanced patient age on mortality after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for non-hodgkin lymphoma: a retrospective study by the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation Lymphoma Working Party. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2018;25:86–93.