Abstract

Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) can inform treatment selection and assess treatment value in acute myeloid leukemia (AML). We evaluated PROs from the ADMIRAL trial (NCT02421939) in patients with FLT3-mutated relapsed/refractory (R/R) AML. PRO instruments consisted of Brief Fatigue Inventory (BFI), Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Leukemia (FACT-Leu), Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Dyspnea Short Form (FACIT-Dys SF), EuroQoL 5-Dimension 5-Level (EQ-5D-5L), and leukemia treatment-specific symptom questionnaires. Clinically significant effects on fatigue were observed with gilteritinib during the first two treatment cycles. Shorter survival was associated with clinically significant worsening of BFI, FACT-Leu, FACIT-Dys SF, and EQ-5D-5L measures. Transplantation and transfusion independence in gilteritinib-arm patients were also associated with maintenance or improvement in PROs. Health-related quality of life remained stable in the gilteritinib arm. Hospitalization had a small but significant effect on patient-reported fatigue. Gilteritinib was associated with a favorable effect on fatigue and other PROs in patients with FLT3-mutated R/R AML.

Introduction

The substantive burden of illness and economic burden of chemotherapy in patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) have wide-ranging impacts on their well-being and health-related quality of life (HRQoL) [Citation1–3]. Conventional treatment for AML involves up to two cycles of induction chemotherapy to achieve remission [Citation4,Citation5]. If remission is not achieved or if a relapse occurs after remission, treatment guidelines recommend salvage chemotherapy (SC), targeted therapy, or best supportive care [Citation4,Citation5].

Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) play an essential role in therapy evaluation [Citation6,Citation7] and bridge the gap between patients’ and clinicians’ views of patient health status and treatment success [Citation8]. Specifically, PROs are used to evaluate symptom burden, treatment side effects, physical fitness, and treatment tolerability [Citation9]; they can also assess the patient’s sense of well-being across multiple domains [Citation9]. Systematic PRO collection and evaluation improves communication between patients and their physicians, and enables better symptom management [Citation8]. Routine PRO evaluation in patients with advanced disease may reduce hospitalizations and prolong survival [Citation8] by allowing early identification of general health- and disease-related conditions that negatively affect health and well-being. In AML, fatigue and transfusion dependence have major detrimental effects on HRQoL [Citation2,Citation10–12]. Implementation of PROs in oncology practice is a key priority of the American Society of Clinical Oncology [Citation13]. The American Society of Hematology has initiated an observational registry-based study of 20,000 patients with hematologic disorders, with PROs related to HRQoL as key outcome measures [Citation14].

Patients with relapsed/refractory (R/R) AML have a poor prognosis and are unlikely to respond to SC [Citation15]. Activating mutations in fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3) confer a poor prognosis [Citation16–18]. The emergence of FLT3-targeted therapies has expanded treatment options for AML. Assessment of the impact of FLT3-targeted therapies on PROs may further support use of these agents in AML [Citation19]. Gilteritinib is a FLT3 inhibitor approved for patients with R/R FLT3-mutated (FLT3mut+) AML [Citation20,Citation21]. The phase 3 randomized ADMIRAL trial (NCT02421939) demonstrated the superiority of single-agent gilteritinib vs. SC in this population [Citation22]. Median overall survival (OS) was longer in the gilteritinib arm (9.3 months) than the SC arm (5.6 months; hazard ratio (HR) for death = 0.64; p< .001). Rates of complete remission (CR) or CR with partial hematologic recovery (CRh) were 34% and 15% in the gilteritinib and SC arms, respectively; rates of composite CR (defined as CR with or without complete hematologic or platelet recovery) were 54% and 22%, respectively [Citation22]. The ADMIRAL trial included evaluation of PROs, selected on the basis of results of patient interviews [Citation10,Citation23].

At the time of the primary analysis of ADMIRAL, evaluation of PRO data was still ongoing and therefore not included in the primary publication. Here, we describe PROs and their relationship to survival, transfusion status, transplant status, and hospitalization in ADMIRAL study patients with FLT3mut+ R/R AML.

Methods

Study design and patient population

ADMIRAL was a phase 3, open-label, multicenter, randomized study that compared the efficacy and safety of gilteritinib vs. SC in patients with FLT3mut+ R/R AML (Figure S1) [Citation22]. Briefly, patients aged ≥18 years with AML with a confirmed FLT3-ITD or FLT3-TKD (D835 or I836) mutation, who were refractory to one or two cycles of conventional anthracycline-containing induction therapy or ≥1 cycle of alternative standard therapy or had relapsed after CR, were included. Treatment with gilteritinib or SC was administered in continuous 28-day cycles. High-intensity SC was administered for up to two cycles; gilteritinib or low-intensity SC was administered until disease progression or intolerance.

Co-primary endpoints were OS and rate of CR/CRh [Citation22]. Patient-reported fatigue was a secondary endpoint; patient-reported dyspnea, leukemia-specific symptoms, HRQoL, and healthcare resource utilization (i.e. hospitalization, blood transfusions, and medication use) were exploratory endpoints.

PRO measures and assessment schedule

A conceptual model was developed and used to conduct interviews of adult patients with AML. During the interviews, patients rated the level of disturbance of their symptoms and associated impacts, which enabled the identification of salient symptoms and impacts (Supplemental Material: page 1, Figure S2) [Citation23]. Salient symptoms were nausea, vomiting, anemia, pain, fatigue, weakness, shortness of breath, fever, infection, mouth sores, and vision problems [Citation23]; salient impacts included anxiety, depression, fear, worry about remission, and decreased ability to maintain social/familial roles [Citation23]. These symptoms and impacts were consistent with those previously reported [Citation10], and informed the selection of the following PRO instruments: Brief Fatigue Inventory (BFI), Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Leukemia (FACT-Leu), Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Dyspnea (FACIT-Dys), EuroQoL 5-Dimension 5-Level (EQ-5D-5L), and leukemia-specific symptoms (dizziness and mouth sores) [Citation24–27]. The BFI is a nine-item questionnaire comprised of a total score and two sub-scores that assess fatigue severity across three items, and interference caused by fatigue across six items [Citation27]. The BFI total score is the arithmetic mean of all nine BFI item scores, with higher scores reflecting greater levels of fatigue [Citation27]. The FACT-Leu Questionnaire, designed to assess HRQoL in patients with leukemia, is comprised of five subscale scores (physical well-being [PWB], social/family well-being [SWB], emotional well-being [EWB], functional well-being [FWB], and leukemia subscale), a total score, and two aggregate summary scores: (general and trial outcome index [TOI]) [Citation28]. The leukemia subscale has 27 items (17 physical symptoms and 10 disease/treatment-related emotional/social concerns), each rated on a five-point Likert subscale [Citation24]. Higher FACT-Leu scores reflect better HRQoL.

The FACIT-Dys/PROMIS® Dyspnea Questionnaire evaluates patient-reported severity of, and functional limitations due to, dyspnea [Citation29]. The dyspnea subscale rates the level of dyspnea experienced while completing 10 common daily tasks. The functional limitation subscale rates the level of difficulty associated with completing these tasks [Citation26]. Scoring was performed according to PROMIS® Dyspnea scoring manual guidelines [Citation29].

The EQ-5D-5L Questionnaire covers five dimensions (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression) of HRQoL, each with five levels of inquiry, which are reported on a Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) [Citation25,Citation30]. The EQ-5D-5L utility index represents a derived summary score based on assigned values for each level within each dimension [Citation30]; the EQ-5D-5L value set for England was used in this analysis [Citation31]. Only EQ-5D-5L VAS scores are reported here. Leukemia-specific symptoms of dizziness and mouth sores were identified as salient symptoms not captured by other PRO instruments. These symptoms were scored similarly to symptoms in the FACT-Leu leukemia subscale, where severity of dizziness and mouth sores were rated on a five-point Likert scale. No cognitive debriefing or psychometric validation was performed for these items.

All PROs were assessed at baseline (pre-dose on day 1 of cycle 1), day 1 of every treatment cycle, and at the end-of-treatment (EOT) visit (≤7 days after treatment discontinuation); BFI-based evaluations of fatigue were also performed on days 8 and 15 of cycle 1, and days 1 and 15 of cycle 2. For all PRO instruments, the completion rate at each study visit was calculated as the number of patients returning evaluable forms divided by the total number of patients expected to complete the PRO assessment at the study visit.

Post-baseline item scores and domain scores were classified as ‘improvement,’ ‘no change,’ or ‘deterioration’ relative to baseline scores at each cycle according to the change threshold, which was based on published values denoting clinically meaningful change or on a distribution-based method in the absence of a published value (Table S1). Clinically meaningful change thresholds for FACT-Leu subscales used in ADMIRAL were consistent with those used in studies of AML or chronic myeloid leukemia [Citation32,Citation33] (further details in Supplemental Material).

Assessment of PROs relative to survival outcomes, transplant, and transfusion status

The association between PRO measures and survival outcomes (i.e. OS and event-free survival [EFS]) was evaluated based on the HR for the PRO variable and was calculated as the HR for death per X-point change in the PRO score, with X corresponding to the threshold value denoting a clinically meaningful change (Table S1). PROs were evaluated in gilteritinib-treated patients who underwent and did not undergo hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), and in patients who became or did not become transfusion independent (TI) during the study. As patients who received high-intensity SC received no more than two treatment cycles, PRO comparisons between treatment arms are not presented here.

Assessment of transfusion status and hospitalization

Patients were considered TI at baseline if no red blood cell (RBC) or platelet transfusions were administered within the baseline period (i.e. 28 days before to 28 days after the first dose). Post-baseline TI was defined as no RBC/platelet transfusions during one consecutive 8-week period from the first 29 days after the first dose of gilteritinib until the last dose date. For patients on treatment for >4 weeks but <12 weeks with no RBC/platelet transfusions within the post-baseline period, post-baseline transfusion status was considered unevaluable.

The duration of hospital stay, type of hospitalization (any or intensive care unit [ICU]), and reason for hospitalization were assessed. Data related to hospitalization were collected on day 1 of each treatment cycle and at EOT. Patients hospitalized multiple times were counted once for each type of hospitalization; patients hospitalized multiple times for the same reason were only counted once for that reason. The immediate impact of hospitalization on BFI, Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Dyspnea Short Form (FACIT-Dys SF), FACT-Leu, and EQ-5D-5L scores was assessed in the gilteritinib arm.

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses of PRO data were performed on the intention-to-treat (ITT) population (defined as all patients who were randomly assigned to treatment), all of whom provided PRO data at baseline. Domain and item scores for each PRO instrument were summarized using descriptive statistics. Responder and association analyses were also conducted in patients with non-missing data to determine the proportions of patients with clinically meaningful improvement, no change, or deterioration in PRO scores relative to baseline using prespecified threshold values (Table S1). A modified EOT (mEOT) assessment was established and defined as either the EOT assessment, which occurred within seven days of the last PRO assessment if the patient discontinued or died, or as the last PRO assessment before the data cutoff date for patients still on study treatment. The relationship of PROs to survival outcomes was analyzed in the overall ITT population and the gilteritinib arm; the relationship of PROs to transfusion status, transplantation, and healthcare resource utilization was evaluated only in the gilteritinib arm. Per protocol, patients in the SC arm who received high-intensity chemotherapy received no more than two treatment cycles, resulting in relatively few patients who could provide completed PRO questionnaires beyond cycle 2. As such, time points up to cycle 2 were selected for evaluation of improvement, stability, or deterioration of all PRO items and domain scores relative to baseline in each treatment arm.

Longitudinal change from baseline to cycle 2 in BFI domain scores was analyzed using a mixed model repeated measures (MMRM)-based approach using the following baseline covariates: baseline BFI score, preselected SC, and response to first-line AML therapy. The MMRM approach accounts for missing-at-random data that are consistent with the ITT principle [Citation34].

The association between longitudinal PRO changes and survival outcomes was evaluated using a time-dependent Cox regression model. The Cox regression model also included treatment effects and stratification factors at randomization (i.e. response to first-line therapy and preselected SC). To minimize instability of the final multivariate model, potentially resulting from high multicollinearity, separate models were fit for each PRO domain. A multivariate analysis to assess associations between survival outcomes, with adjustment for baseline prognostic factors, was also performed.

Two-sided nominal p values were estimated (significance testing set at .05) with no adjustments made for multiple comparisons. Descriptive statistics were used to evaluate both continuous and categorical data. Missing and invalid observations were tabulated as a separate category and were excluded from calculations of proportion.

Linear mixed-effects models were used to model each patient’s longitudinal trajectory of PROs before the first hospitalization and to estimate the extent to which the post-hospitalization PRO value deviated from that trajectory [Citation35,Citation36]. All models included fixed effects for time (in days) and a hospitalization indicator variable denoting the post-hospitalization data point for each patient. We estimated random intercepts and slopes for time to allow for inter-patient variation in growth curves. The trajectory-adjusted mean change (TAMC) was defined as the mean deviation of the post-hospitalization value from the expected value based on patients’ pre-hospitalization trajectory (Figure S3); TAMC values were interpreted using established values for clinically meaningful changes in PROs (Table S1). Standard effect size was calculated by dividing the TAMC by the standard deviation at baseline. Effect sizes of 0.2, 0.5, and 0.8 were characterized as small, medium, and large, respectively, using Cohen’s benchmarks [Citation37], which corresponded to changes in post-hospitalization PROs that shifted the average patient in the trial from the 50th percentile to approximately 40th, 30th, and 20th percentiles, respectively. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Demographic and baseline characteristics

Of the 371 patients who comprised the ITT population, 247 were assigned to gilteritinib and 124 were assigned to SC. Overall, 246 of 247 patients assigned to gilteritinib and 109 of 124 patients assigned to SC received study therapy. Treatment arms were well balanced for demographic and baseline disease characteristics and prior therapies [Citation22]. More patients in both treatment arms completed PRO questionnaires at baseline than at later time points (Table S2). Due to treatment discontinuation, the number of patients who completed PRO questionnaires decreased substantially by cycle 6 in the gilteritinib arm and by cycle 2 in the SC arm. As a result, PRO data collection for patients receiving high-intensity SC did not extend beyond two cycles, with only 15 patients in the SC arm having PRO data at cycle 2.

Change in fatigue in gilteritinib and salvage chemotherapy arms

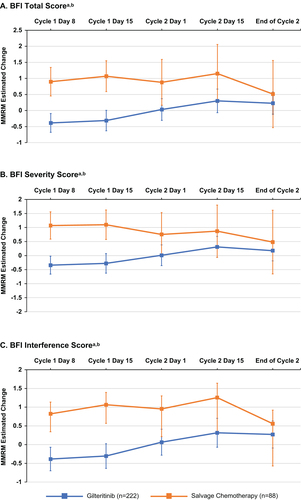

Baseline fatigue levels were relatively low, as evidenced by BFI total as well as BFI severity and interference scores, with a mean rating of 3.0 (0–10 rating scale) in both treatment arms (). Fatigue levels remained generally low in both treatment arms throughout the trial. Based on evaluable BFI questionnaires from 81.0% (n = 200/247) of patients in the gilteritinib arm and for 61.3% (n = 76/124) in the SC arm on day 8 of cycle 1, more patients in the gilteritinib arm than in the SC arm reported clinically meaningful improvement (≥3 points) in the BFI worst fatigue item rating (16.2% vs. 6.8%, respectively; Figure S4). This trend was also observed on day 15 (gilteritinib vs. SC: 24.4% vs. 6.8%, respectively) of cycle 1, based on evaluable BFI questionnaires in 83.4% (n = 206/247) of patients in the gilteritinib arm and 62.1% (n = 77/124) in the SC arm. Fewer patients in the gilteritinib arm than in the SC arm reported clinically meaningful deterioration (≥3 points) in the BFI severity item of worst fatigue on day 8 (11.7% vs. 27.4%, respectively) and day 15 (14.2% vs. 35.6%, respectively; Figure S4) of cycle 1. The longitudinal change in BFI scores based on MMRM estimates demonstrated that patients in the gilteritinib arm reported a minor change in BFI subscale scores between cycles 1 and 2 ().

Figure 1. Mean longitudinal change in fatigue in patients with FLT3mut+ R/R AML. MMRM estimated change from baseline in (A) BFI total score, (B) BFI severity score, and (C) BFI interference score. aData were missing for 41 patients in the gilteritinib arm and 109 patients in the SC arm at cycle 2 day 1. bError bars represent 95% CI. AML: acute myeloid leukemia; BFI: Brief Fatigue Inventory; MMRM: mixed model repeated measures; mut+: mutated; R/R: relapsed/refractory.

Table 1. PRO scores in patients with FLT3mut+ R/R AML treated with gilteritinib or salvage chemotherapy in the ADMIRAL study (ITT population).

Changes in HRQoL, leukemia-specific symptoms, and dyspnea in gilteritinib and salvage chemotherapy arms

Patients both in the gilteritinib and SC arms had similar mean (SD) FACT-Leu total scores (122.1 [26.08] and 118.5 [25.62], respectively) at baseline, indicating a mild overall impact of leukemia therapy (). FACT-Leu subscale scores (mean [SD]) in the gilteritinib arm were generally stable (gilteritinib: 47.6 [10.57], cycle 2 day 1: 47.9 [11.72], and showed a slight improvement by mEOT (45.2 [13.37]). The proportions of patients who had no change or improvement in FACT-Leu subscale scores were similar across treatment arms (Figure S5A).

Patients in both arms had similar mean (SD) dyspnea scores (7.4 [8.37] and 7.1 [8.46], respectively) at baseline, indicating mild shortness of breath; functional limitation scores at baseline were also similar in gilteritinib and SC arms (mean [SD]: 6.5 [7.99] and 5.9 [7.89], respectively), reflecting minimal functional impact of dyspnea (). The proportions of patients with no change or improvement in dyspnea or functional limitation scores at cycle 2 day 1 or mEOT were similar across both treatment arms (Figure S5B).

Patients entering the ADMIRAL trial had mild symptoms of dizziness (mean [SD]: gilteritinib, 0.4 [0.76]; SC, 0.5 [0.95]) and mouth sores (mean [SD]: gilteritinib, 0.3 [0.65]; SC, 0.3 [0.77]; ). Although more patients in the gilteritinib arm (50%) than in the SC arm (10%) reported an increase in dizziness at the mEOT assessment, most patients in both treatment arms reported no change in dizziness (62.9%) or mouth sores (73.3%) after two cycles of treatment (Figure S5C).

At baseline, mean (SD) EQ-5D-5L VAS values were 63.9 (24.56) and 62.9 (24.15) in gilteritinib and SC arms, respectively (). Overall, EQ-5D-5L VAS scores (mean [SD]) were stable during the first two treatment cycles across both treatment arms (cycle 2 day 1, gilteritinib vs. SC: 65.5 [22.7] vs. 67.2 [23.7]). There was no deterioration in EQ-5D-5L VAS scores in the gilteritinib arm beyond two treatment cycles (data not shown), and relative proportions of patients with no change or improvement in EQ-5D-5L VAS scores at cycle 2 day 1 or at mEOT were similar across treatment arms (Figure S5D).

Relationship between PROs and survival

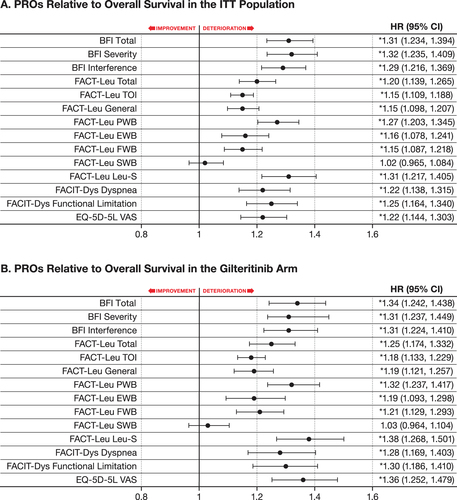

Post-baseline PRO scores were strong predictors of OS and EFS (p< .001; OS: ; EFS: Figure S6A). Across both treatment arms, clinically meaningful worsening of BFI, FACT-Leu, FACIT-Dys, and EQ-5D-5L scores were associated with decreased OS. For example, patients with a BFI total score of Y have a significantly higher risk of death than those with a clinically meaningful lower score (e.g. Y-1.27). Multivariate analyses of OS and EFS, after adjustment for baseline prognostic factors, did not substantially modify the observed relationship between PROs and survival outcomes, with the only change being less significant associations of EFS with the BFI interference score in the ITT population and the EQ-5D-5L VAS score in the gilteritinib arm (Table S3).

Figure 2. PROs relative to overall survival in patients with FLT3mut+ R/R AML. (A) PROs relative to overall survival in the ITT population. (B) PROs relative to overall survival in the gilteritinib arm. Solid circles indicate HRs and horizontal lines indicate 95% CIs. Arrows denote improvement or deterioration in PRO score. *Nominal statistical significance. AML: acute myeloid leukemia; BFI: Brief Fatigue Inventory; CI: confidence interval; EFS: event-free survival; EQ-5D-5L: EuroQoL 5-Dimension 5-Level; EWB: emotional well-being; FACIT-Dys: Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Dyspnea; FACT-Leu: Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Leukemia; FWB: functional well-being; HR: hazard ratio; ITT: intention-to-treat; Leu-S: leukemia subscale; mut+: mutated; OS: overall survival; PRO: patient-reported outcome; PWB: physical well-being; R/R: relapsed/refractory; SWB: social/family well-being; TOI: trial outcome index; VAS: Visual Analogue Scale.

In patients treated with gilteritinib, clinically meaningful worsening of BFI, FACIT-Dys, and EQ-5D-5L scores was associated with decreased OS (nominal p< .001; ); a similar trend was observed with all FACT-Leu scores except for SWB (). Worsening PROs were also associated with relapse/disease progression as indicated by clinically meaningful deterioration in BFI (nominal p< .05), FACIT-Dys (nominal p< .005), and EQ-5D-5L scores (nominal p< .05) in relation to decreased EFS (Figure S6B).

Relationship between PROs and transfusion status in patients treated with gilteritinib

Of 197 patients in the gilteritinib arm who were transfusion dependent (TD) at baseline, 68 (34.5%) became TI during the post-baseline period. Of 49 patients who were TI at baseline, 29 (59.2%) remained TI during the post-baseline period. Patients who remained or became TD had greater increases in BFI scores relative to baseline values, indicating worsening fatigue, vs. patients who remained TI or became TI (Table S4). Although patients who remained or became TD and those who remained TI had improvements in total and FACT-Leu subscale scores relative to baseline values, baseline FACT-Leu scores were higher in patients who were TI at baseline (Table S4). Compared with patients who remained or became TD post-baseline, or remained TI post-baseline, those who were TD and became TI post-baseline had smaller changes in FACT-Leu total and subscale scores relative to baseline, indicating maintenance of HRQoL.

Relationship between PROs and transplant status in patients treated with gilteritinib

Of 247 patients in the gilteritinib arm, 63 (25.5%) underwent HSCT. The rate of CR/CRh in patients who underwent HSCT was 55.6% (CR, 39.7%; CRh, 15.9%) vs. 26.6% (CR, 14.7%; CRh, 12.0%) in patients who did not undergo HSCT (n = 184). Patients who underwent HSCT were more likely to maintain or improve PRO scores across almost all BFI, FACT-Leu, and EQ-5D-5L subscales ().

Table 2. Percentage of patients with improvement or maintenance of PROs at the end of gilteritinib treatment according to transplant status.

Relationship between PROs and hospitalization in patients treated with gilteritinib

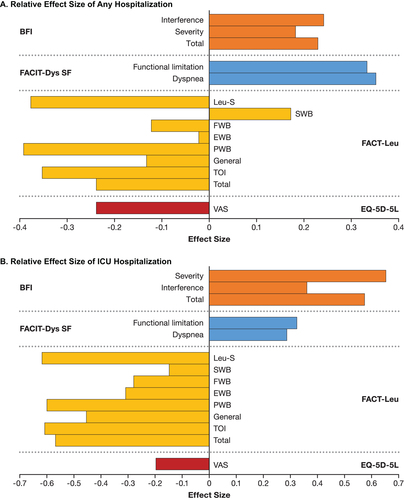

Any first hospitalization was associated with worsening scores across all PRO measures except for FACT-Leu SWB, EWB, and FWB subscales (). Effect sizes reflecting worsening were observed for FACIT-Dys SF dyspnea (0.352) and functional limitation (0.333) scores and for FACT-Leu PWB (−0.392), leukemia subscale (−0.377), and TOI scores (−0.352; ). Hospitalization in the ICU was limited to a small subgroup of patients for whom PRO data were available (BFI, n = 26; FACT-Leu, n = 26; FACIT-Dys SF, n = 15; EQ-5D-5L, n = 27) and was associated with clinically meaningful worsening across most PRO subscales (), with TAMC values for BFI interference and total scores, and FACT-Leu PWB, general, and leukemia subscale scores being greater than clinically meaningful change thresholds. Medium effect sizes were observed for BFI total (0.574) and interference (0.653) scores, and FACT-Leu PWB (−0.600), leukemia subscale (−0.618), and TOI (−0.608) scores ().

Figure 3. Relative effect size of hospitalization across PRO measures. (A) Relative effect size of any hospitalization. (B) Relative effect size of ICU hospitalization. BFI: Brief Fatigue Inventory; EWB: emotional well-being; EQ-5D-5L: EuroQoL 5-Dimension 5-Level; FACIT-Dys: Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Dyspnea; FACT-Leu: Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Leukemia; FWB: functional well-being; ICU: intensive care unit; Leu-S: leukemia subscale; mut+: mutated; PRO: patient-reported outcome; PWB: physical well-being; SWB: social/family well-being; TOI: trial outcome index; VAS: Visual Analogue Scale.

Table 3. Immediate impact of hospitalization on PROs in the gilteritinib arm.

Discussion

As the use of targeted AML therapies becomes more prevalent, PROs may serve as an essential tool in shared decision-making processes between clinicians and patients with respect to treatment selection and dose modification, which may improve medication tolerability and treatment adherence. ADMIRAL was the first phase 3 study to collect PRO data in patients with R/R FLT3mut+ AML treated with a FLT3 inhibitor, and to report on the relationship between PROs and clinical outcomes in these patients.

Fatigue has been identified as the most bothersome symptom in AML with the most detrimental impact on HRQoL [Citation2,Citation10]. In ADMIRAL, patient-reported fatigue levels were generally low in both arms at baseline and during treatment, which might be because most patients (>80%) had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 0–1 at study entry. However, more patients in the gilteritinib arm than in the SC arm reported clinically significant improvement in their worst fatigue during cycle 1. More patients in the gilteritinib arm vs. the SC arm demonstrated improvement or maintenance of fatigue levels during the first two treatment cycles. A greater numeric change from baseline across all BFI subscales was observed with gilteritinib than with SC during cycle 1. Additionally, better OS and EFS were associated with clinically meaningful improvement in fatigue. For gilteritinib-arm patients, any hospitalization had a small but significant impact on patient-reported fatigue.

As with fatigue, levels of dyspnea remained low during the study, and could also be because most patients had a baseline ECOG performance status of 0–1. However, improved OS and EFS were associated with clinically meaningful improvement in dyspnea and other PRO measures. Clinically meaningful worsening of BFI, FACIT-Dys, EQ-5D-5L, and most FACT-Leu scores was associated with decreased OS. Although no marked improvements in HRQoL were observed with gilteritinib therapy, HRQoL remained stable beyond two cycles of gilteritinib therapy. Furthermore, maintenance of HRQoL due to achievement of TI was also observed in gilteritinib-treated patients.

Transplantation also had a favorable effect on PROs in the gilteritinib arm. Compared with gilteritinib-arm patients who did not undergo HSCT, a greater proportion of patients who underwent HSCT maintained or improved BFI, FACT-Leu, and EQ-5D-5L scores. Not surprisingly, any hospitalization or ICU hospitalization was associated with worsening PRO scores, particularly with respect to BFI interference, and total scores, and FACT-Leu PWB scores.

There are some limitations in this analysis. Our PRO data were largely descriptive; comparative analyses of PROs between treatment arms were not performed due to early discontinuation in the SC arm. Thus, a claim attributing association of PROs and clinical outcomes to gilteritinib cannot be definitively made. A potential for bias toward survival by response cannot be ruled out. Longitudinal evaluation of fatigue in the gilteritinib and SC arms up to cycle 2 used an MMRM approach which takes into account missing data [Citation34]. Response outcomes, which may have influenced PROs in patients who remained TD or became TI, were not examined. The dearth of published evidence regarding the impact of clinical outcomes on PROs in AML precluded comparison of findings with gilteritinib with those for other AML therapies. Finally, adjustments for multiple comparisons and sensitivity analyses for missing data were not performed, which limited the power and conclusiveness of our results.

In conclusion, our study suggests that gilteritinib may have a favorable effect on patient-reported fatigue compared with SC during cycle 1, but further investigation is required due to the limitations of this study. Longer survival and achievement of remission were also associated with improved PROs in patients who received gilteritinib. As a targeted therapy, gilteritinib offers convenient oral administration with better tolerability than chemotherapy and serves as a bridge to HSCT. Therefore, PROs can be an important tool in AML therapy selection and shared decision-making processes to optimize clinical outcomes. Furthermore, HRQoL may be a prognostic indicator of progression-free survival [Citation38]. Future investigations should evaluate whether deterioration in PROs is associated with AML progression, determine how response to FLT3 inhibitors drives improvement in PROs, and analyze the impact of these phenomena on hospitalization, a major cost component in disease management [Citation39]. In addition, PROs in HSCT-ineligible R/R AML patients receiving FLT3 inhibitor therapy should be evaluated.

Author contributions

ER contributed to data collection and analysis, as well as the development of the manuscript. BP and MS contributed to the study design, data analysis, and the development of the manuscript. DC and CI were involved in data analysis and in the development of the manuscript. FF, AP, and YK were involved in data collection and the development of the manuscript.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (1.3 MB)Acknowledgements

This study was sponsored by Astellas Pharma, Inc. We acknowledge and thank the patients and their families for their participation in the ADMIRAL study. We also acknowledge and thank all the participating study sites, investigators, and research personnel for their support of the ADMIRAL trial. Medical writing support for this manuscript was provided by Kalpana Vijayan, PhD and Cheryl Casterline, MA, of Open Health Medical Communications (Chicago, IL) and was supported by the study sponsor.

Disclosure statement

ER: Pfizer, Celgene, Agios, Tolero, Incyte Pharmaceuticals, Genentech – non-financial support and/or advisory board honoraria and grant funding from Jazz Pharmaceuticals; DC: no conflicts to disclose; FF: no conflicts to disclose; AP: Amgen, Novartis, Roche, AbbVie, Astellas, Daichi, Jazz Pharmaceuticals – honoraria; YK: Astellas Pharma, Inc. – grants and personal fees; CI: IQVIA – employment; BP: Astellas Pharma, Inc. – employment; MS: Astellas Pharma, Inc. – employment.

Data availability statement

Researchers may request access to anonymized participant level data, trial level data and protocols from Astellas sponsored clinical trials at www.clinicalstudydatarequest.com. For the Astellas criteria on data sharing, see: https://clinicalstudydatarequest.com/Study-Sponsors/Study-Sponsors-Astellas.aspx

Additional information

Funding

References

- Redaelli A, Stephens JM, Brandt S, et al. Short- and long-term effects of acute myeloid leukemia on patient health-related quality of life. Cancer Treat Rev. 2004;30(1):103–117.

- Korol EE, Wang S, Johnston K, et al. Health-related quality of life of patients with acute myeloid leukemia: a systematic literature review. Oncol Ther. 2017;5(1):1–16.

- Wiese M, Daver N. Unmet clinical needs and economic burden of disease in the treatment landscape of acute myeloid leukemia. Am J Manag Care. 2018;24:S347–S355.

- Dohner H, Estey E, Grimwade D, et al. Diagnosis and management of AML in adults: 2017 ELN recommendations from an International Expert Panel. Blood. 2017;129(4):424–447.

- Heuser M, Ofran Y, Boissel N, et al. Acute myeloid leukaemia in adult patients: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2020;31(6):697–712.

- Bryant AL, Drier SW, Lee S, et al. A systematic review of patient reported outcomes in phase II or III clinical trials of myelodysplastic syndromes and acute myeloid leukemia. Leuk Res. 2018;70:106–116.

- Buckley SA, Kirtane K, Walter RB, et al. Patient-reported outcomes in acute myeloid leukemia: where are we now? Blood Rev. 2018;32(1):81–87.

- Cannella L, Efficace F, Giesinger J. How should we assess patient-reported outcomes in the onco-hematology clinic? Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2018;12(4):522–529.

- Nipp RD, Temel JS. Harnessing the power of patient-reported outcomes in oncology. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24(8):1777–1779.

- Tomaszewski EL, Fickley CE, Maddux L, et al. The patient perspective on living with acute myeloid leukemia. Oncol Ther. 2016;4(2):225–238.

- Lucioni C, Finelli C, Mazzi S, et al. Costs and quality of life in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes. Am J Blood Res. 2013;3:246–259.

- Szende A, Schaefer C, Goss TF, et al. Valuation of transfusion-free living in MDS: results of health utility interviews with patients. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2009;7:81.

- Anatchkova M, Donelson SM, Skalicky AM, et al. Exploring the implementation of patient-reported outcome measures in cancer care: need for more real-world evidence results in the peer reviewed literature. J Patient Rep Outcomes. 2018;2(1):64.

- ClinicalTrials.gov. The American Society of Hematology (ASH) Research Registry: a multicenter research registry of patients with hematologic disease; 2019 [cited 2019 Dec 10]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03535220

- Roboz GJ, Rosenblat T, Arellano M, et al. International randomized phase III study of elacytarabine versus investigator choice in patients with relapsed/refractory acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(18):1919–1926.

- Ravandi F, Kantarjian H, Faderl S, et al. Outcome of patients with FLT3-mutated acute myeloid leukemia in first relapse. Leuk Res. 2010;34(6):752–756.

- Thiede C, Steudel C, Mohr B, et al. Analysis of FLT3-activating mutations in 979 patients with acute myelogenous leukemia: association with FAB subtypes and identification of subgroups with poor prognosis. Blood. 2002;99(12):4326–4335.

- Smith CC, Lin K, Stecula A, et al. FLT3 D835 mutations confer differential resistance to type II FLT3 inhibitors. Leukemia. 2015;29(12):2390–2392.

- Efficace F, Gaidano G, Lo-Coco F. Patient-reported outcomes in hematology: is it time to focus more on them in clinical trials and hematology practice? Blood. 2017;130(7):859–866.

- Mori M, Kaneko N, Ueno Y, et al. Gilteritinib, a FLT3/AXL inhibitor, shows antileukemic activity in mouse models of FLT3 mutated acute myeloid leukemia. Invest New Drugs. 2017;35(5):556–565.

- Lee LY, Hernandez D, Rajkhowa T, et al. Preclinical studies of gilteritinib, a next-generation FLT3 inhibitor. Blood. 2017;129(2):257–260.

- Perl AE, Martinelli G, Cortes JE, et al. Gilteritinib or chemotherapy for relapsed or refractory FLT3-mutated AML. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(18):1728–1740.

- Shah MV, Crooks P, New MJ. Symptom and impact disturbance: findings from a qualitative assessment of patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Value Health. 2018;21:S473–S474.

- Cella D, Jensen SE, Webster K, et al. Measuring health-related quality of life in leukemia: the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy – Leukemia (FACT-Leu) Questionnaire. Value Health. 2012;15(8):1051–1058.

- Herdman M, Gudex C, Lloyd A, et al. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Qual Life Res. 2011;20(10):1727–1736.

- FACIT.Org. FACIT-Dyspnea Scoring Downloads [cited 2023 March 15]. Available from: https://www.facit.org/measures-scoring-downloads/facit-dyspnea-scoring-downloads

- Mendoza TR, Wang XS, Cleeland CS, et al. The rapid assessment of fatigue severity in cancer patients: use of the Brief Fatigue Inventory. Cancer. 1999;85(5):1186–1196.

- FACIT.Org. FACT-Leu Scoring Downloads [cited 2023 March 15]. Available from: https://www.facit.org/measures-scoring-downloads/fact-leu-scoring-downloads

- PROMIS Dyspnea Scoring Manual; 2017 [cited 2023 March 15]. Available from: https://staging.healthmeasures.net/images/PROMIS/manuals/PROMIS_Dyspnea_Scoring_Manual.pdf

- EQ-5D User Guides; Version 3.0, September 2019 [cited 2023 March 15]. Available from: https://euroqol.org/publications/user-guides/

- Devlin NJ, Shah KK, Feng Y, et al. Valuing health-related quality of life: an EQ-5D-5L value set for England. Health Econ. 2018;27(1):7–22.

- Kantarjian HM, Mamolo CM, Gambacorti-Passerini C, et al. Long-term patient-reported outcomes from an open-label safety and efficacy study of bosutinib in Philadelphia chromosome-positive chronic myeloid leukemia patients resistant or intolerant to prior therapy. Cancer. 2018;124(3):587–595.

- Walsh LEH, Rider A, Piercy J, et al. Real-world impact of physician and patient discordance on health-related quality of life in US patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Oncol Ther. 2019;7(1):67–81.

- Mallinckrodt CH, Sanger TM, Dube S, et al. Assessing and interpreting treatment effects in longitudinal clinical trials with missing data. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;53(8):754–760.

- Molenberghs G, Verbeke G. A review on linear mixed models for longitudinal data, possibly subject to dropout. Stat Model. 2001;1(4):235–269.

- Weinfurt KP, Li Y, Castel LD, et al. The significance of skeletal-related events for the health-related quality of life of patients with metastatic prostate cancer. Ann Oncol. 2005;16(4):579–584.

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioural sciences. Second Edition Hillsdale (NJ): Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Copyright 1988. [cited 2023 March 15]. Available from: http://www.utstat.toronto.edu/∼brunner/oldclass/378f16/readings/CohenPower.pdf

- Beer TM, Miller K, Tombal B, et al. The association between health-related quality-of-life scores and clinical outcomes in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer patients: exploratory analyses of AFFIRM and PREVAIL studies. Eur J Cancer. 2017;87:21–29.

- Pandya BJ, Chen CC, Medeiros BC, et al. Economic and clinical burden of relapsed and/or refractory active treatment episodes in patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) in the USA: a retrospective analysis of a commercial payer database. Adv Ther. 2019;36(8):1922–1935.