ABSTRACT

Conservation organizations, missionaries and the State of Cameroon have put the indigenous hunter-gatherer Baka Pygmy people of southeast Cameroon at the limelight of development interventions that often do not reflect their needs and aspirations. Despite these benevolent initiatives, the indigenous Baka Pygmy people have remained on the margins of Cameroonian society. This paper attempts to answer the question: Why has service delivery been challenging to this population? The paper argues for a vision of people-centered ‘‘friendly’’ as opposed to economic development ‘‘as an act of aggression’’ or an exercise in epistemic violence that prioritizes conservation instead of people and that refuses the Baka’s right to development on their own terms. The factors stalling development and negatively impacting on the Pygmies’ quality of life include – the Bantu’s dominance of relations with Western(ity), Orientalism and paternalism that refuses the Pygmies freedom of choice and the right to be different. The paper suggests that epistemic decolonization, justice and reflexivity in the practice of social work will improve social service delivery among the Baka Pygmy.

Introduction: development, indigenous peoples and orientalism

This paper examines the failure of service delivery among the indigenous Pygmy people of southeast Cameroon. It attempts to answer the following questions: What factors are preventing the delivery of social services to the Pygmies and what should effective social service delivery look like from an indigenous perspective? It argues that the prioritization of economic growth that constrains freedom over people-centered development, the dominance of the outside world including oppressive relations with the Bantus as well as the orientalist and paternalistic model of service delivery that refuses to consider the Baka Pygmies worldviews, perspectives and rights are responsible for the dysmal quality of life of the indigenous Pygmies. This calls for the need for epistemic decolonization so that the Baka’s voices take centre stage.

Amartya Sen has identified two distinct visions of the development process: one privileges economic growth at the expense of people’s rights and requires ‘‘sacrifices’’, the other is a ‘‘friendly’’ development paradigm that is a ‘‘process that expands real freedoms that people enjoy’’ (Sen, Citation1999, p. 36). To avoid what Cathal Doyle calls ‘‘development aggression’’(Doyle, Citation2009; Ughi, Citation2012), development should be a negotiated process that protects rights, based on meaningful consultation. Development should be the absence of coercion, and recognizes indigenous philosophies, avoids the subordination of indigenous knowledge systems to externally imposed ‘superior’ ones (Alcoff, Citation1991; Escobar, Citation1984; Foucault, Citation1975; Said, Citation1978; Ughi, Citation2012). The focus should be on the long-term. This implies recognition of local environmental knowledge and the expansion of freedoms and choices (Sen, Citation1999, p. 35). Such a vision of development perceive ‘‘human development [as] the end [and] economic development as a means’’(United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) Report, Citation1996:1). In indigenous communities where pervasive poverty comes in the guise of land loss, income inadequacy, health challenges, social marginalization, violence and coercion to forsake traditional practices among others (Ughi, Citation2012)., an appropriate indigenous development model should respect indigenous rights and indigenous people’s right to participation as people with agency. Such a vision of development sees indigenous peoples as proactive development actors, not victims of development. They should decide on their priorities for the development process and control their socioeconomic and cultural development. It should be based on free, prior and informed consent, a participatory consultation process to development projects from which benefits should accrue from the exploitation of their green resources (Ughi, Citation2012, p. 17).

A successful development vision for indigenous peoples should be empowering and in consonant with the ‘‘human development’’ paradigm. It should eventuate into a ‘‘a more social and spiritual form of development by seeking a viable environmental response to issues such as deforestation and the consumption of non-renewable natural resources’’ (McNeish, Citation2005, cf. Ughi, Citation2012, p. 23). According to the UNDP, “Human Development” is characterised by “empowerment” requiring that development is made by the people, not only for the people, with an aim of “giving people the power, capacities, capabilities and access needed to change their lives, improve their own communities and influence their destinies”(UNDP Report, Citation1996:45; Ughi, Citation2012, p. 23; Sen, Citation1999). This implies the centrality of property rights that serve as an enabler to the enjoyment of other rights, and are intertwined with the right to development projects involving resource extraction. This will further imply the right to internal and external self-identification and collective rights. It should avoid an assimilationist notion of development through development policies that accommodate Baka Pygmies by avoiding encroachment and forced eviction or even killings, respects their culture, religion and traditional ways of life and that intersect with land and ethnic belonging(Ughi, Citation2012). Apart from guaranteeing individual and collective rights, such a model should see them as equal partners in development, and not as subalterns.

In line with Edward Said, orientalism is a system of deliberate domination, exclusion, restructuring, and the imposition of authority (power) over others. It is charaterised by a sense of superiority (Said, Citation1978, p. 3; Radhakrishnan, Citation2012; Eliassi, Citation2013). As a system of ideas and practices, orientalism consists of a discourse about subaltern groups as a monolithic entity, void of internal differences and heterogeneity. Orientalist representations are characterized by stereotypical representation, overgeneralization and the misrepresentation of subaltern groups, their cultures and societies in essentialist modes (Eliassi, Citation2013; Radhakrishnan, Citation2012). It involves culturalism through which an ethnic group’s culture is presented as a given, homogenous, monolithic and geographically bounded and transmitted across generations (Scuzzarello Citation2008, Stolcke, Citation1995 cf. Eliassi, Citation2013, p. 34). Development in orientalist terms is analogous to compliance to a standard development paradigm – the replication of Western-styled development – which normalizes and naturalizes Western superiority (Spivak, Citation1999, p. 114ff, Escobar, Citation1984; Foucault, Citation1975; Said, Citation1978; Alcoff, Citation1991) and economic development as an end, not a means (UNDP Report, Citation1996, p. 1; Sen, Citation1999). In the words of Linda Alcoff, indigenous people suffer from ‘‘discursive coercion and even violence’’(Alcoff, Citation1991, p. 6). In general, government authorities enable capitalist development by failing to cooperate with or consult indigenous people in deciding matters that affect their lives and human rights. Framed as development, free trade and the conservation of nature, indigenous peoples are witnessing their rights denied continuously or violated (Indigenous World Citation2006, p. 10). Our socioeconomic, gendered, cultural, geographical, historical and institutional positioning are intimately intertwined with orientalist representations of marginalized and powerless people such as the Baka Pygmies. The challenge for us as academics and activists is to be self-reflexive (Said, Citation1978; Kapoor, Citation2002, Kapoor, Citation2004, Spivak, Citation1998, Alcoff Citation1991). The ethics and politics engendered by the process of othering underlying the question of representation legitimize the ‘subaltern Other’ (Pemunta Citation2018a, Spivak, Citation1988). Gayatri Spivak´s argument conflates two interrelated but discontinuous meanings of ‘representation’ (Spivak, Citation1988, p. 275–276) (1) ´Speaking for´, in the sense of political representation, (2) ‘Speaking about’ or ‘representing’ (rather than speaking with) in the sense of carving out a portrait. In the representational process, we tend to neglect our collusion (Kapoor, Citation2004, p. 628). The vision of development being imposed on the Pygmies by various development actors is one intended to save the Pygmies from primitivity by ‘normalizing’(Foucault, Citation1975) and allowing them to join the train of modernity prescribed by Western institutions in collusion with African political leaders – even when there are alternative modernities. This calls for the human development of the Pygmies within their environment – a vision of ‘‘listening to the people’’, one that serves their needs and aspirations, and not just the interests of the capitalist.

In the preceding sections, we first present the social location of the Baka Pygmies in Cameroon. Historic factors, particularly transformations in land usage through colonization and State monopoly of natural resources have connived with neoliberal conservation approaches to impede indigenous rights to ancestral land with debilitating socioeconomic and health consequences. Secondly, we state the research methodology informing the data elicitation process and discuss the findings of this study and its implication for effective service delivery to the Pygmies.

The Baka Pygmies in Cameroon

This section argues that historic factors, particularly transformations in land usage through colonization and State monopoly of land and forestry resources have connived with neoliberal conservation approaches to dispossess the Baka Pygmies from their ancestral homeland. These factors have resulted in the eviction of the Pygmies from their ancestral land and their settlement in Bantu villages where agriculturalization was imposed on them. Additionally, the domination of political processes by the Bantus – the people among whom they have been forcibly settled has made service delivery challenging to the Baka indigenous people thereby further marginalizing these people who are already on the margins of local social structures.

The Baka Pygmies of southeast Cameroon are the major Pygmy group with an estimated population of 30,000 to 50,000 of the total estimated 250,000 to 350,000 African ‘pygmies’, in Central Africa (Fitzgerald, Citation2011). They are traditionally one of several semi-nomadic, hunter-gatherer people groups in Equatorial Africa inhabiting the adjoining dense tropical rainforests of Cameroon, Gabon, and Congo. Today, they are victims of neoliberal conservation, logging, mining and tourism development projects by State actors, conservation organizations, logging companies and tourism developers that have led to their eviction and pitted them in conflict against these development agents and the Bantu communities in which they now live and sedentarization imposed on them. Through sedentarization and the creation of national parks and protected areas, they have been refused access to the forest and their identity and wellbeing as well as their future are in endanger (Olivero, Fa, Farfán, Citation2016). They have now become ‘‘The Forest People Without a Forest’’ (Lueong Citation2017), ‘‘sacrificial lambs’’ (Doyle, Citation2009; Sen, Citation1999, p. 36). The neoliberal conservation agenda that consists of extraction and the prioritization of animals over people imposed on them lacks prior, free, informed consent, thus curtails freedoms (Sen, Citation1999, p. 33), prioritizes development instead of improving the quality of life people and has led to displacement and social disarticulation. It is therefore a form of epistemic violence (Alcoff, Citation1991) and ‘‘development aggression’’ (Doyle, Citation2009; Ughi, Citation2012; UNDP Report, Citation1996) that come with multiple impoverishment risks including: ‘‘landlessness; joblessness; homelessness; marginalization; increased morbidity/mortality; food insecurity; loss of access to common property resources; and social disarticulation’’ (Cernea & Schmidt-Soltau, Citation2000). Over time, the Baka have been uprooted from their physical and socio-cultural environment in the name of economic development through conservation initiatives and sedentarization that has brought them into conflict with the dominant Bantu society (Pemunta, Citation2018b, Citation2017). This erasure is also undermining ‘‘social development” initiatives among the people.

Brief presentation of the study

Between June and August 2015, we elicited qualitative data from 84 respondents (54 Baka Pygmies and 30 Bantus) that were purposively selected in Lomié sub-Division of the Upper Nyong Division in Cameroon’s southeast region. We combined individual in-depth interviews; and focus group discussion sessions (FGDs). Two FGDs were arranged in Nohmejo and Bosquet as well as in-depth individual interviews with 20 respondents. In Campo Sub-Division in the Ocean Division of the South Region, two FGDs were organized for both men and women; three FGDs were further organized in the Akak village as well as a FGD session in Nkoleon village. In line with the objectives of the study, a needs assessment was conducted. Qualitative interviews were considered most appropriate because of the exploratory nature of the issues under discussion. Additionally, as an empowering methodology, it allowed the Baka Pygmies to speak for themselves.

The researcher, one who affirms Indigenous Rights, was empathetic and constantly showed respect for the Baka’s rich culture. Conscious of the power dynamics between himself – a privileged Western-trained and therefore, presumed ‘‘civilized man’’ and “them” Baka pygmies, he adopted the role of a keen listener and learner. During our conversations on the impact of development on their overall way of life in the wake of the cultural disruption orchestrated by forest conversation organizations and the extractive industries, their perspectives took centre stage.

Emerging themes

Collusion of Bantu led development organizations & government

The collusion of Bantu and development organizations in the exploitation of the Baka pygmies is specified in the example of Respondent No. 20 who emphasized that ‘we do not know why they brought us here to suffer, we lack water and projects earmarked for us, pygmies are hijacked by Bantus’’. This is a clear indication that the Bantus are exploiting the Pygmies. The Bantus do not only speak for them, alongside the government, they are actually at the forefront of development and conservation organisations. They can therefore be perceived as colluding with these external forces that have displaced the Pygmies from the land of their forebears and, impoverished them because they are the ‘‘other’’. Bantu Chiefs who control village politics often coerce them to vote for the ruling Cameroon People’s Democratic Movement (CPDM) party. They are marginalized in political voice and decisions about their development and future wellbeing. They are for instance, left out of community associations created to manage the exploitation and sale of Non-Timber Forest Products (NTFPs), and a significant source of income to Baka women and to Bantu who do not cultivate commercial crops(eg cocoa) (Toda, Citation2014). We observed that the Baka do have only a symbolic presence in associations related to the management of natural resources in the village – including the Comite de Valorisation des Resources Fauniques (in French) or COVARES charged with revenue management from sport hunting in community-managed hunting zones. Only groups such as Baka men and Konabembe women meet the requirements of international aid agencies including the Netherlands Development Organization (SNV). In reality, Bantu males (especially Konabembe), exert control over these organizations in villages including Gribe (see also Pemunta, Citation2018a; Toda, Citation2014). They are therefore, excluded from economic and political participation/opportunities. This top-down development model is an exercise in epistemic violence (Alcoff, Citation1991) that refuses the Baka Pygmies voice since they have been refused access into the rainforest, their culture’s bedrock.

Intensive logging has resulted in the monetization and subsequent transformation of the Baka’s forest-based economy. Buyers and merchants who have been attracted into the area purchase cocoa and sell manufactured goods including sugar, salt and soap (Toda, Citation2014). The Bantu still control relationship with these external actors, even when the livelihood of the Baka depends on forest incomes. The Baka have consequently remained on the margins of Cameroonian society with no leverage over their natural resources. Apart from noise that frightens game and environmental degradation resulting from intensive logging and mining, before the various changes in the environment brought about by neoliberal actors and restrictions imposed on the Pygmies through the creation of protected areas, nature and man or society were intimately linked. Within the neoliberal development, conservation has become both a mechanism of exclusion (excluding those that are othered, as well as a mechanism of governmentality (Pemunta, Citation2018b, Citation2017; Pemunta & Mbu-Arrey, Citation2013). It is about both the control of nature but also of the Baka Pygmies:

Where we live is considered as the park. We are just like animals within this park. Despite this, we have been forbidden from hunting animals. Ya’a (elephant) come right at the back of our houses to destroy crops. We cannot do anything because the government will jail us. Here it is better to kill a human being than an animal. It looks like the government prefers animals to us because it is better for the animal to come and destroy our crops than for us to kill the animals (Respondent No. 10).

Prioritization of animals versus people – as exploitation

The modern management of natural resources that prioritizes animals at the expense of human beings constitutes a disruptive factor in the traditional religious life of indigenous peoples. Elders reported that they are unable to teach their children indigenous skills because they cannot go into the forest. During a FGD, one respondent, a Bagyeli Pygmy stated:

Other people treat us like animals, yet we are restricted from certain places in the forest where animals like us live. We have been given only one hectare of land for our activities. Forestry exploiters often give only a small token of gifts to exploit our forest. It is always the Bantus and their Chiefs exploiting us in collusion with the government and NGOs who love the forest and animals more than us. We live in misery (Respondent No. 12).

Our knowledge of the forest, medicine and hunting risk being lost forever. We are unable because of restrictions to transmit this knowledge over to our children and to ensure the survival of our culture. Eco-guards are ready to shoot on any of us seen in the forest. We have suddenly become enemies of the forest where our ancestors lived peacefully (Respondent No. 5).

With the erosion of their traditional egalitarian social system, the responsibility for children’s wellbeing and household food provisioning has fallen increasingly on Pygmy women. In conventional, forest-based communities, these roles are more equitably shared between men and women. Pygmy women who have to rely on begging or poorly paid wage labour to obtain food have great difficulty meeting their family food needs.

Consequences of land restrictions

Changes in the availability of wildlife and edible fruits because of access restrictions have changed the Pygmy´s respective nutritional habits and consumption pattern because they have been attributed limited forestland to work on. The disruption of man-nature interdependence comes with health consequences (Joiris, Citation1996).

In the setting up of national parks and reserves, local communities, including the Baka who are ‘‘losing access to forests they have inhabited for centuries’’ (The Indigenous World, Citation2006, p. 489) were never consulted (Pemunta, Citation2013, Citation2018b). Even in cases of discussion, ‘‘indigenous hunting and gathering communities were almost never involved’’ (Indigenous World, Citation2006, p. 489). During the consultation process, the Bantus spoke on their behalf. They suffer severe social marginalization because of lack of access to livelihood resources and land for cultivation. In Cameroon, forest communities suffer from structural discrimination because of the government´s failure to invest in public rural infrastructure. This is ‘‘coupled with support for logging and an addiction to donor funds for biodiversity’’(Ibid: 488) conservation. The result of this discrimination is magnified on ‘‘indigenous Pygmy communities from across the southern forest zone, whose livelihoods rely on forests and who continue to remain socially and economically marginalized, receiving few benefits from the small amounts of funds which do eventually trickle down to the regions’’ (The Indigenous World, Citation2006, p. 488; Pemunta, Citation2013; Pemunta & Mbu-Arrey, Citation2013).

Before changes in the forest environment, the forest was the breastfeeding mother offering the Baka enough game, wild yams (their ‘‘supermarket’’) and medicinal plants (‘‘pharmacy’’) and spiritual sanctuary. In short, the forest is the only source of food, clothing, medicines, consumer products as well as products regulated by taboos. Compromising the displacement and socioeconomic well-being of the Baka is the hierarchical relationship between them and their Bantu neighbours.

The dynamics of paternalistic Bantu-Baka relations

The Baka maintain hierarchical, paternalistic relations with the Bantus who are mediators of their encounter with neoliberal development actors. As a mark of this exploitative relationship that exacerbates their poverty, every Baka family is subservient to and attached to a Bantu family. These patrimonial relations that are based on the exchange of services – including labour – have evolved over time from ancient complementarity characterized ‘‘by balanced relations within the system of traditional exchange’’ (Joiris, Citation1994, p. 86) to a system of exploitative commercial exchanges. The Baka are often cheated in exchanges of ‘‘game, forest products, and labour (services) against iron, salt, soap, agricultural products and the protection of the villagers’’ (Ibid). As forestry resources began to deplete through agriculture and intensive logging that led to the creation of more access roads, hunting and gathering concurrently began to shrink inordinately. And as agriculture became indispensable for satisfying needs that could no longer be met by traditional methods, the ‘‘relations of clientship grew weaker and gave place to unequal exchanges marked by the economic domination of the Pygmies by the villagers’’(Ibid). Apart from being victims of multiple forms of abuses by the Bantus, the Baka are incessantly entangled in perennial land disputes that could lead to their eviction at any time since they often have no land titles (Pemunta, Citation2013, Citation2018). They are also embroiled in disputes over forest resources as well as benefits accruing from forestry exploitation by multinational corporations with their Bantu masters and neighbours (Egbe, Citation2012; Pemunta, Citation2013). The traditional system of exchange and therefore their relationship has witnessed transformations with some exchanges assuming a much more commercial character.

The Baka had a traditional nomadic lifestyle. Bantu farmers were also mobile and divided into smaller groups. This means the social organization was quite fluid. This fluid social organization was transformed by the establishment of the ‘’village’’ as the unit of administration through colonial and postcolonial settlement policies that ‘’accorded the role of pillars of the political community to the “original” Konabembe people. There remain, however, latent social tension and conflicts among different groups (clans or lineages) within the village’’ (Toda, Citation2014, p. 161). The sedentarization policy that preceded the forcible settlement of the Baka in roadside Bantu villages has increased their economic dependence on the Bantu who practice small-scale subsistence and cash crop farming (cocoa) and use the Baka as wage labourers. Despite the ambivalence and complexity of the relationship between the two groups – with both positive and negative sentiments towards the other, they maintain a mutually dependent relationship (Pemunta, Citation2018). The Baka however, remain excluded from membership in community-based local associations including those related to the management of natural resources. They are excluded whereas NTFPs constitute an important source of their livelihood (Toda, Citation2014).

Since we came to live in Bantu villages, they exploit us. We work on their farms for virtually nothing. They take our goods and force us to hunt for them. When forest exploiters and loggers come, it is always them representing us as if we have no right to speak and negotiate for ourselves (Respondent No. 28).

The Pygmies are specialized in the meat trade, herbal medicine, and therapy as well as in the provisioning of entertainment (livening up) of village festivals. The troubled relationship and unequal exchange surpases ‘‘the classic form of integration at the level of the village ecosystem and sometimes involves integration into the system of market exchange’’ (Joiris, Citation1994, p. 87). The goods of the Pygmies are hardly exchanged for cash but instead for alcohol, cultivated food or tobacco while their labour is exploited without commensurate remuneration. They are often rewarded, if ever, in kind, and their cocoa farms are confiscated (Joiris, Citation1994; Pemunta, Citation2013). Furthermore, there is low price purchase of their collected game as well as of their labour in local industries where they occasionally work. They are beaten and humiliated in public, as well as insulted in the presence of foreigners.

Several factors are responsible for this exploitative relationship and the social exclusion of the Baka. First off, the historically unequal relationship between the Baka and the Bantu has made the former to suffer from an inferiority complex. The Bantu perceive the Baka Pygmies as sub-human beings, and ‘‘primitive people’’. A Bantu Chief (Respondent No. 23) stated that:

The Pygmies living in this village are ours. They are supposed to work on our farms whether they like it or not. If they do not, they can go back into the forest. We are working with government to civilize them so that they should stop being primitive.

This deeply entrenched binary opposition serves as justification for the shabby treatment of the latter. Contrary to the Pygmies, the Bantu and mainstream Cameroonian society are represented as ‘modern’, ‘progressive’ while the Pygmies are largely ‘‘represented as ‘primitive’, ‘traditional’, and ‘premodern’’’(Pemunta, Citation2018a, Eliassi, Citation2013, p. 34; Egbe, Citation2012). They are refused rights and opportunities that are readily afforded to others in mainstream Cameroonian society just because of ‘‘who they are…certain groups cannot fulfill their potential, nor can they participate equally in society’’ (Department for International Development [DfID] Citation2005 cf. Egbe, Citation2012, p. 2).

Themes on governability

Paul Raffaele (Citation2008) has recounted in an online post, an incident of three scowling Bantus, among them a chief – Joseph Bikono brandishing machetes to the Baka Pygmies in the forest and questioning them as to who gave them access. He is not only attempting to control them by insisting they remain in the village, he is also controlling nature, man-nature relationship and access into the forest (Pemunta, Citation2018b).

Who gave you permission to leave your village? You Pygmies belong to me, you know that, and you must always do what I say, not what you want. I own you. Don’t ever forget it (Raffaele, Citation2008).

Additionally, hierarchical development models suggests the refusal of the right to development for these indigenous peoples because they are perceived ‘‘as a threat to the basic principle of state sovereignty’’ (Ughi, Citation2012, p. 22.), as ‘‘challenging state-citizenship relationship, both because of their distinctiveness as a community and their differing interests and perspectives. Yet, the liberal and individualistic approach to human rights – and of the international system more generally – places limitations on policies aimed at development and poverty reduction, particularly in regards to indigenous poverty’’(DfID Citation2005 cf. Egbe, Citation2012, p. 2). Moreover, the Baka’s semi-nomadic way of life, and misgivings about the Bantus tend to limit the impact of various social welfare projects undertaken for their emancipation as well as perpetuate these unequal relationships. It should, however, be noted that during the celebration of Baka rites in which the Bantus take part, there is usually a temporary reversal of this situation. This is usually the ultimate moment during which the Baka can exercise their authority over the Bantus.

Although the Baka have adopted the slash and burn cultivation techniques of their Bantu neighbours, the small and rudimentary sizes of their fields/plantations, coupled with inadequate harvests during some seasons due to climate change suggests that they mostly depend on Bantu villagers and therefore lack food self-sufficiency. This partial system of agriculture is not sufficient in itself ‘‘to satisfy the demand for food’’ (Joiris, Citation1994, p. 87). Semi-nomadism constrains the freedom of these peoples of the forest, freedom of which the Baka are extremely jealous. Alongside climate change, semi-nomadism has made them even more dependent on the Bantus. They can be said to be facing the consequences of atomization since their society was initially complementary with that of the Bantus (see Joiris, Citation1994).

The Baka are involved in a wide range of commercial activities: artisanal hunting and fishing, the gathering of forest and non-forest products (mostly by women) such as mangoes and wild yams, caterpillars, fungi, termites, koko (Gnetum africanum) leaves, cassava sticks, honey, etc., poaching and trading in animal products depending on the season. In tandem with Cameroon’s 1994 Forestry regulation, small-scale or subsistence hunting is undertaken mostly with the use of plant material (traps), but also electric cables, crossbows, nets, etc. The catch from this hunting expedition are exclusively intended for consumption, with no commercial purpose. It also involves the hunting of rodents, small reptiles, birds and other well-defined animals (Class C). Trapping is a recent practice among the Baka and collective hunting (in a group) is still the most widely used method (Pemunta, Citation2018b). Through hunting, the Baka satisfy 80% of their needs (Joiris, Citation1998) and restriction to forest access therefore spell doom for them.

The intensive exploitation of certain therapeutic species of flora including sapelli and Moabi in areas close to homes poses a severe threat to the Baka´s pharmacopoeia since they can no longer access the forest medicines on which they relied and are in danger of losing their rich traditional knowledge of herbal medicine. The most widely used areas for gathering are those that are near their camps, or near national parks from which they have been forbidden. Simultaneously, some of the most sought-after forest and non-forest products are becoming scarce in the forest, ruining their livelihoods and thereby obliging them to adopt sedentarization through agriculture.

Agriculture

The Cameroon government’s sedentarization policy towards the Baka Pygmies that began in the 1960s has prompted them to take an interest in agricultural activities. Sedentarization was a conscious attempt to transform them from ‘‘a nomadic hunting and gathering way of life to rudimentary agriculture’’(Joiris, Citation1994, p. 84). Their encampments were accordingly, built along roadsides. They were allocated land on which to cultivate food crops. They were also encouraged to take up schooling as well as health education and agriculture (Ndtoungou, Citation1972, Joiris, Citation1994). Hunting and gathering have however remained the main cultural reference through which the first symbols and values of the Baka value system are derived and transmitted (Abéga and Bigombé, Citation2006; Joiris, Citation1994; Pemunta, Citation2013). It is nevertheless also true that as a way of life, agriculture co-exists with hunting and gathering activities. In the wake of climate change, conservation, deforestation and therefore restrictions on access to the forest and fewer games, it is even becoming a central activity for some Baka. Moreover, most Baka identify themselves professionally as farmers. Thus, agriculture involving the growing of food crops including tubers of manioc, macabo, plantain and corn for household consumption to cash crops (cocoa) is increasingly occupying a central place in the life of the Baka. When compared to the farming activities of their Bantu neighbours, food production is more feminine, and mostly undertaken on relatively small plots of land.

However, despite gradual awareness among the Baka and the need to secure their food needs, they are still used as labourers in the farms of the Bantus. In exchange for their labour in cultivating Bantu fields, they usually receive a much lower price than the effort invested (cigarettes, local wine and silver coins). Similarly, the Baka are increasingly interested in the production of income generating cash crops. In Bidjouki and Kounabembé areas, we observed significant cocoa plantations belonging to the Baka. At the Baka camp in Kotter, in the Bidjouki area, we learned that the Baka were the first to establish farms and that the Bantu joined them after the early somewhat successful harvests. However, most Baka owners of cocoa plantations always lease out their farmland because they are not capable of maintaining these farms for a long time. In the Madjoué, and Kounabembe areas, we observed the Baka transporting the cocoa beans from plantations leased out by other Bakas. The real aim of sedentarization was to ensure tax collection (Pemunta, Citation2013). It was therefore not an act of benevolence per se.

Approaches to ‘‘development’’ framed from an orientalist perspective

According to David Scott (Citation2011:306) ‘‘Destruction – is the one thing the Orient understands’’. This statement poignantly suggests that the Western understanding of the ‘‘Other’’ that orientalism produces hinders development. In other words, development agents and agencies presume to know what the beneficiaries of development want and accordingly, provide guidance to ensure a successful growth towards a better self by governing and imparting the culture and values of Western society (Pemunta, Citation2018a, Dube, Citation2009, Alcoff, Citation1991; Kapoor, Citation2004; Spivak, Citation1988). This lingering underlying structural epistemology of colonized knowledge and structures assumes that the West holds the most appropriate/best answer for the entire world – progress, faiths, medicine, education, environmental care, development and freedom. It is this vision adopted during colonial times that continues to hold sway and informs global economic, political and medical policies while rejecting indigenous knowledge frameworks and practices (Pemunta, Citation2018a). In this light, western education, medicine and religion continue to be marketed as universal standards – as a universal solution to all people in all places (Scott, Citation2011, Radhakrishnan, Citation2012; Spivak, Citation1988a, Citation1988b, Kapoor, Citation2004; Alcoff, Citation1991, Dube, Citation2009, Brah, Citation1987). ‘‘This structural arrangement ensures that the whole world remains an accessible market for western/northern ideas and services’’ (Dube, Citation2009, p. 3). We will illustrate these orientalist approaches to development with initiatives aimed at bringing modern formal western education and healthcare to the indigenous Baka Pygmies by the State of Cameroon, denominational missionaries and NGOs.

This section argues that the modern educational system in place in Cameroon is neither adapted to the needs of the Pygmies nor to their traditional nomadic way of life. The Pygmies further suffer from discrimination and to worsen matters, schools are located in Bantu communities, and they have to cover a considerable distance and face discrimination in accessing these tertiary institutions. Worsening their situation and pushing them deeper into poverty is their lack of access to healthcare.

Lack of access to education

According to Article 14 of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples “Indigenous peoples have the right to establish and control their educational systems and institutions providing education in their own languages, in a manner appropriate to their cultural methods of teaching and learning’’. A wide range of other international human rights instruments, including the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) further protects the right of indigenous peoples to education. Furthermore, Goal 4 of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development calls for the need to ensure equitable access to all levels of education and vocational training for indigenous peoples and children as well as other minorities in vulnerable situations (United Nations, Citation2016).

The academic calendar clashes with the Baka’s subsistent activities that often involve the entire community. Though hunting and gathering are decreasing in importance amongst the Pygmies with stable homes, they still carry on with this cultural practice. They believe hunting and gathering is a cultural stock of knowledge that needs to be transmitted from the older to the younger generation. This explains why during their hunting season, the men, women, and children abandon their homes and other activities and go deep into the forest only to be back after weeks or months. When asked why, they said it is to hunt and look for food. However, when one looks at the quantity of the catch and food brought back, it does not really answer the question of their spending weeks or months in the forest. Thus, there is a local myth according to which the Pygmies have special rituals that they perform in the forest. They, therefore, do not only use the forest for hunting. As informant No. 07 stated, ‘‘we hunt while performing our rituals in the forest’’.

Furthermore, high rates of school dropout was reported among the people. One denominational school instructor (Respondent No. 23) conceded that:

Nevertheless, we are here to impart knowledge to this people and to teach them the way (word) of God. With the effort that we are making, at the initial stage, at the beginning of the academic year, we had more than 133 pupils. However, we discovered that many of them dropped out, but when you ask what is happening, they will tell you that they want to go back to the forest, they will say they prefer to work in the forest.

Most pupils do not complete their education and therefore have no end of course certificates. Additionally, FGDs revealed that the widespread problem of discrimination against Pygmy children discourages them from attending primary schools, which are most often, located in Bantu villages. Pygmy children are often intimidated. They are often told: ‘‘School was not meant for you, return to the forest’’. Besides the high cost of education, the academic curricular is not tailored to respond to the needs of the Pygmies (Egbe, Citation2012; Pemunta, Citation2013). Observations showed that they are more skilled in practical (technical) than in the general education paradigm provided in Bantu communities with the aim of acculturating Pygmy children. One respondent, a police officer wondered aloud why the researcher was interested in studying ‘‘these animals’’: ‘‘Why are you interested in studying these animals?’’. This policeman’s statement speaks to the shabby treatment and negative perceptions and discrimination to which the Pygmies are subjected. Despite some variations, public perceptions of the Pygmies are largely negative. Twenty-six (26 of 50 (24 Baka and 2 Bantus) participants in a study stated that Pygmies were ‘‘God’s creation’’. For 7 of 15 Bantu participants, ‘‘Pygmies are thieves, liars, dirty and unscrupulous people,…animals, slaves, servants, ugly looking and toothless people’’. On the contrary, 11 of 35 Baka Pygmies had a positive perception of themselves as hard-working people, thoughtful and reasonable individuals (Egbe, Citation2012, p. 4). In attempts at materially improving the situation of the under-privileged Pygmies, the effect of ‘‘discourse is to reinforce racist, imperialist conceptions and perhaps also to further silence [the Pygmy’s] own ability to speak and be heard’’ (Cotera et al. Citation2015, Alcoff, Citation1991, p. 26; Kapoor, Citation2002, Kapoor, Citation2004, p. 632). Similarly, a government official serving in Lomé reported concerning an experimental education project – ‘Education for All’project” in the Baka language that it failed to gain traction because – ‘‘the Baka are a bizarre people. They are a strange people’’. We observed well-constructed school buildings in the Nomejoh and Akak communities. There were, however, no pupils in sight on a typical school day. A government official working with the Cameroon Ministry of Social Affairs (respondent no. 06) conceded:

We are operating in this sector in three ways. First, we are sensitizing parents to enroll their children in school because that is a problem. We sensitize the parents because from now to June, they go to the forest to gather or collect nuts. They do not even think of coming back. Some also remain there, and we have to force them or bring them out by force. That is why we educate them to enter the forest, do whatever they are doing, and think of coming back to the village especially at the end of August so that their children can enroll in school. Secondly, we endeavour to pay the school fees. Thirdly, we pay them a pocket allowance for their upkeep. Neither the government nor the National Participatory Development Programme (PNDP) pays the school fees regularly.

Exacerbating matters is the lack of access to the job market for the few Pygmy graduates that manage to go through the formal educational system. In contrasts to 20 Bantu respondents, only two of our 30 Baka Pygmy respondents had completed primary education. Parents, therefore, do not see the value of education and would instead prefer the traditional educational model for their children (see also Ayele, Citation2017, Egbe, Citation2012; Pemunta, Citation2013). A positive relationship has been established between the level of education and exclusion: lower level of education is associated with a higher level of exclusion and vice versa (Egbe, Citation2012, p. 4).

The factors inhibiting school attendance among Baka Pygmy children include the shabby treatment inflicted on them by Bantu children and, the unwillingness of Baka parents to enroll and pay school supplies for their children. Baka parents however claim that the creation of separate educational institutions for their children will be a step towards resolving the problem of discrimination and shabby treatment from Bantu children. Across the southern Cameroon forest zone, deeply entrenched extreme poverty connives with lack of essential social services, as well as rural population explosion and negatively affect the rights of Cameroon´s indigenous forest communities including the Bakola, Bagyeli and Baka Pygmy communities (The Indigenous World, Citation2006, p. 489). Through the Ministry of Social Affairs, the Cameroon Government has set up schools under trees in some of the villages. Bantu volunteers (mostly retired officials) run these schools. They teach the Baka notions of citizenship and especially communication in the French language. The classes are meant to civilize and assimilate the Baka and to encourage them to be good citizens by paying their taxes and voting during national elections. Like development, education is a tool of governmentality (Foucault, Citation1975). The provision of knowledge to the Pygmies is akin to the ‘‘benevolent first-world appropriation and re-inscription of [the Pygmies.] as an Other’’ (Spivak, Citation1988a) as well as a form of normalization (Foucault, Citation1975). It is also a way of depoliticizing poverty issues as well as advancing state authority (governmentality) (Ferguson, Citation1990, p. 256).

Lack of access to healthcare

Missionaries, NGOs, and logging companies have deployed efforts through health programmes to bring healthcare to Baka Pygmy communities. This suggests the state’s failure to provide these peoples with healthcare infrastructure (see also Egbe, Citation2012; Ngima, Citation2015; Pemunta, Citation2013) and the blatant violation of their right to healthcare. According to Article 25 of the (UDHR): ‘‘Health care should be Available, Accessible, Acceptable and of the highest Quality achievable (AAAQ)’’. Extrapolating from the UDHR, Mann (Citation2006:1940), states: “One element of what might be called an “ethic of health and human rights work” is the need for inclusiveness and tolerance”. Like many other indigenous peoples, the Pygmies right to healthcare is trampled upon due to discrimination based on their gender, social status, immigration status, and lack of proficiency in the French language. The overall effect among others is that discrimination prejudices their right of access to health knowledge and information. Apart from the acute lack of financial resources by the Pygmies with which to avail themselves of modern healthcare facilities because of the deeply entrenched poverty in which they live, their mobile lifestyle poses an obstacle to the delivery of social services including healthcare to them. Besides deprivation of resources, poverty affects access to healthcare services (Aue & Roosen, Citation2010) and constitutes part of a larger vicious cycle: the lack of access to healthcare can lead to worsening health status that keeps people in poverty – the single largest determinant of health (Peters et al., Citation2008). Modern healthcare facilities, therefore, remain physically and economically inaccessible to most of them. This suggests the need to incorporate mobile and sedentary strategies as well as the integration of modern and traditional healers in healthcare delivery among the Baka. Additionally, the attitude of healthcare staff who consider the Pygmies as ‘‘primitive people’’, although gradually changing is still a matter of concern. The negative stereotyping, exclusion and subjugation the Pygmies encounter from their neighbours the Bantus and dominant society affect their mental health situation.

The Baka Pygmies believe in both personalistic and naturalistic medical systems. In the former, the sick individual is considered a victim of a supernatural agent, a target of punishment for reasons best known to him or her. His or her actions must have provoked the anger of the gods, their hatred or jealousy or s/he must have violated a significant cultural norm. ‘‘There is no concept of accident’’ (Ibeheme et al. Citation2017, p. 5). On the contrary, ‘‘in a naturalistic system, illness is explained in systemic, impersonal terms’’ (Brown & Closser, Citation2016, p. 188). Good health is the outcome of a balance between ‘‘insensate elements in the body such as heat, cold, the humor or dosha in South India, the Yin and Yan in China’’ (Ibid) in the individual´s natural and social environment. When this equilibrium is disrupted, from within/without either by natural causes, including at times, by heat, cold, or at times by strong emotions, the individual falls sick (Brown & Closser, Citation2016; Ibeneme et al., Citation2017).

Most Pygmies still use herbs from the forest for the treatment of ailments especially those believed to be caused by personalistic agents. They have a reputation in traditional healing and their indigenous medicinal knowledge and powers in the treatment of certain illnesses (particularly those believed to be caused by witchcraft including epilepsy) is widely solicited by patients from neighbouring Bantu communities as well as from distant communities within Cameroon.

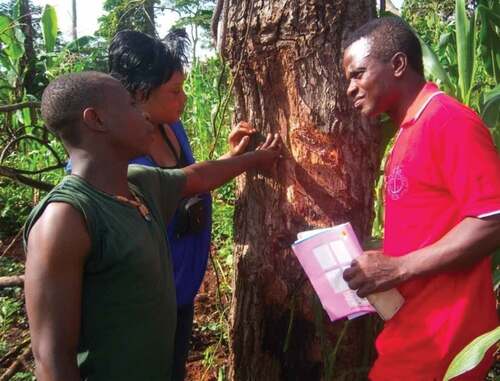

One participant emphasized the importance of the forest to the Pygmies: “The forest is our main source of livelihood since our lives are pegged on the hunting and harvesting of forest products. Everything we need is from the forest” (Respondent No. 19) (). Medicinal plants harvested from the forest is used for healing and provide supplementary income to the families of traditional healers. Logging has resulted in the loss of several medicinal plant species and the various transformations experienced by Baka societies have led to a slowdown in the process of the transmission of this ancestral knowledge from generation to generation. Changes in their traditional forest-based hunter-gatherer livelihoods and culture have led to changes in their health situation since access to forest resources has been restricted. They have been forced to abandon a forest-based lifestyle, and have become landless and impoverished conservation-refugees (see Cernea & Schmidt-Soltau, 2003). The displacement engendered by the introduction of development projects such as the creation of road infrastructure, national parks, and protected areas as well as deforestation is marring their livelihoods. Bagyeli communities on one edge of Campo Ma’an National Park are squeezed between the conservation area and land handed over to multinational companies for logging.

Pygmies are reputed for failing to attend primary healthcare services as well as existing health facilities including at Ngola 35 because of their inability to pay for consultation and medication. Furthermore, they lack the necessary identity documents for care consultations and face humiliating and discriminatory treatment from hospital staff (Egbe, Citation2012; Hewlett, Citation2006). A further factor hindering healthcare access is the Baka’s inability to speak the French language.

Besides the problem of child malnutrition that is common to all Baka settlements, skin diseases affecting both children and adults are the most widespread conditions in some settlements (see Pan-American Health Organization Citation2002, p. 181). Despite their proximity sometimes to the health centers in Bantu villages, Baka women give birth in the camps without assistance from trained healthcare personnel. This echoes the situation of ethnic minorities in Viet Nam where more than 60% of childbirths take place in the absence of prenatal care. This contrasts sharply with 30% for the majority ethnic group – the Kinh population (WHO, Citation2003, p. 10). Similarly, at a circumcision ceremony involving 10 children, the same traditional knife was used to circumcise all the participants. Such practices carry the risk of infection from many infectious diseases including the transmission of HIV and hepatitis B.

Several of the health care programmes put in place by missionaries, NGOs, logging companies and other development agents have trained Pygmy primary healthcare workers, established community dispensaries, and health centers. More Pygmy communities are now aware of free government health services, and the negative attitudes of health staff in some cases are beginning to change. Some Pygmy women conceded that they receive antenatal vaccinations and their children got one or more of polio, TB and measles vaccines. Some NGOs have taken upon themselves to invest in housing and sanitation, which should reduce illness. In addition, others have gone a long way to train some Pygmies so that they can act as intermediaries between the NGOs and the local people. Furthermore, by so doing convince their fellow Pygmy to embrace modern health care facilities. A missionary and schoolteacher recommended:

The experience gained from these initiatives indicates that health services for Pygmy people should incorporate both mobile and sedentary strategies, including methods of community-based health provision involving traditional healers who are accountable to communities and have their trust.

Pygmy peoples’ health situation is also affected by the negative stereotyping, exclusion and subjugation they encounter from their neighbours – the Bantus and dominant society. The Baka have half the life expectancy for other Cameroonians and are on the verge of extinction from preventable diseases. Sexually transmissible diseases (STDs) including AIDS have not spared the Pygmies (Pemunta, Citation2013). This is one effect of the gradual opening of the Pygmies’ habitat to ‘‘modernity’’ (increased contact with Bantus and people from the outside) and the superstitious belief that having sex with a Pygmy provides therapy against HIV/AIDS. The spike in the rate of HIV prevalence is compounded by lack of concerted measures to provide medical care to diagnosed HIV patients. Between 1993 and 2003, the rate of HIV infection in Pygmy communities skyrocketed from 0.7 percent to 4.0 percent (Tchoumba Citation2005). In addition, the cost of treatment with antiretroviral drugs is certainly not within reach of the Pygmies who lack the financial means. They frequently suffer from common treatable health issues such as malaria, diarrhea, worms, (high intestinal parasite loads), cough, leprosy, conjunctivitis, tuberculosis as well as STDs (Pemunta, Citation2013). The spike in the spread of STDS and HIV is partly due to the influx of migrant labourers employed by logging companies, road construction and infrastructure projects in the Pygmy´s environment (Egbe, Citation2012; Pemunta, Citation2013; Tchoumbe, Citation2005). The susceptibility of indigenous people to poverty-induced diseases has been well documented (Egbe, Citation2012; Hanley, Citation2006; Kenrick & Lewis, Citation2001; Ohenjo et al., Citation2006; Pemunta, Citation2013; The Indigenous World, Citation2006). Children and pregnant women are particularly vulnerable to malnutrition and anemia that are exacerbated by the breakdown of traditional food sharing mechanisms. One of the leading causes of childhood mortality in Pygmy communities is measles, which accounts for 8–20% of the deaths of Pygmy children (Egbe, Citation2012).

Most communities cannot access healthcare due to lack of availability, lack of funds and humiliating ill-treatment. Vaccination programmes can be slow to reach forest peoples and there are reports of medical staff discriminating against ‘Pygmy’ people. This poor treatment by medical personnel speaks to the fact that development initiatives intended to improve the livelihood of the Pygmies is instead negatively affecting and hence marring the health of Pygmy women and children in particular and the health of Pygmy communities in general. A central factor behind many of the problems faced by Pygmies is racism. Their social structures are often not respected by neighbouring communities or international companies and organizations, which value strong (male) leaders. ‘Pygmy’ communities who have lost their traditional livelihoods and lands find themselves at the bottom of ‘mainstream’ society.

Factors impeding service delivery among the Baka

The aim of development is to alleviate poverty and improve living standards as well as ensure effective participation and contribution to socio-economic, cultural and political life within a community (Sen, Citation1999, United Nations, Citation1986). According to Article1 (1) of the Declaration on the Right to Development ‘‘…development is an inalienable human right by virtue of which every human person and all peoples are entitled to participate in, contribute to, and enjoy economic, social, cultural and political development, in which all human rights and fundamental freedoms can be fully realized’’. Similarly, Article1 (2) states that:

‘‘The human right to development also implies the full realization of the right of peoples to self-determination, which includes, subject to the relevant provisions of both International Covenants on Human Rights, the exercise of their inalienable right to full sovereignty over all their natural wealth and resources’’(United Nations, Citation1986).

Worldwide indigenous communities are subjects of development projects meant to provision social services and to improve their livelihoods and socio-economic wellbeing. These projects often violate their rights and fail to meet their needs thereby driving them deeper into abject poverty, inequality and greater marginalization from the mainstream society (Hanley, Citation2006; Ohenjo et al., Citation2006; The Indigenous World, Citation2006; WHO, Citation2007). The lack of access to culturally appropriate healthcare among the Pygmies resonates with that of indigenous peoples in the developed world where they experience significantly shorter lifespans than their non-indigenous counterparts. The same scenario holds sway for aboriginal people in Canada, Australia, and the United States. ‘‘In Australia, the gap is as much as 20 years’’ (The Indigenous World, Citation2006, p. 10). ‘‘One-third of indigenous people in the United States live below the poverty line, as compared to one-eighth of the mainstream US population’’ (Ibid). The exoticization and Orientalization of the Pygmies is tantamount to treating the ‘margin’ as a tourist (Spivak, Citation1988a, p. 153). Since the subaltern Pygmies cannot speak, their voices are silenced when it comes to service delivery. They are refused the right to be different in terms of educational and healthcare services that are at least adapted to their indigenous lifestyle and culture.

Service delivery from a paternalistic perspective

Although interactions with their Bantu neighbours and outsiders have shaped the identities and livelihood systems of the Baka Pygmies thereby making classifications such as ‘‘hunter-gatherers’’ and farmers as references to them and Bagando people out of place (Fritzgerald, Citation2011; Lueong, Citation2017), they continue to be perceived as a culturally homogenous group by state and missionary and conservation organizations. Such distinctions, we argue, have above all, ‘‘led to the failure to recognize the distinctiveness of each group’’ and serves as an obstacle to an adequate understanding of the unique identities and experiences of each group (Fitzgerald, Citation2011, p. 30). A static view of society perpetuates dangerous and misleading perceptions that tend to misrepresent the lifeworlds of particular groups of indigenous people. We must see them inside as well as outside of their communities, as open to, and as affected by external influences, using a local-global perspective. Intensive commercial logging has for instance given rise to an unprecedented influx of outsiders – whose detrimental activities threaten the environment and lifestyle of the Baka Pygmies (Usongo & Nkanje Citation2004:121). The culture of the Baka is not a given, homogeneous, monolithic and geographically circumscribed, on the contrary, culture is dynamic (Scuzarello, Citation2008, Stolcke, Citation1995 cf. Eliassi, Citation2013, p. 34).

A paternalistic view constraints their freedom and expresses the superiority of development agents and agencies. It tends development interventions into rescuing and ‘corrective projects’ that are informed by the view of culture as cast in stone, as unchangeable and fixed (Eliassi, Citation2013, p. 34) whereas culture is dynamic. Among the Baka Pygmies, changes including the building of houses and sedentarization are taking place. This contradicts the representation of Pygmies as people living in huts constructed of leaves. Some Pygmies are now living like their Bantu neighbours who inhabit houses built with corrugated iron sheets. As a group, they have however maintained their activities of hunting and gathering and continuously shuttle between the forest and their roadside camps. This representation of the Baka resonates with orientalism as consisting of discourse about subaltern groups as a monolithic entity that is void of internal disparities and heterogeneity. As a form of culturalism, paternalistic Orientalist representations are characterized by the stereotypical portrayal of the cultures and societies of subaltern groups, overgeneralization, and misrecognition of these groups in essentialist modes (Radhakrishnan, Citation2012, see also Eliassi, Citation2013, p. 34).

The refusal of the Baka’s right to be different

The inferiority/superiority complex that underlies the relationship between the Baka Pygmies and outsiders/the development alliance (development agents, conservation organizations and the State) and suggests the need to rescue the former from the bush and march them towards modernity in the name of benevolence is misplaced and has significantly undermined development initiatives and the delivery of services targeting them. An NGO representative working with the Pygmies stated: ‘‘Although the Pygmies have come out of the forest, they have not completely abandoned the bush.’’

In line with Michel Foucault (Citation1975), as acts of ‘‘normalization’’, development initiatives comprise of dividing practices involving disciplines including social work has portioned out the world and its inhabitants into different categories regarding the normal and the pathological. Apart from classifying people, they are also situated within a development hierarchy, discourse and degree of deviancy (Pemunta, Citation2018a, Chambon, Irving & Epstein, Citation1999, Eliassi, Citation2013, p. 36). Change agents should be conscious of the fact that the Pygmies are different – they have different needs and aspirations than those being imposed on them in the name of development. The development alliance has refused the Pygmies the right to be different to other people (Abega, Citation1998). In other words, development has become analogous with the refusal to appreciate cultural differences and the right to be different. This is evident by the fact that although the Pygmies are comprised of diverse groups of people regarding their livelihood trajectories, they are lumped together by development brokers and agencies and a one-size-fits-all development blueprint is applied to them. As Foucault concedes, normalization is one significant component of the exercise of power. It totalizes/homogenizes groups and dissolves differences “gaps and levels between groups” (Rabinow, Citation1984) to enable interventions to adjust the Baka to a blueprint that reflects the “good [mainstream Cameroonian] society” (Eliassi, Citation2013, p. 36). Similarly, development aid targeting the Pygmies are laced with power by its conditionality (stop being yourself) and be assimilated into a neoliberal ideological programme (see Kapoor, Citation2004, p. 634) with the aim of ensuring capitalist penetration (Harvey, Citation2005).

Implicit in the lack of the right to be different is lack of community participation and ownership of projects (Sen, Citation1999, United Nations, Citation1986). It suggests planners have failed to engage the Pygmies so that they see infrastructural projects including boreholes in their communities as theirs – and continuously maintain same. Their thinking might well be that developers will come back to help maintain it for them. This feeds into the orientalist discourse that frames the Pygmies as backward and unfit for the modern world. By constructing the Baka Pygmies as ‘‘different/deviant’’, ‘‘backward and traditional communities’’ whose voices do not matter, they are subjected to colonial fantasies of a civilizing mission within mainstream Cameroonian society (see Eliassi, Citation2013:37, Mulianari, Citation2007, Dube, Citation2009). The representation of Pygmy communities as ‘‘underdeveloped’’ and ‘‘poor’’ helps in justifying for as well as in the reproduction of bureaucratic red tape and power (Ferguson, Citation1990:256; Kapoor, Citation2004, p. 634).

What the Pygmies expect from development agencies is not what is on offer for them. They want their voices heard, and not to be imposed upon. ‘‘Baka Pygmy groups want to be part of what is happening in [their community]’’(Egbe, Citation2012, p. 3). They are demanding a participatory and not a top-down approach to their integration and development, as is the case with some NGOs working in the community. The failure to incorporate Baka ´Pygmies´ views in the conception, execution, and evaluation of their development and integration needs has led to the failure of many projects in their communities. This failure has exacerbated socio-economic disparities as well as disparities in indigenous people´s health when compared with their immediate neighbours. Current approaches do not correspond to the needs, priorities, and expectations of indigenous communities (Egbe, Citation2012:4; United Nations, Citation1996:45; Ughi, Citation2012:23; Sen, Citation1999).

Recommendations and implications for social work practice

Worldwide, members of indigenous communities lag behind regarding healthcare access, education, agriculture and other social services that negatively affect their socio-economic wellbeing. In addition, human development indicators, demonstrate that compared with national indicators or members of mainstream society, indigenous communities are worse off. When programmes and policies are constantly rolled out for them, their views and considerations are often ignored. Indigenous communities suffer structural discrimination. They are blamed for being ‘‘primitive’’ and requiring just a dose of modernity to come out of the bush into mainstream society. Profoundly entrenched poverty – less than 1USD a day (Egbe, Citation2012), difficulty with access to land, education, and healthcare are daily realities among the Pygmies. How should effective service delivery from an indigenous perspective look like?

The apparent failure of various service delivery interventions geared at modernizing and lifting the Pygmies out of poverty suggests the need for social workers to be wary of – and not to reproduce the subordinated position of minority groups by promoting racist practices as well as to refrain from perceiving the social problems of subaltern groups ‘‘mainly as a consequence of their cultural backgrounds’’, while glossing over the structural inequalities and experiences intact (Eliassi, Citation2013:42; Dominelli, Citation1997). This imposes the need for reflexivity and awareness of paternalistic colonial and Oriental legacies. Moreover, development interventions should be perceived as a form of empowerment for minority groups (Eliassi, Citation2013; United Nations, Citation1996:45; Ughi, Citation2012:23; Sen, Citation1999). The way forward is to refrain from pathologizing minority groups such as the Pygmies and justifying oppressive development interventions. In line with the culturalist paradigm, the integration of the Pygmies is perceived as an evolutionary process that should facilitate their entry into modernity that would also allow them to claim an equal subject position (Razack, Citation2008 cf. Eliassi, Citation2013, see also Spivak, Citation1988, Citation1995, Citation1999) in mainstream Cameroonian society.

Effective and successful service delivery targeting Pygmy communities will be achieved through the decolonization of the racist epistemology that underpins development thinking and practice among these peoples. They are apparently victims of institutional racism from both their Bantu neighbours and mainstream Cameroonian society. The values, policies, practices, and institutions of the macro Cameroonian society tend to disadvantage the former. Within such an institutional framework, the mainstream society´s world sense, beliefs, practices, and values become the uncontested normative blueprint against which others are compared – whose values are constructed as inferior, pathological and deviant (Quinn, Citation2009, Dube, Citation2009) and which needs to be fixed through normalization (Foucault, Citation1975). This decolonization process requires epistemic social justice.

Healthcare and educational services can be brought closer to the Pygmies through the provision of mobile clinics in indigenous communities. They should also be given a voice, be allowed to define their needs and priorities. The paper suggests the need for a more culturally appropriate vision of development/service delivery for the Pygmies within their culture/communities. That is ‘‘a vision of listening to the people’’, development that is ‘‘friendly’’ and that ‘‘expands real freedoms that people enjoy’’ (Sen, Citation1999, p. 36), that takes account of their cultural particularities and identity (Olivero et al., Citation2016). Inadequate definition of indigenous identity contributes to the group´s marginalization, inadequate data for their numbers, health and socio-economic circumstances. This variance creates discrepancies, that not only hinders integration and development but also pushes them further away from a mainstream society that keeps on rejecting, labeling and discriminating against ´Pygmy´ people as observed in their [daily] interactions with the Bantus(Egbe, Citation2012:3; Olivero et al., Citation2016).

References

- Abega, S. C. (1998). Pygmées Baka, le droit à la différence; Yaoundé, Inades.

- Abéga, S. C., & Logo, B. P. (2006). La Marginalisation des Pygmées d’Afrique Centrale. Paris, France: Maisonneuse & Larose, Afrédit.

- Alcoff, L. (1991). The problem of speaking for others. Cultural Critique, 20, 5–32. doi:10.2307/1354221

- Ayele, F. (2017). Missionary education: An engine for modernization or a vehicle towards conversion? African Journal of History and Culture, 9(7), 56–63. doi:10.5897/AJHC2017.0371

- Aue, K, & Roosen, J. (2010). Poverty and health behaviour: Comparing socioeconomic status and a combined poverty indicator as a determinant of health behavior, Selected Paper Prepared for presentation at the 1st Joint EAAE/AAEA Seminar “The Economics of Food, Food Choice and Health” Freising, Germany, September 15 – 17, 2010, Available: https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/bitstream/116401/2/3A-1_Aue_Roosen.pdf Accessed June 15, 2018.

- Brah, A. (1987). Women of South Asian origin in Britain: Issues and concerns. South Asia Research, 7(1), 39–54. doi:10.1177/026272808700700103

- Brown, P. J., & Closser, S. (2016). The healing lessons of ethnomedicine. Understanding and applying medical anthropology.Brown and Closser New York, United States of America: Routledge. Third Edition.

- Cernea, M. M. (2000). Risk, safeguards and reconstruction: a model for population displacement and resettlement. In Cernea, M. M. & McDowell, C. (Eds.), Risk and reconstruction: Experiences of resettlers and refugees (pp. 11–55). Washington, DC, USA: World Bank.

- Chambon, A. S., Irving, A., & Epstein, L. (Eds.). (1999). Reading Foucualt for social work. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

- Cotera, M. E., & Saldaña-Portilloo, M. (2015). ”Indigenous But Not Indian”? Chicana/os and the politics of indigeneity. In R. Warrior (Ed.), The world of Indigenous North America (pp. 549–564). London/New York, United Kingdom/United States of America: Routledge.

- DfID. (2005). Reducing poverty by tracking social exclusion: A DfID policy paper. London: DfID (Department of International Development).

- Dominelli, L. (1997). Anti-racist social work. London, ENG: Palgrave.

- Doyle, C. (2009). Indigenous peoples and the Millennium Development Goals – ‘sacrificial lambs’ or equal beneficiaries? The International Journal of Human Rights, 13(1), 44–71. doi:10.1080/13642980802532341

- Dube, L. (2009). “ HIV and AIDS, Gender and Migration: Towards a Theological Engagement,” Journal of Constructive Theology, Volume 15, No 2, University of KwaZulu Natal, 71-82.

- Egbe, M. (2012). Social exclusion and indigenous people´s health: An example of Cameroon Baka ´Pygmies´ people of the rainforest region of the south. Sustainable Regional Health Systems, 1–6:18-23. Issue #1/May.

- Eliassi, B. (2013). Orientalist Social Work: Cultural otherization of Muslim immigrants in Sweden. Critical Social Work, 1, 33–46.

- Escobar, A. (1984). Discourse and power in development: Michel Foucault and the relevance of his work to the Third World. Alternatives, 10(10), 377–400. doi:10.1177/030437548401000304

- Ferguson, J. (1990). The anti-politics machine: Development, depoliticization and bureaucratic power in Lesotho. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

- Fitzgerald, D. (2011). Why KÙnda Sings: Narrative discourse and the multifunctionality of baka song in baka story. A dissertation presented to the graduate school of the university of Florida in partial fulfilment of the conditions for the award of doctor of philosophy degree.

- Foucault, M. (1975). The birth of the clinic: An archaeology of medical perception. New York, NY: Vintage.

- Harvey, D. (2005). A Brief History of Neoliberalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hanley, A. J. (2006). Diabetes in Indigenous Populations. Medscape Today.

- Hewlett, B. S. (2006). Aka pygmies of Western Congo basin. Accessed October 15, 2017. www.vancouver.edu.

- Ibeneme, S., Eni, G., Ezuma, A., & Fortwengel, G. (2017). Roads to health in developing countries: understanding the intersection of culture and healing. https://www.clinicalkey.com.au/service/content/pdf/watermarked/1-s2.0-S0011393X17300036.pdf?locale=en_AU

- The Indigenous World. (2006). International working group on Indigenous affairs.Eks-Skolens Trykkeri, Copenhagen, Denmark. https://www.iwgia.org/images/publications//IW_2006.pdf Accessed October 18, 2018.

- Joiris, D. V. (1994). Elements of techno-economic changes among the sedentarized Bagyeli Pygmies (South-West) Cameroon). African Study Monographs, 15(2), 83–95.

- Joiris, D. V. (1996). A comparative approach to hunting rituals among the Baka (Southeast Cameroon). In S. Kent (Ed.), Cultural diversity among twentieth century foragers: An African perspective (pp. 245–275). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Joiris, D. V. (1998). La chasse, la chance, le chant. Aspects du systeme rituel des Baka du Cameroun. These de doctorat, Universite Libre de Bruxelles.

- Kapoor, I. (2002). Deliberative democracy or agonistic pluralism? The relevance of the Habermas-Mouffe debate for Third World politics. Alternatives, 27(4), 459–487. doi:10.1177/030437540202700403

- Kapoor, I. (2004). Hyper-self-reflexive development? Spivak on representing the Third World ‘Other’. Third World Quarterly, 25(4), 627–647. doi:10.1080/01436590410001678898

- Kenrick, J., & Lewis, J. (2001). Discrimination against the forest people (´Pygmies´) of Central Africa. In S. Chakma & M. Jensen (Eds.), Racism against Indigenous People (pp. 312–325). Copenhagen, Denmark: International Working Group on indigenous Affairs(IWGIA).

- Lewis, J. (1999). Discrimination and success to healthcare: the case of nomadic hunter-gatherers in Africa. Msc dissertation, University of London, United Kingdom.

- Lueong, G. (2017). The forest people without a forest: Development Paradoxes, Belonging and Participation of the Baka in East Cameroon. New York, United States: Berghahn.

- Mann, J. (2006). Health and Human Rights If Not Now, When? American Journal of Public Health. 96(11): 1940–1943.

- McNeish, J & Eversole, R. (2005). Introduction: Indigenous Peoples and Poverty in Eversole, R, McNeish, J, and Cimadamore, A.D. (Eds.): Indigenous Peoples & Poverty: An International Perspective (pp. 1–26). London, United Kingdom: Zed Books.

- Mulinari, D. (2007). “ Kalla mig fan vad du vill, men inte invandrarföräldrar!” En skola för alla, eller? [Call me whatever you want, but not an immigrant parent!” A school for all, or?] In M. Dahlstedt, F. Hertzberg, S. Urban & A. Ålund (Eds.), Utbildning, Arbete, Medborgarskap [Education, work, citizenship] (pp. 189-212). Umeå, SE: Boréa.

- Ndtoungou, E. (1972). Rapport sur Ia situation generate des Pygmees de Ia prefecture de Kribi et sur Ia collaboration apportee a titre prive a leur promotion sociale et economique depuis 1952 (Yaounde).

- Ngima, M. G. (2015). Attempts at decentralization, forrest management and conservation in Southeast Cameroon. African Study Monographs, Supplementary Issue, 51, 143–156.

- Ohenjo, N., Willis, R., Jackson, D., Nettleton, C., Good, K., & Mugarura, B. (2006). Health of Indigenous people in Africa. 367(9526), 1937–1946. The Lancet, The Lancet Special Issue on Indigenous People.

- Olivero, J., Fa, J. E., Farfán, M. A., Lewis, J., Hewlett, B., Breuer, T.,Carpaneto, G.S., Fernández, M., Germi, F., Hattori,S., Kitanaishi, K., Knights, J., Matsuura, N., Migliano, A., Nese, B., Noss, A., Ekoumou, D., Paulin, P., Real, R., Riddell, M., Stevenson, EGJ., Toda, M., and Vargas, JM. and Mullaly, B. (2016). Challenging oppression: A critical social work approach (p. 232). Don Mills, Canada: Oxford University Press.

- Pan American Health Organization. 2002. Health in the Americas. Vol. 1, 2002, Scientific and Technical Publication No. 587, Washington: Pan-American Health Organization, Wahington, DC, United States of America.

- Pemunta, N. V. (2013). Governance of nature as development and the erasure of the Pygmies of Cameroon. GeoJournal, 78(2), 353–371. doi:10.1007/s10708-011-9441-7

- Pemunta, N. V. (2017). The logic of benevolent capitalism: The duplicity of sithe global sustainable oils Cameroon land grab and deforestation scheme as sustainable investment. International Journal of Global Environmental Issues, 17(1), 80–105. doi:10.1504/IJGENVI.2018.090655

- Pemunta, N. V. (2018). Fortress conservation, wildlife legislation and the Baka Pygmies of Southeast Cameroon. Geojournal. doi:10.1007/s10708-081-9906-z

- Pemunta, N. V.* (2018a). Introduction: Towards Global Connections and Multiple Entanglements, 1–20, Pemunta, NV. (editor), Concurrences in Postcolonial Research: Perspectives, Methodologies and Engagements. Hannover, Germany: Ibidem Press.

- Pemunta, N. V., & Mbu-Arrey, O. P. (2013). The tragedy of the governmentality of nature: The case of national parks in Cameroon. In D. Bigman & J. B. Smith (Eds.), National Parks: Sustainable development, conservation strategies, and environmental effects (pp. 1–46). Georgia, United States: Nova Science Publishers.