ABSTRACT

Community college students are an untapped reservoir of talent and including them in social work education aligns with the values of the profession. Yet these students encounter formidable obstacles on the path from a 2-year degree to an affordable social work degree. In this article, we describe the systems thinking underlying a newly instituted Bachelor of Social Work completer program and how this approach was used to address barriers posed by the transfer process. Such an analysis reveals ways to intervene and simplify the process. As our case illustrates, systems thinking sets the stage for social work education to be re-imagined as a national workforce pipeline rather than a collection of accredited programs at independent colleges and universities.

Most considerations of the continuum of social work education treat the Bachelor of Social Work (BSW) as the identifiable starting point. Associate programs—especially those in human services and social work, which the Council of Social Work Education (CSWE) does not accredit—are frequently overlooked, as are the thousands of students who begin their educational experiences at community colleges (Rempel, Citation2020a, Citation2020b). These students represent an untapped reservoir of talent (Glynn, Citation2019). Policy makers and administrators increasingly recognize that community colleges provide a practical option for a growing population of students from poor families (Fry & Cilluffo, Citation2019; Glynn, Citation2019). Indeed, federal leadership recently emphasized the value of a community college degree and promised to increase financial resources to these institutions (Jaschik, Citation2021). The inclusion of these students also aligns with social work’s central mandate to diversify, as many are poor, non-White, and the first in their families to attend college (National Association of Social Workers, Citation2021a). The lack of national supports conferred by CSWE accreditation limits the ability of associate programs to direct their students into BSW programs, which creates a piecemeal system of transfer agreements by local institutions. With few exceptions (Belliveau et al., Citation2019; Messinger, Citation2014; Neuman, Citation2006; Shank & Thornton, Citation2006), BSW programs have few incentives to interact with associate programs to facilitate the upward transfers of community college students. Most simply do not engage and the scant literature on such collaborations underscores the disconnection.

We posit this situation is a lost opportunity for the profession and propose a system-thinking approach (Meadows & Wright, Citation2008) as the means for social work educators and program administrators to address it. This article describes the iBSWFootnote1 completer program for community college students that the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (hereafter, Illinois) instituted in 2021. The development of this program led us to consider more fundamental changes to the entire BSW program—both on and off campus—that facilitated access by students in Chicago, its neighboring suburbs, and throughout the state of Illinois.

Systems-thinking 101

In her groundbreaking book Thinking in Systems: A Primer, Donella Meadows and Wright (Citation2008) defined systems as an interconnected compilation of elements—for schools, students, teachers, administrators—organized in such a way that they generate reliable patterns over time. Even when external forces affect how a system reacts, the responses reflect the system. For example, for most institutions, general enrollment patterns remained the same after the shift to online learning in 2020; student demographics remained substantially the same.

The Social Work Profession: Findings from Three Years of Surveys of New Social Workers reported that overall, 46% of new social workers are the first person in their families to graduate college; the rates are even higher for African American and Latino graduates (57% and 73%, respectively; Salsberg et al., Citation2020). Yet the persistent enrollment patterns in social work programs nationwide are troubling; students still tend to be predominantly female, White, and young. During the 2019–2020 academic year at Illinois, 52% of full-time students in the BSW and MSW programs and 69% of part-time MSW students identified as White. Women dominate all three groups, constituting at least 86%. Full-time BSW students are largely 22 or younger (81%); full-time MSW students are mostly under 24 (64%), and part-time MSW students are chiefly 25 years or older (82%). To the extent that Whiteness correlates with resources, the racial and age makeup of the BSW and MSW student bodies reflects an institutional fit between programs that offer mostly in-person courses during the business hours of the work week and those individuals who want to attend class during those times. These students need to be (mostly) unencumbered by family or work obligations and, unless they already reside in Urbana-Champaign, financially able to relocate to a new city for the duration of the program. Over time, structural arrangements that support this dynamic have become instituted and mutually reinforcing. Faculty and students expect certain time schedules for classes. Even the types of supports offered to students reflect these preconceived arrangements. Administrators and faculty address classroom accommodations related to learning disabilities but not affordable childcare, because our programs attract students who have postponed childrearing for the duration of the program. Thus, despite targeted recruitment efforts for specific populations, enrollment patterns have not changed significantly.

Systems thinking is a holistic approach that explains how elements of a system interact to produce specific outcomes over time (Hassan et al., Citation2020), such as the makeup of a program’s student body composition. Although there are other approaches that seek to illuminate structures that contribute to the status quo, such as critical pedagogy (Saleebey & Scanlon, Citation2005), systems thinking is particularly useful in figuring out which parts of the system contribute to a problem and which parts, if leveraged, might lead to better outcomes (Gallagher et al., Citation1999; Luke & Stamatakis, Citation2012; Mabry & Kaplan, Citation2013). For example, critical pedagogy has limited utility for addressing social problems embedded in complex systems, although it holds that the revelatory process may be personally liberating for those involved in the analyses (Saleebey & Scanlon, Citation2005). Systems often interact in ways that produce an emergent effect that differs from what each component intends and that persists over time (Luke & Stamatakis, Citation2012). A systems-thinking approach begins with an analysis that seeks to identify root causes within the system that support problematic outcomes; by taking this approach, educators and program administrators can devise enduring solutions through structural changes (Leischow et al., Citation2008; Meadows & Wright, Citation2008).

Systems-thinking concepts

Several concepts from systems thinking are particularly relevant to this discussion. First, complex problems are not static; rather, they arise within situational contexts made up of stakeholders from various institutions that both empower and constrain action (Kingdon, Citation1995; Lamphere, Citation1992; Staller, Citation2010). As such, problems are best understood, not as freestanding, but rather as problem situations. Second, the resolution of problem situations necessitates cross-sector collaborations, a feature widely recognized as a best practice for enacting social change (De Montigny et al., Citation2019). However, vested interests frequently stymie cross-sector collaborations (Rempel, Citation2020a; Sowl & Brown, Citation2021). Thus, it is useful to consider the context and how each stakeholder operates within it, which brings us to the third salient concept—bounded rationality—in systems thinking. Nobel laureate economist Herbert Simon (Citation1972, Citation2000) first coined this term to convey how “good enough” decision making occurs within contexts of information, incentives, pressures, goals, and discrepancies.

Bounded rationality explains that people are motivated to enhance their outcomes within a given context, without regard to how those actions might affect others in different institutional settings that are nonetheless part of a larger system. This perspective helps explain why lawyers, human resource administrators, and financial officers are generally more conservative and rule-orientated than faculty and students who operate within the very same university; their immediate work situations influence their day-to-day choices as they seek to maximize their outcomes. Faculty and students are encouraged to take intellectual risks, while their colleagues are taught that avoiding risk is optimal.

Actions based on bounded rationality create a feedback loop within the system that reinforces behaviors, a fourth concept from systems thinking. For example, teachers and administrators, interested in well-regulated classrooms, might suspend a student who repeatedly misbehaves. The suspensions serve as an appropriate disincentive for students who are reasonably engaged with their education and to stabilize situations in which extreme acting-out behaviors threaten to disrupt learning. However rational, this practice is a short-term fix. Students who are academically disengaged and unmotivated might be more inclined to act out to obtain a break from school, and thus to increase disruptions (Maag, Citation2012). In this case, all interested parties are behaving rationally; they are trying to maximize their interests without considering the consequences down the line. Addressing this problem requires the cooperation of teachers, administrators, and students to agree on a given objective and devise clear implementation plans for the short, intermediate, and long term.

Thus, when a system is analyzed from a systems-thinking perspective, we consider the context, which gives rise to the problem situation, shapes and constrains stakeholder actions, and supports feedback loops. These deliberations help us identify what Meadows and Wright (Citation2008) called “bottlenecks” and “leverage” points within the systems that influence the movement of processes in the direction of a desirable outcome. Bottlenecks stymie the flow of processes. Leverages can be enhanced to improve them. Finally, we consider the resulting mental models that support and maintain the status quo.

Mental models that support the status quo

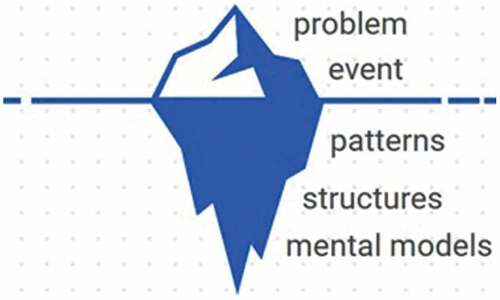

Systems thinking seeks to identify a system’s underlying structures and the conceptual frames—mental models—that support them; that is, assumptions and beliefs about appropriate behaviors and outcomes. illustrates the classic iceberg structure of a problem that arises within a complex system. The iceberg’s tip, shown above the waterline, represents the highly visible problem situation and the spotlighting event that garners focused attention and interventions, usually with partial successes.

Underneath the water’s surface are patterns that contribute to the problem, and even deeper, the structures and mental models that support the undesirable outcome. Arguably, structural changes will go much further to address the problem than interventions aimed at the tip of the iceberg. Consider, for example, the challenge of recruiting and retaining historically underrepresented students, many of whom are also economically disadvantaged, to institutions of higher education, particularly selective ones. Underrepresentation is the tip of the iceberg, visible for all to see. Just below the surface are longstanding patterns that contribute to the problem: prospective students’ lack of knowledge about the benefits of attending a selective institution, how to complete a successful application, and how to obtain funding. Common fixes are aimed at disseminating such information (e.g., through campus visiting programs and summer institutes) and providing financial aid to targeted students. Such approaches certainly benefit numerous students but address only the least troublesome structural barriers. From a systems-thinking perspective, they are superficial. Students with overstretched attentional bandwidths—those working full-time jobs, managing caregiving responsibilities, and struggling with serious economic insecurities—remain unsupported because their problem begins much earlier in the system: before they even consider applying in the first place (Mullainathan & Shafir, Citation2013). Encumbered with competing demands, these students might overlook program campus-visiting programs and summer institutes that would facilitate the submission of competitive applications. Such students may need multiple entry points of admission and numerous institutional contacts to create a sense of belonging and confidence that they can succeed in a selective school. As most admission processes are intentionally competitive, many educators and program administrators would never imagine facilitating an application though institutional mentorship.

Mental models that support the perpetuality of existing policies and procedures impede structural change through the unquestioned assumptions about whether (and if so, how) universities should enact such changes in the first place. Mental models support the way the system is arranged and contribute to its persistence. For example, those with influence over recruitment strategies may believe that the kinds of accommodations nontraditional students need makes them a poor fit with their specific institution. Statements and questions that support this thinking include “this is how it’s always been done,” “not a good fit,” “are we lowering our standards?” or “this is not the way we do things.” Recruitment efforts and admission processes come to reflect these preconceptions and, over time, if left unexamined and unchallenged, hamper the creation of structures that support diversification of the profession.

The problem situation of upward transfers

Three situational contexts impede the upward transfer of community college students into BSW programs. First, the evaluation and transfer of credits from one institution to another, across numerous programs and degrees, can inhibit transfer in general (Belliveau et al., Citation2019; Messinger, Citation2014). Credits lost in the process generate additional penalties for transferring students in overall time to degree and debt accumulation (Belfield et al., Citation2017; Xu et al., Citation2018). Second, unlike 4-year degree institutions, community colleges serve many students who are economically and educationally disadvantaged but within a context offering numerous degree types (Worsham et al., Citation2021). Because community colleges provide educational opportunities for students with varied interests, including those pursuing technical careers and workforce training, the preparation of students to transfer into a 4-year program represents only one of multiple objectives. In social work, the presence of the human service degrees—which contain content that overlaps with social work, frequently are unaccredited, and vary greatly across institutions—further complicates the transfer process (Belliveau et al., Citation2019; Berg-Weger et al., Citation1999; Messinger, Citation2014). Human service degrees focus on knowledge and skills to meet workforce needs and generally do not direct community college students to complete the general education requirements that will foster transfer into a BSW program (Berg-Weger et al., Citation1999; Messinger, Citation2014). Third, community college students face competing demands for their time and attention that may make the attention to detail required to fulfill transfer requirements difficult (Jabbar et al., Citation2021; Mullainathan & Shafir, Citation2013; Wood et al., Citation2016). All three of these types of problems compound over time and are mutually reinforcing, requiring the cooperation of multiple stakeholders across various institutions to address (Belliveau et al., Citation2019; Blaylock & Bresciani, Citation2011; Sowl & Brown, Citation2021; Wheeler, Citation2019; Worsham et al., Citation2021).

Yet interinstitutional collaborations can be challenging (Sowl & Brown, Citation2021), especially if stakeholders fail to appreciate the institutional constraints that shape people’s perspectives. Pennsylvania’s success indicates the challenges. The state legislature began requiring statewide articulation agreements among its 4- and 2-year public institutions within each discipline (private institutions could opt in) in 2009 (Belliveau et al., Citation2019). This mandate created a structural context for interorganizational cooperation, but left the implementation plans up to each discipline. The social work team used CSWE’s Educational Policy and Accreditation Standards as the standard to evaluate course transfers across the varied academic units. At the time, Pennsylvania was seeking licensure for those holding a BSW degree, which encouraged community college administrators to align their associate’s degree with social work. While these strategic maneuvers generated consensus among diverse stakeholders, the situation also underscores the importance of working within the existing structural framework in systems. Most states do not have such statewide legislative mandates to motivate interinstitutional partnerships, and most states do not offer social work licensure at the bachelor level to incentivize the adoption of a specific set of standards. In the absence of such supports we used a different array of institutional leverages to clear bottlenecks in the transfer system and create a pathway for the upward transfer of community students at Illinois.

Community college students tend to be “nontraditional.” While there is no official definition, these students tend to delay their enrollment and are, therefore, older, more likely to have family obligations, work full time, attend school part time, and be financially independent compared to their “traditional” counterparts (Zack, Citation2020). They are also less likely to attend elite schools and flagship universities than other students (Zack, Citation2020). To facilitate their inclusion, we employed an analysis that goes beyond the superficial question How do we recruit historically underrepresented community college transfer students to the university? Rather, we asked, What systems are giving rise to the current student profile? We also asked, What existing leverages within the system can we use to facilitate the desirable outcome—the inclusion of community college students at a state flagship institution? What follows is a systems-thinking analysis that begins with Illinois. One of the most obvious sources of leverage was Illinois’s mission as a land-grant institution.

The land-grant institution

Established in 1867, Illinois is one of 37 public land-grant institutions created by the 1962 Morrill Land-Grant Colleges Act (University of Illinois, Citation2021b). It sits astride two midsize cities in central Illinois, about 140 miles south of Chicago, a location that befits Illinois’s status as the state’s flagship university and as a large research-intensive institution, renowned for its residential undergraduate programs and world-class graduate programs. To fulfill its land-grant objective, Illinois hosts an extensive extension system—a statewide network of educators, faculty experts, and staff located within freestanding units throughout the state—to disseminate research findings (University of Illinois, Citation2021d). But this system does not encompass the delivery of degree-granting academic programs. Indeed, despite the growth of distant learning programs nationwide, Illinois’s undergraduate academic programs remain largely campus-bound.

As of this writing, the university offers only one entirely online bachelor’s degree (the iBSW program is its only hybrid program), and the effects on student demographics are what we would expect. The typical student at the University of Illinois will be enrolled full time, most likely White or Asian, and young. The average age of the 7,530 newly admitted freshmen in 2020 was 18.5 years (University of Illinois, Citation2020). The majority (99%) were full-time students and mostly White (38%) or Asian (23%). These figures reflect a common profile of incoming students at flagship state universities. A systems-thinking approach asks: What are the reliable patterns of inclusion and exclusion?

Land-grant institutions were intended as resources for the residents and communities of the states that provided the land, which means an explicit commitment to educate working-class people regardless of their background or income level (University of Illinois, Citation2021a). There is hardly any other organization in higher education more suited to spearhead the active recruitment of community college students than the land-grant institution.

While the number of historically underrepresented students on campus at Illinois has steadily increased over the past decade, these students are, like the student body generally, overall young, single, able to live on or near campus, and with no dependents. In this context, the newly instituted iBSW program, which allows for both online course completion and the fulfillment of the internship requirement in the student’s home community, was designed to introduce a different kind of student to the Illinois School of Social Work in line with its commitment to diversity, equity, and inclusion and the diversification of the social work profession.

Leveraging institutional ethos and existing structures

In 2019 Steve Anderson, dean of the Illinois School of Social Work, applied for an institutional grant to create the iBSW, which would be designed to serve community college graduates in the city of Chicago, its neighboring suburbs, and the five counties within Illinois that border Chicago’s Cook County, what we call here Chicagoland. In some usages, the colloquial term Chicagoland includes another nine counties in northeast Illinois, southeast Wisconsin, and northwest Indiana; focusing on Illinois counties aligns with the institution’s mission and the six included are the most populous counties in the state (Cubit, Citation2022; Office of Management and Budget, Citation2020).

Following the 2020 appropriation of the requested funds, Dean Anderson assembled a team of faculty, including administrators from both the campus BSW and MSW programs and the authors of this article, to structure its programmatic design. This 2-year completer program would enable community college graduates to pursue their Illinois BSW degree without relocating to Urbana-Champaign through a combination of online and hybrid classes and field placements near their homes.

Several factors served as leverage as we built the program. First, the program aligned with the institution’s mission and Illinois had existing structures that could support it. The Illinois School of Social Work’s field office has a long track record of placing our social work students in internships throughout Illinois, including in Chicagoland; we had reasonable assurance that we could do the same for our iBSW completer students. Furthermore, in keeping with the nationwide expansion of distance learning (Seaman et al., Citation2018), our faculty were increasingly proficient in online teaching. Several hybrid and fully online BSW courses had recently been developed; thus, efforts to make our BSW program available to off-campus students required only modest investment. Moreover, we had observed excellent BSW completion outcomes among community college transfers to Illinois, and instructors had learned what a pleasure these students were to teach. This observation is consistent with research indicating that community college students who transfer to selective institutions have equal, and in some cases higher, graduation rates as those who enroll directly from high school or who transfer from other 4-year institutions (Glynn, Citation2019). Unfortunately, they also represent less than half of all transfer students at selective institutions (Glynn, Citation2019). At Illinois, available data between 2016 and 2019 show that only 164 Chicago community college students transferred to Illinois in total. These strikingly low numbers suggest the presence of structural impediments.

Structural impediments

While community college represents a critical entry into higher education for many students, those who start their postsecondary education at these institutions differ from our traditional campus students in fundamental ways. Nearly half are 24 or older, and 28% have children or other dependents (Community College Research Center, Citation2021). About two-thirds attend community college part time, and nearly 60% are financially independent (Community College Research Center, Citation2021).

Community colleges also attract many students from historically underrepresented backgrounds (Community College Research Center, Citation2021; Fry & Cilluffo, Citation2019). Nationwide, Black and Latino students comprise 41% of community college students but only 30% of students enrolled in 4-year institutions. In urban areas, these numbers are much higher. The City Colleges of Chicago (CCC, Citation2021) system reported a 2020 enrollment of 67,890 students across three instructional areas: adult education, continuing education, and semester credit; more than three-quarters identified as either Hispanic (49.3%) or Black (25.9%). These figures coincide with a recent analysis by the Pew Foundation that found a marked increase of poor and minority undergraduates in public 2-year colleges (Fry & Cilluffo, Citation2019).

Many community college students have substantial personal, work, and family obligations; degree completion rates at these institutions remain alarmingly low. In 2018, CCC reported a 24% graduation rate. The transition to baccalaureate programs is also problematic. More than one-fifth, 21%, of Chicago public schools students enrolled in a 2-year community college but only one-third of these went on to complete a bachelor’s degree; very few would finish their degree within 6 years and only about a quarter who began community college earned a credential of any kind (Nagaoka et al., Citation2020). National statistics show similar patterns (Chen et al., Citation2019). According to the Community College Research Center, the loss of credits upon transfer serves as the biggest obstacle to bachelor’s degree completion; those students who transferred nearly all their credits were 2.5 times more likely to earn a bachelor’s degree than those who transferred fewer than half their credits (Jenkins & Fink, Citation2015). For many community college students, the prospect of attending the state’s flagship, with its residency and general education requirements, to complete a bachelor’s degree is inconceivable, let alone attend graduate school. Additional barriers may include lack of formal/informal mentoring, lack of social–emotional support and guidance, cost of tuition and housing, access to financial aid, knowing and completing the general education requirements, and a cumbersome and challenging application processes. A systems-thinking approach helped us see how various factors interact to produce these outcomes in our context as well as throughout the country.

The importance of an iBSW program at a selective university

To those overseeing the Investment for Growth Program, executed from the Office of the Provost, the appeal of an iBSW completer program resonated with the identified need to, in the words of their webpage, “invest discretionary resources … to address the changing demands of a premier land-grant institution” (University of Illinois, Citation2021e). The iBSW would extend Illinois’s effect by preparing bachelor-level social workers who would serve in community-based social service agencies throughout the city and state. The need for an iBSW program as an entrée for Chicagoans into the profession could not have been clearer; a systems-thinking analysis reveals interinstitutional gaps and far-reaching implications for the presence of such a program.

In a crowded field of Chicago-based institutions of higher education, only one public institution and two private institutions host accredited BSW programs to serve a population of 2.7 million within the city alone (CSWE, Citation2021). If we expand the boundary to Chicago’s neighboring suburbs and collar counties, we gain six more programs, five of which are private. In this context, we anticipated that community college students would welcome the iBSW completer program as an affordable and selective program. Moreover, the Chicagoland region would benefit from more social workers from diverse populations.

Illinois is among the most selective universities in the state. It is also one of the most affordable, with the most robust financial aid program in the state. Illinois residents from families with annual incomes of $67,100 or less and who have fewer than $50,000 in assets receive full coverage of comprehensive financial aid to cover the cost of tuition and fees (University of Illinois, Citation2021c, Citation2021f). The program does not cover room and board, but students in the iBSW completer program would avoid these costs. These features—affordability and the flexibility to remain at home—would enable Illinois to extend the prestige and status associated with its institutional brand to those who have clearly found them inaccessible.

The value of a BSW degree

The BSW sets the stage for an affordable graduate education; prospective students who graduate with a BSW from a CSWE-accredited program are eligible to enroll in an advanced-standing MSW program (CSWE, Citation2010; Social Work Degrees, Citation2022), which translates into substantial cost savings in tuition and time, and increased earning potential over the lifetime. Education to Social Work Practice: Results of the Survey of 2018 Social Work Graduates reported that 59.6% of the BSWs in the United States who graduated in 2018 were enrolled in an MSW program a year later (Salsberg et al., Citation2019). Yet efforts to increase diversity, equity, and inclusion within the profession rarely focus on BSW programs as affordable pathways to the profession’s terminal degree. For example, the reference to social work education that appears in the National Association of Social Workers’s (Citation2021b) report Undoing Racism Through Social Work focuses only on student debt—a vital issue, but nonetheless, the tip of the iceberg. Through the iBSW program we sought to provide a broader systematic approach.

The lack of affordable BSW programs in the Chicagoland region impedes the cultivation of future MSWs from diverse backgrounds, not least because community college students may not understand the benefits of completing a BSW as an affordable entrée to a professional degree. Access to an affordable BSW degree mitigates debt accumulated from social work education, which remains unacceptably high and is particularly pronounced among historically underrepresented groups (Salsberg et al., Citation2020). Salsberg et al. (Citation2020) observed that the starting salary for new MSWs averages $47,100, but educational debt among recent MSW graduates hovers at about $66,000, of which $49,000 was generated in the pursuit of a social work degree. These patterns also reflect racial disparities; while White MSWs averaged $45,000 in debt, African American MSWs carried debt of around $66,000 (Salsberg et al., Citation2020). Similarly, Hispanics averaged $53,000, while non-Hispanics averaged $48,000. Some of these disparities can be attributed to institutional choice. MSW graduates of private, nonreligious schools carried an average of $61,000 in social work education debt, while graduates of both public and religiously affiliated social work programs carried an average of $33,000 (Salsberg et al., Citation2020).

Two other statistics underscore the need to reimagine social work education as a nationwide pipeline rather than a collection of accredited programs across institutions. First, social work is a growth industry. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (Citation2021) estimated that between 2019 and 2029 the employment of social workers will grow by 13%, a rate faster than the average growth expected in other occupations. Second, there is a growing need for behavioral health services (Czeisler et al., Citation2020) and social workers are the major providers of such services (Salsberg et al., Citation2019). In a survey conducted in 2018, 26% of new MSWs indicated that providing mental health services was the primary focus of their job and nearly 66% reported that they provided mental health services to a majority of their clients (Salsberg et al., Citation2019). In the following section, we describe the pipeline approach we employed to structure the iBSW program and its practical implications for our students and for others in the state.

Structuring the iBSW program

Although a systems-thinking approach provides insights into problem situations and highlights institutional leverage points, the actual implementation of “good enough” solutions requires ongoing modifications as the needs of stakeholders become increasingly clear. As a starting point, the developers of iBSW began monthly meetings to design the program, garner broader faculty support, and solicit the necessary approvals from the university senate.

We recognized immediately that our iBSW program would need to reach community college students well before the application stage, and that once admitted into the program, they would need a sense of intellectual and institutional belonging. We envisioned the creation of formal, established “corridors” that moved students from community college through the completer program to graduation, and into the job market or an advanced-standing MSW program. Faculty and program administrators, including the authors, began weekly meetings to discuss how we would accomplish this objective and to engage stakeholders at community colleges in the Chicagoland region. We also hired on a part-time basis an alumna who had completed her BSW on campus as a community college transfer student and was preparing to graduate from our advanced-standing MSW program to provide a student perspective and assist us with marketing and outreach. Ultimately, we established ongoing relationships with administrators, faculty, program directors, transfer coordinators, and other administrators at seven different community colleges; devised protocols for proactive advising; and simplified the admission processes into our MSW programs.

The value of stakeholder feedback

Originally, we planned to offer hybrid classes at a location in downtown Chicago and market this program to community colleges throughout Chicago and its neighboring suburbs, as well as to human service agency employees with community college degrees. This plan mostly reflected Illinois’s institutional priorities. Campus administrators who were concerned that a strictly online program would dilute the Illinois brand found a hybrid model an acceptable compromise. Moreover, Illinois has access to two downtown Chicago locations that could host satellite classes; their proximity to public transit lines and major highway exits were considered ideal. The university approved the plan at the end of 2020.

Our community college partners expressed enthusiasm for the iBSW program, but they also shared their trepidations about the hybrid model. Repeatedly, they reminded us that their students needed course flexibility and cautioned against a downtown commute to attend classes, even on a part-time basis. Some offered classroom space on their campus to alleviate commutes.

It is instructive here to consider the travel issue from the perspective of bounded rationality. To Illinois administrators and faculty, a downtown commute seemed reasonable; in Champaign-Urbana, travel times average about 14 minutes from any given point to another. However, Chicago’s notoriously congested traffic patterns create a very different situation. We recognized that our community college partners would have a better understanding of what their students would be able to do. While we took their warning seriously, we are also wary of solutions that privilege one group over another, such as hosting classes at select community colleges. An understanding of bounded rationality helped depersonalize the issue, focused our attention beyond the needs of any community college, and motivated a search for other leverages to address the problem.

Researchers at the Illinois Office of Community College Research and Leadership echoed the concerns of our community college stakeholders and noted the appeal of online classes for community college students, whose demand tends to outpace supply (Fox, Citation2017). They cited various factors: Online coursework helps students balance multiple responsibilities by allowing them to self-pace the work, improve their time management, and avoid long commutes. As well, online classes allow nontraditional students to avoid microaggressions related to their gender, age, race, sexuality, religion, and status as a parent, and they report they are more willing to participate in discussions as a result (Fox, Citation2017).

We were already rethinking our hybrid model when the COVID-19 pandemic accelerated a shift in our approach. The pandemic helped refashion a prevailing mental model among Illinois faculty and program administrators that privileged traditional classroom instruction over online course delivery, especially in the acquisition of clinical skills. The rapid pivot to distance learning buoyed confidence among administrators and faculty that Illinois could administer a quality, mostly online, iBSW program. The entire social work faculty now had experience teaching online and many planned to continue to experiment with this teaching mode. These factors led us to adjust our hybrid model. Whereas we had originally planned to host classes one day per week in a classroom, we shifted to optional on-site events that celebrate the start and close of each semester. These events are intended to enable community and institutional belonging without requiring long commutes to attend classes. However, we maintained the plan for in-person field placements at agency settings near the student’s home community.

Proactive advising: A solution to protracted affiliation agreement processes

Although Illinois holds transfer partnership agreements with more than 30 community colleges throughout the state and participates in a statewide transfer agreement (Illinois Articulation Initiative, Citation2022), the School of Social Work has no unit-level agreements in place, and we recognized that such arrangements involve a lengthy process. In the absence of unit-level articulation agreements, we introduced the idea of proactive advising in which Illinois undergraduate advisors would meet with prospective transfer students before they applied to ensure they meet transfer requirements, to discuss social work career opportunities, and to advise to them on transferrable community college coursework.

Proactive advising represents a significant shift in perspective for Illinois staff; usually, our advisors only serve matriculated students. Here, an emphasis was placed on creating a warm handoff in the transition from community college to the iBSW program, facilitated by ongoing collaborative relationships with community college faculty and staff. We encouraged our community college partners to refer interested students, to whom we would reach out. Our undergraduate advisors also conducted brief presentations in classes and met with interested students. A series of informational webinars provided interested students more information and encouraged them to take advantage of proactive advising.

Although proactive advising serves as a useful intermediate measure, it only partially addresses a larger problem: the loss of credit hours among transfers that occurs in the absence of transfer partnerships (Jenkins & Fink, Citation2015). Students transferring to the iBSW program could incur additional expenses fulfilling extra course requirements and delaying degree completion (Worsham et al., Citation2021). Nearly all the faculty and administrators we engaged referenced this problem and the need to assure students that the classes they completed at the community college would count toward the iBSW degree. Proactive advising was adopted as an transitional solution to meet student need and build institutional trust, a strategy facilitated by the use of Transferology, a free online resource designed to explore transfer options through a nationwide network that tracks courses accepted for credit at other institutions (CollegeSource, Citation2022).

As of this writing, we have pending unit-level affiliation agreements with six community colleges in the Chicagoland area and three in central and southern Illinois. To develop these agreements, we leveraged mentorship from faculty and program administrators at the College of Engineering on campus who have successfully established unit-level agreements and created a pathway program that delivers a shared continuum of resources to facilitate institutional belonging, such as allowing students to take courses on campus prior to their transfer. Modeling after this approach, our articulation agreements will stipulate conditions for the guaranteed acceptance into the iBSW program, including a prescribed plan of study for transfer, a minimum overall Grade Point Average, and an application essay that describes the student’s interest in social work. It will also include institutional structures such as the designation of a point person at both the community college and the School of Social Work who will oversee activities that facilitate the transfer process and foster institutional belonging, such as attendance at the iBSW Virtual Information Sessions. Such unit-level agreements will further strengthen and streamline proactive advising protocols already in place and mutually reinforce one another.

Student evaluation: Early and often feedback loops

As a student population, community college students tend to operate with limited attentional bandwidths; a wrong course or missed deadline can easily translate into transfer delay (Jabbar et al., Citation2021). Therefore, institutions must have well-coordinated tracking systems to ensure that transfer contemplators become matriculated students. Even afterward, these tracking systems will be important to prevent matriculated students from exiting the program without confirming their degree.

We plan to use an online preapplication system to track community college students who intend to transfer into iBSW early in their academic career. This system will collect relevant pre- and postadmission data to evaluate different aspects of the iBSW transfer process. It will enable us to collect student demographics (age, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, first generation); ascertain whether the student completed general education and language requirements; and track the academic trajectories of four distinct student groups— transfer contemplators, transfer applicants, admitted students, and matriculated students. In addition, the system will enable us to track iBSW degree completion outcomes and postbaccalaureate pathways, and to compare those outcomes and pathways to campus BSW students. Such information will provide a useful feedback loop to identify areas in need of focused attention.

To access the preapplication system, community college students will complete a short online application that will enable them and their advisers to update course information and access resources to inform future planning. Because this online system interfaces with the sending and receiving institutions, the information exchanged will facilitate a smooth transition to iBSW by fostering transparency, enhancing institutional accountability, and nurturing interaction between the community college and Illinois. For example, we know that Illinois’s 3-year language requirement can pose a significant barrier for some students because most community colleges do not offer the third year; the online preapplication system will help identify such students and proactive advising will enable us to seek ways to help students fulfill the requirement. The preapplication serves as an informational feedback loop so potential community college students do not “fall through the cracks.”

In addition to monitoring prospective transfer students’ academic progress, it is important to track posttransfer metrics of engagement and retention. To assess institutional belonging and satisfaction with the program, we are developing online survey tools to collect data from students and instructors periodically throughout the school year. To access student challenges and potential problems with retention, we rely on the data system created by the director of Student Affairs, which has been notably successful in addressing student problems across the BSW and MSW programs. This system allows faculty to submit concerns about a student regarding course engagement or undesirable classroom behaviors that, if left unchecked, might negatively affect performance later in the field internship; these submissions alert the Student Affairs Office of potential problems that might hinder degree completion and signal the need for follow-up (see ). Because these concerns, and the tactics used to address them, are documented within a coordinated system, it allows for the early detection and resolution of problems.

The fast AP

To create a seamless transition from the iBSW program to our advanced-standing MSW programs, we developed an expedited application process (dubbed the Fast AP), which applies to all Illinois BSW students in good academic standing. By completing the simplified application, BSW and iBSW students simply notify the program of their interest to continue as advanced-standing students into one of our MSW programs on successful completion of their baccalaureate degree.

Here again, we used a systems-thinking approach to address structural impediments and mental models that might discourage the pursuit of the MSW by community college students. Historically, we have used a standard application process to determine whether an applicant is well-suited for our program. Because our MSW programs predated the BSW programs, the application process for our BSW graduates reflects the rote execution of protocol rather than an administrative necessity. Our BSW students rarely provide new or different information on their application beyond what faculty have already assessed. For our transfer students, the MSW application prompts an evaluative process shortly after their admission to Illinois, an administrative hurdle that could delay the procurement of a graduate degree.

Faculty and administrators expressed concern that dropping the evaluation might involve admitting problematic students or lowering our standards. From the perspective of bounded rationality, one could easily understand how negative experiences with a few students might influence our colleagues’ receptiveness to the Fast AP. Administrative concerns about our BSW students’ readiness for master’s-level work were discussed in faculty meetings and addressed with admission data as well as by clarifying existing protocols for accessing student support services through the student concern form. This attentive, nonjudgmental, data-driven response led to faculty buy-in and a unanimous vote to institute the Fast AP for all our BSW students, clearing the pathway for iBSW students to proceed to an advanced-standing MSW program.

Conclusion

While issues of diversity, equity, and inclusion have long been on social work’s agenda for social justice, we rarely consider how the structure of social work education across degrees and by institutions might contribute to inequitable outcomes. In creating Illinois’s iBSW program, a systems-thinking approach enabled us to take a broader perspective that extends beyond the needs of any singular program. A systems-thinking approach enabled to us to shift our goal as a degree-granting program to one of crafting a coordinated, interinstitutional system that aims to grow nontraditional students into social work professionals who thrive in the field and, through their inclusion, bring much-needed diversification and talent to the field.

As we devised new structures that facilitate access to a social work degree for community college students, we streamlined the pathway to an advanced degree for all our BSW students. This approach also has implications for community college students throughout the state. Our hybrid program paves the way for students attending community colleges in central and southern Illinois to transfer into our iBSW program, complete their online coursework, and complete a field placement in their home community, expanding its reach beyond the Chicagoland region into rural communities, which have a growing need for social workers. We hope it may serve as a model for other programs nationwide to develop educational structures that promote more desirable outcomes for the profession’s future workforce.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Lissette M. Piedra

Lissette M. Piedra is Associate Professor at University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. She is also co-Editor-in-Chief of Qualitative Social Work. Christine Escobar-Sawicki is Clinical Associate Professor at University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Carol Wilson Smith is Clinical Associate Professor and BSW Program Director at University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Christine Escobar-Sawicki

Lissette M. Piedra is Associate Professor at University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. She is also co-Editor-in-Chief of Qualitative Social Work. Christine Escobar-Sawicki is Clinical Associate Professor at University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Carol Wilson Smith is Clinical Associate Professor and BSW Program Director at University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Carol Wilson Smith

Lissette M. Piedra is Associate Professor at University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. She is also co-Editor-in-Chief of Qualitative Social Work. Christine Escobar-Sawicki is Clinical Associate Professor at University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Carol Wilson Smith is Clinical Associate Professor and BSW Program Director at University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Notes

1 The iBSW is a Bachelor of Social Work program in which courses are completed online, over an internet connection. The campus BSW program mainly delivers its courses through the traditional face-to-face format. We use the same distinction for our Master of Social Work (MSW) and iMSW programs.

References

- Belfield, C., Fink, J., & Jenkins, P. D. (2017). Is it really cheaper to start at a community college? The consequences of inefficient transfer for community college students seeking bachelor’s degrees. Community College Research Center, Columbia University. file:///C:/Users/lmpiedra/AppData/Local/Temp/really-cheaper-start-at-community-college-consequences-inefficient-transfer.pdf

- Belliveau, M., Schank, K., & Roth, S. (2019). Balancing clarity, rigor, and access: Academic transfer in social work education. Journal of Baccalaureate Social Work, 24(1), 49–59. https://doi.org/10.18084/1084-7219.24.1.49

- Berg-Weger, M., Birkenmaier, J., Tebb, S. S., & Rosenthal, H. (1999). Bridging new heights: Creating linkages between community colleges and baccalaureate programs. Journal of Baccalaureate Social Work, 4(2), 109–119. https://doi.org/10.18084/1084-7219.4.2.109

- Blaylock, R. S., & Bresciani, M. J. (2011). Exploring the success of transfer programs for community college students. Research & Practice in Assessment, 6, 43–61. Retrieved November 8, 2021, from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1062742.pdf

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2021). Occupational outlook handbook, social workers. U.S. Department of Labor. Retrieved July 9, 2021, from https://www.bls.gov/ooh/community-and-social-service/social-workers.htm

- Chen, X., Elliott, B. G., Kinney, S. K., Cooney, D., Pretlow, J., Bryan, M., Wu, J., Ramirez, N. A., & Campbell, T. (2019). Persistence, retention, and attainment of 2011-12 first-time beginning postsecondary students as of spring 2017 (First Look) (NCES 2019-401). National Center for Education Statistics. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED593528.pdf

- City Colleges of Chicago. (2021). Interactive statistic digest. Retrieved July, 12, 2021, from https://app.powerbi.com/view?r=eyJrIjoiYWZiNjM4YTQtNjdmNS00NDdhLWI1YTEtZGY1YzEzOWI4ZTQxIiwidCI6IjUzNWU4MGQ1LTk5YTktNGZjOC1hODJhLWJhZWIyOTRkYTIzNiIsImMiOjN9

- CollegeSource. (2022). Transferology. https://www.transferology.com

- Community College Research Center. (2021). An introduction to community colleges and their students. Teachers College, Columbia University. https://ccrc.tc.columbia.edu/media/k2/attachments/introduction-community-colleges-students.pdf

- Council on Social Work Education. (2010). Student questions. https://www.cswe.org/about-cswe/faqs/student-questions/

- Council on Social Work Education. (2021). Directory of Accredited Programs. Retrieved July 9, 2021, from https://www.cswe.org/Accreditation/Directory-of-Accredited-Programs.aspx

- Cubit. (2022). Illinois counties by population. https://www.illinois-demographics.com/counties_by_population

- Czeisler, M. E., Lane, R. I., Petrosky, E., Wiley, J. F., Christensen, A., Njai, R., Weaver, M. D., Robbins, R., Facer-Childs, E. R., Barger, L. K., Czeisler, C. A., Howard, M. E., & Rajaratnam, S. M. W. (2020). Mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic—United States, June 24–30, 2020. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 69(32), 1049–1057. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.22.20076141v1

- De Montigny, J. G., Desjardins, S., & Bouchard, L. (2019). The fundamentals of cross-sector collaboration for social change to promote population health. Global Health Promotion, 26(2), 41–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/1757975917714036

- Fox, H. L. (2017). What motivates community college students to enroll online and why it matters. Office of Community College Research and Leadership. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED574532.pdf

- Fry, R., & Cilluffo, A. (2019). A rising share of undergraduates are from poor families, especially at less selective colleges. Pew Research Center. Retrieved April 12, 2021, from https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2019/05/22/a-rising-share-of-undergraduates-are-from-poor-families-especially-at-less-selective-colleges/

- Gallagher, R., Appenzeller, T., & Normile, D. (1999). Beyond reductionism. Science, 284(5411), 79. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.284.5411.79

- Glynn, J. (2019). Persistence: The success of students who transfer from community colleges to selective four-year institutions. Jack Kent Cooke Foundation. Retrieved July 9, 2021, from https://vtechworks.lib.vt.edu/bitstream/handle/10919/90744/PersistanceTransferFourYears.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Hassan, I., Obaid, F., Ahmed, R., Abdelrahman, L., Adam, S., Adam, O., Yousif, M. A., Mohammed, K., & Kashif, T. (2020). A systems thinking approach for responding to the COVID-19 pandemic. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal, 26(8), 872–876. https://doi.org/10.26719/emhj.20.090

- Illinois Articulation Initiative (2022). iTransfer: Illinois transfer portal. https://itransfer.org/

- Jabbar, H., Epstein, E., Sánchez, J., & Hartman, C. (2021). Thinking through transfer: Examining how community college students make transfer decisions. Community College Review, 49(1), 3–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091552120964876

- Jaschik, S. (2021). Biden proposes free community college, pell expanion. Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved June 21, 2021, from https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2021/04/28/biden-proposes-free-community-college-18-trillion-plan

- Jenkins, P. D., & Fink, J. (2015). What we know about transfer. Community College Research Center, Columbia University. https://doi.org/10.7916/D8ZG6R55

- Kingdon, J. W. (1995). Agendas, alternative, and public policies (2nd ed.). Addison Wesley Longman.

- Lamphere, L. (Ed.). (1992). Structuring diversity: Ethnographic perspectives on the new immigration. University of Chicago Press.

- Leischow, S. J., Best, A., Trochim, W. M., Clark, P. I., Gallagher, R. S., Marcus, S. E., & Matthews, E. (2008). Systems thinking to improve the public’s health. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 35(2 Suppl.), S196–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2008.05.014

- Luke, D. A., & Stamatakis, K. A. (2012). Systems science methods in public health: Dynamics, networks, and agents. Annual Review of Public Health, 33(1), 357–376. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031210-101222

- Maag, J. W. (2012). School-wide discipline and the intransigency of exclusion. Children and Youth Services Review, 34(10), 2094–2100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2012.07.005

- Mabry, P. L., & Kaplan, R. M. (2013). Systems science: A good investment for the public’s health. Health Education and Behavior, 40(1 Suppl.), 9S–12S. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198113503469

- Meadows, D. H., & Wright, D. (2008). Thinking in systems: A primer. Chelsea Green.

- Messinger, L. (2014). 2 + 2 = BSW: An innovative approach to the community college-university continuum in social work education. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 38(5), 454–465. https://doi.org/10.1080/10668926.2011.567145

- Mullainathan, S., & Shafir, E. (2013). Scarcity: Why having too little means so much. Macmillan.

- Nagaoka, J., Mahaffie, S., Usher, A., & Seeskin, A. (2020). The educational attainment of Chicago public schools students: 2019. UChicago Consortium on School Research. Retrieved July 9, 2021, from https://consortium.uchicago.edu/sites/default/files/2021-02/The%20Educational%20Attainment%202019-Dec%202020-Consortium.pdf

- National Association of Social Workers. (2021a). NASW code of ethics. Retrieved December 1, 2021, from https://www.socialworkers.org/About/Ethics/Code-of-Ethics/Code-of-Ethics-English

- National Association of Social Workers. (2021b). Undoing Racism through Social Work: NASW Report to the Profession on Racial Justice Action and Priorities. Retrieved July 10, 2021, from https://www.socialworkers.org/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=29AYH9qAdXc%3D&portalid=0

- Neuman, K. (2006). Using distance education to connect diverse communities, colleges, and students. Journal of Baccalaureate Social Work, 11(2), 16–27. https://doi.org/10.18084/1084-7219.11.2.16

- Office of Management and Budget. (2020). OMB Bulletin No. 20-01: Revised delineations of metropolitan statistical areas, micropolitan statistical areas, and combined statistical areas, and guidance on uses of the delineations of these areas. https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Bulletin-20-01.pdf

- Rempel, R. J. (2020a). The forgotten history of CSWE’s shift away from community colleges. Social Work Education, 39(4), 481–495. Retrieved May 18, 2020, from https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2019.1662896

- Rempel, R. J. (2020b). Truth in labeling? An initial evaluation of associate in social work programs. Journal of Baccalaureate Social Work, 25(1), 65–87. https://doi.org/10.18084/1084-7219.25.1.65

- Saleebey, D., & Scanlon, E. (2005). Is a critical pedagogy for the profession of social work possible? Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 25(3–4), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1300/J067v25n03_01

- Salsberg, E., Quigley, L., Richwine, C., Sliwa, S., Acquaviva, K., & Wyche, K. (2019). Education to social work practice: Results of the survey of 2018 social work graduates. Council on Social Work Education. Retrieved July 9, 2021, from https://www.cswe.org/CSWE/media/Workforce-Study/2018-Social-Work-Workforce-Report-Final.pdf

- Salsberg, E., Quigley, L., Richwine, C., Sliwa, S., Acquaviva, K., & Wyche, K. (2020). The social work profession: Findings from three years of surveys of new social workers. Council on Social Work Education. Retrieved July 9, 2021, from https://cswe.org/CSWE/media/Workforce-Study/The-Social-Work-Profession-Findings-from-Three-Years-of-Surveys-of-New-Social-Workers-Dec-2020.pdf

- Seaman, J. E., Allen, I. E., & Seaman, J. (2018). Grade increase: Tracking distance education in the United States. Babson Survey Research Group. Retrieved July 10, 2021, from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED580852.pdf

- Shank, B. W., & Thornton, S. B. (2006). Marketing the BSW program: A blend of creativity, ideas and resources. Social Work Faculty Publications (Vol. 15, pp. 1–9). UST Research Online. http://ir.stthomas.edu/ssw_pub/15?utm_source=ir.stthomas.edu%2Fssw_pub%2F15&utm_medium=PDF&utm_campaign=PDFCoverPages

- Simon, H. A. (2000). Bounded rationality in social science: Today and tomorrow. Mind & Society, 1(1), 25–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02512227

- Simon, H. A. (1972). Theories of bounded rationality. In C. B. McGuire & R. Radner (Eds.), Decision and organization (Vol. 1, pp. 161–176). North-Holland Publishing.

- Social Work Degrees. (2022). Advanced Standing MSW Programs. Wiley. https://www.socialworkdegrees.org/program/advanced-standing-msw

- Sowl, S., & Brown, M. (2021). “We don’t need a four-year college person to come here and tell us what to do”: Community college curriculum making after articulation reform. New Directions for Community Colleges, 2021(195), 143–156. https://doi.org/10.1002/cc.20473

- Staller, K. M. (2010). Social problem construction and its impact on program and policy responses. In S. B. Kamerman, S. Phipps, & A. Ben-Arieh (Eds.), From child welfare to child well-being: An international perspective on knowledge in the service of policy making (Vol. 1, pp. 155–173). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-481-3377-2_10

- University of Illinois. (2020). Fall 2020 new beginning freshmen 10-day profile. Retrieved July 7, 2021, from https://www.dmi.illinois.edu/stuenr/abstracts/FA20freshman_ten.htm

- University of Illinois. (2021a). History & mission. Retrieved June 15, 2021, from https://www.admissions.illinois.edu/Discover/history

- University of Illinois. (2021b). History of the universities: The University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. Retrieved July 1, 2021, from https://www.uillinois.edu/president/history/history_of_the_university/

- University of Illinois. (2021c). Illinois commitment. Retrieved July 9, 2021, from https://osfa.illinois.edu/illinois-commitment/

- University of Illinois. (2021d). Illinois extension. Retrieved July 1, 2021, from https://extension.illinois.edu/global/who-we-are

- University of Illinois. (2021e). Investment for growth program. Retrieved July 12, 2021, from https://provost.illinois.edu/about/initiatives/investment-for-growth-program/

- University of Illinois. (2021f). iPromise. Retrieved July 9, 2021, from https://ipromise.illinois.edu/whats-i-promise

- Wheeler, E. L. J. (2019, April 3). Extending “Guided Pathways” beyond the community college: Lessons for university transfer orientation. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 43(4), 275–279. https://doi.org/10.1080/10668926.2018.1460283

- Wood, J. L., Harris, F., III, & Delgado, N. (2016). Struggling to survive–striving to succeed food and housing insecurities in the community college. Community College Equity Assessment Lab (CCEAL). https://cdn.kpbs.org/news/documents/2016/12/05/STRUGGLING_TO_SURVIVE_-_STRIVING_TO_SUCCEED.pdf

- Worsham, R., DeSantis, A. L., Whatley, M., Johnson, K. R., & Jaeger, A. J. (2021). Early effects of North Carolina’s comprehensive articulation agreement on credit accumulation among community college transfer students. Research in Higher Education, 62(7), 942–975. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-021-09626-y

- Xu, D., Jaggars, S. S., Fletcher, J., & Fink, J. E. (2018). Are community college transfer students “a good bet” for 4-year admissions? Comparing academic and labor-market outcomes between transfer and native 4-year college students. The Journal of Higher Education, 89(4), 478–502. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2018.1434280

- Zack, L. (2020). Non-traditional students at public regional universities: A case study. Teacher-Scholar: The Journal of the State Comprehensive University, 9(1), 1–24. https://scholars.fhsu.edu/ts/vol9/iss1/1