?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Using a rich panel dataset of small and medium scale manufacturing enterprises (SMEs) active in the manufacturing sector in Viet Nam, this paper investigates the drivers of firm productivity, focusing on the role played by international management standards certification. We test the hypothesis that, accounting for technological innovation (product and process) and other variables related to technological capabilities, international standards are conducive to higher productivity, through improved management practices and business organization. In line with the requirement of continuous improvement implied by most international standards, the main findings show that the possession of an internationally recognized standard certificate leads to significant productivity premium. We further find that the effect of certification on productivity is particularly strong for firms with technological innovation, located in southern provinces, and operating in more scale-intensive industries.

1. Introduction

The economic performance of Viet Nam in the last decade has been impressive (McCaig and Pavcnik Citation2013). Between 2000 and 2015, gross domestic product (GDP) has grown at 7% per year, despite a slowdown due to the 2008 crisis. Foreign companies and foreign direct investment (FDI) have played a leading role in the production and export of relatively higher value-added productions in manufacturing sectors (Nguyen Citation2014). By contrast, the performance of domestic small and medium-sized firms shows a more mixed picture. In the manufacturing sector labour productivity of domestic small and medium scale manufacturing enterprises (SMEs) has been stagnating since 2011. Nevertheless, large differences among sectors and across different types of firms are observed (CIEM, DoE, ILSSA, and UNU-WIDER Citation2016). To develop policies oriented towards broad-based, inclusive, and sustained growth, it is, therefore, necessary to study the performance of national Vietnamese firms and its determinants. An accurate micro-data analysis of firm productivity is crucial for establishing the basis upon which growth may continue.

This paper builds on a rich literature on the drivers of productivity at the micro level. With the diffusion of micro-data, and acknowledged by endogenous growth models (Romer Citation1986; Lucas Citation1988; Scott Citation1989) technology and innovation activities and outputs became primary variables of interest in accounting for firm productivity. However, the observed relationship between technological innovation and firm productivity in developing countries has not always been in line with findings from advanced economies, presenting a lower than expected effect of technological innovation on firm-level productivity (Miguel Benavente Citation2006; Goedhuys, Janz, and Mohnen Citation2008; Aboal and Garda Citation2016 for services). Alternative innovation strategies related to the improvement of organizational practices and managerial styles have been gaining attention in empirical studies, reflecting an increased interest for a broader set of innovation capabilities beyond R&D activities (O’Brien Citation2016). In this respect, Bloom and Van Reenen (Citation2007, Citation2010) showed that a majority of firms in developing and emerging countries indeed suffer from poor management, with associated low levels of productivity.

A major way for firms in developing and transition economies to upgrade their managerial and organizational practices to world standards is through implementation of international management standards, such as ISO 9001 and ISO 14001. These standards provide a model for setting up a management system that should enable adopting firms to reach particular targets, being either quality or environmental sustainability. In fact, certification improves internal management operations and business practices, as they may facilitate networking and coordination in value chains through reduced transaction costs (Zoo, de Vries, and Lee Citation2017).

In Viet Nam, the adoption of management standards and certification is following the trend that has been witnessed on a global scale. With the opening of the Vietnamese economy in 1986 and membership of ASEAN in 1997 and WTO in 2007, domestic manufacturing firms became increasingly exposed to new regulation and foreign buyer requirements about internal firm organization and process management characteristics. Certification of standards became an accepted way of addressing customer expectations about product and production process characteristics, such as quality, safety, environmental impact, or social accountability between suppliers and buyers and led to increased re-organization of companies to address these expectations. Among the internationally recognized standards, the most frequently applied are ISO 9001 and ISO 14001 (ISO Citation2016). The adoption of this type of standards is done on a voluntary basis, and adherence to their requirements is assessed by third parties, which conduct periodical audits even once the certificate has been obtained. The number of ISO 9001 certificates in Viet Nam has been increasing since 1995, when the first certificate was issued, to reach 7000 newly issued certificates in 2009. The first ISO 14001 certificate was issued in 1999. The number of these certificates only surpassed 1000 in 2015.

Despite this tendency of increasing numbers of firms investing in certificate adoption, the empirical investigation on the role of adopting standards on firm productivity remains scarce. The availability of information about the Viet Nam manufacturing sector has spurred studies on firms’ characteristics and productivity, but mainly from a specific perspective such as formality or clusters (Rand and Torm Citation2012; Howard et al. Citation2014) or in food industry (Trifković Citation2016). Hence, a wider investigation of the role played by international standards on firm-level productivity is still lacking.

This paper addresses this caveat and investigates the role of international management standard certifications as alternative innovation strategy, to raise the productivity performance among Vietnamese SMEs. Using three rounds of panel data, we test the hypothesis that standards certification is conducive to higher productivity, through improved organizational and business practices associated with standard adoption. In addition, we account for technological (product and process) innovation, and we investigate if the effect of certification is stronger among technological innovators than in other firms. We also address firm heterogeneity and the presence of uneven returns to certification by exploring the existence of industry and location effects.

The main findings show that the possession of an internationally recognized standards certificate leads to a significant productivity premium. Moreover, the effect of certification on productivity is particularly strong for firms with technological innovation, located in southern provinces, and operating in more scale-intensive industries. This finding is robust to different measures of labour productivity and model specifications.

Our paper contributes to the existing literature in various ways. First, it bridges a gap that exists between business studies on standards and corporate strategies on the one hand, and the literature on innovation and firm performance on the other hand. By investigating the context of Viet Nam, the paper also contributes to the debate on innovation, standards, and development. Second, considering that the adoption of international standard certifications may represent the introduction of significantly improved methods and routine among firms operating in a developing context (Zoo, de Vries, and Lee Citation2017), we employ certification as a measure of organizational innovation, in contrast to the majority of empirical studies using innovation survey data following a design proposed by the OECD (Citation2005). Given the issues related to measuring organizational innovation with survey data (Armbruster et al. Citation2008), our measure is more objective than a self-reported measure and more policy-relevant conclusions can be tied to findings based on the objective certification criteria. Third, we use panel data that are unique for the context of a developing and transition country and rich in the scope of information gathered to study productivity determinants, including standard certifications. Finally, we implement an identification strategy with the inclusion of an extensive set of control variables, including firm, sector, and time fixed effects along with time-varying firm- and sector-level controls. We correct for remaining sources of endogeneity with an instrumental variables approach. Overall, the implications of our results may be found useful for public policies targeted at increasing overall productivity level among SMEs in Viet Nam and other developing and transition economies.

The paper is structured as follows. Section 2 presents a review of the empirical literature on productivity determinants in developing countries. Section 3 describes the data, the model, and the estimation strategy. Section 4 presents the results. Section 5 discusses the findings in a broader context. Section 6 concludes, highlighting the policy implications of our findings and the possible avenues for future research.

2. Related literature

2.1. Innovation and productivity

Spurred by endogenous growth theories (Romer Citation1986; Lucas Citation1988), technological innovation outputs (such as product and process innovations) and innovation activities (such as R&D) have been lying at the core of the empirical literature investigating the drivers of productivity at the micro level. Most studies have examined unidirectional causal links running from innovation to economic performance (e.g. Crépon, Duguet, and Mairessec Citation1998; Parisi, Schiantarelli, and Sembenelli Citation2006). Many studies use variations of the so-called CDM (Crépon-Duguet-Mairesse) model by Crépon, Duguet, and Mairesse (Citation1998), using a recursive system of three blocks of equations, for R&D investments, innovation outputs and productivity, measuring the effect of R&D on innovation outputs and of innovation outputs on productivity using a sequential approach, where the predicted value of one endogenous variable enters the estimation of the next equation (Mohnen and Hall Citation2013; Lööf, Mairesse, and Mohnen Citation2017). More recently studies moved beyond a focus on one-way relationships typical in the innovation literature, and propose a ‘circular’ approach, emphasizing cumulative processes and lags, feedback loops and complex and simultaneous interactions between innovative inputs, outputs and economic performance (Bogliacino and Pianta Citation2013; Baum et al. Citation2017; Bogliacino et al. Citation2017; Peters, Roberts, and Vuong Citation2017; Yu et al. Citation2017). They find complex links at play in different phases of the innovation process and in the feedback between economic success and sustained innovation expenditure. These works account for the complexity with which technological change may turn into superior performance among heterogeneous actors.

Among others, Bogliacino and Pianta (Citation2016) address the issue of uneven returns to innovation across firms focusing on the role of structural differences between industries, accounting for the different dimensions of innovation as well as their outcome and economic impact. Others have revitalized the debate on firm heterogeneity, showing that innovation and other factors may have a different effect on the different quantiles of the conditional distribution of the firm performance indicator (Coad and Rao Citation2008; Goedhuys, Janz, and Mohnen Citation2008; Goedhuys and Sleuwaegen Citation2010).

While these different models and approaches have provided convincing evidence of a positive effect of technological innovation on firm productivity in the case of developed economies, the available evidence for a developing context presents mixed and more ambiguous results, as not all works find evidence of a clear positive impact (Chudnovsky, López, and Pupato Citation2006; Miguel Benavente Citation2006; Goedhuys, Janz, and Mohnen Citation2008; Aboal and Garda Citation2016).

These results have been partly explained by the different conditions in which innovation activities are undertaken in a developing context (OECD Citation2005). Firms in developing countries possess lower levels of human capital, and their technological capabilities are scarce and less diffused compared to advanced economies (Morrison, Pietrobelli, and Rabellotti Citation2008). Most of them are micro and small enterprises, not working on the technology frontier, and their process of learning is more related to activities such as imitation, adaptation, and mastery of technologies developed somewhere else. The innovation outcomes are not likely to be generated through R&D departments, and tend to be less radical and more incremental in nature (Bogliacino et al. Citation2012; O’Brien Citation2016; Zanello et al. Citation2016). In response to the weaker role played by ‘traditional’ technology-related and technological innovation-related variables, a broader set of explanatory factors should be included in productivity analyses for SMEs, including non-technological innovations and organizational change (OECD Citation2005), which encompass both organizational learning and improvements in operational and management practices (Bloom and Van Reenen Citation2010; Gunday et al. Citation2011; Camisón and Villar-López Citation2014).

Past decades witnessed the expansion of managerial literature on the positive impact of business and management practices on firm performance levels in advanced economies (Nair Citation2006), as well as in the context of developing and emerging countries (Bloom and Van Reenen Citation2007, Citation2010). As shown by some of these studies, SMEs in developing and transition economies tend to operate far from the ‘international frontier’ of managerial systems and practices, which may be persistent and hindering firm performance. Bloom et al. (Citation2013) argue that better managerial practices may significantly increase productivity and efficiency in Indian textile firms, as well as foster the application of other potentially productivity-enhancing factors, such as computer usage. Moreover, managerial systems differ largely across countries, firms and sectors, but in a developing country, these differences are exacerbated by the existence of informational barriers that limit the spread of organizational best practices (Bloom et al. Citation2013).

2.2. International management standards as a measure of organizational innovation

A possible way to source knowledge on management practices is through the adherence to international standards. International standards represent a form of codified knowledge that can bring management systems to a more sophisticated level than the practices generally diffused in a developing context, since they tend to entail ‘novelty and excellence’ of the knowledge from advanced economies (Zoo, de Vries, and Lee Citation2017, 341). Management standards are found to be an important source of management knowledge for SMEs in developing countries (Goedhuys and Sleuwaegen Citation2013, Citation2016), and in Africa (Goedhuys and Mohnen Citation2017) in particular. They have started to be used in firm-level productivity analyses as a proxy for the adoption of advanced management practices in developing countries (Sadikoglu and Zehir Citation2010).Footnote1 For these reasons, international standards certifications have been also used as guidelines for national regulations for safety and quality (Zoo, de Vries, and Lee Citation2017).

International management standards – such as the ISO 9001 or the ISO 14001 issued by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO)Footnote2 – represent a systematization of ‘how things should be done’ within and between firms, in line with global management experience and internationally acknowledged good practices. These international standards are based on a series of principles – including, among others, customer focus, leadership, continuous improvement, human resources engagement, coordination, evidence-based decision making, monitoring, and evaluation. In practice, they provide a model to follow when setting up and operating a management system in line with specific principles and targets, which can vary from product quality (ISO 9001), environmental performance (ISO 14001), and food safety (ISO 22000) to occupational health and safety management (ISO 18000) or social responsibility (ISO 26000). Furthermore, once a certification has been obtained, firms have to go through regular assessments and audits to be able to maintain it, which often requires that processes fostering monitoring, continuous learning, and improvement – the fundamental principles of management standards – are put in place.

The adoption of international standards involves the reshaping of internal procedures, re-organizing and eventually routinizing some processes in order to make them more efficient; moreover, maintaining a standard certificate involves continuous incremental innovation in business practice and organization. Considering the Oslo Manual definition of organizational innovation as ‘new business practices, workplace organization or external relations’ (OECD Citation2005, 51), an international standard certification can, therefore, be considered as a form of organizational change that implies the introduction and modification of firm routines.

2.3. Certification and firm performance

Since the early 2000s, scholars have investigated both the determinants of adoption as well as the effects of international management standards certification on firm performance. In particular, the impact of certification has been classified as ‘external’ or ‘internal’ (Sampaio, Saraiva, and Guimarães Rodrigues Citation2009; Heras-Saizarbitoria and Boiral Citation2013). External benefits result from a reduction of transaction costs, as certificates signal that the firm is a reliable partner, with a better reputation, raising credentials in the marketplace (King, Lenox, and Terlaak Citation2005; Terlaak and King Citation2006; Potoski and Prakash Citation2009; Goedhuys and Sleuwaegen Citation2013; Citation2016; Djupdal and Westhead Citation2015). Internal benefits are instead related to improvements in fundamental operations within the firm, with systematically better-managed production procedures and increased monitoring, also possibly leading to increased efficiency in the use of resources, and reduction of waste and pollution, as evidenced in a number of management studies (González, Sarkis, and Adenso-Díaz Citation2008; Gray, Anand, and Roth Citation2015; Lannelongue, Gonzalez-Benito, and Gonzalez-Benito Citation2015).

The internal benefits can also be generated through an effect on human resources. Studies show that maintaining a standard requires investments in training of employees to develop skills and capabilities, increasing the level of human capital (Blunch and Castro Citation2005). Firms adhering to standards are more likely to provide better work conditions for their labour force, experiencing positive effects on the employees (Levine and Toffel Citation2010; Trifković Citation2017). Thus, introducing better practices for human resources as part of overall management quality improvements, providing training to increase human capital, and improving workplace safety and satisfaction may contribute to better working conditions and better employee performance, consequently increasing labour productivity (Sadikoglu and Zehir Citation2010; Delmas and Pekovic Citation2013).

Building on these findings, we analyse the impact of international standard certification as a non-technological innovation strategy on firm productivity. We test the hypothesis that, besides technological (product and process) innovation, standards certification raises the productivity of SMEs in Viet Nam by enforcing organizational innovation through continuous incremental improvements in management systems and organizational routines. We also provide evidence on the interplay with technological innovation by estimating whether the effect of certification is stronger for product and process innovating firms than for firms that have no technological innovation. By doing so, we contribute to a literature that shows that more complex innovation strategies, combining technological and non-technological innovation, may be more effective for productivity than firms that engage in only one type of innovation (Polder et al. Citation2010; Mothe, Nguyen-Thi, and Nguyen-Van Citation2015; Tavassoli and Karlsson Citation2016; Cozzarin, Kim, and Koo Citation2017).

3. Empirical approach

3.1. Data

The data used in the present study come from the 2011, 2013, and 2015 rounds of the SME survey conducted in 10 provinces in Viet Nam every second year since 2005 to assess the characteristics of the Vietnamese business environment. We use the three final rounds because the question about the application of management standards was added in the 2011 survey round. The random sample was stratified by ownership type to include: household establishments, private enterprises, collectives or cooperatives, and limited liability and joint stock companies. It includes only firms active in manufacturing sectors and with less than 300 employees. Apart from the enterprises interviewed in 2005 that still operate, the survey contains enterprises added to replace those that in the meantime have stopped operating or have changed owners, sector, or location. in the Appendix provides more information about the survey.

For the analysis in this paper, we use, on the one hand, an unbalanced sample of 3065 micro, small, and medium enterprises that have participated in at least one of the survey waves between 2011 and 2015; on the other hand, the balanced sample, including firms that participated in all considered survey waves, totalling 1098 firms. Firms that operate in agriculture and with the participation of foreign or state capital are not a part of the dataset, giving a homogenous sample of domestically owned private SMEs.

The questionnaire includes information on enterprise characteristics and practices, such as number and structure of workforce, technology and innovation, international standard certification, revenues and costs, inputs, customers, owner characteristics, and economic constraints.

3.2. Empirical model and estimation strategy

Consistent with our main interest in the effect of standards on productivity, we base the estimation on a Cobb–Douglas production function which includes, alongside the conventional production factors of capital and labour, innovation-related factors and international standard certifications. The production function is written as:(1)

(1) where Yit denotes total output of firm i in year t (measured as sales), Kit denotes capital input, Lit represents labour, α and β denote the elasticities of output with respect to physical capital and labour, respectively. Ait, captures total factor productivity (TFP) and is modelled as a function of technological activity (Tit), here represented by technological innovation (INNit) and international standard certification (Sit), together with time-varying firm-specific characteristics (Xit), location- and sector-specific control variables (Cit) affecting productivity.

Dividing both sides by Lit, Equation (1) becomes:(2)

(2) Then, taking the natural logarithms of all factors, and replacing Tit by its proxy variables standard certification, innovation and firm controls, we obtain the following estimation equation:

(3)

(3) where yit denotes labour productivity of firm i in year t, measured as sales per employee, kit denotes capital–labour ratio, Lit represents labour,

and

), measuring deviations from constant returns to scale. We also include time fixed effects,

, to capture the influence of aggregate trends. The idiosyncratic error term (

it) is assumed to be normally distributed (

).

We focus on the relationship between international standard certification and productivity, which is identified from the impact of certification on the within-firm variation in productivity over time, controlling for all time-invariant heterogeneity in firms. Identifying the causal impact of standard certification on productivity is challenging as the adoption is not randomly distributed across firms. We have to take into account that endogeneity may be present, and from multiple sources. First, the estimation could suffer from simultaneity bias when the most efficient and productive firms are more likely to have the resources to obtain certifications more easily. Second, endogeneity issues may also arise when both the dependent and some independent variables are driven by the same unobservable factors, which may or may not change over time. Controlling for time and firm-specific effects addresses one part of this problem, but there could also be time-varying characteristics, such as a change in management or preferences for certification that could bias the estimation.

We start by estimating Equation (3) with OLS and conduct a sensitivity analysis of the estimated coefficients of the variable standards to omitted variable bias using the methodology proposed by Oster (Citation2016) and applied by Bogliacino, Cirillo, and Guarascio (Citation2017). In addition, we explicitly consider the role of unobserved firm heterogeneity and decompose the error term it into a time-constant and time-varying component. We apply a fixed effects model that eliminates the time-constant unobserved heterogeneity.

To deal with the remaining problem of time-varying unobserved heterogeneity, we estimate the model using the system generalized method of moments (GMM) (Arellano and Bond Citation1991). This method combines first difference transformation to eliminate time-constant unobserved heterogeneity with an instrumental variable estimation to further reduce remaining endogeneity bias. We treat the location, sector and time dummies (Cit and ) as exogenous, certification Sit as endogeneous and all firm characteristics Xit as predetermined. As the panel contains three periods, endogenous and predetermined variables are instrumented with two lags in the difference equation and with their difference lagged once in the levels equation.

In addition, we implement a two-stage least squares (2SLS) estimation in which we instrument the binary variable for international standard certification with a set of instrumental variables. As instruments, we use a dummy variable equalling one if a firm has been required by costumers to obtain any internationally recognized certificationFootnote3 and a variable resulting from the interaction of the province-sector share of standards certification with the district-sector rate of internet use by firms and the magnitude of firm’s social network.Footnote4 These variables capture the exposure of firms to information about standards, allowing a ‘network effect’ in adopting a standard as firms look at their neighbours and are influenced by their decisions to apply for a standard certificate. The rationale for the choice of these instruments follows the relevant empirical literature (Hansen and Trifković Citation2014; Goedhuys and Mohnen Citation2017; Trifković Citation2017). The results of the Hansen J test supporting the validity of these instruments are reported in .

The inclusion of the technological innovation variable in the model is likely to raise similar endogeneity concerns as with the variable for certification of international standard. As finding a suitable instrument for innovation alongside standard is extremely challenging, we address this concern by splitting the sample by innovation status and instrumenting the variable for standard. In this way, we can separately measure the effect of standards for firms with and without technological innovation.Footnote5 A recent paper by Lu, Chen, and Kao (Citation2017) uses similar approach (i.e. splitting the firms into two samples according to board size and analysing the difference for the two samples) to study the relationship between board tenure and firm performance.

Finally, we explore the presence of heterogeneous effects of standard certification across industries and geographical locations. Since industries tend to share the same technological change, production systems and market structures, the use of industry classifications such as the Pavitt taxonomy (Pavitt Citation1984) may shed further light on the relationship between standards and productivity at firm-level. Following a recent revision of the Pavitt taxonomy (Bogliacino and Pianta Citation2016), we distinguish between scale and information-intensive (SII) and supplier-dominated (SD) industries (see for the classificationFootnote6), and we run the original model interacting standard certification with the industry classification variable. For geographical location, we generate two location dummies, for firms is located in an urban province (versus rural provinces), and for firms operating in the South of the country (versus the North). The comparison across Southern and Northern provinces is often used for Viet Nam, given the large historical, institutional, and economic differences that still persist between the two areas.

Table 1. Definition of variables.

3.3. Variables

In our equation, the dependent variable (yit) is measured as the (log of) sales per employee in a firm i in time t. The independent variables include capital per employee () and labour (

). We also control for quality of human capital (proxied by training and share of professional workers) and quality of physical capital (proxied by the share of machinery which is under three years old). presents the definitions for the used variables.

We introduce international standard certification (Sit) as our main variable of interest, which takes the value of 1 if the firm has an internationally recognized certification (and 0 otherwise). By adding this variable to our labour productivity equation, we test whether the implementation of international standard certification may provide certified firms with a ‘productivity bonus’. In line with the debate in the empirical literature, we include a variable for technological innovation (INNit), which takes the value of 1 if the firm has introduced a product or process innovation since the past survey (and 0 otherwise).Footnote7

We also add firm-related time-varying controls (Xit), including (the log of) firm age, the share of sales that corresponds to goods for final consumption, a dummy for legal ownership form (taking the value of 1 if the firm is a joint stock company), a binary variable for the level of capacity utilization (taking the value of 1 if the firm can increase the production from the present level using existing equipment/machinery by more than 50%), and for having received technical assistance from the government during the year before the survey. To account for the fact that competition may influence the effect of standards in some more sophisticated sectors, we also include a sector (2-digit)-level Herfindahl–Hirschman (HH) Index, which takes values between 0 (with perfect competition) and 1 (monopolistic market concentration). Finally, we add a set of location (provinces) and sector (at 2-digit level) binary variables as controls (Cit). Controlling for location-related factors with province dummies is relevant, since policies and regulations are implemented at this specific administrative level. We control for time trends by including year dummies.

3.4. Summary statistics

presents the basic summary statistics (mean and standard deviation) over different sample compositions (per year, total unbalanced and balanced). The figures for labour productivity, reported in the first two rows of , show how this has been stagnating over the considered period. The value of this variable (sales per employee) has been oscillating around the average value for the total unbalanced sample (which corresponds approximately to VND300 million),Footnote8 with a decline in 2013 and a recovery in 2015 but still not reaching 2011 levels.

Table 2. Summary statistics.

The proportion of firms with an internationally recognized certification is about 7% (in the whole unbalanced sample). Looking at each time period, there is a decline in the sample frequency of the last period (2015) down to 5.4%. International certifications tend to follow a sectorial pattern, which is persistent across different time periods: between one-quarter and one-third of these certifications concentrate in food and beverages.Footnote9

Technological innovation is much more common than having an international standard, with an average sample frequency of almost 30% over all periods. However, it is important to note a sharp decline in its value since 2011, with a reduction from 46% to less than 20%.

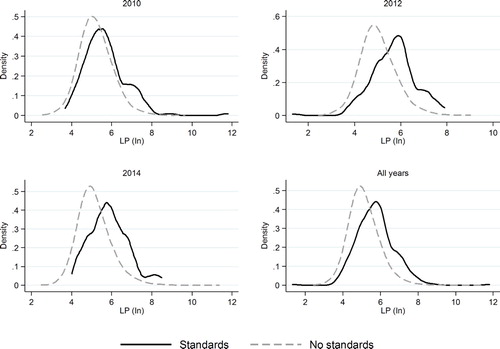

There is a clear concentration of activities in food and beverages (more than 25% of firms) and in the area of Ho Chi Min City (more than 27% of enterprises). As illustrated in : the productivity distribution of certified firms dominates the distribution of non-certified firms in all observed periods, and also presents a less skewed and more regular bell shape.

Figure 1. Kernel density estimation of labour productivity across firms by application of standards. Source: Authors’ elaboration based on the SME survey data (CIEM et al. Citation2016).

Note: Epanechnikov kernel and bandwidth 0.25.

4. Results

4.1. The drivers of labour productivity

The results of the productivity equation are reported in . The first four columns present the pooled OLS and fixed-effect estimations for unbalanced and balanced samples, respectively. Column (1) shows a significant positive impact of standards on productivity when only technological innovation, core observable firm characteristics, and time effects are controlled for. Additional control variables introduced in column (2) only slightly reduce the coefficient size, which remains the same in the OLS estimation on the balanced panel shown in column (3). Column (4) presents the results with firm fixed effects (FE), which account for time-invariant unobservable heterogeneity and confirm a significant positive effect of standards, but with a smaller coefficient than in the case of OLS. Columns (5) and (6) present the result of system GMM estimations on the unbalanced and balanced sample, respectively. In both models, the impact of standard on productivity is similar, in terms of sign, significance and magnitude, to OLS results in columns (2) and (3). The coefficient of technological innovation is still positive but smaller and significant only in the balanced sample.

Table 3. Drivers of labour productivity.

As main result, the variable for standard certification presents a positive and significant coefficient in both pooled 2SLS and fixed effects models: having a standard certificate increases the level of labour productivity between approximately 44% (in pooled 2SLS) and 30% (in 2SLS FE, significant at 10%), on average and all else equal. These results support our hypothesis, that firms with a management standard certification present higher levels of labour productivity than non-certified firms. We interpret this as the impact of better organizational and managerial practices related to standard implementation, controlling for the effect of technological innovation, training, and other more ‘conventional’ drivers of labour productivity (such as labour, capital–labour ratio, and firm age), among others.

In the IV estimations, the coefficients for standards are larger than in the pooled OLS and fixed effects estimations, suggesting the presence of a downward bias in the non-IV estimations. Moreover, the results of the 2SLS FE model (column (8)) are also not biased by unobserved heterogeneity driven by firm-varying but time-invariant factors. It is also important to note how the unbalanced and balanced panel pooled OLS estimations provide practically the same coefficient for standard, and do not differ much also for the other explanatory variables. This offers a further confirmation that the differences in the estimations between pooled and FE models are due to different estimators and not to the type of sample these require.

The relevance of the two instruments can be assessed from the first-stage equation in the 2SLS estimations and relevant test statistics. The results of the first-stage equation are reported in in the Appendix, and they are in line with what has been found by other empirical works investigating standard adoption (Goedhuys and Sleuwaegen Citation2013; Hudson and Orviska Citation2013; Gebreeyesus Citation2015; Goedhuys and Mohnen Citation2017), showing that having a management standard certificate is on average more likely with larger firm size, endowed with higher levels of human and physical capital. Both instruments significantly predict the adoption of standards. The null hypotheses that the model is under-identified (Kleibergen–Paap LM test) and that the instruments are weak are both rejected (with p = .000 in all tests). The values of Kleibergen–Paap Wald F test are larger than the rule-of-thumb value 10, while the values of Cragg–Donald Wald F statistic surpass the Stock–Yogo critical values for weak instruments. Finally, the test for over-identification (Hansen’s J) fails to reject the null hypothesis that the instruments are valid, as shown at the bottom of .

In the pooled 2SLS IV model (column (7)), the coefficient of technological innovation is also positive and significant, as are the coefficients of labour and capital–labour ratio. Following the model for the production function presented in Section 3, this result suggests the presence of increasing returns to scale of primary inputs (capital and labour), which is not surprising considering the small size of the firms in the sample. The coefficient of firm age is negative and significant. The share of professional workers is significant and positive, reaffirming the importance of qualitative factors in complementing the role of labour as fundamental driver of firm productivity. The effect of technical assistance is also significant (at 5%) and negative. The other control variables are not found to have a significant effect on firm productivity level, including the HH Index for market concentration – which is likely to be accounted for by other competition-related factors, such as the controls for sectors. Its sign is negative, which points towards a positive correlation between market competition and performance.

Controlling also for time-invariant unobserved heterogeneity with FE (column (8)), firms with a standard certificate, with technological innovation and a higher capital–labour ratio still enjoy a significantly higher labour productivity level. However, the effects of labour, firm age, and the share of professional workers are no longer significant. Also, the coefficients of the dummy variables JSC, capacity utilization, and training are not significant. This is not too unexpected: FE models are not very appropriate to assess the role of variables that change slowly over time with low within-variation, since they tend to level out the effect of these observed quasi-time-invariant factors. Hence, the positive and significant coefficient of the dummy variable for standards even in the 2SLS FE estimation is an indication of the robustness of our finding about the positive impact of standards certification on labour productivity levels.

We also conduct a sensitivity analysis to omitted variable bias in the productivity equation, as proposed by Oster (Citation2016) and show the coefficients after correcting for bias in . Our approach follows Bogliacino, Cirillo, and Guarascio (Citation2017) and consists of varying the values of the maximum R2 in regressions of interest, based on which we can establish the degree of confidence for our estimates. The corrected coefficients are consistent with the expected effects, that is, the positive coefficient supports the hypothesis that standards improve productivity and in fact fall in size between the FE and 2SLS estimates.

Table 4. Test for omitted variable bias.

4.2. Standards certification, innovation, and productivity

shows that certification and technological innovation often occur jointly. Out of all certified firms, 46% in the unbalanced and 53% in the balanced panel reported to have been engaged in innovative activities in the two years prior to the survey. The rate of innovation has slowed down among certified firms between 2011, when 63% of certified firms reported at least one type of technological innovation, and 2015, when the corresponding value dropped to 36%. Apart from the peak in 2013, the prevalence of certification among the firms that innovate has been around 11%. The prevalence of innovation among certified firms could indicate that the effect of standards on productivity could be different depending on the level of innovative activities. This argument is in line with the empirical studies on complementarity and interaction among alternative innovation strategies, such as between organizational and technological innovation (Polder et al. Citation2010; Cozzarin, Kim, and Koo Citation2017).

Table 5. Standard certification and technological innovation.

Especially in developing countries, standards are seen as a form of innovation, so it can be easier for firms that already have some experience with technological innovations to implement standards. We, therefore, measure the effect of standards separately for the sub-sample of firms that innovate and the sub-sample of firms that have not had technological innovation in the past two years.Footnote10 Results for the pooled OLS and 2SLS (applying the same instruments used in the IV estimations reported in ) are shown in .

Table 6. Drivers of labour productivity by innovation.

While the magnitude of the significant and positive coefficients for standard does not differ much across the different samples in the pooled OLS models (columns (1) and (3)), the comparison of the first row of the 2SLS models (columns (2) and (4)) reveals a very different story for innovative firms: with a technological innovation, certified firms can enjoy a ‘productivity bonus’ equivalent to a 69% higher productivity level, as compared to innovating but non-certified firms. The same ‘bonus’ is reduced to 25% for non-innovating firms (significant at 10%).

4.3. Sector and location heterogeneity

We complete our analysis investigating the presence of heterogeneous industry and location effects for standard certification. Results are reported in .

Table 7. Productivity, innovation, and standards with location and industry effects.

Columns (1) and (2) show the results obtained when interacting standard certification with the dummy for SII industries. The coefficient of the interaction term is positive and significant in the 2SLS (column (2)), suggesting the existence of a larger return to certification for firms operating in sectors classified as SII industries. Arguably, as firms in SII are characterized by a larger scale, the implementation of better-managed procedures leading to a more efficient use of resources and a better (re-)organization of the labour force and better coordination appears to have important productivity effects. On the contrary, for SD industries, populated by on average smaller firms with lower technological dynamism, the productivity gains from reorganization and managerial improvements could be relatively less important, although still positive.

Turning to geographical location, the coefficient of the interaction between certification and the urban dummy is positive, but not significant in the 2SLS model (column (4)), while the coefficient of the interaction term with the South dummy is positive and strongly significant in both OLS and 2SLS estimations (columns (5) and (6)). Thus, our results confirm the presence of a difference across the South and the North of the country in terms of what influences firm-level productivity, a difference that is more significant than along other geographical classifications. In fact, the South it is where the lively economic province of Ho Chi Min City is located, which alone hosts one-quarter of all sampled firms. Moreover, the Southern region has always been more engaged in international trade with advanced countries, while the North of the country has typically interacted with neighbouring countries, such as China. In the sample, around 20% of export of the firms from the North goes to China, while this proportion is 10% for the firms from the South. Southern firms ship 42% of exports to Japan, EU, and US, against 8% for Northern firms. The interaction with more demanding and sophisticated partners may push firms towards the full and adequate enforcement of certification-required management systems and organizational practices, ultimately resulting in a stronger positive effect on firm productivity.

Another way we explored the existence of uneven returns to standard certification is by looking at its effect at different deciles of the productivity distribution using quantile regression as in Goedhuys, Janz, and Mohnen (Citation2008), Coad and Rao (Citation2008), and Goedhuys and Sleuwaegen (Citation2010). The quantile regression results are consistent with the OLS estimates at all deciles, indicating no differences for high-, mean-, and low-productivity firms.

5. Discussion

The presented results provide new and original micro-evidence on firm performance in the context of a developing or emerging economy. The originality and novelty of our findings stem from various sources.

First, this is one of the first studies showing empirical evidence of a positive and significant impact of international standard certifications on labour productivity of Vietnamese SMEs operating in the manufacturing sector. Relying on a relatively recent body of management literature (Bloom et al. Citation2013), we directly relate the higher labour productivity of certified firms with the adoption of improved managerial and operational practices implied by standard adherence.

Moreover, the certification-induced reconfiguration and re-organization of internal procedures allows equating the adoption of international management certifications with organizational innovation. As observed by Cozzarin, Kim, and Koo (Citation2017), organizational change affects labour productivity by modifying firm routines, which is what defines and shapes firm behaviour and, ultimately, performance. In this respect, we can relate our results to the empirical literature on organizational innovation, arguing that the found evidence of a positive impact of international standard certifications is in line with the positive direct productivity effect of organizational innovation presented in various empirical works (Polder et al. Citation2010; Cozzarin, Kim, and Koo Citation2017). Controlling for technological innovation, we also contribute to the empirical literature according to which technological innovation is not the only innovation that matters for firm performance.

In fact, as international standards codify knowledge about management systems and operational procedures, it is likely that the internal learning processes taking place with the adherence to management standards might favour the development of capabilities, potentially resulting in higher productivity. The effect of standards on human resource management may result in better employment conditions and benefits, including health, safety, and other non-wage benefits. Various studies have indeed documented positive effects of standards on working conditions (Blunch and Castro Citation2005; Levine and Toffel Citation2010; Trifković Citation2017). Our findings are clearly in line with these studies, which help understand the underlying mechanisms of how labour productivity is raised through standards adherence.

Second, thanks to the availability of panel data, our work goes beyond traditional cross-section analyses, thus addressing one of the main limitations of most existing studies for developing countries. The coefficients for standard obtained in IVs estimations are larger than the ones found in OLS, thus pointing towards a downward bias in the OLS estimation. This is also consistent with the results of the implementation of a sensitivity analysis to omitted variable bias of the coefficients of standard and innovation. This bias could arise if unobserved factors correlate positively with the adoption but negatively with productivity, such as, for example, when firms with weaker managerial capabilities seek to improve their performance through standards (Trifković Citation2017). This is consistent with the finding that firms in developing countries tend to be generally poorly managed (Bloom and Van Reenen Citation2007, Citation2010; Bloom et al. Citation2013), and that the adoption of an international management standard could actually help them upgrade their managerial and operational procedures and ultimately their productivity, especially since surrounding firms are also badly managed and thus cannot represent any better model.

Third, we look at the impact of certification over split samples of innovators and non-innovators (). The larger positive and significant effect of standards found for innovators leads us to argue that some unobservable factors associated with technological innovation may reinforce the positive effect of standard on productivity. Our results seem to suggest that, even controlling for their skills and human capital, innovative firms benefit more from the managerial and operational improvements required by standard adherence, thus obtaining more advantages in terms of efficiency gains than non-innovating certified firms.

Finally, the analysis of industry and location effects provides additional insight to the presence of heterogeneous effects of standards and innovation on productivity. We find a larger effect in the Southern provinces, effect that we associate with interaction with customers from advanced countries. We also find that the effect of standard is not equal across industries, being larger for firms operating in scale and information-intensive industries which benefit more from better coordination and management practice.

6. Concluding remarks

This work presents original findings on the effects of the adherence to international management standards on firm productivity in the Vietnamese manufacturing sector. Besides contributing to enrich the relevant empirical literature, these findings may have some relevant implications for the performance of micro, small, and medium enterprises in the Vietnamese manufacturing sector. Viet Nam’s manufacturing sector bears contemporary similarities to a large number of developing countries, which makes the findings highly relevant for other regional and extra-regional stakeholders.

By providing new evidence on the impact of standards certifications on productivity at the micro level, our results further support the argument that ‘stimulating adherence to world standards may be an important component in industrial policy’ (Goedhuys and Mohnen Citation2017, 13), especially in the attempt to move forward from capital-intensive growth strategies, such as could be the case for Viet Nam and for other Asian emerging economies. Our work also suggests that targeting support towards innovative firms in applying for and obtaining certifications may provide a larger contribution to raise productivity, given the fact that these firms seem to benefit relatively more from standard adherence. Moreover, the found evidence of heterogeneous effects of standards across industries indicates the necessity of taking into account industry-specific non-technological features to effectively foster labour productivity. Lastly, the design and implementation of policy interventions aimed at fostering certification should also take into account the empirical evidence regarding what makes it more likely for a firm to be certified. In this respect, our results are consistent with many studies on adoption, agreeing on the fact that the cost of standards still represents a relevant barrier, especially for SMEs.

We are aware of the limitations of this work. We acknowledge that the proposed comparison of the effect of standard certification for innovating and non-innovating firms does not allow us to properly disentangle the mechanisms through which their relationship affects productivity. Further empirical research with larger samples and containing larger firms would be needed to shed more light on the interplay between these two factors and their ultimate effect on firm productivity. Finally, like most of the existing empirical studies, we concentrate on the family of international management standards, mainly ISO 9001 (and, to a lesser extent, ISO 14001). Future studies could distinguish and estimate the effect of different types of standards, for example, product standards and environmental regulations, and also take into account that domestic and local standards may matter even more for SMEs or serve as an intermediate step to acquire knowledge on world class practice in the management of production processes.

Acknowledgements

This study was originally commissioned by UNU-WIDER in Helsinki, within the ‘Structural transformation and inclusive growth in Viet Nam’ research project. The authors are grateful to Prof. John Rand and to the participants of the workshop ‘Mirco, small, and medium enterprises in Viet Nam’ (Central Institute of Economic Management, Ha Noi, 8 November 2016) for the useful feedbacks and comments. The authors are also thankful to Prof. Pierre Mohnen for his advice, and to the participants to the internal seminars at SPRU (University of Sussex) and UNU-MERIT for their comments. The usual caveats apply.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1. Bloom and Van Reenen (Citation2007) measure management practices by assigning a score to 18 key management categories, which are related to ‘good management’ factors, such as: structure and rationale of production processes, documentation, performance tracking and assessing, setting targets, and human capital management (6 out of 18 categories refer to human capital). These categories are directly comparable with the principles of international management standard, such as the family of ISO management system standards.

2. See Marimon Viadiu, Casadesús Fa, and Heras-Saizarbitoria (Citation2006) for an analysis of worldwide diffusion and adoption of the ISO 9001 and ISO 14001 standards. For more information about the features, requirements, and purposes of ISO 9001:2008 and the new ISO 9001:2015, see ISO (Citation2016).

3. This variable is obtained from a question whose answer is not conditional on having declared to have a standard certification. One could be concerned that if firms supply to multinational enterprises (MNEs), this variable may be both correlated with certification (as MNEs tend to require certification from their local suppliers to shelter themselves from activist groups in end markets claiming corporate social behaviour) and productivity (as MNEs select their suppliers on productivity performance). However, in our sample, only 4.4% of firms sell some part of their output to a foreign-owned firm, with the average share of sales of 1.2%, so we think this issue may not be of great concern here. We also tested this formally, and the instrumental variable was not significant in the productivity equation.

4. The variable is obtained by interacting province-sector (4-digit) share of standards with social network size and the rate of internet use by firms at the district-sector (2-digit) level. The province-sector share of standards is the share of standards in each province-sector (4-digit) in the two-year average number of all ISO certificates issued in Viet Nam.

5. Underlying this approach is the notion that discrete endogenous variables are generated by continuous latent variables crossing thresholds (Heckman Citation1978), which has found a wide application in the threshold (sample splitting) models with and without endogenous variables (Hansen Citation2000; Caner and Hansen Citation2004). An alternative approach would be to use the interaction term between standards certification and technological innovation and estimate on the full sample, but this would require finding a suitable instrument for the interaction term. As we were unable to find a suitable instrument for innovation or the interaction between standard and innovation, we have chosen to analyse differences in sub-samples with and without technological innovation.

6. We could not use all four Pavitt categories, since there are few observations falling into sectors classified as Science Based (SB) and Specialized Suppliers (SS), which occupy the upper levels in the technological leadership hierarchy of Pavitt taxonomy. Thus, the 5% of firms operating in ‘Chemicals and chemical products’ or in ‘Electronic machinery and devices, computers, radio etc. … ’ are included in SII and SD industries, respectively, as the activities performed in these two sectors are not likely to be based on R&D, nor engineering and design skills, as implied by the original Pavitt’s definition of SB and SS industries.

7. The questions about innovation relate to product or process innovations and product improvements that have occurred in the past two years. They indicate activities new to the firm, not the market or the world. A firm is considered a product innovator if it has introduced a product in a sector (at the 4-digit level of International Standard Industrial Classification) where it did not have products previously.

8. All monetary values are normalized to 2010 VND using the GDP deflator information from World Bank Data.

9. See Trifković (Citation2016) for more details on the sectorial pattern of international standard certifications.

10. We also considered splitting the sample by certification to analyse the effect of technological innovation for firm certified and non-certified firms, but the limited number of certified firms has not allowed performing such an analysis.

References

- Aboal, D., and P. Garda. 2016. “Technological and Non-Technological Innovation and Productivity in Services Vis-à-Vis Manufacturing Sectors.” Economics of Innovation and New Technology 25 (5): 435–454. doi: 10.1080/10438599.2015.1073478

- Arellano, M., and S. Bond. 1991. “Some Tests of Specification for Panel Data: Monte Carlo Evidence and an Application to Employment Equations.” The Review of Economic Studies 58 (2): 277–297. doi: 10.2307/2297968

- Armbruster, H., A. Bikfalvi, S. Kinkel, and G. Lay. 2008. “Organizational Innovation: The Challenge of Measuring Non-Technical Innovation in Large-Scale Surveys.” Technovation 28 (10): 644–657. doi: 10.1016/j.technovation.2008.03.003

- Baum, C. F., H. Lööf, P. Nabavi, and A. Stephan. 2017. “A New Approach to Estimation of the R&D–Innovation–Productivity Relationship.” Economics of Innovation and New Technology 26 (1–2): 121–133. doi: 10.1080/10438599.2016.1202515

- Bellows, J., and E. Miguel. 2009. “War and local Collective Action in Sierra Leone.” Journal of Public Economics 93 (11): 1144–1157. doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2009.07.012

- Benavente, J. M. 2006. “The Role of Research and Innovation in Promoting Productivity in Chile.” Economics of Innovation and New Technology 15 (4–5): 301–315. doi: 10.1080/10438590500512794

- Bloom, N., B. Eifert, A. Mahajan, D. McKenzie, and J. Roberts. 2013. “Does Management Matter? Evidence from India.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 128 (1): 1–51. doi: 10.1093/qje/qjs044

- Bloom, N., and J. Van Reenen. 2007. “Measuring and Explaining Management Practices Across Firms and Countries.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 122 (4): 1351–1408. doi: 10.1162/qjec.2007.122.4.1351

- Bloom, N., and J. Van Reenen. 2010. “Why Do Management Practices Differ Across Firms and Countries?” Journal of Economic Perspectives 24 (1): 203–224. doi: 10.1257/jep.24.1.203

- Blunch, N.-H., and P. Castro. 2005. Multinational Enterprises and Training Revisited: Do International Standards Matter? Social Protection Discussion Paper Series 32546. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Bogliacino, F., V. Cirillo, and D. Guarascio. 2017. “The Dynamics of Profits and Wages: Technology, Offshoring and Demand.” Industry and Innovation, forthcoming (http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13662716.2017.1349651).

- Bogliacino, F., M. Lucchese, L. Nascia, and M. Pianta. 2017. “Modeling the Virtuous Circle of Innovation. A Test on Italian Firms.” Industrial and Corporate Change 26 (3): 467–484.

- Bogliacino, F., G. Perani, M. Pianta, and S. Supino. 2012. “Innovation and Development: The Evidence from Innovation Surveys.” Latin American Business Review 13 (3): 219–261. doi: 10.1080/10978526.2012.730023

- Bogliacino, F., and M. Pianta. 2013. “Profits, R&D, and Innovation – A Model and a Test.” Industrial and Corporate Change 22 (3): 649–678. doi: 10.1093/icc/dts028

- Bogliacino, F., and M. Pianta. 2016. “The Pavitt Taxonomy, Revisited: Patterns of Innovation in Manufacturing and Services.” Economia Politica 33: 153–180. doi: 10.1007/s40888-016-0035-1

- Camisón, C., and A. Villar-López. 2014. “Organizational Innovation as an Enabler of Technological Innovation Capabilities and Firm Performance.” Journal of Business Research 67 (1): 2891–2902. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2012.06.004

- Caner, M., and B. E. Hansen. 2004. “Instrumental Variable Estimation of a Threshold Model.” Econometric Theory 20 (5): 813–843. doi: 10.1017/S0266466604205011

- Chudnovsky, D., A. López, and G. Pupato. 2006. “Innovation and Productivity in Developing Countries: A Study of Argentine Manufacturing Firms’ Behavior (1992–2001).” Research Policy 35 (2): 266–288. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2005.10.002

- CIEM, DoE, ILSSA, and UNU-WIDER. 2016. Characteristics of the Vietnamese Business Environment. Evidence from a SME Survey in 2015. Hanoi: Central Institute of Economic Management (CIEM).

- Coad, A., and R. Rao. 2008. “Innovation and Firm Growth in High-Tech Sectors: A Quantile Regression Approach.” Research Policy 37 (4): 633–648. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2008.01.003

- Cozzarin, B. P., W. Kim, and B. Koo. 2017. “Does Organizational Innovation Moderate Technical Innovation Directly or Indirectly?” Economics of Innovation and New Technology 26 (4): 385–403. doi: 10.1080/10438599.2016.1203084

- Crépon, B., E. Duguet, and J. Mairesse. 1998. “Research, Innovation and Productivity: An Econometric Analysis at the Firm Level.” Economics of Innovation and New Technology 7 (2): 115–158. doi: 10.1080/10438599800000031

- Delmas, M. A., and S. Pekovic. 2013. “Environmental Standards and Labor Productivity: Understanding the Mechanisms That Sustain Sustainability.” Journal of Organizational Behavior 34 (2): 230–252. doi: 10.1002/job.1827

- Djupdal, K., and P. Westhead. 2015. “Environmental Certification as a Buffer Against the Liabilities of Newness and Smallness: Firm Performance Benefits.” International Small Business Journal 33 (2): 148–168. doi: 10.1177/0266242613486688

- Gebreeyesus, M. 2015. “Firm Adoption of International Standards: Evidence from the Ethiopian Floriculture Sector.” Agricultural Economics 46 (S1): 139–155. doi: 10.1111/agec.12203

- Goedhuys, M., N. Janz, and P. Mohnen. 2008. “What Drives Productivity in Tanzanian Manufacturing Firms: Technology or Business Environment?” European Journal of Development Research 20: 199–218. doi: 10.1080/09578810802060785

- Goedhuys, M., and P. Mohnen. 2017. “Management Standard Certification and Firm Productivity: Micro-Evidence from Africa.” Journal of African Development 19 (1): 61–83.

- Goedhuys, M., and L. Sleuwaegen. 2010. “High-Growth Entrepreneurial Firms in Africa: A Quantile Regression Approach.” Small Business Economics 34 (1): 31–51. doi: 10.1007/s11187-009-9193-7

- Goedhuys, M., and L. Sleuwaegen. 2013. “The Impact of International Standards Certification on the Performance of Firms in Less Developed Countries.” World Development 47: 87–101. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2013.02.014

- Goedhuys, M., and L. Sleuwaegen. 2016. “International Standards Certification, Institutional Voids and Exports from Developing Country Firms.” International Business Review 25 (6): 1344–1355. doi: 10.1016/j.ibusrev.2016.04.006

- González, P., J. Sarkis, and B. Adenso-Díaz. 2008. “Environmental Management System Certification and its Influence on Corporate Practices: Evidence from the Automotive Industry.” International Journal of Operations & Production Management 28 (11): 1021–1041. doi: 10.1108/01443570810910179

- Gray, J. V., G. Anand, and A. V. Roth. 2015. “The Influence of ISO 9000 Certification on Process Compliance.” Production and Operations Management 24 (3): 369–382. doi: 10.1111/poms.12252

- Gunday, G., G. Ulusoy, K. Kilic, and L. Alpkan. 2011. “Effects of Innovation Types on Firm Performance.” International Journal of Production Economics 133 (2): 662–676. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpe.2011.05.014

- Hansen, B. E. 2000. “Sample Splitting and Threshold Estimation.” Econometrica 68 (3): 575–603. doi: 10.1111/1468-0262.00124

- Hansen, H., and N. Trifković. 2014. “Food Standards are Good – For Middle-Class Farmers.” World Development 56: 226–242. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2013.10.027

- Heckman, J. J. 1978. “Dummy Endogenous Variables in a Simultaneous Equation System.” Econometrica 46 (4): 931–959. doi: 10.2307/1909757

- Heras-Saizarbitoria, I., and O. Boiral. 2013. “ISO 9001 and ISO 14001: Towards a Research Agenda on Management System Standards.” International Journal of Management Reviews 15 (1): 47–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2370.2012.00334.x

- Howard, E., C. Newman, J. Rand, and F. Tarp. 2014. Productivity-Enhancing Manufacturing Clusters: Evidence from Vietnam. WIDER Working Paper 2014/071. Helsinki: UNU-WIDER.

- Hudson, J., and M. Orviska. 2013. “Firms’ Adoption of International Standards: One Size Fits All?” Journal of Policy Modeling 35 (2): 289–306. doi: 10.1016/j.jpolmod.2012.04.001

- ISO (International Organization for Standardization). 2016. “ISO 9001 Quality Management Systems – Revision.” Accessed March 14, 2017. https://www.iso.org/iso-9001-revision.html.

- King, A. A., M. J. Lenox, and A. Terlaak. 2005. “The Strategic use of Decentralized Institutions: Exploring Certification with the ISO 14001 Management Standard.” Academy of Management Journal 48 (6): 1091–1106. doi: 10.5465/amj.2005.19573111

- Lannelongue, G., J. Gonzalez-Benito, and O. Gonzalez-Benito. 2015. “Input, Output, and Environmental Management Productivity: Effects on Firm Performance.” Business Strategy and the Environment 24 (3): 145–158. doi: 10.1002/bse.1806

- Levine, D. I., and M. W. Toffel. 2010. “Quality Management and Job Quality: How the ISO 9001 Standard for Quality Management Systems Affects Employees and Employers.” Management Science 56 (6): 978–996. doi: 10.1287/mnsc.1100.1159

- Lööf, H., J. Mairesse, and P. Mohnen. 2017. “CDM 20 Years After.” Economics of Innovation and New Technology 26 (1–2): 1–5. doi: 10.1080/10438599.2016.1202522

- Lu, C.-S., A. Chen, and L. Kao. 2017. “How Product Market Competition and Complexity Influence the On-Job-Learning Effect and Entrenchment Effect of Board Tenure.” International Review of Economics & Finance 50: 175–195. doi: 10.1016/j.iref.2017.04.002

- Lucas, R. E. 1988. “On the Mechanics of Economic Development.” Journal of Monetary Economics 22 (1): 3–42. doi: 10.1016/0304-3932(88)90168-7

- Marimon Viadiu, F., M. Casadesús Fa, and I. Heras-Saizarbitoria. 2006. “ISO 9000 and ISO 14000 Standards: An International Diffusion Model.” International Journal of Operations & Production Management 26 (2): 141–165. doi: 10.1108/01443570610641648

- McCaig, B., and N. Pavcnik. 2013. Moving Out of Agriculture: Structural Change in Vietnam. NBER Working Paper Series 19616. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Mohnen, P., and B. H. Hall. 2013. “Innovation and Productivity: An Update.” Eurasian Business Review 3 (1): 47–65.

- Morrison, A., C. Pietrobelli, and R. Rabellotti. 2008. “Global Value Chains and Technological Capabilities: A Framework to Study Learning and Innovation in Developing Countries.” Oxford Development Studies 36 (1): 39–58. doi: 10.1080/13600810701848144

- Mothe, C., U. T. Nguyen-Thi, and P. Nguyen-Van. 2015. “Complementarities in Organizational Innovation Practices: Evidence from French Industrial Firms.” Economics of Innovation and New Technology 24 (6): 569–595. doi: 10.1080/10438599.2014.949416

- Nair, A. 2006. “Meta-analysis of the Relationship Between Quality Management Practices and Firm Performance—Implications for Quality Management Theory Development.” Journal of Operations Management 24 (6): 948–975. doi: 10.1016/j.jom.2005.11.005

- Nguyen, V. C. 2014. Do Minimum Wages Affect Firms’ Labor and Capital? Evidence from Vietnam. IPAG Business School Working Paper. Paris: IPAG Business School.

- O’Brien, K. 2016. “Is Newest Always Best? Firm-Level Evidence to Challenge a Focus on High-Capability Technological (Product or Process) Innovation.” Economics of Innovation and New Technology 25 (8): 747–768. doi: 10.1080/10438599.2016.1147194

- OECD. 2005. Oslo Manual. Guidelines for Collecting and Interpreting Innovation Data. Paris: OECD.

- Oster, E. 2016. “Unobservable Selection and Coefficient Stability: Theory and Evidence.” Journal of Business & Economic Statistics. doi:10.1080/07350015.2016.1227711.

- Parisi, M. L., F. Schiantarelli, and A. Sembenelli. 2006. “Productivity, Innovation and R&D: Micro Evidence for Italy.” European Economic Review 50: 2037–2061. doi: 10.1016/j.euroecorev.2005.08.002

- Pavitt, K. 1984. “Sectoral Patterns of Technical Change: Towards a Taxonomy and a Theory.” Research Policy 13 (6): 343–373. doi: 10.1016/0048-7333(84)90018-0

- Peters, B., M. J. Roberts, and V. A. Vuong. 2017. “Dynamic R&D Choice and the Impact of the Firm’s Financial Strength.” Economics of Innovation and New Technology 26 (1–2): 134–149. doi: 10.1080/10438599.2016.1202516

- Polder, M., G. V. Leeuwen, P. Mohnen, and W. Raymond. 2010. “Product, Process and Organizational Innovation: Drivers, Complementarity and Productivity Effects.” UNU-MERIT Working Paper, 2010-35.

- Potoski, M., and A. Prakash. 2009. “Information Asymmetries as Trade Barriers: ISO 9000 Increases International Commerce.” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 28 (2): 221–238. doi: 10.1002/pam.20424

- Rand, J., and N. Torm. 2012. “The Benefits of Formalization: Evidence from Vietnamese Manufacturing SMEs.” World Development 40 (5): 983–998. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2011.09.004

- Romer, P. M. 1986. “Increasing Returns and Long-Run Growth.” Journal of Political Economy 94 (5): 1002–1037. doi: 10.1086/261420

- Sadikoglu, E., and C. Zehir. 2010. “Investigating the Effects of Innovation and Employee Performance on the Relationship Between Total Quality Management Practices and Firm Performance: An Empirical Study of Turkish Firms.” International Journal of Production Economics 127 (1): 13–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpe.2010.02.013

- Sampaio, P., P. Saraiva, and A. Guimarães Rodrigues. 2009. “ISO 9001 Certification Research: Questions, Answers and Approaches.” International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management 26 (1): 38–58. doi: 10.1108/02656710910924161

- Scott, M. 1989. A New View of Economic Growth. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Tavassoli, S., and C. Karlsson. 2016. “Innovation Strategies and Firm Performance: Simple or Complex Strategies?” Economics of Innovation and New Technology 25 (7): 631–650. doi: 10.1080/10438599.2015.1108109

- Terlaak, A., and A. A. King. 2006. “The Effect of Certification with the ISO 9000 Quality Management Standard: A Signaling Approach.” Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 60 (4): 579–602. doi: 10.1016/j.jebo.2004.09.012

- Trifković, N. 2016. Private Standards and Labour Productivity in the Food Sector in Viet Nam. WIDER Working Paper 2016/163. Helsinki: UNU-WIDER.

- Trifković, N. 2017. “Spillover Effects of International Standards: Working Conditions in the Vietnamese SMEs.” World Development. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.03.040.

- Windmeijer, F. 2005. “A Finite Sample Correction for the Variance of Linear Efficient Two-Step GMM Estimators.” Journal of Econometrics 126 (1): 25–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jeconom.2004.02.005

- Yu, X., G. Dosi, M. Grazzi, and J. Lei. 2017. “Inside the Virtuous Circle Between Productivity, Profitability, Investment and Corporate Growth: An Anatomy of Chinese Industrialization.” Research Policy 46: 1020–1038. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2017.03.006

- Zanello, G., X. Fu, P. Mohnen, and M. Ventresca. 2016. “The Creation and Diffusion of Innovation in Developing Countries: A Systematic Literature Review.” Journal of Economic Surveys 30 (5): 884–912. doi: 10.1111/joes.12126

- Zoo, H., H. J. de Vries, and H. Lee. 2017. “Interplay of Innovation and Standardization: Exploring the Relevance in Developing Countries.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 118: 334–348. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2017.02.033