ABSTRACT

Assessing vulnerability is an international priority area across law enforcement and public health (LEPH). Most contacts with frontline law enforcement professions now relate to ‘vulnerability’; frontline health responders are experiencing a similar increase in these calls. To the authors’ best knowledge there are no published, peer-reviewed tools which specifically focus on assessing vulnerability, and which are specifically designed to be applicable across the LEPH frontline. This systematic review synthesised 33 eligible LEPH journal articles, retaining 18 articles after quality appraisal to identify assessment guidelines, tools, and approaches used relevant to either law enforcement and/or public health professions. The review identifies elements of effective practice for the assessment of vulnerability, aligned within four areas: prevention, diversion/triage, specific interventions, and training across LEPH. It also provides evidence that inter-professional/integrated working, shared training, and aligned systems are critical to effective vulnerability assessment. This systematic review reports, for the first time, effective practices in vulnerability assessment as reported in peer-reviewed papers and provides evidence to inform better multi-agency policing and health responses to people who may be vulnerable.

Introduction

One of the leading national priorities in Scotland is the imperative to appropriately respond to and effectively assess people who may have ‘vulnerabilities’ (Murray et al. Citation2018, Citation2021). This stance is echoed in the UK and beyond (Kesic et al. Citation2019, National Police Chief’s Council Citation2018, Scottish Government Citation2017). However, as demonstrated in a recent scoping review of the LEPH literature, there is no consensus definition of vulnerability (Enang et al. Citation2019). In more recent work within Scotland which aimed to develop a national agenda around LEPH research and partnership working, vulnerability assessment was deemed a top priority and a broad definition of vulnerability was proposed: ‘everyone can be vulnerable and this will vary depending on the context, the situation and across the person’s lifespan’ (Murray et al. Citation2021, p. 11).

Police responding to calls involving people who are vulnerable is particularly pertinent in the context of austerity, or a pandemic, where the functioning of wider health and social services and from within the community may be limited. The role of police in the UK as a ‘secret social service’ has been acknowledged for quite some time (Punch Citation1979). Wood and Watson (Citation2017) argued that advancements have been made in shifting the knowledge and attitudes of officers beyond their law enforcement role, towards a role as mental health interventionists. Regardless of where the emphasis is at any point in time regarding which ‘core’ functions the police should focus on, it is likely that they will frequently come across and need to assess people with vulnerabilities.

Scotland is a country with a population in the region of 5.5 million, and in 2018 alone, there were 570 incidents added to the Police Scotland Vulnerable Person’s Database every day: totalling 208,050 in the year (Bell Citation2019). An estimated 80% of calls to the police in Scotland, and across the UK, relate to vulnerability (Graham Citation2017). In 2016, Police Scotland received over 3.4 million calls and attended over 900,000 incidents, with only one-fifth of these resulting in a crime being recorded (Graham Citation2017). These calls are often around mental health distress or other public health related concerns (Policing Citation2026, Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire & Rescue Services Citation2018, Sondhi and Williams Citation2018). Examples include substance use problems (Burris and Burrows Citation2009, Jardine et al. Citation2012), missing persons (Woolnough Citation2019, Bell Citation2019), distress and suicidal behaviour (Bell Citation2019, Dougall et al. Citation2020a, Citation2020b, Kesic et al. Citation2019), and care of the elderly (Bows Citation2018).

This issue is not restricted to the UK. Similar figures in Canada demonstrate that calls to the police around mental health distress and vulnerability account for 20% of non-crime calls and people with a mental health problem are four times more likely to be arrested (Boyce et al. Citation2015). Durham Regional Police Services (DRPS) saw an increase of 50% in mental health related calls between 2012 and 2017 (DRPS Citation2017). In tandem, the number of presentations for mental distress, suicide, and related self-harm presentations to the Emergency Department and ambulance services have also risen (Dougall et al. Citation2014, Duncan et al. Citation2019, Keown Citation2013). In Scotland alone, there was an observed 15% increase in recorded suicide rates of people in 2018 (Dougall et al. Citation2020a, Citation2020b, The Scottish Public Health Observatory Citation2019). Assessing vulnerability therefore is important for the police, who frequently are required to assist people in mental distress (Dougall et al. Citation2020a, Citation2020b, Enang et al. Citation2019, Kesic et al. Citation2019).

People contacting and presenting across LEPH services are often the same individuals (HMICFRS Citation2018, van Dijk, et al. Citation2019). The practice of contacting multiple LEPH services for similar or the same issues is complex and may indicate: (1) absence of joined-up service provision and communication; (2) absence of appropriate assessment, care management planning, and/or safety planning on first presentation; and/or (3) multiple co-morbidities and social care issues requiring a cross-service response which is absent, or perceived to be absent (Christmas et al. Citation2018, Citation2019).

It is imperative that LEPH frontline staff is supported to work in an integrated manner when tackling issues that are situated within public service systems (Cristofoli et al. Citation2017). This includes, but is not limited to: incorporating shared values, definitions of complex constructs; training; policies; and approaches where possible (Bartkowiak-Théron and Asquith Citation2017, Dougall et al. Citation2020a, Citation2020b, Enang et al. Citation2019, HM Government Citation2014, Kesic et al. Citation2019, Murray et al. Citation2021). These can then be used to guide the assessment and management of people who may be considered vulnerable in a person-centred manner when interacting with services.

The overarching aim of the current review is to identify effective components of vulnerability assessment across LEPH. Prior to this, however, greater discussion around the current context and understandings of ‘vulnerability’ must first be presented, to underpin what we mean by vulnerability within our work and what is meant by vulnerability within the published LEPH literature.

The vulnerability context so far

The term ‘vulnerability’ has been controversial. Some professions now label vulnerability as ‘complex needs’, with vulnerability considered as either synonymous with complex needs and/or as a component of complex needs (Department for Communities and Local Government Citation2015, Iacono Citation2014, Whitehurst Citation2007). The controversial use of the term vulnerability may exist because some consider it as stigmatising/patronising when taken from the ‘inherently vulnerable’ perspective, or from a dislike of the implication that it may be disempowering or foster dependency (Brown Citation2017). In Scotland, there has been debate around the use of the word vulnerable within legislation supporting adults who may be at risk of harm. An agreed core principle of the Adult Support and Protection (Scotland) Act 2007 saw the word vulnerable removed from the title in recognition that the presence of a condition or situation does not automatically mean that an individual is an ‘adult at risk’. The current review chose to maintain the use of vulnerable over ‘complex needs’ to best align to the language used previously and across LEPH professions, policy and strategy documents, and the international literature.

Vulnerability is a term used commonly across LEPH practice, but one that is poorly defined (Asquith et al. Citation2017, Keay and Kirby Citation2018, Enang et al. Citation2019). When attempting to identify a unified definition of vulnerability in the LEPH context, Enang et al. (Citation2019) found only four definitions across the shared literature, and all were too context-specific to apply broadly across the assessment of vulnerability within LEPH. Given the complexity of the term itself and the application of it within LEPH, we are clear that people are not inherently vulnerable and should not be labelled as such across all situations (Enang et al. Citation2019, Murray et al. Citation2021).

Considering the fragmented definitions of vulnerability that currently exist within the LEPH community, we propose a more inclusive and holistic working definition of vulnerability. Within the context of the current review, we define a person with vulnerability as: ‘one whose physical, mental, or social well-being is challenged, and/or one who is unable to access support at a particular time’. Used in this context, the word ‘challenged’ refers to a situation where a person’s physical, mental, and/or social well-being may be compromised.

The complexities associated with assessing vulnerability across LEPH professions are also numerous. They include the nature of definitions of vulnerability; the operational responses and processes used across LEPH professional groups; behavioural responses of LEPH professional groups (separately and in consort); the number of different groups of people involved; the different levels of response and seniority required; the attributes of physical/ personal, social/family and environmental characteristics; and the number, nature, and variability of the potential outcomes (Keay and Kirby Citation2018). The authors emphasise that no single model, tool, or training on vulnerability can possibly cover all these variables and outcomes, nor, possibly, should they. However, identifying empirically supported elements of vulnerability assessment shared across LEPH, can potentially inform the future development of evidence-informed assessment and training.

The current paper builds on previous work. First, it responds to Murray et al.’s (Citation2021) call to critically consider vulnerability assessment as a LEPH priority. Second, it attempts to bridge the gap identified by a scoping review of the LEPH literature on the need to understand how vulnerability is defined and assessed across LEPH (Enang et al. Citation2019). Accordingly, the overarching aim of the current systematic review is to identify effective components of vulnerability assessment across published, peer-reviewed LEPH literature. The key research question that will be addressed in this review is: How has vulnerability been assessed across LEPH organisations in countries belonging to the Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)?

Methods

The systematic review follows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) methodology (Moher et al. Citation2009). The methods, search strategy and inclusion/exclusion criteria used were explicit to allow replication. The definition of vulnerability was purposefully broad, encompassing both situational/contextual and intrinsic/person-specific aspects, and representing the definitions and approaches to vulnerability across LEPH agencies, to obtain potential evidence, and what it means to be deemed as vulnerable. The literature search was not restricted by professional classifications of journals or on LEPH professional groups (see eligibility criteria below). As the papers identified were heterogenous in their methods, a modified narrative synthesis framework for mixed-methods reviews was used during the quality appraisal, data extraction, and data synthesis (Popay et al. Citation2006). The search strategy involved searches of the electronic bibliographic databases using the EBSCO Platform, including Psychological Information Database, Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval Systems Online, Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature, and Criminology Collection, and Sociology Collection.

Search strategy filters comprised relevant terms and synonyms which were combined using the BOOLEAN operators ‘OR’ and ‘AND’ (see Appendices 1 and 2). Searches were conducted on Title and Abstract search fields. Hand searching of the reference lists of included papers was applied to identify any potentially missed papers. Articles published between 2000 and 2018 were included in the review. The year 2000 was selected as the lower limit because the Adults with Incapacity (Scotland) Act 2000 was passed then, and this review set out to address a national priority of Scotland. The year 2018 is the upper limit because the literature search was conducted at that time.

To support the validity and relevance of this review, an Expert Advisory Group (EAG) was consulted. This group supported the co-creation of the research priorities (Murray et al. Citation2018, Citation2021), the design of this review, and the interpretation of findings. The EAG consists of 26 senior level stakeholders across LEPH professions and people with lived experience (see Murray et al. Citation2018, for further details). For the current review, a sub-set of six responders from the EAG actively advised.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Retrieved articles were included if they directly related to (a) vulnerability and its assessment; (b) adult population above 16 years old who use/access LEPH facilities; and (c) LEPH professional groups were included. The choice to categorise adults as aged 16 years and over stems from legislation in some OECD countries, including Scotland, which use this threshold to define adulthood (e.g. Adult Support and Protection (Scotland) Act 2007 (The National Archives Citation2007). Studies from only OECD countries were included as they typically have similar political, legislative and socio-economic structures that shape the development and implementation of LEPH, allowing better comparison. Only articles published in English were included because there was no multilingual researcher in the team, and our resources were finite. To ensure high levels of validity and originality, only peer-reviewed articles were included in the review (Kelly et al. Citation2014); book chapters and reviews, research commentaries and non-peer-reviewed articles were excluded. While including grey literature would have elicited a broader set of interventions being undertaken by LEPH agencies around vulnerability, it was decided to include only published peer-review articles in this systematic review as a first line in establishing the evidence base. Since the current review aims to identify components of vulnerability assessment, article titles, abstracts and keywords unrelated to vulnerability were excluded; papers had to explicitly discuss vulnerability to be included rather than related concepts. Papers of any type were retained for full text review, including empirical research, literature reviews, theoretical contributions, and published protocols.

Search strategy

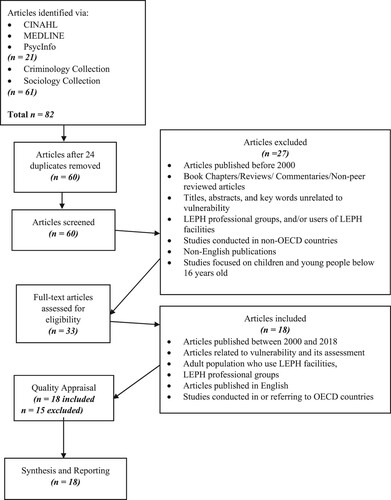

As depicted in , 82 articles were identified following database searching.

Using the EBSCO platform, 21 articles were retrieved from Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature, Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval Systems Online, and Psychological Information Database. From the Criminology and Sociology Collections on the ProQuest platform, 61 articles were retrieved. Sixty articles remained after removing 22 duplicates, and these were screened for eligibility. Twenty-seven articles were excluded based on the exclusion criteria, leaving 33 eligible full text articles. Fifteen articles were excluded after quality appraisal, leaving 18 articles for further synthesis.

Of the 18 included papers, two had a public health focus (incorporating health and social care contexts), 15 had a predominantly law enforcement focus (including criminal justice, law enforcement, and court liaison contexts), and only one was a combination of LEPH contexts (public sector focus). Six papers involved UK settings, six were based in the USA, five in Australia, and one in the Netherlands. A full breakdown of the scope of the papers and their contextual factors can be found in .

Table 1. Overview of Included Studies.

Screening, quality appraisal and data synthesis

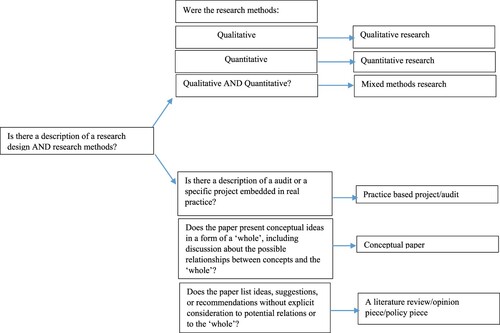

Duplicate papers returned across databases were removed. The remaining articles were first screened by IE, by title, and then by the remaining abstracts. The remaining papers were read in full and included/excluded based on the study’s eligibility criteria. Due to the heterogeneity of the data and methods used in the remaining included papers, papers were categorised into one of five mutually exclusive categories, in line with Kolehmainen et al.’s (Citation2010) classifications (): quantitative research (N = 5); qualitative research (N = 2); mixed-methods research (N = 4); practice-based project/audit (N = 2); opinion/literature review/policy paper (the published protocol [Coulton et al. Citation2017] was included in this grouping for quality appraisal purposes) (N = 5).

Figure 2. Classification of papers into categorical domains, based on Kolehmainen et al. (Citation2010).

Author 1 assessed quality appraisal of all 18 full texts, with a random sample of nine papers cross-checked by Authors 2, 4, and 7. Within each of the paper categories, quality was assessed using descriptive checklists based on the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination of Research (Citation2009), adapted by Duncan and Murray (Citation2012). Quality appraisal included judgements according to five assessment criteria: appropriate methods; description of data collection; description of data analysis; data quality; and sampling methods (). An assessment returning a nil value meant the article did not meet any of the five assessment criteria; while 1+ and 5+ meant an article had fully addressed at least one or all five of the assessment criteria, respectively. Articles that partly addressed assessment criteria were allocated 0.5+ per assessment criteria. Most papers scored highly in the quality appraisal. The findings from the current review were therefore derived from studies with appropriate designs, methods, description of data collection and analysis, and good quality of data as per our assessment criteria.

Table 2. Quality appraisal scoring and number of papers in each category.

Included articles were critically analysed and synthesised following published narrative analysis guidelines (Popay et al. Citation2006) using an inductive approach, and using NVivo 11 to support the analysis in identifying effective components of vulnerability assessment. The key findings for each paper were extracted by Author 1, and a random square root sample of papers were blind cross-checked by Author 2 for agreement. Key findings were discussed, and any differences resolved. The need for a third assessor was not required as no disagreement was present. Key findings were compared and grouped into overarching themes. Themes comprised factors that occurred across several papers, and these were refined and synthesised through a process of grouping and regrouping the data into meaningful categories and through whole-team discussions and agreement.

Results

The aim of the current review was to identify effective components of vulnerability assessment across LEPH, and to identify how vulnerability has been assessed across LEPH organisations in countries belonging to the Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). As identified in past research (e.g. Enang et al. Citation2019), no tools or guidelines for broad vulnerability assessment which applied across LEPH were identified, nor were specific frameworks or guidelines to inform vulnerability assessment by LEPH frontline professions. However, some context/subject specific tools were identified, and these are highlighted in the following sub-sections. The key components for effective vulnerability assessment aligned within four categories: prevention; diversion/triage; specific interventions; and training. These are now discussed in turn.

Prevention

Vulnerability assessment in the context of upstream prevention models was studied in eight of the included studies (Bomba Citation2006, Cohen Citation2016, Coulton et al. Citation2017, Davidson et al. Citation2016, Frisman et al. Citation2008, Leese and Russell Citation2017, Shaw Citation2016). Within this theme, studies discussing assessment as being key to identifying appropriate treatment/intervention were included; hence assessment in these studies is considered a prevention strategy in itself. It must be acknowledged that ensuring that the required treatments/interventions are available following assessment requires systemic change and inter-agency collaboration; assessment is not in itself an intervention.

Therefore, effective prevention in this sense requires (a) effective assessment of and (b) response to vulnerability, which involves (c) a whole system approach working across agencies. For example, the assessment and management tool prescribed by Bomba (Citation2006) focused on inter-agency prevention strategies in a public health context. This tool provided opportunities for identifying potential for increasing or continuing elder abuse by presenting several characteristics indicative of this behaviour. The importance and role of workers across health and social care agencies in promptly suspecting elder abuse was highlighted (Bomba Citation2006).

Prevention through early identification of risk profiles was considered by Cohen (Citation2016) in relation to risk of radicalisation and terrorist attack. The complexity of factors associated with vulnerability prevention were highlighted by Frisman et al. (Citation2008) in their exploration of characteristics associated with engaging in HIV/AIDS risk behaviours. The authors identified networks of demographic and behavioural characteristics, which in varying combinations, increased or decreased the likelihood of HIV/AIDS risk behaviours occurring. Identification of these networks of risk allowed for the formation of prevention interventions aimed at their mitigation. Likewise, Coulton et al. (Citation2017) advocated for early interventions to proactively identify criminal justice engaged adolescents. In both instances, early identification came from law enforcement officials working with community members, educators, mental health professionals, and faith leaders, with each disclosing information on behavioural patterns indicative of this vulnerability.

According to Davidson et al. (Citation2016), the need for early intervention arose from high incidences of mental disorder and associated mortality during custody and re-integration into the community. Thus, Court Liaison Services (CLS) aimed to intervene early in criminal justice matters by promptly identifying people with mental health disorders, and sometimes those with intellectual disability (ID), post-charge and prior to sentencing. The authors recommended the use of a mental state examination to assess risk of harm to others/self, treatment adherence, and substance abuse. Custody staff interviewed in Leese and Russell’s (Citation2017) study identified potential benefit in developing pre-release care plans for detainees, to best prevent mental health problems developing into suicidal crises post-release. Similarly, case studies presented by Shaw (Citation2016) suggest that frequent contact with the criminal justice system may be reduced through the development of care plans devised with the involvement of agencies across health and social care.

In all of the examples identified, the preventative approaches taken or suggested were not universal primary prevention strategies, but rather secondary prevention strategies targeted at early intervention with people with vulnerability assessed as being more ‘at risk’. Such an approach to vulnerability assessment can mitigate negative outcomes associated with mental health problems, improve public safety, and reduce financial expenses associated with addressing mental health related crimes.

Diversion and triage

Within the law enforcement, pre-arrest context, ‘diversion’ occurs when police officers redirect people, for example, with learning disabilities or mental health challenges to assessment and intervention/treatment services, instead of arresting them (Schucan and Shemilt Citation2019). This is expected to reduce criminal activities, promote public safety, improve access to relevant mental health services for those in need of such, and save money (Kane et al. Citation2018, Heilbrun et al. Citation2012). In the public health context, triage occurs when health and social care services identify and prioritise service delivery according to need (Stanfield Citation2015).

Diversion and triaging featured in eight studies (Bomba Citation2006, Campbell et al. Citation2017, Davidson et al. Citation2016, Citation2017, Earl et al. Citation2015, Shaw Citation2016, Strauss et al. Citation2005).

Bomba (Citation2006) argued that nurses, physicians and social workers should know when patients need additional assessment and/or when to refer them for appropriate intervention/services, and recommended use of a simple one-page tool called ‘Principles of Assessment and Management of Elder Abuse Tool’ to assess and manage elder abuse. Linking back to the previous ‘prevention’ sub-section, this is a demonstration of how assessment and subsequent treatment/intervention can and should be linked and coordinated to best support people at various stages of their care; prevention and diversion/triage (and the related assessment and treatment/intervention) do not, or should not, exist in vacuums.

Campbell et al. (Citation2017) identified a community-based intervention approach and pre-arrest diversion scheme that systematically diverted people who had committed low-level offenses to relevant mental health services. Court liaison procedures existed across regional jurisdictions in Australia, described by Davidson et al. (Citation2016, p. 908) as specialist services aiming to: ‘intervene early in the criminal justice process by identifying mentally ill individuals at the post-charge, pre-sentence stage, providing timely advice to courts and linkage with treatment providers’. The outcomes of the court liaison procedures were used to determine fitness to stand trial, state of mind at the time of committing an offence and to assess the risk of harming self or others (Davidson et al. Citation2016, Citation2017).

Earl et al. (Citation2015) reported how people with mental health challenges were directly referred by the Cornwall Criminal Justice Liaison and Diversion Service (CJLDS) to a Mental Health Professional for assessment within 48 hours. Their evaluation of a community outreach scheme reported that more than two thirds of those referred required assistance from mental health services, as opposed to the criminal justice system. Shaw (Citation2016) further emphasised need for diversion services to ensure that people with learning disabilities had appropriate access to relevant interventions.

A key issue relating to the diversion of suspected vulnerable individuals was highlighted by Bomba (Citation2006) as a need to balance practitioners’ duty of care to people with vulnerabilities with the self-determination of these individuals in deciding the extent and type of health care they wished to access. A potential solution articulated by Shaw (Citation2016) was the provision of joined-up inter-agency care planning, which presumably may present a holistic, person-centric approach, as opposed to single agency referrals.

Strauss et al.’s (Citation2005) evaluation of a Crisis Intervention Team (CIT) programme found that CIT officers were able to adequately identify psychiatric emergencies and refer individuals in need of assessment and treatment to appropriate mental health services. Regardless of the origins of diversion and triaging services, i.e. law enforcement or public health, they are relevant because they are designed to place people at the heart of service delivery.

Specific interventions

Across nine studies, vulnerability assessment related to identified elements of interventions that may be implemented at various time points (Bomba Citation2006, Herrington and Roberts Citation2012, Cohen Citation2016, Frisman et al. Citation2008, Leese and Russell Citation2017, Shaw Citation2016, Cambridge and Parkes Citation2006, Davidson et al. Citation2016, Citation2017). A number of these fall under the prevention or diversion/triaging-based interventions and have been covered in previous sections (Cohen Citation2016, Davidson et al. Citation2016, Citation2017, Frisman et al. Citation2008, Leese and Russell Citation2017, Shaw Citation2016). Only interventions that extend those discussions are addressed within this section; though this once again emphasises the need for linked approaches to prevention through to intervention, as discussed previously.

Screening-based interventions were proposed in two studies (Bomba Citation2006, Herrington and Roberts Citation2012). In presenting an assessment and management tool for suspected elder abuse, Bomba (Citation2006) provided screening questions and a list of common tell-tale signs that can be used to identify and intervene in cases of elder abuse (Bomba Citation2006). Screening for potential vulnerability was also advocated by Herrington and Roberts (Citation2012) in relation to ‘psychological vulnerability’ among suspects in police interviews. The authors concluded that screening-based interventions by police officers are a valid and reliable method for identifying elder abuse and psychological vulnerability.

Cross-agency working with vulnerable adults was promoted by Cambridge and Parkes (Citation2006) in their discussion of a training programme for health and social care workers. They suggested that interventions involving vulnerable adults worked most effectively when they were conducted across agencies. However, the authors provided a cautionary commentary on some of the challenges facing such interventions. The challenges described related to sharing confidential information across agencies, effective liaison across agencies, difficulties engaging specialist services such as GPs, psychiatrists, and psychologists, with limited management support for cross-agency cases.

Training

The need for training across LEPH professions was implicit across the studies. Ten were explicit in their recommendations for training in vulnerability assessment across LEPH professionals (Booth et al. Citation2017, Campbell et al. Citation2017, Cohen Citation2016, Eadens et al. Citation2016, Earl et al. Citation2015, Henshaw and Thomas Citation2012, Herrington and Roberts Citation2012, Leese and Russell Citation2017, Spivak and Thomas Citation2013, Strauss et al. Citation2005). Two empirical studies and one literature review explored the effectiveness of dedicated training for police officers called out to handle incidences involving individuals who may have a mental illness (Campbell et al. Citation2017, Earl et al. Citation2015, Strauss et al. Citation2005). The authors explored two areas: the potential benefit of additional training and the need or desire for additional training.

Potential benefits of receiving training on vulnerability assessment were reported in two literature reviews (Booth et al. Citation2017, Campbell et al. Citation2017). Booth et al. (Citation2017) found that officers in receipt of crisis intervention team (CIT) training were better at identifying mental illness. They presented evidence for the success of a variety of training interventions in increasing mental health awareness, reducing mental health stigma, and enhancing skills for dealing with mental health related issues, among non-mental health professionals. However, the evidence presented therein should be interpreted with caution due to low quality evidence throughout their included studies, demonstrated by transparency issues and inadequate reporting across almost all their included studies. Campbell et al.’s (Citation2017) literature review suggested that CIT trained officers were more likely to respond to mental health crises in a more humane way, compared with non-recipients of this training. This finding was echoed in two empirical studies (Strauss et al. Citation2005, Earl et al. Citation2015). As stated in the Diversion and Triage section earlier, CIT (Strauss et al. Citation2005) and CJLDS (Earl et al. Citation2015) trained officers were found to be competent in identifying and referring individuals in need of mental health support to the appropriate services.

Considering the need for additional training, Spivak and Thomas (Citation2013) found that independent third persons commonly request additional training in the procedural elements of their role, such as information on legal and police protocols, and methods for identifying Intellectual Disability (ID). The need for additional training relating to ID, as well as lack of current training provision among police officers, was highlighted by Eadens et al. (Citation2016). According to the authors, 84% of officers surveyed had received minimal or no training for identifying ID. Furthermore, only a third felt that they could identify ID based on the person’s cognitive characteristics, and less than half felt that they could identify ID through behavioural, physical, or speech characteristics. Similarly, Geijsen et al. (Citation2018) reported that three quarters of the police officers interviewed had received no specialised training for interviewing people who may be vulnerable.

Three additional studies identified the need for training to implement recommendations (Cohen Citation2016, Herrington and Roberts Citation2012, Leese and Russell Citation2017). Leese and Russell (Citation2017) recommended continuous risk assessment of vulnerable people while in custody, stating that custody staff required training to do this. Likewise, Herrington and Roberts (Citation2012) recommended the provision of ‘appropriate adults’ during police interviews with vulnerable people to mitigate the risks associated with interviewing this demographic, with the proviso that these adults were appropriately trained for the role. Cohen (Citation2016) highlighted the need for community-based professionals in law enforcement and mental health to assess and recognise risk of violent behaviour. This again suggests the need for additional training to improve competencies within these professional groups in proactively identifying potential violent behaviour. Likewise, Henshaw and Thomas (Citation2012) noted that formal specialised police training was critical because it was required for identifying and dealing with individuals with ID. The authors found that only about two thirds of their sample had received sufficient training on ID. This strongly correlated with harbouring negative attitudes towards training, implying that poor awareness of the need for specialised training on ID by police officers may result in negative perceptions about and relevance of training.

Discussion

The current review sought to answer the question: How has vulnerability been assessed across LEPH organisations in countries belonging to the OECD? Through answering this question, the review aimed to identify effective components of vulnerability assessment across published, peer-reviewed LEPH literature. No tools or guidelines specifically assessing vulnerability in a broad sense were identified. As such, the findings of the review focused on what the effective components of vulnerability assessment across LEPH were, and these were organised into four themes: prevention; diversion and triage; specific interventions; and training.

The findings of the current review align with some of the well-evidenced and widely used existing ideas around primary, secondary and tertiary prevention used in different criminological and LEPH contexts (e.g. Christmas et al. Citation2018, Wood and Watson Citation2017). The prevention and intervention stages identified in our findings map quite well to notions of primary and tertiary prevention. However, in the case of vulnerability assessment there are some important, if subtle, distinctions from Brantingham and Faust’s (Citation1976) model. Brantingham and Faust’s (Citation1976) model of prevention distinguishes between targeting of prevention at three levels: primary, secondary and tertiary. In our findings, prevention aligned to a pre-intervention stage, and thus could involve either primary or more frequently, secondary prevention. Diversion (from criminal justice system involvement), or triage (to health and social care), is not quite the same as secondary prevention, where preventive interventions are targeted towards those people or places which are deemed to be at risk. However, there are some similarities in that it identifies and seeks to mitigate problems before they escalate to the point where they involve a full-blown response from the system.

A key finding applicable across these themes was the significant overlap in the messages and approaches needed at each of these stages. For instance, appropriate assessment can be viewed as a preventative strategy in and of itself, as a mechanism to diversion/triage, or even as a form of intervention; and for optimal use, training ought to be integrated into the effective use of assessment, ideally at a cross-profession level. This more holistic view of a person’s journey and needs within the LEPH system is important, as one profession and one stage cannot meet the needs entirely; it demonstrates the complexity of the system and emphasises the need for joined-up approaches and systems.

Another key finding that was present across the four key themes was the need for collaborative working practices and systems-level changes to best support both the professions and the people who encounter the professions, in reaching the best possible outcomes. This finding is one which is echoed from past work in the LEPH and vulnerabilities field, with numerous calls for the incorporation of shared values, shared definitions, training, policies and approaches to be integrated across LEPH professions (e.g. Bartkowiak-Théron and Asquith Citation2017, Cristofoli et al. Citation2017, Dougall et al. Citation2020a, Citation2020b, Enang et al. Citation2019, HM Government Citation2014, Kesic et al. Citation2019, Murray et al. Citation2021). The current research adds to these past calls in emphasising the need for cross-profession approaches to facilitate vulnerability assessment, specifically, at each of the four stages identified in the key themes but emphasises the ongoing need and potential benefit of cross-profession working in other complex areas of LEPH.

To consider each of the four themes in more depth, each is now discussed in turn, with key aspects highlighted. A summary of the strengths and weaknesses of the review then follows, culminating with concluding remarks and recommendations.

Key messages within the identified themes

Prevention

As is well discussed in the health and criminal justice literatures, prevention is central to reducing crime (e.g. Fennelly and Perry Citation2018, Weisburd et al. Citation2017) and improving health outcomes (Calear et al. Citation2018, Cameron and Schneider Citation2018). While the literature identified in our review discussed the need for preventative strategies, there was some blurring across papers regarding definitions of prevention, with some studies conflating prevention with early intervention. While both are of direct relevance to the aims of the current review, this blurring of operational definitions and conceptualisation is problematic for developing strategic vulnerability assessment planning across LEPH. Future research must be clear about whether the focus is on primary prevention, or whether it is early intervention, i.e. secondary prevention being studied.

Prevention and early intervention (or secondary prevention) via early identification of vulnerability is critical to vulnerability assessment because: (a) individuals and the general public may be spared from harm, (b) negative health or criminal justice outcomes may be mitigated, and/or (c) arrests and recidivism may be reduced (Shaw Citation2016). Similarly, resources originally allocated for expensive interventions may be saved. As the police operate as the gateway to the criminal justice system, early identification of vulnerability often falls on these first responders.

It may be recommended that key elements in the prevention of vulnerability include the early identification of individuals at risk of vulnerability (Leese and Russell Citation2017, Shaw Citation2016) via partnership working between LEPH professions (Cohen Citation2016) or through liaison services such as those used in some court systems (Davidson et al. Citation2016). In these scenarios, formal risk assessment tools may be adopted to identify potentially vulnerable individuals.

Diversion and triage

Diversion and triage are an established practice across LEPH that can lead to fewer arrests (Schucan and Shemilt Citation2019), a reduction in criminal behaviour, and improved access to healthcare services (Heilbrun et al. Citation2012, Kane et al. Citation2018). For diversion and triage to succeed, there must first be an inter-professional understanding of whose role is most appropriate at each stage of contact (Bartkowiak-Théron and Asquith Citation2017, Enang et al. Citation2019). Inter-professional working in vulnerability assessment needs to allow the most appropriate service and/or intervention to be applied at the appropriate time, and be adapted to local context. As a unified starting point, identifying individuals who may be vulnerable is the first step in the diversion/triage process.

As discussed earlier, successful diversion and triage can involve: the inclusion of CIT’s to identify people requiring physical health care (Bomba Citation2006, Booth et al. Citation2017, Strauss et al. Citation2005); and the direct referral of people with mental health or other vulnerabilities (e.g. drug use) via the criminal justice liaison and diversion services for fast assessment and connection to suitable services (Booth et al. Citation2017, Bomba Citation2006, Davidson et al. Citation2016, Citation2017, Earl et al Citation2015, Leese and Russell Citation2017).

Collaborative working between carers/family members and agencies has been identified as one of the primary responsibilities of liaison and diversion professionals (Shaw Citation2016). For this to be successful, it must be a true collaborative endeavour between health, social care, and police agencies (Cambridge and Parkes Citation2006), with close liaison between stakeholders who are knowledgeable about vulnerabilities (Herrington and Roberts Citation2012), and, ideally, a dedicated liaison coordinator with responsibility across the different services (Campbell et al. Citation2017).

Intervention

While there were some specific intervention models identified, the authors acknowledge and stress that these are not the only interventions available, nor should they be considered ‘preferred’ interventions. This review established that interventions could include crisis intervention techniques such as psychiatric/mental health assessment, recursive partitioning, and/or criminal justice system focused interventions or assessments.

Once again, prioritising holistic and collaborative ways to detect, assess, and intervene in situations where individuals may exhibit vulnerabilities supports a preventative, collaborative approach to early intervention (Cohen Citation2016). Community-based interventions involving collaboration between stakeholders to deploy models of mental health diversion are promising (Campbell et al. Citation2017). These are designed to address and minimise criminalisation of mentally ill people in the community and/or the use of a Crisis Intervention Team (CIT) (Henshaw and Thomas Citation2012), with delegated uniformed police officers specially trained to work with people in crisis. These are promising inter-professional LEPH interventions for supporting people with vulnerabilities.

Training

Training of police and other public sector professionals cannot be ignored because police alone cannot handle mental health issues; a multi-agency approach is required to effectively tackle vulnerability and other related mental health issues (Booth et al. Citation2017). Therefore, more research is required to develop and assess training for police officers, health professionals, and public sector workers in LEPH to improve knowledge and reduce uncertainty (Bomba Citation2006, Booth et al. Citation2017, Eadens et al. Citation2016). This is also increasingly important in the context of the United States, where the use of police force has been identified as problematic in relation to people with mental health issues (Baker and Pillinger Citation2020, Wood and Watson Citation2017).

From a training intervention perspective, broad-based community partnership working is required to develop programs that meet the local needs of people with mental illness and law enforcement agents (Campbell et al. Citation2017). The 24 hours/seven days a week availability of community-based and inpatient mental health care, and a coordinating person or agency to effectively liaise between stakeholders are critical enhancements to CIT training (Campbell et al. Citation2017). It is essential that health and social support services are appropriately resourced to be available beyond nine-to-five on weekdays.

Strengths and limitations of the review

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic literature review conducted to identify and synthesise effective components for vulnerability assessment across LEPH from the peer-reviewed literature. A systematic review approach was considered appropriate for this because it encourages methodical rigour and the use of transparent and processes (Liberati et al. Citation2009, Tranfield et al. Citation2003, Cook et al. Citation1997). The search and eligibility criteria were developed by the research team and a highly experienced university librarian to mitigate against article selection bias. To reduce the potential for bias further, four reviewers were involved in the data extraction, screening, appraisal, synthesis, and reporting processes. This aligns with Moher et al.’s (Citation2015) PRISMA-P checklist.

The review identified 18 peer-reviewed publications relevant to vulnerability assessment across LEPH. Of these, only one was a clear combined LEPH focus, with 15 being focused on law enforcement. While this may indicate some skew in the foci of the included papers, the overarching themes from the data synthesis apply across both LE and PH contexts.

The focus on articles published in English means that some relevant studies published in other languages may have been excluded. While this poses a limitation, it does not necessarily impact negatively on the overarching research findings and their generalisability. As the aim was to identify effective components of vulnerability assessment across LEPH, the data synthesised across the identified studies was broad and inclusive.

The current systematic review fills an important gap in the literature on vulnerability assessment in LEPH and is significant at a time when a public health approach to policing and police-led public health approaches are being actively pursued to tackle various health and social problems. Inevitably, in taking an approach to identify elements of effective vulnerability assessment reported in peer-reviewed scholarly articles only, some relevant material on vulnerability assessment across LEPH was excluded.

Subsequent work building on this review of effective vulnerability assessment practices needs to consider augmentation with ‘grey literature’, including several significant and influential contributions to the field that were not included in this review. Scrutinising the literature which we identified as important but ‘missing’ from our searches, several reasons were identified: (1) some important contributions are published as book chapters or are policy documents; (2) some of the peer-reviewed journal articles did not explicitly discuss vulnerability as aligned to our set definition for the review and the keyword searching did not identify these; (3) finally, some important articles did appear in the searches and within the title and abstracts, but the key foci of these papers were not primarily on vulnerability assessment, but on related aspects such as CITs or mental health assessment (Watson et al Citation2008a, Citation2008b, Wood and Beierschmitt Citation2014, Keay and Kirby Citation2018, Asquith et al Citation2017).

Future work in this area should consider using a broader definition of vulnerability than the one chosen in the current review, an expansion of the keyword searches to be broader than those we included (see Appendices 1 and 2), or an expansion of the search strategy to incorporate the grey literature as crucial to understanding the work as a whole. This current review therefore provides narrower perspectives from published journal articles only and does not represent all the available evidence. This is perhaps a salient lesson to all who work between academia and practice, to understand that good examples of high-quality practice-based evidence may be held in grey literature and knowing where to look is fundamental to successful endeavours summarising evidence. This is also a demonstration of the complexity of bringing together literature across disciplines on a complex and poorly defined construct and is further evidence of the need for ongoing cross-disciplinary work in this area.

Concluding remarks – towards the operationalisation of evidence-informed vulnerability assessment across LEPH

As our focus has been on vulnerability assessment much of the preventive activity in the studies reviewed was understandably at a secondary level, on the ‘at risk’. However, ideally investment would be in upstream primary prevention efforts, ensuring adequate social security, education, health and other social services, and on mitigating the impact of social strains such as poverty and inequality on health and other vulnerabilities. Nonetheless, we also highlight the importance of core aspects of effective vulnerability assessment in LEPH, particularly in securing diversion from the criminal justice system, and targeting more intensive, supportive and non-stigmatising interventions where required.

As shown, vulnerability assessment across LEPH and the systems that professionals work within are complex. It is therefore not possible without further evidence and research to make specific recommendations, such as the use of a tool or measure, around vulnerability assessment. Instead, what the evidence identified suggests is that a whole systems approach with collaborative leadership is required, with a core focus on prevention and upstream interventions, using more holistic, person-centred assessment as a key component of this.

Effective vulnerability assessment ought to be person-centred, seeking to prevent where possible, and effectively diverting/triaging when prevention is not possible. Collaborative approaches across professions ought to be established where possible to reduce barriers to effective processes and outcomes, ideally with a long-term goal of a systems-level change to facilitate this. Finally, to help achieve the ambition of better shared understandings and collaborative approaches, appropriate training across all stages, with training being used across the spectrum of knowledge development, and indeed as an intervention itself is essential. Training should align across professional groups and be supported by people with lived experience of the LEPH nexus. Interdisciplinary learning, knowledge sharing and exchange sit at the heart of the process to reduce fragmentation in the vulnerability assessment process and journey. This is no small task, but one which is achievable with investment in systems and processes and with the support of senior and collaborative leadership across LEPH.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the support provided by Sheena Moffat, (Subject Librarian, School of Health and Social Care, Edinburgh Napier University), and a LEPH expert advisory group.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interests was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Asquith, N.L., et al., 2017. Policing encounters with vulnerability. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Baker, D., and Pillinger, C., 2020. If you call 911 they are going to kill me’: families’ experiences of mental health and deaths after police contact in the United States. Policing and society, 30 (6), 674–687.

- Bartkowiak-Théron, I., and Asquith, N., 2017. Conceptual divides and practice synergies in law enforcement and public health: some lessons from policing vulnerability in Australia. Policing and society, 27 (3), 276–288.

- Bell, A. 2019. Policing and mental health. Paper presented at the Inaugural LEPH Mental Health Summit in Scotland. Edinburgh Napier University, Edinburgh.

- Bomba, P.A., 2006. Use of a single page elder abuse assessment and management tool: a practical clinician’s approach to identifying elder mistreatment. Journal of gerontological social work, 46 (3-4), 103–122.

- Booth, A., et al., 2017. Mental health training programmes for non-mental health trained professionals coming into contact with people with mental ill health: a systematic review of effectiveness. BMC psychiatry, 17 (1), 196.

- Bows, H., 2018. Sexual violence against older people: a review of the empirical literature. Trauma, violence, & abuse, 19 (5), 567–583.

- Boyce, J., et al. 2015. Mental health and contact with the police. Juristat. Available from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/pub/85-002-x/2015001/article/14176-eng.pdf?st=ce4HSewF.

- Brantingham, P.J., and Faust, F.L., 1976. A conceptual model of crime prevention. Crime and delinquency, 22 (3), 284–296.

- Brown, K., 2017. Vulnerability and young people: care and social control in policy and practice. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Burris, S., and Burrows, D., 2009. Drug policing, harm reduction and health: directions for advocacy. International journal of drug policy, 20 (4), 293–295.

- Calear, A.L., et al., 2018. School-based prevention and early intervention programmes for depression. Handbook of school based mental health promotion, 279–297.

- Cambridge, P., and Parkes, T., 2006. The Management and practice of joint adult protection investigations between health and social services: issues arising from a training intervention. Social work education, 25 (8), 824–837.

- Cameron, K.A., and Schneider, E.C., 2018. Benefits of evidence-based health promotion/disease prevention programmes for older adults and community agencies. Innovation on aging, 2 (1), 846.

- Campbell, J., et al., 2017. Building on mental health training for law enforcement: strengthening community partnerships. International journal of prisoner health, 13 (3/4), 207–212.

- Centre for Reviews and Dissemination: Systematic Reviews, 2009. CRD’s guidance for undertaking reviews in health care. New York: Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, University of York.

- Christmas, H., et al. 2018. Policing and health collaboration in England and Wales. Landscape review. Public Health England. 47. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/679391/Policing_Landscape_Review.pdf.

- Christmas, H., and Srivastava, J. 2019. Public health approaches in policing. A discussion paper. [Internet]. Public Health England and College of Policing. Available from: https://cleph.com.au/application/files/7615/5917/9047/Public_Health_Approaches_in_Policing_2019_England.pdf.

- Cohen, J.D., 2016. The next generation of government CVE strategies at home: expanding opportunities for intervention. The annals of the american academy of political and social science, 668 (1), 118–128.

- Cook, D. J., et al., 1997. The relation between systematic reviews and practice guidelines. Annals of internal medicine, 127 (3), 210–216.

- Coulton, S., et al., 2017. Pragmatic randomised controlled trial to evaluate the effectiveness and cost effectiveness of a multi-component intervention to reduce substance use and risk-taking behaviour in adolescents involved in the criminal justice system: a trial protocol (RISKIT-CJS). BMC public health, 17 (1), 246.

- Cristofoli, D., et al., 2017. Collaborative administration: the management of successful networks. Public management review, 19 (3), 275.

- Davidson, F., et al., 2016. A critical review of mental health court liaison services in Australia: a first national survey. Psychiatry, psychology and law, 23 (6), 908–921.

- Davidson, F., et al., 2017. Mental health and criminal charges: variation in diversion pathways in Australia. Psychiatry, psychology and law, 24 (6), 888–898.

- Department for Communities and Local Government. 2015. Addressing complex needs: improving services for vulnerable homeless people. Department for Communities and Local Government.

- Dougall, N., et al., 2014. Deaths by suicide and their relationship with general and psychiatric hospital discharge: 30-year record linkage study. The British journal of psychiatry, 204 (4), 267–273. doi:https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.112.122374.

- Dougall, N., et al. 2020a. Mental health, distress and the emergency department national summit communique. Law Enforcement and Mental Health Special Interest Group (LEMH SIG) GLEPHA.

- Dougall, N., et al., 2020b. Childhood adversity, mental health and suicide (CHASE): a protocol for a longitudinal case-control linked data study. International journal of population data science, 5 (1), Available from: https://ijpds.org/article/view/1338.

- Duncan, E.A.S., et al., 2019. Epidemiology of emergency ambulance service calls related to mental health problems and self-harm: a national record linkage study. Scandinavian Journal of trauma, resuscitation and emergence medicine, 27 (1), 34. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s13049-019-0611-9.

- Duncan, E.A.S., and Murray, J., 2012. The barriers and facilitators to routine outcome measurement by allied health professionals in practice: a systematic review. BMC health services research, 12, 96.

- Durham Regional Police Services (DRPS). 2017. Annual report: 2017. Available from: https://members.drps.ca/annual_report/2017/Annual_report_2017_WEB.pdf.

- Eadens, et al., 2016. Police officer perspectives on intellectual disability. Policing: an international journal of police strategies & management, 39 (1), 222–235.

- Earl, F., et al., 2015. Neighbourhood outreach: a novel approach to liaison and diversion. The journal of forensic psychiatry & psychology, 26 (5), 573–585.

- Enang, I., et al., 2019. Defining and assessing vulnerability within law enforcement and public health organisations: a scoping review. Health & justice, 7, 2.

- Fennelly, L.J., and Perry, M.A., 2018. Crime and effective community crime prevention strategies. In: CPTED and traditional security countermeasures150 things you should know. CRC Press, p. 364–366.

- Frisman, L., et al., 2008. Applying classification and regression tree analysis to identify prisoners with high HIV risk behaviors. Journal of pychoactive drugs, 40 (4), 447–458.

- Geijsen, K., et al., 2018. Identifying psychological vulnerabilities: studies on police suspects’ mental health issues and police officers’ views. Cogent psychology, 5 (1), 1462133.

- Graham, M. 2017. Justice committee demand-led policing: service of first and last resort. Written submission to Scottish Parliament Justice Committee from Police Scotland. Available from: http://www.parliament.scot/S5_JusticeCommittee/Inquiries/DLP_Police_Scotland.pdf.

- Heilbrun, K., et al., 2012. Community-based alternatives for justice-involved individuals with severe mental illness: review of the relevant research. Criminal justice and behavior, 39 (4), 351–419.

- Henshaw, M., and Thomas, S., 2012. Police encounters with people with intellectual disability: prevalence, characteristics and challenges. Journal of intellectual disability research, 56 (6), 620–631.

- Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire & Rescue Services. 2018. Policing and mental health: picking up the pieces. Available from: https://www.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/hmicfrs/wp-content/uploads/policing-and-mental-health-picking-up-the-pieces.pdf.

- Herrington, V., and Roberts, K., 2012. Addressing psychological vulnerability in the police suspect interview. Policing: a journal of policy and practice, 6 (2), 177–186.

- HM Government and MIND. 2014. Mental health crisis care concordat [Internet]. Available from: https://www.crisiscareconcordat.org.uk/.

- Iacono, T., 2014. What it means to have complex communication needs. Research and practice in intellectual and developmental disabilities, 1 (1), 82–85. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/23297018.2014.908814.

- Jardine, M., et al., 2012. Harm reduction and law enforcement in Vietnam: influences on street policing. Harm reduction journal, 9 (1), 27.

- Kane, E., et al., 2018. Effectiveness of current policing-related mental health interventions: a systematic review. Criminal behaviour and mental health, 28 (2), 108–119.

- Keay, S., and Kirby, S., 2018. Defining vulnerability: from the conceptual to the operational. Policing: a journal of policy and practice, 12 (4), 428–438.

- Kelly, J., et al. 2014. Peer review in scientific publications: benefits, critiques, and a survival guide. Ejifcc, 25 (3), 227–243.

- Keown, P., 2013. Place of safety orders in England: changes in use and outcome: 1984/5 to 2010/11. The psychiatrist, 37, 89–93.

- Kesic, D., et al. 2019. Police management of mental health crises in the community. Law Enforcement and Mental Health Special Interest Group Guideline. 31. Available from: https://gleapha.wildapricot.org/resources/Documents/LEMH%20SIG%20Guideline_September%202019.pdf.

- Kolehmainen, N., et al., 2010. Community professionals’ management of client care: a mixed-methods systematic review. Journal of health services research and policy, 15 (1), 47–55.

- Leese, M., and Russell, S., 2017. Mental health, vulnerability and risk in police custody. The journal of adult protection, 19 (5), 274–283.

- Liberati, A., et al., 2009. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. Bmj, 339, b2700–b2700. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2700.

- Moher, D., et al., 2009. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. British medical journal, 339, b2535.

- Moher, D., 2015. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Systematic reviews, 4 (1), 148–160. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-4-1.

- Murray, J., et al., 2018. Law enforcement and public health: setting the agenda for Scotland. Scottish institute for policing research annual review, 2017/2018, 33–34.

- Murray, J., et al., 2021. Co-creation of five key research priorities across law enforcement and public health: a methodological example and outcomes. Journal of psychiatric and mental health nursing, 28 (1), 3–15.

- The National Archives, 2007. Adult support and protection (Scotland) Act 2007. Retrieved from https://www.legislation.gov.uk/asp/2007/10/contents.

- National Police Chief’s Council. 2018. Policing, health and social care consensus: working together to protect and prevent harm to vulnerable people. Available from: https://www.npcc.police.uk/Publication/NEW%20Policing%20Health%20and%20Social%20Care%20consensus%202018.pdf.

- Policing. 2026. A healthier Scotland – police Scotland [Internet]. Available from: https://www.scotland.police.uk/whats-happening/featured-articles/policing-2026-a-healthier-scotland.

- Popay, J., et al., 2006. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews: final report. Swindon: ESRC Methods Programme.

- Punch, M., 1979. The secret social service. In: S. Holdaway, ed. The British police.

- Schucan Bird, K., and Shemilt, I., 2019. The crime, mental health, and economic impacts of prearrest diversion of people with mental health problems: a systematic review. Criminal behaviour and mental health, 29 (3), 142–156.

- Scottish Government, 2017. Mental health strategy 2017–2027. Edinburgh: The Scottish Government. Available from: https://www.gov.scot/publications/mental-health-strategy-2017-2027/pages/5/.

- The Scottish Public Health Observatory. 2019. Suicide key points. Available from: https://www.scotpho.org.uk/health-wellbeing-and-disease/suicide/key-points.

- Shaw, V.L., 2016. Liaison and diversion services: embedding the role of learning disability nurses. Journal of intellectual disabilities and offending behaviour, 7 (2), 56–65.

- Sondhi, A., and Williams, E., 2018. Health needs and co-morbidity among detainees in contact with healthcare professionals within police custody across the London metropolitan police service area. Journal of forensic and legal medicine, 57, 96–100.

- Spivak, B.L., and Thomas, S.D., 2013. Police contact with people with an intellectual disability: the independent third person perspective. Journal of intellectual disability research, 57 (7), 635–646.

- Stanfield, L.M., 2015. Clinical decision making in triage: an integrative review. Journal of emergency nursing, 41 (5), 396–403.

- Strauss, G., et al., 2005. Psychiatric disposition of patients brought in by crisis intervention team police officers. Community mental health journal, 41 (2), 223–228.

- Tranfield, D., et al., 2003. Towards a methodology for developing Evidence-Informed management knowledge by means of systematic review. British journal of management, 14 (3), 207–222. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/bjom.2003.14.issue-3.

- van Dijk, A., et al., 2019. Law enforcement and public health: recognition and enhancement of joined-up solutions. The lancet, 393 (10168), 287–294.

- Watson, A.C., et al., 2008a. Improving police response to persons with mental illness: a multi-level conceptualization of CIT. International journal of law and psychiatry, 31, 359–368.

- Watson, A.C., et al., 2008b. Defying negative expectations: dimensions of fair and respectful treatment by police officers as perceived by people with mental illness. Administration and policy in mental health, 35, 449–457.

- Weisburd, D., et al., 2017. What works in crime prevention and rehabilitation: an assessment of systematic reviews. Criminology and public policy, 16 (2), 415–449.

- Whitehurst, T., 2007. Liberating silent voices? perspectives of children with profound & complex learning needs on inclusion. British journal of learning disabilities, 35 (1), 55–61. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/bld.2007.35.issue-1.

- Wood, J.D., and Beierschmitt, L., 2014. Beyond police crisis intervention: moving “upstream” to manage cases and places of behavioural health vulnerability. International journal of law and psychiatry, 37 (5), 439–447. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlp.2014.02.016.

- Wood, J.D., and Watson, A.C., 2017. Improving police interventions during mental health-related encounters: past, present and future. Policing & society, 27, 289–299. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10439463.2016.1219734.

- Woolnough, P., et al., 2019. Distinguishing suicides of people reported missing from those not reported missing: retrospective Scottish cohort study. BJPsych open, 5 (1), E16.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategy used in databases ‘criminology collection’ and ‘sociology collection’

Six different search strings (S1, S2, S3, S4, S5, and S6) were used to identify relevant articles from the Criminology and Sociology databases. S1 yielded 235,824 articles related to law enforcement and its synonyms. S2 yielded 275,941 articles associated with public health, mental health, social inequality, and their synonyms. S3 yielded 217,147 articles discussing vulnerability, and its synonyms including terms that might indicate vulnerability like poor access to relevant support. S4 yielded 949,385 articles on risk and assessment. S5 yielded 389,080 articles about training, collaboration, triaging, communication, and their synonyms. In combining all five search strings, S6 retrieved 61 articles that specifically discussed vulnerability assessment across law enforcement and public health organisations.

Appendix 2. Search strategy used in simultaneous searches of databases ‘CINAHL’, ‘MEDLINE’, and ‘PsycINFO’

Six different search strings (S1, S2, S3, S4, S5, and S6) were used to identify relevant articles from the CINAHL, MEDLINE, and PsycINFO databases. Since MEDLINE (PubMed) automatically indexes using MeSH subject headings, the latter was not included to avoid duplication. S1 yielded 63,072 articles related to law enforcement and its synonyms. S2 yielded 2,051,387 articles associated with public health, mental health, social inequality and their synonyms. S3 yielded 826,848 articles discussing vulnerability, and its synonyms including terms that might indicate vulnerability like poor access to relevant support. S4 yielded 1,377,723 articles on risk and assessment. S5 yielded 1,989,843 articles about training, collaboration, triaging, communication, and their synonyms. In combining all 5 search strings, S6 retrieved 21 articles that specifically discussed vulnerability assessment across law enforcement and public health organisations.