ABSTRACT

The use of force is arguably the defining feature of police. Yet this power is often controversial: a key node in the contest and debate that almost always swirls around police, with the question of race never far from such contestation. In this paper, we consider the influence of race in responses to use of force incidents among British-based samples. Using two text-based vignette experiments and one video study, our aims are threefold: (1) to explore the influence of suspect race in how people respond to police use of force; (2) to test the interaction between participant ethnicity and suspect race; and (3) to understand what attitudes and beliefs influence how people respond to police use of force. We found no effect of suspect race on how people judged police use of force. White participants were slightly more accepting of police use of force than black participants, but there was no interaction with suspect race. The strongest predictor of acceptance of police use of force was trust in police, and, controlling for other relevant predictors, racial prejudice was also a significant positive predictor of acceptance of use of force. To our knowledge this is the first study of its kind to be fielded in the UK.

Introduction

Disproportionate use of police powers on ethnic minority communities in the UK has been an ongoing issue for many years.Footnote1 People from black and other minority ethnic groups are overrepresented in the UK criminal justice system at every level, from stop and search, to arrests, to imprisonment (Police Foundation Citation2020a). Racial disproportionality is also present in police use of force statistics: black individuals in England and Wales are five times more likely to have force used on them by police than white individuals (e.g. handcuffing, use of Taser, firearms; Home Office Citation2020).Footnote2 Although the disproportionate use of police powers is not a new phenomenon (Bowling and Philips Citation2002), the killing of black American George Floyd by a white police officer in the US on 25 May 2020 once again brought police, criminal justice, and societal racism into sharp focus (Safi Citation2020). In the UK, following George Floyd’s murder, protests were held around the country in support of renewed protests in the US (and around the world) and the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement, and to highlight continuing issues with racism in the UK.Footnote3

Despite the ongoing and historic patterns of disproportionate policing in the UK, significant challenges to police conduct have rarely been forthcoming, and thus far have not led to fundamental change (police activity seems to be just as disproportionate now as it was ten, twenty or even thirty years ago). One possible explanation for this may be political inertia or resistance founded in a willingness among the white majority to ignore, downplay or even justify disproportionate policing, whether this be due to implicit bias and stereotyping (Glaser Citation2015) or simply the urge to deny inconvenient facts (Cohen Citation2001) and retreat into the comforting illusion that ‘race no longer matters’ (Bonilla-Silva Citation2006). Naturally, we might also suppose the presence of racial ideologies that justify disproportionate policing on the basis that it helps to maintain, or seems to validate, existing racial hierarchies; those that rest, for example, on variation in the vices and virtues ascribed to different racialised groups (Burke Citation2017, Omi and Winant Citation2018).

A substantial body of academic literature, mostly from the US, has documented a so-called ‘racial perception’ gap in how incidents of use of force are interpreted (e.g. Johnson and Kuhns Citation2009, Peffley and Hurwitz Citation2010, Jefferis et al. Citation2011, Boudreau et al. Citation2019, Strickler and Lawson Citation2020). Here, white individuals tend to assess police use of force more positively than non-white individuals, and black individuals tend to be more likely to perceive a racially unequal application of police use of force. A distinct but related question is whether, and how, the perceived racial identity of a suspect shapes peoples’ beliefs about the acceptability of police use of force. This line of enquiry is much less developed and forms the focus of the current paper.

In three studies, we consider the influence of race in how people respond to incidents of police use of force. Using two text-based vignette experiments and one video study, our aims are threefold: (1) to explore the influence of suspect race in how people respond to a police use of force incident; (2) to test the interaction between participant ethnicity and suspect raceFootnote4; and (3) to understand whether people’s attitudes and beliefs (namely, trust in and identification with the police, worry about crime, political ideology and racial prejudice) influence how they respond to police use of force. The paper proceeds as follows. First, we outline the history of race and policing in the UK and discuss how race might affect people’s perceptions of use of force. We then discuss the attitudes and beliefs that might influence how people process and respond to incidents of force. The general method for the three experiments is then described, before proceeding with individual study methods and results. We close by discussing the theoretical and practical implications of the findings.

Race and policing in the UK

The practices and culture of British police in relation to racialised minorities has come under intense scrutiny at various points over the last five decades, manifesting in civil unrest (Scarman Citation1981, Lewis et al. Citation2011) and the investigation of procedural injustice (Macpherson Citation1999). A robust literature has documented a pattern of unequal criminal justice outcomes in the UK, including the police use of force.Footnote5 In England and Wales, for the year ending March 2020, individuals perceived by police as ‘black or black British’ were disproportionately more likely to have force used against them, particularly firearms and less lethal weapons such as baton or Taser (Home Office Citation2020). Negative encounters with police can undermine trust and confidence in police (Jackson et al. Citation2013) and it is not surprising that a strong evidence base in the UK demonstrates that some minority communities – particularly people of black Caribbean and ‘mixed’ heritage – consistently report lower levels of confidence in and satisfaction with the police than white people (Bradford et al. Citation2017, ONS Citation2019).

Given these historic and on-going patterns of disproportionality it is something of a puzzle that more significant challenges to police conduct in this area have not been forthcoming. Why has the almost constant stream of evidence that assertive police tactics are disproportionately directed towards particular ethnic groups not generated more pressure on police to change (c.f. Loader and Mulcahy Citation2003)? Events surrounding the BLM protests of 2020 would appear to offer an exemption and an inflection point for potential change – yet, one might also note that it took an event with global reach and scale to spark widespread debate about patterns in British policing that have been consistent for 30 years, if not longer (Bowling et al. Citation2019). Indeed, combatting widespread indifference to disproportionate policing can be seen as a key aim of the BLM agenda.

As outlined above, it does not seem unreasonable to suggest that one partial answer to this question is that members of the white majority are motivated to ignore, downplay or even justify disproportionate policing, whether this is for reasons of racism, stereotyping, or the urge to deny inconvenient facts. At the very least, we might surmise that intrusive police activity – and perhaps particularly the use of force – that is highly salient for members of some minority groups is simply less so for the white majority, since the latter are on average significantly less likely to be affected by it.

The disproportionate impact of police use of force on some minority communities, coupled with findings of overt and unconscious racial bias across the UK criminal justice system (Lammy Citation2017), imply that issues of race are closely linked to how people experience police actions. Yet there is very little research, and none that we know of from a UK context, that has empirically investigated whether (and how) race influences how people respond to incidents of police use of force. In this paper, we provide the first empirical test with a British sample of whether the race of the suspect influences people’s judgements about the acceptability of police use of force.

Race and evaluations of police use of force

A substantial body of research, mostly from the US, has documented a so-called ‘racial perception’ gap in how incidents of use of force are interpreted (e.g. Johnson and Kuhns Citation2009, Peffley and Hurwitz Citation2010, Jefferis et al. Citation2011, Girgenti-Malone et al. Citation2017, Boudreau et al. Citation2019, Strickler and Lawson Citation2020). This research has shown that white people tend to have more positive perceptions of police use of force and are more likely to think force is justified, and that black people tend to be more likely to perceive a racially unequal application of police use of force.

Surprisingly less well-developed, however, and somewhat equivocal, is the research examining if and how the perceived racial identity of a suspect shapes people’s beliefs about the acceptability of police use of force, and how suspect race interacts with respondent race. In a ‘race-of-the-offender’ experimental manipulation using American participants, Johnson and Kuhns (Citation2009, p. 615) found the race of the suspect depicted in a use of force vignette predicted attitudes toward police use of force, but only for black respondents, not white: white support for police use of force was largely unrelated to the race of the offender, and they were equally likely to approve of police using force if the offender was a black teenager or a white teenager. Black respondents, on the other hand, were much less likely to approve of police use of force against a black teenager. In contrast, a more recent study by Strickler and Lawson (Citation2020) found that white respondents were less likely to view police shootings as justified when they explicitly involved a white officer and a black victim. However, the authors found the effect could be explained by self-monitoring: an urge by white respondents to provide a socially desirable response. Other studies have found no significant effect of suspect race on judgements of police use of force (Rome et al. Citation1995, Girgenti-Malone et al. Citation2017, Milani Citation2020).

Compared with the US, literature examining the race of the suspect on public evaluations of police use of force in the UK is considerably less well developed, and we are not aware of any studies that have experimentally varied the race of suspects to examine whether this affects people’s judgements of police action. This omission is striking. While it cannot be assumed that the situation in the US easily translates to the UK, given the history of British policing over the last five decades asking how people interpret police use of force applied to different ethnic groups seems, to us, an obvious question to ask.

Why might suspect race affect perceptions of police use of force?

Many scholars have located explanations for the empirical findings from the US in theories of group threat/position and racial stereotyping. Conflict theory and cognate iterations within the tradition of group threat/position (Blumer Citation1958, Blalock Citation1967) suggest that racially differentiated attitudes toward police use of force may stem, in part, from support for the police’s ability to maintain the status quo which keeps the dominant group(s) in power (Choongh Citation1998). Research has shown that racial animus, or negative racial stereotyping, resentment and antipathy, are linked to the approval of the police use of force in the US (Barkan and Cohn Citation1998, Johnson and Kuhns Citation2009, Silver and Pickett Citation2015, Strickler and Lawson Citation2020). Other scholars have highlighted different types of implicit biases or stereotypes which link ‘blackness’ with ‘criminality’ as a possible source of attitudes toward the use of force that vary according to the race of the protagonists. Effects arising from the race-crime association have been described in relation to: recall of who was armed with a deadly razor at a subway scene (Allport and Postman Citation1947); evaluations of ambiguously aggressive behaviour (Devine Citation1989); the threshold at which people perceive danger (Eberhardt et al. Citation2004); and the likelihood with which they believe a black individual is liable for a capital conviction (Eberhardt et al. Citation2004, Citation2006).

Attitudes and beliefs that may influence evaluations of police use of force

Along with implicit biases or stereotypes, there are many other factors related to individuals’ attitudes and beliefs which are likely to influence how they respond to incidents involving police use of force. Previous research has demonstrated that trust in police is an important predictor of support for police actions, decisions and directions (Tyler and Huo Citation2002, Jackson et al. Citation2013, Yesberg and Bradford Citation2019, Bradford et al. Citation2020), including the acceptance of police use of force (Gerber and Jackson Citation2017, Kyprianides et al. Citation2020). Trust in police is based on judgements of efficacy and competence, but also upon expectations that police will treat members of the police fairly and behave in appropriate ways (Trinkner et al. Citation2018). For example, Kyprianides et al. (Citation2020) found that prior perceptions of trust in the police (measured as a composite of procedural justice, police effectiveness and bounded authority) was a strong predictor of whether or not people considered the use of force acceptable. Central to this and other findings is the idea that those who are trusted command legitimacy and are enabled and empowered to act on the behalf of those they govern. To the extent people believe, in a general sense, that police are trustworthy authorities, they also tend to judge specific police decisions and activities as just and proper, as long as these actions appear constrained within certain normative bounds (see Milani Citation2020).

Alongside trust, an additional factor is identification with police as members of one’s ‘in-group’, which is closely associated with both trust and legitimacy (Tyler and Huo Citation2002, Bradford et al. Citation2014). At the most basic level, if we view police officers as being like ourselves, we are more likely to trust and hold them legitimate (Bradford et al. Citation2014). While the dynamics of this relationship are likely to be complicated – for example, does identification precede or flow from trust judgements – the concept of identification with police seems particularly pertinent given current debates about representation within the service (Davies et al. Citation2020). It also serves as a reminder that trust is relational in character, and is generated and sustained via processes of identification (Radburn et al. Citation2018).

Naturally, there are other reasons why people may support or oppose police use of force. Silver and Pickett (Citation2015) distinguish between what they term utilitarian concerns, such as fear of crime, and symbolic beliefs, such as religiosity, retributiveness and (writing in the US) beliefs about gun control and racial prejudice. Importantly, they also consider the effect of political ideology, finding that conservatives are more supportive of police use of force than moderates or liberals. Other research has similarly found that more punitive, authoritarian and conservative ideologies predict support for use of force (Gerber and Jackson Citation2017, Roché and Roux Citation2017). Milani (Citation2020) considered how political ideologies shape support for the use of force in the US and found belief in a just world and authoritarian orientations, or so-called ‘system-justifying’ belief systems, predicted support for excessive use of force.

Given this literature, in this paper we investigate whether evaluations of police use of force are predicted by: (a) trust in police (i.e. whether the police are respectful, open and accountable and operate within appropriate boundaries); (b) identification with police (i.e. believing the police are a member of one’s ingroup); (c) worry about crime; (d) political ideologies, such as just world beliefs and authoritarian attitudes; and (e) racial animus/prejudice.

The current research

We conducted two text-based vignette experiments and one video study using real-life footage of a police use of force incident to answer the following research questions:

RQ1: Does suspect race influence how people respond to a police use of force incident? [studies 1 and 2]

RQ2: Is there an interaction between participant ethnicity and suspect race in how people respond a police use of force incident? [study 2]

RQ3: Do people’s attitudes and beliefs (namely, trust in and identification with the police, worry about crime, political ideology and racial prejudice) influence how they respond to a police use of force incident? [study 3]

Due to the lack of UK-based research, we make no a priori hypotheses about how suspect race will influence people’s perceptions of police use of force, nor how suspect race will interact with participants’ own ethnic identity. However, given the lower rates of satisfaction and confidence in police among many black communities in the UK, we expect that black participants will be less accepting overall of police use of force.

Finally, in line with the previous literature discussed above, we expect people’s attitudes and beliefs will influence how they respond to police use of force. Specifically, we hypothesise that those who trust and identify with the police and are worried about crime will be more accepting of police use of force. We also hypothesise that those who hold more authoritarian political beliefs, and who have higher levels of racial prejudice, will be more accepting of police use of force.

General method

Recruitment of participants

All three studies were hosted on Qualtrics and participants – residents of London, England – were recruited via the online platform Prolific. Prolific is similar to other crowdsourcing platforms such as Mechanical Turk but has a larger, more diverse pool of UK participants. In line with Prolific recruitment protocols, participants received compensation for their time. We followed Chandler and Paolacci’s (Citation2017) advice on how to minimise participant fraud on Prolific: first, we set constraints so that participants could only take the survey once. Second, we included attention checks throughout the surveys and participants were excluded if they got more than one attention check wrong.Footnote6 There was no missing data: all participants responded to all questions.

General procedure

The research was approved by the ethical review board at University College London (13091/001 and 13091/003). The online surveys included an information and consent form at the beginning, and prior to being thanked and debriefed, participants completed demographic information (gender, age, ethnicity, country of birth).

In Studies 1 and 2, participants read a short vignette about an encounter between a police officer and a person suspected of concealing a weapon (see the supplementary appendix for all materials used in this study). In study 3, participants watched a video involving a real-life incident of police use of force. These methods are consistent with previous research into perceptions of police use of force (e.g. Peffley and Hurwitz Citation2010, Testa and Dietrich Citation2017, Mullinix et al. Citation2020). Following the vignette/video, participants were asked to make a judgement about whether or not they thought the way the police officer(s) behaved was acceptable.

Study 1: method

The first study in this paper examines whether the race of the suspect in the vignette affects people’s judgements about the acceptability of police use of force. We used race cues (names and locations) to implicitly manipulate suspect race. Although this approach is common in other fields (e.g. the labour market, see below), no research that we know of from a policing context has manipulated race in this way. Along with testing RQ1, this study therefore also acts as a pilot to test whether this type of manipulation could be a useful methodology for future research in this area.

Participants and procedure

Some 305 participants were recruited via Prolific on 14 January 2020 (see for participant characteristics). All were presented with a text-based vignette about an encounter between a white police officer and a person suspected of concealing a weapon. In the vignette, the suspect refuses to comply with the officer’s instructions to take his hands out of his pockets, and, in response, the officer strikes the suspect on the legs with a baton, disabling him long enough to apply handcuffs.Footnote7 Participants were randomly allocated to one of three suspect race conditions: white, black, or Asian.

Table 1. Study 1 participant characteristics.

Race was manipulated by priming respondents with stereotypical names (Henry Jones, Terrell Williams, Syed Ahmed) and locations (Richmond, Brixton, Whitechapel)Footnote8 to encourage them to think about the suspect along particular racial lines. Numerous studies on job discrimination have shown that manipulating applicants’ names on a curriculum vitae, holding all else constant, has strong effects on people’s hiring decisions, with applicants with ‘black-sounding’ names less likely to be hired than those with ‘white-sounding’ names (e.g. Bertrand and Mullainathan Citation2004, King et al. Citation2006; Watson et al. Citation2011, Eaton et al. Citation2019). Although it is possible that using names as a race cue could result in construct confounding (i.e. names may carry other information unrelated to race, such as socio-economic status), we chose this approach because it is less susceptible to social desirability bias.

Following the vignette, participants indicated their agreement to the following questions: ‘How justified do you think it was for the officer to strike the man with his baton?’ and ‘To what extent do you agree that the way the police officer behaved was wrong?’. Participants responded on a 5-point scale from strongly disagree to strongly agree. The second item was reverse coded so higher scores indicate a higher level of acceptability. The two items formed a scale with a high reliability coefficient (α = 0.92). We use an average of the two items in subsequent analyses.

Study 1: results

Race of suspect

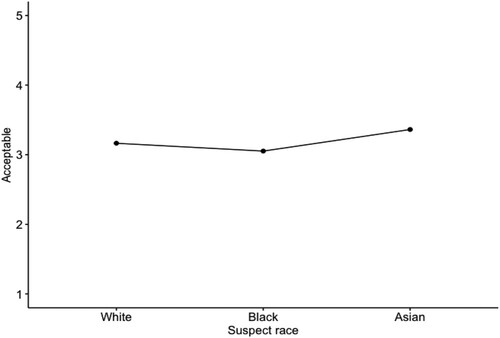

We ran a one-way ANOVA to assess the effect of suspect race on whether participants thought the police officer’s actions in the vignette were acceptable. There was no significant main effect of suspect race (F(2, 302) = 0.80, p = .452; see ). Participants thought striking the white suspect with the baton (M = 3.30, SD = 1.29) was just as acceptable as striking the black suspect (M = 3.16, SD = 1.31) or Asian suspect (M = 3.43, SD = 1.27).

Study 1: summary

The results from study 1 suggest the race of the suspect does not influence participants’ views about the acceptability of police use of force. However, at the end of the study participants were asked what race they thought the suspect in the vignette was. We found the implicit race manipulation was generally successful for the black (76% classified the suspect as black) and Asian conditions (87% classified the suspect as Asian),Footnote9 but only 29% of people in the white suspect condition classified the suspect as white. The remaining participants in the white condition either classified the suspect as black (38%) or said they did not know or gave multiple options (e.g. white or black, mixed race) (33%). Use of force incidents are proportionately more common for black individuals in the UK, so it could be that people were more easily able to imagine a situation where police used force against a black man. It could also be that implicit biases or stereotypes could explain the failure of our implicit race prime for the white condition. In other words, regardless of the reason why, many respondents seem to have assumed that someone involved in a use of force incident was black.

Study 2: method

Due to the failure of the implicit race cue for the white condition in study 1, in study 2 we conducted a follow up experiment with a more explicit race manipulation. Because of the focus in UK media, political and cultural discourse on the relationship between police and black communities (Bowling et al. Citation2019), we chose to focus specifically on the difference between white and black suspects. In study 2 we also consider the ethnicity of participants and the severity of force used.

Participants and procedure

Study 2 comprised 471 participants recruited via Prolific on 26 October 2020. Because we were interested in the interaction between suspect race and participant ethnicity, our sample was comprised of 50% (n = 235) participants who self-identified as white and 50% (n = 236) who self-identified as black (see for participant characteristics).Footnote10 Participants were randomly and evenly allocated to one of three suspect race conditions to ensure a balanced design: white, black, or not specified.

Table 2. Study 2 participant characteristics.

In study 2, we used a 3 (suspect race: black, white, unspecified) x2 (use of force: less severe vs. more severe) between-subjects design. Participants read a similar vignette to study 1 describing an encounter between a white police officer and a person suspected to be concealing a weapon where the officer used a baton to resolve the situation.

Participants were randomly allocated to one of three suspect race conditions in which the suspect was stated to be either white, black, or the race of the suspect was not specified. Participants were also randomly allocated to one of two severity of force conditions in which the officer either resolved the situation with less severe force (striking the suspect once with a baton) or more severe force (striking the suspect multiple times with a baton).

Following the vignette, participants responded to the same acceptability questions as study 1: ‘How justified do you think it was for the officer to strike the man with his baton?’ and ‘To what extent do you agree that the way the police officer behaved was wrong?’. As study 1, these items formed a scale with a high reliability coefficient (α = 0.78), and we use an average of the two items in subsequent analyses.

At the end of the study we included a validation check to determine whether people correctly recalled the race of the suspect. In the two conditions where the race of the suspect was specified, 96% (n = 303) of participants recalled the correct race. Only 14 participants recalled the wrong race or said they could not remember.Footnote11 In the condition where the race of the suspect was not specified, participants were asked to select what race they thought the suspect was. Consistent with the findings for study 1, the majority of participants (54%, n = 74) selected black, 30% (n = 49) selected white, and the remaining 24% (n = 39) selected ‘other’.

Study 2: results

We ran a 3 (race of suspect: white, black, unspecified) x 2 (severity of force: less severe, more severe) x 2 (participant ethnicity: white, black) ANOVA to assess the effects of the experimental conditions, and participant ethnicity, on judgements about whether the officer’s actions in the vignette were acceptable. Descriptive statistics for the main effects are presented in .

Table 3. Study 2 descriptive statistics for the acceptability of police action.

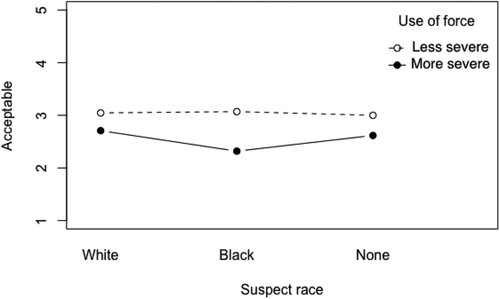

There was no significant main effect of suspect race (F(2, 465) = 1.10, p = .336). Consistent with study 1, the race of the suspect made no difference to participants’ judgements of whether or not the officer’s actions were acceptable. There was, however, a significant main effect of severity of force (F(1, 465) = 22.56, p < .001). As shown in , participants rated the less severe force scenario (M = 3.04) as more acceptable than the more severe force scenario (M = 2.54). There was no significant interaction between suspect race and use of force (F(2, 459) = 1.57, p = .208), suggesting that judgements of acceptability of the two use of force scenarios did not vary by suspect race (see ).

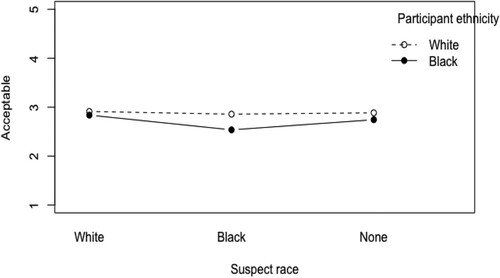

There was no significant main effect of participant ethnicity (F(2, 459) = 2.91, p = 0.089). Yet as shows, collapsed across the experimental conditions, white participants were slightly more accepting (M = 2.89) of police use of force than black participants (M = 2.70). plots the interaction between suspect race and participant ethnicity. There was no significant interaction (F(2, 459) = 0.44, p = .642), although black participants were slightly less accepting of use of force against a black suspect compared to a white suspect.

Study 2: summary

Findings from study 2 were consistent with study 1. Even when using an explicit race manipulation, there was no significant main effect of suspect race on acceptability judgements. There was, however, a significant main effect of severity of force. People were less accepting of more severe force than less severe force. Although not statistically significant at the p < .05 level, white participants were slightly more accepting of police use of force than black participants. There was no significant interaction between suspect race and participant ethnicity, suggesting that people were no more or less accepting of use of force against their own ethnic group compared to another ethnic group.

Study 3: method

Findings from studies 1 and 2 suggest that, in two British samples, suspect race does not seem to influence how people process police use of force. In study 3 we were interested in understanding whether participants’ attitudes and beliefs influence how they respond to police use of force against a black suspect.

Participants and procedure

Study 3 comprised 198 participants recruited via Prolific on 1 December 2020 (see for participant characteristics). In contrast to the text-based vignettes used in Studies 1 and 2, participants in this study were asked to view a short video of a real-life encounter between two police officers and a person suspected of committing a crime.Footnote12 Before watching the video, participants were given the following (fictional) context:

‘Officers were out on patrol in London when they noticed what they thought was a suspicious individual walking down the street. He appeared to walk faster when he noticed their presence. The man was stopped by the officers to be searched. During the search, the man began to struggle as if he was getting ready to flee, so the officers tackled him to the ground. The following video shows some of what happened next’. All participants viewed the same video, in which a black suspect was forcefully restrained by two police officers (one police officer was white and the other was Asian; see supplementary appendix).

Table 4. Study 3 participant characteristics.

Prior to viewing the video, participants were given a battery of questions to measure the key constructs of interest, including: trust and identification with police, belief in a just world, authoritarian attitudes, worry about crime, and racial animus. Following the video, participants were asked how acceptable they thought the officers’ actions were.

Measures

Confirmatory Factor Analysis in the package Mplus 7.11 was used to derive latent variables for analysis. We used a robust maximum likelihood approach (MLR) which is robust to non-normally distributed data. Unless otherwise stated, all measures were coded in such a way that higher values indicate more positive evaluations of the construct measured. Item wordings, factor loadings and model fit statistics are shown in the supplementary appendix.

Dependent variable

As studies 1 and 2, our dependent variable was acceptability of police action. Participants were asked the following questions, which were adapted from studies 1 and 2: ‘How justified do you think it was for the officers to restrain the man in this way?’ and ‘To what extent do you agree that the way the police officers behaved was wrong?’. The two items formed a scale with a high reliability coefficient (α = 0.82). Instead of using an average of these two measures, we created a latent variable for analysis (see supplementary appendix for factor loadings).

Independent variables

Two aspects of trust in police were measured (Jackson et al. Citation2013, Trinkner et al. Citation2018). First, procedural justice was measured using three items (e.g. ‘How often do you think the police in your neighbourhood treat people with respect’). Participants responded on a 5-point scale from never to very often. Second, bounded authority (i.e. the extent to which people think the police operate within appropriate boundaries) was also measured using three items (e.g. ‘When the police deal with people they almost always respect people’s rights’). Participants responded on a 5-point scale from strongly disagree to strongly agree. A latent variable – trust in police – comprising these six items was saved for analysis (α = 0.86). We label this variable ‘trust’ for the sake of simplicity, but ‘perceptions of trustworthiness’ would also be appropriate. The scale comprises respondents’ evaluations of police behaviour formed, of necessity, in the absence of full knowledge.

We also measured the extent to which people identify with the police using three items (e.g. ‘I identify with the police’; α = 0.91). Participants responded on a 5-point agree/disagree scale and a latent variable identification with police was derived (Radburn et al. Citation2018).

Three latent variables were derived which captured instrumental concerns and participants’ political ideologies. First, we measured the extent to which participants were worried about crime (Yesberg and Bradford Citation2019). We asked participants how much they were worried about (1) crime and (2) anti-social behaviour in their local area (α = 0.87). Participants responded on a 5-point scale from not worried at all to very worried.

Second, we measured belief in a just world (Dalbert et al. Citation1987) using five items (e.g. ‘I am confident that justice always prevails over injustice’). Participants responded on a 5-point agree/disagree scale. A latent variable comprising these five items was derived (α = 0.78). Lastly, we measured authoritarian attitudes (Heath et al. Citation1994) using two items: ‘people who break the law should be given stiffer sentences’ and ‘schools should teach children to obey authority’. Participants responded on a 5-point agree/disagree scale. Again, a latent variable comprising these two items was saved (α = 0.69).

Lastly, racial animus was captured with a binary variable representing whether participants would describe themselves as prejudiced against people of other races (1 = very or a little prejudiced, 0 = not prejudiced at all).

Control variables

Alongside our main predictor variables, we controlled for participant demographics (gender, age, ethnicity and country of birth), along with contact with police and prior victimisation. We captured both positive and negative contact with police and victimisation with binary variables representing whether the participant had contact with the police (which they were either satisfied or dissatisfied with), or had been a victim of crime, in the preceding 12 months.

Study 3: results

presents pairwise correlations between acceptance of police use of force and the latent variables used in analysis. As the table shows, acceptance of police use of force was most strongly correlated with trust and identification with police.

Table 5. Study 3 pairwise correlations.

We next used a series of linear regression models to explore variation in acceptance of police use of force. Model 1 included our control variables. As shows, compared to white people, and consistent with study 2, people belonging to black or mixed/other ethnic groups were significantly less accepting of police use of force. Second, younger people (aged 18–24 years) were significantly less accepting than older people. Third, people who had recent positive contact with police were significantly more accepting of police use of force compared to people who had no contact. There was no effect of negative police contact on acceptance.

Table 6. Study 3 standardised regression coefficients.

Model 2 added instrumental concerns, political beliefs and racial animus. We found that people who held more authoritarian attitudes (i.e. who thought sentences should be longer and that schools should teach children to obey authority) were significantly more accepting of police use of force. Second, we found those who reported some level of prejudice against people of other races were significantly more accepting of police use of force, compared to people who stated they were ‘not prejudiced at all’. Worry about crime and belief in a just world were not associated with acceptance of police use of force. When these variables were added to the model, most of the demographic and experiential predictors remained significant.

Lastly, Model 3 added trust and identification with police. We found that trust was a strong and significant predictor of acceptance of police use of force. In other words, regardless of people’s demographic characteristics, their experiences of policing and crime, or their attitudes and beliefs, people who trust the police to behave in a fair and just manner, and within appropriate boundaries, were more accepting of the use of force displayed in the video. Trust in police had the largest effect size in the model. And, when trust was added to the model, the coefficient for authoritarian attitudes weakened and was rendered non-significant, suggesting that the effect of authoritarian attitudes may be mediated by trust.Footnote13

Study 3: summary

Study 3 results showed that the strongest predictor of acceptance of police use of force is trust in the police. Also, controlling for other relevant predictors, racial animus and belonging to a mixed/other ethnic group were significant predictors.

General discussion

In this paper, we presented findings from two text-based vignette experiments testing the influence of suspect race on perceptions of police use of force. We also presented findings from a study using real-life video footage to explore the effect of prior attitudes and beliefs on how people react to police use of force. Both methods are consistent with previous research into perceptions of police use of force (e.g. Peffley and Hurwitz; Testa and Dietrich Citation2017, Mullinix et al. Citation2020). In studies 1 and 2 we found, first and foremost, that the race of the suspect did not influence how people responded to incidents of police use of force [RQ1]. Respondents were equally accepting (or unaccepting) of police use of force across the different suspect race conditions. This finding is consistent with some prior research from the US (Rome et al. Citation1995, Girgenti-Malone et al. Citation2017, Milani Citation2020). However, research from the US has shown that respondent race is an important factor to consider. Johnson and Kuhns’ (Citation2009) study, for example, found that black respondents were much less likely to approve of police use of force against a black suspect compared to a white suspect. White respondents, on the other hand, made no distinction between white and black suspects. In contrast, Strickler and Lawson (Citation2020) found that white respondents were less likely to view police shootings as justified when they explicitly involved a white officer and a black victim.

We considered the influence of participant ethnicity in study 2 and found that white participants were somewhat more accepting of police use of force than black participants, but this difference was not statistically significant at the p < .05 level. There was no interaction between participant ethnicity and suspect race [RQ2]. Neither black nor white participants viewed force directed against people of a different group to themselves as any more or less acceptable than force directed against people of the same group. The finding that black respondents were slightly less accepting of police use of force overall is consistent with the ‘racial perception’ gap identified in the US literature, wherein black people tend to have more negative perceptions of police use of force and are more likely to view it as unjustified (Johnson and Kuhns Citation2009, Jefferis et al. Citation2011, Boudreau et al. Citation2019, Strickler and Lawson Citation2020). It is also consistent with the well-documented pattern of more negative perceptions of police among many black communities in the UK (Bowling and Phillips Citation2002, ONS Citation2019). We also found in study 3 that black and other/mixed ethnic groups were significantly less likely to accept police use of force against a black suspect. It appears, therefore, that the perception gap found in the US may also be present in the UK.

In Study 3, we tested whether a range of prior attitudes and beliefs predicted how people process and respond to police use of force against a black suspect [RQ3]. We found the most important factor was trust in police, which had, by some margin, the largest association with acceptance. Respondents who believed the police generally act in a fair and just manner, and operate within appropriate boundaries, were significantly more likely to judge police use of force as acceptable. These findings are consistent with a host of other research showing the importance of trust, not only for people’s acceptance of police use of force (Gerber and Jackson Citation2017, Kyprianides et al. Citation2020), but whether people generally support giving police greater autonomy and discretion (Tyler and Huo Citation2002, Jackson et al. Citation2013). It may be that trusted authorities are granted legitimacy, and are therefore enabled and empowered to act on the behalf of those they govern. Equally, it may be that to trust the police is to believe officers generally behave in an appropriate manner; when confronted with a video showing the use of force, such beliefs motivate the idea that this behaviour must, too, be appropriate. To the extent people believe the police are trustworthy and legitimate authorities, they also tend to judge specific police decisions and activities as just and proper including, here, the police decision to use force.

Our findings showed that racial prejudice was also influential. Controlling for all other variables in the model, people who reported having at least some level of prejudice against other races were significantly more accepting of police use of force against a black suspect. Conflict theory and group threat/position suggest that different attitudes toward police use of force may stem, in part, from a belief in the police’s ability to protect the interests of the dominant group and maintain the status quo (Choongh Citation1998). Prior experimental research from the US has shown that, among white respondents, anti-black racial stereotyping and racial resentment is linked to the approval of police use of excessive and reasonable force against black suspects (Johnson and Kuhns Citation2009), and to the disapproval of police shootings involving a black officer and a white victim (Strickler and Lawson Citation2020). Other, non-experimental, US-based research has also found that racial animus and prejudice is associated with support for police use of excessive force (Barkan and Cohn Citation1998, Silver and Pickett Citation2015). It seems that racial prejudice is an important consideration in understanding how people in the UK, too, respond to police use of force.

There are a number of limitations to this paper that should be acknowledged. First, the experimental conditions under which this study took place are no substitute for a real world setting, where any situation will be far more complex than can be captured with an experimental design. Second, restricting our race categorisations to white, black and Asian masks the heterogeneity within racialised groups living in the UK, and does not accurately reflect the nuances of ethnic identity and the different experiences of members belonging to these groups. In reality, ethnic and racial categorisation is a much more complex, fluid and highly contextualised process.

Third, in study 1 we piloted an implicit race manipulation using names and geographic locations but found that a large proportion of participants classified the white suspect as black. Whether this was the result of implicit biases or stereotypes, or simply the fact that people were more easily able imagine a situation where police used force against a black suspect, the findings suggest that these types of implicit race cues may be difficult to use in a policing context, especially one where racial disproportionately is present. Although implicit race primes may help overcome the effects of social desirability bias, future research should explore the utility of these types of primes in criminal justice contexts.

Fourth, in study 3, it is possible that asking participants their views of the police, crime, authoritarianism, etc. prior to viewing the video influenced their responses to the encounter. Although we were interested in understanding how prior attitudes and beliefs influence reactions to police use of force, and everyone was exposed to the same set of survey items, we cannot rule out the possibility that participants were differentially primed by the questions used. Lastly, there are the typical concerns about the reliability, generalisability and validity of the data as a result of using a non-probability convenience sample recruited from a crowdsourcing platform. Further, due to the self-report format and sensitive subject matter, all our findings could be affected by social desirability and other response biases. Future investigation should seek to explore these issues with more robust methodologies.

Conclusion

Issues of race and policing have featured in public debates and scholarly discourse for decades, and the recent protests in the US, UK, and across the world have brought these issues firmly to the forefront. This paper provides the first empirical test with a British sample of whether the race of the suspect influences people’s judgements about the acceptability of police use of force. Our findings are equivocal about the impact of suspect race. There was no main effect of suspect race in either study, yet results from studies 2 and 3 suggest a similar pattern to US research (e.g. Johnson and Kuhns Citation2009): black participants are less accepting of police use of force than white participants, and particularly when the suspect in question is black. Given the historically low levels of trust and confidence in police within many black communities, these results are not surprising but do highlight the way reactions to police activity are conditioned by group membership(s).

Our findings also speak to the wider importance of trust in shaping acceptance of police activity. It would seem that support for police use of force in our vignettes was determined in large part by what people already thought of police. Also important were people’s prior levels of racial prejudice. The attitudes and beliefs people bring with them to an encounter (as participant or in our case onlooker) may be central in shaping how they read and process police actions.

Our study has, therefore, cast new light on the question as to why British police have not faced a fundamental public reckoning in the face of continued disproportionate use of force against individuals from, in particular, black minority ethnic groups. For some, this may simply be down to racism – in study 3, those who admitted to prejudiced views were more accepting of the use of force against a black suspect. Yet, studies 1 and 2 demonstrated that on average people did not judge force against black suspects as any less or more acceptable than force against white suspects. This is not to say they were ‘colour blind’, just that other factors seem to have been more important; particularly, it seems, trust in the police. In a country where overall levels of trust in police remain high (Police Foundation Citation2020b), it may be that people who trust the police will tend to ignore, discount, or justify use of force, regardless of who it is applied to.

This is not to suggest that police have carte blanche. Clearly, there will be limits to what people will accept, and future work probing these limits may throw much light on the dynamics of police-public relations. But the findings presented here may go some small way to explaining the stability in public views and acceptance of the use of police powers and application of force, even when such powers are shown to be applied disproportionately.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (202.4 KB)Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to Dr. Will Keating-Jones (Sussex Police) for his help with the experimental material and to the officers who were photographed for the purpose of the vignettes.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 We use the term ‘disproportionate’ to mean that a certain group of people is affected by police action in a way that is substantially different from people not of that group.

2 These figures exclude the Metropolitan Police Service.

3 The grassroots Black Lives Matter movement originated in America following the acquittal of George Zimmerman after shooting and killing 17-year-old Trayvon Martin in Florida in 2012. It has harnessed social media (particularly twitter) as a platform to shape national and international discourse on police violence and racism (Carney Citation2016).

4 Both race and ethnicity are social constructs used to categorise distinct populations. Race is usually associated with physical characteristics, whereas ethnicity is linked with cultural expression and identification. One crucial difference between the concepts of race and ethnicity is that the latter is by definition subjective. ‘Whether a particular group of people can be counted as an ethnic or cultural group is a matter for the members of that group to decide, not for outside observers to stipulate’ (Schneider and Heath Citation2020, p. 536). People place themselves into ethnic groups; race, by contrast, tends to be something that is assigned to an individual or group by external processes, as in Jim Crow era US and apartheid South Africa. In this paper we predominantly use the term race to align with police data and situations where limited information is available about an individual’s self-defined ethnic background (i.e. in encounters between police and members of the public). However, we use the term ethnicity when discussing the participants in our research because they have self-categorised their own ethnic background.

5 In the UK, the largest minority ethnic groups are those from South Asian (e.g. Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, 6.8%), and black (e.g. African and Caribbean, 3.4%) backgrounds (Statista Citation2021). In this paper we use the terms Asian and black to refer to these groups, although we acknowledge the drawbacks of making such broad categorisations against a reality that is fluid and highly contextualised.

6 Eight participants were excluded from study 1, zero from study 2, and two from study 3 for getting more than one attention check wrong.

7 We chose the baton as the weapon because people were the least accepting of this police tactic in previous work (Kyprianides et al. Citation2020).

8 Richmond is a borough in the south-west of London; 86% of its residents are white. Brixton is a district in the borough of Lambeth in the south of London; a large proportion of its residents (30%) are of black Caribbean and black African background. Whitechapel is a ward in the borough of Tower Hamlets in the east of London; a large proportion (38%) of its residents are of Bangladeshi origin. Because participants in this study were residents of London, we reasoned they would be familiar enough with these locations that providing geographic information alongside names would act as a strong race cue.

9 Rather than classifying these suspects as another race, most participants who misclassified race stated they did not know the race of the suspect.

10 Although there were some differences between white and black participant characteristics (e.g. black participants were younger and a greater proportion had been born in the UK), analysis showed these factors had no influence on people’s judgements about the acceptability of police action.

11 Analyses were repeated excluding these participants and results remained the same.

12 The video is in the public domain and depicts a real-life incident; see Supplementary Appendix.

13 We estimated a structural equation model to further explore whether trust acts as a mediator. There was a significant indirect relationship between authoritarian attitudes and acceptance of police use of force through trust in police (β = 0.17 [0.06], p < .01).

References

- Allport, G.W., and Postman, L.J., 1947. The psychology of rumor. New York: Russell & Russell.

- Barkan, S.E., and Cohn, S.F., 1998. Racial prejudice and support by whites for police use of force: a research note. Justice quarterly, 15 (4), 743–753. doi: 10.1080/07418829800093971

- Bertrand, M., and Mullainathan, S., 2004. Are Emily and Greg more employable than Lakisha and Jamal? A field experiment on labor market discrimination. American economic review, 94 (4), 991–1013. doi: 10.1257/0002828042002561

- Blalock, H.M., 1967. Toward a theory of minority-group relations. New York: Wiley.

- Blumer, H.G., 1958. Race prejudice as a sense of group position. Pacific sociological review, 1 (1), 3–7. doi: 10.2307/1388607

- Bonilla-Silva, E., 2006. Racism without racists: color-blind racism and the persistence of racial inequality in the United States. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Boudreau, C., MacKenzie, S.A., and Simmons, D.J., 2019. Police violence and public perceptions: an experimental study of how information and endorsements affect support for law enforcement. The journal of politics, 81 (3), 1101–1110. doi: 10.1086/703540

- Bowling, B., and Phillips, C., 2002. Racism, crime and justice. Essex: Pearson.

- Bowling, B., Reiner, R., and Sheptyki, J., 2019. The Politics of the police. 5th ed. Oxford: OUP.

- Bradford, B., et al., 2017. A leap of faith? Trust in the police among immigrants in England and Wales. British journal of criminology, 57 (2), 381–401.

- Bradford, B., et al., 2020. Live facial recognition: trust and legitimacy as predictors of public support for police use of new technology. British journal of criminology, 60 (6), 1502–1522.

- Bradford, B., Murphy, K., and Jackson, J., 2014. Officers as mirrors: policing, procedural justice and the (re) production of social identity. British journal of criminology, 54 (4), 527–550. doi: 10.1093/bjc/azu021

- Burke, M.A., 2017. Racing left and right: color-blind racism’s dominance across the U.S. political spectrum. The sociological quarterly, 58 (2), 277–294. doi: 10.1080/00380253.2017.1296335

- Carney, N., 2016. All lives matter, but so does race: black lives matter and the evolving role of social media. Humanity & society, 40 (2), 180–199. doi: 10.1177/0160597616643868

- Chandler, J., and Paolacci, G., 2017. Lie for a dime: when most pre-screening responses are honest but most study participants are imposters. Social psychological and personality science, 8 (5), 500–508. doi: 10.1177/1948550617698203

- Choongh, S., 1998. Policing the dross: a social disciplinary model of policing. British journal of criminology, 38 (4), 623–634. doi: 10.1093/bjc/38.4.623

- Cohen, S., 2001. States of denial. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Dalbert, C., Montada, L., and Schmitt, M., 1987. Belief in a just world: validation correlates of two scales. Psychologische beitrage, 29, 596–615.

- Davies, T., et al., 2020. Visibly better? Testing the effect of ethnic appearance on citizen perceptions of the police. Policing and society, doi:10.1080/10439463.2020.1853124.

- Devine, P.G., 1989. Stereotypes and prejudice: their automatic and controlled components. Journal of personality and social psychology, 56 (1), 5–18. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.56.1.5

- Eaton, A.A., et al., 2019. How gender and race stereotypes impact the advancement of scholars in STEM: professors’ biased evaluations of physics and biology post-doctoral candidates. Sex roles, 82 (3), 127–141.

- Eberhardt, J.L., et al., 2004. Seeing black: race, crime, and visual processing. Journal of personality and social psychology, 87 (6), 876–893. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.87.6.876

- Eberhardt, J.L., et al., 2006. Looking death-worthy: perceived stereotypicality of black defendants predicts capital-sentencing outcomes. Psychological science, 17 (5), 383–386. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01716.x

- Gerber, M.M., and Jackson, J., 2017. Justifying violence: legitimacy, ideology and public support for police use of force. Psychology, crime & law, 23 (1), 79–95. doi: 10.1080/1068316X.2016.1220556

- Girgenti-Malone, A.A., et al., 2017. College students’ perceptions of police use of force: do suspect race and ethnicity matter? Police practice and research, 18 (5), 492–506. doi: 10.1080/15614263.2017.1295244

- Glaser, J., 2015. Suspect race: causes and consequences of racial profiling. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Heath, A., Evans, G., and Martin, J., 1994. The measurement of core beliefs and values: the development of balanced socialist/laissez faire and libertarian/authoritarian scales. British journal of political science, 24 (1), 115–132. doi: 10.1017/S0007123400006815

- Home Office. 2020. Police use of force statistics, England and Wales: April 2019–March 2020. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/police-use-of-force-statistics-england-and-wales-april-2019-to-march-2020.

- Jackson, J., et al., 2013. Just authority? Trust in police in England and Wales. Oxon: Routledge.

- Jefferis, E., Butcher, F., and Hanley, D., 2011. Measuring perceptions of police use of force. Police practice and research: an international journal, 12 (1), 81–96. doi: 10.1080/15614263.2010.497656

- Johnson, D., and Kuhns, J.B., 2009. Striking out: race and support for police use of force. Justice quarterly, 26 (3), 592–623. doi: 10.1080/07418820802427825

- King, E.B., et al., 2006. What's in a name? A multiracial investigation of the role of occupational stereotypes in selection decisions. Journal of applied social psychology, 36 (5), 1145–1159. doi: 10.1111/j.0021-9029.2006.00035.x

- Kyprianides, A., et al., 2020. Perceptions of police use of force: The importance of trust. Policing: an international journal, 44 (1), 175–190. doi: 10.1108/PIJPSM-07-2020-0111

- Lammy, D. 2017. The Lammy Review. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/lammy-review-final-report.

- Lewis, P., et al. 2011. Reading the Riots: Investigating England’s summer of disorder.

- Loader, I. and Mulcahy, A. 2003. Policing and the Condition of England: Memory, Politics and Culture. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Macpherson, W. 1999. The Stephen Lawrence inquiry. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/277111/4262.pdf.

- Milani, J., 2020. Political ideology, racism, and American identity: an examination of white Americans’ support for the police use of excessive force. Dissertation, University of Oxford.

- Mullinix, K.J., Bolsen, T., and Norris, R.J., 2020. The feedback effects of controversial police use of force. Political behavior, doi:10.1007/s11109-020-09646-x.

- Omi, M., and Winant, H., 2018. Racial formation in the United States. New York: Routledge, 276–282.

- ONS. 2019. Confidence in the local police. Available from: https://www.ethnicity-facts-figures.service.gov.uk/crime-justice-and-the-law/policing/confidence-in-the-local-police/latest.

- Peffley, M., and Hurwitz, J., 2010. Justice in America: the separate realities of blacks and whites. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Police Foundation, 2020a. Public safety and security in the 21st century. London: The Police Foundation.

- Police Foundation, 2020b. Policing and the public: understanding public priorities, attitudes and expectations. London: The Police Foundation.

- Radburn, M., et al., 2018. When is policing fair? Groups, identity and judgements of the procedural justice of coercive crowd policing. Policing and society, 28 (6), 647–664. doi: 10.1080/10439463.2016.1234470

- Roché, S., and Roux, G., 2017. The “silver bullet” to good policing: a mirage. Policing: an international journal, 40 (3), 514–528. doi: 10.1108/PIJPSM-05-2016-0073

- Rome, D.M., Son, I.S., and Davis, M.S., 1995. Police use of excessive force: does the race of the suspect influence citizens’ perceptions? Social justice research, 8 (1), 41–56. doi: 10.1007/BF02334825

- Safi, M. 2020. George Floyd killing triggers wave of activism around the world. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2020/jun/09/george-floyd-killing-triggers-wave-of-activism-around-the-world.

- Scarman, L.G., 1981. The Brixton disorders 10–12 April 1981: report of an inquiry by the Rt. Hon. The Lord Scarman, O.B.E. London: HMSO.

- Schneider, S.L., and Heath, A.F., 2020. Ethnic and cultural diversity in Europe: validating measures of ethnic and cultural background. Journal of ethnic and migration studies, 46 (3), 533–552. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2018.1550150

- Silver, J.R., and Pickett, J.T., 2015. Toward a better understanding of politicized policing attitudes: conflicted conservatism and support for police use of force. Criminology, 53 (4), 650–676. doi: 10.1111/1745-9125.12092

- Statista. 2021. Ethnicity in the United Kingdom. Available from: https://www.statista.com/statistics/270386/ethnicity-in-the-united-kingdom/.

- Strickler, R., and Lawson, E., 2020. Racial conservatism, self-monitoring, and perceptions of police violence. Politics, groups and identities, doi:10.1080/21565503.2020.1782234.

- Testa, P., and Dietrich, B.J., 2017. Seeing is believing: How video of police action affects criminal justice beliefs. San Francisco, CA: American Political Science Association.

- Trinkner, R., Jackson, J., and Tyler, T.R., 2018. Bounded authority: expanding “appropriate” police behavior beyond procedural justice. Law and human behavior, 42 (3), 280–293. doi: 10.1037/lhb0000285

- Tyler, T.R., and Huo, Y., 2002. Trust in the law: encouraging public cooperation with the police and courts. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Watson, S., Appiah, O., and Thornton, C.G., 2011. The effect of name on pre-interview impressions and occupational stereotypes: the case of black sales job applicants. Journal of applied Social psychology, 41 (10), 2405–2420. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2011.00822.x

- Yesberg, J.A., and Bradford, B., 2019. Affect and trust as predictors of public support for armed police: evidence from London. Policing and society, 29 (9), 1058–1076. doi: 10.1080/10439463.2018.1488847