ABSTRACT

Evidence shows that the application of problem-oriented policing can be effective in reducing a wide range of crime and public safety issues, but that the approach is challenging to implement and sustain. This article examines police perceptions and experiences regarding organisational barriers to and facilitators of the implementation and delivery of problem-oriented policing. Drawing on surveys of (n = 4141) and interviews with (n = 86) police personnel from 19 police forces in England and Wales, we identify five key barriers and facilitators to problem-oriented policing: leadership and governance, capacity, organisational structures and infrastructure, partnership working and organisational culture. These factors provide important indicators for what police organisations need to do, or need to avoid, if they are to successfully embed and deliver problem-oriented policing. The article generates critical information about the processes that drive change in police organisations and offers recommendations for police managers who may wish to implement or develop problem-oriented policing. The paper also proposes a research agenda aimed at addressing evidence gaps in our understanding of the implementation and sustenance of problem-oriented policing.

Introduction

Problem-oriented policing (also known as problem-solving) is an approach which calls for in-depth exploration of the substantive problems that the police are called on to tackle and the development and evaluation of tailor-made responses to them (Goldstein Citation1990, Eck Citation2019). The practice of problem-oriented policing usually involves four main processes, encapsulated by Eck and Spelman's (Citation1987) SARA model: scanning (identifying) a problem that harms the community and falls within the police remit, analysing the problem to identify pinch points for intervention, developing responses to the problem based on problem analysis, and evaluating the impact of those responses to determine if the problem has been resolved.

Problem-oriented policing was developed in the context of a need for greater efficiency and effectiveness within police work (Goldstein Citation1979, Citation1990). Goldstein (Citation1979, Citation1990) was critical of traditional police responses to crime which tended to be incident driven and characterised by rapid response to calls for service, follow up investigations with the aim of apprehending a criminal suspect and random patrols. Research has consistently demonstrated the failures of these strategies to effectively control crime (e.g. Kelling et al. Citation1974, Spelman and Brown Citation1984). Indeed, it is generally accepted that there is weak or, at best, mixed evidence regarding the effectiveness of the so-called standard model of policing (Skogan and Frydl Citation2004, Weisburd and Eck Citation2004).

By contrast, problem-oriented policing has repeatedly been shown to have a positive impact on a wide range of crime and public safety issues (Weisburd et al. Citation2008, Citation2010, Hinkle et al. Citation2020, Scott and Clarke Citation2020). The UK College of Policing go as far as to describe problem-oriented policing as ‘one of the best-evidenced policing strategies’.Footnote1 However, despite extensive evidence about the effectiveness of problem-oriented policing, over forty years of research and practice has identified recurrent challenges both in the implementation and delivery of a problem-oriented approach (Read and Tilley Citation2000, Scott Citation2000, Goldstein Citation2018). Common weaknesses include limited or basic scanning and analysis, an over-reliance on police data, responses that tend to emphasise traditional enforcement, and poor assessments of the impact of chosen responses (e.g. Scott Citation2000, Bullock et al. Citation2006, Goldstein Citation2018). In light of these challenges, enthusiasm for and commitment to problem-oriented policing has waxed and waned over the past forty years, with the history of problem-oriented policing best characterised as a series of isolated projects rather than an approach which has diffused through and remained within police organisations (Goldstein Citation2018). As Goldstein (Citation2018, p. 3) himself put it on receiving the 2016 Stockholm Prize for Criminology:

I have grown accustomed to viewing successful efforts to implement POP – when carried out in all of its full dimensions – as episodic rather than systematic; as the results of relatively isolated cells of initiative, energy and competence. I view these pockets of achievement as exciting and pointing the way but sprinkled among a vast sea of police operations that remain traditional and familiar.

That problem-oriented policing has proven challenging to implement and sustain can be understood against the wider backdrop of innovation diffusion. There is an extensive body of work that demonstrates that implementing new strategies is challenging and that many strategies devised by organisations are never implemented (see, for example, Alexander Citation1985, Al Ghamdi Citation1998, Aaltonen and Ikävalko Citation2002, Atkinson Citation2006). In the context of policing, since the 1980s there has been a regular supply of new and diverse policing approaches which share the common feature of seeking to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of police work. Approaches have emphasised an association with intelligence, community, evidence, big data, early intervention and public health (Kirby and Keay Citation2021). Currently, there is a paucity of evidence to show how many of these approaches have made a significant impact across mainstream policing. Several reasons may be suggested for this: the theory underpinning the reforms is poorly conceived; the approach cannot be operationalised for various reasons (which might include insufficient resources or poor skills); or there is a lack of evaluation evidence to show the efficacy of the approach (Rosenbaum Citation1986). Commentators also report that the choice of policing approaches are often made subjectively, with the emphasis on internal rather than external customer requirements (Seddon Citation2008, Wandersman Citation2009). Whatever the reason, there is increasing recognition that implementation failure is frequently associated with the management of change within police organisations (Kirby Citation2013). This generates significant wastage and cost – be it through the writing of failed processes, the implementation of failed structures, or the cost of inappropriate training, audit and inspection (Kirby Citation2013). It can also demoralise staff who witness the introduction and failure of these approaches (Pekkanen and Niemi Citation2013).

In the context of problem-oriented policing specifically, previous studies have drawn attention to the features of the police organisation that can facilitate or inhibit the adoption of problem-oriented ways of working (Read and Tilley Citation2000, Scott Citation2000). These include leadership, the presence of committed and enthusiastic proponents and practitioners, analytical capacity, the availability of data and the use of training. However, in light of the strong evidence in support of the effectiveness of problem-oriented policing, we argue that it is important to continually assess what conditions can support, or hinder, its delivery. This is to reduce wasted cost and effort associated with the poor choice of policing approach or failed implementation. Moreover, many of the previous studies on the barriers to and facilitators of problem-oriented policing are now somewhat dated. There have been significant changes in the practice and governance of policing in England and Wales, as in other parts of the world, which may have implications for how problem-oriented policing is viewed and how it operates. There have been changes that, in theory at least, ought to facilitate the delivery of problem-oriented policing. These include, but are by no means limited to, the development of technology that supports crime analysis; a growing emphasis on evidence-based policing; and the dominance of neighbourhood and community policing styles which tend to advocate problem-solving. Despite the development of what ought to act as facilitators of the approach, many of the barriers to the delivery of problem-oriented policing remain. This serves to illustrate the importance of reviewing the conditions that facilitate and undermine the diffusion of reform movements in policing. Given what is known about the benefits associated with problem-oriented policing, when delivered properly, it is essential that barriers and facilitators are better understood so that the police can be supported in both delivering and maximising the benefits of a problem-oriented approach.

This article then builds on existing research in the field of problem-oriented policing and examines the contemporary organisational structures, practises and resources believed to promote and maintain its implementation as practiced in England and Wales in 2019. Drawing on survey data and interviews with 19 police forces, this article considers the conditions which need to be in place to increase the likelihood that problem-oriented policing will be successfully established considering both the barriers and facilitators of the approach. This is important if organisations are going to get the best out of strategies which are known to be effective in reducing crime.

Analytical approach

The findings reported here are derived from a larger study on the extent, nature and patterns of problem-oriented policing in England and Wales in 2019 (Sidebottom et al. Citation2020). In particular, we draw on two data sources collected as part of that larger study: an anonymous online survey and semi-structured interviews.

Survey

We administered a survey in nineteen of the 43 geographical police services in England and Wales. The survey sample was devised in two ways. It comprised eight purposefully selected police forces. They were selected to ensure that there was a representation of forces with different histories of problem-oriented policing. For example, to include some with a history of implementing problem-oriented policing (as determined by the authors) and some who had less experience of delivering the approach. This purposefully selected sample also helped ensure that there was a mixture of participating police forces in terms of the nature and size of forces (urban/rural, metropolitan and so on). The remaining forces were selected randomly. The full survey consisted of forty-four questions organised into eight sections (see Sidebottom et al. Citation2020, p. 67).

In the survey, participants were shown a series of statements and asked to indicate if they tended to agree or disagree with each one. The statements were presented in random order. Each statement was presented in two versions (one the opposite of the other) with each participant presented with one at random. Answers to the ‘negative’ versions of each statement (i.e. those in the form of ‘I do not agree that … .’) were then reversed for analysis. The statements related to whether participants believed that they had: (1) the time and resources to do effective problem solving; (2) access to the information they needed to resolve crime and disorder issues; (3) sufficient training in problem-oriented policing; (4) access to information on how to carry out problem solving; and (5) access to an intelligence analyst to support problem-oriented work. Participants were also asked two free-text questions relevant to this study: (1) Based on your experience of problem solving, what do you think are the main barriers (if any) to practising problem solving in your police force? and (2) What (if anything) do you believe can be done to promote the use of problem solving in your police force? Free-text responses were manually coded and categorised in the same way as the interview data, described below.

The survey population was all police officers and staff in the participating nineteen police forces. In each force except one, an invitation to take part in the online survey was either emailed to all officers and staff by a senior officer or distributed via an existing intranet site or newsletter. In the final force, the invitation was sent to unit commanders who decided whether to distribute it to officers and staff within their units.

All survey data were included in the analysis, with no data excluded. Analysis was performed using R version 3.6.1. Since all the survey questions were optional, the number of respondents answering each question varied. A total of 4141 respondents accessed the online survey, with 2621 (63%) continuing to the final questions. Assessment of the proportion of respondents answering each question revealed no discernible patterns or explanations for the observed attrition in survey responses. Of those respondents who gave their rank, 72% were police officers, including 47% of all respondents who were regular police constables or detective constables. Compared to the police workforce of the surveyed forces, we found that survey respondents were more likely to be supervisory police officers (i.e. of sergeant rank or above) than police constables, community support officers or police staff. Among respondents who specified their role, 358 said they worked in a neighbourhood role, 453 in response policing and 1688 in other roles. No respondent self-identifying as a Chief Officer completed the survey. Beyond rank or grade, 73% of survey respondents reported having more than 10 years’ experience, with only 7% having less than two years’ experience and only 21% being aged under 35. Of those respondents giving an answer, 41% (42% of officers and 37% of staff/volunteers) reported having a bachelor’s degree or higher qualification, while 8% reported currently studying for a qualification. Of the respondents who stated their gender, 60% (66% of officers and 45% of staff/volunteers) were male. The 4141 respondents in this survey represent 2.6% of the full-time equivalent regular police officers and 1.5% of police staff/volunteers in the forces involved in the survey.

Interviews

The second type of data used here comes from semi-structured interviews conducted in the purposefully selected eight police forces. In each of these forces, the nominated point of contact was asked to provide the authors with a list of between ten and fifteen individuals in their organisation who were involved in or knowledgeable about problem-oriented policing, and had the competency to provide an informed view on the subject. No restrictions were placed on the rank or role of identified individuals. In this sense, interview participants can be considered ‘key informants’ – individuals who were knowledgeable and experienced about problem-oriented policing – rather than a general sample of police personnel.

Across the eight police forces purposefully selected to partake in the interview part of this study, we received the names of 118 candidate interviewees. All were contacted by the research team and 86 (72%) consented to be interviewed. The final sample of interviewees covered a wide range of roles, ranks and grades from Police Community Support Officers (n = 4) and police constables (n = 10) to Chief Officers (n = 7) and crime analysts (n = 6). Interviews took place either face-to-face on police premises or via telephone. The objective of the interviews was to examine the experiences and perspectives of an informed group of problem-oriented policing practitioners in England and Wales. To this aim, participants were asked to describe their experiences of problem-oriented policing and the features that they felt facilitated or acted as barriers to the approach. Interviews were digitally recorded and fully transcribed. Analysis followed an iterative process of coding and theme development (Braun and Clarke Citation2006). This involved reading and re-reading all interview transcripts and noting down initial ideas on emerging themes; generating initial codes based on the preliminary set of themes; searching for broader themes by collating codes into higher-order topics, and gathering all data relevant to each potential theme; reviewing themes and mapping them across the data sets; ongoing refinement of themes into an overarching narrative or story; and selecting examples and quotations that illustrated the final themes. The current study was reviewed and exempted by the University College London ethics board.

Results

Survey results

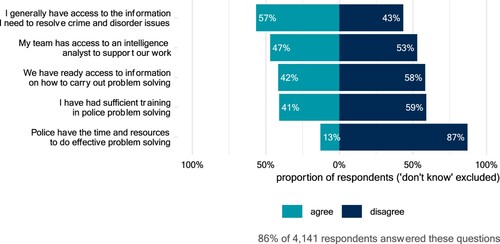

As noted, survey respondents were asked whether they agreed or disagreed with a series of statements regarding their ability to do problem-solving (n = 3561) and the barriers to and facilitators of a problem-oriented approach (n = 1129). In respect to the former, survey respondents identified various obstacles to doing problem-solving (). Around two-thirds of respondents (59%) disagreed with the statement that they had received sufficient training in problem-solving. Just over half of respondents (53%) said their team did not have access to an intelligence analyst to support their work. Forty-three per cent of respondents said they did not have access to the information needed for effective problem-solving and 58% indicated that they did not have access to information on how to solve problems. Only 13% of respondents agreed that they had the time and resources to do effective problem-solving.

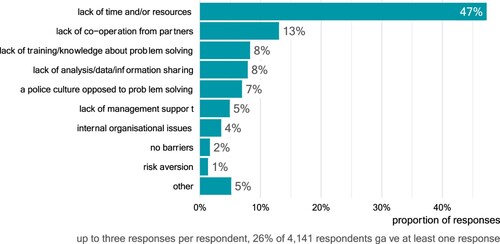

Consistent with the findings presented in , the most frequently identified barrier to problem-solving in the free text question () was a lack of time and/or resources dedicated to problem-solving (54%). This was followed (in descending order) by a lack of co-operation and engagement from partners (15%), a lack of training on and/or understanding of problem-solving (9%), a lack of analytical capacity or information sharing (9%), the culture of the police (8%) and a lack of senior support for problem-solving (6%).

Figure 2. Survey participants responses on the most common barriers to problem-solving (Free-text answers were coded by the authors).

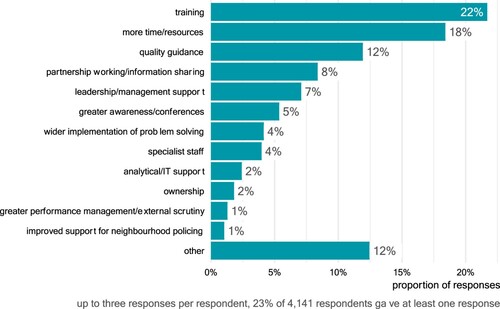

The survey respondents who were asked to identify barriers to problem-solving were also questioned on what they saw as key facilitators (). Many of the suggested enablers are the converse of the barriers described above, namely the need for more and better training (22%) and dedicated time and/or resources for problem-solving (19%). The third most commonly identified enabler was quality guidance, including success stories and evidence of ‘what works’ (12%). Other cited enablers were leadership and/or management support (7%), partnership working and/or information sharing (7%), and greater awareness of problem-solving (typically discussed in relation to conferences) (6%). Many of the barriers and facilitators of problem-solving discussed in the survey were similar to those revealed in the interview analysis, to which we now turn, discussing the findings in greater detail.

Interview results

Leadership and governance

A major theme in the accounts of interview participants was that the endorsement and support of police leaders is key for the successful implementation of problem-oriented policing. This was discussed both in terms of senior leaders allocating the resources needed to embed problem-oriented policing but also as a way of sending out a message that the senior leadership team are committed to a problem-oriented approach. For this interview participant: ‘So it’s like everything else isn’t it, if you want to culturally embed a new approach then it has to be driven from the top’ [F16: Respondent 1004] and

I think at executive level, you’ve got to have the buy in, you’ve got to have that top-level support and that top-level sort of belief in problem solving. I think that’s really important because otherwise, who drives it and who puts the resources into it? So you’ve got to have that input. [F18: Respondent 1028]

Interview participants converged on the finding that where senior support for problem-oriented policing is present, this will act as a facilitator and where it is absent this will act as a barrier. For this interview participant:

I think organisationally you’ve got to have the right level of support. It’s got to be, we have seen that in [named force] in terms of when it’s led by the leaders and it’s valued and the staff understand that there is value in that approach and if you haven’t got that, then there’s a real challenge with it. [F14: Respondent 1068]

Interview participants described some of the difficulties in embedding problem-solving when senior leaders are not committed to the approach, for example: ‘The whole of the top corridor from superintendent upwards … have all got CID (Criminal Investigation Department) backgrounds. So problem-solving is only something that’s done in neighbourhoods, as far as they’re concerned’ [F22: Respondent 2017]. Moreover, many interview participants attributed the characteristic rise and fall of problem-solving to changes in police leaders. As one interview participant lamented of his own force: ‘A lot of our key champions left, so (named person) retired and (named person) left us as well […] If you don’t have that kind of leadership then it’s very difficult to sustain it’ [F14: Respondent 1065].

Whilst weight was often placed on the active sponsorship of chief officers, leaders lower down the police hierarchy were also commonly viewed as important facilitators of (or barriers to) problem-oriented policing. As one interview participant explained: ‘I think you’ve got to have the borough senior leaders, the chief superintendents, to say that they think it’s worthwhile as well, and try and endorse it, and encourage it’ [F20: Respondent 1037]. These lower-level leaders, who are situationally closer to front line officers, may facilitate delivery by positively reinforcing messages from chief officers. Conversely, if they were resistant, their actions and attitudes may form a barrier. As one interview participant put it:

The most important thing is to get your inspector cohort signed up in delivering problem solving because they’re the real key change agents in any force. It’s the inspector rank, because they’re the ones who are there 2am as the most senior rank. So if they’re the ones who are constantly going to take a step back from problem solving, you’ll never land it. They are the key people. And to do that you have to invest in that inspector cohort. [F18: Respondent 1020]

Likewise, the presence of ‘champions’ or strategic leads were similarly identified as a way of facilitating the delivery of problem-oriented policing. These ‘champions’ would be highly committed to problem-oriented policing and be able to effectively communicate its virtues and inspire officers. As one interview participant noted:

we have somebody dedicated centrally who is driving it out to, whether it’s boroughs, whether it’s through sectors, however, the constabularies work, to ensure that they’ve got somebody who’s championing it, who’s got that interest, understands what needs to be done and can push it and drive it. [F20: Respondent 1039]

Supportive management and supervision were also thought to facilitate problem-oriented policing by giving officers the license to conduct this work. For one interview participant:

Massively important, if you haven’t got the support of the line manager it fails at the first hurdle because I can’t go to other areas of business within our [police division], within the police, and say, this is our policy what we’re doing if my line management is not supporting me because I haven’t got that authority to do it. [F20: Respondent 1041]

Capacity

Problem-oriented policing is not conventional policing. It calls on the police to work creatively and collaboratively and engage in open-ended enquires to better understand and respond to presenting problems. It is not surprising, therefore, that capacity – notably time to conduct problem-oriented policing – was viewed as a primary facilitator of or barrier to problem-oriented policing. In the context of recent cuts to police budgets in England and Wales (HASC Citation2018, Higgins Citation2018), participants drew attention to how reduced staff levels have acted as a barrier to problem-oriented policing. For one interview participant:

I think it has got its challenges around having the availability of staff and resource to do it […] It has been put as a priority but then everything is at the moment, until we get some more staff in. [F15: Respondent 1074]

Organisational structures and infrastructure

Several features of the police infrastructure were seen to facilitate or act as a barrier to the diffusion of problem-oriented policing. Delivery was thought to be facilitated by providing a mechanism to oversee the quality of problem-oriented work and ensure that officers did not revert to traditional (reactive) policing approaches. As this interview participant put it:

the auditing of that [problem solving] process and the supervision of that process needs to be done so the best training is always backed up with robust, and I mean robust, supervision because it’s funny really because people are people and they go back to type. [F12: Respondent 1046]

There was a general belief that the delivery of problem-oriented policing would be facilitated by embedding it into personal development and performance development review (PDR) (see also Metcalf Citation2001, Braga Citation2002, Bullock et al. Citation2006). As one participant put it:

I think that is something that could be done whether that be part of peoples PDR processes, so setting objectives around making sure that problem solving is at the forefront of what they do and for them to continually get evidence. [F12: Respondent 1045]

The availability of formal systems to plan and record the progress of problem-oriented projects was perceived to facilitate implementation by structuring activity, providing a record of achievement, enabling oversight of the quality and impact, and eventually by providing a repository of case studies from which others could learn (see also Read and Tilley Citation2000, Bullock et al. Citation2006). Whilst generally seen as important for facilitating implementation, certain critical reflections on these structures were offered by participants. First, there was some debate about whether the availability of systems leads to good quality problem-solving. As one put it, ‘Having a POP plan doesn’t necessarily resolve the issue, you need to do the actions behind the POP plan obviously, don’t you?’ [F16: Respondent 1006]. Clearly, simply writing a plan does not mean a problem will be resolved. However, systematic failure to record projects was thought likely to represent systematic failure to do problem-solving properly. As one put it: ‘All our cases in the hub will have a POP plan, all of them because, without it, you’re just jumping into the dark, aren’t you?’ [F13: Respondent 1060].

Second, the mechanisms for recording problem-solving activity were sometimes described as not user-friendly and/or potentially daunting for users. As one put it: ‘The form looks daunting when you see it and you think, “Oh my gosh”’ [F13; Respondent 1055]. For officers, this may be an issue as there is a preference for action rather than filling in forms (see also Bullock et al. Citation2006). As one stated: ‘And particularly the nature of people that join policing, they want to be outside in the fresh air, want to be out talking to the public, they don’t often want to be sat filling forms in’ [F13: Respondent 1051]. Lastly, some interview participants drew attention to how recording problem-solving activity can become merely a ‘tick box’ exercise where the forms were being filled in for presentational purposes and had little to do with good quality. In this vein, there was discussion among several interview participants of how setting quotas or targets for, say, recording a number of problem solving projects (which some forces had done or did do) could be counterproductive: ‘Right at the beginning there was a quota system introduced’ [officers were told] ‘just deliver some POP plans’ and there were people out there who didn’t have an understanding of what it delivered’ [F13: Respondent 1053]. For this reason, training and review of the plans were seen as important for ensuring good quality. As one interview participant explained:

But I think it also focuses the mind as well, doesn’t it? […] for example, I know that we’ve got those four POP plans, and they’re getting reviewed, they’re getting reviewed by our senior partner managers and so on and so forth. They’re very keen obviously for us to make the system work, and for us to solve problems, which is what it’s all about. So, having those POP plans, and the structure within those POP plans, we can evidence what we’ve done. [F16: Respondent 1006]

The availability of good quality training was widely recognised to be a facilitator of problem-oriented policing. However, participants drew attention to how training to date had been limited and somewhat ad hoc (see also Goldstein Citation1990, Read and Tilley Citation2000, Bullock et al. Citation2006). Some interview participants struggled to recall having received any training at all:

There is, I think, some problem-solving input they get but I don’t think it’s wide […] I’ll be honest with you; off the top of my head, I can’t sit here and say I’ve had any training personally about problem solving. [F20: Respondent 1041]

[We] used to train all neighbourhood officers on a five-day course and that ceased in 2011. Then up until 2011 to 2016 there was no [problem-solving] training for neighbourhood officers, either those who were already on there as a refresher or for those who joined. [F20: Respondent 1036]

Availability of guidance was also seen by participants to facilitate problem-oriented policing. Whilst there is a large amount of guidance available on many aspects of problem-oriented policing (see, for example, the Centre for Problem-oriented Policing) interview participants still suggested that a lack of guidance was currently acting as a barrier to effective problem-oriented policing. The availability of simple, clear guidance that is easily accessible was seen as a facilitator of problem-oriented policing. As one interview participant put it:

Personally, I think we have to keep things very simple, stuff like the SARA acronym and that approach is really good. You know, in terms of the toolkits, et cetera, they’re very good, we just need to make them available and communicate them down in a good way, really. [F12: Respondent 1044]

Similarly, interview participants drew attention to how a repository of examples of what is effective in tackling common problems could facilitate the implementation of problem-solving. As one interview participant put it:

I think we’ve got good understanding of what works in certain circumstances. I think we need to be able to do more to capture the effectiveness of the things that we are putting in place so that we can add to the canon of knowledge both locally, nationally and internationally. [F15: Respondent 1079]

Recognising and rewarding good problem-oriented policing was widely perceived to be a facilitator by participants (see also Read and Tilley Citation2000, Bullock et al. Citation2006). For one interview participant: ‘People like to be told they’ve done something good. It’s human nature, isn’t it […] and we embed that into our day-to-day conversations, but also with a force-wide recognition’ [F14: Respondent 1064]. Local problem-solving conferences and award ceremonies were seen by participants to be important for raising awareness, inspiring others, sharing learning, and recognising and celebrating excellence. As one interview participant explained:

I’d like to think that by having an awards ceremony which we invited people to, it kept it in the minds of people, it kept it in the minds of our colleagues, and hopefully kept it in the minds of some of the more senior officers at borough level, to get them to sort of support it and make space for it. [F20: Respondent 1037]

Disseminating success and demonstrating the benefits of problem-oriented policing to officers was similarly viewed as an important way of embedding the approach. For example, one interview participant explained that ‘it’s demonstrating that, look at this, try this, it works, and giving them the examples of how it does work’ [F20: Respondent 1039]. To facilitate implementation officers need, thus, to recognise the value of problem-oriented policing to their work: ‘It has got to be useful and meaningful to them. They’ve got to see a benefit to this. Because we work in an environment where they are constantly being asked to do things differently’ [F18: Respondent 1021].

Lastly, the presence of and access to analysts was seen by participants as an important facilitator of problem-oriented policing. Commentators have noted in previous research that a lack of analysts limits what realistically can be achieved in problem solving (Goldstein Citation1990, Read and Tilley Citation2000, Scott Citation2000, Bullock et al. Citation2006, Goldstein Citation2018). Reflecting this, few participants interviewed in this study had access to, or experience of working with an analyst. As one put it: ‘The analytical capability, I think that’s a big one. For me, if you’re going to do problem solving, you need an analytics person and that’s been a massive barrier to me and it’s a massive barrier to everybody else’ [F13: Respondent 1057]. The number of analysts within sampled police services was evidently much affected by cuts to police budgets following the 2008 global economic recession, when the number of analysts reduced substantially. In some cases, reportedly to zero. For one: ‘So … obviously this restructuring was to do with costs. We lost all of our analytical support’ [F20: Respondent 1036]. The lack of analytical support acted as a barrier to problem-oriented policing as it reduced capacity given that crime analysis is a specialist skill. To illustrate: ‘in terms of being most efficient around problem-solving, our ability to have access to good analytical product, or detailed analytical product is very difficult, or nigh on impossible to come by’ [F15: Respondent 1078].

Partnership working

Partnership working is a core principle of problem-oriented policing. Indeed, such is the importance placed on partnerships in Britain, the terms ‘problem-oriented partnership’ or ‘problem-oriented policing and partnership’ have come to be preferred to ‘problem-oriented policing’, though the underlying meaning remains the same. In this vein, it is understandable that effective partnership working was widely regarded to be an important facilitator of problem-oriented policing. Interview participants described how partners may facilitate problem-oriented policing in two main ways. First, the police do not have the powers or tools to change many of the underlying conditions thought to give rise to presenting problems or enabling them to persist. In some cases, it was felt that the responsibility for or competency to change these underlying conditions fell on partner organisations. As one interviewee put it:

It depends on the problem and non-police organisations are essential to many of the problems that we deal with. If we need to get to that underlying societal change, it’s not going to be undertaken by the police, so, you know, the interventions that we could put into play are just one part of that problem-solving equation. [F17: Respondent 1017]

Second, partners have extra resources, powers and knowledge that could be utilised to address problems as part of the problem-solving process. As one told us: ‘And they might actually have some resource, it might not even cost them anything, for example, it might just be changing the way they do their current things’ [F20: Respondent 1035]. Some participants described very close working relationships with partners – to the extent that in some forces, officers are physically embedded in multi-agency problem-solving teams. However, such close working was not always the experience of participants and where partnerships could not be established and lack of effectiveness partnership working acted as a barrier. As this interview participant stated: ‘The big challenge I have certainly at my level now is trying to encourage our partners to think in the same way. That is still a real, real issue’ [F18: Respondent 1020].

Organisational culture

The final key theme identified by interview participants concerns the police culture. Several participants drew attention to how the dominant police culture could act as a barrier to problem-oriented policing. They reported that problem-oriented policing was not seen by many officers as central to the core police task. Instead for interview participants: ‘problem solving is probably seen in areas, or certainly has been in the past, as a luxury, rather than a necessity’ [F18: Respondent 1021]. Indeed, according to our participants, the core police role continued to be understood by many in the police in terms of a pressure to respond swiftly to calls for service with the aim of enforcing the criminal law. As one interview participant put it: ‘our fundamental aim is really to protect life, gather evidence, get criminals to court and part of that is the evidential chain’ [F17: Respondent 1073]. Shifting from this emphasis was thought to be hard to achieve. One interviewee told us that, ‘I think it’s going to be a big cultural challenge to embed problem solving because we’ve never had it before and I think it’s getting people into that mindset of looking at things differently’ [F16: Respondent 1004].

Discussion

The starting point for this article was that there are good grounds for police organisations to endorse problem-oriented policing in an effort to improve their effectiveness in dealing with crime and other issues brought to them by the public. However, our study found that the implementation of problem-oriented policing in England and Wales in 2019 is patchy and halting. The process of problem-oriented policing has been referred to as ‘common sense’ or ‘not rocket science’ (see Read and Tilley Citation2000). However, evidence shows that the approach is technically difficult to accomplish, largely because of the skills required for the analysis and assessment stages and difficulties securing the partnership working which is often needed. It also stands in contrast to standard and well-established modes of police work which officers typically value. Notably, it stands in contrast to an emphasis on responding to incidents as they occur, on achieving fast-time results, and on the enforcement of the criminal law as the dominant mechanism of crime control (see also Goldstein Citation2003, Townsley et al. Citation2003). If problem-oriented policing – or indeed any other reform movement within policing – is to succeed, careful attention to the mechanisms through which it is implemented will be required. This reflects a wider body of work which, as stressed in the introduction, draws attention to the complexity of strategy implementation (Aaltonen and Ikävalko Citation2002, Atkinson Citation2006). The strategic planning literature indicates a number of problems in programme implementation. These include lack of commitment to the strategy, unawareness and misunderstanding of the strategy, unaligned organisational systems and resources, poor coordination and sharing of resources, inadequate capabilities, competing activities, and uncontrollable environmental factors (Aaltonen and Ikävalko Citation2002). In turn, our analysis of both survey and interview data draws attention to several barriers and facilitators of problem-oriented policing centred around the themes of leadership and governance, capacity, organisational structures and infrastructure, partnership working and organisational culture. Our analysis offers the following key findings, and hopefully useful insights into the conditions that need to be in place for problem-oriented policing to have a better chance of taking root and flourishing.

First is the importance of the patronage of key staff in the delivery of problem-solving (see also Scott Citation2006). Communication from leaders was judged especially important. Such communication includes articulating clearly the vision for the new strategy, the nature of new roles and responsibilities, and why the changes were necessary (see also Alexander Citation1985). The patronage of leaders (at different levels of the police organisation) also communicates important messages about the desired organisational direction and expectations of police personnel (see also Chan Citation2007). It communicates that the innovation is valued and reinforces any decisions to engage with the innovation over time. Equally, line managers were considered to play a similar role by reinforcing messages regarding the value of delivering problem-oriented policing. Middle managers may be especially important here as they are often responsible for disseminating information about a strategy and ensuring that the strategy is understood (Aaltonen and Ikävalko Citation2002). In this sense, managers could be considered ‘institutional entrepreneurs – taking on the difficult task of changing taken-for-granted cultural beliefs and values to help ensure that the innovation is perceived as legitimate inside and outside of the organization’ (Willis and Mastrofski Citation2011). Likewise, the presence of highly committed ‘champions’ and figure heads who are able to effectively communicate the virtues of problem-oriented policing and inspire (and support) officers and staff to implement and sustain the approach over time facilitates implementation (see also Read and Tilley Citation2000, Bullock et al. Citation2006).

Second, the provision of training and guidance, disseminating good practice, and rewarding problem-oriented policing are also considered to be important in the process of delivering problem-solving, as a way of raising awareness, persuading officers of the value of the approach and generating commitment. Establishing structures that orient the behaviour of officers towards problem-oriented policing was also judged important. This would include ensuring that evidence of delivering problem-oriented policing was required in supervision, annual appraisals, and promotion processes. Our analysis suggests that problem-oriented policing is sometimes incorporated into such systems but not always. Misalignment between novel organisational strategies and such systems of compensation has been identified as a notable barrier to implementation (Aaltonen and Ikävalko Citation2002).

Third, developing the infrastructure is likewise important in supporting the delivery of problem-oriented policing. This includes making available both specialist tools and teams to support implementation. Indeed, developing in-house expertise has been shown to support the implementation of strategic decisions involving new endeavours (Alexander Citation1985). Our analysis suggests, for example, establishing systems which can help officers map progress of problem-solving projects and making available analysts to support the SARA process can both support delivery. Whilst there is some evidence of police organisations adapting their infrastructure to accommodate and support problem-oriented policing, the infrastructure needed to support problem-oriented policing is not always present or is in its infancy, or commitment to it erodes over time.

Fourth, capacity shapes the delivery of problem-oriented policing. Indeed, available resources (Alexander Citation1985) and daily routines and a lack of time are regularly identified as reasons why novel strategies are not implemented (Aaltonen and Ikävalko Citation2002). Cuts to UK police budgets post-2010 reduced capacity to conduct problem-oriented policing because of cuts to community policing teams (see also Higgins Citation2018). This limited capacity may be compounded by the low status of community policing as a specialism within the organisation in the context of an organisational culture that values rapid response to calls for service and the enforcement of the criminal law. Relations with agencies other than the police are also important here. Partnership working was generally identified as an important facilitator of problem-oriented work but barriers to establishing strong interagency working relationships (generally a result of competing priorities and lack of capacity) were identified (see also Scott Citation2000, Braga Citation2002, Townsley Citation2003).

The analysis presented in this article gives clues to police leaders regarding what needs to be in place (or what needs to be absent) to implement problem-oriented policing. Drawing on our analysis (and the findings of other studies) we summarise these in .

Table 1. Barriers and facilitators of problem-solving.

Implementing problem-solving will require an enabling environment and a long-term vision and strategy from senior leaders within police organisations; the development of knowledgeable, skilled and motivated staff; and the creation of an infrastructure to support, manage and sustain effective problem-solving. It will, we believe, also require an ongoing commitment to further research directed at testing the effects of different conditions in which problem-oriented policing is introduced. Our analysis of the barriers to and facilitators of problem-oriented policing drew attention to certain knowledge gaps which would benefit from future study. Most notably research which is oriented towards determining the conditions necessary to cultivate, embed and advance problem-oriented ways of working is needed. We believe that there are several promising areas of future enquiry which emerge from this research. They include, first, generating a better understanding of how to effect culture change among police personnel and their partners to facilitate the acceptance and delivery of problem-solving as an organisational strategy. It is relatively easy to identify the structural changes that are needed for problem-solving to be applied more widely within policing. Yet it is not so easy to know how to produce the sort of cultural transformation that would be needed to maintain these changes in officer attitudes and behaviour. Research in this area would be welcome.

Second, research is needed to better understand how to ‘train’ problem-solvers. Our analysis identified the absence or inadequacy of training as a barrier to the delivery of problem-solving. Yet it is not so clear how to close the gap. The term ‘training’ may not even be entirely appropriate in relation to the needs of those involved in problem-solving. More than ‘training’ may thus be required to build and solidify the skills and knowledge needed to become an effective problem-solver. In other professions, a blend of book-learning, face-to-face instruction and on-the-ground mentoring and coaching from experienced practitioners is the norm. This is the case for doctors, accountants, lawyers, dentists, and nurses. Something akin to this may be needed for police problem-solving. The research evidence is largely silent on this topic. Furthermore, in this study, we found only a handful of innovative practices where web-based technologies were being drawn on to deliver problem-solving training. Systematic research trialling methods of inducting police personnel into problem-solving would help improve the evidence-base.

Third, research could usefully inform the development of a ‘good’ system for monitoring and recording problem-solving. It is generally acknowledged that tracking problem-solving is important both for accountability and for capturing transferable lessons that others can draw on. However, it is equally clear that many existing systems are deemed inadequate. Participants in this study suggested that current systems are often clunky, time-consuming, and the data they contained remained unused or underused. There would be clear benefits in finding a workable system that both supported and promoted problem-solving, which could be adopted across police forces. Presently, however, it is not known what a ‘good’ problem-solving recording system looks like. There is an important piece of work to do in reviewing existing systems and trialling one that builds on their strengths and tries to avoid their weaknesses, with a view to encouraging common adoption across police forces.

To conclude, delivering the conditions which sustain the delivery of problem-oriented policing – and related reform movements – together with addressing such knowledge gaps within the research literature will take time and sustained effort. But it is time and effort that will be needed if police organisations, and the communities they serve, are to benefit from the opportunities that investment in problem-solving is known to bring.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 College of Policing (2019). Neighbourhood policing guidelines. Supporting material for frontline officers, staff and volunteers.

References

- Aaltonen, P. and Ikävalko, H., 2002. Implementing strategies successfully. Integrated manufacturing systems, 13 (6), 415–418.

- Alexander, L.D., 1985. Successfully implementing strategic decisions. Long range planning, 18 (3), 91–97.

- Al Ghamdi, S.M., 1998. Obstacles to successful implementation of strategic decisions: the British experience. European business review, 98 (6), 322–327.

- Atkinson, H., 2006. Strategy implementation: a role for the balanced scorecard? Management decision, 44 (10), 1441–1460.

- Braga, A., 2002. Problem oriented policing and crime prevention. New York: Criminal Justice Press.

- Braun, V. and Clarke, V., 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative research in psychology, 3 (2), 77–101.

- Bullock, K., Erol, R., and Tilley, N., 2006. Problem-oriented policing and partnership. Cullompton: Willan Publishing.

- Chan, J., 2007. Making sense of police reform. Theoretical criminology, 11 (3), 323–345.

- Eck, J., 2019. Problem-oriented policing. In: D. Weisburd and A. A. Braga, eds. Police innovation: contrasting perspectives. Cambridge University Press, 165–181.

- Eck, J., and Spelman, W., 1987. Solving problems: problem-oriented policing in newport news. Washington: Police Executive Research Forum.

- Goldstein, H., 1979. Improving policing: a problem-oriented approach. Crime & delinquency, 25 (2), 236–258.

- Goldstein, H., 1990. Problem-oriented policing. New York: Mcgraw Hill.

- Goldstein, H., 2003. On further developing problem-oriented policing. In: J. Knutsson, ed. Problem-oriented policing: from innovation to mainstream. Crime prevention studies volume 15. Cullompton: Willan Publishing, 13–48.

- Goldstein, H., 2018. On problem-oriented policing: The Stockholm lecture. Crime science, 7 (13), 1–9.

- Higgins, A., 2018. The future of neighbourhood policing. London: Police Foundation.

- Hinkle, J.C., et al., 2020. Problem-oriented policing for reducing crime and disorder: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Campbell systematic reviews, 16 (2), e1089.

- Home Affairs Select Committee (HASC), 2018. Policing for the future inquiry. London: Home Affairs Select Committee.

- Kelling, G., et al., 1974. The Kansas city preventive patrol experiment: summary report. Washington, DC: The Police Foundation.

- Kirby, S., 2013. Police effectiveness: implementation in theory and practice. Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan.

- Kirby, S. and Keay, S., 2021. Improving intelligence analysis in policing. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Metcalf, B., 2001. The strategic integration of POP and performance management: a viable partnership? Policing and society, 11, 209–234.

- Pekkanen, P. and Niemi, P., 2013. Process performance improvements in justice organisations: pitfalls of performance measurement. International Journal of production economics, 143 (2), 605–611.

- Read, T. and Tilley, N., 2000. Not rocket science?: Problem-solving and crime reduction. Crime reduction research series paper 6. London: Home Office.

- Rosenbaum, D.P., 1986. Community crime prevention: does it work? Beverley Hills, CA: Sage Publications.

- Scott, M., 2000. Problem-oriented policing: reflections on the first 20 years. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, Office of Community Oriented Policing Services.

- Scott, M., 2006. Implementing crime prevention: lessons learned from problem-oriented policing projects. In: J. Knuttson and R. Clarke, eds. Putting theory to work: implementing situational crime prevention and problem-oriented policing. Crime prevention studies volume 20. Cullompton: Willan, 9–35.

- Scott, M. and Clarke, R., 2020. Problem-oriented policing: successful case studies. New York: Routledge.

- Seddon, J., 2008. Systems thinking in the public sector. Axminster: Triarchy Press.

- Sidebottom, A., et al., 2020. Problem-oriented policing in England and Wales 2019. Jill Dando Institute of Security and Crime Science, University College London.

- Skogan, W.G. and Frydl, K., 2004. Fairness and effectiveness in policing: the evidence. Committee to Review Research on Police Policy and Practices. Committee on Law and Justice, Division of Behavioural and Social Sciences and Education, National Research Council. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

- Spelman, W. and Brown, D.K., 1984. Calling the police: citizen reporting of serious crime. Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office.

- Thornton, A., et al., 2019. On the development and application of EMMIE: insights from the What Works Centre for Crime Reduction. Policing and society, 29 (3), 266–282.

- Townsley, M., Johnson, S., and Pease, K., 2003. Problem-orientation, problem-solving and organisational change. Crime prevention studies volume 15. Cullompton: Willan.

- Wandersman, A., 2009. Four keys to success (theory, implementation, evaluation and resources/system support): high hopes and challenges in participation. American journal of community psychology, 43 (1–2), 3–21.

- Weisburd, D., et al., 2008. The effects of problem-oriented policing on crime and disorder. Campbell systematic reviews, 4 (1), 1–87.

- Weisburd, D., et al., 2010. Is problem-oriented policing effective in reducing crime and disorder? Findings from a Campbell systematic review. Criminology & public policy, 9 (1), 139–172.

- Weisburd, D. and Eck, J.E., 2004. What can police do to reduce crime, disorder, and fear? The annals of the American academy of political and social science, 593 (1), 42–65.

- Willis, J.J. and Mastrofski, S.D., 2011. Innovations in policing: meanings, structures, and processes. Annual review of law and social science, 7, 309–334.