ABSTRACT

Police departments regularly conduct public opinion surveys to measure attitudes towards the police. The results of these surveys can be used to shape and evaluate policing policy and practice. Yet the extant evidence base is hampered when people use different methods and when there is no common data standard. In this paper we present a set of 13 core national indicators that can be used by police services across Canada to ensure measurement quality and draw proper comparisons between regions and over time. Having identified a set of 50 survey questions through an expert consultation process, we field those items on a quota sample of 2527 Canadians. Our analysis of the survey data has three stages. First, we use confirmatory factor analysis to assess scale properties. Second, we use substitution analysis to identify 13 single indicators that ‘best stand in’ for each scale. Third, we use the set of 50 and the sub-set of 13 measures to test procedural justice theory for the first time in the Canadian context. Overall, those commissioning and managing public attitudes surveys can use the 13 core indicators as a conceptually-rich and empirically-validated tool through which to understand local survey data in the context of other municipal, provincial, territorial and national contexts.

Police departments regularly conduct or commission public attitude surveys to measure the quality of their relationship with members of the public. It is important to do so, yet the evidence-base is often limited by the lack of an agreed upon set of core indicators that ensures measurement quality and comparability. Our focus in this paper is on Canada, and most Canadian policing jurisdictions currently field survey indicators that differ from those found in other jurisdictions in the country (Maslov, Citation2016). This makes it difficult to make proper comparisons across jurisdictions and track changes in attitudes over time. Surveys also tend to lack a common underlying explanatory framework driving what to measure and how to measure it. It is our contention that, if we are to develop an analytically powerful evidence-base that is comparable between regions and over time, then we need a common data standard that ensures not only empirical reliability and comparability, but also conceptual clarity and coverage.

We report on a study to develop a standardized, comprehensive and validated set of 13 core national indicators of public attitudes towards the police in Canada. An external consultation process recommended over 100 indicators that have been used in a variety of different national and international surveys. Fifty of these measures were then fielded in a quota online survey of 2527 Canadian respondents. Our analysis of the resulting data proceeds in three stages. We first use latent variable modelling to assess the empirical distinctiveness (convergent and discriminant validity) and scaling properties of the 50 measures. In the second stage of analysis, we assess which indicator works best on its own as a measure of each key construct (using substitution analysis). This allows us to identify a subset of 13 measures to form the recommended core indicators. In the final stage of analysis, we test procedural justice theory (PJT; Sunshine & Tyler, Citation2003; Tyler, Citation2006a, Citation2006b) in the Canadian context using the full set (50) of measures and the sub-set (13) of measures.

A few notes are warranted at the outset. Data for this study were collected as part of a wider project that inter alia sought to build a national consensus on indicators that would be relevant in the Canadian context, working in collaboration with existing national professional bodies and involving an expert consultation process. This means, in some instances, that the list of indicators for testing was influenced by this consultative process rather than developed strictly as a test of PJT. This was, to us, not only acceptable but also appropriate for the exercise, though it does impose some analytic limitations that are discussed below.

Relatedly, our paper provides an assessment of PJT in the Canadian context and demonstrates a method for distilling core indicators from a long-list of potential measures of trust and legitimacy in policing. The motivation is both empirical (to validate a set of indicators in the Canadian context) and practical (to provide a working ‘core’ survey that could be used in a wide range of communities, and especially where resources do not allow a more comprehensive examination of community attitudes). Thus, the paper is not only a test of PJT but also an exercise in defining a concise set of constructs for pragmatic application to a field – surveying public attitudes toward police in Canada – that is currently hindered by a lack of standard indicators (see also Maslov, Citation2016).

Our paper proceeds as follows. In the next section, we define current concepts within PJT. We then describe the methodology used to develop a set of 13 core national indicators designed to provide comprehensive conceptual coverage. On the basis of our analysis of the data, we then recommend these survey questions be used by police services across Canada and beyond.

Conceptual review

As social scientists, we routinely face the somewhat inconvenient fact that many of the things we seek to measure are not directly measurable. In the context of public attitudes towards the police, for instance, we cannot directly measure the extent to which an individual believes that ‘the police’ is a legitimate institution. Because of this, we typically look for answers to standardized survey items as indicators of presence or absence of this belief. This approach to the operationalization of unobservable psychological constructs means four things.

First, there is no right or wrong answer to the question ‘what is perceived police legitimacy?’ – answers to this question depend on conceptual, not empirical, analysis (Jackson & Bradford, Citation2019; Trinkner, Citation2019). Because we cannot directly measure whether someone believes that police have the right to power and authority to govern, there are no objective criteria to assess the validity of any given definition and measurement scheme. Second, and consequently, we need to set a clear and comprehensive conceptual position before developing an appropriate set of measures. In the current context, legitimacy (and other aspects of public attitudes towards the police) can be defined in different ways, indeed the past decade or so has seen several ‘stock-take’ articles concerning what legitimacy, trust and trustworthiness might variously mean in the context of the police and other legal authorities (e.g. Bottoms & Tankebe, Citation2012; Hamm et al. Citation2017; Hawdon, Citation2008; Jackson, Citation2018; Jackson & Gau, Citation2015; Trinkner, Citation2019; Tyler & Jackson, Citation2013; Bradford et al., Citation2018).

Third, different measures can be used to capture the same concept. Yet, when researchers take different approaches to measurement, comparability between studies is necessarily reduced. The goal of the current study is to develop a core set of indicators that can provide a comparative ‘backbone’ when placed within longer existing and/or new survey instruments.

Fourth, formative and reflective approaches to measurement can both be reasonably taken (for discussion in the context of public attitudes towards the police, see Jackson & Kuha, Citation2016). In this paper, we take a reflective approach to the measurement of trustworthiness, legitimacy and willingness to cooperate, which we take to imply the use of latent variable modelling to assess scaling properties and model relations between constructs. We model the relationship between variables and the underlying construct(s) of interest using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and then between constructs using structural equation modelling (SEM). We then recommend a set of single indicators based on a form of substitution analysis. We should note, at the threshold, that the use of these core national indicators is more in line with a formative approach to measurement, given that they use a set of single items, one for each construct.

In the rest of this section we define (a) police trustworthiness, (b) police legitimacy, and also (c) willingness to cooperate with the police. In the next section after this, we review the underlying explanatory framework motivating the current approach: namely, PJT.

What is perceived police trustworthiness?

We define perceived police trustworthiness as citizens’ positive or negative expectations regarding valued behaviours of officers under conditions of uncertainty. Examples of relevant measures of trust includeFootnote1:

‘Police treat citizens with respect’ (Reisig et al., Citation2007);

‘How often do the police make fair and impartial decisions in the cases they deal with?’ (Tyler & Jackson, Citation2014);

‘Do people in your neighbourhood provide better services to wealthy citizens?’ (Wolfe et al., Citation2016);

‘When people call the police for help, how quickly do they respond?’ (Sunshine & Tyler, Citation2003); and,

‘When people in my neighbourhood call the police, they come right away’ (Cao et al., Citation1996).

Such measures capture people’s perceptions of the capabilities and intentions of the police to do the things that they are trusted to do, in situations that sit between (to paraphrase Simmel, Citation1950, p. 318) knowledge and ignorance. They reference positive or negative expectations about the behaviour of the police as a collective actor; the intentions and capabilities of officers and organization in a general sense, i.e. the extent to which police behave in ways that enable trust. People cannot know for sure whether police officers always act fairly and effectively, and to believe that they do is to overcome uncertainty despite imperfect knowledge (Möllering, Citation2001).

But what is meant by ‘police’ in such survey items? There have been attempts to distinguish between public perceptions of different types of police organizations and between different levels within the institutional framework of policing – to separate out, for example, ‘global’ and ‘specific’ attitudes (Brandl et al., Citation1994). It might be surmised that perceived police trustworthiness, as described above, is more ‘specific’ in nature because it is most clearly seen in moments when people make themselves vulnerable to the behaviour of particular officers. Moreover, people may distinguish between different ‘types’ and ‘groups’ of police – they can, and do, trust ‘this’ officer, but not ‘that’ one, or ‘the police’ as a whole. But it is more parsimonious to suggest that when people form expectations and evaluations (which may crystalize in acceptance of vulnerability in relation to either specific officers, a police organization, or simply ‘the police’, see Hamm et al., Citation2017), they draw on perceptions and experiences that range across all three institutional levels.

Building on the results from the expert consultation process – specifically the range of different constructs and questions identified – and following on from prior work (Huq et al., Citation2017; Hamm et al., Citation2017; Tyler & Jackson, Citation2014; Jackson et al., Citation2013; Sunshine & Tyler, Citation2003; Tyler et al., Citation2015; Trinkner et al., Citation2018; Gerber et al., Citation2018), we define perceived police trustworthiness perceptions along five different dimensions. The first three relate to relational issues of fairness and shared interests. Procedural justice refers primarily to how police interact with, and make decisions regarding, citizens on a one-to-one (or few-to-one, or one-to-few) basis. Central here is the quality of interaction and decision-making across the dimensions of procedural justice: neutrality, voice, participation, respect, and so forth. When people feel demeaned or subjected to negative stereotypes, they view themselves as diminished as people and disrespected beyond what is appropriate when dealing with the law. Conversely, when officers treat people fairly and make objective decisions, their actions and demeanour help to affirm the dignity of individuals.

Second, engagement with the community refers to the extent to which people believe police listen to, understand and act on the concerns of the communities they serve; and thus, again, primarily relates to the intentions of police. This is, in many ways, a counterpart of the trustworthy motives component of procedural justice (Tyler, Citation1988, Citation1994), implying a one (police organization) to many (community members) relationship founded in principles of open communication, voice and respect. It is important to note, however, that police do have relationships with communities that are distinct from their relationships with individuals (Jonathan-Zamir et al. Citation2020). However, because community engagement is captured in surveys by interviewing individuals, who are left free to judge what ‘community’ means, we should expect a strong correlation between procedural justice and engagement, since respondents likely infer ‘community’ views from their own.

Third, distributive justice relates primarily to the fair allocation of scarce resources across aggregate social groups (although some have defined distributive justice as perceptions of individual-level outcome fairness, see Mclean Citation2020; Lind & Tyler, Citation1988; van den Bos et al., Citation1997). To put it another way, people ask themselves whether the benefits and impositions of policing are distributed in ways matched to underlying needs (e.g. victimisation) and behaviours (e.g. offending), or in ways premised on bias and/or discrimination. Because distributive justice refers to the appropriate allocation of the goods and burdens of policing across groups, it has a different meaning than procedural justice. But, again, distributive and procedural justice are likely to be highly correlated. On some accounts, perceptions of process fairness can be used as a way through which people judge distributive outcome fairness, which of course requires that they are separate aspects of people’s judgements while also being correlated with one another.

The fourth component of trustworthiness is bounded authority. Recent work has argued that people desire that police power to be exercised within certain boundaries and limits (Huq et al., Citation2017; Trinkner et al., Citation2018). There are places and situations where they wish police not to intrude, for example, and tools and tactics they think inappropriate (like the over-use of aggressive stop-and-frisk tactics in certain minority communities). When these boundaries are seen to be transgressed, people may question the legitimacy of the police in ways that transcend concerns over procedural and distributive fairness. Bounded authority is measured using survey questions like ‘How often do the police in your neighbourhood get involved in situations they have no right to be in?’ and ‘How often do the police in your neighbourhood exceed their authority?’

The fifth component of trustworthiness is effectiveness, which is typically measured using items like ‘How successful do you think the police are at preventing crimes where violence is used or threatened?’ and ‘How successful do you think the police are at catching people who commit house burglaries?’. This component references some outcome-related aspects of trust – the success of the police in securing the ends they are mandated to achieve. Another way of thinking about effectiveness is that it is, like distributive justice, more instrumental in nature, as opposed to the more relational procedural justice, community engagement and bounded authority components.

(b) What is perceived police legitimacy?

Yet, legitimacy is more than just the perceived appropriateness of an institution that means its possession of power is seen to be rightful. Police place demands on citizens with respect to obeying their instructions, accepting their decisions, authorizing them to enforce the law, and generally deferring to their activity. As Tyler & Trinkner (Citation2018, p. 3) state: ‘Perceptions of legitimacy … lead individuals to feel that it is their obligation to obey rules irrespective of their content. Hence people authorize legal authorities to decide what is correct and then people feel an obligation to adhere to the law.’Footnote2 On this account, the second component of legitimacy is an internalized sense of consent to (seen to be properly established) authority structures (Tyler Citation2006a, Citation2006b; for recent discussion see Bottoms & Tankebe, Citation2012; Tyler & Jackson, Citation2013; Trinkner, Citation2019; Posch et al., Citation2020). When one recognizes the authority of the police, one feels a normatively grounded obligation to obey officers’ instructions and the rules and directives operative within the social and physical space governed by police. To be considered a component part of legitimacy, ‘duty to obey’ should be characterised by truly free consent, in other words, as the willed acceptance of rules and instructions (Tyler & Jackson, Citation2013; Trinkner, Citation2019; Posch et al., Citation2020). Implicit here (and sometimes explicit, see Jackson et al., Citationin press; Huq et al., Citation2017; Van Damme et al., Citation2015) is the idea that institutional normativity grants the right to dictate appropriate behaviour, at least in certain circumstances. Believing that the police are behaving in the ‘right way’ activates a sense that one has a duty to also act in the ‘right way’ and, for example, follow their instructions (Tyler, Citation2006b; Trinkner, Citation2019).

As with perceived police trustworthiness, where or to whom or to what perceived police legitimacy attaches can be ambiguous. On some accounts, individuals are trusted while roles are legitimate, with the ‘office’ of police conferring legitimacy on individual officers, and legitimacy considered primarily an institutional attribute (e.g. Hawdon, Citation2008). As with trustworthiness, we recognise this underlying complexity, but we take the pragmatic approach that survey items referencing a generic, undefined, ‘police’ cover legitimacy at individual, organizational but especially institutional levels (it is the legitimacy of the institution that gives individuals and organisations power and authority).

(c) Willingness to cooperate with the police

Including willingness to cooperate with the police in the current study provides for a tangible outcome of perceived police trustworthiness and perceived police legitimacy, thereby helping to make these concepts both more ‘real’ and more relevant for policy-makers and others using survey data. One answer to the question often posed by sceptical police, and others, when confronted with the ideas of perceived police trustworthiness and perceived police legitimacy – ‘why should we care?’ – is that the police cannot fight crime or promote community safety alone. Public cooperation is central to effective and equitable day-to-day police work – an absence of cooperation impairs the efficiency of the police and erodes the fairness of their operations (Goudriaan et al., Citation2006; Jackson et al., Citation2020). There is also a good deal of evidence that people who see the police as trustworthy and legitimate are more likely to report crimes, give intelligence crucial to investigations, and so forth (Sunshine & Tyler, Citation2003; Jackson et al., Citation2013; Tyler & Jackson, Citation2014; Sifrer et al., Citation2015).

Procedurally just policing

In this paper, we identify a core set of national indicators of trustworthiness, legitimacy and willingness to cooperate for researchers to use in future work. It is important to state, however, that these indicators are also designed to be able to test PJT. Crucially, this explanatory framework allows one to test predictions about the relationships between trustworthiness, legitimacy and willingness to cooperate, and draw subsequent implications for policing policy and practice. As Jackson et al. (2021, p. 1) state: ‘According to procedural justice theory, legitimacy operates as part of a virtuous circle, whereby normatively appropriate police behavior encourages people to self-regulate, which then reduces the need for coercive forms of social control.’

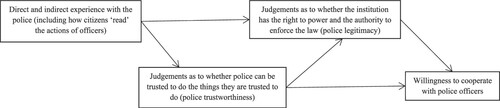

provides an overview of PJT, linking (i) people’s contact with the police, to (ii) whether they find the police to be trustworthy to engage with the community and act in fair, effective and restrained ways, to (iii) whether they view the police as legitimate holders of power with the moral authority to enforce the law and expect deference and obedience, to (iv) their willingness to report crimes and provide intelligence to the police.

As a popular theoretical approach to generating consensual rather than coercive relationships (Sunshine & Tyler, Citation2003; Tyler & Fagan, Citation2008; Tyler & Jackson, Citation2014), PJT makes four main predictions:

that the style of social interaction and the neutrality of decision-making in encounters between individuals and police are central to how such interactions are experienced and judged;

that social bonds between people and police are strengthened when officers make fair and neutral decisions, and when people are treated in ways that are recognised to be fair, respectful and legal, and not based on bias and stereotypes;

that these social bonds (shaped by procedural justice more than effectiveness or distributive justice) encourage a sense that police are legitimate – that the institution has the right to power and the authority to govern; and, the right to dictate appropriate behaviour, and is morally justified in expecting cooperation and compliance; and,

that legitimacy promotes normative modes of compliance and cooperation that are both more stable and more sustainable in the long run than policing based on deterrence, sanction and fear of punishment.

PJT is thus premised on the idea that procedurally fair policing builds legitimacy, and legitimacy enhances consent-based relationships between police and public. While scholars have explored the idea of procedural justice in the Canadian context (e.g. Livingston et al., Citation2014), conducted studies that draw on procedural justice theory to consider issues such as confidence in the police (e.g. Cao et al., Citation1996), and tested Tankebe’s (Citation2013) measurement model of legitimacy (e.g. Ewanation et al., Citation2019), we could find no study that has tested PJT in Canada (i.e. an assessment of whether procedural justice is the strongest predictor of legitimacy and examining the extent to which legitimacy predicts cooperation and/or compliance, adjusting for instrumental factors like police effectiveness and fear of crime).

As a starting point – subject to empirical validation below – we expect PJT to be relevant to understanding the establishment and maintenance of police legitimacy in Canada. Canadian policing is organized interdependently between federal, provincial/territorial, and municipal levels. Stand-alone municipal police services – of which there were 137 as of 2019, ranging in size from fewer than 10 officers to over 4700 – handle the majority (67%) of calls for service to police, with the remaining calls being handled by provincial police, First Nations police services, and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (which both acts as Canada’s federal police service and also provides contract police services to provincial, territorial and municipal areas that do not have stand-alone police services; see Conor et al., Citation2020). We should remain cognizant of several important characteristics that make the Canadian policing context unique – for example, that English-speaking Canada follows the common law tradition, while the province of Quebec has a civil code; and that policing in Canada requires navigating a substantial rural and remote policing environment that creates specific challenges for police and communities (Ruddell & Lithopoulos, Citation2016; Huey & Ricciardelli, Citation2015). Nonetheless, we should also recognize that Canadian policing broadly fits into the export of the Peelian police model to other ‘Anglo-American’ jurisdictions (e.g. Manning, Citation2005), and, as noted in the literature above, PJT has been a useful theoretical frame for understanding public attitudes toward the police in other similar contexts such as the UK, USA and continental Europe.

The study

Method

Sampling procedure

The survey fielded a set of 74 indicators (we focus in this paper on 50 of these) within a 10-minute online survey of 2527 quota sampled Canadians (500 Calgary area residents, 501 Ottawa area residents, 526 Halifax Regional Municipality residents, 500 residents in rural regions across Canada, and 500 French-speaking residents).Footnote3

Measures

Indicators were identified through an expert consultation processFootnote4 and included PJT items alongside a range of other measures not immediately relevant to our task here (for example, covering contact with police, ‘overall’ confidence, perceptions of crime and disorder etc.), as well as demographic variables. Multiple indicators of each PJT construct (50 measures in total) were fielded within this survey; this paper deals primarily with these items.

Many of the measures from the survey have been used in comparative cross-national surveys (chiefly using Round 5 of the European Social Survey, see Jackson et al., Citation2011 and Sifrer et al., Citation2015, and which was also fielded in the South African Social Attitudes Survey, e.g. Bradford et al., Citation2014, and Tyler & Jackson’s, Citation2014, US-based study) or in other established surveys such as the Canadian General Social Survey (e.g. O’Connor, Citation2008) and the London Metropolitan Police Public Attitudes Survey (e.g. Jackson et al., Citation2013). The survey fielded the following 50 measures to assess the constructs and respective PJT indicators described above:

We should note that the survey fielded only three measures of legitimacy. Two captured normative alignment and the third tapped into normative obligation to obey. When multiple indicators of each of the two components of legitimacy are fielded, studies typically find that they are empirically distinct and positively correlated (e.g. Bradford et al., Citation2014; Jackson et al., Citation2013). In the current study our hand was forced because (a) the need to keep the questionnaire short meant only a limited number of legitimacy measures were fielded, and (b) the selection of the PJT indicators was itself developed from a preliminary expert consultation exercise that drew input from academic and practitioner fields. The consultation exercise, on the one hand, limited the ability of the research team to build the indicators in linear fashion off of PJT (as the exercise did not a priori specify that indicators needed to draw on PJT, although perhaps unsurprisingly a majority of indicators suggested by experts were germane to it). On the other hand, by consulting with experts in the Canadian policing community before fielding the indicators, this exercise provided a valuable sense-check to ensure the overall approach remained relevant to practitioners in Canada.

Analytical strategy

Our analysis of the survey data has three stages. First, we test the measurement properties of indicators (of procedural justice, distributive justice, engagement, effectiveness, legitimacy and cooperation) using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to (a) assess the extent to which indicators of the various constructs load onto one underlying factor per construct (and thus can be treated as a psychometrically sound index), (b) assess the extent to which the various constructs are empirically distinct, and (c) test if it matters whether the survey was completed in English or French. We take a reflective approach to measurement: we assume that various aspects of perceived police trustworthiness, perceived police legitimacy and willingness to cooperate with the police are unobservable psychological constructs – the presence of which can be inferred by the effect they exert on what we can observe (in this case the way respondents answered the questions they were presented with). We treat the measures as imperfect indicators of the underlying concept that are subject to measurement error, assuming that (a) correlations between the measures are by virtue of them measuring the same underlying construct and (b) the variance not shared is measurement error. Note that we do not take a strong position on causality; we do not assume that the latent construct is causing variation in the various indicators. This means that we are relatively relaxed about the possibility that including other variables in the fitted models (e.g. socio-demographic indicators) could affect the measurement model parameter estimates.

Second, we draw empirically-informed recommendations for 13 core national indicators using the CFA and SEM results as benchmarks in a kind of substitution analysis. Specifically, we gauge how well each single item ‘stands in’ for the underlying latent variable (measured using multiple indicators) when pressure on the length of the survey is high. Conceptual issues are also taken into account when making recommendations for which single indicators to include in the set of core indicators (see below). Third, we test PJT using structural equation modelling (SEM) to estimate regression paths between latent constructs, thereby testing the theory for the first time in Canada.

Results

Step one: Assessing scaling properties using CFA

Results from a series of fitted CFA models using MPlus 7.2 are shown in (indicators were set as categorical and all latent constructs were allowed to covary). Each model also includes the single indicator of bounded authority, set to be correlated with the latent variables. The exact and approximate fit statistics suggest that the six-factor (M1) and the various five-factor models (M2a-M2d) fit the data adequately, at least according to the approximate fit statistics, where one typically looks for CFI >.95; TLI >.95; and RMSEA <.08 (see Hu & Bentler, Citation1999). The four-factor model combining procedural justice, distributive justice and engagement (M3), has a relatively poor approximate fit, at least when judged on the basis of RMSEA. The one-factor model fits the data the least well.

Table 1. Fit Statistics for Fitted CFA Models.

We take the view that the six-factor model is marginally better, although it is important to point out there is an extremely strong empirical overlap between procedural justice, distributive justice, community engagement and legitimacy. presents correlations between the latent variables estimated within the six-factor CFA model (including, in addition, the single indicator of bounded authority). We see especially strong bivariate associations between: (a) procedural justice and engagement (r = .90); (b) procedural justice and distributive justice (r = .88); (c) procedural justice and legitimacy (r = .88); (d) engagement and legitimacy (r = .85); (e) engagement and distributive justice (r = .84); and (f) engagement and effectiveness (r = .84).

Table 2. Correlations between Latent Constructs from the Six Factor CFA Model (Plus the Single Indicator of Bounded Authority).

We also note that in the six-factor model, factors loadings and R2s are all relatively high, indicating good scaling properties. For procedural justice, the standardized factor loadings range from .66 to .93, and the R2s range from .43 to .87. For engagement, the standardized factor loadings range from .85 to .87, and the R2s range from .72 to .76. For distributive justice, the standardized factor loadings range from .92 to .96, and the R2s range from .85 to .93. For effectiveness, the standardized factor loadings range from .72 to .84, and the R2s range from .52 to .70. For legitimacy, the standardized factor loadings range from .72 to .92, and the R2s range from .52 to .85. For willingness to cooperate, the standardized factor loadings range from .83 to .92, and the R2s range from .69 to .85. The appendix provides all the standardized factor loadings.

To assess the impact of the language of the survey, we fitted the six-factor CFA model for people who responded in English and for people who responded in French. The fit was good for both: for the English-language questionnaire (RMSEA .072 [90% CI .070, .073], CFI .982, TLI .979) and for the French-language questionnaire (RMSEA .064 [90% CI .061, .067], CFI .982, TLI .979). We also tested the model for respondents living in an urban area and respondents living in a rural area separately: the fit was good for urban respondents (RMSEA .071 [90% CI .069, .073], CFI .980, TLI .977) and for rural respondents (RMSEA .063 [90% CI .059, .067], CFI .987, TLI .985). This, combined with similar standardized factor loadings, suggests that it mattered little whether the survey was completed in English or French, or whether it involved urban or rural respondents.

Step two: extracting single indicators that ‘stand in’ for the various latent constructs

The next stage of analysis involves identifying a sub-set of the 50 measures that can be used as a harmonised set of indicators across Canada. To inform our recommendations, we use four criteria. The first is conceptual. For example, procedural justice is typically thought to have at least three aspects, namely fair treatment, fair decision-making, and voice provision. When deciding on what procedural justice items to include, we took this into account. The other three criteria are statistical/empirical:

factor loadings in each of the CFAs reported in and ;

substitution analysis in each of the CFAs (using a single indicator to predict a relevant latent construct); and,

substitution analysis in the predictors of each of the SEMs.

Our aim is to read across the above four criteria to determine the best items to represent the constructs of interest. This is, overall, a subjective exercise, in that it involves balancing a number of different things in order to make concrete recommendations.

Our approach to substitution analysis involves looking for the single indicator that is best placed to stand in for the full set of measures. To give a hypothetical example, say that we find a strong positive correlation between procedural justice and legitimacy from an SEM using multiple indicators for each construct. The standardised regression coefficient is .50. We rerun the SEM but this time use a single survey item to represent procedural justice. By cycling through each of the individual items included in the survey as measures of procedural justice, we assess which single item comes closest to .50. Imagine, also, that we find differences in procedural justice perceptions across ethnic groups. We use the same procedure, cycling through each of the procedural justice indicators, to assess which single item gives the most similar ethnic group differences.

Starting with procedural justice, we recommend inclusion of three items, partly because procedural justice is itself multi-dimensional, and partly to reflect the central importance of PJT in explaining overall trust and legitimacy. In terms of decision-making, there were two measures in the original question-set. We recommend ‘The police make decisions based on facts’ because the other decision-making measure (‘About how often would you say that the police in your neighbourhood make fair, impartial decisions in the cases they deal with?’) had the lowest factor loading in the CFA of procedural justice and the lowest regression coefficient when used as a single indicator of procedural justice predicting legitimacy (compared to the regression coefficient for procedural justice as a latent construct predicting legitimacy). To be sure, the other decision-making measure performed the best in terms of demographic substitution. Out of all the single indicators, the coefficients for the demographic indicators predicting this particular measure were closest to the coefficients for the demographic indicators predicting procedural justice as a latent construct. But ‘The police make decisions based on facts’ performed better on two out of three criteria.

The survey fielded a number of interpersonal treatment measures, as well as a few items that capture trustworthy motives (e.g. ‘The [police service] is an organization with integrity’, ‘The police know how to carry out their official duties properly’ and ‘The [police service] is an open and transparent organization’). We recommend the measure ‘The police treat people with respect’ on the basis that it did the best across all three statistical criteria. It had the second highest factor loading in the CFA of procedural justice and the second highest regression coefficient when used as a single indicator of procedural justice predicting legitimacy. It came ‘mid-table’ in terms of substitution and it also has the advantage of being a little more specific compared to, for instance, ‘The police treat people fairly.’ Research participants may interpret ‘fairly’ in a broader range of ways compared to ‘respect’, not least because respect is often seen as part of fairness.

In terms of distributive justice, we recommend ‘The police provide the same quality of service to all citizens.’ It had the highest factor loading in the CFA of distributive justice, the joint highest regression coefficient when used as a single indicator of distributive justice predicting legitimacy, and was joint first in terms of demographic substitution. ‘The police treat everyone fairly, regardless of who they are’ did well too. This would be a good alternative, although its focus on equal fair treatment could be seen as a strength (it is arguably more specific than ‘quality of service’) and a weakness (it refers to fair interpersonal treatment and decision-making, i.e. procedural justice, albeit in terms of equal allocation across groups in society).

On community engagement, we recommend either ‘The police are dealing with the things that matter to people in this community’ or ‘The police can be relied on to be there when you need them.’ If forced to make a choice, we would go with the first, since it more clearly relates to community preferences. But there is little in it. Both do well in terms of the factor loadings in the CFA of distributive justice, regression coefficients when used as a single indicator of distributive justice predicting legitimacy, and substitution.

To measure effectiveness, we recommend the following two indicators: ‘Responding quickly to calls for assistance’ and ‘Resolving crimes where violence is involved’. Both do well in terms of the factor loadings in the CFA of effectiveness and regression coefficients when used as a single indicator of effectiveness predicting legitimacy. In terms of substitution, ‘Responding quickly to calls for assistance’ performs less well. But in this instance we judge the performance on the other two criteria to be most diagnostic. It is worth noting that these two items relate to distinct aspects of the police ‘mission’ – dealing with crime and assisting people in need.

As mentioned earlier, when it comes to legitimacy, scholars typically differentiate between the normative appropriateness of an institution and the extent to which people feel a moral duty to obey the orders of actors that embody an institution. As such, we make the conceptual judgement that both dimensions should be represented in the core question set. There was only one measure of the second, ‘I feel a moral duty to follow police orders.’ There were two measures of the first dimension, and we recommend ‘I generally support how the police usually act’ because it did better than the other measure on the three statistical criteria.

Turning to cooperation with police, we recommend the following two measures: ‘I would call the police for assistance’ and ‘I would help the police if asked’. As with effectiveness, both do similarly well in terms of the factor loadings in the CFA of cooperation and regression coefficients when used as a single indicator of legitimacy predicting cooperation. In terms of substitution, ‘I would call the police for assistance’ performs less well, but we judge the performance on the other two criteria to be most diagnostic. Again, it is worth noting that even though both load on the same latent construct, which we label cooperation, these two items refer to somewhat different things – the first to assistance for the self, the second to a police-initiated call for assistance.

Step three: Testing procedural justice theory using path analysis

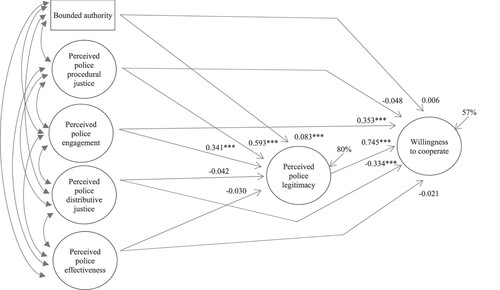

reports key findings from the fitted SEM that represents the first test of PJT in Canada. Note that, because we are analysing cross-sectional survey data, we are not inferring causal pathways. Starting at the right-hand side of the model, we found that just over half (57%) of the variation in cooperation can be explained by the other variables in the model. In particular, legitimacy is a strong predictor of cooperation (B = .745, p < .001), as is engagement (B = .353, p < .001) and distributive justice (B = −.334, p < .001).Footnote5 These findings indicate that a good deal of variation in cooperation can be explained by legitimacy and engagement: people who view the police as legitimate and who believe that officers engage with the community are likely to report being willing to cooperate with the police, compared to people who view the police as illegitimate and do not believe that officers engage with the community.

Turning to the predictors of legitimacy, we find that just over three-quarters (80%) of the variance of legitimacy is explained by the model. Procedural justice and engagement again emerge as important. Procedural justice is a strong and positive predictor of legitimacy (B = .59, p < .001) and engagement is a moderate and positive predictor of legitimacy (B = .34, p < .001). Of note is that bounded authority is a weak and positive predictor (B = .08, p < .001). It is reasonable to conclude from this that procedural justice and engagement could be strong normative expectations about how police officers should behave among the research participants; in other words, that when officers violate these norms about how they are supposed to behave, they risk losing legitimacy in the eyes of those they serve and protect (although, of course, the data are observational so we can say little that is meaningful regarding cause and effect). provides the bivariate correlations between the five constructs on the left-hand side of the model () and are (unsurprisingly) consistent with the correlations presented in .

Table 3. Correlations between Constructs from the Fitted SEM.

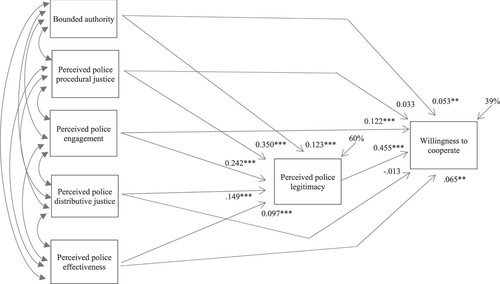

provides the findings from a path analysis model that uses single indicators rather than latent constructs.Footnote6 The findings are generally consistent with the structural equation modelling (), which we find reassuring. The similarity between the two models is further evidence that the substitution analysis was successful in identifying appropriate single item measures to represent the core constructs of interest.

Conclusions

Police departments in many parts of the world are increasingly interested in surveying the publics they serve. They can also be concerned with questions of procedural justice, public trust and institutional legitimacy. Yet problems are caused by conceptual fuzziness around these terms and the wide variety of survey items that have been used to measure them. Practically, this variety can be problematic for those tasked with designing and fielding local area surveys. Conceptually, it speaks to a lack of rigour in the existing academic and policy literature – in too many cases, constructs of interest have been inconsistently conceptualised and measured. One implication of this confusion is that it is difficult to compare across different studies and research sites. This can undermine our ability to properly explore what generates trust and legitimacy, and what outcomes a trusted and legitimate police organization might be able to secure.

We have in this paper described a method for selecting a core set of indicators that can be used in Canada and, we believe, further afield as well. By defining rigorous concepts of perceived police trustworthiness and perceived police legitimacy, and by drawing on the procedural justice literature, we sought to identify what might be the best single items to include in surveys measuring public opinions of the police. We were able to use the results from CFA and substitution analysis to identify single item indicators that best measure our core constructs of interest. Fielding these items in existing and future surveys would be a cost-effective solution to police departments seeking to gauge public opinion, since they cover a rich set of constructs with only a small number of measures, and has the added benefit of creating comparable cross-jurisdictional data where none previously existed (in Canada at least).

These core indicators were designed to be economical. Given that most survey companies effectively charge by the item, constructing a survey instrument that includes multiple items that collectively tap into the different aspects of the constructs outlined above can be expensive, particularly if the aim is to generate accurate estimates of opinion at low levels of geographic aggregation (where large surveys need to be fielded to many people). This is often the case within policing, as departments wish to know how opinion varies over the area they police. The aim was to provide a limited suite of measures that offers a good indication of the core constructs of interest, while also being cost effective, balancing accuracy in the estimation of public opinion against the expense of fielding surveys, and tying this process to a robust conceptualization of what, precisely, is being measured. Considering the Canadian policing context noted earlier – which includes police services of vastly differing sizes within several distinct regions across the country – creating a limited suite of questions tested across these populations should provide a tool of value to the range of police services found in the country. This, in turn, can allow police services and researchers in Canada to create comparative data between jurisdictions and, ultimately, at a national level, while also linking to international data where appropriate.

We have also shown the validity of developing measures according to a powerful explanatory framework, PJT, that (a) directs conceptual definitions; (b) allows police departments to field the measures in their own surveys to investigate what they need to do to legitimate themselves in the eyes of the communities they police; and (c) ensures the framework retains explanatory value within the multiple cultural and geographical contexts in Canadian society. This last consideration is particularly relevant given recent empirical developments in the application of PJT globally (see, for example, Saarikkomäki et al., Citation2020; Zahnow et al., Citation2019; Oberwittler & Roche, Citation2018; Akinlabi & Murphy, Citation2018; van Damme, Citation2017; Sifrer et al., Citation2015), which suggests that the conceptual model outlined above may not reflect all cultural contexts in which ‘the police’ (as organizations and individuals) operate (see Jackson, Citation2018, for a review of the international literature).

Using the full (50) set of measures and limited (13) set of measures, we found that procedural justice (treating people with respect and dignity, making decisions in fair, transparent and accountable ways, and allowing people voice) and legitimacy (right to power and authority to govern) explained a good deal of variation in people’s willingness to cooperate with the police. Consistent with existing research from the US, UK and Australia, this suggests that acting in procedurally just ways helps to generate the legitimacy that sustains and strengthens the ability of legal authorities to elicit public compliance and cooperation. There was, in addition, a novel finding in the current Canadian context. Bounded authority – the belief that the police respect the limits of their rightful authority – was less important in the current sample than it seems to be in the US and UK. What was more important was the belief that the police understand and respond to the needs of the local community. It seems, on this basis, that the police may be legitimated not only when they show that they wield their authority in fair and just ways, but also when they activity engage with the problems and needs of the local community.

Limitations and future research

Some limitations of the current study should, of course, be acknowledged. First, our study was not based on a nationally representative sample and our findings only pertain to the Canadian context. It is for future work to see how things would pan out in other national settings, preferably using more ambitious sampling approaches. Second, and relatedly, Canadian policing occurs in a breadth of contexts (only some of which could be captured in this study’s sampling approach), so it will be important to continue to monitor the validity and utility of these indicators as they are incorporated into Canadian public attitude surveys in diverse, large and small, urban and rural, and French and English, communities. Third, the survey was designed within a multi-year, consultative and collaborative process involving several Canadian policing and public safety institutions; this means that the study was not solely intended to be a test of PJT, and this introduced some methodological limitations around indicator selection that have been discussed earlier in the paper.

Fourth, our analysis included several techniques to ensure that these indicators captured perceptions of diverse racial, gender, and age groups, and some studies have found that PJT’s predictions are particularly strongly supported in marginalized communities of color (Hofer et al., Citation2020; Madon et al., Citation2017; Quinn et al., Citation2019). Nonetheless, there is still much work to be done to bridge PJT research with wider concerns regarding structural or systemic racism in policing. To date, PJT research has rarely (if ever) addressed people’s perceptions of structural racism in policing. This is surprising for a number of reasons, but one of them is that procedural justice is about the fairness of methods to achieve outcomes (Thibaut & Walker, Citation1975), so racism embedded in unfair process will (almost by definition) produce racism embedded in unfair outcomes. We thus recommend that future work addresses the possibility that procedural injustice reflects and exacerbates racist injustice in policing (see e.g. Geller et al., Citation2014; Tyler et al., Citation2014). It may be problematic to focus solely on respectful treatment and unbiased decision-making: as Knowles et al. (Citation2009, p. 857) argue, institutions that privilege procedural justice principles may perpetuate a form of ‘color-blind ideology’ that is consistent with the status quo of racial subjugation.

Final words

Police services in different locations can have differing priorities regarding the aspects of public attitudes and perceptions on which they wish to conduct surveys. Many will already have established survey processes in place that they would be unwilling to entirely replace, but most of those that already conduct public attitude surveys would be able to include – and benefit from – this small set of core indicators that, if integrated within existing survey processes, could provide comparable data with other jurisdictions provincially/territorially and nationally. This would allow researchers, communities and police services to understand local survey data in the context of other municipal, provincial/territorial and national data. It will also ensure that they measure the most relevant aspects of public attitudes toward police, allowing researchers to test an explanatory framework (PJT) on how they might turn coercive police-citizen relations into consensual police-citizen relations.

We should note that, in an ideal world, multiple indicators would be used to measure each construct – this will always be preferable from a measurement perspective. Recognising that we do not live in an ideal world, the current study offers a way for those commissioning and managing public attitude surveys to focus on those items that are more important for gaining a rounded understanding of procedural justice, trust and legitimacy. Naturally, there is nothing stopping police agencies from incorporating these indicators into a wider survey that includes multiple indicators for each construct (and/or measuring other perceptions and attitudes not related to PJT); but, for those without the resources to field extensive surveys, this set of core indicators provides a theoretically-informed and empirically-validated tool that measures what appear to be important aspects of public attitudes towards police services in a democratic society.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 These questions have alternately been called ‘trustworthiness’, e.g. Huq et al., Citation2017, also ‘trust’, e.g. Flexon et al., Citation2009; ‘public attitudes towards the police’, e.g. Cavanagh et al., Citation2020; ‘confidence’, e.g. Cao et al., Citation1996; ‘satisfaction’, e.g. Reisig & Parks, Citation2000; ‘legal cynicism’, e.g. Kirk & Papachristos, Citation2011; and ‘police legitimacy’, e.g. Ewanation et al., Citation2019.

2 See Trinkner (Citation2019) for a discussion on whether Tyler (Citation2006a, Citation2006b) specifies duty to obey as downstream to legitimacy or constituent of legitimacy.

3 The online panel was drawn from a respondent panel maintained by a Canadian research firm (Logit Group) and designed to generally fit the census demographic parameters for each geographic region.

4 In brief, the consultation process involved, first, asking a panel of experts (both academic experts and researchers within policing organizations with experience fielding public attitude surveys) to identify questions they believed were the most important questions to include in public attitude surveys. This yielded over 100 unique questions, which were then sorted according to theoretical relevance, conceptual closeness (between indicators, and in alignment with theory) and prior empirical validation (for more information on the consultation, see Giacomantonio et al., Citation2019).

5 The negative partial association between distributive justice and cooperation requires comment. This can happen when explanatory variables are highly correlated with each other and the outcome variable. ‘Collinearity’ refers to the situation in which one explanatory variable is strongly correlated with another explanatory variable; ‘multi-collinearity’ refers to the situation in which one predictor variable can be linearly predicted by a combination of other predictor variables with a good deal of accuracy. To investigate, we ran the model again, but this time with just distributive justice predicting cooperation (B = .49, p < .001). We then added procedural justice as a second predictor of cooperation (B = .84, p < .001) alongside distributive justice (B = −.25, p < .001). Note the sign-switch. Distributive justice was a positive predictor without procedural justice in the regression model, but negative with procedural justice in the regression model. This is because distributive justice is strongly correlated with procedural justice (r = .88 in this particular model). In such an instance, it can be a little artificial to think about the effect on the expected outcome of a unit increase in one construct (here distributive justice) holding constant the other construct (here procedural justice). At any fixed value of procedural justice, there is not much variation in distributive justice, making it hard to tease out partial correlations with any accuracy. We therefore recommend caution when interpreting the estimated negative relationship between distributive justice and cooperation in .

6 The measures used were: ‘about how often would you say that the police in your neighbourhood exceed their authority’ (bounded authority), ‘the police treat people with respect’ (procedural justice), ‘the police are dealing with the things that matter to people in this community’ (engagement), ‘the police provide the same quality of service to all citizens’, ‘how effective are the police at resolving crimes where violence is involved?’ (effectiveness), ‘I generally support how the police usually act’ (legitimacy) and ‘I would help the police if asked’ (cooperation).

References

- Akinlabi, O.M., and Murphy, K., 2018. Dull compulsion or perceived legitimacy? Assessing why people comply with the law in Nigeria. Police practice and research, 19 (2), 186–201.

- Baćak, V. and Apel, R., 2019. The thin blue line of health: police contact and wellbeing in Europe. Social Science & medicine. 267, 112404.

- Baier, A., 1986. Trust and antitrust. Ethics, 96, 231–260.

- Barber, B., 1983. The logic and limits of trust. Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

- Bauer, P.C., 2014. Conceptualizing and measuring trust and trustworthiness. Political concepts: Committee on concepts and methods working paper series, 61, 1–27.

- Bottoms, A., and Tankebe, J., 2012. Beyond procedural justice: A dialogic approach to legitimacy in criminal justice. Journal of Criminal Law and criminology, 102, 101–150.

- Bradford, B., et al., 2014. What price fairness when security is at stake? police legitimacy in South Africa. Regulation and governance, 8 (2), 246–268.

- Bradford, B., Jackson, J., and Hough, M., 2018. Trust in justice. In: E. Uslaner, ed. The Oxford handbook of social and political trust. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 633–653.

- Bradford, B., Jackson, J., and Stanko, E.A., 2009. Contact and confidence: Revisiting the impact of public encounters with the police. Policing & society, 19 (1), 20–46.

- Brandl, S.G., et al., 1994. Global and specific attitudes toward the police: disentangling the relationship. Justice quarterly, 11 (1), 119–134.

- Cao, L., Frank, J., and Cullen, F.T., 1996. Race, community context and confidence in the police. American Journal of police, 15, 3–22.

- Cavanagh, C., Dalzell, E., and Cauffman, E., 2020. Documentation status, neighborhood disorder, and attitudes toward police and courts among latina immigrants. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 26 (1), 121–131.

- Colquitt, J.A., Scott, B.A., and LePine, J.A., 2007. Trust, trustworthiness, and trust propensity: A meta-analytic test of their unique relationships with risk taking and job performance. Journal of applied psychology, 92, 909–927.

- Conor, P., et al. 2020. Police resources in Canada, 2019. Statistics Canada.

- Ewanation, L., et al., 2019. Validating the police legitimacy scale with a Canadian sample. Canadian Journal of Criminology and Criminal justice, 61 (4), 1–23.

- Flexon, J.L., Lurigio, A.J., and Greenleaf, R.G., 2009. Exploring the dimensions of trust in the police among Chicago juveniles. Journal of Criminal justice, 37, 180–189.

- Gambetta, D., 1988. Trust: making and breaking cooperative relations. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

- Geller, A., et al., 2014. Aggressive policing and the mental health of young urban men. American journal of public health, 104 (12), 2321–2327.

- Gerber, M.M., et al., 2018. On the justification of intergroup violence: The roles of procedural justice, police legitimacy and group identity in attitudes towards violence among indigenous people. Psychology of violence, 8 (3), 379–389.

- Giacomantonio, C., et al. 2019. Developing a common data standard for measuring attitudes toward the police in Canada. Public Safety Canada, Research Report 2019–R003.

- Goudriaan, H., Wittebrood, K., and Nieuwbeerta, P., 2006. Neighbourhood characteristics and reporting crime. British Journal of criminology, 46, 719–742.

- Hamm, J.A., Trinkner, R., and Carr, J.D., 2017. Fair process, trust, and cooperation: moving toward an integrated framework of police legitimacy. Criminal justice & behavior, 44, 1183–1212.

- Hardin, R., 2006. Trust and trustworthiness. New York: Russel Sage Foundation.

- Hawdon, J., 2008. Legitimacy, trust, social capital, and policing styles: A theoretical statement. Police quarterly, 11, 182–201.

- Hofer, M.S., Womack, S.R., and Wilson, M.N., 2020. An examination of the influence of procedurally just strategies on legal cynicism among urban youth experiencing police contact. Journal of Community psychology, 48 (1), 104–123.

- Hu, L.T., and Bentler, P.M., 1999. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural equation modeling: A multidisciplinary journal, 6 (1), 1–55.

- Huey, L., and Ricciardelli, R., 2015. ‘This isn’t what I signed up for’ when police officer role expectations conflict with the realities of general duty police work in remote communities. International Journal of Police science & management, 17 (3), 194–203.

- Huq, A., Jackson, J., and Trinkner, R., 2017. Legitimating practices: Revisiting the predicates of police legitimacy. British Journal of criminology, 57 (5), 1101–1122.

- Jackson, J., et al., 2011. Developing European indicators of trust in justice. European Journal of criminology, 8 (4), 267–285.

- Jackson, J., et al., 2012. Why do people comply with the law? legitimacy and the influence of legal institutions. British Journal of criminology, 52 (6), 1051–1071.

- Jackson, J., et al., 2013. Just authority? trust in the police in england and wales. Routledge.

- Jackson, J., 2018. Norms, normativity and the legitimacy of legal authorities: international perspectives. Annual Review of Law and social science, 14, 145–165.

- Jackson, J., et al., 2020. Police legitimacy and the norm to cooperate: using a mixed effects location-scale model to estimate social norms at a small spatial scale. Journal of Quantitative criminology, Advance online publication. doi:10.1007/s10940-020-09467-5.

- Jackson, J., and Bradford, B., 2010. Measuring public confidence in the police: Is the PSA23 target fit for purpose? Policing: A Journal of Policy and practice, 4 (3), 241–248.

- Jackson, J., and Bradford, B., 2019. Blurring the distinction between empirical and normative legitimacy? A methodological commentary on “police legitimacy and citizen cooperation in China”. Asian Journal of criminology, 14 (4), 265–289.

- Jackson, J., and Gau, J., 2015. Carving up concepts? differentiating between trust and legitimacy in public attitudes towards legal authority. In: E. Shockley, T. M. S. Neal, L. PytlikZillig, and B. Bornstein, ed. Interdisciplinary perspectives on trust: towards theoretical and methodological integration. London: Springer, 49–69.

- Jackson, J., et al., in press. Fear and legitimacy in Sao paulo, Brazil: police-citizen relations in a high violence, high fear context. Law & Society review.

- Jackson, J., and Kuha, J., 2016. How theory guides measurement: public attitudes toward crime and policing. In: T. S. Bynum, and B. M. Huebner, ed. Handbook on measurement issues in criminology and criminal justice. London: John Wylie, 377–415.

- Jonathan-Zamir, T., Perry, G., and Weisburd, D., 2020. Illuminating the concept of community (group)-level procedural justice: A qualitative analysis of protestors’ group-level experiences With the police. Criminal justice and behavior, Online First 28 December 2020.

- Kirk, D.S., and Papachristos, A.V., 2011. Cultural mechanisms and the persistence of neighborhood violence. American Journal of sociology, 116 (4), 1190–1233.

- Knowles, E.D., et al., 2009. On the malleability of ideology: motivated construals of color blindness. Journal of Personality and Social psychology, 96 (4), 857–869.

- Lind, E. and Tyler, T., 1988. The social psychology of procedural justice. New York: Plenum Press.

- Livingston, J.D., et al., 2014. What influences perceptions of procedural justice among people with mental illness regarding their interactions with the police? Community mental health journal, 50 (3), 281–287.

- Madon, N.S., Murphy, K., and Sargeant, E., 2017. Promoting police legitimacy among disengaged minority groups: does procedural justice matter more? Criminology & Criminal justice, 17 (5), 624–642.

- Manning, P.K., 2005. The study of policing. Police quarterly, 8 (1), 23–43.

- Maslov, A. 2016. Measuring the performance of the police: The perspective of the public. Public Safety Canada, Research Report 2015–R034.

- Mayer, R.C., Davis, J.H., and Schoorman, F.D., 1995. An integrative model of organizational trust. Academy of Management review, 20, 709–734.

- McLean, K., 2020. Revisiting the role of distributive justice in Tyler’s legitimacy theory. Journal of Experimental criminology, 16, 335–346.

- Möllering, G., 2001. The nature of trust: from Georg Simmel to a theory of expectation, interpretation and suspension. Sociology, 35 (2), 403–420.

- Oberwittler, D. and Roché, S. (Eds.). 2018. Police-citizen relations across the world: comparing sources and contexts of trust and legitimacy. New York: Routledge.

- O'Connor, C.D., 2008. Citizen attitudes toward the police in Canada. Policing: An international Journal of Police strategies & management, 31 (4), 578–595.

- Oliveira, T.R., et al., 2020. Are trustworthiness and legitimacy “hard to win, easy to lose”? A longitudinal test of the asymmetry thesis of police-citizen contact. Journal of Quantitative criminology, Advance online publication. doi:10.1007/s10940-020-09478-2.

- Peyton, K., Sierra-Arévalo, M., and Rand, D.G., 2019. A field experiment on community policing and police legitimacy. Proceedings of the national Academy of sciences, 116 (40), 19894–19898.

- Posch, K., et al., 2020. “Truly free consent”? Clarifying the nature of police legitimacy using causal mediation analysis. Journal of Experimental criminology, Advance online publication. doi:10.1007/s11292-020-09426-x.

- Quinn, C.R., Hope, E.C., and Cryer-Coupet, Q.R., 2019. Neighborhood cohesion and procedural justice in policing among Black adults: The moderating role of cultural race-related stress. Journal of Community psychology, 48 (1), 124–141.

- Reisig, M.D., Bratton, J., and Gertz, M.G., 2007. The construct validity and refinement of process-based policing measures. Criminal justice and behavior, 34, 1005–1027.

- Reisig, M.D., and Parks, R.B., 2000. Experience, quality of life, and neighborhood context: A hierarchical analysis of satisfaction with police. Justice quarterly, 17, 607–630.

- Ruddell, R. and Lithopoulos, S., 2016. Policing rural Canada. In: J. Donnermeyer, ed. The routledge international handbook of rural criminology. New York: Routledge, 399–408.

- Saarikkomäki, E., et al. 2020. Suspected or protected? Perceptions of procedural justice in ethnic minority youth's descriptions of police relations. Advance online publication. Policing and Society.

- Šifrer, J., Meško, G., and Bren, M., 2015. Assessing validity of different legitimacy constructs applying structural equation modeling. In: G. Meško and J. Tankebe, ed. Trust and legitimacy in criminal justice. London: Springer, 161–187.

- Simmel, G., 1950. The secret and the secret society. In: K. H. Wolff, ed. The sociology of Georg simmel. London: The Free Press of Glencoe.

- Skogan, W.G., 2006. Asymmetry in the impact of encounters with the police. Policing & society, 16, 99–126.

- Sunshine, J., and Tyler, T.R., 2003. The role of procedural justice and legitimacy in public support for policing. Law and Society review, 37, 513–548.

- Tankebe, J., 2013. Viewing things differently: The dimensions of public perceptions of legitimacy. Criminology, 51, 103–135.

- Thibaut, J. and Walker, L., 1975. Procedural justice: A psychological analysis. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Trinkner, R., 2019. Clarifying the contours of the police legitimacy measurement debate: A response to Cao and graham. Asian Journal of criminology, 14 (4), 309–335.

- Trinkner, R., Jackson, J., and Tyler, T.R., 2018. Bounded authority: expanding “appropriate” police behavior beyond procedural justice. Law and human behavior, 42 (3), 280–293.

- Tyler, T.R., 1988. What is procedural justice? criteria used by citizens to assess the fairness of legal procedures. Law & Society review, 22, 103–135.

- Tyler, T.R., 1994. Psychological models of the justice motive. Journal of Personality and Social psychology, 67, 850–863.

- Tyler, T.R., 2006a. Why people obey the law. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Tyler, T.R., 2006b. Psychological perspectives on legitimacy and legitimation. Annual Review of psychology, 57, 375–400.

- Tyler, T.R., and Fagan, J., 2008. Why do people cooperate with the police? Ohio state Journal of Criminal Law, 6, 231–275.

- Tyler, T.R., Fagan, J., and Geller, A., 2014. Street stops and police legitimacy: teachable moments in young urban men's legal socialization. Journal of Empirical Legal studies, 11 (4), 751–785.

- Tyler, T.R. and Jackson, J., 2013. Future challenges in the study of legitimacy and criminal justice. In: J. Tankebe and A. Liebling, ed. Legitimacy and criminal justice: An international exploration. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 83–104.

- Tyler, T.R., and Jackson, J., 2014. Popular legitimacy and the exercise of legal authority: motivating compliance, cooperation and engagement. Psychology, Public Policy & Law, 20 (1), 78–95.

- Tyler, T.R., Jackson, J., and Mentovich, A., 2015. On the consequences of being a target of suspicion: potential pitfalls of proactive police contact. Journal of Empirical Legal studies, 12 (4), 602–636.

- Tyler, T.R. and Trinkner, R., 2018. Why children follow rules: legal socialization and the development of legitimacy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Van Damme, A., 2017. The impact of police contact on trust and police legitimacy in Belgium. Policing and society, 27 (2), 205–228.

- Van Damme, A., Pauwels, L., and Svensson, R., 2015. Why do Swedes cooperate with the police? A SEM analysis of Tyler’s procedural justice model. European Journal of Criminal Policy research, 21 (1), 15–33.

- van den Bos, K., et al., 1997. How do I judge my outcome when I do not know the outcome of others? The psychology of the fair process effect. Journal of Personality & social psychology, 72 (5), 1034-1046.

- Wolfe, S.E., et al., 2016. Is the effect of procedural justice on police legitimacy invariant? Testing the generality of procedural justice and competing antecedents of legitimacy. Journal of Quantitative criminology, 32 (2), 253–282.

- Zahnow, R., Mazerolle, L., and Pang, A. 2019. Do individual differences matter in the way people view policel? A partial replication and extension of invariance thesis. Advance online publication. Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice.

Appendix

The goal of this study was to identify a set of core national survey indicators to harmonise future research into public attitudes toward the police in Canada (and that can also be used in other countries to facilitate cross-national comparison). In this appendix we summarise 4 police-citizen contact questions then the proposed 13 core indicators.

We recommend measuring police-initiated and citizen-initiated contact using the following questions:.

In the past 2 years, did the police approach you, stop you or make contact with you for any reason?

How dissatisfied or satisfied were you with the way the police treated you the last time this happened?

In the past 2 years, have you approached or contacted the police for any reason?

How dissatisfied or satisfied were you with the way the police treated you the last time this happened?

It is important to ask about both types of contact, in part because research suggests that negatively-experienced police-initiated contact may have a stronger negative effect on trust and legitimacy compared to negatively-experienced citizen-initiated contact (Skogan, Citation2006; Bradford et al., Citation2009; Oliveira et al., Citation2020; see also Baćak & Apel, Citation2019).

We also recommend the following two ‘headline’ public confidence in the police indicators. While these have not been discussed in any detail above, we are broadly convinced by the argument that easy to understand global measures are useful for policy-makers and others – our decision here is therefore practical as much as conceptual. These items could be examined in further work which can explore the extent to which specific components of trustworthiness predict global confidence (see Jackson & Bradford, Citation2010, who found, using a London-based sample, that trust in fairness and engagement was very strongly correlated with overall trust and confidence):

5. Taking everything into account, how good a job do you think the police in this area are doing?

6. Taking everything into account, how good a job do you think the police in this country are doing?

These two items have the additional benefit of allowing a clear and easy distinction between local and national police.

In addition to the above, we recommend the following indicators:

7. Procedural justice: the police make decisions based on facts.

8. Procedural justice: the police treat people with respect.

9. Distributive justice: the police provide the same quality of service to all citizens.

10. Community engagement: the police are dealing with the things that matter to people in this community.

11. Bounded authority: about how often would you say that the police in your neighbourhood exceed their authority?

12. Effectiveness: responding quickly to calls for assistance; resolving crimes where violence is involved.

13. Effectiveness: resolving crimes where violence is involved.

14. Legitimacy: I feel a moral duty to follow police order.

15. Legitimacy: I generally support how the police usually act.

16. Cooperation: I would call the police for assistance.

17. Cooperation: I would help the police if asked.