ABSTRACT

Human Trafficking (HT) has serious social and economic implications for both society and the victims of the crime. Despite being one of the most complex crimes to detect and investigate, multi-agency collaboration can often underpin effective investigations. There remains, however, a scarce evidence-based knowledge concerning the investigation of HT and police collaboration with partner agencies. The present study examines police collaborations in England and Wales when investigating HT, providing empirical knowledge on (i) the types of support police officers usually require from other agencies when investigating HT crimes; (ii) the agencies with whom they usually collaborate; and (iii) the types of support agencies can provide. The study uses the Repertory Grid Technique to gather and analyse data from 28 investigators from nineteen police units in England and Wales investigating trafficking crimes. Data from the individual grids was analysed through content and descriptive analysis. A median grid was created and analysed through principal component analysis and hierarchical cluster analysis. The study identified that police officers need to collaborate with partner agencies when working with victims, planning and assisting police operations/strategies, building the criminal intelligence picture and obtaining information about premises/companies and individuals. Findings also reveal that the police believe they need to rely upon several key agencies for each category of support. Findings evidence the need for police collaboration with partner agencies to secure victim-centred and intelligence-led investigations.

Introduction

Criminological understanding of human trafficking is known to be limited, not least due to its clandestine nature. Such concealment of offending and victimisation also inhibits accurate understanding of its scope. For example, while the UK government, using multiple systems estimations (see Silverman Citation2014), has claimed that the number of exploited victims is in the region of 10-13,000, other sources argue it is at least ten-fold that number (Walk Free Citation2018). Moreover, additional to its hidden characteristics, other factors create challenges for explanation and its policing. That is, most crimes that are officially recorded are generated by victim complaints or by witness reports to the police. In contrast, trafficked victims do not readily report (or even recognise) their own status to the authorities, such as the police. Relatedly, offenders are known to go to great lengths in organising their activities in such a way that victims are not easily visible to either potential witnesses or indeed the police themselves (Decker Citation2015). In light of the foregoing, it is perhaps then not surprising that researchers, practitioners, and policymakers each characterise human trafficking (HT) as a highly complex crime to both detect and investigate (Van der Watt and Van der Westhuizen Citation2017). The diversity of actors that may be involved in the process, the lack of victims reporting their victimisation, or the paucity of resources and intelligence, are among many other factors that contribute to make its criminal investigation so challenging (Dandurand Citation2017; IOM Citation2018; OSCE Citation2010). Despite operational responses and the investigation of HT crimes being largely conducted by the police, it is well recognised through research, policy and practice that collaborating with other agencies is beneficial, if not essential, when undertaking such criminal investigations (Duijn et al. Citation2015; Farrell et al. Citation2014; HMICFRS Citation2017; Huff-Corzine et al. Citation2017; Kirby and Nailer Citation2013). Indeed, research findings on human trafficking investigations indicate that when collaborating with other agencies, not only are the number of arrests, prosecutions and convictions higher, but it has also been found that the safeguarding of victims is promoted and improved (David Citation2007; Farrell et al. Citation2008; Gerassi et al. Citation2017; Matos et al. Citation2019).

Recent research examining the investigation process of HT crimes in England and Wales identified that establishing multi-agency collaborations was recognised by a cohort of substantially experienced HT law enforcement professionals as a core investigative action to be undertaken during the course of an investigation because of the opportunities that it offers to share intelligence, capabilities, and resources (Pajόn and Walsh Citation2020). Furthermore, such understanding is not confined solely to the British context. That is, police collaborations with other partner agencies are also common practices when investigating HT crimes in the USA (Clawson et al. Citation2008; Farrell et al. Citation2008; Wilson and Dalton Citation2008). For instance, Clawson et al. (Citation2008) found that almost all of 289 police investigations in their study involved collaboration with other law enforcement agencies or local authorities, with just over half of these involving NGOs. Farrell et al. (Citation2008) and Wilson and Dalton (Citation2008) each found that such collaborations became critical to securing the prosecution of offenders and the safeguarding of victims. There remains, however, a scarce evidence base concerning the criminal investigation of HT. Thus, the present study aims to further develop research to expand the current body of knowledge, that thus far has tended to have been dominated by legal and policy frameworks. As a result, much less research has been conducted concerning what occurs in criminal investigations of HT cases (Friesendorf Citation2009; Russell Citation2018). As such, our knowledge is merely partial, somewhat dependent on anecdotal evidence as to what is ‘good practice’, but, consequently, less underpinned by empirical evidence concerning what works when investigating HT (Malloch et al. Citation2012).

Not unlike the global drugs trade, HT involves the transit of commodities (i.e. people) from their origins to destinations (where their services are required by consumers). The UK is well known as one of the foremost destination countries (Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons Citation2020). Its government has responded to the problem with key legislation (i.e. The Modern Slavery Act 2015), which in theory, would make the prosecution of offenders less demanding. Yet, recent official figures (UK Annual Report on Modern Slavery Citation2020) continue to show that prosecutions of offenders in this country hover annually around 200–300 and that the number of victims formally identified is around 10,000, both figures believed to represent a fraction of the real numbers involved. In order to improve the UK’s law enforcement responses to HT, key investigative guidance, such as the Government’s Modern Slavery strategy (HM Government Citation2014) and the UK’s College of Policing (Citation2019), encourage investigators to collaborate with partner agencies during HT investigations. Indeed multi-agency collaborations and intelligence-led approaches to the investigation of HT have both received support as the foundations of, what has been termed as, ‘best’ practices (e.g. Anti-Trafficking Monitoring Group Citation2018; GRETA Citation2016; Hyland Citation2016). At the same time, though, the official police ‘watchdog’ in England and Wales found uneven practical application by the police of these two elements during their criminal investigations of HT (HMICFRS Citation2017).

Police collaborations with partner agencies when responding to complex crimes is not a new concept in the criminal justice response. Instead, police are increasingly networking and collaborating with non-police agencies and other law enforcement agencies to respond to security problems that cross the roles and responsibilities of multiple agencies and organisations (Fischer et al. Citation2017; L’Hoiry Citation2021). Although police involvement in different multi-agency security networks is usually associated with prevention, police are increasingly involved in more reactive efforts, such as forming joint investigation teams, including when undertaking both international and transnational investigations (Block Citation2008; Severns et al. Citation2020). Agreement exists on the benefits of networking and collaborations to overcome the limitations of single agencies and organisations when tackling a complex problem, therefore, securing a more effective response. Some of the most commonly identified benefits are (i) the opportunities for intelligence sharing, thereby increasing the quality and usefulness of data; (ii) better mapping of the problem; (iii) improved decision making; and (iv) joint problem-solving approach (Fischer et al. Citation2017; Fox and Butler Citation2004; Gerassi et al. Citation2017). When responding to trafficking crimes, multi-agency cooperation has also been found to promote victims’ safeguarding (David Citation2007; Gerassi et al. Citation2017; Matos et al. Citation2019). Research has found that multi-agency teams help to better assess the psychological, social, emotional and economic needs of the victims and therefore tailor responses accordingly (Matos et al. Citation2019). As Farrell et al. (Citation2008) found, police forces involved in multi-agency collaborations were more likely to provide support to victims during an investigation.

Despite agreements on the benefits of networking and collaborations, the implementation of networks in practice differs widely. Security networks are dynamic, many emerging organically from professional contacts and initiatives (Foot Citation2015; O’Leary and Vij Citation2012). Differences, therefore, exist in the type and intensity of the relationships among the members of the network, the purpose of the collaboration, models of governance and structures (Huff-Corzine et al. Citation2017; Lagon Citation2015; Schorrock et al. Citation2019; Whelan and Dupont Citation2017). The term ‘security networks’ is used to refer to existing relationships between agencies across the security field that cooperate to achieve a common goal (Whelan, Citation2017). When working together, such connections and approaches can be represented in a continuum of cooperation, coordination, and collaboration (Whelan, Citation2017). Cooperation, on one end, involves more sporadic instances of ties between agencies, such as agencies working together for a specific case. On the other end, collaboration refers to agencies working together to achieve shared goals and objectives in a more formalised structure (Keast et al. Citation2007; Whelan, Citation2017). For example, the Multi-Agency Safeguarding Hubs (MASH) or the Multi-Agency Risk Assessment Conference (MARAC) are well established multi-agency hubs in England and Wales to respond to cases of child exploitation and domestic violence, respectively, where different stakeholders together share intelligence, risk assesses the threat for individual cases, and plan and coordinate an operational response tailored to each case (Crockett et al. Citation2013; Robbins et al. Citation2014). Yet, regardless of the structure followed, many academics have argued that the nature of the relationships (and interpersonal trust) among members may matter more than the resources and structure itself.

Flexible networking approaches can allow for some scope of negotiations among partners around organisational boundaries and discretionary judgement calls on information sharing (Fischer et al. Citation2017; Schorrock et al. Citation2019). Thereby facilitating the cooperation towards a mutual benefit. Nonetheless, previous research on security networks and partnership has also identified that lack of clarity on roles and reasonability of members, blurry or uncommon objectives and unfamiliarity with partners’ needs, expertise, and priorities can all impact relationship and trust-building, therefore hinder the collaboration (Dandurand Citation2017; Fischer et al. Citation2017). In HT investigations, it has been broadly found that collaborating with other agencies can become challenging in practice (e.g. Farrell et al. Citation2008; Harvey et al. Citation2015). Difficulties have been found to emerge from both legal perspectives (i.e. sharing of sensitive, restricted and privileged information) and practical ones (e.g. trust, working practices) (Huisman and Kleemans Citation2014).

One key challenge of agencies when addressing complex problems ‘is how to combine effectively the contributions of different knowledgeable and competent actors towards a clear understanding of the problems and generate professional confidence in delivering interventions’ (Crawford and L’Hoiry, Citation2017, p.637). When forming networks and collaborations to respond to complex crimes, questions are often raised about which agencies should be involved, for what purpose and how they should be involved (McManus and Boulton Citation2020). Indeed, one of the recurring issues concerning multi-agency collaborations in HT investigations in the UK is the lack of agreement among the police concerning (i) the agencies with whom police officers need to collaborate; and (ii) the type of support required (and able to be offered) from those agencies (HMICFRS Citation2017; IASC and University of Nottingham Citation2017). Such a lack of concordance may be explained by both the absence of a standardised approach towards collaboration and the various previous experiences of police officers working with partner agencies. As prior research suggests, police officers would identify opportunities for collaboration with agencies based on their past professional experiences and informal contacts (Farrell et al. Citation2008; Gerassi et al. Citation2017; Wilson and Dalton Citation2008). Gerassi et al. (Citation2017) found that it was often not until agencies worked together in HT investigations that they became aware of their respective competencies/capabilities. Similarly, opportunities for collaboration have been found to be often created due to either informal networks, previous relationships or previous successful collaborations with various agencies (Farrell et al. Citation2008; Gerassi et al. Citation2017; Wilson and Dalton Citation2008).

Such practical knowledge police officers have in identifying potential opportunities for collaboration, based on their previous experiences and contacts (Gerassi et al. Citation2017; Wilson and Dalton Citation2008), would be classified as tacit knowledge (Ambrosini and Bowman Citation2001; Taylor et al. Citation2013). Tacit knowledge is characterised as being ‘intuitive, experience-based, inexplicit, and non-systematised’ (Holgersson and Gottschalk Citation2008, p.367). While some argue that tacit knowledge reflects police expertise and capacity for problem-solving (Taylor et al. Citation2013), it is also context-specific. That is to say that the individual’s quality of experience may well affect their assessment of that experience (Ambrosini and Bowman Citation2001; Björklund Citation2008). For example, as Gerassi et al. (Citation2017) observed, adverse experiences or tensions between agencies might also problematise future collaborations. Consequently, such previous experiences (and police views on particular partner agencies) may well explain the lack of consensus among UK police concerning multi-agency collaboration when investigating trafficking crimes (HM Crown Prosecution Service Inspectorate Citation2017; HMICFRS Citation2017). However, such a situation clearly leaves the investigation of HT premised more on happenstance and much less on a broader evidence-based knowledge of what works. Therefore, the current study will examine and provide insight into multi-agency collaborations when investigating HT in England and Wales by gathering the collective police officers’ tacit knowledge on multi-agency collaboration when investigating trafficking crimes.

The present study aims to better understand police collaborations with different partner agencies when investigating suspected HT crimes by providing empirical knowledge concerning police officers’ beliefs as to (i) the areas of investigation where police forces need to collaborate with partner agencies; and (ii) those agencies which are most capable of providing different types of support. Thus, the study has three main objectives. First, to identify what type of support is needed from other agencies. Second, to identify the agencies with whom police officers usually collaborate, and third, to gain empirical insight into how police officers view the capabilities of different agencies to provide certain types of support. Because of the exploratory nature of the study, no hypotheses were created.

Methodology

Participants

A purposive sampling technique was used to select the participants. After gaining ethics authorisation from the authors’ University Faculty Research Ethics Committee, the researchers contacted those police forces with whom they had previous contacts. Then, through snowballing, further police officers from other forces were asked to participate in the study. Twenty-two of the 43 police forces in England and Wales were contacted, with 28 police officers agreeing to participate from 19 forces. All participants were deployed in HT criminal investigation units. They held different police ranks (i.e. Detective Constable [n = 10], Detective Sergeant [n = 9], Detective Inspector [n = 7], Detective Chief Inspector [n = 1], Detective Superintendent [n = 1]). Other than four interviews conducted over the phone (due to geographical distance), the interviews were conducted face-to-face at the premises of each of the police forces during 2019-2020. Interviews lasted an hour and a half on average.

Data collection

The Repertory Grid Technique (RGT) was the interviewing method used for data collection. Unlike standard interview techniques, the RGT has been recognised as more suitable in empirically gathering and analysing tacit knowledge (Ambrosini and Bowman Citation2001; Björklund Citation2008). Kelly (Citation1955) developed the technique under the basis of personal construct theory. As such, the RGT is designed to gather the interviewee’s own understanding of the experience, capturing how individuals perceive and make sense of their reality (Fransella et al. Citation2004). The RGT involves minimal input from the interviewer (Fallman and Waterworth Citation2010; Rogers and Ryals Citation2007), thus minimising typical limitations associated with research interviewing such as interviewer bias or interviewees providing socially desirable responses. The RGT consists of three main components being (i) ‘Elements’, which define the specific subjects of inquiry; (ii) ‘Constructs’, which are the ways the individual groups and differentiates between elements; and (iii) ‘Linkage’, relating to how each element is considered and described based on each construct (Easterby-Smith Citation1980; Fransella et al. Citation2004; Rogers and Ryals Citation2007; Tan and Hunter Citation2002).

Individual grids were created from each of the research participants’ responses, reflecting the research aims and objectives. That is, (i) the agencies they collaborate with (i.e. elements); (ii) the types of support they require (i.e. constructs); and (iii) the views of police officers concerning how capable an agency is to provide each specific type of support (i.e. linkage). Each interview followed the same steps. For each interview, we first asked participants to think about an example of human trafficking investigation, based on their previous professional experiences of investigating trafficking cases, and to name any of the agencies with whom they may collaborate. Next, our interviewees were asked to say what support those agencies could provide. Finally, participants were asked to rate on an ascending five-point scale how capable each of those agencies was in providing such stated support (where 1 = not at all capable, and 5 = fully capable).

Data analysis

As participants used different names to refer to the same type of support, a single code was used to refer to all those names with the same meaning (e.g. ‘translation’, ‘interpreter’, ‘language translation’, ‘language support’, which were all coded as ‘language support’). Inter-rater reliability of the various codes was tested using Cohen’s Kappa. An independent raterFootnote1 coded all the statements mentioned by eight participants (selected randomly), finding strong levels of agreement, Kappa = .83 (p < .001) (Cohen Citation1998). The content analysis found patterns and themes emerging in the interviews, which were then grouped into five categories reflecting the main types of support police officers commonly need from other agencies. An independent raterFootnote2 grouped all elicited constructs into the five main categories of support, also finding a strong level of agreement, Kappa = .80 (p < .001) (Cohen Citation1998). The content analysis of the constructs was complemented by a descriptive analysis (i.e. frequencies and percentages of (i) the number of constructs included in each of the five categories; (ii) the total number of constructs mentioned per category; (iii) the number of participants who referred to each category; and (iv) the number of constructs each participant mentioned for each of the five categories). Next, descriptive analysis was also conducted for the elements (i.e. agencies), identifying the number of participants who mentioned each agency.

Development and analysis of a median grid

A median grid was constructed from aggregating the data found commonly in the individual grids (Curtis et al. Citation2008). That is, the seven elements mentioned by more than 80% of the sample were included in the common grid. Then the 13 individual grids that mentioned those seven elements were included in the common grid. The RepPlus programme was used to analyse the median grid data (Gains and Shaw Citation2018) using two different tools: PrinGrid and Focus Cluster. The former applies Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to the data, creating a graphic plot that represents relationships between elements and constructs. Based on the spatial proximity between elements and constructs, it is possible to explore relationships between and among elements and constructs. That is, the distance between and among elements and constructs suggests how they might relate to each other (the strongest relationships being between those elements and constructs which are at a closer distance) (Curtis et al. Citation2008; Gains and Shaw Citation2018; Hodgkinson et al. Citation2017). Focus cluster, meanwhile, applies hierarchical cluster data analysis to identify the strongest associations between both elements and constructs (Easterby-Smith Citation1980). The tool creates a new grid where elements and constructs are reordered according to their similarity. Whenever the programme calculates a reversal of constructs poles that would improve the results, the programme will reverse the construct (Gains and Shaw Citation2018). Thus, the interpretation of the results should not be based on the values within the grid, but rather on the clusters of both elements and constructs that the programme creates (as stated, based on their similarity) (Björklund Citation2008; Gains and Shaw Citation2018). The programme also creates dendrograms to graphically represent found similarities (Gains and Shaw Citation2018).

Results

Types of support

From the 28 interviews, a total of 483 individual constructs were mentioned. After using the same nomenclature, they were reduced to 39 constructs. Participants mentioned between 7 and 31 different constructs (M = 17.25; SD = 6.14). Following content analysis, they were grouped into these five categories:

Working with victims

Obtaining information about premises and companies

Obtaining information about the individuals

Building the criminal intelligence picture

Planning and assisting police operations/strategies

shows the constructs gathered within each category, reflecting the different types of support mentioned by the participants. While three of the categories refer to intelligence gathering/sharing, three main differences were found: (i) intelligence concerning properties and companies; (ii) intelligence specific for individuals, both victims and offenders; and (iii) intelligence regarding the offence and the criminal picture. The other category referred to by participants was Working with victims, reflecting different aspects such as securing basic support needs or engaging with victims. The final category identified was Planning and assisting police operations/strategies that would include aspects such as using powers, capabilities and resources from other agencies.

Table 1. Categories of Support and Individual Constructs.

The descriptive analysis of the categories and constructs is presented in . Planning and assisting police operations/strategies was found to be the category that gathered the largest number of constructs. When examining the total number of individual constructs mentioned, over half were gathered in either the Planning and assisting police operations/strategies or the Working with victims categories. All participants mentioned at least one construct from the following categories: Working with victims, Building the criminal intelligence picture, and Planning and assisting police operations/strategies (and all but one mentioned at least one construct from Obtaining information about individuals). Twenty-two out of the 28 participants mentioned at least one construct from the Obtaining information about premises and companies category.

Table 2. Descriptive Analysis of the Categories of Support.

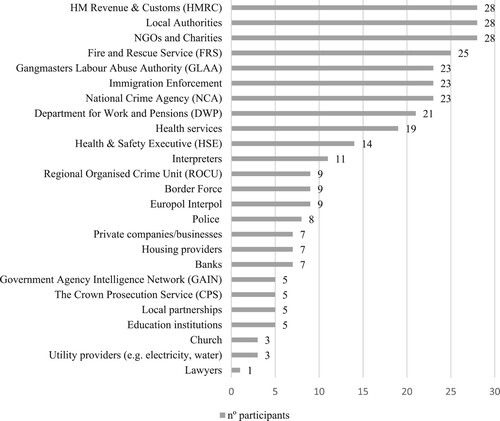

Partner agencies

The second aim was to identify the agencies the police forces usually collaborate with. The participants mentioned between six and 18 different agencies (M = 11.26, S.D. = 2.75). shows the agencies mentioned by participants and how many participants mentioned each agency. From the 25 agencies identified, seven were cited by more than 80% of the interviewees. They are:

HM Revenue and Customs (HMRC) – the UK Government agency responsible for the administration of individuals’ and company taxes, as well as monitoring that employers pay at least the UK’s national minimum wage.

Local Authorities – Local government agencies with devolved powers, being responsible for governmental administration at a local level across the UK

Non/Governmental Organisations (NGOs)-Charities (e.g. Red Cross)

Fire and Rescue Service (FRS) – the UK equivalent of the Fire Department in the USA

Gangmaster and Labour Abuse Authority (GLAA) – The central UK Government agency responsible for the monitoring and investigation of labour exploitation

Immigration Enforcement – The central UK Government agency responsible for the enforcing immigration law in the UK

National Crime Agency (NCA). – The central UK agency responsible for developing national intelligence on criminal activity such as human trafficking

Figure 1. Descriptive Analysis for Agencies. Note: See Appendix 1 for explanation of the following organisations: HMRC, Local authorities, GLAA, Immigration Enforcement, NCA, DWP, Health services, HSE, ROCU, Border force, GAIN and CPS.

Participants used the nomenclature charity and Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs) interchangeably. Thus, the nomenclature NGOs-Charities was used to refer to both. Despite participants recognising that Local Authorities comprise of many departments with different functions, areas of responsibility and capabilities, they specifically referred to the enforcement powers Trading StandardsFootnote3 has compared to the rest of the departments.

Findings from the median grid

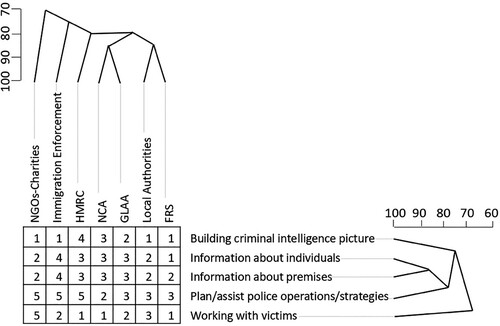

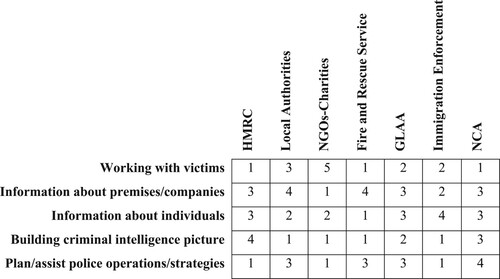

To understand how police officers view the different agencies as capable or not of providing specific categories of support, a median grid was created from those thirteen participants who mentioned HMRC, Local Authorities, NGOs-Charities, FRS, GLAA, Immigration and enforcement, and NCA (see ).

Figure 2. Median Grid Showing Participants’ Views on the Capability of each Agency to Provide each Type of Support. Note: Rate on an ascending five-point scale (where 1 = not at all capable, and 5 = fully capable).

From examining interviewees’ ratings of the support these agencies could provide, it was found that most of the agencies (n = 5) received scores of 3 or above in more than one category of support, indicating that participants viewed most agencies as capable to provide support in more than one category. Only NGOs-Charities attracted a score of ‘5’ for the category Working with victims and ‘1’ for the rest of the categories (with the exception of Obtaining information about individuals scoring as ‘2’), which reflects officers’ views of NGOs-Charities as fully, and mainly, capable of providing support in the category for Working with victims. Similar to NGOs-Charities, Immigration Enforcement also had only one high score of ‘4’ for the category of Information about individuals, the rest of the categories being scored either ‘1’ or ‘2’.

Data also suggest that police officers use more than one agency for each category of support. As can be observed, all categories present at least two agencies rated as ‘3’ or higher. That was the case even for the category of Working with victims. Other than NGOs-charities, police officers also seem to rely on Local Authorities to provide support in that category. It was also found that the categories in which police forces seem to collaborate with more agencies are Obtaining information about individuals and Obtaining information about premises/companies. For both categories, only one agency attracted a score of ‘1’. As results reveal, only Fire and Rescue Service is viewed as incapable of providing support in Obtaining information about individuals, and only NGOs-charities are viewed as incapable of providing support in Obtaining information about premises and companies.

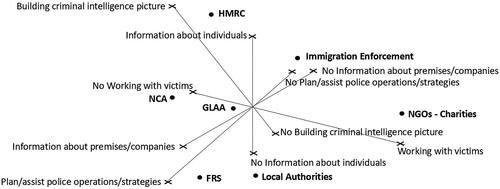

The PrinGrid identifies the constructs attributed to each element by looking at the spatial proximity between elements and constructs (Easterby-Smith Citation1980) (see ). Looking at the spatial proximity, the strongest relationships were found to be between agencies and those categories of support that each of these agencies were reckoned incapable of providing. Specifically, results indicate that participants view Immigration Enforcement as neither very capable of Planning and assisting operation/strategies nor of Providing information about premises and companies. Similarly, Local Authorities are seen as not very capable of Providing information about individuals, and NCA as not very capable of Working with victims. Thus, the PrinGrid reflects the consensual views of police officers concerning what support certain agencies are unable to provide. Nevertheless, the graphical representation also reveals links (albeit weaker) between (i) HMRC and the categories of Building the criminal intelligence picture and providing Information about individuals; between (ii) Fire and Rescue Service and the category Planning and assisting operation/strategies; as well as, between (iii) NGOs and Working with victims.

Finally, the dendrogram represented in found levels of similarity among agencies and among categories of support. Strong resemblance (86%) was found for the categories Obtaining information about individuals and Obtaining information about premises/companies. In contrast, Working with victims is the category with the least similarity to any other category of support. When examining the agencies, two clusters can be differentiated, NCA-GLAA (85% resemblance) and Local Authorities-FRS (85% resemblance). Similar to the previous analysis of the raw data of the median grid, the focus cluster analysis indicates that NGOs-charities has the lowest score of similarity with the rest of the agencies. That is, police officers would consider NGOs-charities as the agency least similar to the rest (considering the type of support they are capable of providing).

Discussion

Conducting multi-agency collaboration is considered as a cornerstone strategy to promote intelligence sharing, victims’ safeguarding and enforcement of human trafficking laws (Farrell et al. Citation2014; Huff-Corzine et al. Citation2017; Pajόn and Walsh Citation2020). However, the prior literature has found disagreement exists among police officers both regarding the support needed and also the agencies with whom they collaborate. The lack of previous networking with other agencies and the deficits in understanding what each agency can offer and whom to contact to support the investigation, together create difficulties for a swift and effective implementation of multi-agency collaborations. The current study aimed to minimise such a gap of understanding by providing empirical insight on

the types of support police officers usually require from other agencies when investigating HT crimes;

the agencies they usually collaborate with; and

the kind of support agencies are capable of providing according to police officers’ views.

Types of support police officers need from other agencies when investigating human trafficking crimes

Victim-centred and intelligence-led investigations, and proactive and disruptive approaches are all recognised as effective investigative practices for HT police investigations (David Citation2007; Gallagher and Holmes Citation2008; Matos et al. Citation2019). The findings from the present study demonstrate that to secure such ends, police officers need support from different agencies in five main categories of support, namely: Working with victims, Obtaining information about premises and companies, Obtaining information about individuals, Building the criminal intelligence picture, and Planning and assisting police operations/strategies.

The Working with victims category reflects that different types of support are needed in order to achieve a victim-centred approach. Our findings suggest that police officers need to collaborate with agencies, such as NGOs, to both ensure the safeguarding of victims and promote victims’ engagement in the criminal justice system. Securing the safeguarding of victims of trafficking during the criminal investigation process greater ensures that their basic needs are considered, helping support victims’ rehabilitation and reintegration into society (United States Department of State Citation2005). This is a requirement in any HT police investigation (UNODC Citation2009; Council Directive Citation2011/Citation36/EU). Furthermore, victims’ collaboration in the criminal justice process is considered a critical success factor in securing prosecutions due to the amount of evidence and information they can provide (Clawson et al. Citation2008; David Citation2008). However, limitations on victims’ engagement are also well-recognised, being (for example) one of the most significant challenges faced by investigators due to the reluctance of many victims to assist the police. Victims’ unawareness of their own victimisation, fear of retaliation to themselves and their families or the mistrust of many victims towards the police (due to possible erroneous perceptions based on stereotypes or previous experiences with the police), are some of the reasons why victims do not easily engage with the police (Andrevski et al. Citation2013; Cockbain and Brayley-Morris Citation2018; Farrell et al. Citation2008; Sheldon-Sherman Citation2012). Also, victims of trafficking can abscond or withdraw from the criminal justice process at any given time (Gallagher and Holmes Citation2008; Farrell et al. Citation2008). Furthermore, their credibility can, in many cases, be undermined during the court procedure (Brunovskis and Skilbrei Citation2016; David Citation2008; Farrell et al. Citation2014; McGaha and Evans Citation2009). As a result, proactive and intelligence-led investigations are considered more effective than victim-led investigations (Farrell et al. Citation2014; Matos et al. Citation2019).

Pajόn and Walsh (Citation2020) found that Intelligence gathering and sharing are core investigative actions in HT investigations. However, gathering intelligence and evidence on suspected HT offences is a challenging task (United States Department of State Citation2019; HMICFRS Citation2017). The UNODC (Citation2006, p. xx) argues that HT is ‘in fact better understood as a collection of crimes bundled together rather than a single offence; a criminal process rather than a criminal event’. Hence, lines of enquiry and intelligence gathering must focus on all elements relevant to prove the offence (IOM Citation2018), such as the means, the act (i.e. recruitment, transportation and exploitation) and the purpose. Findings from the present study identified the three main categories of information necessary to ensure an intelligence-led approach and that require police collaboration with other agencies. They are: Obtaining information about premises and companies, Obtaining information about individuals, and Building the criminal intelligence picture.

The category Obtaining information about premises/companies reflects the need for police officers to gather information on companies and properties where, despite being legally registered, exploitation may be taking place. Criminals will use such legitimate companies and registered properties to commit HT crimes (OSCE Citation2010). Thus, there is a need to collaborate with other agencies that can have access to relevant information. Previous research has also found how traffickers are able to recruit and exploit multiple victims by working through networks to maximise profits and minimise risks (Campana Citation2016; OSCE Citation2010). Such networks involve different offenders, each of them having different roles and operating at different levels, from facilitators to main exploiters (Campana Citation2016; OSCE Citation2010; Salt Citation2000). The category Building the criminal intelligence picture not only reflects the need to gather information from other law enforcement agencies concerning aspects such as the modus operandi and criminal networks, but it also acknowledges that HT crimes are, in many cases, committed alongside other offences such as immigration offences, fraudulent document offences, or financial crimes (Bouche et al. Citation2016; Farrell et al. Citation2008). Gathering financial information was a theme that emerged in the present study within the category Building the criminal intelligence picture. Human trafficking is recognised to be an economically motivated crime (Belser Citation2005; HM Government Citation2019; OSCE Citation2010, Citation2014). Leman and Janssens (Citation2008) argue that HT can be better understood as a business model where profit is gained by first exploiting victims and then committing a financial crime. Hence, conducting financial investigations to evidence the economic profit of the offence has been found to be successful in securing prosecutions (UNODC Citation2006) and also disrupting criminal activity (OSCE Citation2014). Findings from the present study suggest that police forces need to collaborate with those other agencies who may have relevant information to evidence the monetary gain, such as HMRC, which, among others, possesses intelligence and have the powers to investigate tax frauds and other financial crimes. Finally, Obtaining information about individuals will reflect the need to gather information on both victims and offenders from different agencies and sources.

HT police investigations must focus not only on the prosecution of the offenders, but also on the safeguarding of victims and the disruption of the crime (Bjelland Citation2020). Furthermore, in many cases, proactive strategies such as surveillance or undercover strategies will be necessary to both gather intelligence and prove the offence (Farrell et al. Citation2008). In order to secure a proactive and disruptive approach, police officers need to use different sources of powers, capabilities and resources (David Citation2007), which, as data suggest, will need to be provided by other agencies. Following international recommendations on adopting a multi-agency approach that not only relies on police powers and capabilities, but also on the collaboration with different agencies (United States Department of State Citation2019; IOM Citation2018), the Planning and assisting police operations category reflects the diverse expertise, power, resources and capabilities that different agencies can bring into the planning and implementation of police operations.

Agencies capable of supporting police in trafficking investigations

We found in the present study a lack of consensus concerning which agencies with whom to collaborate when investigating HT crimes. Some interviewees mentioned only six agencies, while others named as many as 18. Furthermore, only seven out of the total 25 agencies identified in the present study were mentioned by 23 participants or more (that is, by at least 80% of the sample size). Participants tended to mention agencies with enforcement powers, with exceptions being largely NGOs-Charities and Local Authorities. Surprisingly, only five participants mentioned the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS), despite existing recommendations to seek the tactical and legal advice of the CPS at the early stages of the investigation to secure more effective evidence gathering (Haughey Citation2016).

Notwithstanding the lack of legal requirement for police forces to collaborate with partner agencies when investigating HT, results from the present study show the perceived importance of multi-agency collaboration to promote the prosecution of offenders and ensure the safeguarding of victims and the disruption of the crime. The interpretation of the median grid suggests that police officers would view agencies as capable of providing support in more than one category. That is, rather than relying upon a single agency to provide a specific type of support, data shows that police officers view partner agencies as capable of assisting in more than one category. However, the high predominance of 2, 3, and 4 scores in the median grid also suggests that no agency was viewed as fully capable of providing all the support needed from one category (the exception being NGOs-charities, who participants rated as being fully capable of providing support for the Working with victims category). While there is no statutory obligation for collaboration, the need for police forces and NGOs-charities to collaborate when Working with victims may well be explained by the particular services each of these agencies provide. That is, while police forces have the resources and powers to refer victims and rescue them from their exploitative situations, NGOs have the training, skills and capability to secure victims’ engagement with the investigation and provide them with the basic safeguarding needs, such as accommodation or counselling. Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire and Rescue Services (HMICFRS Citation2017) identified as good practice regular contact with victims, from their initial identification until the end of the court case. While the Inspectorate found this was not common practice across all forces in England and Wales at the time their report was published, new initiatives focused on victim support and engagement have been introduced by different police forces across England and Wales. An example is the Victim Navigator Programme, which consists of integrating expert NGO workers into HT policing units to provide their expert input during the investigation of trafficking cases and allows them to directly support victims from the moment they are identified (Justice and Care Citation2021). Such a partnership has been argued as a promising practice to both enhance victim-centre police practices and promote victims’ engagement with the police investigation (Van Dyke and Brachou Citation2021).

Likewise, our analysis of the participants’ responses found HMRC to be identified as one of the principal agencies used for Building the criminal intelligence picture. As previously mentioned, HT is a motivated economic crime, and, thus, financial information may be critical to proving the economic profit of the exploitation (Belser Citation2005; HM Government Citation2019). HMRC, the UK lead agency for regulating tax and national minimum wages, has access to a considerable amount of financial intelligence. Thus, police officers seem to agree on the importance of collaborating with HMRC when Building the criminal intelligence picture.

Criminal investigations of HT need to be both victim-centred and intelligence-led. They also need to involve both pro-active and disruptive approaches, requiring multi-agency collaborations. The results from the PrinGrid and Focus cluster do not permit the identification of clear linkages between the various agencies and the types of support they can provide to criminal investigations of HT. Nevertheless, regardless of this limitation, the main results of the data analysis do indicate that officers need to use the experience, knowledge, powers and capabilities of more than one agency for each identified category of support. That is, whereas police offences could investigate trafficking crimes using exclusively just their own powers and capabilities, our findings reveal the importance and benefits of collaborating with multiple agencies as being crucial elements in order to ensure that criminal investigation is conducted effectively.

Limitations and future directions

While the present study brings new insights into the understanding of police collaborations with partner agencies to investigate HT crimes, some limitations still need to be acknowledged. One of the most recognised limitations of the RGT is the amount of effort and time both the researcher and interviewee need to invest (Björklund Citation2008; Fallman and Waterworth Citation2010; Rogers and Ryals Citation2007). Some interviewees may have been fatigued since some participants mentioned seven constructs, while others named as many as 31. While the main purpose of the present study was to understand police collaborations with different partner agencies when investigating HT crimes, further research should also examine in much detail the constraints and opportunities when collaborating with the identified agencies. Another limitation is the generalisability of the results, given the methodology used (i.e. RGT). When using the RGT, results must be interpreted in relation to and relative to the elements gathered within the grid (Björklund Citation2008; Fallman and Waterworth Citation2010). Thus, the categories of support identified and the results of the median grid need to be understood on these bases.

Notwithstanding the matter that our findings may not be generalisable, methodological steps were taken to ensure their reliability. Firstly, twenty-eight police officers (from police units investigating HT crimes) from 19 police forces agreed to participate. Secondly, inter-rater test analyses were conducted for both the names used for the different individual constructs and the categories identified, finding strong levels of agreement. Finally, one of the most mentioned benefits of the technique is its capacity to reduce the interviewer’s bias. Through the interviewer having minimal input in the completion of the grid, it is possible to gather the interviewee’s own understanding of the experience, without introducing previous conceptions and schemas and so allowing fully elicitation and interpretation of the grid based on the interviewee’s meaning of the experience (Curtis et al. Citation2008; Fallman and Waterworth Citation2010). In order to secure that benefit, the interviewees elicited both elements and constructs, reducing any researcher bias and allowing the interviewees to mention as many agencies and types of support as participants considered adequate (Curtis et al. Citation2008).

Conclusion

Security network research has emphasised the importance of networking and cooperation among agencies and police forces when responding to complex forms of criminality such as human trafficking crimes. The diversity of perpetrators and victims, the difficulties in identifying and safeguarding victims and the commission of other offences alongside trafficking offences explain why police need to cooperate with other agencies when investigating trafficking crimes. However, one recurring issue in trafficking investigations is the lack of understanding concerning with whom to collaborate, and for what purpose (Crawford and L’Hoiry, Citation2017; HMICFRS Citation2017; IASC and University of Nottingham Citation2017). Such shortfalls in understanding can create discrepancies among the practices conducted by police forces when investigating trafficking crimes. Furthermore, this situation can also make collaborating more difficult. As previous research has found, partners need to be fully cognisant as to how their contribution complements the whole investigation (Schorrock et al. Citation2019). The present study provides a better understanding concerning what support from other agencies police officers need when investigating HT crimes. Results demonstrate that to secure victim-centred investigations, intelligence-led investigations, and proactive and disruptive approaches, police forces will need the support of different agencies in five main categories. They are: Working with victims, Obtaining information about premises and companies, Obtaining information about individuals, Building the criminal intelligence picture, and Planning and assisting police operations/strategies.

Information sharing is still one of the main challenges in the response to HT crimes (United States Department of State Citation2019; HMICFRS Citation2017). While different aspects contribute to this challenge, such as poor data management practices or lack of standardisation, one of the main ones is ‘siloed’ data. That is, data being only accessible for the agency collecting the data (United States Department of State Citation2019). Hence, it has been argued that working in partnership could promote proactive and intelligence-led investigations, therefore reducing the need to rely on victims’ testimony to ensure prosecution (ATMG 2018; Haughey Citation2016; HMICFRS Citation2017). The benefits of multi-agency arrangements are not only recognised for intelligence purposes but also for ensuring a more comprehensive response, as results from the current study demonstrate. That is, a response that ensures that the expertise of different stakeholders is shared and that powers and capabilities from various agencies are used to identify and safeguard victims of trafficking, as well as for disrupting HT crimes (Farrell et al. Citation2008; Gerassi et al. Citation2017; Matos et al. Citation2018; Wilson and Dalton Citation2008). HMICFRS (Citation2017) found that many victims of trafficking receive inadequate support from the police. While academic and policy discussions exist on how protection and prosecution should complement each other (see Brunovskis and Skilbrei Citation2016), the study's findings reveal the specific types of support, expertise and capabilities needed from partner agencies when safeguarding and engaging with victims of trafficking.

Overall, the findings evidence the need for police officers to collaborate with partner agencies in a series of core aspects to secure an effective investigative performance. The findings from the present study will aid investigators when identifying partner agencies whose expertise can support the investigation as well as acknowledge the meaningful contribution of partner agencies in trafficking investigations.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (86.6 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 The first independent rater was a PhD student with substantial familiarity with the area of study who was trained by the researchers.

2 The second independent rater was an experienced professional within the subject area, who was also academically qualified with a degree in a cognate subject, and who was also trained by the researchers.

3 Local authority department within the UK that enforces consumer protection legislation.

References

- Ambrosini, V., and Bowman, C., 2001. Tacit knowledge: Some suggestions for operationalization. Journal of management studies, 38 (6), 811–829.

- Andrevski, H., Larsen, J., and Lyneham, S. 2013. Barriers to trafficked persons’ involvement in criminal justice proceedings: an Indonesian case study. Trends and Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice, 451. Canberra, Australia: Australian Institute of Criminology. Available from: https://www.aic.gov.au/publications/tandi/tandi451 [Accessed 15 December 2021].

- Anti-Trafficking Monitoring Group (ATMG). 2018. Before the harm is done. Examining the UK’s response to the prevention of trafficking [online]. Available from: https://www.antislavery.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Before-the-Harm-is-Done-report.pdf [Accessed 15 December 2021].

- Belser, P. 2005. Forced labour and human trafficking: estimating the profit [online]. Geneva: International Labour Organisation. Available from: http://www.ilo.int/global/topics/forced-labour/publications/WCMS_081971/lang–en/index.htm [Accessed 15 December 2021].

- Bjelland, H.F., 2020. Conceptions of success: Understandings of successful Policing of human trafficking. Policing: a journal of policy and practice, 14 (3), 712–725.

- Björklund, L., 2008. The repertory grid technique: making tacit knowledge explicit: assessing creative work and problem-solving skills. In: H. Middleton, ed. Researching technology education: methods and techniques. Sense, 46–69.

- Block, L., 2008. Combating organised crime in Europe: practicalities of police cooperation. Policing: an international journal of police strategies and management, 2, 74–81.

- Bouche, V., Farrell, A., and Wittmer, D. 2016. Identifying effective counter-trafficking programs and practices in the U.S.: Legislative, legal and public opinions strategies that work [online]. Available from: https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/249670.pdf [Accessed 15 December 2021].

- Brunovskis, A., and Skilbrei, M., 2016. Two birds with one stone? Implications of conditional assistance in victim protection and prosecution of traffickers. Anti-trafficking review, 6, 13–30.

- Campana, P., 2016. The structure of human trafficking: lifting the bonnet on a Nigerian transnational network. British journal of criminology, 56 (1), 68–86.

- Clawson, H.J., et al. 2008. Prosecuting human trafficking cases: lessons learned and promising practices [online]. Available from: https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/223972.pdf [Accessed 15 December 2021].

- Cockbain, E., and Brayley-Morris, H., 2018. Human trafficking and labour exploitation in the casual construction industry: an analysis of three major investigations in the UK involving Irish traveller offending groups. Policing: a journal of policy and practice, 12 (2), 129–149.

- Cohen, J., 1988. Statistical power analysis. 2nd ed. Hillsdale NJ: Erlbaum.

- College of Policing. 2019. Major investigation and public protection: Modern Slavery [online]. Available from: https://www.app.college.police.uk/app-content/major-investigation-and-public-protection/modern-slavery/ [Accessed 15 December 2021].

- Council Directive 2011/36/EU of 5 April 2011 on preventing and combating trafficking in human beings and protecting its victims, and replacing Council Framework Decision 2002/629/JHA. 2011. Official Journal of the European Union, L101/1.

- Crawford, A., and L’Hoiry, X., 2017. Boundary crossing: networked policing and emergent ‘communities of practice’ in safeguarding children. Policing and society, 27 (6), 636–654.

- Crockett, R., et al. 2013. Assessing the early impact of Multi-Agency Safeguarding Hubs (MASH) in London [online]. Available from: https://www.londonscb.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/mash_report_final.pdf [Accessed 15 December 2021].

- Curtis, A.M., et al., 2008. An overview and tutorial of the repertory grid technique in information systems research. Communication of the association for information systems, 23 (3), 37–62.

- Dandurand, Y., 2017. Human trafficking and police governance. Police practice and research, 18 (3), 322–336.

- David, F. 2007. Law enforcement responses to trafficking in persons: challenges and emerging good practice [online]. Trends and Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice, 347. Canberra, Australia: Australian Institute of Criminology. Available from: https://www.aic.gov.au/publications/tandi/tandi347 [Accessed 15 December 2021].

- David, F. 2008. Trafficking of women for sexual purposes [online]. Research and Public Policy Series, 95. Canberra, Australia: Australian Institute of Criminology. Available from:https://www.dss.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/05_2012/rrp95_trafficking_of_women.pdf [Accessed 15 December 2021].

- Decker, S.H., 2015. Human trafficking: contexts and connections to conventional crime. Journal of crime and justice, 38 (3), 291–296.

- Duijn, P.A.C., Kashirin, V., and Sloot, P.M.A., 2015. The relative ineffectiveness of criminal network disruption. Scientific reports, 4 (4238), 1–15.

- Easterby-Smith, M., 1980. The design, analysis and interpretation of repertory grids. International journal of man-machine studies, 13, 3–24.

- Fallman, D., and Waterworth, J., 2010. Capturing user experiences of mobile information technology with the repertory grid technique. Human technology: an interdisciplinary journal of humans in ict environments, 6 (2), 250–268.

- Farrell, A., McDevitt, J., and Fahy, S. 2008. Understanding and improving law enforcement responses to human trafficking [online]. Available from: https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/222752.pdf [Accessed 15 December 2021].

- Farrell, A., Owens, C., and McDevitt, J., 2014. New laws but few cases: understanding the challenges to the investigation and prosecution of human trafficking cases. Crime, law and social change, 61, 139–168.

- Fischer, H., Vestby, A., and Bjelland, H., 2017. ‘It’s about using the full sanction catalogue’: on boundary negotiations in a multi-agency organised crime investigation. Policing and society, 27 (6), 655–670.

- Foot, K., 2015. Collaborating against human trafficking: cross-sector challenges and practices. Rowman and Littlefield publisher.

- Fox, C., and Butler, G., 2004. Partnerships: where next? Safer communities, 3 (3), 36–44.

- Fransella, F., Bell, R.C., and Bannister, D., 2004. A manual for repertory grid technique (2nd edition). John Wiley and Sons.

- Friesendorf, C. 2009. Strategies against human trafficking: the role of the security sector [online]. Available from: https://documentation.lastradainternational.org/lsidocs/Trafficking+Complete[1].pdf [Accessed 15 December 2021].

- Gains, B.R., and Shaw, M.L. 2018. RepGrid manual. Eliciting, entering, editing, and analysing a conceptual grid [online]. Available from: https://pages.cpsc.ucalgary.ca/~gaines/repplus/ [Accessed 15 December 2021].

- Gallagher, A., and Holmes, P., 2008. Developing an effective criminal justice response to human trafficking. International criminal justice review, 18 (3), 318–343.

- Gerassi, L., Nichols, A., and Michelson, E., 2017. Lessons learned: benefits and challenges in interagency coalitions addressing sex trafficking and commercial sexual exploitation. Journal of human trafficking, 3 (4), 285–302.

- Group of Experts on Actions against Trafficking in Human Beings (GRETA). 2016. 6th General report on GRETA’s activities [online]. Available from: https://rm.coe.int/1680706a42 [Accessed 15 December 2021].

- Harvey, J.H., Hornsby, R.A., and Sattar, Z., 2015. Disjointed service: an English case study of multiagency provision in tackling child trafficking. British journal of criminology, 55 (3), 494–513.

- Haughey, C. 2016. The Modern Slavery Act review [online]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/modern-slavery-act-2015-review-one-year-on [Accessed 15 December 2021].

- Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire and Rescue Services (HMICFRS). 2017. Stolen freedom: The policing response to modern slavery and human trafficking [online]. Available from: https://www.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/hmicfrs/wp-content/uploads/stolen-freedom-the-policing-response-to-modern-slavery-and-human-trafficking.pdf [Accessed 15 December 2021].

- HM Crown Prosecution Service Inspectorate. 2017. The CPS response to the Modern Slavery Act 2015 [online]. Available from: https://www.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/hmcpsi/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2017/12/MSA_thm_Dec17_frpt.pdf [Accessed 15 December 2021].

- HM Government. 2014. The Modern Slavery strategy [online]. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/383764/Modern_Slavery_Strategy_FINAL_DEC2015.pdf [Accessed 15 December 2021].

- HM Government. 2019. 2019 UK Annual report on modern slavery [online]. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/840059/Modern_Slavery_Report_2019.pdf [Accessed 15 December 2021].

- Hodgkinson, E., et al., 2017. The attitudes of pregnant women and midwives towards raised BMI in a maternity setting: A discussion of two repertory grid studies. Midwifery, 45, 14–20.

- Holgersson, S., and Gottschalk, P., 2008. Police officers’ professional knowledge. Police practice and research, 9 (5), 365–377.

- Huff-Corzine, L., et al., 2017. Florida’s task force approach to combat human trafficking: an analysis of county-level data. Police practice and research, 18 (3), 245–258.

- Huisman, W., and Kleemans, E.R., 2014. The challenges of fighting sex trafficking in the legalized prostitution market of the netherlands. Crime, law and social change, 61 (2), 215–228.

- Hyland, K. 2016. Independent Anti-Slavery Commissioner. Annual report 2015-2016 [online]. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/559571/IASC_Annual_Report_WebReadyFinal.pdf [Accessed 15 December 2021].

- Independent Anti-Slavery Commissioner (IASC) and University of Nottingham. 2017. Collaborating for freedom: anti-slavery partnerships in the UK [online]. Available from: https://www.antislaverycommissioner.co.uk/media/1186/collaborating-for-freedom_anti-slavery-partnerships-in-the-uk.pdf [Accessed 15 December 2021].

- International Organisation for Migration (IOM). 2018. Investigating human trafficking cases using a victim centred approach: a trainer’s manual on combating trafficking in persons for capacity-building of law enforcement officers in Antigua and Barbuda, Belize, Jamaica, and Trinidad and Tobago [online]. Available from: https://publications.iom.int/books/investigating-human-trafficking-cases-using-victim-centred-approach-trainers-manual-combating [Accessed 15 December 2021].

- Justice & Care. 2021. Victim Navigator Interim Report [online]. Available from: https://justiceandcare.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Victim-Navigator-Interim-Evaluation-July-2021.pdf [Accessed 17 April 2022].

- Keast, R., Bown, K., and Mandell, N., 2007. Getting the right mix: unpacking integration meanings and strategies. International public management journal, 10 (1), 9–33.

- Kelly, G.A., 1955. The psychology of personal constructs. Norton.

- Kirby, S., and Nailer, L., 2013. Using a prevention and disruption model to tackle a UK organised crime group. Home Office.

- Lagon, M.P., 2015. Traits of transformative anti-trafficking partnerships. Journal of human trafficking, 1 (1), 21–38.

- Leman, J., and Janssens, S., 2008. The Albanian and post-soviet business of trafficking women for prostitution. European journal of criminology, 5 (4), 433–451.

- L’Hoiry, X., 2021. ‘It’s like I’m having an affair’: Cross-force police collaborations as complex problems. Policing: a journal of policy and practice, 15 (2), 1095–1109.

- Malloch, M., Warden, T., and Hamilton-Smith, N. 2012. Care and Support for Adult Victims of Trafficking in Human Beings: A review [online]. Scottish Government. Social Research series. Scottish Centre for Crime and Justice Research. Available from: https://www.gov.scot/publications/care-support-adult-victims-trafficking-human-beings-review/pages/4/ [Accessed 15 December 2021].

- Matos, M., Gonçalvez, M., and Maia, A., 2018. Human trafficking and criminal proceedings in Portugal: discourses of professionals in the justice system. Trends in organized crime, 21, 370–400.

- Matos, M., Gonçalvez, M., and Maia, A., 2019. Understanding the criminal justice process in human trafficking cases in Portugal: factors associated with successful prosecutions. Crime, law and social change, 72, 501–525.

- McGaha, J.E., and Evans, A., 2009. Where are the victims? The credibility gap in human trafficking research. Intercultural human rights law review, 4, 240–266.

- McManus, M., and Boulton, L. 2020. Evaluation of integrated multi-agency operational safeguarding arrangements in Wales [online]. Available from: https://safeguardingboard.wales/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/2021/01/Final-report-Phase-1-January-2020.pdf [Accessed 17 April 2022].

- Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons. 2020. United Kingdom: Tier 1 [online]. Available from: https://www.state.gov/reports/2020-trafficking-in-persons-report/united-kingdom/ [Accessed 15 December 2021].

- O’Leary, R., and Vivj, N., 2012. Collaborative Public Management: where have we been and where are we going? The American review of public administration, 42 (5), 507–522.

- Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). 2010. Analysing the business model of trafficking in human beings to better prevent the crime [online]. Available from: https://www.osce.org/secretariat/69028?download=true [Accessed 15 December 2021].

- Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). 2014. Leveraging anti-money laundering regimes to combat trafficking in human beings [online]. Available from: https://www.osce.org/secretariat/121125?download=true [Accessed 15 December 2021].

- Pajόn, L. and Walsh, D, 2020. Proposing a theoretical framework for the criminal investigation of human trafficking crimes. Policing: a journal of policy and practice, 14 (2), 493–511.

- Robbins, R., et al., 2014. Domestic violence and multi-agency risk assessment conferences (MARACs): a scoping review. The journal of adult protection, 16 (6), 389–398.

- Rogers, B., and Ryals, L., 2007. Using the repertory grid to access the underlying realities in key account relationships. International journal of market research, 49 (5), 595–612.

- Russell, A., 2018. Human trafficking: A research synthesis on human-trafficking literature in academic journals from 2000–2014. Journal of human trafficking, 4 (2), 114–136.

- Salt, J., 2000. Trafficking and human smuggling: a European perspective. International migration, 38 (3), 31–56.

- Schorrock, S., McManus, M.M., and Kirby, S., 2019. Practitioner perspectives of multi-agency safeguarding hubs (MASH). The journal of adult protection, 22 (1), 9–20.

- Severns, R., Paterson, C., and Brogan, S., 2020. The transnational investigation of organised modern slavery: A critical review of the use of joint investigation teams to investigate and disrupt transnational modern slavery in the United Kingdom. International journal of crisis communication, 4, 11–22.

- Sheldon-Sherman, J., 2012. The missing “P”: prosecution, prevention, protection, and partnership in the trafficking victims protection Act. Penn state law review, 117, 443–501.

- Silverman, B. 2014. Modern Slavery: An application of Multiple Systems Estimation [online]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/modern-slavery-an-application-of-multiple-systems-estimation [Accessed 15 December 2021].

- Tan, F.B., and Hunter, M.G., 2002. The Repertory Grid Technique: A method for the study of cognition in information systems. Mis Quarterly, 26 (1), 39–57.

- Taylor, T.Z., et al., 2013. A police officer’s tacit knowledge inventory (POTKI): establishing construct validity and exploring applications. Police practice and research, 14 (6), 478–490.

- UK Annual Report on Modern Slavery. 2020. [online]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/2020-uk-annual-report-on-modern-slavery [Accessed 15 December 2021].

- United Nations Office of Drugs and Crime (UNODC). 2006. Toolkit to combat trafficking in persons, global programme against trafficking in human beings [online]. Available from: https://www.unodc.org/documents/human-trafficking/HT-toolkit-en.pdf [Accessed 15 December 2021].

- United Nations Office of Drugs and Crime (UNODC). 2009. Module 5: Risk assessment in trafficking in persons investigations [online]. Available from: https://www.unodc.org/documents/human-trafficking/TIP_module5_Ebook.pdf [Accessed 15 December 2021].

- United States Department of State. 2005. Trafficking in persons report, June 2005 [online]. Available from: http://www.tipheroes.org/media/1286/47255.pdf [Accessed 15 December 2021].

- United States Department of State. 2019. Trafficking in persons report, June 2019 [online]. Available from: https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/2019-Trafficking-in-Persons-Report.pdf [Accessed 15 December 2021].

- Van der Watt, M., and Van der Westhuizen, A., 2017. (Re)configuring the criminal justice response to human trafficking: a complex-systems perspective. Police practice and research, 18 (3), 218–229.

- Van Dyke, R., and Brachou, A. 2021. What looks promising for tackling modern slavery > a review of practice/based research [online]. Available from: https://www.antislaverycommissioner.co.uk/media/1565/modern-slavery-report-what-looks-promising-a4-brochure-21-031-feb21-proof-2.pdf [Accessed 17 April 2022].

- Walk Free. 2018. Global Slavery Index [online]. Available from: https://www.globalslaveryindex.org/2018/methodology/prevalence/ [Accessed 15 December 2021].

- Whelan, C., 2017. Managing dynamic security networks: towards the strategic managing of cooperation, coordination and collaboration. Security journal, 30, 310–327.

- Whelan, C., and Dupont, B., 2017. Taking stock of networks across the security field: a review, typology and research agenda. Policing and society, 27 (4), 1–17.

- Wilson, J., and Dalton, E., 2008. Human trafficking in the heartland. Journal of contemporary criminal justice, 24 (3), 296–313.

Appendix 1.

Glossary

HM Revenue and Customs (HMRC) – the UK Government agency responsible for the administration of individuals’ and company taxes

Local Authorities – Local government agencies responsible for governmental administration at a local level across the UK

Gangmaster and Labour Abuse Authority (GLAA) – The UK Government agency responsible for the monitoring and investigation of labour exploitation

Immigration Enforcement – A UK Government agency responsible for the enforcing immigration law in the UK

National Crime Agency (NCA). – The UK agency responsible for developing national intelligence on criminal activity such as human trafficking

Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) – the UK Government agency responsible for welfare, pensions and child maintenance policy.

Health services – public services responsible for providing medical care

Health and Safety Executive (HSE) – UK government agency responsible for the encouragement, regulation and enforcement of workplace health, safety and welfare.

Regional Organised Crime Unit (ROCU) – police units that provide a range of specialist policing capabilities to forces within their regions, which help them to tackle serious and organised crime effectively

Border Force – the UK law enforcement agency responsible of securing the UK border by carrying out immigration and customs controls for people and goods entering the UK.

Government Agency Intelligence Network (GAIN) – a multi-agency network mainly made up of public sector agencies, set up to exchange information about organised criminals.

The Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) – non-ministerial department agency responsible for prosecuting criminal cases investigated by the police and other investigative authorities, in England and Wales.