ABSTRACT

Defiance can be a powerful mechanism of protest against police oppression. At the same time, citizen defiance to police authority is problematic for police and can cause injury to both police officers and the public. Research shows that some groups of people defy police more than others, and that defiance often represents a reaction to disenfranchisement, police bias and unfair treatment. For example, the Black Lives Matter movement has highlighted that Black, First Nations peoples and racial/ethnic minority groups are more likely to experience problematic relationships with the police. This study focuses on understanding the factors that drive defiance toward police within two ethnic minority communities in Australia. Testing a new theoretical model, we find that procedural injustice from police can create identity threats, thus explaining why some ethnic minority individuals choose to defy the police. Alternatively, procedural justice may reduce identity threats and defiance.

Introduction

Public defiance of police authority undoubtedly makes police work difficult. Defiance can manifest in reduced engagement and cooperation with police and has the potential to elicit violent reactions from citizens and police alike (Alpert and Dunham Citation2004). Yet, at the same time, defiance can be a powerful mechanism of protest in response to police oppression and unfair treatment. The Black Lives Matter movement is a salient example. As we have seen during this movement, defiance expressed toward police authority in the United States and elsewhere, signals dissatisfaction with the way that police wield power, indicating that police legitimacy may be declining, and that change is needed.

While the Black Lives Matter movement primarily focusses on African American experiences, historical relationships between police and First Nations peoples, immigrant groups, and racial and ethnic minority groups in other contexts suggest that many minority groups experience procedural injustice and bias from police, and are subsequently less trusting of the police, less willing to report crime to the police, and more likely to defy police authority (Davis and Mateu-Gelabert Citation2000, Cunneen Citation2001, Van Craen Citation2012, Murphy Citation2013, Wu et al. Citation2013, Piatkowska Citation2015, Khondaker et al. Citation2017). In this paper we examine how and why some ethnic minority group members may come to defy police authority. To do so we adopt an identity threat paradigm. Specifically, we draw on Braithwaite’s (Citation2009, Citation2013) Theory of Defiance and Tyler and Blader’s (Citation2003) Group Engagement Model to inform an integrated theoretical framework connecting procedural injustice, identity threats, legitimacy and defiance. While prior research finds that perceptions of procedural injustice from police is related to reduced public identification with police and the groups they represent (e.g. Bradford et al. Citation2014, Olivera and Murphy Citation2015, Sargeant et al. Citation2016, Bradford et al. Citation2017, Murphy et al. Citation2022), decreased perceptions of police legitimacy (e.g. Bradford et al. Citation2014, Olivera and Murphy Citation2015, Bradford et al. Citation2017) and increased resistance and/or disengagement (e.g. Murphy, Citation2016, Citation2021, Sargeant et al. Citation2016, Citation2021), the relationship between procedural injustice, identity threat, police legitimacy and defiance is not yet well understood. We begin our paper by introducing the concepts of identity threat and defiant motivational postures.

Identity threats and defiant motivational postures

Braithwaite’s Theory of Defiance (Citation2009, Citation2013) describes the way that identity threats can lead to defiance of authority. Aquino and Douglas (Citation2003, p. 196) define an identity threat ‘as any overt action by another party that challenges, calls into question, or diminishes a person’s sense of competence, dignity, or self-worth’. Braithwaite (Citation2009, Citation2013) contends that in a regulatory system, people typically see their identity in three ways: the moral-self, the democratic-collective-self, and the status-seeking-self. Each of these self-identities are important to the individual and shape how they perceive and react to encounters with authorities: the moral-self takes pride in being a good, law-abiding citizen; the democratic-collective-self reflects a sense of being a member of a collective community whose voices are valued, listened to, and heeded; and the status-seeking-self is concerned with goal-attainment, recognition, status and achievement.Footnote1 Braithwaite (Citation2009, Citation2013) argues that authorities such as police, by virtue of the power they wield, can pose a threat to people’s freedoms as well as the identities they hold dear.

Aquino and Douglas (Citation2003, p. 196) argue that people will strive to maintain a positive sense of self in response to an identity threat. They similarly suggest that when a ‘self’ or ‘social identity’ is threatened, a person will act to defend their identity (Aquino and Douglas Citation2003, p. 196). Correspondingly, Braithwaite (Citation2009, Citation2013) contends that individuals respond to identity-threats by displaying different types of motivational postures. These postures represent the degree of psychological distance an individual wishes to place between themselves and the source of the threat, which is usually envisaged as an authority of some kind (Braithwaite Citation2009, Citation2013). Defiant motivational postures are used to signal that an authority’s policies and/or actions are unacceptable or require change (Braithwaite Citation2009, Citation2013). Braithwaite (Citation2009, Citation2013) describes three defiant motivational postures: game-playing, resistance, and disengagement. While game-playing is less relevant in studies of policing,Footnote2 resistance and disengagement can be routinely observed in how citizens behave toward police (see Murphy Citation2016, Citation2021). Braithwaite (Citation2009) explains the distinction between these two postures as follows: resisters object to the actions of authorities and push-back against the way citizens are treated, but do not necessarily object to the existence or legitimacy of the authority or the power they hold; while disengagers are dismissive of authorities, object to their power (and/or existence), and avoid contact with the authority. Braithwaite (Citation2013) finds that when the moral-self, the democratic-collective-self and the status-seeking-self are threatened by an authority, defiance can ensue.

Defiance, identity threat, and ethnic minority group status

Braithwaite’s (Citation2009, Citation2013) Theory of Defiance provides a useful framework for understanding how and why ethnic minority group members may come to defy police authority. Braithwaite’s concept of identity threat can be utilised to explain the way in which minority group members may experience manifestations of police authority and police bias and why they may defy police authority (see also Kahn et al. Citation2018). For this reason, while few studies test Braithwaite’s theory in the context of policing, those which do tend to indicate its utility for understanding ethnic minority dispositions toward police. For example, Murphy and Cherney (Citation2012) found that ethnic minority respondents were more likely to report disengaging from police compared to non-minority group respondents. Sargeant et al. (Citation2021) found that social identity and perceived unfair treatment by the police helped to explain why some ethnic minority group members held defiant motivational postures toward police. Similarly, Murphy (Citation2021) found that perceived procedural injustice from police was related to Muslims’ enhanced resistance to police, and that concern about police overstepping the bounds of appropriate authority was associated with their level of disengagement from police.

Related research examining the consequences of identity threat supports the connection between ethnicity, identity threat and attitudes toward police. Najdowski et al. (Citation2015) examined the relationship between stereotype threat (an identity threat applied to one’s collective group) and experiences with police, among Black, compared to White undergraduate student participants. In hypothetical encounters with police, Black participants were concerned that police officers would stereotype them as criminals due to their race (similar to Braithwaite’s conceptualisation of threats to the moral-self). Moreover, they found that Black participants expected to be treated unfairly because of these negative stereotypes. Defiance was not the focus of Najdowski et al.’s. research, however.

In another study, Kahn et al. (Citation2017) examined the impact of identity threat on trust in, and cooperation with the police, among ethnic minority groups. Kahn et al. (Citation2017, p. 418) explained the identity threat process as follows: ‘When individuals feel they will be treated differently or devalued based on their social identity (i.e. race, gender, sexual orientation), it can have negative behavioural, affective, and cognitive consequences’ (see also Steele Citation1997, Major and O’Brien Citation2005). In the context of policing ethnic minority groups, Kahn et al. (Citation2017) proposed that identity threats arise due to racial group stereotyping. They suggest that the ‘negative psychological experience’ of identity threat ‘can lead to avoidance of the negatively stereotyped setting in the future’ (see also Davies et al. Citation2002, Citation2005). This proposition is similar to Braithwaite’s (Citation2009) theory, whereby a threatened self-identity may lead individuals to disengage from police. In their study, Kahn et al. (Citation2017) found that their measure of race-based identity threat negatively predicted trust in the police among 169 racial minority participants (and through distrust, predicted reduced cooperation with police). Kahn et al. (Citation2017, p. 424) concluded that ‘social identity threats may create a self-fulfilling prophecy by both police and racial minorities’ and that the ‘more racial minorities feel that they will be negatively treated based on their race, whether due to past or expected experiences, the more they might avoid open engagement when interacting with a police officer’. These findings provide support for Braithwaite’s (Citation2009) assertion that identity threats (to the moral, democratic-collective and status-seeking selves) are likely to increase defiance toward police. These findings also suggest that identity threat may be tied to perceptions of biased or unfair treatment.

Procedural injustice, legitimacy, identity threat and defiance: an integrated theoretical model

What is it, specifically, about police behaviour that may threaten the identities of minority group members (indeed anyone) with whom officers interact? One answer may be found in the currently dominant theoretical paradigm employed to understand attitudes and behaviour toward police – the process-based model of police legitimacy. This model has a particular focus on the importance of procedural justice (fair treatment and decision-making processes by police) to people’s legitimacy judgements regarding police. Police legitimacy or ‘a property of an authority or institution that leads people to feel that that authority or institution is entitled to be deferred to and obeyed’ (Sunshine and Tyler Citation2003, p. 514), captures the ‘acceptance by people of the need to bring their behaviour into line with the dictates of an external authority’ (Tyler Citation1990, p. 25). In the process-based model, procedural justice is found to be the key antecedent of police legitimacy evaluations (e.g. Tyler Citation1990, Sunshine and Tyler Citation2003). That is, when people perceive that the police treat them fairly on an interpersonal basis (with dignity and respect) and demonstrate fairness in decision-making processes (make decisions in a neutral and unbiased fashion), they are more likely to perceive police as legitimate and bring their behaviour in line with the dictates of police authority (Tyler Citation1990, p. 25). Procedurally unjust treatment will lead to decreased beliefs in police legitimacy.

Similar to Braithwaite’s (Citation2009, Citation2013) Theory of Defiance, police legitimacy can be understood within the context of an identity-framework. Tyler and Blader’s (Citation2003) Group Engagement Model suggests that when group-authorities exhibit procedural justice in interactions with group members they will enhance group members’ identification with the group the authority represents, conversely, procedural injustice will reduce identity. This is because fair treatment facilitates feelings of pride and respect in group membership, thus bolstering ties to the group (Tyler and Blader Citation2003). As Tyler and Blader (Citation2003, p. 349) explain: ‘procedures are important because they shape people’s social identity within groups, and social identity in turn influences attitudes, values, and behaviours’. In the case of policing, the experience of procedural justice in encounters with officers is thought to facilitate identification both with the police as a distinct social group (Radburn et al. Citation2018, Murphy Citation2021) and with the wider social categories the police represent (e.g. the nation-state or one’s ‘community’), which, in turn, will enhance police legitimacy judgements (Bradford et al. Citation2014, Murphy Citation2021). Indeed, Bradford et al. (Citation2014) found evidence to support this pathway in their study of Australians’ perceptions of police, showing that the relationship between procedural justice and police legitimacy is, at least in part, a function of social identity processes.

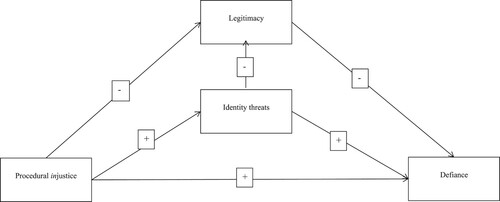

We argue that incorporating the concepts of identity threat into the process-based paradigm may provide a more comprehensive understanding of the development of perceptions of police legitimacy among ethnic minority groups. In turn, identity threats and legitimacy will help to explain ethnic minority group defiance toward police. Based on our review of theory and research we propose a new integrated theoretical model of the relationship between procedural injustice, identity threat, legitimacy and defiant motivational postures (see ).

We can summarise our theoretical model according to the following five propositions:

Proposition 1: Drawing and expanding upon the Group Engagement Model (Tyler and Blader Citation2003), we argue that perceived procedural injustice will lead to identity threats. If police use their power in an unfair manner which, for example, insinuates that ethnic minority group members are viewed with suspicion (as in racial profiling), this could threaten one’s moral-self; if police treat ethnic minority group members in a rude or undignified manner this could threaten one’s democratic-collective-self; if police unfairly target certain ethnic minority groups because they are seen as a potential threat to Australia’s way of life or Australians’ safety (e.g. immigrants competing for jobs; ethnic minorities involved in organised drug crime or terrorism), this could threaten one’s status-seeking-self (i.e. their goal to feel they belong and be a citizen of equal status in Australia may be threatened).

Proposition 2: In line with the process-based model of police legitimacy, we expect that procedural injustice will have a direct effect on beliefs about police legitimacy, and similarly on resistant and disengaged motivational postures. If a person perceives they are not treated fairly by police, it seems more likely they will become disengaged from police (Kahn et al. Citation2017, Murphy Citation2021), more likely that they will resist police authority (Murphy Citation2021), and less likely that they will perceive police as legitimate (Tyler Citation1990, Sunshine and Tyler Citation2003).

Proposition 3: We anticipate that identity threats will be negatively associated with legitimacy. As outlined in the Group Engagement Model (Tyler and Blader Citation2003, Bradford et al. Citation2014), perceived police legitimacy can be understood as a function of identity-relevant group processes and procedurally just or unjust treatment. Preliminary support for this proposition is provided by research which finds that identity threat reduces trust in police – a concept related to police legitimacy (Kahn et al. Citation2017).

Proposition 4: Drawing on Braithwaite’s Theory of Defiance (Citation2009, Citation2013), we anticipate that identity threats will lead to defiant motivational postures in the form of disengagement and resistance. Braithwaite’s (Citation2009, Citation2013) theory predicts that when police are perceived to threaten the moral-self, the democratic-collective-self and/or the status-seeking-self, defiance will ensue.

Proposition 5: When individuals hold defiant motivational postures they indicate that they question, object to, or dismiss authorities and their power (Braithwaite Citation2009, Citation2013). We therefore anticipate that when an individual believes the police are illegitimate they are more likely to expresses defiant postures toward police (although this relationship may be less salient when predicting resistance as explained above). Indeed, recent research supports an empirical relationship between perceptions of police legitimacy and defiant motivational postures. For example, Madon et al. (Citation2017), found that disengagement from police (one defiant posture) was associated with lower perceptions of police legitimacy among 1,480 ethnic minority group members. Similarly, Murphy (Citation2016), in a study of 1,190 Australians, found that resistance (a defiant posture) was associated with the reduced willingness to cooperate with police (linked to legitimacy).

The current study

In this study we seek to advance theoretical and empirical understandings of ethnic minority defiance toward police by testing this integrated theoretical model of procedural injustice, identity threat, legitimacy and defiance. Prior research finds that perceptions of police procedural injustice is related to reduced identification with police or groups police are said to represent (e.g. Bradford et al. Citation2014, Olivera and Murphy Citation2015, Sargeant et al. Citation2016, Bradford et al. Citation2017, Murphy et al. Citation2022), decreased perceptions of police legitimacy (e.g. Bradford et al. Citation2014, Olivera and Murphy Citation2015, Bradford et al. Citation2017) and increased resistance and/or disengagement (e.g. Murphy Citation2016, Citation2021, Sargeant et al. Citation2016, Citation2021). What is still unclear, however, is the relationship between procedural injustice, an ethnic minority person’s feelings of identity threat, and the effect these feelings of identity threat may have on perceptions of police legitimacy and defiant posturing. This is the gap that the current study addresses.

To test our theoretical model, we employ a sample of ethnic minority group members in Australia. As noted earlier, Murphy and Cherney (Citation2012) reported that ethnic minorities in Australia are generally more disengaged from police than non-minorities. Hence, we expect our chosen sample to be even more likely to adopt disengaged or resistant motivational postures toward police based on this history. These members belong to the Australian Vietnamese and Middle Eastern Muslim communities. These groups are two visible ethnic minority communities in Australia who have been the target of police suspicion as part of the ‘war on drugs’ and ‘war on terror’, respectively, and consequently have a history of strained relationships with police (e.g. Meredyth et al. Citation2010, McKernan and Weber Citation2016, Cherney and Hartley Citation2017, Cherney and Murphy Citation2017). These groups also represent two of the largest ethnic minority groups to immigrate to Australia. Muslim immigrants currently comprise about 2.6% of Australia’s total population, while Vietnamese immigrants comprise approximately 1.2% of the Australian population (ABS Citation2016).

Data collection

Our study draws on survey data collected from 793 Vietnamese and Middle Eastern Muslim first- and second-generation immigrants living in Sydney, Australia (for more information about the survey see Murphy et al. Citation2019). The survey was undertaken in 2018/19 by a Sydney-based survey administration company specialising in the recruitment of Culturally and Linguistically Diverse (CALD) survey samples. The company was provided with a participant quota of 390 Vietnamese and 390 Middle Eastern adult immigrants living in Sydney. Sub-quotas for age (50% < 30 years of age), gender (50% female) and immigrant status (50% first- and 50% second-generation immigrants) were also provided to better represent the characteristics of these two population groups. Participants were required to be aged 18+ years.

As people from Middle Eastern Muslim and Vietnamese backgrounds comprise a small percentage of the Australian population, random probability sampling was not feasible. Instead, participants were recruited using an ‘ethnic surname’ sampling method. In this sampling method a sampling frame of common surnames (e.g. Mohammed; Nguyen) in the two communities was constructed using the Electronic Telephone Directory. The final sampling frame contained 15,118 individuals (7823 Middle Easterners and 7295 Vietnamese). To select participants from this list, the survey administration company telephoned households in the sampling frame at random and asked the person who was next due to celebrate a birthday in the home to participate in a face-to-face survey. This ensured random selection within the household. Interviews were conducted in the participant’s preferred language (i.e. Vietnamese, Arabic or English).

Participants were paid a $40 (AUD) incentive for their participation. The final sample included 793 participants (395 Vietnamese; 398 Middle Eastern Muslim). Response rates (participants/number of potential participants contacted) were computed for the Vietnamese and Middle Eastern Muslim groups as 45.04% and 34.85%, respectively.

Survey measures

The discriminant validity of all relevant survey items was examined prior to the formation of variables for use in the analysis. This is important to do because several of our measures are innovative to the policing context and have not been used in prior research (specifically the measures of identity threat: moral, democratic and status-seeking threat). To assess discriminant validity, we employed a factor analysis with promax rotation in STATA 14. Promax rotation is particularly useful when factor analysing measures are intercorrelated (Tabachnick and Fidell Citation2001). The results of the factor analysis including a description of each survey item are presented in . All items were measured on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from Strongly Disagree (1) to Strongly Agree (5). Further details for each measure are provided in . Factor scores for each factor were computed for use in the subsequent analysis described below.

Table 1. Factor analyses.

Our study incorporates two defiant motivational postures. These are resistance and disengagement. Braithwaite and colleagues originally measured these defiant postures in relation to taxation authorities and nursing home inspectors (Braithwaite Citation1995, Citation2009, Citation2013, Braithwaite et al. Citation2007). The items included in this study were adapted to the policing context by Murphy (Citation2016).

Procedural injustice was measured by reverse coding survey items capturing perceived fair treatment and fair decision-making by police (e.g. ‘Police treat people fairly’; ‘Police let people speak before they make a decision’). These items have been commonly used to measure procedural justice in prior research (Tyler Citation1990). Higher scores on the procedural injustice scale indicate respondents perceived police to be less procedurally just.

Measures of identity threats included in this study capture perceived threats by police to the moral-, democratic-collective, and status-seeking-self identities. These measures were specifically developed for the current study and are based on the theoretical propositions outlined by Braithwaite (Citation2009, Citation2013). In the factor analysis we found that items measuring threat to the moral-self and threat to the democratic-collective-self, loaded onto the same factor (see ). As such, a composite measure entitled moral-democratic threat was constructed. It appears that, at least in the policing context or with this participant sample, there may not be a clear distinction between a threat to the moral-self and a threat to the democratic-collective-self. The logic of this may be that when people perceive that police view a group as criminal this indicates bias – which is clearly un-democratic. The coupling of these two measures is also somewhat consistent with Braithwaite’s (Citation2009) theory, in that Braithwaite suggests that a threat to the moral-self, combined with a threat to the democratic-collective self, will likely lead to the defiant posture of resistance. Status threat (i.e. status-seeking threat) items were distinct from items in this composite measure, however. Higher scores on the moral-democratic threat and status threat scales suggest heightened experiences of identity threat (the status threat measures were reverse coded).

Police legitimacy was measured as a combined scale including two sub-constructs that are commonly used to measure police legitimacy: normative alignment with police, and moral obligation to obey police. Normative alignment refers to the way in which the police and the public share values as well as a sense of right and wrong; moral obligation to obey captures the idea that police are entitled to be obeyed. Our legitimacy measures were drawn from the work of Hough et al. (Citation2017).

Lastly, we included a measure of ethnic minority group. This variable was measured dichotomously (1 = Middle Eastern Muslim and 0 = Vietnamese) and was included as an exogenous variable in our path analysis. We acknowledge that as these two groups have different historical relationships with the police (as outlined above) that this historical context may impact differently on perceptions of procedural injustice and on perceived identity threats.

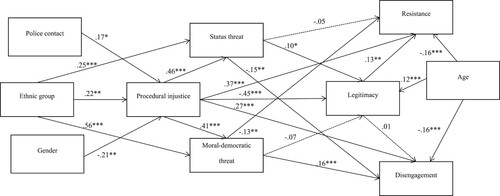

Figure 2. Path analysis with unstandardised estimates and bootstrapped standard errors.

Note: N = 790; Error covariance of resistance and disengagement and of status and moral-democratic identity threats are not depicted. Non-significant paths tested in the final model are represented by broken lines. Ethnic group (1 = Middle Eastern Muslim, 0 = Vietnamese); Gender (1 = female, 0 = male); Police contact (1 = police contact in past 2 years, 0 = no police contact). Coefficients calculated with bootstrapped standard errors (1000 replications). Significance levels shown here are for the unstandardised solution ***p ≤ .001; **p ≤ .01; *p ≤ .05. Coefficients are rounded to 2 decimal places.

Two further demographic control variables were included in our analysis: gender (0 = male; 1 = female) and age. We also controlled for whether individual participants had any previous personal contact with police in the previous two-year period. Prior police contact was dichotomised to reflect contact or no contact (0 = no contact; 1 = contact). Of the sample, 49.8% were female, 43.6% reported that they had had contact with the police in the past 12 months and the average age was 33.69 years (SD = 13.24).

Bivariate statistics

Bivariate correlations between our variables provide insight into the expected relationships likely to be observed in our path model. As can be seen in below, procedural injustice was negatively related to legitimacy (r = −.441, p ≤ .001), and positively related to the defiant postures (disengagement r = .279, p ≤ .001; resistance r = .242, p ≤ .001), and identity threats (moral-democratic r = .449, p ≤ .001; status r = .478, p ≤ .001). These results suggest that perceived procedural injustice from police translates to reduced legitimacy, increased identity threat, and increased defiance.

Table 2. Pearson’s correlation coefficients.

The bivariate correlations also show that resistance was not significantly correlated with legitimacy, however disengagement was negatively and significantly correlated with legitimacy as expected (r = −.153, p ≤ .001). That is, the less legitimate participants believed the police to be, the more disengaged from the police participants were. Similarly, the more police were perceived to represent a moral-democratic threat (r = −.238, p ≤ .001) or status threat (r = −.154, p ≤ .001) to the participants’ identity, the less likely participants were to grant the police legitimacy. Contrary to our expectations, the bivariate correlations indicate that neither type of identity threat was significantly associated with resistance; however moral-democratic identity threat (r = .226, p ≤ .001), was positively and significantly correlated with disengagement. That is, the more participants perceived that the police threatened their moral-democratic identity, the more likely participants were to disengage from the police.

Path analysis

To test our complete theoretical model we used path analysis in STATA 17. presents our results diagrammatically showing significant pathways with standardised coefficients. presents goodness-of-fit statistics for the final model (all satisfactory). presents direct, indirect and total effects in the model (unstandardised coefficients). partitions the indirect effects for key pathways.

Table 3. Goodness-of-fit statistics.

Table 4. Path analysis direct, indirect and total effects, unstandardised coefficients.

Table 5. Partitioning indirect effects for key pathways, unstandardised coefficients.

Direct effects

While not part of our theoretical model, we began our analysis by controlling for age, gender, prior police contact and ethnic minority group in the path analysis. We then trimmed non-significant pathways to enhance model fit. We found that age was negatively and significantly associated with resistance (b = −.16, p ≤ .001) and disengagement (b = −.16, p ≤ .001) and positively and significant related to legitimacy (b = .12, p ≤ .001). As in the bivariate analysis above, older participants were less likely to disengage and resist police and more likely to believe the police were legitimate. Gender (b = −.21, p ≤ .01) and police contact (b = .17, p ≤ .05) were both significantly related to procedural injustice such that men were more likely to believe the police were procedural unjust compared to women, and those who had had prior police contact in the past two years were more likely to believe the police were procedurally unjust compared to those who had no contact.

Turning to ethnic minority group, we found that Middle Eastern Muslim participants were more likely to perceive the police as procedurally unjust (b = .22, p ≤ .001), and more likely to perceive the police as a source of threat to both status (b = .25, p ≤ .001), and moral-democratic (b = .56, p ≤ .001) identities, compared to the Vietnamese participants. These results likely connect back to differences in historical relationships between police and these two groups in Australian (as outlined above) and may be explained by the recency of ‘war on terror’ tensions between police and Muslim communities in Australia. In particular, the height of the ‘war on terror’ (circa 2000s-current) was more recent and perhaps therefore more salient compared to the height of the ‘war on drugs’ in Sydney’s Asian community (circa 1970s–1990s).

Turning now to the key variables in our model. As highlighted in , we anticipated that procedural injustice would lead to greater identity threats (Proposition 1). Our results show that procedural injustice was positively and significantly associated with both status threat (B = .46, p ≤ .001), and moral-democratic threat (b = .41, p ≤ .001). That is, when participants rated police as more procedurally unjust, they were indeed more likely to view police as posing a threat to their status-seeking and moral-democratic self-identities. These results support Proposition 1. Similarly, and as expected, procedural injustice was negatively and significantly associated with legitimacy (b = −.45, p ≤ .001) and positively and significantly associated with the defiant postures (resistance b = .37, p ≤ .001; disengagement b = .27, p ≤ .001) (Proposition 2). That is, when participants viewed police as more procedurally unjust, they were less likely to perceive the police as legitimate; and more likely to hold a resistant or disengaged posture toward police. These results support Proposition 2.

In contrast to the results presented above, the pattern of findings for paths leading from the identity threats to legitimacy and defiance were not entirely as expected. To begin with, of the two types of identity threat (status and moral-democratic), only status threat had a significant relationship with legitimacy, and this relationship was in the opposite direction than was predicted. Status threat was found to be positively associated with legitimacy (b = .10, p ≤ .05), in turn, legitimacy was positively associated with resistance (b = .13, p ≤ .01) when conditioning on all the other variables in the model (these results are in opposition to Propositions 3 and 5).

Turning to Proposition 4, while moral-democratic threat was positively and significantly associated with disengagement (b = .16, p ≤ .001), as expected, status threat was negatively and significantly associated with disengagement (b = −.15, p ≤ .01). These results suggest that the more participants perceived a threat to their moral-democratic self, the more likely they were to display disengaged posturing. However, conditioning on this relationship, the more of a threat the police were perceived to pose to a participants status identity, the less likely participants were to align with a disengaged posture. As a further contrast, even as the relationship between moral-democratic threat was positively associated with disengagement (see above), it was negatively associated with resistance (b = −.13, p ≤ .001) (while status identity threat was not significantly associated with resistance). This suggests that the same type of identity threat can have opposite effects on different defiant motivational postures, at least when simultaneously considering the other variables in our model. We unpack these findings further in the Discussion section below.

Indirect effects

As shows, we predicted a direct relationship between procedural injustice and defiance, as well as an indirect relationship via identity threats and legitimacy (i.e. partial mediation). Moreover, we anticipated that legitimacy would partially mediate the relationship between the identity threats and the defiant postures. To test for mediation we computed direct, indirect and total effects for the model (presented in ) and computed indirect effects for individual pathways for the relationship between procedural injustice and the defiant postures (presented in ).

When reviewing the pathways from procedural injustice to resistance, we can see that, in addition to a direct effect, there is also a negative and significant indirect effect of procedural injustice on resistance (b = −.13, p ≤ .001) (see ). Indirect effects (partitioned by pathway in ) further indicate that the relationship between procedural injustice and resistance is partially mediated by moral-democratic threat (b = −.054, p ≤ .05) and legitimacy (b = −.058, p ≤ .05), but not by status threat (b = −.022; p > .05). It is important to note that some of these relationships are not in the direction we expected; we address this in the Discussion section below.

Next, we examined pathways from procedural justice to disengagement. Results show that both status threat (b = –.054, p ≤ .05) and moral-democratic threat (b = .067, p ≤ .001) partially mediate the relationship between procedural justice and disengagement, whereas legitimacy does not (b = −.002; p > .05) (see ). However, when considering the total indirect effect (which is non-significant) (b = −.006, p > .05) (see ) these pathways appear to cancel each other out.

Lastly, we considered the relationship between the identity threats and the defiant postures. Referring again to , we predicted that legitimacy would mediate the relationship between identity-threats and defiance. shows that there are no significant indirect effects of the identity threats on the defiant postures (that is, legitimacy does not appear to mediate the relationship between the identity threats and defiance).

Interestingly a review of the indirect effects also sheds further light on the relationships between ethnic group and the identity threats. Indirect effects show that these relationships are partially mediated by procedural injustice (status threat b = .101, p ≤ .01; moral-democratic threat b = .091 p ≤ .01) (see ). These results suggest that Middle Eastern Muslim participants in our sample were more likely to perceive status and moral-democratic threats, in part because they were more likely to perceive the police to be procedurally unjust.

Discussion

Recent riots and protest movements against police maltreatment of First Nations peoples, and ethnic and racial minority groups (i.e. the Black Lives Matter movement), highlight the defiance that police behaviour can evoke in minority communities. In this paper we examined the factors associated with minorities’ resistance and disengagement toward police (two types of defiance) in Australia. We also considered the potential flow on effects that minority perceptions of police legitimacy can have on defiance, and the role of police procedural injustice in provoking identity threats. We drew on Braithwaite’s (Citation2009, Citation2013) Theory of Defiance and Tyler and Blader’s (Citation2003) Group Engagement Model to build a new integrated theoretical model examining whether identity threats from police – elicited by signs of procedural injustice – could explain why some minority group members choose to question the legitimacy of police and openly defy police authority.

Before we discuss our results, it is important to note the limitations of our research. First, our survey data are cross-sectional. While we can assume that perceptions of procedural injustice and subsequent identity threats may arise first in the causal pathway to legitimacy and defiance, we are unable to test such causal relationships without longitudinal data. Second, and relatedly, our survey considers perceptions, so we are not able to report on observed behaviours or actual experiences. Like most studies that utilise survey research we can only make inferences based on participants’ attitudes, perceptions and signalled intentions. Third, due to our use of the Electronic Telephone Directory in our sampling strategy, our sample is skewed toward households with landline telephone numbers. Lastly, as our sample includes only ethnic minority group members from the Vietnamese and Middle Eastern Muslim communities in Sydney, Australia, we cannot draw broader conclusions about the way in which our theoretical model may fit for communities outside of those sampled here (including for the same minority communities living in countries outside Australia). However, we also note that, when seeking to better understand the underpinnings of police legitimacy and defiant motivational postures, it is particularly important to examine the experiences of groups who may be more likely to experience procedural injustice and identity threats from police. Our paper offers a unique contribution in this regard.

Let us begin our discussion with the results that fit most neatly with our proposed theoretical model. First, we argued that perceived procedural injustice would lead to identity threats (Proposition 1), or put differently, that perceived procedural justice would reduce identity threats. Our results support this hypothesis. When police are perceived to be procedurally unjust they can elicit an identity threat, and, conversely, procedurally just police behaviour may have some utility in reducing the formation of identity threats. To explain further, we can refer to our specific measures of identity threat. We find that when police are perceived to be procedurally unjust, participants in our sample were more likely to feel that police were disrespectful and suspicious toward them (posing a moral-democratic identity threat) and that police did not ‘view people like you as worthy members of Australian society’ (posing a status identity threat). This finding is consistent with prior theory and research purporting that procedural justice conveys identity-relevant information (Tyler and Blader Citation2003, Bradford et al. Citation2014), and suggests that, just as procedural justice may bolster social identity with groups, procedural injustice may trigger threats to a person’s identity.

Next in our theoretical model we argued that, consistent with the process-based model of police legitimacy, procedural injustice would lead to decreased legitimacy and greater defiance (Proposition 2). Results were as expected, and, among other things, highlight the utility of police being procedurally just. That is, these results suggest that when police behave with procedural justice (when engaging specifically with members of ethnic minority groups often thought to experience ‘difficult’ relations with police), this has the potential to increase the willingness of these individuals to grant police legitimacy and decrease resistance and disengagement.

Our third and fourth propositions were that identity threats would reduce police legitimacy and increase the likelihood of holding a defiant posture toward the police. We found mixed support for these propositions. Greater status threat was associated with increased (not decreased) perceptions of legitimacy, and the relationship between moral-democratic threat and legitimacy was non-significant. Similarly, greater moral-democratic threat was associated with increased disengagement (as expected), whereas greater status threat was associated with reduced disengagement (contrary to expectations), and heightened moral-democratic threat was associated with reduced resistance (contrary to expectations). Lastly, in Proposition 5, we predicted that those who viewed police as legitimate would be less likely to defy the police. We did not find support for this hypothesis. Instead, those who viewed police as more legitimate were actually more inclined to adopt a resistant posture toward police (with no significant relationship between legitimacy and disengagement).

In summary, while the associations between procedural injustice and identity threat and procedural injustice and legitimacy were as predicted, the measures of identity threat and legitimacy had week or inconsistent associations with each other, and with the defiant postures. Moreover, and contrary to our expectations, those who perceived a moral-democratic identity threat and those who granted police more legitimacy tended to be more rather than less resistant to police authority while those who experienced status threat were less likely to disengage from police.

We can partially understand our results through the lens of Braithwaite’s (Citation2009, Citation2013) Theory of Defiance. Braithwaite (Citation2009, Citation2013) suggests that defiant motivational postures offer people the opportunity to distance themselves psychologically and socially from authorities. Doing so protects them from future threat and harms. Distancing is also more likely to occur when an authority poses a threat to their valued identity. In our sample, we found that a threat to the moral-democratic-self, resulted in the desire to create social distance between the individual and the authority (police) in the form of disengagement. These results are like those found by Kahn et al. (Citation2017) who examined the relationship between identity threat and trust in the police among racial minority groups. Kahn et al. (Citation2017) explained the process as follows: the ‘more racial minorities feel that they will be negatively treated based on their race … the more they might avoid open engagement when interacting with a police officer’ (Kahn et al. Citation2017, p. 424). Similarly, Aquino and Douglas (Citation2003) explained that when a person’s positive sense of self is threatened, that person will act to protect and defend themself – in the case of our study this may mean withdrawing/disengaging from the police to avoid any contact and any further unjust treatment and bias.

While the pathways from moral-democratic threat to disengagement fit with our theoretical model, numerous pathways diverged from our expectations as explained above. First, the conditional negative relationship we identified in our multivariate path model between status threat and disengagement did not conform to theorising. In our theoretical model (see ) we anticipated that a threat to the status-seeking-self would lead to increased disengagement (Proposition 3); however we found that, conditional on other variables in the model, the more police threatened the status-seeking-self the less likely members of our sample were to disengage from police. This is contrary to Braithwaite (Citation2013) who argues that when any of the moral, the democratic-collective or status-seeking selves are threatened by an authority, defiance can ensue (see also Kahn et al. Citation2017 as discussed above). Our results indicate that, once accounting for other factors in our model, when an individual’s status as a worthwhile and equal member of Australian society is denied by police, that person may be less (not more) likely to disengage from the police.

How can we explain this rather unexpected finding? One possible explanation is that this relationship may be associated with a process of stigma management – which could be particularly relevant given the composition of our sample. As explained by O’Brien (Citation2011, p. 292) ‘Stigma management is the attempt by persons with stigmatised social identities to approach interpersonal interactions in ways aimed at minimising the social costs of carrying these identities’ (see also Goffman Citation1971). In research examining ethnic minority group members, Ryan (Citation2010, Citation2011) explored the way that these groups may respond to stigma. Ryan’s (Citation2011, p. 1045) study of stigma among Muslim women in Britain found that women resisted stigma through asserting their ‘moral integrity’ and normality. Applied to our results, it may be that the ethnic minority participants in our study (Middle Eastern Muslim and Vietnamese minority group members) respond to threats to their status-seeking-self not by defying or disengaging from police, but rather by seeking to reaffirm their identity as a person of status and value in society though displaying willingness to engage with the police. In other words, despite the police being the cause of an identity threat, engaging with police may be a way to repair one’s reputation in the eyes of police – and, perhaps, the social groups police are often thought to represent – reaffirming that one deserves to have, and should have, equal status in society.

Returning to our findings, when predicting resistance, we again found some unexpected results. We anticipated that when police posed a moral-democratic threat to participants in our sample that this would create more psychological distance between individuals and police, thus increasing their resistance toward police authority. We found the opposite conditional correlation in our multivariate model. Our results suggest that when police posed a threat to the moral-democratic-self, participants in our sample were less likely to resist the police, while those who perceived the police as legitimate were more likely to resist police. So why might threats to the moral-democratic-self have the opposite effect when predicting resistance as compared to disengagement discussed above? And why might legitimacy be positively associated with resistance? Here we suggest that examining the way that resistance is defined and measured in our study might help to shed light on these findings.

We measured resistance with items such as: ‘It is important that people lodge a formal complaint against disrespectful police behaviour’. On the other hand, disengagement is measured with items such as ‘I try to avoid contact with police at all costs’. Comparing these two measures of defiance, we can see that resistance represents a much more active and empowered form of defiance toward ‘bad’ policing that sits within the bounds of the legal process; a willingness to challenge what one sees as unacceptable police behaviour, but perhaps within the scope of a legitimate system. In this way, perceptions of legitimacy may be positively associated resistance because both legitimacy and resistance may indicate overall faith in the system (i.e. why make a complaint if the system is illegitimate?). In line with this reasoning, a threat to the moral-democratic self might reduce resistance – if a person feels police view them as a criminal, then they may feel locked out of the system and unable to raise a complaint or resist the police through legal channels. The motivation to resist, in the way we have defined it here, is thus diminished. These results highlight the issue of measurement in future studies that explore resistant defiance. To best understand the formation and impact of resistant motivational postures, measures should be broadened to incorporate types of resistance that fall within both legal (e.g. formal complaints against police) and illegal realms (e.g. illegal protests, violence).

Lastly, it should be noted that, given that our sample comprises first- and second-generation immigrants, it may be that these results are, at least in part, related to experiences (for first-generation immigrants) or vicarious experiences (for second-generation immigrants) connected to one’s country of origin (or one’s parent’s country of origin) (Wu et al. Citation2017, Jung et al. Citation2019). For example, for those immigrants who originate from (or whose parents originate from) non-democratic countries and/or countries that experience higher levels of police corruption, the inclination to defy or resist police may be dulled by past or vicarious experience of police. This may subsequently impact on the relationships between procedural injustice, identity threat, legitimacy, and defiant motivational posturing. As Tankebe (Citation2013) explains ‘dull compulsion’ to obey authorities is ‘commonplace under conditions of dictatorship and colonial rule where people acquiesce to those in power (that is, feel an obligation to obey them) but do not accord genuine legitimacy to them’ (see also Tankebe Citation2008). While it is not in the scope of this study to compare our theoretical model across immigrants’ country of origin, or to examine experiences with police in one’s country of origin, future research could examine the influence of such differences between different immigrant groups.

Conclusion

Although not exactly as we predicted, the results discussed above suggest that procedural injustice, identity threats and legitimacy can help us to better understand the dynamics of defiant motivational postures toward police in ethnic minority communities. Overall, our results offer several key takeaways that contribute to the growing body of research around police-minority group relations. First, we found that just as identity threats can encourage defiance, they can also discourage defiance. We found that even as a threat to the moral-democratic-self encouraged disengagement, it discouraged resistance in our sample. This finding suggests that when ethnic minority groups are treated by police as ‘suspect communities’ (Cherney and Murphy Citation2016) they may be less likely to stand up against police to make a complaint. While concerning, this is also, perhaps, unsurprising. The idea that police can, and do, oppress minority communities through over-policing and mistreatment is not new (for a discussion see Soss and Weaver Citation2017). Our findings have practical implications for police as they highlight the detrimental effect of biased policing and negative stereotypes that depict ethnic minority groups as ‘suspect communities’ (Cherney and Murphy Citation2016).

Second, at least in our sample, we found that perceived procedural injustice in policing was a strong predictor of both enhanced identity threats and defiance. Conversely, these results suggest that if police use procedural justice in encounters with ethnic minority group members, this has the potential to reduce perceived identity threats and defiance. These results have practical implications. Braithwaite (Citation2014) argues that adopting a dismissive, disengaged posture ‘is most difficult to address constructively because dismissive defiance (i.e. disengagement) places lawbreakers psychologically beyond the reach of influence of authority’ (Braithwaite Citation2014, p. 919). However, in contrast, our findings indicate that procedurally just police practice may, in fact, reduce disengagement, at least in the case of the ethnic minority communities surveyed in our research (although see Murphy Citation2021 for different findings).

Third, and as noted above, we find mixed results regarding the predictors of the two types of defiant motivational postures toward police. We note that these two types of defiance are quite different, with resistance representing the desire to stand up to police, and disengagement reflecting the desire to avoid and shrink away from police. Our findings further demonstrate the utility of exploring different types of defiance in studies of policing and as noted above, disaggregating different modes of resistant defiance (i.e. through legal or illegal means). Future research should further examine what factors explain ethnic minorities’ choice of active resistance (both lawful and non-lawful) versus avoidant disengagement to better understand how police can improve police-ethnic minority relations.

Lastly, our study points to the utility of expanding the process-based model and its affiliated Group Engagement Model to incorporate concepts such as identity-threat and defiance. While the process-based model is well tested, the Group Engagement Model has seen limited theoretical development over the past 20 years. Our study extends these models by incorporating notions of identity-threat and defiance drawn from Braithwaite’s (Citation2009, Citation2013) Theory of Defiance. Incorporating these concepts into one integrated theoretical framework may be particularly important to consider when seeking to understand negative experiences of policing it their consequences.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Of course, individuals can hold many different identities (e.g., woman, American, Muslim, etc.), and different identities can be triggered and expressed depending on the circumstance confronting an individual. Braithwaite’s theory alludes to how individuals identify themselves in response to authorities and/or regulators.

2 Gameplayers seek to exploit loopholes in laws to sidestep or compete with authorities. It is a posture that has been observed in white collar crime contexts (see Braithwaite, Citation2009). As such, it will not be discussed further in this paper.

References

- Alpert, G., and Dunham, R., 2004. Understanding police use of force: officers, suspects and reciprocity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Aquino, K., and Douglas, S., 2003. Identity threat and antisocial behavior in organizations: The moderating effects of individual differences, aggressive modeling, and hierarchical status. Organizational behavior and human decision processes, 90 (1), 195–208.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics . 2016. Community profiles. Available from: https://www.abs.gov.au/websitedbs/D3310114.nsf/Home/2016%20Census%20Community%20Profiles.

- Bradford, B., Milani, J., and Jackson, J., 2017. Identity, legitimacy and “making sense” of police use of force. Policing: an international journal, 40 (3), 614–627.

- Bradford, B., Murphy, K., and Jackson, J., 2014. Officers as mirrors: policing, procedural justice and the (re) production of social identity. British journal of criminology, 54 (4), 527–550.

- Braithwaite, V.A., 1995. Games of engagement: postures within the regulatory community. Law and policy, 17, 225–255.

- Braithwaite, V.A., 2009. Defiance in taxation and governance: resisting and dismissing authority in a democracy. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Braithwaite, V.A., 2013. Resistant and dismissive defiance toward tax authorities. In: A. Crawford, and A. Hucklesby, eds. Legitimacy and compliance in criminal justice. New York: Routledge, 91–115.

- Braithwaite, V.A., 2014. Defiance and motivational postures. In: G. Bruinsma, and D. Weisburd, eds. Encyclopedia of criminology and criminal justice. New York: Springer, 915–925.

- Braithwaite, V., Murphy, K., and Reinhart, M., 2007. Taxation threat, motivational postures, and responsive regulation. Law and policy, 29 (1), 137–158.

- Cherney, A., and Hartley, J., 2017. Community engagement to tackle terrorism and violent extremism: challenges, tensions and pitfalls. Policing and society, 27 (7), 750–763.

- Cherney, A., and Murphy, K., 2016. Being a ‘suspect community’ in a post 9/11 world: the impact of the war on terror on Muslim communities in Australia. Australian and New Zealand journal of criminology, 49 (4), 480–496.

- Cherney, A., and Murphy, K., 2017. Police and community cooperation in counterterrorism: evidence and insights from Australia. Studies in conflict and terrorism, 40 (12), 1023–1037.

- Cunneen, C., 2001. Conflict, politics and crime: aboriginal communities and the police. Oxon: Routledge.

- Davies, P.G., et al., 2002. Consuming images: how television commercials that elicit stereotype threat can restrain women academically and professionally. Personality and social psychology bulletin, 28 (12), 1615–1628.

- Davies, P.G., Spencer, S.J., and Steele, C.M., 2005. Clearing the air: identity safety moderates the effects of stereotype threat on women’s leadership aspirations. Journal of personality and social psychology, 88 (2), 276.

- Davis, R., and Mateu-Gelabert, P., 2000. Effective police management affects citizen perceptions. National institute of justice journal, 7, 24–25.

- Goffman, E., 1971. The presentation of self in everyday life. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

- Hough, M., Jackson, J., and Bradford, B., 2017. Policing, procedural justice and prevention. In: N. Tilley, and A Sidebottom, eds. Handbook of crime prevention and community safety. New York: Routledge, 274–293.

- Jung, M., Sprott, J.B., and Greene, C., 2019. Immigrant perceptions of the police: the role of country of origin and length of settlement. British journal of criminology, 59 (6), 1370–1389.

- Kahn, K.B., et al., 2017. The effects of perceived phenotypic racial stereotypicality and social identity threat on racial minorities’ attitudes about police. Journal of social psychology, 157 (4), 416–428.

- Kahn, K.B., McMahon, J.M., and Stewart, G., 2018. Misinterpreting danger? Stereotype threat, pre-attack indicators, and police-citizen interactions. Journal of police and criminal psychology, 33 (1), 45–54.

- Khondaker, M.I., Wu, Y., and Lambert, E.G. 2017. Bangladeshi immigrants’ willingness to report crime in New York City. Policing and society, 27 (2), 188–204.

- Madon, N.S., Murphy, K., and Sargeant, E., 2017. Promoting police legitimacy among disengaged minority groups: does procedural justice matter more? Criminology and criminal justice, 17 (5), 624–642.

- Major, B., and O’Brien, L.T., 2005. The social psychology of stigma. Annual review of psychology, 56, 393–421.

- McKernan, H., and Weber, L., 2016. Vietnamese Australians’ perceptions of the trustworthiness of police. Australian and New Zealand journal of criminology, 49 (1), 9–29.

- Meredyth, D., McKernan, H., and Evans, R., 2010. Police and Vietnamese-Australian communities in multi-ethnic Melbourne. Policing: a journal of policy and practice, 4 (3), 233–240.

- Murphy, K., 2013. Policing at the margins: fostering trust and cooperation among ethnic minority groups. Journal of policing, intelligence and counter terrorism, 8 (2), 184–199.

- Murphy, K., 2016. Turning defiance into compliance with procedural justice: understanding reactions to regulatory encounters through motivational posturing. Regulation and governance, 10 (1), 93–109.

- Murphy, K., et al. 2019. The Sydney immigrant survey: final technical report. Available from: https://blogs.griffith.edu.au/gci-insights/2019/08/30/the-sydney-immigrant-survey-final-technical-report-2/.

- Murphy, K., 2021. Scrutiny, legal socialization and defiance: understanding how procedural justice and bounded-authority concerns shape Muslims’ defiance toward police. Journal of social issues, 77 (2), 392–413.

- Murphy, K., et al., 2022. Building immigrants’ solidarity with police: procedural justice, identity and immigrants’ willingness to cooperate with police. British journal of criminology, 62 (2), 299–319.

- Murphy, K., and Cherney, A., 2012. Understanding cooperation with police in a diverse society. British journal of criminology, 52 (1), 181–201.

- Najdowski, C.J., Bottoms, B.L., and Goff, P.A., 2015. Stereotype threat and racial differences in citizens’ experiences of police encounters. Law and human behavior, 39 (5), 463–477.

- O’Brien, J., 2011. Spoiled group identities and backstage work: a theory of stigma management rehearsals. Social psychology quarterly, 74 (3), 291–309.

- Oliveira, A., and Murphy, K., 2015. Race, social identity, and perceptions of police bias. Race and justice, 5 (3), 259–277.

- Piatkowska, S.J., 2015. Immigrants’ confidence in police: do country-level characteristics matter? International journal of comparative and applied criminal justice, 39 (1), 1–30.

- Radburn, M., et al., 2018. When is policing fair? Groups, identity and judgements of the procedural justice of coercive crowd policing. Policing and society, 28 (6), 647–664.

- Ryan, L., 2010. Becoming Polish in London: negotiating ethnicity through migration. Social identities, 16 (3), 359–376.

- Ryan, L., 2011. Muslim women negotiating collective stigmatisation: ‘we’re just normal people’. Sociology, 45 (6), 1045–1060.

- Sargeant, E., et al., 2016. Social identity and procedural justice in police encounters with the public: results from a randomised controlled trial. Policing and society, 26 (7), 789–803.

- Sargeant, E., Davoren, N., and Murphy, K., 2021. The defiant and the compliant: how does procedural justice theory explain ethnic minority group postures toward police? Policing and society, 31 (3), 283–303.

- Soss, J., and Weaver, V., 2017. Police are our government: politics, political science, and the policing of race–class subjugated communities. Annual review of political science, 20, 565–591.

- Steele, C.M., 1997. A threat in the air: How stereotypes shape intellectual identity and performance. American psychologist, 52 (6), 613.

- Sunshine, J., and Tyler, T.R., 2003. The role of procedural justice and legitimacy in shaping public support for policing. Law and society review, 37 (3), 513–548.

- Tabachnick, B., and Fidell, L., 2001. Using multivariate statistics. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

- Tankebe, J., 2008. Police effectiveness and police trustworthiness in Ghana: an empirical appraisal. Criminology & criminal justice, 8 (2), 185–202.

- Tankebe, J., 2013. Viewing things differently: the dimensions of public perceptions of police legitimacy. Criminology, 51 (1), 103–135.

- Tyler, T.R., 1990. Why people obey the law. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Tyler, T.R., and Blader, S.L., 2003. The group engagement model: procedural justice, social identity, and cooperative behavior. Personality and social psychology review, 7 (4), 349–361.

- Van Craen, M., 2012. Determinants of ethnic minority confidence in the police. Journal of ethnic and migration studies, 38 (7), 1029–1047.

- Wu, Y., Smith, B.W., and Sun, I.Y., 2013. Race/ethnicity and perceptions of police bias: the case of Chinese immigrants. Journal of ethnicity in criminal justice, 11 (1-2), 71–92.

- Wu, Y., Sun, I.Y., and Cao, L., 2017. Immigrant perceptions of the police: theoretical explanations. International journal of police science & management, 19 (3), 171–186.