ABSTRACT

The number of civilian crime investigators (CIs) has been increasing among the police, a trend that is called civilianisation. However, conflicts have arisen from perceptions that civilian CIs undermine professional police efforts. The purpose of this study was to investigate the intersection of doing gender and professional identity in narratives on inclusion and/or exclusion in CIs’ professional practices. Because professional background and gender composition change with the civilianisation of the police, this study included interviews with 48 female CIs from Sweden. The study showed that aspects of belongingness and uniqueness interact in complex ways and conclude that the intersection of being a civilian CI and a woman is at the core, especially in narratives on exclusion. Taken together, this means that civilian CIs’ narratives are important to learn from and can help the police become aware of obstacles to and opportunities for civilian employees’ full participation in the criminal investigation practice. Aspects of belongingness and uniqueness are discussed to contribute knowledge of how gender and professional identity can be redone in a way that helps reduce future barriers to full inclusion of female and civilian CIs in police work.

Introduction

This article contributes knowledge on how inclusion and exclusion of female civilians in police organisations can be understood as a complex phenomenon. The number of civilians is increasing in police organisations in many countries, as in Sweden, a phenomenon called civilianisation of the police (King Citation2009, Kiedrowski et al. Citation2019, Rice Citation2020). It is claimed that civilians contribute new competencies to increasingly specialised investigation work in, for example, domestic crimes, eco-crimes, and cybercrimes (Liederbach et al. Citation2011). Additionally, beyond specialisation, another motive for civilianisation is to solve staffing and workload issues caused by a shortage of warranted police officers (Rice Citation2020).

With increased complexity in investigation work, the lack of police officers, and a need to prioritise visibility of warranted police on the streets, the mandate for civilians has expanded, and they now complete tasks that were previously classified as police work, including criminal investigations (King Citation2009, Kiedrowski et al. Citation2019, Rice Citation2020, Swedish Police Authority Citation2022). However, the integration of civilians into the police has proven problematic. Studies have shown that civilians experience low levels of support, feel overlooked as second-class employees, and feel excluded from the police community (King Citation2009, McCarty and Skogan Citation2013). Conflicts have arisen from perceptions that civilians undermine police professionalisation efforts and reduce the profession’s status (Morrell Citation2014). In Sweden, civilianisation has taken an even more pervasive turn, where civilians are hired as crime investigators (CIs), rather than to analyst or intelligence roles.

Thus, this kind of civilianisation of the police can also result in ‘task tipping’ and feminisation (Jacobsen Citation2007), referring to when a profession or field of work performed by a certain group of employees (e.g. police-trained men) is increasingly switched over to execution by another group of employees (e.g. civilian women). The gender balance of the police organisation changes with civilianisation, as a higher proportion of women are employed. Consequently, because the police traditionally have been male-dominated and characterised by a masculine professional culture (McCarthy Citation2013, Haake Citation2018), the shift towards employing more civilian women can contribute to the perception that investigative work is not considered real police work (Rabe-Hemp Citation2009). This development can lead to organisational contradictions, not the least based on the intersection of potential de-professionalisation (gradually less need for police-trained staff) and gender tipping (towards more female employees), which could affect work status and power relations. For instance, the Swedish Police Authority (Citation2018) has stated that contradictions and questions remain about civilians’ mission and necessity. In this study, we trace such contradictions in an analysis of female civilian CIs’ narratives of inclusion and exclusion in police organisations.

In studying the doing of gender (West and Zimmerman Citation1987, Citation2009, Kelan Citation2010, Citation2018) and professional identity (Pratt et al. Citation2006, Slay and Smith Citation2011), using an intersectional perspective is relevant (Acker Citation2006, Lykke Citation2010). With this approach, it is possible to study how being a civilian (not police) woman (not man) appears in narratives of inclusion and exclusion in police investigations.

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to investigate the intersection of doing gender and professional identity in narratives on inclusion and/or exclusion in CIs’ professional practices. By using the framework of Shore et al. (Citation2011) in performing the analysis of inclusion/exclusion, we contribute to the research field with a deeper understanding of the phenomenon by considering more complex positionings – from inclusion (via differentiation or assimilation) to exclusion. Adding the perspectives of doing gender and professional identity to this analysis is novel and has not previously been carried out in police research. This intersectional approach is a much-needed complement to more one-dimensional studies of civilianisation or feminisation.

Overall, our study adds relevant knowledge about police practice and reveals important aspects of police culture that can help police authorities meet the professionalisation and equalisation challenges that can result from civilianisation. We show that aspects of belongingness and uniqueness interact in complex ways that can result in both feelings of inclusion and exclusion. Based on these findings, the police can become aware of obstacles to and opportunities for civilian employees’ full participation in the criminal investigation practice, improve civilian employees’ introduction and career opportunities, and establish a gender-equal work organisation and a sustainable and just working life.

Being a civilian in the police

Police organisations work under unique conditions and challenges. To enhance their ability to solve crimes, increase the number of police officers visible on the streets, and contribute to the flexibility of operations, civilians have been employed with one main motive: the addition of specialised skills (King Citation2009, Alderden and Skogan Citation2014, Whelan and Harkin, Citation2021). With increasing civilianisation, barriers have been identified in international research to the incorporation of civilian employees into police organisations, such as judicial restrictions that prevent civilians from performing certain tasks. Cultural barriers have also been identified in the reception of civilian staff, with the warranted police being described as reluctant to accept their civilian colleagues as ‘full partners’ and to trust them to perform work police officers previously performed (Rice Citation2020). All in all, this reluctance has been explained as a reason for increased staff turnover and illness among civilian CIs (McCarty and Skogan Citation2013, Alderden and Skogan Citation2014, Kiedrowski et al. Citation2019).

Relationships in the workplace differ depending on whether the employee has a civilian or police background. In a study of the interactions between police officers and civilian intelligence analysts in Scotland, Atkinson (Citation2017) concluded that ‘civilian police staff, having never ‘served their time’ on the street, cannot fully participate in police culture’ (p. 235) and that they are infantilised through forms of hegemonic masculinity and patriarchy. The study also described how infantilisation occurs because civilian staff lack the required professional background and thus habitus. A distinct expression of this problem was shown in the extent of various staff groups’ social support from colleagues and leaders, with warranted police officers more likely to express that co-workers and those of higher rank were supportive and ‘had their back’.

Rowe et al. (Citation2023) highlighted how uniforms, badges, and related artefacts also form a material policing culture that influences police’s professional identity of belonging, loyalty, and being part of the ‘family’. This material culture, exclusive to warranted police officers, made it difficult to recognise the authority and formal hierarchical positions of civilian staff, which some civilians saw as problematic. These examples reflect the warranted police ranks’ traditional solidarity, whereas civilians’ professional identities are those of outsiders (McCarty and Skogan Citation2013). This argument has also proved relevant in the Swedish context. A review of the organisational culture of the Swedish police contained descriptions of an us-and-them culture characterised by different views and values depending on whether an employee was civilian or warranted police and male or female (Swedish Police Authority Citation2019).

Research has also shown various success factors for the incorporation and inclusion of civilians into police organisations. The factors that contribute to civilian-employee satisfaction in the workplace are satisfaction with salary and benefits, low levels of work-related stress, equality in the workplace, and a sense of acceptance (Alderden and Skogan Citation2014). Rice (Citation2020) stated that civilian CIs move towards roles as equal partners and described police and civilians as having equal status when the civilians’ work experiences and previous education are highly valued. The study also showed that over time, civilian CIs have taken on new roles and tasks in addition to an initially assistive or supportive function and are approaching an equal distribution of responsibilities, tasks, and participation in relation to their police colleagues.

Civilianisation has also been highlighted as an opportunity to make police organisations more diverse and heterogeneous (Alderden and Skogan Citation2014, Kiedrowski et al. Citation2019), partly because civilians’ contributions differ from traditional police officers’ skills, adding something unique to the work (Rice Citation2020).

Being a woman in the police

Research has shown that women’s entry into male-dominated occupations can lead to a division of labour that separates female – and male-coded working areas (Rabe-Hemp Citation2009). Labour is divided horizontally in police organisations: Women complete ‘softer’ and caring tasks associated with lower levels of prestige and in family, social, and administrative areas, whereas men work more with ‘hard’ and daring tasks believed to require courage and strength (Fejes and Haake Citation2013, McCarthy Citation2013). This labour division can contribute to limitations in perceived opportunities for civilian women and men (especially civilian women) given work in areas of investigative activity with lower status and tasks that are not considered real police work (Rabe-Hemp Citation2009).

In previous studies, researchers have shown that women in the police face career problems usually described as part of the macho police culture (c.f. Chaiyavej and Morash Citation2009). Silvestri and Tong (Citation2022) described the exclusion of women from leadership in the police and discussed the associated formal and informal barriers, which included stereotyping, discrimination, obstruction, prejudice, and patronage. Keddie (Citation2022, p. 13) contributed to the discussion on how to support gender equality reform in the police by suggesting removing political, cultural, and economic obstacles in the context of organisational justice. In this way, ‘transforming the hierarchical and masculinised cultures that exacerbate gender inequality will be more possible’.

In a Canadian study, gender arose in discussions about the ideal police officer as someone displaying masculine traits. Further, male police officers did not talk about the caregiving aspects of police work, and women’s work was believed to have lower status. Gender inequality was also hidden in the work organisation and in policies (Murray Citation2021). Women have been socially excluded from police imagery, such as advertisements. Until recently, and maybe still, women have not been visible in crime-fighting imagery; instead, they are portrayed in lower-ranking positions, such as caretakers or nurturers (Rabe-Hemp and Beichner Citation2011). Additionally, being pregnant and giving birth positions female police officers as ‘the other’, leading to the belief that they must balance femininity with masculinity to be valued, taken seriously, and included as officers (Langan et al. Citation2019). Therefore, the body is not neutral in doing gender at work (c.f. Lindberg et al. Citation2017).

Research on patterns and underlying reasons for gender segregation and gender inequality in the police show that the occupational macho-oriented culture reinforces gender binaries. For instance, ‘daring’ discourse on police work has constructed men as brave, unafraid, strong, and thrill-seeking, thus further dividing tasks and definitions of high status in the police according to gender (Fejes and Haake Citation2013, Haake Citation2018). Similarly, Haake et al. (Citation2017) showed that female police leaders had to draw on culturally stereotypical images of leaders and showcase caring and daring natures to appear credible and gain acceptance. In Kurtz and Upton’s (Citation2018) study, ‘war stories’ were highlighted as shaping the masculine police culture. In stories of everyday work in the police organisation, male police officers told stories about acting macho, being unafraid, and showing no feelings. Men told these stories for other men, and if women participated, they only listened. A core story of a woman police officer failing because she was not strong enough was told and retold in various ways (Kurtz and Upton Citation2018). This sort of storytelling reproduces masculinity as a core value in police culture.

The intersection of being a woman and a civilian in the police

Being both a woman and a civilian can add to the problem of exclusion, according to previous research. For example, according to Kiedrowski et al. (Citation2019), one source of perceived marginalisation among civilian CIs is gendered professional culture exclusion, which can result in changing gender structures, gender-based divisions of labour, and job statuses (Acker Citation2006, Fejes and Haake Citation2013, McCarthy Citation2013, Haake Citation2018). In a study of the police’s organisational culture that was conducted by following police community support officers who were civilians, Cosgrove (Citation2016) found the police’s organisational culture dominant and masculine. The women stated that to a large extent, they needed to pursue and tolerate masculine values and sexist attitudes to develop relationships and create opportunities for careers in the police organisation. To be fully incorporated and accepted, the civilians in the study felt that they needed to embrace the dominant masculine culture (Cosgrove Citation2016). The Swedish Police Authority’s (Citation2019) empirical examination of the organisational culture also revealed that the work areas civilians and women dominated were characterised by lower status, whereas the work areas police officers and men dominated were described as attractive and given higher status.

Based on existing research, the intersection of being a woman and a civilian CI seems to present challenges to be addressed in police organisations. By analysing female civilian CIs’ narratives on inclusion and exclusion in the work setting, we can contribute knowledge that helps police organisations become just and gender-equal, where various professional groups can work together on equal terms for the common good.

Research theory and methods

As a point of departure, we have a practice theory understanding of gender and professional identity. Therefore, the introduction of civilian CIs is viewed as a process of gaining participation in a practice and the workplace as a site where practitioners are socialised into the norms of a work practice (Billett Citation2006). To meet the need for specialisation and staffing challenges regarding handling a larger workload in the Swedish police (Brå Citation2016), civilian CIs have grown in number, authority, and responsibility. Between 2019 and 2020, the number of external recruitments of civilians increased by 23%. However, the gender balance of civilian CIs in Sweden differs greatly from that of police officers, with the majority of CIs being women (68% of civilians vs. 34% of police officers; Swedish Police Authority Citation2022).

Because professional background and gender composition of the work force change with civilianisation of the police, we conducted this study from an intersectional perspective (Acker Citation2006, Lykke Citation2010) on ‘doing/undoing’ gender (West and Zimmerman Citation1987, Citation2009, Kelan Citation2010, Citation2018) and professional identity (Pratt et al. Citation2006, Slay and Smith Citation2011).

From the doing-gender perspective, gender is not seen as predefined. Rather, gender is viewed as a practice, something people do in social interaction (West and Zimmerman Citation1987, Shields and Dicicco Citation2011). Thus, ideas about gender are constructed and reproduced in societal and organisational cultures, structures, and practices (Gherardi Citation1994, Martin and Collinson Citation1999). With an understanding of how gender is done in specific contexts, researchers can also answer questions of how gender can be undone (made uninteresting) or redone (comprising other, non-stereotypical gender attributes and behaviours; Kelan Citation2010, Morash and Haarr Citation2012, Patterson et al. Citation2012, Kelan Citation2018, Torres et al. Citation2019).

Professional identity relates to ‘what you do’ (Pratt et al. Citation2006) and is defined as the constellation of attributes, beliefs, and values people use to define themselves in specialised, skill – and education-based occupations or vocations (Ibarra Citation1999). Professional identity is the result of the socialisation process and discourses regarding the meanings associated with a profession. It is influenced by work experiences and career transitions (Slay and Smith Citation2011); signals collective norms, rules, and values; and provides symbols and social rituals specific to the group (Bayerl et al. Citation2018). Thus, with narratives of inclusion and exclusion from female civilian CIs, we can analyse the doing of both gender and professional identities among police.

Conducting the study

We recruited Swedish female civilian CIs for this study in two ways: (a) by providing information at a university led introductory course for civilian CIs on two occasions and (b) by providing information on the national Swedish police intranet web page. On the course, participants were recruited by filling out a form where they expressed interest to participate. The intranet information contained an email address where participants contacted us directly. In the end, we interviewed all participants that expressed interest to participate. This led to participants representing civilian CIs from the north to the south of Sweden. The study was based on 48 interviews with female civilian CIs, most of whom had higher-education degrees and experience in social work, criminology, law, political science, psychology, or other behavioural sciences. Of these civilian CIs, 17 were working within volume crime, 16 in domestic and youth crimes, five in serious crimes, four in white-collar crimes, and six in special units such as cyber-crime, environmental crime, and work environment violations. Unlike in some countries, cyber-crime is largely handled by special units rather than being part of volume crime in Sweden.

According to the Swedish Ethical Review Authority, this research does not fall within the ethical legislation as we do not collect or process any sensitive personal data. The study thus meets the national guidelines regarding research ethics requirements. Before collecting data, we obtained informed consent from all participants, in beforehand or at latest at the start of each interview. Thereafter, with the help of two research assistants, we conducted interviews during the years 2020–2021. We conducted the interviews via Zoom, Skype, or telephone, and they lasted 45–90 min. We asked questions about everyday work as a civilian CI, the introduction to work, the organisational hierarchies and cultures, and thoughts about the future and career opportunities. We recorded the interviews and transcribed them verbatim before conducting analyses.

We started by coding passages of inclusion/exclusion in the interviews in relation to (a) descriptions of being a civilian CI or (b) descriptions of being both a civilian and woman CI. We completed the coding in NVivo (Version 12). We then made distinctions between shorter notions about inclusion or exclusion and fuller narratives with beginnings, middles, and ends (Freeman Citation2015) that were possible to analyse according to the framework of Shore et al. (Citation2011). We therefore excluded the shorter notions and further analysed the fuller topical descriptions (Riessman Citation1993), which were narratives about specific moments in which being a woman and/or a civilian CI affected whether the person felt included or excluded at work. The use of semi-structured interviews was well-suited for this analysis.

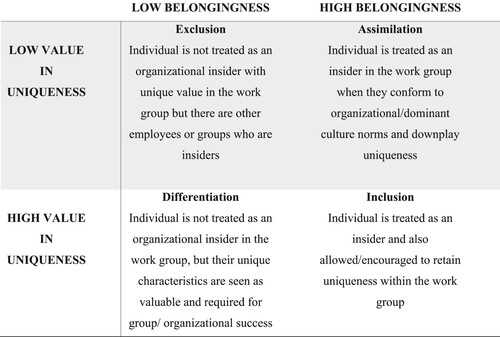

In the next step, we categorised all narratives into four categories according to the framework of Shore et al. (2011; see ). Shore et al. (Citation2011) reviewed research on inclusion and exclusion in work groups and found that many researchers in previous studies either talked about inclusion/exclusion in relation to the feeling of belongingness or in relation to the feeling of bringing something unique to the work group. Only a few definitions contained of both these aspects. Their conclusion was that both dimensions were needed to be able to talk about being fully included or excluded, and therefore, both are included in their framework (see ). In this study, we used this more elaborate framework to bring forth and contribute a deeper and more complex understanding of inclusion and exclusion of female civilian CIs in the police. Thus, in this phase, we only analysed narratives that were based on expressions of both belongingness and uniqueness. By doing so, descriptions of inclusion and exclusion also could signal something in between, such as assimilation or differentiation.

Figure 1. Framework for Analysis (Based on Shore et al., Citation2011).

The last step of analysis was the visualisation of the themes of uniqueness and belongingness in each of the four categories, exclusion, assimilation, differentiation, and inclusion. In the following results presentation, quotations from the interview narratives are followed by numbers 1–48 that we assigned each participant, together with the type of investigation unit. The quotations are translated from Swedish and corrected for grammar.

Findings

Overall, the study material included more narratives describing exclusion than inclusion of female civilian CIs in the police. Some of the female civilian CIs talked about both inclusion and exclusion (or differentiation and assimilation), which often changed over time, with narratives on exclusion often preceding those of inclusion. The intersection of being a woman and civilian CI were found primarily in narratives of exclusion, where about half of the research participants shared experiences in which gender (being a woman) intersected with being a civilian. We found no clear patterns that belonging to a special type of criminal investigative unit would affect what kind of descriptions of inclusion/exclusion the participants had, other than that there were many working in serious crimes that expressed narratives about differentiation. These small differences could be due to that many of the civilian CIs also had moved between different investigative units, and therefore referred not only to their latest position.

Below, we describe each of the four categories, from inclusion via assimilation or differentiation to exclusion, according to Shore et al. (Citation2011) together with key themes from the narratives (see for an overview). We also support the descriptions with quotations.

Table 1. Key themes for the categories of inclusion, assimilation, differentiation, and exclusion.

Narratives on inclusion

In narratives on inclusion, both gender and professional identity could be undone/redone in non-traditional ways. We found narratives with descriptions of inclusion from about one out of five research participants. A few, beyond relating this to being of other professional backgrounds, particularly highlighted the female gender as part of being included. Narratives of inclusion showed expressions of high belongingness in the work group and a valuation of the uniqueness of civilian CIs’ according to their specific competencies/professional backgrounds. Regarding belongingness, almost all narratives included the participants being self-evident parts of their work groups and highlighting feelings of fellowship, openness, respect, inclusion, and well-being. For example, some of the narratives included descriptions of being part of a family who was well taken care of. Many of the narratives also concerned being appreciated, being listened to, garnering interest, or gaining trust. A third theme the narratives often included was civilian and police CIs working together, with a balance of both groups and with no sense of ‘us and them’. Here, the participants stated they were working together towards a common goal.

Narratives on inclusion also contained descriptions of high uniqueness. Most of these narratives described that civilian CIs contribute competencies and knowledge that police CIs lack. Here, the participants described their specific educational backgrounds and university degrees in behavioural sciences, social sciences, law, and criminology (among many other areas) as unique and highly valued in their work. They mentioned the usefulness of various professional backgrounds and enjoyed the best of two worlds. Some also mentioned that even police CIs talked about the need for more civilian CIs. Additionally, the narratives often depicted civilian CIs being capable, with various strengths, valuable competencies, and cleverness. A third theme in many of the narratives on inclusion was police CIs learning from civilian CIs. The police CIs wanted to make use of the civilian CIs’ competencies and ask them about how to complete tasks better at work.

In one narrative on inclusion, the female civilian CI expressed belongingness related to a sense of being appreciated and a self-evident part of the work group, and expressed uniqueness by sharing examples of feeling capable, contributing competencies, and the willingness from police CIs to learn from her.

They are police officers, but they have always been very respectful … I have felt that I have valuable knowledge since I have this work environment background. They ask me questions, they respect me, and they are very … very good. You feel appreciated. They are like this towards everyone in the group. It’s like no one feels left out or like that just because you are civilian, you would be less worthy. I have never felt that in this group. (13, Work environment crimes)

Another example of full inclusion was the following:

On the contrary, our knowledge is asked for. Two of the people here who were hired at the same time as me are criminologists. Colleagues have found it very exciting. They think it’s super fun that we come in with other experiences. We have a lot of discussions just around the coffee tables based on our experiences. We are asked what we think about things, and like … ‘You who are educated in psychology, what do you think about this person?’ There is an interest here, to listen to us … I am here because I have an experience that is interesting to the police. I feel it. I believe that in general. I think it’s great overall, the mix. (23, Volume crimes)

Narratives on differentiation

Descriptions of differentiation were not as common as the other categories, but were shown in narratives by about one out of six research participants. Almost all of these narratives were in relation to female civilian CIs’ professional backgrounds, and only one highlighted the intersection with gender aspects. Narratives on differentiation included expressions of low belongingness to the work group but high valuation of civilian CIs’ specific competencies and professional backgrounds (uniqueness). The participants in most of these narratives described high uniqueness regarding civilian CIs being treated as capable, having valuable competencies and experiences, and being very efficient and driven at work. They also mentioned elements such as having authority and high self-confidence. Some narratives contained descriptions of a phase in which civilian CIs first were tested and had to prove their knowledge. After passing that test, they gained high credibility or appreciation. Additionally, a few narratives were about civilian CIs moving into leadership positions and making a career with support from a manager.

At the same time, these narratives included descriptions of low belongingness. The most often mentioned theme was negative attitudes towards civilian CIs. They were exposed, had to work harder, and were tested to a larger extent. Some of the participants also mentioned negative attitudes towards civilian CIs fulfilling a career or earning higher salaries than police CIs. Several narratives contained passages mentioning esprit de corps among police CIs as a barrier to civilian CIs’ acceptance into the group. The police CIs formed strong groups and accepted each other because they are all warranted police officers, whereas the civilian CIs were talked about as being more individualistic.

Below is an example of both prosecutors and managers expressing the high capability (theme of uniqueness) of civilian CIs, while they face negative attitudes and thereby low belongingness.

Several prosecutors that I’ve been in contact with, they ask, ‘You’re a civilian huh?’ ‘Yes, I am’. ‘You guys are very good’. Prosecutors think civilian employees are a bit more rigorous. My boss has also said that the police employees are afraid because they know that civilians are usually such good investigators, so that’s why they are this way [negative]. (24, Domestic crimes)

Narratives on assimilation

We found many expressions of assimilation of civilian CIs in the narratives. About one out of three research participants articulated this, one in intersection with being of female gender. Narratives on assimilation included expressions of high belongingness in the work group but low valuation and downplaying of the civilian CIs’ specific competencies/professional backgrounds (uniqueness). The narratives contained three recurrent themes on high belongingness. The most common one was being a self-evident part of the work group. These participants talked about a positive climate in which they could thrive and felt welcomed, positively treated, and well taken care of. Someone even said they were so much a part of the police group that they contributed to gossiping about civilian CIs at other units. Another common theme was being appreciated, which included being listened to and respected and gaining trust. A third theme was gaining acceptance if resembling police CIs from managers, colleagues, or the surrounding society if people thought they were warranted police officers or were about to become police officers.

For narratives to be included in the assimilation category, they had to include passages about feelings of low uniqueness or the downplaying of uniqueness. The most common of the three themes of low uniqueness was appearing like warranted police CIs. These participants tried to resemble the police CIs by avoiding presenting themselves as civilian CIs, for example, by wearing a uniform that looked very much like the ones warranted police officers wore or supporting a policy allowing all officers in the unit to dress in civilian clothes. In this way, they blended in at work and in how they interviewed victims or interrogated perpetrators. Another way they could blend in was by obtaining a function-oriented education to become police officers; civilian CIs with at least a bachelor’s degree, some years of investigative work, and support from management could do this during work hours and maintain their normal salaries. This was the ultimate way of becoming like the warranted police officers. The only narrative containing gender aspects (above being civilian) in the assimilation category concerned women entering the police ‘for real’ by taking advantage of this educational opportunity.

Another theme of downplaying uniqueness was maintaining a low profile to avoid standing out. These participants limited themselves, did not step on anyone’s toes, or handed over situations to warranted police CIs even though they could have handled the situation well themselves. Another common theme in the female civilian CIs’ descriptions was police CIs’ notions of civilian CIs lacking the right competencies for their work. These narratives included descriptions of a lack of interest in or understanding of the civilian CIs’ valuable competencies and potential contributions.

In the female civilian’s quote below, assimilation is articulated in relation to gaining acceptance and being appreciated (high belongingness) when appearing like warranted police CIs (low uniqueness).

I just think, if you are a civilian, you just need to be confident that you are. And then you notice no problems or no differences. I know I was up in [city X] and, as a civilian, got a police group with me that would pick up a person. And after I had given instructions for everything and made action plans and introduced myself as an interrogation leader or task leader, I ended it all by saying, ‘I am a civilian’. Then many became very positive and became very, ‘Oh, what fun. How good you are’. So, I noticed that if I did not, if I had put it [being a civilian CI] first, maybe half would have stopped listening, but I put it last and got very, very positive reactions. So, you can be a little bit smart, too. (12, Domestic crimes)

Narratives on exclusion

In narratives on exclusion, professional identity and often gender were done in traditional ways. More than half of the female civilian research participants shared one or more examples of exclusion, many of them being intersectional and highlighting exclusion in relation to being both civilian and woman. Narratives on exclusion described low belongingness to the work group and low uniqueness via low valuations of civilian CIs’ competencies and professional backgrounds.

Exclusion due to other professional backgrounds than being warranted police – that is, being a civilian CI – appeared in many narratives. Low belongingness was shown by negative attitudes towards civilian CIs in almost all these narratives. This concerned police colleagues and sometimes managers treating civilian CIs badly. The research participants faced resistance and were unappreciated, treated condescendingly, dismissed, despised, or neglected. They were also not seen, heard, or confirmed but were expected to show gratitude. In addition, they needed to work harder, be tougher, and perform better than police CIs. Some participants balanced these negative elements by stating that it is not like this everywhere; such behaviour varies and can be better or worse in various units. A second often-mentioned theme in the narratives was the division between police and civilian CIs, stemming from an us-and-them culture in which civilian CIs are lonely, odd birds, made to feel different, and excluded from the community. These narratives also concerned police CIs not wanting to work with, cooperate with, or help civilian CIs.

Low uniqueness appeared in the narratives via three themes. Many descriptions contained aspects of civilian CIs lacking the right competencies, which was made apparent with questioning, making competencies invisible, or showing that civilians’ professional backgrounds were uninteresting, not good enough, or of low status. Some participants pointed out what they could not do or were not allowed to do at work and that they had negative experiences. Some narratives also concerned police CIs opposing civilian CIs, specifically police CIs and the police union counteracting civilian CIs. They sometimes did not want any more civilian CIs, wanted fewer CIs, or wanted to hire more CIs with the ‘right’ (police) backgrounds. The last theme was maintaining a low profile to avoid standing out. Civilian CIs talked about being good, or rather ‘too good’, at work or earning too high a salary, which police CIs did not appreciate. The civilian CIs were then treated as show-offs and needed to constrict themselves to be accepted.

In the following quote, low belongingness is shown by the civilian CI describing negative attitudes towards civilian CIs and a division between them and police CIs. When it comes to uniqueness, the research participant articulated civilian CIs lacking the right competencies to be part of the work family and a need for maintaining a low profile, something this person did not like doing.

You should probably be fairly humble in the beginning, and that’s also something that can annoy me a little sometimes … you shouldn't come here and think you’re something without having worked your way up, or at least proven that you can do this. And it also means that as a civilian, my background is very rarely referred to. I think I know a lot; I’ve still worked for about 20 years now and have my profession and my background and my experiences, but it’s rarely asked about … and I think I probably share that with the other civilians. We’ve mumbled a bit about it in the coffee room, as I told you before … It sometimes boils down to Adam [designated name, civilian crime investigator] having to make PowerPoint presentations to police officers who can’t do it themselves, just because he used to be a systems developer, you know … a police officer instead, number one, tells you when he/she graduated from the police academy, number two, all the places he/she has worked at, and then that person is suddenly one of the work family … (11, Traffic crimes)

If you do not fit in, it can probably be a bit difficult, and there is still some resistance today. I think quite a few would say outright that they do not think civilians should be employed … But it’s like this, anyway, that you might be measured from a different yardstick in some way, that you have to show, that you have to be better than the police; otherwise, you are bad. So that if there is a civilian … who is not so good, yes, but then it will be ‘Now we do not employ any more civilians’. So, I think it’s very – you have to be a little adaptable and also understand that you can’t come and point out everything you think is wrong with the police authority because then you will not last long. You have to be able to adapt, as well. I do my job, and then all this that does not work, that I can’t do anything about, I just have to let it be. (31, Serious crimes)

Below, one research participant described being excluded as a female civilian CI by highlighting the macho jargon and the devaluation of the female gender (low belongingness), together with the feeling of lacking the right professional background (low uniqueness), i.e. being a civilian.

Yes, but it [the macho culture] still lingers on quite a bit. So, it’s a bit of both. I have actually been called a ‘little girl’ once by an old man [at work]. But it is probably one of the exceptions. I think many people at least know what is politically correct or not, what they are allowed and not allowed to say. I think that many people, deep down, think that you have less right to be here because you are a young civilian and a woman. I do not think you have any advantage from that. But no one expresses it … Rather, perhaps the opposite is true, that you may instead exaggerate that you do not see any difference between police and civilians, although you may actually show that in action. (10, Serious crimes)

Discussion and implications

International research has concluded that civilians experience low levels of support, feel overlooked and excluded from the community of police culture, and are accused of reducing the status of the profession (Loftus Citation2008, King Citation2009, McCarty and Skogan Citation2013, Morrell Citation2014, Rowe et al. Citation2023). Similarly, the Swedish Police Authority (Citation2018) has stated that contradictions and questions about civilian CIs’ mission and necessity exist, and that staff turnover is much larger in that group.

In this study, we investigated the intersection of doing gender and professional identity in narratives on inclusion and/or exclusion in CIs’ professional practices. For this, we used the framework by Shore et al. (Citation2011) and analysed narratives describing exclusion, differentiation, assimilation, and inclusion – depending on if the narratives showed high or low feelings of belongingness and uniqueness.

Turning to an intersectional outlook on gender and professional identity, we conclude that these two categories are intertwined in an interesting way. While there are several reported difficulties related to gender and inclusion, our results show that professional identity influences processes of inclusion and exclusion to an even larger extent. We therefore propose that differentness in doing gender can be downplayed and made subservient to stronger social categories – in this case the police/civilian divide. One explanation to why the civilian/police divide might come out as more pervasive can be that the Swedish police already have a large proportion of female warranted police officers and has also worked with gender issues over a long period of time. The ‘new’ and threatening to status quo in the organisation is therefore not primarily ‘women’, but ‘civilians’. However, being different to the norm by being both a civilian and a woman may enhance processes of exclusion in the police. In all, this observation also highlights the importance of an intersectional perspective on questions on inclusion and exclusion in work practices.

Thus, we conclude that aspects of belongingness and uniqueness interact in complex ways and that the intersection of being a civilian CI and a woman is at the core, especially in narratives on exclusion. Taken together, this means that civilian CIs’ narratives are important to learn from and can help the police become aware of obstacles to and opportunities for civilian employees’ full participation in the criminal investigation practice. Therefore, aspects of belongingness and uniqueness will be discussed to contribute knowledge of how gender and professional identity can be redone in a way that helps reduce future barriers to full inclusion of female and civilian CIs in police work.

Belongingness

Aspects of belongingness that are important to consider when aiming for gender and professional equity include creating a work environment where female civilian CIs are not ridiculed, made uninteresting, or devalued and where macho jargon is mitigated. This could help reduce gendered professional culture exclusion (Chaiyavej and Morash Citation2009, Haake Citation2018, Kiedrowski et al. Citation2019) and an organisational culture in which work areas dominated by civilians and women receive lower status (Swedish Police Authority Citation2019).

Additionally, negative attitudes, ‘esperit de corps’, and the division of civilian CIs and police CIs in an us-and-them culture are barriers for civilian CIs to be included at work and contribute to a sense of low belongingness to the work group. These kinds of barriers and boundaries need be brought to light to enable change (McCarty and Skogan Citation2013, Atkinson Citation2017, Swedish Police Authority Citation2019, Rowe et al. Citation2023).

From narratives on high belongingness, we learned that civilian CIs being treated as self-evident parts of their work groups, being respected and appreciated, and working together with, not alongside, police CIs leads to feelings of inclusion. These aspects are also targeted by Alderden and Skogan (Citation2014) and Rice (Citation2020) as important for a just and equal work practice.

To conclude, crucial to achieving a police organisation in which female civilian CIs feel that they belong is to work with the traditional male police organisation culture and to find ways civilian and police investigators can come together and collaborate on equal terms. In this way, both gender and professional identity can be redone.

Uniqueness

Furthermore, feelings of uniqueness are of importance to be fully included at work (Shore et al. Citation2011). The feeling and reminder that one may lack the right competencies and professional backgrounds for work must change to make civilian CIs full members of the work groups.

The study reveals that female civilian CIs feel they lack authority; have the wrong competencies for work, even though they often have professional backgrounds that should be of importance for criminal investigative work (Rice Citation2020); should not be hired at all; or need to downplay their specific knowledge and professional backgrounds. Because professional identities can be understood as group-based identities done according to collective norms, rules, and values at work (Bayerl et al. Citation2018), civilian CIs’ experiences of exclusion signal troubling, devalued and suppressed professional identities.

Instead, in the descriptions of high uniqueness, civilian CIs’ professional backgrounds and university degrees are described as unique and important for CI work, strengthening their professional identity and sense of contributing something beyond what police CIs do – something police CIs can learn from. In this way, they present as very capable, and their professional ‘otherness’ identity can be redone as positive and highly valued, aspects that relate to what Rice (Citation2020) referred to as equal partners. Some narratives even highlight that women are talked about as being extra valuable in police investigations.

To conclude, for female civilian CIs to get a sense of being valued for their uniqueness, police organisations need to upgrade and address the status of civilian CIs and open more possibilities for civilian CIs to establish careers. Another aspect to consider is workplace conditions that foster learning between police and civilian CIs in everyday investigative work. If treated as unique but equal partners, both gender and professional identity can be redone and need not be treated as problems in the future.

Concluding remarks

Overall, this study points out important aspects to consider, because police organisations struggle to recruit and retain women and members of other minority groups and backgrounds. The above discussed themes of contributions to low and high belongingness and uniqueness could be used as a catalyst for talking about perceptions of inclusion/exclusion at work as a measure to achieve a sustainable and equal work environment in which retaining civilian CIs is important. Shore et al.’s (2011) framework has functioned as a valuable theoretical tool for more thorough analyses of not only narratives of total inclusion or exclusion, but also modes in between, such as assimilation or differentiation. Therefore, this theoretical framework can be seen as contributing to both the research field and to organisational learning and deeper understandings of ways of doing and redoing gender and professional identity, the complexity of organisational membership, and feelings of inclusion at work.

From this, we hope the study can inform police authorities on how to reduce obstacles and barriers and abolish a culture that devalues or even discriminates against civilian and female CIs. The feelings of lacking the right habitus (Atkinson Citation2017) and of being outsiders (McCarty and Skogan Citation2013) need to be addressed and turned into strengths, demonstrating civilian CIs’ contributions to criminal investigative work with different and unique competencies, professional backgrounds, and experiences (Rice Citation2020), which can make police organisations more inclusive and diverse but equal (Alderden and Skogan, Citation2014, Kiedrowski et al. Citation2019).

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Kirsi Kohlström and Cassandra Poikela, who did some of the interviews in this project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ulrika Haake

Ulrika Haake, PhD, is a full professor at the department of Education, Umeå university. Her research interests include Higher Education and the Police, focusing on issues of governance, organisation, leadership, and gender equality.

Umeå University, Department of Education, S-901 87 Umeå, Sweden, + 46(90)7869621, [email protected], https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2948-8647

Ola Lindberg

Ola Lindberg, PhD, is an associate professor at the department of Education, Umeå university. His research mostly concerns professional learning and professional education with a practice theory outlook. Studies have been carried out in the medical profession and the Police.

Umeå University, Department of Education, S-901 87 Umeå, Sweden, + 46(90)7866867, [email protected] https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8517-0313

Oscar Rantatalo

Oscar Rantatalo, PhD, is an associate professor at the department of Education, Umeå university. His research interests focus on organisational education where he studied and published on topics such as leadership, competence, organisational sensemaking, and change.

Umeå University, Department of Education, S-901 87 Umeå, Sweden, + 46(90)7866564, [email protected] https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1440-0470

References

- Acker, J., 2006. Inequality regimes: gender, class, and race in organizations. Gender & society, 20 (4), 441–464.

- Alderden, M., and Skogan, W.G., 2014. The place of civilians in policing. Policing: an international journal of police strategies & management, 37, 259–284.

- Atkinson, C., 2017. Patriarchy, gender, infantilisation: a cultural account of police intelligence work in Scotland. Australian & New Zealand journal of criminology, 50 (2), 234–251.

- Bayerl, P.S., Horton, K.E., and Jacobs, G., 2018. How do we describe our professional selves? Investigating collective identity configurations across professions. Journal of vocational behavior, 107, 168–181.

- Billett, S., 2006. Constituting the workplace curriculum. Journal of curriculum studies, 38 (1), 31–48.

- Brå. 2016. Rättsväsendets förutsättningar att personuppklara brott—Förändringar sedan 2006 [The preconditions of the judiciary in solving crimes in person—Changes since 2006]. Report 2016:10.

- Chaiyavej, S., and Morash, M., 2009. Reasons for policewomen’s assertive and passive reactions to sexual harassment. Police quarterly, 12, 63–85.

- Cosgrove, F., 2016. ‘I wannabe a copper’: the engagement of police community support officers with the dominant police occupational culture. Criminology & criminal justice, 16 (1), 119–138.

- Fejes, A., and Haake, U., 2013. Caring and daring discourses at work: doing gender through occupational choices in elderly care and police work. Vocations and learning, 6, 281–295.

- Freeman, M., 2015. Narrative as a mode of understanding: method, theory, praxis. In: A. De Fina, and A. Georgakopoulou, eds. The handbook of narrative analysis. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, 21–37.

- Gherardi, S., 1994. The gender we think, the gender we do in our everyday organizational lives. Human relations, 47 (6), 591–610.

- Haake, U., 2018. Conditions for gender equality in police leadership – making way for senior police women. Police practice and research, 19 (3), 241–252.

- Haake, U., Rantatalo, O., and Lindberg, O., 2017. Police leaders make poor change agents: leadership practice in the face of a major organisational reform. Policing and society, 27 (7), 764–778.

- Ibarra, H., 1999. Provisional selves: experimenting with image and identity in professional adaptation. Administrative science quarterly, 44 (4), 764–791.

- Jacobsen, J.P., 2007. Occupational segregation and the tipping phenomenon: the contrary case of court reporting in the USA. Gender, work & organization, 14 (2), 130–161.

- Keddie, A, 2022. Gender equality reform and police organizations: A social justice approach. Gender Work and Organization, 1–16. doi:10.1111/gwao.12918.

- Kelan, E.K., 2010. Gender logic and (un)doing gender at work. Gender, work & organization, 17, 174–194.

- Kelan, E.K., 2018. Men doing and undoing gender at work: a review and research agenda. International journal of management reviews, 20, 544–558.

- Kiedrowski, J., Rudell, R., and Petrunik, M., 2019. Police civilianisation in Canada: a mixed methods investigation. Policing and society, 29 (2), 204–222.

- King, W., 2009. Civilianization. In: E. Maquire, and W. Wells, eds. Implementing community policing: lessons from 12 agencies. USA: U.S. Department of Justice, 65–70.

- Kurtz, D.L., and Upton, L.L., 2018. The gender in stories: how war stories and police narratives shape masculine police culture. Women & criminal justice, 28 (4), 282–300.

- Langan, D., Sanders, C.B., and Gouweloos, J., 2019. Policing women’s bodies: pregnancy, embodiment, and gender relations in Canadian police work. Feminist criminology, 14 (4), 466–487.

- Liederbach, J., Fritsch, E.J., and Womack, C.L., 2011. Detective workload and opportunities for increased productivity in criminal investigations. Police practice and research, 12 (1), 50–65.

- Lindberg, O., Rantatalo, O., and Stenling, C., 2017. Police bodies and police minds: professional learning through bodily practices of sport participation. Studies in continuing education, 39 (3), 371–387.

- Loftus, B., 2008. Dominant culture interrupted: recognition, resentment, and the politics of change in an English police force. British journal of criminology, 48 (6), 756–777.

- Lykke, N., 2010. Feminist studies: a guide to intersectional theory, methodology and writing. London: Routledge.

- Martin, P.Y., and Collinson, D.L., 1999. Gender and sexuality in organisations. In: M.M. Ferree, J. Lorber, and B.B. Hess, eds. Revisioning gender. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage, 285–310.

- McCarthy, D.J., 2013. Gendering ‘soft’ policing: multi-agency working, female cops, and the fluidities of police culture/s. Policing and society, 23 (2), 261–278.

- McCarty, W.P., and Skogan, W.G., 2013. Job-related burnout among civilian and sworn police personnel. Police quarterly, 16 (1), 66–84.

- Morash, M., and Haarr, R.N., 2012. Doing, redoing, and undoing gender: variation in gender identities of women working as police officers. Feminist criminology, 7 (1), 3–23.

- Morrell, K., 2014. Civilianization and its discontents. Academy of management proceedings, 2014 (1), 11572.

- Murray, S.E., 2021. Seeing and doing gender at work: a qualitative analysis of Canadian male and female police officers. Feminist criminology, 16 (1), 91–109.

- Patterson, N., Mavin, S., and Turner, J., 2012. Unsettling the gender binary: experiences of gender in entrepreneurial leadership and implications for HRD. European journal of training and development, 36 (7), 687–711.

- Pratt, M.G., Rockmann, K.W., and Kaufmann, J.B., 2006. Constructing professional identity: the role of work and identity learning cycles in the customization of identity among medical residents. Academy of management journal, 49 (2), 235–262.

- Rabe-Hemp, C., 2009. POLICEwomen or policeWOMEN? Doing gender and police work. Feminist criminology, 4, 114–129.

- Rabe-Hemp, C., and Beichner, D., 2011. An analysis of advertisements: a lens for viewing the social exclusion of women in police imagery. Women & criminal justice, 21 (1), 63–81.

- Rice, L., 2020. Junior partners or equal partners? Civilian investigators and the blurred boundaries of police detective work. Policing and society, 30 (8), 966–981.

- Riessman, C.K., 1993. Narrative analysis. Newbury Park: Sage.

- Rowe, M., et al., 2023. Visible policing: uniforms and the (re)construction of police occupational identity. Policing and society, 33 (2), 222–237.

- Shields, S.A., and Dicicco, E.C., 2011. The social psychology of sex and gender. Psychology of women quarterly, 35, 491–499.

- Shore, L.M., et al., 2011. Inclusion and diversity in work groups: a review and model for future research. Journal of management, 37 (4), 1262–1289.

- Silvestri, M., and Tong, S., 2022. Women police leaders in Europe: a tale of prejudice and patronage. European journal of criminology, 19 (5), 871–890.

- Slay, H.S., and Smith, D.A., 2011. Professional identity construction: using narrative to understand the negotiation of professional and stigmatized cultural identities. Human relations, 64 (1), 85–107.

- Swedish Police Authority, 2018. Tillsyn över ärendebalansen i utredningsverksamheten [Supervision of the case balance in the investigative work]. Stockholm: Police Authority.

- Swedish Police Authority, 2019. Granskning av Polismyndighetens kultur [Examination of the culture of the police authority]. Stockholm: Police internal revision.

- Swedish Police Authority, 2022. Polismyndighetens årsredovisning 2022 [The Police Authority’s annual report 2022]. Stockholm: Police Authority.

- Torres, L.D., Jain, A., and Leka, S., 2019. (Un) doing gender for achieving equality at work: the role of corporate social responsibility. Business strategy & development, 2, 32–39.

- West, C., and Zimmerman, D.H., 1987. Doing gender. Gender & society, 1 (2), 125–151.

- West, C., and Zimmerman, D.H., 2009. Accounting for doing gender. Gender & society, 23, 112–122.

- Whelan, C., and Harkin, D., 2021. Civilianising specialist units: reflections on the policing of cybercrime. Criminology & criminal justice, 21 (4), 529–546.