ABSTRACT

The police occupy a central role in the functioning of the state by being tasked with upholding security, law and order. Across the African continent, the public has little trust in the police, but such perceptions are subject to considerable subnational variation. In this study, we are interested in how the different contexts in which the police operate affect police-citizen relations. We ask: How does an urban versus rural environment shape citizens’ trust in the police? We address this question within the context of Kenya, using geocoded survey data from Afrobarometer. We theorise that the rural versus urban environment will shape citizens’ experience with the police in ways that affect their attitudes toward the police. Specifically, we argue that in a context where the police have frequently been employed to repress specific sociopolitical groups, urban residents, living in denser and more diverse environments compared to rural residents, are more prone to have first- or second-hand experiences of the police that result in diminished trust towards them. Our results support these propositions: We find a strong and robust relationship between urban residence and lower levels of trust in the police. The relationship holds when controlling for respondents’ political alignment, which likely conditions people’s perceptions of state institutions. Qualitative evidence from interviews provide additional understanding of the urban-rural divide we identify. Our results provide important insights into the contextual dynamics that shape individuals’ trust in the police, and underline the importance of efforts to improve police-community relations in urbanising contexts.

Introduction

The police occupy a central role in the functioning of the state by being tasked with upholding security, law and order. In many contexts, the police also serve a conflict preventing function, by means of deterrence as well as dispute resolution before conflicts escalate into violence. However, the police have also been applied as a tool for intimidation, control and repression of dissent. In many African countries, demands for police reform have followed in the footsteps of recent reports about police misconduct. In Nigeria, the end-SARS movement gained widespread attention, and similar protests have taken place in, for example, South Africa and Ghana. Across the continent, the public has little trust in the police. In one study, the police are seen as the most corrupt state institution in 11 of 18 African countries surveyed (Sanny and Logan Citation2020). Research shows that experiences of corruption and other forms of misconduct affect how citizens assess police effectiveness, procedural justice and trustworthiness (Tankebe Citation2010). Studies also demonstrate that the broader conditions influencing relationships and trust between citizens and police vary sub-nationally and are contingent on socio-political circumstances.

We address one possible determinant of sub-national variation in how the police is perceived, posing the question: How does an urban versus rural environment shape citizens’ trust towards the police? We argue that urban and rural areas feature different social and institutional settings that influence police-citizen relations, ultimately impacting public attitudes. Specifically, we suggest that in a setting where the police have frequently been used to repress specific sociopolitical groups, urban residents, living in denser and more diverse environments than rural residents, are more prone to have first- or second-hand experiences of the police that lead them to conclude that policing is unfair. These experiences in turn translate into mistrust. We analyse these propositions in the context of Kenya, using geocoded survey data from the Afrobarometer (rounds 5–8). In addition, to validate and probe the findings, we draw on qualitative insights based on research conducted in Kenya.Footnote1

The study advances research on police-citizen relations in contexts affected by a history of colonial policing and violent conflict in two important ways. First, recognising the importance of the police in both the prevention and production of violence (Eck et al. Citation2021), we focus on understanding variation in police-citizen relations across space and in the different environments the police operate. Specifically, we begin from the assumption that the capacity of the police to carry out their duties relies on the legitimacy they possess (Tyler Citation2003). Second, while some previous research has identified a rural-urban divide in how citizens interact with and perceive of the police (Boateng Citation2018, Dlamini Citation2020, Ndoma Citation2020, Sanny and Logan Citation2020), few studies have attempted to theorise and empirically investigate why and how the rural and urban environments that the police operate in matters. We build on previous work showing that when the police engage in repression, political partisanship shapes how people perceive the police (Curtice Citation2021). In line with these insights, we postulate that experiences of police repression and consequently citizens’ trust in the police, are affected by the individual’s political alignment and communal belonging. However, we develop and evaluate the argument that that in a context where policing is politicised, the urban-rural context will have an independent effect on trust among both opposition and incumbent supporters.

Kenya is a suitable case for investigating urban-rural dimensions of citizens’ perceptions of the police. First, baseline trust in police is low and like many other African states, policing institutions in Kenya have been strongly shaped by a colonial legacy, state repression, violent communal conflicts and spillover effects from armed conflict in neighbouring states. Both rural and urban areas have been affected by violence and it tends to be associated with electoral and macro-political dynamics. Linked to these processes, the police have been implicated in political violence undermining their legitimacy as a body protecting all citizens equally (Ruteere Citation2011, Saferworld Citation2021). In addition, the police have especially in urban settings been involved in killings disproportionally affecting poor, young men in marginalised settlements (Price et al. Citation2016, Kimari Citation2017, van Stapele Citation2020). Second, Kenyan politics have to a large extent revolved around rural interests, and the country still contains a strong rural base.Footnote2 Compared to many other African countries, the urbanisation level is relatively low (27% in 2018 according to United Nations data (UNDESA Citation2018: 21)). At the same time, Kenya is urbanising rapidly, and the urban population is distributed across a relatively high number of large and medium-sized cities (OECD/SWAC Citation2023). These changing dynamics – mirrored in many other African states – make the issue of rural-urban divides important to investigate. Third, Kenya has relatively strong state institutions, but their effective presence varies considerably across different parts of the country (Chopra Citation2009), and security functions are sometimes delegated to local informal or hybrid institutions (Mkutu Citation2018, Mutahi Citation2021). Such dynamics are likely to impact on police-citizen interactions and on perceptions of the police. Finally, Kenya is undergoing police reforms aimed at improving the interaction between police and local communities (Lid and Okwany Citation2020, Diphoorn and van Stapele Citation2021, Mutahi et al. Citation2023). Understanding how the contexts in which the police operate shape citizens’ perceptions of the police provide important insights into the conditions for such reforms to be successful.

Previous research

Trust is central to policing: It affects both objective measures of ‘police effectiveness’ and subjective perceptions of safety among the public. A large body of research has found that public propensity to cooperate with the police and to obey the law is heavily affected by how the police behaves and whether citizens perceive their conduct to be fair and effective (e.g. Kelling and Coles Citation1997, Sunshine and Tyler Citation2003, Tyler Citation2003, Tankebe Citation2013). A key finding is that perceptions of fairness matter more than objective and subjective measures of effectiveness (Tyler Citation2004). However, knowledge about the conditions under which perceptions about the police are formed, and if they are subject to change, is limited. Further, the vast majority of this research has focused on Latin America and the West, and particularly on the US. It remains unsettled whether the findings from these contexts apply elsewhere.

Research from African contexts has underlined how a different historical and institutional context has shaped interactions between police and citizens. Notably, many African states have inherited or developed internal security apparatuses with low legitimacy, heavily relying on coercion and intimidation, with implications for trust in the police (Tankebe Citation2009). For instance, in Ghana – with a context of poor police performance and a legacy of colonial policing – the perceived legitimacy of the police is so low that a minimum level of effectiveness matters more than fairness (ibid.). Studies in other African contexts – Nigeria, Sierra Leone and South Africa – have found that both fairness and effectiveness affect public willingness to cooperate with the police (Akinlabi and Murphy Citation2018, Boateng et al. Citation2022).

How do sub-national dynamics affect trust in the police? Studies from North America have highlighted demographic factors (notably, race) as conditioning the relationship between police and citizens and, in turn, the attitudes of the public towards the police (see e.g. Thomas and Hyman Citation1977, Prine et al. Citation2001, Nofziger and Williams Citation2005). In societies ravaged by armed conflict, the local intensity of conflict has been shown to influence public perceptions of how effective, fair and trustworthy the police is (Deglow and Sundberg Citation2021), and research has also assessed the impact of police reform intended to improve the effectiveness and legitimacy of post-war security functions, for example in Liberia (Blair et al. Citation2019, Blair and Morse Citation2021, Nilsson and Jonsson Citation2023).Footnote3 Some studies have also analysed if attitudes towards the police differ between urban and rural contexts, but results are mixed (Brown and Benedict Citation2002). Several studies find no, or unclear, effects of urban/rural location on trust in the police and the willingness to report crime (e.g. Skogan Citation1984, Jackson and Bradford Citation2019). Other studies have identified differences between rural and urban contexts, which are partly conditional on aspects like socioeconomic status. For instance, one study compared different locations in the US, and found that the urban poor held the most negative attitudes toward police, while rural residents and the urban middle class held more positive attitudes to the police (Albrecht and Green Citation1977: 75). Another study, also from the US, found that students in urban areas had more negative attitudes to police than students in suburban areas (Hurst and Frank Citation2000). In Canada, by contrast, studies have also found rural residents to be less satisfied with the police and their ability to cooperate and ensure the safety of citizens (Ruddell and O’Connor Citation2022).

Studies focusing on African contexts also give indications of an urban-rural divide in attitudes towards the police. For instance, a recent multilevel cross-national study by Boateng found that across Africa, urban residents were less likely to perceive the police as legitimate, than rural-based residents were (Boateng Citation2018: 1114). Studies from individual African countries add more nuance to these patterns. For instance, in Zimbabwe (2018), reported trust in both the police and army was ‘10 percentage points higher in rural than in urban areas’ (Ndoma Citation2020: 3). In contrast, survey-based research from South Africa found no clear effect of urban-rural residence on attitudes towards the police (Fry Citation2013). Finally, some studies focus on the urban-rural divide as a spectrum rather than as a clear dichotomy (Gizelis et al. Citation2021, Meth et al. Citation2021). Dlamini (Citation2020), for example, found that residents in areas close to the city centre displayed less trust and less positive attitudes toward the police than those living on the city outskirts.

Differences in attitudes toward the police may in turn relate to citizens’ experiences with the police. Analysing recent survey data from 18 African countries, Sanny and Logan (Citation2020: 10) find that urban residents interact more often with the police, whereas rural residents who do interact with police are more likely to face demands for bribes. Studies of police-citizen interactions in Kenya have focused on the varying outcomes, and challenges, of successive efforts of police reform in recent decades, including an increasing emphasis on community policing and moving away from a police force to a police service (Osse Citation2016, Gjelsvik Citation2020, Diphoorn and van Stapele Citation2021). This work underlines how efforts at police reform have often tended to reinforce existing oppressive structures (Ruteere and Pommerolle Citation2003), and that contextual dynamics including ‘conflicting socio-economic and political interests at the community and national levels’ condition the prospects for building trust toward the police (Gjelsvik Citation2020: 19). While these studies provide important insights into the factors that shape local attitudes towards the police in Kenya, they have not systematically analyzed sub-national patterns and their causes.

In sum, existing research has emphasised the importance of attitudes toward the police, but only to limited extent explained how and why such attitudes vary sub-nationally. For long, a focus on Western states dominated the field, but recent advances have made important contributions to knowledge about attitudes toward the police in African contexts. Within this literature, findings regarding how socio-political and institutional factors shape attitudes remain mixed. Several studies identify an urban-rural divide in attitudes to the police, but do not theorise why this is the case and/or do not control for the possibility that this relationship is driven by political dynamics in urban and rural areas. While several important studies of the factors shaping Kenyans’ perceptions of the police exist, we know little about how the urban-rural contexts affect the propensity of citizens to mistrust the police.

Police-citizen relations and patterns of (mis)trust in the police

Our main theoretical interest is how the different contexts in which the police operate affect police-citizen relations, focusing on how an urban versus rural environment shape the public’s perceptions of the police. Public perceptions of the police encompass a range of issues including citizens’ subjective assessment of the effectiveness and fairness in how the police carry out their work and exercise their authority (Tyler Citation2003). In this study, we look at trust in the police as an important feature of police-citizen relations. We operate from the assumption of relatively low baseline levels of public trust in the police in a context with a history of state repression (including inherited colonial policing methods), ongoing insecurity, and politicised security institutions (Ruteere Citation2011, Hassan Citation2020). We also assume that important features of the social and institutional environment in which the police operate differ between rural and urban areas. Conceptually, we understand cities and other urban centres as sites characterised by high population density, frequent interaction between diverse groups and interests, and nodal points for economic accumulation and political networks (Simone Citation2004). By contrast, rural areas are characterised by lower population density and more social homogeneity (Magadi Citation2017). In practice, the distinction between urban and rural is not clear-cut, and the extent to which urban dynamics are present varies within cities (for instance, city centre vs more village-like suburbs) and across rural areas (for instance, at what point a small town can be considered ‘urban’) (Simon Citation2008, Agergaard et al. Citation2019). Acknowledging this complexity, we theorise about police-citizen interactions in what can be considered as ideal-type urban and rural contexts. In the methodological section, we discuss how this approach corresponds to our empirical strategy.

We expect urban residents to have lower trust in the police than rural residents. We theorise this to be the case, because the rural and urban environment create different conditions for police-citizen relations (Wang and Sun Citation2020, Ruddell and O’Connor Citation2022). In settings where the police have been used as a tool for repression of specific socio-political groups, we argue that urban residents are more likely to have first- or second-hand experiences that lead them to conclude that policing is not fair. As noted above, previous research has suggested that perceptions of fairness are strongly correlated with perceived legitimacy and trust in the police (Tyler Citation2004). Fairness relates to police conduct and whether or not citizens perceive that they are treated equally. Citizens form an opinion of police fairness based on their own experience of police interactions, as well as observations of police behaviour and general knowledge about police behaviour in their community (Tyler Citation2004). When citizens are treated with respect by the police and are treated equally to other groups, as well as are allowed to provide their account of how and why a situation emerged, they are more likely to perceive the police as fair (Sunshine and Tyler Citation2003, Tyler Citation2004).

The argument for why we expect urban and rural residents to have divergent experiences of the police unfolds in two steps. First, we expect that police-citizen interactions are overall more visible and frequent in cities than in rural areas.Footnote4 In rural areas, police cover large jurisdictions and geographical distances which influence how fast communities and their citizens can be serviced (Weisheit et al. Citation1995). In many rural locations, police are simply ‘spread thin’ (Ruddell and O’Connor Citation2022: 117). While the distribution of police and their presence vary sub-nationally, presence is generally lower in rural areas of Kenya, as in most countries. The most visible security force in the most rural areas of Kenya is the Kenya Police Reserve (KPR), especially in arid and semi-arid regions, where they are the main source of security against bandits and cattle raiders (Agade Citation2015).Footnote5 Under the National Police Service Act (Government of Kenya 2012), the Reserve is mandated to recruit and train personnel that could be deployed to assist both the Kenya Police Service and the Administration Police Service in the implementation of their mandates. Although the KPR falls under the Officer Commanding Police Division, the Chiefs also play a role in the daily management of the KPR. In both urban and rural areas, police officers are deployed away from their home areas and frequently reshuffled (Hassan Citation2017, Mbuba Citation2018). However, KPR are more likely to work within their own communities of origin.

Recent studies emphasise that the role of the police in Kenya needs to be understood in the context of a broader spectrum of actors involved in policing or security governance (Mkutu Citation2018, Mutahi Citation2021). Overall, in many rural areas, formal policing is of relatively low importance, because other strong institutions for managing local security exist. Notably, the authority of traditional and religious conflict management structures is often more well-established than in urban areas (Adan and Pkalaya Citation2006), providing a pre-existing infrastructure for rural populations to solve disputes and seek recourse when faced with crime and insecurity.Footnote6 The Kenyan system in which rural police to a large extent worked through (neo)customary institutions is a legacy of the colonial period (Ruteere Citation2011). When the police constitute a less relevant body for rural populations than alternatives, the frequency of contacts between the police and rural residents is further reduced. As a result, rural residents are less likely to have direct contact with the police than urban residents.

Theoretically, low police visibility and interaction could translate into lower public trust. Yet in line with the ‘asymmetry thesis’ about police-citizen interaction, we expect the opposite in a context where baseline trust is generally low. The ‘asymmetry thesis’ posits that ‘trustworthiness is easy to lose and hard to win’ (Oliveira et al. Citation2021: 1004). In essence, it holds that negative encounters with the police (such as police brutality, unfair treatment, or inability or unwillingness of the police to address a crime one reports) tend to have a strong negative effect on attitudes toward the police, whereas positive encounters have only a weak positive effect, if any at all (Skogan Citation2006). Although several studies have found empirical support for this thesis, the evidence is not uniform. In a longitudinal study of survey respondents in Australia, Oliveira et al. (Citation2021) found that negative encounters reduced trust in police fairness and effectiveness, whereas positive encounters increased trust in police fairness, but not effectiveness. However, given the overall poor police performance and corruption that has been documented in Kenya (Ruteere and Pommerolle Citation2003, Akech Citation2005, Hope Citation2019), we believe encounters are more likely to be perceived as negative.

Second, the heterogeneity of urban contexts makes it more likely for urban residents to directly observe unfair treatment of different groups (their own and others) by the police or having been informed by others about police misconduct. Urban areas are by definition more densely populated than rural areas, but also tend to be more heterogeneous in their social, economic and political configuration. This heterogeneity, alongside informal and often rapidly changing networks, contribute to the ‘complexity of socio-spatial relations in the city’ (Bjarnesen and Utas Citation2018: S1). While rural areas of Kenya tend to be relatively socio-politically homogenous (Magadi Citation2017), cities and urban areas feature high diversity and inequality. In Kenya’s cities, people from different ethnic and religious groups live closely together and frequently interact across identity lines. Overall, there is ample evidence of how the police have been used by incumbents to repress opposition-aligned ethnopolitical groups, and of everyday bias in policing (Ruteere and Pommerolle Citation2003, Ruteere Citation2011, HRW Citation2013, Ruteere et al. Citation2013, HRW Citation2017, Mutahi Citation2018). In addition, police killings have been particularly common in urban areas, where young men from the informal settlements have been profiled as associated with crime, criminal gangs and terrorism (van Stapele Citation2016, Jones et al. Citation2017, van Stapele Citation2020). The police have also employed a shoot-to-kill policy against certain urban gangs, while supporting or colluding with others (Mutahi Citation2018). While many residents in urban informal settlements feel mistreated and harassed by the police (Price et al. Citation2016), the poor state of security has also given rise to support for vigilantism and on occasion even police involvement in vigilantism (Wairuri Citation2022).

Based on these patterns regarding demography and police killings, urban residents belonging to both opposition and incumbent-aligned communities are more likely to witness how specific groups are treated differently by the police. In more homogenous rural areas, police misconduct may not to the same extent translate into perceptions of unfairness. Importantly, while opposition supporters in both urban and rural areas may be subject to police misconduct, our argument implies that urban residents regardless of political alignment will be more likely to perceive the police as unfair.

Taken together, the theoretical arguments above form the basis for the following main hypothesis:

H1: Individuals living in urban areas hold lower levels of trust in the police than those living in rural areas.

Research design

Our main approach to assessing the urban-rural divide in the public’s perceptions about the police relies on several rounds of Afrobarometer surveys conducted in Kenya 2011–2019 (BenYishay et al. Citation2017, Afrobarometer Citation2019). The Afrobarometer is a useful and widely used source of information capturing citizens’ attitudes on a range of socio-political issues. Our unit of analysis is the individual. We include rounds 5 through 8, which are all carried out after the adoption of Kenya’s 2010 Constitution and available in geocoded format.Footnote7 The new Constitution was adopted after intense electoral violence in 2007–2008, and contains several features that create a new context for police-citizen interactions. One important element is the devolution of power to 47 Counties. Additionally, the Constitution introduced important changes to the structure of the police service, and ushered police reforms intended to alter the way that police and security forces interact with citizens and to improve public perceptions of the police (Hope Citation2015, Skilling Citation2016, Lid and Okwany Citation2020).

Dependent variable

Our main outcome variable of interest is trust in the police, which is measured based on the following question posed to survey respondents: ‘How much do you trust each of the following, or haven’t you heard enough about them to say: The Police?’ (The question is posed in the context of a series of questions probing the degree of trust towards different institutions, governance structures and political parties). Respondents could choose to answer ‘Not at all’, ‘Just a little’, ‘Somewhat’, ‘A lot’, or ‘Don’t know/Haven’t heard enough’ (they could also refrain from answering). Based on this question, we construct a scale variable (the degree of trust) as well as dummy variables denoting different degrees of (mis)trust.

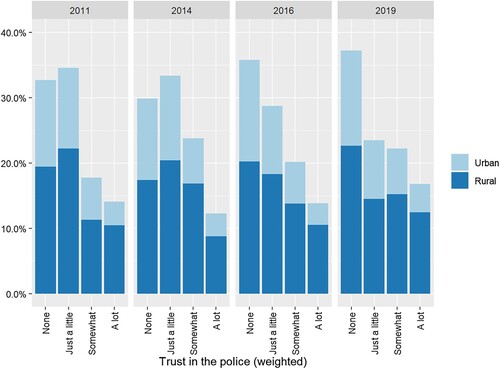

Kenya represents a context where levels of trust in the police are generally low. Of 34 African countries covered in round 8 of the Afrobarometer, Kenya was ranked on 23rd place in terms of levels of trust in the police based on aggregated results: only 38% reported that they trusted the police at least ‘Somewhat’ (Logan et al. Citation2022: 12). shows general levels of public trust in Kenya over the four Afrobarometer survey rounds we rely on, from 2011 to 2019. The graph shows low levels of public trust in police in Kenya, but also that trust levels have fluctuated somewhat over time.Footnote8 When aggregating the two categories of trust in police ‘Not at all’ and ‘Just a little’ into one, the pattern is consistent: for all four survey rounds, more than 60% of the population surveyed report no or just a little trust in the police.

Main independent variable

To assess if there are differences between trust in the police in urban and rural areas of Kenya, we rely on the binary measure provided in the Afrobarometer data which denotes whether the survey was conducted in an urban or rural area. The urban-rural indicator in Afrobarometer data is based on each country’s official census classification of enumeration areas, which forms a basis for the sampling frame (Harding Citation2020: 38). Mirroring Kenya’s relatively low level of urbanisation, around 1/3 of interviews in each survey round were conducted in urban areas. Survey locations coded as urban include neighbourhoods of major cities like Nairobi and Mombasa, but also smaller urban centres like Githurai (Kiambu County), Naivasha (Nakuru County), and Mandera (Mandera County) (Wiesmann et al. Citation2016). Areas on the ‘urban fringe’ of larger cities are coded as urban, including suburbs like Mararo, Ruiru and Kitengela on the outskirts of Nairobi. While the census classification is based on population density, it is acknowledged that some areas coded as urban display more rural characteristics (Wiesmann et al. Citation2016: 18).

Control variables

Our theoretical argument recognises the highly politicised role of the police in Kenya. Under successive regimes, the police have been used as an instrument to repress dissent and protect the incumbent (Ruteere Citation2011, Hassan Citation2020). A first factor we control for is therefore the political alignment of the respondent, as we have expectations that opposition-aligned citizens will have lower trust in the police (and other state institutions), all else equal. In addition, opposition support tends to be stronger in African cities, compared to in rural areas (Resnick Citation2011, Harding Citation2020) which could confound the results for our main hypothesis. We use the following question from the Afrobarometer to capture if the respondent is opposition or incumbent aligned: ‘If a presidential election were held tomorrow, which party’s candidate would you vote for?’ We create the dummy variable incumbent aligned which takes the value 1 if the respondent listed the ruling party or a party in the ruling coalition, and 0 if they indicated other parties.Footnote9 The descriptive statistics () indicate that across rounds, 4335 people answered they would vote for the ruling party or coalition, and 2513 that they would vote for an opposition party. There is a high amount of missing data for this variable (people who refused to answer or responded ‘don’t know’). In combination with the very even election outcomes during the period under study, the large share of missing data suggests that opposition supporters may be less likely to answer this question. As a robustness check, we therefore re-run our main models keeping all non-answers in the 0 category (see Appendix 2).

Table 1. Summary statistics.

We also control for a number of individual-level factors which previous research has shown to influence the degree of trust in the police: gender, education level, and socioeconomic status. All are based on the Afrobarometer data. For socioeconomic status, we use the following question: ‘Over the past year, how often, if ever, have you or anyone in your family: Gone without a cash income?’ In addition, research indicates that exposure to violence affects trust in the police, and violence patterns vary sub-nationally in Kenya which could confound our results. We control for the exposure to violence by leveraging the geocoded Afrobarometer data where the location of each interview is coded at town or village level (BenYishay et al. Citation2017). We match the survey data to georeferenced data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Dataset (ACLED) (Raleigh et al. Citation2010) and control for the presence (dummy variable) and intensity (scale) of violence against civilians in the area wherein the respondent is living, in the years preceding the survey.Footnote10 To assess the robustness of our results, we include additional variables from the Afrobarometer data capturing trust in the local government authorities, the army, and perceptions about police corruption. Finally, to account for the fact that individuals living in the same geographical area are not independent from each other, we include county-clustered standard errors (models 1 and 4-5). Similarly, to account for the fact that there may be time-invariant county-specific confounders in the data, we include county fixed effects in all models.

Results

We test our theoretical expectations in a series of OLS regression models. Our results are reported in below and provide strong support for our hypothesis that individuals living in urban areas hold lower levels of trust in the police than those living in rural areas. Across models, our ‘urban’ dummy variable is negatively associated with trust in the police, and this association is consistently statistically significant. These results indicate that, all else equal, respondents in urban areas hold lower levels of trust toward the police. In model 1, where we include no additional control variables, we can see that respondents in urban areas on average rated their trust in the police around 0.17 points lower on a scale from 0 to 3, compared to rural respondents.

Table 2. Police trust, OLS regression models.

Our results for our main independent variable hold when controlling for a set of potentially confounding factors. Importantly, the association remains statistically significant when controlling for the political alignment of the respondent, which we introduce as a control variable in models 2–5. As expected, respondents who stated that they would vote for the incumbent party also held higher levels of trust in the police, but the correlation between urban residence and lower trust in police remains statistically significant when this variable is included. This indicates that the urban-rural divide in police trust cannot be explained by subnational variation in support for the incumbent or the opposition. The association is also robust to inclusion of control variables such as gender, education level, and poverty level, included in models 2–5. In line with previous studies (Brown and Benedict Citation2002), higher education levels are associated with lower trust in the police, and poverty is correlated with lower trust in police.

The results are robust to controlling for local exposure to violence in models 3 and 5. Substituting the dummy variable with a continuous measure of the amount of such violence (reported in Appendix 2) does not change the results. Our results are also robust to inclusion of round fixed effects, which accounts for the fact that there may be unobserved year-specific factors that affect individuals’ trust in police. The coefficients (reported in Appendix 2) indicate that compared to round 5 (2011), respondents reported higher trust in the police in the later rounds 6 (2014), 7 (2016) and 8 (2019). This could be a sign that police reforms in that period helped improve the public’s trust in police, but it could also reflect recovery from very low levels of trust following the 2007–2008 post-election violence. Finally, we noted above that there is reason to suspect that opposition supporters may be less likely to answer the question about political alignment truthfully, which could bias our results. However, the results are robust to including an alternative control for incumbent alignment, where all non-replies are included in the model and coded as not incumbent aligned (reported in Appendix 2).

Discussion and extended analysis

There are important contextual factors to consider when interpreting these results. First, security challenges related to attacks by al-Shabaab and other transnational terrorist groups during the period under study likely affected policing in Kenya and public trust in the security forces. Cities are prime targets of terrorist attacks, which means that policing in urban areas may have been more affected by this security threat. However, militant activity by al-Shabaab as well as by cattle rustlers and other armed groups have to a large extent affected rural areas (Mkutu Citation2008, Greiner Citation2013, Lind et al. Citation2017). To probe whether our results are driven by different experiences and attitudes vis-à-vis the security forces in a broader sense, we include a variable denoting trust in the army in models 2 and 5. We find that higher levels of trust in the army is associated with higher trust in the police, but the results for our main independent variable – urban vs rural residence – remains statistically significant.

Second, we study a time period during which significant reforms took place in the organisation and role of the police. Kenya adopted a new Constitution in 2010, which has entailed substantial devolution of power as well as police reform. The former could mean that political relationships at the local level may become relatively more important in mediating attitudes toward the police. While we control for the effect of survey round, reforms have been uneven and the pace of reform could be systematically different in urban and rural areas. Police reforms have taken place simultaneously with decentralisation to Kenya’s 47 Counties, which introduces additional possible sub-national variation in political dynamics surrounding the police and civilian oversight. In models 3 and 5, we also include a variable denoting trust in the County government. This variable indicates that higher levels of trust in the County government is associated with higher trust in the police. Again, however, our main results are robust to inclusion of this variable: the association between urban residence and attitudes to police is not driven by trust in county-level politicians. In addition, when we control for whether respondents perceive the police as corrupt (models 3 and 5), our main independent variable remains statistically significant. In line with previous research, perceiving the police as corrupt correlates with lower levels of trust in the police. Taken together, our results are robust to the additional variables included in models 3 and 5, strengthening our confidence that what we find is not due to people who reside in rural areas being more trusting in general, or that low police trust is only explained by perceptions of them as being corrupt.

In sum, our analysis indicates a robust and negative relationship between urban residence and levels of trust in the police. This is in line with our hypothesis, and our broader theoretical argument that the rural and urban environment create different conditions for police-citizen relations, leading to different levels of trust. Specifically, we theorised that trust towards police would be lower in urban areas, because urban residents are more likely to have first- or second-hand experiences that lead them to conclude that policing is not fair.

Our quantitative analysis of observational data does not allow us to directly test the proposed causal mechanism connecting trust in police and urban-rural residence. However, our argument that the rural and urban environment create different conditions for police-citizen relations is supported by qualitative evidence from interviews we have conducted with different stakeholders in Kenya. One government official with experience of both rural and urban areas reflects:

The local set up in a rural area is that you will have more homogenous groups. They can more easily agree due to similarities. It also makes policing work easier. Communities even help in policing, which makes it easier to track criminals there than in urban areas. Some like the pastoralists also have social sanctions. In towns, because of the nature of the population, organizing them is more difficult and they are more secretive. In the rural, people know everyone. In rural areas there is more natural respect for the police. They are seen as honest persons. Here [in the city] they profile the police and are acting from a defensive position.Footnote11

In line with our expectation that police-citizen interactions are overall more visible and frequent in cities than in rural areas, another Kenyan government official noted that in his previous deployment in a rural area, one police station served a vast area with 100,000 residents, whereas in his current urban deployment there are four police stations in less than four kilometers.Footnote12

Our argument emphasised fairness, but the results could also be reflective of different perceptions of police effectiveness. In Ghana, Tankebe (Citation2009) found that police effectiveness is a more important predictor of public cooperation with police than perceptions related to fairness. He argued that in environments with poor police performance and a legacy of colonial policing, the perceived legitimacy of the police is so low that a minimum level of effectiveness matters more than fairness (Tankebe Citation2009). Our interviews in Kenya suggest that perceived improved efficiency – for instance, frequent patrols in areas at risk of insecurity during the 2022 elections – improved locals’ trust in the police.Footnote13 Overall, our data does not allow us to adjudicate the relative role that fairness and effectiveness play in shaping Kenyans’ trust in the police. However, the government official cited above suggests that in his experience, police can operate more effectively in rural areas. On the other hand, interviews with urban residents in Nakuru and Naivasha indicate that local police officers are often suspected to collaborate with criminal gangs.Footnote14 Such perceptions are likely lower in rural areas, where criminal networks are less present.

Relatedly, residents in rural and urban areas are prone to interact with different branches of the police. During colonial rule, separate policing structures were set up for policing the cities (where European settlers lived, and Kenyans were only allowed transitory residence) and the rural ‘native areas’; these parallel structures were retained after independence (Ruteere Citation2011: 13). While formally reintegrated as parts of the National Police Service (Government of Kenya, 2012), the branches retain partly different mandates and citizens may hold different degrees of trust toward them. Notably, the Kenya Police Service has a key responsibility for crime prevention and reduction (Government of Kenya, 2012: Part III, section 24), while the Administration Police is tasked with border security, preventing stock theft, and ‘coordinating and complementing Government agencies in conflict management and peace building’ (Government of Kenya, 2012: Part IV, section 27). These different tasks, and the public’s assessment of them, are likely to shape their overall trust in the police. However, the provincial administration has historically been a key tool for rulers to ‘suppress regime opponents, rig elections, and control civilian protests throughout the country’ (Hassan, Citation2015: 588) and there is a history of presidential control of the Administrative Police. Thus, the Administrative Police, more visible in rural areas, would arguably be subject to higher mistrust, in contrast to our findings.

Finally, our theoretical argument is based on the premise that in a setting of repressive policing and low overall trust, interactions with the police will generally have a negative rather than positive effect on citizens’ attitudes. This argument is plausible in a context where ‘the culture of impunity in the police service has contributed to too many cases of insecurity, gross violation of human rights, mistrust by citizens and derailment of key achievements in democratic governance’ (Kivoi and Mbae Citation2013: 189). Ongoing police reforms under the 2010 Constitution are aimed at increasing accountability and oversight. There are mixed results as to whether these reforms increase public trust in police. Interviews conducted in 2022 indicated that whereas building trust is a slow process, citizens no longer fear the police in the same way.Footnote15 One woman working in an urban area with high poverty and crime noted: ‘We – the masses – do not fear the police, but we also do not respect them. In the past when we saw a person in uniform we would turn and go the other way if we were in the right or in the wrong. Now we see them as human beings’.Footnote16 Discouragingly, however, a report based on the most recent Afrobarometer survey,Footnote17 indicates the lowest levels of aggregate trust since 2014, with a full 42% responding they do not trust the police at all (Kamau et al. Citation2022).

Conclusion

A functioning and legitimate police force is essential for ensuring the safety of the public. In addition to dealing with crime, the police also serve a conflict preventing and dispute resolution function in countries like Kenya. Enjoying the trust of the citizens they are intended to serve is vital for the police to perform these tasks effectively. Conversely, mistrust in the police – in Kenya and elsewhere – indicates that ordinary people do not see themselves as enjoying full security, or that they even fear being ill-treated in their interactions with police.

Our study suggests that an important contextual factor affecting citizens’ trust in the police is whether they reside in a primarily urban or rural settling. Our empirical analysis provides evidence that urban residents in Kenya have lower levels of trust in police than rural residents. While other factors commonly associated with trust in state institutions, such as political partisanship, also matter, urban or rural residence has a robust independent effect on police trust. This urban-rural divide in attitudes towards the police, we argue, can be linked to differences in how residents in these two settings are expected to interact with the police and the type of perceptions they gain based on first-hand and second-hand information about police conduct.

Our findings are relevant for understanding police-citizen relations in contexts with similar historical legacies and insecurity, and where police brutality is a common feature of informal urban settlements. They have important implications for reforms seeking to improve police conduct and police-community relationship in Kenya and beyond. On the one hand, the case could be made that efforts to improve police-community relations should be concentrated to informal settlements in urban areas, where police have been largely ineffective in curbing high rates of crime and insecurity and where police harassments and killings have undermined citizen trust in the police (Kimari Citation2017, van Stapele Citation2020, Wairuri Citation2022). The pervasive trend of urbanisation across the continent suggests that police mistrust will only increase as urban centres grow and the police operate in an ever more challenging context. On the other hand, in Kenya and many other African countries a large part of the population still resides in non-metropolitan areas and rural considerations shape social, economic, and political development in important ways. For this reason, the policy and scholarly community should retain focus also on rural settings. Research on attitudes towards the police and police performance generally suffers from an urban bias, and more effort is needed to uncover the dynamics that unfold outside of the cities. For example, research suggests that expectations of police to be more problem-oriented and also address non-criminal issues are greater in rural areas (Jiao Citation2001). Patterns of police performance as well as perceptions of the police are likely to differ between rural and urban areas, but also expectations about the core tasks the police is intended to fill.

Research also needs to consider other important subnational variations and how they intersect with the urban and rural environments the police operate in. Notably, countries affected by violent conflict experience very different security challenges depending on the type and intensity of the violence, and local manifestations of violence will play out differently in urban or rural areas. For example, scholars argue that urban violence and conflict is more nebulous in character than rural violence (Moser and McIlwaine Citation2014), and state-insurgent relations are fundamentally shaped by the urban-rural division, as non-state actors are less likely to control territory in cities that in rural areas, with clear implications for police operations.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (587.9 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the generous sharing of data by the Afrobarometer. We are grateful for feedback on previous versions of the manuscript by Anders Sjögren, Kristine Eck, Desirée Nilsson, and participants in the Research Paper Seminar (Peace and Conflict Research, Uppsala University, April 2022), Urban Violence and Contestation workshop (May 2022), and Peace Research in Sweden conference (Stockholm, November 2022). Elfversson, Ha and Höglund have contributed equally to the writing and conceptualisation of the study, and its execution, except for the quantitative and qualitative empirical analyses. Elfversson and Ha have compiled the dataset and conducted all of the statistical analyses. Elfversson and Höglund have collected qualitative data in Kenya.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Supplemental material for this article is available online, including an appendix and replication data file.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The authors have longstanding research engagement with Kenya and have as part of a larger project on community-based conflict management conducted interviews with local residents, community leaders, police officers and government officials relating to police-citizen relations. The project was approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (dnr 2019-03777) and research permit was granted by the Kenyan National Commission for Science, Technology and Innovation (NACOSTI) (license no. NACOSTI/P/22/16840).

2 Historically, Kenya has had a very high level of rural-biased electoral malapportionment (Barkan et al. Citation2006, Boone and Wahman Citation2015), but the 2010 constitution has rectified some of the biases in urban-rural representation.

3 Policing is also more challenging and complex in societies transitioning from civil unrest (Topping Citation2008), and different forms and levels of violence during armed conflict affect local-level prevalence of crime long after the conflict has ended (Deglow Citation2016).

4 Empirical evidence supports this assumption: a recent survey analysis found that across Africa, young, urban, male respondents were the most likely to have had interactions with the police in the past year (Logan et al. Citation2022).

5 In urban areas, the Reserve was disbanded in 2004, on the ground that many units based in the city had become corrupted and difficult to manage (Saferworld Citation2015).

6 Studies illustrate how police in rural areas are often able to collaborate with local chiefs and community elders to respond to violent incidents and prevent escalatory spirals (Mbuba and Mugambi Citation2011, Elfversson Citation2016), Research also shows that legitimacy and capacity of these institutions vary significantly, and they are often vulnerable to political manipulation and corruption (Van Tongeren Citation2013, Baldwin Citation2016, Kioko Citation2017). The ability of the police to cooperate with local institutions often reflects that they have for a long period been co-opted by colonial and postcolonial governments (Mamdani Citation1996, Boone Citation2014). Still, there is important evidence that such institutions often do retain a strong role in local governance and conflict management in rural areas (Akinwale Citation2010, Elfversson Citation2016).

7 The Afrobarometer sample of respondents is nationally representative. Round 5 was conducted in Kenya 2011 and covered circa 2400 respondents, round 6 (n = 2400) in 2014, round 7 (n = 1600) in 2016, and round 8 (n = 2400) in 2019.

8 Extending the analysis back in time, mistrust in the police is highest in the 2008 survey round with 45% of respondents reporting no trust at all in the police. This high level of mistrust in police is unsurprising given the breakdown of law and order in the 2007/2008 election.

9 More information about how these variables are coded for each round is available in Appendix 1.

10 Version of data as of 2021-08-09. ACLED data is publicly available on www.acleddata.com.

11 Interview, Naivasha, 3 November 2022.

12 Interview, Nakuru, 1 November 2022.

13 Interviews, Naivasha, 4 and 5 November 2022.

14 Interviews, Nakuru and Naivasha, November 2022.

15 Interview, NGO official, Nakuru, 31 October 2022; Interview, public official, Nakuru, 1 November 2022; Fieldnotes, 3 November 2022.

16 Interview, public official, Nakuru, 1 November 2022.

17 The full dataset is not yet released, and is therefore not included in our analysis.

References

- Adan, M., and Pkalaya, R., 2006. A snapshot analysis of the concept Peace Committee in relation to peacebuilding initiatives in Kenya. Nairobi: Practical Action.

- Afrobarometer. 2019. Kenya, Rounds 5-8, 2011-2019. Available at http://www.afrobarometer.org.

- Agade, K.M., 2015. Changes and challenges of the Kenya Police Reserve: The case of Turkana county. African studies review, 58, 199–222.

- Agergaard, J., et al., 2019. Revisiting rural–urban transformations and small town development in sub-Saharan Africa. The European journal of development research, 31, 2–11.

- Akech, J.M., 2005. Public law values and the politics of criminal (in)justice: Creating a democratic framework for policing in Kenya. Oxford university commonwealth law journal, 5, 225–256.

- Akinlabi, O.M., and Murphy, K., 2018. Dull compulsion or perceived legitimacy? Assessing why people comply with the law in Nigeria. Police practice and research, 19, 186–201.

- Akinwale, A.A., 2010. Integrating the traditional and the modern conflict management strategies in Nigeria. African journal on conflict resolution, 10, 123–146.

- Albrecht, S.L., and Green, M., 1977. Attitudes toward the police and the larger attitude complex: Implications for police-community relationships. Criminology, 15, 67–86.

- Baldwin, K., 2016. The paradox of traditional chiefs in democratic Africa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Barkan, J.D., Densham, P.J., and Rushton, G., 2006. Space matters: Designing better electoral systems for emerging democracies. American journal of political science, 50, 926–939.

- Benyishay, A., et al., 2017. Geocoding afrobarometer rounds 1-6: Methodology & data quality. Accra, Ghana: Afrobarometer.

- Bjarnesen, J., and Utas, M., 2018. Introduction urban kinship: The micro-politics of proximity and relatedness in African cities. Africa, 88, S1–S11.

- Blair, R.A., Karim, S.M., and Morse, B.S., 2019. Establishing the rule of law in weak and war-torn states: Evidence from a field experiment with the Liberian National Police. American political science review, 113, 641–657.

- Blair, R.A., and Morse, B.S., 2021. Policing and the legacies of wartime state predation: Evidence from a survey and field experiment in Liberia. Journal of conflict resolution, 65, 1709–1737.

- Boateng, F.D., 2018. Police legitimacy in Africa: A multilevel multinational analysis. Policing and society, 28, 1105–1120.

- Boateng, F.D., Pryce, D.K., and Abess, G., 2022. Legitimacy and cooperation with the police: examining empirical relationship using data from Africa. Policing and society, 32, 411–433.

- Boone, C., 2014. Property and political order in Africa: Land rights and the structure of politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Boone, C., and Wahman, M., 2015. Rural bias in African electoral systems: Legacies of unequal representation in African democracies. Electoral studies, 40, 335–346.

- Brown, B., and Benedict, W.R., 2002. Perceptions of the police. Policing: an international journal of police strategies & management, 25, 543–580.

- Chopra, T., 2009. When peacebuilding contradicts statebuilding: Notes from the arid lands of Kenya. International peacekeeping, 16, 531–545.

- Curtice, T., 2021. How repression affects public perceptions of police: Evidence from a natural experiment in Uganda. Journal of conflict resolution, 65, 1680–1708.

- Deglow, A., 2016. Localized legacies of civil war: Postwar violent crime in Northern Ireland. Journal of peace research, 53, 786–799.

- Deglow, A., and Sundberg, R., 2021. Local conflict intensity and public perceptions of the police: Evidence from Afghanistan. The journal of politics, 83, 1337–1352.

- Diphoorn, T., and Van Stapele, N., 2021. What is community policing? Divergent agendas, practices, and experiences of transforming the police in Kenya. Policing: a journal of policy and practice, 15, 399–411.

- Dlamini, S., 2020. Citizens’ satisfaction with the South African police services and community police forums in Durban, South Africa. International journal of social sciences & humanity studies, 12, 593–606.

- Eck, K., Conrad, C.R., and Crabtree, C., 2021. Policing and political violence. Journal of conflict resolution, 65, 1641–1656.

- Elfversson, E., 2016. Peace from below: Governance and peacebuilding in Kerio Valley, Kenya. The journal of modern African studies, 54, 469–493.

- Fry, L., 2013. Trust of the police in South Africa: A research note. International journal of criminal justice sciences, 8, 36–46.

- Gizelis, T.-I., Pickering, S., and Urdal, H., 2021. Conflict on the urban fringe: urbanization, environmental stress, and urban unrest in Africa. Political geography, 86, 102–357.

- Gjelsvik, I.M., 2020. Police reform and community policing in Kenya. Journal of human security, 16, 19–30.

- Greiner, C., 2013. Guns, land, and votes: Cattle rustling and the politics of boundary (re)making in Northern Kenya. African affairs, 122, 216–237.

- Harding, R., 2020. Rural democracy: Elections and development in Africa. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hassan, M, 2015. Continuity despite change: Kenya's new constitution and executive power. Democratization, 22, 587–609.

- Hassan, M., 2017. The strategic shuffle: ethnic geography, the internal security apparatus, and elections in Kenya. American journal of political science, 61, 382–395.

- Hassan, M., 2020. Regime threats and state solutions: Bureaucratic loyalty and embeddedness in Kenya. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hope, K.R., 2015. In pursuit of democratic policing: An analytical review and assessment of police reforms in Kenya. International journal of police science & management, 17, 91–97.

- Hope, K.R., 2019. The police corruption ‘crime problem’ in Kenya. Security journal, 32, 85–101.

- HRW, 2013. Kenya: Don’t expand police powers. Nairobi: Human Rights Watch.

- HRW, 2017. Kill those criminals’: Security forces violations in Kenya’s August 2017 elections. Nairobi: Human Rights Watch.

- Hurst, Y.G., and Frank, J., 2000. How kids view cops: The nature of juvenile attitudes toward the police. Journal of criminal justice, 28, 189–202.

- Jackson, J., and Bradford, B., 2019. Measuring public attitudes towards the police. Ottawa: Public Safety Canada.

- Jiao, A.Y., 2001. Degrees of urbanism and police orientations. Police quarterly, 4, 361–387.

- Jones, P. S., Wangui, K. and Ramakrishnan, K, 2017. 'Only the people can defend this struggle’: The politics of the everyday, extrajudicial executions and civil society in Mathare, Kenya. Review of African political economy, 44, 559–576.

- Kamau, P., Onyango, G., and Salau, T., 2022. Kenyans cite criminal activity, lack of respect, and corruption among police failings. Accra, Ghana: Afrobarometer.

- Kelling, G.L., and Coles, C.M., 1997. Fixing broken windows: Restoring order and reducing crime in our communities. New York: Simon and Schuster.

- Kimari, W, 2017. 'Nai-Rob-Me’ ‘Nai-Bef-Me’ ‘Nai-Shanty’: Historizing space-subjectivity connections in Nairobi from its ruins. Toronto: York University.

- Kioko, E.M., 2017. Conflict resolution and crime surveillance in Kenya. Africa spectrum, 52, 3–32.

- Kivoi, D.L., and Mbae, C.G., 2013. The Achilles’ heel of police reforms in Kenya. Social sciences, 2, 189–194.

- Lid, S., and Okwany, C.C.O., 2020. Protecting the citizenry – or an instrument for surveillance? The development of community-oriented policing in Kenya. Journal of human security, 16, 44–54.

- Lind, J., Mutahi, P., and Oosterom, M., 2017. ‘Killing a mosquito with a hammer’: Al-Shabaab violence and state security responses in Kenya. Peacebuilding, 5, 118–135.

- Logan, C., Sanny, J.A.-N., and Katenda, L., 2022. Perceptions are bad, reality is worse: Citizens report widespread predation by African police. Accra, Ghana: Afrobarometer.

- Magadi, M.A., 2017. Understanding the urban–rural disparity in HIV and poverty nexus: The case of Kenya. Journal of public health, 39, e63–e72.

- Mamdani, M., 1996. Citizen and subject: Contemporary Africa and the legacy of late colonialism. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Mbuba, J.M., 2018. Devolution without devolution: centralized police service implications in a decentralized government in Kenya. Africology: The journal of Pan African studies, 11, 165–181.

- Mbuba, J.M., and Mugambi, F.N., 2011. Approaches to crime control and order maintenance in transitional societies: The role of village headmen, chiefs, sub-chiefs and administration police in rural Kenya. African journal of criminology and justice studies, 4, 1.

- Meth, P., et al., 2021. Conceptualizing African urban peripheries. International journal of urban and regional research, 45, 985–1007.

- Mkutu, K., 2008. Guns & governance in the Rift Valley: Pastoralist conflict & small arms. Oxford: James Currey.

- Mkutu, K., 2018. Security governance in East Africa: Pictures of policing from the ground. London: Lexington.

- Moser, C., and Mcilwaine, C., 2014. New frontiers in twenty-first century urban conflict and violence. Environment and urbanization, 26, 331–344.

- Mutahi, P., 2018. Hybrid security governance in Nairobi’s informal settlements. In: K. Mkutu, ed. Security governance in East Africa: Pictures of policing from the ground. London: Lexington Books, 59–78.

- Mutahi, P. 2021. Statehood, sovereignty and identities: exploring policing in Kenya’s informal settlements of Mathare and Kaptembwo. Thesis (PhD). University of Edinburgh.

- Mutahi, N., Micheni, M., and Lake, M., 2023. The godfather provides: Enduring corruption and organizational hierarchy in the Kenyan police service. Governance, 36, 401–419.

- Ndoma, S., 2020. COVID-19 lockdown: Zimbabweans trust police and military, but not enough to criticize them. Accra, Ghana: Afrobarometer.

- Nilsson, M., and Jonsson, C., 2023. Building relational peace: Police-community relations in post-accord Colombia. Policing and society, 33, 518–536.

- Nofziger, S., and Williams, L.S., 2005. Perceptions of police and safety in a small town. Police quarterly, 8, 248–270.

- OECD/SWAC. 2023. Africapolis: country report Kenya.

- Oliveira, T.R., et al., 2021. Are trustworthiness and legitimacy ‘hard to win, easy to lose’? A longitudinal test of the asymmetry thesis of police-citizen contact. Journal of quantitative criminology, 37, 1003–1045.

- Osse, A., 2016. Police reform in Kenya: A process of ‘meddling through’. Policing and society, 26, 907–924.

- Price, M., et al., 2016. Hustling for security: Managing plural security in Nairobi’s poor urban settlement. The Hague: Plural Security Insights – Clingendael Conflict Research Unit.

- Prine, R.K., Ballard, C., and Robinson, D.M., 2001. Perceptions of community policing in a small town. American journal of criminal justice, 25, 211–221.

- Raleigh, C., et al., 2010. Introducing ACLED: An armed conflict location and event dataset. Journal of peace research, 47, 651–660.

- Resnick, D., 2011. In the shadow of the city: Africa’s urban poor in opposition strongholds. The journal of modern African studies, 49, 141–166.

- Ruddell, R., and O’connor, C., 2022. What do the rural folks think? Perceptions of police performance. Policing: a journal of policy and practice, 16, 107–121.

- Ruteere, M., 2011. More than political tools. African security review, 20, 11–20.

- Ruteere, M., et al., 2013. Missing the point: Violence reduction and policy misadventures in Nairobi’s poor neighbourhoods. Brighton: Institute of Development Studies.

- Ruteere, M., and Pommerolle, M.E., 2003. Democratizing security or decentralizing repression? The ambiguities of community policing in Kenya. African affairs, 102, 587–604.

- Saferworld. 2021. Why peace remains elusive as Kenya prepares for the 2022 general elections. https://www.saferworld.org.uk/long-reads/why-peace-remains-elusive-as-kenya-prepares-for-the-2022-general-elections [Accessed 13 Mar 2022].

- Sanny, J.A.-N., and Logan, C., 2020. Citizens’ negative perceptions of police extend well beyond Nigeria’s #EndSARS. Accra, Ghana: Afrobarometer.

- Simon, D., 2008. Urban environments: Issues on the peri-urban fringe. Annual review of environment and resources, 33, 167–185.

- Simone, A., 2004. Critical dimentions of urban life in Africa. In: T. Falola, and S.J. Salm, eds. Globalization and urbanization in Africa. Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press, 11–50.

- Skilling, L., 2016. Community policing in Kenya: The application of democratic policing principles. The police journal, 89, 3–17.

- Skogan, W.G., 1984. Reporting crimes to the police: The status of world research. Journal of research in crime and delinquency, 21, 113–137.

- Skogan, W.G., 2006. Asymmetry in the impact of encounters with police. Policing and society, 16, 99–126.

- Sunshine, J., and Tyler, T.R., 2003. The role of procedural justice and legitimacy in shaping public support for policing. Law & society review, 37, 513–548.

- Tankebe, J., 2009. Public cooperation with the police in Ghana: Does procedural fairness matter? Criminology, 47, 1265–1293.

- Tankebe, J., 2010. Public confidence in the police: Testing the effects of public experiences of police corruption in Ghana. British journal of criminology, 50, 296–319.

- Tankebe, J., 2013. Viewing things differently: the dimensions of public perceptions of police legitimacy. Criminology, 51, 103–135.

- Thomas, C.W., and Hyman, J.M., 1977. Perceptions of crime, fear of victimization, and public perceptions of police performance. Journal of police science administration, 5, 305–317.

- Topping, J.R., 2008. Community policing in Northern Ireland: A resistance narrative. Policing and society, 18, 377–396.

- Tyler, T.R., 2003. Procedural justice, legitimacy, and the effective rule of law. Crime and justice, 30, 283–357.

- Tyler, T.R., 2004. Enhancing police legitimacy. The annals of the American academy of political and social science, 593, 84–99.

- UNDESA, 2018. World urbanization prospects 2018: highlights. New York: United Nations.

- Van Stapele, N., 2016. ‘We are not Kenyans’: Extra-judicial killings, manhood and citizenship in Mathare, a Nairobi ghetto. Conflict, security & development, 16, 301–325.

- Van Stapele, N., 2020. Police killings and the vicissitudes of borders and bounding orders in Mathare, Nairobi. Epd: society and space, 38, 417–435.

- Van Tongeren, P., 2013. Potential cornerstone of infrastructures for peace? How local peace committees can make a difference. Peacebuilding, 1, 39–60.

- Wairuri, K., 2022. Thieves should not live amongst people’: Under-protection and popular support for police violence in Nairobi. African affairs, 121, 61–79.

- Wang, S.-Y.K., and Sun, I.Y., 2020. A comparative study of rural and urban residents’ trust in police in Taiwan. International criminal justice review, 30, 197–218.

- Weisheit, R.A., Wells, L.E., and Falcone, D.N., 1995. Crime and policing in rural and small-town America: An overview of the issues. Rockville M.D.: National Institute of Justice.

- Wiesmann, U.M., Kiteme, B., and Mwangi, Z., 2016. Socio-economic atlas of Kenya: Depicting the national population census by county and sub-location. Nairobi: KNBS, CETRAD, CDE.