ABSTRACT

Technological change has brought a new dimension to the interaction between civic protest and policing in post-Soviet societies. Social media has had a revolutionary impact on protests during the last decade, mobilising citizens to resist state corruption and despotism, notably in states like Armenia, the Republic of Moldova and Belarus. Enhanced surveillance techniques and new communication channels have, at the same time, changed policing techniques and the modes of interaction between citizens and the police. This article examines the dynamics of transformed protest and policing practices, particularly of public order police, in the context of digitisation and social/political protest and change. It sheds light on the transformation of citizen-police relations and, ultimately, on the repercussions this has on the respective polities. The principal findings of the paper reveal that digital technology has been an important element in the evolution of practices of policing and police reform across the region. Yet, it is only one aspect of many in the somewhat divergent development of citizen-police relations. So far, it has produced rather negative effects instead of having been conducive to the mentality and ethos of the police. The disconnect between people and the police remains large in societies across the region.

Introduction

Digital technology and social media have fundamentally revolutionised civic activism and protest as well as the interaction between citizens and police in many parts of the world, including post-Soviet societies. Some observers have cautioned that the impact and scale of the ‘digital turn’ should not be overestimated and that this trend could serve undemocratic forces better than it does democratic ones (see Youmans and York Citation2012, Chenoweth Citation2016, Gohdes Citation2020). Yet, civic initiatives that base their activities on the use of information communication technology (ICT) have advanced and added several new aspects to previous forms of activism. These include better organisational capacities, more flexible action, faster protest mobilisation and wider political participation (Youngs Citation2019, p. 83). From the point of view of ruling regimes and governments, protests have become less predictable, more difficult to contain and thus a potential problem for riot police forces, badly skilled in crowd controlling and poorly educated in basic citizen rights. Protest represents only one way of expressing social grievances, yet it is the most visible form in which state power structures and citizens directly confront each other.

While the role of social media in civic activities and protest mobilisation is indisputable and extensively studied, the question of whether and how digitisation has transformed the citizen-police relationship,Footnote1 protest policing,Footnote2 and the management of protest activities by the police has been explored to a lesser degree (for a good overview of the existing literature, see Walsh and O'Connor Citation2018). Public order institutions and riot police have begun to engage in a mutual learning process with citizens and protesters in response to new capabilities and digital standards, especially with regard to social media. ICT has hence not only helped civic activists to enhance their organisational capacity but also empowered state power structures to improve their surveillance techniques and abilities to control and contain social movement activities.

State power structures, especially in authoritarian contexts, have an interest in keeping allegedly subversive elements at bay. The police’s spectrum of tools and tactics in the digital age has broadened and ranges from de-escalating communication via social media to military-like information warfare, in which demonstrators are likened to enemy forces. Monitoring and surveillance technologies are part of a wider trend towards the use of technology and the informatisation of protest policing (Ullrich and Knopp Citation2018, regarding other new tactics of protest policing, see Gillham and Noakes Citation2007, Wood Citation2014). Among others, video surveillance plays an important role in today’s selective protest policing styles (Della Porta and Reiter Citation1998).

This notwithstanding, protesters and ordinary citizens, who are affected by surveillance, are not passive objects of power politics either (Ullrich and Knopp Citation2018, p. 186). While state power structures control activists through surveillance, the mirror concept of countersurveillance/sousveillance, in which citizens monitor authorities, has also gained currency in the context of the antisurveillance agenda (Bradshaw Citation2013, Youngs Citation2019, p. 86). ‘Sousveillance’ is surveillance ‘from below’ with the intention of documenting events, including police conduct, from the protesters’ perspective with the possible use of the data to publicise police misbehaviour or file charges (Ullrich and Knopp Citation2018, p. 190). Sousveillance practised collectively in an organised manner, also known as ‘copwatch’ (Schaefer and Steinmetz Citation2014, Ullrich and Knopp Citation2018), is used to make the excessive use of force by the police more visible to the public and subject the behaviour of the police to public scrutiny. It can also have negative repercussions for protesters themselves (Wilson Citation2012).

Based on a comparative analysis of three post-Soviet societies (Armenia and Moldova with Belarus as a contrasting case) that have seen major instances of ‘digitised’ protest over the last decade, this article explores the implications of digitisation for citizen-police relations and the respective polities. The research questions to be addressed are: (1) To what extent has the ‘digital turn’ affected mobilisation and demobilisation/ suppression by the police during instances of social/political protest?; and (2) What are the implications of this for the citizen-police relationship in the selected country cases and, ultimately, for state power structures and the ruling regime in times of change?

The paper starts off with a theoretical and regional contextualisation of citizen-police relations. By identifying the principal factors determining protest policing in the digital age, the study illustrates that, beyond the Soviet legacy, a conglomerate of factors determines policing techniques and, ultimately, interactions between police and protesters in post-Soviet societies today. The next part provides details of the data and methodology used in the study. The main part offers a comparative analysis of how digitisation, social media affinity and the increased use of surveillance and sousveillance have transformed policing practices and the interaction between citizens and the police in the region. This is done against the background of selected instances of protest and change, contrasting the Moldovan and Armenian cases with the Belarusian case. Particular consideration will be given to past reform endeavours or the lack thereof and questions of loyalty. The paper concludes with general findings on evolving policing practices, effects on the citizen-police relationship and the implications of that for the respective polities.

Contextualising citizen-police relations theoretically and regionally

The impact of macro-level conditions, such as societal cleavages and state and political institutions, on citizen-police relations has been neglected in most contemporary research (Roché and Oberwittler Citation2017). The same holds true for micro-level aspects such as citizens’ perception and personal experiences of as well as their encounters with the police, which also affect this relationship. From the perspective of the police, the degree of their loyalty to the ruling government plays a key role as well.

The police is often conceived as one of the most visible manifestations of government authority and therefore its performance influences perceptions of the state and government (Hofstra Citation2012, p. 151). In many ways, police organisations and practices reflect the jurisdiction in which they were created and the context in which they operate (Roché and Fleming Citation2022, p. 259). The functioning of the police structure is therefore a litmus test for the functioning of the state at large.

Moreover, the assumption that there is a complex causal relationship between policing and regime transitions is not entirely new (Bayley Citation1971, Citation2006). Accordingly, international democratic assistance programmes often address the police institution in the context of support for reform projects, but often with an emphasis on material equipment rather than on a genuine transformation of the local law enforcement culture (Marat Citation2016, p. 333).

Empirical research on the relationship between the police and protesters is rare, and this is especially true for the post-Soviet region. Despite the fact that the police remain one of the least reformed post-Soviet institutions (Marat Citation2018), many post-Soviet countries have engaged over the last two decades in more or less successful attempts to reform the security sector (which includes also the armed forces, organs of domestic security, intelligence services etc). After the collapse of the Soviet Union, most countries in the region started with similar institutions of power. Armenia and Moldova, in particular, struggled with the Soviet legacy of centralised, hierarchical and militarised police forces dominated by reform-resistant traditionalists. Yet, it is no longer possible to speak of a coherent category of post-socialist policing (Aitchison Citation2016), although elements of securitisation still dominate, for instance during the quelling of protests. In the case of riot/public order police, reforms have often been a reaction to the excessive use of force during prior protests. Reform processes, be they triggered by internal or external factors, were primarily motivated by the goals of territorial reorganisation, capacity building and, notably, enhancing police legitimacy. The success of these efforts has varied considerably, and persisting problems have often been revealed to have similar causes across the region (Marat Citation2016, Citation2018). The reform of criminal justice and law enforcement structures has hence become a priority for the international community and organisations like the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and the European Union (EU), which are providing assistance with comprehensive security sector reforms in the region. However, this endeavour to change the mentality of an entire law enforcement organisation has proved more difficult than expected (Hofstra Citation2012, p. 151). Alongside these efforts, human rights NGOs and think tanks have become active, holding lectures and conducting training courses for members of the riot police on how to behave during mass protests. Here the focus has tended to be on improving the police’s capacity for reaction and intervention and on equipping it with forensic equipment and modern ICT systems. To date, however, these have usually been one-off measures (Interview Representative Helsinki Committee Armenia).

Local reformers and international experts have often cited Georgia as a blueprint for successful police reform. However, even in the Georgian case, there remain major deficiencies in democratic accountability, citizen trust and human rights (Di Puppo Citation2010, Kupatadze Citation2012, Light Citation2014). Thus, decades of police reform conducted with the help of the international community in the region have ultimately failed to transform the police from Soviet-style punitive institutions into service-oriented entities (Kupatadze Citation2012, Sholderer Citation2013, Marat Citation2016). Strong central oversight and patrimonial practices remain characteristic of many East European and post-Soviet states (Hensell Citation2012, Aitchison Citation2016, Marat Citation2018).

More than thirty years after the break-up of the Soviet Union, policing practices and techniques in the region are shaped by factors beyond a common Soviet legacy (Favarel-Garrigues Citation2003, Taylor Citation2014, Aitchison Citation2016). Especially with regard to public order policing, these factors range from political circumstances and conflict experience to the character of protests and variety in terms of protest actors and tactics (Atak and della Porta Citation2016, pp. 518–19). Finally, the Covid-19 pandemic and the War in Ukraine have affected reform endeavours and related civic and police activities, especially with regard to compliance with fundamental rights by police forces and additional funds to strengthen national defence.Footnote3

Data and methodology

This study compares citizen-police interactions in three countries on the meso level. The implications of digitisation are analysed on the micro level in terms of individual and collective attitudes towards police structures, as well as on the macro level in terms of their repercussions on the respective polities. To this end, the study draws on document analysis, online sources, opinion poll data and 65 problem-centred interviews,Footnote4 conducted by the author with various actor groups on the ground and via e-mail in Armenia, Moldova and Belarus between 2017 and 2020. Access to the field, especially to state institutions, was complicated. The emphasis was therefore on interviews with activists and members of civil society. They have experience in encountering the police during protests. Attempts to contact officials within the National Police/General Police Inspectorate and respective regulatory authorities were unsuccessful in both Moldova and Armenia, because the law enforcement sector remains a closed institution. Making contact with officials in Belarus was practically impossible.

Ethical considerations in this research are in line with general social sciences ethics standards. Each participant (interview respondent) of the scientific research project has received an information sheet prior to signing an informed consent. The information sheet contains information about the responsible investigator, the purpose of the research project, funding, risks and benefits involved in the participation, data processing, access, protection and storage. Furthermore, it contains information concerning the individual rights of the participant with regard to the voluntary character of participation, processed personal data and the possibility to lodge complaints with a data protection supervisory authority. The consent form, among others, asks for permission to record audio and to use quotes from the interview. The participants are assured confidentiality and anonymity with regard to the use of their personal data, as well as the possibility to get access to the research results /emanating publications.

With regard to the selection of cases, the post-Soviet region has already proved to be fertile ground for studying varieties of authoritarian policing (see, for example, Sholderer Citation2013, Marat Citation2018). It would seem logical then to examine the different ways in which new digital technologies have affected policing practices and, ultimately, perceptions of state power in societies across the region. In a comparative approach, I will show the effects of varieties in policing on the polities of respective country cases. In accordance with Sartori (Citation1970), the article thus strives to ensure a portability of concepts across the post-Soviet space, while at the same time avoiding conceptual stretching.

Moldova and Armenia were selected due to their common attributes: Soviet-era centralisation, similar population size, massive out-migration, deep-rooted corruption, and experience of long-standing unresolved conflict and a complex geopolitical situation. Due to extreme poverty, years of maladministration and failed governance, both states witnessed a significant increase in large-scale social protests during the last decade, which were violently suppressed by riot police. Both have subsequently undergone peaceful regime change, which, in the case of Moldova, was a direct result of democratic elections and, in Armenia, was democratically legitimated ex post facto in regular elections. Both states have – after a long track record of inconclusive, nominal police reform – re-embarked on a process of reforming the national police and internal security organs. In Belarus, by contrast, there have been no serious endeavours to reform the domestic law enforcement and security structures. Nevertheless, the country experienced the largest wave of mass protests in its history in the aftermath of a fraudulent presidential election in August 2020, with digital technologies playing a decisive role. Due to the lack of externally induced reforms in the past, a high degree of resistance to reform, and a pronounced loyalty by security forces to the current regime, Belarusian security structures come closest to the Soviet archetype. Belarus will thus represent a contrasting case to the other two.Footnote5

Armenia and Moldova score similarly (ranking mid-range) in both the Networked Readiness Index (NRI), published by the World Economic Forum, and the ICT Development Index, published by the United Nations International Telecommunication Union (ITU). This implies that the societies of those two countries have reached a certain level of ICT and internet competence, however have still a considerable backlog compared to the most advanced industrial economies (for example with regard to ICT concerning the number of households with a computer/internet access, fixed-broadband subscriptions per 100 inhabitants etc., with regard to NRI concerning investments in future technologies, development of digital governance and e-commerce). In 2017 (ICT) and 2019 (NRI), Belarus already ranked higher than other post-Soviet societies, reflecting its internet savvy society and high ICT potential. Both indices are frequently used tools for assessing the impact of ICT on the development and competitiveness of societies (see ).

Table 1. Network readiness and ICT development in Armenia, Moldova and Belarus 2022.

For the purpose of illustrating the transformation in citizen-police relations, three protest episodes have been chosen: (1) the 2015 ‘Electric Yerevan’ protests in Armenia; (2) the 2014–16 protests about a nationwide banking scandal in Moldova; and (3) the 2020 post-electoral protests in Belarus. All three waves of protest had various triggers but similar intrinsic driving forces. The so-called ‘Electric Yerevan’ protests in the capital of Armenia in 2015 were a culmination of social protests that had started in the mid-2000s. Tens of thousands of people demonstrated against a 17 per cent hike in electricity rates, demonstrating the mobilising potential of social grievances and discontent in Armenia. As a result of the protests, the government reversed the price hike and previously announced policies. In Moldova, social grievances represented a similar trigger for protest: The country was hit by a banking scandal in 2014 when $1 billion – approximately 12 per cent of Moldova’s gross domestic product – disappeared from the national banking system. Several wealthy oligarchs were publicly accused of the theft, but there were hardly any arrests and sentences. When the government announced that the population should bear the cost of returning the stolen billion, mass protests broke out that continued until spring 2016. By contrast, the Belarusian 2020 protests were predominantly driven by dissatisfaction with the political leadership. The August 2020 presidential election result was a reiteration of previous electoral victories of Belarusian president Aliaksandr Lukashenka. Due to the appearance of Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya as a credible and popular presidential challenger, large parts of society were not ready to accept the official outcome this time. The Belarusian regime struggled to maintain its power, arguably against the will of a majority of the population. Due to external support from Russia and the steadfast loyalty of its power structures, the regime managed to cement its hold on power.

Digital technology has been a decisive factor for the organisation and decentralised mobilisation of street protests in all three countries. All instances of protest represent decisive ruptures or turning points in terms of political developments and the evolution of protest and policing cultures in each country.

Citizen-police interaction in instances of protest and change

This article goes on the assumption that reliance by public order police on digital resources – namely, social media, new channels of communication and sophisticated surveillance techniques – has eroded, rather than strengthened, trust in and the legitimacy of state power structures. I argue that apart from the digital aspect and potentially other unknown factors, two variables are decisive for the engagement of public order police with the public: First, the extent and character of previous reform processes, and second, the degree of loyalty by the police apparatus towards the incumbent regime in times of national upheaval and change. In the following, I will discuss the role of the main determining factors for the evolving character of citizen-police interactions and relations in the present country cases.

Reform background

Despite a clear need and efforts to modernise police forces and supply them with digital technologies, this endeavour has so far only been successful in selected police units across the region. This is hardly surprising, given the fact that even ordinary police reform has stalled for years, and was most recently hampered by the Covid-19 pandemic (the official reason given by the respective authorities).

Police reform processes in Armenia and Moldova are more typical of those in the region than, for example, in Belarus, where hardly any reforms occurred, or in the better-studied Georgian case, which relied extensively on external support. The police in both Armenia and Moldova used to suffer from the legacies that plague most police structures in the former Soviet Union: a high degree of centralisation and hierarchisation, poor enforcement of human rights standards and a rigid training that emphasises legalism over practical skills and basic public-order management (Hofstra Citation2012, p. 151). Hence, at its core the police mentality remains rather militaristic, centralised and loyal towards the next highest level of the hierarchy rather than to the citizenry (see also Khechumyan and Kutnjak Ivković Citation2013).

In Armenia, one of the first reforms targeted the Ministry of Interior and the Ministry of National Security, which in 2003 were disbanded, merged and reorganised into a non-ministerial institution that eventually became the National Police of the Republic of Armenia and the National Security Service (NSS). Both were made directly accountable to the prime minister.Footnote6 As a result, the police came to be seen by the public as a type of ‘national guard’, extremely loyal to the ruling regime. Despite the reform and anti-corruption rhetoric of the current government, structural problems remain. After several relatively unsuccessful police development strategies in the past, the police reform process has regained pace since 2019, even though not all the old structures have been broken up. In one of Nikol Pashinyan’sFootnote7 first acts as prime minister, the heads of the National Police and NSS were replaced (Deutsche Welle Citation2018). Ever since then, Pashinyan has continued reshuffling staff and personalities in the security sector. His declarations culminated in the adoption of the ‘Strategy on Armenian Police Reform and 2020–2022 Action Plan’. Pashinyan himself stated that the main objective of this reform process was to reset relations between citizens and the police. Thus, the strategy’s main aim was to restore the public image of the police and address underlying issues that have led to police standoffs against their own tax-paying citizens (Roach Citation2019). One of the proposed structural changes was the creation of a Ministry of Internal Affairs and the tackling of corruption in the patrol police (Avetisyan Citation2020). The proposal to reorganise the police force as a newly empowered ministry is seen as an attempt to address the long-criticised direct control of the prime minister over the police and grant new oversight powers to the National Assembly instead (Dovich Citation2020).

The process of reforming Moldova’s internal affairs structure received a major impetus in 2009, when the country joined the EU’s Eastern Partnership project, which paved the way to the EU-Moldova Association Agreement. A National Action Plan was launched on the implementation of the Association Agreement, which identified the main problems in the domain of the Ministry of Internal Affairs (Promo-Lex Citation2021). The 2012 law on police activities led to the creation of the national police force as a separate entity, coordinated centrally by the General Police Inspectorate and responsible for internal security, public order, traffic, border security, and criminal investigations. Reforms in Moldova culminated in the 2016 National Strategy of Police Development, which included a public-order and security strategy. A major impetus for these renewed reform efforts was the wave of mass protests in 2014–2016 after Moldova’s banking scandal. The implementation of the Police Development Strategy (2016–2020) and the Public Order and Security Strategy (2017–2020) saw moderate progress in a number of areas,Footnote8 with Moldova thus meeting the EU policy conditions for the Police Budget Support Programme disbursements.Footnote9

The assistance with security sector reforms provided by international donors has been sporadic rather than sustained. Criticism has been notably directed towards the OSCE for ‘unwittingly promoting more sophisticated police repression’ (Light and Shahnazarian Citation2018, p. 21). The OSCE continues to see police reform as one of the ‘most imminent national reform priorities’.Footnote10

In Belarus, there used to be occasional public acknowledgements of the need to reform the police (Euroradio Citation2015). Efforts in 2012 (Belarus Security Blog Citation2012) to downsize and restructure the security services ostensibly responded to this. However, the real driver seems to have been the need to reduce expenses.

All three countries have well-armed interior troops,Footnote11 which are organised in a similar way to standard military units. For a long time, this Soviet heritage prevented the police from adapting easily to modern policing techniques. In addition, from the mid-2000s, police across the region began to face increasingly self-confident, fearless citizens and protest movements. The rise in civic activism triggered repeated instances of confrontation between citizens and the police. While certain groups in society made an effort to emancipate themselves from an overpowering and patronising state, state power structures, notably public order police, have often remained stuck in rigid reform-resistant and opaque structures.

New communication channels between the public and the police during street protests

In general, communication between the public and the police, in particular public order police, is a sensitive issue, even in established democracies. In the transitional democracies and authoritarian contexts of post-Soviet societies, it remains complicated, particularly because of a lack of adequate police training, especially with regard to ICT and social media. However, communication between protesters and the police has been revolutionised during the mass protests across the region over the last decade.

A strategy that emerged during ‘Electric Yerevan’, which activists later also adopted during the 2018 protests, was to establish a street-based counterculture characterised by horizontal (digital) ties and decentralised organisation as well as a direct communication link with the police. This culture was at odds with the mainstream political culture but with the hierarchical structures and top-down communication style of the police. Activists took decisions by consensus, often online. As a result, it became more and more difficult for public order police to follow and understand the unfolding events (Interview activist/political scientist from Yerevan). The police felt increasingly intimidated: ‘This was a cultural problem for [the police]. They just started thinking about new methods and about how to also become active on social networks themselves’ (Interview activist/political scientist from Yerevan). ‘Electric Yerevan’ paved the way for further protests. Thus in 2018, demonstrators and the police once again communicated directly with each other. The opposition leader at the time, Nikol Pashinyan, engaged in negotiations with former Deputy Chief of the National Police Valeri Osipyan in a tight cordon of press, protesters and police (News.am Citation2018). In the course of events, members of the police eventually defected to the side of the protesters.

In Moldova, in the context of the 2014 banking scandal, people from all regions of the small country took to the streets in the capital Chișinău. The authorities had no prior experience of protest techniques like occupy-style tent camps, etc., and riot police forces had difficulties preventing public buildings from being stormed. The protests were accompanied by unprecedented police violence and many arbitrary arrests, with people being held in custody for several days. This led to the increasing politicisation of the police and the Ministry of Interior in charge of the police. Influential here was the Democratic Party government, which at the time was headed by the most powerful Moldovan oligarch, Vladimir Plahotniuc. Since protesters blamed him for the banking scandal, Plahotniuc was a particular target of the uprising, dubbed anti-oligarch/anti-mafia protests. From the tent camp, civic activists communicated, similar to the 2009 ‘Twitter Revolution’,Footnote12 mainly via Twitter and various messaging services.

Digital technology was also crucial for mobilisation and demobilisation during the post-electoral protests in Belarus in 2020. Social media, especially instant messaging apps, enabled the timely exchange of information and fast and decentralised organisation of protesters. The authorities tried to respond to these developments by imposing periodic internet shutdowns. In an attempt to circumvent them, however, Belarusian protesters often announced the locations of their Sunday protest marches at short notice. The advantage of services like Telegram was that they bypassed these shutdowns.Footnote13 Various channels of the Telegram messenger, many, like the Warsaw-based Nexta,Footnote14 operating from abroad, became the only means of communication and coordination for the protesters. There were also attempts by the opposition and protesters on the streets to engage in non-violent communication with the police (online and offline) in order to persuade the riot police forces that what they were doing was ethically wrong and that it would be better for them to change sides. When arguments, emotions and flowers did not bring the wished-for results, protesters started threatening police forces and, as a last resort, they engaged in public shaming: trying to unmask them, pulling down balaclavas in order to film and identify them (for more information, see section below on surveillance/sousveillance).

In sum, communication has gained in speed and new channels of communication have altered the police-protester relationship. On the one hand, this has improved the way protest events are organised and mobilised and hampered demobilisation efforts by the police. On the other, it has fostered the spread of disinformation and attempts between citizens and police groups to discredit each other. On a positive note, direct communication between protesters and police has improved, making it more likely that tensions can be de-escalated during mass protests.

Mutual learning processes and surveillance/sousveillance

Interview partners in Moldova and Armenia regard recent developments and protests, such as the 2009 and 2014/2015 events in Moldova and the 2015 ‘Electric Yerevan’, as starting points in a learning process that engaged not only protesters and activists but also the police: ‘2015, Electric Yerevan, was a key turning point [because] what it really demonstrated was that the ordinary civic activist is no longer afraid [of the police], even of pre-trial detention’ (Interview Representative Regional Studies Center). ‘I meant that it [the Twitter Revolution of 2009] was started by young people […] And you probably already have been told this, that 2009 protests set a precedent for young people to start being sceptical [towards authorities]’ (Interview party activist, Dignity and Truth Party (Platforma DA)). In Armenia, further large protests took place in 2016. The police had by then already changed its strategies and, as a result, there were fewer brutal attacks on demonstrators. Instead, the police increasingly used digital surveillance, visited alleged instigators at their homes and detained them temporarily (Interview representative, former OSCE Mission to Armenia). Especially since 2015, the police in Moldova have reportedly started using technology to intercept the phone calls of activists, but were apparently not yet skilled enough to intercept digital chats (E-mail correspondence member of Occupy Guguţa, see also Preaşca et al. Citation2019). Similarly in Armenia, the National Assembly approved an amendment in 2020 that permits the police to conduct independent wiretapping operations on Armenian citizens’ telephones (Dovich Citation2020).

The wide dissemination of digital technology and social media has led to an increase in the use of surveillance/sousveillance by both the police and activists. When dealing with the police, grassroots activists like the members of the ‘Occupy Guguţa’Footnote15 initiative in Moldova actively engage in sousveillance: ‘All our actions bring police around us. And they film us, they take pictures very insistently […]. It is clearly a way to threaten or to make us feel intimidated’ (Interview member Occupy Guguţa). The Guguţa activists began to use social media as a weapon:

It was impressive, because we took pictures and we did that in a live video which went viral. And we do it every time and every time they fail. Like they stop us and they expect that they will get away with it. And it is quite ridiculous. (Interview member Occupy Guguţa)

The authorities and state power structures in Moldova seek to discredit these protests, which, in the eyes of the public and activists, only worsens their image further: ‘They discredit the protests in all their available mass media […] they spread fake news […]. It is worse than during Soviet times’ (Interview member Watchdog.md).

In Belarus, activists already reported a few years ago that police and intelligence officials film what happens during protests and cars accompany the rallies, equipped with mobile tracking devices in order to access the participants’ personal data (Interview Viasna representative). Moreover, the Belarusian militsiya has developed a tendency to scan the social network accounts of activists in order to identify compromising material in videos, likes and reposts. In some cases, they have found material (albeit old material) and declared it to be pornographic in order to construct a case for prosecution (Interview Viasna representative).

In spring 2017, during Belarus’ first large-scale social protest against Decree No. 3,Footnote16 several popular bloggers and activists began to stream live from the demonstration site. And when the militsiya tried to arrest the leaders of the political opposition, this was also streamed as well as brutal arrests and beatings, which thus became more visible (Interview activist ‘Our house’). This practice became even more common during the 2020 post-electoral protests in Belarus. Moreover, during scuffles protesters repeatedly tried to unmask members of the OMON Special Forces in order to film and identify them. With the help of a hacker group called ‘Belarusian cyber partisans’, activists published the names, addresses and phone numbers of about 1,000 Ministry of the Interior personnel who were allegedly responsible for quelling protests. Nexta helped to de-anonymise and expose the identities of political and security officials. This prompted a panicked reaction from the Ministry, which threatened to impose draconian penalties on those responsible for publishing the data.Footnote17 The Ministry in turn created a database containing all sorts of data and information about the protesters.

To sum up, the police and protesters have engaged in mutual learning processes, which have in most cases not led to improvements in the quality of policing and police-activist interaction in terms of ‘democratic policing’, but instead increased the level of mutual suspicion and distrust. Activists attempt to take revenge for the perceived paternalism of and arbitrary treatment by the police. Protesters use sousveillance as well as social media in order to discredit and put pressure on the police by raising public awareness of abuse and misconduct. In other words, civil society exercises its watchdog function.Footnote18

The public image of the police

The authorities in both Moldova and Armenia, and to a lesser degree even in Belarus, have been trying to improving the public image of their respective police structures. This has also been acknowledged by some of the most critical civil society actors, for example, in Moldova: ‘In the last eight months or so, they have developed new strategies like “Know your public order policemen or sector policeman”, [a] kind of community-based policing philosophy’ (Interview Representative Human rights organisation Credo). Apparently, many in the country sense a real will among the Moldovan police to improve its image. It has tried to discard its fusty image through its social media presence, which it uses to recruit young people, but also by getting the public to decide on the design of new police uniforms and caps (Sputnik Moldova Citation2019a). On its Facebook page, the Moldovan General Police Inspectorate shows that it also cares about peace in Ukraine and openly depicts symbols of solidarity with Ukraine.

The Armenian national police, too, has invested in its social media presence in recent years in order to boost outreach activities geared towards recruiting young people. Yet, in contrast to the Moldovan case, the image conveyed remains one of an old-fashioned, militaristic and rank-and-file institution with heroic pictures of parades and symbols like the national flag and police badges.

In Belarus, the power structures, including the militsiya, are not officially represented on what is regarded as Western social media. The security structures’ use of social media is therefore lopsided. According to activists, they read diligently what oppositional activists post on Twitter and occasionally even acknowledge that they obtained certain information, such as reports by the human rights movement, on social media (Interview Viasna representative). Belarusian militsiya (especially of the special forces OMON/AMAP) has always had a poor public image (REP activist, Bobruisk), but it gained notoriety in 2020 after violating laws and blatantly committing crimes.

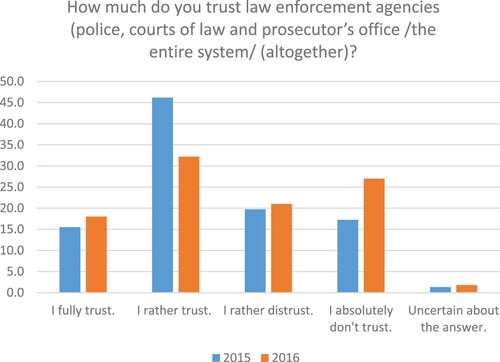

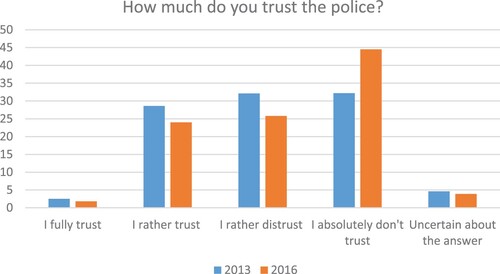

Trust in the police across the region – with few exceptions – used to be chronically low.Footnote19 The police still has a reputation as a repressive authority promoting the interests of the state. In Armenia, it suffered considerably after deadly riots during prolonged protests that followed a disputed presidential election in March 2008.Footnote20 The negative effects of public order policing became visible when the police ratings (trust in the police institution) dropped markedly after the protest waves of ‘Electric Yerevan’ in Armenia and the ‘bank scandal’ in Moldova respectively (see below and ).

Graph 1. Trust in law enforcement agencies in Armenia (2015/2016).

Source: Law enforcement arbitrariness index 2015–2016, Helsinki Citizens’ Assembly Vanadzor/Advanced Research Group (N = 1200).

Graph 2. Trust in the police in Moldova (2013/2016).

Source: Institute for Public Policy (IPP) Public Opinion Barometer (2013 N = 1144; 2016 N = 1143).

The situation in Armenia changed in 2015 when the foundation was laid for the Velvet Revolution of 2018. Around this time, a learning process started within the police, which has resulted in steadily increasing levels of trust in the police (generally, more than 50 per cent of the population express complete or some satisfaction with the police). Assessments of the new patrol police are largely positive across regions, age groups and political affiliations (International Republican Institute Citation2022). In Moldova, levels of trust in the police and other state authorities began to stagnate in the aftermath of the 2015 banking scandal and the subsequent state capture by local oligarchs. The percentage of citizens who admit to ‘somewhat’ or ‘highly distrusting’ the police is higher than the percentage of those who put ‘a great deal of trust’ in or ‘somewhat trust’ the police. This trend has persisted, despite the fact that a new Western-oriented government has been in power since 2021 (Institute for Public Policy Citation2013–Citation2016). In Belarus, trust in state power structures, notably the militsiya, has always been among the lowest in the region. Trust ratings did not, however, further diminish in 2021 (Douglas Citation2023 forthcoming).

Implications of political changes on police mentality

Since the beginning of the 2000s there have been repeated attempts in both Armenia and Moldova to ‘democratise’ police structures. However, the initial changes that occurred were considered mainly technical ones or material in terms of higher salaries etc. Changing political circumstances were then an important turning point for police reform in both countries. In Armenia, the mass protests around ‘Electric Yerevan’ in 2015 represented a milestone, putting the then authoritarian government in its place. Afterwards, the Armenian police, which had been more of a praetorian guard for the ruling elite, even more so than the military, became less confrontational in their interactions with protesters and citizens. Some began to speak of a learning process within the police, and civic activists began to interact in a more friendly manner with police officials. This culminated in the events of 2018 (‘Velvet Revolution’) when individual police officers started to defect and eventually switched sides.

In Armenia, the police used to be subordinate to the prime minister. Reinstating the Ministry of Internal Affairs, and thus adding another institutional layer, was intended to reduce the political exposure of the police hierarchy in order to de-politicise the police structure and make it more accountable (Dovich Citation2020). The Pashinyan government, however, made itself vulnerable by not conforming to the new standards and appointing, in January 2023, a new Minister of Internal Affairs who was not a civilian, but the former chief of the national police, widely regarded by civil society as reform-resistant and close to former authorities. In reaction to this appointment, several NGOs active in promoting police reform declared that they were pulling out of the Police Reform Coordination Council, which had been created in 2020 (Avanesov Citation2023, Avetisyan Citation2023). An Armenian human rights defender contended that in peaceful times, the police acts according to the law, but in times of crisis or moments of civic unrest, when authorities feel their power threatened, ‘the old pattern of public order policing and politically motivated action emerges again’ (Interview Representative Helsinki Committee Armenia).

In Moldova, the 2014 banking scandal in 2014 implied the country’s drift from the former model state of the Eastern Partnership towards a state captured by oligarchic interests, slowly recovering since the change of government in June 2019. The general political environment during this period (2014–2019) has been reflected in the politicisation of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, the General Police Inspectorate and the Moldovan police subordinate to it. Ever since 2019 some elements in the Moldovan police forces remained loyal to oligarchic ruler Vladimir Plahotniuc, even though a new government and political class were already in place.

In the past and especially since 2016, there have been several attempts to change the police education system, for example, by introducing training courses to raise awareness and shared knowledge about human rights, including in the digital sphere (Interview human rights lawyer). Yet, Moldovan experts see few changes in the police’s mentality. Moreover, several Moldovan activists and NGO representatives are critical of the support external donors gave to the corrupt regime in power before June 2019:

We would always appreciate any kind of support from our partners; however, this support in conditions of state capture may have unintended results. Strengthening captured law enforcement institutions, which work for the benefit of a small group of oligarchs, means throwing a big stick at civil society, at political and economic competitors of the oligarch. (IntervieRepresentative Transparency International Moldova)

In Belarus, the predominant ‘culture of impunity’ has poisoned citizen-police relations as well as state-society relations at large, due to the fact that no member of the militsiya has been held accountable for the serious crimes they committed. The lack of insignia or recognisable uniforms means that it is often impossible to identify perpetrators by their unit. The fact that the individual behind the mask or under the balaclava remains anonymous lowers their initial inhibitions against using force. ‘They know that they have carte blanche and that the state will back them up’ (Interview Representative Belarusian United Civic Party). According to observers, after a future regime change these forces could face prosecution, which is why they have an interest in keeping Lukashenka in power and maintaining their allegiance and loyalty (Douglas Citation2020).

To sum up: despite ambitious objectives, reform efforts over the last two decades have not managed to tackle the challenge of ‘digitised democratic policing’. Government plans have usually been hopelessly behind schedule, because many steps in the process of police reform have been suspended, only partially implemented, or not implemented at all. The most basic criticism of interview interlocutors was directed at a lack of behavioural change in how the police communicate with the public. A working relationship between the police and citizens is yet to be found in most post-Soviet societies. Another major challenge for all countries in the region will be to depoliticise the law enforcement agencies by making them more accountable to the citizenry instead of unquestioningly loyal to the incumbent political regime.

Conclusion

The digital turn has become an important element in the mobilisation and demobilisation of protest in the post-Soviet region and a determining factor in communications between the police and citizens. On the one hand, digital technology has certainly made it easier for police investigators to identify key figures and protest organisers in advance and, in some cases, (especially in Belarus) to use this information for pre-emptive arrests. On the other hand, it has become more difficult for the police to keep pace with the speed of organisation. Horizontal self-organisation of protesters on social media, especially via messaging services such as Telegram, has become standard in contemporary protests. Public assemblies are increasingly prepared and convened in a decentralised manner and resemble social gatherings with a festival-like atmosphere. For riot police forces, which, with their heavy riot gear and truncheons, are the antithesis of colourful crowds, it has become increasingly difficult to maintain their authority and keep the upper hand on unfolding events, both online and offline.

The reform processes in Moldova and Armenia were mostly initiated from outside and have stalled at times, but incremental changes have occurred. The Belarusian authorities and society completely lack this experience. Belarus as a contrasting case has demonstrated since 2020 the consequences of an absence of police reforms and unquestioned loyalty to the incumbent regime.

Digital technology has been an important element in the reform and professionalisation of police forces across the region. However, this has mainly entailed the provision of modern digital technology and equipment, especially to public order police, and often financed by Western donors or at least featuring technology from the West. Thus, after the launch of their respective reform processes, riot and public order police in both Moldova and Armenia initially became more violent in their reactions to public assemblies, especially after being trained in Western crowd control techniques. A shift in the informal practices, mentality and ethos of the police proved much more difficult. As we know from past research, informal institutions and practices are more resistant to change (Taylor Citation2014).

New and more direct communication channels between protesters and the police have contributed significantly to changing their relationship. Whether this has been for the better is, however, debatable. The disconnect between people and the police remains large in societies across the region. The use of surveillance techniques by the authorities and the diffuse spreading of disinformation by means of online tools has increased the potential for distrust between the two groups. Enhanced surveillance techniques (partly acquired with donor assistance) and failed attempts by the police to boost their public image via social media have been counterproductive and not increased public confidence in the police as a public security institution. Social and institutional trust can only be created and sustained in the real world. It is therefore not the police’s appearance on social media or communication skills that determine the public’s image of and trust in police structures, but the quality and intensity of the police’s direct interactions with citizens. Other than in Western states, where the majority of society still has a deeply entrenched trust in public administration and service (of which the police are perceived to be a part), social media and online image campaigns are more effective based on existing confidence. In the absence of general trust in the police, it would be worthwhile for local policy-makers in the region to reinvigorate projects such as community-based policing, which make police as an institution more accessible and tangible. Once citizens have again direct and first-hand experience in the interaction with their local police, they may become more susceptible also towards image campaigns that are launched by a less abstract and more familiar institution. As we know from exemplary cases like Georgia, a good entry point for further reforms and the promotion of trust is the reform of the traffic police, with the goal to make it become more service-oriented and receptive to citizens’ needs.

Widespread personal experiences of disproportionate state-sanctioned violence also affect how people think about their country’s leadership. This underpins the relations between the police and society, in a narrow sense, and between the state and society, in a broader sense. Trust in the police is, in some cases, indicative of trust in other state institutions. One reason for the police’s low trust ratings lies in the widespread view in societies across the region that the police remains the long arm of the government. The police in the selected countries and in the wider post-Soviet realm has had little opportunity to prove that it is an institution in its own right (in some cases, like Belarus, it is indeed not yet).

A process of learning through protest experience was evident for both the police and society in all three countries. From the two large waves of protest in Moldova and Armenia under scrutiny here, conclusions have been drawn by the respective authorities in terms of reforming, among others, public order police. In Belarus, such reflections and lessons learnt on the part of the authorities are still outstanding and a matter to be addressed by a potential future government. Public order and riot police forces in particular have found it difficult to improve their public image and are often still seen as a partisan group loyal to the ruling power.

From the preceding analysis of the selected cases, we can draw some general conclusions on the implications of changing protest and policing techniques in the digital age on citizen-police relations and the respective polities in times of change. below illustrates how the determining factors, digitisation, past efforts to reform security structures, loyalty of this very sector to the incumbent, and finally the trust level in the police have found expression in the nature of protest mobilisation and demobilisation by state power structures (implications for citizen-police relations and the respective polities in the last row).

Table 2. Implications of changing protest and policing techniques in the digital age for citizen-police relations and polities.

The selected cases are a good illustration of how ponderous institutional change in the post-Soviet security sectors still is. The cases clearly show that the digital turn is only one aspect of many in a cumbersome reform process, which can have positive effects, but which, because of a low level of implementation, has so far produced mainly negative ones. Citizen-police relations in former Soviet countries remains a sensitive political issue, particularly in the digital age. It depends very much on political circumstances and on how political leaders deal with the law enforcement challenge. Windows of opportunity have been missed in both Armenia (2018/2019) and Moldova (August 2021) following a change of power. In Belarus, there has never been a viable citizen-police relationship, and any potential for that was utterly destroyed in the 2020 post-electoral protests. Events have clearly shown that the current Belarusian regime would no longer be in power had it not been for the deep-rooted loyalty and obedience of its security structures (and background support from the Russian Federation).

So far, the digital turn has been more of an obstacle than a resource for the police structures in the region. Yet, looking ahead, it will be vital to take it into consideration as one of several basic elements (next to corruption prevention, decentralisation, demilitarisation, etc.) for improving relations between the police and the public and tackling the pending reform processes head on.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 In contrast to the pertinent literature (see e.g. Roché and Oberwittler Citation2017), this contribution deliberately chooses to speak of ‘citizen-police relations’, as opposed to ‘police-citizen relations’, starting from the premise that, especially in authoritarian contexts, it is the citizen’s perception that defines the relationship.

2 Protest or public order policing refers to the ways in which the police handles protest events. While activists consider it a form of repression, state authorities usually see it as a means to guarantee law and order (Della Porta and Reiter Citation1998, p. 1).

3 European Commission, The EU provides €36.4 million to tackle COVID-19 and support police reform in the Republic of Moldova, 28 September 2021, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_21_4923 (accessed 4 July 2022); European Commission, Informal Home Affairs Council: EU launches the Support Hub for Internal Security and Border Management in Moldova, 11 July 2022, https://ec.europa.eu/ commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_22_4462 (accessed 15 December 2022).

4 Documents that have been analysed concerned mainly the police and security sector reforms in the respective country cases, online sources drew primarily on media reports about current developments that have not found entry into the relevant literature yet, and the opinion poll data covers in particular national surveys on trust in and assessments of the performance of law enforcement entities. The 17 interviews, quoted in this paper, representa cross section of the larger sample of 65 interviews. They explicitly cover the topics digitisation, social media and surveillance.

5 Beyond that, the three countries have in common that they have all been part of the European Union’s Eastern Partnership Programme since 2009 (although Belarus abandoned it in June 2021).

6 Police of the Republic of Armenia, Police History: https://www.police.am/en/about/history.html (accessed 16 December 2022).

7 Nikol Pashinyan, former opposition leader and MP, came to power in 2018 as a result of the so-called ‘Velvet Revolution’ and a democratic election confirming it. He has been governing the country since then, but lost much momentum and support in the course of the 2020 44-Day War between Armenia and Azerbaijan over Nagorny Karabakh.

8 Final findings of Promo-LEX Association on the implementation of Police Reform, The European Union for the Republic of Moldova, 12 January 2021, https://eu4moldova.eu/final-findings-of-promo-lex-association-on-the-implementation-of-police-reform/ (assessed 16 December 2022).

9 European Commission/High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, Association Implementation Report on the Republic of Moldova, 13 October 2021, https://www.eeas.europa.eu/sites/default/ files/swd_2021_295_f1_joint_staff_working_paper_en_v2_p1_1535649.pdf (assessed 16 December 2022).

10 OSCE together with international partners supports project on police reform in Armenia, 26 January 2022, https://www.osce.org/secretariat/510704 (accessed 16 December 2022).

11 In Armenia, the so-called red berets, or Special Interior Forces of Armenia, have taken on a role comparable to the Soviet-era OMON special forces. They are responsible for crowd control and act as riot police during mass protests. Public order in Moldova continues to be maintained through a dual system of police special forces and carabineri. Carabineri are a paramilitary gendarmerie-type force, tasked with ensuring public order and protecting state buildings (Ostaf Citation2009, p. 12). Public order police officers belong either to the public order sections of the district police commissariats, the General Police Inspectorate, or the patrolling and sentinel unit Scut. In exceptional situations, public order is maintained by Fulger units – police special forces battalions – assisted by carabineri. The Belarusian OMON units act as the country’s riot police, at times supported by Interior Ministry troops and operating under the Ministry’s supervision. They gained notoriety for their indiscriminate brutality during the crackdown on post-electoral protests in 2020.

12 In 2009, civil unrest broke out after the parliamentary election and four people died as result of the turmoil and violent clashes between the police and demonstrators. These anti-governments protests, where many protesters had mobilised and organised themselves on Twitter, were later dubbed the ‘Twitter revolution’.

13 These channels function through built-in blocking-bypass mechanisms and additional proxy servers.

14 ‘Nexta now’ has more than 2.5 million subscribers; for more information, see Hurska (Citation2020).

15 ‘Occupy Guguţa’ is a grassroots movement that emerged in 2018, at the time with the purpose of occupying a Soviet-era children’s café in one of Chișinău’s central parks to prevent the demolition of the building. The property has since been bought by an investor who plans to erect a new business centre there. The group became increasingly politicised and got involved in the protests against Moldova’s oligarchic structures.

16 The decree was supposed to prevent so-called social parasitism, but effectively sanctioned the unemployed.

17 Belarusian Cyber Partisans Declared War on Lukashenka's Regime, Charter 97, 16 September 2020, https://charter97.org/en/news/2020/9/16/393340/ (accessed 16 December 2022).

18 While the police has to strike a balance between maintaining public order and respecting fundamental liberties, civic activists face the challenge of acting in a commensurate way, by maintaining their democratic right to monitor state institutions and, at the same time, respecting the personal rights of police officers.

19 See, for example, public opinion polls by the International Republican Institute and the Caucasus Barometer.

20 Mass protests were held in the wake of the Armenian presidential election in March 2008. Supporters of the unsuccessful presidential candidate and first president of Armenia, Levon Ter-Petrosyan, protested against allegedly fraudulent election results. Thousands of demonstrators mobilised in Yerevan’s Freedom Square, and after nine days of peaceful protests, on 1 March, the national police dispersed the protesters. Ten people were killed.

References

- Aitchison, A., 2016. Policing after state socialism. In: B. Bradford, B. Jauregui, I. Loader, and J. Steinberg, eds. The sage handbook of global policing. Los Angeles: Sage, 320–336.

- Atak, K. and della Porta, D., 2016. Towards a global control? Protest and policing in a new century. In: B. Bradford, B. Jauregui, I. Loader, and J. Steinberg, eds. The Sage handbook of global policing. Los Angeles: Sage, 515–534.

- Avanesov, A. 2023. Coordinating council for police reforms stops working – NGOs. Arminfo, 11 January, Available from: https://arminfo.info/full_news.php?id=73844&lang=3 [Accessed 27 January 2023].

- Avetisyan, A. 2020. Police as public servants: a new Armenian model? EVN Report, 2 July, Available from: https://evnreport.com/politics/police-as-public-servants-a-new-armenian-model/ [Accessed 16 December 2022].

- Avetisyan, A. 2023. Backlash after Pashinyan appoints ‘childhood friend’ as Armenia’s Interior Minister, OC Media, 10 January, Available from: https://oc-media.org/backlash-after-pashinyan-appoints-childhood-friend-as-armenias-interior-minister/ [Accessed 27 January 2023].

- Bayley, D.H., 1971. The police and political change in comparative perspective. Law & society review, 6 (1), 91–112.

- Bayley, D.H., 2006. Changing the guard: developing democratic police abroad. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Belarus Security Blog. 2012. Reforma MVD: vozmozhnye napravleniya, 4 September, Available from: https://bsblog.info/reforma-mvd-vozmozhnyie-napravleniya/ [Accessed 16 December 2022].

- Bradshaw, E., 2013. This is what a police state looks like: sousveillance, direct action and the anti-corporate globalization movement. Critical criminology, 21 (4), 447–461.

- Chenoweth, E. 2016. How social media helps dictators. Foreign Policy, 16 November, Available from: https://foreignpolicy.com/2016/11/16/how-social-media-helps-dictators/ [Accessed 16 December 2022].

- Della Porta, D. and Reiter, H., 1998. Policing protest: The control of mass demonstrations in western democracies. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Deutsche Welle. 2018. Armenia’s PM axes police and security chiefs, 5 November, Available from: https://www.dw.com/en/armenias-pm-pashinyan-axes-police-and-security-chiefs/a-43735331 [Accessed 16 December 2022].

- Di Puppo, L., 2010. Police reform in Georgia: cracks in an anti-corruption success story. U4 Practice Insight 2. Christian Michelsen Institute.

- Douglas, N. 2020. Die Loyalität des belarusischen Sicherheitsapparats bröckelt (noch) nicht. Belarus-Analysen No. 53/2020, Available from: https://www.laender-analysen.de/belarus-analysen/53/die-loyalitaet-des-belarusischen-sicherheitsapparats-broeckelt-noch-nicht/ [Accessed 16 December 2022].

- Douglas, N., 2023. The role of trust in Belarusian societal mobilisation (2020–2021). International journal of comparative sociology. Unpublished manuscript forthcoming.

- Dovich, M. 2020. Armenian Government embarks on police reform, proposes wide-ranging structural changes, Civilnet, 6 March, Available from: https://www.civilnet.am/en/news/381092/armenian-government-embarks-on-police-reform-proposes-wide-ranging-structural-changes/ (Accessed 16 December 2022].

- Euroradio. 2015. Glava MVD Belarusi: Reforma militsii prakticheski zavershena, 18 July, Available from: https://euroradio.fm/ru/glava-mvd-reforma-belorusskoy-milicii-prakticheski-zavershena [Accessed 16 December 2022].

- Favarel-Garrigues, G., 2003. Introduction. In: G. Favarel-Garrigues, ed. Criminalité, police et gouvernement : trajectoires post-communistes. Logiques politiques. Paris: Éditions L’Harmattan, 3–32.

- Gillham, P.F. and Noakes, J.A., 2007. “More than a march in a circle”: transgressive protests and the limits of negotiated management. Mobilization: An international journal, 12 (4), 341–357.

- Gohdes, A., 2020. Repression technology: internet accessibility and state violence. American journal of political science, 64 (3), 488–503.

- Hensell, S., 2012. The patrimonial logic of the police in Eastern Europe. Europe-Asia studies, 64 (5), 811–833.

- Hofstra, C., 2012. Police development activities of the OSCE in Armenia. OSCE yearbook, 17 (Nomos), 151–166.

- Hurska, A. 2020. What is Belarusian telegram channel NEXTA? Eurasia Daily Monitor, Jamestown Foundation, 17 (132), 23 September, Available from: https://jamestown.org/program/what-is-belarusian-telegram-channel-nexta/ [Accessed 16 December 2022].

- Infotag. 2020. Premier says the 2011–2012 police reform destroyed institute of community police officer. 20 January, Available from: http://www.infotag.md/populis-en/281899/ [Accessed 16 December 2022].

- Institute for Public Policy (IPP). 2013–2016. Republic of Moldova Public Opinion Barometer. Available from: http://bop.ipp.md/en [Accessed 19 January 2023].

- International Republican Institute. 2022. Center for insights in survey research, public opinion survey: residents of Armenia, June 2022, 9 September, Available from: https://www.iri.org/resources/public-opinion-survey-residents-of-armenia-june-2022/ [Accessed 19 January 2023].

- Khechumyan, A. and Kutnjak Ivković, S., 2013. The state of police integrity in Armenia: findings from the police integrity survey. Policing: an international journal of police strategies & management, 36 (1), 70–90.

- Kupatadze, A., 2012. Police reform in Georgia. Georgia: Center for Social Sciences, September 2012, Available from: http://css.ge/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/kupatadze_police_eng.pdf [Accessed 16 December 2022].

- Light, M., 2014. Police reforms in the Republic of Georgia: the convergence of domestic and foreign policy in an anti-corruption drive. Policing and society, 24 (3), 318–345.

- Light, M. and Shahnazarian, N., 2018. Parameters of police reform and non-reform in post-soviet regimes: the case of Armenia. Demokratizatsiya: The journal of post-Soviet democratization, 26 (1), 83–108.

- Marat, E., 2016. Reforming police in post-communist countries: international efforts, domestic heroes. Comparative politics, 48 (3), 333–352.

- Marat, E., 2018. The politics of police reform: society against the state in post-soviet countries. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- News.am. 2018. V Erevane demostranty nachali ocherednoe shestvie—politsiya nachala otvetnye destviya, 21 April. Available from: https://news.am/rus/news/447515.html [Accessed 16 December 2022].

- Noi.md. 2021. Politseiskie vozmushcheny initsiativoi PDS o povyshenii pensionnogo vozrasta, 21 September, https://noi.md/ru/obshhestvo/policejskie-vozmushheny-iniciativoj-pds-o-povyshenii-pensionnogo-vozrasta [Accessed 16 December 2022].

- Ostaf, S., 2009. Policy options for improvement of assembly policing management in Moldova. Resource Center for Human Rights, https://credo.md/?new_language=0&go=news&n=186 [Accessed 16 December 2022].

- Preaşca, I., Cuşchevici, C., and Sanduţa, I., 2019. The ministry of interceptions. RISE Moldova, 14 June. Available from: https://www.rise.md/english/the-ministry-of-interceptions/ [Accessed 16 December 2022].

- Promo-Lex. 2021. Civic monitoring of police reform in the Republic of Moldova, 2020 retrospective, 21 August. Available from: https://promolex.md/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/06-07-2021-FINAL-raport-nr-5-machetatENG.pdf [Accessed 16 December 2022].

- Roach, A.B. 2019. ‘The Police are Ours!’ – Armenia’s revolutionary police reform at a crossroads, OC Media, 21 January 2019, https://oc-media.org/features/the-police-are-ours-armenia-s-revolutionary-police-reform-at-a-crossroads/ [Accessed 16 December 2022].

- Roché, S. and Fleming, J., 2022. Cross-national research. A new frontier for police studies. Policing and society, 32 (3), 256–270.

- Roché, S. and Oberwittler, D., 2017. Towards a broader view of police–citizen relations. How societal cleavages and political contexts shape trust and distrust, legitimacy and illegitimacy. In: S. Roché and D. Oberwittler, eds. Police–citizen relations across the world: comparing sources and contexts of trust and legitimacy. Routledge, 3–26.

- Sartori, G., 1970. Concept misformation in comparative politics. The American political science review, 64, 1033–1053.

- Schaefer, B.P. and Steinmetz, K.F., 2014. Watching the watchers and McLuhan’s tetrad: the limits of cop-watching in the internet age. Surveillance & society, 12 (4), 502–515.

- Sholderer, O., 2013 September. The drivers of police reform: the cases of Georgia and Armenia. Ceu political science journal, 8 (3), 323–347.

- Sputnik Moldova. 2019a. Zhiteli Moldovy mogut sami vybrat’, kak budut vyglyadet’ politseiskie, 10 March. Available from: https://ru.sputnik.md/society/20190310/25111202/zhiteli-moldova-mogut-sami-vybrat-kak-budut-vyglyadet-politseyskie.html [Accessed 16 December 2022].

- Sputnik Moldova. 2019b. Eksklyusiv: zarplata politsii dolzhna vyrasti na 10% v 2020 godu, zayavil Boiku’, 26 November. Available from: https://ru.sputnik.md/society /20191126 /28342772/ exsclusiv-zarplata-politsii-vyrastet-na-10-v-2020-godu-zayavil-voicu.html [Accessed 16 December 2022].

- Taylor, B., 2014. From police state to police state? legacies and law enforcement in Russia. In: M. Beissinger and S. Kotkin, eds. Historical legacies of communism in Russia and Eastern Europe. New York: Cambridge University Press, 128–151.

- Ullrich, P. and Knopp, P., 2018. Protesters’ reactions to video surveillance of demonstrations: counter-moves, security cultures, and the spiral of surveillance and counter-surveillance. Surveillance & society, 16 (2), 183–202.

- Walsh, J. and O'Connor, C., 2018. Social media and policing: a review of recent research. Sociology compass, 13 (1), 1–14.

- Wilson, D., 2012. Counter-surveillance: protest and policing. Plymouth law and criminal justice review, 4, 33–42.

- Wood, L.J., 2014. Crisis and control. The militarization of protest policing. New York: Pluto Press.

- Youmans, W. and York, J., 2012. Social media and the activist toolkit: user agreements, corporate interests, and the information infrastructure of modern social movements. Journal of communication, 62 (2), 315–329.

- Youngs, R., 2019. Civic activism unleashed. New hope or false Dawn for democracy? New York: Oxford University Press.

Interviews

- Armenia

- Activist/political scientist, Yerevan, 11 April 2017.

- Representative, Regional Studies Center, Yerevan, 6 April 2017.

- Representative, Helsinki Committee Armenia, Yerevan, 6 April 2017.

- OSCE representative of former Mission to Armenia, Berlin, 27 March 2017.

- Moldova

- Representative, Transparency International, Chișinău, 1 December 2017.

- Former police officer (via Viber), 4 April 2019.

- Human rights lawyer, Chișinău, 30 November 2017.

- Representative, Institute for Public Policy (IPP), Chișinău, 27 February 2019.

- Member Occupy Guguţa, Chișinău, 26 February 2019.

- Member Occupy Guguţa (E-mail conversation), 12 September 2019.

- Member of Watchdog.md, Chișinău, 21 November 2017.

- Representative, Human rights organisation Credo, Chisinau, 23 November 2017.

- Party activist, Dignity and Truth Party (Platforma DA), Chișinău, 28 November 2017.

- Belarus

- Activist, Nash Dom, Minsk, 10 September 2017 (follow-up questions 2020).

- Representative, Belarusian United Civic Party, Minsk, 8 September 2017.

- Representative of REP Union, Bobruisk, 12 September 2017.

- Representative of Viasna, human rights organisation, Minsk, 13 September 2017.