ABSTRACT

Police investigators increasingly make use of forensic science in the investigation of crime. While there is considerable research on case outcomes following the use of forensic identification evidence (fingerprint and DNA evidence), few studies have explored how police investigators use these evidence types in their investigations. This study aimed to examine police investigators’ reasoning processes about the use of forensic identification evidence in volume crimes, such as burglary, to develop a decision-making framework that can be applied to the investigation of such crimes. Twenty-four police officers from three Australian police jurisdictions participated in semi-structured interviews that centred around a case scenario. Data were transcribed verbatim and analysed thematically. The findings highlight that police investigators’ decision-making is influenced by the requirement to meet the rules of evidence. Further, participants’ own experience and mentoring by more experienced colleagues influenced not only the decisions made in a case, but also the development of decision-making skills in the use of forensic evidence more broadly. A decision-making framework is proposed to explain and guide the use of forensic evidence in volume crime investigations. Overall, the findings suggest that the effective use of forensic identification evidence in volume crime investigations requires that police investigators engage actively in the decision-making process. Further research can explore ways to integrate the findings from this research into police practices.

Introduction

The decisions made by police investigators have flow-on effects in how a case proceeds through the justice system. Despite its importance to the criminal justice process, decision-making in police investigations is an under-researched area. Although police increasingly make use of forensic science in the investigation of crime, little research has examined investigative decisions about the use of such evidence (Julian et al. Citation2022). For example, while some studies have examined these issues in homicide investigations (Brookman et al. Citation2022, Brookman and Innes Citation2013, Kelty et al. Citation2015), for volume crime investigations, the focus of previous studies has been quantitative reviews on case outcomes associated with the use of forensic evidence at various stages of the criminal justice process (Burrows et al. Citation2005, Bradbury and Fiest Citation2005, Home Office Citation2007, Wullenweber and Giles Citation2021). These studies have highlighted the value to investigations of the use of rapid forensic evidence in providing a possible suspect (Spence et al. Citation2003, Bitzer Citation2016, Roman et al. Citation2008, Brown et al. Citation2014, Brown et al. Citation2016, Anderson et al. Citation2018, Brown Citation2021). They have also highlighted the importance of high performing crime scene investigators (CSI). Their selection of relevant and high-quality traces at the crime scene can help to minimise laboratory backlogs and cases are more likely to flow through the justice system (Ludwig et al. Citation2012, Ludwig et al. Citation2014).

However, many case processing studies have considered whether forensic science was used (Home Office Citation2007, Burrows et al., Citation2005), but not how it was used. In contrast to research on effective CSI performance, limited research exists on how police investigators think and to what extent their decision-making is influenced by forensic evidence in volume crime investigations. Research in Australian jurisdictions showed that substantial time elapsed from the identification (using fingerprints or DNA) to the arrest of a suspect (Bruenisholz et al., Citation2019). These findings suggest that not only is it important whether forensic science is used, but how it is used by investigators. Knowing how investigators make decisions using forensic identification evidence can guide training and the development of best practices that will lead to more consistent and effective practice in the use of forensic technology.

This paper reports the findings of a study of investigative decision-making about the use of forensic evidence in volume crime investigations. In contrast to previous studies of the use of forensic evidence in volume crime cases, this study uses a qualitative methodology to reveal complex social processes that influence the decisions about how such evidence is used – specifically in police investigations. It begins with a general overview of the application of the law in police investigative decision-making, including a discussion of the different models of the human reasoning process within which decision-making is framed. The paper then outlines the methodology of the study in which twenty-four police investigators from three Australian states participated. The findings shed light on the way forensic evidence directs the decision-making process, and result in a framework of abductive reasoning applied to volume crime investigations. The paper concludes with the implications for generating improvements in the use of forensic evidence in volume crime investigations, highlighting the importance of the nexus between law, science, policing and academia.

The role of police investigations and reasonable suspicion

The main aim of the law, exercised through the criminal justice system, is to maintain social order (Cooper Citation2016). A range of stakeholders – police officers, judges, lawyers, forensic scientists, policymakers, law makers and researchers – support this aim by contributing to various stages of the criminal justice process and upholding (or scrutinising, depending on their role) the integrity of procedures within the system. As the primary actors in the early stage of the criminal justice process, police investigators evaluate the evidence associated with a crime to develop the narrative around how and why the crime occurred, and to identify persons of interest and possible suspects and to eliminate people from enquiries. Notably, the answers to these questions of who, how, and why are important to those in other roles in the legal system (Ask and Alison Citation2010).

To appreciate the influences on investigators, it is necessary to understand how they conduct their fact-finding process in support of the rule of law (Artello and Albanese Citation2019). Essential to the investigative process is an understanding that the burden of proof is borne by the prosecution and thereby also experienced by police investigators who must prepare a brief of evidence, obtaining proof of each element of an offence and disproof of any exception, justification or excuse. Under the standard rule of law, before a person can be charged and prosecuted, using legislated police discretionary powers, the investigator gathers and interprets evidence and frames the narrative around a person suspected of wrongdoing. The prosecutor determines whether there is sufficient evidence to proceed to court and decides what charges should be laid. Before a trial takes place, it must be decided whether there are reasonable prospects of securing a conviction. And before a person can be convicted, the court must be convinced of the guilt of the accused person beyond reasonable doubt (Sheppard Citation2002). Decisions made within a police investigation therefore influence the course of the case as it progresses through the system.

The sources of police discretion lie with the legal powers they are given, recognised in specific sections of the criminal law (e.g. Police Powers and Responsibilities Acts) to undertake certain investigative actions (Corsianos Citation2010). Investigators’ decision-making processes rely on the ability to use these legal powers once the investigator forms a reasonable suspicion about a person. Reasonable suspicion is an objectively justifiable suspicion that a person is implicated in the offence under investigation (Gehl and Plecas Citation2016). Determining reasonable suspicion is more than a ‘hunch’; it requires cognitive processing to consider both subjective and objective assessments, pointing to specific facts or circumstances. There must be a rational connection between the supporting admissible material and the suspicion but not at a level that suggests probably guilt (The State of South Australia v Nguyen 2013, Terry v Ohio 1968). This threshold is commonly defined as ‘suspicion in the mind of a reasonable person’. The notion of reasonable suspicion allows police officers to undertake investigative actions including conducting searches or making arrests.

Police investigative decision-making

Although police investigators are often portrayed in entertainment media (Brandl and Frank Citation1994), the skills of an investigator are not well understood. In fact, criminal investigation has received relatively little research attention compared with other areas of policing (Westera et al. Citation2013). Early research into investigations determined that rather than being solved through hard work, ‘the cases that get cleared are primarily the easy ones to solve’ (Greenwood et al. Citation1977 cited in Brandl and Frank Citation1994, p. 151). The relationship between time spent investigating and the outcome was the strongest in cases with moderate suspect information – and the bulk of the investigative work was applied to identifying the suspect (Brandl and Frank Citation1994, Eck Citation1983).

Investigative decision-making has received some more recent research attention. In the United Kingdom semi-structured interviews with forty senior investigating officers (SIOs) on how they spent their time to achieve productive results, identified twenty-two core skills for effective performance in their roles (Smith and Flanagan Citation2000). While decision-making was a skill identified and placed in the ‘investigative ability’ cluster, the research did not explore what constituted good decision-making skills. To evaluate Smith and Flanagan’s study in the Australian context, Westera et al. (Citation2013) undertook semi-structured interviews with thirty detectives from five police services in Australia. The skill of decision-making was defined as ‘analys[ing] information to make clear and logical decisions under pressure while remaining open-minded and flexible to respond to unfolding scenarios’ (Westera et al. Citation2013, p. 3). In this study, decision-making was identified as a necessary skill in 70% of the interviews. The researchers concluded that decision-making was one of the top five skills necessary to be an effective investigator.

However, investigative decision-making can be influenced by factors outside the investigator’s awareness. Research has demonstrated that these influences include the decision-maker’s domain-specific knowledge, previous experiences, or pre-conceived biases, and the overall treatment of cases can be influenced by the nature of the criminal offences being investigated (Westera et al. Citation2013, Corsianos Citation2010, Brookman and Innes Citation2013). Brookman and Innes (Citation2013) aimed to determine the characteristics of a ‘good’ homicide investigation through semi-structured interviews with twenty-two detectives and field observations of investigations and training. They identified that for homicide investigations, investigators are guided by policies, systems, guidelines, legal requirements, and forensic and digital technology. They found that success reflected navigating these complex challenges when interviewing a suspect (Brookman and Innes Citation2013).

Researchers have also examined differences in levels of investigative expertise. For example, qualitative research involving in-depth interviews of fifty detectives in Canada aimed to assess the use of discretion in detective decision-making in high-profile investigations (Corsianos Citation2010). The study demonstrated the value of experience as while junior partners had autonomy in decision-making, they were actively encouraged to discuss and seek collective agreement on decisions. Notably, where the investigation had a high level of accountability, the involvement of more senior officers in the decision-making increased (Corsianos Citation2010). This reflects the valuing of knowledge associated with years of experience. The quality of investigative decisions made by detectives and novice police officers was further explored in a comparison of English and Norwegian police officers (Fahsing and Ask Citation2015). Their findings suggested that ‘professional experience is potentially beneficial to detectives’ ability to identify relevant investigative hypotheses and formulate appropriate lines of inquiry in criminal investigations’ (Fahsing and Ask Citation2015, p. 215). They theorised that the ability to make decisions to generate investigative hypotheses (i.e. what to investigate) and investigative actions (i.e. how to investigate) was valuable to the outcome of criminal investigations. The decision-making process involved complex human reasoning – not just experience (Fahsing and Ask Citation2015).

It has also been demonstrated that police officers apply different processes in different policing roles and in different circumstances. For example, patrol officers may use more intuitive cognition, whereas detectives may use more analytical cognition and may move between analysis and intuition depending on the task characteristics (Bonner Citation2018). Overall, the research suggests that investigators do not make isolated decisions. Rather, cognitive reasoning processes are used to interpret information in the context that it is presented, and to make investigative choices to assess the value, meaning and weight of the information to the case under investigation (Maegherman Citation2020, Bonner Citation2018).

Police investigative decision-making about forensic evidence

Several researchers have focused specifically on investigative decisions about the use of forensic evidence. As discussed above, while investigative decision-making requires the integration of various sources of data and knowledge, the processes of doing so are often ill-defined (Ribaux et al. Citation2016). In a review of crime scene management, Crispino (Citation2008) defined decision-making when using forensic evidence as a process of shifting between three methods of reasoning: induction, abduction and deduction, which are undertaken at different stages of the investigation. Inductive reasoning involves using existing knowledge or observations to make broad generalisations; in other words, using the known to predict the unknown (Heit Citation2000). Applying an inductive reasoning process is problematic in the forensic context as it effectively rules out investigative decision-making and rather jumps to conclusion forming. Deductive reasoning derives observations under a set of conditions or laws that cannot be questioned, starting with a set of general premises and drawing a specific conclusion (Crispino Citation2008). In these circumstances, a hypothesis may be supported by numerous deductive inferences, as an example given by Barrett (Citation2009) shows: The person who stole the money knew about its existence. The suspect knew about the money; therefore, he must be the offender.

However, according to several studies (Bitzer et al. Citation2016, Fahsing and Ask Citation2015, Brown Citation2021), investigating officers apply a primarily abductive human reasoning process. This involves ‘thorough problem recognition, problem framing and option generation all of which depend on the decision-maker’s domain-specific knowledge’ (Fahsing and Ask Citation2015, p. 205). The abductive reasoning process begins with an incomplete set of observations, namely, the various forms of evidence (forensic or otherwise). It involves making a ‘best guess’ with what is known (Barrett Citation2009). In logical terms, abduction is often proposed as the basic form of inference used to reconstruct what occurred: hypotheses must be developed from observations, with the understanding that there is more than one possible cause that can lead to the same observations. Discussing forensic scientists’ processing of a criminal case, Baechler et al. state that it ‘shifts progressively its emphasis from the development of hypotheses (through abduction) to the confirmation of them (through a more deductive approach)’ (Citation2020, p. 3). This approach suggests that both the abductive and the deductive reasoning process is applied to criminal cases, particularly when using forensic evidence. However, Baechler et al. (Citation2020) discussed the role of forensic science in general rather than the role of police investigators specifically.

An investigator’s abductive reasoning can incorporate the use of forensic evidence. For example, Moston and Engelberg (Citation2011) found that strong evidence against an accused person prior to interview often led to a confession. However, evidence types such as DNA, CCTV and fingerprints are perceived to be ‘more probative and influential on legal decision-making activities such as judgements on the reliability of the evidence, the likelihood the suspect is guilty and confidence in the legal outcome’ (Jang et al. Citation2020, p. 188). The strength of the evidence against a suspect differs between cases; it is contextual. A recent study undertaken in the UK using case data from 706 offences identified that contextual influences, such as location and moveability of the evidence play the biggest part in conversion of a detection into criminal charges (Wullenweber and Giles Citation2021). Investigators must distinguish between various types of information and not to over- or underestimate the evidential value of the investigative findings in a narrative (Ask and Alison Citation2010).

The present study

As the literature reviewed has highlighted, limited research has explored police investigators’ decision-making in general and about the use of forensic identification evidence specifically. The present study aimed to understand such decision-making and develop a model on the use of forensic evidence in volume crime investigations. It was anticipated that a qualitative study would provide insights into how and why investigators use forensic evidence in the ways that they do in volume crime investigations, adding to the body of knowledge on police use of forensic evidence. This study is part of a larger multi-methods research project examining the effectiveness of fingerprint and DNA evidence in volume crime investigations in Australia (Brown Citation2021).

Methods

Sample and participants

The primary source of information for this phase of the research was twenty-four semi-structured interviews with police investigators from three police organisations in Australia. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Tasmania Social Sciences Human Research Ethics Committee (H0016185). Approval for research was obtained from three Australian police organisations. The police organisations were identified as sites for the interviews based on their performance during an earlier benchmarking study on the investigation of burglary crimes in Australian jurisdictions (Brown et al. Citation2014). Specifically, the selected organisations had achieved the following results: the first had demonstrated the highest arrest rate from forensic evidence; the second had demonstrated a high arrest rate from DNA evidence; and the third had demonstrated top overall performance in the use of forensic evidence for volume crime investigations.

Each police organisation provided a contact person to liaise with the first author. The organisational contact person was responsible for locating potential participants with suitable experience in the investigation of volume crime and providing them with an information sheet and consent form. The contact from each organisation provided the researcher with contact details of prospective participants who had indicated their willingness to participate in the study. The first author arranged mutually suitable times for interviews.

All participants were police officers with current or previous relevant experience in the investigation of volume crimes. Six (25%) participants were female, the remaining 18 (75%) were male. Participants ranged in age from 24 to 56 years, with an average age of 35 years for female participants and 42 years for male participates. The length of time in policing ranged from 4 to 32 years, with the average length of service eight years for female participants and 18 years for male participants. This gender balance generally reflects the current composition in Australian policing, where women account for approximately 30% of the workforce with a lower average service time than men (Prenzler Citation2020, Keddie Citation2023). The level of investigative experience was diverse: some investigators were highly experienced across a range of investigation types and others were relatively new to volume crime investigation teams, with previous experience in general duties policing.

Data sources

Face-to-face semi-structured interviews were used to facilitate an in-depth understanding of participants’ experiences of decision-making. At the commencement of the interviews, participants were given a hypothetical burglary scenario (see ) as a stimulus for the discussion. Each outcome reflected different possibilities in the results of forensic analysis (suspect identification or otherwise from fingerprints or DNA), the location of forensic evidence (inside or outside), and the portability of the item containing forensic evidence (fixed or portable).

Table 1. Hypothetical burglary scenario.

An interview guide with open-ended questions was used to guide discussion. To gain insights into investigative strategies, each participant was asked to walk the interviewer through what they would do to conduct their investigation for each of the forensic outcomes (A, B, C; see ) in turn. Participants were asked about the impacts of turnaround times for forensic evidence and the value and meaning of evidence for the different outcomes included. There were also asked about their knowledge of forensic evidence and any training they had received about such evidence. This structure enabled the interviewer to ask follow-up questions and respond to investigative actions or hurdles raised by participants. Interviews lasted between 60 and 80 min. Although the interviews focused on volume crime investigation, participants were free to use cases relevant to any crime type to explain the practical application of legislation or internal policy or support their response.

Data analysis

Digitally recorded interviews were supplemented by the first author’s notes, which were made during interviews and after interviews in a research journal to record insights and challenges identified. The interviews and notes were transcribed verbatim and de-identified by removing information such as names or case file reference details. The review of interview notes constituted preliminary data analysis to identify and reflect upon key points that emerged from the interviews. Notes from the research journal were helpful in considering potential categories for analysis of interview transcripts.

Data were analysed thematically to understand participants’ experiences, meanings and realities and how they influence investigative practices (Braun and Clarke Citation2006, Walter Citation2013). Thematic analysis of interview transcripts involved a priori coding against identified categories such as fingerprints, DNA, interviews, searching and search warrant use. Further inductive codes emerged through the thematic analysis, and these were explored for overlapping relationships. The similar codes were grouped to form themes and sub-themes. Relevant quotes illustrating the themes were transferred into an Excel spreadsheet ensuring themes and connections were readily available for interpretation (Braun and Clarke Citation2006, Citation2022). The thematic analysis did not extend to evaluating differences between organisations. Quotes that best reflect participants’ comments are reported with participant numbers.

Findings

The results reveal nuances in investigative decision-making processes. First, they illustrate how participants’ decision-making was influenced by forensic evidence. Second, they highlight how prior training and experience influenced investigators’ use of forensic evidence in decision-making.

Investigators’ decision-making process

Participants described a process of assessing the range of information, to give the best explanation. When forensic identification evidence was available, they developed a view that the suspect identified could be involved in the crime. Throughout this process, investigators would reassess the information, reflecting an abductive reasoning process. As an investigation progressed, they applied the burden of proof:

It builds because you start with only needing a reasonable suspicion for a search warrant and find someone, arrest them, and bring them for interview. And even if you arrest, they can be unarrested. So, you start with [reasonable] suspicion and then you build to get beyond reasonable doubt. But you might not always get there. (Participant 19)

Stage 1 – Decisions about initial investigative actions

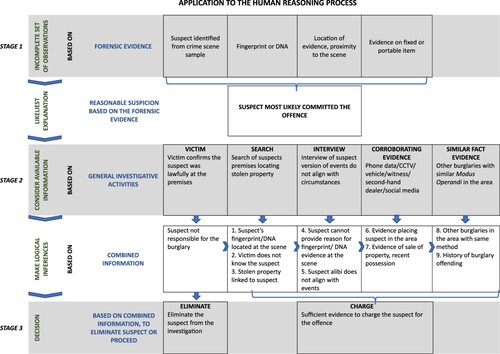

Figure 1. Decision-making process applying the human reasoning process in volume crime investigations.

In Stage 1, forensic evidence provides information in the form of an incomplete set of observations. It must be assessed to understand its value and weight within the context of the overall case. As one participant explained:

Everything is so fluid about investigations. You need to have an open mind. Biometrics is just one part of the investigative cycle. Fingerprint and DNA evidence in association with the turnaround time for the analysis, the location the evidence was collected, and the portability of the item can influence how the investigator decides to proceed on the basis of reasonable suspicion and in fact the weight of that suspicion. (Participant 20)

Fingerprint evidence. In the scenario provided, the fingerprint evidence consisted of fingerprints on the inside of the window screen, which had been removed from the kitchen window (point of entry) and fingerprints on the outside of the kitchen window. Participants perceived a high value of fingerprints due to their uniqueness and their relative inability to be placed there by anyone other than a person who was physically present:

Yes, my initial thoughts – it’s on the inside of the fly screen, then you would think that would be indicative of someone grabbing it and taking it off – if it was just someone coming up and touching it, that would be on the outside. It’s unlikely someone would touch the inside of the fly screen when it’s on a house. So, I think that adds to its weight as a good fingerprint. (Participant 7)

DNA evidence. The DNA evidence proposed in the scenario was in two forms: saliva and blood. The saliva was associated with a cigarette butt located outside the premises and some distance from the point of entry. The blood was a blood drop located on the kitchen floor. Most participants considered saliva to be valuable evidence but reported that saliva on a cigarette butt did not provide a direct link to the crime scene. They highlighted the limitations associated with saliva in the development of reasonable suspicion:

You have to consider the DNA [saliva] is taken from the place where they put it in their mouth, so it’s consistent with the fact that the person has significantly touched the cigarette. It still gives you a good position in regard to having a suspect. … if I just had the cigarette butt in the driveway, I don’t think it is compelling evidence that a person committed the burglary – it is compelling evidence that someone had the cigarette butt in their mouth. (Participant 23)

For a drop of blood on the kitchen floor, I would probably run the suspect’s name past the complainant to make sure there’s no lawful excuse. … But that’s really good evidence, really, really good evidence. I would charge someone on the basis of that alone. Such good evidence as it’s difficult to have blood without the person being present. I think it is very strong evidence. Very hard to have an innocent explanation. (Participant 4)

Location is pretty crucial. If it’s outside, they take back any admissions, state they just looked through the window. Prosecution won’t run with that; it can be difficult. Even with forensic [evidence] on the outside and recovered stolen property. Location is the most important thing for us. We always look for where the fingerprints and DNA have been located. (Participant 12)

Stage 2 – decisions about further investigative actions

In Stage 2, various investigative activities lead the investigator to reassess the suspicion of a specific person and then make logical inferences from all the information obtained. Potential suspects can be eliminated if identification evidence comes back as belonging to the victim or if the victim confirms that the person had a lawful reason for being at the premises (such as installing the fly screen):

Speak to the victim and ask them if they know who that person is. There could be a logical reason and that could be an unrelated [finger] print. (Participant 16)

Searching and interviewing are arguably two of the most important investigative activities influenced by forensic evidence. When assessing the weight of forensic evidence, participants had in mind the relevant legislation about searching. Fingerprint and DNA evidence assisted with development of reasonable suspicion, in the investigator’s mind, that the stolen property or evidence of the offence would be at the suspect’s premises when searched:

For burglary, the doctrine of recent possession, if offence happened at 9.00 am and you find the laptop at his house at 3.00 pm you have sufficient [information] to charge him as they have the laptop from the offence, same brand of cigarette and clear connection with DNA. (Participant 21)

DNA analysis takes an awful long time to come back by comparison to fingerprints. So, I couldn’t act as quickly on the suspect identification by DNA because I wouldn’t be able to get it back for a few months. So, I think that might change around the likelihood that the property is still in possession. So, I wouldn’t look at searching unless I had more evidence to suspect – I just wouldn’t have the grounds. (Participant 8)

At interview … Give them the allegation in a general sense and give them particular times and dates. Ask them what they know about it, get their version of events. Challenge them at the end, knock out their credibility. Introduce the forensics at the end with the challenge. They usually get really angry and deny it or make an admission. (Participant 15)

… it’s strands in a cable as opposed to links in a chain. A successful circumstantial case is like strands in a cable because even if one strand breaks, if you have enough of them together that is a strong case, whereas if your case is links in a chain and you lose one link, the whole case falls apart. With enough corroboration you can make weak evidence strong. (Participant 21)

The weight of one strand of cord might be insufficient to sustain the weight, but three stranded together may be of quite sufficient strength. This it may be in circumstantial evidence – there may be combination of circumstances, no one of which would raise a reasonable conviction, or more than a mere suspicion; but the whole taken together may create a conclusion of guilt with as much certainty as human affairs can require or admit of (Baker Citation2010, p. 35).

in its strict sense refers to evidence which reveals that on another occasion, the accused acted in a particular way in a particular situation, which is tendered to prove that the accused acted in similar way on the occasion in question (Harris Citation1995, p. 99).

Similar acts are where the point of entry is the same, same time of day, similar offences within a 4-hour period in the same suburb. Having a known [finger] print with other circumstantial evidence as a collective investigation. You have one offence to support the charging of another offence. You just build a case around that. (Participant 23)

Stage 3 – final decisions

In Stage 3, the investigator makes the final decision about the outcome of the investigation from the information collated. The investigator decides whether sufficient information exists to offer proof that a particular suspect committed the crime, or alternatively, that sufficient evidence exists to eliminate the suspect from the investigation. As noted above, a suspect can be eliminated from the investigation through the victim’s confirmation that the suspect was lawfully on the premises, or alternatively, through support for the suspect’s account of their movements via the investigative process.

The investigation builds as more evidence becomes available, or the weight of the evidence supports the charges. It can move from reasonable suspicion to a position to having sufficient proof of the elements of the offence to charge the suspect. Because of the nature of volume crime investigations, moving through this process might not result in collating more evidence. Importantly, there may be no evidence to negate the original view that the suspect committed the offence, and the only evidence may be the forensic evidence that triggered the investigation into this suspect. Alternatively, there may be insufficient evidence to suggest that the suspect committed the crime, or the evidence may suggest that the suspect did not commit the crime, circumstances that mean the suspect is not charged. By working through the reasoning process and making decisions on investigative actions, the investigating officer tests the original hypotheses.

Participants responses highlighted the complexities involved in making this final decision. There was a need to balance the desire to provide an outcome for the victim and meet the requirements associated with burden of proof – which was not clear cut:

Yes, so there is legal, the way the court views and deals with cases is completely different to how I view and deal with cases. I can look at my case and go you know ‘dead to rights’ [slang for positive proof of guilt] and hand it to a prosecutor and he can tear the case apart being the devil’s advocate to work out where the weak points are and go ‘this, this, this, this, this’. And some of the stuff I might think is necessary, but they don’t, but I guess that is the quality control we need before we can put it to court. I can put something forward and think it is perfect, but they go to court and defence can pick it apart in front of the magistrate or jury and they will go ‘no, you haven’t done enough’. (Participant 13)

| 2. | Factors that influence investigative decision-making process | ||||

This study identified that the factors that can influence the decision-making process largely relate to knowledge and experience in both forensic evidence and investigative skills.

Knowledge of forensic evidence

There was considerable variation among the extent of investigators’ knowledge of fingerprint and DNA evidence and how it was collected and analysed. They had reportedly received differing levels of training, with many noting that they had never received forensic training or could not remember the last time they had received it. Those who remembered forensic training discussed recruit training and detective training, which had focused on crime scene management, rather than on the strengths and limitations of different forensic evidence and how it can be used to enhance the effectiveness of an investigation. One participant articulated the value of further forensic training and potential gaps in the investigative process:

I definitely support investigating officers having a broader knowledge of what forensics can achieve. I think because we don’t have a thorough understanding of forensic policing there are lots of missed opportunities. As investigators we have an overview of everything – but as a result, we lose certain skill sets in the forensic side of things. But an increased awareness is important otherwise we are missing evidence left, right and centre. (Participant 17)

The investigating officer has responsibility to make the decision of whether to charge. As I am junior, I consult with a senior officer. Whilst the investigating officer makes all the final decisions, being a junior investigating officer, I am supervised in the decision-making process. If I think insufficient evidence, it’s my decision not to charge. (Participant 24)

It’s not called decision-making – it’s just the investigative process. Because that’s decision-making as well, there are a whole heap of decisions to make. Being good at investigations and a good decision-maker is crucial for a good investigator. (Participant 5)

Of course, for the uniformed general duty officers, they won’t have access to the specialist units straight away but can do all the basic stuff to gain the evidence. But for me, it’s the CIB [Criminal Investigation Branch] course and the promotional course I’ve done for my decision-making and basically what you learn on the job and doing it for 30 years. (Participant 6)

Experience

The importance and value of experience was a strong theme in the interviews and referred to as ‘extremely important’ by most investigators. The value of experience had several facets; one’s own experience, the combined experience of the others on the team and the importance of building one’s skill set while working towards detective qualification. One’s own experience and the ability to develop an individual method could provide effective results yet be undertaken in different ways:

Experience is crucial. I have seen investigators that are just good at what they do, they always get results whether it’s a rapport with the crook [slang for offender] that they can get the crooks to talk. And it’s a tangible thing I think sometimes with what makes a good detective. Couple of the old school guys that I work with, just the way they run an investigation would be different but with the same outcome. (Participant 5)

Discussion

This study aimed to contribute to understanding how police investigators engage in decision-making about forensic evidence in volume crime investigations. Using a scenario-based interview, participants provided insights into their decision-making processes. The analysis resulted in the development of a figure that documents the decision-making process and is compatible with an abductive reasoning process. This outcome supports findings in previous research by Fahsing (Citation2016) Baechler et al. (Citation2020) and Barrett (Citation2009).

Additionally, the findings highlight the importance of the notion of reasonable suspicion. They demonstrate how forensic evidence can contribute to reasonable suspicion and thereby provide avenues for investigators to meet their responsibility to obtain proof of the elements of the crime before charges can be laid. In so doing, the use of forensic evidence contributes to investigators’ roles and the broader criminal justice process. The findings reinforce the importance to investigators of the turnaround time of forensic analysis in forming reasonable suspicion because long lead times delay investigative action, making it harder to build the case. The findings also highlight that forensic training appears to be siloed, with a focus on how to handle, package and transport physical evidence, rather than on its effective application in the investigative process. This finding reflects those of Aepli et al. (Citation2011), that operating in silos is detrimental to investigations. Crime is solved through teamwork and understanding the context in which all ‘players’ in the process must operate (Gehl and Plecas Citation2016).

Most scholarly accounts concur that investigative work is largely a matter of information management (Ask and Alison Citation2010), but investigators must gather, assess and make inferences from various information types and from diverse sources. A certain degree of subjectivity is involved in the process of interpreting investigative findings (Ask and Alison Citation2010, Westera et al. Citation2013). The findings of this study show that forensic evidence can be an important strand in an investigation that supports outcomes. The various strands relate to more than just forensic evidence – they relate to the entire framework that surrounds the investigative space. Nevertheless, considering the combination of forensic evidence type, location, portability and timeliness of analysis can maximise the investigator’s ability to utilise all investigative and legislative tools available.

The findings of this study highlight that the cognitive processing required for police investigators to make a meaningful interpretation of forensic evidence is influenced by their knowledge, training, and experiences. The findings of this study support arguments by Barrett (Citation2009) that through the application of an abductive reasoning process within these investigative practices, police investigators piece together an investigation with a meaningful interpretation of all available evidence. Several implications follow from the findings of the study.

Implications of the findings

Given the disparities in investigators’ knowledge and the siloed nature of training on forensic evidence, the findings support the need for the development of more suitable training on the use of forensic evidence in investigations. As previous research has concluded, failure in investigative sense- making can include failures to make appropriate inferences, recognise opportunities for action, and consider possible alternative explanations for investigative data (Barrett Citation2009). The overall effectiveness of using forensic evidence in an investigation relies on the ability to make sense of the forensic evidence and interpret the ‘case variables in play at the crime scene’ (Morgan Citation2017, p. 457). Specific training for investigators on understanding of the weight of forensic evidence as a combination of forensic evidence type, location, portability, and timeliness of analysis would be valuable.

While many participants in this study reportedly used forensic evidence for investigative leads as well as with court purposes in mind, the findings also suggest that much of this knowledge is gained through experience. Fleming and Rhodes (Citation2016) refer to experience as fundamental to a craft; this is particularly the case in policing. This craft is learned on the job with some of the most valuable knowledge, skills, and judgement acquired by daily experience, and in the form of practical beliefs and practices that are passed on from experienced to novice police officers (Bonner Citation2018). However, experience alone is insufficient for the development of sense-making expertise. Failures are likely to be reduced where police personnel have the knowledge, experience, and training to make appropriate inferences about forensic evidence. The findings of the present study support arguments by Fahsing (Citation2016) that providing police investigators better training and more experience in the use of forensic evidence and understanding of the human reasoning process, through targeted on-the-job training will assist investigators to develop an abductive thinking investigative mindset (Fahsing Citation2016). This process will support improved investigations through transformation of the investigator and translation into both practice and policy (Morgan Citation2017, Corsianos Citation2010, Bonner Citation2018, Artello and Albanese Citation2019).

Training to enhance decision-making processes for the effective use of forensic evidence would move this important skill from a basis of experience and intuition to one of research-based knowledge. This would facilitate the conversion of forensic case specific information into ‘legally meaningful evidence’ (Kruse Citation2012, p. 301) through sound decision-making logic and ‘reduc[e] the barriers to transparency and accountability in the investigative process’ (Tong and Bowling Citation2006, p. 325). We suggest that rather than waiting for police officers to develop their experience over the years of their career, we should ask: ‘How can police officers best be equipped to understand and use forensic evidence effectively from the outset?’ The current approach, which includes variable learning about the range of forensic disciplines and their applications, and gaining on the job experience, offers limited support for their purpose. We suggest that the incorporation of education about decision-making in general, and forensic decision-making specifically, would be beneficial for developing investigators to be well equipped to use forensic evidence effectively in the investigation of volume crime. Training for police officers in the effective use of forensic science in the criminal justice system will contribute to facilitating the use of ‘the most scientifically valid and reliable forensic evidence possible, and, thus, improve the efficacy of the outcomes it generates’ (Cooper Citation2016, p. 24).

Data quality and limitations

This study shed light on investigative decision-making using forensic evidence in the Australian context. The findings are likely to be relevant in Australian jurisdictions and those with similar legal systems, where investigators share similar roles and responsibilities and police powers. They may be less applicable in jurisdictions that differ substantially in approach. Further comparative research could contrast approaches in different systems. As the present study focused on the investigative process only further research that documents decision-making processes during prosecutorial phase would also be beneficial.

The study also provided insights into police investigators’ perceptions of their training on topics such as the legal system, decision-making and forensic science. Further research could explicitly examine training materials and include interviews with the trainers for a detailed understanding of the materials and level of expected knowledge and skills development. Drawing on the findings from the present study and from research on training materials, further work can be undertaken to design and implement investigative training courses that incorporate theory and practical skills in forensic decision-making. Collaborative course development with expertise from policing, law and academia could help investigators to develop nuanced understandings of how human reasoning processes can be contextualised for police investigators, recognising the influence of legal requirements and the value of forensic evidence, to enhance coherence through the investigative process.

Conclusion

In 1866, Sir Charles Edward Pollock instigated the use of two forensic metaphors or analogies: ‘links in a chain’ and ‘strands in a cable’ (Baker Citation2010). While intermediate facts constitute indispensable links in a chain of reasoning towards an inference of guilt, a combination of circumstances taken together, as multiple strands of a cord, may lead to a conclusion of guilt. Over time, these two analogies have continued to be applied as contrasting forensic metaphors (Baker Citation2010). As demonstrated in this study, the analogy ‘strands in a cable’ can be readily employed by investigators when assessing the weight and application of forensic evidence and aptly reflects the human reasoning during their decision making.

The findings of this study demonstrate that the meaning, value, and weight of forensic evidence changes throughout the course of an investigation. Forensic evidence, on its own, is an incomplete set of observations that must be placed into the context of other information about the circumstances surrounding the incident and the suspect. Investigators form likely explanations or hypotheses based on their interpretation of the evidence – including knowledge of its location and portability – to provide a reasonable suspicion of the involvement of a potential suspect. This process involves the application of abductive reasoning for thorough problem recognition, problem framing and option generation. The findings suggest a need for targeted training on human reasoning and practical experience in deciding the value of different types of forensic evidence under different circumstances and at different investigative phases to support the effective use of forensic evidence in investigative decision-making in volume crime investigations.

List of cases

The State of South Australia v Nguyen., (2013). SASCFC 91. https://jade.io/article/302174.

Terry v Ohio (1968). 392 U.S. 1. https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/392/1/

Acknowledgements

We thank the police organisations that agreed to contribute to the research and the individual police investigators who shared their insights and experience.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aepli, P., Ribaux, O., and Summerfield, E., 2011. Decision making in policing. operations and management. Lausanne: CRC Press.

- Anderson, J.M., et al., 2018. The unrealised promise of forensic science – an empirical study of its production and use. X, California: RAND Justice Institute and Environment Justice Policy, 1–52.

- Artello, K., and Albanese, J.S., 2019. Investigative decision-making in public corruption cases: factors influencing case outcomes. Cogent social sciences, 7 (1), 1–15.

- Ask, K., and Alison, L., 2010. Investigators’ decision making. In: P. A. Granhag, ed. Forensic psychology in context: Nordic and international perspectives. Cullompton, UK: Willan, 35–55.

- Baechler, S., et al., 2020. Breaking the barriers between intelligence, investigation and evaluation: a continuous approach to define the contribution and scope of forensic science. Forensic science international, 309, 1–10. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2020.110213

- Baker, I., 2010. Circumstantial evidence in criminal cases. Bar news: The journal of the New South Wales Bar association, 42, 32–39.

- Barrett, E.C., 2009. The interpretation and exploitation of information in criminal investigations. PhD thesis. University of Birmingham, 1-382.

- Bitzer, S., et al., 2016. To analyse a trace or not? evaluating the decision-making process in the criminal investigation. Forensic science international, 262, 1–10. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2016.02.022

- Bonner, H.S., 2018. The decision process: police officers’ search for information in dispute encounters. Policing and society, An international journal of research and policy, 28 (1), 90–113.

- Bradbury, S., and Fiest, A., 2005. The use of forensic science in volume crime investigations: a review of the research literature. London: Home Office.

- Brandl, S.G., and Frank, J., 1994. The relationship between evidence, detective effort and the disposition of burglary and robbery investigations. American journal of police, 13, 149–167.

- Braun, V., and Clarke, V., 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative research in psychology, 3, 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Braun, V., and Clarke, V., 2022. Thematic analysis, a practical guide. London: SAGE Publishing.

- Brookman, F., et al., 2022. Crafting credible homicide narratives: forensic technoscience in contemporary criminal investigations. Deviant behaviour, 43 (3), 340–366. doi:10.1080/01639625.2020.1837692

- Brookman, F., and Innes, M., 2013. The problem of success: what is ‘good’ homicide investigation? Policing and society, 23 (3), 292–310. doi:10.1080/10439463.2013.771538

- Brown, C., et al., 2016. A step towards improving workflow practices for volume crime investigations: outcomes of a 90-day trial in South Australia. Police practice and research, 13, 1–13.

- Brown, C., 2021. The effectiveness of forensic identification evidence in volume crime policing in Australia. PhD thesis. University of Tasmania, 1–441.

- Brown, C., Ross, A., and Attewell, R.G., 2014. Benchmarking forensic performance in Australia – volume crime. Forensic science policy & management: An international journal, 5 (3–4), 91–98. doi:10.1080/19409044.2014.981347

- Bruenisholz, E., et al., 2019. Benchmarking forensic volume crime performance in Australian. Forensic science international: synergy, 1, 86–94. doi:10.1016/j.fsisyn.2019.05.001

- Burrows, J., et al., 2005. Understanding the attrition process in volume crime investigations. London: Home Office Research, Development and Statistics Directorate. (Home Office Research Study 295), 1-176.

- Cooper, S.L., 2016. Forensic science identification evidence: tensions between law and science. The journal of philosophy, science & Law, 16, 1–35. doi:10.5840/jpsl20161622

- Corsianos, M., 2010. Discretion in detectives’ decision making and ‘high profile’ cases. Police practice and research, 4 (3), 301–314. doi:10.1080/1561426032000113893

- Crispino, F., 2008. Nature and place of crime scene management within forensic sciences. Science and justice, 48, 24–28. doi:10.1016/j.scijus.2007.09.009

- Eck, J., 1983. Solving crimes: The investigation of burglary and robbery. Washington : Police Executive Research Forum, U.S, National Institute of Justice.

- Fahsing, I.A., 2016. The making of an expert detective. thinking and deciding in criminal investigations. PhD thesis. University of Gothernburg, 1–119

- Fahsing, I., and Ask, K., 2015. The making of an expert detective: the role of experience in English and Norwegian police officers’ investigative decision-making. Psychology, crime and Law, 22, 203–223. doi:10.1080/1068316X.2015.1077249

- Fleming, J., and Rhodes, R.A.W. 2016. Can experience be evidence? In: Public policy and administration specialist group, panel 2: policy design and learning, PSA 66th annual international conference, March 2016 Birmingham, 1–47.

- Gehl, R., and Plecas, D., 2016. Introduction to criminal investigation: processes, practices and thinking. New Westminster BC: Justice Institute of British Columbia. https://pressbooks.bccampus.ca/criminalinvestigation/.

- Greenwood, P.W., Chaiken, J.M., and Petersilia, J., 1977. The criminal investigation process: A summary report. Policing analysis, 3 (2), 187–217.

- Harris, W., 1995. Propensity evidence, similar facts and the high court. Queensland university of technology Law and justice journal, 11, 97–119.

- Heit, E., 2000. Properties of inductive reasoning. Psychonomic bulletin & review, 7 (4), 569–592. doi:10.3758/BF03212996

- Home Office. 2007. Scientific work improvement model – summative report. London: Home Office.

- Jang, M., et al., 2020. The impact of evidence type on police investigators’ perceptions of suspect culpability and evidence reliability. Zeitschrift für psychologie, 228 (3), 188–198. doi:10.1027/2151-2604/a000411

- Julian, R., Howes, L., and White, R., 2022. Critical forensic studies. London: Routledge.

- Keddie, A., 2023. Towards gender equality reform in police organisations: the utility of a social justice approach. Police practice and research, 24, 1–16.

- Kelty, S., Julian, R., and Hayes, R., 2015. The impact of forensic evidence on criminal justice: evidence from case processing studies. In: K.J. Strom, and M. J. Hickman, eds. Forensic science and the administration of justice: critical issues and directions. Thousand Oaks: Sage, 101–120.

- Kruse, C., 2012. Legal storytelling in pre-trial investigations: arguing for a wider perspective on forensic evidence. New genetics and society, 31 (3), 299–309. doi:10.1080/14636778.2012.687084

- Ludwig, A., Edgar, T., and Maguire, C.N., 2014. A model for managing crime scene examiners. Forensic science policy and management: An international journal, 5 (3–4), 76–90. doi:10.1080/19409044.2014.978416

- Ludwig, A., Fraser, J., and Williams, R., 2012. Crime scene examiners and volume crime investigations: an empirical study of perception and practice. Forensic science policy & management: An international journal, 3, 53–61. doi:10.1080/19409044.2012.728680

- Maegherman, E., et al., 2020. Test of the analysis of competing hypotheses in legal decision-making. Applied cognitive psychology, 35, 62–70. doi:10.1002/acp.3738

- Morgan, R.M., 2017. Conceptualising forensic science and forensic reconstruction. Part I: A conceptual model. Science and justice, 57 (6), 455–459. doi:10.1016/j.scijus.2017.06.002

- Moston, S., and Engelberg, T., 2011. The effects of evidence on the outcome of interviews with criminal suspects. Police practice and research, 12 (6), 518–526. doi:10.1080/15614263.2011.563963

- Prenzler, T., 2020. Remarks by the guest editor. Police, practice and research, 21 (5), 439–441. doi:10.1080/15614263.2020.1809826

- Ribaux, O., Roux, C., and Crispino, F., 2016. Expressing the value of forensic science in policing. Australian journal of forensic sciences, 49 (5), 489–501. doi:10.1080/00450618.2016.1229816

- Roman, J., et al., 2008. The DNA field experiment: cost-effectiveness analysis of the use of DNA in the investigation of high-volume crimes. Washington, DC: Urban Institute Justice Policy Centre.

- Sheppard, S., 2002. The metamorphoses of reasonable doubt: how changes in the burden of proof have weakened the presumption of innocence. Notre dame Law school review, 1165, 1–78.

- Smith, N., and Flanagan, C., 2000. The effective detective: identifying the skills of an effective SIO. London: Home Office Policing and Reducing Crime Unit.

- Spence, L., Cushway, D., and White, S., 2003. Forensic science targeting volume crime recidivists. Forensic bulletin, 26–28.

- Tong, S., and Bowling, B., 2006. Art, craft and science of detective work. The police journal, 79, 323–329. doi:10.1350/pojo.2006.79.4.323

- Walter, M., 2013. Social research methods: an Australian perspective. Hobart: Oxford University Press.

- Westera, N.J., et al., 2013. Defining the “effective detective”. Nathan: ARC Centre of Excellence in Policing and Security (Briefing paper).

- Wullenweber, S., and Giles, S., 2021. The effectiveness of forensic evidence in the investigation of volume crime scenes. Science and justice, 61 (5), 542–554. doi:10.1016/j.scijus.2021.06.008