ABSTRACT

In response to incidents of police brutality perpetrated against ethnic/racial minorities, there have been calls worldwide for reform in the way policing is done in minority communities. As part of this reform process, police agencies have been encouraged to examine the policing styles (or orientations) that different officers adopt when carrying out their duties. Prior research finds that ‘warrior’ and ‘guardian’ policing orientations are associated with officers’ support for either coercive or procedural justice policing, respectively. Warrior-oriented officers tend to support using coercive policing more than guardian-oriented officers, while guardian-oriented officers tend to support using procedural justice policing more than warrior-oriented officers. What remains understudied is why this is so. Drawing on survey data of 306 Australian police officers working in ethnically diverse and disadvantaged communities, this study tests whether officers’ cynicism toward the public and their confidence in their own legitimacy (i.e. self-legitimacy) might explain the tendency of warrior-oriented and guardian-oriented officers to support either coercive or procedural justice policing, respectively. Our findings confirm that the two policing orientations are conceptually distinct, and that warrior-oriented officers are more likely to support coercive policing, while guardian-oriented officers are more likely to support procedural justice policing. Importantly, we find that officers’ cynicism and self-legitimacy partially mediate some of these relationships. The implications of these findings for both policing scholarship and practice are discussed.

Introduction

The use of unnecessary or excessive force by police, particularly towards ethnic and racial minority groups, has generated widespread public concern in many parts of the world. Research from the US suggests that African American men are over-represented among police-involved deaths of unarmed individuals (Ross Citation2015), and there is evidence that police bias and brutality toward racial minorities also exists in the U.K., Canada and Australia among other countries (e.g. Bayley Citation1996, Carmichael and Kent Citation2014, Joseph-Salisbury et al. Citation2021, Murphy et al. Citation2018). In Australia, for example, there have been persistent concerns about overly coercive policing of ethnic and racial minority groups (e.g. First Nations Australians, and people from Muslim, African, and Asian backgrounds). Minority communities claim that Australian police are more likely to scrutinise their communities, unfairly detain them, and use excessive force during interactions (e.g. Ali et al. Citation2022, Weber et al. Citation2021).

This has led to calls for police agencies and practitioners to reform the way policing is done in minority communities (Porter and Cunneen Citation2021, President’s Task Force Citation2015, Stoughton Citation2016, Brown and Hobbs Citation2023). There have been specific calls to ‘assess the policing style officers adopt when carrying out their duties’ as part of the police reform process (see Clifton et al. Citation2021, p. 436). In the US, for example, the Police Executive Research Forum (Citation2015) suggested that a ‘warrior’ orientation to policing can damage police-minority relations because warrior-oriented officers favour more legalistic and aggressive policing (Balko Citation2013). Further, the President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing (Citation2015) recommended that police agencies develop policies that encourage officers to adopt a ‘guardian’ or ‘service’ orientation to policing which places more emphasis on procedural justice and community policing (see also Rahr and Rice Citation2015, Brown and Hobbs Citation2023). Procedural justice policing gives citizens voice in decision-making and emphasises respectful, trustworthy, and neutral treatment of citizens (Tyler Citation2006), while community policing focuses on developing relationships and partnerships with community members. This can involve ‘joint activities to co-produce services and achieve desired outcomes, giving the community a greater say in what the police do, or simply engaging each other to produce a greater sense of police-community compatibility’ (Mastrofski Citation2006, p. 46).Footnote1 The President’s Task Force (Citation2015) suggested a guardian-oriented policing approach will have greater success in re-building police legitimacy in minority communities.

Empirical research has confirmed that police officers can and do adopt warrior and guardian orientations (e.g. McLean et al. Citation2020, McCarthy et al. Citation2024). Studies also show that the warrior and guardian orientations are associated with officers’ support for coercive policing or procedural justice policing, respectively (see McLean et al. Citation2020, McCarthy et al. Citation2024). However, Clifton et al. (Citation2021) and McLean (Citation2019) argue that these two policing orientations and their consequences remain understudied and under-theorised. What is less well understood is why warrior-oriented officers are more likely to support coercive policing, while guardian-oriented officers are more likely to support procedural justice policing.

Our study goes beyond simply examining the relationship between warrior and guardian policing orientations and support for coercive and procedurally just policing. It draws on police occupational culture and police legitimacy literatures to explore two theoretical mechanisms that might help us to understand better why warrior-oriented and guardian-oriented officers support coercive or procedurally just-policing, respectively. Specifically, we examine whether police officers’ cynicism toward the public and their confidence in their own legitimacy (i.e. self-legitimacy) both mediate the relationship between warrior/guardian policing orientations and support for coercive/procedural justice policing. But first, we canvass what we know about the warrior and guardian policing orientations.

Warrior and guardian policing orientations and their consequences: what we know

Research shows that police officers can adopt different role orientations/identities/mindsets toward their work (e.g. Engel Citation2001, McLean et al. Citation2020, Muir Citation1977, Paoline et al. Citation2021, Rahr and Rice Citation2015, Silver et al. Citation2017). One commonly discussed distinction made in the literature is between ‘warrior’ and ‘guardian’ oriented officers, which characterise an officer’s mindset toward their policing work. They build on previous conceptualisations of ‘legalistic’ and ‘service’ policing styles (e.g. Wilson Citation1968, Wortley Citation2003, see also Muir Citation1977), but have evolved in contemporary times to typify two key types of modern police officer.

Officers who identify as ‘warriors’ tend to embrace a strong crime fighting orientation to their role. They believe taking charge and maintaining the upper hand over citizens is important as officers see themselves as the ‘thin blue line’ that keeps society from descending into violent chaos. They perceive order maintenance and service work as not real police work (Kelling and Kliesmet Citation1996), and thus view the ideal police officer as one who prioritises control in citizen encounters and an aggressive approach to law and order (Balko Citation2013, Stoughton Citation2016).

Officers who adopt a guardian mindset, in contrast, tend to embrace a strong service orientation in their work. They believe less emphasis should be given to coercive tactics or controlling citizens. Stoughton (Citation2015, Citation2016) argued that guardian-oriented officers are typically motivated to encourage public engagement and public trust in police. They prioritise communication, are inclusive and respectful in interactions, display empathy, and exercise patience in citizen encounters. The guardian mindset emphasises the building of relationships and lasting partnerships between the police and the community through positive and procedurally just contacts (Murphy and McCarthy Citation2023, Stoughton Citation2015).

Scholars claim that systemic police bias occurs when too many officers adopt a warrior mindset, leading to overly suspicious, hypervigilant, and aggressive policing, particularly in high crime, disadvantaged and minority communities (e.g. Carlson Citation2020, McLean et al. Citation2020, Stoughton Citation2016). They suggest that prejudicial policing and resulting police brutality – particularly toward minority communities – might be mitigated if more officers embrace a guardian mindset.

Studies have measured these two policing orientations and their antecedents and consequences. They demonstrate that warrior and guardian orientations are measurable and conceptually distinct, that police officers do adopt these different policing orientations, but that they can sometimes identify with both orientations simultaneously (see McClean et al. Citation2020, McCarthy et al. Citation2024, Schuck Citation2024). For example, in the US McLean et al. (Citation2020) confirmed that the warrior and guardian orientations were conceptually distinct but positively correlated (r = 0.44), and McCarthy et al. (Citation2024) replicated these findings in Australia.

Studies have also explored the antecedents of these two policing orientations. Paoline and Gau (Citation2018), for example, found that officers who reported being more stressed by the strains of their job were more likely to adopt a warrior mindset and ‘crime-fighter’ approach to policing. In another study, Clifton et al. (Citation2021) found that those who felt more motivated by their job and who worked in departments that supported community policing were more likely to adopt a guardian mindset. Furthermore, Clifton et al. (Citation2021) found that officers who were more cynical of the public were less likely to identify with the guardian mindset (c.f., Schuck Citation2024), although McCarthy et al. (Citation2024) failed to find this relationship in Australian officers. Finally, female officers appeared less likely than male officers to identify with a warrior mindset and were more likely to identify with a guardian mindset (Clifton et al. Citation2021), although evidence for this is mixed (see McCarthy et al. Citation2024, Murphy and McCarthy Citation2023).

McLean et al. (Citation2020) argue that by better understanding the antecedents and consequences of guardian and warrior mindsets, police agencies can determine which officers might be more prone to adopt coercive policing. McLean et al. (Citation2020, p. 1100) state:

guardian orientations are superior to warrior mindsets because the former is more likely to produce attitudes, behaviors, and interactions primed for cultivating public trust and support. The latter, however, is more likely to be viewed by citizens as overly aggressive and unsympathetic to their needs.

Each of the studies cited above improve our understanding of warrior and guardian orientations and highlight how each might be linked with officers’ support for either coercive or procedurally just policing. Carlson’s (Citation2020) study even suggested that the policing orientations might be used differently in different communities. However, existing studies have not yet empirically examined the reasons why warrior-oriented officers might be more supportive of coercive policing, while guardian-oriented officers might be more supportive of procedural justice. Existing studies have tested if these policing orientations exist, have explored factors that may precede the development of each orientation, or have directly linked each orientation to either support for coercive or procedural justice policing. But the psychological mechanisms linking different policing orientations to officers’ support for either coercive or procedurally just policing have so far remained unexplored. Our study addresses this knowledge gap.

Explaining why warrior and guardian orientations might predict support for coercive or procedural justice policing

We draw on the occupational police culture and police legitimacy literatures to provide a starting point for better understanding the potential psychological mechanisms that may explain why warrior-oriented and guardian-oriented officers support (or not) coercive or procedural justice policing, respectively. We posit that officers’ cynicism toward the public and their confidence in their own authority (i.e. self-legitimacy) both mediate the associations between warrior/guardian-orientations and support for coercive/procedurally just policing.

The occupational police culture literature describes a set of attitudes, values, and norms that typify the traditional police culture (Paoline and Gau Citation2018, Waddington Citation1999). These attitudes, values and norms have been widely shown to explain why officers think and act the way they do (Ingram et al. Citation2018). Occupational police culture has been criticised for inculcating an ‘us versus them’ view of the public (Boivin et al. Citation2020), emphasising the ever-present danger police face, and encouraging suspicion and distrust of the public (Stoughton Citation2016, Loftus Citation2010). The ‘us versus them’ perspective can distance officers from the community (Boivin et al. Citation2020) and lead them to hold cynical attitudes about the public, who they have been taught to perceive as untrustworthy and dangerous (Brewer Citation1999, Loftus Citation2010). Studies consistently show that occupational police culture attitudes are strongly associated with heightened support for coercive force and reduced support for procedurally just practice (e.g. Paoline and Gau Citation2018, Silver et al. Citation2017, Terrill et al. Citation2003).

It has been argued that traditional police culture has fostered warrior-oriented policing approaches (Balko Citation2013, McLean et al., Citation2020, Stoughton, Citation2016). Stoughton (Citation2015, p. 227) theorised that the ‘warrior’ mindset depicts officers as being involved in ‘intermittent and unpredictable combat with unknown but highly lethal enemies’. He notes that because officers see the public as potential enemy combatants, the warrior mindset promotes officer hypervigilance and suspicion of the public, which further perpetuates the ‘us versus them’ perspective. McCarthy et al. (Citation2024) further argued that warrior-oriented policing promotes officers’ social distance from the public, leading to reliance on stereotypes, reduced empathy, and increased cynical attitudes towards the socially-distanced ‘other’ (e.g. citizens). This can disinhibit officers’ restraint in using aggression (McCarthy et al. Citation2021). As guardian-oriented officers typically see policing work more as a service to the community, such public cynicism is likely to be lower and a preference for procedural justice policing higher (McCarthy et al. Citation2024). Together this theorising implies that the psychological orientation of officers towards the public – that is, the extent to which officers are cynical or distrustful of the public – might provide a starting point for better understanding why warrior-oriented officers tend to support coercive policing. It might also provide better understanding of guardian-oriented officers and why they tend to support procedural justice policing. In other words, cynicism might mediate the relationship between warrior/guardian orientations and support for coercive/procedural justice policing.

The police legitimacy literature also provides insight into why warrior-oriented officers might be more supportive of coercive policing while guardian-oriented officers might be more supportive of procedural justice. In short, research emphasises the importance of police officers’ perceived self-legitimacy in shaping their own behaviour (e.g. Bottoms and Tankebe Citation2012, Debbaut and De Kimpe Citation2023). Bottoms and Tankebe (Citation2012) suggest that officers develop confidence in their entitlement to power (i.e. self-legitimacy) through daily interactions with citizens. When issuing directives to citizens, officers make a claim to legitimate power. They propose if an officer’s directive does not align with a citizen’s expectations of how the officer should have behaved this might lead to the officer’s directive being perceived as illegitimate by the citizen, resulting in defiance. This might challenge or threaten an officer’s confidence in their own legitimacy, which may result in the officer either responding with coercion/force or responding by negotiating with the citizen for a more amicable resolution (see also White et al. Citation2021).

Murphy and McCarthy (Citation2023) suggest that guardian-oriented officers are better able to overcome perceived threats to their legitimacy because they have more confidence in their self-legitimacy. Bradford and Quinton (Citation2014) note that officers who possess greater confidence in their self-legitimacy tend to be ‘calmer and more assured; more able to engage in difficult decisions in constructive ways; more willing to allow members of the public a say during processes of interaction and crucially, inclined only to use force as a last resort’ (p. 1027). These qualities are endorsed by guardian-oriented officers. This follows that guardian-oriented officers hold greater confidence in their self-legitimacy. Bradford and Quinton (Citation2014, p. 1028) further argue that officers who have less confidence in their self-legitimacy may be less willing to support using procedural justice because a citizen ‘might throw up difficult questions or challenges to their authority’. In order to protect themselves from these legitimacy challenges/threats, therefore, an officer who is less confident in their self-legitimacy will rely more heavily on threats or force to coerce cooperation. This display of coercive authority reasserts to officers that they have control, thereby bolstering their feelings of self-legitimacy. Indeed, empirical studies indicate that when officers are less confident in their self-legitimacy they rely more heavily on coercive tactics (Tankebe and Mesko Citation2014, Trinkner et al. Citation2019). Officers who have greater self-legitimacy, in contrast, express greater support for procedural justice (Bradford and Quinton Citation2014 White et al. Citation2021), and display more willingness to engage proactively with communities (Wolfe and Nix Citation2016).

However, Debbaut and De Kimpe (Citation2023) argue that self-legitimacy is also linked to occupational police culture and may thus be associated with heightened support for aggression. They suggest that distinct aspects of the police occupation (e.g. self-image as a crime fighter, solidarity with fellow officers, and cynicism of the public, etc.) reinforce self-legitimacy and the belief in the moral righteousness of one’s actions. Debbaut and De Kimpe argue that belief in the moral rightness of one’s actions can exacerbate an ‘us versus them’ mindset and cynicism of the public, which is also characteristic of the warrior mindset. As such, Debbaut and De Kimpe (Citation2023, p. 696) argue that heightened self-legitimacy might in fact ‘contribute to some police officers feeling comfortable about violating norms such as the proportionate use of force … … as they perceive that they belong to “a unique group” that is on a mission for the “greater good”’. In other words, they posit that heightened self-legitimacy might exacerbate support for coercive policing, not reduce it. This will be tested in the current study. Importantly, when considered together, the above-cited literature positions both cynicism and self-legitimacy as potentially important mediators in the warrior/guardian orientation and support for coercive/procedural justice policing relationship.

Current study

Our study contributes to existing research on the warrior and guardian policing orientations and the role of each in influencing police officers’ support for coercive or procedurally just policing. It aims to extend current theorising by exploring two possible psychological mechanisms that might explain why warrior-oriented officers tend to support coercive policing while being less likely to support procedural justice. It also aims to examine why guardian-oriented officers tend to support procedural justice policing while being less likely to support coercive policing. Specifically, it tests whether both cynicism and self-legitimacy mediate these relationships.

Before proceeding it is worth noting that existing research on guardian and warrior orientations focuses on how these constructs relate to officers’ support for procedural justice or coercive policing, respectively. This includes our study. The assumption underlying this body of research is that officers’ supportive attitudes – as psychological and evaluative states – predispose them to act in a certain manner. Whether attitude translates to behaviour has been a source of debate (see Frank and Brandl Citation1991). Frank and Brandl argue that when an attitudinal measure is relevant to the target behaviour it would be reasonable ‘to anticipate that the attitude measure would predict the behavior under analysis’ (p. 85). As such, by investigating officers’ support for either procedural justice or coercive policing, our study provides possible insight into how officers might subsequently behave on the job.

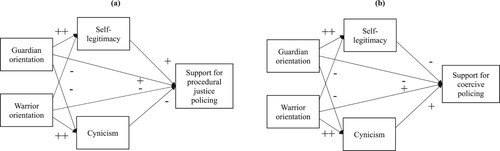

Drawing on survey data collected from Australian police officers, we first test whether the guardian and warrior orientations are conceptually distinct. Given prior research suggests they are (e.g. McLean et al. Citation2020, McCarthy et al. Citation2024), we expect they will be (Hypothesis 1). We then test if the warrior orientation is negatively associated with support for procedural justice (Hypothesis 2) while being positively associated with support for coercive policing (Hypothesis 3) as has been found in prior studies (e.g. McLean et al. Citation2020, McCarthy et al. Citation2024, Schuck Citation2024). We also test if the guardian orientation is positively associated with support for procedural justice (Hypothesis 4, see Murphy and McCarthy Citation2023) but negatively associated with support for coercive policing as suggested in prior research (Hypothesis 5, see McLean et al. Citation2020). Most importantly, we explore whether cynicism and self-legitimacy mediate the relationships between warrior/guardian orientations and coercive/procedural justice policing, respectively (Hypothesis 6). presents our conceptual models and the anticipated relationships between key measures.

Methods

Participants and procedure

We draw on survey data collected in 2017 from 307 Australian police officers serving in the Queensland Police Service (QPS). Queensland is the third most populous state of Australia (approximately five million residents). QPS is a state-based policing agency so provides policing services across the entire state. At the time of data collection, 11,969 sworn officers worked for the QPS across 336 Divisions. Frontline officers working in 52 QPS Divisions were sent an email inviting them to participate in a 30-minute online Qualtrics survey about their job.Footnote2 These Divisions were selected because they either had high levels of violent crime or high levels of socio-economic disadvantage, or both. These Divisions were selected because prior research shows that high levels of crime and socio-economic disadvantage influences how officers enforce the law in those areas (e.g. Terrill and Reisig Citation2003).

Neighbourhoods in the selected Divisions had an average of 50.98% (SD = 25.72%) of residents living in the bottom 40% most disadvantaged areas in Queensland. They also had higher than average levels of racial minority and non-English speaking residents (i.e. Division’s First Nations residents: M = 6.49%, SD = 12.20% vs population weighted M = 3.70% for all QPS Divisions; Division’s residents born in Non-English speaking countries: M = 12.84%, SD = 9.93% vs population weighted M = 10.50% for all QPS Divisions). Some of the Divisions were located in predominantly First Nations communities, with one Division having 93.6% of the population identifying as First Nations people. Rates for violent crime (homicide, manslaughter, assault, robbery) in the selected Divisions ranged from 7.36 per 10,000 persons to 1,766.04 per 10,000 persons (Queensland population M = 157.64 per 10,000 persons; SD = 186.60).

Ethics approval was provided by Griffith University’s Human Research Ethics Committee (Protocol: 2016/680) and the project was also approved by the QPS Research Committee. A recruitment email from the project team was sent from a QPS Inspector’s email, and was endorsed by the local Division commander. This strategy aimed to increase response rates by communicating to participants the value of the project to QPS. Given the voluntary and anonymous nature of the survey, this strategy was not seen as coercive by either the Ethics or Research Committees. Five reminder emails over four weeks were sent to boost response. A total of 477 officers commenced the survey, but only 307 officers completed the survey; data from these 307 officers were utilised. Approximately 1,884 officers worked in the 52 Divisions, so the response rate was estimated at 15%. Whilst somewhat low, Nix et al. (Citation2017) note that online policing surveys tend to yield low response rates but still produce accurate self-report data and do not necessarily produce non-response bias.

presents the profile of participating officers and compares them to publicly available QPS employee information. The sample is broadly representative of QPS population characteristics. Most participants were general duties officers (69.4%), and 11.1% of participants had served less than one year in their Division. Most participants were male (77.2%), reported being from Australian ancestry (88.9%), and the average age was 36–45 years. One participant identified their gender as non-binary; this individual was excluded from the final analysis as no meaningful analysis could have been done with them, leaving a total of 306 participants.

Table 1. Profile of sample (N = 307).

Measures

Survey items are presented below or in . All multi-item scales were subjected to a single principal components analysis with varimax rotation (see ). The Keiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) statistic was satisfactory at .84, and items loaded as expected onto their respective component with no cross-loading; mean-computed scales were subsequently created. Importantly, the factor analysis revealed that the guardian and warrior-orientation concepts were conceptually distinct (supporting Hypothesis 1). However, unlike in prior research (McLean et al. Citation2020, McCarthy et al. Citation2024) they were negatively correlated (r = −.28; see ).

Table 2. Principal Components Analysis with Varimax rotation.

Table 3. Bivariate correlations.

Dependent variables

The support for procedural justice scale comprised 8-items, drawn from Trinkner et al. (Citation2019). It measured officers’ level of support for procedural justice when interacting with community members in their Division. Items reflected the four key elements of procedural justice (that officers should treat citizens with respect and neutrality, convey trustworthy motives, and give citizens voice; see ). Items were measured on a 1 = not at all important; 2 = slightly important; 3 = moderately important; 4 = very important; 5 = extremely important Likert scale, with higher scores indicating greater support for procedural justice (M = 3.81; SD = 0.61; Cronbach α = 0.90).

Support for coercive policing was a 4-item scale, based on work by Rosenbaum et al. (Citation2011). It assessed officers’ support for using coercive tactics and excessive physical force in citizen encounters. As such, it identifies officers who favour a coercive policing approach. Items were measured on a 1 = strongly disagree; 2 = disagree; 3 = neither disagree nor agree; 4 = agree; and 5 = strongly agree Likert scale. Higher scores suggest greater support for coercive policing (M = 2.63; SD = 0.73; Cronbach α = 0.70).

Independent variables

The guardian-orientation and warrior-orientation scales were drawn from Wortley’s (Citation2003) study of Australian policing styles. The guardian orientation scale comprised 3-items, and assessed the importance that officers placed on using communication, respectful treatment and discretion in interactions with people in their Division. The warrior orientation scale was measured with 5-items; it assessed the degree to which officers favoured a tough on crime approach in policing and whether they viewed service work as ‘not real police work’. Both scales were measured on a 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree scale; higher scores reflect greater identification with the guardian or warrior policing mindset, respectively (Guardian M = 3.57; SD = 0.77; Cronbach α = .73; Warrior M = 2.82; SD = 0.63; Cronbach α = .69). Note that data collection occurred prior to recently published studies on guardian vs warrior-oriented policing, and thus our measures differ somewhat from other scales that have been used more recently (e.g. McLean et al. Citation2020, McCarthy et al. Citation2024, but see Murphy and McCarthy Citation2023 for an exception).

Mediator variables

Cynicism toward the public was measured via 3-items from Rosenbaum et al. (Citation2011). It gauged officers’ views about residents living in their Division; specifically, the belief that residents were dishonest and should be viewed with suspicion. Items were measured on a 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree scale; higher scores indicate greater cynicism (M = 2.51; SD = 0.84; Cronbach α = .76). Self-legitimacy comprised 3-items adapted from Trinkner et al. (Citation2016). Items assessed whether officers perceived that they occupied a special role in society and reflected their level of confidence in the normative authority imbued within that role. Items were measured on a 1 = not at all; 2 = not much; 3 = not sure; 4 = somewhat; 5 = a great deal scale; higher scores reflect greater self-legitimacy (M = 4.11; SD = 0.70; Cronbach α = .62).

Control variables

Various demographic and attitudinal control variables were included as prior research shows these can influence officers’ attitudes and behaviours (Silver et al. Citation2017). For example, officers’ concerns about their safety and their perceptions of their supervisors’ approach have been found to correlate with support for coercive policing or procedural justice, respectively (e.g. Engel and Worden Citation2006, Silver et al. Citation2017). Demographic variables were: gender (0 = female; 1 = male), years of police service, time in current Division, current role (i.e. general duties = 0; other = 1), and cultural/ethnic identity. Cultural/ethnic identity was measured by asking what ethnicity or cultural groups officers most strongly associated with. Options were: Australian; Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander; North-East Asian; South-East Asian; New Zealand, Melanesian, Micronesian or Polynesian; British or Irish; Southern and Eastern European; North-West European; Sub-Saharan African; North African or Middle Eastern; South American, North American; other (please specify). The majority selected ‘Australian’ (88.9%), so the measure was dichotomised (Australian = 0; other = 1). Also controlled for was officers’ level of worry about their physical safety on the job (‘How often are you in situations where you worry about your physical safety?’; M = 3.30; SD = .89), and their perception of their supervisors’ work approach (‘How tough are supervisor(s) with you when trying to get you to do what they want?’; M = 2.44; SD = .99). Both items were measured on a 1 = never; 2 = rarely; 3 = sometimes; 4 = often; 5 = always scale; higher scores indicate more worry and perceiving supervisors’ approach as tougher.Footnote3

Results

shows all bi-variate relationships between measures were in the expected direction. The exception was the negative relationship between the warrior and guardian measures (r = −.28). This contrasts with prior research suggesting that the two constructs are positively related (see McLean et al. Citation2020, McCarthy et al. Citation2024).

To address Hypotheses 2–6, we conducted parallel mediation analyses using the PROCESS macro tool (specifying Model 4) in SPSS v28. summarises four regression models.Footnote4 Model 1 examines the relationship between the key independent variables (guardian and warrior orientations) and the first mediator variable (i.e. self-legitimacy). Model 1 shows that the guardian orientation was positively related to self-legitimacy, but this relationship was not significant (β = 0.09). The warrior policing orientation, however, was negatively and significantly related to self-legitimacy (β = −0.17), suggesting that warrior-oriented officers were less likely to have confidence in their self-legitimacy. None of the control variables were associated with self-legitimacy.

Table 4. Parallel mediation analysis: Predicting support for procedural justice and coercive policing.

In Model 2, the relationships between the guardian and warrior orientations and the second mediator variable (i.e. cynicism) were examined. Here, the warrior orientation was positively and significantly related to cynicism (β = 0.19), but again the guardian orientation was unrelated to cynicism (β = .06). This suggests that warrior-oriented officers were more likely to hold cynical views about residents in their Division, while guardian-oriented officers did not. Model 2 also shows that longer-serving officers held less cynical attitudes toward residents (β = -.18), while those who worried more about their safety on the job (β = .13) and who believed their supervisor treated officers toughly (β = .16) were more cynical of the public. No other variables were related to cynicism.

In Model 3, the two independent variables (guardian and warrior orientations) and the two mediator variables (self-legitimacy and cynicism) were entered as predictors of support for procedural justice policing. Of the control variables, gender, ethnic/cultural identity, years of service, and perceptions of supervisor’s toughness were related to procedural justice. Female officers, those officers who identified as non-Australian, those who had served longer, and those who perceived their supervisors as less tough were more supportive of procedural justice policing. Importantly, both the guardian and warrior orientations were significantly associated with support for procedural justice, but the nature of each relationship differed. Officers who identified more strongly as guardians were more likely to support procedural justice policing (β = 0.17), while those who identified more strongly as warriors were less likely to support procedural justice policing (β = −0.19). Model 3 also shows that officers who had greater confidence in their self-legitimacy were more likely to support procedural justice policing (β = 0.15), while officers who scored higher on cynicism were less likely to support procedural justice (β = −0.20). This suggests that participants who identified more strongly as guardians and who had greater confidence in their self-legitimacy were more likely to support procedural justice policing, while officers who identified more strongly as warriors and who were more cynical were less supportive of procedural justice policing.

In Model 4, the two independent variables (guardian and warrior orientations) and the two mediator variables (self-legitimacy and cynicism) were entered as predictors of support for coercive policing. Here, we find that the warrior orientation (β = 0.35) was significantly and positively associated with support for coercive policing; warrior-oriented officers were more likely to support coercive policing. Also, cynicism (β = 0.14) was significantly and positively associated with support for coercive policing, suggesting those who held more cynical views of residents in their Division were more supportive of coercive policing. Neither the guardian orientation nor the self-legitimacy measures or any control variables were significantly associated with support for coercive policing.

presents the total, direct, and indirect effects of the guardian and warrior policing orientations on support for procedural justice and coercive policing, respectively. Turning first to the support for procedural justice results, neither of the indirect effects of the guardian orientation on support for procedural justice policing through self-legitimacy (β = 0.01) or cynicism (β = −0.01) were significant. This suggests that neither self-legitimacy nor cynicism mediated the guardian orientation/support for procedural justice relationship. In contrast, the indirect effects for the warrior orientation on support for procedural justice through self-legitimacy (β = −0.03; 95% CI[−.057; – .004]) and cynicism (β = −0.04; 95% CI[−.079; – .010]) were both significant, suggesting that both self-legitimacy and cynicism partially mediated the association between the warrior orientation and support for procedural justice policing. In other words, officers who identified more strongly as warriors were perhaps less supportive of procedural justice policing because they had less confidence in their self-legitimacy and because they viewed the public with more cynicism.

Table 5. Parallel Mediation Analysis: Total, direct, and indirect effects of guardian and warrior orientations on support for procedural justice and coercive policing

Turning to the support for coercive policing results in , the indirect effect of the warrior orientation on support for coercive policing through cynicism was significant and positive (β = 0.03; 95% CI[.003; .065]), but the indirect effect of the warrior orientation on support for coercive policing through self-legitimacy was insignificant (β = 0.01). These findings suggest that cynicism played a partial mediating role in the relationship between the warrior orientation and support for coercive policing, while self-legitimacy did not. When examining the indirect effects of the guardian orientation on support for coercive policing, neither self-legitimacy (β = −0.01) nor cynicism (β = 0.01) mediated the relationship.

Discussion

This study extended prior research and theorising on warrior and guardian policing orientations and their associations with support for different policing approaches. It specifically explored whether two psychological mechanisms (cynicism and self-legitimacy) explained why warrior-oriented officers tend to show greater support for coercive policing and less support for procedural justice policing, while guardian-oriented officers tend to show greater support for procedural justice policing and less support for coercive policing.

Main findings and implications

We found overwhelming support for Hypotheses 1–4, but only partial support for Hypotheses 5 and 6. First, we confirmed via factor analysis that the warrior and guardian policing orientations were conceptually distinct from each other (i.e. no cross-loading of items between factors). This supports Hypothesis 1 and findings from previous studies (e.g. McLean et al. Citation2020, McCarthy et al. Citation2024). Unlike those previous studies, however, we found that the guardian and warrior orientations were negatively, not positively, correlated. While the negative correlation might suggest the two constructs lie on opposite ends of the same continuum, the results of the factor analysis, coupled with a modest correlation, contradict this as a suggestion. Rather, there appears to be unique variance accounted for by both these constructs, suggesting they are indeed conceptually distinct. It is not clear why we did not find a positive relationship between guardian and warrior orientations across officers, however the use of different measures of these orientations across studies – which may tap into different aspects of attitudinal and behavioural norms – may explain this. Given the mixed results between studies, future research should ascertain whether the findings of the current study are a reflection of the measures used by testing whether the findings can be replicated in different policing jurisdictions.

Our study also confirmed Hypotheses 2, 3 and 4, again supporting previous research (see McLean et al. Citation2020, McCarthy et al. Citation2024, Murphy and McCarthy Citation2023, Schuck Citation2024). We found that officers who identified more strongly with the warrior orientation were less supportive of procedural justice policing (Hypothesis 2 supported) and were more supportive of coercive policing (Hypothesis 3 supported). In contrast, those who identified more strongly as guardians were more likely to support procedural justice policing (Hypothesis 4 supported). Surprisingly, we did not replicate prior research linking a stronger guardian orientation to reduced support for coercive policing (e.g. McCarthy et al., Citation2024, McLean et al. Citation2020). Hence, Hypothesis 5 was not supported.

Importantly, our study extended prior research on the warrior and guardian policing orientations by clarifying the possible psychological mechanisms that explain why warrior officers tend to support coercive policing, while guardian officers tend to support procedural justice policing. We proposed that officers’ level of cynicism toward the public and their confidence in their self-legitimacy would both mediate the relationship between the warrior/guardian orientation and support for coercive/procedurally just policing (Hypothesis 6). We found only partial support for Hypothesis 6. We found evidence that officers’ cynicism mediated the warrior orientation and support for coercive policing relationship; specifically, warrior-oriented officers appeared more likely to support coercive policing at least in part because they held more cynical views about the public (supporting Hypothesis 6). However, self-legitimacy did not mediate the warrior orientation/support for coercive policing relationship (Hypothesis 6 not supported). This latter finding contradicts Debbaut and De Kimpe’s (Citation2023) suggestion that heightened self-legitimacy should exacerbate officers’ support for coercive policing. We also found that officers’ cynicism and their self-legitimacy both partially mediated the negative relationship between the warrior orientation and support for procedural justice policing variables. That is, warrior-oriented officers were less likely to support procedural justice policing because they held more cynical views about the public and because they were less confident about their self-legitimacy (support for Hypothesis 6); here it seems officers who lack self-legitimacy might believe using procedural justice will further undermine their authority.

Contrary to our expectations, neither cynicism nor self-legitimacy mediated the guardian orientation/support for procedural justice policing relationship, or the guardian orientation/support for coercive policing relationship. Hence, neither cynicism nor self-legitimacy explained why guardian-oriented officers were more likely to support procedural justice policing or why they were less likely to support coercive policing (Hypothesis 6 not supported).

Our mediation effects have implications for both theory and police practice. They first suggest that future studies exploring the consequences of officers adopting warrior and guardian orientations on officers’ behaviour should consider and test possible psychological reasons underlying observed relationships. Our study points to the value of specifically including cynicism as a mediator in theoretical models linking policing orientations to police behaviour, and reflects the importance of cynicism as a starting point for better understanding policing orientations and their possible consequences.

With respect to police practice implications, the fact that cynicism partially mediated the relationship between the warrior orientation and support for procedural justice in our study, as well as the relationship between the warrior orientation and support for coercive policing, suggests that cynicism towards the public may be a particularly pernicious, and yet common-place, outcome of adopting a warrior policing identity.Footnote5 Previous scholars have argued that cynicism is an inevitable response to the nature of policing as an occupation (Caplan Citation2003), and thus has had a persistent influence on occupational police culture (Loftus Citation2010). Our study suggests that some policing orientations might be more likely to generate cynicism towards the public than others, with the guardian-orientation not associated with public cynicism. Indeed, high levels of cynicism may be a marker of officers who may be more prone to use coercive tactics and who require further training in guardian-oriented practices, such as procedurally just related communication skills, to remediate this.

Assuming warrior-oriented policing leads to cynical views towards the public, how might this arise and how might it be prevented? As noted earlier, a warrior-oriented mindset tends to entrench an ‘us and them’ mentality toward the public, with police conceptualised as metaphorical soldiers protecting society from descending into violent chaos (Stoughton Citation2016). This can engender a hypervigilant and suspicious approach to public encounters, particularly those occurring in high crime neighbourhoods. A focus on aggressive law enforcement and exertion of dominance in public encounters, along with the dis-incentivisation of non-enforcement and relationship-building encounters with the public, is likely to expose warrior-oriented officers more regularly to citizens in combative or conflictual contexts. The use of coercive approaches, the key toolkit of the warrior officer, is more likely to elicit defensive, non-compliant and resistant reactions from the public (Ali et al. Citation2022). The social distance and antagonism that evolves between officers and these communities can lead to a sense of alienation for officers, and reinforce their distrust of the public (Caplan Citation2003). The warrior approach and the responses it elicits can also thwart opportunities for more authentic, empathic, and constructive encounters with the public, thereby reducing the potential for enhancing mutual understanding and respect, and disabusing stereotypical beliefs (McCarthy et al. Citation2021, Murphy and McCarthy Citation2023). This is one way in which warrior-oriented policing may lead to, and subsequently entrench, cynical attitudes towards the public, and how they might contribute to the over-use of coercive tactics.

Practically, several strategies could be adopted by police agencies to reduce officers’ support for coercive policing. As our findings do not preclude the possibility that cynicism precedes the development of warrior-oriented attitudes, police agencies may benefit from adopting strategies that screen out cynical recruits at the earliest stages of the hiring process. Koslicki (Citation2022, p. 1) notes that agencies must ensure that their recruitment materials ‘reflect desirable skills and mindset’ as recruitment materials can inadvertently attract the wrong type of police officer. Koslicki (Citation2022) found that agencies that had collaborative problem-solving integrated into officers’ performance evaluations and those agencies that received grants to implement community policing were significantly less likely to advertise highly militarised messages to potential applicants. Thus, police recruitment materials that emphasise a more community-oriented approach to policing are likely to attract recruits that have a greater capacity for guardian-oriented policing, and to deter individuals with more cynical views of the public.

Noting that cynicism has been argued to be a bi-product of traditional occupational police culture (Caplan Citation2003), it is also important that officers who are recruited are trained in the skills required for guardian-style policing (e.g. procedurally just communication, community policing), combined with an organisational commitment to the central importance of building trust, legitimacy, and genuine partnerships with communities. A more wholesale commitment to guardian style policing may offer the best long-term potential for changing police culture and reducing the prevalence of warrior-oriented policing (McLean et al., Citation2020). Furthermore, encouraging officers to have more regular contact with community members in non-enforcement contexts, including through problem-solving partnerships to address crime and safety issues, and through recreational and community engagement activities (e.g. community barbeques; cultural celebrations; Neighbourhood Watch meetings, etc.) has the potential to reduce social distance between police and communities (McCarthy et al., Citation2021). They may also provide opportunities for breaking down stereotypes and prejudice and for showing cynical officers that the residents in their community are friendly, honest and also have interests in enhancing community safety (Brewer Citation1999, McCarthy et al. Citation2021). These types of contacts are particularly important for officers who may hold prejudicial stereotypes and see minority residents as dangerous and necessary to control (c.f., Carlson Citation2020).

Whether self-legitimacy offers a useful theoretical explanation for the relationship between warrior/guardian orientations and support for coercive/procedural justice policing was less clear from our results. We found that warrior-oriented officers were less likely to support procedural justice because they also had less confidence in their own legitimacy, but self-legitimacy did not mediate any of the other relationships we tested. The significant finding suggests that bolstering warrior-oriented officers’ self-legitimacy may promote greater support for procedural justice. Fildes et al. (Citation2019) found that officers were less likely to see themselves as procedurally just when they felt less confident in their interpersonal communication skills. Fildes et al.’s. study suggests that training in interpersonal skills may ‘be more effective than delivering training designed to increase positive attitudes to the public or training that focuses on … procedural justice’ (p. 201). This underlines the central importance of effective communication skills as a key enabler for enhancing officers’ support for more democratic and less coercive policing.

Limitations and conclusion

Before concluding we should highlight some limitations of our study. First, our support for procedural justice and coercive policing scales assessed officers’ support for these policing approaches. Officers’ actual use of procedural justice or coercive policing were not measured so it is unclear whether officers’ support for procedural justice translates to being more procedurally just in practice, or whether officers’ support for coercive policing translates to more coercion in practice. Frank and Brandl (Citation1991) suggest that when attitudinal measures are relevant to the target behaviour it is reasonable to expect they will be associated with the behavior of interest. But future research exploring the link between policing orientations and number of discourtesy or excessive use of force complaints levelled at officers, or scenario-based experimental research examining tactical decision-making, could overcome this limitation of our study.

Second, our survey data were cross-sectional so the causal relationships between measures in our models cannot be ascertained. For example, we proposed that adopting a warrior orientation leads to more cynical views about the public, but perhaps officers who display more cynicism may be more likely to adopt a warrior orientation. Future studies should tease apart the causal relationships proposed in our study by using either experimental research methods or following police officers over time to see how their orientations and subsequent behaviours might change. Relatedly, research that gives greater acknowledgement of the power dynamics, structures and occupational cultures that underpin cynicism or self-legitimacy is necessary to fully understand whether and why cynicism and/or self-legitimacy might mediate the warrior-orientation and support for coercive policing relationship.

Third, our response rate was low. It is possible that guardian-oriented officers or those who are generally more supportive of procedural justice may have been more likely to participate. We did find sufficient variation across our key independent variables to indicate an adequate distribution of types of officers in the sample. Nonetheless, replication studies are necessary to assess the robustness of our findings.

Fourth, there are numerous variables not included in our models that have been shown to predict officers’ attitudes to coercive force and procedural justice, respectively. For example, officer-specific variables (e.g. education level, prior military service), in addition to citizen-specific (e.g. citizen race, age, demeanour) and situation-specific variables (e.g. number of individuals at a scene, weapon present, type of policing problem (traffic stop, home invasion, etc)) can play a role in differentially predicting officers’ support for coercive force or procedural justice (see Mastrofski et al. Citation2016, McCluskey et al. Citation2005, Paoline and Terrill Citation2004, Shernock Citation2016). These omitted variables may also be associated in different ways with an officers’ proclivity to adopt a guardian or warrior mindset or procedurally just or coercive policing. Future research could explore the relevance of these additional factors as independent variables.

Finally, our guardian and warrior scales were adapted from Wortley’s (Citation2003) research on policing styles in Australia. As highlighted earlier, our survey was conducted before the recently published research on guardian vs warrior policing, where measures differed from ours (e.g. McLean et al. Citation2020, McCarthy et al. Citation2024; but see Murphy and McCarthy Citation2023). While both of our measures tap into a mix of officers’ beliefs, attitudes and social norms about how best to approach the task of policing and how to manage interactions with the public, we believe the measures reflect important dimensions of the guardian and warrior-oriented styles of policing as conceptualised in the recent literature (e.g. McLean et al. Citation2020, McCarthy et al. Citation2024, Stoughton Citation2016). However, we recognise there are different ways in which the two policing orientations could be operationalised. Whether guardian and warrior orientations should capture officers’ normative judgements, their perceptions of the consequences of certain policing approaches, or a mixture of both, is open for debate and highlights an avenue for future research. Future research should ascertain whether our findings can be replicated in different jurisdictions using our existing measures or when using alternative guardian and warrior scales.

Despite these limitations, our study has improved our understanding of guardian and warrior policing orientations. Specifically, our study proffers a reason why warrior-oriented officers tend to support coercive policing more than procedural justice policing. The findings explaining why guardian-oriented officers are more likely to support procedural justice policing and less likely to support coercive policing are less clear, however. Our study found that officers’ cynicism – and sometimes their self-legitimacy – may explain why a warrior orientation was associated with support for either procedurally just or coercive policing. Reducing officers’ cynicism of the public – particularly for officers who work in disadvantaged, high crime and ethnically diverse neighbourhoods – whilst also re-evaluating recruitment strategies and boosting officers’ training in communication skills, might enable greater support for procedurally just approaches and reduced support for coercive policing approaches. A broader move across police agencies towards more guardian-style policing might subsequently hold promise for reducing coercive policing in racial/ethnic minority communities, which will improve relationships with these communities.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Queensland Police Service (QPS) for their assistance with this research. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and are not those of the QPS. Responsibility for any errors of omission or commission remains with the authors. The QPS expressly disclaims any liability for any damage resulting from the use of the material contained in this publication and will not be responsible for any loss, howsoever arising, from use of or reliance on this material.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request from the authors. The data is subject to third party restrictions.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Other models of community policing exist. The ‘Broken Windows’ style of community policing – common in the 1980s in the US – advocated for zero-tolerance policing of victimless crimes (e.g. drug possession). That model of community policing was used widely to address the war on drugs (see DeMichelle and Kraska Citation2001).

2 Divisions are the smallest jurisdictional boundary, and tend to be organised around police stations. Each Division services several neighbourhoods and are largely responsible for the day-to-day policing activities of the agency. More specialised elements of policing (counter-terrorism, crime taskforces, forensics, water police) are generally managed centrally, with officers being dispersed to Divisions when needed.

3 Multilevel analysis of residual variation associated with officers’ Division on the dependent variables indicated an absence of significant variation that would warrant the use of a hierarchical or clustered model.

4 Multicollinearity diagnostics revealed no issues, with all Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) values remaining below 1.6. Given the negative correlation between the guardian and warrior orientation measures, we also tested interaction effects between these two measures on self-legitimacy, cynicism, support for procedural justice policing and coercive policing. None of these interaction effects were significant, so we do not report them here.

5 Of course we acknowledge that due to the cross-sectional nature of our data, it is also possible that cynical officers are more likely to adopt a warrior orientation to policing.

References

- Ali, M., Murphy, K., and Cherney, A., 2022. Counter-terrorism measures and perceptions of police legitimacy: the importance Muslims place on procedural justice, representative bureaucracy, and bounded-authority concerns. Journal of criminology, 55 (1), 3–22.

- Balko, R., 2013. Rise of the warrior cop: the militarisation of America’s police forces. New York: Public Affairs.

- Bayley, D., 1996. Police brutality abroad. In: W. Geller, and H. Toch, eds. Police violence: understanding and controlling police abuse of force. New Haven: Yale University Press, 273–291.

- Boivin, R., et al., 2020. The ‘us vs them’ mentality: a comparison of police cadets at different stages of their training. Police practice and research, 21 (1), 49–61.

- Bottoms, A., and Tankebe, J., 2012. Beyond procedural justice: a dialogic approach to legitimacy in criminal justice. Journal of criminal Law & criminology, 102, 119–170.

- Bradford, B., and Quinton, P., 2014. Self-legitimacy, police culture and support for democratic policing in an English constabulary. British journal of criminology, 54, 1023–1046.

- Brewer, M., 1999. The psychology of prejudice: ingroup love and outgroup hate? Journal of social issues, 55 (3), 429–444.

- Brown, R., and Hobbs, A. 2023. Trust in the police [online]. POSTnote 693. UK Parliament. Available from: https://post.parliament.uk/research-briefings/post-pn-0693/ [Accessed on 1 November 2023].

- Caplan, J., 2003. Police cynicism: police survival tool? The police journal: theory, practice and principles, 76 (4), 304–313.

- Carlson, J., 2020. Police warriors and police guardians: race, masculinity, and the construction of gun violence. Social problems, 67 (3), 399–417.

- Carmichael, J., and Kent, S., 2014. The use of lethal force by Canadian police officers: assessing the influence of female police officers and minority threat explanations on police shootings across large cities. American journal of criminal justice, 40 (4), 703–721.

- Clifton, S., Torres, J., and Hawdon, J., 2021. Examining guardian and warrior orientations across racial and ethnic lines. Journal of police and criminal psychology, 36, 436–449.

- Debbaut, S., and De Kimpe, S., 2023. Police legitimacy and culture revisited through the lens of self-legitimacy. Policing and society, 33 (6), 690–702.

- DeMichelle, M., and Kraska, P., 2001. Community policing in battle garb: a paradox or coherent strategy? In: P. Kraska, ed. Militarizing the American criminal justice system: the changing roles of the armed forces and the police. Botson, MA: Northeastern University Press, 82–101.

- Engel, R., 2001. Supervisory styles of patrol sergeants and lieutenants. Journal of criminal justice, 29 (4), 341–355.

- Engel, R., and Worden, R., 2006. Police officers’ attitudes, behaviour, and supervisory influences: an analysis of problem solving. Criminology, 41 (1), 131–166.

- Fildes, A., Murphy, K., and Porter, L., 2019. Police officer procedural justice self-assessments: do they change across recruit training and operational experience? Policing and society, 29 (2), 188–203.

- Frank, J., and Brandl, S., 1991. The police attitude-behaviour relationship: methodological and conceptual considerations. American journal of police, 10 (4), 83–104.

- Ingram, J., Terrill, W., and Paoline, E., 2018. Police culture and officer behavior: application of a multilevel framework. Criminology, 56 (4), 780–811.

- Joseph-Salisbury, R., Connelly, L., and Wangari-Jones, P., 2021. “The UK is not innocent”: Black Lives Matter, policing and abolition in the UK. Equality, diversity and inclusion: An international journal, 40 (1), 21–28.

- Kelling, G., and Kliesmet, R., 1996. Police unions, police culture, and police abuse of force. In: W. Geller, and H. Toch, eds. Police violence: understanding and controlling police abuse of force. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 191–212.

- Koslicki, W., 2022. Recruiting the warrior cop: assessing predictors of highly militarized recruitment videos. Journal of criminal justice, 79, 101896.

- Loftus, B., 2010. Police occupational culture: classic themes, altered times. Policing and society, 20 (1), 1–20.

- Mastrofski, S., 2006. Community policing: a skeptical view. In: D. Weisburd, and A. Braga, eds. Police innovation: contrasting perspectives. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 45–68.

- Mastrofski, S., Jonathan-Zamir, T., and Willis, J., 2016. Predicting procedural justice in police-citizen encounters. Criminal justice and behavior, 43 (1), 119–139.

- McCarthy, M., et al., 2021. The role of social distance in the relationship between police-community engagement and police coercion. Policing and society, 31 (4), 434–453.

- McCarthy, M., McLean, K., and Alpert, G., 2024. The influence of guardian and warrior police orientations on Australian officers’ use of force attitudes and tactical decision-making. Police Quarterly, 12 (2), 187–212.

- McCluskey, J., Terrill, W., and Paoline, E., 2005. Peer group aggressiveness and the use of coercion in police–suspect encounters. Police practice and research, 6 (1), 19–37.

- McLean, K. 2019. Is there any evidence concerning the Warrior/Guardian debate in policing? [online]. American Society of Evidence Based Policing. Available from: https://www.police1.com/research/articles/is-there-any-evidence-concerning-the-warriorguardian-debate-in-policing-y9hPZYjiBHXrY0cB/ [Accessed 1 November 2023].

- McLean, K., et al., 2020. Police officers as warriors or guardians: empirical reality or intriguing rhetoric? Justice quarterly, 37 (6), 1096–1118.

- Muir, W., 1977. Police: streetcorner politicians. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Murphy, K., et al., 2018. Police bias, social identity, and minority groups: a social psychological understanding of cooperation with police. Justice quarterly, 35 (6), 1105–1130.

- Murphy, K., and McCarthy, M., 2023. Confirming or resisting the ‘racist cop’ stereotype?: the importance of a police officer’s ‘guardian’ identity in moderating support for procedural justice. Psychology, crime & law, 29 (10), 1031–1053.

- Nix, J., et al., 2017. Police research, officer surveys, and response rates. Policing and society, 29 (5), 530–550.

- Paoline, E., and Gau, J., 2018. Police occupational culture: testing the monolithic model. Justice quarterly, 35 (4), 670–698.

- Paoline, E., and Terrill, W., 2004. Women police officers and the use of coercion. Women & criminal justice, 15 (3-4), 97–119.

- Paoline, E., Terrill, W., and Somers, L., 2021. Police officer use of force mindset and street-level behavior. Police quarterly, 24 (4), 547–577.

- Police Executive Research Forum, 2015. Re-engineering training on police use of force. Washington, DC: Police Executive Research Forums.

- Porter, A., and Cunneen, C., 2021. Policing settler colonial societies. In: P. Birch, M. Kennedy, and E. Kruger, eds. Australian policing. London: Routledge, 397–412.

- President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing, 2015. Final report of the president's task force on 21st century policing. Washington, DC: Office of Community Policing Services.

- Rahr, S., and Rice, S.K., 2015. From warriors to guardians: recommitting American police culture to democratic ideals. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, National Institute of Justice.

- Rosenbaum, D., Schuck, A., and Cordner, G., 2011. The national police research platform: the life course of new officers. Washington, DC: National Institute of Justice.

- Ross, C., 2015. A multi-level Bayesian analysis of racial bias in police shootings at the county-level in the United States, 2011–2014. PLoS One, 10 (11), e0141854.

- Schuck, A., 2024. Exploring the guardian mindset as a strategy for improving police-community relations. Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology, 39 (1), 82–92.

- Shernock, S., 2016. Conflict and compatibility: perspectives of police officers with and without military service on the military model of policing. Policing: an international journal of police strategies & management, 39 (4), 740–755.

- Silver, J., et al., 2017. Traditional police culture, use of force, and procedural justice: investigating individual, organizational, and contextual factors. Justice quarterly, 34 (7), 1272–1309.

- Stoughton, S., 2015. Law enforcement’s ‘warrior’ problem. Harvard law review, 128, 225–234.

- Stoughton, S., 2016. Principled policing: warrior cops and guardian officers. Wake forest law review, 51, 611–676.

- Tankebe, J., and Mesko, G., 2014. Police self-legitimacy, use of force, and pro-organizational behavior in Slovenia. In: G. Mesko, and J. Tankebe, eds. Trust and legitimacy in criminal justice: European perspectives. New York, NY: Springer, 261–277.

- Terrill, W., Paoline, E., and Manning, P., 2003. Police culture and coercion. Criminology, 41 (4), 1003–1034.

- Terrill, W., and Reisig, M., 2003. Neighborhood context and police use of force. Journal of research in crime and delinquency, 40 (3), 291–321.

- Trinkner, R., Kerrison, E., and Goff, P., 2019. The force of fear: police stereotype threat, self-legitimacy, and support for excessive force. Law and human behavior, 43 (5), 421–435.

- Trinkner, R., Tyler, T., and Goff, P., 2016. Justice from within: the relations between a procedurally just organizational climate and police organizational efficiency, endorsement of democratic policing, and officer well-being. Psychology, public policy, and Law, 22 (2), 158–172.

- Tyler, T., 2006. Why people obey the law. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Waddington, P., 1999. Police (canteen) sub-culture. An appreciation. British journal of criminology, 39 (2), 287–309.

- Weber, L., et al., 2021. Place, race and politics: the anatomy of a law and order crisis. Bradford: Emerald Publishing Limited.

- White, D., Kyle, M., and Schafer, J., 2021. Police self-legitimacy and democratic orientations: assessing shared values. Police science & management, 23 (4), 431–444.

- Wilson, J., 1968. Varieties of police behaviour. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Wolfe, S., and Nix, J., 2016. The alleged “Ferguson Effect” and police willingness to engage in community partnership. Law and human behavior, 40 (1), 1–10.

- Wortley, R., 2003. Measuring police attitudes toward discretion. Criminal justice and behavior, 30 (5), 538–558.