Abstract

Because of population aging, home-based e-care services (HBECSs) have raised interest among users and service providers. Recently, scholars have focused extensively on the needs and motives of older adults as care receivers that shape their pre-implementation acceptance of such technologies. Yet, little is known to date about post-implementation experiences and interrelationships between acceptance factors of market-ready services among care receivers and caregivers. To fill this research gap, an intervention study lasting up to eight weeks tested three market-ready HBECSs. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with seven informal caregivers and six care receivers. Qualitative analysis combining grounded theory with thematic analysis was used to present a thematic description of participants’ experiences and inductively develop a substantive model of HBECS acceptance and use. The results detail the impact and expected benefits of such technologies and various barriers to HBECSs use in conjunction with their functionalities and users’ social interactions. Acceptance and future use are determined by a complex mix of interrelated factors. These range from contextual circumstances to characteristics of the caregivers and care receivers to the service properties and perceived outcomes of use, such as safety, psychological relief, and peace of mind.

1. Introduction

The development of assistive technology for independent living at home in a rapidly aging population has become an important area of socio-technical innovation (Doughty & Williams, Citation2016). Research on how to combine various components into product bundles that integrate sensor- and interaction-based technologies has created new opportunities to develop home-based e-care services (HBECSs). These can include sensor-based solutions for the provision of health and care monitoring, communication platforms for formal and informal caregivers, services to keep older adults active and healthy, and platforms to enable social interaction among older adults and access to relevant community resources (Varnai et al., Citation2018).

The advances in the technological capabilities and the opportunity areas derived from their integration into HBECSs have raised interest among scholars and policy experts to speculate on potential social, health, and/or economic implications that the uptake of HBECSs would bring on the individual level, not only for older adults as care receivers but also for their informal/family caregivers (Cohen & Krajewski, Citation2020; Stroetmann et al., Citation2010). From the perspective of policymakers, Dahler et al. (Citation2016) argued that the most important expectations of such technologies relate to the reduction of care costs and improved quality of life for both care receivers and informal caregivers. Relatedly, Ward et al. (Citation2017) suggested that both groups would be encouraged to engage with HBECSs if, as end users, they believed that such products would really make a difference in the sense of making life safer at home. Especially, in cultural contexts where informal caregivers take the main burden of eldercare.

However, the positive outcomes for care receivers and caregivers can be translated from the individual to an institutional level only when a large enough number of target users take up such devices and services (Carers UK, Citation2013; Ward et al., Citation2017). In this context, the implementation of HBECSs has been a bittersweet success. For instance, while Zamora (Citation2012) estimated that coverage by telehealth or telecare of 10%–20% of older adults and the chronically ill population in the EU could generate a new market for products and services amounting to 10–20 billion euros, the ambient assisted living (AAL) market size in 2017 was much smaller, amounting to 186 million euros (Varnai et al., Citation2018). More recent estimations show that the global AAL market was valued at USD 1.25 billion in 2019, and it is expected to reach USD 3.80 billion by 2025, registering a compound annual growth rate of 21.6% during 2020–2025 (Research and Markets, Citation2020). However, the AAL household uptake in the EU was rather limited in 2017, spanning from 0.2% in Italy and 0.5% in Germany to a maximum value of 0.7% in Estonia. While the EU average AAL penetration rate was expected to grow from 0.3% in 2017 to 1.8% in 2021, this would only mean that the EU had reached the level of the US (1.7%) for 2017 (Varnai et al., Citation2018).

While the reasons for the slow scaling among end users are multilayered and difficult to grasp in empirical research (Probst et al., Citation2015; Varnai et al., Citation2018; Ward et al., Citation2017), Tsertsidis et al. (Citation2019) suggested that a potential explanation for these scarce outcomes is scholars’ focus on the pre-implementation stage (i.e., when a technology has not yet been used) dealing with adoption potentials of different technologies and combinations of HBECSs without considering their post-implementation stage (i.e., when actual use of a technology is present). In fact, drawing on various conceptual models (mostly deriving from Technology Acceptance Models—TAM), many scholars have studied social and personal factors that shape older adults’ and (informal/family) caregivers’ needs and motives for acceptance of HBECSs in settings where technology has not yet been used (i.e., the intention to use a technology; Peek et al., Citation2016, Citation2017; Smole-Orehek et al., Citation2019). Conversely, there remains a scarcity of studies focusing on market-ready HBECSs, which could better help illuminate how older adults and their informal caregivers—as the ones who eventually need to accept the technology and decide whether to use it in the context of eldercare—would accept them in their homes on a daily basis. To fill this gap, a qualitative intervention study with three commercially available HBECSs was undertaken in Slovenia to answer the following research question: What experiences and post-implementation acceptance and use factors of market-ready HBECSs among older adults and their informal caregivers emerge over a period of technology utilization in daily life in a country with a very limited penetration of e-care services?

In this paper, we first present an informative overview of prior research on acceptance factors of HBECSs, which helped us to delineate the research aims of our qualitative study. Then, the methods and procedures of the data collection and analysis are described in detail. The results provide a thematic description of HBECS experiences and propose a substantive model of e-care system acceptance and use. In the discussion, we articulate the relevance and importance of our study findings for research and practice as well as consider some potential avenues for future research that could overcome this study’s limitations. The last section concludes with some summarizing remarks.

2. Background

The acceptance factors of HBECSs have been studied extensively using various methods and across different contexts. Peek et al. (Citation2014) carried out the first systematic literature review focused on factors that would promote or inhibit the acceptance of technologies for independent living at home in order to assess any potential differences between the pre- and post-implementation stages. In this paper, the authors highlighted the differences between the factors, which occur in the two stages (Peek et al., Citation2014). Six groups of factors in the pre-implementation stage relate to: concerns regarding technology (e.g., high costs, activation of false alarms), benefits expected of technology (e.g., increased safety of older adults, reduced burden on family carers), need for technology (e.g., subjective health status), alternatives to technology (e.g., help by family or spouse), social influence (e.g., influence of relatives and/or professional personnel), and characteristics of older adults (e.g., socio-economic status, housing situation, familiarity with electronic devices). However, in post-implementation, social influence is not present, whereas concerns that become real problems and the experienced positive characteristics of the technology appear as relevant only when older adults started to use e-care service in their home environment. On the other hand, their study pointed to idiosyncratic distinctions that seem to be present within specific factors. For instance, among the 13 concerns regarding technology use that Peek et al. (Citation2014) identified in the reviewed studies related to the pre-implementation stage, only two (i.e., privacy implications, stigmatization) were present in post-implementation studies. A similar within-factor variability was observed for the factor related to expected/experienced benefits of technology (i.e., among the expected benefits, only increased safety was relevant in the post-implementation stage).

More recently, Tsertsidis et al. (Citation2019) carried out a replication of Peek et al.’s (Citation2014) study using their categories and themes as footholds for the categorization of acceptance factors. In such a way, Tsertsidis et al. (Citation2019) sought to compare the factors influencing the acceptance of technology in the post-implementation stage in two systematic literature reviews. The authors defined the post-implementation stage according to the Technology Readiness Level (TRL) scale with values of five or higher, indicating that digital technologies for aging in place have both been developed and tested in the laboratory and validated in relevant environments. Interestingly, their results mainly corroborated the early findings of Peek et al. (Citation2014). Notably, they discerned six themes of factors, where five overlapped with Peek et al.’s (Citation2014) typology—the only exception was social influence, which replaced alternatives in Peek et al.’s model. Content-wise, the composition of single factors was similar, although the level of granularity was somewhat higher—which is reasonable because more studies were included in Tsertsidis et al.’s (Citation2019) review (23 vs. 4).

Based on their findings and the evidence-based summation of prior post-implementation studies (i.e., Liu et al., Citation2016; Peek et al., Citation2014), Tsertsidis et al. (Citation2019) drew a set of research gaps and implications for future research. Among them, four seem particularly relevant to the issues of slow and scarce adoption of HBECSs. First, in comparison with the pre-implementation stage, there are still few investigations on post-implementation acceptance factors, and only a handful of those are based on longitudinal studies that would enable participants to test HBECSs over an extended period of time. Second, only seven studies included commercially available technologies (i.e., TRL 9), and none of those tested more than one digital technology for aging in place. Consequently, only one study included an e-care TRL 9 service, and only one (at least) indirectly investigated acceptance factors through the lenses of the relationship between care receivers and caregivers. In particular, informal caregivers were largely overlooked in prior literature, although their role in eldercare has become increasingly important with limited access to paid assistants and public services (Carretero et al., Citation2015; Hlebec et al., Citation2016). Moreover, there seems to be a discrepancy between their low level of digital proficiency and their central role in decision-making processes related to the purchase of HBECSs for care receivers’ homes (Carretero et al., Citation2015). Third, despite the acknowledgment that acceptance factors constitute a network of interconnected adoption mechanisms of HBECSs (Peek et al., Citation2017), the research that would attempt to map out such interconnections in the post-implementation is limited in scope (i.e., focusing on a few groups of factors) or inconclusive. Finally, all studies considering acceptance factors in the post-implementation stage of TRL 9 services were conducted in highly developed Western countries (i.e., the Netherlands, the US, and Australia). Accordingly, they offer a limited generalizability from a cross-cultural perspective because the models of provision of care for the elderly in countries with, for example, a liberal welfare regime in contrast to conservative-corporatist or social-democratic type (Esping-Andersen, Citation1990) may vary substantially in other regions, such as South and Eastern Europe. Moreover, these regions are characterized by care regimes that depend strongly on family care, that is, familialism (Hlebec et al., Citation2021; Saraceno & Keck, Citation2010). In 2013 for instance, 75.5% of people aged 65+ who received some form of care at home in Slovenia received only informal care (Hlebec et al., Citation2016). Thus, we find benefit in a contribution from a post-socialist country with a combination of conservative-corporatist and social-democratic model, along with underdeveloped long-term-care system and strong family elderly care responsibility.

Against this backdrop, a small-scale intervention study was undertaken with the aim of capturing the experiences of a prolonged test period of HBECS use and thoroughly investigating acceptance factors and their interrelationships. We understand acceptance as how users embrace, take full advantage of, and intend to continue using the technology. This study presents a qualitative analysis of semi-structured interviews conducted with dyads of older adults and their informal caregivers (see Sections 3.1. and 3.3.) with the aim of extending the existing body of literature on post-implementation acceptance factors by accomplishing the following: (1) including three different market-ready HBECSs; (2) exploring the dynamics of technology acceptance in an intervention study lasting up to eight weeks; (3) integrating the views of older adults as care receivers and of their informal caregivers; and (4) providing evidence from an EU country, such as Slovenia, with the informal care-based regime accompanied by an immature market for HBECSs.

3. Method

3.1. Intervention design

A small-scale intervention involving 34 participants was undertaken in collaboration with the largest telecommunications operator in Slovenia. The assessment of the intervention was based on a mixed-methods approach (Creswell & Plano Clark, Citation2011) consisting of quantitative and qualitative parts. While the results of the quantitative part, which included two questionnaires at baseline and post-intervention, are presented in Dolničar et al. (Citation2017), the focus of this article will be on the qualitative part. Semi-structured interviews were conducted in seven dyads on a subsample of 13 participantsFootnote1 since in one dyad the care receiver could not be interviewed due to illness. Each dyad was comprised of an older care receiver and an informal caregiver who was their relative and who remotely monitored events recorded by e-care systems installed in the home of the care receiver. Each dyad used one of three different HBECSs (see Section 3.2) for 6–8 weeks between August and October 2016 (Min = 47 days, Max = 59 days, M = 53 days). Members of the telecommunications operator support team installed, monitored, maintained and removed HBECSs from participants’ homes.

At all stages of the intervention and research process, we followed the Code of ethics for researchers of the University of Ljubljana. All participants were aware of the nature of the research and its objectives. Participants were aware of their right to withdraw at any stage without giving a reason. They also signed an informed consent form, giving their permission to use the interviews as research material.

3.2. Apparatus

Three selected commercial HBECSs (Essence, LivOn, and CMIP) encompassed various combinations of sensors connected to the central hub unit. This unit gave informal caregivers and service providers—via a care assistance/call center (for practical reasons, we use the term call center in the rest of the text and the abbreviation CC in the graphics)—access to monitor data and status notifications using a smartphone app or web-based platform. The specific characteristics of each tested HBECS are shown in . In this study, we tested the sensors and features of each HBECS as follows: We installed Essence motion detectors that identified entrance and alerted for extreme temperatures, door/window sensors reporting the status of doors and windows to determine whether someone enters or leaves the premises, and a portable emergency button that can be worn as a pendant or wrist strap. The LivOn system was composed of a base unit, activity sensors, and a help trigger (i.e., emergency button), whereas the CMIP unit was supplied with a wrist radio trigger and a fall detector. In all cases except one, all participants constituting a dyad (i.e., care receiver and informal caregiver) tested the same service. Notably, Essence was tested by three dyads, whereas LivOn and CMIP were used by two dyads each. Although the service provider recorded when alarms were triggered, due to GDPR restrictions, we could not analyze any specific event. However, in the interviews, we discussed four emergency alarms triggered by one of the dyads, two alarms by another dyad, and one alarm each by two dyads. For three of the dyads, there were no emergency alarms triggered during the testing period.

Table 1. Comparison of the tested HBECSs’ features.

3.3. Participants

All seven informal caregivers (hereafter referred to as caregivers) were family members or close relatives who provided some degree of care or assistance with activities of daily living, which was typically unpaid. They were between 27 and 57 years old (M = 45 years). Two caregivers were women, and five were men. They were all employed with a university or higher education degree and some experience with information and communication technologies (ICTs). During the last 12 months, four had provided more extensive informal care to their care receivers. During the testing period, three caregivers monitored the activities of the care receiver every day, two once to twice a week, and two less than twice a week. The six interviewed care receivers were between 61 and 93 years old (M = 80 years). Four were men, and two were women. All were retired, and most had a secondary-level education. Four lived alone in a house or apartment building, and two care receivers lived with another person. Three care receivers could move unassisted, while the other three were mobility impaired, using mechanical transfer aids, such as walking sticks or walkers/rollators.

3.4. Semi-structured interviews

Drawing on the typology of post-implementation acceptance factors proposed by Peek et al. (Citation2014), a semi-structured interview guide was developed using sensitizing concepts (Bowen, Citation2006). The questions focused on care receivers’ and caregivers’ experiences with the tested HBECSs, their attitudinal disposition toward perceived short- and long-term outcomes of utilization, their intention for further use, and their social interactions. While this framework provided sensitizing concepts that guided the interview topics, particular questions were asked and topics discussed based on each participant’s specific information collected during the interview. This allowed for a more detailed and bottom-up insight into the reasons for the experiences and opinions, which helped to map an exploratory/explanatory network of relationships between inductively identified acceptance factors.

Semi-structured interviews were conducted face to face after the end of the intervention in November 2016 in a quiet setting of the interviewees’ choosing that ensured their privacy and was free of distractions. They lasted 30–90 min. Participants were offered an incentive in the form of a gift card in the amount of 20 euros before participation in the interviews. All interviews were carried out in the spoken Slovene language, audio recorded, and fully transcribed verbatim. The transcripts were double-checked for accuracy by listening to the recordings twice. To ensure the anonymity of participants, their names were removed from the verbatim transcripts of interview recordings. Quotations presented in this study were translated into English by a native speaker.

3.5. Data analysis

The interviews provided a finite amount of data; hence, our approach to qualitative analysis and results is characterized by the combination of the principles used in grounded theory (Corbin & Strauss, Citation1998) and thematic analysis (Boyatzis, Citation2005; Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). The decision to use this methodological procedure was intentional because we were aware from the beginning of the qualitative phase that we would not be able to use theoretical sampling and ultimately produce a comprehensive grounded theory. However, we attempted to go beyond a thematic description of the field and tried to inductively develop a substantive conceptual model of e-care system acceptance and use valuable for future research. Both qualitative approaches mentioned above share common epistemological underpinnings. After becoming familiar with the transcripts, we used the following coding procedure common to thematic analysis and grounded theory as a collaboration between six investigators: First, a line-by-line open coding of key interview sections was performed. A procedure proposed by Graneheim and Lundman (Citation2004), where a meaning unit is first identified, followed by condensation, and finally, labeling, was used to assist in naming codes. Researchers then discussed their codes in an iterative way until agreement was reached and key codes were identified, along with a narrowing of content areas and topics of analysis. Using the constant comparative method as it is known in grounded theory (Corbin & Strauss, Citation1998) we first developed concepts which were later grouped together to form categories by identification of similarity and difference within and across categories. These formed four key themes which were further explored and descriptively presented in showing the thematic ‘map’ of the HBECS experiences. Subsequent analysis intended to provide a higher explanatory level employed distinctive grounded theory procedures such as axial coding and the use of coding paradigm, and to a lesser extent, selective coding. Thus, the aforementioned concepts and categories were linked into groups of factors to form a substantive conceptual model of HBECS acceptance and use. The qualitative research material was analyzed with the help of Atlas.ti and Dedoose software.

4. Results

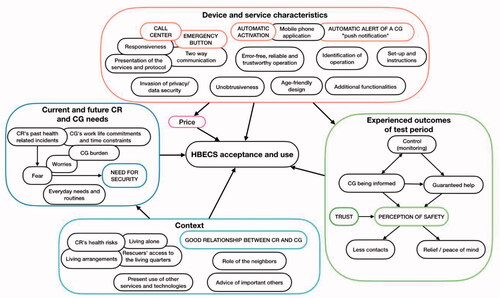

In this section, we present the experiences of HBECS use by caregivers and care receivers. First, we show a thematic description of the field (); second, using grounded theory procedures we then explore the complex relations affecting acceptance and use in a substantive conceptual model ().

Figure 2. Model of home-based e-care system acceptance and use. Note: Key factors in each domain are displayed in capital letters and framed in color. Bubbles attached to each other illustrate a relation between the contents. Connections among the factors across the domains are omitted for clarity and are described in text. HBECS: home-based e-care service; CR: care receiver; CG: caregiver.

4.1. Thematic description of the HBECS experiences

In the analysis, four major themes were identified from the data. These were named functionalities, impact and expected benefits, social interactions, and barriers to further use. They are presented graphically in and described in greater detail below.Footnote2

4.1.1. Functionalities

The first central theme concerns the discussion around functionalities of the HBECSs in that it pertains to the needs, the use, and the impact that it has for older adults. Participants reported their experiences and evaluated their use of the functionalities of HBECSs within the following four categories: key functionalities and characteristics (incorporating an important subcategory: call center (CC)), desired additional functionalities for health and wellbeing, desired additional functionalities for sense of security, and suggestions for improvement (with the improvement of inappropriate operation subcategory).

Among key functionalities and characteristics, not surprisingly, interviewees attached importance to error-free, reliable, and trustworthy operation of the HBECS. Understandably, age-friendly design and system features were desired, as was a design that would accommodate everyday needs and routines. Users highlighted the importance of an emergency button and clear identification of system operation. The emergency button on a central unit or as a wearable option should have the right size and activation sensitivity to be usable in emergencies, but at the same time, prevent unintentional activations. Participants also appreciated the possibility of two-way communication between them and the call center, which would enable a clarification of any risky situation before activating further assistance. In addition, the participants pointed out the need to know that the device or its sensors are working properly. Thus, a clear indication of correct operation was understood as important:

Caregiver, 27 years (Essence): It was interesting in the beginning, yeah. Because I installed the device alone, I assembled the whole thing alone, and then the device stays there passive and there’s no activity. Now it stands there; if it’s working or not, you don’t even know until something happens.

HBECSs should be able to automatically alert the user if, for instance, a sensor fails, and they should provide a possibility for the user to verify the system’s proper operation. Another characteristic of increasing importance in the participants’ view is the automatic nature of the device operation in case of adverse events (e.g., a fall). In particular, automatic alerts of a caregiver via so-called ‘push-notifications’ were underlined as essential:

Interviewer: Would this [push notification] be a condition for you to use this service further or buy it?

Caregiver, 44 years (Essence): Yes, absolutely, definitely. ’Cause if not, I mean, it is crucial. I want to be alerted. If you’re paying for something, you want to be alerted.

Interviewer: So, these are your key suggestions for improving this service.

Caregiver, 44 years (Essence): Yes! There are two major points—feedback to the caregiver and being able to adjust it … for the house.

Participants suggested that, during the installation process, technicians should refer to user manuals, carrying out a demonstration of service operation in a manner adapted to the needs and abilities of end users. This would enable them to become familiar with device/service functions, thus avoiding false expectations and improper handling of the device.

However, the call center is the key subcategory regarding the service functionalities. It plays a central role by gratifying the needs of care receivers and caregivers through its positive impact on expected benefits. This central role also makes it an increasingly sensitive topic for the users. Satisfaction with the call center depends on its responsiveness (i.e., returning the call), activating assistance, and contacting the primary caregiver:

Caregiver, 27 years (Essence): Actually, I don’t have a lot of experience with how it works if there are actually problems, if there’s actually an alert … What is the process?

The role of the call center in the intervention was not clearly explained to participants during the installation of the HBECS. This was reflected in the participants’ responses, in particular, with reference to the protocol after triggering an alarm or emergency call. Knowing the latter is extremely important, as it contributes to a greater sense of security. For participants, care receiver’s security is perceived as the key added value of HBECS and is largely provided by a responsive call center. If there is an irregularity in connection with the call center (e.g., the call center does not return the agreed call), trust in the HBECS drops significantly. In contrast, satisfaction with the call center is associated with greater trust in the HBECS. However, there are some indications that both groups expected that call center support would be focused on more than dealing with emergencies and life-threatening events. Rather, it was perceived that the call center should play a supportive role in fulfilling at least the most basic needs of care receivers regarding socializing and emotional exchange (i.e., social calls).

Next, during the intervention, participants generated new ideas regarding potentially useful additional functionalities of HBECSs. We have divided them into two categories: additional functionalities for health and wellbeing and additional functionalities for sense of security. Health-related wellbeing could be improved by such features as automatic fall detection, medication reminders, and activity and vital parameters monitoring. Alternatively, participants were convinced that upgrading HBECS with a fire alarm, gas detection, and anti-theft alarm would improve their general sense of security. According to a 78-year-old care receiver:

Care receiver, 78 years (Essence): Besides the fact that it’s a monitoring device, it has another plus, which is that … fire alert. Erm, for example, I tend to forget and I watch TV, and then fall asleep, and I forget I was cooking…. And it burns. And even if the water is boiling too much, the steam, too much steam, the fire alarm starts yelling/…/especially those alarms that are connected to fire, and to suffocation, we need those.

Another category relates to participants’ suggestions for improving users’ experiences with the HBECSs. These spanned from design corrections (e.g., improving the ergonomics of wearables, belt softness, illumination, and volume adjustability) to improved signal range and more comprehensive, user-friendly user manuals (see ). The subcategory improvement of inappropriate operation encompasses participants’ suggestions for improving and removing the identified malfunctions, for instance, problems with sensor operation, unwanted and oversensitive activations, and calls for an upgrade with additional sensors and feedback possibilities. Whereas some of the shortcomings were not considered overly worrisome, conversely and understandably, others were even seen as barriers to further use (see faulty operation in ) if not amended.

4.1.2. Impact and expected benefits

This theme considers the desired effects of HBECS use by care receivers and caregivers. Based on the reports of our users’ experiences, four tightly linked categories were elaborated. Via monitoring and surveillance control enables guaranteed help and a perception of safety—a key benefit in the eyes of the users that ultimately contributes to relief among both care receivers and caregivers.

A guarantee of help in case of need increases the sense of security and reduces fear among HBECS users; moreover, it potentially has an indirect health benefit. Caregivers reported being relieved and less worried while using the service because they recognized the HBECS as an additional backup option as “someone or something” that their care receivers can rely on in case of their unavailability and/or longer absence. In this sense, a benefit takes the form of psychological reassurance and peace of mind, but it can also decrease the physical and logistic burdens of caregivers, for instance, the need for “checking up” on care receivers, which can be reduced with the HBECS. One of many quotations underlines this important finding:

Caregiver, 35 years (LivOn): Um, many times it crosses my mind—How is mum? How’s dad doing? Are they okay? Then, every now and then, you call, and maybe they don’t answer right away. And you start thinking, damn, what if something happened, what if…/…/I am a bit worried for them. We talk to each other over the phone, but often, there is no time. Or … I have a bunch of meetings and I can’t call. In that moment, I could simply open the app and take a look, couldn’t I, and I could somehow be reassured.

Care receivers are expected to accept a certain amount of control and monitoring through sensors to be able to receive assistance. Control provides caregivers with insight and makes them informed about the care receiver’s situation. This control prevents the two sides from perceiving monitoring in a negative sense, although they have some concerns about the invasion of privacy (see Section 4.1.3.). A fundamental dilemma of care receivers seems to be tolerating monitoring and protection or accepting the health risks that may emerge with the “uncontrolled” privacy of everyday life.

Control offers caregivers insight into the life of a care receiver even when physically absent, and it replaces the “classic” checking up via a phone call, which is more time-consuming and exhausting. To a certain extent, surveillance relieves caregivers (i.e., diminishes fear and provides relief) and gives them a sense of security, which is one of the key leverage points for HBECS uptake.

In the case of a good and close relationship between care receiver and caregiver, the negative aspects of control are less of an issue. Hence, perceived benefits outweigh potential privacy concerns and unease related to monitoring and surveillance implications. Surprisingly, monitoring might even create new social interaction opportunities. Participants reported increased attention and communication between them, with HBECS representing a new topic of conversation. It is also interesting that care receivers reported more intentional physical movements around the living facility. They were aware that their caregivers could now see how much they moved around, and because they did not want to appear passive or even trigger an alert, they moved more. However, we can probably attribute these consequences to the initial period of service use and suggest that they may subside later.

An important benefit comprises the issue of (perceived) safety. This category involves the positive effects HBECS use has on fear and a greater sense of security and safety. In the context of health problems, awareness of a possible adverse event can trigger fear (specifically of not being able to access appropriate help quickly). Feelings of fear can be diminished, and a greater sense of safety and security can be achieved by the desired operation of HBECS. Specifically, care receivers’ apprehension can be reduced by automatic triggering of the alarm in the event of accidents and by the reliable availability of a responsive HBECS call center.

4.1.3. Barriers to further use

Our analysis indicated five different categories of barriers to further use. First, service shortcomings seem to be the main barrier. This especially relates to users’ needs and perceptions about the tested service/device and what it could do for them. Some of our interviewees explained that HBECS did not fulfill their present needs. However, they also admitted that a similar service might become relevant in the (near) future. Consequently, they reported a small or insufficient added value for the use of HBECS. While care receivers who were quite autonomous in their daily lives were put off by the overlap of functions with already used devices/practices (e.g., mobile phones, alarms), which sufficiently fulfill their present needs, more vulnerable care receivers missed additional social care services, such as social calls, home visits, and ultimately, a contribution to the nursing care that they may need.

The second category, lack of trust, was found to be an important inhibitor of acceptance and further use. Distrust may relate to device operations or service providers. On the one hand, trust mostly depends on key device and service characteristics, and on the other, it is related to security and perception of safety. Without trust in the faultless operation of HBECS, there cannot be a genuine perception of safety. The presence of a call center and its impeccable and fast operation are also very important for trusting HBECS. In addition, participants’ trust would be strengthened if there were an indicator on the device showing whether the system/device is operating properly. Importantly, trust in the operation of the device/service can be strengthened or undermined by previous emergency experiences, which establish a need for trustworthy assistance.

During the purchase decision making, the initial credibility and trust in the HBECS provider and the presentation of the service (e.g., the involvement of medical doctors in the service marketing) seem to play an increasingly important role. Another interesting aspect of lack of trust, which may hinder the use of the device, pertains to the close relationship and trust between care receivers and caregivers. For example, if the care receiver does not trust the caregiver to be readily available, vigilant in checking the application, or acting in the care receiver’s best interest, the care receiver may be hesitant to trust the caregiver with his/her life in the case of emergency.

Interestingly, participants mentioned other, somewhat less critical barriers, which are presented in the next category. They were concerned with different forms of faulty operations in HBECSs in the intervention. These ranged from minor nuisances, such as device or sensor failure, inappropriate or limited sensor coverage, and unwanted automatic activation of alarms to more problematic experiences when the device or service did not work as promised. Although the intelligent system was expected to learn the behavior patterns of care receivers and report any potential deviation, this did not always occur in the intervention. Further, on some occasions, the call center did not return the call when the alarm was raised. This critical issue was pointed out by two caregivers:

Caregiver, 50 years (Essence): Sometimes there’s—sometimes, a sensor might not work. For example, it doesn’t work, or her movement caused one sensor to go off and the other didn’t. So, sometimes I don’t know whether she went to bed at 10 pm, and she went to the toilet at 1 am, and that sensor in the bathroom stayed on, like she’s still in the bathroom.

Caregiver, 27 years (Essence): My granny was away for a whole day—she went on a trip, and there was nothing. Nothing happened. The system didn’t alert us. Now, from the point of view of trust, the trust declines a bit here. I expect that, if a person who should be in care is away for a whole day, the system should alert us, you know.

However, such negative experiences do not seem to turn them away from potential further use. We may attribute this to the awareness of the testing period situation and our participating users’ expectations that malfunctions will be fixed by the reputable HBECS provider. Alternatively, we can speculate that, at least for some, the caregiving situation leaves them with no better alternative, so they have no choice other than to accept what it is offered.

The next category, privacy concerns, plays a similar role in further use. As mentioned above, HBECS users perceive safety and security mostly in terms of contributions to physical and psychological health. However, accounts of privacy and data protection concerns were also reported. For instance, a younger caregiver said:

Caregiver, 35 years (LivOn): No, certainly no one wants to have data leaking where they shouldn’t be, right, for someone to abuse the data. Erm … to sell them, like some insurance companies perhaps did it before. Erm, this, well this would totally collapse the system of values. /…/ [The] security factor, privacy factor is very important. And you have to, they have to always have a sense that I’m, that a relative can see, or perhaps the doctor, or a nurse, who monitors them and that this is it, you know. So that not the whole world can see something about them.

Although issues were raised about data security within the system and overcontrol of the care receiver by the call center or caregiver, a much more interesting and decisive barrier appeared to be the notion of a breach of privacy. Care receivers were mainly concerned about surveillance and monitoring because they were afraid that the service would allow for the invasion of their privacy. This feeling mainly arose because of a lack of knowledge about the operation of the device, as some participants assumed they would be videotaped. Such concerns were significantly alleviated when/if their caregivers explained the operating principles of the service, as in the case of a 44-year-old caregiver:

Caregiver, 44 years (Essence): Amm, there were concerns because of control. But I told him, I’m the only one watching this./…/that I won’t control him. I gave him an option: We won’t give you the sensor then. I don’t know, we’ll put it in the hallway instead of the bathroom, if that’s a problem. But he said it wasn’t. But you can adjust the sensors, right?

Minimizing intrusion into privacy, which is closely linked to the degree and frequency of monitoring, appears to be a condition for the use of the service. Adequate user instructions and presentation would reduce the concerns of both care receivers and caregivers. More surprisingly, some interviewees pointed out the obtrusiveness of the device (i.e., illumination or noises from the sensors or the device) as possibly hindering their daily routines and habits, and this issue may be a barrier for further use. A particular finding relates to the unpleasant feeling at automatic triggering experienced by care receivers when (involuntarily) interacting with the device in general and even more so with the emergency button. The following quotation describes the experience of an 81-year-old care receiver:

Care receiver, 81 years (LivOn): I was dusting once, and I pressed the button, and someone immediately answered and asked, “Ma’am, what’s wrong?”

Our analysis revealed that unpleasantness is caused primarily by immediate contact with the call center and fear of unnecessary home visits in the form of rescuers, firefighters, etc. Unintentional triggering illustrates a lack of knowledge about the operation of the device because of insufficient training and the excessive sensitivity of the emergency button on the central unit. Consequently, care receivers avoided interacting with the button or the device by moving the emergency button to a place out of reach. Of course, such behavior presents new risks when a critical adverse event happens and the care receiver cannot activate the emergency call.

Finally, the price of HBECS could play a role in further use for some users. The interviewees desired an acceptable monthly subscription rate, which would amount roughly 20 euros in their view. Tellingly, the money they wanted to spend on such service was compared with an average monthly mobile phone plan or a monthly health insurance premium. Concerns were raised about future price increases and hidden costs because of previous (negative) experiences with telecommunication companies. Nonetheless, users understood that additional hardware or service extensions would justify HBECS price hikes or premium charges.

4.1.4. Social interactions

The last theme highlights the importance of interpersonal relationships among the users. The care receiver–caregiver relationship represents the key category because its very existence and nature represent a condition for HBECS use. HBECS characteristics demand the relatively intensive involvement of a caregiver; paradoxically, this largely excludes those socially isolated older adults in need, such as those living alone, without relatives and/or those without close and positive relationships with their relatives or significant others.

One factor that contributed to higher acceptance of HBECS among family members who have good relationships was the amount of control and surveillance, which is easier to accept among closely tied family members. Another factor was the need to handle and assist with—or at least interpret, explain, or clarify—the operation of the technically sophisticated device to the care receiver. This characteristic of HBECS use among close family members may be why interviewees reported no negative effects of HBECS use on their relationship. However, these associations may be moderated by the heterogeneity of family situations, where various and potentially opposing needs between the two groups may affect the relationship differently, even leading to a deterioration of the relationship. However, some collected material indicates that, out of necessity and frequent contact, the use of HBECS can act as a bonding element in a relationship. Further, in the context of familialism and within those caring family relationships, a contact with the elderly is seen as a duty or a kind of moral obligation. Thus, the use of HBECSs can fulfill this obligation, as demonstrated by the latent meaning of the following excerpt, in which the care reciever comments on whether both sides invest in the relationship by using the service:

Care receiver, 75 years (Essence): Yes, I think that we both do, don’t we? I do so with gratitude that they worry about what is happening to me, and they do so in that they have done something for me when they are not around for the whole day.

Despite the reports that the relationship remained the same, the contact frequency or its quality/content has changed, which may have both desired and less desired consequences. For instance, HBECS remote monitoring has elevated caregivers’ attention to care receivers, resulting in an increased number of daily (mediated) contacts. Even improper operation of the device resulted in additional communication and more frequent interactions. A downside of HBECS use, from the care receivers’ perspective, was the possibility that remote monitoring would result in less frequent visits. Although this can be a desired outcome for caregivers, it may negatively affect care receivers’ willingness to engage in further HBECS use.

A specific category discerned from the data is the role of the care receiver’s neighbors. Caregivers often rely on them when they cannot contact care receivers or when there is a need to assist care receivers in person. Neighbors are often the first to come to their aid in the case of an emergency, inform their relatives about events, and/or act as auxiliary caregivers. However, as in the case of a 78-year-old care receiver and a 44-year-old caregiver, all this depends on having good and trusting relationships with neighbors:

[Answering the question of whether he agreed that neighbors could be notified in the event of an emergency] Care receiver, 78 (Essence): I think we could, if the neighbors were normal, especially those who are permanent, you know. For example, my neighbors still have the key to my front door, you know.

Caregiver, 44 (Essence): If he [CR] has health problems, he [the neighbor] calls me. I don’t know, he’s been sick, and the neighbor called me.

Another important category within the theme of social interactions is the decision-making process. The initiators for the use of the service were usually caregivers, who could also use certain persuasive strategies for the uptake of HBECS. However, the heterogeneity of life situations and family relationships means that, in various dyads and at different stages, the roles of key initiators and decision makers may also be inverted or taken by other significant others, such as doctors, nurses, or neighbors. Indirectly, we could also infer from our data that primary caregivers who are expected to provide help with the decision-making, purchase, installation, and operation processes for the HBECS will be closely involved with it. Hence, it is crucial that they demonstrate adequate digital skills to receive the full benefits of the HBECS.

Finally, different situations in which the decision-making process takes place (e.g., ad hoc after an accident or under unforeseeable circumstances) affect its dynamics and can change the roles of the stakeholders involved. The triggers are usually health problems among care receivers, awareness of possible rapid changes in their health status and related care burdens and concerns, as well as the interest of care receivers in HBECS driven by word of mouth.

4.2. Substantive model of e-care system acceptance and use

In this section, we present a further attempt to organize the thematically displayed landscape by assembling the mentioned relationships and dependencies among key acceptance factors into a substantive explanatory model of HBECS acceptance and use (see ).

At the outset, current and future care receiver and caregiver needs drive the contemplation for HBECS use. Not surprisingly, these needs are influenced by the context and arise from specific care receivers’ and caregivers’ circumstances, such as care receivers’ health risks and living arrangements and caregiver’s caring possibilities determined by work–life commitments and time constraints. However, the occurrence of critical health-related incidents (e.g., a fall, a stroke) seems to be the key factor in considering and deciding to adopt an HBECS. Fear of recurrence of these critical and potentially dangerous events, together with the concern of not being able to access rapid and appropriate assistance, are major sources of worry for care receivers and caregivers.

Increasing needs for security, personal safety, and wellbeing stem from age-related health declines that diminish care receivers’ ability to live at home independently. Accordingly, health problems considerably increase the need for care and control (monitoring) of older adults by their caregivers. An older care receiver, for instance, explained what it meant to her to use the tested HBECS:

Care receiver, 81 years (LivOn): I feel surer, safer, don’t I?

Interviewer: Something else, maybe?

Care receiver, 81 years (LivOn): Well, I don’t know. So that I’m not, how should I put it, always tense. When I came home from the hospital, I said, oh no! Now it will throw me out. Now it will throw me out [referring to stroke], and then what? That fear, right—that you are alone, right.

HBECS use highly depends on a good and close relationship between the care receiver and caregiver and is suitable for family situations where a care receiver lives alone. Furthermore, there should be a high degree of caregiver emotional attachment and burden (actual and/or perceived) associated with providing care.

Corresponding to the users’ needs, the outcomes of HBECS use should above all enhance the perception of safety and provide a feeling of relief among caregivers and care receivers. On the one hand, psychological aspects of relief arise from the reduction of anxiety and apprehension, and in turn, contribute to peace of mind. On the other hand, behavioral aspects of relief refer to the decrease in the actual physical and logistic burdens of caregivers. These desired effects of HBECS use are preceded and conditioned by users’ trust in the service’s ability to inform the caregiver of the care receiver’s situation, guaranteeing appropriate and timely help via control and monitoring. For example, a 44-year-old caregiver explained:

Caregiver, 44 years (Essence): You don't have to ring Dad to see if everything is okay with him because you simply look at the application.… So, that … part of the communication fades away, since you simply look at the telephone and see what’s happening.

However, both sides shared a concern that remote monitoring would lead to a decrease in the number and quality of contacts, including in-person visits between them. This is perceived as a potential disadvantage of HBECS use. Moreover, in-person contacts play a role in socializing as they allow opportunities to maintain and strengthen personal support networks. In this sense, the factors portrayed in can have a wider impact on users’ daily lives. Caregivers also realized these concerns, and one pointed out:

Caregiver, 56 years (CMIP): Now, I remembered just then, when you said before, potentially, what could negatively affect these people, the users of that [the system] … would maybe be feeling they are going to lose attention as a result.

If care receivers and caregivers perceive that the HBECS can provide them with a feeling of safety and relief, while at the same time decreasing the burden placed on the caregivers, then it is likely that both groups will be motivated to use it in the future. However, these outcomes also depend on device and service characteristics, which in turn directly and indirectly impact HBECS acceptance and use. First, with its sensors enabling detection of various events and its automatic activation, the HBECS allows for monitoring and control of the care receiver. Second, the HBECS should be error-free, which means that users learn to trust the service and never lose confidence about its operation and reliability. Trust can be further strengthened by a clear identification of operation, proper presentation, instructions, and a responsive call center. Third, the use of the HBECS depends on a service design that accommodates the everyday needs, customs, and routines of its users.

While these factors were presented in greater detail in the previous section, we want to stress here that usability becomes relevant only when utility is present. With regard to guaranteed help, the key to perceived usefulness seems to be a call center that can be alerted via a physical emergency button that should be available on the HBECS central unit. Both caregivers and care receivers recognized the critical role and key added value of the call center in providing timely assistance to care receivers. The call center should be responsive and reliable, provide appropriate feedback to the user, and/or inform the caregiver about the care receiver’s condition. Likewise, the HBECS should also provide an automatic alert to caregivers through a push notification in the mobile app.

All these features require that users have a sufficient proficiency in using HBECS equipment installed in their homes and/or on their mobile phones. Its basic technical characteristics, the role of the call center, and the subsequent handling in activating aid (e.g., what happens in emergency cases regarding access to the apartment) have to be clearly presented to them. The setup process and instructions by the technical stuff thus impact user experiences and future use. Hence, manuals should be adapted to match the cognitive, sensory, and memory-processing abilities of care receivers, highlighting the most relevant instructions and illustrations. Preferably during installation, users should be introduced to the HBECS with support from video tutorials and simulations.

Finally, the results indicate that the purchase and maintenance costs of HBECS are important factors, as illustrated by the following excerpt:

Caregiver, 56 years (CMIP): Ah, depends on the price.

Interviewer: Mmm, so, the price…

Caregiver, 56 years (CMIP): Mainly. The determining factor is the price. A need, an urgent need for that, we don’t have at the moment. That could change tomorrow, right? No one knows that. If there was some normal, acceptable price, right then I would decide. ’Cause it is, after all, quite a big addition.

The initial price should be set at an affordable level based on the financial capacities of the care receivers and caregivers. Otherwise, both sides might not be interested in purchasing. In this sense, what is critical from the users’ point of view is the trade-off between costs and perceived value added using HBECS for enhanced safety, security, release of burden, health management, etc. This was particularly true because both groups compared HBECS with technologies and services they already used for care provision. The perceptions of (potential) users are meaningfully shaped by their existing experience with care services and assistive technology, as well as their expectations for their current and future needs.

5. Discussion

The aim of this study was to examine real-life experiences that drive the acceptance and use of market-ready HBECSs in Slovenia, an EU country with low uptake of HBECSs and where elder care is based on familialism. Semi-structured interviews with dyads of care receivers and caregivers revealed a number of original substantive findings and practical implications.

5.1. Substantive findings

In addressing the research question, the study identified four major themes related to post-implementation experiences of market-ready HBECSs: functionalities, impact and expected benefits, social interactions, and barriers to further use. Overall, the results indicate heterogeneous needs and expectations that care receivers and caregivers have toward acceptance and use of HBECSs. Among them, we recognized various design and service features as important facilitators and inhibitors in the purchasing decision. The former converge in users’ necessity for alleviating the fear of not reaching help quickly in an emergency, as they increased their perception of safety and peace of mind. The latter cluster around concerns that the HBECS could potentially reduce contact between caregivers and care receivers. Tellingly, fear of HBECS substituting for human contact, and thus, deteriorating the caregiving relationship, was raised in several interviews.

The four identified domains (see ) enclose several acceptance factors unveiled in prior literature. For instance, we identified care receivers’ properties, such as the need for safety, housing arrangements, technology proficiency, and privacy concerns, that matched the age-specific technology acceptance factors among older adults (Chen & Chan, Citation2011; Liu et al. Citation2016; Peek et al., Citation2014; Thordardottir et al., Citation2019; Tsertsidis et al., Citation2019). Further, our results substantiate the role of contextual factors linked to situational and organizational issues of care within families (Epstein et al., Citation2016; Gaugler et al., Citation2019; Gibson et al., Citation2019; Jaschinski & Ben Allouch, Citation2019; Karlsen et al., Citation2019; Mitchell et al., Citation2020) and to the quality of relationships between caregivers and care receivers (Cook et al., Citation2018; Jaschinski & Ben Allouch, Citation2019; Karlsen et al., Citation2019).

However, the four domains also provide more detailed insights into each group of factors. For instance, they point to the importance of taking into account the specific living arrangements of older adults (e.g., living alone), their relationship with their neighbors, the heterogeneity of family situations, and the seminal role of call centers as not only providing assistance in emergency situations but also emotional support to care receivers via social calls. Further, using a market-ready HBECS in the domestic environment offered a more nuanced overview of the “perceived needs to use” (Peek et al., Citation2014, p. 242; Tsertsidis et al., Citation2019, pp. 329–331). While care receivers mentioned past health-related incidents and related fears, both of which resulted in the need for safety and security, caregivers mentioned their work–life commitments and time constraints, related burdens, and worries, which resulted in the need for peace of mind. Importantly, the participants compared their perceived needs with first-hand experiences of market-ready products. As Peek et al. (Citation2014) suggested, this is an important advantage of post-implementation studies because “older adults mention that they would use technology when they perceive it as useful, although often it is not made clear what constitutes this perceived usefulness” (p. 242). In fact, we found that older adults’ anticipations of HBECS can have different implications in the post-implementation stage, since some of their pre-implementation concerns (e.g., feeling unsafe, obtrusiveness, and fear of becoming dependent) reported in past research (Peek et al., Citation2014) turned into real-life problems or even into positive characteristics or outcomes in this study.

The interrelationships between the factors that emerged from the inductively driven analysis of our dataset also enabled us to propose a novel substantive model of HBECS acceptance and use that represents the key original contribution of this study. While the model is not an exhaustive theoretical framework but rather a display of substantive theory transferable to similar contexts of HBECS adoption, we believe it convincingly explicates the mechanisms that connect the four interrelated domains of HBECS acceptance and use: current and future care receivers’ and caregivers’ needs, context, device and service characteristics, and experienced outcomes. These domains resemble those found in Peek et al.’s (Citation2017) model of technology acquirement by independent living seniors, Jaschinski et al.’s (Citation2021) model of ambient assisted living acceptance, and TAM-related models. However, our model provides additional insights by explicating the multifold relationships among specific factors not only between but also within the identified domains. For instance, acceptance and use of an HBECS depends on its key functionalities (e.g., call center, emergency button) which should be age friendly and error free to contribute to certain positive outcomes of use. In the domain of outcomes, we also demonstrate the intricacies of the interplay between control, trust, perception of safety, and relief. The model also emphasizes the strong role of various contextual factors in explaining how the needs of care receivers and caregivers shape the equipment and service characteristics. The latter, in turn, affects caregivers’ and care receivers’ outcomes of HBECS utilization, where trust in timely help and safety turned out to be the most important experienced outcome. Further, the model explicates various trade-offs between experienced (and not only expected) benefits and costs. For instance, a trade-off was found between the cost of accepting a level of surveillance and breach of privacy for a gain in safety and peace of mind. Similarly, price, which had an important role in further use, was mainly considered a trade-off between service costs and benefits of HBECS usage.

5.2. Practical implications

There are a number of practical implications arising from the substantive findings of this study. These aspects can be useful not only for scholars working on conceptual advances but also for HBECS providers, including those who are part of public social care services and those targeting the rapidly growing consumer market (Stephanidis, Citation2009; Varnai et al., Citation2018; Ward et al., Citation2017).

Most importantly, our results highlight the need to include both caregivers and care receivers in HBECS research. While past work on HBECS largely overlooked informal caregivers (Reeder et al., Citation2013; Vassli & Farshchian, Citation2018), our results show the importance of understanding the role of caregivers through grasping their necessities, preferences, everyday routines, and commitments in elder care. Our research also supports Thordardottir et al.’s (Citation2019) findings about caregivers having a particularly significant role in the process of innovative assistive technology implementation among people with cognitive impairments. Paradoxically, although HBECSs are promoted for vulnerable elderly people living alone, we have discovered that having a close relative who is in a trustworthy and committed relationship with the care receiver is an important condition of HBECS use. The role of the caregiver is also crucial in the decision-making process. While caregivers typically initiate the purchase of an HBECS, the final decision needs to be harmonized and made in agreement with care receivers. This also means that expectations on both ends need to be considered when HBECS providers market e-care services or policy makers design interventions for promoting the uptake of HBECS.

Relatedly, the interviews also shed light on two important elements of their decision making that could be important for HBECS providers. On the one hand, providers should take into account the diversity of stakeholders involved in the adoption and use of HBECSs, such as close relatives, neighbors, physicians, and the call center. In fact, there will often be multiple caregivers (e.g., children and spouse). While these caregivers will be involved in decision making and purchasing to different extents, in-care provision of a well-functioning HBECS should support interaction among them. On the other hand, participants compared HBECS with existing technologies and practices they already employed to identify potential services that could add additional value. In this sense, we suggest that providers focus on developing a HBECS that supports remote nursing care and social calls because these services are currently not available on these platforms.

Of course, care receivers’ and caregivers’ perceived added value of HBECS strongly depends on its usability and service utility. Thus, market-ready HBECSs must be error free, reliable, responsive, trustworthy, and unobtrusive while simultaneously being transparent, easy to use, and customizable, with an age-friendly design and clear instructions and support on how to use it. These distinctive aspects of HBECSs could help developers and providers to focus more systematically on specific facets of user experience to overcome the “poor fit with preference” problem of HBECSs that has been unveiled in prior literature (Tsertsidis et al., Citation2019, p. 329).

While the study was carried out well before the COVID-19 outbreak, our findings gain additional practical importance in the times of stay-at-home measures and physical distancing. Social and physical isolation, loneliness, and depression among older adults has become an increasing problem during the COVID-19 pandemic, as has the remote monitoring of their health and wellbeing (Cuffaro et al., Citation2020; Keeler & Bernstein, Citation2021; Smith et al., Citation2020; Thomas et al., Citation2020). The market-ready HBECSs used in this study could potentially alleviate some of the risks, fears, and caregiver burden associated with living and caring for older adults in the times of an epidemic. In addition, health care providers could combine remote medical monitoring of frail COVID-19 patients with HBECS utilization to support the provision of remote social care that can improve their quality of life during recovery.

5.3. Limitations

Our original findings must be considered in light of the study’s limitations. During the interviews conducted with care receivers and their caregivers, the researchers noticed that participants’ motives for being involved in the intervention study were not related only to a current need to use HBECS but also to other motives. Most caregivers had average- to high-level digital skills and were predominantly men, who represent a smaller group of informal caregivers in Slovenia (Šadl & Hlebec, Citation2018). This may have partially influenced the narrative of the semi-structured interviews, although prior research has shown that men (Olsson et al., Citation2012; Schulz et al., Citation2016; Xiong et al., Citation2020) and digitally skilled relatives (Guisado-Fernández et al., Citation2019; Hassan, Citation2020; National Alliance for Caregiving, Citation2011; Olsson et al., Citation2012; Schulz et al., Citation2016; Sriram et al., Citation2019; Thordardottir et al., Citation2019) are often involved in HBECS uptake within families. The external validity of the results could also have been affected by observing dyads of participants that were in good personal/caring relationships as well as by the rather small sample size, which might have affected the degree of saturation. While all typical functionalities of currently available HBECS were tested, these could be supplemented with additional ones, e.g. social robots or telemedicine treatment, and specific acceptability factors for and outcomes of these additional functionalities could be studied.

Hence, our model certainly warrants further empirical validation and elaboration. A longer testing period would enable care receivers and caregivers to evaluate HBECS equipment and features more holistically. In particular, the call center’s function, which turned out to be of vital importance for end users, could be analyzed in a more informed way. By extending the intervention period, we could also involve more urgent cases, which have been often mentioned as key determinants of perceived usefulness of HBECSs. If participants had encountered more occurrences demanding immediate help and assistance, they would have been able to provide more informative and extensive feedback. A longer intervention—which would result in a routine use of an HBECS—would also enable us to tap additional “domains of knowing” (Mathison, Citation1988, p. 14) where different (and more intimate and sensitive) issues related to experiences with HBECSs could be uncovered by the dyads. Although this study was conducted in 2016, the relevancy of the results can be justified with the fact that no significant evolvements in the HBECS market have occurred in Slovenia over the last 5 years. In fact, one of the tested HBECSs in this study is still the only e-care service that is currently marketed in Slovenia, albeit with some minor technical upgrades to functionalities that have since been introduced. Nevertheless, it would be worthwhile to conduct a study comparing different time-frames and/or a cross-national comparative study in the future, even though such comparative studies are time and resource intensive.

6. Conclusion

The existing research was advanced mainly by investigating post-implementation acceptance and use factors of commercially available HBECSs. This study is one of the first attempts to examine interrelationships between post-implementation acceptance and use factors among dyads of care receivers and their informal caregivers. A clear need to focus on both types of primary users—informal caregivers and care receivers—was demonstrated. Our principal original contribution lies in a proposed inductively developed substantive explanatory model of HBECS acceptance and use. We unveiled a complex mix of interrelated factors within and across key domains, which should all be considered when studying and aiming at (market-ready) HBECS acceptance. Our model provides a sound basis for further conceptual advances. For instance, additional factors from prior literature reviews, such as the characteristics of users (e.g., socioeconomic status, digital skills) and welfare state characteristics (e.g., access to long-term care services) or adding health benefits to the outcomes would be feasible extensions of the model. Our practical implications offer solid underpinnings for HBECS developers, service providers, and policy makers to foster user-driven research and development in the future that would favor aging in place, especially in these uncertain times.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the participants who took part in this study, as well as Peter Pustatičnik and Elena Nikolavčič (Telekom Slovenije) for their useful feedback on an early version of the manuscript. Mojca Šetinc, Anja Tuš, and Otto Gerdina are acknowledged for their valuable assistance in the data collection and analysis. We would also like to thank Mojca Šetinc for her help in finding and describing the features of the three tested home-based e-care services.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Matic Kavčič

Matic Kavčič is an assistant professor of sociology at the Faculty of Health Sciences and Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Ljubljana, Slovenia. His research topics lie in the area of sociology of health and illness, quality of life, care and e-care for the elderly, interprofessional collaboration and user involvement.

Andraž Petrovčič

Andraž Petrovčič is an assistant professor of Social Informatics and a research fellow at the Centre for Social Informatics in the Faculty of Social Sciences at University of Ljubljana, Slovenia. His research interests include mobile usability, age-friendly interaction design, and socio-technical determinants of digital inequalities in later life.

Vesna Dolničar

Vesna Dolničar is an associate professor and a researcher at the University of Ljubljana, Faculty of Social Sciences, Centre for Social Informatics. Her main research topics are acceptability of ICT-supported services and psychosocial outcomes of their use among older people and informal carers in the field of health and social care.

Notes

1 Other participants in the sample were older adults testing mobile and wearable devices—such as smartwatches and smartphone apps—that were designed for individual use (i.e., without informal carers monitoring their activities). For details, refer to Dolničar et al. (Citation2017).

2 In the following text, the elaborated categories and subcategories are presented in italics for easier recognition.

References

- Bowen, G. A. (2006). Grounded theory and sensitizing concepts. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 5(3), 12–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690600500304

- Boyatzis, R. E. (2005). Transforming qualitative information: Thematic analysis and code development. Sage Publications.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Carers UK (2013). Potential for change: Transforming public awareness and demand for health and care technology. Carers UK. https://www.carersuk.org/for-professionals/policy/policy-library/potential-for-change-transforming-public-awareness-and-demand-for-health-and-care-technology

- Carretero, S., Stewart, J., & Centeno, C. (2015). Information and communication technologies for informal carers and paid assistants: Benefits from micro-, meso-, and macro-levels. European Journal of Ageing, 12(2), 163–173. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-015-0333-4

- Chen, K., & Chan, A. H. S. (2011). A review of technology acceptance by older adults. Gerontechnology, 10(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.4017/gt.2011.10.01.006.00

- Cohen, D., & Krajewski, A. (2020). Older adults. In B. Levin & A. Hanson (Eds.), Foundations of behavioral health (pp. 231–252). Springer.

- Cook, E. J., Randhawa, G., Guppy, A., Sharp, C., Barton, G., Bateman, A., & Crawford-White, J. (2018). Exploring factors that impact the decision to use assistive telecare: Perspectives of family care-givers of older people in the United Kingdom. Ageing and Society, 38(9), 1912–1932. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X1700037X

- Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (1998). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Sage Publications.

- Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2011). Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Sage Publications.

- Cuffaro, L., Di Lorenzo, F., Bonavita, S., Tedeschi, G., Leocani, L., & Lavorgna, L. (2020). Dementia care and COVID-19 pandemic: A necessary digital revolution. Neurological Sciences: Official Journal of the Italian Neurological Society and of the Italian Society of Clinical Neurophysiology, 41(8), 1977–1979. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-020-04512-4

- Dahler, A. M., Rasmussen, D. M., & Andersen, P. T. (2016). Meanings and experiences of assistive technologies in everyday lives of older citizens: A meta-interpretive review. Disability and Rehabilitation. Assistive Technology, 11(8), 619–629. https://doi.org/10.3109/17483107.2016.1151950

- Dolničar, V., Petrovčič, A., Šetinc, M., Košir, I., & Kavčič, M. (2017). Understanding acceptance factors for using e-care systems and devices: Insights from a mixed-method intervention study in Slovenia. In J. Zhou & G. Salvendy (Eds.), Human aspects of IT for the aged population: Applications, services and contexts: Third International Conference, ITAP 2017, held as part of HCI International 2017, Vancouver, BC, Canada, July 9–14, 2017, proceedings, part 2 (pp. 362–377). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-58536-9_29

- Doughty, K., & Williams, G. (2016). New models of assessment and prescription of smart assisted living technologies for personalised support of older and disabled people. Journal of Assistive Technologies, 10(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1108/JAT-01-2016-0003

- Epstein, I., Aligato, A., Krimmel, T., & Mihailidis, A. (2016). Older adults’ and caregivers’ perspectives on in-home monitoring technology. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 42(6), 43–50. https://doi.org/10.3928/00989134-20160308-02

- Esping-Andersen, G. (1990). The three worlds of welfare capitalism. Princeton University Press.

- Gaugler, J. E., Zmora, R., Mitchell, L. L., Finlay, J. M., Peterson, C. M., McCarron, H., & Jutkowitz, E. (2019). Six-month effectiveness of remote activity monitoring for persons living with dementia and their family caregivers: An experimental mixed methods study. The Gerontologist, 59(1), 78–89. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gny078

- Gibson, G., Dickinson, C., Brittain, K., & Robinson, L. (2019). Personalisation, customisation and bricolage: How people with dementia and their families make assistive technology work for them. Ageing and Society, 39(11), 2502–2519. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X18000661

- Graneheim, U., & Lundman, B. (2004). Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today, 24(2), 105–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001

- Guisado-Fernández, E., Giunti, G., Mackey, L. M., Blake, C., & Caulfield, B. M. (2019). Factors influencing the adoption of smart health technologies for people with dementia and their informal caregivers: Scoping review and design framework. JMIR Aging, 2(1), e12192. https://doi.org/10.2196/12192

- Hassan, A. Y. I. (2020). Challenges and recommendations for the deployment of information and communication technology solutions for informal caregivers: Scoping review. JMIR Aging, 3(2), e20310. https://doi.org/10.2196/20310

- Hlebec, V., Rakar, T., Dolničar, V., Petrovčič, A., & Filipovič Hrast, M. (2021). Intergenerational solidarity in Slovenia: Key issues. In I. Albert, M. Emirhafizovic, C. N. Shpigelman, & U. Trummer (Eds.), Families and family values in society and culture (pp. 359–380). Information Age Publishing.