?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

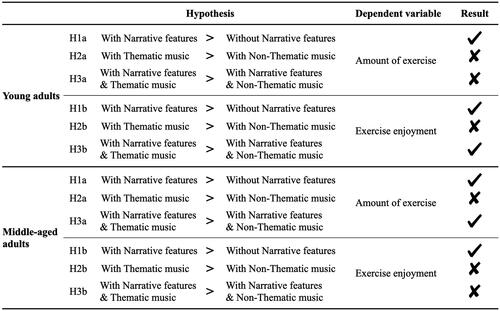

Audio-based exergames are beneficial in that they allow users to exercise in an eyes-free and hands-free environment. In this study, we explored two audio-based exergame elements, narrative features and thematic music, that can impact exercise amount (step count and duration) and exercise enjoyment. We conducted a two-week long between-subjects study with 43 young adults and 43 middle-aged adults using SPORTIFY, an audio-based exergame. Our experimental results showed that (1) Using narrative features had a significant main effect on exercise amount and exercise enjoyment both for young adults and middle-aged adults. (2) Using thematic music had no significant main impact on exercise amount and exercise enjoyment both for young adults and middle-aged adults. (3) A significant interaction effect for exercise amount was observed in middle-aged adults, whereas a significant interaction effect for exercise enjoyment was observed in young adults.

1. Introduction

Exergames, which are games that merge physical exercising with digital gaming (Gao & Mandryk, Citation2011; Laine & Suk, Citation2016; Sinclair, Hingston, & Masek, Citation2007a), can support users to engage in exercise activities (Marshall et al., Citation2016) by providing an enjoyable experience. To fully support such engagement in exercise, most of the exergames are video-based, which use both video and audio to deliver detailed representations of the game theme. Factors that impact the design of video-based exergames have been studied extensively (Laine & Suk, Citation2016; Macvean & Robertson, Citation2013b; Sinclair, Hingston, & Masek, Citation2007b; Xu, Liang, Yu, & Baghaei, Citation2021). However, simply re-applying factors, which were already proven to be effective in video-based exergames, towards audio-only exergames might not lead to similar positive effects in terms of the exercise experience. Visual information is known to dominate other modalities including auditory signals (Posner, Nissen, & Klein, Citation1976). Therefore, we need to examine whether the elements of audio information, which include narratives and music, can also yield positive effects in terms of exercise experience when they are applied separately from those of video-based exergames, which include visual information.

Audio-only exergames have the advantage of providing an eyes-free and hands-free environment (Cowan et al., Citation2017; Luger & Sellen, Citation2016), allowing users to engage in various types of exercises that require full use of eyes or hands. Despite such an advantage unique to audio-only exergames, studies on design elements that focus on audio-based exergames are relatively rare. In an audio-based exergame, audio can provide users with not only exercise instructions but also entertaining elements that help users engage in exercise (Chittaro & Zuliani, Citation2013; Farič et al., Citation2021). Thus, it is important to examine the impact of specific elements of audio-only exergames on exercise experience, which will contribute to suggesting design implications unique to audio-based exergames.

To this end, our study examined two factors, narrative features and thematic characteristics of music. Narrative features are simple independent stories that provide information about characters, goals, and background settings (Narrative, Citationn.d.). Through such information, narrative features directly deliver game themes. Here, a game theme refers to an underlying message or a concept that the game explores. Music with thematic characteristics, i.e. thematic music, is music with a musical component that accompanies game themes to the music, without the explicit narration of the theme (Seidman, Citation1981). To investigate the exercise experience of exergame users, we examined two commonly measured variables (Brandt & Razon, Citation2019; Limperos & Schmierbach, Citation2016; Ẅunsche et al., Citation2021; Yeh, Stone, Churchill, Brymer, & Davids, Citation2017; YorkWilliams et al., Citation2019) that are related to primary goals of exergames (Marshall et al., Citation2016): the amount of exercise and the level of exercise enjoyment. In this paper, the amount of exercise is defined as the step counts and the duration of exercise.

We first explored the effect of narrative features on the amount of exercise and exercise enjoyment. Given that immersive gaming elements, such as narrative features (Chittaro & Zuliani, Citation2013; Lu, Citation2015), promote a user’s autonomy and competence (Bormann & Greitemeyer, Citation2015), we expect using such immersive gaming elements would lead to an increase in the amount of exercise (Kari, Piippo, Frank, Makkonen, & Moilanen, Citation2016). In addition to the amount of exercise, the use of narrative features would also increase the level of exercise enjoyment. Literature showed that using narrative features improves users’ perception of physical activity and reduces the perceived effort of exercising (Chittaro & Zuliani, Citation2013).

We also examined the impact of thematic characteristics of music on the amount of exercise and the level of exercise enjoyment. According to previous video-based studies, exergame players are distracted from feelings of fatigue while listening to game music (Keesing et al., Citation2019; Soltani & Salesi, Citation2013; Yin et al., Citation2021). In addition, according to video-based gameplay studies, music that is consistent with the game theme can evoke positive emotions from players (Klimmt et al., Citation2019; Yim & Graham, Citation2007). However, even without explicit delivery of game themes through dynamic images or narratives, music (e.g., soundtrack) can convey the game themes by autonomously accompanying the imagination of such themes (Seidman, Citation1981). Therefore, thematic music alone can provoke users to envision themselves being in the exergame situation, which may motivate them to exercise. As a result, we hypothesize that players can keep exercising for a longer time, i.e., show an increased amount of exercise, when thematic music is present. Our study also examines whether thematic music can also enhance the level of exercise enjoyment in audio-based exergames where music may have a larger impact without explicit visual cues.

In addition to the two main effects of narrative features and thematic characteristics of music on exergame experiences, we investigated an interaction effect between the two factors. It is shown that music with thematic characteristics supports gameplay by complementing its narrative (Ekman, Citation2014). Specifically, users can visualize backgrounds and characters in their minds while accommodating thematic music as story-like (Maus, Citation1991). As thematic music can play a role in reminding narratives of the game according to video game studies regarding congruence between game music and the game (Jia, Citation2022; Klimmt et al., Citation2019), its effect on exercise experiences will be strengthened when paired with narrative features. We thus hypothesized that a higher amount of exercise and the level of exercise enjoyment will be achieved by narrative features when listening to thematic music than non-thematic music.

Rather than testing the hypotheses in one age group, we examined the above-mentioned effects of narrative features and thematic characteristics of music separately in two different age groups: young adults (18-44 (Erikson & Erikson, Citation1998; Levinson, Citation1986)) and middle-aged adults (45-65 (Erikson & Erikson, Citation1998; Middle age, Citationn.d.)). Those two age groups are known to have different exergame experiences (Graves et al., Citation2010; Xu et al., Citation2021) because the two groups can be differently motivated while engaging in exergames (Subramanian, Dahl, Skjæret Maroni, Vereijken, & Svanæs, Citation2020). Therefore, in this study, we examined the exergame experiences of each of the two age groups by including two specific elements of exergames: narrative features and thematic characteristics of music.

To examine how narrative features and thematic characteristics of music impact the exergame experience of young and middle-aged adults, we conducted an experiment for two weeks using SPORTIFY, an audio-based exergame. Based on the experimental study, our research yields the following three contributions: (1) We provide empirical results showing that the main effect of narrative features was significant on exercise experience for both young and middle-aged adults. (2) We provide supporting evidence for a significant interaction effect between narrative features and thematic music on exercise enjoyment for young adults and on the amount of exercise for middle-aged adults. (3) We present design implications for audio-based exergames, i.e., to apply different design strategies according to the age of target users. Specifically, for young adults, we recommend providing strong initial motivation with narrative features and the opportunity to control the mood and pace of the music. For middle-aged adults, we suggest designing exercises to align with narrative features and include features that can support companionship.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews previous studies on exergames, narrative features, thematic characteristics of music, and exergame experience of different age groups and introduces the hypotheses of this study based on the gap with existing literature. Section 3 introduces the design of SPORTIFY, and section 4 presents our 2 × 2 between-subjects study design to examine the relationship between two elements and exercise experience. The results are reported, discussed, and concluded in sections 5, 6, and 7, respectively.

2. Related works

Our study aims to investigate how two features of an audio-based exergame, i.e., narrative features and thematic characteristics of music, impact the exercise experience of users in an audio-based exergame. In section 2.1, we introduce and examine previous research on exergames with different modalities. The two features, which we investigated in this study, are explored in section 2.2 and section 2.3, respectively. Section 2.4 introduces how previous works explored the exergame experience of two age groups of users: young adults and middle-aged adults. Based on existing literature, in section 2.5, we present six hypotheses that examine the research gap in previous work.

2.1. Exergames with different modalities

Mobile exergames use various modalities such as screen (Goh & Razikin, Citation2015; Gómez-Portes et al., Citation2021; Oyebode, Maurya, & Orji, Citation2020; Uzor & Baillie, Citation2014), voice (Almadhoun, Issa, Abushahla, Al-Qadi, & Issa, Citation2020; Chao, Lucke, Scherer, & Montgomery, Citation2016; Morelli, Foley, Columna, Lieberman, & Folmer, Citation2010), VR (Xu et al., Citation2021), and AR (Geelan et al., Citation2016). Through such modalities that deliver visual, auditory, and tactile information, mobile exergames have been reported to be effective in promoting physical activities (Buttussi & Chittaro, Citation2010; Dutz, Hardy, Knöoll, Göobel, & Steinmetz, Citation2014; Görgü et al., Citation2010; Laine & Sedano, Citation2015; Lindeman et al., Citation2012; Wylie & Coulton, Citation2008). For example, video-based mobile exergames that are based on 2D screen visualization with audio (e.g., Running Othello (Laine & Sedano, Citation2015), Health Defender (Wylie & Coulton, Citation2008), Monster and Gold (Buttussi & Chittaro, Citation2010)) motivate users to move their body by using graphical elements to capture users’ attention. Mobile exergames using AR technology, based on visual, auditory, and tactile modalities, (e.g., Freegaming (Görgü et al., Citation2010), GeoBoids (Lindeman et al., Citation2012), PacStudent (Dutz et al., Citation2014)) aid in increasing user’s physical activity by giving users missions to follow pictures of objects that are augmented by a mobile device. While accomplishing the given missions, users keep walking or running from one target place to another, which results in increased exercise amount (Dutz et al., Citation2014; Görgü et al., Citation2010; Lindeman et al., Citation2012). Despite such benefits, mobile exergames that accompany multiple modalities (e.g., visual, auditory, and tactile) require users to hold a mobile device and keep their eyes on its screen, which can limit the range of physical movement during exercise.

In mobile exergames, delivering information with just audio has several advantages over using multiple modalities. One advantage is that users can exercise in an environment where eyes and hands can be used for exercising (Cowan et al., Citation2017; Luger & Sellen, Citation2016). In an audio-only setting, users do not need to hold or wear devices on the part of their body to do exercise. Furthermore, research on audio-based games showed that audio can be an expressive medium that can communicate very specific information, including conveying an intended game mood (Friberg & Gärdenfors, Citation2004; Roden et al., Citation2007). Despite the potential of audio-based games, audio as a sole medium has not been fully explored. Specifically, knowledge of how each element that constructs audio-based exergames impact exercise experience can help design effective exergames. Thus, to further explore how the exercise experience can be affected by specific audio elements of exergames, our study focused on two factors, i.e., narrative features and thematic characteristics of music.

2.2. Narrative features

Narrative features are used to provide a story to a game, helping users to imagine the virtual world and become immersed in gameplay (Lu, Citation2015; Lu, Thompson, Baranowski, Buday, & Baranowski, Citation2012; Schneider, Lang, Shin, & Bradley, Citation2004). Such immersion can positively impact users’ exercise experience. The following works imply why narrative features in exergames lead to an increase in the amount of exercise. According to Bormann and Greitemeyer (Citation2015), immersion-related game elements such as narrative features induce autonomy and competence. Such feelings can intrinsically motivate users to increase their physical activities (Patrick & Canevello, Citation2011). Kari et al. (Citation2016) showed that using an exercise application with game elements can make users aware of their physical activity and increase exercise motivation as well.

Furthermore, the use of narrative features can positively impact exercise enjoyment (Chittaro & Zuliani, Citation2013; Müller et al., Citation2017). For example, Chittaro and Zuliani (Citation2013) showed that audio storytelling enhances a positive perception of physical activity, making exercise more engaging and enjoyable. Participants reported that by listening to the narratives, they could be distracted from feelings of physical fatigue. In addition, Müller et al. (Citation2017) used an exergame that provides one of four different narratives that matches the player’s emotional responses detected by the system. Two of the four narratives, as intended, were able to induce negative feelings, such as frustration and fear, while the other two narratives induced positive emotions, such as joy and surprise. The results indicate that narrative features, when used in an exergame, can affect users’ enjoyment during gameplay.

However, only a few attempts have been made to adopt narrative features in an audio-based exergame. To the best of our knowledge, there are two cases introducing narrative features into audio-based exergames: Time: Runner (Chittaro & Zuliani, Citation2013) and Zombies, Run! (Farič et al., Citation2021). The first case showed that the audio storytelling technique, one of the narrative features, positively affects users’ perception of physical activity (Chittaro & Zuliani, Citation2013). In this study, participants experienced immersion when they were provided with narration that included escaping from a giant dinosaur. The level of immersion, which increased with the inclusion of narration, was positively correlated with the perception of exercise. The second case is a study on the effect of audio storytelling on increasing exercise engagement, where a user plays a heroic character who is required to accomplish a mission (Farič et al., Citation2021). Running with such imaginary stories freed the player from perceiving physical fatigue. Both cases utilized narrative stories in the exergames to spark imagination and immerse users into gameplay.

2.3. Thematic characteristics of music

In addition to narrative features, several studies have explored the potential role of music in improving the amount of exercise and the level of exercise enjoyment (Gfeller, Citation1988; Komninos, Dunlop, Rowe, Hewitt, & Coull, Citation2015; Wininger & Pargman, Citation2003). Gfeller (Citation1988) showed that musical components such as style and extramusical associations evoked by music were effective in supporting physical activity. Komninos et al. (Citation2015) revealed that when the quality of music while walking was degraded as the physical activity decreased, users tried to increase their walking pace intentionally. Wininger and Pargman (Citation2003) showed that user satisfaction with music is positively correlated with exercise enjoyment.

Given the positive impact of music on exercise amount and enjoyment, researchers have explored what specific musical components would improve the exercise experience. One widely explored component was the tempo of the music, especially the synchronization of music tempo and exercise movements (Keesing et al., Citation2019; Soltani & Salesi, Citation2013; Yin et al., Citation2021). For example, Keesing et al. (Citation2019) revealed that synchronized music decreased perceived exertion effort. Soltani and Salesi (Citation2013) also showed that exergame users who listened to motivational music of which tempo is synchronized to the running pace while playing the exergame felt less tiredness and exercised longer than those who exercised without such music. Yin et al. (Citation2021) revealed that music with the tempo synchronized to users’ movement lowered distress when exercising. The impact of other musical components, such as style (Gfeller, Citation1988), volume (Edworthy & Waring, Citation2006; Hutchinson & Sherman, Citation2014), and rhythm (Atan, Citation2013), on exercise has been also investigated. Specifically, for aerobic workouts, music styles of rock, pop, and new wave music were preferred over classical, religious or ethnic styles. For volume and rhythm, louder and faster music were shown to support optimal exercising in terms of running speed and heart rate.

In addition to the impact of such various musical components, including another musical element that can provide complementary information about the game may have the potential to strengthen the impact of gameplay, which can increase user engagement (Yim & Graham, Citation2007). According to Lilla, Herrlich, Malaka, and Krannich (Citation2012), music that accompanies a certain narrative lowered perceived physical fatigue when exercising. Specifically, such music led participants to imagine movie characters overcoming challenges. Klimmt et al. (Citation2019) emphasized the congruence of a soundtrack with the game. Such congruent music was expected to have a positive effect on video game enjoyment, mediated by intensified emotions. For example, the “historical” soundtrack with an adventure game and the “ambient” soundtrack with a horror game induced a positive feeling, which was relevant to an increase in game enjoyment. These studies showed that music that matches the game theme can have a positive effect on the gaming experience.

2.4. Exergame experience of different age groups

Since exercise ability differs by physical age, it is likely that exergame experience can differ by users’ age, as evidenced by several studies (Graves et al., Citation2010; Mullins, Tessmer, McCarroll, & Peppel, Citation2012; Xu et al., Citation2021). Graves et al. (Citation2010) examined how the physiological cost and enjoyment of doing aerobic exercises with Wii Fit were different in the following age groups of users: 11-17, 21-38, and 45-70. Older adults (45-70) consumed less amount of energy but showed a higher level of enjoyment than the two younger groups. Mullins et al. (Citation2012) compared the physical activity level of young adults (21.4 years old on average) and older adults (58.0 years old on average) while using Wii Fit exergames. In both groups, playing the exergame successfully induced a moderate amount of exercise. However, there was a difference between the two groups in that older participants’ perceived effort in physical activity was higher than that of younger participants. Xu et al. (Citation2021) conducted research on how three factors’ users’ age, the uncertainty that users feel in gameplay, and display type’ impact on VR exergame experience. The study results showed that young adults tended to show higher game performance and feel more positive emotions than middle-aged. On the other hand, young adults were likely to feel negative emotions more easily than middle-aged adults.

The aforementioned works showed that the exergame experience could differ by the age of users (Graves et al., Citation2010; Mullins et al., Citation2012; Xu et al., Citation2021). Several pieces of literature implied that such difference is attributable to the different motivations for using exergames (Kappen, Mirza-Babaei, & Nacke, Citation2017; Subramanian et al., Citation2020). Kappen et al. (Citation2017) figured out that four age groups (18-29, 30-49, 50-64, and over 65) had different levels of motivation to participate in technology-assisted physical activity. Those who are over 65 showed the strongest tendency to exercise for health, followed by those who are 50-64, 30-49, and 18-29. Subramanian et al. (Citation2020) analyzed how young adults and middle-aged adults were differently motivated in an exergame. The younger adults and the older adults were intrinsically motivated, respectively, by game challenges and the joy of playing. In terms of extrinsic motivation, the younger adults and the older adults were respectively motivated by in-game rewards and perceived health effects of playing.

2.5. Research gap and hypotheses

Based on our investigation of previous works in section 2.2 that adopted narrative features in an audio-based exergame, none of the cases reported quantitative evidence for the positive effects of narrative features on the amount of exercise. In addition, the level of exercise enjoyment was measured only during short exercise sessions. Therefore, in this study, we examined the impact of narrative features in an audio-based exergame using both quantitative and qualitative analysis by conducting a two-week user experiment.

H1a: Participants in narrative conditions will achieve a higher amount of exercise than those in non-narrative conditions.

H1b: Participants in narrative conditions will experience a higher level of exercise enjoyment than those in non-narrative conditions.

Concerning the thematic characteristics of music, one of the musical components of game music, related works explored in section 2.3 showed that music that represents the game theme had a positive effect on the gaming experience. Such a positive effect can also be expected in exergame contexts but has not been fully explored yet. Therefore, in addition to narrative features, we suggest exploring music elements, i.e., thematic characteristics of music, which can contribute to the exergame experience. In this study, we examined the impact of such elements on exercise experience by comparing thematic music and non-thematic music conditions.

H2a: Participants in thematic music conditions will achieve a higher amount of exercise than those in non-thematic music conditions.

H2b: Participants in thematic music conditions will experience a higher level of exercise enjoyment than those in non-thematic music conditions.

Findings in prior research showed that incorporating music that effectively conveys game narratives can enhance the video gaming experience by intensifying emotions (Jia, Citation2022; Klimmt et al., Citation2019). Based on these findings, we hypothesized that music that accompanies game messages and themes can potentially have an impact that extends to exergame contexts when narratives are employed. Therefore, to examine such impact, the following hypotheses (H3a, H3b) were investigated.

H3a: With narrative features, participants will achieve a higher amount of exercise when listening to thematic music than when listening to non-thematic music.

H3b: With narrative features, participants will achieve a higher level of enjoyment when listening to thematic music than when listening to non-thematic music.

According to the literature reviewed in section 2.4, there were differences in the game experience and motivation for exercise when participants were divided into various groups by age (Graves et al., Citation2010; Kappen et al., Citation2017; Mullins et al., Citation2012; Subramanian et al., Citation2020; Xu et al., Citation2021). However, most of these studies put less emphasis on how the specific exergame elements can impact the exercise experiences of each age group. In our study, we investigated how narrative features and the thematic characteristics of music can have an impact on each of two different age groups: young adults and middle-aged adults.

3. Design of SPORTIFY

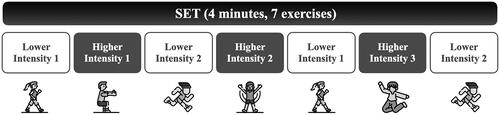

SPORTIFY is an audio-based exercising application that guides players through five sets of various cardio and compound exercises. Each set is four minutes in length and presents seven types of exercises that have lower and higher intensity levels, presented in alternating order. shows a sample set containing seven exercises. The types of exercise were drawn from the list of cardio and compound exercises recommended by the Korea Sports Promotion Foundation (indoor health exercises, Korea Sports Promotion Foundation, Citation2021) and the Queensland Government Department of Health (Exercises, Queensland Government Department of Health, 2021). The two lower-intensity exercises used in SPORTIFY are walking and running in place, and the five higher-intensity exercises are burpee, squat, jumping jack, touch floor squat, and jumping. Since young adults and middle-aged adults have different physical capacities, the difficulty of higher-intensity exercises was lowered for middle-aged adults. For example, middle-aged adults were asked to use a chair when doing squats or burpees. Such modifications were based on exercise guidelines for older adults (Active Seniors Health Centre, Citation2012; National Institute on Aging, Citation2012; The New York Times, Citation2020).

Figure 1. One set of exercises is four minutes in length and contains seven exercises, with lower and higher intensity exercises presented in alternating order.

The process for a player to exercise with SPORTIFY is as follows: To enable SPORTIFY, which is implemented with DialogFlowFootnote1, the player first calls Google Assistant and then says, “Talk to SPORTIFY”. SPORTIFY is then activated and presents a player with five sets of exercises via voice instructions. As completing all five sets could be challenging to some players, after each set, SPORTIFY gives them a choice to end the exercise by saying, “Would you like to continue exercising or stop and record the number of steps?”.

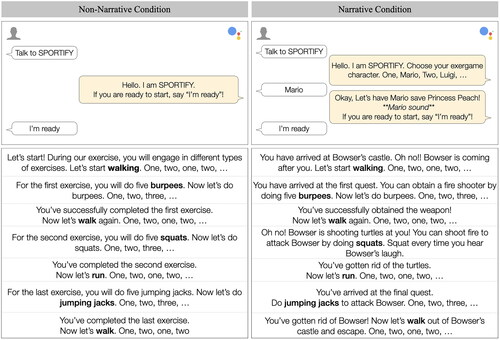

We implemented four different versions of SPORTIFY using two elements, narrative features and thematic music: Narrative features and Thematic music (N-T), Narrative features and Non-Thematic music (N-NonT), Non-Narrative features and Thematic music (NonN-T), and Non-Narrative features and Non-Thematic music (NonN-NonT). The video clip of exercising with each of the four versions of SPORTIFY is available as supplemental material.

3.1. Element 1: Narrative features

To explore the effect of narrative features, we implemented narrative aspects by adopting game synopses from Super Mario Bros. Although using an entirely novel narrative, rather than using Super Mario Bros, would eliminate the potential effect of familiarity, we used Super Mario Bros since the theme of Super Mario Bros is suitable to apply to an exercise program focused on cardio and compound actions. The theme of Super Mario Bros is to save the princess from villains via continuous running and jumping actions. While the users imagine themselves being a hero who attacks a villain and rescues a princess, they can be encouraged to engage in physical movements, as game users are known to identify themselves as virtual characters while engaging in gameplay (Hefner, Klimmt, & Vorderer, Citation2007; Klimmt, Hartmann, & Frey, Citation2007; Li, Liau, & Khoo, Citation2013; Murphy, Frank, Chatterjee, & Baezconde-Garbanati, Citation2013). Thus, we used synopses from Super Mario Bros and provided matching instructions in narrative conditions. presents example instructions in non-narrative conditions and narrative conditions for easy comparison between the two conditions. To control for aspects other than narrative features, we fixed the length and types of exercises across the non-narrative and narrative conditions.

In non-narrative conditions, participants were just given instructions on the exercise without any background settings, characters, or goals. On the other hand, in the narrative conditions, participants were asked to select characters and corresponding goals, and background settings were provided accordingly. Note that for each exercise instruction, we selected the exercises which fit the narrative features of that set. For example, in a scene where a character should attack Bowser, SPORTIFY asks a player to do jumping jacks as an attacking tool, and the instruction states, “Let’s do jumping jacks to attack Bowser”. When a player starts exercising in the narrative conditions, the player first selects a character from Super Mario Bros. There are four possible characters, i.e., Mario, Luigi, Yoshi, and Toad. Then, SPORTIFY introduces a goal that should be achieved by the selected character. For example, the goal of playing as Mario would be to save Princess Peach. SPORTIFY then presents a background setting that is related to the character and goal. For example, the character is ordered to escape Bowser’s Castle or avoid sharks underwater. The five background settings that are used in SPORTIFY are presented in .

Table 1. Five background settings and corresponding thematic music.

3.2. Element 2: Thematic music

To examine the impact of thematic characteristics of music, we compared two types of music: thematic music and non-thematic music. For thematic music, we selected five songs from the soundtrack of Super Mario BrosFootnote2. As shown in , each of the five songs was chosen to match the game themes with five different background settings, each of which consists of a villain, location, and event. For non-thematic music, we selected songs from royalty-free music websitesFootnote3. To control for aspects other than thematic characteristics of music, non-thematic music was selected to have similar average BPM, average amplitude, and mood, which were shown to be influential musical factors when doing exercises (Gfeller, Citation1988), to corresponding thematic music. The process of choosing non-thematic music is as follows: (1) BPM: We selected thirty workout songs that have an average BPM with ± 5.7bpm difference with the corresponding thematic music. (2) Amplitude: From these 150 songs, we selected songs that have an average amplitude with ± 0.05 dB difference with the corresponding thematic music. The average amplitude and amplitude shape were drawn using LibrosaFootnote4 Python package. As a result, ten songs for each of the five thematic music were selected as candidates. (3) Mood: Fifteen independent raters voted for one out of ten songs that has the most similar mood to each corresponding thematic music and the song with the most vote was selected as non-thematic music.

4. Method

4.1. Participants

Upon approval from the Institutional Review Board at Seoul National University (IRB No. 2207/003-003), we recruited a total of 86 participants via Google Forms. The participants were recruited from seven different active online communities. Participants from two different age groups were recruited: 43 young adults aged 18 to 28 (mean age = 25.4, sd = 3.93, 13 male) and 43 middle-aged adults aged 43 to 61 (mean age = 49.7, sd = 6.25, 11 male). The proportions of gender were consistent across all experimental conditions and age groups. All the participants had the physical capacity to do cardio and compound exercises. In addition, all participants are literate, own smartphones, and live in metropolitan areas. The participants were randomly assigned to three experimental groups (N-T, NonN-T, N-NonT) and one control group (NonN-NonT). Per condition, the following number of participants was assigned: for young adults, 12 in N-T, 11 in NonN-T, 10 in N-NonT, 10 in NonN-NonT, for middle-aged adults, 10 in N-T, 10 in NonN-T, 12 in N-NonT, 11 in NonN-NonT. Across the four conditions, there was no statistical difference (F(3, 39) = 0.37, p = 0.77 for young adults; F(3, 39) = 0.32, p = 0.81 for middle-aged adults) in the average number of workouts per week prior to the experiment. In addition, we conducted a statistical test to check that there is no difference in the four conditions in terms of Super Mario Bros familiarity prior to the experiment. The chi-square test results verified that there was no statistical difference ( = 0.84, p = 0.84 for young adults;

= 0.65, p = 0.88 for middle-aged adults) among the four conditions in terms of recognition of Super Mario Bros prior to the experiment. Detailed descriptive statistics on demographic information can be found in . We provided a total of $80 to each participant who participated in the study for two weeks. The rewards consist of Mi Band and gift cards.

4.2. Measurement

To investigate the effect of narrative features and thematic characteristics of music on exercise experience, two variables were studied: 1) the amount of exercise and 2) exercise enjoyment. The first variable, the amount of exercise, was measured in terms of step count and duration per exercise. For step count, participants reported the number of steps recorded on the Mi BandFootnote5, a smartwatch which is known to accurately measure step count in free-living conditions (de la Casa Pérez et al., Citation2022), at the end of each exercise. Due to supply issues, Mi Band 3 was provided to young adults and Mi Band 7 to middle-aged adults. The step count was measured using treadmill mode in Mi Band 3 and indoor walking mode in Mi Band 7. Although each mode is titled differently, they both accurately measure the total number of steps during exercise. In addition to step count, the duration of the exercise was measured using a log recorded in DialogFlowFootnote6, which contains conversation history between agents and participants in natural language. We calculated the duration of exercise as the interval between the time when participants said, “I am ready to exercise” and the time when participants said, “Record the number of steps”.

The second variable, exercise enjoyment, was measured with the Korean version (Sungwoon Kim & Jingoo Citation2002) of PACES (Physical Activity Enjoyment Scale) (Kendzierski & DeCarlo, Citation1991). PACES is a validated instrument that measures positive effects related to physical activities. This five-point Likert scale questionnaire consists of 16 questions and yields a total score between 16 and 80 points. All 16 questions start with the phrase “When I am physically active,…” and consist of the following phrases that complete a sentence. Sample following phrases are “My body feels good” and “I feel as though I would rather be doing something else”.

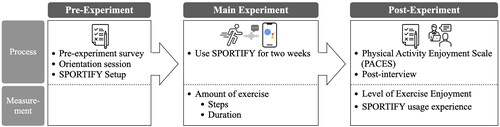

4.3. Procedure

The experiment consisted of the pre-experiment process, the main experiment, and the post-experiment process for both age groups, as shown in . In the pre-experiment process, participants responded to an online survey that gathered demographic information (e.g., age, gender, the number of workouts per week, recognition of Super Mario Bros soundtrack) via Google Forms. We then conducted an orientation session to provide participants with guidance on the tasks they needed to perform for two weeks. We also shared manuals for setting up SPORTIFY and a demo video of the exercises in SPORTIFY so that each participant can do the same movement for each exercise. During the main experiment, participants used SPORTIFY for two weeks. They were asked to use SPORTIFY freely and report step counts after every usage of SPORTIFY.

In the post-experiment process, participants responded to PACES as a post-hoc online survey via Google Forms. In addition, we conducted a 30-minute remote post-interview to collect detailed data on participants’ experience of using SPORTIFY during the main experiment. The post-interview consisted of three themes, totaling eight questions: (1) The first theme of the interview examined how narrative features and thematic music impacted the exercise experience in terms of the amount of exercise and exercise enjoyment. Regarding the first theme, we asked two questions according to the condition to which the participant was assigned. For example, participants in the N-T condition were asked, “Would exercising as a game character help you exercise more/make exercise more enjoyable?” and “Would the background music of SPORTIFY help you exercise more/make it more enjoyable?”. (2) The second theme was regarding usability. We included three questions in the second theme: “Was the exercise easy or difficult?”, “Is there anything on SPORTIFY that made you want to exercise more?”, “Is there something in SPORTIFY that made you uncomfortable?”. (3) The third theme was about behavioral or physical change, and the following three questions were asked: “Comparing the amount of exercise before and after using SPORTIFY, was there any difference?”, “Have you started any new workouts after participating in the experiment?”, and “Do you want to continue using SPORTIFY for exercising after the experiment?”.

4.4. Analysis

The goal of our research is to examine the effectiveness of narrative features and thematic music in an audio-based exergame. We measured the amount of exercise and the level of exercise enjoyment for two different age groups: young adults and middle-aged adults. For quantitative analysis, we used two-way ANOVA to test each hypothesis for both age groups, respectively. Prior to conducting two-way ANOVA, we checked whether assumptions for two-way ANOVA were met. The assumption for normal residuals was examined through the Shapiro-Wilk test, and the results confirmed that the residuals are normally distributed for all hypotheses, with the p-value not being less than the significance level of 0.05. In addition, the assumption for an equal variance for Levene’s test was satisfied, with the p-value not being less than 0.05. Detailed testing results can be found in .

For qualitative analysis, data from the post-interview was analyzed using an iterative open coding method (Corbin & Strauss, Citation2014). Two coders transcribed and analyzed 43 hours of interview recordings, which consisted of 30 minutes for each of the 86 participants. First, the coders independently coded all the transcripts line-by-line and created initial categories using an inductive approach. Next, the coders merged similar codes and formed 28 higher-level categories, such as “Body change after the experiment”, “Desire to keep using SPORTIFY”, and “Narrative features inducing imagination”. Subsequently, in the next iteration of open coding, these codes and categories were applied to the transcripts and used for qualitative analysis with regard to each hypothesis. Cohen’s Kappa coefficient (McHugh, Citation2012) was calculated to measure inter-coder reliability. An agreement level of 0.81 was reached, suggesting a good agreement between the two coders.

5. Result

5.1. Narrative features

Hypothesis H1a was satisfied for both young adults and middle-aged adults. We observed a significant main effect of narrative features for the amount of exercise, i.e., young adults (steps F(1, 39) = 5.96, p = 0.02*, = 0.13; duration F(1, 39) = 5.76, p = 0.02*,

= 0.13) and middle-aged adults (steps F(1, 39) = 5.96, p = 0.02*,

= 0.13; duration F(1, 39) = 9.03, p = 0.004**,

= 0.19). shows the two-way ANOVA test results on the main effect of narrative features. In accordance with the quantitative analysis, we found evidence in favor of the effect of narrative features on the amount of exercise during the post-interview with both young and middle-aged adults in the narrative conditions.

Table 2. Two-way ANOVA test result for H1a and H1b: Main effect of narrative features.

“Before the experiment, I was stressed about the fact that I didn’t exercise. But as I exercised by following the story of the game, I started exercising more. Since exercising, when I got up in the morning, I felt very refreshed and happy.” (p.N-T_20, YA)

“Because there is a storyline and an agent who guides me through vocal instructions, I got more motivated to exercise. I spent more time exercising than when I was exercising by myself.” (p.N-T_8, MA)

On the other hand, young and middle-aged adults in the conditions without narrative features reported that the amount of exercise did not increase significantly after using SPORTIFY.

“The exercise program was a bit simple. It felt like the instruction was repetitive, and there was really no need for it. If there was a more varied version of the instructions, I think I could have done more exercise.” (p.NonN-T_9, YA)

“The exercise instruction was monotonous, so I didn’t use it a lot. I did not exercise much before the experiment, and the amount of exercise did not increase (after using SPORTIFY).” (p.NonN-NonT_13, MA)

As hypothesized in H1b, there was a significant main effect of narrative features on exercise enjoyment for both young adults (F(1, 39) = 4.82, p = 0.03*, = 0.12), and middle-aged adults (F(1, 39) = 16, p = 0.0002***,

= 0.29). Young adults and middle-aged adults in the conditions with narrative features also commented on how narrative features affect the level of exercise enjoyment positively in the post-interview.

“It was fun. I felt like I became a character inside the game clearing quests.” (p.N-T_10, YA)

“Exercising with a character helped a lot and made the exercise more enjoyable because I could imagine the scenario of the game.” (p.N-NonT_2, MA)

On the other hand, young and middle-aged adults in the conditions without narrative features commented that they did not enjoy exercising with SPORTIFY because of the instruction, which was a simple command stating the type of exercise.

“It was boring because there were only serious instructions for the exercise, and it felt like someone was making me do an exercise which I didn’t want to do. I wish the content were more colorful.” (p.NonN-T_16, YA)

“Compared to other audio-based exercise programs I’ve used before, the instructions were a bit boring. I think it would be more fun if there were a context like Zombies, Run!.” (p.NonN-NonT_11, MA)

In addition to the main effect of narrative features, we observed an interesting trend regarding the continued use of SPORTIFY. Although both age groups in the narrative conditions enjoyed using SPORTIFY during the experiment, they had different plans for continued usage. Specifically, young adults felt that narrative features become repetitive as their initial impact wears off and showed interest in starting a new type of exercise rather than continuing to use SPORTIFY.

“At first, I thought that exercising while playing a game was ground-breaking, but in the end, I felt the contents were repetitive. So it was meaningful only at the beginning, and as I went on, I didn’t really care about the story… After the experiment, I enrolled in a ballet class. I think SPORTIFY helped me get a jump start on exercising, which is what I always wanted to do.” (p.N-T_8, YA)

Such disinterest in the continued use of SPORTIFY was observed although the young adults commented on the positive exercising impact, including increased time spent on exercising. On the other hand, middle-aged adults were more excited about the positive impacts regarding exercise. Unlike young adults, middle-aged adults preferred to keep exercising with SPORTIFY.

“At first, I thought SPORTIFY might not be helpful for exercising. However, as I followed the action of the main character, being chased by villains that changed by the character I chose… it actually helped me a lot in losing weight. So even after this experiment is over, I would like to keep using SPORTIFY.” (p.N-T_10, MA)

“SPORTIFY gives instructions such as “if you do running or burpees, you will reach the goal”… and after using it, I feel refreshed and can digest better. It actually helped with my health, so I want to keep using it.” (p.N-T_8, MA)

In summary, regarding narrative features, our data analysis supported H1a and H1b which showed a positive impact of narrative features on the two variables measuring exergame experience. Furthermore, a different continued usage preference was observed between young and middle-aged adults.

5.2. Thematic music

Contrary to hypothesis H2a, both young and middle-aged adults did not show a significant main effect, i.e., young adults (steps F(1, 39) = 2.7, p = 0.1, = 0.07; duration F(1, 39) = 3.16, p = 0.08,

= 0.07) and middle-aged adults (steps F(1, 39) = 3.06, p = 0.08,

= 0.07; duration F(1, 39) = 3.23, p = 0.08,

= 0.08). We also did not observe support for H2b in each of the young (F(1, 39) = 0.03, p = 0.87,

= 0.00) and middle-aged adults (F(1, 39) = 1, p = 0.32,

= 0.03). shows the two-way ANOVA test results on the main effect of thematic music. As with the quantitative analysis, the qualitative analysis also did not show support for hypotheses H2a and H2b.

Table 3. Two-way ANOVA test result for H2a and H2b: Main effect of thematic music.

“Listening to similar game-like music over and over again made exercising too monotonous.” (p.NonN-T_22, YA)

“Listening repeatedly to the background music that is not my type of exercise music made exercising boring.” (p.NonN-NonT_34, YA)

From the post-experiment interview, we found other audio elements that might have influenced the exercising experience rather than the thematic characteristics of music; pace and mood for young adults and counting in the background for middle-aged adults. In the case of young adults, the demand for fast-paced music and vigorous music was high.

“I would enjoy the exercise more if the background music was more cheerful and had a stronger beat.” (p.NonN-T_14, YA)

“I want to control the speed of music to work out at a faster tempo.” (p.NonN-T_7, YA)

Another unexpected finding was the positive effect of background counting for middle-aged adults. The middle-aged adults mentioned that background counting is useful in that it provides a sense of encouragement and companionship.

“Rather than the background music, “one-two-one-two” sounds were more fun.” (p.NonN-T_17, MA)

“The counting was absolutely helpful. When SPORTIFY said ’one-two-one-two,’ I felt like someone was helping my workout.” (p.N-T_6, MA)

In summary, regarding thematic music, our data analysis did not show support for hypotheses 2a and 2b, which hypothesized a positive impact of thematic music on the two variables measuring exergame experience. Instead, alternative potential audio features to improve exergame experiences were suggested for each age group.

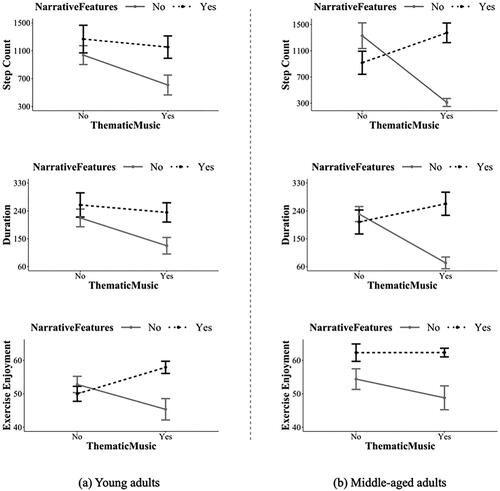

5.3. Interaction effect

shows the two-way ANOVA test results on the interaction effect. In addition, we also provided a visualization of the interaction effect in . Our data did not support H3a for young adults as there was no statistically significant interaction between the effect of narrative features and thematic music in terms of the amount of exercise (steps F(1, 39) = 0.95, p = 0.33, = 0.02; duration F(1, 39) = 1.08, p = 0.3,

= 0.03). On the other hand, H3a for middle-aged adults was supported (steps F(1, 39) = 23.58, p = 1.97e-05***,

= 0.38; duration F(1, 39) = 28.14, p = 4.76e-06***,

= 0.42). In this regard, middle-aged adults in the N-T group stated that the congruence of narrative features and thematic music encouraged them to exercise.

Table 4. Two-way ANOVA test result for H3a and H3b: Interaction effect between narrative features and thematic music.

“The different themes and music for each set went well together. I was told to walk fast in a situation where I had to run away from the villain, and as the music gets faster, I was encouraged to keep exercising.” (p.N-T_35, MA)

As hypothesized in H3b, for young adults, there was a significant interaction between the effect of narrative features and thematic music in terms of exercise enjoyment (F(1, 39) = 9.65, p = 0.003**, = 0.2). Regarding this result, young adults reported that they enjoyed exercising when they felt thematic music was consistent with narrative features.

“I was delighted when the music suited the story. For example, a spooky song came out when the theme was about a haunted house. So I could be more engaged in the exercise and was able to enjoy it more.” (p.N-T_59, YA)

On the other hand, young adults in the condition with narrative features and without thematic music reported a dissonance between the storyline and non-thematic music.

“I felt a separation between the music and the instructions, which made exercising not exciting. There is music that I expect when I hear the story of the game, but the music I listened to wasn’t what I expected.” (p.N-NonT_21, YA)

Unlike in the young adults, H3b for middle-aged adults was rejected (F(1, 39) = 1.07, p = 0.31, = 0.03). Thus, we did not observe an interaction between the effect of narrative features and thematic music in terms of exercise enjoyment for middle-aged adults. As visualized in a black dashed line in the third graph of , when narrative features are presented, the enjoyment level is high in both non-thematic (m = 62.3, sd = 4.47) and thematic (m = 62.3, sd = 7.22) conditions.

6. Discussion

In the subsections that follow, we provide insights into our experimental results, which are summarized in . Specifically, interview data suggested that although a significant main effect for narrative features and a non-significant main effect for thematic music were observed in both age groups, the reasons behind each effect may differ by age group.

6.1. Narrative features

The positive impact of narrative features on the exergame experience was supported by both qualitative and quantitative data, expanding previous findings that investigated the effect of narrative features (Chittaro & Zuliani, Citation2013; Farič et al., Citation2021) in an audiovisual context with a diverse range of participants to unexplored settings: (1) in an audio-only environment and (2) for two age groups. One possible source for such a positive impact may be from the “presence” in the game world that was experienced by the participants who exercised with the narrative features. Presence is defined as a sense of being within the game world and is widely used to make the gameplay experience more realistic (Ryan, Rigby, & Przybylski, Citation2006). According to Ho, Lwin, Sng, and Yee (Citation2017), as exergame users exercise along with game stories, they experience presence, which in turn results in more exercise engagement and higher positive attitudes towards gameplay. Based on such results, we provide findings on the positive impacts of feeling a presence through narrative features from the perspective of two specific measures: (1) increasing the amount of exercise and (2) enhancing exercise enjoyment.

First, for increasing the amount of exercise, which was examined in hypothesis H1a, we observed that compared to participants in non-narrative conditions, participants in narrative conditions did significantly more workouts by following the storyline. Existing research reported that in exergames where various modalities were used, physical activity could increase as users feel a higher level of presence through narrative features (Baranowski, Maddison, Maloney, Medina Jr, & Simons, Citation2014; Farič et al., Citation2021; Mellecker, Lyons, & Baranowski, Citation2013). The evidence from our experiment extends the previous research results in that the positive effect of narrative features was observed in audio-only gaming environments. Secondly, for enhancing exercise enjoyment which was examined in hypothesis H1b, we could observe that participants in narrative conditions enjoyed exercising by imagining themselves being game characters. On the other hand, participants in non-narrative conditions reported that repeatedly listening to serious instructions made exercising tedious. This finding expands prior research that investigated the positive relationship between feeling presence through narrative features and exercise enjoyment in the context of exergames in multiple modalities (Ho et al., Citation2017; Mellecker et al., Citation2013; Schwarz et al., Citation2021), providing additional evidence from the auditory modality.

Interestingly, in our study, both age groups expressed a desire to exercise continuously after the experiment. Specifically, young adults preferred to start new exercises, whereas middle-aged adults preferred to keep using SPORTIFY. One possible reason for such different responses is that each age group reacted differently to the novelty effect of the game, in this context with respect to the narrative features. The novelty effect of a game refers to the initial interest that players experience when they encounter a new game (Koch, von Luck, Schwarzer, & Draheim, Citation2018). Such an effect has been reported to wear off user’s interest in exergames as users become more familiar with the game, and in turn reduce effectiveness in facilitating exercises (Lin, Mamykina, Lindtner, Delajoux, & Strub, Citation2006; Macvean & Robertson, Citation2013a; Poole et al., Citation2011). In the present study, young adults wanted to try different exercises after the experiment, which may be due to the fading novelty effect of SPORTIFY’s narrative features. In contrast, middle-aged adults reported continued plans for using SPORTIFY, instead of switching to a new type of exercise. Our results suggest that the novelty effect of narrative features may still exist after two weeks of the experiment for middle-aged adults. In addition, the participants in the middle-aged group were excited about the positive exercising result, which was listed as additional reasons for continued use of SPORTIFY.

Given that our experimental results showed how including narrative features encourages users to remain physically active while using exergame, we present design guidelines to consider when designing narrative features for each age group. First, to encourage young adults to continue exercising, fostering motivation at first to enjoy exercise itself is important. This is based on our observation that although narrative features’ initial impact diminished over time, the young adult participants reported that they were motivated enough to continue exercising on a different platform. Secondly, to help middle-aged adults keep using exergaming, we suggest designing exercises to align with the characters, goals, and background settings. This is supported by our experimental evidence that a strong connection between narrative features and corresponding exercises can have middle-aged adults stay engaged in the exergame for a longer period. Specifically, they were interested in following various motions that were delivered through the characters and quests.

6.2. Thematic music

For both young adults and middle-aged adults, thematic characteristics of music did not have a significant impact on the amount of exercise and exercise enjoyment. Based on the literature (Klimmt et al., Citation2019; Lilla et al., Citation2012) which identified the positive impact of game music on game enjoyment, we expected that the music that reminds listeners of the theme of the exergame will positively impact exergame experiences for both young and middle-aged adults, as hypothesized in H2a and H2b. However, such a positive effect was not observed in the exergame context, with both young and middle adults in the thematic and non-thematic conditions not showing a statistical difference in terms of the amount of exercise and exercise enjoyment. Instead, we discovered alternative audio-related features that might have impacted exercise experiences for each age group: mood and pace for young adults and counting for middle-aged adults.

For young adults, the qualitative interview results showed that the pace and mood of music might have had an impact on the exercise experience. However, since we controlled for audio features that might affect young adults, including mood and pace, an insignificant difference might have been observed between conditions. Therefore, based on our study data, examining the impact of other audio-related features other than thematic aspects of music, such as providing young adults with opportunities to control the mood and pace of the music, would be an interesting future study to pursue.

For middle-aged adults, counting in the background, such as “One, two, one, two”, was unexpectedly reported to be influential. SPORTIFY provided counting as a background sound across all four conditions in order to encourage users to exercise. Such background counting could have been beneficial to exercise experiences due to two possible reasons. Firstly, constant rhythm within the background counting might have improved users’ movement. Existing literature that examined the effect of music on exercise reported that constant rhythm in music might improve the regularity of movement (Kravitz, Citation1994). Furthermore, instructing users to synchronize the pace of their movements to the constant rhythm, which is presented with auditory cues, is known to improve walking (Mendonca, Oliveira, Fontes, & Santos, Citation2014). In this regard, presenting counting via voice instruction in the background can play a potential role in keeping users in a constant rhythm. Therefore, such instruction might have supported users to exercise at a regular pace, which may lead to an improvement in the exercise experience that we observed in our experiment. Secondly, in addition to the effect of regularity background counting might have induced the feeling of companionship. Middle-aged participants mentioned the positive social impact of counting. For example, participants said that listening to the counting helped them feel like they were working out with a companion. Our middle-aged participants also showed a need for adding friends or exercising in a group. One possible future study idea would be to examine the impact of features that relate to social interaction in audio-based exergames.

6.3. Interaction effect

Although the main effect of the thematic characteristics of music was not significant, a few significant interaction effects were observed when paired with narrative features. Regarding the amount of exercise, as shown in the testing results of H3a, the interaction was significant only for middle-aged adults and not for young adults. In contrast, concerning the level of exercise enjoyment, as reported in H3b from the result section, a significant interaction effect was observed only for young adults and not for middle-aged adults. Below we discuss possible explanations for such different interaction effects on the two age groups.

A possible explanation for why middle-aged adults who listened to thematic music exercised more with narrative features is creating an exercising environment with a strong connection among music, narratives, and exercises. Middle-aged adults reported that they experienced physical improvement from following the exercise movements that correspond with narrative features, such as doing a jump when the narrative says there are obstacles on the floor. The connection between the movements and narrative features could be strengthened by thematic music, based on the middle-aged adults’ comments that thematic music was well harmonized with narrative features. On the other hand, for young adults, we observed that the effect of thematic music was minimal regardless of narrative features. Such a minimal effect of thematic music may be attributed to young adults preferring aspects of music that we controlled, such as mood and pace, rather than the presence of a theme. As a future study, it would be interesting to examine the interaction effect between different aspects of music that can affect young adults and narrative features.

For young adults, participants who listened to thematic music with narrative features showed a higher level of exercise enjoyment than those who listened to thematic music alone. Our qualitative analyses of young adults indicated that their gameplay experiences were more enjoyable when music that matched narrative features was presented. Taking our study results with findings of prior research regarding congruence between narrative and game music (Ekman, Citation2014) and its effect on game enjoyment (Jia, Citation2022; Klimmt et al., Citation2019), we suspect that thematic music enhanced gameplay experiences by complementing narrative features, which in turn led to a higher level of exercise enjoyment. Our findings expand existing literature on the congruency between narrative and video game music (Ekman, Citation2014; Jia, Citation2022; Klimmt et al., Citation2019) by locating its effect in the exergaming context and providing extended insights regarding the effect of such congruency on exercise experiences. Meanwhile, for middle-aged adults, an insignificant interaction effect on the level of exercise enjoyment may be due to the ceiling effect. The enjoyment level was already high when non-thematic music was presented with narrative features. Therefore, although the enjoyment level was high when thematic music was presented with narrative features, there was not much room for improvement in the enjoyment level.

7. Conclusion

This paper presents a novel study that examined the effect of an audio-based exergame on exercise experience, focusing on two elements: (1) narrative features and (2) thematic characteristics of music. Through a two-week long in-situ experiment, we explored young and middle-aged adults’ amount of exercise and exercise enjoyment when using SPORTIFY, an audio-based exergame. The result of our study indicated that narrative features alone improved the amount of exercise and exercise enjoyment, while thematic music itself did not have an effect on the exercise experience. However, playing thematic music along with narrative features enhanced the level of exercise enjoyment of young adults and the amount of exercise of middle-aged adults.

Our study has several limitations. First, although we were able to collect data outside of the laboratory setting by conducting a field study, we did not get a chance to observe the details of how participants exercised in real life. Therefore, opportunities for validating the reported amount of exercise or exercise enjoyment are missing, which would provide us with further insights into the effects of using narrative features and thematic music. Secondly, we recruited a relatively small sample of 43 participants for each age group. A sensitivity power analysis revealed that the minimum effect size that can ensure the reliability of our testing result is = 0.3 (with α = 0.05, 1-β = 0.8), whereas the effect size of our hypothesis ranged from 0.12 to 0.42. Thus, our experiment is partially underpowered due to the limited sample size. Conducting a further study with a larger size of sample, accompanied by prior power analysis, would be required to bring sufficient evidence to the claim of this study.

Third, a longer study would consider the long-term effects of using SPORTIFY, especially with middle-aged adults. Middle-aged adults were able to exercise with SPORTIFY while not losing interest in narrative features for two weeks. However, such interest can fade away after a longer period of experiments. Even if we did not observe such diminishing interest in our two-week-long experiment, the longer study might discover the different long-term effects of narrative features for middle-aged adults. Lastly, our study has a limitation regarding the potential influence of familiarity with the narrative and music of Super Mario Bros. We adopted Super Mario Bros due to its compatibility with the exercise program. To minimize the confounding effect that could arise from familiarity with Super Mario Bros, we controlled the proportions of participants who are familiar with Super Mario Bros across all conditions. Nevertheless, to eliminate any potential effect of familiarity with narrative and music, future studies should consider designing a new game with an original narrative and music that are unfamiliar to the participants.

Despite such limitations, our study is meaningful in that we examined element-wise effectiveness, rather than the audio as a whole, in an audio-based exergame. Based on our study results, there are three points to consider when developing audio-based exergames. First, one should consider using narrative features, especially specifying characters, goals, and background settings, to improve the exercise experience and encourage users to remain physically active. Secondly, in order to enhance the positive effects of narrative features, it is recommended to use music that can help users envision the theme of the exergames. Last but not least, it is worthwhile to consider the age of target users when utilizing narrative features and thematic music in the audio-based exergame. For example, as mentioned in the discussion, for young adults, we suggest exergame designers include narrative features that can give strong exergame motivation at the initial stage of gameplay and provide young adults with opportunities to control the mood and pace of the music. Meanwhile, for middle-aged adults, we highlight that the type of exercise needs to correspond with narrative features, and the thematic music should include features that support companionship, such as countings in the background.

Given these suggestions, our study can provide ideas for future research on how an audio-based exergame can improve the exercise experience. Considering that older adults aged 65 or above, can benefit from an exergame (Kappen, Mirza-Babaei, & Nacke, Citation2019; Xu et al., Citation2023), a future study that examines the impact of SPORTIFY on an expanded population would be an interesting direction to pursue. To do so, SPORTIFY should be upgraded to provide varying levels of exercise to meet the needs of users with a wider range of physical capacities. In addition, extending our research beyond narrative features and thematic music would be an interesting research topic to pursue.

Supplemental Material

Download MP4 Video (19.8 MB)Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Institute of Information & communications Technology Planning & Evaluation (IITP) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No.2022-0-00608, Artificial intelligence research about multi-modal interactions for empathetic conversations with humans) and Seoul National University Research Grant in 2021.

Disclosure statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Sunhyo Oh

Sunhyo Oh is a master student in the Graduate School of Convergence Science and Technology, Seoul National University. Her research interests include human-computer interaction, conversational AI, and computer-supported cooperative learning.

Jiwon Kim

Jiwon Kim is a master student in the Graduate School of Convergence Science and Technology, Seoul National University. Her research interests include human-computer interaction, STEM education, and Learning Technology.

Gahgene Gweon

Gahgene Gweon is an associate professor at Seoul National University. She received BA degree in computer science and economics from the University of California, Berkeley. She received MS and Ph.D. degrees in human-computer interaction from Carnegie Mellon University. Her research interests include human-computer interaction, learning science, and natural language processing.

Notes

References

- Active Seniors Health Centre (2012). The Benefits and Nuances of HIIT. https://www.activeseniors.net.au/the-benefits-and-nuances-of-hiit/?fbclid=IwAR299OkCliga47R3KQ4R0f-IQ63aLV12H3Ic9bRPFRN3Icy-a5QFWBjGYtM. (Online;accessed 2022-05-02)

- Almadhoun, H., Issa, K. S., Abushahla, K. H., Al-Qadi, A. R., & Issa, A. (2020). Voice-operated exergame with motion feedback for after-stroke hand rehabilitation [Paper presentation].2020 International Conference on Assistive and Rehabilitation Technologies (Icaretech), In (pp. 30–35). https://doi.org/10.1109/iCareTech49914.2020.00012

- Atan, T. (2013). Effect of music on anaerobic exercise performance. Biology of Sport, 30(1), 35–39. https://doi.org/10.5604/20831862.1029819

- Baranowski, T., Maddison, R., Maloney, A., Medina, E., Jr,., & Simons, M. (2014). Building a better mousetrap (exergame) to increase youth physical activity. Games for Health Journal, 3(2), 72–78. https://doi.org/10.1089/g4h.2014.0018

- Bormann, D., & Greitemeyer, T. (2015). Immersed in virtual worlds and minds: Effects of in-game storytelling on immersion, need satisfaction, and affective theory of mind. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 6(6), 646–652. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550615578177

- Brandt, N., & Razon, S. (2019). Effect of self-selected music on affective responses and running performance: Directions and implications. International Journal of Exercise Science, 12(5), 310–323. https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/ijes/vol12/iss5/4

- Buttussi, F., & Chittaro, L. (2010). Smarter phones for healthier lifestyles: An adaptive fitness game. IEEE Pervasive Computing, 9(4), 51–57. https://doi.org/10.1109/MPRV.2010.52

- Chao, Y.-Y., Lucke, K. T., Scherer, Y. K., & Montgomery, C. A. (2016). Understanding the wii exergames use: Voices from assisted living residents. Rehabilitation Nursing : The Official Journal of the Association of Rehabilitation Nurses, 41(5), 279–288. https://doi.org/10.1002/rnj.216

- Chittaro, L., & Zuliani, F. (2013). Exploring audio storytelling in mobile exergames to affect the perception of physical exercise [Paper presentation]. In 2013 7th International Conference on Pervasive Computing Technologies for Healthcare and Workshops, (pp. 1–8).

- Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2014). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Sage publications.

- Cowan, B. R., Pantidi, N., Coyle, D., Morrissey, K., Clarke, P., Al-Shehri, S., … Bandeira, N. (2017). What can i help you with?” Infrequent users’ experiences of intelligent personal assistants. In Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction with Mobile Devices and Services (pp. 1–12).

- de la Casa Pérez, A., Latorre Román, P. Á., Muñoz Jiménez, M., Lucena Zurita, M., Laredo Aguilera, J. A., Párraga Montilla, J. A., & Cabrera Linares, J. C. (2022). Is the xiaomi mi band 4 an accuracy tool for measuring health-related parameters in adults and older people? An original validation study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(3), 1593. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031593

- Dutz, T., Hardy, S., Knöoll, M., Göobel, S., Steinmetz, R. (2014). User interfaces of mobile exergames. In International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction (pp. 244–255).

- Edworthy, J., & Waring, H. (2006). The effects of music tempo and loudness level on treadmill exercise. Ergonomics, 49(15), 1597–1610. https://doi.org/10.1080/00140130600899104

- Ekman, I. (2014). A cognitive approach to the emotional function of game sound. In K. Collins, B. Kapralos, & H. Tessler (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Interactive Audio. Oxford Handbooks. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199797226.013.012

- Erikson, E. H., Erikson, J. M. (1998). The life cycle completed (extended version). WW Norton & Company. Exercises, queensland government department of health. (2021). https://www.healthier.qld.gov.au/fitness/exercises/. (Accessed: 2021-12-14)

- Farič, N., Potts, H. W. W., Rowe, S., Beaty, T., Hon, A., & Fisher, A. (2021). Running app “Zombies, Run!” Users’ Engagement with Physical Activity: A Qualitative Study. Games for Health Journal, 10(6), 420–429. https://doi.org/10.1089/g4h.2021.0060

- Friberg, J., & Göardenfors, D. (2004). Audio games: New perspectives on game audio. In Proceedings of the 2004 Acm Sigchi International Conference on Advances in Computer Entertainment Technology (pp. 148–154).

- Gao, Y., Mandryk, R. L. (2011). Grabapple: The design of a casual exergame. In International Conference on Entertainment Computing (pp. 35–46).

- Geelan, B., Zulkifly, A., Smith, A., Cauchi-Saunders, A., de Salas, K., Lewis, I. (2016). Augmented exergaming: Increasing exercise duration in novices. In Proceedings of the 28th australian Conference on Computer-Human Interaction (pp. 542–551). https://doi.org/10.1145/3010915.3010940

- Gfeller, K. (1988). Musical components and styles preferred by young adults for aerobic fitness activities. Journal of Music Therapy, 25(1), 28–43. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmt/25.1.28

- Goh, D. H.-L., Razikin, K. (2015). Is gamification effective in motivating exercise?. In International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction (pp. 608–617).

- Gómez-Portes, C., Vallejo, D., Corregidor-Sánchez, A.-I., Rodríguez-Hernández, M., Martín-Conty, J., Schez-Sobrino, S., & Polonio-López, B. (2021). A platform based on personalized exergames and natural user interfaces to promote remote physical activity and improve healthy aging in elderly people. Sustainability, 13(14), 7578. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13147578

- Görgü, L., Campbell, A. G., McCusker, K., Dragone, M., O’Grady, M. J., O’Connor, N. E., O’Hare, G. M. (2010). Freegaming: Mobile, collaborative, adaptive and augmented exergaming. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Advances in Mobile Computing and Multimedia (pp. 173–179).

- Graves, L. E., Ridgers, N. D., Williams, K., Stratton, G., Atkinson, G., & Cable, N. T. (2010). The physiological cost and enjoyment of wii fit in adolescents, young adults, and older adults. Journal of Physical Activity & Health, 7(3), 393–401. https://doi.org/10.1123/jpah.7.3.393

- Hefner, D., Klimmt, C., & Vorderer, P. (2007). Identification with the player character as determinant of video game enjoyment [Paper presentation]. In Entertainment Computing.icec 2007: 6th International Conference, Shanghai, China, september 15-17, 2007. proceedings (pp. 39–48).

- Ho, S. S., Lwin, M. O., Sng, J. R., & Yee, A. Z. (2017). Escaping through exergames: Presence, enjoyment, and mood experience in predicting children’s attitude toward exergames. Computers in Human Behavior, 72, 381–389. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.03.001

- Hutchinson, J. C., & Sherman, T. (2014). The relationship between exercise intensity and preferred music intensity. Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology, 3(3), 191–202. https://doi.org/10.1037/spy0000008

- indoor health exercises, korea sports promotion foundation (2021). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hr25e1wy75k. (Accessed: 2021-12-02)

- Jia, D. Y. (2022). [ Playing with the right soundtrack: Effects of video game music congruency on enjoyment ]. [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Purdue University Graduate School.

- Kappen, D. L., Mirza-Babaei, P., Nacke, L. E. (2017). Gamification through the application of motivational affordances for physical activity technology. In Proceedings of the Annual Symposium on Computer-Human Interaction in Play (pp. 5–18). https://doi.org/10.1145/3116595.3116604

- Kappen, D. L., Mirza-Babaei, P., & Nacke, L. E. (2019). Older adults’ physical activity and exergames: A systematic review. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, 35(2), 140–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2018.1441253

- Kari, T., Piippo, J., Frank, L., Makkonen, M., Moilanen, P. (2016). To gamify or not to gamify?: Gamification in exercise applications and its role in impacting exercise motivation. BLED 2016: Proceedings of the 29th Bled eConference “Digital Economy”, ISBN 978-961- 232-287-8.

- Keesing, A., Ooi, M., Wu, O., Ye, X., Shaw, L., Wöunsche, B. C. (2019). Hiit with hits: Using music and gameplay to induce hiit in exergames. In Proceedings of the Australasian Computer Science Week Multiconference (pp. 1–10).

- Kendzierski, D., & DeCarlo, K. J. (1991). Physical activity enjoyment scale: Two validation studies. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 13(1), 50–64.

- Klimmt, C., Hartmann, T., & Frey, A. (2007). Effectance and control as determinants of video game enjoyment. Cyberpsychology & Behavior: The Impact of the Internet, Multimedia and Virtual Reality on Behavior and Society, 10(6), 845–847. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2007.9942

- Klimmt, C., Possler, D., May, N., Auge, H., Wanjek, L., & Wolf, A.-L. (2019). Effects of soundtrack music on the video game experience. Media Psychology, 22(5), 689–713. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2018.1507827

- Koch, M., von Luck, K., Schwarzer, J., Draheim, S. (2018). The novelty effect in large display deployments.experiences and lessons-learned for evaluating prototypes. In Proceedings of 16th European Conference on Computer-Supported Cooperative Work-Exploratory Papers.