Abstract

The transformative capacity of artificial intelligence (AI) in different sectors is rapidly progressing. One of the sectors in which there has been an increase in these developments is the education sector, particularly higher education (HE). Although some studies have begun to consider the advances in AI to incorporate solutions at various stages of the university educational process, the role of students as possible co-creators of these developments has not yet been considered. From a perspective of value co-creation and service-dominant logic (SDL), this study seeks to identify the typologies of value perceived by university students with respect to different AI solutions applied to the learning process in the framework of a value network composed of themselves and other actors in the network. Using a qualitative, phenomenological research approach, four workshop sessions were developed with a total sample of 93 students from three Colombian universities. The results indicate that students mostly respond in agreement with the co-creation of value based on the concepts of AI functions in the future scenario of HE. These AI functions include the machine teacher and the Smart Tutoring App. The chatbot is among the functions associated with value co-destruction, which is one of the most widespread developments in the area of user experiences in business. Finally, we discuss these findings and offer implications for guiding public policy and strategic decisions by university boards in this highly relevant area.

1. Introduction

The transformative capacity of artificial intelligence (AI) in different sectors is rapidly advancing. In the last two years, venture capital investments in AI applications have totaled more than $5 trillion globally (Rangaswamy et al., Citation2020). Users have benefitted through lower service costs, more service channels and the ability to increase employee creativity and innovation as AI progressively takes on more and more tasks that are repetitive and tedious (Haenlein & Kaplan, Citation2019). One of the sectors in which these developments are increasing is the educational sector (Sökmen et al., Citation2023), particularly in higher education (HE; Holmes et al., Citation2019; Uribe-Saldarriaga et al., Citation2022). Recently, some studies have begun to take AI advances into account to incorporate solutions at different stages of the educational process in universities, such as attracting and recruiting students for different programs (Elnozahy et al., Citation2019), orientation and retention after they have been admitted (Rivera et al., Citation2018), identifying strengths and weaknesses of each student, and predicting their future performance and interest in emphases within programs (Elnozahy et al., Citation2019). However, these studies have not yet considered the role of students as possible co-creators of these developments; thus, an approach from the perspective of value co-creation and service-dominant logic (SDL) could provide significant information to guide public policies and strategic decisions by university boards in this highly relevant area.

Value co-creation is a two-way process in which users actively participate with organizations in the improvement or creation of products and services through the combination of institutional and learner resources, in such a way that they act more as partners and less as passive agents who receive knowledge and skills without having a major role in the process (Dollinger & Lodge, Citation2020; Grönroos & Gummerus, Citation2014). In the context of HE, students contribute their learning ability, intelligence, study habits, personality, and expectations of the educational process. On the institutional side, resources comprise class materials, modules, assessments, laboratory infrastructure, and the activities and methods designed to achieve student learning (Díaz-Méndez & Gummesson, Citation2012). From this perspective, HE is first seen as an experiential service that should, therefore, be considered from the SDL (Paredes, Citation2022; S. L. Vargo & Lusch, Citation2017), and second, the concept of co-creation depicts the transition from the traditional tangible product-centered logic to a service-centered logic in which services and experiences are exchanged instead of tangible goods (Binkhorst & Den Dekker, Citation2009; Fagerstrøm & Ghinea, Citation2013; Prebensen et al., Citation2013; Stephen L. Vargo & Lusch, Citation2017).

This conception is innovative in that it recognizes the incorporation of the consumer’s intangible resources within their own experience, resulting in a mutual exchange of resources between the organization and the consumer through the experience itself (Smørvik & Vespestad, Citation2020). Recently, research has pointed out the relevance of the concept of co-creation in various contexts, including in Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) to make their processes more learner-centered (Díaz-Méndez et al., Citation2019; Fleischman et al., Citation2015). If HEIs are assumed to be in the service marketing framework, then it is important to evaluate the creation of experiences that meet the needs of students both at the level of administrative services and learning processes without prioritizing student satisfaction over learning outcomes (Gunarto et al., Citation2018). This discussion of the student orientation of HEIs is relevant given that this is a sector that has become highly competitive, making retention a major operational and economic burden for many universities, not to mention the increasing costs of student recruitment (Guilbault, Citation2016).

This context presents an opportunity to explore the role that AI can play in practical solutions within HEIs based on an understanding of these technologies in value co-creation with a learner-centered approach. This opportunity aligns with the call to explore how the use of AI-based technologies in different contexts can impact the configuration and logic of value co-creation systems (Barile et al., Citation2021). This also responds to the criticism of traditional marketing that it has not shown the capacity to study the rapid changes in consumer behavior associated with new technologies in different markets (S. L. Vargo & Lusch, Citation2017). In relation to this, it has been proposed that “Education 4.0” involve the application of AI solutions in a student-centered educational system (Molnár & Szüts, Citation2018). This possibility is also relevant because in some territories, the shortage of educators makes the integration of advanced technology into the education system a latent need (Sandu & Gide, Citation2019). Although some research topics on AI in the context of HEIs have already been explored, more research on the use of AI in the co-creation of learning experiences is needed (S. Li et al., Citation2021; Xie et al., Citation2022). This process is part of what is also known as digital servitization, which seeks to explore opportunities for value creation and diversification of revenue streams for organizations that provide a service through the incorporation of technology while giving the consumer the ability to determine how, when and where the service is delivered (Adapa et al., Citation2020; Schiessl et al., Citation2022; Sklyar et al., Citation2019). This study also responds to the call for more research at the micro level of service transformation, including users, in this case students, as a complement to the macro-level approach that takes into account the formation of service networks and intercompany partnerships (Mandelli & La Rocca, Citation2014).

This study addresses these gaps in the literature by posing from the perspective of SDL and value co-creation the following research question: What are the typologies of value that university students perceive with regard to different AI solutions applied to the learning process in the framework of a value network composed of themselves and other actors in the network? From this main question, the study allows us to establish from an experiential perspective whether students identify potential value co-creation or, on the contrary, whether they consider that the possibility of value co-destruction exists for some of the AI solutions, all within the framework of the value network made up of different actors that are part of the HEIs. Second, the study allows an identification of student perceptions of the AI solutions by applying an approach based on the value co-creation network in which other actors that are part of the HEI system are found.

In this way, we start from the main role of students with their cognitive resources that together with the resources of the institution, allow us to arrive at a construction of a future scenario of these value co-creation networks (Čaić et al., Citation2018) for AI-based solutions that are already reported in recent literature, mainly in the computer science field (Chan & Fung, Citation2020; Leite & Blanco, Citation2020; Ondas et al., Citation2019; Troussas et al., Citation2020). Third, this study contributes to the application of a phenomenological research methodology, which has been proposed as a viable option for conducting qualitative studies in education (Aagaard, Citation2017). This approach considers the subjective human experience, in which the perception of the facts surrounding the individual is given (Dziewanowska, Citation2017). Specifically, through the application of focus groups and generative card activities (Čaić et al., Citation2018), we seek to describe how students conceive of the current value co-creation network and what this network would look like in the future if AI-based solutions that have already been developed in different regions of the world were incorporated.

2. Background

2.1. Service-dominant logic (SDL) and co-creation of value

SDL views the consumer and the organization as co-creators of value in a collaborative and ongoing way throughout a service delivery process (Lusch et al., Citation2008). Value creation occurs in the act itself, known as value-in-use, and consists of the continuous process of exchanging intangible resources, such as skills and knowledge, between the consumer and the organization (Grönroos, Citation2008; Vargo & Lusch, Citation2004). Furthermore, the application of a systems perspective through SDL allows for a closer and more realistic approach to how technology influences and shapes the behavior and experience of users in contexts in which they interact with other actors in a process through which value emerges (Vargo et al., Citation2017). Recently, the consumer has begun to be considered not only as the main actor in this process but also as the main beneficiary of co-creation in a service ecosystem that includes AI within a network of actors that enables the integration of resources of different types (Manser Payne et al., Citation2021). Despite this growing interest, value co-creation is only just beginning to be developed in the context of HEIs, and there is an absence of conceptual models and a large amount of content to be explored (Díaz-Méndez & Gummesson, Citation2012; Elsharnouby, Citation2015). Value co-creation with the use of AI in the student experience at HEIs is considered to be a task that involves the participation of students and institutional staff to improve the academic and administrative experience (Nguyen et al., Citation2021). Involving students in these improvement processes can make the experience more relevant, especially since adults perform better when they have a purpose and when they perceive the present and future value of HE (Tøndel et al., Citation2018).

Another important feature related to the development of the SDL in educational contexts is the adoption of information and communication technologies and the way in which these technologies have been changing the experiences of students, academics and other actors within these value networks. These changes have enabled the expansion and modularization of educational coverage, as in the case of virtual education, as well as the systematization of many support processes (Mandelli, Citation2011). In this sense, the literature on service marketing has emphasized how digital solutions have had an impact on the whole system, on the back-office level, on the front-office and on Customer Relationship Management (CRM) models based on an analysis of user data. However, the impact at the micro level, that is, how these new technologies are modifying the interaction between network actors involving organizations and users, still needs to be explored (Mandelli & La Rocca, Citation2014).

Another relevant aspect is the suggestion that there are at least two dimensions to value co-creation. According to Ranjan and Read (Citation2016), these consist of two sub-processes: first, the co-production of value when the value proposition, including tangible, social and digital elements, is created or modified with the participation of users and, second, value for the consumer at the point of use of the service, a concept that comes from SDL and is called value-in-use (Lusch & Vargo, Citation2006). By facilitating co-production, the organization adopts a new perspective in which it is not assumed at the outset that the needs of the users are known; instead, the organization allows greater access to the way in which processes and learning-related activities are planned through the exchange of opinions, suggestions and objections in an environment that is open to change (Dollinger et al., Citation2018). These dimensions are found in value networks in which various actors, including academics, administrative support staff and peers, interact with each other to generate value throughout the duration of provision of the educational service (Sweeney et al., Citation2015). If HE can be considered as a service that requires a high level of student involvement, the process of value co-creation implies that students, as the main actors in the network, will spend significant time and effort searching for, generating and sharing information with other actors in the network so that value co-creation is also effective when resources (e.g., cognitive) are integrated among classmates as well as with course lecturers (Kim, Citation2019). In this sense, this study assumes Čaić et al. (Citation2018, p. 180) definition of value network “as service beneficiaries” conceptualizations of actor constellations and their value co-creating/destroying dynamics for a particular service. In view of the changes that have been taking place since the introduction of digital platforms in educational services, it is relevant to consider how AI-based solutions can contribute to value co-creation or co-destruction, something that may change the very notion of what functionalities or features of these developments may be associated with one or the other category from the perspective of learners and their relationship of resource integration with other actors in the value network. In order to visualize this notion from the students’ perspective, it is beneficial to apply value co-creation maps as a methodological tool to be applied to the HE context, as has been done in areas such as health care (Čaić et al., Citation2018).

2.2. Artificial intelligence in a higher education context

The growing importance of AI to consumers in multiple everyday activities, ranging from media and entertainment consumption on digital platforms to shopping experiences on both online and physical sites (Bassano et al., Citation2018), has led to an increase in the ubiquity of AI in consumers’ lives and the adjustment of organizational processes to accommodate this reality shaped by computer science derived technologies (Matta et al., Citation2022; Uribe-Saldarriaga et al., Citation2022). However, considering these solutions from a software development approach alone may neglect the multidimensional experience that the consumer has when interacting with these technologies (Puntoni et al., Citation2021). Therefore, it is relevant to explore experiences of and responses to AI in different contexts, including HE. AI can be seen as the attribution of human-like intelligence to machines (Ma & Sun, Citation2020). Since the 1990s, machine learning has been a mainstream paradigm for the application of AI in different domains, and it has accelerated innovation in areas, such as education, finance and health. By interacting through digital platforms, organizations came to rely on an abundance of data that, properly analyzed, can generate knowledge to guide business decisions at different levels (Jeon, Citation2022; Rust, Citation2020). Marketing, in particular, is increasingly relying on machine learning algorithms to support various functions that deliver value to consumers, such as decreased costs, increased service channel options and opportunities to improve the purchase process and post-purchase support in product categories as diverse as luxury goods (Bassano et al., Citation2020; Mustak et al., Citation2021).

In the field of HE, different levels of development can be found for the AI solutions applied in these processes. The first of these was chatbots. In recent years, the chatbots market has seen a significant increase due to the widespread use of smartphones and messaging apps. Among the categories that have most incorporated this technology are food delivery, Fintech, e-commerce, health care apps, and even music education (P.-P. Li & Wang, Citation2023; Prakash & Das, Citation2020; Sandu & Gide, Citation2019). A chatbot is an AI program that enables natural language-based communication with the user through messaging apps and websites in either an open or closed domain. In the open domain, the chatbot answers general questions on general topics, while in the closed domain, it answers questions only on specific topics (Mostafa & Kasamani, Citation2022; Ranoliya et al., Citation2017). Chatbots have been developed in education for some time. They are categorized into those that have a learning objective and those that are designed to support administrative processes, such as advising students on their academic path and assisting them with procedures (Ondas et al., Citation2019). Those with an educational component offer students a set of content that is adjusted to their needs and speed of learning, thus becoming a permanent support during their career (Molnár & Szüts, Citation2018).

Second, AI-based software has been developed for the automatic generation of grades and feedback in undergraduate courses. One study compared the performance of a group of students in a coding class depending on whether they received automatic feedback or feedback written by the teacher. The results obtained by the students in the subject exams indicated that the students who received human feedback had a better understanding of the concepts and application in the syntax of the algorithms. This suggests that these tools are still in the early stages of development and that more research is needed regarding how students perceive this information and the usefulness it can have in different areas and processes (Leite & Blanco, Citation2020). Third, based on the high penetration of smartphones and the increase in daily app usage time, especially among younger users (Robayo-Pinzon et al., Citation2021), the development of software to facilitate the adoption of mobile e-learning has been proposed. Research has been done to test a prototype app that combined an AI function through a chatbot with functions that facilitate students to form groups for mobile collaborative learning. In these groups, students interact with each other and with the chatbot. The results indicated that students used the chatbot to ask questions about academic content but did not use it to search for audio-visual content. In addition, students generally found the instant messaging function easy to use and showed high satisfaction with the functionality of the app (Chan & Fung, Citation2020).

Fourth, a recent line of research is focused on harnessing the popularity of social networks among younger audiences as a potential platform for learning through communication and collaboration functionalities between students and teachers (Cabrera et al., Citation2017). One study tested a prototype Facebook-based smart tutoring application called i-LearnC# to support learning in a coding course. This application leverages the capabilities of Facebook and adds an AI-based virtual coach that provides students with personalized advice regarding gaps they have in basic course concepts. It also performs assessments based on Bloom’s taxonomy, giving feedback on the results obtained. The app was very well received based on the results obtained in terms of both satisfaction and academic performance among the group of students in the course (Troussas et al., Citation2020).

Another possibility that is still at an early stage of development is the concept of the machine teacher or AI-based teaching assistant, which has been preliminarily defined as a technology that is significant in enhancing the human learning process on different levels, not only cognitive but also affective and behavioral, by applying different methods of interaction (Kim et al., Citation2020). Machine teachers can have a physical or virtual presence. There are some reported cases of physically present robots that have been used in teaching contexts, such as NAO or Sony AIBO, but virtual machine teachers are more likely to be developed (Kim et al., Citation2016). A recent study investigated the perceived usefulness and ease of communication with an AI teaching assistant based on the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM). The reported results showed that perceived usefulness, followed by ease of communication, had a positive influence on the intention to use the AI teaching assistant. This indicates a rather positive student attitude toward the machine teacher concept, which opens the door to developing prototypes to be tested in academic contexts (Kim et al., Citation2020). Another proposal consists of an intelligent tutoring system (ITS) concept that combines web-based information searches with an interface based on natural language processing techniques applied to information literacy teaching. The ITSs that have thus far been implemented are focused on teaching very specific activities with immediate feedback. The aim now is to use natural language processing to extend the spectrum of activities to include more complex situations which, in turn, will receive more complete feedback from the ITS (Libbrecht et al., Citation2020).

Finally, another form of AI applied to education is a recommendation system (RS) that serves the function of retrieving and filtering data according to a given profile. RSs have been used to support learning activities through the selection and retrieval of relevant information for academic processes, in particular, to provide students with guidance regarding possible training options, such as universities, academic programs or subjects within a personalized curriculum (Rivera et al., Citation2018). More specific aspects of these concepts and prototypes can be found in . This study seeks to establish what the role of these concepts or prototypes of AI can be within the value co-creation network in HEIs from the perspective of students as central actors in this network.

Table 1. The roles of AI in higher education.

3. Materials and methods

Based on the nature of the phenomenon, an interpretative approach was adopted (Burrell & Morgan, Citation1979) using inductive techniques (De Gortari, Citation1968). The sample consisted of 93 participants, all of them undergraduate students from three Colombian universities, with a gender distribution of 52% male and 48% female, and a mean age of 20.2 years (range 18–28; SD = 2.3). Eight co-creation workshops were conducted during October and November 2021. At the time, universities in Colombia were almost entirely in remote teaching mode because a small percentage of the general population had at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccination. It was not until early 2022 that some HEIs began to return to full face-to-face lectures. In this sense, the study participants as well as high school and university students in general had by that time almost a year and a half of lectures and interaction with their peers through digital platforms, the most popular in this territory being Zoom, Microsoft Teams, and Google Meet. Furthermore, by that time many of them, globally, had had at least a year’s experience with different platforms and software solutions useful for remote academic work, including instant messaging apps such as WhatsApp and apps, such as Menti, Edmodo, Miro, among others (Aduba & Mayowa-Adebara, Citation2022). Particularly, among the study participants, a significant percentage of students were found to be multi-device learners. For example, 87.1% use at least two devices for their academic tasks, with the most common combination being laptop and smartphone (57%), followed by the combination of laptop, tablet, and smartphone (19.4%). The workshops were developed from design-based thinking as a methodology for service innovation (Brown, Citation2009; Eikland Bækkelie, Citation2016; Kornbluh, Citation2015; Macías Rodríguez, Citation2017) as used to discover (a) the opportunities for incorporating AI in the everyday life of HE students, (b) the potential roles in which it would be highly acceptable to incorporate AI, and (c) the activities that could be supported and/or facilitated by this technology without replacing them within the value networks.

A process of accumulation and aggregation of the information obtained from the different co-creation workshops was then completed, and the information was systematically analyzed using grounded theory (Strauss & Corbin, Citation1994, Citation2008). This qualitative analysis maintains the vision of the participants and their closeness to AI, a point of view that was collected under a single method and at a single point in time, that is, a cross-sectional transversal approach. Thus, data collection was carried out through design-based thinking workshops in which participants were asked to analyze value maps or value networks based on the everyday experience of students in the context of HE (Čaić et al., Citation2018; Choi et al., Citation2013; Lv & Wang, Citation2010; Sanders, Citation2000).

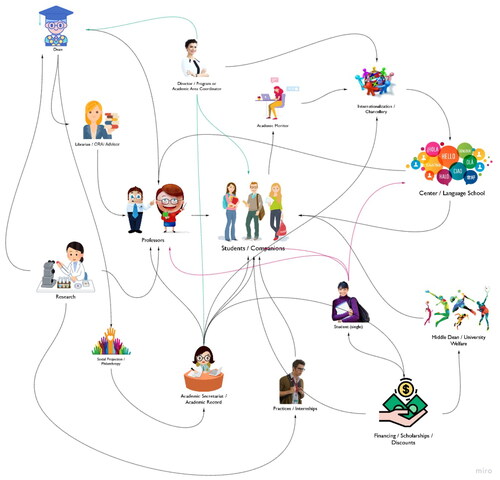

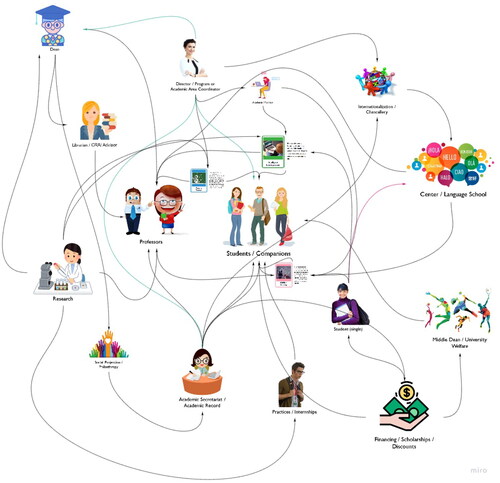

First, following the protocols of data processing and ethics, consent was expressly requested to use the data provided by the participants who took part in the phenomenological exercise in an anonymous and aggregate form. Second, participants were empathized with the concept of AI, its uses and characteristics (Beckman & Barry, Citation2007; Steinbeck, Citation2011). Third, the status quo was addressed in order to define and/or confirm the relationship networks that arise daily in a student’s experience in HE, identifying those networks that in the light of the literature have not been explored in depth, delimiting their interactions with the student and those that arise between actors other than the student. For this purpose, cards were created for each actor and a generic categorization was proposed in order to avoid ambiguity about the exercise (Čaić et al., Citation2018; Clatworthy, Citation2011; Culen et al., Citation2014).

Subsequently, the workshop presented the different existing technological solutions based on AI to support multiple activities in the HE experience and purpose cards containing information were designed to represent each one exercise (Čaić et al., Citation2018; Culen et al., Citation2014). The group of participants was asked to discuss, argue, and rank the solutions presented in terms of the degree of importance they foresaw for their development and implementation using AI in their own educational environments. Finally, as a last stage, the participants had to propose or devise a future scenario in which AI would intervene and the potential roles in which it would create value for the network. This role as articulator and/or mediator of these relationships in the value maps or networks was also explored, as were the perceptions of the associated risks, foreseeable obstacles, and other possible elements leading to the destruction of value within the network.

4. Results

The information gathered in the four workshop sessions with a total of 93 participants has been divided into three sections: value network map – status quo; AI Ideation in HE; and value network map – future scenario. The results involving the actors in the context of HEIs with AI-based functions from the theoretical perspective of SDL and value co-creation and co-destruction were developed by means of the generated descriptive analyses, the collected value maps, the coding of the information and the emerging aggregated dimensions. It is important to mention that there were no significant differences in the results with respect to the seniority of the participants. This is probably because the high majority were in their second and third year and all had been doing their academic work in the remote learning conditions described in the previous section.

4.1. Value network map – status quo

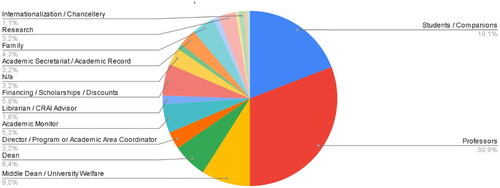

presents the value network map that was created when participants placed students/peers in the center of the network to establish value relationships with the other actors. illustrates the results obtained on the perceived importance of the actors that are part of the participants’ value network. The three most important actors were: Teachers (30.9%), Students/Peers (19.1%), and Student Welfare Office (9.0%).

4.2. AI ideation in higher education

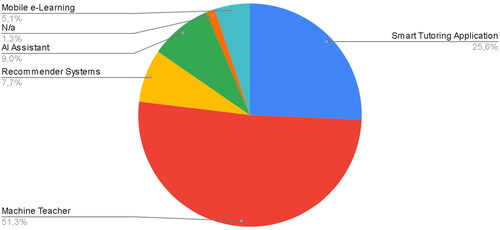

presents the AI Ideation in HE based on the functions ordered from the most important to the least important. Overall, the most important for the participants was the Machine Teacher (51.3%); in second place, the Intelligent Tutoring Application (25.6%); and in third place, the AI Assistant (9.0%). presents the total results obtained in relation to the AI functions and their importance for the participants.

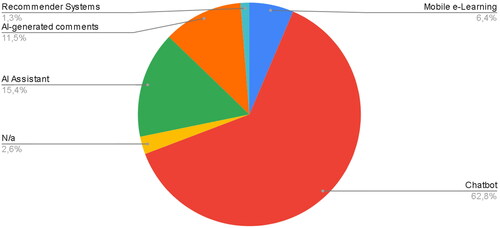

The functions perceived as less important by the participants were Chatbot (52.8%), AI Assistant (15.4%), AI-generated Feedback (11.5%), Mobile e-Learning (6.4%), and RSs (1.3%). presents the complete results obtained in relation to the AI functions of lesser importance to the participants.

4.3. Value network map – future scenario

In the Value Network Map – Future Scenario shown in , the students integrated the current value network with the AI functions to configure a prospective scenario of the relationships between the actors from the AI implementation. In relation to the AI-based solution in the future scenario, the students were asked to name the solution, and they proposed combinations of education with AI or technology: AI Education Package System, E-Study, Educational AI, among others. When they were asked to assign a gender, 43.5% considered the proposed solution to be feminine, 40.6% genderless, 10.1% masculine, and 5.8% mixed.

5. Thematic analysis

Taking as a starting point the responses obtained from the participants, a thematic analysis was developed to generate contextual inferences from the information gathered. presents the coding of the first stage taking into account perspectives on value co-creation and co-destruction.

Table 2. Coding of the value network map – status quo.

presents the coding of the second stage based on AI functions and their implications for creating or destroying value in the network.

Table 3. Coding of AI ideation in higher education.

The coding of the third stage is presented in based on the responses obtained from the participants regarding the future scenario of HE from the integration of the AI functions into the value network in the current scenario.

Table 4. Coding of the value network map – future scenario.

6. Aggregate dimensions

Twelve aggregated dimensions emerged from the associations derived from the coding of participant responses and the categorization that followed in relation to value co-creation and co-destruction in HE. These dimensions, presented in , represent the main themes identified in relation to the role of AI functions in HE.

Table 5. Aggregate dimensions: map of the value network – status quo.

Table 6. Aggregate dimensions of AI ideation in higher education.

Table 7. Aggregate dimensions of the value network map – future scenario.

For the first stage, the creation of the map of the value network – status quo, the following aggregate dimensions emerged: integrated development of the human being from education and reduction of the human factor in education. The first corresponds to code associations around value co-creation within university education in intersection with elements related to an integral process: social, intellectual, professional, and human skills in education. The second refers to the co-destruction of value from the perspective of the participants in the value network from the reduction in the presence of human beings in education due to technological substitution.

For the second stage, namely AI Ideation in HE, the dimensions added in relation to value co-creation correspond to the following: AI applications for comprehensive training, AI-based tools for teacher empowerment and substitution of actors in the value network in HE. According to the participants’ perceptions of AI functions, these dimensions make it possible to add value to their educational processes from technology and benefit not only students but also different actors in the value network. The added dimensions were a decrease in human interactions and functional limitations of AI in HE, both of which are embedded within the co-destruction of value around the functions of AI and its implications in human relationships in an educational context and the functional deficiencies of AI when it comes to meeting the needs of users.

Finally, the aggregated dimensions corresponding to the third stage, Value Network Map – Future Scenario, in relation to value co-creation were as follows: Collaboration Function, Optimization Function and Information Security. For the participants, the possibilities offered by AI for the future are mainly related to optimization and accompaniment in education, increased information security, more direct communication, and increased collaborative learning. However, in relation to the co-destruction of value in the future of HE, the following dimensions emerged: dehumanization of education and privacy risks. Thus, the dehumanization of education through technology also implies loss of value for some participants: loss of jobs, decrease in human interactions, decrease in information security, and privacy risks.

7. Discussion

This study explored the perceptions and attitudes of a sample of university students regarding the effect of incorporating AI-based solutions into the value network based on the concepts of value co-creation and value co-destruction through the integration of resources from different actors in the network, such as students, peers, faculty, and support staff. The twelve themes that emerged from the coding and categorization in relation to the actors and functions of IA from the students’ responses in each of the stages of the workshops are discussed below.

7.1. Stage I. Value network map – status quo

7.1.1. Value Co-creation

7.1.1.1. Theme 1 – Integrated human development through education

The first result identified in this study is the search for integrated development from HE, associating academic activities with the social aspects of university life and the promotion of physical and mental health in the professional training processes of the participants. Likewise, they recognize the value of the different actors, particularly the professors and peers/students, as the basis of the university and essential determinants that are difficult to replace but that have ample room for improvement due to the effect of technology, including university welfare toward an integral education.

7.1.2. Value Co-destruction

7.1.2.1. Theme 2 – Reduction of the human factor

From the responses shared by participants regarding the co-destruction of value, there is concern about the reduction of the human factor from the incursion of AI into HE. This is evident in the fear that AI may replace lecturers or administrative staff, while there is a preference for maintaining a personal touch in both academic and administrative interactions.

7.2. Stage II. Ideation of AI in higher education

7.2.1. Value Co-creation

7.2.1.1. Theme 3 – Applications of AI for integrated learning

In their responses to the AI functions, participants mentioned the reasons that led them to consider some functions as more important than others. These reasons were mostly related to their training processes and the potential for AI functions and applications to improve these, especially Machine Teacher, which was considered a function that could be very beneficial to the students because they could gain a better understanding of the subject when they needed it. The Intelligent Tutoring Application allows students to strengthen their knowledge while solving doubts arising from the lectures given by teachers, while the AI Assistant functions to speed up work and save time spent on unnecessary activities. Additionally, other relevant functions for the interviewees were Mobile e-Learning and RSs. In the case of Mobile e-Learning, it stands out for its possibilities for teamwork and collaborative learning. RSs are perceived as a valuable tool in the training process and in the search for knowledge based on personalized recommendations adapted to individual needs.

7.2.1.2. Theme 4 – AI-based tools for teacher empowerment

When participants were asked about the substitution of network actors by AI functions, significant attributes emerged from the experiences and interactions with their teachers. In the case of the AI Assistant and the Machine Teacher, they were perceived not only as replacement roles, but as complements to the teaching work, recognizing the importance of the human factor in education. Students expressed the relevance of human interaction and communication. The possibility that teachers could benefit from the tool by knowing which topics they should explain and which could be better explained by the Machine Teacher also emerged as a source of value.

7.2.1.3. Theme 5 – Substitution of value network actors in higher education

A large part of the participants considered that the functions of the Intelligent Tutoring Application, Machine Teacher and RSs have the potential to replace different actors in the value network in HE, such as academic monitors and lecturers, but they also included administrative staff from a perspective of increased efficiency and personalization in HEIs.

7.2.2. Value Co-destruction

7.2.2.1. Theme 6 – Decreasing human interaction

A few students recognized not only the potential for value co-creation but also the co-destruction of value primarily in relation to the loss of human contact. Some answers indicated that human interaction is fundamental for acquiring a good level of education and that a lack of direct contact with the student would not contribute anything significant to their academic process.

7.2.2.2. Theme 7 – functional limitations of AI in higher education

Finally, another aspect of value co-destruction was related to the functional limitations of AI. For the participants, the functional limitations of the Chatbot and AI-generated Comments result in a loss of efficiency and reliability in the processes.

7.3. Stage III. Value network map – future scenario

7.3.1. Value Co-creation

7.3.1.1. Theme 8 – The role of collaboration

In relation to the future scenario and AI-based solutions, the integration of these technologies presented a high potential of value co-creation for the participants based on support and assistance in training processes, a significant element to add value to the university experience in the future.

7.3.1.2. Theme 9 – The role of optimization

For the participants, the optimization of academic activities turned out to be a key factor in adding value to the network in a future scenario. The optimization function is not limited to academia but relates to different university areas to achieve greater degrees of dynamism in processes and procedures as well as cost reduction and elimination of charges, thus contributing to an optimal combination of efficiency and effectiveness. In addition, some students mentioned a value co-creation component in that this function would facilitate more direct communication, avoiding the complications of human relations. These trade-offs between different points of view found in the group sessions should be taken into account for the implementation of the tools and an eventual communication campaign aimed at the student community.

7.3.1.3. Theme 10 – Information security

Another relevant perception of the participants was related to increased information security from an AI-based solution in HE as opposed to current social media networks and their risks. A potential academic social media network would offer lower perceived risks to students as they would be able to have quality information in a more secure way.

7.3.2. Value Co-destruction

7.3.2.1. Theme 11 – Dehumanization of education

The co-destruction of value for participants in a future scenario was evidenced by the perceived reduction of the human factor in HE through the implementation of AI and the replacement of actors in the value network in addition to the direct elimination of jobs and the reduction of human interactions. In that sense, the future scenario presents a participant position that is mostly focused on value co-creation elements, resulting in a perception that AI offers high levels of efficiency and optimization for HEIs, while a minority mentioned that AI is a threat to the human factor in university organizations.

7.3.2.2. Theme 12 – privacy risks

Finally, the last theme is related to information and its privacy risks from an eventual implementation of an AI solution in HE. According to the views of some participants, technology and its progress necessarily imply greater risks and impacts in terms of privacy.

8. Conclusions

Students overwhelmingly agreed with value co-creation from the concepts of AI functions in the future scenario of HE. Although they primarily recognized that academic and service processes fundamentally still require social interaction between people, particularly among students, faculty, and University Wellbeing Office staff, they are very positive about the possibility of incorporating some of the AI functions that are being developed in various regions of the world. In this respect, the most widely accepted functions are seen as complementary to the work carried out by lecturers and some administrative support areas. These functions include the Machine Teacher and the Smart Tutoring App that can provide an immediate response in some spaces where it is not easy to access the direct accompaniment of the lecturer. Interestingly, the chatbot, which is one of the most widespread developments in the areas of user experience in companies in recent years, is within the functions that are associated with value co-destruction. This is likely due to the fact that at the time and location of the study, the chatbots with which the participants would have had experience were still at a primary stage of development. However, as their functionality evolves, as seems to be the case for the AI-based chatbot service ChatGPT 3 and 4, further testing and studies should be conducted to establish their potential move into the value co-creation category. The aggregate functions associated with value co-creation were found to be collaboration, optimization, and information security, while the functions associated with value co-destruction were dehumanization of education and privacy risks. From these dimensions, HEI managers can plan and consider the potential benefits and risks of incorporating these technologies into the academic and administrative processes of their institutions.

Students may be concerned about issues such as privacy, and they and their parents, teachers, and administrators may be concerned about the eventual dehumanization of education, since it is a process that is carried out under principles of collective construction, as it is also stated in the SDL literature (Barile et al., Citation2021; Bassano et al., Citation2020), thus the process of empowering all the actors and the community that integrate the educational system should be something for HEIs managers to consider. However, it is clear that for the areas reviewed in the empirical validation that originated this article, not everything is replaceable by AI. Moreover, the evidence shows that the use of various AI tools in human life, although they generate concerns about people’s social privacy, can influence their motivations for aspects, such as online identity reconstruction (Hu & Huang, Citation2023). In the framework of this research, it is key to consider the challenges AI faces to be human-centred (Ozmen Garibay et al., Citation2023). The above implies that designs aimed at academic communities should be centered on them, their needs and well-being. In addition, beyond the collection of information and prediction from it, a responsible design with people that respects their privacy and follows human-centered design principles is required. Likewise, this implies that HE managers have appropriate governance and oversight. Additionally, interaction with students and faculty must be respectful of human’s cognitive capacities.

9. Limitations and further research

Although the study had an exploratory character through the application of qualitative, phenomenological techniques, some limitations derive from this approach. First, only a sample of students from an emerging country in Latin America was considered, and this type of study could be undertaken in other regions where there are different levels of development and adoption of these technologies. In addition, only student perspectives as the central agents of the process were taken into account; in future studies, other agents can be considered, especially lecturers and collaborators in certain key functional areas, such as the university wellbeing office. The study also explored attitudes toward the concepts of the AI functions, and it would be important for future research to take a more experimental or action research approach through the application in real university learning contexts of one or more of the AI functions in emerging countries, and in particular new developments, such as ChatGPT 3 and 4, thus enriching knowledge in this important area of study for HEIs. It would also be valuable to give a longitudinal scope to these intervention-based studies to establish student responses over a number of consecutive academic periods, monitoring not only attitudes but also levels of perceived usefulness, adoption and possible differences by content type and academic program, among other moderating variables.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this article.

Author contribution statement

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work, and have approved it for publication.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Oscar Robayo-Pinzon

Oscar Robayo-Pinzon is principal research lecturer at the School of Management and Business, Universidad del Rosario, Colombia. PhD in Engineering, Industry and Organizations at Universidad Nacional de Colombia. Fellow of the Association for Consumer Research (ACR) and the Academy of Marketing Science (AMS). Academic visitor at Cardiff Business School, Cardiff University, UK.

Sandra Rojas-Berrio

Sandra Rojas-Berrio holds a PhD in Management Science from Instituto Politécnico Nacional, México, a BS in Business Administration and a Master’s in Business Administration from the Universidad Nacional de Colombia. Associate Professor at Faculty of Economics, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogota, Colombia.

Jeisson Rincon-Novoa

Jeisson Rincon-Novoa is an MBA and BS with honor degree in Business Administration, and BS with honor degree in Public Accounting. Researcher in Marketing, Management, and Accounting. His research interests include customer and citizen experience (CE), dark side of customer behavior, public management, permanence, and conditional cash transfer in higher education.

Andres Ramirez-Barrera

Andres Ramirez-Barrera is a Business Administration student at the Universidad Nacional de Colombia. He is a researcher at the Management and Marketing Research Group. His main research interests include customer experience, agile methods, behavioral finance, innovation, and entrepreneurship.

References

- Aagaard, J. (2017). Introducing postphenomenological research: A brief and selective sketch of phenomenological research methods. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 30(6), 519–533. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2016.1263884

- Adapa, S., Fazal-e-Hasan, S. M., Makam, S. B., Azeem, M. M., & Mortimer, G. (2020). Examining the antecedents and consequences of perceived shopping value through smart retail technology. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 52, 101901. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2019.101901

- Aduba, D. E., & Mayowa-Adebara, O. (2022). Online platforms used for teaching and learning during the COVID-19 Era: The case of LIS students in Delta State University, Abraka. International Information & Library Review, 54(1), 17–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/10572317.2020.1869903

- Barile, S., Bassano, C., Piciocchi, P., Saviano, M., & Spohrer, J. C. (2021). Empowering value co-creation in the digital age. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1108/JBIM-12-2019-0553

- Bassano, C., Barile, S., Saviano, M., Cosimato, S., Pietronudo, M. (2020). AI technologies & value co-creation in a luxury context. 53th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (pp. 1618–1627). University of Hawai’i at Mānoa Library. https://doi.org/10.24251/HICSS.2020.199

- Bassano, C., Piciocchi, P., Spohrer, J., Jim, C., & Pietronudo, M. C. (2018). Managing value co-creation in consumer service systems within smart retail settings. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 45, 190–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2018.09.008

- Beckman, S., & Barry, M. (2007). Innovation as a learning process: Embedding design thinking. California Management Review, 50(1), 25–56. https://doi.org/10.2307/41166415

- Binkhorst, E., & Den Dekker, T. (2009). Agenda for co-creation tourism experience research. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 18(2–3), 311–327. https://doi.org/10.1080/19368620802594193

- Brown, T. (2009). Change by design: How design thinking transforms organizations and inspires innovation. HarperCollins e-books. https://books.google.com.co/books?id=x7PjWyVUoVAC

- Burrell, G., & Morgan, G. (1979). In Heineman (Ed.), Sociological paradigms and organisational analysis. Taylor & Francis.

- Cabrera, I., Villalon, J., & Chavez, J. (2017). Blending communities and team-based learning in a programming course. IEEE Transactions on Education, 60(4), 288–295. https://doi.org/10.1109/TE.2017.2698467

- Čaić, M., Odekerken-Schröder, G., & Mahr, D. (2018). Service robots: Value co-creation and co-destruction in elderly care networks. Journal of Service Management, 29(2), 178–205. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOSM-07-2017-0179

- Chan, H. C. B., Fung, T. T. (2020). Enhancing student learning through mobile learning groups. Proceedings of 2020 IEEE International Conference on Teaching, Assessment, and Learning for Engineering, TALE 2020 (pp. 99–105). https://doi.org/10.1109/TALE48869.2020.9368416

- Choi, E. K., Wilson, A., & Fowler, D. (2013). Exploring customer experiential components and the conceptual framework of customer experience, customer satisfaction, and actual behavior. Journal of Foodservice Business Research, 16(4), 347–358. https://doi.org/10.1080/15378020.2013.824263

- Clatworthy, S. D. (2011). Service innovation through touch-points: Development of an innovation toolkit for the first stages of new service development. International Journal of Design, 5(2), 15–28. http://www.ijdesign.org/index.php/IJDesign/article/view/939/343

- Culen, A. L., van Der Velden, M., Herstad, J. (2014). Travel experience cards: Capturing user experiences in public transportation. ACHI 2014 - 7th International Conference on Advances in Computer-Human Interactions (pp. 72–78). International Academy, Research, and Industry Association.

- De Gortari, E. (1968). Lógica General, Ciudad de México, La impresora azteca S. de R. L.

- Díaz-Méndez, M., & Gummesson, E. (2012). Value co-creation and university teaching quality: Consequences for the European Higher Education Area (EHEA). Journal of Service Management, 23(4), 571–592. https://doi.org/10.1108/09564231211260422

- Díaz-Méndez, M., Paredes, M. R., & Saren, M. (2019). Improving society by improving education through service-dominant logic: Reframing the role of students in higher education. Sustainability, 11(19), 5292. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11195292

- Dollinger, M., & Lodge, J. (2020). Student-staff co-creation in higher education: An evidence-informed model to support future design and implementation. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 42(5), 532–546. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2019.1663681

- Dollinger, M., Lodge, J., & Coates, H. (2018). Co-creation in higher education: Towards a conceptual model. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 28(2), 210–231. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841241.2018.1466756

- Dziewanowska, K. (2017). Value types in higher education–students’ perspective. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 39(3), 235–246. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2017.1299981

- Eikland Bækkelie, M. K. (2016). Service design implementation for innovation in the public sector. Proceedings of Nord Design, Nord Design 2016 (p. 1). Norwegian University of Science and Technology.

- Elnozahy, W. A., El Khayat, G. A., Cheniti-Belcadhi, L., & Said, B. (2019). Question answering system to support university students’ orientation, recruitment and retention. Procedia Computer Science, 164, 56–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2019.12.154

- Elsharnouby, T. H. (2015). Student co-creation behavior in higher education: The role of satisfaction with the university experience. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 25(2), 238–262. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841241.2015.1059919

- Fagerstrøm, A., & Ghinea, G. (2013). Co-creation of value in higher education: Using social network marketing in the recruitment of students. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 35(1), 45–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2013.748524

- Fleischman, D., Raciti, M., & Lawley, M. (2015). Degrees of co-creation: An exploratory study of perceptions of international students’ role in community engagement experiences. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 25(1), 85–103. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841241.2014.986254

- Grönroos, C. (2008). Service logic revisited: Who creates value? And who co‐creates? European Business Review, 20(4), 298–314. https://doi.org/10.1108/09555340810886585

- Grönroos, C., & Gummerus, J. (2014). The service revolution and its marketing implications: Service logic vs service-dominant logic. Managing Service Quality, 24(3), 206–229. https://doi.org/10.1108/MSQ-03-2014-0042

- Guilbault, M. (2016). Students as customers in higher education: Reframing the debate. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 26(2), 132–142. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841241.2016.1245234

- Gunarto, M., Hurriyati, R., Disman Wibowo, L. A., Natalisa, D. (2018). Building student satisfaction at private higher education through co-creation with experience value as intervening variables. Proceedings of the International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management (pp. 3116–3117), 2018-March. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85051544021&partnerID=40&md5=970e87fafa5977d1063f71d44d75a938

- Haenlein, M., & Kaplan, A. (2019). A brief history of artificial intelligence: On the past, present, and future of artificial intelligence. California Management Review, 61(4), 5–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/0008125619864925

- Holmes, W., Bialik, M., & Fadel, C. (2019). Artificial intelligence in education: Promises and implications for teaching and learning. Center for Curriculum Redesign.

- Hu, C., & Huang, J. (2023). An exploration of motivations for online identity reconstruction from the perspective of social learning theory. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2023.2212215

- Jeon, Y. (2022). Let me transfer you to our AI-based manager: Impact of manager-level job titles assigned to AI-based agents on marketing outcomes. Journal of Business Research, 145, 892–904. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2022.03.028

- Kim, J. (2019). Customers’ value co-creation with healthcare service network partners: The moderating effect of consumer vulnerability. Journal of Service Theory and Practice, 29(3), 309–328. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSTP-08-2018-0178

- Kim, J., Merrill, K., Xu, K., & Sellnow, D. D. (2020). My teacher is a machine: Understanding students’ perceptions of AI teaching assistants in online education. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, 36(20), 1902–1911. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2020.1801227

- Kim, J., Song, H., & Luo, W. (2016). Broadening the understanding of social presence: Implications and contributions to the mediated communication and online education. Computers in Human Behavior, 65, 672–679. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.07.009

- Kornbluh, M. (2015). Combatting challenges to establishing trustworthiness in qualitative research. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 12(4), 397–414. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2015.1021941

- Leite, A., Blanco, S. A. (2020). Effects of human vs. automatic feedback on students’ understanding of ai concepts and programming style. Annual Conference on Innovation and Technology in Computer Science Education, ITiCSE (pp. 44–50). https://doi.org/10.1145/3328778.3366921

- Li, P. P., & Wang, B. (2023). Artificial Intelligence in Music Education. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2023.2209984

- Li, S., Peng, G., Xing, F., Zhang, J., & Zhang, B. (2021). Value co-creation in industrial AI: The interactive role of B2B supplier, customer and technology provider. Industrial Marketing Management, 98, 105–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2021.07.015

- Libbrecht, P., Declerck, T., Schlippe, T., Mandl, T., Schiffner, D. (2020). NLP for student and teacher: Concept for an AI based information literacy tutoring system. CEUR Workshop Proceedings (pp. 2699). https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85097536435&partnerID=40&md5=1082c7d4edca83ffc72100f184489b74

- Lusch, R. F., Vargo, S. L., & Wessels, G. (2008). Toward a conceptual foundation for service science: Contributions from service-dominant logic. IBM Systems Journal, 47(1), 5–14. https://doi.org/10.1147/sj.471.0005

- Lusch, R. F., & Vargo, S. L. (2006). Service-dominant logic: Reactions, reflections and refinements. Marketing Theory, 6(3), 281–288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470593106066781

- Lv, W., Wang, Y. (2010). The influence of service design on public-perceived administrative service quality: The moderating effect of social monitoring. Proceedings of the International Conference on E-Business and E-Government, ICEE 2010 (pp. 2835–2838). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICEE.2010.716

- Ma, L., & Sun, B. (2020). Machine learning and AI in marketing – Connecting computing power to human insights. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 37(3), 481–504. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2020.04.005

- Macías Rodríguez, M. (2017). El camino para innovar. Barcelona, Deusto.

- Mandelli, A. (2011). Service industrialisation and beyond: Findings from a service networks project. International Journal of Engineering Management and Economics, 2(2–3), 132–152. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJEME.2011.041993

- Mandelli, A., & La Rocca, A. (2014). From service experiences to augmented service journeys: Digital technology and networks in consumer services. In E. Baglieri & U. Karmarkar (Eds.), Managing Consumer Services (pp. 151–190). Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-04289-3_9

- Manser Payne, E. H., Dahl, A. J., & Peltier, J. (2021). Digital servitization value co-creation framework for AI services: A research agenda for digital transformation in financial service ecosystems. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 15(2), 200–222. https://doi.org/10.1108/JRIM-12-2020-0252

- Matta, V., Bansal, G., Akakpo, F., Christian, S., Jain, S., Poggemann, D., Rousseau, J., & Ward, E. (2022). Diverse perspectives on bias in AI. Journal of Information Technology Case and Application Research, 24(2), 135–143. https://doi.org/10.1080/15228053.2022.2095776

- Molnár, G., Szüts, Z. (2018). The role of chatbots in formal education. 2018 IEEE 16th International Symposium on Intelligent Systems and Informatics (SISY) (pp. 197–202). https://doi.org/10.1109/SISY.2018.8524609

- Mostafa, R. B., & Kasamani, T. (2022). Antecedents and consequences of chatbot initial trust. European Journal of Marketing, 56(6), 1748–1771. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-02-2020-0084

- Mustak, M., Salminen, J., Plé, L., & Wirtz, J. (2021). Artificial intelligence in marketing: Topic modeling, scientometric analysis, and research agenda. Journal of Business Research, 124, 389–404. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.10.044

- Nguyen, L. T. K., Lin, T. M.-Y., & Lam, H. P. (2021). The role of co-creating value and its outcomes in higher education marketing. Sustainability, 13(12), 6724. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13126724

- Ondas, S., Pleva, M., Hladek, D. (2019). How chatbots can be involved in the education process. ICETA 2019 - 17th IEEE International Conference on Emerging ELearning Technologies and Applications, Proceedings (pp. 575–580). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICETA48886.2019.9040095

- Ozmen Garibay, O., Winslow, B., Andolina, S., Antona, M., Bodenschatz, A., Coursaris, C., Falco, G., Fiore, S. M., Garibay, I., Grieman, K., Havens, J. C., Jirotka, M., Kacorri, H., Karwowski, W., Kider, J., Konstan, J., Koon, S., Lopez-Gonzalez, M., Maifeld-Carucci, I., … Xu, W. (2023). Six human-centered artificial intelligence grand challenges. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, 39(3), 391–437. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2022.2153320

- Paredes, M. R. (2022). Students are not customers: Reframing student’s role in higher education through value co-creation and service-dominant logic BT. In E. Gummesson, M. Díaz-Méndez, & M. Saren (Eds.), Improving the evaluation of scholarly work: The application of service theory (pp. 31–44). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-17662-3_3

- Prakash, A. V., Das, S. (2020). Would you trust a bot for healthcare advice? An empirical investigation. Proceedings of the 24th Pacific Asia Conference on Information Systems: Information Systems (is) for the Future, PACIS 2020. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85089119483&partnerID=40&md5=a85b44bca05dcd7388c7dac8a250ccae

- Prebensen, N. K., Vittersø, J., & Dahl, T. I. (2013). Value co-creation significance of tourist resources. Annals of Tourism Research, 42, 240–261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2013.01.012

- Puntoni, S., Reczek, R. W., Giesler, M., & Botti, S. (2021). Consumers and artificial intelligence: An experiential perspective. Journal of Marketing, 85(1), 131–151. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022242920953847

- Rangaswamy, A., Moch, N., Felten, C., van Bruggen, G., Wieringa, J. E., & Wirtz, J. (2020). The role of marketing in digital business platforms. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 51(1), 72–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intmar.2020.04.006

- Ranjan, K. R., & Read, S. (2016). Value co-creation: Concept and measurement. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 44(3), 290–315. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0397-2

- Ranoliya, B. R., Raghuwanshi, N., Singh, S. (2017). Chatbot for university related FAQs. International Conference on Advances in Computing, Communications and Informatics (ICACCI) (pp. 1525–1530). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICACCI.2017.8126057

- Rivera, A. C., Tapia-Leon, M., Lujan-Mora, S. (2018). Recommendation systems in education: A systematic mapping study BT. In Á. Rocha & T. Guarda (Eds.), Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Technology & Systems (ICITS 2018) (pp. 937–947). Springer International Publishing.

- Robayo-Pinzon, O., Foxall, G. R., Montoya-Restrepo, L. A., & Rojas-Berrio, S. (2021). Does excessive use of smartphones and apps make us more impulsive? An approach from behavioural economics. Heliyon, 7(2), e06104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e06104

- Rust, R. T. (2020). The future of marketing. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 37(1), 15–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2019.08.002

- Sanders, E. B. N. (2000). Generative tools for co designing. Collaborative design (pp. 3–12). Springer-Verlag London Limited.

- Sandu, N., Gide, E. (2019). Adoption of AI-chatbots to enhance student learning experience in higher education in India. 2019 18th International Conference on Information Technology Based Higher Education and Training, ITHET 2019. https://doi.org/10.1109/ITHET46829.2019.8937382

- Schiessl, D., Dias, H. B. A., & Korelo, J. C. (2022). Artificial intelligence in marketing: A network analysis and future agenda. Journal of Marketing Analytics, 10(3), 207–218. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41270-021-00143-6

- Sklyar, A., Kowalkowski, C., Tronvoll, B., & Sörhammar, D. (2019). Organizing for digital servitization: A service ecosystem perspective. Journal of Business Research, 104, 450–460. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.02.012

- Smørvik, K. K., & Vespestad, M. K. (2020). Bridging marketing and higher education: Resource integration, co-creation and student learning. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 30(2), 256–270. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841241.2020.1728465

- Sökmen, Y., Sarikaya, İ., & Nalçacı, A. (2023). The effect of augmented reality technology on primary school students’ achievement, attitudes towards the course, attitudes towards technology, and participation in classroom activities. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2023.2204270

- Steinbeck, R. (2011). Building creative competence in globally distributed courses through design thinking. Comunicar, 19(37), 27–35. https://doi.org/10.3916/C37-2011-02-02

- Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1994). Grounded theory methodology: An overview. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (pp. 273–285). Sage Publications, Inc.

- Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (2008). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. In Basics of qualitative research grounded theory procedures and techniques (Vol. 3). Sage Publications Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452230153

- Sweeney, J. C., Danaher, T. S., & McColl-Kennedy, J. R. (2015). Customer effort in value cocreation activities: Improving quality of life and behavioral intentions of health care customers. Journal of Service Research, 18(3), 318–335. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670515572128

- Tøndel, M., Kiønig, L., Schult, I., Holen, S., Vold, T. (2018). Students as co-developers of courses in higher education. Proceedings of the International Conference on E-Learning (pp. 448–453). 2018-July, ICEL https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85050818600&partnerID=40&md5=685be5ae632a7f5f495aaae39d973af2

- Troussas, C., Krouska, A., Alepis, E., & Virvou, M. (2020). Intelligent and adaptive tutoring through a social network for higher education. New Review of Hypermedia and Multimedia, 26(3–4), 138–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/13614568.2021.1908436

- Uribe-Saldarriaga, C. M., Ortiz-Pradilla, T., & Echeverry-Gómez, S. (2022). What if? A robot challenge in a marketing course: An abstract. In F. Pantoja & S. Wu (Eds.), From Micro to Macro: Dealing with Uncertainties in the Global Marketplace. AMSAC 2020. Developments in marketing science: Proceedings of the academy of marketing science (pp. 531–532). Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-89883-0_141

- Vargo, S. L., Akaka, M. A., & Vaughan, C. M. (2017). Conceptualizing value: A service-ecosystem view. Journal of Creating Value, 3(2), 117–124. https://doi.org/10.1177/2394964317732861

- Vargo, S. L., & Lusch, R. F. (2004). Evolving to a new dominant logic for marketing. Journal of Marketing, 68(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.68.1.1.24036

- Vargo, S. L., & Lusch, R. F. (2017). Service-dominant logic 2025. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 34(1), 46–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2016.11.001

- Xie, Z., Yu, Y., Zhang, J., & Chen, M. (2022). The searching artificial intelligence: Consumers show less aversion to algorithm-recommended search product. Psychology & Marketing, 39(10), 1902–1919. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21706