Abstract

Gamification has arguably emerged as the most dominant of persuasive technologies, giving rise to a multidisciplinary field and diverse associated industries. As the field has grown, so too has the need for further resolution, nuance, and conceptual acuity; it is important to be able to distinguish different facets once the use of umbrella terminology becomes insufficient. One notable area of interest is gamblification, the study of which is not yet as well-developed; while gamblification is often conceptualized as an extension of gamification, recent research has found it to be an effective means of engaging users in alternative ways. This article examines points of similarity and difference between gamblification and gamification, with the intention to highlight the scope of gamblification as a means to promote specific user behavior and, furthermore, to provide a clear theoretical basis for the ongoing investigation into this phenomenon. The most significant point of difference is that while successful gamification primarily utilizes intrinsic motivations to effect meaningful change, gamblification does so predominantly through leveraging extrinsic motivations. Consequently, gamification and gamblification are used to achieve different aims and are suited to different contexts. Finally, a future research agenda for developing the study of gamblification is presented.

1. Introduction

Gambling, games, and gamification are widely investigated phenomena, attracting significant attention both in research and practice (Guo et al., Citation2019; Koivisto & Hamari, Citation2019; Tobon et al., Citation2020). Yet little is known about how the associated phenomenon of gamblification (Macey & Hamari, Citation2022) is employed and how it may affect user behavior. This comes as a surprise because gamblification has been subject to political criticism, restrictions, and policies (Macey & Hamari, Citation2019a; Zendle et al., Citation2020). Indeed, the current conversation on gambling and gamblification has traditionally been on the dark and problematic side, such as on the ways in which reward uncertainty contributes to problem gambling and addiction (Binde, Citation2009; Robinson & Berridge, Citation2001; Zack et al., Citation2020). Yet, more recent research on gamblification has increasingly opened up to investigate the motivating effects of gambling-related activities (Shen et al., Citation2015, Citation2019). Moreover, gamblification is also linked to a huge financial success that is equal to or even surpasses that of gamification, with revenue generated by loot boxes on digital platforms forecast to rise from $15bn in 2020 to $20bn in 2025 (Juniper Research, Citation2021) (see e.g., Ma et al., Citation2014; Stehmann, Citation2020; Tobon et al., Citation2020; Zanescu et al., Citation2020). This huge financial success is mainly thanks to its wide and prevalent application in commercial contexts as a means of monetizing products and services and, thus, to increase revenue generations.

While gamblification has been gathering more attention in recent years, there is a distinct lack of conceptual clarity in approaches, for example, Social Sciences and Media Studies tend to view it as a distinct entity with notable, and growing, influence particularly in digital culture (Brock & Johnson, Citation2021; Lopez-Gonzalez & Griffiths, Citation2018; Zanescu et al., Citation2021). Alternatively, the dominant view in Information Studies and HCI is that it is simply an extension of gamification (Adam et al., Citation2023; Norsk Pantelotteri AS, Citation2023; Reinelt et al., Citation2021), however, some acknowledge sufficient dissimilarities and distinctions to merit consideration as separate processes (Benner et al., Citation2022). This issue is significant as the motivations gratified by gamification and gamblification are likely to differ in the same way as between games and gambling. Accordingly, the two concepts are unlikely to be equally appropriate means of achieving desired behavioral changes, especially so when considering the different contexts in which they are applied, for example, education, marketing, workplace productivity, and so on.

Gamblification can be seen to offer a distinct and novel value proposal that goes beyond gamification. The concept of reward uncertainty in particular opens the door for new and unexplored decision-making biases, which can evolve into powerful cognitive distortions regarding the nature of randomness and the degree of control over obtaining rewards (Clark, Citation2014). This assertion is consistent with recent work discussing the appeal of slot machines due to the combination of “machine design features” (e.g., near misses) and “human design features” (e.g., a human’s susceptibility to illusory control) (Clark et al., Citation2019).

Gamification has explicitly been connected to the growing importance of games contemporary societies, whether this be economically or socio-culturally, this has variously been dubbed “the gamification of society” (Devisch et al., Citation2016), the “ludification of culture” (Raessens, Citation2006), or the “ludic turn” (Sutton-Smith, Citation1997). While gamblification can also be argued to be connected to the same ludic turn, it is more closely associated with attitudinal shifts toward money and financial systems described as “casino capitalism.” That is, individuals and societies are increasingly tolerant of approaches in which financial resources are no longer viewed as fixed or stable but are instead volatile and unpredictable (Strange & Watson, Citation2016). Furthermore, gamblification can also be seen as an extension of ideals that celebrate individuality, risk, and excess in Western culture, primarily those values extolled and exported by the US in the 20th century (Abt et al., Citation1984; Smith & Abt, Citation1984).

This article intends to shed light on the scope and relevance of the emerging research topic of gamblification and to examine points of similarity and difference with respect to the established topic of gamification. Achieving this aim will provide a clear theoretical basis for ongoing investigation of gamblification, a phenomenon that has potentially significant social and economic impact. To achieve this aim, gamblification and gamification will be introduced individually before examining the theoretical grounding and practical implementations of the two. Finally, the implications of this work will be discussed, and a future research agenda for gamblification is presented.

2. Understanding gamification and gamblification

2.1. Gamification

Gamification is variously referred to as a process, a tool, a phenomenon, a means of exploitation, or an interpretive lens; such diverse approaches speak to the complexity of the topic, while also reflecting the varied motivations and both theoretical and political perspectives of those that use the term (Fuchs, Citation2014; Thibault & Hamari, Citation2021). The study of gamification has evolved over the past decade, not only reflecting a range of ideological positions but also expanding across multiple domains, from health and wellness to logistics (Koivisto & Hamari, Citation2019). At the same time, it has suffered as a result of misunderstandings and misapplications, as well as from opportunistic and simplistic exploitation exemplified by a focus on points, leaderboards, and badges over all else (Chou, Citation2019).

At heart, the principles of gamification concern the intentional generation of gameful experiences and interactions in non-game contexts, this can be with the aim of motivating specific behaviors, of achieving certain goals, or of enhancing experiences of a product or an activity (Huotari & Hamari, Citation2012; Nacke & Deterding, Citation2017). In a nutshell, gameful approaches are used to enhance more functional activities or experiences, thereby making them more engaging and more desirable. The popularity of gamification, as a topic both within and outside academia, is a reflection of the “ludic turn” observed in contemporary industrialized societies, although behaviors commonly associated with gamification have existed for much longer (Fuchs, Citation2014).

To ensure clarity for the reader, this research will adopt the conceptual framework of gamification as a technique used to motivate individual behaviors or goal attainment. This approach has been chosen for two main reasons: first, that it reflects the bulk of research and practice in the field of gamification; second, that it ensures the possibility of direct and meaningful comparison with gamblification.

A wealth of literature exists that is dedicated to the more prosaic aspect of gamification, that is the creation of taxonomies for identifying game elements, mechanics, and design principles (Koivisto & Hamari, Citation2019; Krath & On Korflesch, Citation2021). Similarly, diverse attempts to explain the motivational powers underpinning gamification have made use of such theoretical perspectives as self-determination, goal-setting, situational relevance, and behavioral reinforcement to name but a few (see, e.g. Landers, Citation2014; Seaborn & Fels, Citation2015). Despite the competing theories attempting to explain gamification, it is commonly accepted that the primary driver of successful gamification is the effective leveraging of intrinsic motivations over extrinsic, although both can feature (Hamari, Citation2017).

2.2. Gamblification

Gamblification, vis-à-vis gamification, is situated similarly as gambling is to gaming, thereby implying that in the same way that the etymological and symbolic roots of gamification lie in gaming, gambling is the anchor for gamblification. Specifically, as gamification employs the mechanics and aesthetics of games to motivate certain behaviors, gamblification utilizes the aspects of gambling products, services, systems, and culture.

Originally, the term gamblification was coined to describe the association of gambling with sports or cultural events as a vehicle for promoting increased acceptance and normalization of gambling (e.g., advertising during televised coverage of sporting events, either for real-time, in-play betting markets, or alternative products, such as online poker) (McMullan & Miller, Citation2008). Subsequently, this combination of gambling with other consumable content was transferred particularly to digital environments, such as social networks (Morgan Stanley, Citation2012), esports (Lopez-Gonzalez et al., Citation2019; Macey & Hamari, Citation2019a; McGee, Citation2020), online games (Abarbanel & Johnson, Citation2020; Macey & Hamari, Citation2020). More recently, the term has become more widespread and has been broadened to comprise not only the incorporation of full-fledged gambling but also the incorporation of individual gambling design elements specifically (Abarbanel & Johnson, Citation2020; James et al., Citation2017). In contrast to gamification, the primary driver of successful gamblification is associated with extrinsic motivations, i.e., rewards; while intrinsic motivations, such as excitement and curiosity are also employed, they are leveraged through association with extrinsic rewards (Adam et al., Citation2023). Recent work has united these disparate uses by identifying two primary types of gamblification, effective and affective, each of which consisted of two sub-types. In summary, the first refers to the incorporation of gambling into activities where it is not traditionally present, while the second refers to the use of gambling imagery and cultural references to induce affective reactions (Macey & Hamari, Citation2022).

Beyond these aspects of gamblification, further characteristics can be considered, such as motivational drivers, in that gamblification may encourage participation by capitalizing on the motivations which, to varying degrees, drive participation in gambling activities (e.g., the chance of winning; the potential to win big; social rewards; intellectual challenge; mood change (Binde, Citation2013). Moreover, further approaches and tools can be used to define the degree of gamblification employed, such as through the design of stakes, rewards, volatility of utility value, etc. (see Macey et al., Citation2024).

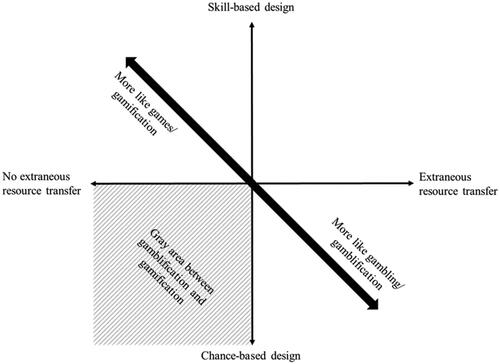

It is reasonable to consider that a design can be evaluated in terms of how little or how much it is characteristic of gambling, and therefore, whether it is more or less gamblified. At the fully-fledged end of gamblification (effective—full fidelity), it not only consists of gambling game design elements and related chance-based mechanisms but, furthermore, incorporates resource transfer mechanisms. The resource transfer can also be considered a significant differentiating aspect between gamblification and gamification; games (the inspiration for gamification) are focused on non-consequential activities provoking intrinsic motivation (Koivisto & Hamari, Citation2019). In other words, gamblification without resource transfer (affective gamblification) is positioned in a grey area between gamblification and gamification. See (above) for a visualization of one potential approach to disentangle gamblification from gamification.

3. From games and gambling to gamification and gamblification

A game usually refers to systems in which players engage in an activity, resulting in a quantifiable outcome (Salen & Zimmerman, Citation2003; Stenros, Citation2017). These outcomes are often skill-based (e.g., in the game of chess outcomes are determined by skills, such as imagination or strategic thinking). In case they are not predominantly skill-based, they are chance-based (e.g., lotteries) and hence rely on reward uncertainty as a central motivational driver for player engagement (Clark, Citation2014; Zack et al., Citation2020). A particularly prevalent form of these chance-based games are gambling games (e.g., blackjack, craps).

Games, game play, and gambling have always been closely interlinked, and until the 20th century, they were essentially synonyms. A wealth of evidence exists for the presence of games of chance across many human societies across many millennia, with the oldest example of a board game with written rules currently known, the Royal Game of Ur, dates from around 2700 B.C. and is thought to have been not only played for entertainment but also used for divination and gambling (Pfeiffer & Sedlecky, Citation2020). Indeed, the development of “gaming” in classical cultures has been speculated as constituting an idealized form of chance-based game play which, in turn, arose from practices of fortune-telling and from religious rituals (David, Citation1998).

Games, whether competitive or ritual require rules in order that participants know their roles and that outcomes are considered legitimate. While many contemporary games and sports have their origins in popular folk formats, their modern forms are far removed from those practised centuries ago. Essentially, the rules and practices of games varied according to locality, meaning competition between rival teams was problematic and results could be disputed. Consequently, the official rules and regulations were formalized and documented, enabling not only inter-locale play but, more significantly, the ability to wager on the outcome of matches without results being contested. Indeed, the more closely an activity was associated with gambling, the earlier that commonly agreed rules were adopted (Vamplew, Citation2007). The connection between sports and gambling is present across many levels, and prior to professionalization gambling was often the only source of income for athletes, with the terms “sportsman” an “gambler” being used interchangeably as recently as the early 1900s (Ferentzy et al., Citation2013).

Gaming, therefore, appears to be more closely associated with games of chance, while gambling more closely associated with games of skill. In an apparent reversal of this linguistic association, contemporary cultural usage of gaming and “gamer” refers to the play of digital games in which skill is predominant, while gambling is used to denote legally-defined activities in which participants may profit or lose a stake with the outcome being defined by uncertainty. As an extension of this last point, gambling is also used in more general terms to refer to situations characterised by risk (Abarbanel, Citation2018).

A recent corpus linguistic study revealed that the first recorded use of “gaming” in English occurred ∼200 years before “gambling,” and was used more frequently until the mid-1800s. The changing preference was linked to the era of the gold rush in California, both in terms of the nature of the gold rush as a socio-historical event and the leisure activities of the gold miners. Finally, “gaming” was found to have undergone a relatively recent resurgence, with usage of the term rising sharply in the 1990s and continuing on an upward trend. This is explained by twin factors, first an effective attempt to rebrand gambling, both by industry and governments, and second, by the rise of digital games (also “video games” and “computer games”) as a leisure activity and an ever-growing social, cultural, and economic force (Li et al., Citation2020). In an interesting point highlighting the inter-connectedness of these concepts, the term “whale” used in the digital game industry to denote a high-paying player of free-to-play games was co-opted from the gambling industry (Barsky, Citation2018; Cassidy, Citation2013).

Gambling, thus, is positioned as a specialized form of games, additionally, to fully constitute gambling a resource transfer is necessary. Since the conceptual origin of gamification and gamblification stem from games and gambling, respectively, we illustrate the common and divergent characteristics between gambling and games in .

Table 1. Comparison of gambling and games.

Although some studies have implicitly devoted attention to gamblification (Grange et al., Citation2019; McCay-Peet & Toms, Citation2022), little is known about how gamblification is employed and how it may affect user behavior. The large neglect of gamblification, outside research informed by gambling studies, is likely because (1) gambling is usually associated with moralistic attitudes and negative effects on users (e.g., addiction, loss of control, suffering), and which is even under regulatory control in traditional offline and online settings (Cotte & Latour, Citation2009; Hou et al., Citation2019; Ma et al., Citation2014); and (2) uncertainty, a key characteristic of gambling in the form of chance, is broadly treated by HCI and IS research in particular as a phenomenon that needs to be avoided or at least reduced (Dimoka et al., Citation2012; Hong & Pavlou, Citation2014; Pavlou et al., Citation2007). Indeed, the general avoidance of uncertainty in gamification literature can be seen in the inconsistent terminology and various definitions for rewards, in that only chance-based rewards have often been classified as uncertain rewards (Bui et al., Citation2015; Koivisto & Hamari, Citation2019), although even skill-related rewards are to some agree degree uncertain (Malone, Citation1981).

This inconsistency in the definition may also potentially explain the inconsistencies found in research and practice on the success of gamification (Tobon et al., Citation2020). Nevertheless, recent research in related fields has cast doubt on these opinions and even demonstrated the hidden value of reward uncertainty, in that chance-based (vs. certain) rewards can indeed increase resource investment and enforce repetitions due to increased motivation (Shen et al., Citation2015, Citation2019). Thus, this chance-based mechanism is likely to be utilized and reach its full potential via gamblification, rather than in pure gamification contexts. Yet, there is only minimal research that has brought gamblification and its effects to the forefront of its investigations.

Both gamification and gamblification can draw on the same pool of theories from IS, from HCI, and other related fields (e.g., behavioral economics, marketing, psychology) to inform their research. For instance, both the design of incentives and the setting of optimal rewards can draw on research regarding the utility of gambling (Conlisk, Citation1993; Diecidue et al., Citation2004) or on behavioral economics, such as prospect theory (Kahneman & Tversky, Citation1979). On the other hand, to address motivation, research on gamblification and gamification can draw on theories from psychology, such as flow theory (Davis & Csikszentmihalyi, Citation1977) and self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, Citation2017). For example, it may provide important insights to investigate whether situational or long-term facets of gamblification are more important in driving motivation through the fulfillment of needs (e.g., competence, autonomy, arousal) compared to gamification.

However, in contrast to more commonplace gamification, gamblification usually involves resource transfer (i.e., a “real-world” reward). It is important to note that gamification seeks to utilize game elements and rhetoric to induce a sense of gamefulness, it does not necessarily seek to recreate games within other systems or services. The same is true in regard to gamblification; while the potential for participants to suffer a loss is axiomatic of gambling, it is not a requisite of gamblification. Indeed, any transfer of resources that takes place within gamblified systems or services can incorporate financial, virtual, or even intangible assets (Macey & Hamari, Citation2022).

Whereas gamification is more concerned with affecting user engagement by adapting the target systems through provision of affordances for the emergence of motivation (e.g., autonomy, competence, social relatedness) (Xi & Hamari, Citation2019), gamblification additionally invokes motivation by introducing “real world” consequences in terms of rewards (e.g., Starbucks introducing an augmented reality lottery, providing users the prospect to win money-equivalent rewards) (Macey & Hamari, Citation2022; Starbucks, Citation2021). Thus, while many overall designs may be gamblified, and generally have characteristics of gambling, in order for a design to be considered full-fledged gamblification, it not only requires specific game design elements and related chance-based mechanisms but further, on top of gamification, it typically also involves a resource-transfer. This differentiation gives gamblification a distinct and unprecedented value proposal beyond mere gamification and introduces additional complexities and unique challenges in designing systems. For instance, one possible dynamic in gamification is the enabling of competition with other players (Liu et al., Citation2013, Citation2019). With the introduction of gamblification, and the focus on chance-based (i.e., random) rewards and related affordances in particular, however, these assumptions are likely to no longer hold true in gamblification. Specifically, chance-based rewards do not provide the necessary feedback about one’s competence, and competition with others predominantly based on “luck” is unlikely to be motivating. Yet, vast findings on gambling in research and practice strongly indicate that people not only accept but also seek chance-based rewards, being potentially even more engaging and consequential than game design elements due to higher affective appeals (e.g., motivation, excitement, enjoyment) (Shen et al., Citation2015, Citation2019) and the process utility of gambling (Bailey et al., Citation1980; Le Menestrel, Citation2001).

Given these characteristics of gamblification, we argue that it is an approach which, although conceptually similar to gamification, is one which has sufficient unique characteristics that it can be considered separate, and which requires further conceptual development in order for it and gamification be meaningfully discussed and distinguished in future research. Furthermore, while gamblification and gamification both draw on specific game design elements to shape user experiences and drive user engagement, their success is dependent upon gratifying different primary motivational drivers and, therefore, suited to different implementations.

3.1. Ethical issues

Gamification and gamblification are also related to persuasive design (Fogg, Citation2002) in that they are employed to motivate particular behaviors on the part of users, both beneficial and detrimental (Benner et al., Citation2022). As such, there are certain ethical considerations that arise as a consequence of their use, for example, typical questions that are asked include who benefits from the resultant behavioral change, and do users have the ability to opt-out of such systems? Criticisms of gamification tend to have focused on its misuse, or the degree to which it exploits individuals’ motivations by leading individuals to behave in ways not suited to their best interests, particularly in workplace-related situations, such as gamified productivity applications (Kim & Werbach, Citation2016; Woodcock & Johnson, Citation2018). Indeed, concerns about the top-down application of gamification have resulted in recent calls for it to reclaim its “punk” roots as a means of challenging the status quo and increasing individual autonomy (Thibault & Hamari, Citation2021).

Ethical considerations around gamblification are focused more on the potential for normalizing gambling as an activity, and for encouraging individuals to seek out “deviant” leisure practices, and a preference for chance-based rewards (Johnson & Brock, Citation2020; McMullan & Miller, Citation2008; Raymen & Smith, Citation2020). Conversely, systems ostensibly designed to enhance user engagement have been criticized as being akin to gambling, resulting in negative financial and psychological consequences for users who have no choice but to participate (Vieira, Citation2023). Furthermore, there is concern that individuals are being encouraged to participate in activities for which they are not being fairly compensated, for example in situations where companies collect personal data as conditions for receiving a chance-based reward. Such practices raise issues around transparency, information asymmetry, and the value consideration of non-tangible or virtual resources (Macey & Hamari, Citation2022).

While both gamblification and gamification share similar issues of concern about potential user exploitation, the specific focus of each is somewhat different. Gamification has the potential to induce users into behaviours and practices potentially detrimental to their long-term well-being or are otherwise emotionally damaging, while gamblification has the potential to induce loss of personal resources, financial or non-tangible. Both feature hazards of opaqueness, information asymmetry, and deceit between the implementing party and the user (Al-Msallam et al., Citation2023).

Given the roots of gamification and gamblification it would also be productive to consider extant research which examines the potential harms of these two activities, especially in light of the transfer of resources that sets gamblification apart from gamification. A significant body of research exists investigating the negative consequences arising from disordered or potentially problematic consumption of both gambling and gaming, with the latter being developed from the former. Concepts of harm and the ways in which they manifest can vary, but commonly include financial, psychological, physical, social/cultural, work or study-based, and in the most extreme cases, criminal activity (Langham et al., Citation2015).

A recent work compared harms experienced by comparable samples of gamblers and game players whose consumption practices were categorized as being problematic, finding that there were clear differences between the two groups. Most notably, problematic gamblers were found to experience a wider range of both harms and severity of harm than pathological gamers. Furthermore, while both groups reported experiencing a range of harms, the particular types experienced by each were distinct, with gamblers experiencing more severe financial and psychological harms, whereas gamers experienced greater harms related to physical health (Delfabbro et al., Citation2021). Together, these findings support the distinct concerns related to gamification and gamblification outlined previously and highlight the particular potential for unethical gamblification to result in negative financial consequences for some users, as illustrated by mainstream media reports of problematic spending on loot boxes, for example.

4. Common applications of gamblification and gamification

In the following section, we pinpoint four prevalent forms to provide a more illustrative understanding of gamblification:

4.1. Making a certain resource transfer (e.g., exchange, transaction, gifting) uncertain

The easiest implementable type is to transform certain transactions into chance-based ones; valuable rewards and stakes already implicitly exist in every transaction and only the mechanism of chance-based uncertainty has to be introduced. For instance, in many online games simple transactions have been gamblified to increase user engagement, revenues, and profits by offering chance-based content instead of previously certain content (e.g., League of Legends and Counter-Strike) (Steam, Citation2021; whatacoolwitch, Citation2023). The associated emergence of loot boxes (i.e., virtual goods that contain random selections of other virtual goods) on digital platforms has paved the way for new forms of monetization, thereby influencing various digital business models, supplementing their traditional revenue streams with innovative monetization strategies (Veit et al., Citation2014). As such, the replacement of certain rewards with chance-based rewards have turned simple transactions into recurring gambling activities (Griffiths, Citation2018; King & Delfabbro, Citation2019; Macey & Hamari, Citation2019b). In fact, global spending on these gamblified rewards in online games alone is estimated to have reached over $15bn in 2020, equal to more than one-fifth of the total gaming market, and is expected to grow to in excess of $20bn by 2025 (Juniper Research, Citation2021). Another example is fostering pro-environmental behavior (e.g., improving resource conservation): By giving the opportunity to choose a lottery entry in place of a refund, a Norwegian company (Norsk Pantelotteri AS, Citation2023) has turned bottle recycling machines into bottle recycling “slot “machines. This gamblification is associated with not only more user-recycled bottles but also simultaneously reduced the overall amount of refunds. A further example is donating “surprise” gifts (e.g., loot boxes) which can be purchased by users and transferred to streamers on live streaming platforms to support streamers. These gifts often include random rewards (i.e., neither the user nor the streamer knows what form the gift takes before opening) (Abarbanel & Johnson, Citation2020).

4.2. Providing gamblification design elements in addition to existing products and services

This type of gamblification focuses on enhancing pre-existing conditions, under which a user interacts and considers achieving an instrumental outcome (e.g., the overall product and service agreement under which a user decides to transact with a seller). Hereby, the original price of the product and/or service agreement often stays the same and the additional costs are covered by the additional revenues generated through the appeal of gamblification. For instance, Starbuck’s Starland is an augmented reality lottery, which is offered as a bonus to its customers, thus rewarding users for the purchase of one of their products (Starbucks, Citation2021); Google Pay offers scratch cards after users top up their credit accounts, allowing them to gain additional benefits (Google, Citation2023); and Twitch.tv allows subscribers to take part in raffles organized by streamers, “resulting in a long-term potential that these gambling design elements may serve as a normalization (and later, migration) platform for ‘fully’ gambling activities” (Abarbanel & Johnson, Citation2020). The last example is improving civic-minded behavior (e.g., reducing fare-dodging) by turning bus ticket vending machines into bus “lottery “ticket vending machines, so that users receive a lottery ticket on top of a simple purchase of a bus ticket (Fabbri et al., Citation2019).

4.3. Placing bets on one’s and other’s behavior

This type of gamblification focuses more on skill and self-efficacy but is still predominantly focused on chance-based outcomes. Hereby, particularly the consequentiality of the uncertain actions change (and not necessarily the uncertainty of the main goal). For instance, Waybetter is a digital platform that allows users to join games in which they can bet on their own skill-related behavior by placing stakes (i.e., money) into a community pot to increase their motivation to achieve a bet-upon outcome (e.g., running a marathon, eating healthy, losing weight, quitting smoking) (WayBetter, Citation2023). At the same time, they bet that other, similar participants are not able to reach the same goal in the same time period, a situation mainly driven by chance, or at least out of the control of the individual. The participants who reach the agreed-upon goal split the pot while the others lose their stake. More than 1.4 million people are currently signed up to Waybetter and, for example, have collectively lost more than 14 million pounds (lbs.) in weight (WayBetter, Citation2023), however, these types of services are coming under increased scrutiny (Lexel, Citation2019).

4.4. Using gambling imagery, terminology, and to increase positive affect

This type of gamblification focuses not on the transfer of resources, but on rewards of more intangible nature; interactions are framed in such a way as to reference the gratifications afforded by gambling, in particular successful gambles. For example, terms, such as “high roller” are unequivocally associated with gambling and are used to convey images of a luxurious lifestyle beyond normal reach. The “no-frills” airline company JetBlue released advertising for a new transatlantic service with the tagline “fly like a high roller without spending like one” (McNeill, Citation2023), thereby emphasizing the kind of grandiose experiences associated with those who can afford to gamble with large amounts of money. Furthermore, this form of gamblification is used to support other forms (see 4.1 and 4.2, above) as it uses presentational techniques pioneered in the gambling industry to increase impact on users. While some contemporary digital games distribute random rewards via loot boxes, others do so with more explicit replications of gambling. The free-to-play game Stumble Guys (Scopely, Citation2023) makes cosmetic skins available to players via a “lucky wheel,” a direct replication of the “wheel of fortune” game complete with “near misses” (Clark et al., Citation2013, Citation2009) and maximizing the period of uncertainty (Anselme & Robinson, Citation2013). Indeed, prior research has shown that supplementing random rewards with audio-visual references associated with gambling increases user appeal and encourages riskier behavior (Cherkasova et al., Citation2018; Kao, Citation2020). Finally, as the specific practices of gamification have been associated with the wider impact of games in society, the practice of gamblification is increasing alongside the growing presence of gambling, most notably in the context of sports and video games (Macey & Hamari, Citation2022).

Given these examples, gamblification is not only linked to revenues that surpass the $9 billion investment in gamification in 2020 (Markets & Markets, Citation2022) but is also likely to have wide-ranging applicability, as many providers can gamblify their systems to promote desired behavior. provides examples of how gamblification and gamification are used in particular application contexts, thereby highlighting how the relevant characteristics of each are suited to different implementations.

Table 2. Example applications of gamblification and gamification.

The table above highlights how gamification and gamblification are employed across a range of contexts, it is not an extensive list of all domains but rather those where examples of both gamification and gamblification can be found, furthermore it highlights the different motivations that are gratified. Chief among these differences is that the primary driver of Gamblification is often extrinsic motivation and, therefore, is more suited to effecting short-term goals. Consequently, the focus on short-term goals and extrinsic motivations mean that gamblification is not suitable for use across all contexts. In particular, the learning and education example in , above, highlights the different effects of gamblification and gamification in the same context. Gamified education seeks to improve students’ levels of attainment by supporting and reinforcing learning. However, the example of gamblified education does not necessarily require that the students directly engage with the course, and their success in the task is not linked to any educational attainment. While knowledge of both the political context, and the practicalities of the US system is undoubtedly beneficial, the result is not connected to, or influenced by, the interaction. Indeed, the potential pitfalls of introducing gamblification to educational settings have been raised in prior works (Palmquist et al., Citation2021). The workplace productivity example also highlights the potential negative impact of applying gamblification to certain contexts, with the variable payment structures, which are not known before accepting a job, resulting in negative consequences (financial and psychological) for workers (Dubal, Citation2023; Vieira, Citation2023).

As with gamification, it can be useful to conceptualize gamblification using a design process model, as such gamification science (Hamari et al., Citation2014; Huotari & Hamari, Citation2017) and the gamification framework and terms by Liu et al. (Citation2017) offer a sound basis for describing gamblification design elements.

Gamblification may be realized in the following way: designing interactions that incorporate uncertain rewards and/or gambling references. To make this incorporation of reward uncertainty more tangible and actionable for researchers and practitioners, we preliminary suggest considering gamblification as designing through the utilization of gambling design elements (see Liu et al., Citation2017). Gambling design elements hereby refer to:

specific gambling game design objects and corresponding affordances (e.g., roulette wheel, dice, scratch cards).

related game design mechanics in the form of chance-based mechanisms and related principles (i.e., outcomes are mainly determined by rules of probability and randomness).

resource transfers (i.e., stakes and/or rewards with objective value which are transferred either from the user to the target system and/or from the target system to the user).

The gamblification design elements identified above are characteristic but not necessarily unique to gamblification. For instance, dice are chance-based objects that are frequently used as essential components in gambling games used for gambling (e.g., Craps, Under & Over 7) to determine the winning of a reward but are also frequently and essentially interwoven into regular games (e.g., Monopoly, Backgammon). In games, however, these design elements and chance-based mechanisms serve a different purpose, namely, to fulfill the role of introducing variety and challenge into the game, thus testing how players deal with chance. As such, skill, and competition—and thus some of the most frequently associated characteristics of a game—are still mainly intact and dominant when dice are employed in games.

Conversely, and more interestingly, many typical game design elements are found in gambling games, often with a different purpose. For instance, leaderboards are one of the hallmarks of game design elements (Khan et al., Citation2020; Liu et al., Citation2017). As such, displaying the best players in a leaderboard in gamified systems is intended to provide feedback to players about their skills, to provide social comparisons, and to foster competition. In a gamblified system, however, a leaderboard with the best players does not communicate information about the leader’s or the user’s skills (because winning a chance-based reward is not skill-related). Instead, it is more likely used to highlight that winning the most desirable chance-based rewards is possible, thus rather intended to fuel a user’s ambitions (Kahneman & Tversky, Citation1979; Tversky & Kahneman, Citation1974). Another example is that of points: whereas points in games can only be exchanged for contextualized goods and services that have little to no value outside of the ecosystem (e.g., “play money”), points in gambling games are almost always related to acquiring real-world money, products, and services. As such, points can be applied both in gamification and gamblification, but have different values depending on the contexts and their pairing with other design elements (i.e., objective vs. contextual rewards). The aspect of real-world value is characteristic of gambling and bears potentially different consequences for achieving outcomes. Therefore, particularly contextualization of typical and already investigated “game” design elements in the emerging context of gamblification promises various fruitful avenues and new theory generation for future research.

5. Implications and directions for future research on gamblification

This research aimed to examine the concepts and practices related to gamblification, and to examine them in reference to the more established concept of gamification. Considering previous research, it becomes evident that research on gamblification has provided largely high-level phenomenological insights (Abarbanel & Johnson, Citation2020; Johnson, Citation2019; Macey & Hamari, Citation2020) and has recently often implicitly been addressed in IS research and management research (Chen et al., Citation2020; Lichtenberg & Brendel, Citation2020; Roethke et al., Citation2020). Yet questions specific to gamblification still need to be addressed. For example, attempts to provide a theoretical basis underpinning the ways in which gamification works have tended to center on Self-Determination Theory, although others, such as Flow Theory, and Experiential Learning Theory are also well-represented (Krath & On Korflesch, Citation2021); to date, there has been little if any, works which attempt to explore the theoretical basis for gamblification. Given that the core concepts of SDT are autonomy, competence, and social relatedness, it is unlikely that the uncertain, chance-based outcomes of gamblification can be explained in the same way. Similarly, the typically short-term, reward-focused interactions afforded by gamblified systems and products are unlikely to be explained by Flow Theory or Experiential Learning. We thus call for the development of insightful theoretical knowledge across multiple disciplines and, especially, design theories for an efficient and effective gamblification of information systems and human–computer interaction, for example. To adequately address this backdrop, we compiled an initial research agenda in .

Table 3. Research agenda.

Beyond the topics raised in the research agenda, an aspect that particularly attracted our attention during the review of existing literature was that gambling game design elements, as well as chance-based mechanisms, have predominantly been classified as gamification, despite the fine nuances and important consequences which arise from disentangling these two expressions. Yet, we strongly believe that both expanding the term to account for gambling design elements and the act of disentangling gamblification from gamification expands our scholarly knowledge by providing valuable perspectives and insights.

Moreover, we firmly believe that gamblification is especially relevant to fields, such as IS and HCI, however, it appears to be under-represented in the contemporary literature from these disciplines, regardless of its clear relevance. This suggests that other fields (e.g., media studies, gambling studies, neuroscience) have shown more innovation and openness in their approach to this emerging topic. Therefore, we further encourage to initiate a discussion about gamblification across wider fields, especially regarding the role of technology in the gamblification design.

We expect that without thorough research, the gulf between evaluation and execution will hold back ethical and effective gamblification, resulting in practitioners increasingly employing it without proper guidance and without research properly acknowledging and learning from the phenomenon above and beyond insights from gamification. Similar to gamification, gamblification can suffer from uninformed utilization of gamblification design elements, causing gamblification attempts in practice more likely to fail. Therefore: (1) more research on the general understanding of gamblification needs to be conducted to be able to; (2) correctly assess the effects of gamblification design elements on user experiences, engagement, and resource transfer; and (3) to evolve new design methodologies which can act as guidelines for the design of effective gamblified systems, products, and services.

6. Conclusion

The aim of this work was to examine points of similarity and difference between the emerging topic of gamblification and the more well-established topic of gamification. The intention was to highlight the scope of gamblification as a means to promote specific user behavior and to provide a clear theoretical basis for ongoing investigation into this phenomenon which has the potential for notable social and economic impact.

This work shows that while gamification and gamblification are both techniques used to encourage specific behavior on the part of individual users and consumers, the two are both conceptually and practically distinct from one another. These differences extend from the wider paradigms of the ludification of culture and casino capitalism, with which the two are associated, to the diverse ways in which they are implemented.

The most significant point of difference is that while successful gamification primarily utilizes intrinsic motivations to effect meaningful change, gamblification does so predominantly through leveraging extrinsic motivations. Consequently, gamification and gamblification are used to achieve different aims and are suited to different contexts; gamification is suitable for effecting long-term engagement and goal-oriented changes, while gamblification is often focused on short-term monetization or engagement.

The study of gamification has developed considerably over the last decade, with a substantial body of work being dedicated to the topic, while work dedicated to investigating gamblification is less advanced. Therefore, this study additionally presents a potential research agenda to develop a coherent understanding of the ways in which users engage with gamblified systems and services and, therefore, to minimize potentially problematic implementations.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Joseph Macey

Joseph Macey is a Postdoctoral Researcher at the Centre for Excellence in Game Culture, University of Turku. In addition to publishing in international journals and presenting his work at a range of conferences, he is engaged with social outreach organisations and is a founding member of the Esports Research Network.

Martin Adam

Martin Adam is Chaired Professor of Information Systems - Smart Services, University of Goettingen. Research interests include human-computer interaction and the digital transformation of work and people. He has published in various international journals, and is Associate Editor at Information Systems Journal, Business & Information Systems Engineering, and Electronic Markets.

Juho Hamari

Juho Hamari is a Professor of Gamification at Tampere University, where he leads research a large multidisciplinary research program on gamification. Throughout his career, he has published 200 peer-reviewed research articles primarily in the areas of information science, computer science (especially HCI), applied psychology, and business and management studies.

Alexander Benlian

Alexander Benlian is a Chaired Professor of Information Systems and Electronic Services at Technical University of Darmstadt, Germany. His research focuses on algorithmic management, the digital transformation of work and people, IT entrepreneurship, and human-computer interaction. He has published in multiple international journals and serves on several editorial boards.

References

- Abarbanel, B. (2018). Gambling vs. gaming: A commentary on the role of regulatory, industry, and community stakeholders in the loot box debate. Gaming Law Review, 22(4), 231–234. https://doi.org/10.1089/glr2.2018.2243

- Abarbanel, B., & Johnson, M. R. (2020). Gambling engagement mechanisms in Twitch live streaming. International Gambling Studies, 20(3), 393–413. https://doi.org/10.1080/14459795.2020.1766097

- Abt, V., McGurrin, M. C., & Smith, J. F. (1984). Gambling: The misunderstood sport—A problem in social definition. Leisure Sciences, 6(2), 205–220. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490408409513031

- Adam, M., Reinelt, A., & Roethke, K. (2023). Gamified monetary reward designs: Offering certain versus chance‐based rewards. Information Systems Journal, 33(6), 1426–1454. https://doi.org/10.1111/isj.12459

- Aitken, R. (2014). Games and the subjugated knowledges of finance: Art and science in the speculative imaginary. TOPIA: Canadian Journal of Cultural Studies, 30–31, 65–88. https://doi.org/10.3138/topia.30-31.65

- Al-Msallam, S., Xi, N., & Hamari, J. (2023). Ethical considerations in gamified interactive marketing praxis. In C.L. Wang (Ed.), The Palgrave handbook of interactive marketing (pp. 963–985). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-14961-0_41

- Andrade, M., & Newall, P. W. S. (2023). Cryptocurrencies as gamblified financial assets and cryptocasinos: Novel risks for a public health approach to gambling. Risks, 11(3), 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks11030049

- Anselme, P., & Robinson, M. J. F. (2013). What motivates gambling behavior? Insight into dopamine’s role. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 7, 182. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2013.00182

- Bailey, M. J., Olson, M., & Wonnacott, P. (1980). The marginal utility of income does not increase: Borrowing, lending, and Friedman-Savage gambles. The American Economic Review, 70(3), 372–379.

- Barsky, J. (2018). Fishing for whales: A segmentation model for social casinos. International Journal of Quality and Service Sciences, 10(4), 400–421. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJQSS-06-2017-0053

- Behl, A., & Dutta, P. (2020). Engaging donors on crowdfunding platform in disaster relief operations (DRO) using gamification: A civic voluntary model (CVM) approach. International Journal of Information Management, 54, 102140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102140

- Benner, D., Schöbel, S., Janson, A., & Leimeister, J. M. (2022). How to achieve ethical persuasive design: A review and theoretical propositions for information systems. AIS Transactions on Human–Computer Interaction, 14(4), 548–577. https://doi.org/10.17705/1thci.00179

- Binde, P. (2013). Why people gamble: A model with five motivational dimensions. International Gambling Studies, 13(1), 81–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/14459795.2012.712150

- Binde, P. (2009). Gambling motivation and involvement : A review of social science research. Swedish National Institute of Public Health.

- Brock, T., & Johnson, M. (2021). The gamblification of digital games. Journal of Consumer Culture, 21(1), 3–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469540521993904

- Bui, A., Veit, D., Webster, J. (2015). Gamification – A novel phenomenon or a new wrapping for existing concepts? In ICIS 2015 Proceedings. Presented at the Thirty Sixth International Conference on Information Systems, AISeL, Fort Worth, TX, USA.

- Caillois, R., & Barash, M. (2001). Man, play, and games. University of Illinois Press.

- Cassidy, R. (2013). Partial convergence: Social gaming and real-money gambling. In Qualitative research in gambling (pp. 74–91). Routledge.

- Chen, N., Elmachtoub, A. N., Hamilton, M., & Lei, X. (2020). Loot box pricing and design. In Proceedings of the 21st ACM Conference on Economics and Computation. Presented at the EC ’20: The 21st ACM Conference on Economics and Computation, ACM, Virtual Event Hungary (pp. 291–292). https://doi.org/10.1145/3391403.3399503

- Cherkasova, M. V., Clark, L., Barton, J. J. S., Schulzer, M., Shafiee, M., Kingstone, A., Stoessl, A. J., & Winstanley, C. A. (2018). Win-concurrent sensory cues can promote riskier choice. The Journal of Neuroscience, 38(48), 10362–10370. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1171-18.2018

- Chou, Y.-K. (2019). Actionable gamification: Beyond points, badges, and leaderboards. Packt Publishing.

- Clark, L. (2014). Disordered gambling: The evolving concept of behavioral addiction. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1327(1), 46–61. https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.12558

- Clark, L., Boileau, I., & Zack, M. (2019). Neuroimaging of reward mechanisms in gambling disorder: An integrative review. Molecular Psychiatry, 24(5), 674–693. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-018-0230-2

- Clark, L., Lawrence, A. J., Astley-Jones, F., & Gray, N. (2009). Gambling near-misses enhance motivation to gamble and recruit win-related brain circuitry. Neuron, 61(3), 481–490. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2008.12.031

- Clark, L., Liu, R., McKavanagh, R., Garrett, A., Dunn, B. D., & Aitken, M. R. F. (2013). Learning and affect following near-miss outcomes in simulated gambling: Learning and gambling near-misses. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 26(5), 442–450. https://doi.org/10.1002/bdm.1774

- Conlisk, J. (1993). The utility of gambling. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 6(3), 255–275. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01072614

- Cotte, J., & Latour, K. A. (2009). Blackjack in the kitchen: Understanding online versus casino gambling. Journal of Consumer Research, 35(5), 742–758. https://doi.org/10.1086/592945

- Dargan, T., & Evequoz, F. (2015). Designing engaging e-Government services by combining user-centered design and gamification: A use-case. In Proceedings of the 15th European Conference on eGovernment. Presented at the European Conference on eGovernment, Academic Conferences and Publishing International Limited, Portsmouth, UK (pp. 70–78).

- David, F. N. (1998). Games, gods, and gambling: A history of probability and statistical ideas. Courier Corporation.

- Davis, M. S., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1977). Beyond boredom and anxiety: The experience of play in work and games. Contemporary Sociology, 6(2), 197. https://doi.org/10.2307/2065805

- Delfabbro, P., King, D. L., & Carey, P. (2021). Harm severity in internet gaming disorder and problem gambling: A comparative study. Computers in Human Behavior, 124, 106898. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2021.106898

- Devisch, O., Poplin, A., & Sofronie, S. (2016). The gamification of civic participation: Two experiments in improving the skills of citizens to reflect collectively on spatial issues. Journal of Urban Technology, 23(2), 81–102. https://doi.org/10.1080/10630732.2015.1102419

- Diecidue, E., Schmidt, U., & Wakker, P. P. (2004). The utility of gambling reconsidered. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 29(3), 241–259. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:RISK.0000046145.25793.37

- Dimoka, Hong, & Pavlou. (2012). On product uncertainty in online markets: Theory and evidence. MIS Quarterly, 36(2), 395. https://doi.org/10.2307/41703461

- Dubal, V. (2023). On algorithmic wage discrimination.

- Fabbri, M., Nicola Barbieri, P., & Bigoni, M. (2019). Ride your luck! A field experiment on lottery-based incentives for compliance. Management Science, 65(9), 4336–4348. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2018.3163

- Ferentzy, P., Turner, N. E., Ferentzy, P., & Turner, N. E. (2013). The history of gambling and its intersection with technology, religion, medical science, and metaphors. In The history of problem gambling: Temperance, substance abuse, medicine, and metaphors (pp. 5–28). Springer.

- Fogg, B. J. (2002). Persuasive technology: Using computers to change what we think and do. Ubiquity, 2002(December), 2. https://doi.org/10.1145/764008.763957

- Friman, U., Turtiainen, R. (2017). From gamification to funification of exercise: Case zombie run pori 2015. In Presented at the GamiFIN 2017 (pp. 53–59). Ceur-Ws.

- Fuchs, M. (2014). Predigital precursors of gamification. In Rethinking gamification. Meson Press by Hybrid Publishing Lab.

- Golrang, H., & Safari, E. (2021). Applying gamification design to a donation-based crowdfunding platform for improving user engagement. Entertainment Computing, 38, 100425. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.entcom.2021.100425

- Google (2023). Money made simple, by Google [WWW Document]. Retrieved August 11, 2023, from https://pay.google.com/intl/en_in/about/

- Govender, T., & Arnedo-Moreno, J. (2020). A survey on gamification elements in mobile language-learning applications. In Eighth International Conference on Technological Ecosystems for Enhancing Multiculturality. Presented at the TEEM’20: Eighth International Conference on Technological Ecosystems for Enhancing Multiculturality, ACM, Salamanca Spain (pp. 669–676). https://doi.org/10.1145/3434780.3436597

- Grange, C., Benbasat, I., & Burton-Jones, A. (2019). With a little help from my friends: Cultivating serendipity in online shopping environments. Information & Management, 56(2), 225–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2018.06.001

- Griffiths, M. (2018). Is the buying of loot boxes in video games a form of gambling or gaming? Gaming Law Review, 22(1), 52–54. https://doi.org/10.1089/glr2.2018.2216

- Griffiths, M. (1995). Adolescent gambling, adolescence and society. Routledge.

- Guo, H., Hao, L., Mukhopadhyay, T., & Sun, D. (2019). Selling virtual currency in digital games: Implications for gameplay and social welfare. Information Systems Research, 30(2), 430–446. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.2018.0812

- Hamari, J. (2017). Do badges increase user activity? A field experiment on the effects of gamification. Computers in Human Behavior, 71, 469–478. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.03.036

- Hamari, J., Koivisto, J., & Sarsa, H. (2014). Does gamification work?–A literature review of empirical studies on gamification.

- Hassan, L., & Hamari, J. (2020). Gameful civic engagement: A review of the literature on gamification of e-participation. Government Information Quarterly, 37(3), 101461. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2020.101461

- Högberg, J., Hamari, J., & Wästlund, E. (2019). Gameful Experience Questionnaire (GAMEFULQUEST): An instrument for measuring the perceived gamefulness of system use. User Modeling and User-Adapted Interaction, 29(3), 619–660. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11257-019-09223-w

- Hollebeek, L. D., Das, K., & Shukla, Y. (2021). Game on! How gamified loyalty programs boost customer engagement value. International Journal of Information Management, 61, 102308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2021.102308

- Hong, Y., & Pavlou, P. A. (2014). Product fit uncertainty in online markets: Nature, effects, and antecedents. Information Systems Research, 25(2), 328–344. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.2014.0520

- Hou, J., Kim, K., Kim, S. S., & Ma, X. (2019). Disrupting unwanted habits in online gambling through information technology. Journal of Management Information Systems, 36(4), 1213–1247. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421222.2019.1661088

- Hristova, D., Dumit, J., Lieberoth, A., & Slunecko, T. (2021). Snapchat streaks: How adolescents metagame gamification in social media. In Proceedings of the 4th International GamiFIN Conference. Presented at the GamiFIN 2021, CEUR-WS, Levi, Finland (pp. 126–135).

- Hristova, D., & Lieberoth, A. (2021). How socially sustainable is social media gamification? A look into Snapchat, Facebook, Twitter and Instagram. In A. Spanellis & J. T. Harviainen (Eds.), Transforming society and organizations through gamification. (pp. 225–245). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-68207-1_12

- Huotari, K., & Hamari, J. (2017). A definition for gamification: Anchoring gamification in the service marketing literature. Electronic Markets, 27(1), 21–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12525-015-0212-z

- Huotari, K., & Hamari, J. (2012). Defining gamification: A service marketing perspective. In Proceeding of the 16th International Academic MindTrek Conference. Presented at the AcademicMindTrek ’12: International Conference on Media of the Future, ACM, Tampere Finland (pp. 17–22). https://doi.org/10.1145/2393132.2393137

- James, R. J. E., & Tunney, R. J. (2017). The relationship between gaming disorder and addiction requires a behavioral analysis: Commentary on: Scholars’ open debate paper on the World Health Organization ICD-11 Gaming Disorder proposal (Aarseth et al.). Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 6(3), 306–309. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.6.2017.045

- Johnson, M. R. (2019). The unpredictability of gameplay. Bloomsbury Academic.

- Johnson, M. R., & Brock, T. (2020). The ‘gambling turn’ in digital game monetization. Journal of Gaming & Virtual Worlds, 12(2), 145–163. https://doi.org/10.1386/jgvw_00011_1

- Johnson, P. (2009). About the Kukui Cup [WWW Document]. Reuters. Retrieved September 9, 2023, from https://manoa.hawaii.edu/sustainability/2009/09/about-the-kukui-cup/#:∼:text=The%20Kukui%20Cup%20Project%20explores,change%20in%20sustainability%2Drelated%20behaviors

- Juniper Research (2021). Video game loot boxes to generate over $20 billion in revenue by 2025, but tightening legislation will slow growth. Retrieved August 11, 2023, from https://www.juniperresearch.com/press/video-game-loot-boxes-to-generate-over-$20-billion?utm_campaign=pr1_ingamegamblinglootboxes_providers_content_mar21&utm_source=Twitter&utm_medium=social

- Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47(2), 263. https://doi.org/10.2307/1914185

- Kao, D. (2020). Infinite loot box: A platform for simulating video game loot boxes. IEEE Transactions on Games, 12(2), 219–224. https://doi.org/10.1109/TG.2019.2913320

- Khan, A., Boroomand, F., Webster, J., & Minocher, X. (2020). From elements to structures: An agenda for organisational gamification. European Journal of Information Systems, 29(6), 621–640. https://doi.org/10.1080/0960085X.2020.1780963

- Kickstarter (2023). Creator Handbook: Funding [WWW Document]. Kickstarter.com. Retrieved August 11, 2023, from https://www.kickstarter.com/help/handbook/funding?ref=handbook_rewards

- Kim, T. W., & Werbach, K. (2016). More than just a game: Ethical issues in gamification. Ethics and Information Technology, 18(2), 157–173. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10676-016-9401-5

- King, D. L., & Delfabbro, P. H. (2019). Video game monetization (e.g., ‘loot boxes’): A blueprint for practical social responsibility measures. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 17(1), 166–179. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-018-0009-3

- King, D. L., Gainsbury, S. M., Delfabbro, P. H., Hing, N., & Abarbanel, B. (2015). Distinguishing between gaming and gambling activities in addiction research. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 4(4), 215–220. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.4.2015.045

- Koivisto, J., & Hamari, J. (2019). The rise of motivational information systems: A review of gamification research. International Journal of Information Management, 45, 191–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2018.10.013

- Krath, J., On Korflesch, H. (2021). Designing gamification and persuasive systems: A systematic literature review. In CEUR Workshop Proceedings. Presented at the 5th International GamiFIN Conference (pp. 100–109).

- Landers, R. N. (2014). Developing a theory of gamified learning: Linking serious games and gamification of learning. Simulation & Gaming, 45(6), 752–768. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046878114563660

- Langham, E., Thorne, H., Browne, M., Donaldson, P., Rose, J., & Rockloff, M. (2015). Understanding gambling related harm: A proposed definition, conceptual framework, and taxonomy of harms. BMC Public Health, 16(1), 80. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-2747-0

- Le Menestrel, M. (2001). A process approach to the utility for gambling. Theory and Decision, 50(3), 249–262. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010325930290

- Lexel, O. (2019). Weight-loss wagering apps are a game you can’t win. Weight-loss wagering apps are a game you can’t win. Retrieved August 11, 2023, from https://theoutline.com/post/8392/weight-loss-wagering-healthywage-dietbet

- Lichtenberg, S., Brendel, A. B. (2020). Arrr you a pirate? Towards the gamification element “Lootbox”. In AMCIS 2020 Proceedings. Presented at the Americas Conference on Information Systems, AISeL.

- Li, L., Huang, C. R., & Wang, V. X. (2020). Lexical competition and change: A corpus-assisted investigation of gambling and gaming in the past centuries. Sage Open, 10(3). https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244020951272

- Liu, C.-W., Gao, G., & Agarwal, R. (2019). Unraveling the “social” in social norms: The conditioning effect of user connectivity. Information Systems Research, 30(4), 1272–1295. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.2019.0862

- Liu, D., Li, X., & Santhanam, R. (2013). Digital games and beyond: What happens when players compete. MIS Quarterly, 37(1), 111–124. https://doi.org/10.25300/MISQ/2013/37.1.05

- Liu, D., Santhanam, R., & Webster, J. (2017). Toward meaningful engagement: A framework for design and research of gamified information systems. MIS Quarterly, 41(4), 1011–1034. https://doi.org/10.25300/MISQ/2017/41.4.01

- Lopez-Gonzalez, H., Estévez, A., & Griffiths, M. D. (2019). Internet-based structural characteristics of sports betting and problem gambling severity: Is there a relationship? International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 17(6), 1360–1373. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-018-9876-x

- Lopez-Gonzalez, H., & Griffiths, M. D. (2018). Betting, forex trading, and fantasy gaming sponsorships—A responsible marketing inquiry into the ‘gamblification’ of English football. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 16(2), 404–419. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-017-9788-1

- Ma, X., Kim, S. H., & Kim, S. S. (2014). Online gambling behavior: The impacts of cumulative outcomes, recent outcomes, and prior use. Information Systems Research, 25(3), 511–527. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.2014.0517

- Macey, J., & Hamari, J. (2022). Gamblification: A definition. New Media & Society, 26(4), 2046–2065. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448221083903

- Macey, J., & Hamari, J. (2020). GamCog: A measurement instrument for miscognitions related to gamblification, gambling, and video gaming. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 34(1), 242–256. https://doi.org/10.1037/adb0000526

- Macey, J., & Hamari, J. (2019a). eSports, skins and loot boxes: Participants, practices and problematic behaviour associated with emergent forms of gambling. New Media & Society, 21(1), 20–41. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444818786216

- Macey, J., & Hamari, J. (2019b). The games we play: Relationships between game genre, business model and loot box opening. In CEUR Workshop Proceedings.

- Macey, J., Hamari, J., & Adam, M. (2024). A conceptual framework for understanding and identifying gamblified experiences. Computers in Human Behavior, 152, 108087. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2023.108087

- Macey, J., & Kinnunen, J. (2020). The convergence of play: Interrelations of social casino gaming, gambling, and digital gaming in Finland. International Gambling Studies, 20(3), 414–435. https://doi.org/10.1080/14459795.2020.1770834

- Malone, T. W. (1981). Toward a theory of intrinsically motivating instruction. Cognitive Science, 5(4), 333–369. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15516709cog0504_2

- Markets & Markets (2022). Gamification market by component (solution and services), deployment (cloud and on-premises), organization size (SMEs and large enterprises), application, end-user (enterprise-driven and consumer-driven), vertical, and region – Global forecast to 2025. [WWW Document]. Retrieved November 8, 2023, from https://www.marketsandmarkets.com/Market-Reports/gamification-market-991.html

- McCay-Peet, L., & Toms, E. G. (2022). Researching serendipity in digital information environments, synthesis lectures on information concepts, retrieval, and services. Springer Nature.

- McGee, D. (2020). On the normalisation of online sports gambling among young adult men in the UK: A public health perspective. Public Health, 184, 89–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2020.04.018

- McMullan, J. L., & Miller, D. (2008). All in! The commercial advertising of offshore gambling on television. Journal of Gambling Issues, 22, 230–251. https://doi.org/10.4309/jgi.2008.22.6

- McNeill, L. (2023). JetBlue allows your clients to fly like a high roller, whatever their budget. Retrieved August 11, 2023, from https://www.travelgossip.co.uk/suppliers/jetblue-allows-your-clients-to-fly-like-a-high-roller-whatever-their-budget/

- Morgan Stanley (2012). Social gambling: Click here to play. Morgan Stanley Research.

- Nacke, L. E., & Deterding, S. (2017). The maturing of gamification research. Computers in Human Behavior, 71, 450–454. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.11.062

- Newall, P. W. S., & Weiss-Cohen, L. (2022). The gamblification of investing: How a new generation of investors is being born to lose. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(9), 5391. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19095391

- Norsk Pantelotteri AS (2023). Pantelotteriet [WWW Document]. Pantelotteriet. Retrieved November 8, 2023, from https://pantelotteriet.no/#page-1

- Palmquist, A., Munkvold, R., & Goethe, O. (2021). Gamification design predicaments for e-learning. In X. Fang (Ed.), HCI in games: Serious and immersive games, lecture notes in computer science (pp. 245–255). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-77414-1_18

- Pavlou, Liang, & Xue, 2007. Understanding and mitigating uncertainty in online exchange relationships: A principal-agent perspective. MIS Quarterly, 31(1), 105. https://doi.org/10.2307/25148783

- Pellikka, H. (2014). Gamification in social media. University of Oulu.

- Pfeiffer, A., & Sedlecky, G. (2020). An introduction to gambling in the context of game studies. In Mixed reality and games: Theoretical and practical approaches in game studies and education (pp. 281–294). Transcript Verlag.

- Raessens, J. (2006). Playful identities, or the ludification of culture. Games and Culture, 1(1), 52–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412005281779

- Raymen, T., & Smith, O. (2020). Lifestyle gambling, indebtedness and anxiety: A deviant leisure perspective. Journal of Consumer Culture, 20(4), 381–399. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469540517736559

- Reber, A. S. (1995). The Penguin dictionary of psychology (Penguin Reference Books, Ed., 2nd ed.). Penguin Books.

- Reinelt, A., Adam, M., & Röthke, K. (2021). Accounting for gambling design elements: A proposal to advance gamification taxonomies. In ECIS 2021 research papers. AISeL.

- Rice University (2020). 2020 Election prediction contest [WWW Document]. Retrieved August 14, 2023, from https://ricevotes.rice.edu/2020-epc

- Robinson, T. E., & Berridge, K. C. (2001). Incentive-sensitization and addiction. Addiction, 96(1), 103–114. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.9611038.x

- Roethke, K., Adam, M., & Benlian, A. (2020). Loot box purchase decisions in digital business models: The role of certainty and loss experience. In Proceedings of the 53rd Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences. Presented at the Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, AISeL, Hawaii, USA. https://doi.org/10.24251/HICSS.2020.150

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. Guilford Press.

- Saleem, A. N., Noori, N. M., & Ozdamli, F. (2022). Gamification applications in e-learning: A literature review. Technology, Knowledge and Learning, 27(1), 139–159. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10758-020-09487-x

- Salen, K., & Zimmerman, E. (2003). Rules of play: Game design fundamentals. MIT Press.

- Scopely (2023). Stumble guys.

- Seaborn, K., & Fels, D. I. (2015). Gamification in theory and action: A survey. International Journal of Human–Computer Studies, 74, 14–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs.2014.09.006

- Shen, L., Fishbach, A., & Hsee, C. K. (2015). The motivating-uncertainty effect: Uncertainty increases resource investment in the process of reward pursuit. Journal of Consumer Research, 41(5), 1301–1315. https://doi.org/10.1086/679418

- Shen, L., Hsee, C. K., & Talloen, J. H. (2019). The fun and function of uncertainty: Uncertain incentives reinforce repetition decisions. Journal of Consumer Research, 46(1), 69–81. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucy062

- Sironi, P. (2016). FinTech innovation: From robo-advisors to goal based investing and gamification, The Wiley finance series. Wiley.

- Smith, J. F., & Abt, V. (1984). Gambling as play. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 474(1), 122–132. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716284474001011

- Starbucks. (2021). Celebrate 50 Years of Starbucks with the Starland: 50th Anniversary Edition Game [WWW Document].com. Retrieved November 8, 2023, from https://stories.starbucks.com/press/2021/starbucks-starland-50th-anniversary-edition/

- Steam (2021). Community Market [WWW Document]. Steamcommunity.com. Retrieved November 8, 2023, from https://steamcommunity.com/market/search

- Stehmann, J. (2020). Identifying research streams in online gambling and gaming literature: A bibliometric analysis. Computers in Human Behavior, 107, 106219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.106219

- Stenros, J. (2017). The game definition game: A review. Games and Culture, 12(6), 499–520. https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412016655679

- Stone, S. (2023). Playing to win: The effects of implementing gamification strategies in product marketing. Claremont McKenna College.

- Strange, S., & Watson, M. (2016). Casino capitalism (2nd republication ed.). Manchester University Press.

- Sutton-Smith, B. (1997). The ambiguity of play. Harvard University Press.

- Thibault, M., & Hamari, J. (2021). Seven points to reappropriate gamification. In A. Spanellis & J. T. Harviainen (Eds.), Transforming society and organizations through gamification (pp. 11–28). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-68207-1_2

- Tobon, S., Ruiz-Alba, J. L., & García-Madariaga, J. (2020). Gamification and online consumer decisions: Is the game over? Decision Support Systems, 128, 113167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2019.113167

- Toda, A. M., Klock, A. C. T., Oliveira, W., Palomino, P. T., Rodrigues, L., Shi, L., Bittencourt, I., Gasparini, I., Isotani, S., & Cristea, A. I. (2019). Analysing gamification elements in educational environments using an existing gamification taxonomy. Smart Learning Environments, 6(1), 16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40561-019-0106-1

- Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1974). Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases. Science, 185(4157), 1124–1131. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.185.4157.1124

- Vamplew, W. (2007). Playing with the rules: Influences on the development of regulation in sport. The International Journal of the History of Sport, 24(7), 843–871. https://doi.org/10.1080/09523360701311745

- Vasudevan, K., & Chan, N. K. (2022). Gamification and work games: Examining consent and resistance among Uber drivers. New Media & Society, 24(4), 866–886. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448221079028

- Veit, D., Clemons, E., Benlian, A., Buxmann, P., Hess, T., Kundisch, D., Leimeister, J. M., Loos, P., & Spann, M. (2014). Business models: An information systems research agenda. Business & Information Systems Engineering, 6(1), 45–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12599-013-0308-y

- Vieira, T. (2023). Platform couriers’ self‐exploitation: The case study of Glovo. New Technology, Work and Employment, 38(3), 493–512. https://doi.org/10.1111/ntwe.12272

- Warmelink, H., Koivisto, J., Mayer, I., Vesa, M., & Hamari, J. (2020). Gamification of production and logistics operations: Status quo and future directions. Journal of Business Research, 106, 331–340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.09.011

- WayBetter (2023). Lose weight playing games. Seriously! [WWW Document]. Retrieved August 11, 2023, from https://waybetter.com/

- whatacoolwitch (2023). Hextech crafting FAQ [WWW Document]. Riotgames.com. Retrieved November 8, from https://support-leagueoflegends.riotgames.com/hc/en-us/articles/360036422453

- Woodcock, J., & Johnson, M. R. (2018). Gamification: What it is, and how to fight it. The Sociological Review, 66(3), 542–558. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038026117728620

- Xi, N., & Hamari, J. (2019). Does gamification satisfy needs? A study on the relationship between gamification features and intrinsic need satisfaction. International Journal of Information Management, 46, 210–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2018.12.002

- Zack, M., St. George, R., & Clark, L. (2020). Dopaminergic signaling of uncertainty and the aetiology of gambling addiction. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry, 99, 109853. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnpbp.2019.109853

- Zanescu, A., French, M., & Lajeunesse, M. (2020). Betting on DOTA 2’s battle pass: Gamblification and productivity in play. New Media & Society, 23(10), 2882–2901. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444820941381

- Zanescu, A., Lajeunesse, M., & French, M. (2021). Speculating on steam: Consumption in the gamblified platform ecosystem. Journal of Consumer Culture, 21(1), 34–51. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469540521993928