?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This research delves into the dynamics of active school transport (AST) by utilizing a two-stage co-design process and leveraging persuasive technology within a game for promoting AST called Battleship-AST. The primary aim of this research is to thoroughly investigate the two-stage game co-design process employed in creating a Battleship-AST game. Moreover, our research aims to evaluate participants’ perceptions regarding the motivating and engaging potential of the persuasive technology and gamification features embedded within the final iteration of the game. This evaluation aims to understand how these features influence participants’ motivation to increase their usage of AST through gameplay. In pursuit of these objectives, the research builds upon the existing Battleship-AST prototype and actively engages school children in a collaborative two-stage co-design process. Their valuable insights and preferences were harnessed in refining the game, which was subsequently tested during a tech event in Skellefteå, Sweden. The findings shed light on various aspects of the game’s impact, from its reception to the gamification features integrated within. Notably, the research highlights the positive impact of the co-design process, with increased motivation and engagement observed among the participants. Their involvement in shaping the game’s design resulted in a more engaging and enjoyable experience. The persuasive technology features, encompassing competition, collaboration, auditory cues, a virtual reward system, and an emphasis on similarity, played a pivotal role in sustaining engagement and motivating players. Elements such as rewards, leaderboard progression, and badges proved highly effective in encouraging continued participation and fostering a positive feedback loop. However, the study also identifies areas for potential improvement, including the need to measure real-life progress and refine the game’s levelling system. The research indicates that refining feedback mechanisms and tailoring game content to individual preferences could create an even more engaging experience. Additionally, long-term playtesting is proposed to assess the game’s extended impact. The findings offer promising avenues for enhancing motivation and engagement in AST, which can contribute to the promotion of healthier and more sustainable transportation choices among school children.

1. Introduction

Active School Transport (AST), which involves students actively commuting to school on foot, by bicycle, or by other non-motorized methods, presents a promising approach for promoting physical activity, alleviating traffic congestion, and fostering sustainable transportation choices among school children (Kaseva et al., Citation2023; Larouche et al., Citation2020; Pont et al., Citation2009). Despite these benefits, motivating children to opt for AST over more passive modes of transportation, such as private car travel or school bus rides, remains a substantial challenge (Larouche et al., Citation2014). The World Health Organization (WHO) has recommended that children get at least 60 minutes of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity daily (WHO, Citation2010). Unfortunately, children and adolescents are increasingly sedentary and less than 20% achieve the recommended levels (Guthold et al., Citation2020). AST is an effective means to increase physical activity (Larouche et al., Citation2020), however, effective interventions is needed to motivate children to use active transportation modes (Lindqvist & Rutberg, Citation2018; Rutberg & Lindqvist, Citation2018). A study in several countries revealed that the popularity of AST varied significantly between regions (Larouche et al., Citation2020). For instance, Colombia and Finland have the highest rates, while the United States and India have the lowest rates of AST (Larouche et al., Citation2020). Unfortunately, in recent years, there has been a decline in AST rates due to various factors including urbanisation, safety concerns, the convenience of motorized transport, lack of motivation, attitudes, and parental concerns (Mandic et al., Citation2017; Rutberg & Lindqvist, Citation2019). It is expected that the number of children using AST will continue declining if society does not intervene (Mandic et al., Citation2017; Rutberg & Lindqvist, Citation2019).

Addressing the challenge of promoting AST among school-aged children, researchers have explored innovative methods such as persuasive technology and gamification (Coombes & Jones, Citation2016; Farella et al., Citation2020; Julien et al., Citation2021; Laine et al., Citation2020; Marconi et al., Citation2018; Sipone et al., Citation2021; Citation2023). Persuasive technology refers to the use of technology and design principles to influence and motivate individuals towards desired behaviours and attitudes (Fogg, Citation2002). These persuasive features often utilize cognitive and emotional mechanisms, tapping into the power of feedback, social influence, and competition to promote positive change (Murillo-Muñoz et al., Citation2021). Literature has presented various tools to aid in comprehending, designing, and evaluating persuasive technologies (Murillo-Muñoz et al., Citation2021). Examples of such tools include the functional triad (Fogg, Citation2002), the 8-step process (Fogg, Citation2009), and the persuasive systems design (PSD) model (Oinas-Kukkonen & Harjumaa, Citation2009). Gamification, as a branch of persuasive technology, is essentially the application of game design elements to non-game scenarios (Deterding et al., Citation2011). It involves seamlessly integrating the best aspects of games into more serious environments, such as advancing through levels, competing on leaderboards, and displaying digital badges (Deterding et al., Citation2011). In the context of active school transportation, gamification strategies are designed to make walking or biking to school more fun and appealing to students (Sipone et al., Citation2021; Citation2023). These strategies often utilize mobile applications, online platforms, or physical activity trackers to track students’ progress, provide feedback, and offer incentives for active travel (Marconi et al., Citation2018; Sipone et al., Citation2021; Citation2023). These approaches aim to make walking or biking to school more appealing to students through engaging platforms and incentives. Studies have demonstrated gamification’s potential to enhance physical activity levels and promote AST among children (Coombes & Jones, Citation2016; Corepal et al., Citation2018; Farella et al., Citation2020; Harris & Crone, Citation2021).

Recent qualitative research by Corepal et al. (Citation2018), has started to unveil some of the motivations driving participation in physical activity initiatives, including the desire to compete, earn rewards, socialize, and explore local areas. For instance, Kids-Go-Green, a gamified educational initiative, transformed the daily journey to school into a collaborative educational experience, encouraging sustainable mobility habits (Marconi et al., Citation2018). Results from studies like Marconi et al. (Citation2018) and Savolainen et al. (Citation2020) indicate sustained behavioural changes post-intervention, with students maintaining sustainable transportation practices and transferring them to leisure and family travel contexts. Similarly, Sipone et al. (Citation2021, Citation2023), highlighted the positive impact of gamification on student engagement and learning outcomes, emphasizing the importance of fun and motivation in educational settings. Further supporting the efficacy of gamification, Kazhamiakin et al. (Citation2021) discussed key characteristics of a gamification Platform designed to foster long-term engagement among players, making it a compelling tool for promoting active school transport. Additionally, Coombes and Jones (Citation2016) evaluated the impact of Beat the Street, a program utilizing tracking technology and rewards to promote active travel among children. The intervention school showed a significant increase in weekly active travel per child compared to the control school, underscoring the potential effectiveness of gamification and persuasive technology in promoting active travel behaviours among children.

While gamification shows promise in promoting active school transportation, challenges and gaps remain in the literature (Rutberg & Lindqvist, Citation2018). Harris and Crone (Citation2021) emphasizes the need for additional research to investigate the specific gamification components, such as leaderboards, points, and badges, that are most influential in stimulating behaviour change. This suggests that while gamification holds promise as a strategy for promoting active school transportation, further exploration into its key components is warranted to optimize its effectiveness. Additionally, ongoing investigation is necessary to fully understand the impact of improved engagement with gamification interventions on outcomes related to active transportation behaviours (Coombes & Jones, Citation2016).

Simultaneously, there has been a surge in interest regarding co-design practices, emphasizing a more inclusive, participatory approach (Agbo et al., Citation2021; Paracha et al., Citation2019). Co-design’s central idea is to actively engage the people who will use or be affected by the product or system in shaping its development (Paracha et al., Citation2019; Sanders & Stappers, Citation2008). Co-designing emphasizes a collaborative and inclusive approach where designers work closely with the target audience, seeking their insights and preferences to create a solution that is user-centred and better aligned with their needs and fosters engagement, ultimately leading to increased user satisfaction and loyalty (Havukainen et al., Citation2020; Steen et al., Citation2011). In the context of persuasive game development, co-design can ensure that the game is not only relevant to the intended users but also more engaging and motivating (Ramos-Vega et al., Citation2021). By involving the target audience, school children in the case of AST Battleship persuasive game, in the design process, the resulting game is more likely to capture their interest, align with their motivations, and be more enjoyable to use (Druin, Citation2002). Furthermore, co-design helps tailor the game to specific preferences and needs, making it more persuasive in encouraging the desired behaviour, in this case, AST. While several studies have explored gamification and persuasive game strategies, a notable gap in the literature can be identified such as limited focus on user-centred designs and effectiveness of persuasive elements. The literature needs more research that employs co-design to ensure that the intervention aligns more with their preferences, needs, and motivational factors. While many studies have explored gamified interventions for AST, few studies, like Laine et al. (Citation2022), have effectively implemented co-design principles involving the target audience.

A previous investigation by Oyelere et al. (Citation2022) focused on augmenting physical activity (PA), where they developed a low-fidelity prototype of the game, Battleship-PA. The game incorporated teacher-designed assignments aligned with the curriculum as gamification elements to heighten student motivation for physical activity and increase teacher engagement. During the developmental phase of Battleship-PA, the emphasis was on creating a game that empowered teachers to formulate assignments seamlessly integrating educational activities into the gameplay, thus concurrently fostering physical activity. The study transformed the conventional 2-player Battleship game into a multiplayer game, Battleship-PA, enriched with cooperative, teamwork, and collaboration elements.

Building upon Battleship-PA, the present study introduces the evolution of Battleship-PA into Battleship-AST. We have refined and expanded the game activities to include AST components and enhanced gamification and persuasive technology features. This research focused on the design, development, and evaluation of a game for promoting AST called Battleship-AST, intended to enhance the motivation and engagement of school children in AST. The study encompasses a two-stage co-design process involving school children in refining the game’s design.

The primary aim of this research is to thoroughly investigate the two-stage game co-design process employed in creating a Battleship-AST game using the persuasive design model. Moreover, our research aims to evaluate participants’ perceptions regarding the motivating and engaging potential of the persuasive technology and gamification features embedded within the final iteration of the game. This evaluation aims to understand how these features influence participants’ motivation to increase their usage of AST through gameplay. The persuasive technology features include auditory cues, a virtual reward system, and an emphasis on similarity with the classic Battleship game. These features aim to sustain player engagement, reinforce motivation, and encourage active participation in the game.

This article delves into the details of the research process and its outcomes. We explore the impact of the co-design process on children’s motivation and engagement, with a specific focus on how their active involvement in the game’s development influences their perception and experience. Furthermore, we assess the participants perceptions of the persuasive technology features by examining how elements like rewards, leaderboard progression, and badges motivate players to continue participating in the game. The results of this research provide insights into the design and development of persuasive technology features within the game for promoting AST, offering a promising avenue for promoting AST among school children. By gaining a deeper understanding of how persuasive technology can be effectively utilized in the context of AST, this research aims to contribute to efforts to enhance the motivation and engagement of school children in adopting healthier and more sustainable transportation choices.

The research questions addressed in this study are follows:

How does the two-stage game co-design process contribute to the development of a Battleship-AST game using the persuasive design model?

What are participants’ perceptions regarding the motivating and engaging potential of persuasive technology and gamification features incorporated into the final iteration of the Battleship-AST game?

The contributions of this article are significant across four key areas: Firstly, it advances the understanding of the co-design process: The study thoroughly investigates the two-stage game co-design process employed in developing a Battleship-AST game using the persuasive design model. This examination illuminates how active involvement in game development influences the motivation and engagement of children. Secondly, it provides an evaluation of persuasive technology features: The research assesses participants’ perceptions of persuasive technology features integrated into the game, such as auditory cues and a virtual reward system. This evaluation offers insights into how these features sustain player engagement, reinforce motivation, and promote active participation. Thirdly, it contributes to understanding motivation for AST: Through analyzing participants’ perceptions, the article seeks to comprehend how persuasive technology elements, including rewards, leaderboard progression, and badges, drive players to increase their usage of active school transportation (AST) through gameplay. Finally, it offers practical implications for promoting AST: By deepening the understanding of how persuasive technology can effectively promote AST, the article provides practical insights for designing and implementing persuasive technology features within games to encourage AST among school children.

2. Methods

2.1. Research design

In this study, we adopted a quantitative approach in the data collection, analysis, and presentation of the results. At the heart of the research is a two-stage co-design process that involved iterative development and improvement of the battleship game, building upon the initial version.

To evaluate the persuasive impact of the game in promoting AST, we conducted a formative evaluation. This involved administering a questionnaire to collect feedback and assess participants’ perceptions of the game’s persuasive features aimed at encouraging AST participation.

In this study, we focused on the municipality of Skellefteå in northern Sweden, which is home to a population of 73,984. Skellefteå boasts a well-established network of bicycle and pedestrian roads, and the local authorities excel in maintaining these roads even during winter conditions. As a result, both motorized and nonmotorized transportation options are viable throughout the year.

2.2. Participants

This study included children from the northern Swedish city of Skellefteå, aged 8–14. We enlisted participants for three distinct workshops in the following manner. In the co-design ideation workshops, 70 eighth-grade students from a Skellefteå school, aged 13–14, were involved. The school facilitated the recruitment of these students. Among these participants, 45 were boys (64.3%), and 25 were girls (35.7%). The subsequent playtest occurred at an event named” Cool Teknik,” where 58 participants aged 8–11 participated. The gender distribution was 58.6% male (32/58), 37.9% female (22/58), and 3.4% (2/58) selected” other”. The event organisers handled the recruitment of students for this phase. Evaluation occurred at a subsequent” Cool Teknik” event, with 22 adolescents aged 8–13 considered sufficient for conducting a large-scale user test (Nielsen & Landauer, Citation1993). The gender distribution in this event was 59.1% male (13/22) and 40.9% female (9/22). In this event, the event organisers handled the recruitment of students.

2.3. Data collection instruments

The quantitative data of this study was collected using questionnaires in Appendix A. All questionnaires were initially prepared in English but administered in Swedish to the respondents. Later, they were translated back to English for statistical analysis. The translation of the questionnaire and were carried out by a native Swedish speaker who was also proficient in English, following the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR) guidelines. The data collected in the ideation workshop has been reported in Jingili et al. (Citation2023).

In the playtesting workshop, a 5-point Likert scale questionnaire with open fields after each sections was used (see Appendix A. The sections of this questionnaire were the following: user experience, motivation, audiovisuals and AST perception. The user experience section consisted of questions about what the participants thought about playing the game and their interaction with their team, derived from Laine et al. (Citation2020); Fokides et al. (Citation2019); Petri et al. (Citation2017). The motivation section assessed what motivated the participants to play the game, derived from Laine et al. (Citation2020). The audiovisual section gauged what the participants thought about the looks and sounds of the game, derived from Fokides et al. (Citation2019). The AST impact section measured their attitude towards active school transportation and if they learned more about AST by playing the game, derived from Laine et al. (Citation2020).

During the evaluation workshop, we employed the heuristic evaluation method proposed by Ragnemalm et al. (Citation2011) to assess the persuasiveness of the system, as well as gather insights on motivation, user experience, and learning outcomes. The questionnaire used in this evaluation was designed to elicit feedback from participants adopted from Petri et al. (Citation2017), and consisted of seven sections, each containing 5-point Likert scale questions (see Appendix A. The questionnaire sections covered various aspects related to the game and the persuasive features designed to promote AST. Participants were asked about their motivation for playing the game, their overall view of the game, and how the persuasive features influenced their motivation towards AST. Additionally, the questionnaire explored the perceived usefulness (Davis, Citation1989) of the game in motivating participants towards AST, their opinions on AST, and their intentions regarding AST practices. An open field was included at the end of the questionnaire to encourage participants to provide additional insights. This allowed them to freely express their thoughts, comments, or suggestions regarding the system.

2.4. Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were employed to analyze demographic characteristics. For categorical variables, mean and standard deviation were used to present the descriptive data of continuous variables. The statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS Statistical Package, version 28.

2.5. Ethical considerations

In this study, we followed the principles outlined in the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association, specifically the Declaration of Helsinki. Although this study does not involve medical aspects or the collection of personal health data, we ensured that ethical considerations were upheld throughout the research process. During the event, all data were collected with the informed consent of the children’s guardians, who were fully informed about the nature of the study. To protect the participants’ privacy, we recorded only demographic information such as age and gender for research purposes, and no personal information was collected. Furthermore, this study received ethical approval from the regional ethical committee in Umeå (Dr 2018-10-31 M), further affirming our commitment to upholding ethical standards in this research.

3. Persuasive game Co-design and implementation

3.1. Co-designing persuasive game using the persuasive design model

This study aimed to co-design and develop a persuasive game for promoting AST. We chose to use co-design, aligning with established methodologies for involving end-users in design processes (Sanders & Stappers, Citation2008; A, 2002). We adopted a persuasive game design (PGD) model proposed by Siriaraya et al. (Citation2018), Visch et al. (Citation2013) to guide our design process. The model is particularly suitable for the gamification of AST as it emphasizes persuasive strategies that can induce behavioural change. Encouraging active transportation requires influencing individuals to alter their habits, and a persuasive game design model is well-suited for integrating motivational and behaviour-shaping elements into the gaming experience (Poot et al., Citation2023). A persuasive game design aims to create a user experience that effectively changes players’ behaviour in the real world. The game serves as a platform for users to experience the world from a different perspective while also impacting their actions and attitudes towards a target behavior (Visch et al., Citation2013), such as AST. Siriaraya et al. (Citation2018) introduced a design approach called a” meal” for developing persuasive games. This meal concept represents the different steps involved in the game’s development. A well-designed meal is crucial for the successful implementation of the game design. The typical PGD meal consists of four dishes, symbolizing the various stages in the game’s development process Siriaraya et al. (Citation2018). The first dish focuses on defining the transfer effect of the game, determining how the game will influence players’ behaviour outside of the game environment. The second dish explores the user’s world, understanding their context and preferences. The third dish represents the persuasive game design itself, incorporating persuasive strategies and elements to motivate AST behaviour. Finally, the last dish evaluates the game’s impact on players’ behaviour and attitudes. This flexible approach allowed us to tailor the dishes to our needs and requirements. In the following, we describe each of these meals as applied in our study.

3.1.1. Defining the transfer effect

Previous research conducted in our studies has explored various factors that hinder schoolchildren’s effective adoption of AST in Northern Sweden (Jingili et al., Citation2023). These factors include environmental conditions (such as wet and winter weather), parental safety concerns, and children’s attitudes towards AST. The intervention in this study aims to enhance children’s motivation to utilize AST by implementing a persuasive battleship game. We anticipate that by engaging in the game and reflecting on their experiences, students will not only gain knowledge about AST but also develop a heightened motivation to use AST in their daily routines. The game serves as a means to encourage students to embrace new AST behaviours and sustain them even after they stop playing the game. The intention is for the schoolchildren to continue and further improve upon the AST behaviors they have adopted.

3.1.2. Investigating the user’s world

Inspired by a prior study, that investigated the promotion of AST in workplace settings using gamification (Laine et al., Citation2020). The study delved into the user-centred development process of Tic-Tac-Training, a game that transformed the conventional Tic–Tac–Toe board game into a distributed AST game. In the initial stage of co-design, the researchers implemented the principles of Tic-Tac-Training to revamp, develop, and evaluate the classic multiplayer cooperative game, Battleship-PA, as a physical activity (PA) game aimed at providing children with a fun and engaging experience (Oyelere et al., Citation2022). The game was tested by 13 young boys aged 8–11 in a real-world informal setting (Oyelere et al., Citation2022). To gather comprehensive insights into user experiences and the impact of the Battleship-PA game on behavior change related to physical activity, a mixed-method research approach was employed (Oyelere et al., Citation2022). Data collection in that study (Oyelere et al., Citation2022) involved audio recordings of interactions, direct observation, and a user experience questionnaire. The findings of from the study (Oyelere et al., Citation2022) provided valuable feedback, which was used to enhance both the game and user experiences. The unfiltered recordings revealed that both teams displayed competitiveness, cooperation within their respective teams, and excitement when sinking opponent’s ships or approaching victory. However, repetitive gamification tasks within the game led to feelings of boredom and exhaustion among the children during extended game sessions. Direct observations indicated that the children thoroughly enjoyed the physical activities that resulted from playing the game. However, participants who were unfamiliar with the classical version of Battleship expressed confusion about the game’s objectives and concept. Analysis of the user experience questionnaire indicated that most children found the game easy to play, motivating, engaging, interactive, fun, cooperative, competitive, and visually appealing. Additionally, the majority agreed that the game encouraged them to be physically active, and they strongly expressed enjoyment in performing the physical activities integrated into the game. These positive findings served as motivation to create a persuasive game that leverages these aspects for promoting physical activity among children.

3.1.3. Persuasive game design

The development of the persuasive game involved co-designing with school children, ensuring their active participation in the design process. This approach aimed to gather diverse perspectives and incorporate their ideas into the game’s development. The co-design process consisted of two main phases: the ideation workshop and the playtesting workshop, where students could contribute and collaborate with the developers.

3.1.3.1. Ideation workshop

During the first workshop, the focus was on co-designing with the students. After an introduction, the participants were divided into smaller groups and assigned to separate classrooms. To establish a baseline understanding of the students’ current attitudes and relationship towards AST, each group completed a pre-questionnaire. The students were then shown two videos highlighting the importance of AST. To familiarize the students with the rules of the classical battleship game, they played a paper version against each other. Each participant had their own paper board and their opponent’s board. Appendix A contains the rules used for this activity. Next, the students engaged in a brainstorming session using the” crazy eights” exercise. They visually represented eight different tasks on paper and discussed their ideas within their smaller groups, ultimately selecting their favourite tasks from those generated. The participants were asked to create a solution sketch to further develop their chosen ideas. However, due to technical difficulties during the introduction, only one group had sufficient time to perform a solution sketch for a specific feature they wanted to see in the game. Following the exercises, all groups completed a post-questionnaire sharing their thoughts on AST and the workshop experience, which has been reported in Jingili et al. (Citation2023).

3.1.3.2. Playtesting workshop

The second workshop focused on playtesting the game. The participants created their own users and matches and then each group was divided into two teams that played against each other. The tasks in the game were selected from the tasks proposed by the participants in the ideation workshop. Some examples are:” Find new ways [to travel] to school and log your time”,” Race with a friend to school” and” Go to school with someone new”. These tasks were performed indoors in the school and were completed by moving in the school corridors and the assigned classrooms. When the matches were finished, the participants answered a questionnaire (see Appendix A) on their experience with the game. The full schedule of both workshops can be found in Appendix A.

3.1.4. Evaluation

Considering the time and resource constraints, we deemed conducting a controlled experimental study impractical. However, recognizing the game’s potential to motivate children to use AST and create an enjoyable experience, it was decided to investigate the game’s impact. The primary focus of the investigation centred on the participants’ experience, including enjoyment, challenge, and ease of use, as well as potential changes in user behaviour related to their willingness to engage and continue using AST. To gather relevant insights, a small survey was conducted (see Appendix A).

The evaluation of the game took place during an annual event in Skellefteå called” Cool teknik” or” Cool tech” that showcases emerging technology to local adolescents. The event consisted of two separate play sessions, each with a different set of participants who were instructed to bring either a scooter or a skateboard. The participants were evenly divided into two opposing teams. Before the game commenced, a brief introduction was provided, followed by a video presentation showcasing the game’s features and instructions on how to play. All participants were assigned anonymous user profiles and were given two started games that had been created in advance.

To ensure that all participants were familiar with the game mechanics, they initially played without completing any tasks. Their objective was simply to click and uncover the locations of the opposing team’s ships. In the second game, participants were required to perform the designated tasks before selecting a tile. They were informed that they could use their scooter or skateboard for tasks related to biking or tasks that did not specify a particular mode of transportation. Once a game was completed, participants were given time to check the leaderboard and compare their performance with others. Throughout the games, the states of each game were recorded for analysis. Following their gameplay experience, the participants were provided with a questionnaire to gather their feedback and thoughts on the game. This questionnaire aimed to capture their impressions and insights regarding the overall game experience.

3.2. The game development process

The game’s development embraced the Scrum agile approach with regular weekly meetings. These meetings provided opportunities to review the game’s development progress, identify improvement areas, and plan for further enhancements. The development team comprised a developer and two dedicated researchers who played integral roles by offering guidance and constructive feedback to the developer, aligning the project with best practices and requirements. The agile development method ensured a collaborative and iterative process, allowing continuous feedback and refinement throughout the game’s creation.

3.3. Game concept

3.3.1. Basic gameplay

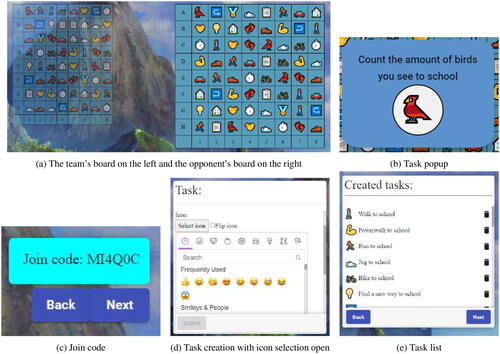

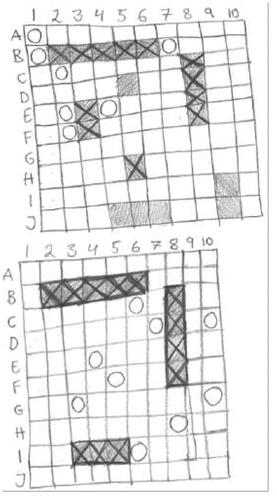

To promote AST, we developed a persuasive game called Battleships-AST, which is based on the classic board game Battleships. Unlike the traditional version of Battleships, where players take turns to collect tiles, Battleships-AST is a competitive and collaborative game played in teams without turns. In Battleships-AST, the teams aim to claim as many tiles as possible from their opponent’s board while performing AST tasks. Each player is presented with their team’s board, which is smaller and somewhat transparent compared to the opponent’s board (refer to ). Both boards are 8 × 8 grids, and selected icons represent tasks. The game involves several hidden ships placed automatically on both teams’ boards. The objective is to sink all the opposing team’s ships before they can sink your team’s ships. The ships can be positioned vertically, horizontally, or diagonally on the board and may be adjacent to other ships. The number of ships is the same as in the traditional paper version of the game (Appendix A). Players can open a popup task description () by selecting a tile and after completing the task of that tile they may claim it for their team. Whenever a tile has been claimed, it will reveal if there is a ship in that tile or not. If there is a ship in that tile, the tile will turn green and if not the tile will turn red. The game ends when a team has sunk all of the opposing team’s ships. To enhance the gaming experience, auditory cues are incorporated into our system. Specifically, our system employs positive reinforcement through celebratory sounds when a player successfully selects a tile containing a ship. Conversely, choosing a tile without a ship triggers a disheartening sound, providing immediate feedback and introducing a nuanced layer to the gaming dynamics.

3.3.2. Match and task creation

In the game system, players can create and modify matches. Each match consists of two teams, and the teams can accommodate multiple players. When the host creates a match, a join code is automatically produced (see ), which players can use to join and participate in the match. The host of the match also has the option to create customized tasks, each accompanied by an emoji icon. The host can select the desired emoji from a searchable list of emojis (see ). Once created, these tasks are added to a list of created tasks (see ). Additionally, the game includes a set of pre-made tasks that are automatically included in the list upon game creation. The host has the flexibility to delete specific tasks from the list before initiating the game.

3.4. Persuasive technology and gamification improvements

Based on feedback received from the playtest workshop, as well as insights from the persuasive system design by Oinas-Kukkonen and Harjumaa (Citation2009) and the Octalysis gamification framework by Chou (Citation2015), several new features were implemented in order to enhance user experience and encourage long-term engagement.

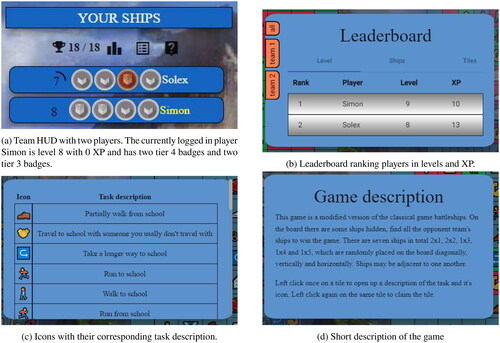

The implemented features are a leaderboard, badges and a leveling system and auditory cues. In addition, the game UI was improved for more visual clarity. These implemented features include a leaderboard, badges, and a levelling system. Additionally, improvements were made to the game’s user interface to enhance visual clarity. The leveling system consists of 10 levels, and players can progress through these levels by earning experience points (XP) by taking tiles in the game (see ). When a player takes a tile, they receive 2 XP, while the rest of the team each receives 1 XP. The amount of XP required to reach the next level increases by 2 XP for each subsequent level, making it progressively more challenging to reach higher levels. The player’s current level is displayed in the player HUD (refer to ). Badges can be earned by reaching specific milestones during gameplay. There are five tiers of badges, with higher tiers becoming increasingly challenging to achieve. Each tier is represented by its own unique icon, which can also be seen in the player HUD (refer to ). The current set of milestones for earning badges includes:

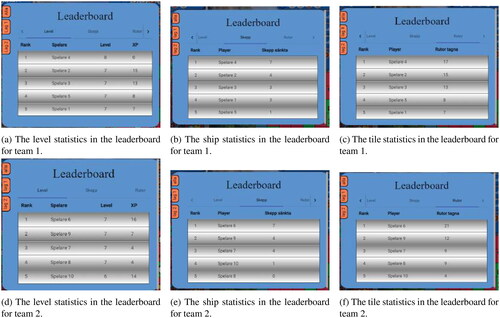

The leaderboard ranks players in either one of the teams or both of the teams in one of the following categories, level and XP, ships taken or tiles taken (). Task icons have been made unique to easier differentiate tasks by simply looking at the board. In addition, a popup which displays all icons and their corresponding task has been added ().

3.5. Architecture and implementation

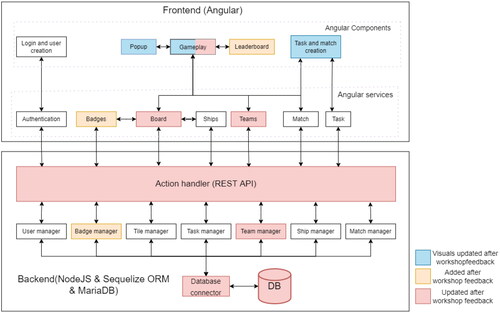

Battleship-AST follows a client–server architecture model where users can access the server with a web browser. illustrates the game architecture implemented with Angular, NodeJS, Sequelize ORM, and MariaDB technologies. Oyelere et al. (Citation2022) goes more in depth on the technical details of the parts from the original prototype. The colored parts illustrate the contributions of the persuasive co-design process to the original prototype.

There are three categories of changes from the prototype (Oyelere et al., Citation2022): new parts, functionally updated parts, and parts that received visual updates. Firstly, the new components were a leaderboard component, a badge service and a badge manager. The leaderboard component is a part of the user interface which can be accessed through and uses data from the gameplay component. The badge service handles badge operations e.g., verifying if each player has earned a higher tier badge and sending the update request to the backend, similarly the badge manager e.g., takes the requests from the badge service and send them to the database and then sends back the database results to the badge service. Secondly, the gameplay component, the board service, the teams service and the team manager were functionally updated. The gameplay component and the board service added support with for example opening buttons and data communication for all of the gamification improvements as described in section 3.4. Thirdly, the gameplay component, popup component and the task and match creation component have been visually updated to clarify which board the player is supposed to guess on, differentiate tasks replaced the previous icons with emojis that can be chosen through an emoji selector ().

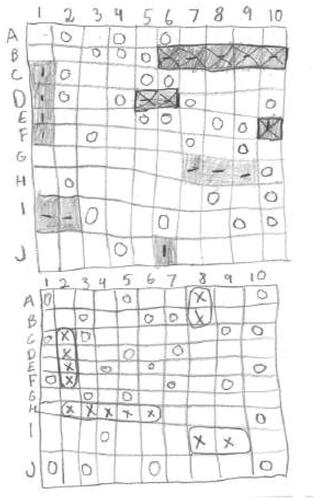

The leaderboard status for all the categories from either team 1 or team 2 in the second game of the first play session can be found in , and the game view of that game can be found in .

4. Results

4.1. Stage one co-design: ideation workshop results

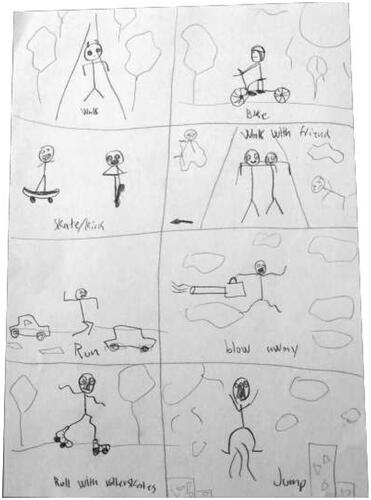

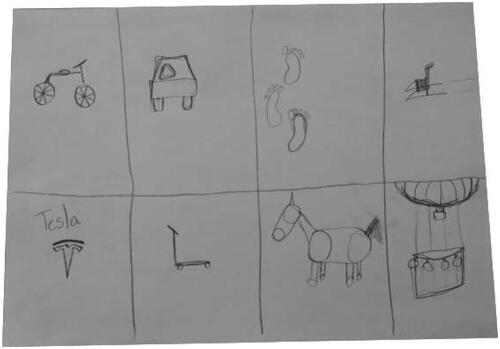

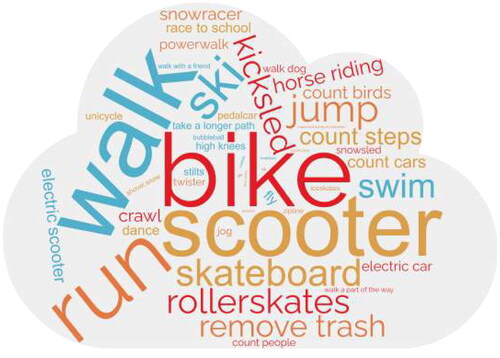

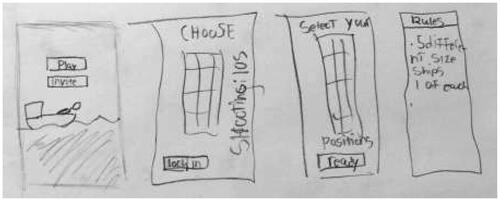

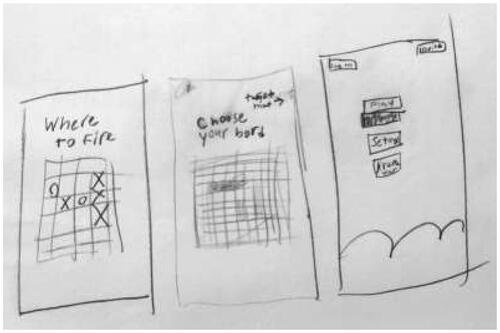

In the initial stage of persuasive game co-design, we conducted ideation exercises with school children to gather their insights and ideas for a persuasive game centered around AST. To engage the children and understand their preferences, we introduced a modified version of the classic Battleship game. Instead of solely focusing on gameplay, we encouraged the children to provide their thoughts and suggestions for the persuasive game. During the ideation workshop, the children were presented with a paper version of the Battleship game specially designed for their participation. and showcase the perspectives of two students playing the game individually, each with their own board and an opponent’s board. The images depict the engagement and concentration of the students as they strategize and make their moves on the paper game boards. One board represents their personal game board, while the other represents their opponent’s board. They engaged in gameplay activities and shared their perspectives on what they would like to see in a game promoting AST. To further stimulate their creativity, we employed the” Crazy Eights” exercise, where the children brainstormed and visualized eight different game ideas on individual papers. and showcase two of the completed drawings, showcasing the participants’ creative ideas for AST. To further analyze and organize the generated ideas, all of the tasks from the exercise were carefully categorized and compiled into a comprehensive document. This document provided an overview of the various task categories proposed by the participants. A word cloud was generated to visualize the frequency of each category as depicted in . The size of each word in the word cloud represents the frequency of that particular category, providing a visual representation of the collective preferences and suggestions of the participants during the ideation phase. We further allowed the participants to express their ideas and concepts for the persuasive game through solution sketches. and showcase two solution sketches created by the participants, offering a glimpse into the creative and innovative features envisioned during the workshop. These sketches reflect the participants’ active involvement and contribution to shaping the game’s design.

4.2. Stage two co-design-Playtest workshop results

The second stage of the co-design process focused on playtesting the developed game with the school children. This stage allowed the children to engage with the game and offer feedback for further improvements. Through their participation, the goal was to assess the game’s potential in motivating children to engage in AST actively. During the playtesting workshop, the children could play the game and experience its mechanics firsthand. As they immersed themselves in the gameplay, we encouraged them to provide suggestions and insights on enhancing the gamification elements to further motivate their involvement in AST. Their feedback and recommendations were crucial in refining the game’s design and making it more appealing and engaging. This stage of the co-design process allowed us to evaluate the game’s impact on the children’s motivation and explore potential gamification improvements. By incorporating their perspectives, we strove to create an interactive and persuasive game that promotes AST and captures the interest and enthusiasm of the target audience—the school children.

The outcomes of the playtest questionnaire are presented in . This table provides a comprehensive overview of participant responses encompassing user experience, motivation, audiovisuals, AST perception, and physical activity. The following sections summarise the results.

4.2.1. User experience

For the general experience, participants had a neutral opinion regarding their understanding of the game (1)(). The responses were again neutral on their overall satisfaction with the game (3)(

). However, responded negatively or expressed uncertainty about their understanding of their team’s progress in the game (2)(

) and if they wanted to play the game again (4)(

). Regarding the feedback of the game, participants responded negatively or express uncertainty about receiving immediate feedback on their actions in the game (5)(

). On the other hand, participants felt more positively towards completing tasks in the game (6)(

). The participants did not feel particularly immersed in the game and responded neutral or no opinion on being deeply concentrated in the game (7)(

). In addition, most participants felt that they did not forget about time while playing (8)(

). On the social aspects of the game were seen as neutral aspects. Most participants felt neutral or did not have any opinion on that the game promotes cooperation and competition in the game (9)(

) and that they were able to interact with other participants during the game (10)(

). However the participants felt more strongly that they had fun with the other participants while playing the game (11)(

).

4.2.2. Motivation

Although the majority of the responses were quite neutral, the participants found the opportunity to move around (17)() and the competitive aspect of the game (12)(

) most motivating. On the other hand, tactic discussions (15)(

) and the tasks of the game (14)(

) were found to be the least motivating aspects of the game. In addition, the participants responded more positively to that they played because the game because it was a part of the workshop (18)(

). Lastly, the participants found the co-operational aspects (13)(

) and the notifications of the game (16)(

) to be positively motivating factors.

4.2.3. Audiovisuals

A majority of the participants agreed that the sound effects of the game were enjoyable (19)() and that they enhanced their experience with the game (20)(

). For the visual aspects of the game, participants responded more positively to that the game was visually appealing (21)(

) and that the game’s appearance fit the mood of the game (22)(

).

4.2.4. AST perception and physical activity

Most participants responded more negatively to that the game increased their knowledge about AST (23)(). For the attitude towards physical activity, most participants thought more positively to both that the game could help them be physically active (24)(

) and to that they were happy to perform physical activities in the game (25)(

).

4.3. Final evaluation of the persuasive game

The outcomes of the evaluation questionnaire of the persuasive game are presented in . This table provides a comprehensive overview of participant responses encompassing aspects such as motivation, perceptions of the user interface, the gaming experience, the influence of persuasive technology and gamification features, motivation concerning AST, opinions on AST, and intentions towards AST. Below is the summary of the results.

4.3.1. Motivation

Most participants had neutral opinions towards having their attention captured by something interesting at the start of the game (27)(μ = 3.23, σ = 0.66), the task variation in the game (28)(μ = 3.09, σ = 1.13), that the game content felt relevant to their interests (29)(μ = 3.00, σ = 0.90) and that the game suits their way of exercising (30)(μ = 3.09, σ = 1.23). The participants were more positively inclined towards the game design (26)(μ = 3.59, σ = 0.73), that the game content felt familiar (31)(μ = 3.45, σ = 0.45) and were confident that they were exercising (32)(μ = 3.86, σ = 1.27). However, the participants felt somewhat forced to play the game as it was a part of the event (33)(μ = 3.77, σ = 1.14).

4.3.2. Interface

A majority of the participants felt that the game was easy to learn (37)(μ = 4.05, σ = 1.19) and that the game was visually appealing (35)(μ = 3.73, σ = 0.63). The controls also was thought to respond somewhat well (36)(μ = 3.27, σ = 1.16). However, the sound effects did not seem to improve the user experience (28)(μ =, σ =), which might be because the systems that the participants played on had quite low sound.

4.3.3. Game experience

Most participants found the competition against the other team enjoyable (39)(μ = 4.00, σ = 1.14) and had fun playing the game (41)(μ = 3.50, σ = 1.12). The participants also found the game difficulty somewhat appropriate (40)(μ = 3.09, σ = 1.23), some would also recommend this game to their classmates (43)(μ = 3.09, σ = 1.51) and some would like to play the game again (44)(μ = 3.18, σ = 1.20). However, most participants did not feel that they forgot about time while playing (38)(μ = 2.72, σ = 1.54) and were not disappointed when the game ended (42)(μ = 2.50, σ = 0.73).

4.3.4. Persuasive technology and gamification features

The participants agreed to that they enjoyed climbing the leaderboard (47)(μ = 4.32, σ = 0.51), leveling up (49)(μ = 4.00, σ = 0.76) and playing as a team (51)(μ = 4.04, σ = 0.71). Most participants also agreed that the enjoyed getting badges (45)(μ = 3.77, σ = 0.85), actively tried to get badges (46)(μ = 3.81, σ = 0.92) and actively tried to both climb the leaderboard (48)(μ = 3.95, σ = 0.90) and level up (50)(μ = 3.86, σ = 0.79).

4.3.5. Motivation towards AST

The participants felt that the game was somewhat efficient in teaching them about AST (52)(μ = 3.32, σ = 0.99), somewhat motivated them to use AST (53)(μ = 3.14, σ = 0.98) and the participants were somewhat happy to perform physical activities in the game (54)(μ = 3.18, σ = 1.20).

4.3.6. AST opinions

A majority of the participants thought that it is a good idea to use Battleship-AST to promote AST (55)(μ = 3.59, σ = 0.92) and that the game is desirable for AST as it encourages collaboration (58)(μ = 3.68, σ = 0.80). The participants were also neutral to using the game for AST (56)(μ = 3.00, σ = 0.86) and thought that the game was somewhat desirable for AST because of the competition in the game (57)(μ = 3.36, σ = 0.91).

4.3.7. AST intentions

Most participants expect to use AST to school (59)(μ = 3.50, σ = 0.83), however would not use Battleship-AST for AST (60)(μ = 2.77, σ = 0.85).

4.4. Playstyle analysis

All the” Cool teknik” events were recorded from a non-participant perspective, meaning that the recording showed what tiles were taken in real time, but not which player that took them. The observation shows that there we two distinct playstyles providing valuable insights into the strategies and behaviours of the players. The following are the two playstyles:

Taking tiles for the task on the tile: This playstyle appears to be more task-oriented as the players following this approach prioritized tiles that are directly related to tasks they prefer doing. Players are paying close attention to the specific content of the tiles and the requirements of their tasks.

Taking Tiles in Unclaimed Areas or Adjacent to Ships: In contrast to the first playstyle, this approach appears to be more opportunistic. Players adopting this strategy do not limit themselves to tiles directly related to the task but instead seek opportunities in larger areas of unclaimed tiles or areas adjacent to ships. It implies that players are exploring the game board more widely and taking risks by venturing into regions where they may uncover ships.

5. Discussion

5.1. The role of two-stage co-design in increasing motivation and engagement

The development of the persuasive game followed a two-stage co-design process involving children. We administered online surveys at each stage to gather structured feedback. During the initial co-design stage, our focus extended beyond the gameplay mechanics. We actively encouraged children to share their thoughts and suggestions concerning the persuasive game. This co-design exercise enriched the development process and ignited a notable surge in motivation and engagement among the children. Their involvement went beyond gameplay, reflecting a genuine interest in shaping the persuasive game and contributing to a more meaningful and engaging experience.

In the second stage of the co-design process, the children actively participated in a playtest of the game, contributing to heightened engagement and motivation. However, the participants’ neutral responses regarding their satisfaction with the game indicated there is room for enhancements to elevate overall satisfaction. This valuable feedback prompted us to improve the game by introducing features that visually represented a player’s progress, such as points, badges, and the leaderboard. The positive impact of these enhancements was evident in the subsequent evaluation, where more participants expressed a willingness to play the game again and reported increased satisfaction. However, negative responses to certain feedback game features highlighted the need for refining the feedback mechanism within the game to provide more timely and clear responses to players’ actions. A noteworthy positive aspect of the game was its ability to provide a sense of accomplishment to participants upon completing tasks. However, participant feedback also indicated a desire to improve game elements that could captivate and immerse players in a more engaging experience. Many participants expressed that the game fell short in engagement, signalling an area where further refinements and innovations could be implemented to create a more immersive and captivating gameplay experience. Our observations during participants’ gameplay revealed a robust initial engagement, but with repeated playthroughs, some individuals experienced a decline in enthusiasm, potentially attributed to fatigue or boredom.

Given the neutral opinions expressed by participants during the playtest regarding both competition and cooperation aspects, the final iteration of the game underwent enhancements to incorporate more features fostering both elements. Introducing the multiplayer team function allowed participants to collaborate in teams while engaging in friendly competition with opposing teams. Additional features such as the leaderboard, points system, and badges were integrated to stimulate a sense of competition among players further. The final evaluation results validated these improvements, indicating that players perceived a heightened sense of competition in the game compared to earlier versions. However, it is essential to acknowledge that while competition was augmented in the game, contrasting research emphasizes a considerable preference for cooperation and togetherness among children (Lindqvist et al., Citation2018). This provides an alternative perspective, highlighting the significance of collaborative elements over competitive aspects. Despite the enhancements to competition, the study recognizes that values associated with cooperation and a sense of togetherness remain crucial in designing a persuasive and engaging game experience.

The significance of incorporating initial game elements that captivate the interest of all participants is indicated by the potential for obtaining positive responses from players. This aligns with research emphasizing the critical importance of engaging players right from the outset to ensure sustained involvement (Csikszentmihalyi & Csikszentmihalyi, Citation2014). However, the varying challenges and activities presented in the game did not strongly influence participants’ overall perception, as indicated by their neutral opinions. This observation may be attributed to the limited inclusion of Physical Activity or AST activities in the game, with only about four such activities featured. According to Fogg (Citation2009), task variation plays a pivotal role in ensuring the persuasiveness of a system, emphasizing its importance in maintaining player interest and engagement. This highlights the potential for refining the game design to introduce more diverse and engaging tasks. Furthermore, participants’ neutral stance regarding the game content’s alignment with their interests and exercise preferences suggests that the game content may not have fully addressed the diverse interests and preferred exercise styles of the participants. Tailoring game content to individual preferences and exercise inclinations has been identified as a key strategy to significantly enhance engagement and enjoyment (Oinas-Kukkonen & Harjumaa, Citation2009).

The positive perception of game design elements holds significance as it directly influences engagement and user experience (Brown & Cairns, Citation2004). Participants’ satisfaction with game design elements in this context may be attributed to incorporating children’s perspectives, suggesting that involving them in the co-design process contributed to meeting their design preferences. The favourable response of participants to the familiarity with the game content implies that the recognition of game elements may have contributed to improved satisfaction and willingness to play. Familiarity with game content can enhance initial engagement and reduce the learning curve, making the game more accessible and enjoyable (Zhang et al., Citation2016). Furthermore, participants strongly believed in perceiving the game as a persuasive tool for promoting exercise, emphasizing its potential to raise awareness and encourage engagement in physical activity. This aligns with persuasive technology, where interactive systems entertain and effectively engage individuals in adopting desired behaviours (Fogg, Citation2002).

Most participants perceived the game as easy to learn, indicating that the game’s interface and mechanics were intuitive and easily understood. This aligns with the principles of usability and user-centred design, emphasising the importance of creating straightforward and user-friendly interfaces (Ragnemalm et al., Citation2011). Visual appeal, a recognised critical factor in user engagement and satisfaction in interactive systems (Fogg, Citation2002; Lindgaard et al., Citation2006), may contribute to the positive responses observed in this study. However, neutral responses regarding the system’s responsiveness suggest the need for improvement to enhance engagement. Responsive controls are essential for a positive gaming experience, ensuring that player inputs translate smoothly into actions within the game (Ragnemalm et al., Citation2011). The negative response to sound effects impacting user experience could be attributed to the low sound quality of the systems used during gameplay. Inadequate sound quality, such as low volume, may fail to evoke desired emotions, as other environmental sounds could mask it (Toprac & Abdel-Meguid, Citation2011). Effective sound design is crucial for creating an immersive gaming experience, but its impact can be compromised if the audio output is suboptimal.

The participants’ feedback during evaluation presents an encouraging and affirmative response to various game elements, showcasing a positive reception towards the game’s design and features. Notably, elements tied to competition, enjoyment, and the inclination to recommend or replay the game were particularly well-received. The positive reception in these aspects underscores the effectiveness of incorporating competitive elements into the game design, significantly enhancing the participants’ enjoyment and engagement levels. Competitive features are known to not only foster player motivation but also amplify the sense of immersion in the gaming experience (Oinas-Kukkonen & Harjumaa, Citation2009). However, it is worth acknowledging that certain studies caution against the potentially adverse consequences of excessive competition, emphasizing the importance of striking the right balance (Hakulinen et al., Citation2013). The critical role of enjoyment in gameplay cannot be overstated, as it serves as a linchpin for sustaining engagement and motivation during the gaming session (Vorderer et al., Citation2004). The participants’ enjoyment and the resultant positive experience can contribute to prolonged engagement and a desire to revisit the game, indicative of a satisfying gaming encounter (O’Brien & Toms, Citation2008; Suh et al., Citation2018). These aspects collectively emphasize the importance of designing games that maximize enjoyment and engagement, as they significantly impact the overall player experience. Additionally, the participants’ willingness to recommend or replay the game reflects a positive disposition towards the game, hinting at its potential adoption and continued usage among the target audience. This positive word-of-mouth and the desire for replayability highlight a gratifying and enjoyable gaming experience. On the aspect of game difficulty, participants perceived the level as somewhat appropriate, emphasizing the significance of striking a balance in game difficulty (Sweetser & Wyeth, Citation2005). An optimal level of challenge is crucial for keeping players engaged and motivated, ensuring an enjoyable and immersive gaming experience (Csikszentmihalyi & Csikszentmihalyi, Citation2014; Sweetser & Wyeth, Citation2005). Games that are either too easy or too difficult can lead to player disinterest or frustration, underscoring the importance of carefully calibrating game difficulty to cater to diverse player preferences and skill levels (Csikszentmihalyi & Csikszentmihalyi, Citation2014). However, addressing aspects related to game immersion and conclusion satisfaction could potentially enhance the overall gaming experience, aligning it more closely with players’ expectations and preferences.

The game positively enhanced awareness about AST of participants. While the game managed to motivate participants to use AST through the game, there is potential for enhancing the persuasive elements that encourage the use of AST. Gamification strategies, such as rewards, challenges, and competition, effectively motivate individuals and drive behaviour change (Hamari et al., Citation2014; Laine & Lindberg, Citation2020). The game was successful in fostering a positive attitude towards AST engagement. Positive emotions associated with AST are critical for sustained engagement and adherence to exercise regimes in general and AST in particular.

Battleship-AST as a tool for promoting AST was perceived as a viable and positive approach. Previous research suggests that utilizing innovative and engaging methods, like game-based approaches, can effectively promote healthy behaviours like active transportation (Coombes & Jones, Citation2016; Oyelere et al., Citation2022). Furthermore, participants found the game desirable for promoting AST due to its collaborative and competitive elements. This aligns with existing literature emphasizing the role of collaboration and competition in promoting sustainable modes of transportation like walking and biking (Laine et al., Citation2020; Yen et al., Citation2019). Collaborative gameplay can create a sense of community and motivate participants to engage in AST collectively, contributing to sustainable transportation choices. Similarly, incorporating competition within the game could motivate participants to engage in AST actively. Previous research suggests collaboration among players in AST intervention was more desirable than competition (Lindqvist et al., Citation2018). Research suggests that students have different behavioural profiles and are motivated by different persuasive elements, which makes it essential to consider different profiles when developing gamified systems (Hamari & Tuunanen, Citation2014; Orji et al., Citation2014). The participants’ inclination towards collaboration over competition shows that many students are socializers, prefer interacting with their peers, and are less motivated to participate in competitive settings (Lindqvist et al., Citation2018; Oliveira et al., Citation2022). While participants saw the potential of Battleship-AST for promoting AST, they might have reservations or uncertainties regarding its exclusive use for this purpose. Addressing these concerns and integrating AST-promoting elements more seamlessly within the game could enhance its perceived effectiveness. Regarding AST intentions, most participants expressed an intention to use AST to school, signifying a favourable disposition towards adopting AST for their school commute. Notably, a recent study involving participants shows that most are already engaging in AST (Jingili et al., Citation2023), suggesting a pre-existing inclination toward sustainable commuting methods. Encouraging AST aligns with efforts to promote a healthier lifestyle and reduce the environmental footprint associated with motorized transportation (de Nazelle et al., Citation2011; Frank et al., Citation2010). However, addressing their neutral stance on using the game specifically for AST and understanding their reservations can guide refinements to optimize the game’s potential for promoting AST effectively.

5.2. Exploring the potential of persuasive technology features

The participants’ feedback regarding persuasive technology and gamification features highlights the potential of integrating these components into the game design, underscoring their substantial impact on player engagement, enjoyment, and the overall gaming experience. Climbing the leaderboard, leveling up, collaborative gameplay, and earning badges emerged as particularly appealing features, emphasising the potential of incorporating these elements to optimise the gaming experience. Climbing the leaderboard taps into individuals’ innate desire for achievement and recognition, encouraging continued participation and enhancing motivation (Deterding et al., Citation2011). Similarly, levelling up represents a progression mechanism that not only enhances a sense of accomplishment but also fosters sustained engagement by providing clear goals and a sense of advancement within the game (Hamari et al., Citation2014). Moreover, collaborative gameplay aligns with the social aspect of persuasive technology, encouraging cooperation, enhancing social interaction, and promoting a sense of community among players (Oinas-Kukkonen & Harjumaa, Citation2009). Collaborative gameplay can boost engagement by creating a supportive environment where players collaborate towards common objectives. On the other hand, badges act as tangible symbols of achievement, providing intrinsic motivation by appealing to the players’ desire for recognition and accomplishment. Moreover, participants actively striving to earn badges and aiming to climb the leaderboard and level up underline the motivational power of gamification elements in promoting sustained engagement. Furthermore another game’s significant feature lies in its non-turn-based mechanics, a critical factor in promoting sustained engagement. Unlike traditional turn-based games, this design encourages players to engage continuously, fostering a sense of continuous play and ultimately enhancing the overall player experience (Vanbrabant et al., Citation2022).

In the dialogue support category, our system employs auditory cues, specifically praise-oriented sounds within the game, to motivate users during gameplay. A celebratory sound is triggered when a player selects a tile containing a ship, while a disheartening sound is played when a tile without a ship is chosen. These auditory cues serve to sustain player engagement and enthusiasm by instilling a sense of anticipation and hope in their quest to discover ships. The use of sounds to evoke emotions and drive engagement aligns with findings in the field of persuasive technology (Toprac & Abdel-Meguid, Citation2011). Research has shown that well-designed auditory feedback can significantly impact user experience and engagement (Toprac & Abdel-Meguid, Citation2011).

Furthermore, we utilized a virtual reward system based on points and badges to acknowledge and reinforce players for their gameplay efforts. Players who successfully locate a greater number of ships are awarded more points and badges, reinforcing a positive feedback loop and encouraging continued participation and engagement. This approach draws from the extensive literature on gamification, which emphasizes the effectiveness of rewards in motivating and engaging users (Hamari et al., Citation2014). Introducing intangible rewards aligns with our system’s intent to encourage continued participation and engagement (Krath & von Korflesch, Citation2021).

In the design of our system, we implemented a persuasive feature centered around similarity to captivate students and promote their engagement with the AST persuasive game. By presenting a game akin to the classic battleship game but integrating a novel aspect wherein players must complete a suggested AST activity to uncover the next tile, we sought to create a sense of familiarity and relatability, enhancing overall user engagement and involvement. This strategy is in line with research suggesting that integrating familiar elements into games can enhance engagement (Oinas-Kukkonen & Harjumaa, Citation2009). It aligns with the idea that leveraging pre-existing knowledge and experiences can make learning more engaging and enjoyable (Zhang et al., Citation2016).

Moreover, we aimed to enhance the appeal of the game through a liking persuasive feature. Building upon the previous version, we meticulously improved the visual aspects of the game, including colors, icons, and overall aesthetics, with the intention of making the game more visually appealing and attractive to the student demographic. These enhancements were aimed at positively influencing the players’ liking and enjoyment of the game, further promoting sustained engagement and participation. Research supports the notion that aesthetics can significantly influence user liking and enjoyment, thus promoting sustained engagement (Ragnemalm et al., Citation2011).

5.3. Limitations

While this study has yielded valuable insights, it is essential to acknowledge several inherent limitations. Firstly, numerous participants in the ideation workshop were unable to create solution sketches due to time constraints; an increased number of sketches might have influenced task design differently. Moreover, it should be noted that each participant played the Battleship-AST game only once, which precludes any definitive conclusions regarding the long-term effects of Battleship-AST. Secondly, despite the inclusion of a reasonably sized group of 22 participants from the Cool teknik event, it is important to recognize that this sample size, while suitable for a large-scale user test, may not be sufficiently large to facilitate deeper, more comprehensive insights into the current state of the game. Thirdly, the study’s sample exclusively comprised participants from the city of Skellefteå in northern Sweden, thereby necessitating further research involving a more diverse pool of participants from either different geographic regions within the country or participants from other nations. Such diversification is essential to enhance the generalizability of the study’s findings.

6. Conclusions

This research provided a comprehensive exploration of the two-stage game co-design process utilized in developing a Battleship-AST game. Additionally, it examined participants’ perceptions of the motivational and engaging aspects of the persuasive technology and gamification features integrated into the final version of the game. Through this evaluation, we gained valuable insights into how these features impacted participants’ motivation to engage with AST through gameplay. The research also involved refining the Battleship-PA low-fidelity prototype through active collaboration with school children in co-design, followed by a testing phase at a tech event in Skellefteå, Sweden.

The two-stage co-design process was a key contributor to children’s heightened motivation and engagement. Actively involving school children in the design process not only facilitated the acquisition of valuable insights but also ignited motivation, interest, and active participation among the participants. Our evaluation of the persuasive technology features within the game revealed their significant impact on player motivation and engagement. Elements such as competition, collaboration, enjoyment, and rewards were well-received, underscoring their importance in enhancing overall engagement. The inclusion of leaderboard, and badges played a pivotal role in encouraging continued participation and fostering a positive feedback loop. However, feedback highlighted areas for improvement, particularly in refining elements such as feedback on actions and immediate attention capture for a more engaging experience. Tailoring game content to individual preferences and AST inclinations was also identified as a potential avenue for increasing overall engagement.

7. Future work

Future co-design and persuasive game development research should explore comparative studies to assess the benefits and challenges of co-design versus traditional approaches. Additionally, there is a need to investigate the long-term effects of co-designed persuasive games on user behaviour. Moreover, research could explore areas that need to be addressed in the game, such as measuring real-life progress. Introducing statistics such as calories burned and total distance travelled could provide players with tangible indicators of their AST efforts, potentially enhancing their motivation to participate actively. The levelling system in the game can also be further refined to offer more substantial rewards beyond just badges. Exploring alternative ways for players to earn experience points (XP) could add depth and variety to the game, potentially increasing player engagement and motivation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Nuru Jingili

Nuru Jingili is a lecturer and researcher in the field of computer science, with a focus on Persuasive and gamified Technologies, Virtual Reality, Human-Computer Interaction and Artificial Intelligence. She has extensive experience as a project manager and coordinator for initiatives like the GreenGaming and WeSteam projects.

Solomon Sunday Oyelere

Solomon Sunday Oyelere is Associate Professor of Pervasive and Mobile Computing at the Department of Computer Science, Electrical and Space Engineering, Luleå University of Technology. He received a PhD in Computer Science from University of Eastern Finland in 2018. His research interest includes mobile and context-aware computing, educational technology, human-centred AI, immersive and interactive systems.

Simon Malmström Berghem

Simon Malmström Berghem has Master’s Degree from Luleå University of Technology, Sweden in 2023.

Robert Brännström

Robert Brännström is Assistant professor in Pervasive and Mobile Computing. Deputy Head of Department and Head of Undergraduate education at the Department of Computer Science, Electrical and Space Engineering. Researcher in applied computer game technologies and technology project leader for active school transportation in northern Sweden.

Teemu H. Laine

Teemu H. Laine is Professor of Digital Media at Ajou University. Has a PhD from University of Eastern Finland in 2012. Teemu’s research interests include XR, games, context-awareness, educational technology, HCI, well-being technology, and applied AI. He has published over 100 papers while researching in Europe, Asia, and Africa.

Anna-Karin Lindqvist

Anna-Karin Lindqvist is Associated professor in Physiotherapy 2021. Member of the Philosophical faculty committee at Luleå university of technology 2021-Extensive experience of school-based intervention research and health promotion research. Leader of the research team that created the SICTA intervention (Sustainable Interventions for Children Transporting Actively).

Stina Rutberg

Stina Rutberg is Associated professor in Physiotherapy 2020. Director of PhD education at the department of Health, Education and Technology. Extensive experience of children’s physical activity research, school-based interventions, and instrument development.

References

- Agbo, J. F., Oyelere, S. S., Suhonen, J., & Laine, T. H. (2021). Co-design of mini games for learning computational thinking in an online environment. Education and Information Technologies, 26(5), 5815–5849. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10515-1

- Brown, E., & Cairns, P. (2004). A grounded investigation of game immersion. In CHI’04 extended abstracts on human factors in computing systems, pp. 1297–1300. https://doi.org/10.1145/985921.986048

- Chou, Y. (2015). Actionable gamification: Beyond points, badges, and leaderboards, Octalysis Media.

- Coombes, E., & Jones, A. (2016). Gamification of active travel to school: A pilot evaluation of the beat the street physical activity intervention. Health & Place, 39, 62–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2016.03.001

- Corepal, R., Best, P., O’Neill, R., Tully, M. A., Edwards, M., Jago, R., Miller, S. J., Kee, F., & Hunter, R. F. (2018). Exploring the use of a gamified intervention for encouraging physical activity in adolescents: A qualitative longitudinal study in Northern Ireland. BMJ Open, 8(4), e019663. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019663

- Csikszentmihalyi, M., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2014). Toward a psychology of optimal experience, Flow and the foundations of positive psychology: The collected works of Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. 209–226.

- Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly, 13(3), 319–340. https://doi.org/10.2307/249008

- de Nazelle, A., Nieuwenhuijsen, M. J., Antó, J. M., Brauer, M., Briggs, D., Braun-Fahrlander, C., Cavill, N., Cooper, A. R., Desqueyroux, H., Fruin, S., Hoek, G., Panis, L. I., Janssen, N., Jerrett, M., Joffe, M., Andersen, Z. J., van Kempen, E., Kingham, S., Kubesch, N., … Lebret, E. (2011). Improving health through policies that promote active travel: A review of evidence to support integrated health impact assessment. Environment International, 37(4), 766–777. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2011.02.003

- Deterding, S., Dixon, D., Khaled, R., Nacke, L. (2011). From game design elements to gamefulness: Defining” gamification. In Proceedings of the 15th international academic MindTrek conference: Envisioning future media environments, pp. 9–15.

- Druin, A. (2002). The role of children in the design of new technology. Behaviour and Information Technology, 21(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/01449290110108659