Abstract

While the popularity of virtual influencers in influencer marketing is on the rise, little is known about the reasons behind their increasing popularity. Furthermore, there is also a dearth of research examining why and how virtual influencers could be more effective than human influencers in influencing consumer purchase decisions. Drawing on the concept of perceived authenticity of influencers and machine heuristic, this study investigates the effects of influencer type (virtual influencer vs. human influencer) on the perceived authenticity of consumers. In addition, we also explore if machine heuristic will moderate the perceived authenticity of consumers and whether trust in influencers and purchase intentions will be subsequently associated with the perceived authenticity of the influencer. Results from an online between-subjects designed experiment (N = 130) indicated that virtual influencers were unexpectedly perceived as more authentic than human influencers. Additionally, the perceived authenticity of virtual influencers significantly increased among those with a strong belief in the machine heuristic. Subsequently, we found a positive association between the perceived authenticity of influencers and the extent of consumers’ trust in them. Additionally, trust in influencers was positively associated with consumers’ intention to purchase the products they promoted by the influencers. These findings provide valuable insights into the use of virtual influencers for marketing purposes. Further theoretical and practical implications are discussed.

1. Introduction

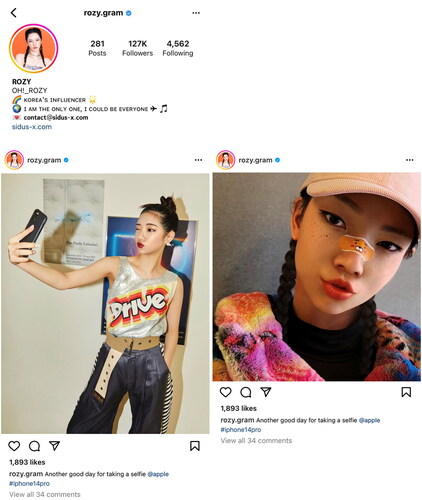

Virtual influencers are computer-generated virtual characters who resemble human influencers created to affect people’s decisions (Andersson & Sobek, Citation2020; Molin & Nordgren, Citation2019). Recent trend reports suggest that 75% of social media users between 18 and 24 follow at least one virtual influencer (Dencheva, Citation2023a), and 40% of them purchased products recommended by virtual influencers as of March 2022 (Dencheva, Citation2023b). In alignment with the trend, many brands in diverse product categories, including fashion, automobile, and beauty, have already begun partnering with virtual influencers (e.g., Chevrolet and American Tourister with Rozy; ).

With the soaring interest in using virtual humans for influencer marketing on social media, scholars have started to explore whether and how virtual influencers could replace the traditional role of human influencers (e.g., Audrezet & Koles, Citation2023; Deng & Jiang, Citation2023; Wan & Jiang, Citation2023). However, it merits attention that previous studies comparing virtual influencers with human influencers have suggested that people tend to evaluate virtual influencers as less authentic than humans (Audrezet et al., Citation2020; Choudhry et al., Citation2022; Lou et al., Citation2023; Sands, Ferraro, et al., 2022). Such studies demonstrate that virtual influencers should be perceived as less authentic than human influencers as they lack transparency in openly communicating commercial interests (Audrezet et al., Citation2020; Choudhry et al., Citation2022). Given that perceived authenticity is one of the critical factors known to predict consumer behavior (e.g., purchase intention) in influencer marketing (Kim & Kim, Citation2021; Lou, Citation2022), the results of previous studies highlight the necessity for further investigation into the theoretical mechanism underlying the widespread adoption of virtual influencers in marketing. Consequently, this leads to a critical research question: Why would consumers follow virtual influencers when the perceived authenticity of virtual influencers is inherently lower than that of human influencers? In other words, under what circumstances could virtual influencers be more persuasive than human influencers?

Intriguingly, the concept of machine heuristic (i.e., “generalized positive beliefs or stereotypes about what machines are like and how they perform [e.g., objectivity]”; Sundar & Kim, Citation2019) suggests a potential missing link between the relatively weaker authenticity of virtual influencers and their recent adoption in influencer marketing. The concept of machine heuristic demonstrates that individuals who tend to believe machines are unbiased are likely to evaluate their experience with virtual entities positively, as these entities exhibit cues reminiscent of machines (Sundar, Citation2008; Sundar & Kim, Citation2019). Considering that virtual influencers are computer-generated “machine” characters, their identity as influencers may be moderated by individuals’ prior belief in machine heuristics. For example, consumers with a favorable view of machine capabilities might perceive and evaluate virtual influencers more positively. Furthermore, since machine heuristics are believed to enhance the perceived authenticity of virtual entities (Huang & Jung, Citation2022), individuals with a strong belief in the objectivity of machines could perceive and evaluate virtual influencers as more objective and, consequently, as more authentic influencers. Thus, the concept of machine heuristic could theoretically explain why and how consumers may perceive virtual influencers as more authentic.

Taken together, the current study aims to provide a theoretical understanding of why and how virtual influencers could become compelling alternatives to human influencers through the theoretical lenses of perceived authenticity and machine heuristic. Specifically, this research explores the potential moderating role of machine heuristic in providing theoretical contributions for why and how virtual influencers can be perceived as more authentic than human influencers. Additionally, we investigate the sequential relationship between perceived authenticity, consumers’ trust, and their purchase intentions for the advertised product.

2. Literature review

2.1. Human vs. virtual influencers

In the domain of influencer marketing, a new category of influencers known as virtual influencers has recently emerged. Recent advancements in technology have enabled the development of humanized virtual influencers nearly indistinguishable from real humans (Hofeditz et al., Citation2022). These virtual influencers are increasingly employed by brands to promote their products, blurring the lines between virtuality and reality (Moustakas et al., Citation2020). For instance, Lil Miquela (@lilmiquela), has been recognized as one of the 25 most influential people by Time Magazine, along with other popular figures (Byun & Ahn, Citation2023).

The employment of virtual influencers offers distinct benefits (Koles et al., Citation2024). As virtual influencers are created and managed by digital technologies such as computer graphics or artificial intelligence technology, companies (e.g., brands) can meticulously control the appearance of virtual influencers to be favorable for audiences (Yu et al., Citation2024). Companies can also control interactions with consumers to prevent potential risks of public relations issues or scandals (Sands, Ferraro, et al., 2022; Sands, Campbell, et al., 2022; Thomas & Fowler, Citation2021). Moreover, the virtual nature of virtual influencers enables innovative storytelling techniques, such as displaying fashion items on fire on a virtual stage, enhancing user engagement (Audrezet & Koles, Citation2023).

Nevertheless, virtual influencers present notable drawbacks due to their virtual nature. Developed and managed by companies, their motivation for endorsements is inherently profit-driven. Associated with their lack of tangible existence, such motivation for endorsement raises concerns about the authenticity of their recommendations (Wong, Citation2018). As a result, their virtual identity and the lack of transparency regarding their commercial motives can diminish their perceived trustworthiness (Choudhry et al., Citation2022). Furthermore, disclosing the virtual influencer’s origin has been found to diminish perceptions of parasocial relationships, adversely affecting their credibility (Lim & Lee, Citation2023). Despite being controlled by artificial intelligence, virtual influencers are also vulnerable to consumer subversion and sabotage when their identity violates consumer expectations (Sands, Ferraro, et al., 2022), as seen in the collaboration between Lil Miquela and Calvin Klein (Cusumano, Citation2019).

Taking into account the identified advantages and disadvantages of virtual influencers, previous studies have delved into a comparative investigation of human and virtual influencers, assessing the viability of virtual influencers as effective alternatives to human counterparts. These attempts have identified and tested factors contributing to the distinctive effects of human and virtual influencer endorsements by adopting pre-existing theories and concepts. Notably, one line of research findings demonstrates that virtual influencers may not be as effective as human influencers in consumer persuasion. Such studies have found that virtual influencers are considered less likable (Böhndel et al., Citation2023), less authentic (Arsenyan & Mirowska, Citation2021; Moustakas et al., Citation2020; Wan & Jiang, Citation2023), less human-like (Arsenyan & Mirowska, Citation2021; Franke et al., Citation2022; Hofeditz et al., Citation2022; Molin & Nordgren, Citation2019; Nissen et al., Citation2023), develop weaker parasocial relationships (Lim & Lee, Citation2023; Zhou et al., Citation2024), and perceived less credible (Li et al., Citation2023; Ozdemir et al., Citation2023; Yang et al., Citation2023), and trustworthy (Hofeditz et al., Citation2022; Nissen et al., Citation2023; Sands, Campbell, et al., 2022; Wan & Jiang, Citation2023) than human influencers, resulting them being generally less persuasive (for detailed findings, see ).

Table 1. Detailed findings from studies comparing human and virtual influencers.

However, another line of research findings suggests that the persuasiveness of virtual influencers may be enhanced under certain circumstances. For example, Zhou et al. (Citation2024) found that, while virtual influencers generally form weaker parasocial relationships, virtual influencers in a video modality, as compared to those in images, can strengthen these relationships. Additionally, the perceived credibility of virtual influencers was found to diminish when they use rational language, rather than emotional language (Ozdemir et al., Citation2023), or when they engage in active interaction with users (Yang et al., Citation2023). Furthermore, the study of Mirowska and Arsenyan (Citation2023) demonstrates that people with high cognitive empathy and low emotional disassociation may find virtual influencers to be more socially attractive than human influencers. This study specifically suggests that the attributes found to be weaker in virtual influencers, such as credibility, trustworthiness and parasocial relationship, can be enhanced depending on the personality traits of individuals (e.g., empathy; Mirowska & Arsenyan, Citation2023), the degree of interaction from the virtual influencers (Yang et al., Citation2023), their language (Ozdemir et al., Citation2023), and the modality of communication they employ (Zhou et al., Citation2024).

Despite these findings, the question of whether the perceived authenticity of virtual influencers can be improved under certain conditions remains largely unexplored, especially from the perspective of human-computer interaction. Even though people recognize virtual influencers as artificially created social entities, it is noteworthy that they also acknowledge virtual influencers as fulfilling roles similar to human influencers as social media celebrities (i.e., “authentically fake”; Arsenyan & Mirowska, Citation2021; Lou et al., Citation2023; Mrad et al., Citation2022). This perception of virtual influencers being “authentically fake” might result in more positive outcomes, as followers are aware that they are interacting with deliberately crafted content (Arsenyan & Mirowska, Citation2021; Lou et al., Citation2023). In an ongoing effort to provide a theoretical understanding of the nuanced and distinctive effect of virtual influencers on consumer persuasion, the current study discusses the concept of the perceived authenticity of influencers.

2.2. Perceived authenticity of influencers

The authenticity of influencers is known to play an important role in determining the persuasiveness of messages in the domain of influencer marketing (Kim & Kim, Citation2021). Byun and Ahn (Citation2023) demonstrate that the goal of both virtual and human influencers is to gain the authenticity perception from their audience. For this reason, the concept of authenticity is deemed one of the key constructs that could provide a theoretical understanding of how virtual influencers might be similar to or differ from human influencers. Borrowing the definition of authenticity from Lee (Citation2020), the perceived authenticity of influencers can be defined as the extent to which the communicative behaviors of influencers are perceived to be genuine and true.

A previous study suggests that virtual influencers can be perceived as para-authentic if the user’s cognition of the virtual entity genuinely connects with an actual entity it replicates (Lee, Citation2004). In other words, virtual influencers can be viewed as nearly authentic (i.e., real) when their identity aligns with the identity they claim as human influencers (Byun & Ahn, Citation2023; Huang & Jung, Citation2022). Virtual influencers are virtual humans crafted using computer graphic technology, aimed at mimicking the appearance and behaviors of human influencers (Audrezet & Koles, Citation2023; Moustakas et al., Citation2020). As individuals discern cognitive connections (e.g., similarities) between virtual influencers and human influencers, they might perceive virtual influencers as much authentic as human influencers. Indeed, it has been found that people perceive virtual influencers to be “authentically” fake, delivering deliberately constructed narratives (Lou et al., Citation2023). Nonetheless, it is noteworthy that virtual influencers are often found to be perceived as less authentic than their human counterparts (Andersson & Sobek, Citation2020; Arsenyan & Mirowska, Citation2021; Huang & Jung, Citation2022). This discrepancy might arise due to the definition of authenticity in influencer marketing, which often incorporates the concept of transparency (Audrezet et al., Citation2020).

According to the authenticity management framework (Audrezet et al., Citation2020), a perception of influencers’ authenticity can be created by providing a truthful disclosure of the partnership with brands (i.e., transparency) and expressing honest opinions about the product. This framework further demonstrates the importance for influencers to communicate the “behind-the-scenes” efforts, such as how thoroughly they evaluate a product before endorsing it, in addition to acknowledging the partnership (i.e., commercial interests; Audrezet et al., Citation2020), to establish authenticity perception from consumers. Given this notion, the fact that virtual influencers are artificial endorsers purposefully created for promoting brands and products might lead consumers to evaluate virtual influencers as obviously having commercial purposes.

Furthermore, when the perception of influencers’ authenticity concerns how influencers reflect autonomous and self-determining “true” selves (Kernis & Goldman, Citation2006; Ilicic & Webster, Citation2016), the perceived authenticity of virtual influencers should be lower than that of human influencers since virtual influencers’ immanent purpose of product endorsement is non-autonomous (i.e., programmed) advertising. In support of this idea, a previous finding based on the authenticity management framework also suggests that virtual influencers are likely to be perceived as less authentic than human influencers when the perceived authenticity of influencers is associated with transparency (Audrezet et al., Citation2020). The study of Conti et al. (Citation2022) also points out that individuals might become skeptical about whether virtual influencers could provide reliable recommendations as authentic endorsers as they lack transparency in establishing the authenticity perception.

Overall, previous studies consistently suggest that virtual influencers may be perceived as less authentic than human influencers due to their lack of transparency when conveying truthfulness and genuineness. Therefore, when defining authenticity in terms of realness, truthfulness, and genuineness, we predict that people will perceive human influencers as more authentic than virtual influencers. Accordingly, we first posit:

H1. Human influencers will induce a greater perception of authenticity than virtual influencers.

2.3. The moderating role of machine heuristic

If the perceived authenticity of human influencers is theoretically higher than that of virtual influencers, it raises questions of why and how virtual influencers can be, and currently are, adopted by consumers. In seeking to understand this phenomenon, the current study employed the modality, agency, interactivity, and navigability (MAIN) model (Sundar, Citation2008) to explain the theoretical mechanisms underlying authenticity perceptions toward virtual influencers. According to this model, technological affordances influence users’ heuristics, which in turn shapes their perceptions of technology’s quality. Within this theoretical framework, the concept of machine heuristic—defined as “individuals’ positive beliefs about inherent characteristics of machines such as being objective or unbiased” (Lee, Citation2024; Sundar & Kim, Citation2019)—provides a potential explanation for the recent popularity of virtual influencers.

The concept of machine heuristic suggests that when a technological interface exhibits a machine-like appearance or identity, people may apply their machine heuristic to evaluate the actions of the machine (Koh & Sundar, Citation2010; Lee, Citation2024). For instance, technological cues that possess machine identity may lead users who hold positive beliefs about the capabilities of machines to perceive the technology as more objective and unbiased compared to humans. This perception can positively bias their evaluations of the technology (Sundar & Kim, Citation2019). Such biases cognitively stem from the prior belief that machines possess an “intelligence or ability that is not just human-like but surpasses that of humans” (Huang & Jung, Citation2022; Sundar, Citation2020, p. 79). In alignment with this idea, previous studies have found that machine heuristic moderates the extent to which technology users perceive the ability of machines. For example, studies have shown that individuals with a high machine heuristic perceive web agents as more secure (Sundar & Kim, Citation2019) and voice assistants as more useful (Lee et al., Citation2022).

Based on the concept of machine heuristic and supported by empirical evidence, we hypothesize that individuals with a stronger (i.e., positive) belief in the capabilities of machines may perceive virtual influencers as more authentic than their human counterparts. This is because, to the extent that the machine heuristic leads people to regard virtual influencers as unbiased and more objective (i.e., automation bias; Mosier et al., Citation1996; Huang & Jung, Citation2022), the perceived lack of transparency in virtual influencers might be offset. Essentially, because virtual influencers are created and operated through computer technologies (Andersson & Sobek, Citation2020; Yu et al., Citation2024), they may be seen as more error-free and thus more genuine when endorsing brands and products.

Nonetheless, it is important to note that the effect of the machine heuristic may vary across individuals, as it is an intrinsic belief developed by their past experiences (Lee, Citation2024; Sundar & Kim, Citation2019). In other words, only individuals with a stronger belief in the machine heuristic may perceive virtual influencers as more authentic than human influencers. Conversely, individuals with a weaker belief in the machine heuristic might find the machine identity of virtual influencers less relevant to their evaluations, leading them to perceive human influencers as more authentic than their virtual counterparts. In summary, considering the individual differences in machine heuristic (Lee, Citation2024), we predict that it will moderate the degree to which people perceive virtual influencers as authentic. Thus, we posit:

H2. The machine heuristic will moderate the effects of influencer type on perceived authenticity such that the perceived authenticity of virtual influencers will be heightened to a greater extent for those who have a strong belief in the capabilities of machines.

2.4. Perceived authenticity and trust

Trust in influencers refers to the belief that influencers can help individuals achieve their goal of purchasing quality products in online shopping (Lee, Citation2018). Previous research suggests that developing trust in influencers is not only based on endorsing the quality of the product but also on the sincerity of the influencer, which is associated with authenticity (Portal et al., Citation2019; Sung & Kim, Citation2010). In the domain of influencer marketing, the authenticity of influencers is often linked to their intention to promote a product for external compensation (Boerman et al., Citation2017; Evans et al., Citation2017). This means that people trust influencers based on their genuine intention to recommend a product. Therefore, if influencers promote products solely for (excessive) financial gain rather than a pure motive of recommendation, consumers may doubt the sincerity of influencers and feel more vulnerable while shopping online (Kim & Kim, Citation2021). That is, consumers may evaluate that the influencers are not sincerely reducing the uncertainty of the product or service, but instead increasing the vulnerability of online shopping. Conversely, when influencers make recommendations based on sincere advice and proper product evaluation, people can trust that influencers are indeed helpful for their shopping, even if the recommended product is a sponsored item. Based on the reasoning, we posit that the perceived authenticity of influencers will be positively associated with trust in them.

H3. Perceived authenticity of influencers will be positively associated with trust in influencers.

2.5. Trust and purchase intention

Trust in influencers has been deemed a key factor that drives consumers’ purchase intentions in the realm of online marketing. Previous studies demonstrate that trust in influencers can increase the consumers’ purchase intentions of the products endorsed by influencers (Alkhalifah, Citation2021; Dutta & Bhat, Citation2016; Lou & Yuan, Citation2019; Rashid et al., Citation2022; Yoon, Citation2002). This is because trust creates a sense of security and helps consumers alleviate the fear of embracing uncertainties in transactions, making users more willing to accept vulnerability by mitigating the perceived risk when making a purchase decision (Lu et al., Citation2016; McKnight et al., Citation2002). In support of this notion, previous studies have empirically established the positive relationship between consumer trust and purchase intentions in various contexts such as online websites (Djafarova & Rushworth, Citation2017; Schouten et al., Citation2020), e-commerce streaming (Guo et al., Citation2021; Liu et al., Citation2021), and social media commerce (Alkhalifah, Citation2021; Dutta & Bhat, Citation2016; Rashid et al., Citation2022). Worthy of note, a recent study on influencer marketing has found that consumers’ trust in influencers, induced by perceived authenticity, can enhance the purchase intentions of consumers by reducing their decision costs in e-commerce (Liu et al., Citation2022). Based on sound empirical evidence, we posit that trust in influencers will be positively associated with consumers’ purchase intentions of the product promoted by the influencers.

H4. Trust in influencers will be positively associated with purchase intentions of the product promoted by the influencers.

3. Method

3.1. Research design

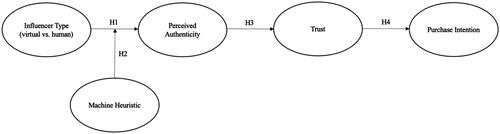

An online experiment with a between-subjects design was conducted, comparing virtual influencers to human influencers. This study employed a machine heuristic as a moderating variable, with perceived authenticity and trust serving as serial mediators, and purchase intention as the outcome variable. presents a holistic view of the proposed research model.

3.2. Participants

From November to December 2022, we recruited a total of 156 participants through the human-subject pool recruiting system of a public university in Western Europe. It should be noted that the current study used the same images of existing virtual influencers for both the virtual and human influencers conditions to prevent confounding effects related to the influencers’ attractiveness and human-likeness. Consequently, 10 participants assigned to the human influencers were excluded after failing the manipulation check, as they already knew the presented influencers were virtual influencers prior to participating in the study. Additionally, 16 participants who did not complete their survey were also removed from the study. As a result, data from 130 participants were used in the subsequent analyses, with 53% (N = 69) experiencing the virtual influencers condition and 47% (N = 61) experiencing the human influencers condition. The average age of participants was 21.27 years (SD = 3.03), ranging from 18 to 30. Of the participants, 66.2% (N = 86) were female, and 33.8% (N = 44) were male. The gender of participants was approximately balanced across the two conditions to control the potential gender effects.

3.3. Stimuli

To avoid the possible confounding effects of virtual figures’ attractiveness and ensure that participants in the human influencer condition believe they are viewing human influencers, a pilot test was conducted. Through a pilot test (N = 23), we chose two virtual influencers among five existing virtual influencers as the final stimuli for our experiment because the attractiveness rating of two virtual influencers did not deviate much from each other and the ratings were close to the median value: Lucy (M = 5.83, SD = 0.83) and Rozy (M = 5.87, SD = 0.87). Worthy of note, the same Instagram photos of Lucy and Rozy were used in both virtual influencer and human influencer conditions to control for differences in physical attractiveness and humanness perception.

Fictional posts were created using Adobe Photoshop based on the existing Instagram posts of Lucy (@ruuui_li) and Rozy (@rozy.gram). Considering the gender-neutrality of a product (Go & Sundar, Citation2019), a smartphone was selected as a promotion product in the post. Each condition included a profile page and two advertising posts featuring a smartphone as the promoted product. Guided by the previous experiment (Jin et al., Citation2021), both Lucy and Rozy were presented in each condition to strengthen the stimulus effects. Specifically, participants in the virtual influencers condition were exposed to a virtual influencer version of both Lucy and Rozy. Likewise, participants in the human influencers condition were exposed to a human influencer version of Lucy and Rozy. The examples of the experiment stimuli are presented in and .

To manipulate influencer type, we added introductory words to the profile pages of Lucy and Rozy in the virtual influencer condition that indicated their virtual human identity (“All about Virtual Human Lucy” and “Korea’s First Virtual Influencer” were used for Lucy and Rozy, respectively). In contrast, we excluded the word “virtual” in the human influencer condition to manifest human identity (“This is Lucy” was used for Lucy and “Korea’s Influencer” was used for Rozy). The rest of the profile descriptions and advertising post features were kept the same in both conditions, and additional statements were provided to emphasize the influencers’ identities before presenting the stimuli to ensure successful manipulation.

3.4. Procedures

Upon the completion of informed consent, participants were provided with an instruction that elaborated the experimental condition in which they are assigned to, and each participant was asked to either read the two virtual or human influencers’ Instagram profiles (i.e., Lucy’s and Rozy’s) and their advertising posts. After presented with the Instagram profiles and posts of either virtual influencers or human influencers, participants completed an online survey. After finishing the survey, participants were debriefed with the information detailing out the purpose and design of the experiment. After debriefed, participants were compensated with 0.5 course credits following the university’s internal guidelines. To ensure the successful manipulation of the human influencer condition, in which participants were deceived with the information that the (virtual) influencers are real humans, participants who indicated that they recognized the identity of the influencers (i.e., noticing that human influencers are virtual) were excluded from the data analysis.

3.5. Measures

Perceived Authenticity was measured using three 7-point Likert scale items adapted from the study of Moulard et al. (Citation2015). The items “Lucy/Rozy is genuine,” “Lucy/Rozy seems real to me” and “Lucy/Rozy is authentic” were asked to evaluate the perceived authenticity of influencers.

Machine Heuristic was measured using five 7-point Likert scale items from the study of Sundar and Kim (Citation2019). One item (“When machines perform a task, the results are more objective than when humans perform the same task”) was removed from the original set due to a loading below 0.50. This decision aimed to ensure the validity of the measurement model, following the criteria suggested by Kock (Citation2014).

Trust was measured through five 7-point items ranging from not at all (1) to extremely (7), adapted from the study of Jian et al. (Citation2000). Participants were asked to evaluate their trust in influencers based on their impression of Instagram profiles and advertising posts. Items such as “Lucy/Rozy is reliable” were asked.

Purchase Intention was measured using five 7-point Likert scale items adopted from the study of Spears and Singh (Citation2004). Participants were asked to indicate their intention to buy the smartphone promoted in Instagram posts. Items such as “I have intention to buy the advertised product” were asked.

Covariates Perceived Attractiveness of Influencers was measured by a single 7-point scale item, ranging from very unattractive (1) to very attractive (7), adopted from Benzeval et al. (Citation2013). Participants were asked to rate the attractiveness of the presented influencers, Lucy and Rozy. Previous Experience with Influencers was assessed by a single 7-point scale item, ranging from not very much (1) to very much (7), adapted from Cassidy and Eachus (Citation2002). Participants in the virtual influencer condition were asked, “Are you familiar with virtual influencers?” while those in the human influencer condition were asked, “Are you familiar with social media influencers?”

Manipulation Check was conducted to ensure the successful manipulation of the independent variable (i.e., influencer type). Participants in the human influencers condition were asked a dichotomous yes or no question, “Did you know that Lucy and Rozy were virtual influencers before participating in this study?” Participants in the virtual influencers condition were asked, “Please keep in mind that Lucy and Rozy are virtual influencers while answering the following questions” and responded with yes or no to confirm their understanding. The details of the survey items used in this study can be found in .

Table 2. Survey items.

3.6. Data analyses

Given the exploratory nature of the research model, which aimed at exploring the unestablished relationships between variables (Hair et al., Citation2014), the partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) method was employed (see Bagozzi & Yi, Citation1988). Additionally, PLS-SEM was chosen to address the relatively small sample size (Goodhue et al., Citation2012) and the complexity of the path model (Hair et al., Citation2017), which includes a moderation path. WarpPLS 8.0 (Kock, Citation2018) was used as an analytical software to explore complex associations between variables.

4. Results

To mitigate the risk of common method bias (CMB) in the cross-sectional data collected for this study, Harman’s single-factor test (Podsakoff et al., Citation2003) was conducted. The presence of more than one single factor extracted from the measured items using factor analysis indicates that a dataset is not subject to CMB (Cenfetelli et al., Citation2008; Podsakoff & Organ, Citation1986). Results from the factor analysis, including the 20 items under the measurement model, revealed no dominating factor accounting for more than 50% of the variance when employing maximum likelihood extraction and varimax rotation methods. Moreover, the Kaiser criterion (i.e., Eigenvalues > 1) indicated a five-factor solution, explaining 31.29% of the variance. These results indicate that the data in the current study are free from the issue of CMB.

4.1. Measurement validity

The validity of the measurement model was assessed prior to testing the hypotheses. Reflective indices were utilized to evaluate the reliability of the measurement model. Drawing on previous studies (Kock, Citation2014, Citation2018), two criteria were adopted for making decisions regarding item retention and assessing the reliability of the measurement model: 1) item loadings with a p-value below 0.001, and 2) item loadings equal to or greater than 0.50 to ensure measurement validity. Initial analysis, including all original items, indicated that one item from the machine heuristic measure needed to be dropped due to having a loading below 0.50. Consequently, the item was removed to ensure the reliability of our measurement model.

Additionally, composite reliability and Cronbach’s alpha values were assessed to ascertain the internal consistency reliability of measures. Composite reliability and Cronbach’s alpha values for all measured constructs exceeded 0.7, consistent with the criterion suggested for determining the internal consistency reliability of measures (Hair et al., Citation2014; Henseler & Fassott, Citation2010). To confirm the convergent validity of the measurement model, the average extracted variance (AVE) values were assessed. Results from PLS-SEM indicated that the AVE for all constructs exceeded 0.5, ensuring the convergent validity of the measurement model. Lastly, the Heterotrait-Monotrait (HTMT) ratio was assessed via PLS-SEM to ensure the discriminant validity of our measurement model. All constructs had HTMT ratios below 0.9, consistent with the cut-off criterion suggested for determining the discriminant validity of the measured constructs (Maqbool et al., Citation2017). Detailed results of the convergent and discriminant validity testing are presented in and .

Table 3. Reliability analysis of constructs and convergent validity.

Table 4. Discriminant validity (HTMT ratio).

4.2. Hypotheses testing

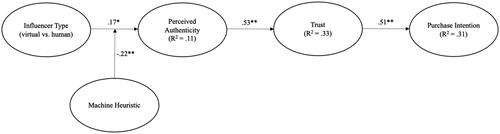

H1 predicted that human influencers will induce a greater perception of authenticity than virtual influencers. Unexpectedly, results showed that the perceived authenticity of virtual influencers (M = 4.19, SD = 1.30) was higher than that of human influencers (M = 3.59, SD = 1.49), β = 0.17, p < 0.05. Perceived attractiveness of influencers and previous experience with influencers included in the model did not have significant effects on perceived authenticity. In sum, H1 was not supported.

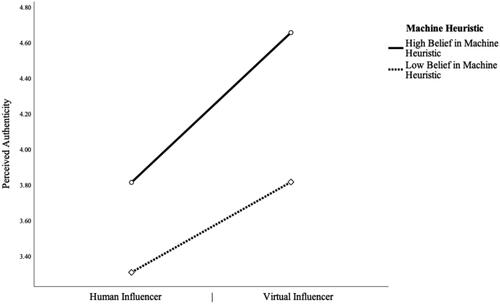

H2 posited that machine heuristic will moderate the effects of influencer type on perceived authenticity such that the perceived authenticity of virtual influencers will be heightened to a greater extent for those who have a stronger belief in the capabilities of machines. Consistent with our prediction, results revealed that the machine heuristic significantly moderated perceived authenticity (β = −0.22, p < 0.01). Individuals with a stronger belief in machine heuristic perceived virtual influencers as more authentic compared to those with a weaker belief in machine heuristic. Machine heuristic, together with the influencer type, explained 11% of the variance in perceived authenticity (R2 = 0.11). Therefore, H2 was supported (see ).

H3 and H4 posited positive associations between perceived authenticity and trust in influencers, and between trust in influencers and purchase intention, respectively. In support of our predictions, the results showed that perceived authenticity is positively associated with trust in influencers (β = 0.53, p < 0.01, R2 = 0.33), and trust in influencers is positively associated with the purchase intention of participants (β = 0.51, p < 0.01, R2 = 0.31). Thus, H3 and H4 were both supported. The results of PLS-SEM are presented in .

4.3. Model fit

To assess the model fit, we used the following criteria suggested by Kock (Citation2018): The p-value of the (1) average path coefficient (APC) and (2) average R-squared (ARS) should be equal to or lower than 0.05, and (3) the values of the average variance inflation factor (AVIF) and 4) the average full collinearity VIF (AFVIF) should be equal to or lower than 3.3. The results from PLS-SEM confirmed that our research model has a good fit: APC = 0.220 (p < 0.05), suggesting a moderate positive relationship between variables (Cohen, Citation2013; Mohamed et al., Citation2018), and ARS = 0.248 (p < 0.05), indicating our model has acceptable explanatory power (Hair et al., Citation2021). The AVIF = 1.184 and AFVIF = 1.680 further support the adequacy of our model.

5. Discussion

The goal of the current study was to explore whether human influencers will be perceived as more authentic than virtual influencers and, if so, how virtual influencers can be more persuasive than human influencers in the context of influencer marketing. Overall, the results of our study showed that while participants evaluated the perceived authenticity of virtual influencers as higher than that of human influencers, the machine heuristic moderated this perception by further amplifying the authenticity for those with a stronger belief in the capabilities of machines. In addition, the perceived authenticity of influencers was found to be positively associated with consumers’ trust in influencers. Trust in influencers was also positively associated with consumers’ intention to purchase the promoted product.

Although most of the hypotheses were supported, the finding in which virtual influencers induced a higher perceived authenticity than human influencers was unexpected. On one hand, a plausible explanation might be that participants had unexpectedly perceived virtual influencers as more transparent than human influencers in communicating commercial interests when we had both virtual and human influencers explicitly communicate the commercial purpose (i.e., promoting a smartphone) using hashtags in the experiment. In other words, this finding suggests that when the commercial purpose is explicitly communicated by both virtual and human influencers, consumers might evaluate virtual influencers as more transparent and authentic than human influencers. In line with this idea, a recent study has found that while the transparent disclosure of sponsorship may harm the credibility perception and attitude toward human influencers, the effects might be reversed when the sponsorship is disclosed by virtual influencers (Kim et al., Citation2023). Similar to the result of the previous study, our finding seems to demonstrate that authenticity may be higher for virtual influencers than for human influencers when the commercial purpose is explicitly communicated in advertising.

On the other hand, the reason why participants in our study evaluated virtual influencers as more authentic than human influencers might be tied to the novelty effects, as discussed in recent studies (e.g., Franke et al., Citation2022; Stein et al., Citation2022). The results of a post-hoc analysis showed that the average score for familiarity with virtual influencers was significantly lower in the virtual influencers condition compared to the human influencers condition. While the effect of familiarity with virtual and human influencers on perceived authenticity was statistically controlled in the PLS-SEM model, the post-hoc analysis suggests that the novelty effect (i.e., the lack of previous experience with virtual influencers) could have influenced participants in the virtual influencer condition to report a heightened perception of authenticity. Notably, most of the previous studies comparing consumer perceptions of virtual and human influencers have overlooked the potential impact of familiarity on the perception and evaluation of virtual influencers. Albeit limited, Arsenyan and Mirowska (Citation2021) did consider familiarity with virtual influencers as a factor that could influence consumer perceptions and found that humanized virtual influencers received fewer positive reactions from social media users. However, since this study relied on content analysis for analyzing consumer perceptions of virtual influencers, it is challenging to draw a quantitative conclusion on whether and how familiarity (or novelty effects) may influence consumer perceptions and evaluations of virtual influencers. Given this limitation, we recommend that future researchers explore whether familiarizing participants with virtual influencers might influence the results.

Additionally, we interpret our results with caution, suggesting that the congruency between the advertised product and the image of an entity might have influenced authenticity perception. This is in line with previous findings that congruency plays an essential role in enhancing authenticity perception (Eggers et al., Citation2013; North, Citation2015). Although further investigation is required, the congruence between the type of product (i.e., smartphone as machine) and the mechanical image of virtual influencers might have led participants to perceive virtual influencers as more authentic than they did human influencers. Supporting this, a previous qualitative study hints that product congruency with virtual influencers can positively influence the perceived authenticity of virtual influencers and purchase intentions (Lou et al., Citation2023). Similarly, another study has found that virtual influencers achieve greater congruence with technology products than with cosmetic products, thereby more effectively influencing consumers’ purchase intentions when endorsing tech products (Franke et al., Citation2022). Considering previous studies, we recommend that future studies control for various individual and external factors that could potentially influence user perception of virtual influencers and their effectiveness.

With respect to the role of the machine heuristic, our findings indicate that it significantly moderates the perceived authenticity of virtual influencers. Specifically, we revealed that virtual influencers’ machine identity led individuals with a stronger belief in machine heuristic to perceive these influencers as more authentic to a greater extent than those with a weaker belief in machine heuristic. This finding supports a previous study suggesting that individuals with a positive prior attitude toward machine agents would also judge the agent’s ability positively when machine cues are evident in them (Sundar, Citation2008). This provides empirical evidence to the previous proposition that being perceived as an authentic machine could reify the positive effects associated with the machine heuristic (Huang & Jung, Citation2022). Our finding extends the previous findings in human-computer interaction in which machine heuristic moderates the perceived security of web agents (Sundar & Kim, Citation2019) and the usefulness of voice assistants (Lee et al., Citation2022) to the realm of perceived authenticity of virtual influencers.

Our findings regarding the moderating role of machine heuristic contributes to the existing literature on the persuasiveness of virtual influencers. Prior studies have focused on how the direct attributes of virtual influencers (e.g., Kim & Baek, Citation2023; Kim et al., Citation2024), as well as the moderating effects of virtual influencer attributes (e.g., interactivity; Yang et al., Citation2023) and contextual characteristics (e.g., product category; Franke et al., Citation2022) influence user persuasion. By employing individuals’ machine heuristics as a moderating variable, our study highlights the importance of underlying psychological mechanisms through which individual characteristics influence the effectiveness of virtual influencers. Therefore, our findings extend the current scholarship, suggesting that the effectiveness of virtual influencers in influencer marketing may be significantly determined by individual differences in belief systems of technology, not solely by the influencers themselves.

Furthermore, our results extend the applicative scope of the MAIN model (Sundar, Citation2008) by demonstrating that even when machines closely mimic human appearance, their identity as machines influences user evaluations based on their pre-existing perceptions of machine capabilities. This finding suggests the critical impact of machine identity in shaping user evaluations, regardless of visual resemblance to humans. Expanding previous applications of the MAIN model, which focused on chatbots lacking physical human-like form (e.g., Lee et al., Citation2022; Sundar & Kim, Citation2019), our study applies these theoretical principles to human-like machines by integrating the role of “influencer” as a crucial aspect of agency. This expansion broadens the earlier applications of the model, highlighting the significant role of machine identity in the evaluation of human-computer interaction.

Consistent with previous research examining the relationship between authenticity and trust (Liu et al., Citation2022), our results demonstrate a significant positive association between the perceived authenticity of influencers and consumer trust in them. This association indicates that individuals who perceive influencers as authentic tend to place greater trust in the sincerity of the influencers’ product recommendations, and this trust is linked to decreased uncertainty in online shopping. This supports the prior argument that perceived authenticity may facilitate cognitive outcomes such as uncertainty reduction (Lee, Citation2020; Xu et al., Citation2021). Furthermore, these results corroborate previous studies suggesting consumers develop trust in influencers whom they perceive as having a sincere motive behind their product recommendations (Boerman et al., Citation2017; Sung & Kim, Citation2010). Our findings add the context of virtual influencers to previous insights, suggesting that transparent disclosure of commercial intention should not be treated as a risk in virtual influencer marketing but seen as an opportunity to build trustworthy relationships with consumers (Audrezet et al., Citation2020).

We also observed a significant positive association between trust in influencers and the purchase intention of the products they endorse. This association aligns with previous studies that have demonstrated a causal relationship in which trust was found to significantly increase people’s purchase intention in online advertising (Kim & Kim, Citation2021; Li & Peng, Citation2021; Lou & Yuan, Citation2019; Santiago et al., Citation2020). Our findings contribute to the existing literature by identifying a similar pattern of association, highlighting how trust may be associated with purchase decisions. Importantly, our finding adds depth to prior research, which has suggested that trust could encourage social media users to overcome their fear of failure in online shopping and, in turn, take purchasing actions (McKnight et al., Citation2002). This is particularly relevant in the context of social media commerce (e.g., Alkhalifah, Citation2021; Dutta & Bhat, Citation2016; Rashid et al., Citation2022)

Nonetheless, it should be noted that there have been mixed findings regarding the impact of disclosing virtual influencers’ identities on user perceptions. Our findings indicate that virtual influencers can positively influence consumers’ perceptions of authenticity upon transparent disclosure of their virtual origin. Conversely, Lim and Lee (Citation2023) found that such disclosure can negatively impact parasocial relationships and subsequently diminish the perceived credibility of a virtual influencer. Although both studies explore different psychological mechanisms (i.e., authenticity and parasocial relationship), such contradictory findings suggest that transparent disclosure of virtual origins may lead to different outcomes depending on the context. Thus, it is important for future studies to provide a comprehensive understanding of how revealing virtual influencers’ origin could influence consumer perceptions and evaluations.

Furthermore, the applicability of our results should be carefully considered in contexts where virtual influencers’ identities are not transparently disclosed. Guided by the strategies of popular virtual influencers who transparently disclose their virtual origins, such as @lilmiquela and @rozy.gram, our study focused on scenarios where virtual or robotic identities of virtual influencers are openly recognized as such by social media users. However, our results might differ if such disclosure is lacking. This is because the nondisclosure of virtual identities could negate the positive moderating effect of the machine heuristic, failing to enhance users’ perceptions of the authenticity of virtual influencers. Supporting this notion, a recent study found that virtual influencers may not necessarily be more effective than humans in terms of likability when their virtual origin is not explicitly disclosed (Böhndel et al., Citation2023). This suggests that disclosure of virtual origin could play a crucial role in how they are perceived by audiences.

5.1. Implications of results

The current study offers several theoretical implications. Building on the concept of machine heuristic (Sundar, Citation2008), we found that the individuals’ machine heuristics could moderate the perceived authenticity of virtual influencers. This finding provides a theoretical understanding of the recent adoption of virtual influencers as brand and product endorsers. This finding not only extends previous findings to the realm of perceived authenticity but also provides a theoretical framework that allows for interdisciplinary understanding of the role of virtual influencers on consumer perceptions and behaviors. Specifically, this research took a novel interdisciplinary approach by integrating theories from marketing (e.g., authenticity management framework; Audrezet et al., Citation2020) and human-computer interaction (e.g., the MAIN model; Sundar, Citation2008). We believe that this interdisciplinary approach can significantly contribute to existing scholarship in explaining how virtual influencers could persuade consumers in the context of influencer marketing.

This study also has practical implications that can provide insights into the development of influencer marketing strategies employing virtual influencers. The results of this study can guide brands planning to partner with virtual influencers for marketing purposes. Our results show that, even though the effects of the machine heuristic on the perceived authenticity of virtual influencers vary by individuals as the machine heuristic is an intrinsic belief, virtual influencers could be perceived as more authentic than human influencers regardless of people’s belief in the machine heuristic. Therefore, brands and marketing agencies that are considering influencer marketing may partner with virtual influencers for product or service advertising to prevent potential risks that can occur when using human influencers (e.g., scandals or ill rumors that damage brand image) and to increase the persuasiveness of marketing.

5.2. Limitations and future directions

The limitations of this study open pathways for future studies. First, although we investigated participants’ perceptions of authenticity toward virtual and human influencers using the authenticity management framework (Audrezet et al., Citation2020), it remains to be further studied whether participants attribute their perceptions of authenticity to the source or the message. Lee (Citation2020) proposed that source authenticity and message authenticity are distinct constructs influencing perceptions in mediated communication. Another study suggested that both the source and the message play important roles in the advertising process of virtual influencers (Byun & Ahn, Citation2023). Therefore, future research should delineate whether perceptions of authenticity are tied to the influencer (i.e., source) or to the content of their Instagram posts (i.e., message). If results indicate that people attribute their perceptions more to messages than to influencers, examining whether this message attribution is tied to transparency could offer deeper insights into the effects of communicating commercial purposes.

Another limitation is the lack of diversity in the product category used for the experiment, and the fact that product involvement was not measured and controlled. Although we deliberately chose a gender-neutral product (i.e., smartphone) for our study, the results may differ when other product categories are used. For instance, the effects of virtual influencers on consumer perceptions and behaviors may differ when virtual influencers are used for promoting services or products that manifest the human identity (e.g., art painting, vocal lessons, or donation) compared to when they are used for promoting services or products that manifest the machine identity (e.g., computer programming course). Therefore, we suggest that future researchers take into account the moderating role of product type or category (i.e., perceived congruency between virtual influencers and the category of the advertising product; see Franke et al., Citation2022) when examining the effects of virtual influencers on consumer perceptions and behaviors.

Regarding methodology, it merits attention from future researchers that the items used to test the moderating role of machine heuristic in this study measure diverse aspects of people’s beliefs in machines (e.g., security, privacy, objectiveness, unbiasedness). Although this measure has been validated in various contexts, including the perceived security of web agents (Sundar & Kim, Citation2019) and the usefulness of voice assistants (Lee et al., Citation2022), the fact that the measure lacks a focus on unbiasedness and objectiveness suggests the possibility that it might have introduced noise into the findings related to the moderating role of machine heuristic. Therefore, future studies may consider developing a more sensitive measure that captures diverse sub-constructs under the concept of machine heuristic to ensure a more nuanced test of the moderating role of machine heuristics and to ascertain the validity of our study findings.

Additionally, in future studies investigating the moderating role of machine heuristics, we suggest a careful approach regarding the timing of the measurement of the variable. Following the approach of Sundar and Kim (Citation2019), we measured participants’ prior beliefs in the machine heuristic after they were exposed to the experimental stimuli. Our questionnaire focused on their general beliefs about the machine heuristic, not their specific perceptions of the virtual influencers. However, measuring this after exposure to the stimuli might have subtly influenced their responses, complicating the interpretation of the machine heuristic’s role. To clarify the moderating role of machine heuristics, future studies may consider measuring the variable before exposing participants to experimental stimuli.

While measuring previous experience with virtual influencers allowed us to control participants’ familiarity with virtual influencers to some extent, we failed to control for the novelty effect that could be engendered by unfamiliarity with virtual influencers. Therefore, future researchers may consider familiarizing participants with virtual influencers before exposing them to the main stimuli to rule out the novelty effect. For example, exposing participants to detailed background information about the persona of virtual influencers (e.g., personalities or hobbies) could be some of the ways to lift participants’ unfamiliarity with virtual influencers. Screening out the participants who are not familiar with influencers via pretest would help control the novelty effect.

Furthermore, the findings of our study may require validation using samples representative of the general population. This is necessary because the participants in our study were recruited from a university participant pool, primarily consisting of students. While Boals et al. (Citation2020) demonstrated that using student samples may not significantly bias study results compared to employing other samples, there are also studies suggesting the potential risk of using student samples due to their slightly more homogeneous nature compared to nonstudent samples (Hooghe et al., Citation2010; Peterson, Citation2001). Nonetheless, a previous study provides potential evidence that virtual influencers may remain persuasive across various age groups. For example, consumers with an average age of 37.7 years showed a positive response to virtual influencers regarding purchase intentions (Ferraro et al., Citation2024). This aligns with the results of an online survey indicating that social media users aged 35 to 44 years are the most likely age group to trust virtual influencers compared to other age groups (The Influencer Marketing Factory, Citation2023). However, the effectiveness of virtual influencers among those older than 44 years remains unexplored in existing literature. Future research may consider including a broader range of ages to determine whether virtual influencers can maintain their effectiveness across a more diverse population. Expanding the age range would ensure the generalizability of the findings of our study. Additionally, future researchers may want to consider diversifying the samples to improve the robustness of study results and to carry out a detailed analysis of subgroups.

In a related vein, it merits further investigation whether dispositional traits of consumers will intervene in the process of evaluating and accepting virtual influencers. Notably, personality traits of users, particularly related to social behavior, have been found to influence feelings, evaluations, and actual behaviors in interactions with virtual characters (von der Pütten et al., Citation2010). This finding suggests that the openness or sociability of consumers may impact the perceived authenticity and acceptance of virtual influencers. Future researchers should ascertain whether the personality of consumers, in combination with the belief in machine heuristics, may moderate the perceived authenticity and trust in virtual influencers.

Finally, considering the diverse representation of virtual influencers (see Huang & Jung, Citation2022, p. 5), tailoring the degree of virtual influencers’ machine identity either via visual cues (i.e., physical appearance) or textual cues (e.g., introductory words) could lead to different marketing results. For example, we cautiously predict that virtual influencers manifesting a stronger machine identity, compared to those with a low level of machine identity, might be more persuasive for consumers who have a high belief in the machine heuristic. Therefore, we suggest future studies investigate the effects of each virtual influencer’s diverse machine cues on consumers’ perceptions of authenticity.

6. Conclusion

In conclusion, drawing on the authenticity management framework (Audrezet et al., Citation2020) and the concept of machine heuristic (Sundar, Citation2008), the current study investigated the authenticity of social media influencers and determined that virtual influencers can be perceived as more authentic than human influencers. Moreover, our results bolster existing findings on the serial positive association between perceived authenticity, trust in influencers, and purchase intention for the advertised product. The findings of this study carry theoretical implications regarding how the machine heuristic can act as a gating mechanism in perceiving the identities of virtual influencers as more authentic. Additionally, our results offer practical insights for brands and marketing agencies looking to shape the identities of virtual influencers for influencer marketing.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

We are willing to share data and study materials with other researchers. The data and materials that were used in this study are openly available in open science framework (OSF) at https://osf.io/nd6zs/?view_only=0c08d598052d4537b166ce99446a157a

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Heejae Lee

Heejae Lee is a PhD Candidate at the S.I. Newhouse School of Public Communications at Syracuse University. His research focuses on understanding how the affordances of media technologies and individual information processing influence user perceptions.

Mincheol Shin

Mincheol Shin is an Assistant Professor of New Media Design at Tilburg University. His research focuses on the psychological effects of emerging media technologies on human cognition, information processing, and behaviors.

Jeongwon Yang

Jeongwon Yang received her PhD from Syracuse University. Her research interests primarily lie in what triggers persuasion and what roles emerging media play in facilitating the persuasion process. Her specializations include crisis communication, CSR, and online mis/disinformation.

T. Makana Chock

T. Makana Chock is the David J. Levidow Endowed Professor at the S.I. Newhouse School of Public Communications at Syracuse University. She studies how people process and respond to persuasive messages in mass media, social media, and extended reality (virtual, augmented, and mixed reality) contexts.

References

- Alkhalifah, A. (2021). Exploring trust formation and antecedents in social commerce. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 789863. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.789863

- Andersson, V., Sobek, T. (2020). Virtual avatars, virtual influencers & authenticity: A qualitative study from a consumer perspective. University of Gothenburg School of Business, Economics and Law. https://gupea.ub.gu.se/bitstream/2077/64928/1/gupea_2077_64928_1.pdf

- Arsenyan, J., & Mirowska, A. (2021). Almost human? A comparative case study on the social media presence of virtual influencers. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 155, 102694. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs.2021.102694

- Audrezet, A., De Kerviler, G., & Moulard, J. G. (2020). Authenticity under threat: When social media influencers need to go beyond self-presentation. Journal of Business Research, 117, 557–569. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.07.008

- Audrezet, A., & Koles, B. (2023). Virtual influencer as a brand avatar in interactive marketing. In The Palgrave handbook of interactive marketing (pp. 353–376). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-14961-0_16

- Bagozzi, R. P., & Yi, Y. (1988). On the evaluation of structural equation models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 16(1), 74–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02723327

- Barari, M. (2023). Unveiling the dark side of influencer marketing: How social media influencers (human vs virtual) diminish followers’ well-being. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 41(8), 1162–1177. https://doi.org/10.1108/MIP-05-2023-0191

- Benzeval, M., Green, M. J., & Macintyre, S. (2013). Does perceived physical attractiveness in adolescence predict better socioeconomic position in adulthood? Evidence from 20 years of follow up in a population cohort study. PloS One, 8(5), e63975. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0063975

- Boals, A., Contractor, A. A., & Blumenthal, H. (2020). The utility of college student samples in research on trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder: A critical review. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 73, 102235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102235

- Boerman, S. C., Willemsen, L. M., & Van Der Aa, E. P. (2017). This post is sponsored”: Effects of sponsorship disclosure on persuasion knowledge and electronic word of mouth in the context of Facebook. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 38, 82–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intmar.2016.12.002

- Böhndel, M., Jastorff, M., & Rudeloff, C. (2023). AI-driven influencer marketing: Comparing the effects of virtual and human influencers on consumer perceptions. SSRN Electronic Journal, 2(2), 165–174. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4404372

- Byun, K. J., & Ahn, S. J. (2023). A systematic review of virtual Influencers: Similarities and differences between human and virtual influencers in interactive advertising. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 23(4), 293–306. https://doi.org/10.1080/15252019.2023.2236102

- Cassidy, S., & Eachus, P. (2002). Developing the computer user self-efficacy (CUSE) scale: Investigating the relationship between computer self-efficacy, gender and experience with computers. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 26(2), 133–153. https://doi.org/10.2190/JGJR-0KVL-HRF7-GCNV

- Cenfetelli, R. T., Benbasat, I., & Al-Natour, S. (2008). Addressing the what and how of online services: Positioning supporting-services functionality and service quality for business-to-consumer success. Information Systems Research, 19(2), 161–181. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.1070.0163

- Choudhry, A., Han, J., Xu, X., & Huang, Y. (2022). “I felt a little crazy following a ‘doll’.” Investigating real influence of virtual influencers on their followers. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 6(GROUP), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1145/3492862

- Cohen, J. (2013). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203771587

- Conti, M., Gathani, J., & Tricomi, P. P. (2022). Virtual influencers in online social media. IEEE Communications Magazine, 60(8), 86–91. https://doi.org/10.1109/MCOM.001.2100786

- Cusumano, K. (2019, May 20). Calvin Klein issued an apology for that Bella Hadid-Lil Miquela video. W Magazine. https://www.wmagazine.com/story/calvin-klein-apology-bella-hadid-lil-miquela-queerbaiting.

- Dencheva, V. (2023a, June 29). Share of consumers who follow at least one virtual influencer in the United States as of March 2022, by age group. Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1304080/consumers-follow-virtual-influencers-age-us/

- Dencheva, V. (2023b, June 29). Share of consumers who bought a product or service promoted by a virtual influencer in the United States as of March 2022, by age group. Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1304092/consumers-bought-product-promoted-virtual-influencers-age-group-us/

- Deng, F., & Jiang, X. (2023). Effects of human versus virtual human influencers on the appearance anxiety of social media users. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 71, 103233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2022.103233

- Djafarova, E., & Rushworth, C. (2017). Exploring the credibility of online celebrities’ Instagram profiles in influencing the purchase decisions of young female users. Computers in Human Behavior, 68, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.11.009

- Dutta, N., & Bhat, A. (2016). Exploring the effect of store characteristics and interpersonal trust on purchase intention in the context of online social media marketing. Journal of Internet Commerce, 15(3), 239–273. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332861.2016.1191053

- Eggers, F., O’Dwyer, M., Kraus, S., Vallaster, C., & Güldenberg, S. (2013). The impact of brand authenticity on brand trust and SME growth: A CEO perspective. Journal of World Business, 48(3), 340–348. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2012.07.018

- Evans, N. J., Phua, J., Lim, J., & Jun, H. (2017). Disclosing Instagram influencer advertising: The effects of disclosure language on advertising recognition, attitudes, and behavioral Intent. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 17(2), 138–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/15252019.2017.1366885

- Ferraro, C., Sands, S., Zubcevic-Basic, N., & Campbell, C. (2024). Diversity in the digital age: How consumers respond to diverse virtual influencers. International Journal of Advertising, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2023.2300927

- Franke, C., Groeppel-Klein, A., & Müller, K. (2022). Consumers’ responses to virtual influencers as advertising endorsers: Novel and effective or uncanny and deceiving? Journal of Advertising, 52(4), 523–539. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2022.2154721

- Go, E., & Sundar, S. S. (2019). Humanizing chatbots: The effects of visual, identity and conversational cues on humanness perceptions. Computers in Human Behavior, 97, 304–316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.01.020

- Goodhue, D. L., Lewis, W., & Thompson, R. (2012). Does PLS have advantages for small sample size or non-normal data? MIS Quarterly, 36(3), 981–1001. https://doi.org/10.2307/41703490

- Guo, J., Li, Y., Xu, Y., & Zeng, K. (2021). How live streaming features impact consumers’ purchase intention in the context of cross-border e-commerce? A research based on SOR theory. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 767876. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.767876

- Hair, J. F., Jr, Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., Sarstedt, M., Danks, N. P., & Ray, S. (2021). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) using R: A workbook (p. 197). Springer Nature. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-80519-7

- Hair, J. F., Jr, Sarstedt, M., Hopkins, L., & Kuppelwieser, V. G. (2014). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): An emerging tool in business research. European Business Review, 26(2), 106–121. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-10-2013-0128

- Hair, J. F., Jr, Matthews, L. M., Matthews, R. L., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). PLS-SEM or CB-SEM: Updated guidelines on which method to use. International Journal of Multivariate Data Analysis, 1(2), 107–123. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJMDA.2017.10008574

- Henseler, J., & Fassott, G. (2010). Testing moderating effects in PLS path models: An illustration of available procedures. Handbook of partial least squares: Concepts, methods and applications., 713–735. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-32827-8_31

- Hofeditz, L., Nissen, A., Schütte, R., & Mirbabaie, M. (2022). Trust me, I’m an influencer! A comparison of perceived trust in human and virtual influencers. ECIS 2022 Research-in-Progress Papers. 27. https://aisel.aisnet.org/ecis2022_rip/27

- Hooghe, M., Stolle, D., Mahéo, V., & Vissers, S. (2010). Why can’t a student be more like an average person?: Sampling and attrition effects in social science field and laboratory experiments. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 628(1), 85–96. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716209351516

- Huang, J., & Jung, Y. (2022). Perceived authenticity of virtual characters makes the difference. Frontiers in Virtual Reality, 3. https://doi.org/10.3389/frvir.2022.1033709

- Ilicic, J., & Webster, C. M. (2016). Being true to oneself: Investigating celebrity brand authenticity. Psychology & Marketing, 33(6), 410–420. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20887

- Jian, J. Y., Bisantz, A. M., & Drury, C. G. (2000). Foundations for an empirically determined scale of trust in automated systems. International Journal of Cognitive Ergonomics, 4(1), 53–71. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327566IJCE0401_04

- Jin, S. V., Ryu, E., & Muqaddam, A. (2021). I trust what she’s #endorsing on Instagram: Moderating effects of parasocial interaction and social presence in fashion influencer marketing. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal, 25(4), 665–681. https://doi.org/10.1108/jfmm-04-2020-0059

- Kernis, M. H., & Goldman, B. M. (2006). A multicomponent conceptualization of authenticity: Theory and research. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 38, 283–357. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0065-2601(06)38006-9

- Kim, M., & Baek, T. H. (2023). Are virtual influencers friends or foes? Uncovering the perceived creepiness and authenticity of virtual influencers in social media marketing in the United States. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2023.2233125

- Kim, D. Y., & Kim, H. Y. (2021). Trust me, trust me not: A nuanced view of influencer marketing on social media. Journal of Business Research, 134, 223–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.05.024

- Kim, J., Kim, M., & Lee, S. M. (2024). Unlocking trust dynamics: An exploration of playfulness, expertise, and consumer behavior in virtual influencer marketing. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2023.2300018

- Kim, E. A., Kim, D., E, Z., & Shoenberger, H. (2023). The next hype in social media advertising: Examining virtual influencers’ brand endorsement effectiveness. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1089051. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1089051

- Kock, N. (2014). Advanced mediating effects tests, multi-group analyses, and measurement model assessments in PLS-based SEM. International Journal of e-Collaboration, 10(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.4018/ijec.2014010101

- Kock, N. (2018). WarpPLS user manual: Version 8.0. ScriptWarp Systems. https://scriptwarp.com/warppls/UserManual_v_7_0.pdf

- Koh, Y. J., & Sundar, S. S. (2010). Heuristic versus systematic processing of specialist versus generalist sources in online media. Human Communication Research, 36(2), 103–124. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.2010.01370.x

- Koles, B., Audrezet, A., Moulard, J. G., Ameen, N., & McKenna, B. (2024). The authentic virtual influencer: Authenticity manifestations in the metaverse. Journal of Business Research, 170, 114325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2023.114325

- Lee, E. J. (2020). Authenticity model of (mass-oriented) computer-mediated communication: Conceptual explorations and testable propositions. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 25(1), 60–73. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcmc/zmz025

- Lee, E. J. (2024). Minding the source: Toward an integrative theory of human–machine communication. Human Communication Research, 50(2), 184–193. https://doi.org/10.1093/hcr/hqad034

- Lee, K. M. (2004). Presence, explicated. Communication Theory, 14(1), 27–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2004.tb00302.x

- Lee, M. K. (2018). Understanding perception of algorithmic decisions: Fairness, trust, and emotion in response to algorithmic management. Big Data & Society, 5(1), 205395171875668. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951718756684

- Lee, S., Oh, J., & Moon, W. K. (2022). Adopting voice assistants in online shopping: Examining the role of social presence, performance risk, and machine heuristic. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, 39(14), 2978–2992. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2022.2089813

- Li, H., Lei, Y., Zhou, Q., & Yuan, H. (2023). Can you sense without being human? Comparing virtual and human influencers endorsement effectiveness. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 75, 103456. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2023.103456

- Li, Y., & Peng, Y. (2021). Influencer marketing: Purchase intention and its antecedents. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 39(7), 960–978. https://doi.org/10.1108/MIP-04-2021-0104

- Lim, R. E., & Lee, S. Y. (2023). “You are a virtual influencer!”: Understanding the impact of origin disclosure and emotional narratives on parasocial relationships and virtual influencer credibility. Computers in Human Behavior, 148, 107897. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2023.107897

- Liu, X., Xiang, G., & Zhang, L. (2021). Social support and social commerce purchase intention: The mediating role of social trust. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 49(7), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.10381

- Liu, X., Zhang, L., & Chen, Q. (2022). The effects of tourism e-commerce live streaming features on consumer purchase intention: The mediating roles of flow experience and trust. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 995129. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.995129

- Lou, C. (2022). Social media influencers and followers: Theorization of a trans-parasocial relation and explication of its implications for influencer advertising. Journal of Advertising, 51(1), 4–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2021.1880345

- Lou, C., Kiew, S. T. J., Chen, T., Lee, T. Y. M., Ong, J. E. C., & Phua, Z. (2023). Authentically fake? How consumers respond to the influence of virtual influencers. Journal of Advertising, 52(4), 540–557. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2022.2149641

- Lou, C., & Yuan, S. (2019). Influencer marketing: How message value and credibility affect consumer trust of branded content on social media. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 19(1), 58–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/15252019.2018.1533501

- Lu, B., Fan, W., & Zhou, M. (2016). Social presence, trust, and social commerce purchase intention: An empirical research. Computers in Human Behavior, 56, 225–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.11.057

- Maqbool, R., Sudong, Y., Manzoor, N., & Rashid, Y. (2017). The impact of emotional intelligence, project managers’ competencies, and transformational leadership on project success: An empirical perspective. Project Management Journal, 48(3), 58–75. https://doi.org/10.1177/875697281704800304

- McKnight, D. H., Choudhury, V., & Kacmar, C. (2002). Developing and validating trust measures for e-commerce: An integrative typology. Information Systems Research, 13(3), 334–359. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.13.3.334.81

- Mirowska, A., & Arsenyan, J. (2023). Sweet escape: The role of empathy in social media engagement with human versus virtual influencers. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 174, 103008. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs.2023.103008