ABSTRACT

This study addresses the growing interest in upcycled foods as a solution to food loss by focusing on designing more appealing package labels in Japan. Through an online survey, we collected data on consumer attitudes and perceptions toward upcycled foods. We applied factor analysis to identify key factors and cluster analysis to segment consumers into distinct profiles. Using these insights, we conducted a choice-based conjoint analysis to extract the package design attributes most valued by consumers. Our results highlight key factors influencing purchase intentions, including food safety, innovation, and eco-friendliness. We identified two main consumer profiles: sustainability-focused and quality/safety-conscious, and innovative and socially engaged. Food safety emerged as the most crucial factor affecting purchase willingness, followed by product image and environmental considerations. The study emphasizes the importance of transparent, sustainable, and visually appealing package design in influencing consumer decisions and building long-term loyalty toward upcycled foods in Japan.

Introduction

As the Earth experiences unprecedented climate changes, including rising temperatures and unpredictable weather patterns, these shifts trigger cascading effects across natural and social environments (Diffenbaugh & Burke, Citation2019; Doney et al., Citation2012; Lee et al., Citation2020). The food sector, heavily dependent on natural conditions for agricultural production, is particularly vulnerable (D. Dinesh et al., Citation2021; Hu et al., Citation2023). Historical weather patterns, once stable enough for ancient calendars, are now erratic, threatening the ability to meet the growing population’s needs sustainably.

In the context of environmental concerns in the food industry, the reduction of food loss and waste has been the most prioritized choice so far. Food waste represents a significant global challenge crucial to achieving sustainable development (Beretta & Hellweg, Citation2019). The occurrence of food loss and waste is brought about by the excess supply in many countries. Oversupplied foods throughout the supply chain often become leftovers that are thrown away, although much of them are still edible (Chalak et al., Citation2016; Redlingshöfer et al., Citation2020). Discussions around food waste have traditionally focused on reducing waste in sectors such as households, retail, and grocery stores. Many studies have discussed how to enhance behavior change among stakeholders to reduce food waste (Blanke, Citation2015; Christ & Burritt, Citation2017; Heng & House, Citation2022; Matzembacher et al., Citation2020). On farms, produce that is not standardized in size or shape is often discarded before reaching the market. In retail shops, products close to their due dates are often distributed to food banks. At home, people try to manage their refrigerator inventory or cook effectively to minimize waste (Brown et al., Citation2014; Cooper et al., Citation2023).

Addressing the food loss and waste issue requires a multidimensional approach. Upcycled food has emerged as a promising solution to reduce waste and repurpose materials into consumable products (Spratt et al., Citation2020; Thorsen et al., Citation2022). Rather than relying solely on the voluntary efforts of stakeholders, transforming waste into more profitable avenues like upcycling has garnered support from both industry participants and consumers (Aschemann-Witzel et al., Citation2023). Edible portions that were previously discarded on farms or during processing are now recognized as raw materials for new products, such as dried or fried fruits and vegetables. In some cases, these ingredients are selected for their novel functions – such as fortifying both processing and storage conditions or enhancing nutritional benefits – to create empowered food products (Bas-Bellver et al., Citation2023; Grasso et al., Citation2019; Lacivita et al., Citation2023; Moshtaghian et al., Citation2022).

As upcycled foods have gained market presence, they have also captured consumer attention by appealing to a sense of moral duty and the desire for environmental stewardship. This alignment with consumer values has been skillfully integrated into marketing strategies, enhancing the products’ eco-friendly image, nutritional appeal, and food safety (Grasso et al., Citation2023; Lu et al., Citation2024; Moshtaghian et al., Citation2022; Rondoni & Grasso, Citation2021). In particular, packaging plays a critical role in this strategy (Temple, Citation2020). For instance, the upcycled food logo helps illustrate the product’s environmentally conscious production process and contribution to sustainable development (Bhatt et al., Citation2021; Tiboni-Oschilewski et al., Citation2024). Although upcycled food certification is not yet widespread in Japan, there are instances of multiple companies promoting and selling products as upcycled food. For example, OISIX produces snacks using grape pomace, a byproduct of winemaking, and upcycled food utilizing stems and peels generated during vegetable processing. Asahi Breweries also utilizes bread crusts from bread processing to produce craft beer, contributing to the upcycled food movement. Internationally, the Upcycled Food Association (UFA) has started a certification system called “Upcycled Certified.” This certification can be obtained by undergoing an audit of ingredients and the supply chain. For consumers wary of new foods, clear images of the ingredients can alleviate fears by providing a familiar visual context (Lancelot Miltgen et al., Citation2016). Nutritional disclosure also might be effective (Herpen & Trijp, Citation2011).

Our research aims to design more appealing package labels for upcycled foods in Japan. We began by exploring consumer attitudes and perceptions toward upcycled foods, segmenting the consumers to identify target groups. Based on targeted groups’ preferential insights, we crafted package designs tailored to the preferences of these segments and assessed the factors most positively influencing their purchasing decisions. This study is divided into two parts: the first investigates consumer profiles of upcycled foods, and the second focuses on package label design.

Materials and methods

This study was conducted in two steps. The first step explored consumer attitudes and perceptions toward upcycled foods and segmented the consumers to identify target groups using factor analysis and cluster analysis. The second step suggested package designs tailored to the preferences of these segments and assessed the factors most positively influencing their purchasing decisions through choice-based conjoint analysis.

In the following section, we detail the comprehensive approach used for data collection and analysis. An online survey was conducted twice: first for factor analysis and cluster analysis, and second for choice-based conjoint analysis. The data from these surveys were further applied to statistical analysis accordingly. We applied factor analysis to identify key factors and used cluster analysis to segment consumers into distinct profiles. Using these insights, we then conducted a choice-based conjoint analysis to pinpoint the package design attributes most valued by consumers.

Data collection for factor analysis and cluster analysis

Based on previous studies reporting factors influencing willingness to purchase upcycled food products, including environmental consciousness and behavior, health orientation, and trend sensitivity, questions were designed (Ji et al., Citation2016; Katsuura, Citation2023; Matsubaguchi et al., Citation1997; Oda & Aizawa, Citation2008; Seo & Shigi, Citation2024). Additionally, we assumed that an individual’s personality influences their acceptance of new technologies and foods, such as ambition, need for approval, self-values, intellectual curiosity, and social relationships, and these factors were added (Appendix A).

Key topics and references of these questions is detailed below.

Interest in upcycled foods

Willingness to purchase was assessed using statements that asked about their purchase intentions under the necessary conditions they considered important. These conditions included a government certification system to approve upcycled foods to ensure their quality and safety, the taste of the upcycled food products, their price, and the quality control measures in place (Seo & Shigi, Citation2024).

Food security

Food security issues can influence the acceptance of novel foods. Recent environmental crises and population increases drive innovation in the food industry sector to cope with resource limitations and achieve sustainable development. Consequently, these social backgrounds could change consumers’ perceptions and behaviors regarding their food choices (Stevens & Ruperti, Citation2023). Upcycled foods have the potential to alleviate resource tensions, leading to an increased supply. Therefore, we designed statements related to perceptions of food price vulnerability, the global food supply, and Japan’s food self-sufficiency rate.

Perception and behavior against food loss

Awareness of social benefits often appears as one of the significant factors affecting the purchase intention of novel foods (Giacalone & Jaeger, Citation2023). Several studies have found that increased knowledge can enhance familiarity with novel foods and positively influence acceptance. Upcycled foods are made from food waste and loss generated during production. Consumers who acknowledge the benefits of upcycled foods recognize that they can contribute to reducing food loss and further mitigate economic and environmental burdens. Therefore, we chose statements to assess awareness of food loss, including perceptions of food loss and behaviors to reduce food loss (Katsuura, Citation2023).

Environmental consciousness and behavior

Environmental consciousness and behavior have been widely discussed in terms of their impact on food acceptance (Tobler et al., Citation2011). Recent environmental issues in society have drawn the attention of consumers, prompting them to care for and act in favor of the environment. Consistently, in the food sector, consumers tend to choose environmentally friendly products such as organic food and cultured meat, which can help mitigate environmental burdens (Vermeir et al., Citation2020). For upcycled foods made from food loss and waste, consumers could be driven to act for the environment by purchasing these products (Aschemann-Witzel et al., Citation2023). Therefore, we included statements related to environmental consciousness and behavior (Matsubaguchi et al., Citation1997; Oda & Aizawa, Citation2008).

Personality traits

Personality traits form the basis of individuals’ attitudes and behaviors. They impact every attitude and perception. When shopping and considering what to buy, personality traits can potentially affect product preferences (Ji et al., Citation2016; Lin et al., Citation2019; Spence, Citation2022). We hypothesized that innovativeness, conscientiousness, social outgoingness, self-improvement orientation, and health-consciousness would positively or negatively influence attitudes and perceptions toward new technologies and related foods. Consequently, we included statements addressing these aspects in our survey.

The questionnaire was pre-tested in an academic environment to confirm the understanding of the question content and was subsequently revised. Participants were recruited from a panel registered with the online survey company Marketing Applications, Inc. (https://surveroid.jp/company/). In the response process, participants were first provided with an explanation of the research objectives, content, and the possibility of presenting results. Only those who agreed proceeded to the response screen.

Subsequently, participants who agreed to participate were provided with a definition and explanation of upcycled food products, along with presenting prerequisite knowledge, before data collection. This survey was conducted in July 2023 and targeted 1,285 men and women residing in Japan, with a gender ratio of 637 males (49.6%) to 648 females (50.4%), reflecting Japan’s population distribution. Responses were solicited using a 7-point Likert scale (1. Strongly disagree ~ 7. Strongly agree).

Data collection for choice-based conjoint analysis

We conducted a pretest in an academic environment to verify the validity of the attributes and levels, and subsequently conducted the main survey. The main survey was conducted based on the results of a preliminary survey conducted in October 2023, targeting 368 men and women. The sample was selected in line with the population ratio of Japan by age, resulting in 279 valid responses. Additionally, data collection was conducted to ensure there were no sex disparities in the male-to-female ratio.

Factor analysis and cluster analysis

Cluster analysis was performed based on factor scores derived from factor analysis. Initially, the factor extraction method employed maximum likelihood estimation, and the factor axes were rotated using oblimin rotation. Subsequently, utilizing the factor scores obtained from factor analysis (with values weighted according to factor loadings for each factor), nonhierarchical cluster analysis was conducted using the k-means method. In this study, cluster analysis was utilized to classify the segment interested in upcycled food products. The purchase intention regarding upcycled food products was determined from response data to the statement, which asked, “I am willing to try buying upcycled foods.” (Appendix A). Both factor analysis and cluster analysis were performed using the statistical analysis software R.

Choice-based conjoint analysis

From the factor analysis and cluster analysis conducted in Study 1, we determined the primary factors that the potential target segments in Cluster 2, Cluster 3, and Cluster 4 prefer, which can then be incorporated into the package label. Using this information and considering the characteristics of individuals who hold favorable opinions about upcycled foods, we conducted a choice-based conjoint analysis to identify the attributes of package design that are considered important.

We devised six attributes for the purpose of selecting survey items. These attributes encompass “Package color,” “Presence of product image,” “Trendy perception,” “Environmental label presence,” “Food safety assurance label presence,” and “Upcycled foods label presence.” The respective levels for each attribute are outlined in . Color and product images were suggested to be closely related to consumers’ choices (Hallez et al., Citation2023; Wang et al., Citation2023). “Trendy perception” was derived from the factor “Socially outgoing,” “Environmental label” from the factor “Environmental act,” “Food safety assurance” from the factor “Upcycled food quality & safety-conscious,” and “Upcycled foods label” from the factor “Innovative.” The model upcycled food product is broccoli stem snack.

Table 1. Items and levels of choice-based conjoint analysis.

Results

Consumer preference and segmentation

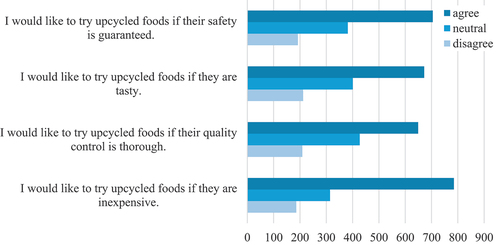

We investigated the relationship between taste, price, safety, and purchase intention () by analyzing the responses to “I would like to try upcycled foods if their safety is guaranteed,” “I would like to try upcycled foods if they are tasty,” “I would like to try upcycled foods if their quality control is thorough,” and “I would like to try upcycled foods if they are inexpensive.” Focusing on positive responses (scores 5, 6, 7; agree), we observed that considering the conditions of taste, price, and safety led to an increase in consumer purchase intention. Among these factors, taste had the most significant influence on purchase intention.

Based on the 7-point numerical scores obtained from a questionnaire assessing respondents’ perceptions of upcycled food products, factor analysis yielded seven distinct factors. Factor 1 encompasses items such as “I would like to try upcycled foods if they are inexpensive,” “I would like to try upcycled foods if their quality control is thorough,” “I would like to try upcycled foods if they are tasty,” “I am willing to try buying upcycled foods,” and “I would like to try upcycled foods if their safety is guaranteed,” all showing factor loadings of 0.6 or higher. These results suggest that Factor 1 represents a positive attitude toward purchasing upcycled food products, denoting “Interest in upcycled foods.”

In Factor 2, items such as “I want to try out new knowledge I’ve acquired,” “I want to try food products that promote new ingredients or effects,” “I feel stressed if I can’t talk about myself in conversations with friends,” “I think I’m someone who frequently updates social media.,” and “I read books and web articles from various genres” showed factor loadings of 0.6 or higher. This suggests that Factor 2 is driven by curiosity, denoting “Innovative.”

In Factor 3, items such as “I think a private sector certification system is necessary to ensure the quality and safety of upcycled food products” and “I think a government certification system is necessary to ensure the quality and safety of upcycled foods.” showed factor loadings of 0.6 or higher. Therefore, Factor 3 prioritizes the quality and safety of food products, denoting “Upcycled food quality & safety-conscious.”

Factor 4 includes items like “I think food prices have been sharply rising in recent years” and “I believe that global warming is having a serious impact on our lives,” both of which showed factor loadings of 0.6 or higher. This indicates that Factor 4 is concerned with environmental issues, denoting “Frugal-green.”

In Factor 5, items such as “I always strive to do the right thing,” “I consider myself to be strong in terms of justice,” and “I try to stick to decisions I’ve made” showed factor loadings of 0.5 or higher. Factor 5 is characterized by adherence to social norms, denoting “Conscientious.”

Factor 6 includes items like “I think I have many friends I frequently talk to,” “I believe I have many friends I can talk to about anything,” and “I believe I have a wide circle of friends,” all of which showed factor loadings of 0.6 or higher. This suggests that Factor 6 is associated with a wide social network, denoting “Socially outgoing.”

Factor 7 comprises items such as “I pay attention to the balance of my diet,” I avoid leaving leftovers when eating out,” and “I make efforts to save energy by reducing electricity usage and avoiding air conditioning,” all of which showed factor loadings of 0.3 or higher. This indicates that Factor 7 is related to “Environmental act.”

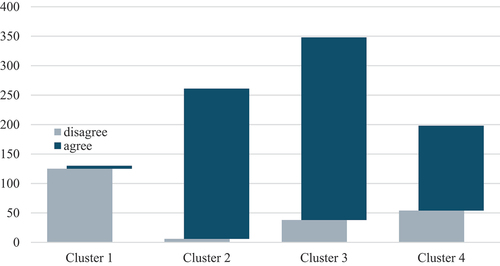

Based on the factor score of respondents, we clustered them into four clusters. Characteristics of each cluster was revealed (). Cluster 1 comprises 138 individuals, accounting for about 11% of the total sample. This cluster shows a lack of interest in upcycled food products (−1.724), quality associated with upcycled foods (−1.835), and frugal-green (−1.091). Cluster 2, with 277 individuals (approximately 22% of the total), exhibits strong curiosity toward innovation (1.122) and has a wide social network (1.151), although it shows lower interest in the quality of upcycled food products (0.856). Cluster 3, the largest cluster with 448 individuals (approximately 34% of the total), demonstrates frugal and high concern for environmental issues (0.568) and environmentally friendly act (0.537) but has a more limited social circle (−0.771). Cluster 4, consisting of 422 individuals (approximately 33% of the total), shows decreased environmentally friendly act (−0.492) and interest in upcycled food products (−0.418), along with a lower concern for the quality of upcycled food products (−0.399).

Table 2. Factor scores of clusters.

The composition of the consumer segments in this study exhibits diversity across Clusters 1 to 4, highlighting significantly distinct characteristics. Cluster 1 comprises individuals with minimal interest not only in upcycled food products but also in environmental issues, identified as “Passive.” Clusters 2 and 3 consist of individuals highly enthusiastic about purchasing upcycled food products, labeled as “Innovative-conscientious” and “Eco-frugal-introverted,” respectively. Their preferences seem strongly influenced by factors like curiosity, emphasis on quality, and environmental consciousness. Cluster 4, representing about one-third of the total sample, shows relatively limited interest in upcycled food products but exhibits diplomatic behavior and a favorable attitude toward sharing information, characterized as “Innovative-social.” Given the importance of this cluster in driving the expansion of the upcycled food product market, future endeavors may entail refining questions and factors to pinpoint crucial characteristics.

The results illustrating the purchase intentions of each cluster are presented in . The vertical axis represents the purchase intention for upcycled food products, ranging from 1 (Not interested at all in buying) to 7 (Very interested in buying), while the horizontal axis depicts the clusters (Cluster 1 to Cluster 4). The vertical width indicates the proportion of responses on the 7-point scale for each cluster, and the horizontal width shows the relative number of individuals in each cluster. Cluster 2 showed the highest purchase intention for upcycled food products, while individuals in Cluster 1 exhibited lower purchase intentions compared to other clusters. The order of purchase intentions is as follows: Cluster 2 > Cluster 3 > Cluster 4 > Cluster 1.

provides a breakdown of demographic characteristics across clusters. Analysis by sex shows that Clusters 1 and 4 have more males, while Clusters 2 and 3 have more females. Regarding age, Cluster 1 has a higher share of individuals in their 20s, whereas Clusters 2 and 3 have significantly more individuals aged 60 and above, with over 60% being 50 years old or more. Looking at occupations, Clusters 2 and 3 show a higher proportion of full-time homemakers. In terms of marital and parental status, Cluster 2 has a higher marriage rate and more individuals with children compared to other clusters.

Table 3. Socio-demographic characteristics of clusters by one-way ANOVA analysis.

Package label design attributes based on target segment preferences

The analysis revealed distinct patterns across clusters: Cluster 1 is predominantly young males showing less interest in upcycled food products, Cluster 2 shows a strong interest among females in upcycled food, Cluster 3 has a diverse age distribution with a focus on environmental concerns, and Cluster 4 consists mostly of married individuals with moderate interest in upcycled food and environmental awareness. ANOVA results indicated significant differences in sex (0.045), occupation (0.004), and parental status (0.025) among the clusters.

However, considering that this study aligned the survey with Japan’s age demographics, where respondents aged 60 and above represent around 42% of the total, it’s premature to conclude that the elderly are the primary target audience. Further analysis and consideration are warranted.

shows the characteristics of the survey participants for choice-based conjoint analysis. The table presents the socio-demographic characteristics of the sample participants in the study. The total number of participants is 279, comprising 143 males and 136 females. Regarding age distribution, there are 29 participants in their 20s, 37 in their 30s, 50 in their 40s, 43 in their 50s, and 120 participants over 60 years old. The occupation distribution includes 9 public servants, 8 managers/executive officers, 23 administrative company employees, 25 technical company employees, 32 other company employees, 21 self-employed individuals, 11 freelancers, 58 homemakers, 29 part-time/temporary workers, 7 students, and 56 participants categorized under “Other.” In terms of marital status, there are 111 single participants and 168 married participants. Additionally, there are 153 participants with children and 126 participants without children.

Table 4. Socio-demographic characteristics of samples.

The estimation results of the choice-based conjoint analysis on packaging of upcycled food are presented in below. In the choice-based conjoint analysis results of this study, only the attribute “Trendy feel” in the latter analysis was significant at the 10% level, while other attributes were significant at the 1% level. This indicates that there is relevance between the probability of selecting a product and all seven attributes. Focusing on the coefficients, the attributes “Product Image,” “Environmental Consideration,” and “Upcycled foods label” were positive. From this information, it can be inferred that including images of “Product Image” and “Upcycled foods label” or logo images such as “Environmental Consideration” and “Food Safety” increases the probability of selection. On the other hand, attributes like “Color” and “Trendy feel” were negative, suggesting that including “Trendy feel” or choosing a package with a dark label design reduces the probability of consumer selection.

Table 5. Results of conjoint analysis.

Discussion & conclusions

Tailoring package labels to consumer preferences

Several factors were identified as influential in shaping consumer purchase intentions for upcycled foods. These factors include interest in upcycled foods, an innovative mind-set, concern for upcycled food quality and safety, frugality, eco-friendly behavior, conscientiousness, and sociability. Consumers who strongly demonstrate these traits also exhibit the highest purchase intentions. This led to the emergence of two distinct consumer profiles; Cluster 2 and Cluster 3 in the cluster analysis. Cluster 3 shows a keen interest in upcycled foods along with concerns about their quality, safety, frugality, eco-friendliness, and conscientiousness. This profile comprises the largest segment of consumers. Cluster 2 is characterized by innovation and sociability.

Consumers in Cluster 3 are characterized by being frugal and conscientious, with a relatively strong inclination toward sustainability and environmental awareness, leading them to prefer upcycled products. They place a high priority on quality and safety, specifically focusing on the nutritional value and safety standards of the foods they consume. These consumers also demonstrate a frugal mind-set and appreciate the resourcefulness of repurposed food items (Piracci et al., Citation2023; Song et al., Citation2023). They actively seek out products and practices that minimize waste and reduce environmental impact, showcasing an eco-conscious mind-set (Gatersleben et al., Citation2019; Stancu et al., Citation2020). Additionally, conscientiousness is a key trait among these consumers, reflecting their responsible and ethical approach to consumption (S. Dinesh & Mitra, Citation2023; Song et al., Citation2023). Overall, the psychological profile of consumers in Cluster 3 emphasizes their commitment to sustainability, health consciousness, resourcefulness, and environmental stewardship.

On the other hand, consumers in Cluster 2 are characterized by their openness to new ideas, concepts, and experiences, which translates into a strong interest in innovative food products such as upcycled foods. They are curious and adventurous, often seeking novel and unique food options that resonate with their forward-thinking mind-set (Li et al., Citation2023). Furthermore, these consumers are socially outgoing, enjoying interactions with others and engaging in social activities. They value social connections and are influenced by social trends and peer opinions, making them receptive to new food trends and sustainability initiatives (Rahimah et al., Citation2024). Their outgoing nature extends to their willingness to share their experiences and recommendations, contributing to the awareness and adoption of upcycled foods within their social circles.

These preferences were revealed as significant attributes of package labels. Product image, environmental, safety, and upcycled foods labels significantly affect willingness to purchase. This suggests that consumers should prioritize safety, environmental contribution, and the effective use of food resources. In recent years, consumer behavior has evolved significantly, with an increasing focus on sustainability and ethical consumption. This shift has prompted consumers to pay closer attention to the packaging of products, seeking information beyond just the product itself (Shikalgar et al., Citation2024). The inclusion of product images on package labels provides consumers with a visual representation of the product, aiding in their decision-making process (Roberto et al., Citation2012; Temple, Citation2020).

Environmental labels signal to consumers that the product is produced with consideration for environmental impact, appealing to those with eco-conscious values (Kabaja et al., Citation2023). Safety labels play a crucial role in building consumer trust and confidence in the product (Walaszczyk et al., Citation2023). In today’s food landscape, where concerns about food safety and quality are prevalent, a clear and visible safety label can reassure consumers and encourage them to make a purchase. Similarly, upcycled foods labels highlight the sustainability aspect of the product, appealing to consumers interested in reducing waste and supporting environmentally friendly practices (Bhatt et al., Citation2021). In essence, these factors collectively emphasize the importance of transparency, sustainability, and appeal in package label design. By addressing these key attributes, brands can effectively communicate their values and offerings to consumers, ultimately driving purchase decisions and fostering long-term consumer loyalty.

Theoretical implications

This study contributes significantly to the theoretical understanding of consumer behavior toward upcycled foods by segmenting Japanese consumers into distinct clusters based on their attitudes and preferences. This segmentation aligns with previous research highlighting the complexity of sustainable consumption and the impact of various factors, such as environmental concerns and social values, on consumer choices (Saari et al., Citation2021).

The findings underscore the importance of several key dimensions in consumer behavior. Firstly, the interest in upcycled foods is crucial as it highlights the potential for reducing food waste and promoting environmental conservation. Understanding consumer purchase intentions and developing targeted marketing strategies are vital for expanding the market for these products (Lu et al., Citation2024; Seo & Shigi, Citation2024). Secondly, food security plays a significant role in influencing consumer acceptance of new food technologies. By raising awareness about food security, marketers can build consumer trust and reduce barriers to market entry (Albertsen et al., Citation2020). Thirdly, the perception and behavior against food loss are essential in driving the acceptance of upcycled foods. Consumers who recognize the benefits of reducing food waste are more likely to support and purchase upcycled food products (Aschemann-Witzel et al., Citation2023).

Furthermore, environmental consciousness and behavior have a profound impact on food acceptance, with environmentally conscious consumers being more inclined to choose products that mitigate environmental burdens (Coderoni & Perito, Citation2020). Lastly, personality traits such as innovativeness, conscientiousness, social outgoingness, self-improvement orientation, and health-consciousness influence consumer attitudes and perceptions toward new technologies and foods (Spence, Citation2022).

Practical implications

On a practical level, the study offers actionable insights for marketers targeting the Japanese market. Optimizing packaging designs and label attributes, particularly emphasizing visual elements such as food safety information, product imagery, and environmental sustainability considerations, can significantly influence Japanese consumer perceptions and choices. This is crucial given the identified preferences of Japanese consumers in Clusters 2 and 3, who highly value attributes such as innovation, food safety, and environmental consciousness. Aligning packaging designs with these attributes can enhance the appeal of upcycled food products and increase their acceptance and adoption among Japanese consumer segments.

Importantly, the analysis of package label attributes highlights the paramount importance of food safety in the Japanese consumer context. Among factors like product images, environmental labels, and upcycled foods labels, food safety emerged as the most critical consideration influencing consumer perceptions and purchase intentions. This finding resonates with Japan’s consumer prioritization of safety and quality in consumed products, reflecting a fundamental aspect of consumer behavior where trust and reliability are paramount. Clear and transparent food safety information in package labeling is essential to instill confidence among Japanese consumers, addressing their concerns regarding the quality and integrity of upcycled food products. Marketers targeting the Japanese market should emphasize food safety in package labeling strategies to meet consumer expectations, build trust, and enhance brand credibility.

Additionally, the study underscores the importance of effective sustainability communication in consumer engagement within the Japanese context. Brands that communicate their environmental actions, solutions to food security challenges, and quality assurances effectively can build trust and credibility among environmentally conscious Japanese consumers. This communication strategy can lead to increased market penetration and broader acceptance of upcycled food products in Japan. Leveraging these practical implications specific to the Japanese market can contribute positively to sustainable consumption practices, drive growth, and expand the market for upcycled food products in Japan.

Limitations and future study

One notable challenge encountered in this study pertains to the potential bias in data resulting from the use of online surveys. This bias can manifest in two critical areas that warrant careful consideration. Firstly, there may be a bias in the sociodemographic characteristics of the survey respondents, influenced by factors such as their geographical location, cultural background, socioeconomic status, and the overall environment they reside in. These variables can collectively contribute to a skewed sample, which in turn may impact the generalizability and representativeness of the study’s findings. To mitigate this challenge, it is imperative to explore and employ diversified survey methods. Incorporating alternative approaches like mail surveys, personal communication, or in-person focus groups could offer a more comprehensive segmentation analysis. These methods can provide deeper insights into consumer preferences and behaviors related to upcycled food products, thus enhancing the accuracy and reliability of the data collected for package label design considerations.

Secondly, the limitation of questionnaire items primarily focused on topics within the food industry, environmental perception, and personal traits may potentially restrict the breadth of understanding regarding consumers’ attitudes and perceptions toward upcycled foods. While these areas are undoubtedly crucial, the inclusion of questionnaire items related to sensory aspects could further enrich the study’s insights. Exploring sensory attributes such as taste, texture, aroma, and overall sensory experience associated with upcycled food products can offer a more nuanced understanding of consumer preferences and decision-making processes. This expanded scope of inquiry would contribute to the study’s overall comprehensiveness and depth of analysis.

Despite the developmental stage and relatively low public awareness of upcycled food products, their market presence is steadily expanding. This growth trajectory presents a significant opportunity to address pressing global food sustainability issues and promote more sustainable consumption patterns. Consequently, the upcycled food product sector is anticipated to continue its upward trajectory, driven by increasing consumer awareness and demand for environmentally friendly and innovative food options. To effectively stimulate consumer purchasing intentions and capitalize on this growth potential, it is crucial to focus on strategic sales strategies. This includes developing packaging designs that not only meet regulatory requirements and provide essential information but also resonate with consumer preferences and values. By aligning packaging designs with consumer demand and preferences, businesses can enhance their competitive edge, foster brand loyalty, and contribute to the sustainable growth of the upcycled food product sector.

Acknowledgments

This study was approved by Research Ethics Committee of Tokyo University of Science for Medical and Biological Research Involving Human Subjects (#23057). Informed consent was waived by the ethics committee.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Albertsen, L., Wiedmann, K. P., & Schmidt, S. (2020). The impact of innovation-related perception on consumer acceptance of food innovations–development of an integrated framework of the consumer acceptance process. Food Quality and Preference, 84, 103958. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2020.103958

- Aschemann-Witzel, J., Asioli, D., Banovic, M., Perito, M. A., Peschel, A. O., & Stancu, V. (2023). Defining upcycled food: The dual role of upcycling in reducing food loss and waste. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 132, 132–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2023.01.001

- Bas-Bellver, C., Barrera, C., Betoret, N., & Seguí, L. (2023). Physicochemical, technological and functional properties of upcycled vegetable waste ingredients as affected by processing and storage. Plant Foods for Human Nutrition, 78(4), 710–719. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11130-023-01114-1

- Beretta, C., & Hellweg, S. (2019). Potential environmental benefits from food waste prevention in the food service sector. Resources, Conservation & Recycling, 147, 169–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2019.03.023

- Bhatt, S., Ye, H., Deutsch, J., Jeong, H., Zhang, J., & Suri, R. (2021). Food waste and upcycled foods: Can a logo increase acceptance of upcycled foods? Journal of Food Products Marketing, 27(4), 188–203. https://doi.org/10.1080/10454446.2021.1955798

- Blanke, M. (2015). Challenges of reducing fresh produce waste in Europe—from farm to fork. Agriculture, 5(3), 389–399. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture5030389

- Brown, T., Hipps, N. A., Easteal, S., Parry, A., & Evans, J. A. (2014). Reducing domestic food waste by lowering home refrigerator temperatures. International Journal of Refrigeration, 40, 246–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrefrig.2013.11.021

- Chalak, A., Abou-Daher, C., Chaaban, J., & Abiad, M. G. (2016). The global economic and regulatory determinants of household food waste generation: A cross-country analysis. Waste Management, 48, 418–422. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2015.11.040

- Christ, K. L., & Burritt, R. (2017). Material flow cost accounting for food waste in the restaurant industry. British Food Journal, 119(3), 600–612. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-07-2016-0318

- Coderoni, S., & Perito, M. A. (2020). Sustainable consumption in the circular economy. An analysis of consumers’ purchase intentions for waste-to-value food. Journal of Cleaner Production, 252, 119870. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.119870

- Cooper, A., Lion, R., Rodriguez-Sierra, O. E., Jeffrey, P., Thomson, D., Peters, K., Christopher, L., Zhu, M. J. H., Wistrand, L., Werf, P., & van Herpen, E. (2023). Use-up day and flexible recipes: Reducing household food waste by helping families prepare food they already have. Resources, Conservation & Recycling, 194, 106986. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2023.106986

- Diffenbaugh, N. S., & Burke, M. (2019). Global warming has increased global economic inequality. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(20), 9808–9813. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1816020116

- Dinesh, D., Hegger, D. L., Klerkx, L., Vervoort, J., Campbell, B. M., & Driessen, P. P. (2021). Enacting theories of change for food systems transformation under climate change. Global Food Security, 31, 100583. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2021.100583

- Dinesh, S., & Mitra, S. (2023). Consumers’ adoption of electric vehicles for sustainability: Exploring the role of personality traits. Foresight and STI Governance, 17(2), 69–80. https://doi.org/10.17323/2500-2597.2023.2.69.80

- Doney, S. C., Ruckelshaus, M., Emmett Duffy, J., Barry, J. P., Chan, F., English, C. A., Galindo, H. M., Grebmeier, J. M., Hollowed, A. B., Knowlton, N., Polovina, J., Rabalais, N. N., Sydeman, W. J., & Talley, L. D. (2012). Climate change impacts on marine ecosystems. Annual Review of Marine Science, 4(1), 11–37. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-marine-041911-111611

- Gatersleben, B., Murtagh, N., Cherry, M., & Watkins, M. (2019). Moral, wasteful, frugal, or thrifty? Identifying consumer identities to understand and manage pro-environmental behavior. Environment & Behavior, 51(1), 24–49. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916517733782

- Giacalone, D., & Jaeger, S. R. (2023). Consumer acceptance of novel sustainable food technologies: A multi-country survey. Journal of Cleaner Production, 408, 137119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.137119

- Grasso, S., Fu, R., Goodman-Smith, F., Lalor, F., & Crofton, E. (2023). Consumer attitudes to upcycled foods in US and China. Journal of Cleaner Production, 388, 135919. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.135919

- Grasso, S., Omoarukhe, E., Wen, X., Papoutsis, K., & Methven, L. (2019). The use of upcycled defatted sunflower seed flour as a functional ingredient in biscuits. Foods, 8(8), 305. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods8080305

- Hallez, L., Vansteenbeeck, H., Boen, F., & Smits, T. (2023). Persuasive packaging? The impact of packaging color and claims on young consumers’ perceptions of product healthiness, sustainability and tastiness. Appetite, 182, 106433. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2022.106433

- Heng, Y., & House, L. (2022). Consumers’ perceptions and behavior toward food waste across countries. International Food and Agribusiness Management Review, 25(2), 197–210. https://doi.org/10.22434/IFAMR2020.0198

- Hu, C., Sha, L., Huang, C., Luo, W., Li, B., Huang, H., Xu, C., & Zhang, K. (2023). Phase change materials in food: Phase change temperature, environmental friendliness, and systematization. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 140, 104167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2023.104167

- Ji, M., Wong, I. A., Eves, A., & Scarles, C. (2016). Food-related personality traits and the moderating role of novelty-seeking in food satisfaction and travel outcomes. Tourism Management, 57, 387–396. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2016.06.003

- Kabaja, B., Wojnarowska, M., Ćwiklicki, M., Buffagni, S. C., & Varese, E. (2023). Does environmental labelling still matter? Generation Z’s purchasing decisions. Sustainability, 15(18), 13751. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151813751

- Katsuura, M. (2023). Survey on food loss and its application to childcare practice. Annual Bulletin of the Institute of Interdisciplinary Research, Shikoku University, 3, 99–107. https://shikoku-u.repo.nii.ac.jp/records/663

- Lacivita, V., Lordi, A., Kalaydzhiev, H., Chalova, V. I., Del Nobile, M. A., & Conte, A. (2023). Sunflower meal ethanol solute powder as an upcycled value-product to prolong food shelf life. Food Bioscience, 54, 102869. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fbio.2023.102869

- Lancelot Miltgen, C., Pantin-Sohier, G., Grohmann, B. (2016). Communicating sensory attributes and innovation through food product labeling. Journal of Food Products Marketing, 22(2), 219–239. https://doi.org/10.1080/10454446.2014.1000435

- Lee, J. H., Kim, J. Y., Kim, J. I., Park, Y. J., & Park, C. M. (2020). Plant thermomorphogenic adaptation to global warming. Journal of Plant Biology, 63(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12374-020-09232-y

- Li, M., Bai, X., Xing, S., & Wang, X. (2023). How the smart product attributes influence consumer adoption intention. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1090200. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1090200

- Lin, W., Ortega, D. L., Caputo, V., & Lusk, J. L. (2019). Personality traits and consumer acceptance of controversial food technology: A cross-country investigation of genetically modified animal products. Food Quality and Preference, 76, 10–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2019.03.007

- Lu, P., Parrella, J. A., Xu, Z., & Kogut, A. (2024). A scoping review of the literature examining consumer acceptance of upcycled foods. Food Quality and Preference, 114, 105098. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2023.105098

- Matsubaguchi, R., Amono, H., & Ito, S. (1997). A relationship and environmentally between responsible consumer behavior. Journal of Home Economics of Japan, 48, 775–781. https://doi.org/10.11428/jhej1987.48.775

- Matzembacher, D. E., Brancoli, P., Maia, L. M., & Eriksson, M. (2020). Consumer’s food waste in different restaurants configuration: A comparison between different levels of incentive and interaction. Waste Management, 114, 263–273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2020.07.014

- Moshtaghian, H., Parchami, M., Rousta, K., & Lennartsson, P. R. (2022). Application of oyster mushroom cultivation residue as an upcycled ingredient for developing bread. Applied Sciences, 12(21), 11067. https://doi.org/10.3390/app122111067

- Oda, J., & Aizawa, Y. (2008). Questionnaire survey concerning the environmental consideration consciousness in consumer behavior. Journal of Kibi International University School of Policy Management, 4, 11–24. https://kiui.repo.nii.ac.jp/records/704

- Piracci, G., Casini, L., Contini, C., Stancu, C. M., & Lähteenmäki, L. (2023). Identifying key attributes in sustainable food choices: An analysis using the food values framework. Journal of Cleaner Production, 416, 137924. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.137924

- Rahimah, A., Do, B. R., Le, A. N. H., & Cheng, J. M. S. (2024). Commitment to and connection with green brands: Perspectives of consumer social responsibility and terror management theory. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 33(3), 314–329. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-11-2022-4214

- Redlingshöfer, B., Barles, S., & Weisz, H. (2020). Are waste hierarchies effective in reducing environmental impacts from food waste? A systematic review for OECD countries. Resources, Conservation & Recycling, 156, 104723. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2020.104723

- Roberto, C. A., Bragg, M. A., Livingston, K. A., Harris, J. L., Thompson, J. M., Seamans, M. J., & Brownell, K. D. (2012). Choosing front-of-package food labelling nutritional criteria: How smart were ‘smart choices’? Public Health Nutrition, 15(2), 262–267. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980011000826

- Rondoni, A., & Grasso, S. (2021). Consumers behaviour towards carbon footprint labels on food: A review of the literature and discussion of industry implications. Journal of Cleaner Production, 301, 127031. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.127031

- Saari, U. A., Damberg, S., Frömbling, L., & Ringle, C. M. (2021). Sustainable consumption behavior of Europeans: The influence of environmental knowledge and risk perception on environmental concern and behavioral intention. Ecological Economics, 189, 107155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2021.107155

- Seo, Y., & Shigi, R. (2024). Understanding consumer acceptance of 3D-printed food in Japan. Journal of Cleaner Production, 454, 142225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2024.142225

- Shikalgar, A., Menon, P., & Mahajan, V. C. (2024). Towards customer-centric sustainability: How mindful advertising influences mindful consumption behaviour. Journal of Indian Business Research, 16(1), 119–133. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIBR-06-2023-0207

- Song, C. S., Lee, J. Y., Mutha, R., & Kim, M. (2023). Frugal or sustainable? The interplay of consumers’ personality traits and self-regulated minds in recycling behavior. Sustainability, 15(24), 16821. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152416821

- Spence, C. (2022). What is the link between personality and food behavior? Current Research in Food Science, 5, 19–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crfs.2021.12.001

- Spratt, O., Suri, R., & Deutsch, J. (2020). Defining Upcycled Food Products. Journal of Culinary Science & Technology, 19(6), 485–496. https://doi.org/10.1080/15428052.2020.1790074

- Stancu, C. M., Grønhøj, A., & Lähteenmäki, L. (2020). Meanings and motives for consumers’ sustainable actions in the food and clothing domains. Sustainability, 12(24), 10400. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410400

- Stevens, H., & Ruperti, Y. (2023). Smart food: Novel foods, food security, and the smart nation in Singapore. Food, Culture, and Society, 27(3), 754–774. https://doi.org/10.1080/15528014.2022.2163455

- Temple, N. J. (2020). Front-of-package food labels: A narrative review. Appetite, 144, 104485. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2019.104485

- Thorsen, M., Skeaff, S., Goodman-Smith, F., Thong, B., Bremer, P., & Mirosa, M. (2022). Upcycled foods: A nudge toward nutrition. Frontiers in Nutrition, 9, 1071829. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2022.1071829

- Tiboni-Oschilewski, O., Abarca, M., Santa Rosa Pierre, F., Rosi, A., Biasini, B., Menozzi, D., & Scazzina, F. (2024). Strengths and weaknesses of food eco-labeling: A review. Frontiers in Nutrition, 11, 1381135. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2024.1381135

- Tobler, C., Visschers, V. H., & Siegrist, M. (2011). Eating green. Consumers’ willingness to adopt ecological food consumption behaviors. Appetite, 57(3), 674–682. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2011.08.010

- Van Herpen, E., & Van Trijp, H. C. (2011). Front-of-pack nutrition labels. Their effect on attention and choices when consumers have varying goals and time constraints. Appetite, 57(1), 148–160.

- Vermeir, I., Weijters, B., De Houwer, J., Geuens, M., Slabbinck, H., Spruyt, A., Kerckhove, A. V., Van Lippevelde, W. V., Steur, H., & Verbeke, W. (2020). Environmentally sustainable food consumption: A review and research agenda from a goal-directed perspective. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1603. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01603

- Walaszczyk, A., Kowalska, A., & Staniec, I. (2023). A survey on willingness-to-pay for food quality and safety cues on packaging of meat: A case of Poland. Decision, 50(2), 233–249. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40622-023-00352-1

- Wang, H., Ab Gani, M. A. A., & Liu, C. (2023). Impact of snack food packaging design characteristics on consumer purchase decisions. SAGE Open, 13(2), 21582440231167109. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440231167109

Appendix A

Questionnaire

Section 1

Socio-demographic

Sex

Male_____ Female_____

Age

20s__ 30s__ 40s__ 50s__ over 60s

Occupation

Public servant

Manager/Executive Officer

Company Employee (Administrative)

Company Employee (Technical)

Company Employee (Other)

Self-employed

Freelancer

Homemaker

Part-time/Temporary Worker

Student

Other

Marital

Single____ Married_____

Children

With children_____ Without children_____

Section 2

Please select one option among the following scale for questions #1 to #46:

1 (strongly disagree) – 2 (disagree) – 3 (somewhat disagree) – 4 (neutral) – 5 (somewhat agree) – 6 (agree) – 7 (strongly agree)

Food security

1. I think food prices have been sharply rising in recent years.

2. I think food doesn’t reach where it’s needed in the world.

3. I think Japan’s food self-sufficiency rate needs to be increased.

Innovative

4. I want to try out new knowledge I’ve acquired.

5. I’m intrigued by devices that use the latest technology.

6. I want to try food products that promote new ingredients or effects.

7. I quickly research things that catch my interest in books or web articles.

Interest in upcycled foods

8. I am willing to try buying upcycled foods.

9. I think a government certification system is necessary to ensure the quality and safety of upcycled foods.

10. I think a private sector certification system is necessary to ensure the quality and safety of upcycled food products

11. I would like to try upcycled foods if they are inexpensive.

12. I would like to try upcycled foods if their safety is guaranteed.

13. I would like to try upcycled foods if their quality control is thorough.

14. I would like to try upcycled foods if they are tasty.

Environmental consciousness

15. I believe that global warming is having a serious impact on our lives.

16. I make an effort to separate my trash.

17. I believe that the extinction of species is deeply connected to human life.

18. I think stopping global warming is more important than economic growth.

19. I believe food loss has a negative impact on the environment.

20. I make efforts to save energy by reducing electricity usage and avoiding air conditioning.

21. I use eco bags when shopping.

Perception and behavior against food loss

22. When food products utilizing food loss are completed, I think they can contribute to improving food security.

23. I think food loss should be reduced.

24. I think food loss leads to additional costs.

25. I am aware of the process that leads to food loss.

26. I know what food loss is.

27. I manage the food in my refrigerator properly.

28. I know what non-edible parts of food are.

29. I avoid leaving leftovers when eating out.

30. Even if the expiration date has passed, I’ll eat it as long as it looks and smells normal.

Conscientiousness

31. I always strive to do the right thing.

32. I consider myself to be strong in terms of justice.

33. I try to stick to decisions I’ve made.

Social outgoing

34. I often find myself talking too much about myself in conversations with friends.

35. I believe I have many friends I can talk to about anything.

36. I feel stressed if I can’t talk about myself in conversations with friends.

37. I think I’m someone who frequently updates social media.

38. I think I have many friends I frequently talk to.

39. I believe I have a wide circle of friends.

Self-improvement

40. I believe I am striving for a high social status.

41. I often feel like I have too many things I want to do and not enough time.

42. I think taking lessons is necessary for my personal growth.

43. I think reading books for self-improvement is beneficial.

44. I read books and web articles from various genres.

Health-consciousness

45. I pay attention to the balance of my diet.

46. I make it a point to exercise regularly.

47. I make a point to undergo regular health checkups.