Creating culture is no small feat. Leave it to a whole lot of rebellious preteens and teenagers to do it in postwar Britain, against a backdrop of rationing, conscription and the reconstruction of blitzed cities. Billy Bragg, iconic British punk folk singer, activist and writer, has told the whole tale in a compelling exposition of the roots – and the world-changing results – of the postwar, youth-led musical craze known as “skiffle.” Bragg is no stranger to the social changes wrought in England by the Second World War. In an interview on the life and times of George Orwell, Bragg pointed to a stunning example of the humane victory of ordinary people's unity during wartime. The National Health Service was founded in the bombed cities of Britain.

That was an accidental, incremental creation during the Blitz, as they started having free hospitals for rescue teams in the Blitz, then for children, then for women. And then eventually they ran a free service and everyone understood that it was possible to do that without destroying the fabric of society. It's just a shame they had to go through the Blitz to realize that. (BBC Citation2017)

It is the musical legacy of the war that concerns Bragg's new book. Mainly undertaken by teenage boys, the birth of skiffle paved the way for the rock ‘n’ roll genre and the rise of the British rock royalty, including David Bowie, the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, the Who, Pink Floyd, Led Zeppelin and the Animals, all of whom began as youth in skiffle bands. Joe Cocker started his musical career playing skiffle at the tender age of 12 (Sweeting Citation2014). Besides the big stars, skiffle engaged the imagination and energies of tens of thousands of youth, most of whom never made records, but who did organize hundreds of local and regional music competitions and Lonnie Donegan fan clubs. “That generation deserves to have their story told. It's a revolutionary story because of what they went on to do” (Timberg Citation2017). Skiffle, which Bragg sometimes summarizes as “English schoolboys playing Lead Belly's repertoire,” rose to the teenage national consciousness, and the top of the music charts, in the U.K. for a short 18 months or so between 1956 and 1958. The story of skiffle's roots, and its contribution to the revolutionary music that followed, make for compelling reading for anyone interested in the inner workings of cultural change.

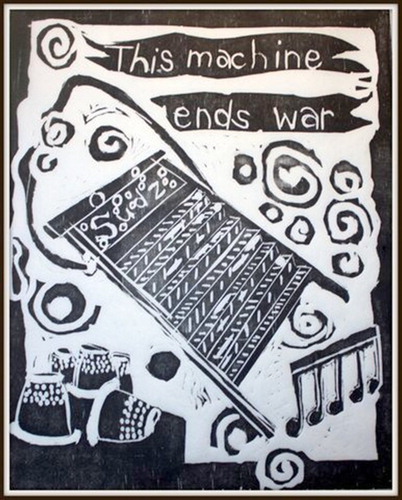

A generation who had known almost nothing but war and rationing from childhood was unloosed from these strictures in the postwar years. The economic boom gave employment to many working class boys and girls. In 1954, when rationing finally ended, the youth had things to spend their disposable income on, and they chose records, cappuccinos, full skirts and cheap guitars. Espresso bars provided one important space for youth culture, and the espresso machine, patented in Italy in 1946, was thought to have produced a “strange social ferment,” the BBC noted in 1955 (Bragg Citation2017a, 161). There were not very many places for young people to congregate. But the espresso bars offered “a new social space that was open to people of all classes and ages. … For the price of a few cups of coffee, teenagers could sit and socialise all night long” (Citation2017a, 161–162). Espresso bars attracted youth of all ethnicities, with music often being sung by patrons or house bands, and “‘black and white couples dancing to jazz.’ … It was from this milieu of teenage cross-pollination that skiffle emerged as a sub-genre in its own right” (Citation2017a, 162). Postwar mass migration from the West Indies to the U.K. had brought the sounds of calypso and the possibility of new kinds of youth friendships and anti-racist unity (Citation2017a, 126–127). Such were the generational realities that shaped skiffle as a working class, cross-cultural creation, that synthesized New Orleans jazz and British folk music, and was played with thimbles on washboards (see ), on home-made tea chest basses and the Czechoslovakian guitars also favored by calypso bands.

A sample of one of the stories behind skiffle's emergence illustrates the radical pathway the young skifflers walked. In the late 1940s, Bill and Ken Colyer and friends formed the Crane River Jazz Band and played for teenage audiences. During intervals in the performances, Bill would sometimes play his favorite jazz pieces from his extensive record collection and discuss the music with the listeners.

‘We’re talking about kids – fifteen, sixteen, seventeen,’ Bill said of the crowd who gathered round to hear his recitals. … Bill suggested to his brother that, instead of playing records during the interval, the two of them could perform some American roots music on guitar and washboard, and if Julian Davies wanted to join in on stand-up bass, they’d have a great little breakdown group. … Though no one was calling it skiffle back then, Bill and Ken Colyer, through their urge to spread the gospel of the roots of jazz, had planted the seeds of a movement that would one day inspire a generation of British kids to pick up the guitar and play rock ‘n’ roll (Citation2017a, 30–31).

Dedicated to their craft, the Crane River Jazz Band played weekly gigs in the early 1950s, gained an eager following and caught the attention of the adults of the jazz establishment (the Jazz Appreciation Society, Melody Maker), who recognized the youth's enthusiasm, but labeled their music “crude” and “primordial.” “But the Cranes didn't care; they were insurrectionists, a revolutionary cadre come to save jazz from commercialism by taking it back to basics” (Citation2017a, 31).

In 1953, asked by a BBC announcer what type of music they were playing, Bill Colyer plucked the term ‘skiffle’ out of history to describe the music of their breakdown group, differentiating it from jazz and blues. “In an instant, Colyer had changed the meaning of the word, from arcane black American slang for a rent party to a contemporary British term describing guitar-led, roots-based music” (Citation2017a, 95). The skiffle kids “created a do-it-yourself music that crossed over racial and social barriers. … British pop music, for so long a jazz-based confection aimed at an adult market, was transformed into the guitar-led music for teens that would go on to conquer the world in the 1960s” (Citation2017a, xv).

On the question of cultural appropriation, the book celebrates the common heritage of musical forms. “Before commerce made ownership the key transactional interest of creativity, songs passed through culture by word of mouth and bore the fingerprints of everyone who ever sang them” (Citation2017a, 17). Bragg has since further argued:

I think that one of the problems with the debate about appropriation is it runs contrary really to the spirit of music. Music belongs to everyone or no one. … It kind of lives by being sung. … [Ewan] MacColl and Peggy [Seeger] tried this in the folk clubs in London in the ‘60s and said you can only sing songs that come from your own culture. And it was like … a form of Stalinism. You know, who needs – folk music doesn't need police. … It needs – it needs to go wherever it goes. (Bragg Citation2017b)

Bragg describes skiffle as “an indigenous sub-genre of roots music that was only played by young white guys from Britain” (165). While it was mainly young white men who were picking up instruments, people across races, especially young women were also “absolutely crucial to the whole thing” (Citation2017b). In a talk to the Library of Congress, Bragg (Citation2017b) posited,

I think it was young women's determination to create their own social space that really made it possible for the skiffle kids to get out of the church hall, and the scout hut, and the school gymnasium and go to somewhere where there was actually, sort of, teen interaction. Because the young women who suddenly inherited this incredible spending power, they needed their own social space. … So they colonized the brand new cappuccino bars that had started opening up across the UK in the mid-50s.

Skiffle music challenged the narrow, staid culture of the BBC – and adults in general. It was moreover a youthful, working-class break from the elite imperial culture of Britain. Even as the British army conscripted blue collar youth to fight against anti-colonial insurrectionists (like the Beatles’ original drummer, Norman Chapman, called up to fight the Mau Mau in Kenya in 1960 (Citation2017a, 387)), even younger teenagers were boldly studying, adopting and adapting the musical expressions of African American musicians. Not only was there an anti-racist theme running through the skiffle frontier, but the players adopted an attitude of anti-commercialism and egalitarianism. “‘A good New Orleans band has no stars,’ Ken Colyer told the Cranes. ‘It's the ensemble that is important’” (Citation2017a, 34). Postwar youth cut their teeth on skiffle before founding British rock ‘n’ roll, and in that way also contributed to the 1960s worldwide youth uprisings.

While questions of ecology are not exactly tackled in Roots, Radicals and Rockers, this can hardly be held against Mr. Bragg. His work's creative message shines through and is made even more relevant to ecological questions when seen in light of Bragg's oeuvre. During a live radio broadcast in 2013, for instance, improvising lyrics in Waiting for the Great Leap Forward, Bragg identified our times as “the twilight of the capitalist system” (Citation2013). Ever more does it appear that history's minute-hand is moving past twilight and into proper night time. As we keep waiting, our task is to prepare for the morning of a new kind of world, one that, as Arundhati Roy says, “has already been born” (Citation2003), and is set to wake from its babe's slumber. In 2017, Bragg's new songs addressed climate change head on (see http://billybragg.co.uk/bridgesnotwalls/ for lyric video of King Tide and the Sunny Day Flood). In interviews and during spoken segments of his concerts, he regularly speaks of climate change as “the biggest challenge that we face as humanity,” and that “as places get hotter, people will find it more difficult to make a living on the land and will be on the move. This is not something we can just build a wall; it's something we have to deal with” (Soundcloud Citation2017). It is in the question of how humanity deals with these crises that ecological concerns might best be illuminated by Bragg's new book.

So how did skiffle kids change the world? By foregrounding and practicing cross-cultural harmony “democratis(ing) popular culture” and making the future (Citation2017a, 392). Skifflers hand-carved the cultural institution of British rock ‘n’ roll. It was imagination, creativity and the sociable experiences of unity, solidarity, music and dancing that made possible the establishment – by kids, mind you – of something entirely new and revolutionary, from the combination of the best attributes and values of culturally and ethnically diverse musical forms. What lesson can we take from the skiffle kids to inform the challenges humanity faces today? Against a twenty-first century backdrop of climate chaos, rising fascism and nuclear threats, a whole lot of rebellious creation of new cultural forms is urgently required. Bragg's book provides a window into the power of creativity in the face of the division and domination established within official culture. Shouldn't this inspire us to pool and use our full range of imaginative powers and DIY capacities to re-invent not only a revolutionary musical form, but a whole new revolutionary society, one that is in harmony with itself and with the planet?

References

- BBC. 2017. “George Orwell.” The English Fix, Series 2, BBC Radio 4, September 11.

- Bragg, Billy. 2013. Live on KEXP, Austin, TX. Recorded March 14, 2013, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y-R73tNgEUg.

- Bragg, Billy. 2017a. Roots, Radicals and Rockers: How Skiffle Changed the World. London: Faber & Faber, 431.

- Bragg, Billy. 2017b. Roots, Radicals and Rockers. Washington, DC: Library of Congress Webcasts. July 21. https://www.loc.gov/today/cyberlc/feature_wdesc.php?rec=7944

- Roy, Arundhati. 2003. War Talk. Boston: South End Press.

- Soundcloud. 2017. “Billy Bragg & the fight against cynicism: in conversation with Michael Sokol.” 93.9 The River, October 14. https://soundcloud.com/939theriver-1/billy-bragg-the-fight-against-cynicism-in-conversation-with-michael-sokol.

- Sweeting, Adam. 2014. “Joe Cocker obituary.” The Guardian, December 22. https://www.theguardian.com/music/2014/dec/22/joe-cocker.

- Timberg, Scott. 2017. “How skiffle changed the world: a conversation with Billy Bragg, Scott Timberg interviews Billy Bragg.” Los Angeles Review of Books, October 8. https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/how-skiffle-changed-the-world-a-conversation-with-billy-bragg/#!