ABSTRACT

In the midst of an ongoing civil war, the people of North and East Syria have been building a society based on the ideas of direct-democratic and decentralized self-administration. Differently put, they have embraced the principles and ideas of democratic confederalism, which is the political ideology developed by Partiya Karkerên Kurdistanê (PPK, Kurdistan Workers’ Party) founder Abdullah Öcalan. The purpose of this essay is to give an overview of the governance system of NES for the purpose of demonstrating the democratic confederalist approach to addressing patriarchal violence. In addition, the ambition is to assess the traditional notion of law and punishment as a solution for dealing with patriarchal violence, or, as Kropotkin would describe it, “a remedy for evil.” In addition to the more traditional and hierarchical court systems of contemporary societies, there are reconciliation committees in North and East Syria which seek to eliminate patriarchal violence through means of rehabilitation rather than punishment. In conclusion, NES serves as a fairly successful example of how patriarchal violence can be addressed within a justice system that is based on principles of restorative and transformative justice.

Introduction

You have to act as if it were possible to radically transform the world. And you have to do it all the time. – Angela Davis, Talk at Southern Illinois University Carbondale

… a remedy for evil. Instead of themselves altering what is bad, people begin by demanding a law to alter it.

The purpose of this essay is twofold. In writing this text, my primary ambition is to give an overview of the governance system of NES in order to demonstrate the democratic confederalist approach to addressing patriarchal violence.Footnote2 In Western liberal societies, justice has often been equated with punishment (or retributive justice), especially so in cases of patriarchal violence (see McGlynn Citation2011 for a discussion on retributive and restorative justice in relation to rape crimes). Thus, I will investigate how the justice system of NES is organized and how cases of patriarchal violence are addressed and handled within (and outside) the system. The primary materials used for this essay are books and articles written by researchers, activists and journalists who have visited NES. In addition, excerpts from interviews which have been conducted and provided by the Rojava Information Center, for the purpose of this essay, are included. My second aim is to assess the traditional notion of law and punishment as a solution for dealing with patriarchal violence, or, as Kropotkin would describe it, as “a remedy for evil.” This will be done by presenting a reconceptualized idea of law and justice inspired by anarchist legal theory and based on principles of restorative and transformative justice.

Reconceptualizing Law and Justice

The confused mass of rules of conduct called Law, which has been bequeathed to us by slavery, serfdom, feudalism, and royalty, has taken the place of those stone monsters before whom human victims used to be immolated, and whom slavish savages dared not even touch lest they should be slain by the thunderbolts of heaven. –Pëtr Kropotkin Citation1886.

Democratic confederalism is based on grassroots participation. Its decision-making processes lie with the communities. Higher levels only serve the coordination and implementation of the will of the communities that send their delegates to the general assemblies. For one year they are both mouthpiece and executive institutions. However, the basic power of decision rests with the local grass-roots institutions. (Öcalan Citation2017, 47)

Law as commonly understood in contemporary Western societies, that is, enacted and executed by the authority and power of the state, cannot operate within a consensus-oriented direct democratic self-administrative non-state society. For law to properly function within a democratic confederalist society, an anarchist conception of law is necessary. This conception of law is provided by Pëtr Kropotkin, and to a large extent implemented by the democratic confederation that is NES.

The word anarchism is derived from the Greek word anarchos which means “no ruler.” Anarchists have been challenging the traditional Western idea of the state and its concept of law as imposed by a sovereign. Therefore, anarchist rejections of law are tied to rejections of the state, but not necessarily of law understood as order in society (Davies Citation2017a, 29):

Such was law; and it has maintained its two-fold character to this day. Its origin is the desire of the ruling class to give permanence to customs imposed by themselves for their own advantage. Its character is the skilful commingling of customs useful to society, customs which have no need of law to insure respect, with other customs useful only to rulers, injurious to the mass of the people, and maintained only by the fear of punishment. (Kropotkin Citation1886, 10–11).

Peoples without political organization, and therefore less depraved than ourselves, have perfectly understood that the man who is called “criminal” is simply unfortunate; that the remedy is not to flog him, to chain him up, or to kill him on the scaffold or in prison, but to relieve him by the most brotherly care, by treatment based on equality, by the usages of life amongst honest men. (Kropotkin Citation1886, 23)

A Consensus-oriented Justice System

Thousands of volumes have been written to record the acts of governments; the most trifling amelioration due to law has been recorded; its good effects have been exaggerated, its bad effects passed by in silence. But where is the book recording what has been achieved by the free co-operation of well-inspired men? – Pëtr Kropotkin, Anarchist Communism: Its Basis and Principles, 1927.

Basic Structure

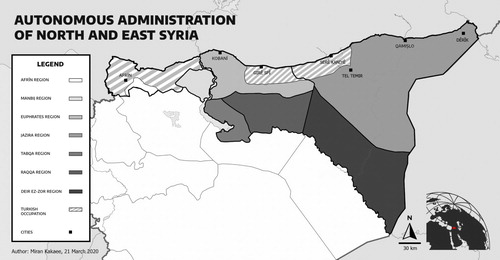

The justice system of NES is structured in different levels. On the communal, neighborhood and district levels there are Peace and Consensus Committees, which constitute the basis of the justice system. The Peace and Consensus Committees not only resolve cases of criminality, but also social injustice, and the goal of the committees is to reach social peace through consensus, rather than retribution. Instead of incarceration and using other means of punishment, the accused is therefore made to understand the injustice and damage that the person has caused, through a process of dialogue and reconciliation amongst the parties (Knapp, Flach, and Aybogan Citation2016, 180). According to Xelid Ehme, member of the reconciliation committee in the Dêrîk region (see ), instead of “imposing a given measure, they propose a solution. When the solution is accepted, it is normally written and signed by all parties to the conflict.” In some cases, compensation is paid to the affected party, and in other cases religion plays an important role in seeking forgiveness. If consensus is not reached on the communal level, the matter is taken to the Peace and Consensus Committee on the neighborhood level. The structure and proceedings of the committee are essentially the same as on the communal level and settling the case through consensus is once again the primary objective. The Peace and Consensus Committees are not authorized to imprison people (Duman Citation2017, 88).

If it is not possible to solve local matters within the Peace and Consensus Committees, the cases are referred to the judiciary, or the courts, which is the next level. In addition, according to Ehme, more severe cases are directly referred to the judiciary:

When any violation of human rights take place, the case is redirected to the Justice Court. For example killings or grand larceny … cases that need an individual to be protected, along with deeper interrogation and investigation.

Historically arbitration and mediation were the preferred alternatives. They expressed an ideology of communitarian justice without formal law, an equitable process based on reciprocal access and trust among community members. They flourished as indigenous forms of self-government.

Because the formal law alone is not always right, it cannot cover everything … We engage with our society, and we feel that our existence as a justice committee has value. Not only in Serê Kaniyê, but outside Serê Kaniyê, we go into society and work with them. We are not content with the law alone.Footnote4

Parallel Women’s Justice System

Separate women’s communes are located within the cities and villages of NES. These communes organize women in each area by doing educational work, reading books and organizing group discussions. Additionally, they make house visits and talk to women so that they are included in the commune system:

We want women to become self-reliant. We go to the villages too and talk to women there. Many of them don’t dare speak to us, but afterward, secretly, they make their way to us. (Knapp, Flach, and Aybogan Citation2016, 87; see also Allsopp and van Wilgenburg Citation2019, 155–156)

The aim of the committees is to resolve cases of patriarchal violence by means of consensus and reconciliation rather than sending the case to a court, where there is a risk that the court will sentence the accused to prison. This preference for reconciliation is consistent with the restorative and transformative principles of justice, since even though imprisonment might temporarily protect the women who have suffered patriarchal violence, in order to eliminate patriarchy a societal transformation is needed, and in order to transform society, the individuals constituting society must be transformed as well. Therefore, other sanctions that are used against perpetrators are: “work in a cooperative or public service; exclusion from the commune; social isolation … boycott if the convicted person has a shop; temporary relocation to another neighborhood; and exclusion from some public rights” (Knapp, Flach, and Aybogan Citation2016, 182).

In accordance with the ambition of transforming society and eliminating patriarchy, education is one the main sanctions used against persons convicted of patriarchal violence. Thus, a person might have to undergo education, which can last until the trainers are convinced that the person has changed (Knapp, Flach, and Aybogan Citation2016, 182; see also Sly Citation2019). Influenced by Kropotkin’s view on prisons, incarceration in NES is no longer conceived of as a means of punishing the convicted person. Rather, the prisons have been reconceived as educational institutions, with the ambition of transforming them into rehabilitation centers once the means are available (Sly Citation2019; Knapp, Flach, and Aybogan Citation2016, 182–183). Additionally, several women from the women organizations in NES have expressed a wish to “move away from prison and other non-restorative forms of punishment” (Magpie Citation2016).

Before concluding this section, something will be said about the effect of the new justice system in NES, although it is difficult to generalize on the matter. The number of prisoners is reported to be on a low level. In mid 2012, when the new justice system was put into practice, prisoners were released after consensus was reached between the affected parties (Knapp, Flach, and Aybogan Citation2016, 179). In the city of Serê Kaniyê the number of prisoners has dropped from 200 during the Assad regime time to 20 as of early 2016 (Anderson and Egret Citation2016). Overall, there is a high rate of case resolution at the level of the Peace and Consensus Committees, which indicates wide acceptance of the new justice system by the local population (Shilton Citation2019; Cemgil and Hoffman Citation2016, 65). Crime rates have dropped, especially with regard to theft, and as for crimes related to patriarchal violence, the number of honor killings have declined noticeably in NES (Ayboga Citation2014). According to the women’s organizations in NES, their work has resulted in abusive men leaving their wives. In Hilelî, Qamişlo, any man who beats his wife is socially ostracized and domestic violence seems to have vanished (Knapp, Flach, and Aybogan Citation2016, 87). In 2017 there were approximately 200 divorces, mostly due to cases of polygamy and child marriage (Nordland Citation2018). In Kobani, leading politician Idris Nasser states that

A lot of husbands would not let women go out and would force them to stay in the house to take care of the children. Now everything has changed. (quoted in Argentieri Citation2016)

For example, underage marriage. A girl of only 14 would be given to a man to be married. But not any more. Another thing is a second marriage. A man could take four women for himself. But not anymore. Now only one woman. Before, if I had brothers … within our house I didn’t have the right to anything in my family—not property or money or land. But now, women have the right to all those things. (Shilton Citation2019)

Conclusion

In conclusion, NES serves as an interesting example of how patriarchal violence can be addressed within a justice system that is based on principles of restorative and transformative justice. It is most likely that the exact approach of NES to addressing patriarchal violence cannot be copied and implemented in other societies and legal cultures, however, I hope that this text has inspired the reader and provided new ways of thinking about law and justice as tools for achieving societal change. I come from a Swedish legal context and consider it unfortunate that the discussion on addressing patriarchal violence mostly revolves around further criminalization and increasing punishment (see Johansson Citation2018). While it is necessary for society to send the message that patriarchal violence is unacceptable, reconciliation is equally necessary if we want to be able to ensure social peace on an individual and community level. At the same time, transforming the offender through means of education and rehabilitation is vital in order to eliminate patriarchal attitudes in society. However, we must keep in mind that patriarchal attitudes cannot be eliminated in the legal arena only. They need to be confronted everywhere, all the time. Only then is it possible to radically transform the world.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Thomas McClure and Robin Fleming from the Rojava Information Center who, despite the ongoing invasion in North and East Syria, have helped me in gathering the necessary materials for this article.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Although formally referred to as NES, the region is famously known by the name Rojava, which is the Kurdish word for West (referring to Western Kurdistan). In consideration of the political project being a multiethnic one, the name was formally changed to its current one on September 6, in 2018.

2 Violence in this context is understood as physical, psychological, material and economic. Patriarchal violence is thereby understood as any violence that is rooted in the patriarchal power structures that it upholds and reproduces.

4 Translated by the Center.

5 Kongreya Star is an umbrella organization, founded in 2005, which consists of different women’s organizations in NES.

3 Note that although the region of Afrin is formally a part of NES, it is currently under occupation after a Turkish invasion which commenced in January 2018. The same goes for parts of the Euphrates and Jazira regions of NES in which the cities of Serê Kaniyê, Girê Spî and its surrounding villages are under Turkish occupation.

References

- Allsopp, Harriet, and Wladimir van Wilgenburg. 2019. The Kurds of Northern Syria. London: I.B. Tauris.

- Anderson, Tom, and Eliza Egret. 2016. “Democratic Confederalism in Kurdistan.” Corporate Watch, April 18. https://corporatewatch.org/democratic-confederalism-in-kurdistan/.

- Argentieri, Benedetta. 2016. “Syria’s War Liberates Kurdish Women as it Oppressed Others.” Reuters, February 29. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-mideast-crisis-syria-women/syrias-war-liberates-kurdish-women-as-it-oppresses-others-idUSKCN0W20F4.

- Auerbach, Jerold. 1984. Justice Without Law. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Ayboga, Ercan. 2014. “Consensus is Key: New Justice System in Rojava.” New Compass, October 13. Translated by Janet Biehl. http://new-compass.net/articles/consensus-key-new-justice-system-rojava.

- Bradey, Anthony. 1985. “Taking Law Less Seriously: An Anarchist Legal Theory.” Legal Studies 5 (2): 133–151. doi:10.1111/j.1748-121X.1985.tb00604.x.

- Cemgil, Can, and Clemens Hoffman. 2016. “The ‘Rojava Revolution’ in Syrian Kurdistan: A Model of Development for the Middle East?” Ruptures and Ripple Effects in the Middle East and Beyond 47 (3): 53–76. doi:10.19088/1968-2016.144.

- Davies, Margaret. 2017a. Asking the Law Question. 4th ed. Sydney: Thomson Reuters.

- Davies, Margaret. 2017b. “Keynote: Reforming Law: The Role of Theory.” In New Directions for Law in Australia: Essays in Contemporary Law Reform, edited by Ron Levy, Molly O’Brien, Simon Rice, Pauline Ridge, and Margaret Thornton, 11–23. Acton: Australian National University Press.

- Duman, Yasin. 2017. “Peacebuilding in a Conflict Setting: Peace and Reconciliation Committees in De Facto Rojava Autonomy in Syria.” Journal of Peacebuilding & Development 12 (1): 85–90. doi:10.1080/15423166.2017.1285245.

- Edwards, Alice. 2010. Violence Against Women Under International Human Rights Law. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Groll, Elias, and Lara Seligman. 2019. “No Cease-Fire in Syria as Joint Russian-Turkish Patrols Begin.” Foreign Policy, October 9. https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/11/04/security-brief-no-cease-fire-in-syria-as-joint-russian-turkish-patrols-begin/.

- Johansson, Linnea. 2018. “Guide: Det vill partierna göra inom brott och straff” [Guide: This is What the Parties Want to Do within Crime and Punishment]. Metro, September 2. https://www.metro.se/artikel/stor-guide-det-vill-partierna-göra-kring-invandring-och-integration.

- Knapp, Michael, Anja Flach, and Ercan Aybogan. 2016. Revolution in Rojava. London: Pluto Press.

- Kropotkin, Pëtr. 1886. Law and Authority: An Anarchist Essay. London: International Publishing Co.

- Magpie, Jo. 2016. “Regaining Hope in Rojava.” OpenDemocracy, June 6. https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/north-africa-west-asia/regaining-hope-in-rojava/.

- McGlynn, Clase. 2011. “Feminism, Rape and the Search for Justice.” Oxford Journal of Legal Studies 31 (4): 1–18. doi:10.2307/41418844 doi: 10.1093/ojls/gqr025

- Nordland, Rod. 2018. “Women Are Free, and Armed, in Kurdish-Controlled Northern Syria.” New York Times, February 24. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/02/24/world/middleeast/syria-kurds-womens-rights-gender-equality.html.

- Öcalan, Abdullah. 2017. The Political Thought of Abdullah Öcalan. London: Pluto Press.

- Rwanduzy, Mohammed. 2019. “Kurds Strike Deal with Damascus for Gov’t Force Entry of North Syria Towns: Officials.” Rudaw, October 13. https://www.rudaw.net/english/middleeast/syria/131020194.

- Shilton, Dor. 2019. “In the Heart of Syria’s Darkness, a Democratic, Egalitarian and Feminist Society Emerges.” Haaretz, June 9. https://www.haaretz.com/middle-east-news/.premium.MAGAZINE-amid-syria-s-darkness-a-democratic-egalitarian-and-feminist-society-emerges-1.7339983.

- Sly, Liz. 2019. “Captured ISIS Fighters Get Short Sentences and Art Therapy in Syria.” The Washington Post, August 14. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2019/08/14/captured-isis-fighters-get-short-sentences-art-therapy-syria/.

- Vanek, David. 2001. “Interview with Murray Bookchin.” Harbringer, A Journal of Social Ecology 2: 1. social-ecology.org/wp/2001/10/harbinger-vol-2-no-1-—-murray-bookchin-interview/.

- Wali, Zhelwan. 2019. “Syria Kurds Says Damascus Deal is Purely about Defense.” Rudaw, October 14. https://www.rudaw.net/english/interview/14102019.