ABSTRACT

Ambivalence and dissonance research provides insights into the experiences and consequences of cognitive conflict. Despite the conceptual overlap between both conflicts, they are typically discussed and applied separately. Based on the notion that ambivalence reflects pre-decisional and dissonance reflects post-decisional conflict, we propose the Model of Ambivalent Choice and Dissonant Commitment (AC/DC model). The AC/DC model outlines that both conflicts are rooted in attitudes; however, as they succeed each other in decision-making, they entail distinct cognitive and emotional underpinnings, leading to different motivational consequences. Their sequence in decision-making entails far-reaching interrelations, depending on whether people cope with the conflict-induced discomfort or the conflict origins. Thereby, the AC/DC model elucidates how conflicts are navigated within decision-making and how they either resolve or manifest over time. This offers various novel implications, for instance, about conflicts regarding time-sensitive decisions, conflicts between alternatives, conflicts outside of decision situations, and conflict resolution and behaviour change.

Introduction

Cognitive conflicts are motivating forces affecting how people feel, think, and act (Festinger, Citation1957; Hofmann et al., Citation2012; McGregor et al., Citation2019). They pervade decision-making, social interactions, and arguably basic needs (Hillman et al., Citation2022; van Harreveld et al., Citation2015). Ample evidence has revealed that experiences of conflict are aversive and reduce well-being (Elliot & Devine, Citation1994; Moberly & Dickson, Citation2018; Vaccaro et al., Citation2020).

Two prominent theoretical research traditions on the nature of cognitive conflict concern attitudinal ambivalence and cognitive dissonance (Cooper, Citation2007; van Harreveld et al., Citation2015). Although the two works of literature have mostly been discussed independently, they share conceptual similarities. Indeed, Proulx et al. (Citation2012) argue that the origins of ambivalence and dissonance and the palliative responses to cope with these conflicts are similar. Therefore, these authors propose that the experience of and coping with ambivalence and dissonance (among other cognitive conflicts) can be commonly understood as a manifestation of and compensation for expectancy violations.

Despite these similarities, ambivalence and dissonance have been described as distinct cognitive conflicts – which closely succeed each other in relation to the decision-making process. Specifically, ambivalence arguably reflects pre-decisional conflict, whereas dissonance represents post-decisional conflict (Dalege et al., Citation2018; Jonas et al., Citation2000; van Harreveld, van der Pligt, et al., Citation2009). This argument is supported by research on ambivalence that focuses primarily on how people experience and cope with conflict before and during decision-making (Schneider & Schwarz, Citation2017; van Harreveld et al., Citation2015) and research on cognitive dissonance that focuses predominantly on how people experience and cope with conflicts after having committed to certain actions (Brehm & Cohen, Citation1962; Festinger, Citation1964; Festinger et al., Citation1956; Harmon-Jones & Mills, Citation2019; Joule & Beauvois, Citation1997; Pauer, Rutjens, et al., Citation2024). Nonetheless, we know little about how the experiences of cognitive conflicts differ from and affect each other throughout decision-making because the two lines of research have mostly been discussed separately.

Consider, for instance, a person named Alex, who feels conflicted about the decision to eat meat while browsing a restaurant menu. Based on the ambivalence literature, it may be inferred why and how Alex experiences conflict before making the decision and how Alex copes with this conflict before ordering; and based on the dissonance literature, it may be inferred why and how Alex experiences conflict after making the decision and how Alex copes with this conflict after ordering (Buttlar & Pauer, Citation2024). Nonetheless, it remains in question how experiences of conflict and ensuing coping efforts differ before compared to after the decision and whether and how pre- and post-decisional conflicts affect each other intertemporally within such decision situations: Will Alex experience less post-decisional conflict after having coped with the pre-decisional conflict before ordering? And having dealt with pre- and post-decisional conflict in the restaurant, will Alex experience less (pre-decisional) conflict in similar decisions in the future?

In the present paper, we shed light on the nature of and interrelations between pre- and post-decisional cognitive conflicts within this and similar decision-making situations. Drawing on the notion that pre-decisional conflicts can be understood through the lens of ambivalence, whereas post-decisional conflicts can be understood through the lens of dissonance (Dalege et al., Citation2018; Festinger, Citation1964; Jonas et al., Citation2000; van Harreveld, van der Pligt, et al., Citation2009), we propose that both conflicts affect each other within the process of decision-making. Therefore, we first review the empirical research on ambivalence and dissonance. Given that the ambivalence and dissonance literatures are relatively separate in their focus on one of the two conflicts, thisreview will allow us to outline the similarities and differences of pre- and post-decisional cognitive conflicts and elaborate on their interrelations throughout decision making. Secondly, we postulate the Model of Ambivalent Choice and Dissonant Commitment (the AC/DC model), outlining that ambivalent choices give rise to felt ambivalence prior to decisions, whereas dissonant commitments give rise to cognitive dissonance about past decisions. Based on this perspective, we further outline how felt ambivalence and dissonance affect each other and how their respective coping mechanisms can contribute to the resolution of cognitive conflict in the short and long run. We then illustrate the AC/DC model revisiting the aforementioned example of Alex’s conflicted decision about eating meat. Thirdly, we explore the theoretical implications of the AC/DC model and the steps necessary to put the model into practice. Thereby, the AC/DC model provides a holistic picture of cognitive conflict across the entire span of decision-making, highlighting the interrelations between pre- and post-decisional conflicts in both the short and long term

Cognitive conflict within decision-making

Cognitive dissonance

The psychological state of cognitive dissonance was first described by Leon Festinger (Citation1957), who prominently outlined that dissonance arises if two cognitions are inconsistent – dissonant – with each other. Festinger (Citation1957) suggested that these cognitions are knowledge elements such as individual perceptions, information, assumptions, or opinions; and cognitive dissonance arises when a cognition opposes another cognition. More specifically, Festinger (Citation1957) posited that the degree of cognitive dissonance is determined by 1) the importance of the conflicting cognitions (the greater the importance of the dissonant cognitions, the greater the magnitude of the dissonance) and 2) the ratio of cognitions (the higher the proportion of dissonant-to-consonant cognitions, the greater the dissonance).

Empirical support for cognitive dissonance theory comes from a vast number of studies in which people have to commit to an action: In induced-compliance paradigms, people are prompted to act contrary to their attitudes, eliciting dissonance if people cannot attribute their behaviour to an external factor (such as a large compensation; e.g., Festinger & Carlsmith, Citation1959; for current discussions see; Pauer, Linne, et al., Citation2024; Vaidis et al., Citation2024); in free-choice paradigms, people have to decide between two alternatives, leading to dissonance especially when picking between equally attractive options (e.g., Brehm, Citation1956); and in effort justification paradigms, people are asked to engage in an unpleasant activity for a (presumably) desirable outcome, promoting dissonance when the invested effort increases (e.g., Aronson & Mills, Citation1959). These paradigms support the idea that cognitive conflict can lead to the experience of dissonance.

While Festinger (Citation1957) originally argued that several kinds of dissonant cognitions can elicit conflict as long as they are important and in relevant relation to each other, he later posited that dissonance arises especially subsequent to a decision, after people have committed to a course of action (Festinger, Citation1964). Empirical research has indeed largely shown that cognitive dissonance occurs when people hold a cognition that is in opposition to their behaviour (Harmon‐Jones et al., Citation2009; McGregor et al., Citation2019). It has moreover been suggested that people experience dissonance, primarily after voluntary commitments (Brehm & Cohen, Citation1962; Harmon‐Jones et al., Citation2009; Joule & Beauvois, Citation1997). A commitment can be conceptualised as an expectation to maintain or engage in a stance or course of action (Festinger, Citation1964; Janis & Mann, Citation1977). Such commitment typically translates a decision into some kind of behaviour (Kiesler & Sakumura, Citation1966; Marzano & Marzano, Citation2008). Notably, commitments can vary in strength, with stronger commitments resulting from voluntary, important, irrevocable, explicit, or repeated decisions (Kiesler & Sakumura, Citation1966). Brehm (Citation1960), for instance, demonstrated that people experience more dissonance when pledging to eat disliked vegetables repeatedly over the next weeks compared to eating it only on the present day, providing experimental evidence for a pivotal role of commitment in dissonance.

Notably, other boundary conditions that affect how and when dissonance arises have been investigated: People have been found to experience dissonance especially if they feel responsible when committing to a behaviour that foreseeably leads to aversive consequences (Cooper & Fazio, Citation1984; but see; Harmon-Jones et al., Citation1996); and it has been suggested that they only do so if the conflicting cognitions are self-relevant (Aronson, Citation2019). Conflict may, for instance, be self-relevant in situations in which people commit to behaviours that threaten their positive self-image and self-integrity as competent, coherent, or moral persons (Aronson, Citation1968, Citation2019; Steele, Citation1988).

The driving force underlying these effects of dissonance is the experience of discomfort arising from the violation of the fundamental need for consistency (Festinger, Citation1957). This aversive state of dissonance leads to efforts to resolve the dissonant discomfort by aligning the inconsistent cognitions with behaviours (Festinger, Citation1957; McGrath, Citation2017; Zanna & Cooper, Citation1974). In fact, following dissonance inductions, people not only report experiencing more discomfort (Elliot & Devine, Citation1994), but they also show heightened neural and facial activity related to negative affect (Martinie et al., Citation2013; van Veen et al., Citation2009). Crucially, this discomfort motivated people to cope with their dissonance in all these studies.

Dissonance thus serves as a powerful motivator for attitude change, compelling people to seek conflict resolution by altering their existing attitudes. For instance, when people are prompted to state that a boring task was fun, they subsequently report liking it more (Festinger & Carlsmith, Citation1959); or when people have to pick between alternatives, their attitudes towards the alternatives spread, and they report liking the chosen alternative and disliking the unchosen alternative more after their commitment (Brehm, Citation1956). Altering attitudes this way allows people to reduce dissonance and the accompanying discomfort.

There are various other coping strategies that facilitate the resolution of dissonance, which may or may not include attitude change. Festinger (Citation1957) initially proposed three methods of dissonance reduction: changing dissonant cognitions (e.g., replacing a belief that a behaviour is harmful with the belief that it is unproblematic), adding new cognitions that lead to consonance (e.g., arguing how a side-effect of something harmful makes it beneficial in another regard), and trivialising dissonant cognitions (e.g., suggesting that a harmful behaviour only occurs rarely). Since then, additional strategies have been identified that people use to cope with dissonance (Cancino-Montecinos et al., Citation2020; McGrath, Citation2017). This includes the denial of responsibility (e.g., believing that there is no alternative to harmful behaviour; Gosling et al., Citation2006), distraction and forgetting (Zanna & Aziza, Citation1976), and even behaviour change (Aronson et al., Citation1991).

These coping strategies arguably aim at resolving dissonance as efficiently as possible. The efficiency of the coping strategies depends on the cognitions’ importance and resistance to change (Festinger, Citation1957). Cognitions are more resistant to change if they are grounded in personal experience, if they have many consonant cognitions (making it likely that people also experience conflict when altering the cognition), and if changing them is costly in terms of effort, pain, or forfeited joy (Harmon-Jones & Mills, Citation2019; McGrath, Citation2017). As a result, people may prefer post-decisional attitude change over behaviour change because it is more efficient to stick with the commitment by changing attitudes rather than backing down from commitments (e.g., Festinger et al., Citation1956).

In fact, the action-based model of dissonance (Harmon-Jones & Harmon-Jones, Citation2023; Harmon‐Jones et al., Citation2009) proposes that people who commit to an action are motivated to put their intended behaviour into practice. According to the model, dissonance arises mostly if conflicting cognitions stand in the way of actions; this signals that cognitive inconsistency needs to be addressed to pursue the action. To maintain a given course of action, the conflicted decisions thus typically engender attitude change and similar coping strategies, whereby people resolve dissonance in a given situation (Harmon-Jones & Harmon-Jones, Citation2002). Harmon-Jones and Harmon-Jones (Citation2002) have, for instance, shown that people change their attitudes more if they have to decide between rather equal alternatives in a free-choice paradigm when being in an action-oriented mindset (e.g., being induced by thinking of the steps to accomplish a project or goal) compared to a neutral mindset (e.g., being induced by writing about an ordinary day or an unresolved problem). This corroborates the notion that dissonance resolution serves the purpose to allow efficient action based on commitments.

Attitudinal ambivalence

Similar to previous conceptualisations of conflict (Festinger, Citation1957; Lewin, Citation1935), ambivalence arises if people simultaneously hold at least two opposing evaluations towards an attitude object (Cacioppo et al., Citation1997; Kaplan, Citation1972). Such opposing evaluations lay the basis for potential (or objective) ambivalence, describing the degree to which an attitudinal structure includes both positive and negative evaluations of an attitude object (Priester & Petty, Citation1996). These inconsistent evaluations come to exist, for example, when people receive counter-attitudinal information about an attitude object; likewise, after changing an attitude, potential ambivalence may remain when past evaluations persist or resurface (Petty et al., Citation2006).

People may not only hold ambivalent evaluations but also feel ambivalent due to a meta-cognitive awareness of having an ambivalent attitude (Priester & Petty, Citation1996). This felt (or subjective) ambivalence increases in intensity as the number of inconsistent evaluations increases (Priester & Petty, Citation1996). This is especially the case if the inconsistent evaluations become simultaneously accessible (Newby-Clark et al., Citation2002; Pauer, Rutjens, et al., Citation2024). Newby-Clark et al. (Citation2002), for instance, demonstrated that people report experiencing more felt ambivalence, based on their potential ambivalence, when they are faster at recalling both positive and negative evaluations about controversial issues, such as abortion or capital punishment. Thus, felt ambivalence is more intense when a similar number of strongly positive and negative evaluations of an attitude object become simultaneously accessible.

Felt ambivalence occurs if people become aware of inconsistent positive and negative evaluations within their attitude and realise they are in conflict (van Harreveld et al., Citation2015). People, therefore, mainly experience felt ambivalence when they introspect and report on their attitudes (Newby-Clark et al., Citation2002; Priester & Petty, Citation1996), when they anticipate commitment to an upcoming decision (van Harreveld, Rutjens, et al., Citation2009), or when they are making a decision (Buttlar & Walther, Citation2018; Schneider et al., Citation2015). This is, among other things, evident in mouse-tracking studies, which make it possible to quantify people’s conflicts by tracking their mouse trajectories as they make decisions (Freeman & Ambady, Citation2010). For instance, it has been shown within the mouse-tracking paradigm that people are more conflicted when evaluating or deciding to eat (ambivalent) unhealthy food compared to more univalent food (Schneider et al., Citation2015; Stillman et al., Citation2017). In fact, the mouse movements between the two decisional alternatives indicate that ambivalent people are torn between simultaneously accessible, inconsistent positive and negative evaluations (Schneider & Mattes, Citation2021; Schneider et al., Citation2015).

Notably, aversive felt ambivalence arises mainly when inconsistent evaluations are important and relevant to a decisional context (Nohlen et al., Citation2016; Thompson & Zanna, Citation1995). In fact, Thompson and Zanna (Citation1995) have shown that felt ambivalence is more pronounced in people who feel highly involved in a topic and tend to be concerned with making erroneous decisions. To this end, Nohlen et al. (Citation2016) demonstrated in a facial electromyography study that people experience negative affect in response to ambivalence only when both positive and negative evaluations are relevant to the decision (e.g., “Bob is intelligent and dominant. Do you think Bob is a good collaborator?”), but not when the same evaluations are irrelevant to the decision (“Do you think Bob can write a good research paper?”). In addition, a negative valence of an evaluation leads to stronger experiences of felt ambivalence when the pre-dominant attitude is positive than vice versa: this is because negativity carries more weight on people’s attitudes (Cacioppo et al., Citation1997; Snyder & Tormala, Citation2017). As such, the importance, relevance, and weight of the conflicting cognitions play a crucial role in the emergence of ambivalence before and during decisions, similar to their role in the emergence of dissonance.

Felt ambivalence can, however, also arise when people hold univalent attitudes. It has, for instance, been shown that people who merely anticipate the existence of counter-attitudinal information about their univalent attitude already experience more ambivalence than people who do not anticipate such conflicting information (Priester et al., Citation2007). In addition, people who hold a univalent attitude can experience felt ambivalence if they realise that others have contradicting opinions about an attitude object (Priester & Petty, Citation2001; Toribio-Flórez et al., Citation2020). And lastly, people might experience felt ambivalence even if they hold a univalent attitude because they desire to have a different attitude (DeMarree et al., Citation2014). Hence, felt ambivalence arises not only from potential ambivalence but also from conflicts rooted in other causes. Thus, anticipating a conflicted attitude in general can lead to the experience of conflict, especially before making a decision.

Because felt ambivalence is aversive and elicits discomfort, people employ emotion- and problem-focused strategies to cope with ambivalence-induced negative affect (Rothman et al., Citation2017; van Harreveld, van der Pligt, et al., Citation2009). The Model of Ambivalent Induced Discomfort (MAID; van Harreveld, van der Pligt, et al., Citation2009) outlines that emotion-focused coping is aimed at reducing ambivalent discomfort, for instance, by postponing a decision (Durso et al., Citation2016; Itzchakov et al., Citation2020) or obviating the responsibility for a decision (Buttlar & Walther, Citation2019; Pauer, Rutjens, et al., Citation2024). For example, Durso et al. (Citation2016) demonstrated that when people are asked to decide whether they would promote or fire a co-worker, they prefer to delay that decision when they have ambivalent compared to univalent attitudes, and they actually do so, as apparent in the time it takes them to make decisions. In contrast to emotion-focused coping, problem-focused coping is aimed at the root of the problem and reduces ambivalence and discomfort by changing inconsistent evaluations underlying an ambivalent attitude. In an attempt to change their inconsistent evaluations, people can either process and seek information (Buttlar et al., Citation2023; Clark et al., Citation2008; Nordgren et al., Citation2006; Pauer et al., Citation2022; Sawicki et al., Citation2013) or persuade themselves even without enquiring new information (Vaughan-Johnston et al., Citation2023). For instance, the research by Sawicki et al. (Citation2013) has demonstrated that people are more interested in and seek more information when feeling more ambivalent about an issue; this effect was especially pronounced in people who were not knowledgeable about the topic because they anticipated that seeking information could actually help them to reconcile their inconsistent evaluations. These problem-focused coping strategies thereby help people change positive or negative evaluations or both (i.e., increasing positive evaluations while decreasing negative evaluations or vice versa). Consequently, problem-focused (and not emotion-focused) coping leads to the spreading of evaluations that promotes the formation of a more univalent attitude.

Both emotion- and problem-focused coping strategies can help people deal with conflicted decision-making; however, only problem-focused coping strategies aimed at the conflicted attitude itself can help people adjust their ambivalent attitude. Whether people engage in emotion- or problem-focused coping is determined by their capacities to engage in more effortful coping: When people have low motivation and/or cognitive resources available to them, they tend to engage in emotion-focused coping; when people have sufficient motivation and cognitive resources available, they will engage in problem-focused coping (van Harreveld et al., Citation2015; van Harreveld, van der Pligt, et al., Citation2009).

Attitudinal ambivalence and cognitive dissonance at the intersection

From the empirical findings within the two lines of research, similarities and dissimilarities between dissonance and ambivalence become apparent. Both kinds of conflict overlap in the mechanism involved: Opposing cognitions threaten a need for consistency, leading to aversive arousal and discomfort that accompanies ambivalence and dissonance (Elliot & Devine, Citation1994; van Harreveld, Rutjens, et al., Citation2009). This is the case when people are consciously aware of these conflicts in situations where relevant but inconsistent components underlying ambivalence or dissonance become accessible (McGregor et al., Citation2019; Newby-Clark et al., Citation2002; Nohlen et al., Citation2016). These similarities align with the original conceptualisation of dissonance in terms of conflicting relevant cognitions that elicit cognitive conflict (Festinger, Citation1957; McGregor et al., Citation2019). In fact, even the coping mechanisms involved in both kinds of conflicts have similar functions, as they either focus on dealing with the discomfort or resolving the origin of the conflict itself (Cancino-Montecinos et al., Citation2020; van Harreveld, van der Pligt, et al., Citation2009).Footnote1 Proulx et al. (Citation2012) have consequently argued that the experience of dissonance and ambivalence and their ensuing coping processes fall under the same umbrella of inconsistency compensation as a response to violated expectations.

Despite these similarities between dissonance and ambivalence, research has distinguished between the two concepts by referring to the pre- or post-decision stage in which the conflicts occur. Specifically, an essential distinction between ambivalence and dissonance in the decision-making process concerns that ambivalence reflects a pre-decisional conflict, whereas dissonance reflects a post-decisional conflict (Dalege et al., Citation2018; de Liver et al., Citation2007; Festinger, Citation1964; van Harreveld, van der Pligt, et al., Citation2009).

Indeed, the experience of felt ambivalence includes anticipatory emotional and motivational processes – such as uncertainty or regret about the outcomes of the decision (Itzchakov & van Harreveld, Citation2018; Pauer et al., Citation2022; van Harreveld et al., Citation2014; van Harreveld, Rutjens, et al., Citation2009). For instance, three studies by van Harreveld, van der Pligt, et al. (Citation2009) show that people who have to make a decision about whether to write a positive or negative essay about an ambivalent topic experience more physiological arousal compared to participants who did not have to make such a decision. Crucially, people's ambivalence-induced discomfort was mediated by their uncertainty about the decision. In a similar vein, Itzchakov and van Harreveld (Citation2018) demonstrated across three studies that the experience felt ambivalence especially occurs if people are (made) aware that a decision to voice a univalent opinion in an essay about an ambivalent topic may be regretted.

In comparison, the experience of dissonance may include a variety of negative emotions inferred from the commitment, like regret, guilt, anger, anxiety, or shame (Bastian et al., Citation2011; Cancino-Montecinos et al., Citation2020; McGrath, Citation2017). Cancino-Montecinos et al. (Citation2020), for instance, asked people about a variety of emotions they experienced while writing a counter-attitudinal essay. Their results indicate that people experience various negative emotions due to their counterattitudinal behaviour. For some people, the resulting dissonance seems to be associated with rather specific emotions related to either anger (including anger, frustration, hostility, and irritation), fear or anxiety (including fear, anxiety, and nervousness), and self-conscious emotions (including guilt and shame); other people, however, perceive overall negative emotions across these factors or mixed emotions including both overall negative emotions and overall positive emotions (e.g., enthusiasm, pride, relief, inspiration).

Thus, we propose that the experience of cognitive conflict is determined based on the timing within the process of decision-making: On the one hand, aversive felt ambivalence (including uncertainty and anticipated regret) is experienced due to an ambivalent choice in which inconsistent evaluations are accessible that are relevant for the decision; on the other hand, discomforting dissonance (including anxiety, regret, guilt, anger or shame) is experienced due to an accessible dissonant commitment that is inconsistent with (parts of) a relevant attitude. Even though previous lines of research on ambivalence and dissonance have hinted at this conceptual distinction of ambivalence and dissonance as pre- and post-decisional conflict, we still understand little about whether these interact within decision-making.

So far, foundational studies show that people with more ambivalent attitudes about an issue change their attitudes to a larger extent if they are brought to engage in counter-attitudinal behaviour – presumably to cope with their dissonance (Leippe & Eisenstadt, Citation1994). In addition, people who are ambivalent not only experience more physiological arousal when they are told that they will have to make a choice and commit to one side of an issue, but their physiological arousal remains even after the decision (van Harreveld, Rutjens, et al., Citation2009). These findings indicate that cognitive conflicts before and after decisions could affect each other throughout the decisional process. It remains in question, however, how these pre- and post-decisional conflicts interact, which boundary conditions determine their interactions, and how these interactions shape the process of experiencing and coping with conflict.

The model of ambivalent choice and dissonant commitment

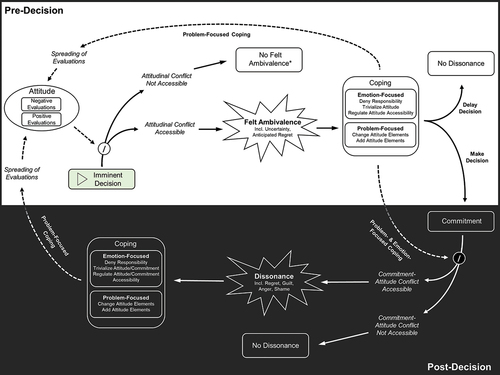

In the present paper, we propose the Model of Ambivalent Choice and Dissonant Commitment (AC/DC model), in which we describe the interrelations between attitudinal ambivalence and cognitive dissonance and detail how they affect each other (see ). Although Festinger (Citation1957) initially did not distinguish between pre- and post-decisional conflicts, ensuing research suggests that the cognitions involved in these conflicts, their affective correlates, and the respective coping mechanisms seem to depend on the phase across the course of decision-making. In line with this research, we thus propose to refer to pre-decisional conflicts as felt ambivalence and post-decisional conflicts as dissonance (Dalege et al., Citation2018; Festinger, Citation1964; Jonas et al., Citation2000; van Harreveld, van der Pligt, et al., Citation2009). That is, before a decision, it is mostly the awareness of inconsistent evaluations towards an attitude object that may lead to cognitive conflict (ambivalent choice); after a decision, however, it is mostly the awareness of an inconsistency between a commitment and an inconsistent evaluation that leads to cognitive conflict (dissonant commitment). Both conflicts are thus based on accessible and relevant inconsistent cognitions involving attitudes (McGregor et al., Citation2019); however, due to differences in the origins and the chronology of decision-making, we suggest within the AC/DC model that people experience and cope with pre- and post-decisional conflicts differently.

Figure 1. Depiction of the AC/DC model, including the cyclical processes that determine the experience of and coping with cognitive conflict resulting from ambivalent choices and dissonant commitments.

The AC/DC model describes how attitudes influence experiencing conflict before and after making decisions and the consequences of how people cope with conflict-induced discomfort or the inconsistency underlying the conflict across the course of decision-making. While previous research highlighted the similarities between ambivalence and dissonance (Proulx et al., Citation2012) or hinted at potential differences between ambivalence and dissonance within decision-making (Dalege et al., Citation2018; Festinger, Citation1964; Pauer, Rutjens, et al., Citation2024; van Harreveld, van der Pligt, et al., Citation2009), the AC/DC model offers a comprehensive account of cognitive conflict throughout the phases of decision-making, explaining how felt ambivalence influences subsequent experiences of dissonance and how dissonance (conversely) affects future experiences of felt ambivalence. Importantly, it not only delves into the immediate impact of these cognitive conflicts but also sheds light on their short-term and long-term effects, explaining conflict resolution and manifestation over time.

Below, we outline how ambivalence and dissonance affect each other within decision-making according to the AC/DC model (see ). We first outline how ambivalent choices elicit cognitive conflict before people make decisions, how people experience the resulting felt ambivalence, and how people cope with it; we then describe how dissonant commitments trigger cognitive conflict after people have made decisions, how people experience the resulting dissonance, and how they cope with it; we lastly outline how felt ambivalence and dissonance interact with each other due to their succession within decision-making and how this might lead to the resolution or manifestation of conflict. An overview of the key constructs within the AC/DC model and tangible examples can be found in .

Table 1. Key constructs within the model of ambivalent choice and dissonant commitment including tangible examples and references to the theoretical arguments and/or empirical findings.

Ambivalent choice – pre-decisional conflict

When facing an imminent decision, we argue that people’s experiences of conflict depend on whether they face an ambivalent choice: People experience felt ambivalence mostly when introspecting on inconsistent positive and negative evaluations within their attitudes to make decisions (van Harreveld et al., Citation2015; van Harreveld, van der Pligt, et al., Citation2009). This is apparent when people make decisions that entail behavioural commitments (Schneider & Schwarz, Citation2017), but decisions can also entail commitments during the formation and expression of an opinion (Howe & Krosnick, Citation2017; Schneider et al., Citation2015). Consequently, people experience felt ambivalence, especially if evaluations become accessible during decision-making that are relevant but also contradict each other (Newby-Clark et al., Citation2002; Nohlen et al., Citation2016; Pauer, Rutjens, et al., Citation2024). This mainly entails intra-attitudinal inconsistencies but could also include other attitudinal discrepancies.Footnote2 If such discrepancies do not become accessible or are not relevant to the decision, people will not experience felt ambivalence, enabling them to make an unconflicted decision.

Felt ambivalence is aversive and accompanied by a variety of emotions, such as uncertainty or anticipated regret (Itzchakov & van Harreveld, Citation2018; Pauer et al., Citation2022; van Harreveld et al., Citation2014). In fact, if people experience ambivalence, they will feel literally torn due to their ambivalent attitudes when inconsistent evaluations become accessible (Schneider et al., Citation2013, Citation2015): People sit on the fence and do not know in which direction they have to decide. Felt ambivalence thus motivates people to cope with their discomfort and their conflict.

Various strategies can facilitate coping with the discomfort during ambivalent choices (van Harreveld, van der Pligt, et al., Citation2009). The easiest way to avoid the discomforting conflict might be to postpone a decision (Anderson, Citation2003; Nohlen, Citation2015; Tversky & Shafir, Citation1992). However, even if people have to make decisions based on inconsistent evaluations, they tend to prefer a variety of emotion-focused coping strategies to avoid negative affect. They may obviate responsibility for a decision (van Harreveld, van der Pligt, et al., Citation2009), or they may trivialise one of the inconsistent evaluations to make it less relevant for a decision (cf. Nohlen et al., Citation2016). In addition, they may regulate the accessibility of ambivalent attitude by directly (dis-)activating certain evaluations in the face of felt ambivalence (Fishbach et al., Citation2010). This strategy may include the suppression or distraction from undesired attitude elements as well as the concentration on desired attitude elements or the pre-emption of their loss (Maio & Thomas, Citation2007). Through all of these strategies, people can cope with the discomfort and negative affect while experiencing felt ambivalence.

People can also engage in problem-focused coping to reconcile conflicted attitudes when making decisions. Similar to Festinger’s modes of dissonance reduction (Festinger, Citation1957), people can resolve their ambivalence by changing or adding cognitions that shift their attitude. In fact, a breadth of research has shown that people selectively focus on information, helping to regain a univalent attitude and facilitate effective decision-making (van Harreveld et al., Citation2015). Even in the absence of novel information, though, people might cope with conflict by adjusting existing attitudes. In fact, self-persuasion research suggests that people can change the validity of inconsistent evaluations to re-appraise their attitudes (Fishbach et al., Citation2010; Lu et al., Citation2015; Maio & Thomas, Citation2007; Vaughan-Johnston et al., Citation2023). This may, for instance, be achieved by motivated interpretation or reintegration of certain attitude elements (for an in-depth discussion of available strategies, see Maio & Thomas, Citation2007). These strategies allow people to reduce the inconsistency within their evaluations through a spreading of evaluations, which leads to a less ambivalent attitude and reduced ambivalence-induced discomfort.

Notably, these strategies help people not only to deal with their felt ambivalence but also to make decisions. When experiencing ambivalence, people’s choices can generally go in either direction with their decision. In fact, it has been argued that people try to come to an optimal decision when dealing with ambivalence before making decisions due to the anticipation of regret (Festinger, Citation1964; van Harreveld, van der Pligt, et al., Citation2009). In many cases, however, their coping efforts already lean towards a pre-dominant attitude when dealing with felt ambivalence. For instance, emotion-focused coping, such as the obviation of responsibility, may allow people to side with their pre-dominant attitude without discomfort (van Harreveld, van der Pligt, et al., Citation2009). Even problem-focused coping, such as information seeking, is often biased, and people search for information that aligns with their pre-dominant attitude (Clark et al., Citation2008; Itzchakov & van Harreveld, Citation2018; Sawicki et al., Citation2013) while avoiding information that opposes it (Clark et al., Citation2008). Thus, people can cope flexibly with felt ambivalence to make a sensible decision, with the selection of coping strategies being determined by the ability and motivation to engage in systematic and unbiased coping (van Harreveld, van der Pligt, et al., Citation2009).

Dissonant commitment – post-decisional conflict

After a decision, we argue that people’s experiences of cognitive conflict depend on whether they made a dissonant commitment: People experience dissonance if they commit to an attitude-inconsistent stance or behaviour. Crucially, people are more likely to experience dissonance when holding ambivalent attitudes. While people can commit to attitude-inconsistent behaviours based on univalent attitudes without an ambivalent choice, we propose that they are more likely to commit to attitude-inconsistent behaviours based on ambivalent attitudes. To an extent, for ambivalent attitude holders, having to make a dichotomous choice inevitably means that they have to choose against one of their inconsistent evaluations (van Harreveld, Rutjens, et al., Citation2009); and in most cases, people will not be entirely ambivalent but will be leaning in one evaluative direction. In such cases, a decision against the pre-dominant evaluation is arguably more likely than when having an unequivocally positive or negative attitude. Indeed, ambivalent attitudes lead to less attitude-consistent behaviours compared to univalent attitudes (Conner et al., Citation2002, Citation2021): People who hold inconsistent evaluations towards an attitude object are more likely to act contrary to their pre-dominant attitude compared to people who only hold consistent evaluations. Thus, we suggest that ambivalent attitudes not only foster felt ambivalence before making decisions but also promote dissonance after making decisions, because when making dichotomous choices ambivalent attitude holders will in most cases have to act against (parts of) their overall attitude.Footnote3

Experiencing dissonance is generally aversive (Elliot & Devine, Citation1994), involving negative emotions such as regret, guilt, anger, and shame (Bastian et al., Citation2011; Cancino-Montecinos et al., Citation2020; McGrath, Citation2017). Thus, when people make a dissonant commitment that is inconsistent with (parts of) their attitude, and this inconsistency becomes accessible, they will experience discomfort. This dissonant discomfort, in turn, motivates people to cope with their negative affect and the conflict itself.

People have various options to cope with this dissonance, similar to those that help them cope with felt ambivalence. Although they cannot postpone the decision after having committed, they use similar strategies to cope with their dissonant discomfort as with felt ambivalence: They may deal with their discomfort by obviating the responsibility for their commitments (Gosling et al., Citation2006; Pauer, Rutjens, et al., Citation2024) or by trivialising their attitudes or commitments (Simon et al., Citation1995); and they can regulate the accessibility of the attitude or the commitment involved in the dissonant conflict. We argue that this includes the same strategies by which people regulate the accessibility of their attitude in the face of felt ambivalence, albeit in a way that helps them to live with their commitment. For instance, people might distract themselves from the dissonant conflict (Allen, Citation1965; Zanna & Aziza, Citation1976) or forget the conflict altogether (Elkin & Leippe, Citation1986). These emotion-focused strategies may help people cope with dissonant discomfort, although they do not directly address the roots of the conflict itself.

People also have various options to reconcile the conflict between their attitude and their commitment. Again, as with felt ambivalence, problem-focused strategies may refer to adding consonant cognitions or changing available cognitions (Festinger, Citation1957; van Harreveld, van der Pligt, et al., Citation2009). In fact, after having committed to a decision, people are likely to change their attitudes to align them with conflicting behaviours (Brehm, Citation1956; Festinger & Carlsmith, Citation1959; Pauer, Rutjens, et al., Citation2024). This may include altering cognitions to change relevant attitudes, for instance, by denying the harm caused by behaviour (Bastian & Loughnan, Citation2017); in addition, it may involve adding cognitions to change relevant attitudes, for example, by avoiding or seeking information (Cotton & Hieser, Citation1980; Frey, Citation1982; Frey & Wicklund, Citation1978). Thus, when people use problem-focused coping strategies to resolve conflict and not (only) discomfort, this might lead to a spreading of evaluations, helping them align their attitudes with their commitments (Brehm, Citation1956; Buttlar, Rothe, et al., Citation2021). By aligning the attitudes with the commitment, problem-focused coping strategies may help resolve the conflict itself and, in turn, also the discomfort stemming from it.

Taken together, we argue that people engage in emotion-focused coping to regulate their dissonant discomfort and in problem-focused coping to regulate the conflict itself. Therefore, the respective coping strategies are similar for both conflicts, but dissonance-induced coping can also tackle the cognitions about commitment in order to regulate the accessibility of conflict during emotion-focused coping. Importantly, dissonance-induced coping efforts seem to be more geared towards biased information processing than ambivalence-induced coping efforts, given that a commitment has already been made after a decision. Specifically, we suggest that dissonance-induced coping primarily results in efforts to reduce the discomfort or change the attitude rather than in efforts to change the commitment because the commitment is more resistant to change, and people aim to act efficiently upon decisions and commitments (cf. Harmon‐Jones et al., Citation2009). Thus, problem-focused coping usually does not involve a change of commitments.

Under certain circumstances, people can, however, reverse their commitments and change behaviour when experiencing dissonance (Stone & Fernandez, Citation2008). While people usually aim to act efficiently upon their decisions (Harmon‐Jones et al., Citation2009), we argue that people can use problem-focused coping not only to change attitudes to align them with their commitment but also in a way that goes against their commitments. In fact, people frequently wonder what could have happened if they had decided differently, especially if they experience regret (Fitzgibbon & Murayama, Citation2022; Kahneman, Citation1995). Such counterfactuals can be used to justify one’s decisions and retain the commitment, for instance, by making downward comparisons that validate decisions against worse or equal decisions; however, people can also use counterfactuals to facilitate effective future decision-making by engaging in upward comparisons regarding better alternatives (Epstude & Roese, Citation2008; Fitzgibbon & Murayama, Citation2022). Crucially, counterfactuals are not only instrumental for directly forming intentions regarding subsequent decisions but also for adjusting attitudes and mindsets; this way, counterfactuals can prepare affective, cognitive, and behavioural responses to facilitate subsequent decisions (Epstude & Roese, Citation2008). Thus, counterfactual thinking empowers people to either stick with their commitments or back down from them and make better decisions based on changed attitudes.

Cross-conflict interactions

Besides making it more likely that people experience dissonance when holding ambivalent attitudes, we suggest that both types of conflict can affect each other depending on how people cope with their pre- and post-decisional conflicts. Because felt ambivalence may often precede dissonance within decision-making, these dynamics are particularly apparent when examining the impact of coping with ambivalence on the subsequent experience of dissonance. Going beyond the chronology of conflicts within singular decision-making, we argue that coping with dissonance influences how people experience ambivalence in future decision-making.

An efficient way to cope with felt ambivalence ignited by an imminent decision involves postponing that decision (Nohlen, Citation2015; van Harreveld, van der Pligt, et al., Citation2009). Obviously, this helps people to temporarily escape the ambivalent decision about an ambivalent attitude object, but it also allows them to circumvent ensuing experiences of dissonance because they will not commit to a decision after all.Footnote4 In a similar vein, people use emotion-focused coping to deal with discomfort before a conflicted decision, affecting how they experience dissonance after that decision. Specifically, when having to make a conflicted decision, people cope with their discomfort by changing the accessibility of certain attitude elements (Fishbach et al., Citation2010), trivialising the importance of these attitude elements for a decision (cf. Simon et al., Citation1995), or obviating their responsibility for the whole decision (van Harreveld, van der Pligt, et al., Citation2009). We propose that these strategies allow people not only to make decisions and commit to an attitude-inconsistent behaviour, but additionally avert the experience of dissonant discomfort and corresponding negative emotions: Through emotion-focused coping with felt ambivalence, people will thus experience less conflict after the decision because fewer evaluations are relevant or accessible that might be inconsistent with the decisional commitment.

When people use problem-focused coping in response to felt ambivalence before a decision, this may also affect how they experience dissonance after the decision. By self-persuasion and information seeking (Maio & Thomas, Citation2007; Nordgren et al., Citation2006; Sawicki et al., Citation2013), people may change the evaluations that are inconsistent with their commitment. For instance, it has been shown in free-choice paradigms that people engage in biased information processing in favour of a preferred option even before committing to it (Mills, Citation1965, Citation1999; Mills & Jellison, Citation1968), presumably to resolve their inconsistent evaluations (van Harreveld, van der Pligt, et al., Citation2009). We propose that this will not only resolve ambivalence before making the decision but also dissonance and the necessity to spread evaluations after the decision (Brehm, Citation1956). Problem-focused coping strategies might thus help deal with ambivalence while making the decision and reduce or prevent the dissonance after making decisions because it pre-emptively changes attitudes that might conflict with people’s commitments.

Similarly, zooming out from a singular course of decision-making, dissonance-induced coping may affect how people experience ambivalence in subsequent decisions, depending on whether people use emotion or problem-focused coping. Specifically, we argue that problem-focused coping after a decision affects how people experience ambivalence in future decisions. In fact, dissonance-induced coping often addresses people’s attitudes, intending to align the inconsistent attitude with the commitment. These problem-focused coping efforts in response to dissonance might make people’s attitudes more or less ambivalent because dissonance-induced attitude change may often be durable over months (Janis & Mann, Citation1965; Sénémeaud & Somat, Citation2009; but for less durable attitude change, see; Festinger, Citation1964; Pauer, Rutjens, et al., Citation2024). In specific, we propose that the direction of the effects depends on people’s initial attitude: If people held an ambivalent attitude about a behaviour before committing to it, problem-focused coping might align the attitude with the commitment via a spreading of evaluations, leading to a more univalent attitude. Although less prevalent, if people held a univalent attitude before committing to an attitude-inconsistent behaviour, their attitude might become more ambivalent as a consequence of accommodating the dissonant behaviour. Thereby, problem-focused coping after a decision may affect the probability and intensity to which people experience ambivalence in the context of a future decision. For instance, if people’s evaluations effectively spread after they have decided within a free-choice paradigm to deal with dissonance via problem-focused coping (cf. Brehm, Citation1956), they will not re-experience the ambivalence when having to make a similar choice in the future (cf. Mills, Citation1965; Mills & Jellison, Citation1968). Emotion-focused coping, however, is unlikely to change future conflict because it does not change the attitudinal basis of the conflict but only the accessibility of the conflict. That is, the discomforting conflict will more likely resurface in subsequent decisions when inconsistent evaluations become accessible again. Thus, we argue that problem-focused coping (rather than emotion-focused coping) with dissonance changes how people experience felt ambivalence in future decisions due to its capacity to modify attitudes via a spreading of evaluations.

Conflict recurrence and resolution

While the various coping strategies and their interactions enable people to make and stick with conflicted decisions in the short run, we contend that people often resolve cognitive conflict only over prolonged time periods. In this section, we delineate the different avenues that determine how people experience, regulate, and ultimately resolve conflict in the long-term. We first argue that conflict may frequently recur, which motivates people to reconcile the conflict origins. Next, we posit that people typically resolve conflict incrementally via a spreading of evaluations resulting from repeated problem-focused coping. Thirdly, we discuss the frequency distributions of decisions as a boundary condition for these effects. Finally, we outline why conflict either persists or dissolves.

Longitudinal studies reveal that felt ambivalence can be relatively stable over several months, if not even years (Finkhäuser et al., Citation2024; Keller & Siegrist, Citation2015). This aligns with a set of studies (Pauer et al., Citation2023), showing that people perceive felt ambivalence to frequently recur over prolonged periods for many attitude objects. Crucially, people adjust their coping strategies to the recurrence of these ambivalent choices because recurrence perceptions of aversive conflict motivate more effortful problem-focused coping (Pauer et al., Citation2023). A similar pattern of findings was found in a large-scale experience-sampling study that tracked the recurrence of cognitive conflict after making dissonant commitments (Pauer, Rutjens, et al., Citation2024). Thus, when conflicts repeatedly reoccur over time, people attempt to effectively resolve the conflict via problem-focused coping that facilitates future decision-making via the spreading of evaluations. Thereby, the recurrence-induced motivation for problem-focused coping with ambivalence and dissonance may enable people to gradually change their attitudes and help them form univalent attitudes.

The likelihood and magnitude with which people experience ambivalence and dissonance when making decisions thus depend on the effectiveness of the employed problem-focused coping strategies: If people change either their negative or positive evaluations fully through problem-focused coping with felt ambivalence or dissonance, they might not (re-)experience subsequent conflicts. However, problem-focused coping typically may lead people to adjust their attitudes only slightly, just enough to tip the balance and jump off the fence (van Harreveld, van der Pligt, et al., Citation2009). We therefore propose that it is unlikely that people change their attitudes drastically via problem-focused coping; instead, we contend that such coping often gradually reduces the extent to which they (re-)experience conflict. Ambivalence- and dissonance-induced problem-focused coping before and after decisions may thus often lead to slight changes in attitudes, decreasing the likelihood and magnitude of experiencing conflict in ensuing decisions.

The use and effectiveness of problem-focused coping, however, might vary as a function of frequency distributions of decisions. While we assume that coping with frequently recurring conflicted decisions (such as food choices or smoking) motivates problem-focused coping (Pauer et al., Citation2023), the outcome of such problem-focused coping depends on the frequency of the number of (both conflicted and unconflicted) decisions. When people engage in problem-focused coping in the context of infrequently recurring decisions (such as voting for a politician), this entails a propensity for particularly pronounced attitudinal change. This is because infrequently recurring decisions preclude perceived opportunities to make up for a choice and may increase anticipated regret, such that people may feel particularly motivated to increase the quality of their choice before making a singular decision (cf. Itzchakov & van Harreveld, Citation2018). Likewise, if the conflict remains unresolved after the decision, we argue that people’s dissonant commitment is stronger within such infrequent and less reversible decisions (cf. Kiesler & Sakumura, Citation1966), leading to greater attitudinal changes in line with the commitment (cf. Bullens et al., Citation2013; Frey et al., Citation1984). This way, people might ultimately resolve conflict over time, not only within frequent but also infrequent decisions.

While problem-focused coping could help to resolve conflict over time, it may also explain how conflict manifests. Specifically, problem-focused coping can have heterogeneous effects on people’s attitudes if they fluctuate in their decisions about an attitude object and/or when they back down from their commitment. In fact, people do not always make the same choice within repeated decisions based on an ambivalent attitude (Conner & Armitage, Citation2008; Conner et al., Citation2021), and evaluative spreads that result from repeated problem-focused coping can cancel each other out across time. For example, suppose people seek information in support of one stance during an ambivalent choice. In that case, they may (perhaps even unintentionally) reverse the corresponding attitude change in a subsequent situation by seeking information that opposes that stance but supports another aspect of the ambivalent attitude. In a similar vein, dissonance-induced problem-focused coping may result in changes in commitment based on counterfactual thinking, and the resulting attitude changes might counteract previous attitude changes that helped people make the commitment in the first place. While such fluctuations facilitate navigating conflict within a singular decision effectively, they could hamper reconciling the underlying inconsistency and thereby give rise to re-experiencing the conflict in the future. This explains why conflict can be quite pervasive and frequently reoccurring (Finkhäuser et al., Citation2024; Pauer et al., Citation2023; Pauer, Rutjens, et al., Citation2024) even though people try to resolve not only the discomfort but also its attitudinal origin. Thereby, the AC/DC model delineates the cyclical dynamics of how cognitive conflict resolves or persists (see ).

A case study of the AC/DC model: meat-related cognitive conflict

To illustrate the processes in the AC/DC model, we outline its assumptions step-by-step by using meat consumption as a case example (see also for a chronological overview). Meat is a prime example of an ambivalent attitude object because many people evaluate meat positively and negatively at the same time (Rozin, Citation2007; Ruby et al., Citation2016). Positive evaluations involve, for instance, the taste and social traditions revolving around meat, while negative evaluations involve, for example, the detrimental consequences of meat production for animal welfare, human health, or the environment (Buttlar et al., Citation2023). Thus, meat consumption has become a prime example for studying cognitive conflict (Bastian, Citation2019; Bastian & Loughnan, Citation2017). In the following, we outline the central processes underlying the AC/DC model by describing a potential decision situation about eating meat, citing converging evidence from this field of research (Gradidge et al., Citation2021; Rosenfeld, Citation2018; Ruby, Citation2012).

Returning to the example from the introduction of Alex, who has an (ambivalent) attitude about eating meat, including positive and negative evaluations (see pre-decision panel of ). When going to a restaurant and opening the menu, Alex faces the imminent decision of what to eat. After scanning every dish on the menu, Alex wonders whether to get the steak, whereby the positive and negative evaluations underlying the ambivalent attitude about meat become accessible (Pauer, Rutjens, et al., Citation2024). Specifically, it comes to Alex’s mind that meat is tasty and that animals are harmed and slaughtered to produce meat (Buttlar et al., Citation2023). Consequently, Alex experiences felt ambivalence about ordering the steak, feeling torn about the decision to eat it, which may include uncertainty and the anticipation of regret about making a potentially bad decision (Buttlar et al., Citation2023; Pauer et al., Citation2022).

To cope with this aversive felt ambivalence, Alex can use emotion- or problem-focused coping. In fact, delaying the decision about what to order, going through the menu over and over (Ongaro et al., Citation2024) can be a means to avert the conflict; at some point, though, the waiter arrives, and a decision has to be made. At this point, Alex might cope with the ambivalence-induced discomfort using emotion-focused coping (van Harreveld, van der Pligt, et al., Citation2009), for example, by obviating the responsibility for the decision and blaming other people for the harm inflicted on animals (Buttlar & Walther, Citation2019; Rothgerber et al., Citation2022). Further, problem-focused coping might allow for a change in the ambivalent attitude underlying the felt ambivalence. For instance, Alex could think of or downplay certain evaluations to come to a more univalent attitude via a spreading of evaluations (e.g., thinking about the positive evaluations of meat’s taste and social benefits while downplaying the negative evaluations about animal welfare, environmental, or health issues related to eating meat or vice versa; cf. Buttlar, Pauer, Scherrer, et al., Citation2024). Thus, Alex could facilitate decision-making by dealing with either the discomfort or the attitudinal roots of the felt ambivalence.

After making the decision (see post-decision panel of ), the resulting commitment might lead to the experience dissonance if the outcome of the food choice opposes parts of Alex’s attitudes (Buttlar & Pauer, Citation2024). This dissonance might be especially intense if the decision involves eating the steak (Bastian et al., Citation2011; Loughnan et al., Citation2010; Pauer, Rutjens, et al., Citation2024) because negative evaluations of meat are often associated with moral considerations (Bastian & Loughnan, Citation2017; Buttlar & Pauer, Citation2024; Rothgerber, Citation2020). After making the order, Alex, therefore, experiences dissonant discomfort, including aversive arousal, which might involve a variety of negative emotions, including regret, guilt, anger, or anxiety (Bastian et al., Citation2011; Loughnan et al., Citation2010).

To cope with the dissonance after the decision, Alex could engage in the same toolbox of emotion- and problem-focused coping strategies that helped to make a decision: Emotion-focused coping, could for instance take place by derogating people who eschew meat (De Groeve & Rosenfeld, Citation2021; Minson & Monin, Citation2012) or denying the responsibility based on the downregulation of choice perceptions (Pauer, Rutjens, et al., Citation2024) and expressions of moral outrage against others (Rothgerber et al., Citation2022). Alex could also use problem-focused coping when experiencing meat-related dissonance to adapt the attitudes towards eating meat, for instance, by avoiding information about meat’s negative sides (Leach et al., Citation2020, Citation2022) or by attributing less emotional and mental capacities to animals (Bastian et al., Citation2011; Buttlar, Rothe, et al., Citation2021; Loughnan et al., Citation2010). To deal with meat-related dissonance after the decision, Alex can thus again use emotion- or problem-focused coping.

Crucially, Alex does not necessarily experience dissonance after making an ambivalent choice. On the one hand, emotion-focused coping that may have helped dealing with the ambivalence-induced discomfort can carry over from prior to after a decision. For instance, if Alex already situationally denied the responsibility for the choice outcome before making the decision (Pauer, Rutjens, et al., Citation2024; Rothgerber et al., Citation2022), Alex may experience less or no dissonance after the decision because of the absence of a voluntary commitment (Pauer, Rutjens, et al., Citation2024). On the other hand, problem-focused coping before the decision may help align the relevant attitudes with a subsequent commitment to eating meat. For instance, if downregulating the negative evaluations of eating meat through self-persuasion has led to the belief that animals were not harmed for meat production (Buttlar, Rothe, et al., Citation2021), Alex might circumvent or reduce experiencing dissonance after committing to eating meat. This is because the attitude becomes consistent with the commitment. Ambivalence-induced emotion- and problem-focused coping leading up to the decision to eat meat may thus shape experiences of meat-related dissonance after the decision.

While these coping strategies help Alex to come to a decision and stick to it, problem-focused coping might also affect how conflicts are experienced in future decisions due to its effect on attitudes (Buttlar, Pauer, Ruby, et al., Citation2024; Pauer et al., Citation2022, Citation2023). For instance, if Alex resolved conflict towards meat before or after the decision by attributing less mental and emotional capacities to animals, positive and negative evaluations about eating meat might spread (Buttlar, Rothe, et al., Citation2021). Thus, if Alex decides to (not) eat meat consistently in the face of conflict, such spreading of evaluations will gradually help to form a more univalent attitude with every decision. However, if Alex is volatile in these decisions, eating meat on some occasions and eschewing it on others, this might reinforce the ambivalent attitude because the coping processes have contradicting effects on the evaluations. This way, Alex might develop a rather univalent attitude and experience little conflict, becoming either a convicted vegetarian or omnivore (Buttlar, Pauer, Ruby, et al., Citation2024; Finkhäuser et al., Citation2024); however, Alex might also reinforce the ambivalent attitude and chronically experience conflict about eating meat (Buttlar, Pauer, Ruby, et al., Citation2024; Pauer et al., Citation2022).

Constraints on generalizability

In line with the ideas of Leon Festinger (Citation1957), we contend that people’s efforts to re-establish cognitive consistency in decision situations, such as about eating meat, are rather universal. In fact, cognitive dissonance processes, such as the spreading of alternatives, have been found in children and even animals (Egan et al., Citation2007). Unfortunately, research on cognitive conflict has typically been conducted by researchers at universities from the Global North. This oftentimes involves the recruitment of participants from so-called WEIRD populations (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, Democratic; Henrich et al., Citation2010). Notable exceptions to this bias in the literature show that ambivalence and dissonance are experienced across cultures, although the experience and reduction of conflict seem to be moderated by demographics such as people’s culture (e.g., Heine & Lehman, Citation1997; Hoshino-Browne et al., Citation2005; Kitayama et al., Citation2004; Ng et al., Citation2012; for an overview of the literature on cross-cultural research see; Gawronski, Citation2012). For instance, people from Eastern cultures may tolerate contradictions such as ambivalence more due to their tradition of dialectical thinking than people from Western cultures (Hamamura et al., Citation2008; Peng & Nisbett, Citation1999). While this suggests that people experience cognitive conflict differently, this refers to the extent to which conflict is experienced and how conflict is resolved rather than whether conflict is experienced at all within decision-making (Gawronski, Citation2012). This suggests that the AC/DC model might be relatively generalisable, although moderators can shape people’s experiences of conflict and the ways they cope with it before and after decisions (see a more general discussion of the boundary conditions and especially on the implications for conflict outside of the decision-making context in the general discussion).

General discussion

Research on cognitive conflict has been highly influential within and beyond social psychology (Cooper, Citation2007; Gawronski, Citation2012). Nevertheless, research on two classical kinds of conflict – ambivalence and dissonance – have thus far formed largely separate lines of research, which have been applied and discussed almost independently (McGregor et al., Citation2019; Newby-Clark et al., Citation2002). While both conflicts fall under Festinger’s original conceptualisation of cognitive dissonance (Citation1957), we draw on the common notion that dissonance reflects a post-decisional conflict, while ambivalence reflects a pre-decisional conflict (Dalege et al., Citation2018; de Liver et al., Citation2007; van Harreveld, van der Pligt, et al., Citation2009). By reviewing the empirical research on ambivalence and dissonance, we argue that ambivalent and dissonant conflicts differ in terms of their cognitive and emotional manifestations as well as the flexibility of available coping strategies. Based on this review, we propose the integrative Model of Ambivalent Choice and Dissonant Commitment (AC/DC model) to describe the interrelations between these pre- and post-decisional conflicts that arise due to their succession in decision-making.

The AC/DC model posits that ambivalent attitudes increase the likelihood of experiencing ambivalent and dissonant conflicts. That is, when ambivalent attitudes (involving both positive and negative evaluations) become accessible during decision-making (an ambivalent choice), people experience aversive felt ambivalence, including negative emotions such as anticipated regret and uncertainty; and when an attitude-inconsistent commitment becomes accessible after making a decision (a dissonant commitment), people experience aversive dissonance, including negative emotions such as regret, shame, guilt, or anger. Thus, both conflicts are rooted in people’s attitudes, but because they occur at different stages of decision-making, they involve different cognitions and emotions.

Nonetheless, people react to the two conflicts using a similar toolbox of coping strategies, either emotion-focused or problem-focused coping. Via these strategies, ambivalence and dissonance mutually influence each other. Coping with felt ambivalence before decisions affects how dissonance is experienced afterwards, and coping with dissonance can carry over to future decision-making. However, the intricate interplay between ambivalence and dissonance hinges on the employed coping strategies before and after decisions. By outlining these interrelations, the AC/DC model helps to understand how people can navigate cognitive conflicts in the short term and resolve them in the long term.

Theoretical considerations

Conflict by default

While making ambivalent choices, many decisions can be postponed indefinitely (e.g., buying a new sweater) to avert conflicts; yet, other decisions are time-sensitive and lead to commitments by default. For instance, people who are facing an ambivalent choice about signing up for an exam are constrained in their decision by the registration deadline. In such a situation, decision delay might help people cope with felt ambivalence arising from their simultaneously accessible evaluations about the exam (e.g., “the exam is hard, but it helps to make a career”). However, due to the time-sensitive nature of that decision, people may commit to a course of action even when delaying the decision: By the time the registration deadline passes, they have committed to not writing the exam even without an active decision. Similar to making an active decision, this commitment can lead to dissonance (unless people have resolved inconsistent evaluation that opposes the commitment in the meantime, e.g., “the exam is not really necessary to make a career”). This way, dissonance may result even from decision delays.

Crucially, not only decisions but attitudes themselves can be time-sensitive, such as attitudes towards food. For instance, Buttlar, Löwenstein, et al. (Citation2021) have shown that food past its best-before date leads to more negative evaluations and felt ambivalence compared to food that has not expired. Based on these results, the authors argue that delaying decisions might not only lead to increased ambivalence but resolve ambivalence over time when attitudes change. That is, when people wait long enough, their negative evaluations might increase even further while their positive evaluations decrease. Due to such time-dependent evaluative spreads, people might develop a univalent attitude when delaying decisions. Buttlar, Löwenstein, et al. (Citation2021) thus posited that this is why people often wait before disposing of sub-optimal food until the food is definitely spoilt (Evans, Citation2012): Decision delay allows them to make unconflicted decisions. Moreover, in such situations, people practically commit to discarding the food without making an actual decision. Due to the evaluative spreads, however, we argue that they will not experience dissonance because their attitudes have changed in the meantime, being consistent with their commitment to dispose of the food. In fact, people who delay their decisions on suboptimal food experience less guilt when delaying their decisions to discard food (Evans, Citation2012). Delaying time-sensitive decisions might thus lead to conflict by default, but it could also resolve conflict if the attitudes relevant to the decisions are time-sensitive as well.

Conflict between alternatives

The AC/DC model focuses mostly on intra-attitudinal ambivalence arising from the accessibility of positive and negative evaluations regarding one attitude object. However, similar kinds of conflict can be distinguished. For example, people cannot only be torn in their decision to do or not do something based on one attitude, but they can also experience conflict between two or more alternatives. This becomes apparent in classic research on free-choice paradigms in which participants experience dissonance when making difficult choices between two equally attractive (or unattractive) alternatives (e.g., Brehm, Citation1956; Mills, Citation1965). Even though these situations are more complex, we argue that they are comparable to decisions with intra-attitudinal ambivalence if the alternatives are similarly (un-)attractive: People will experience uncertainty and may anticipate regret about potentially making the wrong decision (see van Harreveld, van der Pligt, et al., Citation2009; Zeelenberg, Citation1999 for similar arguments).

To no surprise, people seek information for the alternative that they slightly favour and avoid information for the other alternative prior to a commitment in free-choice paradigms (Mills, Citation1965; Mills & Jellison, Citation1968), similar to people who seek and avoid positive or negative information to reduce intra-attitudinal ambivalence (Clark et al., Citation2008; Itzchakov & van Harreveld, Citation2018). So far, information seeking and avoidance prior to choosing between two or more alternatives in free-choice paradigms have been suggested to help people avoid dissonance after making decisions (Brehm, Citation2007; Mills, Citation1999). The AC/DC model offers a new perspective on these findings: While information seeking or avoidance may indeed prevent people from experiencing dissonance, these tendencies seem to be driven rather by an ambivalent state prior to a commitment where seeking and avoiding information will also have downstream consequences and avert dissonance. Thereby, the AC/DC model confers that dissonance may indeed be avoided depending on the success of coping efforts prior to a decision. However, we posit that coping prior to decisions is primarily motivated by felt ambivalence rather than anticipatory dissonance.

Crucially, when being conflicted between alternatives, a spreading of evaluations might occur not only for the chosen option but also for the non-chosen option, leading to the commonly known spreading of alternatives effect (Harmon-Jones & Mills, Citation2019). For instance, when being torn between selecting one of two dishes from a menu, people might not only have to commit to eating the steak, but they might also have to commit to not eating the plant-based burger. When such a conflict between alternatives occurs, people usually cope by evaluating the chosen option (the steak) more positively while evaluating the non-chosen option (the burger) more negatively (Brehm, Citation1956). We thus argue that a spreading of evaluations might occur not only for one attitude object but for multiple attitude objects, apparent in a spreading of alternatives. In this vein, it might also be noted that evaluative spreads might generalise in the form of lateralised attitude change (Glaser et al., Citation2015): When people commit to eating the steak, they might not only evaluate this specific dish more positively but also meat dishes in general; similarly, they might evaluate plant-based dishes more generally negatively after committing not to eat the plant-based burger. This serves the purpose of retaining consistency among similar attitude objects (Glaser et al., Citation2015), arguably promoting consistency within decisions over time (Cialdini et al., Citation1995). We, therefore, believe that studying decision situations in which people have two or more alternatives may further promote our understanding of the interrelation between ambivalence and dissonance within decision-making and the generalisation of (conflict-induced) attitude changes.

Conflict outside of the decision-making context

While the AC/DC model centres around decision-making, we acknowledge that conflict also arises outside the decision situations highlighted in our model. In fact, people may not only experience dissonance when committing within (more or less frequent) decision situations, but our model indicates that commitments can persist after having made the decision. Therefore, we posit that dissonance can be elicited even when people merely become aware of such a persistent commitment towards an attitude-inconsistent behaviour. For example, Festinger’s case study (Citation1956) discussed the consequences of a long-standing commitment to a refuted belief in the context of an apocalyptic cult (similar to conspiracy beliefs about the corona-related seizure of democracy). A second example concerns people who have repeatedly made the decision to eat meat throughout their lives, such that they can experience meat-related dissonance when they are reminded of their commitment to a meat-based diet by the presence of vegetarians (Rothgerber, Citation2014). This implies that people may not only experience dissonance when they make acute decisions but also due to commitments long after decisions have been made.