Simplistic binary divisions between “the disabled” and “everyone else” remain surprisingly normalized within contemporary architectural education and practice. We are taught to design buildings for their users, and only afterward to retrofit for some Others—the disabled—through the application of banal technical and legal guidance.1 While other identities are at least explored to some extent in architectural discourse and practice, disability as a concept and disabled people as a constituency continue to be assumed as completely separate from social or cultural politics—as merely a catalog of unproblematic functional categories (e.g., deaf, blind, and wheelchair user). Unlike gender, race, or sexuality then—and the feminist, postcolonial, and queer studies that underpin associated scholarship and debate—it seems that we assume “disability” to be unable to bring any kind of criticality or creativity to the discipline of architecture.

But this is not because critical thinking about disability, space, and architecture is lacking. Disability studies, disability arts, and disability activism have long been critiquing assumptions about what kinds of “bodyminds”2 matter: who gets valued and who gets marginalized, opening up the critical and creative investigation of disability and ability in order to challenge and remake conventional access and inclusion practices. Rather than being a mere technical problem for architecture, thinking and “doing” dis/ability turns out to be a creative generator for design, a powerful critique of what is assumed “normal,” a vital means for troubling everyday design assumptions about space and its occupancy, and an enabling mechanism toward new collective and emergent forms of social, spatial, and material equity.

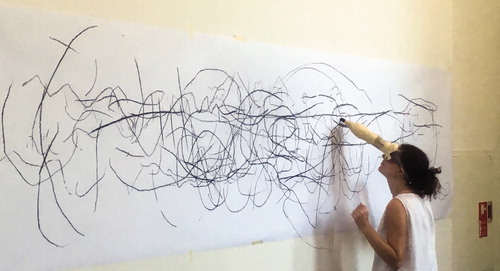

Figure 1. “The Alterator” project, created by disabled artist David Dixon, asks students to draw through a bodily difference: in collaboration with Masashi Kajita and students at KADK Copenhagen, September 2018. (Photograph by author.)

The DisOrdinary Architecture Project, which I cofounded with disabled artist Zoe Partington in 2008, is a platform bringing together disabled artists and built environment students, educators, and practitioners to explore and experiment in these spaces. Our mission is to promote activity that develops and captures models of new practice for the built environment, led by the creativity and experiences of disabled artists. DisOrdinary Architecture has a committed group of about fifteen disabled artists, together with many involved in particular projects and an increasing support network of built environment students, educators, and professionals. Our intention is nothing less than to orchestrate a complete cultural shift. We want to create a world that reimagines disability, access, and inclusion not as an “add-on” to existing disciplinary practices but as a means to remake those practices. Below, then, is our basic four-point call to action. This is aimed at “normies” and “neuro-typicals”—as the token nondisabled person and only architect in DisOrdinary Architecture, I want to underline how much we, not disabled people, are the problem.

1. Challenge the normative: get to a place where it is no longer okay to design for “normal” and then add-on (retrofit) adjustments for Others. We live in a world where individual mobility, autonomy, and personal competence are both highly valued and seen as ordinary and “natural.” People who are less than fully mobile, are interdependent, or seem less capable are perceived as “difficult” because they don’t fit with this world and are assumed to need “special” adaptations to it. But what if we didn’t design this way—privileging the already able-bodied—but instead imagined spaces that create multiple forms of support for our many different ways of being in the world? How might design change if we recognize, value, and learn from the enormous variety of human requirements and experiences?

Learning to value the richness of our neuro- and biodiversity through collaboration with creative disabled people turns out to be a deeply enjoyable, refreshing, and thought-provoking activity. This is because engaging with disability, difference, and inclusion is inherently expansive and intersectional; it is about opening things up rather than what technical guidance does, which is close things down.

2. Change the language … and the attitudes, design cultures, methods, forms of representation, etc. DisOrdinary Architecture often explores dis/ability and its intersections with other identities through ideas of “fitting and misfitting.”3 This enables a move away from simplistic binary oppositions (abled/disabled, male/female, white/black, straight/gay, young/old) to a more relational framing4 that can investigate who is enabled or disabled in the various interplays between specific spaces, encounters, and social norms. Unraveling experiences of architectural misfitting across built, conceptual, and disciplinary spaces can help reveal shared patterns of invisibility and marginalization, as well as differences and tensions in how othering is made concrete.

Working with disabled artists in architectural education and practice over many years, we have created various strategies, methods, and projects that challenge architecture’s “justificatory narratives” and its ability to keep disabled people as Other.5 Informed by their own creative practices, artists working for DisOrdinary have developed forms of embodied mapping, narratives of difference, creative breaching, experimental provocations, and design interventions that offer new models of working across education and practice.6

Figure 2. Characters workshop with disabled artist Zoe Partington. Students alter their bodies in different ways to map and engage with diverse experiences and perceptions of built space: in collaboration with Anne-Marie Broudehoux and students at L’Université du Québec à Montréal (UQAM), Montreal, May 2019. (Photograph by author.)

3. Check your abled privilege; be an ally. One of the privileges of ableism is to misunderstand disabled people’s diverse lives and experiences by failing to listen or pay attention to (but rather speaking for) “them.” Another is that nondisabled people can assume their own bodies are unproblematic and ordinary, therefore not noticing that built space mainly offers them a smooth rather than a misfitting experience—what Tanya Titchkosky called “speaking of normal bodies as movement and metaphor maps them as if they are a natural possession, as if they are not mapped at all.”7

A third privilege is the assumption that architects are not disabled (or if disabled, then automatically become access consultants). Here the binary divide is maintained—often apologetically (“Sorry, our offices are inaccessible”). Thus, disabled people’s expertise and creativity are discounted or frustrated. Because DisOrdinary Architecture offers a safe space for disclosure, in a way that mainstream architecture education and practice does not, we have met many people with impairments already within the discipline.8 This is a potentially powerful force for change that needs to be recognized and supported, not othered.

4. Work with disabled and other marginalized people toward collective social, spatial, and material justice. Disability studies scholars and activists, such as Margaret Price, Aimi Hamraie, and the Disability Visibility Project, start by framing dis/ability as relational, situated, complex, and contradictory.9 Rather than the one-size-fits-all solutions of access design guidance, they look to crowdsourcing and other forms of emergent collective action for access and inclusion that accepts contradictory variety and difference but still aims for positive social, spatial, and material change. Engaging with these approaches is vital for architecture. It suggests approaches that go beyond banal identity categories—whether within “disability” or across the usual lists of gender, race, class, etc.—toward creating layered, always unfinished, forms of knowledge about our multiple (and multimodal) preferences for negotiating built space. Generating and listening to multiple voices does not provide answers but does inform creative decision-making in a way that aims not to add-on access and inclusion but to call for social, spatial, and material justice.

Consider engaging with the important and creative work of disability studies scholars, activists, and artists. Disability Arts in the UK, for example, is a vibrant (if underfunded) sector. Find out about diverse artists’ work through, for example, Disability Arts Online, Shape Arts, and the Arts Council’s Unlimited program.

Notes

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jos Boys

Jos Boys is trained in architecture and is course director for MSc Learning Environments at The Bartlett, University College London. She is cofounder of The DisOrdinary Architecture Project, author of Doing Disability Differently: An Alternative Handbook on Architecture, Dis/Ability, and Designing for Everyday Life (Routledge, 2014) and editor of Disability, Space, Architecture: A Reader (Routledge, 2017).

Notes

1 Jay Dolmage, “Mapping Composition: Inviting Disability in the Front Door,” in Disability and the Teaching of Writing: A Critical Sourcebook, ed. C. Lewiecki-Willson and B. Brueggeman, with J. Dolmage (Boston: Bedford/St Martin’s, 2008), 14–28.

2 Margaret Price, “The Bodymind Problem and the Possibilities of Pain,” Hypatia 30, no. 1 (November 2014): 268–84.

3 Rosemary Garland-Thomson, “Misfits: A Feminist Materialist Disability Concept,” Hypatia 26, no. 3 (Summer 2011): 591–609.

4 Alison Kafer, Feminist, Queer, Crip (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2013).

5 Tanya Titchkosky, “‘To Pee or Not to Pee?’ Ordinary Talk About Extraordinary Exclusions in a University Environment,” Canadian Journal of Sociology 33, no. 1 (March 2008): 33.

6 Examples can be seen in our Vimeo showcase: Tim Copsey, “The DisOrdinary Architecture Project: Doing Disability Differently in Architecture and the Built Environment,” Vimeo, video showcase, https://vimeo.com/showcase/4562223.

7 Tanya Titchkosky, “Cultural Maps: Which Way to Disability?,” in Disability/Postmodernity: Embodying Disability Theory, ed. M. Corker and T. Shakespeare (London: Continuum, 2002), 103.

8 Fae Kilburn, “Architecture Beyond Sight,” Disability Arts Online, August 6, 2019, https://disabilityarts.online/blog/fae-kilburn/architecture-beyond-sight/.

9 See Margaret Price, “Un/Shared Space: The Dilemma of Inclusive Architecture,” in Disability, Space, Architecture: A Reader, ed. Jos Boys (London: Routledge, 2017), 155–72; Aimi Hamraie, “Mapping Access: Digital Humanities, Disability Justice, and Sociospatial Practice,” American Quarterly 70, no. 3 (September 2018): 455–82; and Mia Mingus, Alice Wong, and Sandy Ho, “Access Is Love,” Disability Visibility Project, February 1, 2019, https://disabilityvisibilityproject.com/2019/02/01/access-is-love/.