Abstract

Underrepresented communities are overrepresented in correctional systems worldwide. In Hawaiʻi, Native Hawaiians represent a disproportionately high percentage of people in all levels of the criminal justice system. This chronic overrepresentation of Hawaiʻi’s indigenous community embodies systemic inequality, discrimination, racism, and colonialism across multiple institutions and generations. Our paper describes a cultural competence framework developed for the State of Hawaiʻi Department of Public Safety to address this injustice through the integration of cultural and indigenous values, knowledge, and practices to agency structure, processes, programs, and facilities. The project offers diverse, context-specific, decolonizing mechanisms designed to support systemic transformation.

In 2016, the State of Hawaiʻi drafted House Concurrent Resolution (HRC) No. 85, H.D.2, S.D.1, to establish a task force to make recommendations to the legislature on costs and best practices for the future design of corrections in Hawaiʻi. In December 2018, the HCR 85 Task Force submitted its final report, which recommended transitioning from a punitive to a rehabilitative correctional system, calling for a prison system based on Hawaiʻi’s core values.1 The task force recognized the significant overrepresentation of Native Hawaiians throughout the criminal justice system. While Native Hawaiians and part Hawaiians comprise approximately 20 percent of the general population, they make up nearly 40 percent of the correctional population. To address this, the task force recommended the state adopt a vision for corrections that draws from cultural practices that can restore harmony between an individual and their ʻohana (family), community, akua (spiritual realm), and ʻāina (land). In addition, they called for intrapersonal healing to successfully reintegrate paʻahao (prisoners) and break the intergenerational cycle of incarceration.2

Following up on the HCR 85 Task Force findings, the State of Hawaiʻi Department of Public Safety (DPS), partnered with the University of Hawaiʻi Community Design Center (UHCDC) to study new restorative correctional models that respond to social, cultural, ecological, and economic opportunities and impacts. UHCDC assembled a multi-departmental team of faculty, staff, and students from the School of Architecture, the College of Engineering, and the Social Science Research Institute at the University of Hawaiʻi to study waste, culture, and social enterprise. These comprise three components of a statewide strategic master plan being developed for DPS in partnership with a private architecture and engineering firm.

The work described in this paper focuses on the School of Architecture’s research component. The school contributed a cultural competence framework aimed at decolonizing the state’s correctional system, understanding operations, programs, and facilities as inseparable parts of a whole. The call for a transition from a carceral to cultural landscape invited a new approach to prison design.3 As the Native Hawaiian leader George Kanahele stated, “in the Hawaiian mind, a sense of place was inseparably linked with self-identity and self-esteem.”4 His words reinforce the critical role designers play as placemakers, especially with regard to the health and wellbeing of the Native Hawaiian community. This paper follows the development of the cultural competence framework, beginning with a brief introduction to corrections and decolonization, followed by a summary of teaching, outreach, and research efforts. Lastly, this paper describes a framework toolkit, which includes a process, resources, and set of strategies to support implementation. The framework and toolkit will be applied to three proof-of-concept designs for three separate facilities sites, still to be determined. This forthcoming design process will continue to reshape the framework and forward the continuous process of learning and engagement fundamental to cultural competence.

This study begins with the assumption that process and product are inextricable in the context of prisons and inequity, undertaking the task of transforming both. In Decolonizing Methodologies, Linda Tuhiwai Smith notes that decolonizing efforts focus primarily on cultural revitalization and the reorganization of political relations with the state.5 Her words emphasize the importance of understanding the relationship between new placemaking approaches and political transformation. Embracing the need to address both the community and state, our framework aims at a decolonizing design mechanism that works at both levels. In their review of research on prison architecture and design, Dominique Moran and Yvonne Jewkes argue for more work that scrutinizes and reflects on the design process itself rather than on designed spaces.6 Embracing this, the framework developed here considers both system and space, process and product.

Corrections and Decolonization

Indigenous peoples are overrepresented in criminal justice systems worldwide.7 Across the US, nineteen states reflect disproportionate percentages of indigenous peoples in their correctional populations.8 This rate of incarceration for indigenous peoples highlights the country’s ethical responsibility to address the ongoing consequences of US colonization. Indeed, the disparity between the current Western model for corrections and the indigenous model envisioned by the HCR 85 Task Force highlights both the challenge and opportunity for planners and designers working for the state’s postcolonial correctional system. Hawaiʻi’s statewide system houses twenty-seven thousand incarcerated citizens in four jails and four prisons, at a cost of $226 million per year. As mentioned, nearly 40 percent of these citizens are Native Hawaiian. As one of the most acute manifestations of continued colonization of Native Hawaiians, the correctional system presents a context in which decolonization, through principled design, might be of greatest benefit.9 There are two leading paths for correctional reform worldwide. Norway, Iceland, and Denmark lead the effort to “humanize” prisons; many countries have produced guidelines aimed at the “greening” of prisons or, in other words, minimizing the environmental impacts of prison facilities and capitalizing on green industry opportunities. These reforms aim to address equity. The movement to decolonize prisons also orients to diversity and the restoration of indigenous relationships that introduce context specific approaches to reform.10

Colonization in Hawaiʻi dates back to Western contact and the arrival of James Cook in 1778. In 1893, Hawaiian sovereignty ended when Queen Liliʻuokalani surrendered the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi at gunpoint to white sugar growers who proclaimed Hawaiʻi a US protectorate. In 1898, the US government annexed Hawaiʻi without a single Native Hawaiian vote, annexing 1.8 million acres of sovereign Hawaiian crown lands without compensation to the Hawaiian people. This colonization subjected the Native Hawaiian population to “massive depopulation, landlessness, christianization, economic and political marginalization, institutionalization in the military and prisons, poor health, and educational profiles, increasing diaspora.” 11 Colonization continues to shape contemporary Hawaiʻi, including—and especially—corrections.

Australia, a country with a similar history of colonization, offers a valuable precedent for our work. The West Kimberly Regional Prison (WKRP) in Western Australia was designed to specifically address the high incarceration rate of the Aboriginal population. The government established the Kimberley Aboriginal Reference Group, which guided and developed recommendations for the project. The facility is one of only a few in Australia with a combined design and operating philosophy. This philosophy recognizes the fundamental benefits of cultural responsibility; spiritual relationships with the land, sea, and waterways; kinship and family responsibilities; and community responsibilities.12 The government opened the prison in late 2012, with 120 males and thirty females located in twenty-two self-care units grouped according to family ties, language, and security levels. The first inspection in 2014 stated that WKRP met the needs of prisoners for culturally appropriate operational practices and procedures. Prisoners engaged in rehabilitative programs and safely expressed their culture.13

Teaching Approach

An academic design studio provided the opportunity to incubate ideas and methodologies about design and corrections in Hawaiʻi. In this case, the primary author of this paper taught a core fourth-year undergraduate design studio, ARCH 415. The studio brief asked students to develop “New Models for Corrections in Hawaiʻi” by identifying Hawaiʻi’s singular characteristics and cultures.

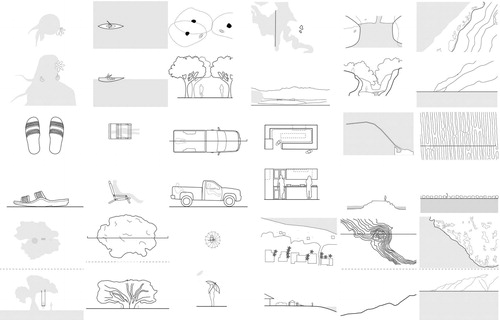

The studio began with an exercise that asked students to reflect on their own social and cultural identities and practices. The task initiated self-awareness, a process considered fundamental to building cultural competence in social work.14 Their first assignment referenced Christopher Alexander’s pattern languages to which the team returned to later when developing a toolkit of design strategies.15 Students produced diagrams of spaces and relationships that connected them to their place, describing elements of their own cultural landscape in plan and section at multiple scales: S, M, L, and XL. For example, students identified “wearing a flower above their ear,” “wearing slippers,” and “talking-story in the kitchen,” plus various spaces under trees, near the ocean, in the ocean, and overlooking valleys and ridgelines ().

Figure 1. Plan and section diagrams by ARCH 415 students Alexander Guillermo, Gladys Razos, Ivy Tejada, Charissa Yamada, and Kristyn Yamamotoya, depicting their cultural landscape elements at S, M, L, and XL scales.

The instructor challenged students to consider how these relationships might be integrated into correctional programs and facilities to maintain or establish similar positive attachments to place. The students then analyzed historical prison morphologies, humane prison models, and emerging prison programs.16 In parallel, the students gained firsthand experiences from visiting the Halawa Correctional Center (prison) and the Oʻahu Community Correctional Center (jail). They also benefited from constant dialogue with the chief planner and project engineer at DPS. The case studies, visits, stakeholder feedback, and needs assessments for three facility sites informed the design of eleven hybrid program models. These included a culinary institute, flower and tree farm, aquaculture center, aquaponics farm, coffee farm, masonry institute, recycling center, therapy community, arts and crafts academy, reforestation and woodworking camp, recycling center, and animal training center. One student identified a large wooded area on the Waiawa Correctional Facility site as an opportunity for a native reforestation program, replacing invasive species with native trees and repurposing the invasive wood into objects of value. Her project proposed small, open-air housing units that allow individuals to reside in the forest while assigned to the work camp ().

Research

Following the ARCH 415 class, the School of Architecture assembled a research team. To date, it has included two faculty members, one professional consultant, three research associates, ten student assistants from the School of Architecture, and one student from Hawaiian studies.17 Four of the students from the design studio joined the research team, allowing them to move from academic speculation to applied research. A brief literature review of the national standards and guidelines reshaping contemporary prison design yielded no evidence of any cultural components.18 This highlighted a clear gap in the industry discourse and an opportunity for the team to focus more intensely on a culturally integrative and indigenous-serving approach to corrections.

The team co-organized the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa 2018 Decolonizing Cities Symposium.19 As a convening of voices on local and global decolonizing practices—a very small niche in planning and design—the symposium played a critical role in situating our work. The keynote presenter, Māori architect and advocate Rau Hoskins, presented his work on the Te Aranga principles, a pioneering set of planning principles derived from a Māori worldview to enhance Māori presence, visibility, and participation in the design of physical environments.20 The full implementation of the Te Aranga principles illuminated a path for our project while local presenters helped to reveal emerging themes.

We further explored the symposium’s themes in one-hour talks with cultural experts, educators, and community leaders. Interviews began with discussions of cultural values and their relationship to design principles before moving to the visioning of a culturally competent design process, ending with a brainstorming session about cultural resources and community partnerships. We gave interviewees 11 × 17 in. sheets with prompts and diagrams to help visually frame and document the discussion. Students transcribed audio recordings, then they analyzed the transcriptions using an adapted version of a qualitative methodology derived from grounded theory.21 They identified codes such as cultural concepts, specific suggestions or advice, push-back or redefining of prompts, and open-ended questions raised by interviewee. One unusual code was talk story, the colloquial Hawaiian term used to describe the informal exchange of personal experience and anecdotes.

The second half of each interview examined how the department might implement the two Native Hawaiian models consistently referred to in HCR 85 Task Force reports: ho’oponopono (a practice of reconciliation) and puʻuhonua (place of refuge).22 The first, ho’oponopono, refers to a Native Hawaiian traditional and contemporary process that starts with a pule (prayer), problem identification, sharing of feelings, and a cooling off period, which alternates until forgiveness is given and entanglements removed, resulting in mutual release. At the end of the process, the entanglement is oki (cut off). The second model, puʻuhonua, refers to a sacred refuge established by the ruling aliʻi (chief). Historically, the refuge operated in conjunction with a heiau (place of worship), whose gods protected the place and that kahuna (priests) ran. A person who committed a crime could escape death if they made it to a place of refuge. Once inside, they could ask for a second chance at life. The kahuna would perform a ceremony of absolution, which would allow the person to return home, forgiven.

Framework

A key outcome for the research was the development of resources—frameworks, tools, and directives—that DPS could reference when requesting funds from legislators. DPS was not interested in passive research or a set of principles, instead asked for clear and fundable directives. In response, the team developed an overarching cultural competency framework that presents a set of goals with action items, specific funding requests, and examples of relevant implementations. These goals include “Align the agency,” “Partner with the community,” “Create equitable exchange and representation,” “Share cross-cultural knowledge,” “Promote holistic health,” and “Design for relationships.” They address the need for a new agency mission and vision, cultural-competency training for all agency employees, long-term community relationships for each facility, cultural-enterprise programs, and spaces for cultural practices. The team also produced a framework tool for each goal to help DPS navigate some of the barriers to implementation. This multipronged approach addresses DPS, its partners, knowledge, processes, programs, and design projects. diagrams the relationship between our process, goals, tools, and projected impacts.

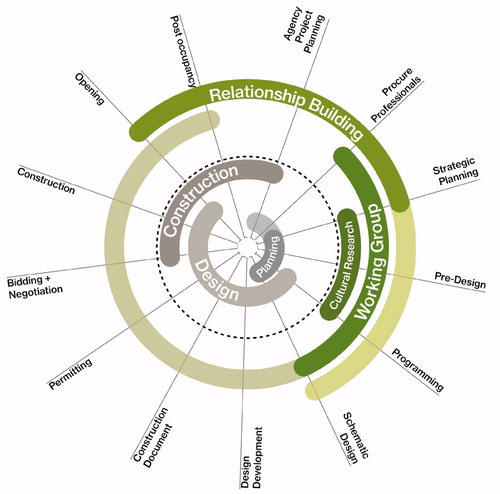

The first tool, a cultural design process for capital improvement projects (CIP), presents a decolonized planning and design process described collectively by our interviewees. The current CIP process includes planning, predesign, preliminary design, prefinal design, final design, permitting, and construction. By law, it includes a cultural impact assessment during the preplanning phase, and a State Historic Preservation Division review during permitting. However, these procedures are minimal and mostly administrative. As an alternative, the cultural design process shown in establishes a circular process, analogous to a lei, that integrates community-based relationship building, cultural research methods, community agency, and post occupancy evaluations. Each link supports continuous, cyclical, long-term learning.

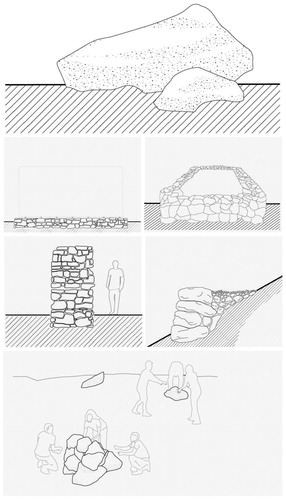

The second tool, a cultural design resource, provides a multicultural primer for planners and designers. This primer introduces cultural design to professionals in this specialized field, especially those not based in Hawaiʻi. The information is concise and aims at building cultural competence, facilitating self-awareness, expanding cultural knowledge, and providing a foundation for subsequent knowledge building. It features sections on cultural values (axiology), ways of knowing (epistemology), and ways of doing (methodology). Most importantly, we describe the indigenous research methods that access and activate place-based cultural knowledge. These include collections of moʻolelos—Native Hawaiian stories, narratives, and myths—that define a given place; historic maps that reveal moʻokūʻauhau or place genealogies; place names that describe historic characteristics of the site; in-depth site observation; and oral interviews or “talk stories,” especially with respected elders. The methodology section compiles indigenous approaches to the built environment at four scales: land planning and development, siting and orientation, building design, and interior design. Each page describes an indigenous methodology—for example, the use of pōhaku (rocks) in . The illustrations show the use of traditional stonework for kahua (foundations), hakahaka (free standing walls), lokoʻia (fishponds), and irrigation lining. The related text, which is not shown, notes the mana (divine power) in the pōhaku and its use for heiaus (places of worship) and ahu (shrines) to honor the gods; it offers brief takeaways and implementation ideas for further research.

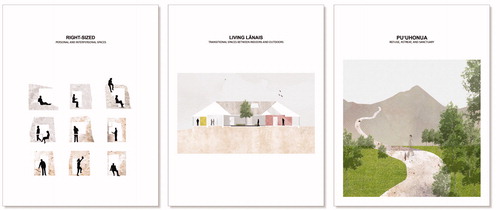

The third tool, a document titled “Designing for Pilina,” offers design strategies that focus on relationships critical to Native Hawaiian health and wellbeing.23 Like Christopher Alexander’s pattern language, these strategies explore how specific design choices help to build better relationships.24 The pilina (relationships) strategies shift our focus from people and their environments to people and their relationships. They also connect to models for Native Hawaiian health and wellbeing. Various sources diagram health as a set of concentric circles, with the kanaka (person) at the center, surrounded by ʻohana, ʻāina, and akua, articulating fundamental and nested attachments to family (children, parents, elders, and ancestors), nature, and the gods and spirits.25 We embraced these three essential components and developed sets of strategies to strengthen kanaka-ʻohana, kanaka-akua, and kanaka-‘āina relationships. Three examples are shown in . The ʻohana strategy (right-sized spaces) promotes spaces that allow for privacy, interpersonal exchange, and smaller group living. The ʻāina strategy (living lānais) optimizes transitional spaces between indoors and outdoors through wellness courtyards, deep lānais, and breezeways. The akua strategy (puʻuhonua) offers different approaches to providing refuge and retreat. These examples offer ideas to be discussed, vetted, and adapted for specific projects.

Figure 6. UHCDC, illustrations for three design strategies from the “Designing for Pilina” framework tool.

The ʻohana strategies aim at maintaining relationships within both immediate and extended families and the broader community. The ʻohana strategies start with the three pikos (navels): the piko poʻo or manawa at the head, which connects to the spiritual realm and ancestors; the piko waena at the navel, which connects to parents and a gut feeling; and the piko maʻi at the genitals, which connects to future generations. The cultural practitioners we interviewed talked about this triple piko concept as a way to assess their own initiatives and impacts. Our ʻohana strategies orient to this continuum of family relationships and to community-scale opportunities to build social capital, job readiness, and sociocultural enterprise pathways that likewise improve outcomes after release.26

The health and life of the Native Hawaiian people are also intrinsically tied to their relationship to the ʻāina, commonly understood as “the land” but more deeply as “that which feeds us.” The ʻāina is considered the older sibling of the first human, establishing a genealogical kinship and familial interdependency between people and the land. This aligns with the tenets of biophilic design, which see the connection between humans and the environment as central to health and wellbeing. The team overlaid indigenous ways of relating to the land and biophilic research to produce the ʻāina strategies.27 These include strategies for connecting humans to nature through visual and physical contact, air flow, water, dynamic and diffuse natural lighting, patterns, forms, rhythms, materials, perspectives, and activities that care for the environment. The team made sure to colloquialize each strategy, illustration, and supporting image to create a Hawaiʻi-serving design tool.

Our framework establishes an approach that allows us to integrate cultural values, knowledge, wisdom, and practices into the contemporary design of correctional facilities in Hawaiʻi. The design studio, strategic framework, and toolkit promote ethical design for all people based on values of equity, diversity, and human rights.28 By designing for the dynamic relations between correctional facilities and the Native Hawaiian community, we believe that we have developed an approach to making better environments for all.

In view of the work that still needs to be done to restore Native Hawaiian health and wellbeing, both in and out of corrections, allow us to end with a discussion of the akua. The akua, or spiritual realm, includes two primary belief structures: the ʻIhi Kapu and the Huikala. In Native Hawaiian culture, these two structures establish a sense of self, both individually and socially.29 In his article about cultural trauma, Hawaiian spirituality, and contemporary health, Bud Pomaikaʻi Cook and colleagues positioned the stripping away of this Native Hawaiian spiritual structure and cosmology as one factor leading to historical trauma response (HTR) and cultural wounding.30 He advocates for new healthcare practices that recognize these cultural violations, emphasizing the need for cultural healing that encompasses mental, spiritual, and physical wellbeing.31 He notes that this healing will require deep, sincere, culturally sensitive learning and individually focused efforts that must span several generations. The akua strategies not mentioned before represent the spiritual markers, spaces of worship, rituals, and healing practices that help to connect the physical and spiritual realms. But more importantly, the “Designing for Pilina” strategies align with Cook’s recommendations to healthcare practitioners, understanding cultural healing as equally relevant to those who design for health.

Our process pilots one path among others that embrace a broad design approach to helping Others who fall into the custody of our agencies—detention, corrections, foster care, welfare, and public housing. Working for corrections required our ability to reconcile the needs of both the top and bottom, reducing the disconnection between the two. To address the system, we need to design for the agency and Other together. To address inequity, we need to engage both process and product. To address colonization and cultural inequity, we need to develop cultural competence. With the underrepresentation of indigenous planners and designers in Hawaiʻi and elsewhere, how do we ensure that our students acquire the competence they need to effectively engage the reality of colonization and social and cultural inequity? This paper suggests some of the ways we can learn from the helping disciplines—social work and public health—as we attempt to educate a new generation of ethical designers. If our goal is an architecture and environmental design curriculum that prepares students to practically address the injustice and failures of our systems, indigenous pedagogies offer a way to broaden the social vocabularies that drive what we teach.

Notes

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Cathi Ho Schar

Cathi Ho Schar is an assistant professor at the School of Architecture, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, and is the inaugural director of the University of Hawaiʻi Community Design Center (UHCDC), where she focuses on the public sector through public interest teaching and practice. She holds degrees from Stanford University and the University of California, Berkeley.

Nicole Biewenga

Nicole Biewenga is a research associate at UHCDC; she earned her BA in architecture from the University of California, Berkeley, College of Environmental Design.

Mark Lombawa

Mark Lombawa is a research associate at UHCDC. He earned his DArch from the School of Architecture, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa.

Notes

1. HCR 85 Task Force, Creating Better Outcomes, Safer Communities: Final Report of the House Concurrent Resolution 85 Task Force on Prison Reform to the Hawaiʻi Legislature 2019 Regular Session (Honolulu: State of Hawaiʻi, 2018), https://www.courts.state.hi.us/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/HCR-85_task_force_final_report.pdf.

2. HCR 85 Task Force, Creating Better Outcomes.

3. A cultural landscape is a place in which a relationship, past or present, exists between a spatial area, resources, and an associated group of indigenous people whose cultural practices, beliefs, or identity connects them to that place. See BOEM, A Guidance Document for Characterizing Native Hawaiian Cultural Landscapes (Honolulu: U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, Pacific OCS Region, 2017), https://www.boem.gov/sites/default/files/environmental-stewardship/Environmental-Studies/Pacific-Region/Studies/2017-023.pdf.

4. Office of Hawaiian Affairs, The Native Hawaiian Justice Task Force Report (Honolulu: Office of Hawaiian Affairs, 2012). https://www.oha.org/wp-content/uploads/2012NHJTF_REPORT_FINAL_0.pdf.

5. Linda Tuhiwai Smith, Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples (Dunedin, NZ: Otago University Press, 2012), 115.

6. Dominique Moran and Yvonne Jewkes, “Linking the Carceral and the Punitive State: A Review of Research on Prison Architecture, Design, Technology, and the Lived Experience of Carceral Space,” Annales de Geographie 702–3, no. 2 (2015): 179, https://doi.org/10.3917/ag.702.0163.

7. Johanna Rincon, “Overrepresentation of Indigenous Peoples in Incarceration Is a Global Concern,” Cultural Survival, August 1, 2013, https://www.culturalsurvival.org/news/. https://www.culturalsurvival.org/news/overrepresentation-indigenous-peoples-incarceration-global-concern.

8. Leah Sakala, “Breaking Down Mass Incarceration in the 2010 Census,” Prison Policy Initiative, May 28, 2014, https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/rates.html.

9. The Office of Hawaiian Affairs study cites several causes of overrepresentation in the criminal justice system beginning with colonialism and racism. See Office of Hawaiian Affairs, Native Hawaiian Justice, 17–18n4.

10. See Richard Wener, The Environmental Psychology of Prisons and Jails: Creating Humane Spaces in Secure Settings (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2012); Paul M. Sheldon and Eugene Atherton, Greening Corrections Technology Guidebook (Rockville, MD: National Law Enforcement and Corrections Technology Center, 2011); and Sander Linden, “Green Prison Programmes, Recidivism and Mental Health: A Primer,” Criminal Behavior and Mental Health 25, no. 5 (December 2015): 338–42.

11. Haunani-Kay Trask, “The Struggle For Hawaiian Sovereignty—Introduction,” Cultural Survival, March 1, 2000, https://www.culturalsurvival.org/publications/cultural-survival-quarterly/struggle-hawaiian-sovereignty-introduction.

12. “West Kimberly Regional Prison Philosophies,” Government of Western Australia, Department of Corrective Services, last modified December 2012, https://www.correctiveservices.wa.gov.au/ files/prisons/prison-locations/wkrp-statement-principles.pdf.

13. Office of the Inspector of Custodial Services, Government of Western Australia, 2017 Inspection of West Kimberly Regional Prison 113 (Perth, WA: Office of the Inspector of Custodial Services, 2017), https://www.oics.wa.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Report-113-West-Kimberley-Regional-Prison.pdf.

14. Paraphrased from Donna Hurdle, “Native Hawaiian Traditional Healing: Culturally Based Interventions for Social Work,” Social Work 47, no. 2 (April 2002): 183–92. Hurdle cited Doman Lum’s social work framework, which includes awareness, knowledge, skill, and inductive learning. See Doman Lum, “Toward a Framework for Social Work Practice with Minorities,” Social Work 27, no. 3 (May 1982): 244–49, https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/27.3.244.

15. Since its publication in 1977, educators continue to expand on methodologies developed in Christopher Alexander et al., A Pattern Language: Towns, Buildings, Construction (New York: Oxford University Press, 1977); see also Christopher Alexander, The Timeless Way of Building (New York: Oxford University Press, 1979); and Stephen Grabow, Christopher Alexander: The Search for a New Paradigm in Architecture (Stocksfield, UK: Oriel Press, 1983). For a contemporary adaptation of the pattern language approach, see University of Arkansas Community Design Center, Housing for Aging Socially: Developing Third Place Ecologies (Fayetteville, AR; Novato, CA: University of Arkansas; ORO, 2017).

16. Students studied Eastern State Penitentiary, La Sante hub and spoke models, the Nara Juvenile Prison modified hub and spoke model, the Maison d’Arret d’Epinal “Street” model, and Blackburn’s Suffolk County Jail cruciform model. Typological precedents include Halden Fengsel Prison and Storstrom Prison, often described as the most humane prison designs in the world, and the Bastoy Island Eco Prison. Additionally, students researched model programs, including Freedom Tails at Stafford Creek Corrections Center; Project Paint at the Richard Donovan Correctional Facility; WeBuilt at Crowley County Correctional Facility; the South Fork Forest Camp, managed by the Oregon Department of Corrections in support of the Tillamook Burn Rehabilitation Program; the Cook County Sheriff’s Garden Program at Cook County Jail; and the Sustainability in Prisons Program in Washington State.

17. The author would like to recognize the UHCDC team on this project: Nicole Biewenga, Mark Lombawa, Jill Misawa, Ivy Tejada, Kristyn Yamamotoya, Shane Matsunaga, Gladys Razos, Hiu Ki Au, Kaylen Daquioag, Xingpun Pang, Hana Fulghum, and Kelsy Jorgenson. We also recognize DPS representatives Wayne Takara, Terry Visperas, and Hal Alejandro.

18. See U.S. Department of Justice, National Institute of Corrections, Jail Design Guide (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, National Institute of Correction, 2011); and American Institute of Architects, AIA Sustainable Justice: Green Guide to Justice (2010). https://network.aia.org/HigherLogic/System/DownloadDocumentFile.ashx?DocumentFileKey=60dcfe06-9b27-418e-9a32-72747ccd0181&forceDialog=0.

19. The 2018 Decolonizing Cities Symposium was a two-day event co-organized by UHCDC in collaboration with the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa Department of Urban and Regional Planning; the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa School of Hawaiian Knowledge; and Interisland Terminal, a nonprofit arts and culture organization.

20. See Auckland Council, “Māori Design,” Auckland Design Manual, April 30, 2020, http://www.aucklanddesignmanual.co.nz/design-subjects/maori-design.

21. Barney G. Glaser and A. L. Strauss, Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research (Chicago: Aldine, 1967), 18.

22. See E. Victoria Shook, Hoʻoponopono: Contemporary Uses of a Hawaiian Problem-Solving Process (Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaiʻi Press, 1985).

23. The Hawaiian word pilina—meaning “association,” “relationship,” “union,” or “joining”—emerged as a repeated theme in studio interviews. See Mary Kawena Pukui and Samuel H. Elbert, New Pocket Hawaiian Dictionary (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1992), s.v. “pilina.” Here, we assess “wellbeing” by the quality of an individual’s relationships with his or her family, community, environment, and the spiritual realm. See E. S. Craighill Handy and Mary Kawena Pukui, The Polynesian Family System in Kaʻu Hawaiʻi (Wellington, NZ: Polynesian Society, 1958), 259.

24. Alexandra Lange, “Let Christopher Alexander Design Your Life,” Curbed, July 11, 2019, https://www.curbed.com/2019/7/11/20686495/pattern-language-christopher-alexander; Alexander et al., Pattern Language, 1171; and R. Kaplan, S. Kaplan, and R. L. Ryan, With People in Mind: Design and Management of Everyday Nature (Bainbridge Island, WA: Island Press, 1998), 1–6, especially their integration of environmental psychology into a framework for considering the human dimension of natural areas, such as parks, open spaces, and vacant lots (67–107). To some degree, these texts preceded and influenced the various design guidelines for social equity that now shape the field. See, e.g., Active Design Guidelines: Promoting Physical Activity and Health in Design (New York: City of New York, 2010); Building Healthy Places Toolkit: Strategies for Enhancing Health in the Built Environment (Washington, DC: Urban Land Institute, 2015); and Assembly: Civic Design Guidelines (New York: Center for Active Design, 2018).

25. Davianna McGregor et al., “An Ecological Model of Native Hawaiian Well-Being,” Pacific Health Dialog 10, no. 2 (2003): 106–28.

26. Faye Cosgrove and Maggie O’Neill, “The Impact of Social Enterprise on Reducing Re-Offending” (working paper, School of Applied Social Sciences, Durham University, May 2011), http://serif-foundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/The-Impact-of-Social-Enterprise-on-Reducing-Re-offending.pdf.

27. The team used two primary biophilic design resources to identify empirical support for the ʻāina strategies: William Browning, Catherine Ryan, and Joseph Clancy, 14 Patterns of Biophilic Design: Improving Health and Well-Being in the Built Environment (New York: Terrapin Bright Green, 2014), https://www.terrapinbrightgreen.com/reports/14-patterns/; and Alex Wilson, “Biophilia in Practice: Buildings that Connect People with Nature,” Building Green 15, no. 7 (2006), https://www.buildinggreen.com/feature/biophilia-practice-buildings-connect-people-nature.

28. On basic human rights, see UN General Assembly, Resolution 61/295, United Nations Declaration on the Right of Indigenous Peoples, A/RES/61/295 (Sept. 13, 2007), https://www.un.org/development/desa/indigenouspeoples/declaration-on-the-rights-of-indigenous-peoples.html. Paraphrasing from the UN website, we note that this declaration serves as the most comprehensive international instrument on the rights of indigenous peoples by establishing minimum standards for the survival, dignity, and wellbeing of the indigenous peoples of the world. It also defines human rights standards and fundamental freedoms as they apply to the specific situation of indigenous peoples.

29. Bud Pomaikaʻi Cook, Kelley Withy, and Lucia Tarallo-Jensen, “Cultural Trauma, Hawaiʻian Spirituality, and Contemporary Health Status,” California Journal of Health Promotion 1 (2003): 10–24.

30. Bud Pomaikaʻi Cook, Kelly Withy, Lucia Tarallo-Jensen. Paraphrasing Cook, we note that HTR is a reaction to the violation of selfhood that results from being classified as “different” from the incoming colonial power. HTR effects the physical, emotional, mental, and social wellbeing of individuals, families, and the entire culture, and it is passed down through generations. Symptoms include depression, self-destructive behavior, substance abuse, and fixation on trauma, anxiety, guilt, and grief. Cultural wounding is when colonialization creates psychological, spiritual, and cultural injury through which a cycle of historical trauma is made fresh in the minds of the living. This can be a result of a violation to a person’s self and cultural artifacts, which may include physical characteristics, family genealogy, geographic place of origin, traditional religious practices, traditional cultural practices, gender roles, and distortion of the historical record.

31. Cook, Withy, Tarallo-Jensen.