Abstract

This essay uses the lens of teaching an undergraduate survey lecture course to explore ways to root pedagogy in the premise that architecture is not neutral. I argue that teaching difference and inequality as key categories through which architectural history and urbanism are approached prepares future professionals to act ethically and deepens understandings of architecture. The essay examines a set of methods for doing so within the lecture hall, illustrating the journey upon which I take students when cities and architecture are explored as landscapes of othering.

Keywords:

Difference—racial, ethnic, gendered, class-based difference—is embedded in architecture.

I propose that this statement increasingly serves as a point of departure in architectural curricula. Many of us have begun—or have long been—teaching that architecture is not a set of silent objects. In doing so, we illustrate that buildings and infrastructure are actively and subjectively produced and are structured by negotiations and experiences grounded in racialized, gendered, ethnic, and class-based inequalities. Shifting away from the perspective that the field is neutral or mute elevates foundational architectural knowledge. By integrating gender, race, and class-aware perspectives into teaching the core courses, architecture becomes a richer and even more meaningful discipline.

Take, for example, Katherine McKittrick’s analysis of the slave ship. As she stated, the slave ship is more than a mere mute container for human complexities and social relations. Rather, it is the “site of violent subjugation that reveals, rather than conceals, the racial-sexual location of black cultures in the face of unfreedoms.”1 To study the slave ship as a built product with social meaning is to productively deepen how we understand the ship’s design and use by acknowledging those histories that continue to exist in contemporary racialized culture. The slave ship, like any designed product, was conceived and constructed with particular uses in mind; in its case, these were never divorced from the violent subjugations at the heart of the project of enslaving and trading a racialized set of human beings. Likewise, studying the lived realities of slave ships expands the historical significance we grant them as design items by illustrating their role in producing long-lasting relationships of dominance and inequality.

A parallel argument can be made regarding approaching works of architecture as meaning laden. An example is Otto Wagner’s Postal Savings Bank in Vienna. The building exemplifies early modernism’s expression of the means of construction, with its riveted-steel adorned exterior, aluminum trims and furnishings, and innovative use of glass.2 Yet when the bank is seen as a work of architecture in its historical totality, it is far from apolitical. It was the product of a populist, anti-Semitic movement that sought to draw business away from Jewish bankers.3 The architecture’s non-figural decoration was influenced by fellow Viennese architect Adolph Loos’s invective against ornamentation, which was rooted in the racism of nineteenth century criminal anthropology.4 Like so many works of modern architecture that are regularly lauded for formal attributes, its political history is complicated and troubling.5 Both this analysis and McKittrick’s of the slave ship attend to formal attributes such as materiality and structure, through discourses that denaturalize their production. This reflects my belief that architectural form is historically produced and historically productive, and it can be taught as such. Consequently, when we ground our understanding of architecture in the contexts in which it is produced, its full weight and significance become apparent.

In my teaching, I am concerned with communicating to students the myriad ways in which the contexts architecture operates are marked by categories of difference. As Homi Bhabha stated, difference is a process of signification through which cultures come to be understood as “never unitary.”6 Difference is vital to reveal because it shatters the myths of universality that have grounded how knowledge and power have been produced through modernity (particularly colonial modernity) and that pervade architectural thought.7 For me, this is especially relevant to do in the required, upper-division, urbanism lecture course I teach. The course is intended to introduce students to the complex range of issues that arise as we try to understand cities and to connect the architectural and urban scales. I would consider it misleading, in teaching such a course, not to acknowledge and address how urban processes have been historically—and continue today to be—racialized, gendered, and class-based. To accomplish my curricular role and my project of exposing students to an awareness of difference, I take students on a journey across urban history that examines if, and how, forms of othering take place.

It is not incidental that I choose to conduct this journey in a required survey course.8 The lecture hall offers a unique opportunity—and set of challenges—for claiming that categories of difference operate as architectural sites. Architecture programs globally are questioning the potential tautology of traditional survey courses and particularly the exclusionary privileging of the West in architectural history surveys.9 These shifts question what—and whose—histories we communicate to our students are foundational to the discipline. Yet while lecture courses are potentially problematic, they also offer the opportunity to introduce perspectives such as race-, class-, and gender-conscious material to the entirety of a program’s student body. There is the risk of inviting a backlash, particularly at institutions where students or faculty resist notions of structurally produced inequalities or where recognition of difference is seen as outside the boundaries of core subjects such as architectural history. Yet it is arguably most productive to offer such insights to the “masses” of architecture students who populate the lecture hall. I do this in an urbanism course because that is my contribution to my program’s history/theory curriculum. More importantly, I do so here because the complexity of issues that arise at the site and scale of cities provides fertile ground for making students aware that no element of the built environment is produced without politics and that no experience is universal.

What follows is an illustration of some of the ways in which I do so, seen through three itineraries I take with my students.10 These itineraries are active journeys of learning that dwell upon and problematize some of the foundational ways in which questions of subjectivity and otherness are typically written out of consideration in architectural curriculum. They draw attention to the lenses we can use to investigate canonical sites to see difference. They point to rethinking which sites are valid ones to expose to students.11 This is a questioning of architecture’s disciplinary boundaries and a (re)consideration of what the survey wants to teach: What is the purpose of the survey in architectural education?12

Itinerary I: Experience

As my students and I move across the globe and through urban history, one of the itineraries we take is that of experience. As we examine urban designs and instances of iconic urban architecture, one of the agents we pay attention to is the designs’ inhabitants: we study figures such as neighborhood residents and city inhabitants to understand the human dimension of architecture that lives on after the work of design and construction are completed.13 The introduction of experience broadens students’ understanding of the work that architecture does, studying the people, places, and practices with which architecture engages. To study spatial experiences is to deprivilege the city as seen removed, from above, as discussed by Michel de Certeau in his well-known comparison of the city understood through walking rather than from the bird’s-eye view.14 And as Henri Lefebvre has argued, the ways in which space is lived are integral attributes rather than exterior qualities of space.15 Studying experience disturbs the notion that the only things we can say about architecture relate to its form.16 Going beyond formal analysis acknowledges difference, in the users and producers of architecture. Introducing spatial experiences is a means to include architecture’s hidden figures: those voices and actors potentially marginalized in/by the production of architecture.

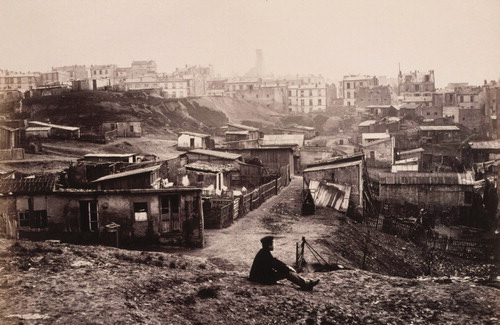

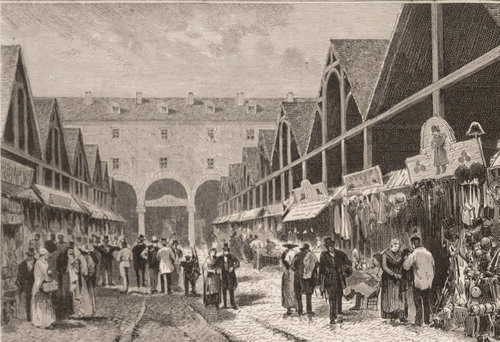

A method I have found for accessing experience is to draw upon representations from the visual, literary, and performing arts.17 This enables students to recognize the differing ways people experience cities and works of architecture, particularly through the categories of gender, race, and class. A lecture that showcases this is on the Haussmannization of nineteenth-century Paris, where I discuss both the spatial changes brought to the city and the ways in which residents experienced these, such as in the large-scale displacements that occurred as huge portions of the medieval city were demolished to make way for its new boulevards. To capture how lower economic classes were marginalized through the city’s remaking, I show Charles Marville’s documentary photographs of the demolitions and squatter settlements that accompanied Baron Haussmann’s new constructions (). I read Charles Baudelaire’s poem “Eyes of the Poor”—and play The Cure’s version of it—which narrates a couple’s stimulating day on Paris’s new boulevards and café-concerts that poignantly ends with an uncomfortable encounter with a family financially unable to enjoy the city’s new riches.18 I have the entire class participate in analyses of paintings by Vincent Van Gogh and Edouard Manet, such as with a close visual reading of Manet’s Un Bar Aux Folies-Bergère, in which we discuss how the painting’s elusive representation of the figure of the female worker embodies anxieties about gender that were mapped onto the changing city ().19 I summarize portions of Emile Zola’s novel The Ladies Paradise, which communicates the entangled ways in which gendered and class-based experiences were reshaped as Paris’s quartiers were rapidly transformed or demolished to make way for department stores ().20 In these discussions and others in which I utilize artists’ work to illustrate experience, introducing modes of representation less common in the classroom—a music video, painting, or poem—admittedly serves as spectacle. In these cases, however, I utilize the attention the spectacle gathers to draw attention to human experience, which otherwise is challenging to access from traditional architectural historical records. I choose a variety of media from a variety of time periods to illustrate to students the pervasive relevance of these spatial acts and experiences to multiples generations and types of artists.

Figure 1. Lecture Slide 7.38: Charles Marville, Top of the rue Champlain, View to the Right (1877–1878). (Les Musées de la Ville de Paris.)

Figure 2. Lecture Slide 7.53: Edouard Manet, Un Bar Aux Folies-Bergère (1882). (The Courtauld Gallery, University College London.)

Figure 3. Lecture Slide 7.49: Theodor Josef Hubert Hoffbauer, Marché du Temple en 1840 (1875–1882). (Brown University Library.)

Such experience-based itineraries are not limited to the Paris lecture. For example, when discussing the architectural and urban history of Regency London, I bring the new shopping spaces, such as Regent Street and arcades, into conversations with the ways in which women were perceived in such spaces: I juxtapose images of the city alongside cartoons that questioned women’s morality when they were seen in public space.21 Through such representations, students come to understand that these new architectural spaces held—and helped produce—different meanings for different classes and genders. The students are exposed to how the new architectural shopping typologies served as spaces of leisure and consumption only for those who could afford them and who were considered, by virtue of their gender and class, as legitimate users. By extension, we discuss how architecture and urban design can function as technologies of urban division, as Regent Street bifurcated London into wealthy and impoverished halves. These discussions are accompanied by analysis of the material economies used to build London’s new streets and residential terraces, and of the relationship between the architectures and economic activities of London with new British manufacturing towns, such as Manchester.22

Itinerary II: Intersection

To privilege experience is—or can be—to draw attention to the ways in which categories of difference and marginalization are interconnected or intersectional. Intersectionality understands that an individual’s differing racial, gendered, and class-based subjectivities combine to work together.23 To focus on intersections in architecture and urbanism means to recognize that racial difference often maps onto class and gender difference, always in unique and complicated ways, and that such differences operate through architecture.24 To utilize literary, visual, and performance arts can also be a means of illustrating less commonly seen connections between issues and subjectivities. One art piece I use is the 2016 video for Beyoncé’s song “Formation,” which rapidly layers images of disparate spaces and themes, including Hurricane Katrina’s devastating flooding and critiques about police violence ().25 I interweave clips from the video—focusing on scenes of devastated neighborhoods, such as the Lower Ninth Ward in New Orleans, and cuts of a young black boy dancing in front of a line of police officers in riot gear—into a lecture about climate change. Beyoncé helps me do my pedagogical work of introducing the idea that the wreckage reaped by climate change—which I show moments before in images of New Orleans, Houston, and Puerto Rico after Hurricanes Katrina, Harvey, and Maria—is unevenly experienced along racial lines.26 This argument develops further as we discuss the demolition of public housing in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina and trace how the racial implications of such a policy work through the focus of real estate speculation ().27

Figure 4. Lecture Slide 17.23: Beyonce Knowles, still from video “Formation,” directed by Melina Matsoukas (2016, New York: ©Parkwood Entertainment).

Figure 5. Lecture Slide 17.30: Infrogmation, New Orleans: Demolition Work Ongoing of the Lafitte Housing Projects (2008). (Creative Commons BY-SA 3.0.)

Such discussions also help illuminate the racial erasures that take place in work by canonical architects. For example, when discussing Chicago, I highlight how Mies van der Rohe’s Cartesian perfection, the IIT Campus, relied upon a reading of its site as a tabula rasa, when in fact it had been a densely populated, though lower-income section of an African American neighborhood. I give an overview of the site’s history and show images of the IIT campus seen in its context—which is a less-commonly seen perspective of the Miesian masterpiece (). Or when discussing the phenomenon of the mid-century American suburb, I draw upon Dianne Harris’s analysis that racial difference was deeply imbricated in the ideological making of the suburban house, through both legislation—such as redlining—and representations of idealized suburban domesticity.28 These analytical lenses demonstrate to students the means through which architectural practices, which are commonly seen singularly through their formal implications, are intersectionally racialized productions and sites of economic forces.

Itinerary III: Action

In the preceding itineraries, I expose students to ways in which the making or experience of (often iconic) architecture contributes to the production of othered peoples and places. The third itinerary instead shows students ways in which those who are frequently othered contribute to the making of cities. Here I shift focus from the iconic to the informal and the everyday to expand the terrain of celebrated architecture to include those spaces that operate as sites of social action and architectural imagination.29 Within this itinerary, I work to destabilize traditional notions of the canonical by disturbing boundaries that attempt to distinguish rarified architecture from other types of building.30 I argue that we should teach students not only about those works of architecture and urban design by supposedly noteworthy architects but also those produced as part of significant civic actions that seek to address critical social issues.

This itinerary travels to sites in the Global South, where we see spaces of informality such as taxi ranks and self-built housing, and intense juxtapositions of privilege and poverty (). The journey exposes students to the notion that such conditions also exist closer to home, examining informality and everyday architectural productions in the Global North. One way we do so is by visiting Houston. There we visit Project Row Houses, where a group of artists bought up twenty-two dilapidated row houses in the city’s rundown, historically black Third Ward and converted them into an arts community that offers residencies, after-school programs, and housing for single mothers.31 Together, we examine the paintings by John Biggers that grounded the vision of the project in a reclaiming of the neighborhood as a site of African American culture ().32 We also study the anti-gentrification actions Project Row Houses has undertaken so that those intended to be served do not end up being pushed out of their neighborhood as a result of its improvement. By seeing how the group has established funding mechanisms and constructed affordable housing in partnership with the Rice University School of Architecture, the students begin to develop an expansive view of architecture’s potential contributions to the urban realm.

Figure 8. Lecture Slide 22.61: John Biggers, Shotgun, Third Ward #1 (1966). (Anacostia Community Museum, Smithsonian Institution.)

The class stays a little longer in Houston to visit BakerRipley, a community service organization that offers various services, including job training, health clinics, housing advice, and the construction of neighborhood centers ().33 We visit the communities that BakerRipley serves, discussing the ways in which underserved and ethnically diverse exurbs are intrinsically part of the everyday landscape of the contemporary American metropolis. These neighborhoods and interventions tell a different type of architectural history than that of spaces for the powerful and elite. By highlighting stories of architectural projects constructed by grassroots organizations, students are exposed to the architectural imaginaries of women, ethnic and racial minorities, and people who are economically marginalized. Studying such types of architecture and methods of architectural production provides the opportunity to include practices and subjectivities rarely addressed within traditional survey courses.

These itineraries—which include numerous other stops taken during the course—bring into the lecture hall subjectivities rarely seen in conjunction with the teaching of canonical architecture and planning projects. The reactions to this are mixed: some students comment at the end of the semester that they—African American or Muslim or Latinx students—had never before seen themselves represented in an architectural class. During lectures, I see numerous students nodding their heads in recognition of conditions they’ve observed or personally experienced. I also see a few students glaze over, and I occasionally receive negative course evaluations for “bringing my bias” into the classroom.

While constantly working to shape the curriculum in a way that speaks to all students, I knowingly risk negative reactions in the hope that students come away with an enriched understanding of architecture, which includes an awareness that othering exists and is sometimes —even if unwittingly—architecturally produced. My hope is that such an awareness will translate into the ethics students develop as future practitioners. I have developed this pedagogy as a proposition for the work that survey courses can do: they can exceed the aspiration to enable students to understand subject material—history, urbanism, theory, construction—by helping prepare our students to operate as both citizens and professionals in a rapidly changing world. I am proposing that an architectural education predicated on architecture’s non-neutrality can position students to contribute meaningfully to the world’s pressing challenges. It can make them aware of how their chosen profession can engage with ethical and discipline-specific problems, enabling them to realize that the two are often interconnected. In this way, architecture and architects can move toward practices of productive citizenship.

Acknowledgments

I presented a related, though differently focused, set of arguments at the Society of Architectural Historian’s 2020 (Virtual) Conference, in the session titled “Placing Race and Gender: New Findings and Strategies for Architectural History,” chaired by Lauren O’Connell. Many thanks to Susanne Schindler and Kevin Jones for insightful comments on earlier versions of this essay.

Notes

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Sharóne L. Tomer

Sharóne L. Tomer, Ph.D., is an assistant professor of architecture at the School of Architecture + Design at Virginia Tech, where she teaches design studios and urbanism courses. Her research examines architectural relationships between spatial and political-economic change in contexts ranging from late-apartheid Cape Town to suburban Appalachia. She has contributed chapters and articles to Dialectic IV: Architecture at Service (ORO, 2016), Suffragette City: Women, Politics and the Built Environment (Routledge, 2019), and Neoliberalism on the Ground: Architecture & Transformation from the 1960s to the Present (University of Pittsburgh, 2020). She received her doctorate from the University of California, Berkeley.

Notes

1 Katherine McKittrick, Demonic Grounds: Black Women and the Cartographies of Struggle (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006), xii.

2 William J. R. Curtis, Modern Architecture Since 1900, vol. 3 (London: Phaidon Press, 1996); and Kenneth Frampton, Modern Architecture: A Critical History, vol. 3 (New York: Thames and Hudson, 1992).

3 Carl E. Schorske, Fin-de-Siècle Vienna: Politics and Culture (New York: Knopf, 1979).

4 Jimena Canales and Andrew Herscher, “Criminal Skins: Tattoos and Modern Architecture in the Work of Adolf Loos,” Architectural History 48 (2005): 235–56.

5 This argument was made in Irene Cheng, Charles L. Davis, and Mabel O. Wilson, eds., Race and Modern Architecture: A Critical History from the Enlightenment to the Present (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2020).

6 Homi K. Bhabha, “Cultural Diversity and Cultural Differences,” in The Post-Colonial Studies Reader, ed. Bill Ashcroft, Gareth Griffiths, and Helen Tiffin (London: Routledge, 1995), 206–7.

7 Ashcroft, Griffiths, and Tiffin, Post-Colonial Studies Reader, 55; and Edward W. Said, Orientalism, 25th anniversary vol. (New York: Vintage Books, 2003).

8 There is a wealth of scholarship and initiatives that question the canonical approach and Western focus of architectural history surveys. A partial list includes the Journal of Architectural Education 52, no. 4 (1999), whose theme was “Critical Historiography and the End of Theory”; the Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 58, no. 3 (1999), which was a special themed issue titled “Architectural History 1999/2000”; Frank Ching, Mark Jarzombek, and Vikramaditya Prakash, A Global History of Architecture (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2007); the Global Architectural History Teaching Collaborative (January 30, 2020) https://gahtc.org/; and “Theory’s Curriculum,” Architecture Exchange (January 30, 2020), https://architecture.exchange/curriculum/.

9 This can be seen in Yale University’s early 2020 announcement that it will cease offering its iconic survey course in art history, long taught by Vincent Scully. Margaret Hedeman and Matt Kristoffersen, “Art History Department to Scrap Survey Course,” Yale Daily News, January 24, 2020, https://yaledailynews.com/blog/2020/01/24/art-history-department-to-scrap-survey-course/.

10 The metaphor of itinerary is inspired by Jane M. Jacobs, Edge of Empire: Postcolonialism and the City (London: Routledge, 1996).

11 Petra L. Doan, “The Tyranny of Gendered Spaces—Reflections from Beyond the Gender Dichotomy,” Gender, Place & Culture 17, no. 5 (October 2010): 643.\\uc0\\u8221{} {\\i{}Gender, Place & Culture} 17, no. 5 (October 1, 2010

12 Gülsüm Baydar Nalbantoḡlu, “Toward Postcolonial Openings: Rereading Sir Banister Fletcher’s ‘History of Architecture,’” Assemblage, no. 35 (April 1998): 6–17.

13 Kenny Cupers, ed., Use Matters: An Alternative History of Architecture (London: Routledge, 2013).

14 Michel de Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life, trans. Steven Rendall (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984).

15 Henri Lefebvre, The Production of Space, trans. Donald Nicholson-Smith (Oxford: Blackwell, 1991).

16 Lesley Naa Norle Lokko, White Papers, Black Marks: Architecture, Race, Culture (London: Athlone Press, 2000), 16.

17 My use of visual, literary, and performing arts has been inspired by my graduate education at the University of California, Berkeley—both in courses I took and in work by my colleagues. See, e.g., Nezar AlSayyad, Cinematic Urbanism: A History of the Modern from Reel to Real (New York: Routledge, 2006); and Joseph Godlewski, “The Tragicomic Televisual Ghetto: Popular Representations of Race and Space at Chicago’s Cabrini Green,” Berkeley Planning Journal 22, no. 1 (2009): 115–25.

18 Charles Baudelaire, “The Painter of Modern Life” (1863); The Cure, “How Beautiful You Are,” track 6 on Kiss Me, Kiss Me, Kiss Me, Elektra, 1997, compact disc; Charles Baudelaire, “The Eyes of the Poor,” in Paris Spleen: Little Poems in Prose, trans. Keith Waldrop (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2009): 51-52.

19 T. J. Clark, The Painting of Modern Life: Paris in the Art of Manet and His Followers, rev. ed. (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1999).

20 Emile Zola, The Ladies’ Paradise trans. Frank Belmont (London: Tinsley, 1883).

21 Jane Rendell, The Pursuit of Pleasure: Gender, Space & Architecture in Regency London (London: Athlone Press, 2002).

22 Steven Marcus, Engels, Manchester, and the Working Class, vol. 1 (New York: Random House, 1974).

23 bell hooks, Feminist Theory: From Margin to Center (London: Pluto Press, 2000); Cherríe Moraga and Gloria Anzaldúa, eds., This Bridge Called My Back, Fourth Edition: Writings by Radical Women of Color (Albany: SUNY Press, 2015).

24 A poignant example of such analysis is in the chapter “Eastern Trading: Diasporas, Dwelling and Place,” in Jacobs, Edge of Empire, 70–102.

25 Beyoncé, “Beyoncé—Formation,” directed by Melina Matsoukas, posted December 9, 2016, YouTube video, 4:47, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WDZJPJV__bQ.

26 The uneven burden of climate change, particularly in the case of Hurricane Katrina, is discussed widely in popular and scholarly presses, as has been the insightfulness Beyoncé expressed in “Formation.” See, e.g., Syreeta McFadden, “Beyoncé’s Formation Reclaims Black America’s Narrative from the Margins,” Guardian, February 8, 2016, sec. Opinion, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/feb/08/beyonce-formation-black-american-narrative-the-margins.

27 Naomi Klein, The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism, vol. 1 (New York: Metropolitan Books/Henry Holt, 2007).

28 Dianne Harris, Little White Houses (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013).

29 John Chase, Margaret Crawford, and John Kaliski, eds., Everyday Urbanism (New York: Monacelli Press, 1999); Steven Harris and Deborah Berke, eds., Architecture of the Everyday (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1997); and Henri Lefebvre, Critique of Everyday Life, trans. John Moore (London: Verso, 1991).

30 Nalbantoḡlu, “Toward Postcolonial Openings.”

31 Grant H. Kester, The One and the Many: Contemporary Collaborative Art in a Global Context (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011).

32 A Houston developer, in justifying removing low-income residents from an adjacent neighborhood, stated that “the only culture displaced was a culture of needles and syringes.” See Kester, 218.

33 Michael Berryhill, “Houston’s Quiet Revolution,” Places Journal, March 14, 2016, https://doi.org/10.22269/160314.